Copyright © 2018 The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC. This book is licensed to the individual who purchased it. We don't copy-protect it because that would limit your ability to use it for your own purposes. Please don't break this trust—you can use this across all of your devices but please do not share this copy with other members of your team, with friends, or via file sharing services. Thanks.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters or in all capitals. The Pragmatic Starter Kit, The Pragmatic Programmer, Pragmatic Programming, Pragmatic Bookshelf and the linking g device are trademarks of The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC.

Every precaution was taken in the preparation of this book. However, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages that may result from the use of information (including program listings) contained herein.

The Pragmatic Bookshelf is an agile publishing company. We’re here because we want to improve the lives of developers. We do this by creating timely, practical titles, written by programmers for programmers.

Our Pragmatic courses, workshops, and other products can help you and your team create better software and have more fun. For more information, as well as the latest Pragmatic titles, please visit us at http://pragprog.com.

Our ebooks do not contain any Digital Restrictions Management, and have always been DRM-free. We pioneered the beta book concept, where you can purchase and read a book while it’s still being written, and provide feedback to the author to help make a better book for everyone. Free resources for all purchasers include source code downloads (if applicable), errata and discussion forums, all available on the book's home page at pragprog.com. We’re here to make your life easier.

Want to keep up on our latest titles and announcements, and occasional special offers? Just create an account on pragprog.com (an email address and a password is all it takes) and select the checkbox to receive newsletters. You can also follow us on twitter as @pragprog.

If you buy directly from pragprog.com, you get ebooks in all available formats for one price. You can synch your ebooks amongst all your devices (including iPhone/iPad, Android, laptops, etc.) via Dropbox. You get free updates for the life of the edition. And, of course, you can always come back and re-download your books when needed. Ebooks bought from the Amazon Kindle store are subject to Amazon's polices. Limitations in Amazon's file format may cause ebooks to display differently on different devices. For more information, please see our FAQ at pragprog.com/frequently-asked-questions/ebooks. To learn more about this book and access the free resources, go to https://pragprog.com/book/jwnode2, the book's homepage.

Thanks for your continued support,

Andy Hunt

The Pragmatic Programmers

The team that produced this book includes: Andy Hunt (Publisher)Janet Furlow (VP of Operations)Brian MacDonald (Managing Editor)Jacquelyn Carter (Supervising Editor)Candace Cunningham (Copy Editor)Potomac Indexing, LLC (Indexing)Gilson Graphics (Layout)

For customer support, please contact support@pragprog.com.

For international rights, please contact rights@pragprog.com.

Node.js 8 the Right Way is an excellent guide for building robust Node.js applications and making use of the extensive Node.js ecosystem. Using realistic applications from several different domains, it gives a highly useful and thorough description of the process of building, testing, and deploying real-world Node.js programs.

| → | Dan Scales |

| Principal Engineer, Google Inc. |

Without the original Node.js the Right Way, I wouldn’t be where I am today. This book leapfrogged me from being a casual Node.js developer to loving the event loop and knowing how to build effective distributed systems in Node.js. It led me to writing clean, idiomatic, and highly understandable JavaScript—both in Node.js and in the browser. This update will do the same for readers.

| → | Kyle Kelley |

| Senior Software Engineer, Netflix |

Jim’s update to his engaging, wide-ranging deep dive into how to solve actual problems using Node.js taught even this old dog some new tricks. Hats off to Jim for clearly demonstrating how to get the most out of Node.js.

| → | Mark Trostler |

| Software Engineer, Google Inc. |

Jim Wilson shows the correct way, the way that will definitely make you a better Node.js developer, giving you many techniques, insights, and—most of all—some really cool stuff. Node.js 8 the Right Way provides loads of good practices and reveals some of the lower-level interactions of Node with the system. In a Node.js shop, this book is a must for seniors’ reference and a must for new hires.

| → | Peter Perlepes |

| Software Engineer, Growth |

I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity to write this book. And I’m especially thankful for my editor, Jackie Carter—your thoughtful feedback made this book what it is today.

Thank you, dear reader, and readers of the Beta releases. Your errata reports made the book better than it would have otherwise been.

I’d also sincerely like to thank the whole team at The Pragmatic Bookshelf. Thanks for your kind patience, and all of your hard work to polish this book and find all of my mistakes.

I’d like to thank all of my reviewers. Your keen observations have helped make this book even more technically correct (the best kind of correct). In no particular order:

Dan Scales |

| Mark Ethan Trostler |

| Gary Chamberlain |

Rick Waldron |

| Nick Capito |

| Peter Hampton |

Luca Mezzalira |

| Peter Perlepes |

| Dominic Schulz |

| Maricris S. Nonato |

|

And I want to thank my amazing family, too. Dear Ruthy, you are my inspiration; never stop fighting! Emma and Jimmy, even though you’re both growing up too fast, I can’t wait to see all the great things you’ll do.

For anyone I missed, I hope you’ll accept my apologies. Any omissions were certainly not intentional, and I have nothing but gratitude for you in my heart.

In recent years, two big shifts have happened in the practice of writing software—and Node.js has been at the forefront of both.

First, software is becoming increasingly asynchronous. Whether you’re waiting on a Big Data job, interacting with end users, steering a quadcopter, or simply responding to an API call, chances are you’ll need asynchronous programming techniques.

Second, JavaScript has quietly become the world’s standard code-execution environment. It’s everywhere: in web browsers, modern NoSQL databases, DIY robots, and now on the server as well.

Node.js is an integral part of these trends, and it has taken off in a big way.

Way back in March of 2010, I gave a lightning talk titled “Full-Stack JavaScript” at the NoSQL Boston conference. Back then, and even more so now, I knew that using JavaScript for every layer of the application stack was not only possible, but was a great way to reduce software complexity.

When each layer of your stack speaks JavaScript, you sidestep impedance mismatches and facilitate code reuse. Node.js is an important piece of the puzzle, filling the middle space between your front-end user-facing code and your data-storage layer.

The Right Way in this book’s title refers to both the process of learning Node.js and the practice of writing Node.js code.

As with any growing technology, there are plenty of resources available for learning Node.js. Unfortunately, many of those resources are narrowly focused on serving up web resources.

The web is great, but it’s not enough, and it’s not the whole story of Node.js. Node.js is about more than just serving web apps, and this book treats it that way.

Node.js 8 the Right Way teaches you the concepts you’ll need to be an effective Node.js programmer, no matter what kinds of programs you need to write.

One thing I love about JavaScript is that there are seven ways to do anything. There’s breathing room, where developers can explore and experiment and find better approaches to everything.

The community of Node.js developers, the conventions in Node.js development, and even the semantics of the JavaScript language itself are all rapidly evolving. With eyes to the near future, the code examples and recommendations in this book reflect current best practices and standards.

This book is for intermediate to advanced developers who want to learn how to write asynchronous JavaScript for the server using Node.js. Some prior JavaScript experience will definitely help, but you don’t have to be an expert.

The book proceeds in three parts, outlined here briefly.

Part I is about getting you up to speed on Node.js 8. You’ll write Node.js programs that use core modules—and a few external modules as well—to do things like interact with the filesystem, spin up a cluster of worker processes, and manage network connections.

Chapter 1, Getting Started, introduces the Node.js event loop, explaining how it empowers Node.js to be highly parallel and single-threaded at the same time. This chapter also outlines the five aspects of Node.js development that frame each subsequent chapter and has some brief instructions on getting Node.js installed on your machine.

In Chapter 2, Wrangling the File System, you’ll start writing Node.js programs. If you’ve done any server-side programming in the past, chances are you’ve had to access a filesystem along the way. We’ll start in this familiar domain, using Node.js’s filesystem tools to create asynchronous, nonblocking file utilities. You’ll use Node.js’s ubiquitous EventEmitter and Stream classes to pipe data, and you’ll spawn and interact with child processes.

We’ll expand on those concepts while exploring Node.js’s network I/O capabilities in Chapter 3, Networking with Sockets. You’ll create TCP servers and client programs to access them. You’ll also develop a simple JSON-based protocol and a custom class for working with these messages. To develop unit tests for the code, you’ll use Mocha, a popular Node.js test harness.

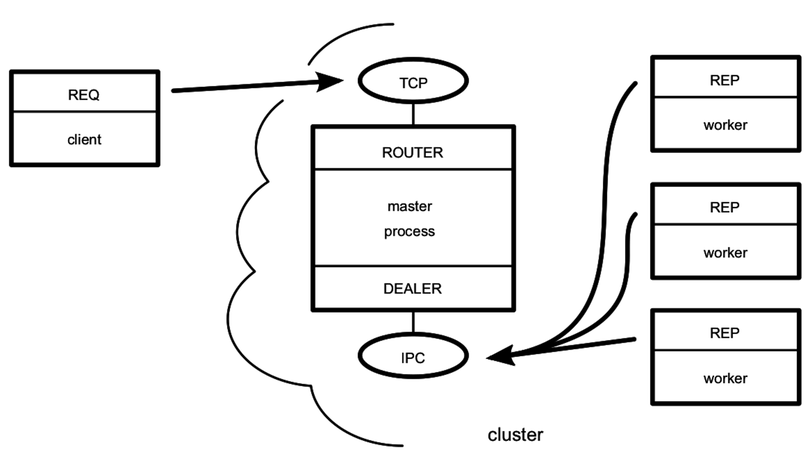

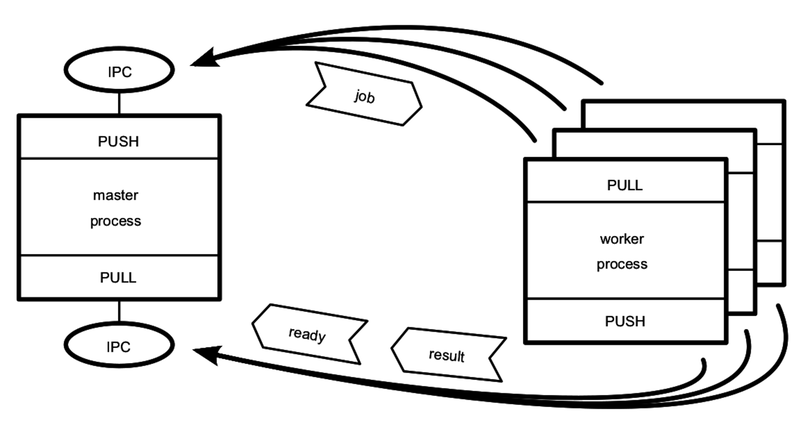

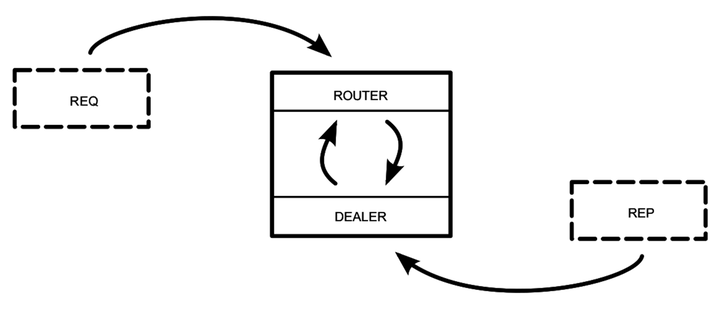

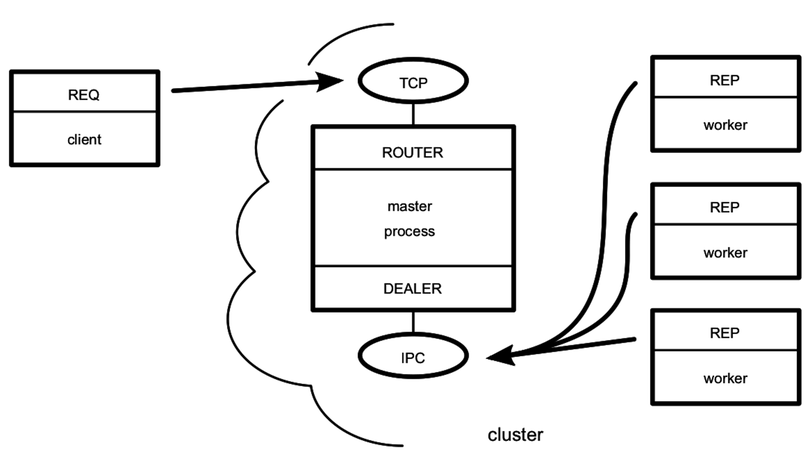

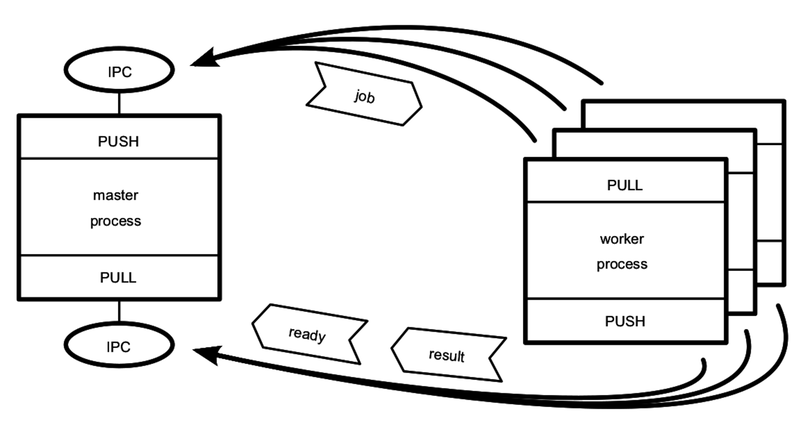

Then, in Chapter 4, Connecting Robust Microservices, we’ll branch away from the Node.js core and into the realm of third-party libraries. You’ll use npm to import ØMQ (pronounced “Zero-M-Q”)—a high-efficiency, low-latency library for developing networked applications. With ØMQ, you’ll develop programs that communicate using several important patterns, such as publish/subscribe and request/reply. You’ll create suites of programs that work together in concert, and you’ll learn the clustering tools to manage them.

In Part II, you’ll work with real data and lay the groundwork for an end-to-end application. This starts with processing data files in a testable way. You’ll also learn to compose rich command-line utilities using Node.js and interact with HTTP services.

