Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Sunith Shetty

Acquisition Editor: Nelson Morris

Content Development Editor: Ronnel Mathew

Technical Editor: Sagar Sawant

Copy Editor: Safis Editing

Project Coordinator: Namrata Swetta

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Rekha Nair

Graphics: Jisha Chirayil

Production Coordinator: Aparna Bhagat

First published: December 2018

Production reference: 1281218

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78899-228-2

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.packt.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at customercare@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.packt.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Soma Halder is the data science lead of the big data analytics group at Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd, one of India's largest telecom companies. She specializes in analytics, big data, cybersecurity, and machine learning. She has approximately 10 years of machine learning experience, especially in the field of cybersecurity. She studied at the University of Alabama, Birmingham where she did her master's with an emphasis on Knowledge discovery and Data Mining and computer forensics. She has worked for Visa, Salesforce, and AT&T. She has also worked for start-ups, both in India and the US (E8 Security, Headway ai, and Norah ai). She has several conference publications to her name in the field of cybersecurity, machine learning, and deep learning.

Sinan Ozdemir is a data scientist, start-up founder, and educator living in the San Francisco Bay Area. He studied pure mathematics at the Johns Hopkins University. He then spent several years conducting lectures on data science there, before founding his own start-up, Kylie ai, which uses artificial intelligence to clone brand personalities and automate customer service communications. He is also the author of Principles of Data Science, available through Packt.

Chiheb Chebbi is a Tunisian InfoSec enthusiast, author, and technical reviewer with experience in various aspects of information security, focusing on the investigation of advanced cyber attacks and researching cyber espionage. His core interest lies in penetration testing, machine learning, and threat hunting. He has been included in many halls of fame. His talk proposals have been accepted by many world-class information security conferences.

Dr. Aditya Mukherjee is a cybersecurity veteran with more than 11 years experience in security consulting for various Fortune 500's and government entities, managing large teams focusing on customer relationships, and building service lines. He started his career as an entrepreneur, specializing in the implementation of cybersecurity solutions/cybertransformation projects, and solving challenges associated with security architecture, framework, and policies.

During his career, he has been bestowed with various industry awards and recognition, of which the most recent are most innovative/dynamic CISO of the year-2018, Cyber Sentinel of the year, and an honorary doctorate–for excellence in the field of management.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

The damage that cyber threats can wreak upon an organization can be incredibly costly. In this book, we use the most efficient and effective tools to solve the big problems that exist in the cybersecurity domain and provide cybersecurity professionals with the knowledge they need to use machine learning algorithms. This book aims to bridge the gap between cybersecurity and machine learning, focusing on building new and more effective solutions to replace traditional cybersecurity mechanisms and provide a collection of algorithms that empower systems with automation capabilities.

This book walks you through the major phases of the threat life cycle, detailing how you can implement smart solutions for your existing cybersecurity products and effectively build intelligent and future-proof solutions. We'll look at the theory in depth, but we'll also study practical applications of that theory, framed in the contexts of real-world security scenarios. Each chapter is focused on self-contained examples for solving real-world concerns using machine learning algorithms such as clustering, k-means, linear regression, and Naive Bayes.

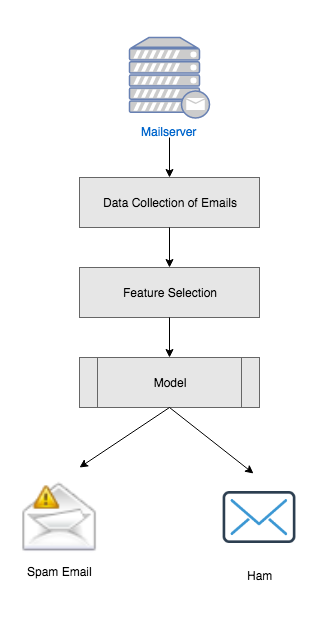

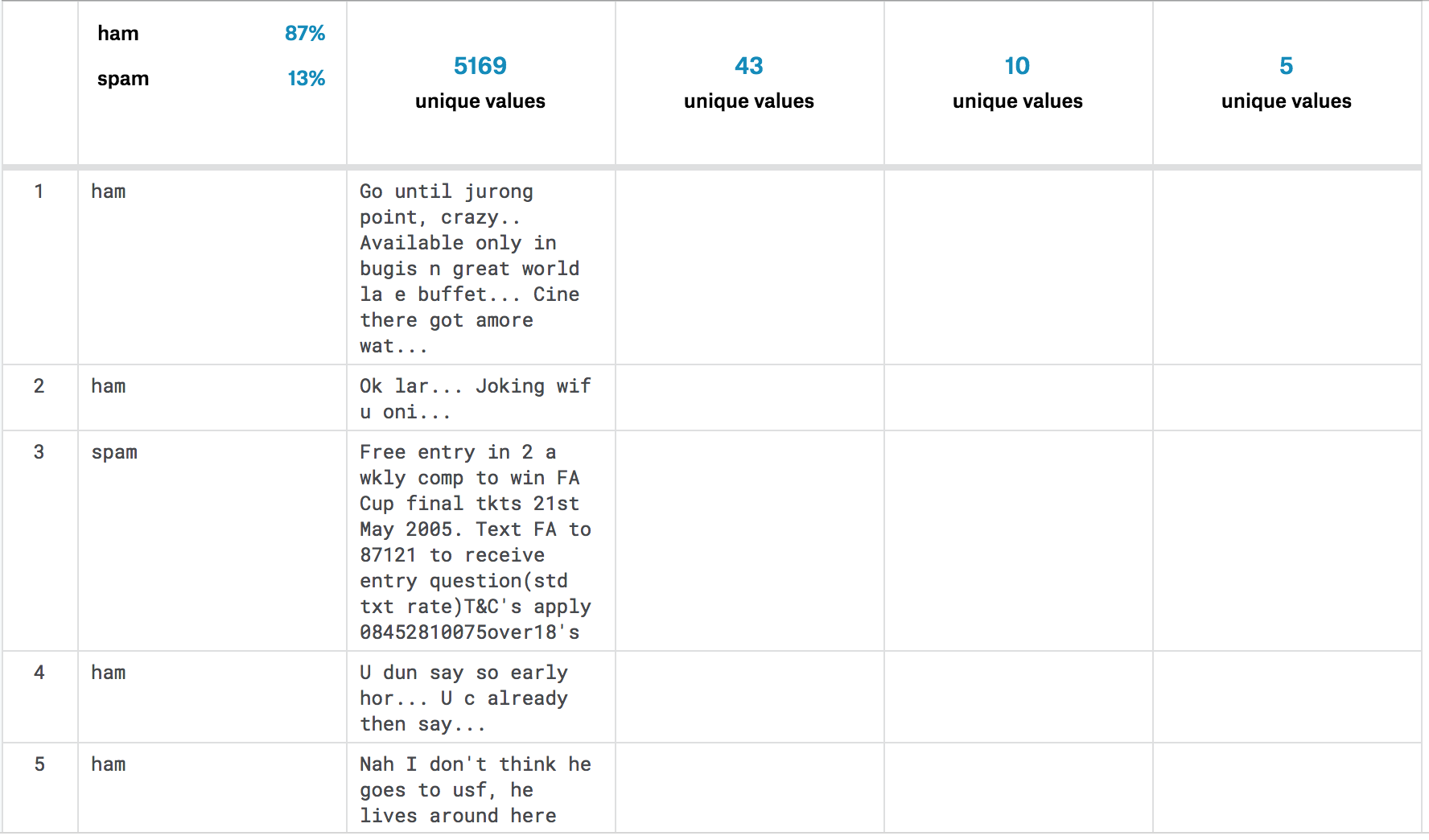

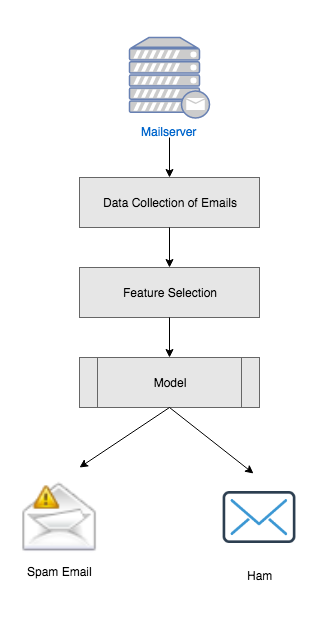

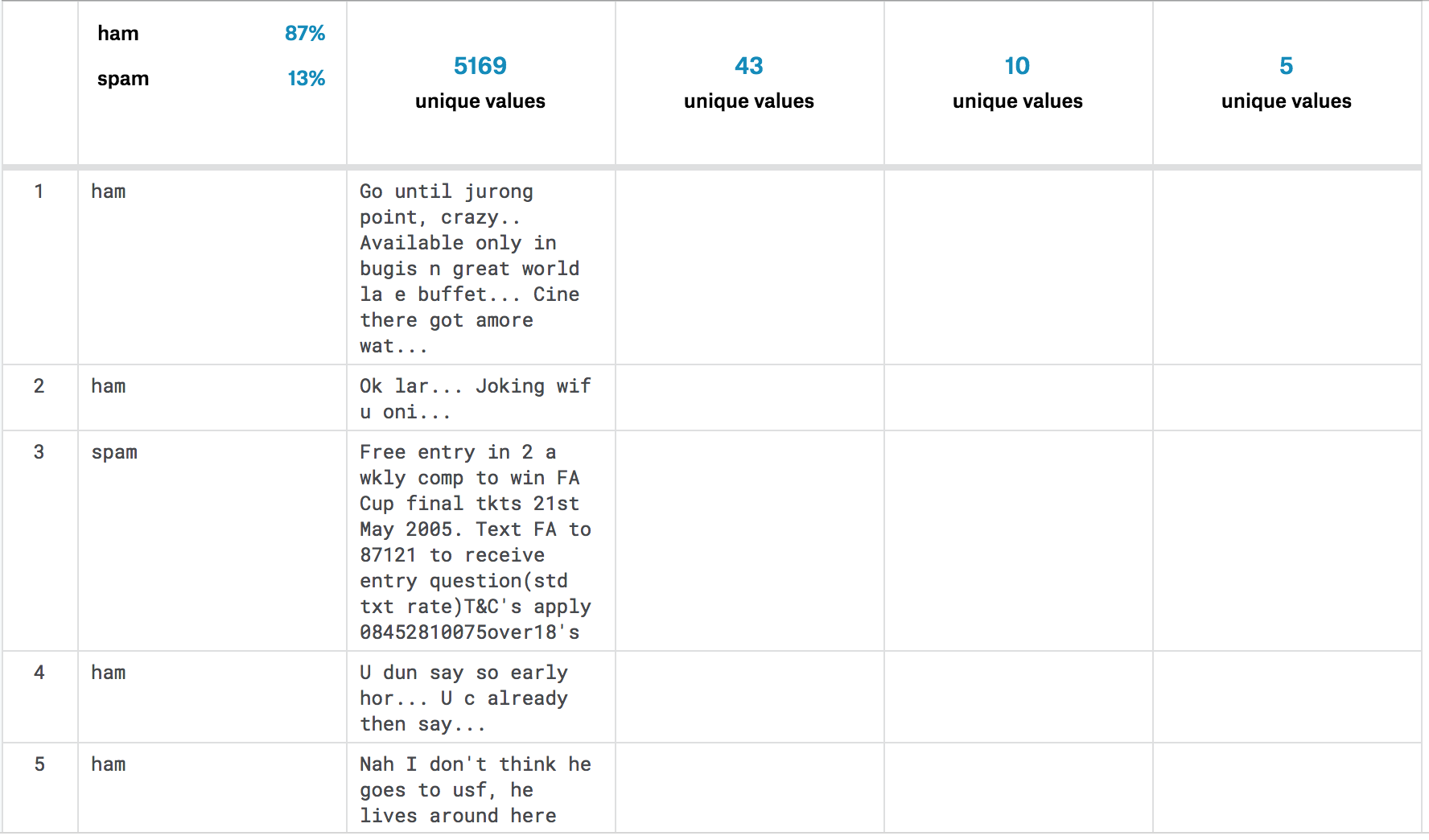

We begin by looking at the basics of machine learning in cybersecurity using Python and its extensive library support. You will explore various machine learning domains, including time series analysis and ensemble modeling, to get your foundations right. You will build a system to identify malicious URLs, and build a program for detecting fraudulent emails and spam. After that, you will learn how to make effective use of the k-means algorithm to develop a solution to detect and alert you about any malicious activity in the network. Also, you'll learn how to implement digital biometrics and fingerprint authentication to validate whether the user is a legitimate user or not.

This book takes a solution-oriented approach to helping you solve existing cybersecurity issues.

This book is for data scientists, machine learning developers, security researchers, and anyone who is curious about applying machine learning to enhance computer security. Having a working knowledge of Python, the basics of machine learning, and cybersecurity fundamentals will be useful.

Chapter 1, Basics of Machine Learning in Cybersecurity, introduces machine learning and its use cases in the cybersecurity domain. We introduce you to the overall architecture for running machine learning modules and go, in great detail, through the different subtopics in the machine learning landscape.

