Network scanning refers to a set of procedures that investigate a live host, the type of host, open ports, and the type of services running on the host. Network scanning is a part of intelligence gathering by virtue of which an attack can create a profile of the target organization.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

- How to check live systems

- Ping sweep

- TCP scanner

- How to create an efficient IP scanner

- Services running on the target machine

- The Concept of a port scanner

- How to create an efficient port scanner

You should have basic knowledge of the TCP/IP layer communication. Before proceeding further, the concept of the Protocol Data Unit (PDU) should be clear.

PDU is a unit of data specified in the protocol. It is the generic term for data at each layer.

- For the application layer, PDU indicates data

- For the transport layer, PDU indicates a segment

- For the Internet or the network layer, PDU indicates a packet

- For the data link layer or network access layer, PDU indicates a frame

- For the physical layer, that is, physical transmission, PDU indicates bits

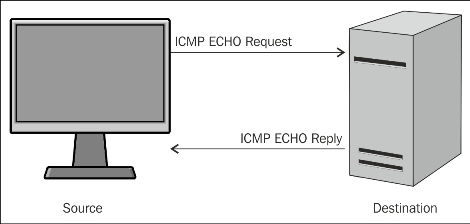

Ping scan involves sending an ICMP ECHO Request to a host. If a host is live, it will return an ICMP ECHO Reply, as shown in the following image:

ICMP request and reply

The operating system's ping command provides the facility to check whether the host is live or not. Consider a situation where you have to test a full list of IP addresses. In this situation, if you test the IP one by one, it will take a lot of time and effort. In order to handle this situation, we use ping sweep.

Ping sweep is used to identify the live host from a range of IP addresses by sending the ICMP ECHO request and the ICMP ECHO reply. From a subnet and network address, an attacker or pentester can calculate the network range. In this section, I am going to demonstrate how to take advantage of the ping facility of an operating system.

First, I shall write a simple and small piece of code, as follows:

import os

response = os.popen('ping -n 1 10.0.0.1')

for line in response.readlines():

print line,In the preceding code, import os imports the OS module so that we can run the OS command. The next line os.popen('ping -n 1 10.0.0.1') that takes a DOS command is passed in as a string and returns a file-like object connected to the command's standard input or output streams. The ping –n 1 10.0.0.1 command is a Windows OS command that sends one ICMP ECHO request packet. By reading the os.psopen() function, you can intercept the command's output. The output is stored in the response variable. In the next line, the readlines() function is used to read the output of a file-like object.

The output of the program is as follows:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>ips.py Pinging 10.0.0.1 with 32 bytes of data: Reply from 10.0.0.1: bytes=32 time=3ms TTL=64 Ping statistics for 10.0.0.1: Packets: Sent = 1, Received = 1, Lost = 0 (0% loss), Approximate round trip times in milli-seconds: Minimum = 3ms, Maximum = 3ms, Average = 3ms

The output shows the reply, byte, time, and TTL values, which indicate that the host is live. Consider another output of the program for IP 10.0.0.2.

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>ips.py Pinging 10.0.0.2 with 32 bytes of data: Reply from 10.0.0.16: Destination host unreachable. Ping statistics for 10.0.0.2: Packets: Sent = 1, Received = 1, Lost = 0 (0% loss),

The preceding output shows that the host is not live.

The preceding code is very important for proper functioning, and is similar to the engine of a car. In order to make it fully functional, we need to modify the code so that it is platform independent and produce easily readable output.

I want my code to work for a range of IPs:

import os

net = raw_input("Enter the Network Address ")

net1= net.split('.')

print net1

a = '.'

net2 = net1[0]+a+net1[1]+a+net1[2]+a

print net2

st1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Starting Number "))

en1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Last Number "))The preceding code asks for the network address of the subnet, but you can give any IP address of the subnet. The next line net1= net.split('.') splits the IP address in four parts. The net2 = net1[0]+a+net1[1]+a+net1[2]+a statement forms the network address. The last two lines ask for a range of IP addresses.

To make it platform independent, use the following code:

import os import platform oper = platform.system() if (oper=="Windows"): ping1 = "ping -n 1 " elif (oper== "Linux"): ping1 = "ping -c 1 " else : ping1 = "ping -c 1 "

The preceding code determines whether the code is running on Windows OS or the Linux platform. The oper = platform.system() statement informs this to the running operating system as the ping command is different in Windows and Linux. Windows OS uses ping –n 1 to send one packet of the ICMP ECHO request, whereas Linux uses ping –c 1.