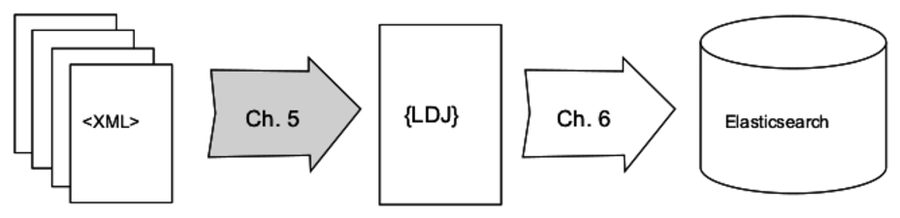

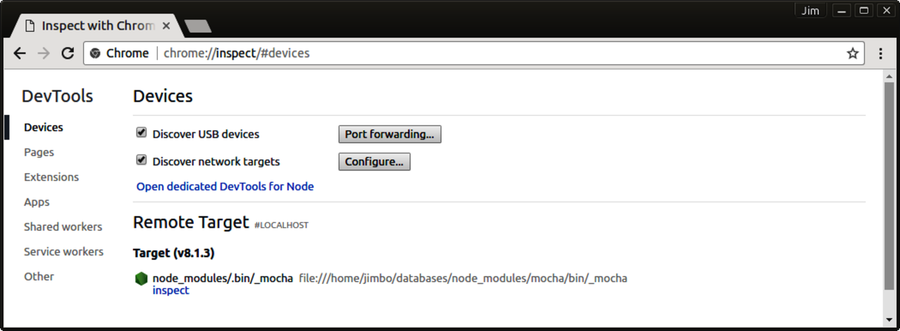

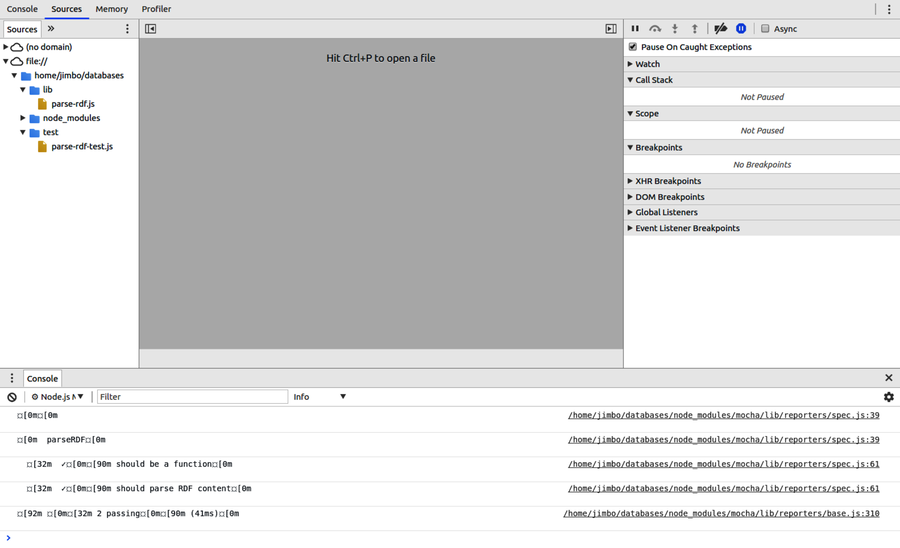

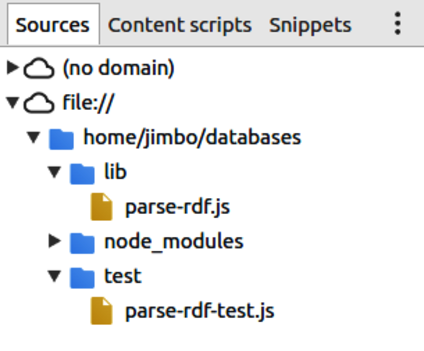

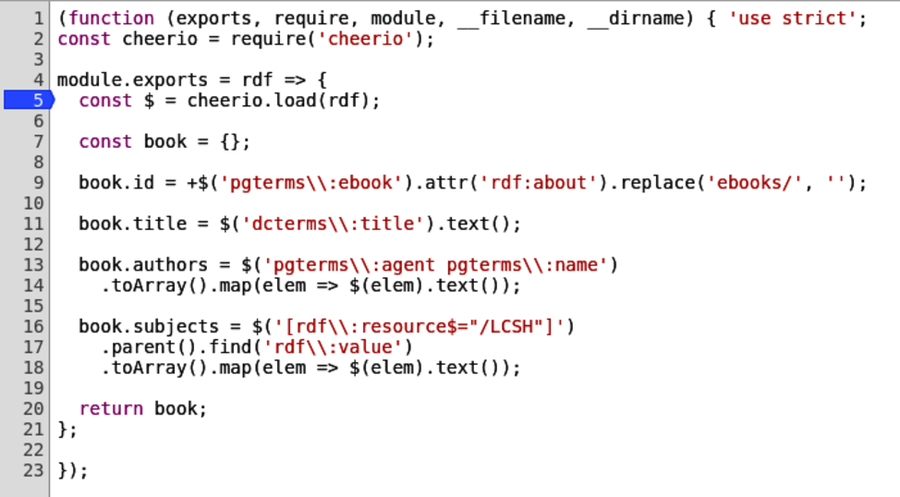

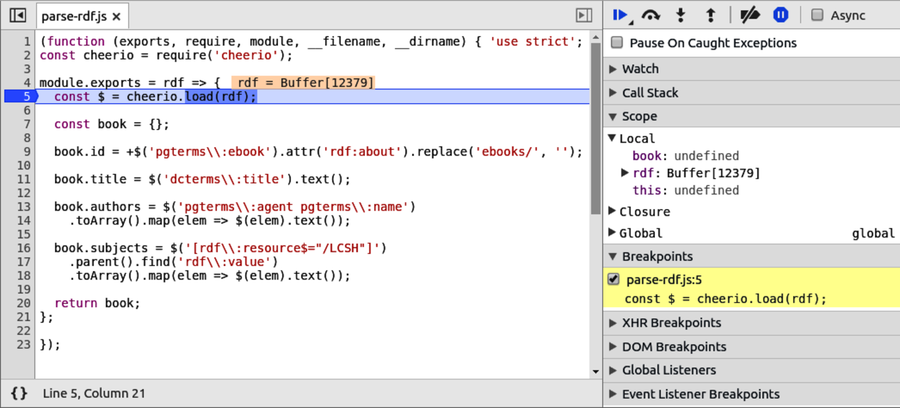

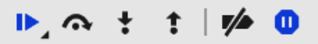

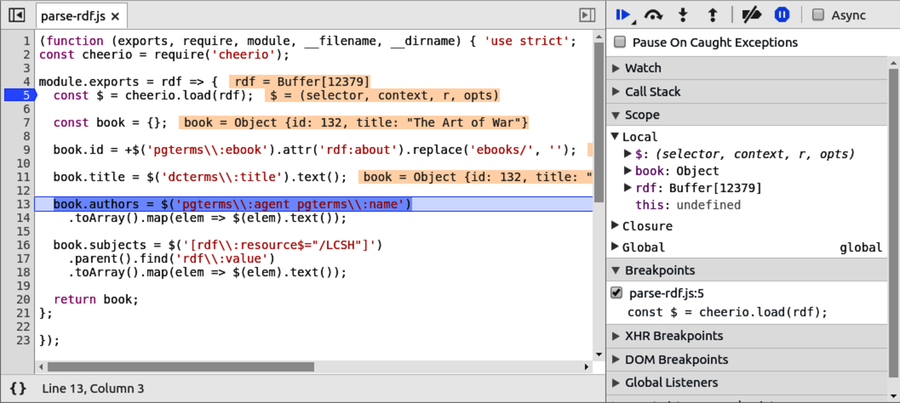

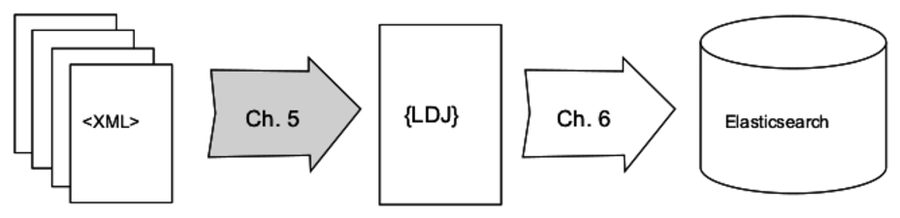

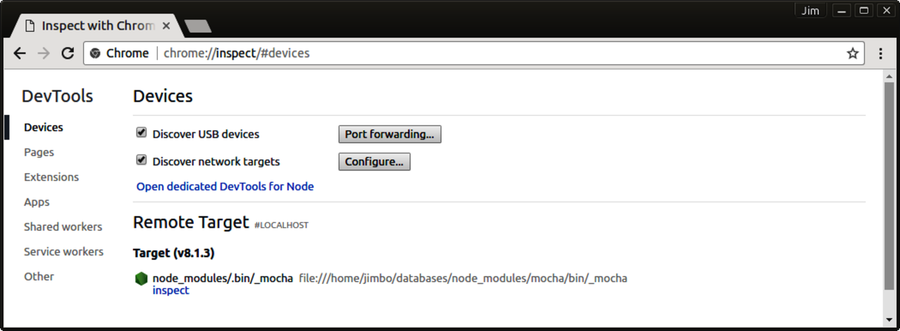

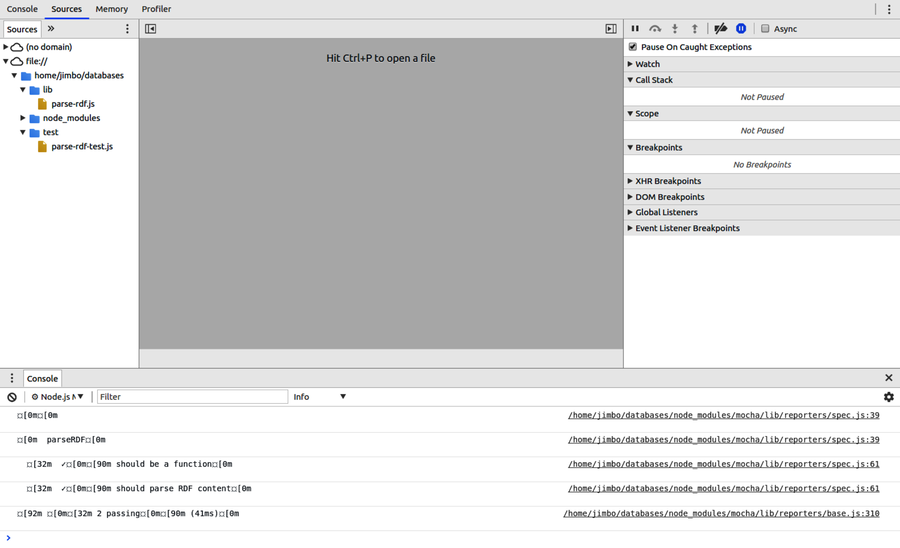

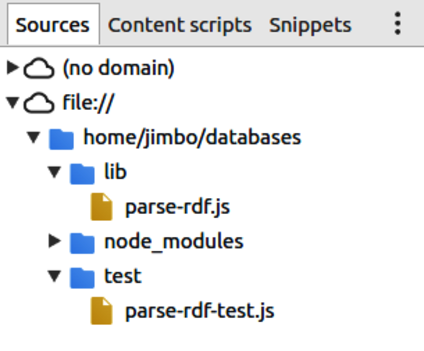

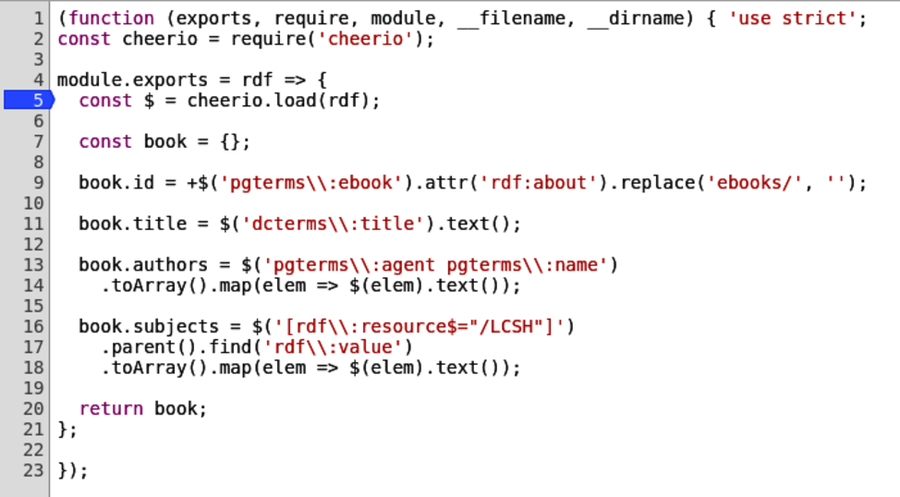

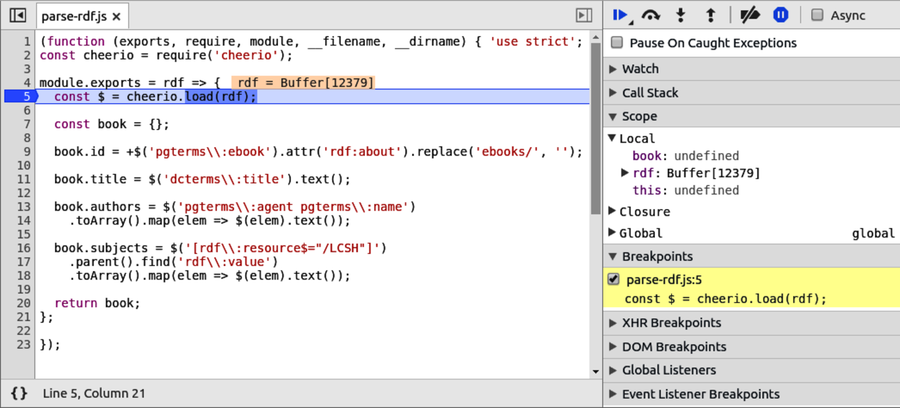

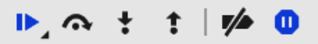

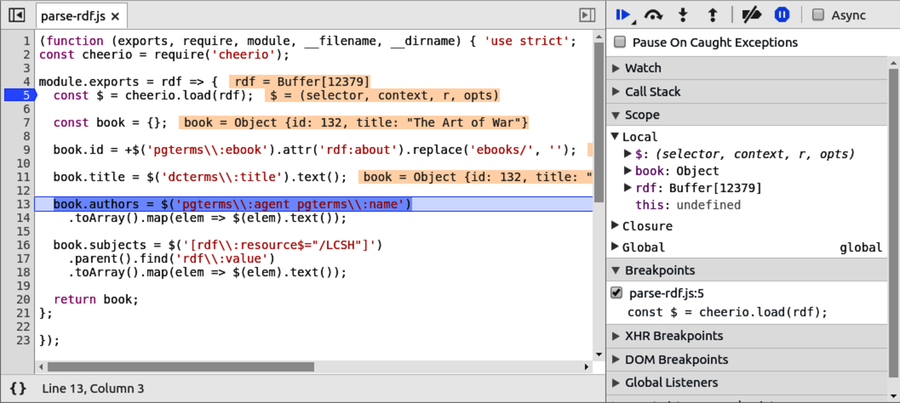

Chapter 5, Transforming Data and Testing Continuously, kicks off an ongoing project that spans Part II and Part III. You’ll download the catalog from Project Gutenberg, an online resource for ebooks in the public domain. Using a module called Cheerio, you’ll write Node.js code to parse the data files and extract the important fields. You’ll use npm, Mocha, and an assertion library called Chai to set up continuous testing, and you’ll learn to use Chrome DevTools for interactive debugging.

In Chapter 6, Commanding Databases, you’ll insert the extracted Project Gutenberg catalog into an Elasticsearch index. To get this done, you’ll write a command-line utility program called esclu using a Node.js module called Commander. Since Elasticsearch is a RESTful, JSON-based datastore, you’ll use the Request module to interact with it. You’ll also learn to use a handy and powerful command-line tool called jq for manipulating JSON.

Part III is where everything comes together. You’ll develop web services that mediate between your API users and your back-end data services. End users don’t interact directly with APIs, though, so for that you’ll implement a beautiful UI. At the end, you’ll tie it all together with session management and authentication.

Node.js has fantastic support for writing HTTP servers, and in Chapter 7, Developing RESTful Web Services, you’ll do exactly that. You’ll use Express, a popular Node.js web framework for routing requests. We’ll dive deeper into REST semantics, and you’ll use Promises and async functions for managing code flows. In addition, you’ll learn to configure your services using the nconf module, and keep them running with nodemon.

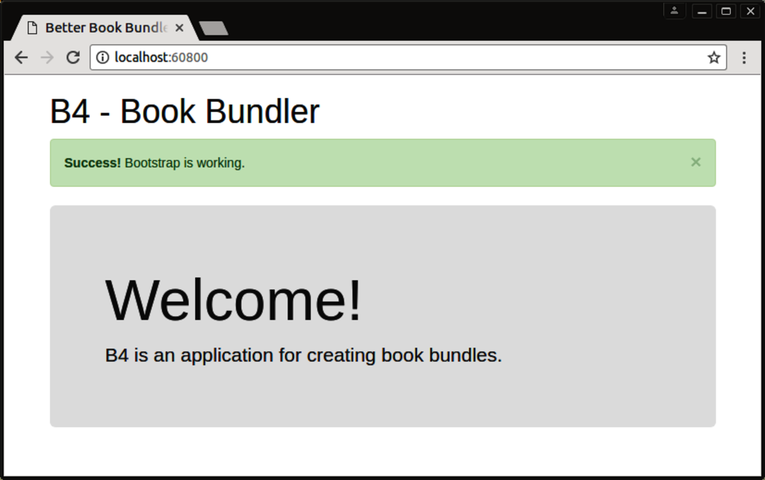

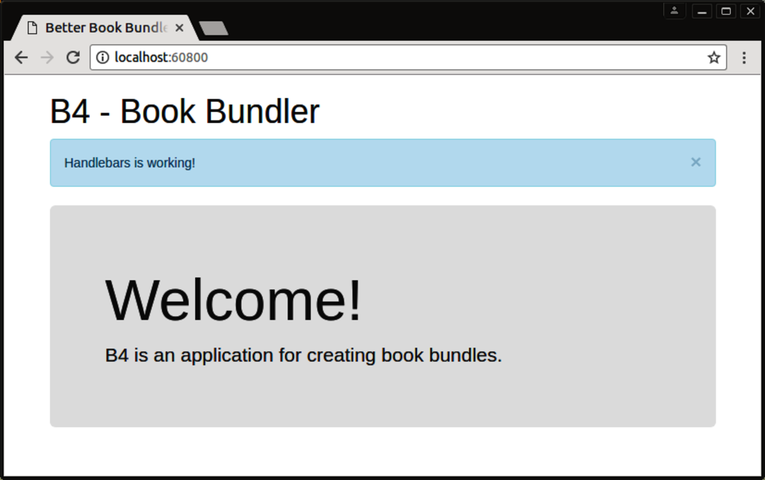

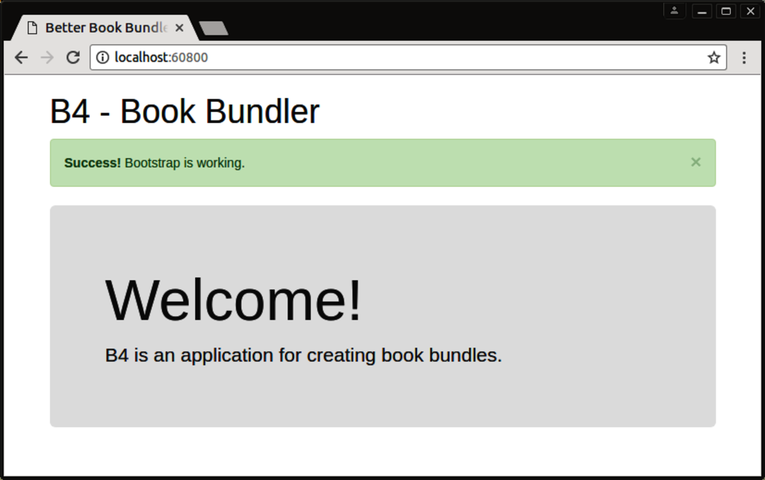

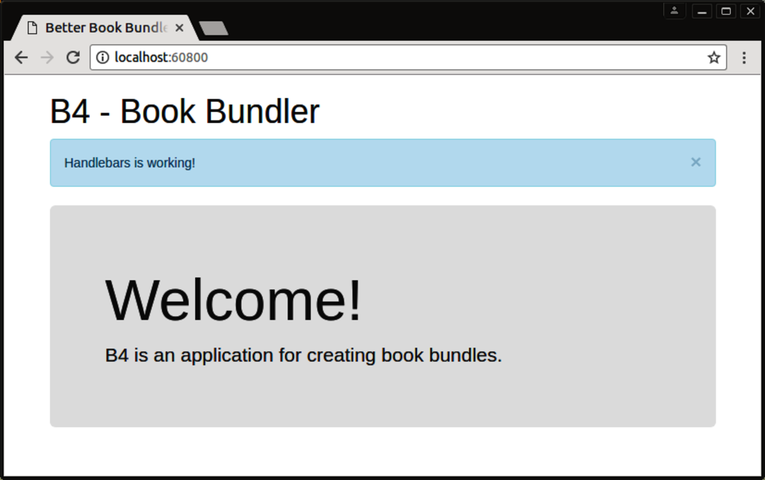

With the web services in place, in Chapter 8, Creating a Beautiful User Experience, you’ll craft a front end for them. You’ll learn how to assemble a front-end project using a Node.js-based build tool called webpack, along with a host of peer-dependency plugins for it. You’ll transpile your code for consumption by the browser using TypeScript, a language and transpiler from Microsoft that features inferred type checking. To make your UI look modern and fabulous, you’ll bring in Twitter’s Bootstrap styling framework, and implement templating with Handlebars.

Chapter 9, Fortifying Your Application, is where everything comes together. You’ll combine the user experience with the web services from the previous two chapters for an end-to-end solution. Using Express middleware, you’ll create authenticated APIs and implement stateful sessions. You’ll also learn how to use npm’s shrinkwrap option to insulate yourself from upstream module changes.

