Templating HTML with Handlebars

Up to this point, the B4 application only emits static HTML that is completely known in advance. For example, the alert box contains the same Success message every time. What we really want is the ability to render HTML for dynamic strings. For this we need templates.

Now, it’s true that ECMAScript supports template strings that allow you to easily inject values into strings, and we’ve been taking liberal advantage of this feature throughout the book. Unfortunately, though, this technique can quickly introduce cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities when used with user-supplied data. To protect our app from XSS vulnerabilities, any content over which a user may have any control must be properly encoded.

For example, consider the case where we’ll show the name of a user’s bundle. You might naively implement that template like this:

| | // DO NOT USE! VULNERABLE TO XSS. |

| | export const bundleName = name => `<h2>${name}</h2>`; |

Here, the bundleName takes a name parameter and returns a string including the name surrounded by a pair of <h2> tags. What could go wrong?

It turns out that this kind of templating is trivially exploitable and easy to break accidentally. Consider if the name contains an <img> tag. Your app could be inadvertently showing images where they weren’t expected. Or worse, if the tag has an onload or onerror attribute, it could execute arbitrary JavaScript in the page!

Defending against these types of vulnerabilities is not easy, but fortunately you don’t have to do it yourself. Modern frameworks and templating libraries handle these concerns for you.

For the purposes of this book, we’ll use Handlebars, a minimal and stable templating library.[79] Handlebars can operate both as a client-side runtime library and as a build-time module on the Node.js side of things. We’ll use it as a client-side library because I’ve found that easier to set up, but if you wanted to integrate Handlebars compilation into webpack, there is a handlebars-loader plugin for webpack that can help with this.[80]

To use Handlebars, start by installing it with npm.

| | $ npm install --save-dev --save-exact handlebars@4.0.10 |

Next, open your app/templates.ts file. Instead of exporting static HTML strings, we’ll export compiled Handlebars templates. Update the file’s contents to look like this:

| | import * as Handlebars from '../node_modules/handlebars/dist/handlebars.js'; |

| | |

| | export const main = Handlebars.compile(` |

| | <div class="container"> |

| | <h1>B4 - Book Bundler</h1> |

| | <div class="b4-alerts"></div> |

| | <div class="b4-main"></div> |

| | </div> |

| | `); |

| | |

| | export const welcome = Handlebars.compile(` |

| | <div class="jumbotron"> |

| | <h1>Welcome!</h1> |

| | <p>B4 is an application for creating book bundles.</p> |

| | </div> |

| | `); |

| | |

| | export const alert = Handlebars.compile(` |

| | <div class="alert alert-{{type}} alert-dismissible fade in" role="alert"> |

| | <button class="close" data-dismiss="alert" aria-label="Close"> |

| | <span aria-hidden="true">×</span> |

| | </button> |

| | {{message}} |

| | </div> |

| | `); |

For each of the exported constants, now the HTML string is passed into Handlebars.compile. This produces a function that takes in an object—a map of parameters by name—and returns a string with the appropriate replacements having been made.

The first two templates are exactly the same as before. Both main and welcome take no parameters and simply return a static string. Using Handlebars.compile makes no real difference, but for consistency all of the exported members of templates.ts will be compiled template functions.

The third template, alert, takes an object with two members: a type and a message. The type value is used to complete the alert- CSS class, which sets the color of the alert box. The four choices are success (green), info (blue), warning (yellow), and danger (red). The message value fills in the body of the alert box.

Save this file, then open app/index.ts We need to update the use of the templates members to call methods instead of using the values as strings directly. Edit that file to look like the following:

| | import '../node_modules/bootstrap/dist/css/bootstrap.min.css'; |

| | import 'bootstrap'; |

| | import * as templates from './templates.ts'; |

| | |

| | // Page setup. |

| | document.body.innerHTML = templates.main(); |

| | const mainElement = document.body.querySelector('.b4-main'); |

| | const alertsElement = document.body.querySelector('.b4-alerts'); |

| | |

| | mainElement.innerHTML = templates.welcome(); |

| | alertsElement.innerHTML = templates.alert({ |

| | type: 'info', |

| | message: 'Handlebars is working!', |

| | }); |

The only difference with respect to templates.main and templates.welcome is that now they are called as templates.main and templates.welcome, respectively. Note that the call to templates.alert takes an object with both a type and a message parameter.

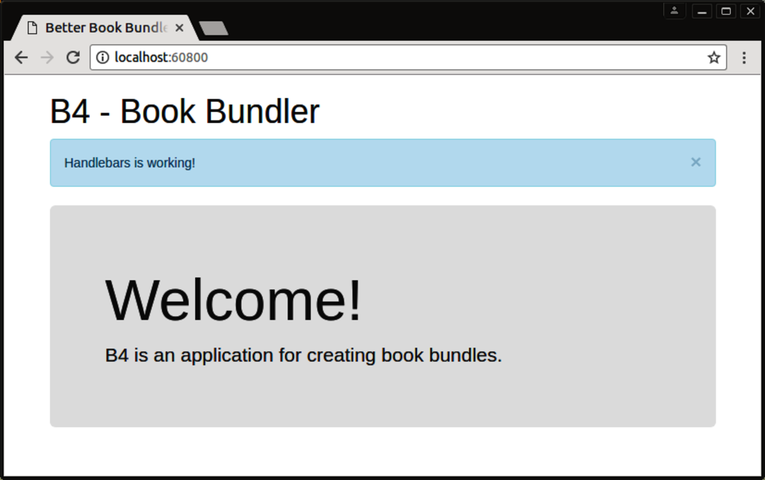

Once you save this file, the webpack dev server should pick up the changes and update localhost:60800 for you. It should now look like the following:

I know all of this probably seems like a lot of work to get such a simple page working, but rest assured, it’s setting the groundwork for more involved functionality coming up.

Next we’ll implement a simple URL hash-based routing to navigate through the app.