Now, let's see the following full code:

import os

import platform

from datetime import datetime

net = raw_input("Enter the Network Address ")

net1= net.split('.')

a = '.'

net2 = net1[0]+a+net1[1]+a+net1[2]+a

st1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Starting Number "))

en1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Last Number "))

en1=en1+1

oper = platform.system()

if (oper=="Windows"):

ping1 = "ping -n 1 "

elif (oper== "Linux"):

ping1 = "ping -c 1 "

else :

ping1 = "ping -c 1 "

t1= datetime.now()

print "Scanning in Progress"

for ip in xrange(st1,en1):

addr = net2+str(ip)

comm = ping1+addr

response = os.popen(comm)

for line in response.readlines():

if(line.count("TTL")):

break

if (line.count("TTL")):

print addr, "--> Live"

t2= datetime.now()

total =t2-t1

print "scanning complete in " , totalHere, a couple of new things are in the preceding code. The for ip in xrange(st1,en1): statement supplies the numeric values, that is, the last octet value of the IP address. Within the for loop, the addr = net2+str(ip) statement makes it one complete IP address, and the comm = ping1+addr statement makes it a full OS command which passes to os.popen(comm). The if(line.count("TTL")): statement checks for the occurrence of TTL in the line. If any TTL value is found in the line, then it breaks the further processing of the line by using the break statement. The next two lines of code print the IP address as live where TTL is found. I used datetime.now() to calculate the total time taken to scan.

The output of the ping_sweep.py program is as follows:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>python ping_sweep.py Enter the Network Address 10.0.0.1 Enter the Starting Number 1 Enter the Last Number 60 Scanning in Progress 10.0.0.1 --> Live 10.0.0.2 --> Live 10.0.0.5 --> Live 10.0.0.6 --> Live 10.0.0.7 --> Live 10.0.0.8 --> Live 10.0.0.9 --> Live 10.0.0.10 --> Live 10.0.0.11 --> Live scanning complete in 0:02:35.230000

To scan 60 IP addresses, the program has taken 2 minutes 35 seconds.

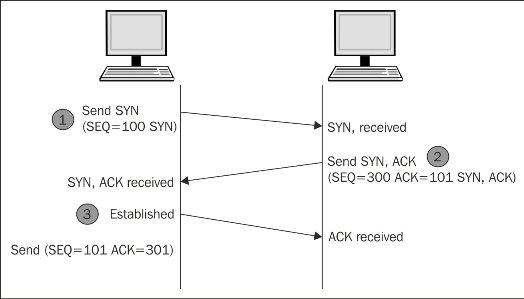

Ping sweep works on the ICMP ECHO request and the ICMP ECHO reply. Many users turn off their ICMP ECHO reply feature or use a firewall to block ICMP packets. In this situation, your ping sweep scanner might not work. In this case, you need a TCP scan. I hope you are familiar with the three-way handshake, as shown in the following image:

To establish the connection, the hosts perform a three-way handshake. The three steps in establishing a TCP connection are as follows:

- The client sends a segment with the SYN flag; this means the client requests the server to start a session.

- In the form of a reply, the server sends the segment that contains the ACK and SYN flags.

- The client responds with an ACK flag.

Now, let's see the following code of a TCP scan:

import socket

from datetime import datetime

net= raw_input("Enter the IP address ")

net1= net.split('.')

a = '.'

net2 = net1[0]+a+net1[1]+a+net1[2]+a

st1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Starting Number "))

en1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Last Number "))

en1=en1+1

t1= datetime.now()

def scan(addr):

sock= socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM)

socket.setdefaulttimeout(1)

result = sock.connect_ex((addr,135))

if result==0:

return 1

else :

return 0

def run1():

for ip in xrange(st1,en1):

addr = net2+str(ip)

if (scan(addr)):

print addr , "is live"

run1()

t2= datetime.now()

total =t2-t1

print "scanning complete in " , totalThe upper part of the preceding code is the same as the previous code. Here, we use two functions. Firstly, the scan(addr) function uses the socket as discussed in Chapter 1, Python with Penetration Testing and Networking. The result = sock.connect_ex((addr,135)) statement returns an error indicator. The error indicator is 0 if the operation succeeds, otherwise, it is the value of the errno variable. Here, we used port 135; this scanner works for the Windows system. There are some ports such as 137, 138, 139 (NetBIOS name service), and 445 (Microsoft-DSActive Directory), which are usually open. So, for better results, you have to change the port and scan repeatedly.