Chapter 2, Time Series Analysis and Ensemble Modeling, covers two important concepts of machine learning: time series analysis and ensemble learning. We will also analyze historic data and compare it with current data to detect deviations from normal activity.

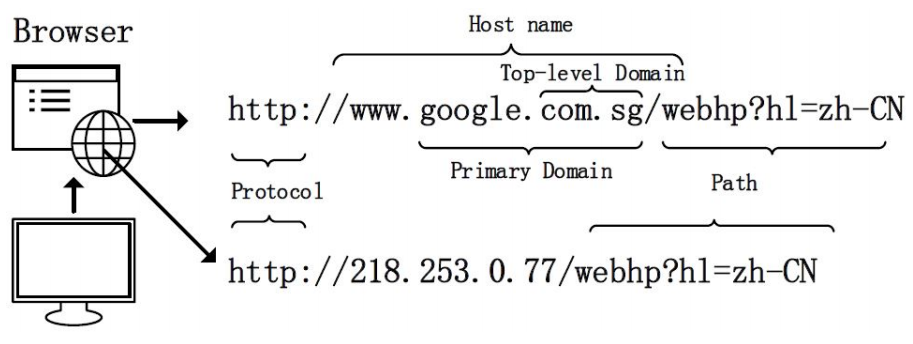

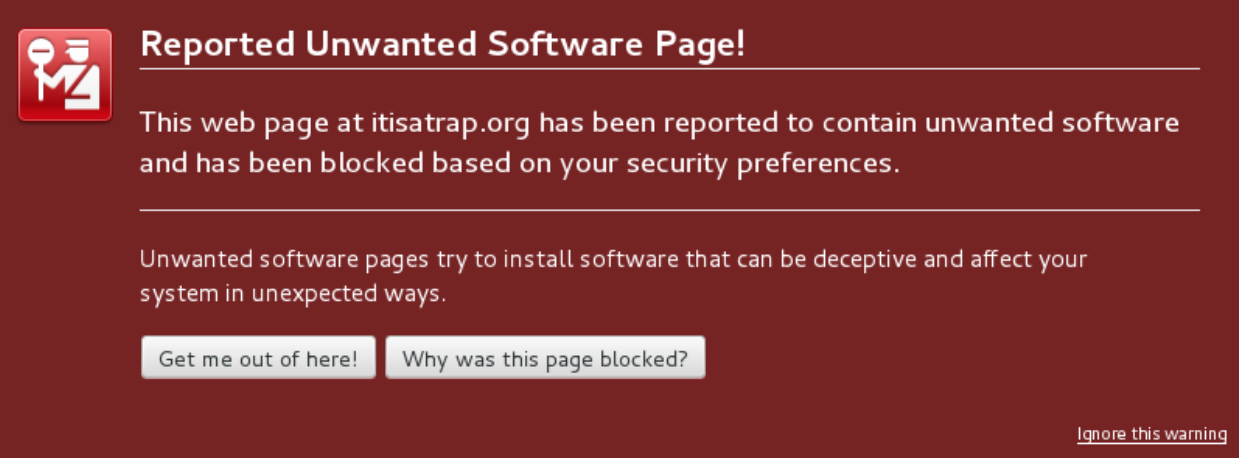

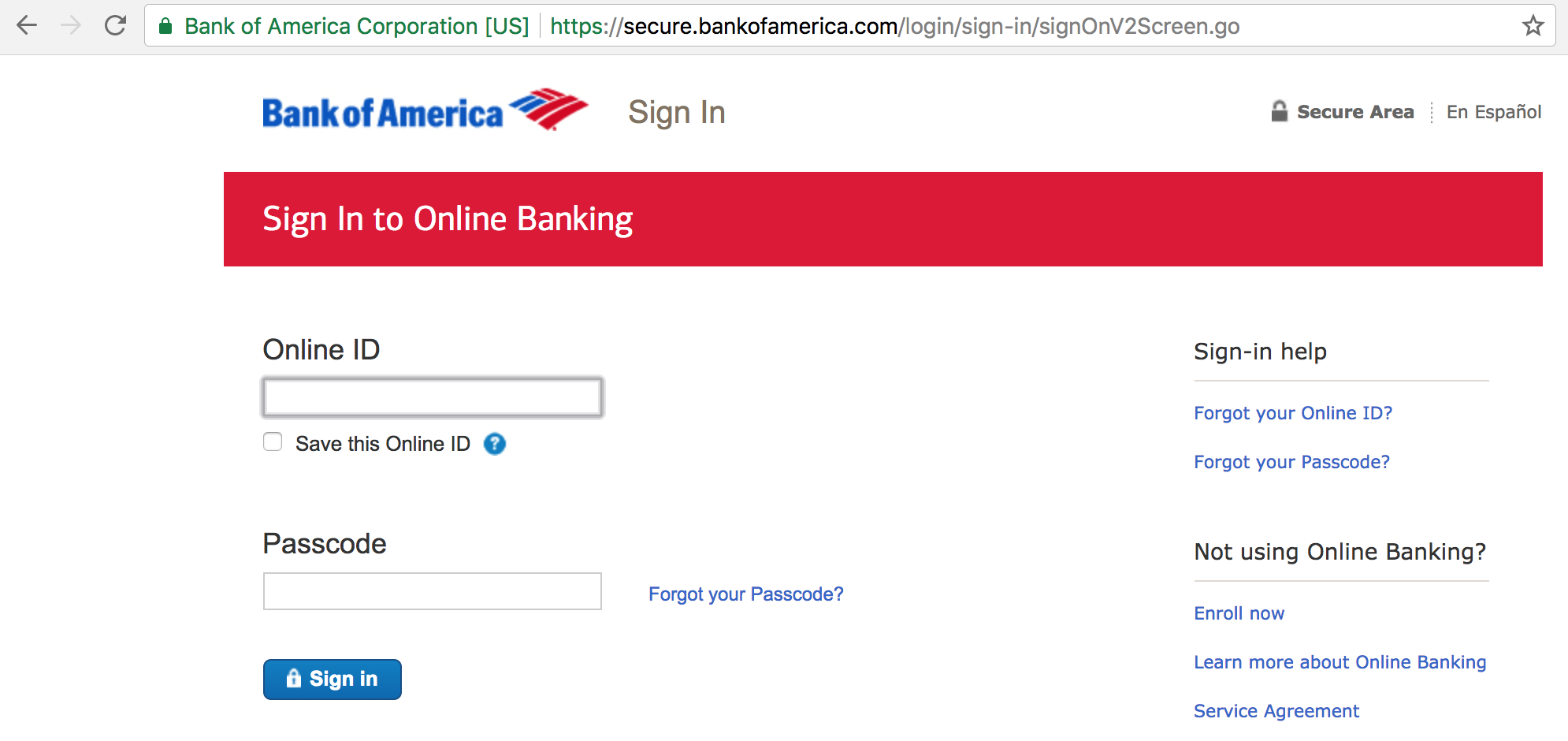

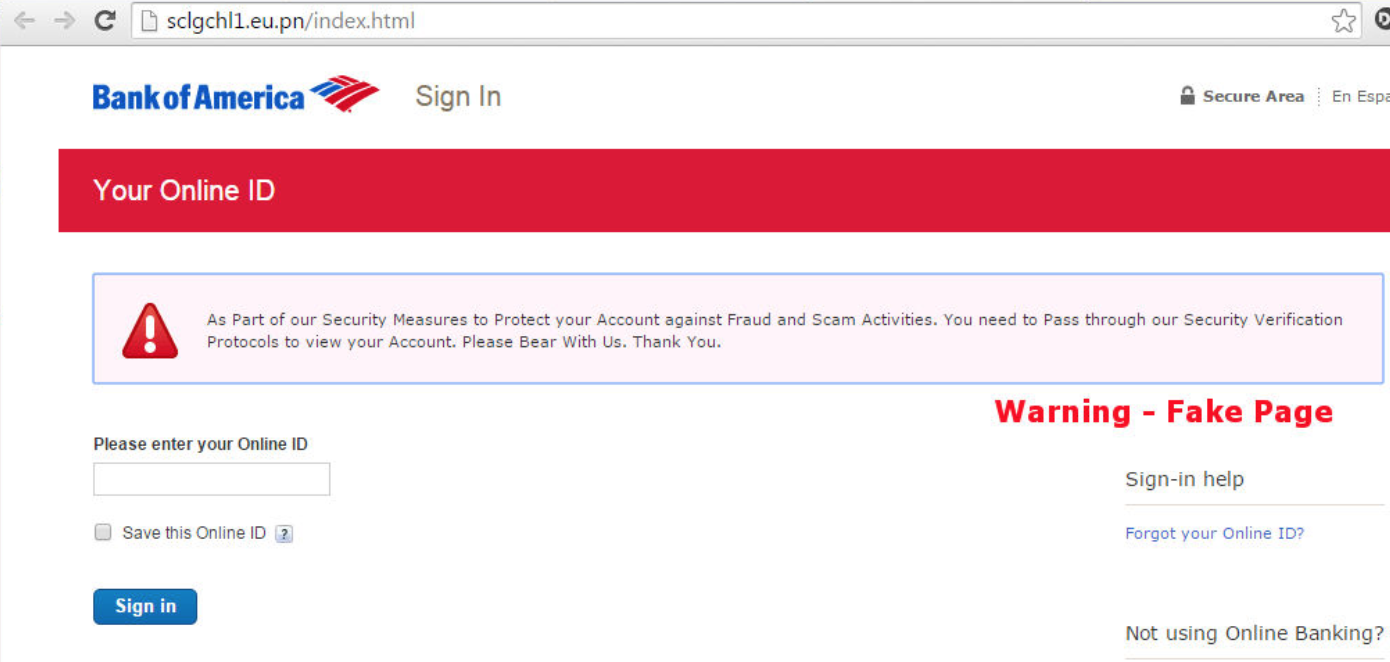

Chapter 3, Segregating Legitimate and Lousy URLs, examines how URLs are used. We will also study malicious URLs and how to detect them, both manually and using machine learning.

