Pushing and Pulling Messages

So far we’ve worked with two major message-passing patterns: publish/subscribe and request/reply. ØMQ offers one more pattern that’s sometimes a good fit with Node.js—push/pull (PUSH/PULL).

Pushing Jobs to Workers

The PUSH and PULL socket types are useful when you have a queue of jobs that you want to assign among a pool of available workers.

Recall that with a PUB/SUB pair, each subscriber will receive all messages sent by the publisher. In a PUSH/PULL setup, only one puller will receive each message sent by the pusher.

A PUSH socket will distribute messages in a round-robin fashion to connected sockets, just like a DEALER. But unlike the DEALER/ROUTER flow, there is no backchannel. A message traveling from a PUSH socket to a PULL socket is one-way; the puller can’t send a response back through the same socket.

Here’s a quick example showing how to set up a PUSH socket and distribute 100 jobs. Note that the example is incomplete—it doesn’t call bind or connect—but it does demonstrate the concept:

| | const pusher = zmq.socket('push'); |

| | |

| | for (let i = 0; i < 100; i++) { |

| | pusher.send(JSON.stringify({ |

| | details: `Details about job ${i}.` |

| | }); |

| | } |

And here’s an associated PULL socket:

| | const puller = zmq.socket('pull'); |

| | |

| | puller.on('message', data => { |

| | const job = JSON.parse(data.toString()); |

| | // Do the work described in the job. |

| | }); |

Like other ØMQ sockets, either end of a PUSH/PULL pair can bind or connect. The choice comes down to which is the stable part of the architecture.

Using the PUSH/PULL pattern in Node.js brings up a couple of potential pitfalls hidden in these simple examples. Let’s explore them, and what to do to avoid them.

The First-Joiner Problem

The first-joiner problem is the result of ØMQ being so fast at sending messages and Node.js being so fast at accepting them. Since it takes time to establish a connection, the first puller to successfully connect can often pull many or all of the available messages before the second joiner has a chance to get into the rotation.

To fix this problem, the pusher needs to wait until all of the pullers are ready to receive messages before pushing any. Let’s consider a real-world scenario and how we’d solve it.

Say you have a Node.js cluster, and the master process plans to PUSH a bunch of jobs to a pool of worker processes. Before the master can start pushing, the workers need a way to signal back to the master that they’re ready to start pulling jobs. They also need a way to communicate the results of the jobs that they’ll eventually complete.

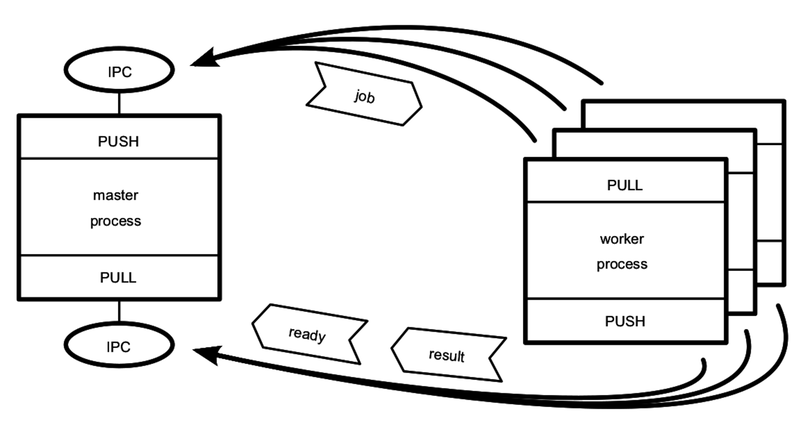

The following figure shows this scenario.

As in previous diagrams, rectangles are Node.js processes, ovals are resources, and heavy arrows point in the direction the connection is established. The job, ready, and result messages are shown as arrow boxes pointing in the direction they are sent.

In the top half of the figure, we have the main communication channel—the master’s PUSH socket hooked up to the workers’ PULL sockets. This is how jobs will be sent to workers.

In the bottom half of the figure, we have a backchannel. This time the master has a PULL socket connected to each worker’s PUSH sockets. The workers can PUSH messages, such as their readiness to work or job results, back to the master.

The master process is the stable part of the architecture, so it binds while the workers connect. Since all of the processes are local to the same machine, it makes sense to use IPC for the transport.

The bonus challenge in Bidirectional Messaging, will ask you to implement this PUSH/PULL cluster in Node.

The Limited-Resource Problem

The other common pitfall is the limited-resource problem. Node.js is at the mercy of the operating system with respect to the number of resources it can access at the same time. In Unix-speak, these resources are called file descriptors.

Whenever your Node.js program opens a file or a TCP connection, it uses one of its available file descriptors. When there are none left, Node.js will start failing to connect to resources when asked. This is a common problem for Node.js developers.

Strictly speaking, this problem isn’t exclusive to the PUSH/PULL scenario, but it’s very likely to happen there, and here’s why: since Node.js is asynchronous, the puller process can start working on many jobs simultaneously. Every time a message event comes in, the Node.js process invokes the handler and starts working on the job. If these jobs require accessing system resources, then you’re liable to exhaust the pool of available file descriptors. Then jobs will quickly start failing.

If your application starts to throw EMFILE or ECONNRESET errors under load, it means you’ve exhausted the pool of file descriptors.

A full discussion of how to manage the number of file descriptors available to your processes is outside the scope of this book, since it’s mainly influenced by the operating system. But you can generally work around these limitations in a couple of ways.

One way is to keep a counter that tracks how many tasks your Node.js process is actively engaged in. The counter starts at zero, and when you get a new task you increment the counter. When a task finishes, you decrement the counter. Then, when a task pushes the counter over some threshold, pause listening for new tasks (stop pulling), then resume when one finishes.

Another way is to offload the handling of this problem to an off-the-shelf module. The graceful-fs module is a drop-in replacement for Node.js’s built-in fs module.[33] Rather than choking when there are no descriptors left, graceful-fs will queue outstanding file operations until there are descriptors available.

Now it’s time to wrap up this chapter so we can move on to working with data from the wild.