The output of the iptcpscan.py program is as follows:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>python iptcpscan.py Enter the IP address 10.0.0.1 Enter the Starting Number 1 Enter the Last Number 60 10.0.0.8 is live 10.0.0.11 is live 10.0.0.12 is live 10.0.0.15 is live scanning complete in 0:00:57.415000 G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>

Let's change the port number, use 137, and see the following output:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>python iptcpscan.py Enter the IP address 10.0.0.1 Enter the Starting Number 1 Enter the Last Number 60 scanning complete in 0:01:00.027000 G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>

So there will be no outcome from that port number. Change the port number, use 445, and the output will be as follows:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>python iptcpscan.py Enter the IP address 10.0.0.1 Enter the Starting Number 1 Enter the Last Number 60 10.0.0.5 is live 10.0.0.13 is live scanning complete in 0:00:58.369000 G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>

The preceding three outputs show that 10.0.0.5, 10.0.0.8, 10.0.0.11, 10.0.0.12, 10.0.0.13, and 10.0.0.15 are live. These IP addresses are running on the Windows OS. So this is an exercise for you to check the common open ports for Linux and make IP a complete IP TCP scanner.

So far, you have seen the ping sweep scanner and the IP TCP scanner. Imagine that you buy a car that has all the facilities, but the speed is very slow, then you feel that it is a waste of time. The same thing happens when the execution of our program is very slow. To scan 60 hosts, the ping_sweep.py program took 2 minutes 35 seconds for the same range of IP addresses for which the TCP scanner took nearly one minute. They take a lot of time to produce the results. But don't worry. Python offers you multithreading, which will make your program faster.

I have written a full program of ping sweep with multithreading, and will explain this to you section-wise:

import os

import collections

import platform

import socket, subprocess,sys

import threading

from datetime import datetime

''' section 1 '''

net = raw_input("Enter the Network Address ")

net1= net.split('.')

a = '.'

net2 = net1[0]+a+net1[1]+a+net1[2]+a

st1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Starting Number "))

en1 = int(raw_input("Enter the Last Number "))

en1 =en1+1

dic = collections.OrderedDict()

oper = platform.system()

if (oper=="Windows"):

ping1 = "ping -n 1 "

elif (oper== "Linux"):

ping1 = "ping -c 1 "

else :

ping1 = "ping -c 1 "

t1= datetime.now()

'''section 2'''

class myThread (threading.Thread):

def __init__(self,st,en):

threading.Thread.__init__(self)

self.st = st

self.en = en

def run(self):

run1(self.st,self.en)

'''section 3'''

def run1(st1,en1):

#print "Scanning in Progess"

for ip in xrange(st1,en1):

#print ".",

addr = net2+str(ip)

comm = ping1+addr

response = os.popen(comm)

for line in response.readlines():

if(line.count("TTL")):

break

if (line.count("TTL")):

#print addr, "--> Live"

dic[ip]= addr

''' Section 4 '''

total_ip =en1-st1

tn =20 # number of ip handled by one thread

total_thread = total_ip/tn

total_thread=total_thread+1

threads= []

try:

for i in xrange(total_thread):

en = st1+tn

if(en >en1):

en =en1

thread = myThread(st1,en)

thread.start()

threads.append(thread)

st1 =en

except:

print "Error: unable to start thread"

print "\t

Number of Threads active:", threading.activeCount()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print "Exiting Main Thread"

dict = collections.OrderedDict(sorted(dic.items()))

for key in dict:

print dict[key],"-->" "Live"

t2= datetime.now()

total =t2-t1

print "scanning complete in " , totalThe section 1 section is the same as that for the previous program. The one thing that is additional here is that I have taken an ordered dictionary because it remembers the order in which its contents are added. So if you want to know which thread gives the output first, then the ordered dictionary fits here. The section 2 section contains the threading class, and the class myThread (threading.Thread): statement initializes the threading class. The self.st = st and self.en = en statements take the start and end range of the IP address. The

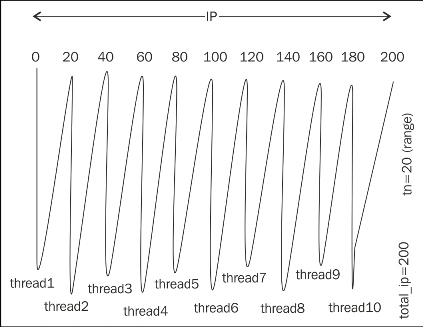

section 3 section contains the definition of the run1 function, which is the engine of the car, and is called by every thread with a different IP address range. The dic[ip]= addr statement stores the host ID as a key and the IP address as a value in the ordered dictionary. The section 4 statement is totally new in this code; the total_ip variable is the total number of IPs to be scanned. The significance of the tn =20 variable is that it states that 20 IPs will be scanned by one thread. The total_thread variable contains the total number of threads that need to scan total_ip, which denotes the number of IPs. The threads= [] statement creates an empty list, which will store the threads. The for loop for i in xrange(total_thread): produces threads.