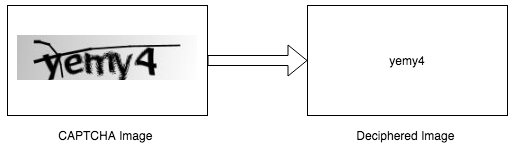

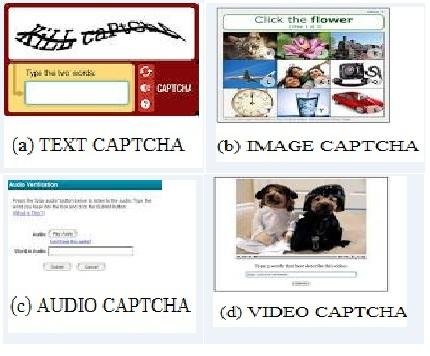

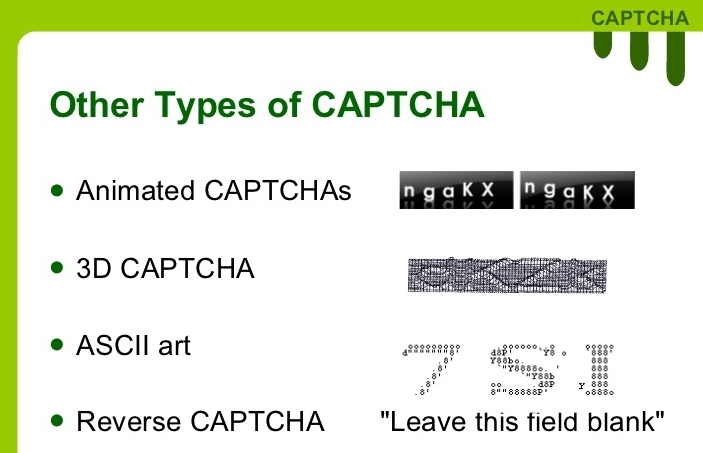

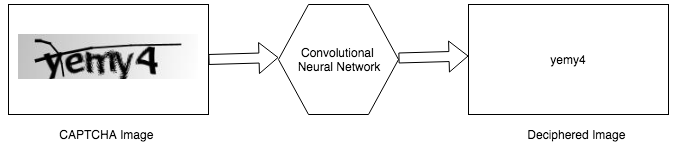

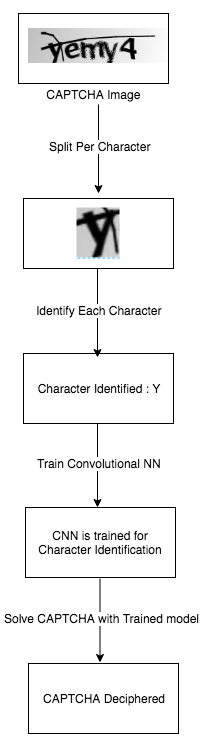

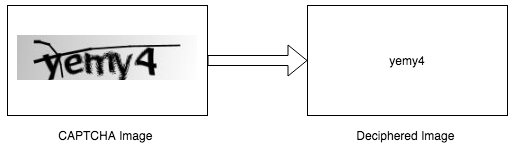

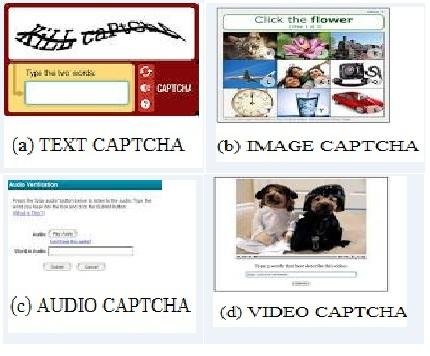

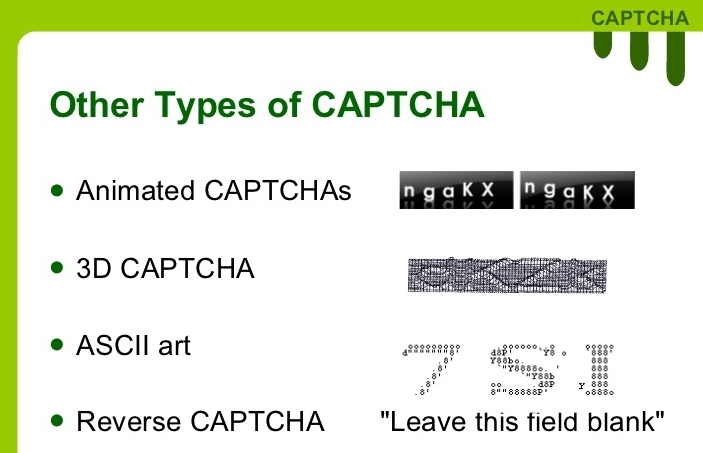

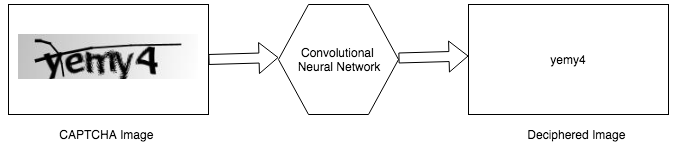

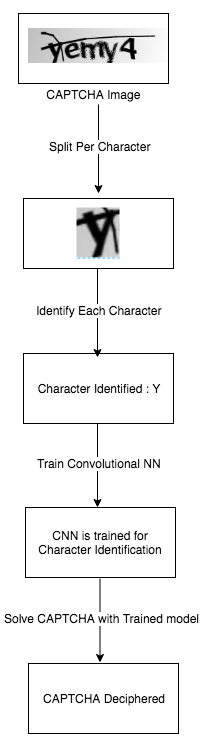

Chapter 4, Knocking Down CAPTCHAs, teaches you about the different types of CAPTCHA and their characteristics. We will also see how we can solve CAPTCHAs using artificial intelligence and neural networks.