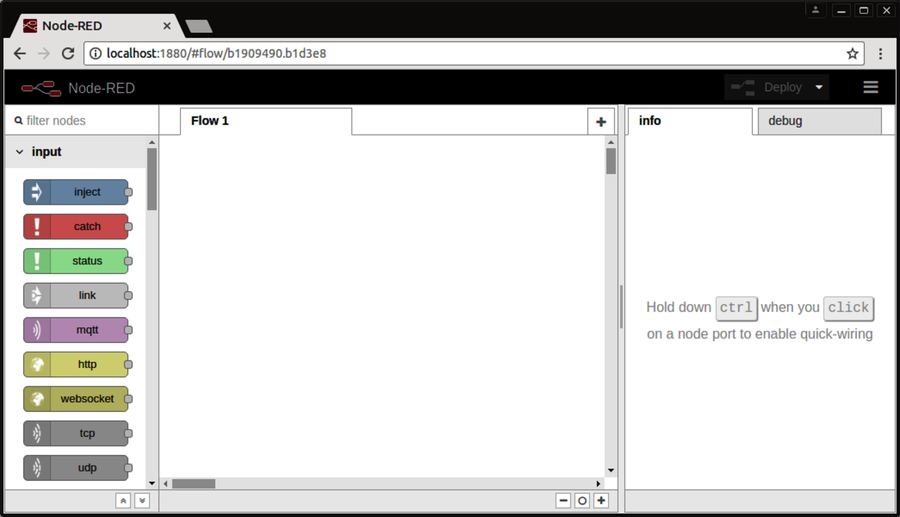

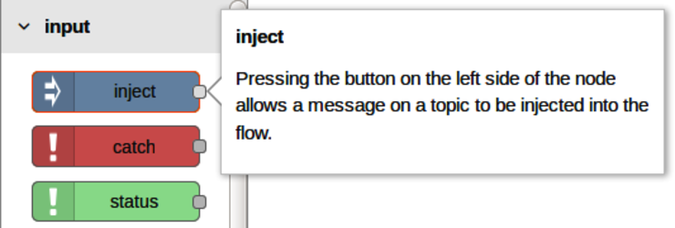

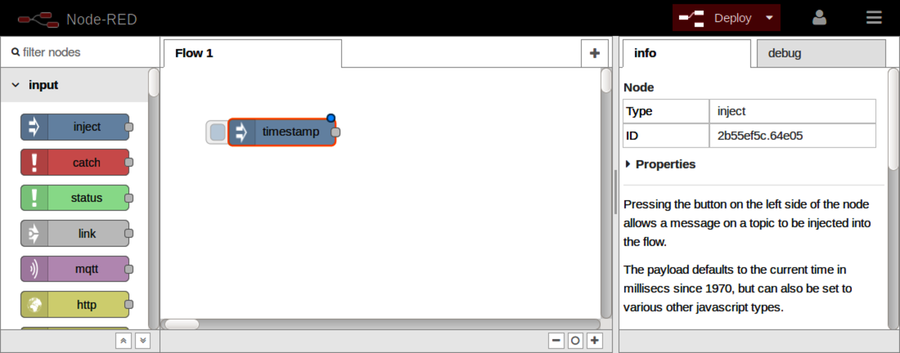

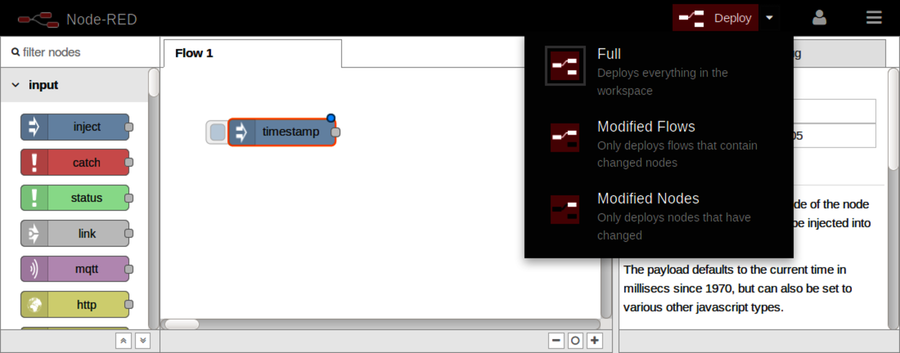

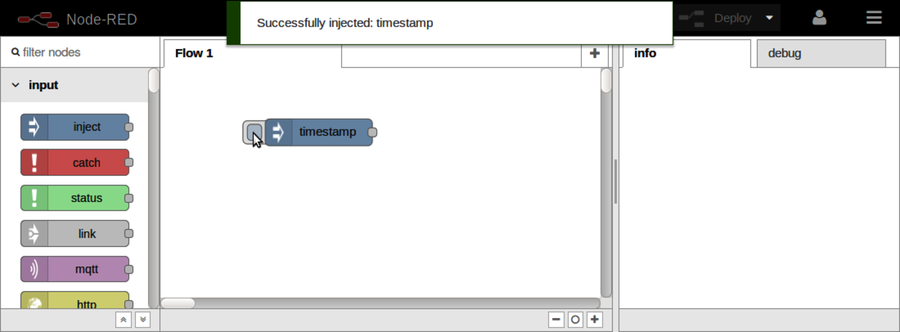

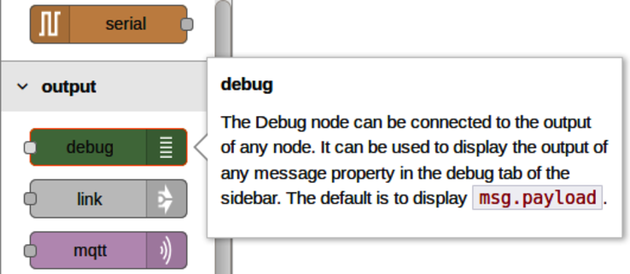

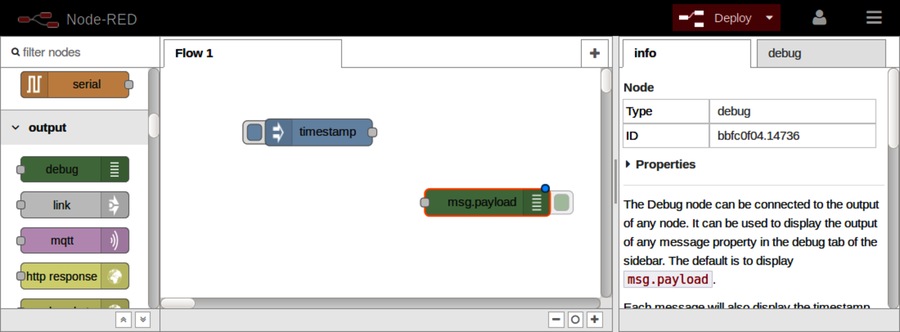

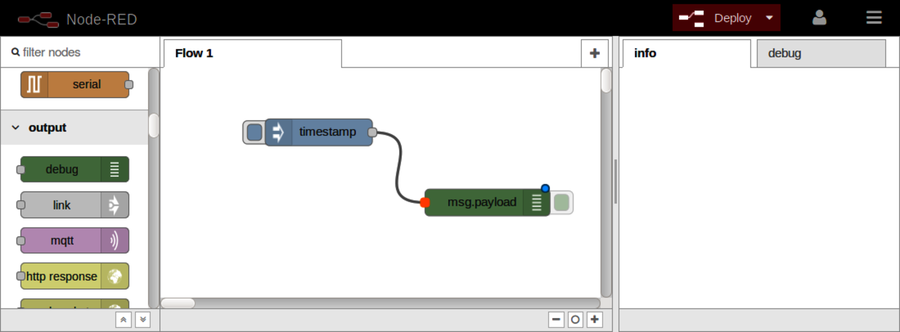

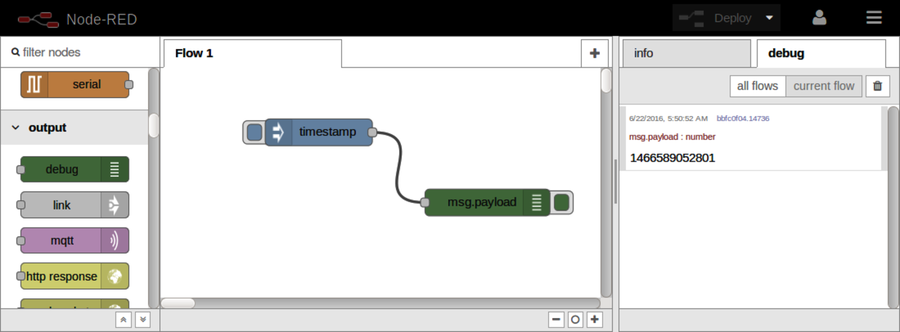

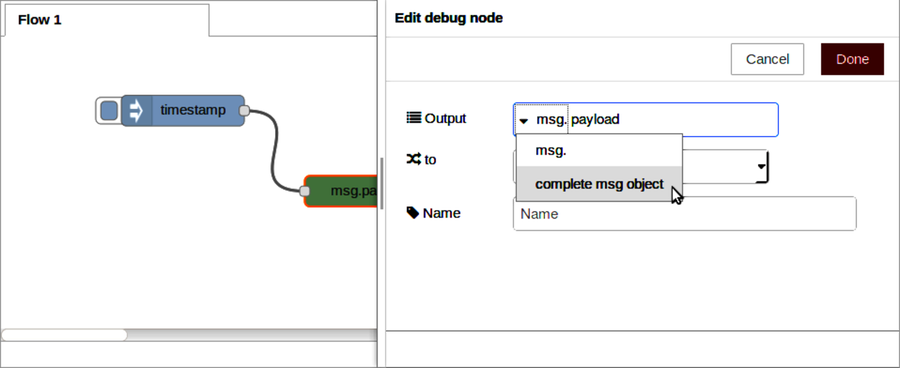

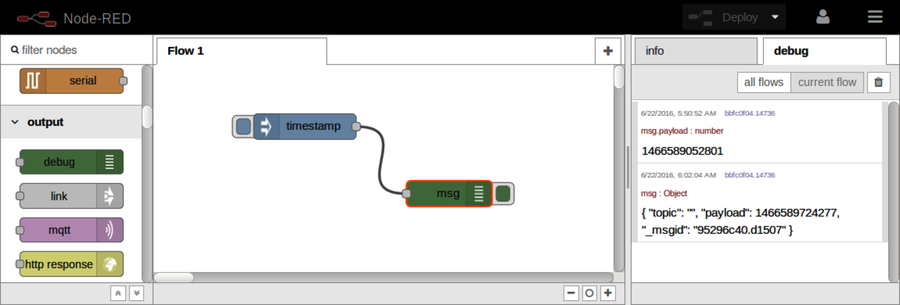

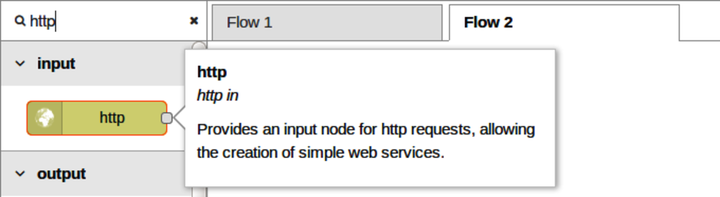

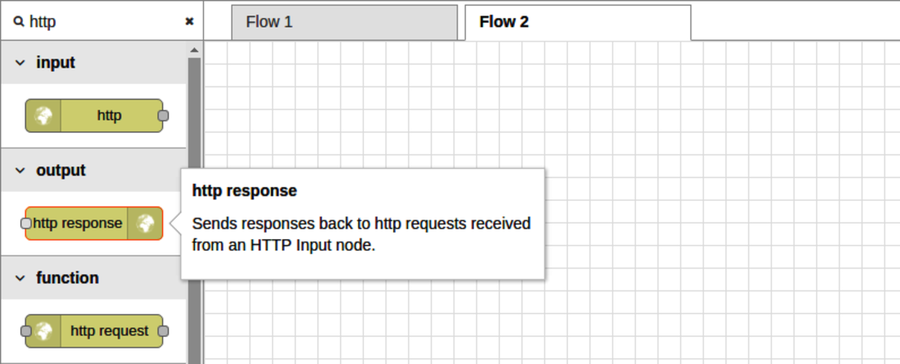

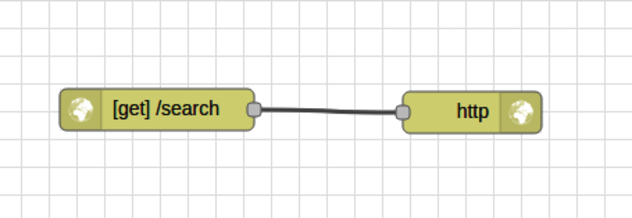

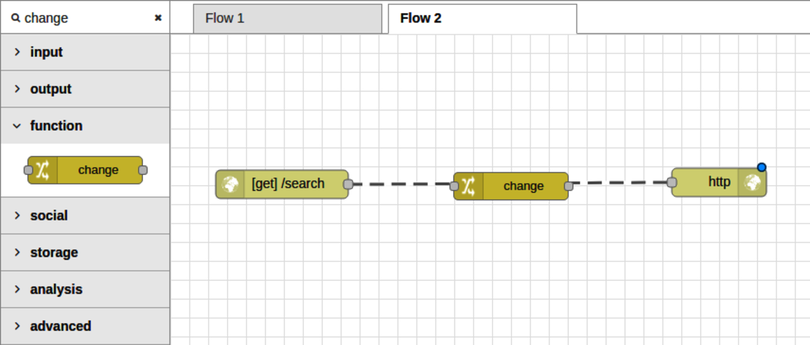

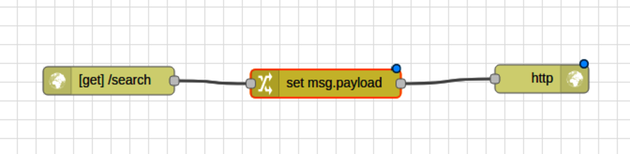

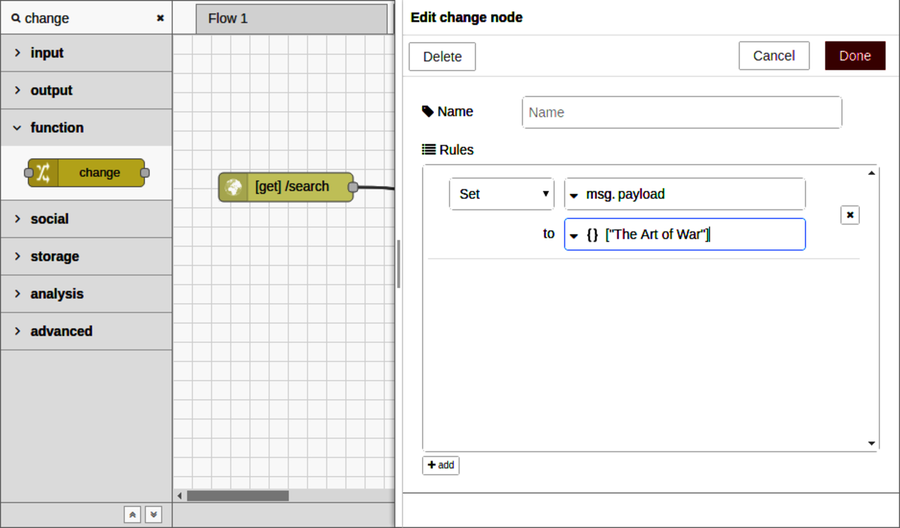

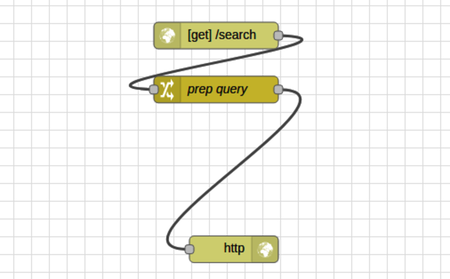

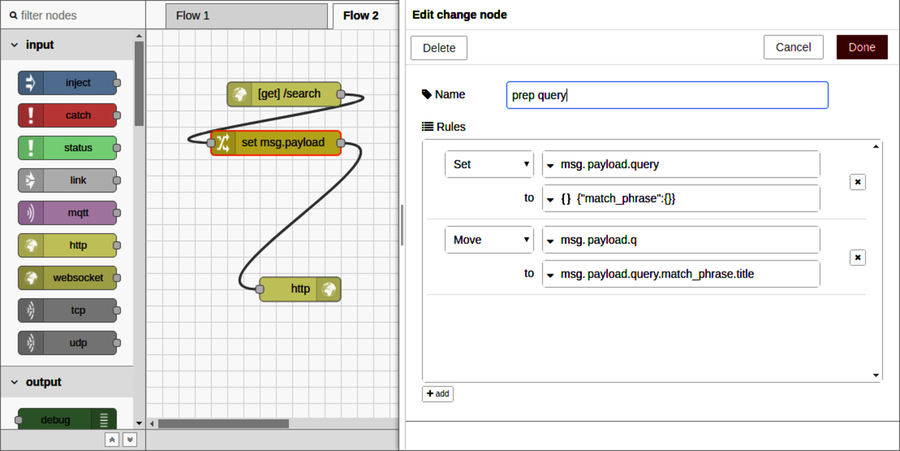

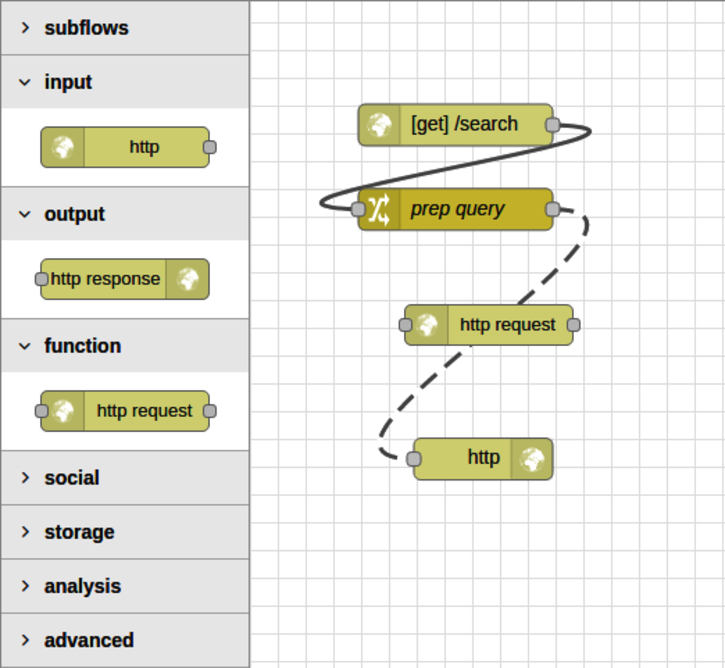

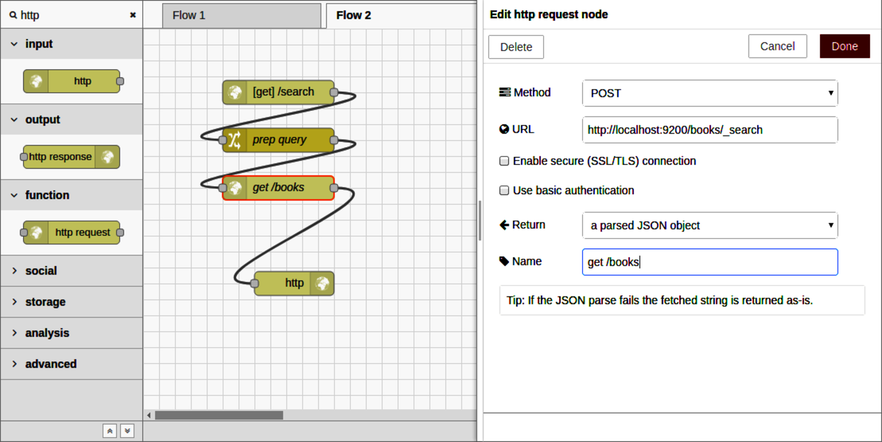

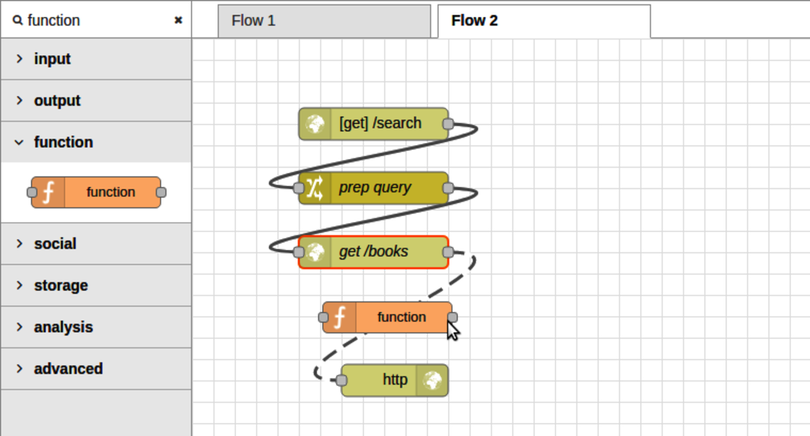

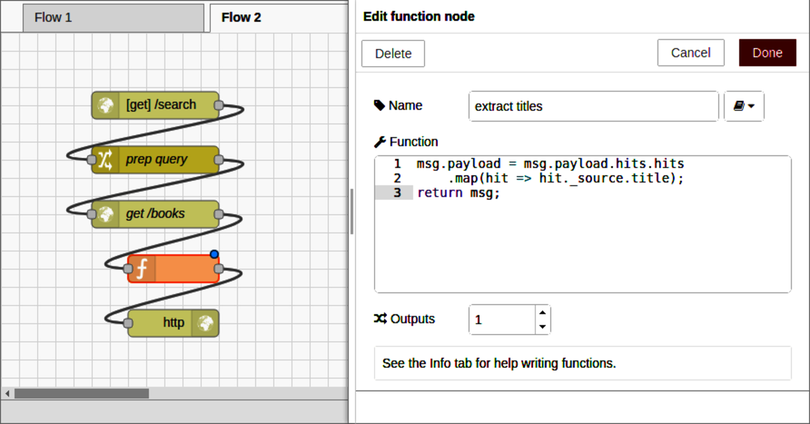

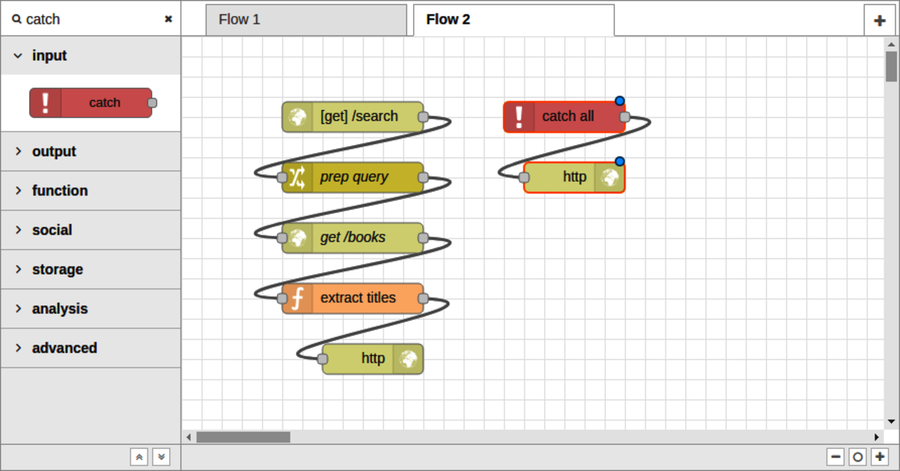

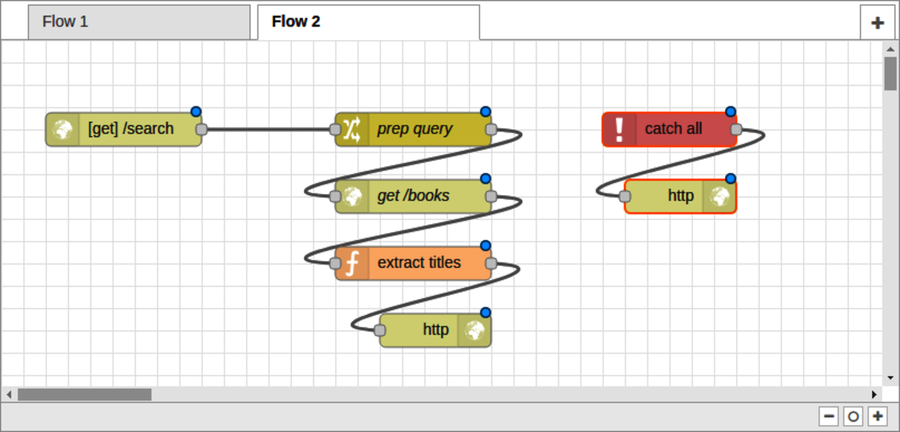

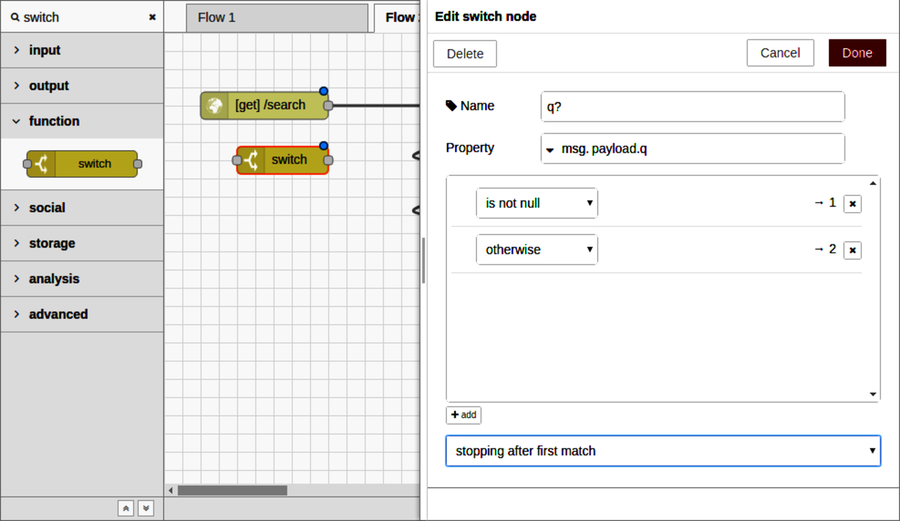

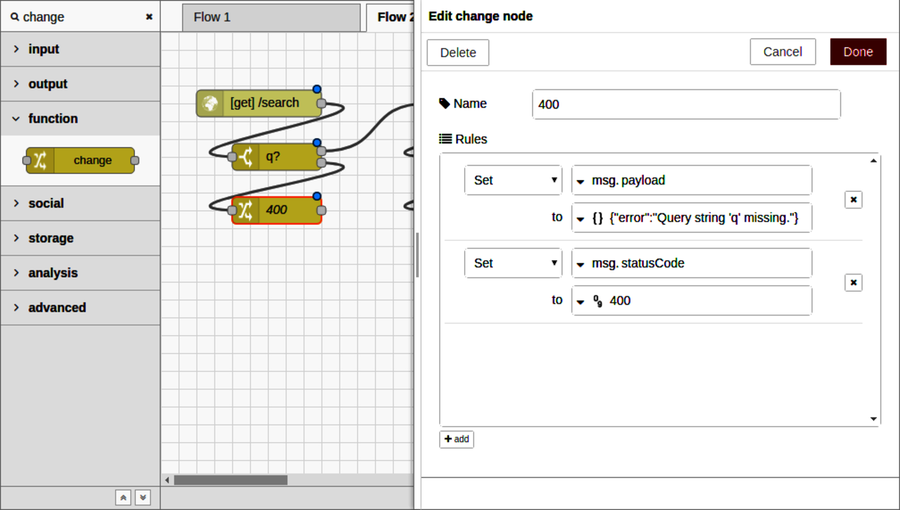

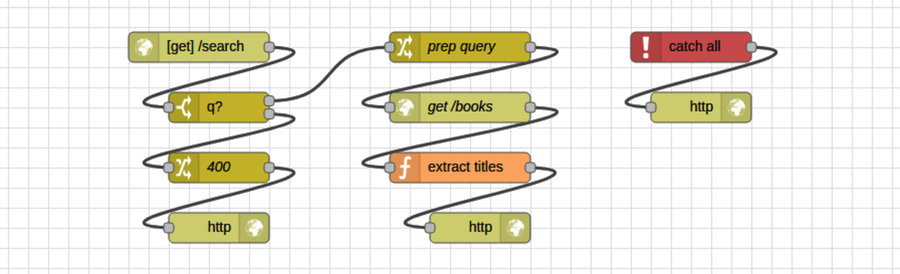

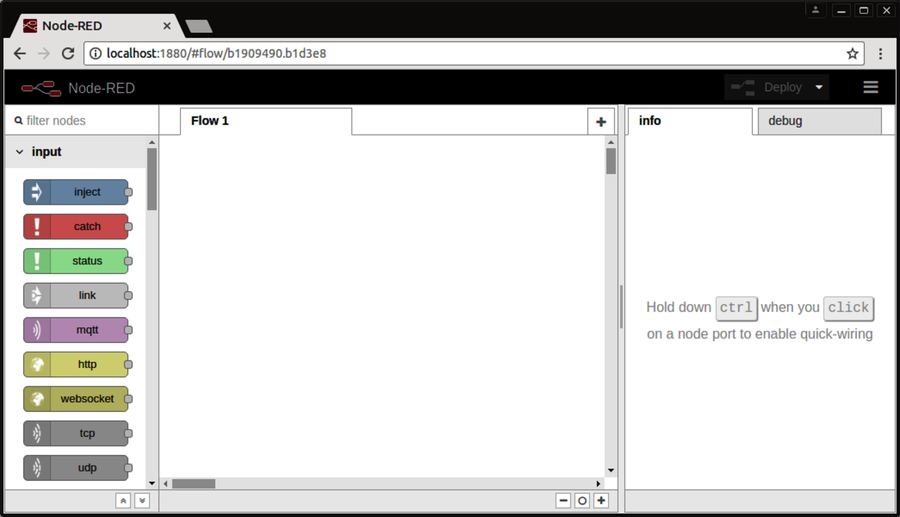

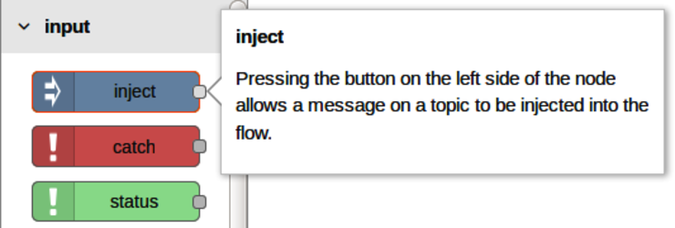

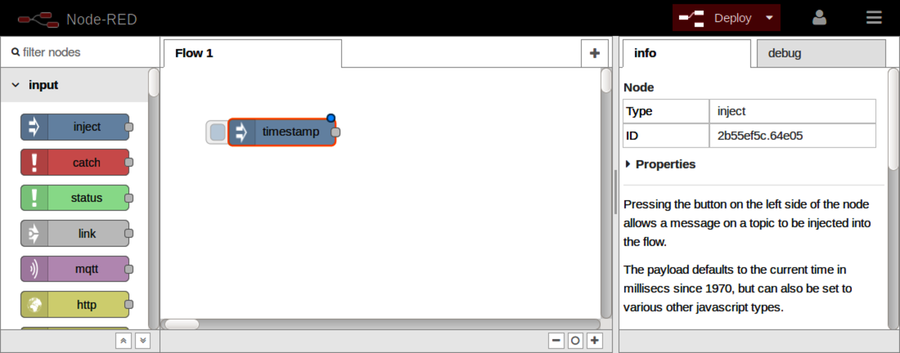

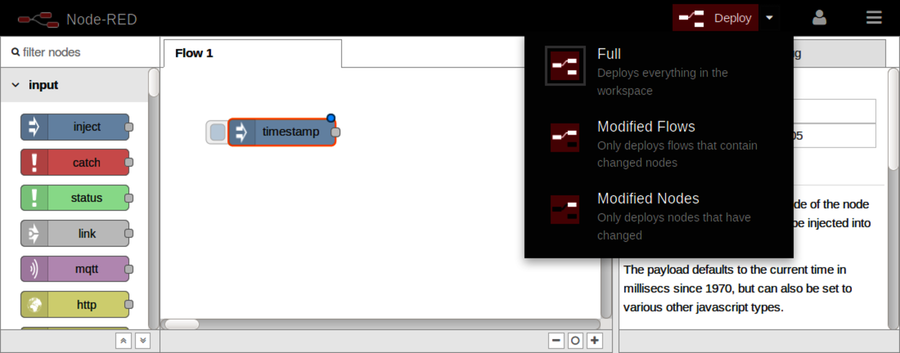

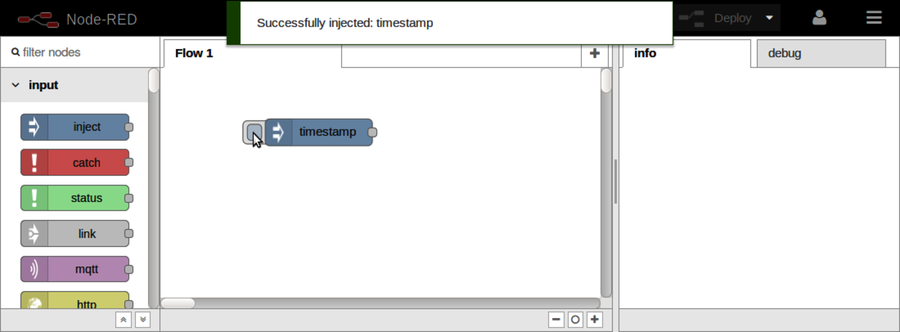

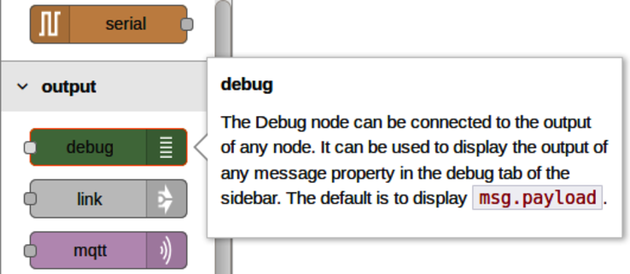

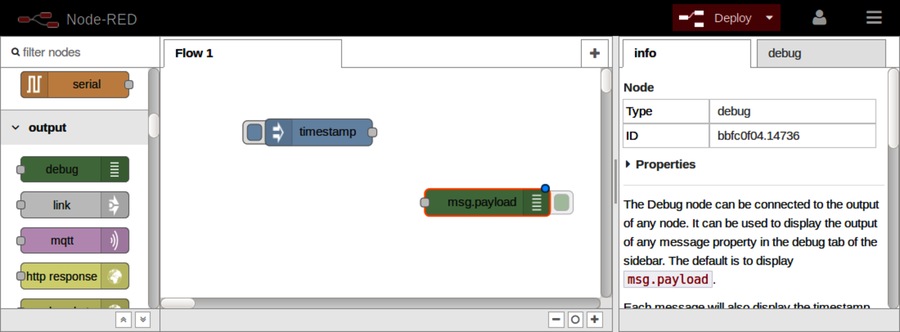

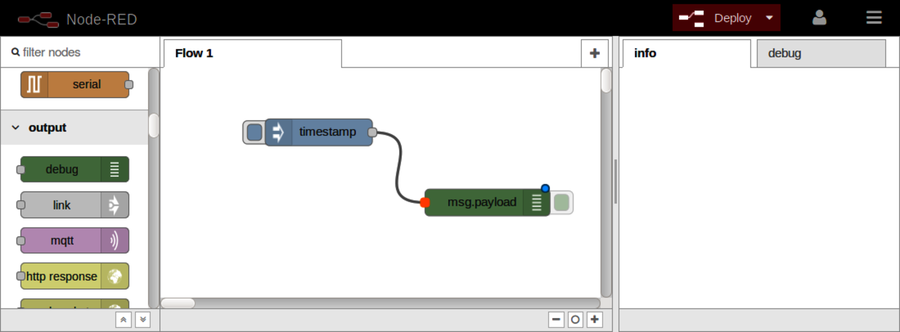

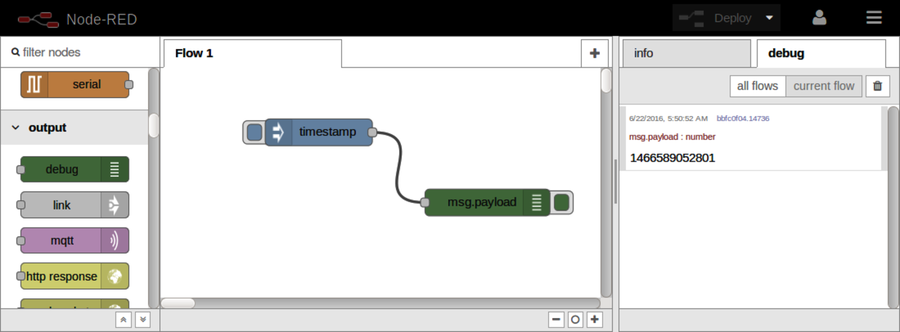

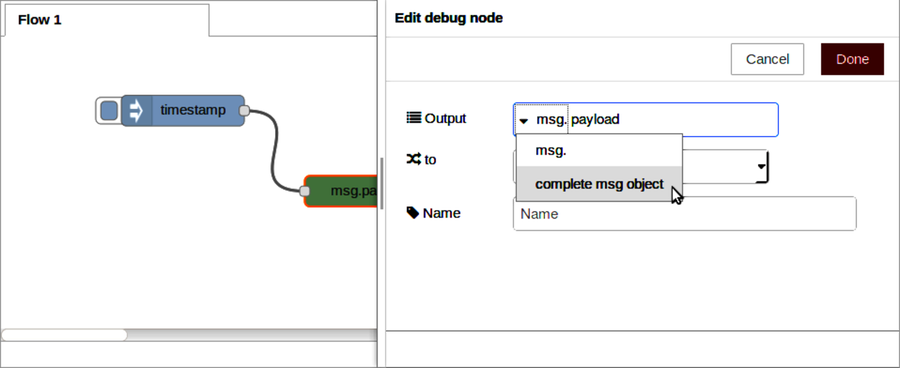

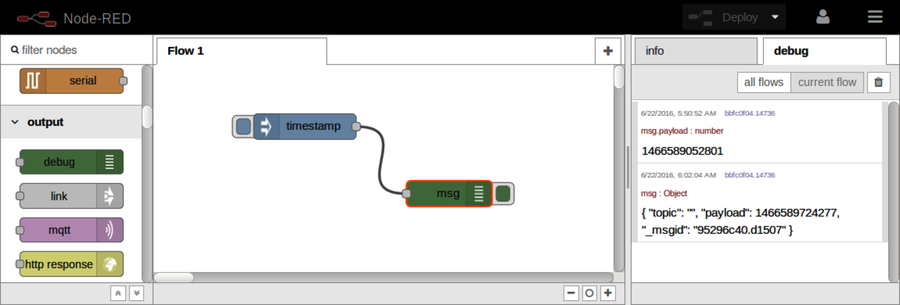

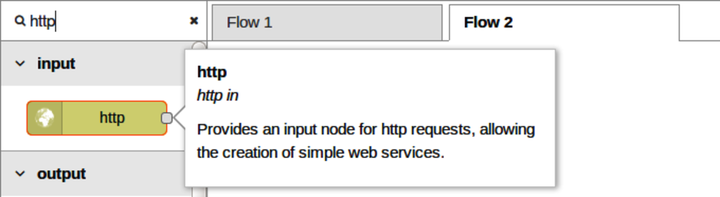

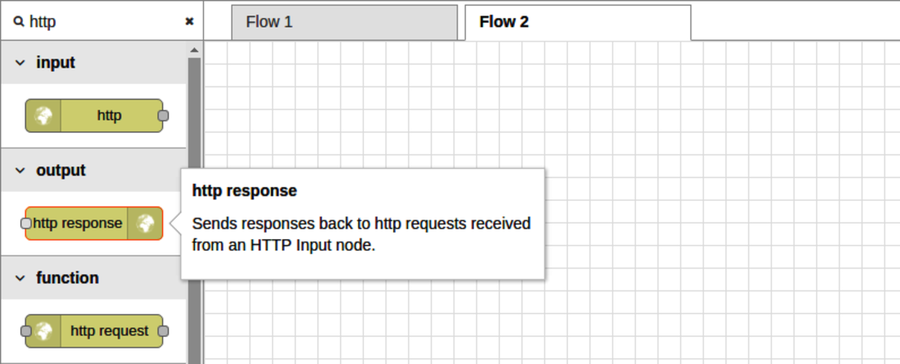

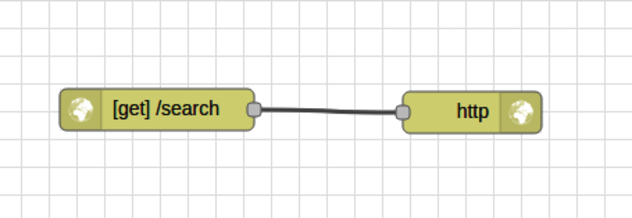

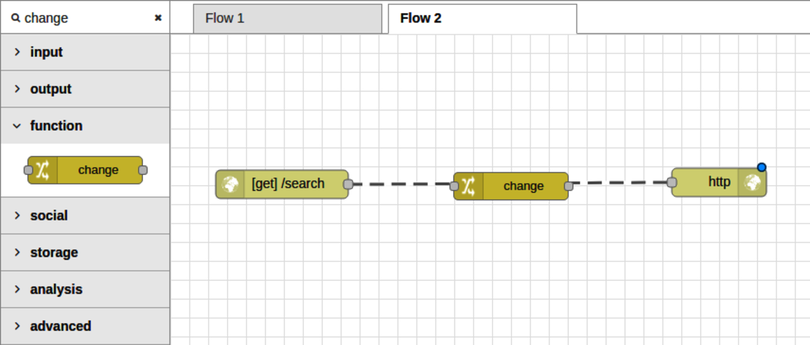

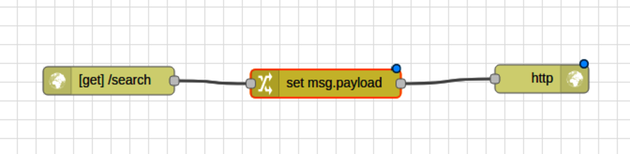

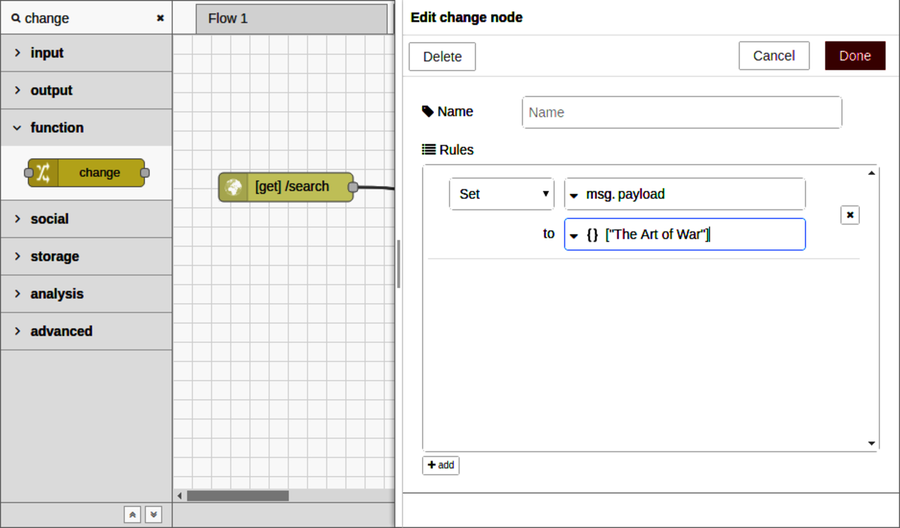

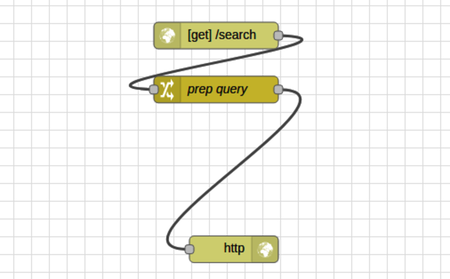

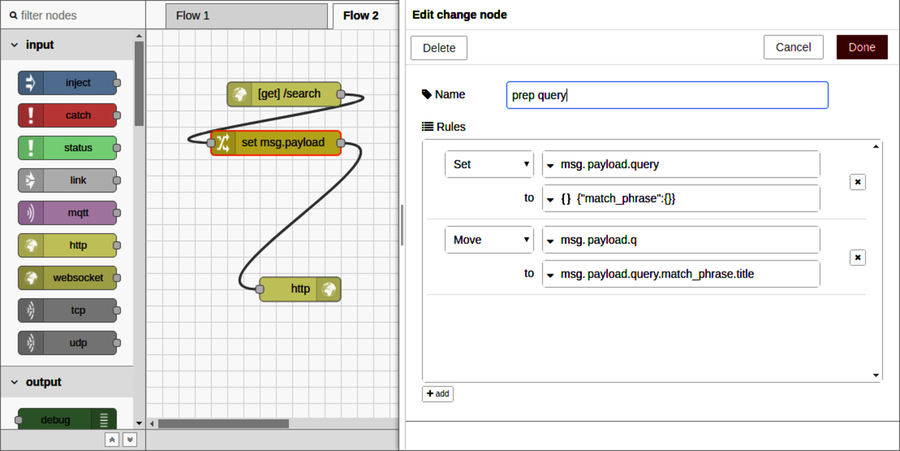

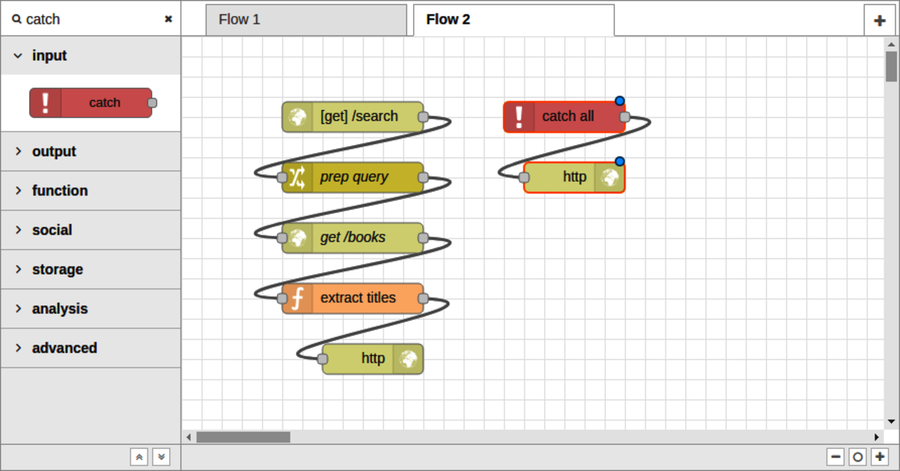

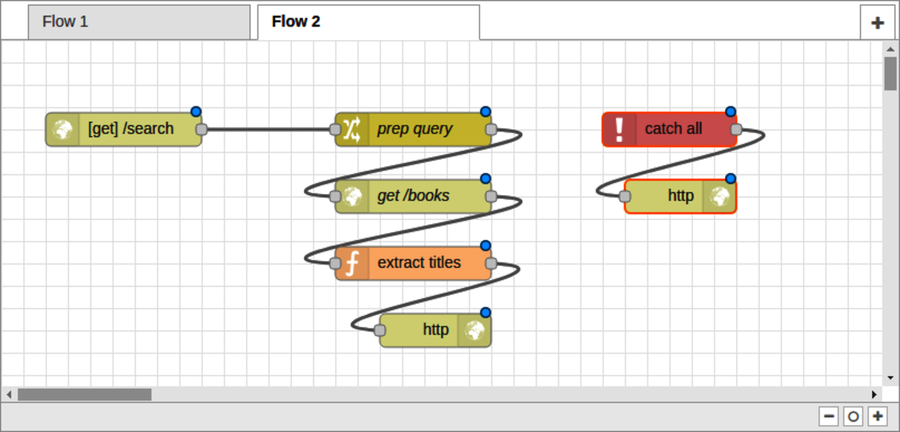

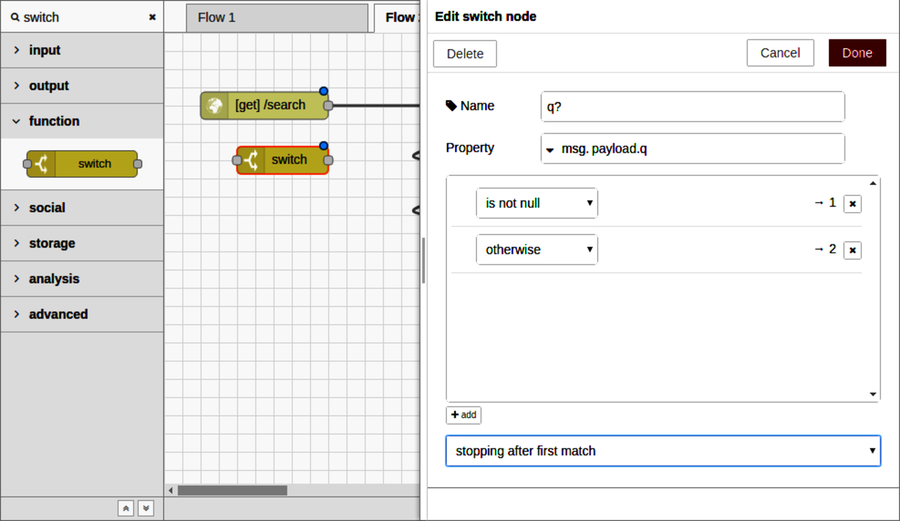

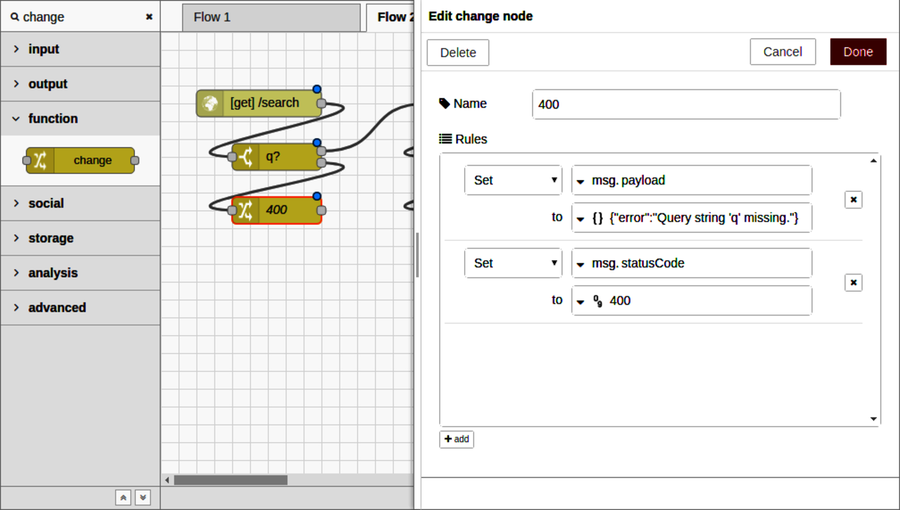

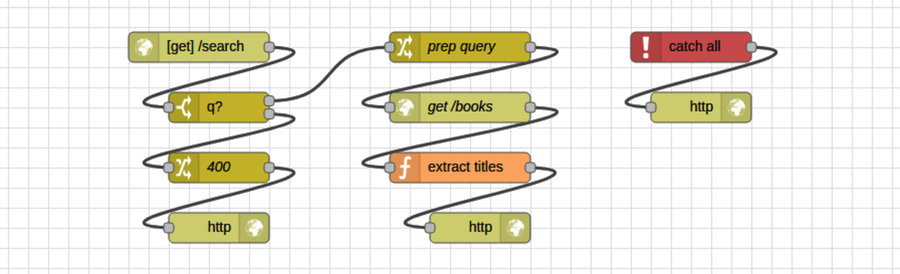

After Part III concludes, there’s a special bonus chapter on Node-RED. Chapter 10, BONUS: Developing Flows with Node-RED, walks you through this clever visual editor for designing event-based code flows. It ships directly with Raspbian, the default operating system of Raspberry Pi.

Using Node-RED, you can quickly stub out exploratory HTTP APIs. I’ll show you how!

In case you’re interested in using the front-end frameworks Angular and React, Appendix 1, Setting Up Angular, and Appendix 2, Setting Up React, show you how to integrate them with webpack and Express. The appendixes will help you put the pieces in place to start experimenting, but they don’t take the place of a good tutorial on how to fully develop with them.

Before you commit to reading this book, you should know what it doesn’t cover.

