How Node.js Applications Work

Node.js couples JavaScript with an event loop for quickly dispatching operations when events occur. Many JavaScript environments use an event loop, but it is a core feature of Node.js.

Node.js’s philosophy is to give you low-level access to the event loop and to system resources. Or, in the words of core committer Felix Geisendörfer, in Node.js “everything runs in parallel except your code.”[13]

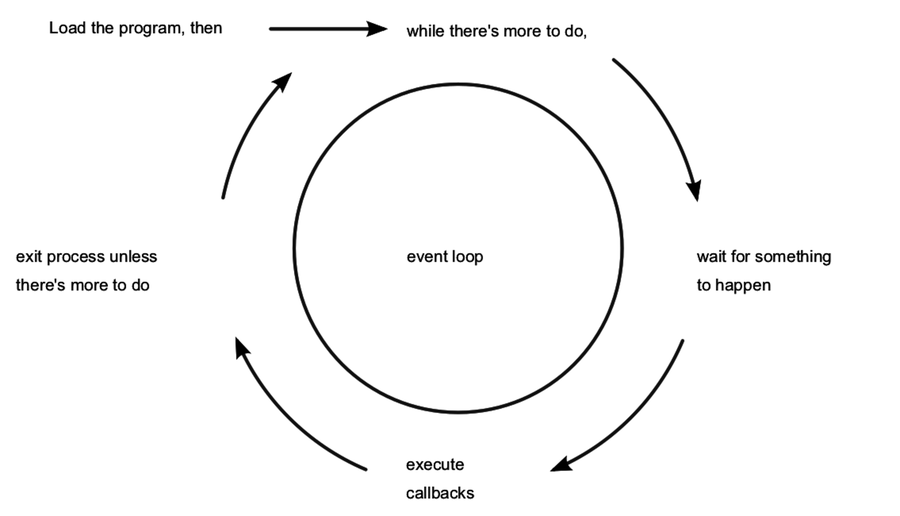

If this seems a little backward to you, don’t worry. The following figure shows how the event loop works.

As long as there’s something left to do, Node.js’s event loop will keep spinning. Whenever an event occurs, Node.js invokes any callbacks (event handlers) that are listening for that event.

As a Node.js developer, your job is to create the callback functions that get executed in response to events. Any number of callbacks can respond to any event, but only one callback function will ever be executing at any time.

Everything else your program might do—like waiting for data from a file or an incoming HTTP request—is handled by Node.js, in parallel, behind the scenes. Your application code will never be executed at the same time as anything else. It will always have the full attention of Node.js’s JavaScript engine while it’s running.

Single-Threaded and Highly Parallel

Other systems try to gain parallelism by running lots of code at the same time, typically by spawning many threads. But not Node.js. As far as your JavaScript code is concerned, Node.js is a single-threaded environment. At most, only one line of your code will ever be executing at any time.

Node.js gets away with this by doing most I/O tasks using nonblocking techniques. Rather than waiting line-by-line for an operation to finish, you create a callback function that will be invoked when the operation eventually succeeds or fails.

Your code should do what it needs to do, then quickly hand control back over to the event loop so Node.js can work on something else. We’ll develop practical examples of this throughout the book, starting in Chapter 2, Wrangling the File System.

If it seems strange to you that Node.js achieves parallelism by running only one piece of code at a time, that’s because it is. It’s an example of something I call a backwardism.

Backwardisms in Node.js

A backwardism is a concept that’s so bizarre that at first it seems completely backward. You’ve probably experienced many backwardisms while learning to program, whether you noticed them or not.

Take the concept of a variable. In algebra it’s common to see equations like 7x + 3 = 24. Here, x is called a variable; it has exactly one value, and your job is to solve the equation to figure out what that value is.

Then when you start learning how to program, you quickly run into statements like x = x + 7. Now x is still called a variable, but it can have any value that you assign to it. It can even have different values at different times!

From algebra’s perspective, this is a backwardism. The equation x = x + 7 makes no sense at all. The notion of a variable in programming is not just a little different than in algebra—it’s 100 percent backward. But once you understand the concept of assignment, the programming variable makes perfect sense.

So it is with Node.js’s single-threaded event loop. From a multithreaded perspective, running just one piece of code at a time seems silly. But once you understand event-driven programming—with nonblocking APIs—it becomes clear.

Programming is chock-full of backwardisms like these, and Node.js is no exception. Starting out, you’ll frequently run into code that looks like it should work one way, but it actually does something quite different.

That’s OK! With this book, you’ll learn Node.js by making compact programs that interact in useful ways. As we run into more of Node.js’s backwardisms, we’ll dive in and explore them.