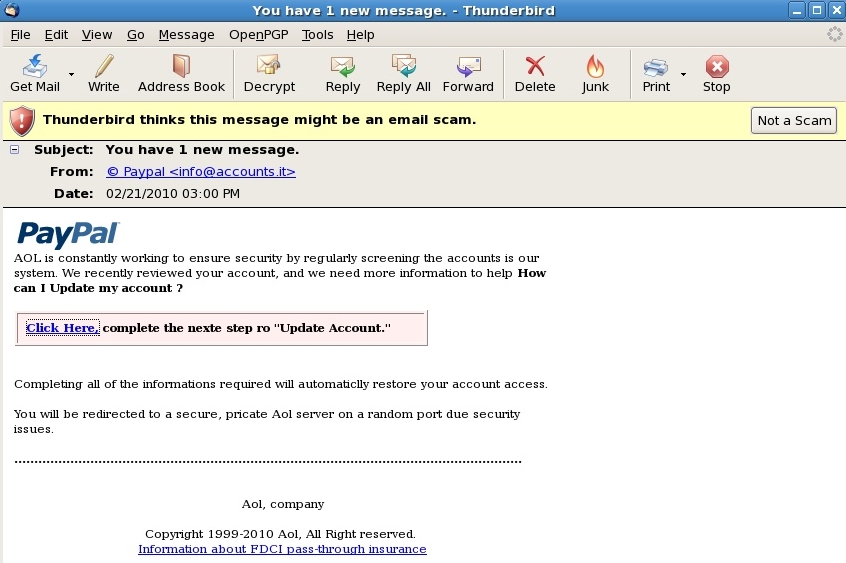

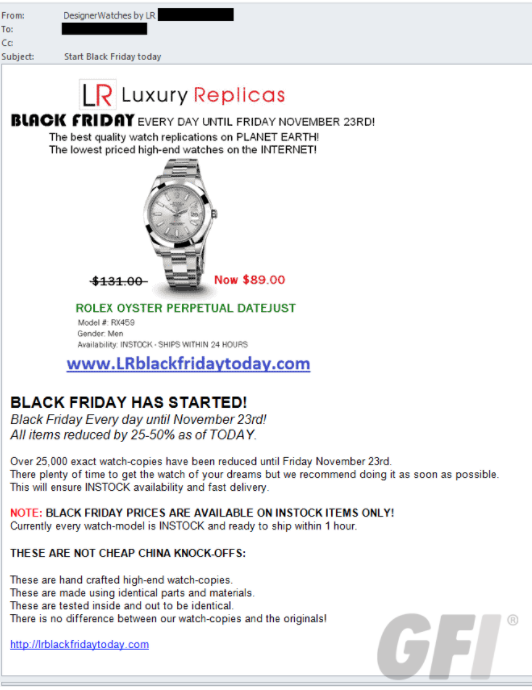

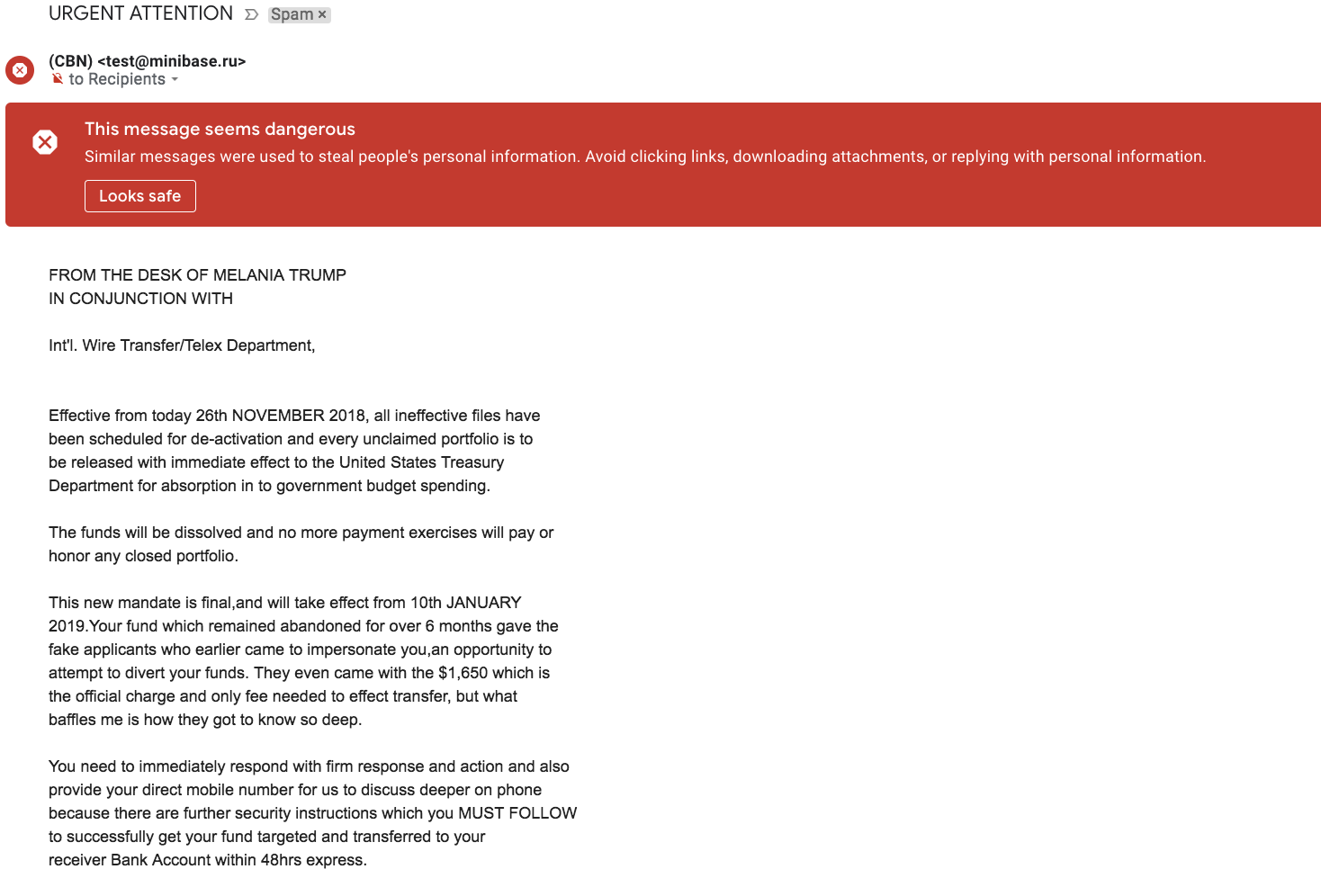

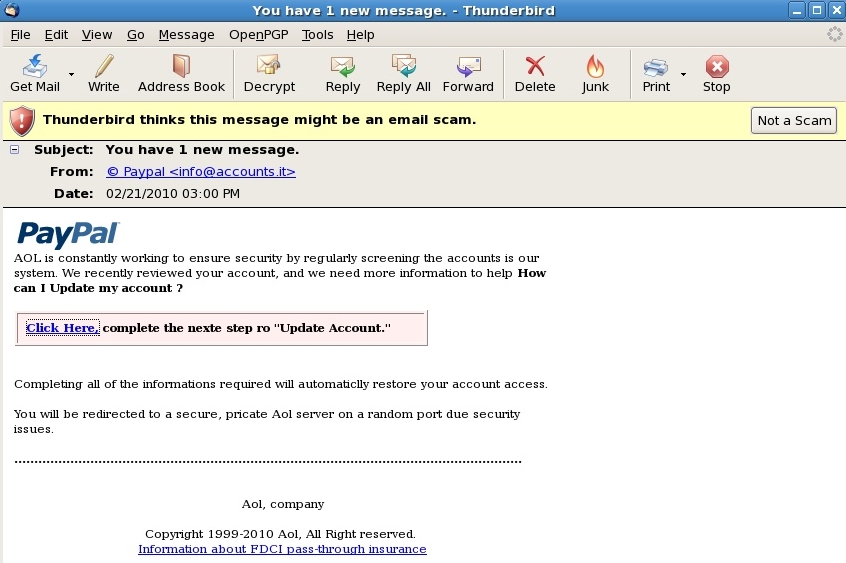

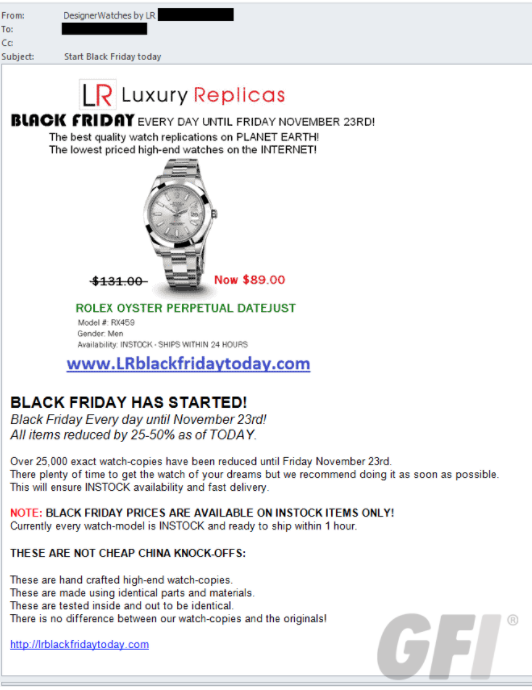

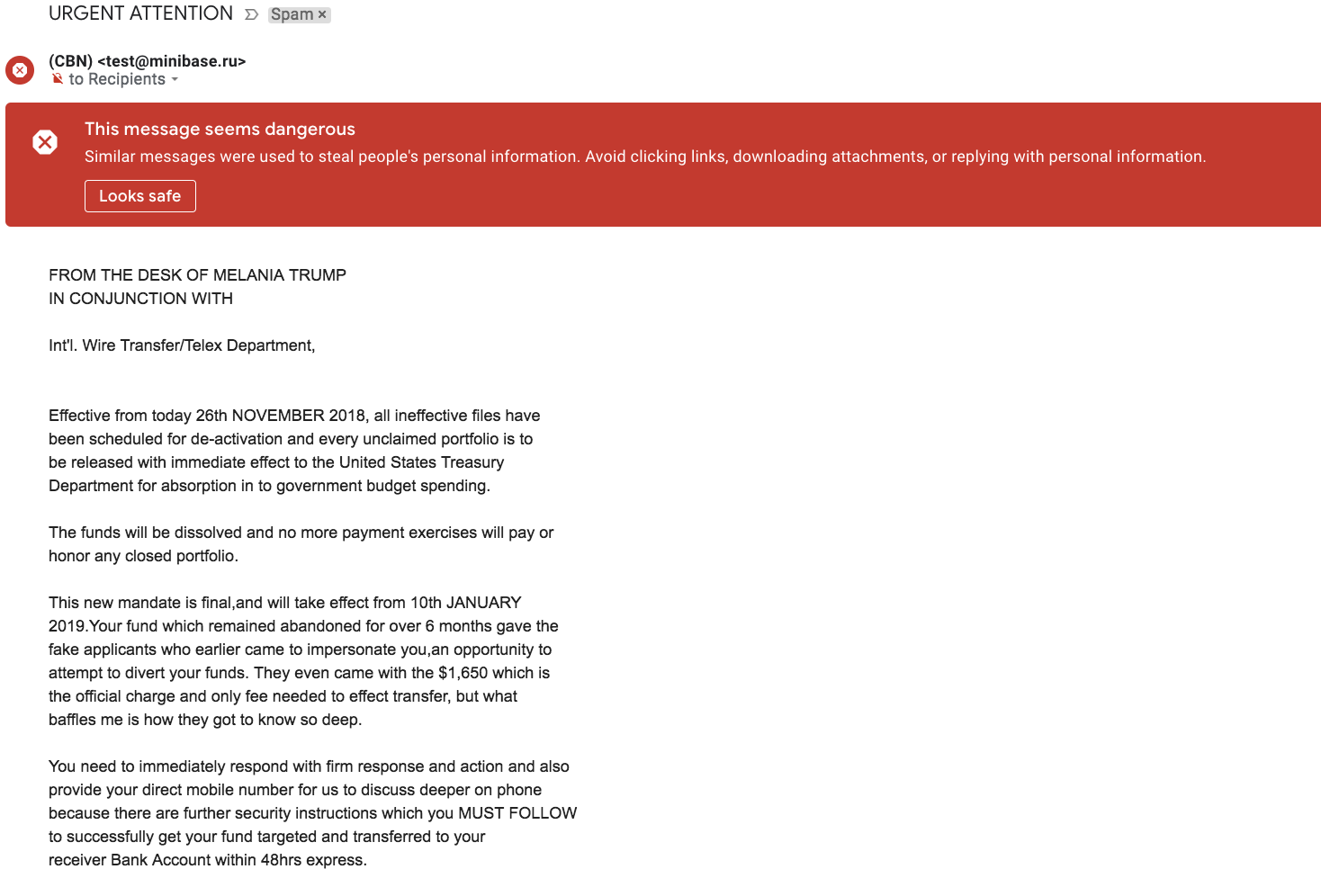

Chapter 5, Using Data Science to Catch Email Fraud and Spam, familiarizes you with the different types of spam email and how they work. We will also look at a few machine learning algorithms for detecting spam and learn about the different types of fraudulent email.

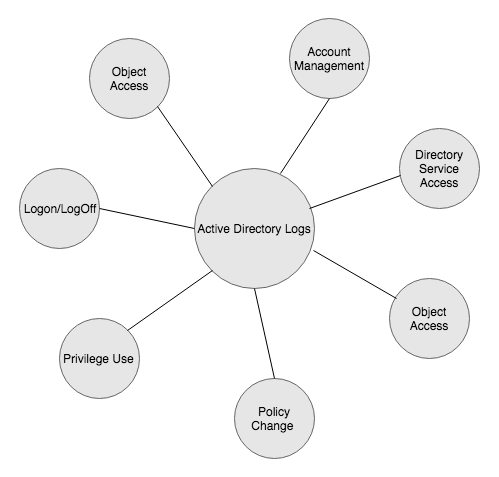

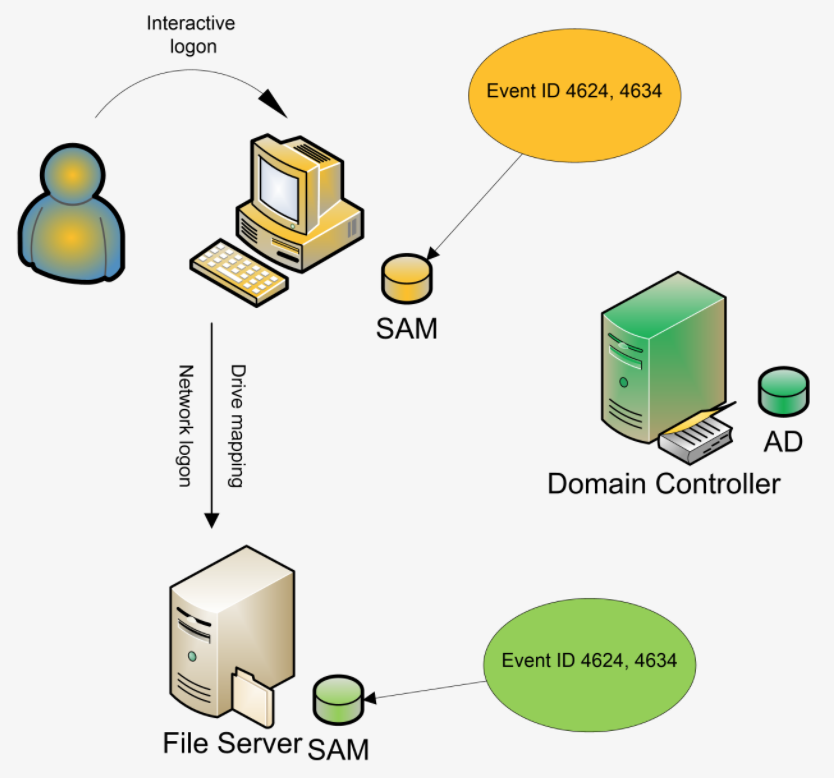

Chapter 6, Efficient Network Anomaly Detection Using k-means, gets into the various stages of network attacks and how to deal with them. We will also write a simple model that will detect anomalies in the Windows and activity logs.

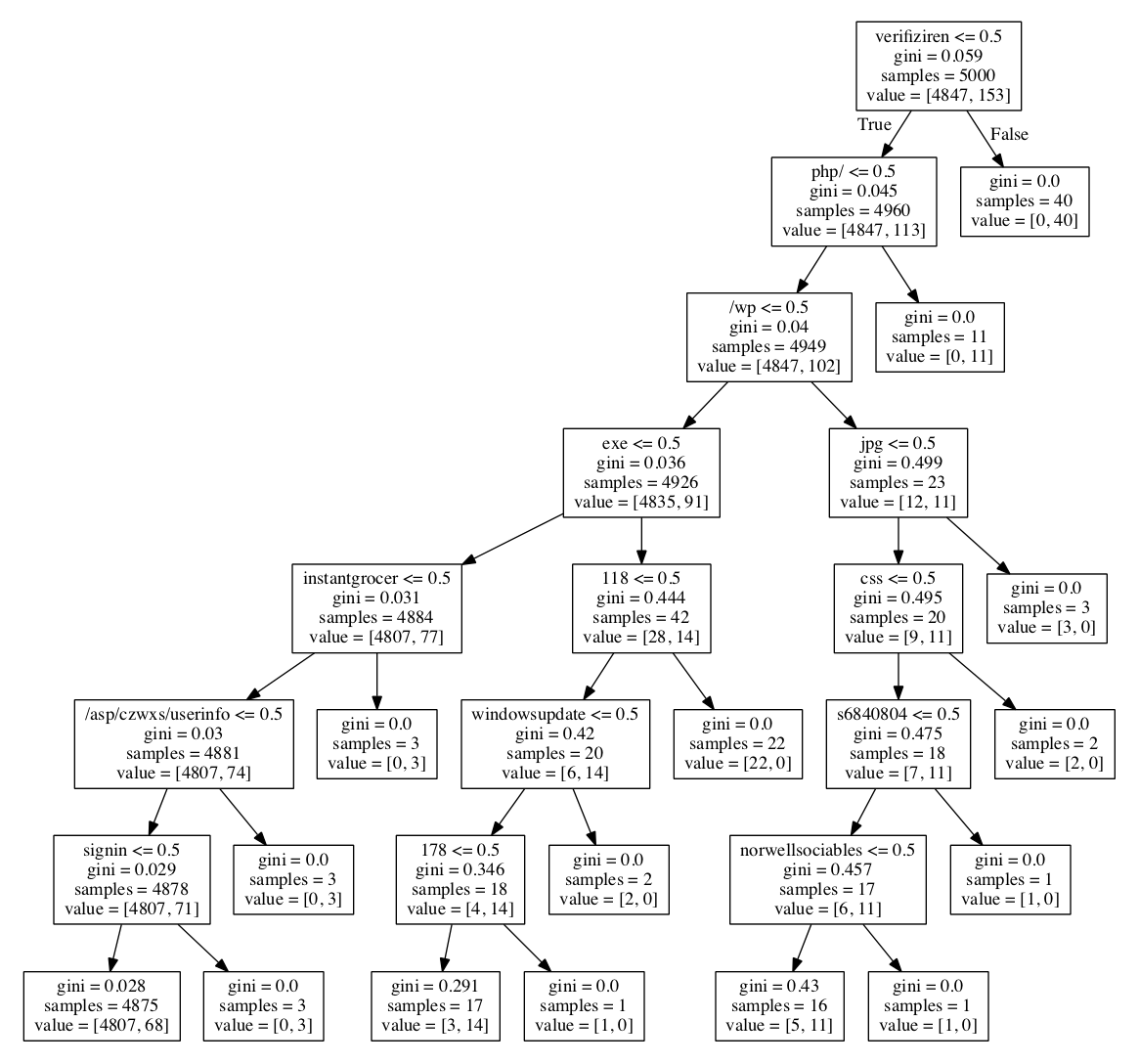

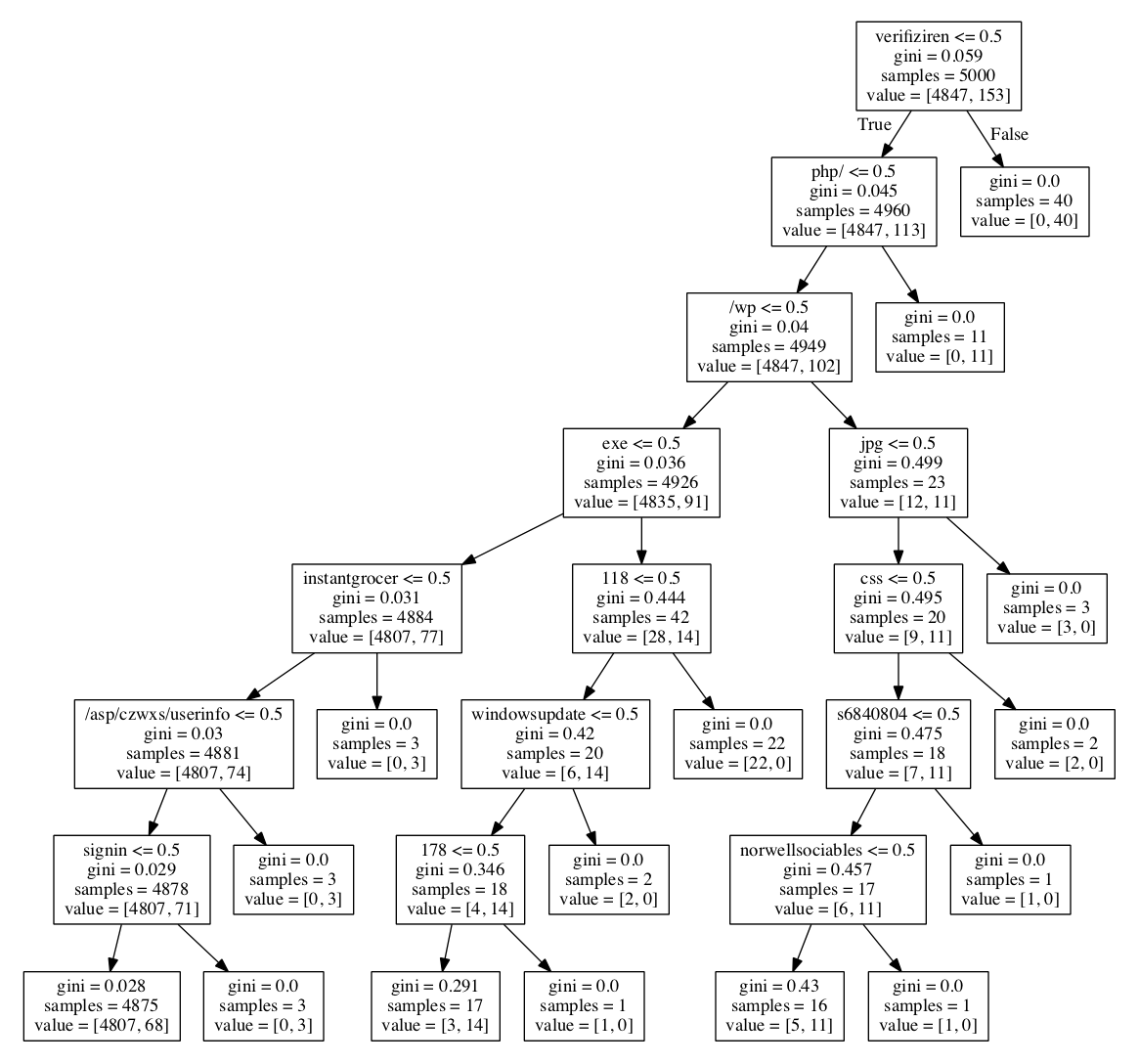

Chapter 7, Decision Tree- and Context-Based Malicious Event Detection, discusses malware in detail and looks at how malicious data is injected in databases and wireless networks. We will use decision trees for intrusion and malicious URL detection.