At the time of this writing, npm houses more than 528,000 modules, with a growth rate of more than 500 new modules per day.[1] Since the ecosystem and community around Node.js is so large and still growing so rapidly, this book does not attempt to cover everything. Instead, this short book teaches you the essentials you need to get out there and start coding.

In addition to the wealth of Node.js modules available, there’s the added complexity of working with non-Node.js services and platforms. Your Node.js code will invariably act as an intermediary between various systems and users both up and down the stack. To tell a cohesive story, we’ll naturally only be able to dive deep on a few of these, but always with an eye to the bigger picture.

If you’re looking for an opinionated book that focuses only on a particular stack like MEAN (Mongo, Express, Angular, and Node.js), this is not it! Rather than prescribe a particular stack, I’ll teach you the skills to put together the Node.js code, no matter which back end you connect to or front end you choose to put on top.

Instead of MongoDB, I’ve selected Elasticsearch to back the projects in this book because it’s increasingly popular among experienced Node.js developers, as evidenced by a 2016 survey by RisingStack.[2] Moreover, with its REST/JSON API, Elasticsearch offers a way to ease into HTTP services as a consumer before jumping into writing your own.

This book also shies away from front-end JavaScript frameworks. The two most popular front-end frameworks at the time of this writing are React, by Facebook,[3] and Angular, by Google.[4] This book covers neither of them in detail, by design. They both deserve more coverage than fits in these pages.

I want you to be the best Node.js coder you can be, whether you use any particular database or front-end framework.

The JavaScript language is probably the most misunderstood language today. Although this book does discuss language syntax from time to time (especially where it’s brand-new), this is not a beginner’s guide to JavaScript. As a quick quiz, you should be able to easily read and understand this code:

| | const list = []; |

| | for (let i = 1; i <= 100; i++) { |

| | if (!(i % 15)) { |

| | list.push('FizzBuzz'); |

| | } else if (!(i % 5)) { |

| | list.push('Buzz'); |

| | } else if (!(i % 3)) { |

| | list.push('Fizz'); |

| | } else { |

| | list.push(i); |

| | } |

| | } |

You may recognize this as a solution to the classic programming puzzle called FizzBuzz, made famous by Jeff Atwood in 2007.[5] Here’s another solution—one that makes gratuitous (and unnecessary) use of some of the newer JavaScript features.

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const list = [...Array(100).keys()] |

| | .map(n => n + 1) |

| | .map(n => n % 15 ? n : 'FizzBuzz') |

| | .map(n => isNaN(n) || n % 5 ? n : 'Buzz') |

| | .map(n => isNaN(n) || n % 3 ? n : 'Fizz'); |