en = st1+tn

if(en >en1):

en =en1

thread = myThread(st1,en)

thread.start()

st1 =enThe preceding code produces the range of 20-20 IPs, such as st1-20, 20-40 ……-en1. The thread = myThread(st1,en) statement is the thread object of the threading class.

for t in threads: t.join()

The preceding code terminates all the threads. The next line dict = collections.OrderedDict(sorted(dic.items())) creates a new sorted dictionary dict, which contains IP addresses in order. The next lines print the live IP in order. The threading.activeCount() statement shows how many threads are produced. One picture saves 1000 words. The following image does the same thing:

Creating and handling of threads

The output of the ping_sweep_th_.py program is as follows:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>python ping_sweep_th.py Enter the Network Address 10.0.0.1 Enter the Starting Number 1 Enter the Last Number 60 Number of Threads active: 4 Exiting Main Thread 10.0.0.1 -->Live 10.0.0.2 -->Live 10.0.0.5 -->Live 10.0.0.6 -->Live 10.0.0.10 -->Live 10.0.0.13 -->Live scanning complete in 0:01:11.817000

Scanning has been completed in 1 minute 11 seconds. As an exercise, change the value of the tn variable, set it from 2 to 30, and then study the result and find out the most suitable and optimal value of tn.

So far, you have seen ping sweep by multithreading; now, I have written a multithreading program with the TCP scan method:

import threading

import time

import socket, subprocess,sys

import thread

import collections

from datetime import datetime

'''section 1'''

net = raw_input("Enter the Network Address ")

st1 = int(raw_input("Enter the starting Number "))

en1 = int(raw_input("Enter the last Number "))

en1=en1+1

dic = collections.OrderedDict()

net1= net.split('.')

a = '.'

net2 = net1[0]+a+net1[1]+a+net1[2]+a

t1= datetime.now()

'''section 2'''

class myThread (threading.Thread):

def __init__(self,st,en):

threading.Thread.__init__(self)

self.st = st

self.en = en

def run(self):

run1(self.st,self.en)

'''section 3'''

def scan(addr):

sock= socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM)

socket.setdefaulttimeout(1)

result = sock.connect_ex((addr,135))

if result==0:

sock.close()

return 1

else :

sock.close()

def run1(st1,en1):

for ip in xrange(st1,en1):

addr = net2+str(ip)

if scan(addr):

dic[ip]= addr

'''section 4'''

total_ip =en1-st1

tn =20 # number of ip handled by one thread

total_thread = total_ip/tn

total_thread=total_thread+1

threads= []

try:

for i in xrange(total_thread):

#print "i is ",i

en = st1+tn

if(en >en1):

en =en1

thread = myThread(st1,en)

thread.start()

threads.append(thread)

st1 =en

except:

print "Error: unable to start thread"

print "\t Number of Threads active:", threading.activeCount()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print "Exiting Main Thread"

dict = collections.OrderedDict(sorted(dic.items()))

for key in dict:

print dict[key],"-->" "Live"

t2= datetime.now()

total =t2-t1

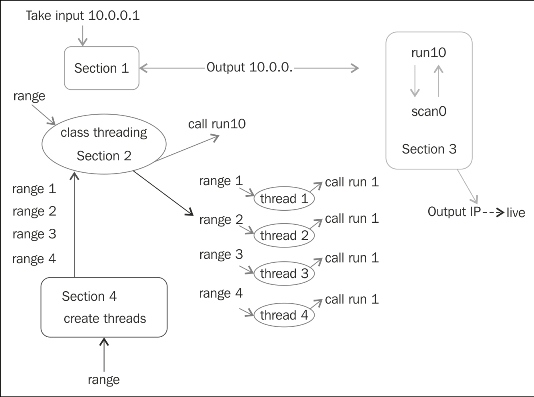

print "scanning complete in " , totalThere should be no difficulty in understanding the program. The following image shows everything:

The IP TCP scanner

The class takes a range as the input and calls the run1() function. The section 4 section creates a thread, which is the instance of a class, takes a short range, and calls the run1() function. The run1() function has an IP address, takes the range from the threads, and produces the output.

The output of the iptcpscan.py program is as follows:

G:\Project Snake\Chapter 2\ip>python iptcpscan_t.py Enter the Network Address 10.0.0.1 Enter the starting Number 1 Enter the last Number 60 Number of Threads active: 4 Exiting Main Thread 10.0.0.5 -->Live 10.0.0.13 -->Live scanning complete in 0:00:20.018000

For 60 IPs in 20 seconds, performance is not bad. As an exercise for you, combine both the scanners into one scanner.