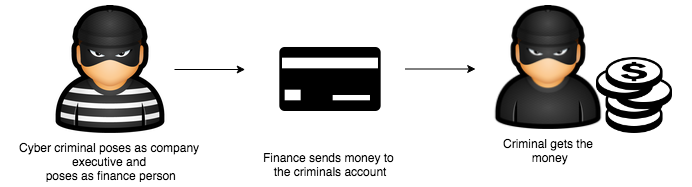

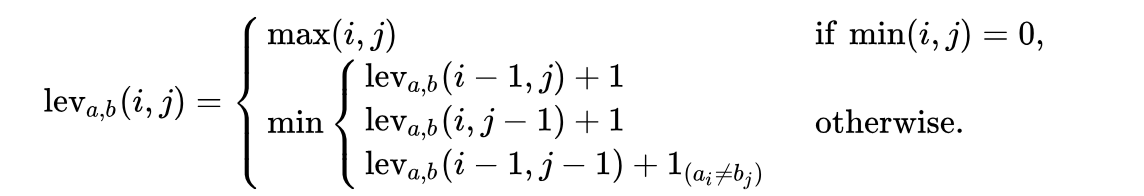

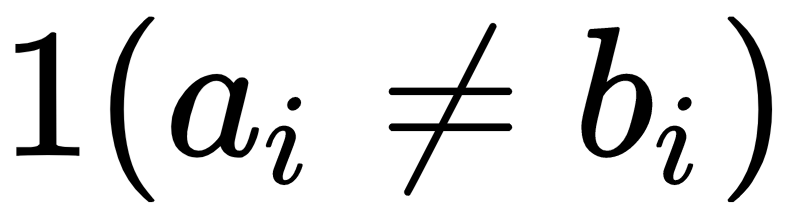

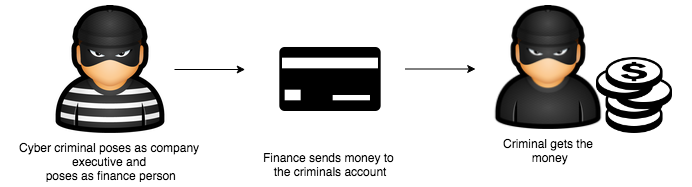

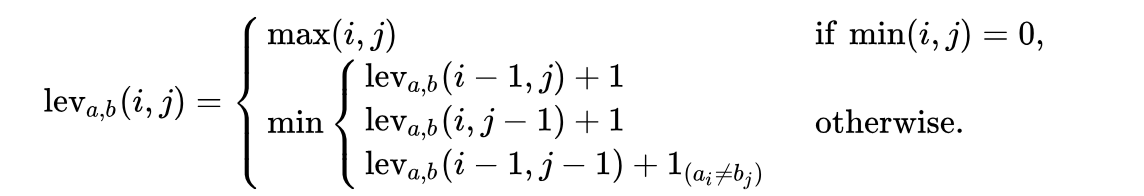

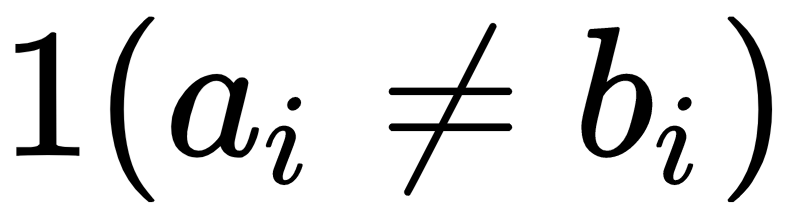

Chapter 8, Catching Impersonators and Hackers Red Handed, delves into impersonation and its different types, and also teaches you about Levenshtein distance. We will also learn how to find malicious domain similarity and authorship attribution.

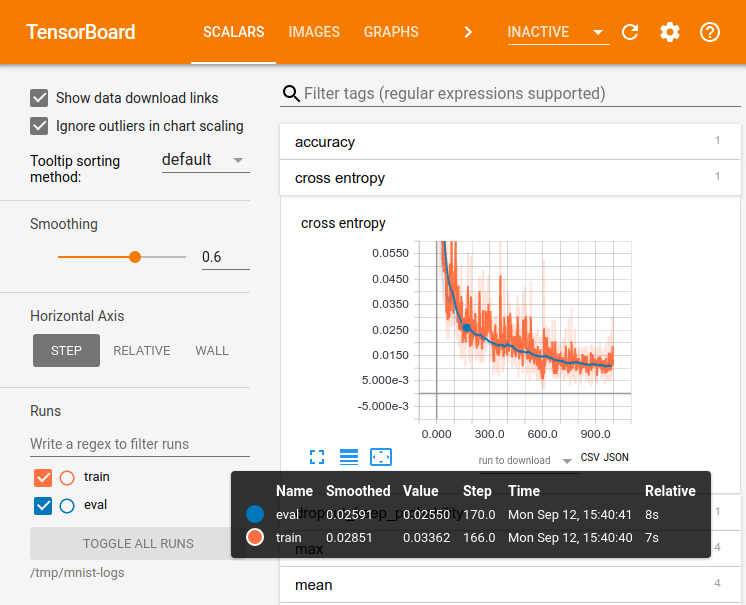

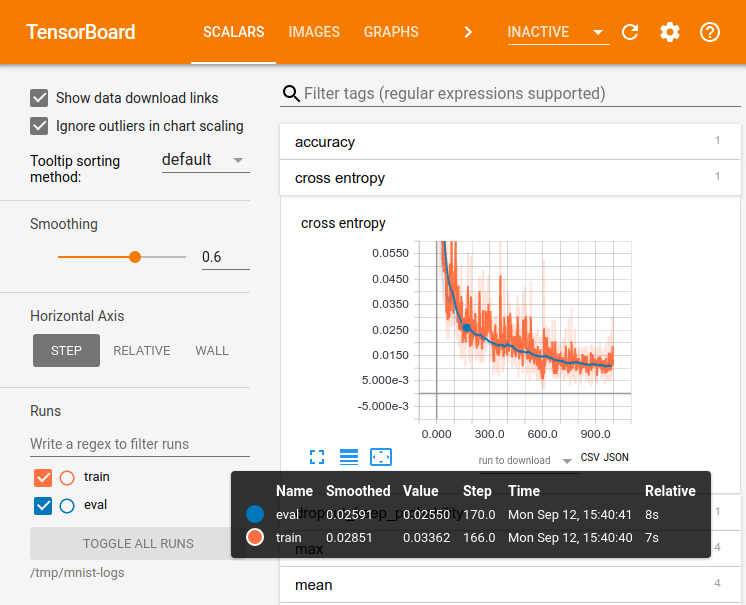

Chapter 9, Changing the Game with TensorFlow, covers all things TensorFlow, from installation and the basics to using it to create a model for intrusion detection.

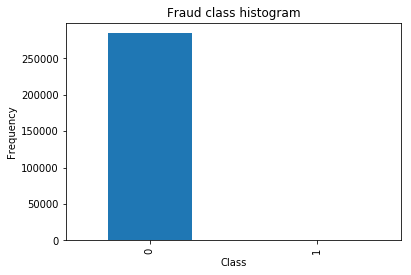

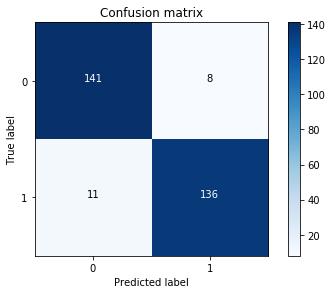

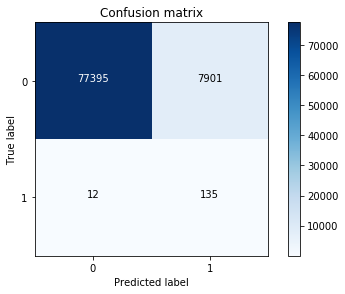

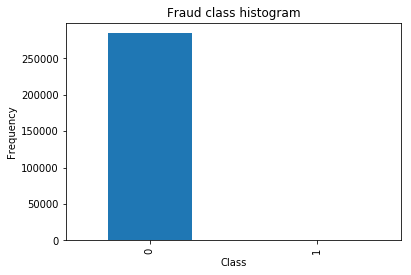

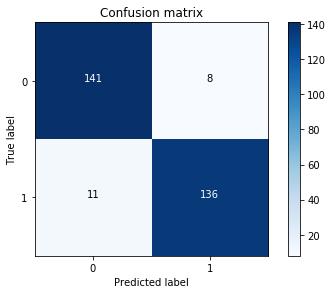

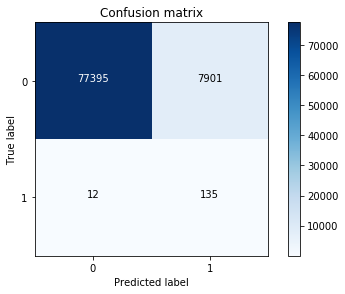

Chapter 10, Financial Fraud and How Deep Learning Can Mitigate It, explains how we can use machine learning to mitigate fraudulent transactions. We will also see how to handle data imbalance and detect credit card fraud using logistic regression.

Chapter 11, Case Studies, explores using SplashData to perform password analysis on over one million passwords. We will create a model to extract passwords using scikit-learn and machine learning.

Readers should have basic knowledge of cybersecurity products and machine learning.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packt.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packt.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Hands-on-Machine-Learning-for-Cyber-Security. In case there's an update to the code, it will be updated on the existing GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: http://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/9781788992282_ColorImages.pdf.

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "The SVM package available in the sklearn package."

A block of code is set as follows:

def url_has_exe(url):

if url.find('.exe')!=-1:

return 1

else :