If you don’t recognize the techniques used in this code, that’s expected! You’ll learn to use several of them, and many others, in this book.

The examples in this book assume you’re using a Unix-like operating system. We’ll make use of standard input and output streams, and pipe data between processes. The shell session examples have been tested with Bash, but other shells may work as well.

If you run Windows, I recommend setting up Cygwin.[6] This will give you the best shot at running the example code successfully, or you could run a Linux virtual machine.

The code examples in this book contain JavaScript, shell sessions, and a few HTML/XML excerpts. For the most part, code listings are provided in full—ready to be run at your leisure.

Samples and snippets are syntax-highlighted according to the rules of the language. Shell commands are prefixed by $.

When you write Node.js code, you should always handle errors and exceptions, even if you just rethrow them. You’ll learn how to do this throughout the book. However, some of the code examples lack error handling. This is to aid readability and save space, and sometimes to provide opportunities for reader tasks at the end of the chapter. In your code, you should always handle your errors.

The Pragmatic Bookshelf’s page for this book is a great resource.[7] You’ll find downloads for all the source code presented in this book, and feedback tools, including a community forum and an errata-submission form.

Thanks for choosing this book to show you Node.js the right way.

Node.js is a powerful platform for developing server-side JavaScript.

In this first part, you’ll write Node.js code, beginning with the familiar domain of the command line and then expanding into the realm of microservices. Along the way, you’ll learn to structure your code into modules, use third-party modules from npm, and take advantage of the latest ECMAScript language features.

An old programming adage says that while functionality is an asset, code is a liability.[8]

Throughout this book, as you learn to harness Node.js, keep in mind that the best line of code is the one you never had to write. If you can get something for free, take it!

However, the nature of a technical book is to teach you how to do something, even if somebody has already done it for you. By understanding how things work, you’ll be better able to build on top of them.

So we’ll be progressing in stages. In the beginning, you’ll be working at the lowest levels of Node.js—getting to know the environment, the language, and the fundamental APIs. As you master those, you’ll learn how to use other peoples’ modules, libraries, and services to replace some of that code and go to the next level.

By the end, you’ll see where it’s possible to make great gains using existing libraries, and where it makes sense to implement the functionality yourself. At the end of the day, this wisdom is the power that will distinguish you from a novice developer.

