Welcome to Scapy, the Python library that is designed to manipulate, send, and read packets. Scapy is one of those tools that have a large amount of applicability, but it can seem complex to use. Before we set off, there are some basic rules to understand about Scapy that will make creating scripts much easier.

Firstly, refer to the previous sections to understand the TCP flags and how they are represented in Scapy. You will need to look at the flags mentioned earlier and their relevant positions to use them. Secondly, when Scapy receives responses for a packet sent, the flags are represented by binary bits in octal format within the 13th octet of a TCP header. So, you have to read the response based on this information.

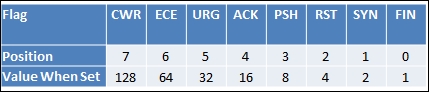

Look at the following table, which represents the binary positional values of each flag as it is set:

So when you are reading the responses from the TCP packets and looking for a specific type of flag, you have to do the math. The preceding table will help simplify this for you, but keep in mind if you have ever played with or worked with tcpdump that the material transmitted is identical. As an example, if you were looking for an SYN packet, you would see the value of the 13th octet as 2. If it was SYN + ACK, it would be a value of 18. Simply add the flag values together and you will have what you are looking for.

The next thing to keep in mind is that if you try to ping the loopback interface or localhost, the packet will not be assembled. This is because the kernel intercepts the request and processes it internally through the TCP/IP stack of the system. This is one of the errors that people get stuck with on with Scapy and often quit. So, instead of digging into fixing your packets so that they can hit your own Kali instance, spin up your Metasploitable instance or try and test your default gateway.

Tip

If you want to understand more about testing loopback interfaces or the localhost value, you can find the solution at http://www.secdev.org/projects/scapy/doc/troubleshooting.html.

Therefore, we are going to highlight testing a connection and then scanning a web port with Scapy. You have to understand that Scapy has multiple ways of sending and receiving packets, and depending on the data you want to extract, complex methods may not be necessary. First, look at what you are trying to accomplish. If you want to remain independent of the operating system, the two methods you should use are sr() for layer 3 and srp() for layer 2. Next, if the method has 1 after the function name but before the () sign, such as sr1(), it means that it returns only the first answer. This can be plenty to achieve most results, but if there are multiple packets in a stream that need to be evaluated, you will want to forego these types of methods.

Next is the send() method, which uses the operating system defaults for layer 2 and some operating system capabilities for layer 3 and above. Finally, there is sendp(), which uses a custom layer 2 header. This can be created using the Ether() method to represent the Ethernet frame header. This is extremely useful for wireless networks or locations where Virtual Local Area Networks (VLANs) are used to segment networks based on theoretical security. This is because wireless communication operates at layer 2, and VLANs are identified in this layer as well.

Note

Access Control Lists (ACL) based on VLANs are considered a cause of annoyance by most assessors, not security. This is because in most networks, you can easily hop network segments by manipulating the header of layer 2 frames. As you gain more experience, you will regularly see examples of this on live networks.

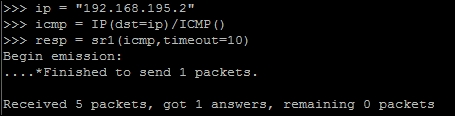

So, import the Scapy library and then set a variable with the destination IP address you want to ping. Create a packet that will contain the communication details and flags that you want sent to the target host. Then set a response variable to catch the results of the sr1() function:

#!/usr/bin/env python

try:

from scapy.all import *

except:

sys.exit("[!] Install the scapy libraries with: pip install

scapy")

ip = "192.168.195.2"

icmp = IP(dst=ip)/ICMP()

resp = sr1(icmp, timout=10)

Now that you see that you got one answer, it means that the host is most likely up. You can validate it with the following test:

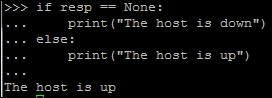

if resp == None:

print("The host is down")

else:

print("The host is up")When you test this, you can see that the results of the ping scan were successful, as follows:

We successfully pinged the host and validated the response variable by proving that it was not empty. From this, we can now check whether it has a web port open. To accomplish this, we will execute an SYN scan. Before doing this, however, understand that when you receive a response from the connection attempt, you receive both the answers and the unanswered data. So, the best thing to do is separate the two of them, and thanks to Scapy and Python syntax, this is extremely easy. You simply pass the response to two different variables, the first being the answers and the second being the unanswered, as shown here:

answers,unanswers = sr1(icmp, timout=10)

With this simple change, you now have the data returns cleaned up for easier manipulation. Furthermore, you can get summaries from these details by simply appending .summary() to answers or unanswers. If you are iterating through a list of ports from 0 to 1024, you can look at the specific results by a specific port by passing the value to the answers variable by position in the list. So, if you want to see the results from a scan at port 80 for the answers, you can pass the value to the list like this: answers[80]. This holds both sent and received packets for these answers, but these can further be split just like the previous example, as shown in this code:

sent, received = answers[80]

Keep in mind that this example only works for port 80, as you designated the location you wanted to pull the data from. If you had not passed a positional value to the answers variable, you would have put all the sent packets in the sent variable and all the received packets in the received variable.

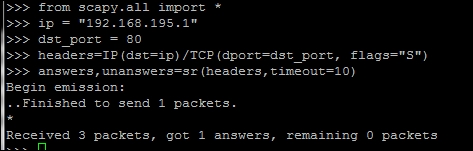

Now that you have the basics listed, you can develop a packet, send it to a target, and receive the results. One thing to cover before moving forward is how easy it is to build a packet from the ground up, which involves building the IP header first and then the TCP header. Next, you pass the data to the scanner, which identifies the target as either alive or not. You can configure it so that there is no timeout value, but I highly discourage this as you may have to wait forever with no return. The following script was run to identify the 192.168.195.1 host and determine whether a web port was open:

#!/usr/bin/env python from scapy.all import * ip = "192.168.195.1" dst_port = 80 headers=IP(dst=ip)/TCP(dport=dst_port, flags="S") answers,unanswers=sr(headers,timeout=10)

As you can see in the following screenshot, the system responded with an answer. The preceding script can run standalone, or you can use the interactive interpreter to execute each line, as shown here:

Now the details can be extracted from the answers variable. Remember that this is a list, so you should increment each of the values. The first packet sent would be represented by position 0, so each location after that represents the IP packets received after the original:

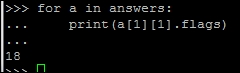

for a in answers:

print(a[1][1].flags)Here is what the catch is, though each value in the list is actually another list with more data in it. In Python, we call this a matrix, but do not fret! It is pretty easy to navigate. First, remember that we used the sr() function, so this means that the results will be from layer 3 and above. Each embedded list is for the protocol above it; in this case, it will be TCP. We performed a SYN scan, so we are looking for a SYN + ACK response. Look at the preceding section to compute the value you are looking for. As you can see by referencing the preceding section related to TCP flags, the value you are looking for in header is 18 to verify a SYN + ACK response, which can be calculated by adding the positional value of ACK = 16 and the positional value of SYN = 2. The following screenshot shows the actual result, which shows that the port is open. Understanding these concepts will allow you to use Scapy in future scripts.

You now have a basic understanding of Scapy, but don't worry! You are not done with it yet. Scapy has a significant amount of capability, which we have only touched on, and it provides you with the means to not only execute simple scans, but also manipulate network traffic. Many embedded devices and Industrial Control Systems (ICS) use unique communication forms to provide command and control for other units. At other times, you will realize that you need to identify live devices when nmap is being blocked. Scapy can help you fulfill all of these tasks.