return 0

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

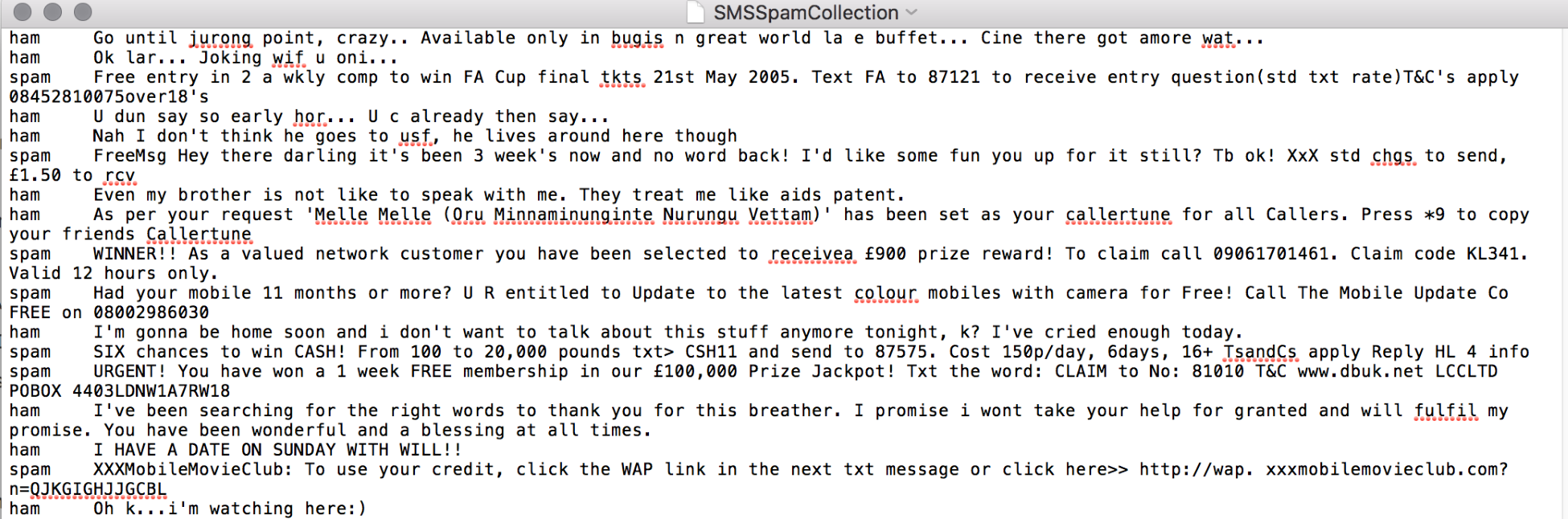

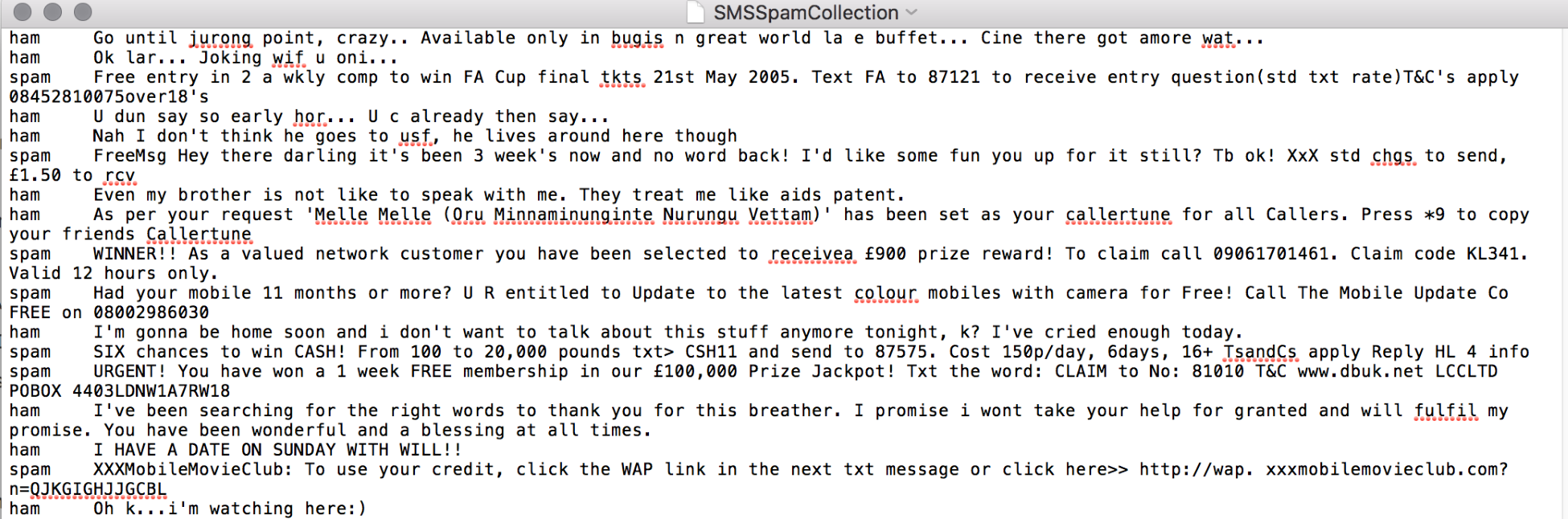

dataframe = pd.read_csv('SMSSpamCollectionDataSet', delimiter='\t',header=None)

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ mkdir css

$ cd css

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Select System info from the Administration panel."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: If you have questions about any aspect of this book, mention the book title in the subject of your message and email us at customercare@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packt.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packt.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packt.com.

The goal of this chapter is to introduce cybersecurity professionals to the basics of machine learning. We introduce the overall architecture for running machine learning modules and go through in great detail the different subtopics in the machine learning landscape.

There are many books on machine learning that deal with practical use cases, but very few address the cybersecurity and the different stages of the threat life cycle. This book is aimed at cybersecurity professionals who are looking to detect threats by applying machine learning and predictive analytics.

In this chapter, we go through the basics of machine learning. The primary areas that we cover are as follows:

Machine learning is the branch of science that enables computers to learn, to adapt, to extrapolate patterns, and communicate with each other without explicitly being programmed to do so. The term dates back 1959 when it was first coined by Arthur Samuel at the IBM Artificial Intelligence Labs. machine learning had its foundation in statistics and now overlaps significantly with data mining and knowledge discovery. In the following chapters we will go through a lot of these concepts using cybersecurity as the back drop.

In the 1980s, machine learning gained much more prominence with the success of artificial neural networks (ANNs). Machine learning became glorified in the 1990s, when researchers started using it to day-to-day life problems. In the early 2000s, the internet and digitization poured fuel on this fire, and over the years companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Netflix started leveraging machine learning to improve human-computer interactions even further. Voice recognition and face recognition systems have become our go-to technologies. More recently, artificially intelligent home automation products, self-driving cars, and robot butlers have sealed the deal.

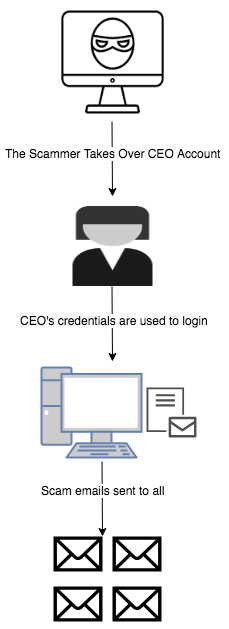

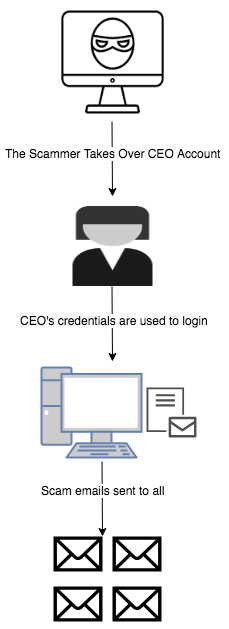

The field of cybersecurity during this same period, however, saw several massive cyber attacks and data breaches. These are regular attacks as well as state-sponsored attacks. Cyber attacks have become so big that criminals these days are not content with regular impersonations and account take-overs, they target massive industrial security vulnerabilities and try to achieve maximum return of investment (ROI) from a single attack. Several Fortune 500 companies have fallen prey to sophisticated cyber attacks, spear fishing attacks, zero day vulnerabilities, and so on. Attacks on internet of things (IoT) devices and the cloud have gained momentum. These cyber breaches seemed to outsmart human security operations center (SOC) analysts and machine learning methods are needed to complement human effort. More and more threat detection systems are now dependent on these advanced intelligent techniques, and are slowly moving away from the signature-based detectors typically used in security information and event management (SIEM).

The following table presents some of the problems that machine learning solves:

|

Use case Domain

|

Description

|

| Face recognition | Face recognition systems can identify people from digital images by recognizing facial features. These are similar to biometrics and extensively use security systems like the use of face recognition technology to unlock phones. Such systems use three-dimensional recognition and skin texture analysis to verify faces. |

| Fake news detection | Fake news is rampant specially after the 2016 United States presidential election. To stop such yellow journalism and the turmoil created by fake news, detectors were introduced to separate fake news from legitimate news. The detectors use semantic and stylistic patterns of the text in the article, the source of article, and so on, to segregate fake from legit. |

| Sentiment analysis | Understanding the overall positivity or negativity of a document is important as opinion is an influential parameter while making a decision. Sentiment analysis systems perform opinion mining to understand the mood and attitude of the customer. |

| Recommender systems | These are systems that are able to assess the choice of a customer based on the personal history of previous choices made by the customer. This is another determining factor that influences such systems choices made by other similar customers. Such recommender systems are extremely popular and heavily used by industries to sell movies, products, insurances, and so on. Recommender systems in a way decide the go-to-market strategies for the company based on cumulative like or dislike. |

| Fraud detection systems | Fraud detection systems are created for risk mitigation and safe fraud according to customer interest. Such systems detect outliers in transactions and raise flags by measuring anomaly coefficients. |

| Language translators | Language translators are intelligent systems that are able to translate not just word to word but whole paragraphs at a time. Natural language translators use contextual information from multilingual documents and are able to make these translations. |

| Chatbots | Intelligent chatbots are systems that enhance customer experience by providing auto responses when human customer service agents cannot respond. However, their activity is not just limited to being a virtual assistant. They have sentiment analysis capabilities and are also able to make recommendations. |

Legacy-based threat detection systems used heuristics and static signatures on a large amount of data logs to detect threat and anomalies. However, this meant that analysts needed to be aware of how normal data logs should look. The process included data being ingested and processed through the traditional extraction, transformation, and load (ETL) phase. The transformed data is read by machines and analyzed by analysts who create signatures. The signatures are then evaluated by passing more data. An error in evaluation meant rewriting the rules. Signature-based threat detection techniques, though well understood, are not robust, since signatures need to be created on-the-go for larger volumes of data.

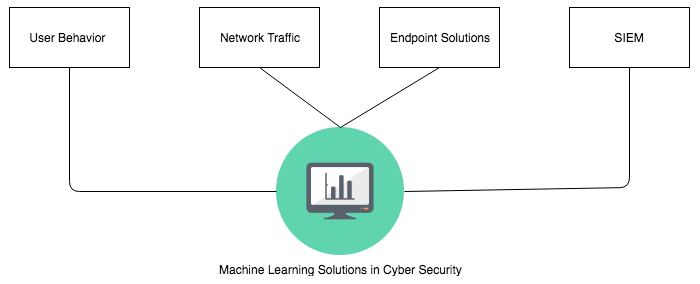

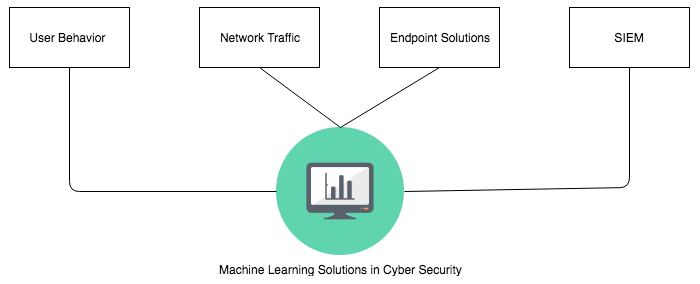

Today signature-based systems are being gradually replaced by intelligent cybersecurity agents. Machine learning products are aggressive in identifying new malware, zero day attacks, and advanced persistent threats. Insight from the immense amount of log data is being aggregated by log correlation methods. Endpoint solutions have been super active in identifying peripheral attacks. New machine learning driven cybersecurity products have been proactive in strengthening container systems like virtual machines. The following diagram gives a brief overview of some machine learning solutions in cybersecurity:

In general, machine learning products are created to predict attacks before they occur, but given the sophisticated nature of these attacks, preventive measures often fail. In such cases, machine learning often helps to remediate in other ways, like recognizing the attack at its initial stages and preventing it from spreading across the entire organization.

Many cybersecurity companies are relying on advanced analytics, such as user behavior analytics and predictive analytics, to identify advanced persistent threats early on in the threat life cycle. These methods have been successful in preventing data leakage of personally identifiable information (PII) and insider threats. But prescriptive analytics is another advanced machine learning solution worth mentioning in the cybersecurity perspective. Unlike predictive analytics, which predicts threat by comparing current threat logs with historic threat logs, prescriptive analytics is a more reactive process. Prescriptive analytics deals with situations where a cyber attack is already in play. It analyzes data at this stage to suggest what reactive measure could best fit the situation to keep the loss of information to a minimum.

Machine learning, however, has a down side in cybersecurity. Since alerts generated need to be tested by human SOC analysts, generating too many false alerts could cause alert fatigue. To prevent this issue of false positives, cybersecurity solutions also get insights from SIEM signals. The signals from SIEM systems are compared with the advanced analytics signals so that the system does not produce duplicate signals. Thus machine learning solutions in the field of cybersecurity products learn from the environment to keep false signals to a minimum.

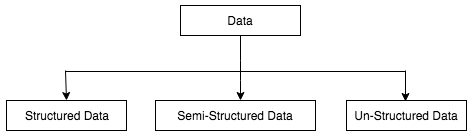

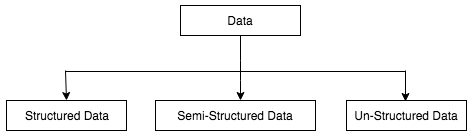

Data is the fuel that drives the machine learning engine. Data, when fed to machine learning systems, helps in detecting patterns and mining data. This data can be in any form and comes in frequency from any source.