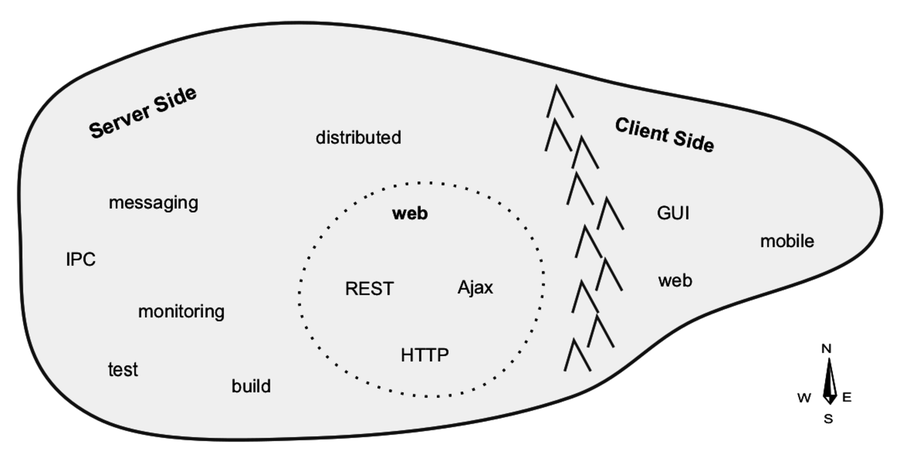

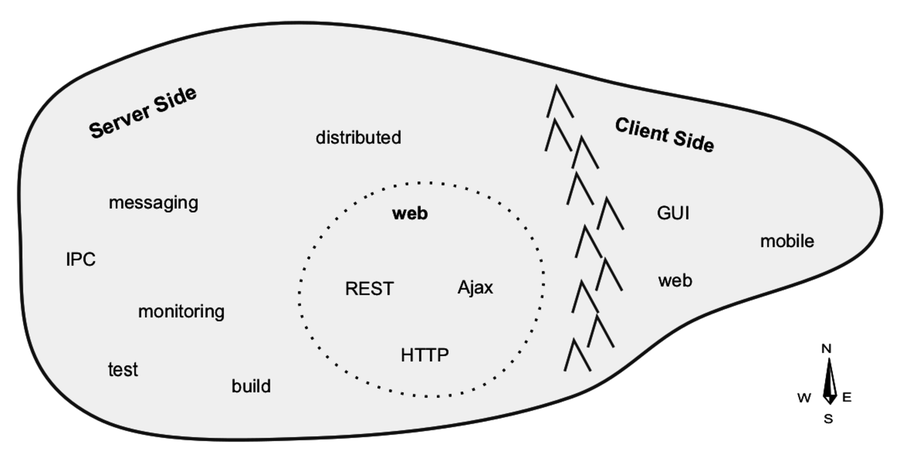

A lot of the buzz around Node.js is focused on the web. In truth, Node.js serves a bigger purpose that people often miss. Let’s use a map to see where Node.js fits in the broader scheme of things.

Imagine the set of all possible programs as the inhabitants of a vast sea. Programs that have similar purposes are near each other, and programs that differ are further apart. With that picture in mind, take a look at this map. It shows a close-up of one particular outcrop in this sea, the Island of I/O-Bound Programs.

I/O-bound programs are constrained by data access. These are programs where adding more processing power or RAM often makes little difference.

East of the mountain range, we find the client-side programs. These include GUI tools of all stripes, consumer applications, mobile apps, and web apps. Client-side programs interact directly with human beings, often by waiting patiently for their input.

West of the mountains are the server-side programs. This vast expanse is Node.js territory.

Deep within the server-side region lies the web—that old guard of HTTP, Ajax, and REST, communicating with JSON. The websites, apps, and APIs that consume so much of our collective mental energy live here.

Because we spend so much time thinking about the web, we often overemphasize Node.js’s use in developing web applications. People ask, “How is Node.js better for making web apps?” or “How can I make a REST service with Node.js?”

These are good questions, but they miss the point. Node.js is great for a wider range of things, and this book explores that larger area.

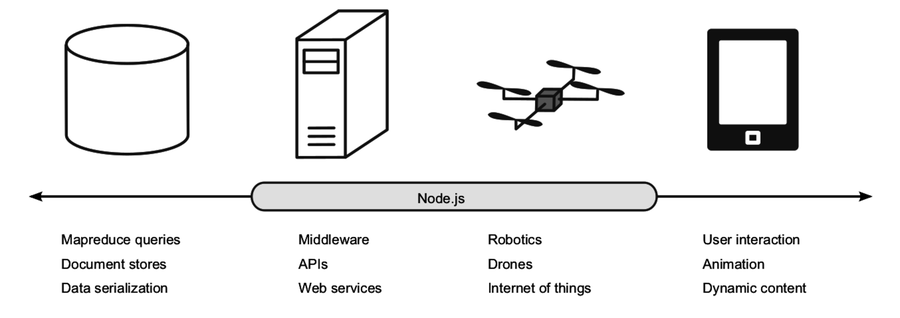

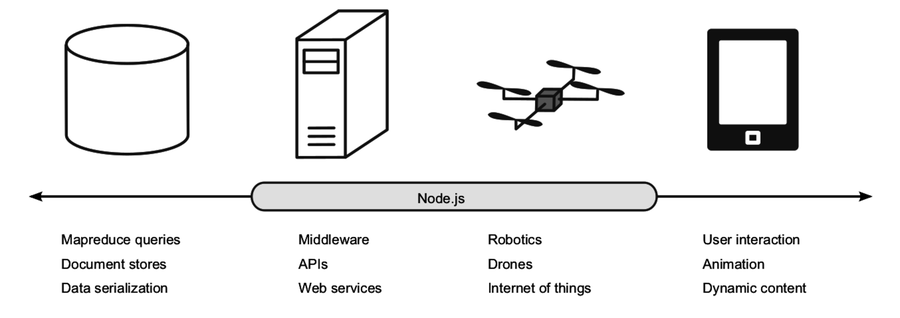

Since JavaScript first appeared in 1995, it has been solving problems all along the front-end/back-end spectrum. The following figure shows this spectrum and where Node.js fits within it.

In the web browser on the right, much of the scripting involves waiting for user interaction: click here, drag that, choose a file, etc. JavaScript has been extraordinarily successful in this space.

On the left, back-end databases are investing heavily in JavaScript. Document-oriented databases like MongoDB and CouchDB use JavaScript extensively—from modifying records to ad-hoc queries and mapreduce jobs. Other NoSQL datastores, like Elasticsearch and Neo4j, present data in JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). These days, you can even write SQL functions for Postgres in JavaScript with the right plugin.

Many middleware tasks are I/O-bound, just like client-side scripting and databases. These server-side programs often have to wait for things like a database result, feedback from a third-party web service, or incoming connection requests. Node.js is designed for exactly these kinds of applications.

Node.js has also made inroads into the field of autonomous systems. Platforms for protyping the Internet of Things, such as the Raspberry Pi OS Raspbian,[9] come with Node.js, and Tessel is built on Node.js from the ground up.[10] Johnny-Five and CylonJS are two robotics-development platforms that help you develop Node.js applications for a variety of hardware components.[11] [12]

Since robotics and Internet of Things applications tend to be very hardware-specific, developing them is not covered in this book. However, the skill of developing Node.js would transfer if you decide to go that route in the future.

Node.js couples JavaScript with an event loop for quickly dispatching operations when events occur. Many JavaScript environments use an event loop, but it is a core feature of Node.js.

Node.js’s philosophy is to give you low-level access to the event loop and to system resources. Or, in the words of core committer Felix Geisendörfer, in Node.js “everything runs in parallel except your code.”[13]

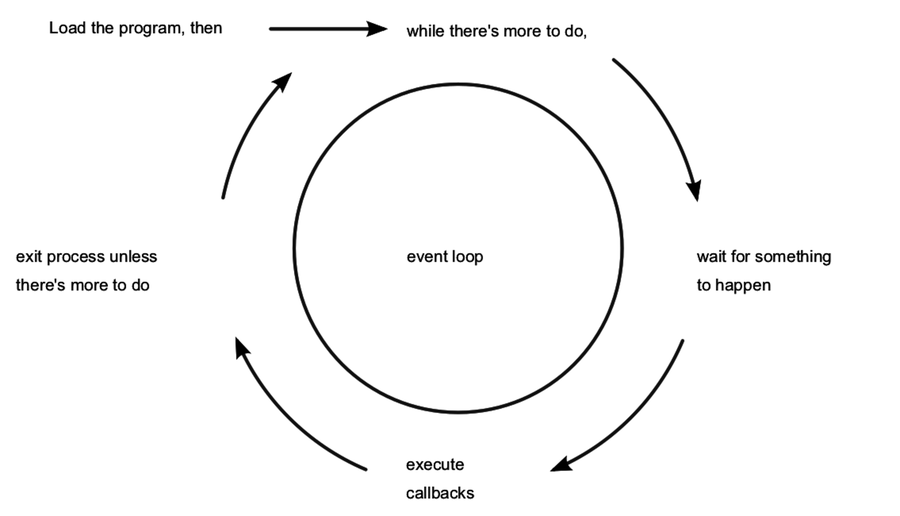

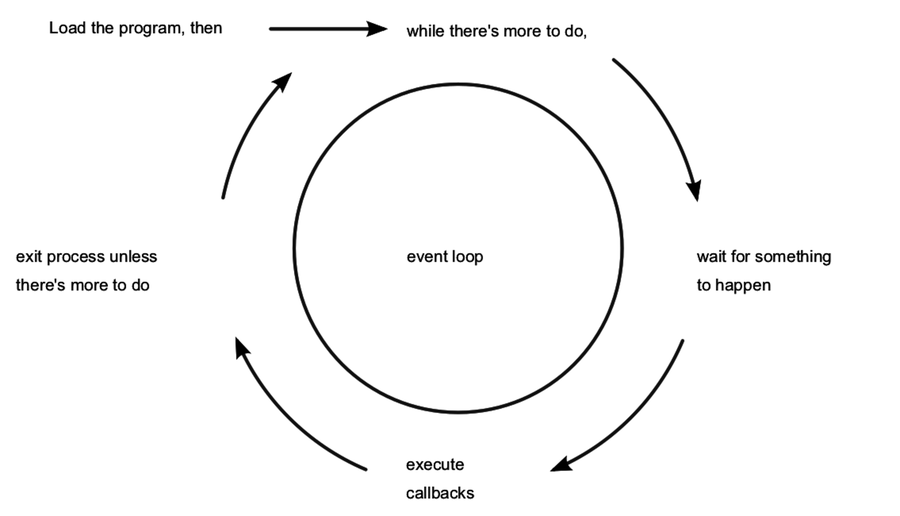

If this seems a little backward to you, don’t worry. The following figure shows how the event loop works.

As long as there’s something left to do, Node.js’s event loop will keep spinning. Whenever an event occurs, Node.js invokes any callbacks (event handlers) that are listening for that event.

As a Node.js developer, your job is to create the callback functions that get executed in response to events. Any number of callbacks can respond to any event, but only one callback function will ever be executing at any time.

Everything else your program might do—like waiting for data from a file or an incoming HTTP request—is handled by Node.js, in parallel, behind the scenes. Your application code will never be executed at the same time as anything else. It will always have the full attention of Node.js’s JavaScript engine while it’s running.

Other systems try to gain parallelism by running lots of code at the same time, typically by spawning many threads. But not Node.js. As far as your JavaScript code is concerned, Node.js is a single-threaded environment. At most, only one line of your code will ever be executing at any time.

Node.js gets away with this by doing most I/O tasks using nonblocking techniques. Rather than waiting line-by-line for an operation to finish, you create a callback function that will be invoked when the operation eventually succeeds or fails.

Your code should do what it needs to do, then quickly hand control back over to the event loop so Node.js can work on something else. We’ll develop practical examples of this throughout the book, starting in Chapter 2, Wrangling the File System.

If it seems strange to you that Node.js achieves parallelism by running only one piece of code at a time, that’s because it is. It’s an example of something I call a backwardism.

A backwardism is a concept that’s so bizarre that at first it seems completely backward. You’ve probably experienced many backwardisms while learning to program, whether you noticed them or not.

Take the concept of a variable. In algebra it’s common to see equations like 7x + 3 = 24. Here, x is called a variable; it has exactly one value, and your job is to solve the equation to figure out what that value is.

Then when you start learning how to program, you quickly run into statements like x = x + 7. Now x is still called a variable, but it can have any value that you assign to it. It can even have different values at different times!

From algebra’s perspective, this is a backwardism. The equation x = x + 7 makes no sense at all. The notion of a variable in programming is not just a little different than in algebra—it’s 100 percent backward. But once you understand the concept of assignment, the programming variable makes perfect sense.

So it is with Node.js’s single-threaded event loop. From a multithreaded perspective, running just one piece of code at a time seems silly. But once you understand event-driven programming—with nonblocking APIs—it becomes clear.

Programming is chock-full of backwardisms like these, and Node.js is no exception. Starting out, you’ll frequently run into code that looks like it should work one way, but it actually does something quite different.

That’s OK! With this book, you’ll learn Node.js by making compact programs that interact in useful ways. As we run into more of Node.js’s backwardisms, we’ll dive in and explore them.

Node.js is a surprisingly big subject, so let’s break it down into different aspects. We might talk about many aspects of Node.js development, ranging from basic JavaScript syntax to revision control. This book focuses on five in particular:

Let’s explore each of these briefly.

Practical programming is all about producing real code that does something useful. Interacting with a filesystem, establishing socket connections, and serving web applications are all examples of practical programming.

Each remaining chapter of this book focuses on one particular practical domain. Through code examples specific to each domain, you’ll learn Node.js’s architecture, patterns, JavaScriptisms, and supporting code.

Understanding Node.js’s core modules and behavior will help you to harness its features while avoiding pitfalls. For example, Node.js uses an event loop written in C for scheduling work. But it executes application code in a JavaScript environment. How information is shuttled between these layers is the kind of impactful architectural detail you’ll learn.

Like any successful codebase with a healthy ecosystem, Node.js has a number of repeating patterns. Some of these patterns are baked into the core while others mostly appear in third-party libraries. Examples include the use of callbacks, error-handling techniques, and classes like EventEmitter and Stream, which are used liberally for event dispatching.

As we progress through different practical programming domains, we’ll naturally encounter these and other patterns. When we do, you’ll discover why they’re useful and how to use them effectively.

JavaScript is the language of Node.js programs, so you’ll be seeing quite a lot of it. The code examples in this book make use of the latest available JavaScript features that Node.js supports. Some of these features may be unfamiliar to you, even if you’ve done JavaScript development before.

Modern JavaScriptisms discussed in this book include things like arrow functions, spread parameters, and destructuring assignment.

Code does not live in isolation; it takes a village to support any individual program. Supporting code covers lots of things, from unit testing to deployment scripts. We’ll use supporting code throughout the book to make our programs more robust, more scalable, and more manageable.

With these five aspects, you’ll be able to develop applications that make the most use of the platform while employing idiomatic Node.js style. The example applications you’ll develop in this book are functional and small, and aim to clearly demonstrate these concepts. But to use them, you’ll need to get Node.js installed first.

To install Node.js, you have several choices based on your operating system and your comfort with building from source code.

This book assumes you are using the latest stable version of Node.js 8. If you install a different version—for example, by building from the latest source code—the code examples in this book may not work. From the command line you can run node --version to see what version you have installed if you are not sure:

| | $ node --version |

| | v8.0.0 |

One of the easiest ways to get Node.js is to download an installer from nodejs.org.[14]

Another popular option (the one that I use personally) is Node.js Version Manager (nvm).[15] If you’re using a Unix-like OS (such as Mac OS X or Linux), you can install nvm like so:

| | $ curl https://raw.github.com/creationix/nvm/master/install.sh | sh |

Then install a specific version:

| | $ nvm install v8.0.0 |

If you have trouble, you can get help on the Node.js mailing lists and IRC channel, both linked from the Node.js community page.[16]

We’ve got a lot of ground to cover, and we don’t have many pages to do it. So if you’re ready, let’s begin in the oh-so-familiar domain of filesystem access.

As a programmer, chances are you’ve had to access a filesystem at some point: reading, writing, renaming, and deleting files. We’ll start our Node.js journey in this familiar area, creating useful, asynchronous file utilities. Along the way we’ll explore the following aspects of Node.js development:

On the architecture front, you’ll see how the event loop shapes a program’s flow. We’ll use Buffers for transporting data between Node.js’s JavaScript engine and its native core, and we’ll use Node.js’s module system to bring in core libraries.

Inside our programs, we’ll use common Node.js patterns like callbacks for handling asynchronous events. We’ll harness Node.js’s EventEmitter and Stream classes to pipe data around.

We’ll take a look at some JavaScript features and best practices such as block scoping and arrow-function expressions.

You’ll learn how to spawn and interact with child processes, capture their output, and detect state changes.

We’ll begin by creating a tool that watches a file for changes. This’ll give you a peek into how the event loop works while introducing Node.js’s filesystem APIs.

Let’s get started by developing a couple of simple programs that watch files for changes and read arguments from the command line. Even though they’re short, these applications offer insights into Node.js’s event-based architecture.

Watching files for changes is a convenient problem to start with because it demands asynchronous coding while demonstrating important Node.js concepts. Taking action whenever a file changes is just plain useful in a number of cases, ranging from automated deployments to running unit tests.

Open a terminal to begin. Create a new directory called filesystem and navigate down into it.

| | $ mkdir filesystem |

| | $ cd filesystem |

You’ll use this directory for all of the code examples in this chapter. Once there, use the touch command to create a file called target.txt.

| | $ touch target.txt |

If you’re in an environment that doesn’t have the touch command (like Windows), you can alternatively echo something to write the file.

| | $ echo, > target.txt |

This file will be the target for our watcher program. Now open your favorite text editor and enter the following:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | fs.watch('target.txt', () => console.log('File changed!')); |

| | console.log('Now watching target.txt for changes...'); |

Save this file as watcher.js in the filesystem directory alongside the target.txt file. Although this is a short program, it deserves scrutiny since it takes advantage of a number of JavaScript and Node.js features. Let’s step through it.

The program begins with the string ’use strict’ at the top. This causes the program to be executed in strict mode, a feature introduced in ECMAScript version 5. Strict mode disables certain problematic JavaScript language features and makes others throw exceptions. It’s always a good idea to use strict mode, and we’ll use it throughout the book.

Next, notice the const keyword; this sets up fs to be a local variable with a constant value. A variable declared with const must be assigned a value when declared, and can never have anything assigned to it again (which would cause a runtime error).

It might surprise you, but it turns out that most of the time, in most code, variables don’t need to be reassigned, making const a good default choice for declaring variables. The alternative to const is let, which we’ll discuss shortly.

The require() function pulls in a Node.js module and returns it. In our case, we’re calling require(’fs’) to incorporate Node.js’s built-in filesystem module.[17]

In Node.js, a module is a self-contained bit of JavaScript that provides functionality to be used elsewhere. The output of require() is usually a plain old JavaScript object, but may also be a function. Modules can depend on other modules, much like libraries in other programming environments, which import or #include other libraries.

Next we call the fs module’s watch() method, which takes a path to a file and a callback function to invoke whenever the file changes. In JavaScript, functions are first-class citizens. This means they can be assigned to variables and passed as parameters to other functions. Take a close look at our callback function:

| | () => console.log('File changed!') |

This is an arrow-function expression, sometimes called a fat arrow function or just an arrow function. The empty pair of parentheses () at the beginning means this function expects no arguments. Then the body of the function uses console.log to echo a message to standard output.

Arrow functions are new in ECMAScript 2015 and you’ll be writing many such functions throughout this book. Prior to the introduction of arrow functions, you’d have supplied a callback using the more verbose function(){} construction:

| | function() { |

| | console.log('File changed!'); |

| | } |

Aside from having a terser syntax than older function expressions, arrow functions have another big advantage over their ancestral counterparts: they do not create a new scope for this. Dealing with this has been a thorn in the side of many JavaScript developers over the years, but thanks to arrow functions, it’s no longer a major source of consternation. Just like const should be your go-to means of declaring variables, arrow functions should be your first choice in declaring function expressions (such as callbacks).

The last line of the program just informs you that everything is ready. Let’s try it out! Return to the command line and launch the watcher program using node, like so:

| | $ node watcher.js |

| | Now watching target.txt for changes... |

After the program starts, Node.js will patiently wait until the target file is changed. To trigger a change, open another terminal to the same directory and touch the file again. The terminal running watcher.js will output the string File changed!, and then the program will go back to waiting.

If you see duplicate messages, particularly on Mac OS X or Windows, this is not a bug in your code! There are a number of known issues around this, and many have to do with how the operating system surfaces changes.

Since you’ll be touching the target file a lot this chapter to trigger changes, you might want to use the watch command to do this automatically:

| | $ watch -n 1 touch target.txt |

This command will touch the target file once every second until you stop it. If you’re on a system that doesn’t have the watch command, don’t worry. Any means of writing to target.txt is fine.

The program we wrote in the last section is a good example of the Node.js event loop at work. Recall the event-loop figure from How Node.js Applications Work. Our simple file-watcher program causes Node.js to go through each of these steps, one by one.

To run the program, Node.js does the following:

It loads the script, running all the way through to the last line, which produces the Now watching message in the console.

It sees that there’s more to do because of the call to fs.watch.

It waits for something to happen—namely, for the fs module to observe a change to the file.

It executes our callback function when the change is detected.

It determines that the program still has not finished, and resumes waiting.

In Node.js the event loop spins until there’s nothing left to do, there’s nothing left to wait for, or the program exits by some other means. For example, if an exception is thrown and not caught, the process will exit. We’ll look at how this works next.

Now let’s make our program more useful by taking in the file to watch as a command-line argument. This will introduce the process global object and how Node.js deals with exceptions.

Open your editor and enter this:

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | const filename = process.argv[2]; |

| | if (!filename) { |

| | throw Error('A file to watch must be specified!'); |

| | } |

| | fs.watch(filename, () => console.log(`File ${filename} changed!`)); |

| | console.log(`Now watching ${filename} for changes...`); |

Save the file as watcher-argv.js and run it like so:

| | $ node watcher-argv.js target.txt |

| | Now watching target.txt for changes... |

You should see output and behavior that’s nearly identical to that of the first watcher.js program. After outputting Now watching target.txt for changes... the script will diligently wait for changes to the target file.

This program uses process.argv to access the incoming command-line arguments. argv stands for argument vector; it’s an array containing node and the full path to the watcher-argv.js as its first two elements. The third element (that is, at index 2) is target.txt, the name of our target file.

Note the use of backtick characters (‘) to mark the strings logged in this program:

| | `File ${filename} changed!` |

These are called template strings. They can span multiple lines and they support expression interpolation, meaning you can place an expression inside of ${} and it will insert the stringified result.

If a target filename is not provided to watcher-argv.js, the program will throw an exception. You see try that by simply omitting the target.txt parameter:

| | $ node watcher-argv.js |

| | /full/path/to/script/watcher-argv.js:4 |

| | throw Error('A file to watch must be specified!'); |

| | ^ |

| | |

| | Error: A file to watch must be specified! |

Any unhandled exception thrown in Node.js will halt the process. The exception output shows the offending file and the line number and position of the exception.

Processes are important in Node. It’s pretty common in Node.js development to spawn separate processes as a way of breaking up work, rather than putting everything into one big Node.js program. In the next section, you’ll learn how to spawn a process in Node.

Let’s enhance our file-watching example program even further by having it spawn a child process in response to a change. To do this, we’ll bring in Node.js’s child-process module and dive into some Node.js patterns and classes. You’ll also learn how to use streams to pipe data around.

To keep things simple, we’ll make our script invoke the ls command with the -l and -h options. This will give us some information about the target file whenever it changes. You can use the same technique to spawn other kinds of processes, as well.

Open your editor and enter this:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | const spawn = require('child_process').spawn; |

| | const filename = process.argv[2]; |

| | |

| | if (!filename) { |

| | throw Error('A file to watch must be specified!'); |

| | } |

| | |

| | fs.watch(filename, () => { |

| | const ls = spawn('ls', ['-l', '-h', filename]); |

| | ls.stdout.pipe(process.stdout); |

| | }); |

| | console.log(`Now watching ${filename} for changes...`); |

Save the file as watcher-spawn.js and run it with node as before:

| | $ node watcher-spawn.js target.txt |

| | Now watching target.txt for changes... |

If you go to a different console and touch the target file, your Node.js program will produce something like this:

| | -rw-rw-r-- 1 jimbo jimbo 6 Dec 8 05:19 target.txt |

The username, group, and other properties of the file will be different, but the format should be the same.

Notice that we added a new require() at the beginning of the program. Calling require(’child_process’) returns the child process module.[18] We’re interested only in the spawn() method, so we save that to a constant with the same name and ignore the rest of the module.

| | spawn = require('child_process').spawn, |

Remember, functions are first-class citizens in JavaScript, so we’re free to assign them directly to variables like we did here.

Next, take a look at the callback function we passed to fs.watch():

| | () => { |

| | const ls = spawn('ls', ['-l', '-h', filename]); |

| | ls.stdout.pipe(process.stdout); |

| | } |

Unlike the previous arrow-function expression, this one has a multiline body; hence the opening and closing curly braces ({}).

The first parameter to spawn() is the name of the program we wish to execute; in our case it’s ls. The second parameter is an array of command-line arguments. It contains the flags and the target filename.

The object returned by spawn() is a ChildProcess. Its stdin, stdout, and stderr properties are Streams that can be used to read or write data. We want to send the standard output from the child process directly to our own standard output stream. This is what the pipe() method does.

Sometimes you’ll want to capture data from a stream, rather than just piping it forward. Let’s see how to do that.

EventEmitter is a very important class in Node.js. It provides a channel for events to be dispatched and listeners to be notified. Many objects you’ll encounter in Node.js inherit from EventEmitter, like the Streams we saw in the last section.

Now let’s modify our previous program to capture the child process’s output by listening for events on the stream. Open an editor to the watcher-spawn.js file from the previous section, then find the call to fs.watch(). Replace it with this:

| | fs.watch(filename, () => { |

| | const ls = spawn('ls', ['-l', '-h', filename]); |

| | let output = ''; |

| | |

| | ls.stdout.on('data', chunk => output += chunk); |

| | |

| | ls.on('close', () => { |

| | const parts = output.split(/\s+/); |

| | console.log([parts[0], parts[4], parts[8]]); |

| | }); |

| | }); |

Save this updated file as watcher-spawn-parse.js. Run it as usual, then touch the target file in a separate terminal. You should see output something like this:

| | $ node watcher-spawn-parse.js target.txt |

| | Now watching target.txt for changes... |

| | [ '-rw-rw-r--', '0', 'target.txt' ] |

The new callback starts out the same as before, creating a child process and assigning it to a variable called ls. It also creates an output variable, which will buffer the output coming from the child process.

Notice the output variable declared with the keyword let. Like const, let declares a variable, but one that could be assigned a value more than once. Generally speaking, you should use const to declare your variables unless you know that the value should be able to change at runtime.

Next we add event listeners. An event listener is a callback function that is invoked when an event of a specified type is dispatched. Since the Stream class inherits from EventEmitter, we can listen for events from the child process’s standard output stream:

| | ls.stdout.on('data', chunk => output += chunk); |

A lot is going on in this single line of code, so let’s break it down.

Notice that the arrow function takes a parameter called chunk. When an arrow function takes exactly one parameter, like this one, you can omit the parentheses around the param.

The on() method adds a listener for the specified event type. We listen for data events because we’re interested in data coming out of the stream.

Events can send along extra information, which arrives in the form of parameters to the callbacks. data events in particular pass along a Buffer object. Each time we get a chunk of data, we append it to our output.

A Buffer is Node.js’s way of representing binary data.[19] It points to a blob of memory allocated by Node.js’s native core, outside of the JavaScript engine. Buffers can’t be resized and they require encoding and decoding to convert to and from JavaScript strings.

Any time you add a non-string to a string in JavaScript (like we’re doing here with chunk), the runtime will implicitly call the object’s toString() method. For a Buffer, this means copying the content into Node.js’s heap using the default encoding (UTF-8).

Shuttling data in this way can be a slow operation, relatively speaking. If you can, it’s often better to work with Buffers directly, but strings are more convenient. For this tiny amount of data the impact of conversion is small, but it’s something to keep in mind as you work more with Buffers.

Like Stream, the ChildProcess class extends EventEmitter, so we can add listeners to it, as well.

| | ls.on('close', () => { |

| | const parts = output.split(/\s+/); |

| | console.log([parts[0], parts[4], parts[8]]); |

| | }); |

After a child process has exited and all its streams have been flushed, it emits a close event. When the callback printed here is invoked, we parse the output data by splitting on sequences of one or more whitespace characters (using the regular expression /\s+/). Finally, we use console.log to report on the first, fifth, and ninth fields (indexes 0, 4, and 8), which correspond to the permissions, size, and filename, respectively.

We’ve seen a lot of Node.js’s features in this small problem space of file-watching. You now know how to use key Node.js classes, including EventEmitter, Stream, ChildProcess, and Buffer. You also have firsthand experience writing asynchronous callback functions and coding for the event loop.

Let’s expand on these concepts in the next phase of our filesystem journey: reading and writing files.

Earlier in this chapter, we wrote a series of Node.js programs that could watch files for changes. Now let’s explore Node.js’s methods for reading and writing files. Along the way we’ll see two common error-handling patterns in Node.js: error events on EventEmitters and err callback arguments.

There are a few approaches to reading and writing files in Node. The simplest is to read in or write out the entire file at once. This technique works well for small files. Other approaches read and write by creating Streams or staging content in a Buffer. Here’s an example of the whole-file-at-once approach:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | fs.readFile('target.txt', (err, data) => { |

| | if (err) { |

| | throw err; |

| | } |

| | console.log(data.toString()); |

| | }); |

Save this file as read-simple.js and run it with node:

| | $ node read-simple.js |

You’ll see the contents of target.txt echoed to the command line. If the file is empty, all you’ll see is a blank line.

Notice how the first parameter to the readFile() callback handler is err. If readFile is successful, then err will be null. Otherwise the err parameter will contain an Error object. This is a common error-reporting pattern in Node.js, especially for built-in modules. In our example’s case, we throw the error if there was one. Recall that an uncaught exception in Node.js will halt the program by escaping the event loop.

The second parameter to our callback, data, is a Buffer—the same kind that was passed to our various callbacks in previous sections.

Writing a file using the whole-file approach is similar. Here’s an example:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | fs.writeFile('target.txt', 'hello world', (err) => { |

| | if (err) { |

| | throw err; |

| | } |

| | console.log('File saved!'); |

| | }); |

This program writes hello world to target.txt (creating it if it doesn’t exist, or overwriting it if it does). If for any reason the file can’t be written, then the err parameter will contain an Error object.

You create a read stream or a write stream by using fs.createReadStream() and fs.createWriteStream(), respectively. For example, here’s a very short program called cat.js. It uses a file stream to pipe a file’s data to standard output:

| | #!/usr/bin/env node |

| | 'use strict'; |

| | require('fs').createReadStream(process.argv[2]).pipe(process.stdout); |

Because the first line starts with #!, you can execute this program directly in Unix-like systems. You don’t need to pass it into the node program (although you still can).

Use chmod to make it executable:

| | $ chmod +x cat.js |

Then, to run it, send the name of the chosen file as an additional argument:

| | $ ./cat.js target.txt |

| | hello world |

The code in cat.js does not bother assigning the fs module to a variable. The require() function returns a module object, so we can call methods on it directly.

You can also listen for data events from the file stream instead of calling pipe(). The following program called read-stream.js does this:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | require('fs').createReadStream(process.argv[2]) |

| | .on('data', chunk => process.stdout.write(chunk)) |

| | .on('error', err => process.stderr.write(`ERROR: ${err.message}\n`)); |

Here we use process.stdout.write() to echo data, rather than console.log. The incoming data chunks already contain any newline characters from the input file. We don’t need the extra newline that console.log would add.

Conveniently, the return value of on() is the same emitter object. We take advantage of this fact to chain our handlers, setting up one right after the other.

When working with an EventEmitter, the way to handle errors is to listen for error events. Let’s trigger an error to see what happens. Run the program, but specify a file that doesn’t exist:

| | $ node read-stream.js no-such-file |

| | ERROR: ENOENT: no such file or directory, open 'no-such-file' |

Since we’re listening for error events, Node.js invokes our handler (and then proceeds to exit normally). If you don’t listen for error events, but one happens anyway, Node.js will throw an exception. And as we saw before, an uncaught exception will cause the process to terminate.

The file-access methods we’ve discussed in this chapter so far are asynchronous. They perform their I/O duties—waiting as necessary—completely in the background, only to invoke callbacks later. This is by far the preferred way to do I/O in Node.

Even so, many of the methods in the fs module have synchronous versions, as well. These end in *Sync, like readFileSync, for example. Doing synchronous file access might look familiar to you if you haven’t done a lot of async development in the past. However, it comes at a substantial cost.

When you use the *Sync methods, the Node.js process will block until the I/O finishes. This means Node.js won’t execute any other code, won’t trigger any callbacks, won’t process any events, won’t accept any connections—nothing. It’ll just sit there indefinitely waiting for the operation to complete.

However, synchronous methods are simpler to use since they lack the callback step. They either return successfully or throw an exception, without the need for a callback function. There actually are cases where this style of access is OK; we’ll discuss them in the next section.

Here’s an example of how to read a file using the readFileSync() method:

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | const data = fs.readFileSync('target.txt'); |

| | process.stdout.write(data.toString()); |

The return value of readFileSync() is a Buffer—the same as the parameter passed to callbacks of the asynchronous readFile() method we saw before.

Node.js’s fs module has many other methods that map nicely onto POSIX conventions. (POSIX is a family of standards for interoperability between operating systems—including filesystem utilities.)[20] To name a few examples, you can copy() files and unlink() (delete) them. You can use chmod() to change permissions and mkdir() to create directories.

These functions rely on the same kinds of callback parameters we’ve used in this chapter. They’re all asynchronous by default, but many come with equivalent *Sync versions.

Given the cost that blocking has on the Node.js event loop, you might think it’s always bad to use synchronous file-access methods. To understand when it’s OK, you can think of Node.js programs as having two phases.

In the initialization phase, the program is getting set up, bringing in libraries, reading configuration parameters, and doing other mission-critical tasks. If something goes wrong at this early stage, not much can be done, and it’s best to fail fast. The only time you should consider synchronous file access is during the initialization phase of your program.

The second phase is the operation phase, when the program churns through the event loop. Since many Node.js programs are networked, this means accepting connections, making requests, and waiting on other kinds of I/O. You should never use synchronous file-access methods during this phase.

The require() function is an example of this principle in action—it synchronously evaluates the target module’s code and returns the module object. Either the module will successfully load or the program will fail right away.

As a rule of thumb, if your program couldn’t possibly succeed without the file, then it’s OK to use synchronous file access. If your program could conceivably continue about its business, then it’s better to take the safe route and stick to asynchronous I/O.

In this chapter we’ve used Node.js to perform file operations in Node.js’s evented, asynchronous, callback-oriented way. You learned how to watch files for changes and to read and write files. You also learned how to spawn child processes and access command-line arguments.

Along the way, we covered the EventEmitter class. We used the on() method to listen for events and handle them in our callback functions. And we used Streams—which are a special kind of EventEmitter—to process data in buffered chunks or pipe it directly to other streams.

Oh, and let’s not forget about errors. You learned Node.js’s convention of passing an err argument to callbacks, and how error events can be captured from an EventEmitter.

Keep these patterns in mind as you continue through the book. Third-party libraries sometimes have different styles, but the concepts you’ve learned here reappear throughout the Node.js ecosystem.

In the next chapter we’ll dig into the other form of server-side I/O: network connections. We’ll explore the domain of networked services, building on the concepts and practices developed here.

The following are some bonus questions for you to try out your newly gained Node.js knowledge.

The various example programs we developed in this chapter lack many safety checks. Consider the following questions, and how you’d change the code to address them:

In an early example of our file-watcher program, we pulled the filename to watch from process.argv. Consider these questions:

Node.js was designed from the ground up to do networked programming. In this chapter, we’ll explore Node.js’s built-in support for low-level socket connections. TCP sockets form the backbone of modern networked applications, and understanding them will serve you well as we do more complex networking through the rest of the book.

As you develop socket-based servers and clients, you’ll learn about the following Node.js aspects.

The asynchronous programming techniques we explored in the last chapter will be even more important here. You’ll learn how to extend Node.js classes such as EventEmitter. You’ll create custom modules to house reusable code.

A network connection has two endpoints. A common pattern is for one endpoint to act as the server while the other is the client. We’ll develop both kinds of endpoints in this chapter, as well as a JSON-based protocol for client/server communication.

The JavaScript language has an interesting inheritance model. You’ll learn about Node.js’s utilities for creating class hierarchies.

Testing is important to ensure that our programs behave the way we expect them to. In this chapter, we’ll develop a unit test with a framework called Mocha, which we’ll install with npm.

To begin, we’ll develop a simple and complete TCP server program. Then we’ll iteratively improve the code as we address concerns such as robustness, modularity, and testability.

Networked services exist to do two things: connect endpoints and transmit information between them. No matter what kind of information is transmitted, a connection must first be made.

In this section, you’ll learn how to create socket-based services using Node.js. We’ll develop an example application that sends data to connected clients, then we’ll connect to this service using standard command-line tools. By the end, you’ll have a good idea of how Node.js does the client/server pattern.

TCP socket connections consist of two endpoints. One endpoint binds to a numbered port while the other endpoint connects to a port.

This is a lot like a telephone system. One phone binds a given phone number for a long time. A second phone places a call—it connects to the bound number. Once the call is answered, information (sound) can travel both ways.