Depending on the source of data and the use case in hand, data can either be structured data, that is, it can be easily mapped to identifiable column headers, or it can be unstructured, that is, it cannot be mapped to any identifiable data model. A mix of unstructured and structured data is called semi-structured data. We will discuss later in the chapter the differing learning approaches to handling these two type of data:

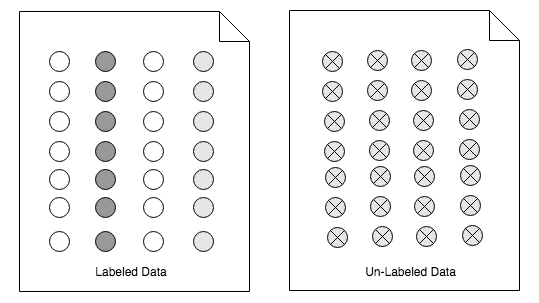

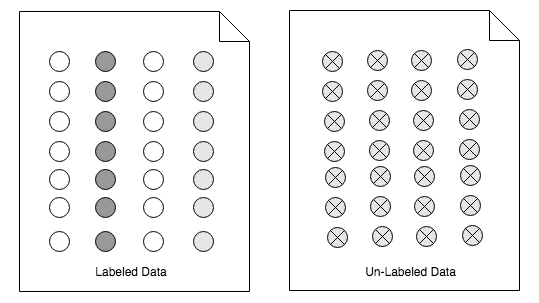

Data can also be categorized into labelled and unlabelled data. Data that has been manually tagged with headers and meaning is called labelled. Data that has not been tagged is called unlabelled data. Both labelled and unlabelled data are fed to the preceding machine learning phases. In the training phase, the ratio of labelled to unlabelled is 60-40 and 40-60 in the testing phase. Unlabelled data is transformed to labelled data in the testing phase, as shown in the following diagram:

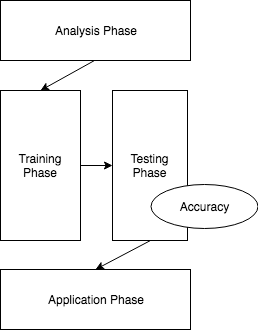

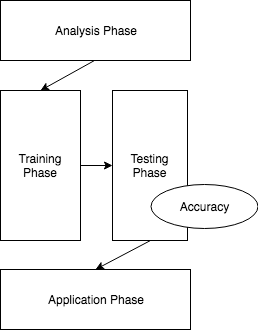

The general approach to solving machine learning consists of a series of phases. These phases are consistent no matter he source of data. That is, be it structured or unstructured, the stages required to tackle any kind of data are as shown in the following diagram:

We will discuss each of the phases in detail as follows:

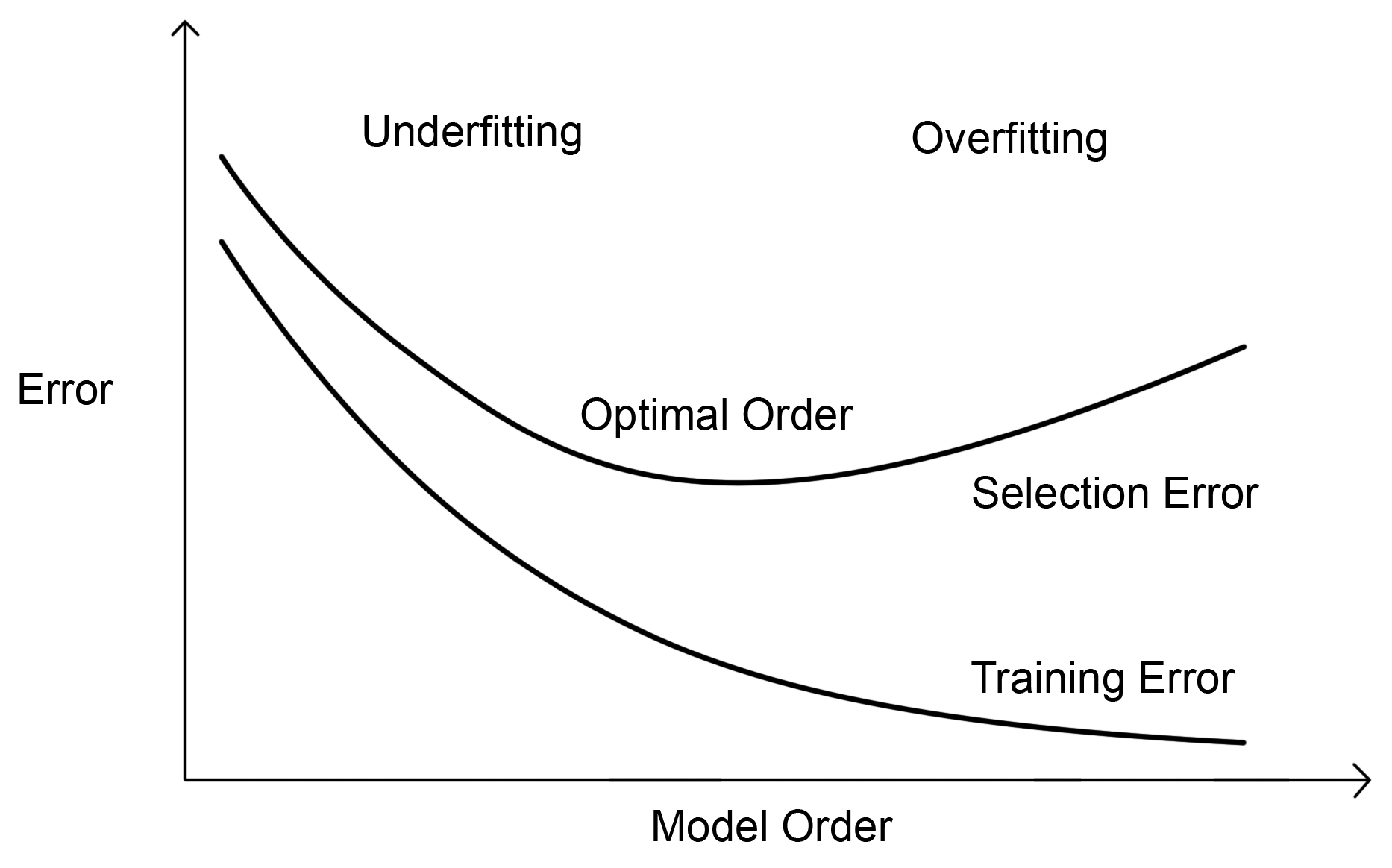

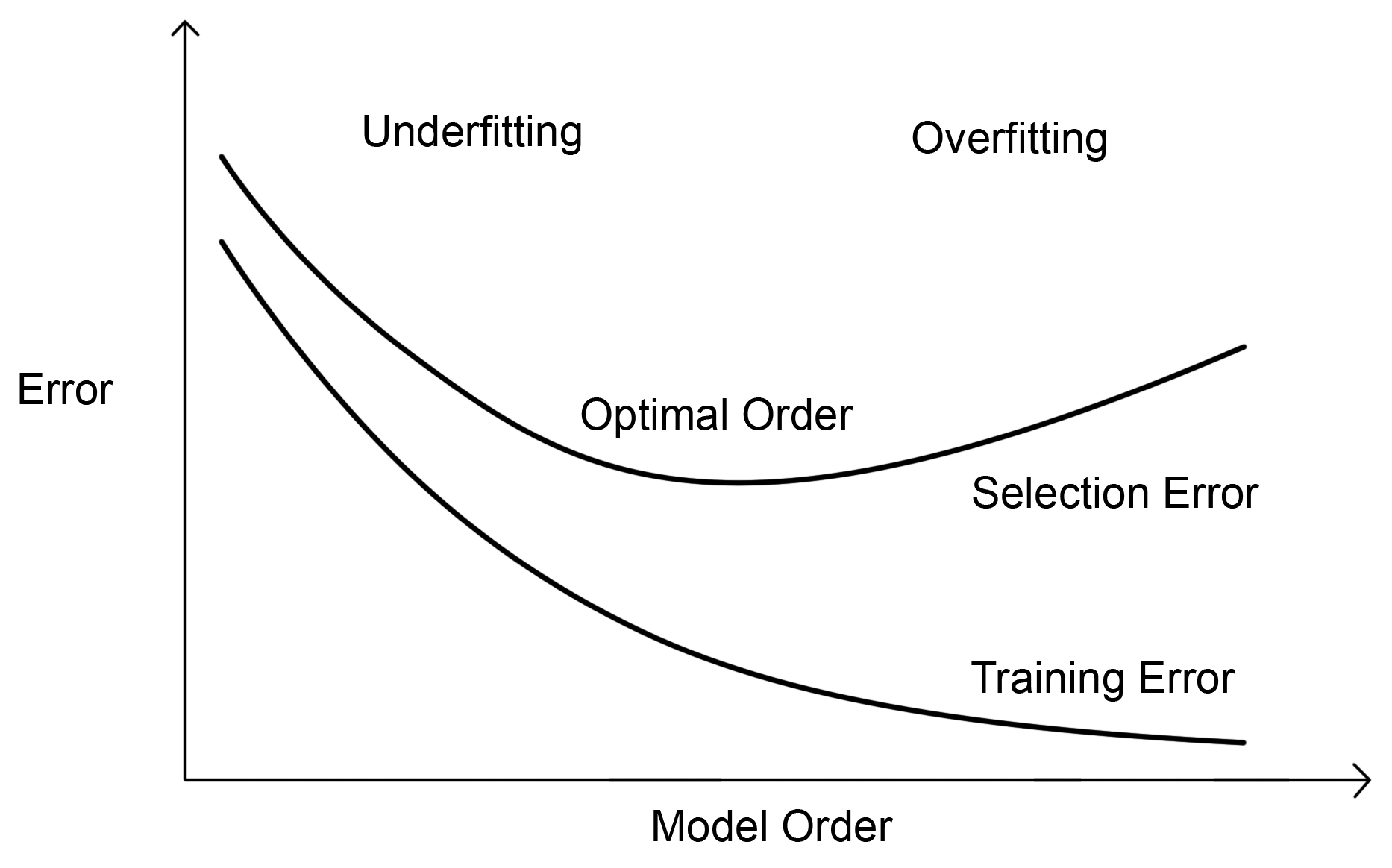

In the training phase, a machine learning model may or may not generalize perfectly. This is due to the inconsistencies that we need to be aware of.

Overfitting is the phenomenon in which the system is too fitted to the training data. The system produces a negative bias when treated with new data. In other words, the models perform badly. Often this is because we feed only labelled data to our model. Hence we need both labelled and unlabelled data to train a machine learning system.

The following graph shows that to prevent any model errors we need to select data in the optimal order:

Underfitting is another scenario where model performs badly. This is a phenomenon where the performance of the model is affected because the model is not well trained. Such systems have trouble in generalizing new data.

For ideal model performance, both overfitting and underfitting can be prevented by performing some common machine learning procedures, like cross validation of the data, data pruning, and regularization of the data. We will go through these in much more detail in the following chapters after we get more acquainted with machine learning models.

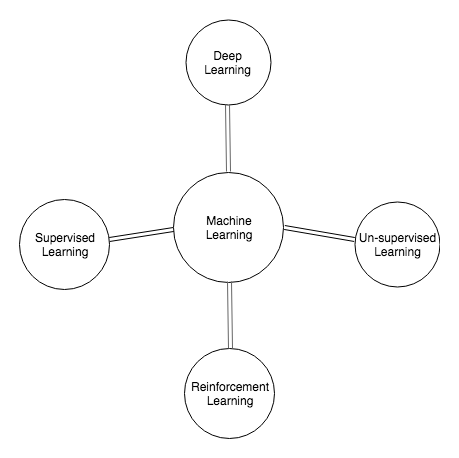

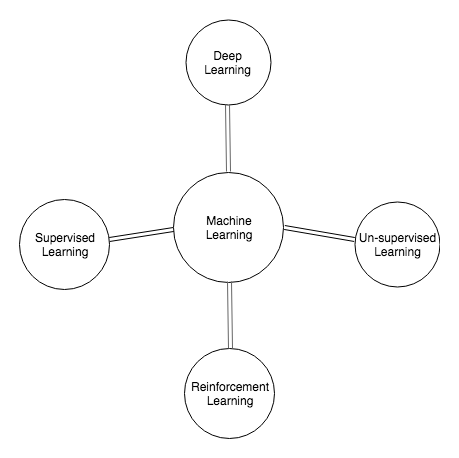

In this section, we will be discussing the different types of machine learning system and the most commonly used algorithms, with special emphasis on the ones that are more popular in the field of cybersecurity. The following diagram shows the different types of learning involved in machine learning:

Machine learning systems can be broadly categorized into two types: supervised approaches and unsupervised approaches, based on the types of learning they provide.