In Node.js, the bind and connect operations are provided by the net module. Binding a TCP port to listen for connections looks like this:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const |

| | net = require('net'), |

| | server = net.createServer(connection => { |

| | // Use the connection object for data transfer. |

| | }); |

| | server.listen(60300); |

The net.createServer method takes a callback function and returns a Server object. Node.js will invoke the callback function whenever another endpoint connects. The connection parameter is a Socket object that you can use to send or receive data.

The callback function defined here is an arrow-function expression, the same kind we used extensively in Chapter 2, Wrangling the File System.

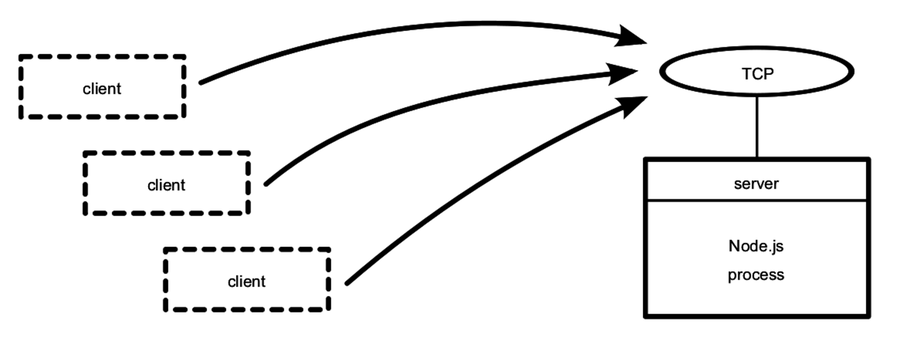

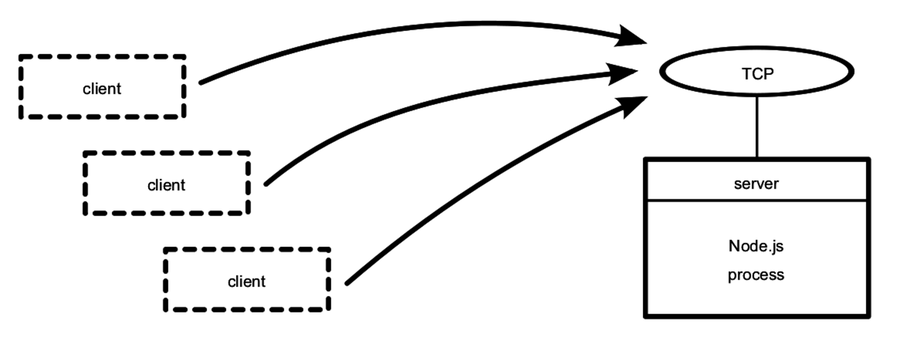

Calling server.listen binds the specified port. In this case, we’re binding TCP port number 60300. To get an idea of the setup, take a look at the figure.

The figure shows our one Node.js process whose server binds a TCP port. Any number of clients—which may or may not be Node.js processes—can connect to that bound port.

Our server program doesn’t do anything with the connection yet. Let’s fix that by using it to send some useful information to the client.

In Chapter 2, Wrangling the File System, we developed some simple file utilities that would take action whenever a target file changed. Let’s reuse the file changes as a source of information for our example networked service. This will give us something to code against as we dig into aspects of Node.js development.

To begin, create a directory named networking to hold the code you’ll be writing. Then open your favorite text editor and enter this:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const fs = require('fs'); |

| | const net = require('net'); |

| | const filename = process.argv[2]; |

| | |

| | if (!filename) { |

| | throw Error('Error: No filename specified.'); |

| | } |

| | |

| | net.createServer(connection => { |

| | // Reporting. |

| | console.log('Subscriber connected.'); |

| | connection.write(`Now watching "${filename}" for changes...\n`); |

| | |

| | // Watcher setup. |

| | const watcher = |

| | fs.watch(filename, () => connection.write(`File changed: ${new Date()}\n`)); |

| | |

| | // Cleanup. |

| | connection.on('close', () => { |

| | console.log('Subscriber disconnected.'); |

| | watcher.close(); |

| | }); |

| | }).listen(60300, () => console.log('Listening for subscribers...')); |

Save this file in your networking directory as net-watcher.js. At the top, we pull in the Node.js core modules fs and net.

The name of the file to watch, if supplied, will be the third (index 2) argument in process.argv. If the user didn’t supply a target file to watch, then we throw a custom Error. Uncaught errors like this will cause the Node.js process to halt after sending a stacktrace to standard error.

Now let’s take a look inside the callback function given to createServer. This callback function does three things:

It reports that the connection has been established (both to the client with connection.write and to the console).

It begins listening for changes to the target file, saving the returned watcher object. This callback sends change information to the client using connection.write.

It listens for the connection’s close event so it can report that the subscriber has disconnected and stop watching the file, with watcher.close.

Finally, notice the callback passed into server.listen at the end. Node.js invokes this function after it has successfully bound port 60300 and is ready to start receiving connections.

Now let’s run the net-watcher program and confirm that it behaves the way we expect. This will require a little terminal juggling.

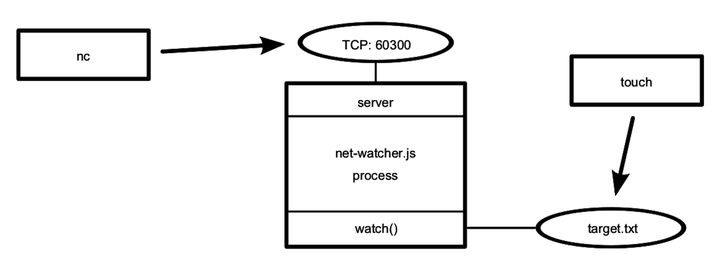

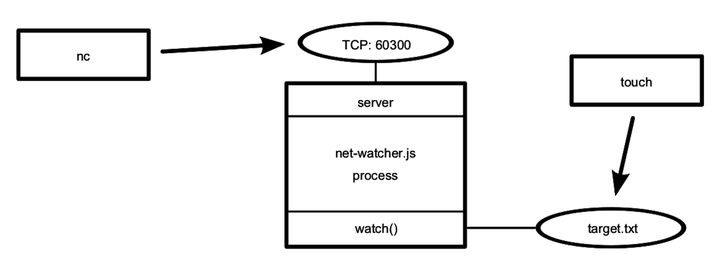

To run and test the net-watcher program, you’ll need three terminal sessions: one for the service itself, one for the client, and one to trigger changes to the watched file.

In your first terminal, use the watch command to touch the target file at one-second intervals:

| | $ watch -n 1 touch target.txt |

With that running, in a second terminal, run the net-watcher program:

| | $ node net-watcher.js target.txt |

| | Listening for subscribers... |

This program creates a service listening on TCP port 60300. To connect to it, we’ll use netcat, a socket utility program. Open a third terminal and use the nc command like so:

| | $ nc localhost 60300 |

| | Now watching "target.txt" for changes... |

| | File changed: Wed Dec 16 2015 05:56:14 GMT-0500 (EST) |

| | File changed: Wed Dec 16 2015 05:56:19 GMT-0500 (EST) |

If you’re on a system that doesn’t have nc, you can use telnet:

| | $ telnet localhost 60300 |

| | Trying 127.0.0.1... |

| | Connected to localhost. |

| | Escape character is '^]'. |

| | Now watching "target.txt" for changes... |

| | File changed: Wed Dec 16 2015 05:56:14 GMT-0500 (EST) |

| | File changed: Wed Dec 16 2015 05:56:19 GMT-0500 (EST) |

| | ^] |

| | telnet> quit |

| | Connection closed. |

Back in the net-watcher terminal, you should see this:

| | Subscriber connected. |

You can kill the nc session by typing Ctrl-C. If you’re using telnet, you’ll need to disconnect with Ctrl-] and then type quit Enter. When you do, you’ll see the following line appear in the net-watcher terminal:

| | Subscriber disconnected. |

To terminate the net-watcher service or the watch command, type Ctrl-C from their terminals.

The following figure outlines the setup we just created. The net-watcher process (box) binds a TCP port and watches a file—both resources are shown as ovals.

Multiple subscribers can connect and receive updates simultaneously. If you open additional terminals and connect to port 60300 with nc, they’ll all receive updates when the target file changes.

TCP sockets are useful for communicating between networked computers. But if you need processes on the same computer to communicate, Unix sockets offer a more efficient alternative. The net module can create this kind of socket as well, which we’ll look at next.

To see how the net module uses Unix sockets, let’s modify the net-watcher program to use this kind of communication channel. Keep in mind that Unix sockets work only on Unix-like environments.

Open the net-watcher.js program and change the .listen call at the end to this:

| | .listen('/tmp/watcher.sock', () => console.log('Listening for subscribers...')); |

Save the file as net-watcher-unix.js, then run the program as before:

| | $ node net-watcher-unix.js target.txt |

| | Listening for subscribers... |

Note that if you get an error containing EADDRINUSE, you may have to delete the watcher.sock before running the program again.

To connect a client, we can use nc as before, but this time specifying the -U flag to use the socket file.

| | $ nc -U /tmp/watcher.sock |

| | Now watching target.txt for changes... |

Unix sockets can be faster than TCP sockets because they don’t require invoking network hardware. However, by nature they’re confined to the machine.

That concludes the basics of creating network socket servers in Node. We discovered how to create socket servers and connect to them using the common client utility program nc. This framework will supply the backdrop for the rest of the examples in the chapter.

Next, we’ll beef up our service by transforming the data into a parsable format. This will put us in position to develop custom client applications.

We’ve just explored how to create socket servers that listen for incoming connections in Node. So far, our example programs have sent plain-text messages that are meant to be read by a human. In this section we’ll design and implement a better protocol.

A protocol is a set of rules that defines how endpoints in a system communicate. Any time you develop a networked application in Node.js, you’re working with one or more protocols. Here we’ll create a protocol based on passing JSON messages over TCP.

JSON is incredibly prevalent in Node.js. We’ll use it extensively for data serialization and configuration throughout the book. It is significantly easier to program clients against than plain text, and it’s still human-readable.

We’ll implement client and server endpoints that use our new JSON-based protocol. This will give us opportunities to develop test cases and refactor our code into reusable modules.

Let’s develop the message-passing protocol that uses JSON to serialize messages. Each message is a JSON-serialized object, which is a hash of key-value pairs. Here’s an example JSON object with two key-value pairs:

| | {"key":"value","anotherKey":"anotherValue"} |

The net-watcher service we’ve been developing in this chapter sends two kinds of messages that we need to convert to JSON:

When the connection is first established, the client receives the string Now watching "target.txt" for changes....

Whenever the target file changes, the client receives a string like this: File changed: Fri Dec 18 2015 05:44:00 GMT-0500 (EST).

We’ll encode the first kind of message this way:

| | {"type":"watching","file":"target.txt"} |

The type field indicates that this is a watching message—the specified file is now being watched.

The second type of message is encoded this way:

| | {"type":"changed","timestamp":1358175733785} |

Here the type field announces that the target file has changed. The timestamp field contains an integer value representing the number of milliseconds since midnight, January 1, 1970. This happens to be an easy time format to work with in JavaScript. For example, you can get the current time in this format with Date.now.

Notice that there are no line breaks in our JSON messages. Although JSON is whitespace agnostic—it ignores whitespace outside of string values—our protocol will use newlines only to separate messages. We’ll refer to this protocol as line-delimited JSON (LDJ).

Now that we’ve defined an improved, computer-accessible protocol, let’s modify the net-watcher service to use it. Then we’ll create client programs that receive and interpret these messages.

Our task is to use JSON.stringify to encode message objects and send them out through connection.write. JSON.stringify takes a JavaScript object, and returns a string containing a serialized representation of that object in JSON form.

Open your editor to the net-watcher.js program. Find the following line:

| | connection.write(`Now watching "${filename}" for changes...\n`); |

And replace it with this:

| | connection.write(JSON.stringify({type: 'watching', file: filename}) + '\n'); |

Next, find the call to connection.write inside the watcher:

| | const watcher = |

| | fs.watch(filename, () => connection.write(`File changed: ${new Date()}\n`)); |

And replace it with this:

| | const watcher = fs.watch(filename, () => connection.write( |

| | JSON.stringify({type: 'changed', timestamp: Date.now()}) + '\n')); |

Save this updated file as net-watcher-json-service.js. Run the new program as always, remembering to specify a target file:

| | $ node net-watcher-json-service.js target.txt |

| | Listening for subscribers... |

Then connect using netcat from a second terminal:

| | $ nc localhost 60300 |

| | {"type":"watching","file":"target.txt"} |

When you touch the target.txt file, you’ll see output like this from your client:

| | {"type":"changed","timestamp":1450437616760} |

Now we’re ready to write a client program that processes these messages.

So far in this chapter, we’ve explored the server side of Node.js sockets. Here we’ll write a client program in Node.js to receive JSON messages from our net-watcher-json-service program. We’ll start with a naive implementation, and then improve upon it through the rest of the chapter.

Open an editor and insert this:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const net = require('net'); |

| | const client = net.connect({port: 60300}); |

| | client.on('data', data => { |

| | const message = JSON.parse(data); |

| | if (message.type === 'watching') { |

| | console.log(`Now watching: ${message.file}`); |

| | } else if (message.type === 'changed') { |

| | const date = new Date(message.timestamp); |

| | console.log(`File changed: ${date}`); |

| | } else { |

| | console.log(`Unrecognized message type: ${message.type}`); |

| | } |

| | }); |

Save this program as net-watcher-json-client.js.

This short program uses net.connect to create a client connection to localhost port 60300, then waits for data. The client object is a Socket, just like the incoming connection we saw on the server side.

Whenever a data event happens, our callback function takes the incoming buffer object, parses the JSON message, and then logs an appropriate message to the console.

To run the program, first make sure the net-watcher-json-service is running. Then, in another terminal, run the client:

| | $ node net-watcher-json-client.js |

| | Now watching: target.txt |

If you touch the target file, you’ll see output like this:

| | File changed: Mon Dec 21 2015 05:34:19 GMT-0500 (EST) |

Success! This program works, but it’s far from perfect. Consider what happens when the connection ends or if it fails to connect in the first place. This program listens for only data events, not end events or error events. We could listen for these events and take appropriate action when they happen.

But there’s actually a deeper problem lurking in our code—caused by assumptions we’ve made about message boundaries. In the next section we’ll develop a test that exposes this bug so we can fix it.

Functional tests assure us that our code does what we expect it to do. In this section, we’ll develop a test for our networked file-watching server and client programs. We’ll create a mock server that conforms to our LDJ protocol while exposing flaws in the client.

After we write the test, we’ll fix the client code so that it passes. This will bring up many Node.js concepts, including extending core classes, creating and using custom modules, and developing on top of EventEmitters. But first we need to understand a problem lurking in our client/server programs as currently written.

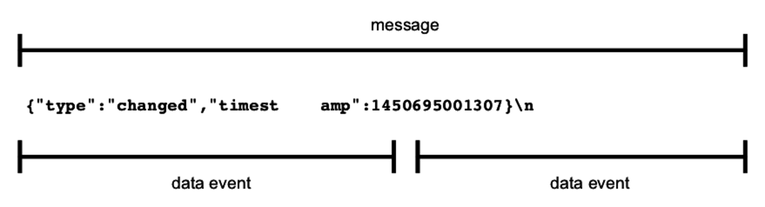

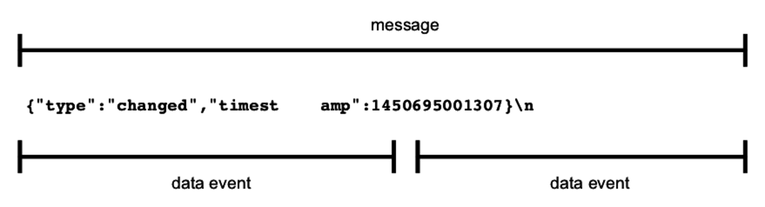

When you develop networked programs in Node.js, they’ll often communicate by passing messages. In the best case, a message will arrive all at once. But sometimes messages will arrive in pieces, split into distinct data events. To develop networked applications, you’ll need to deal with these splits when they happen.

The LDJ protocol we developed earlier separates messages with newline characters. Each newline character is the boundary between two messages. Here’s an example of a series of messages, with newline characters specifically called out:

| | {"type":"watching","file":"target.txt"}\n |

| | {"type":"changed","timestamp":1450694370094}\n |

| | {"type":"changed","timestamp":1450694375099}\n |

Recall the service we’ve been developing so far in this chapter. Whenever a change happens, it encodes and sends a message to the connection, including the trailing newline. Each line of output corresponds to a single data event in the connected client. Or, to put it another way, the data event boundaries exactly match up with the message boundaries.

Our client program currently relies on this behavior. It parses each message by sending the contents of the data buffer directly into JSON.parse:

| | client.on('data', data => { |

| | const message = JSON.parse(data); |

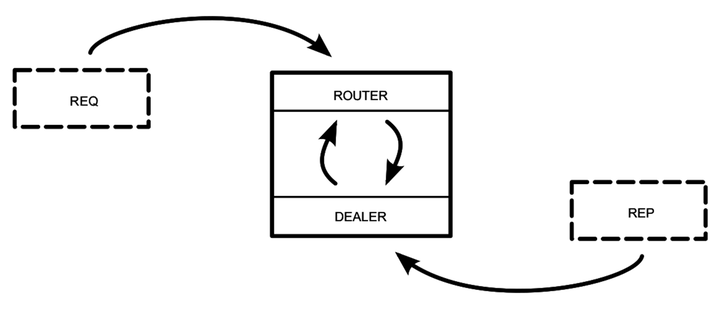

But consider what would happen if a message were split down the middle, and arrived as two separate data events. Such a split could happen in the wild, especially for large messages. The following figure shows an example of a split message.

Let’s create a test service that sends a split message like this one and find out how the client responds.

Writing robust Node.js applications means gracefully handling network problems like split inputs, broken connections, and bad data. Here we’ll implement a test service that purposefully splits a message into multiple chunks.

Open your editor and enter this:

| | 'use strict'; |

| | const server = require('net').createServer(connection => { |

| | console.log('Subscriber connected.'); |

| | |

| | // Two message chunks that together make a whole message. |

| | const firstChunk = '{"type":"changed","timesta'; |

| | const secondChunk = 'mp":1450694370094}\n'; |

| | |

| | // Send the first chunk immediately. |

| | connection.write(firstChunk); |

| | |

| | // After a short delay, send the other chunk. |

| | const timer = setTimeout(() => { |

| | connection.write(secondChunk); |

| | connection.end(); |

| | }, 100); |

| | |

| | // Clear timer when the connection ends. |

| | connection.on('end', () => { |

| | clearTimeout(timer); |

| | console.log('Subscriber disconnected.'); |

| | }); |

| | }); |

| | |

| | server.listen(60300, function() { |

| | console.log('Test server listening for subscribers...'); |

| | }); |

Save this file as test-json-service.js and run it:

| | $ node test-json-service.js |

| | Test server listening for subscribers... |

This test service differs from our previous net-watcher-json-service.js in a few ways. Rather than setting up a filesystem watcher, as we did for the real service, here we just send the first predetermined chunk immediately.