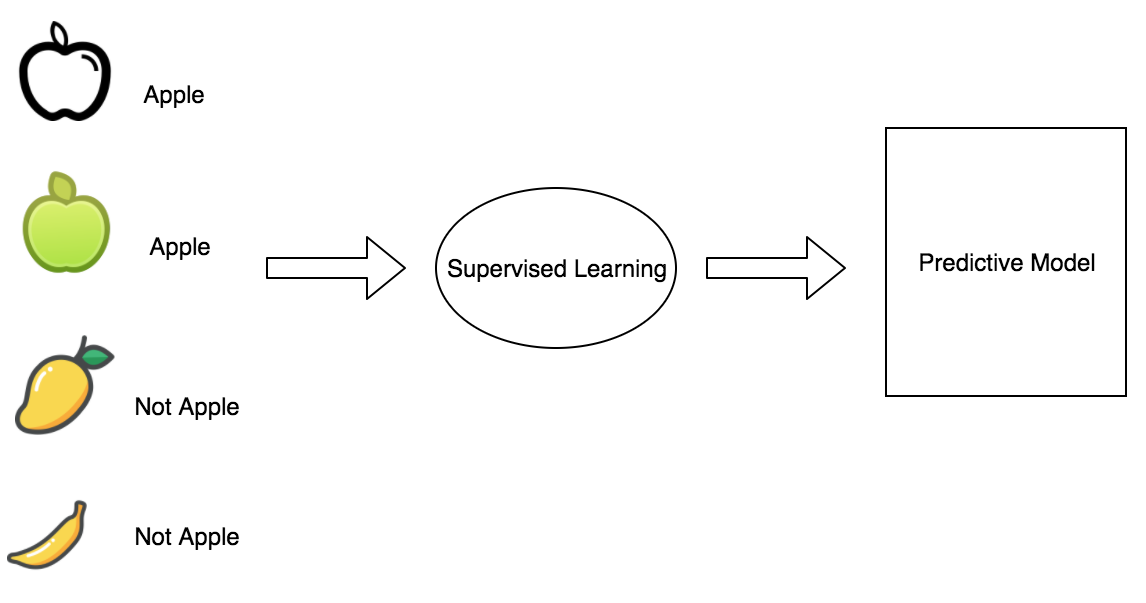

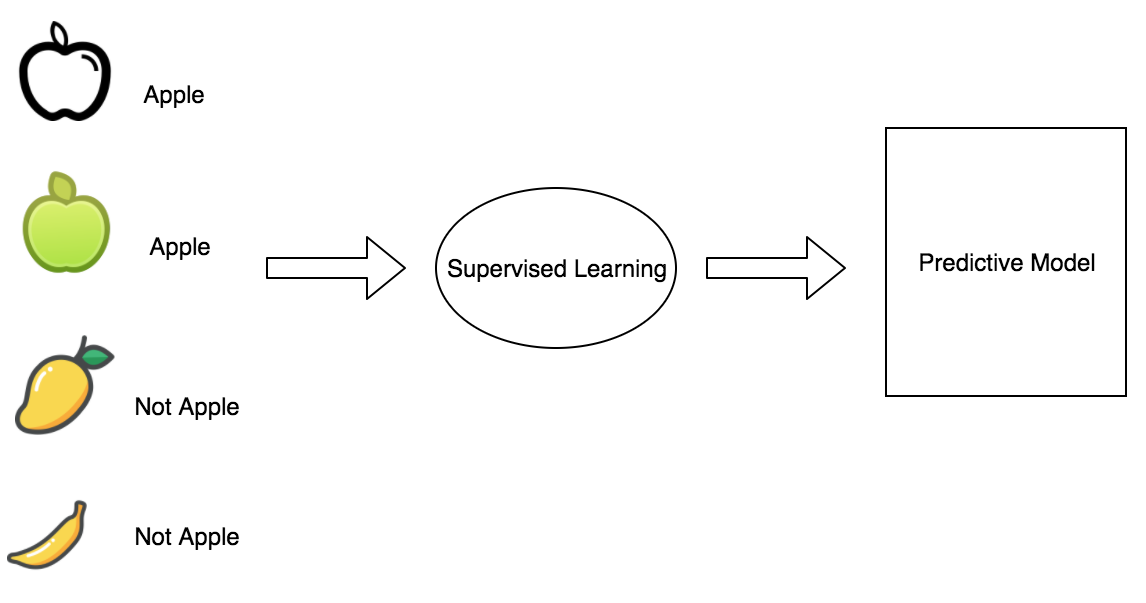

Supervised learning is where a known dataset is used to classify or predict with data in hand. Supervised learning methods learn from labelled data and then use the insight to make decisions on the testing data.

Supervised learning has several subcategories of learning, for example:

Some popular examples of supervised learning are:

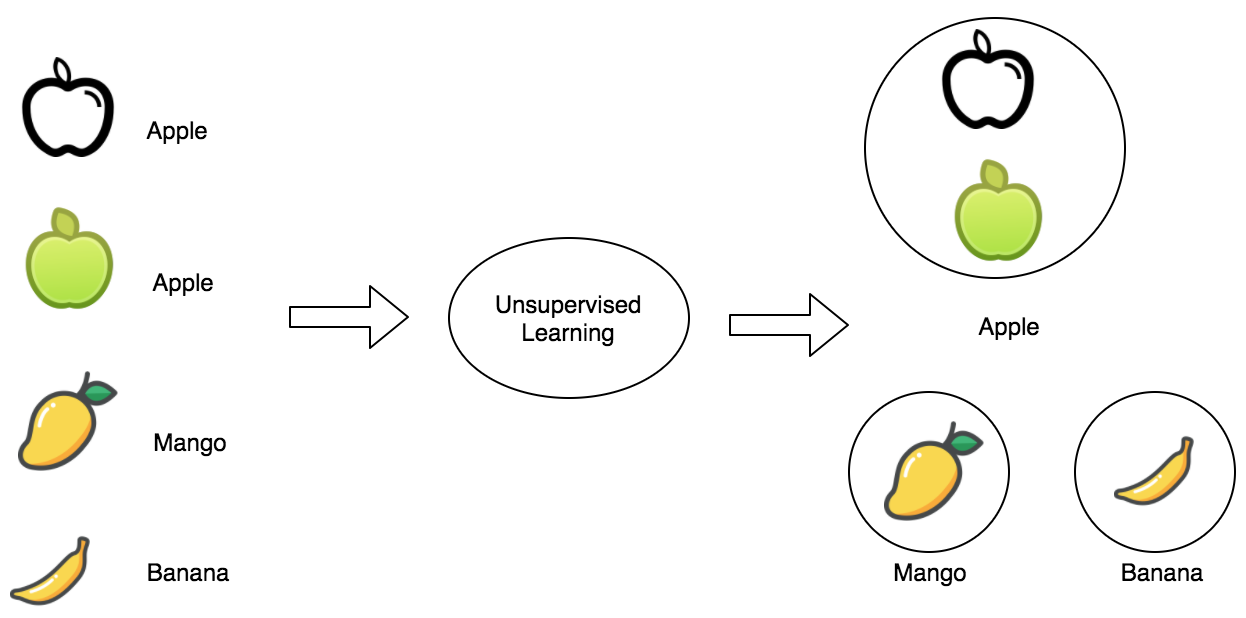

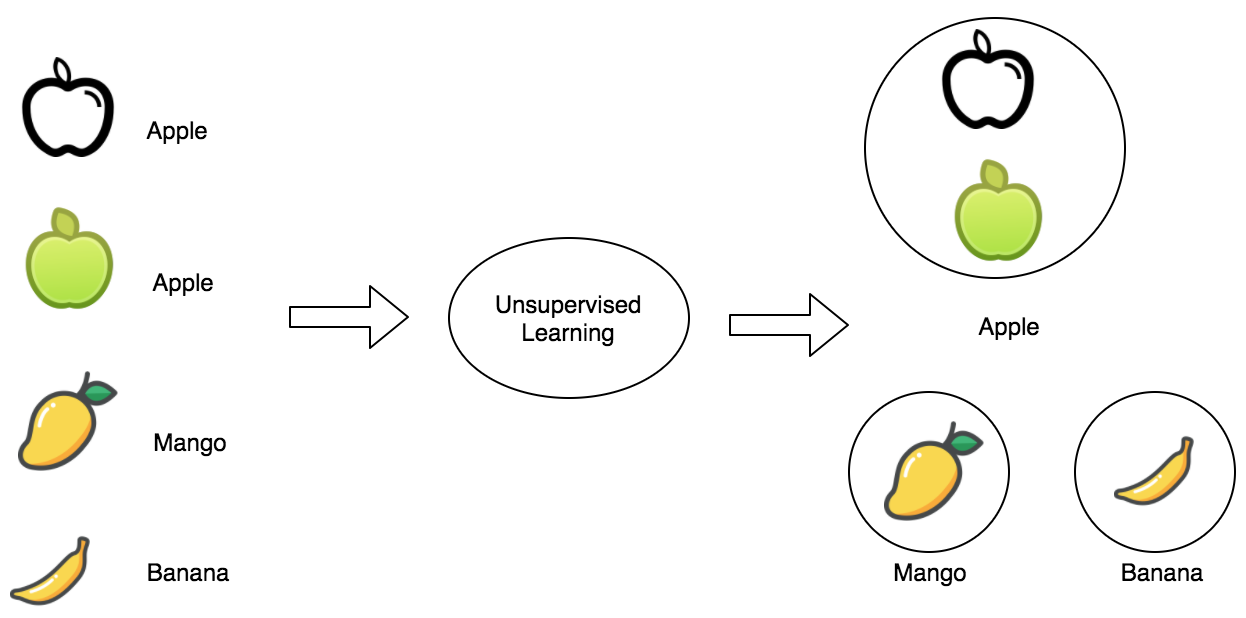

The unsupervised learning technique is where the initial data is not labelled. Insights are drawn by processing data whose structure is not known before hand. These are more complex processes since the system learns by itself without any intervention.

Some practical examples of unsupervised learning techniques are:

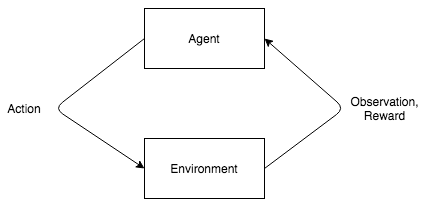

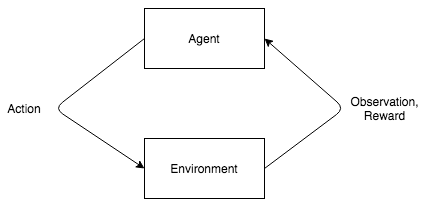

Reinforcement learning is a type of dynamic programming where the software learns from its environment to produce an output that will maximize the reward. Here the software requires no external agent but learns from the surrounding processes in the environment.

Some practical examples of reinforcement learning techniques are:

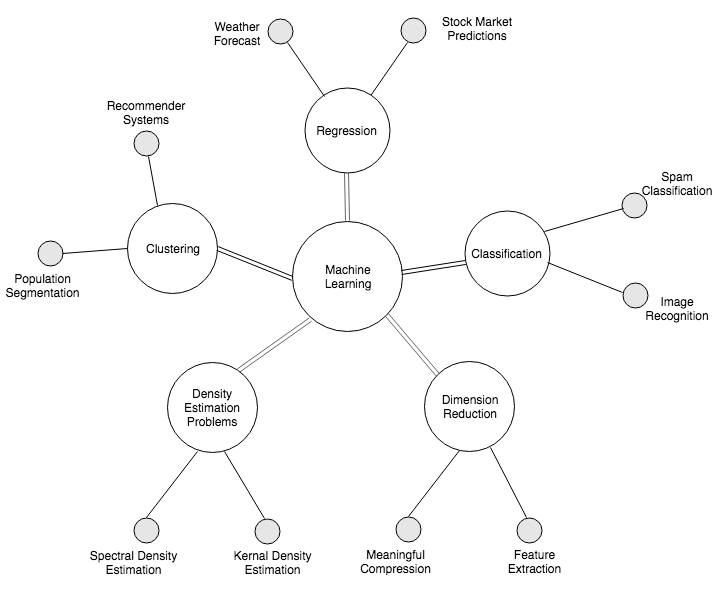

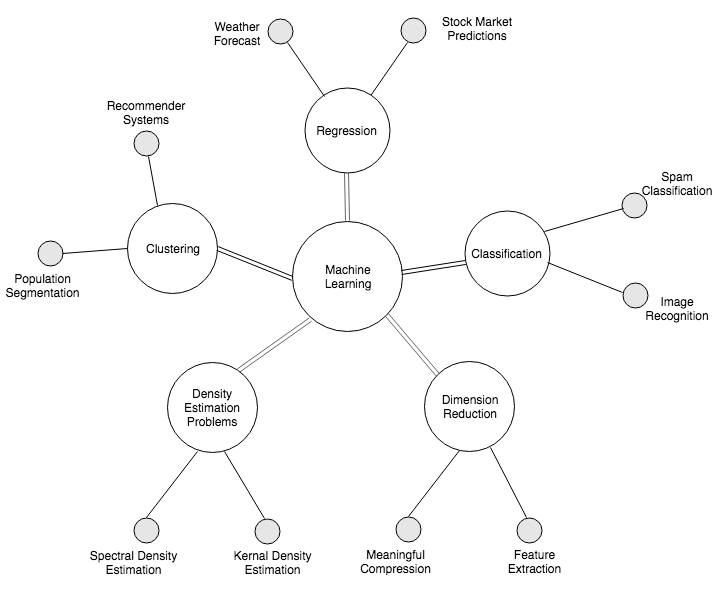

Machine learning techniques can also be categorized by the type of problem they solve, like the classification, clustering, regression, dimensionality reduction, and density estimation techniques. The following diagram briefly discusses definitions and examples of these systems:

In the next chapter, we will be delving with details and its implementation with respect to cybersecurity problems.

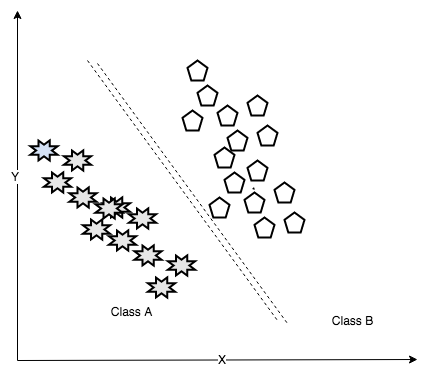

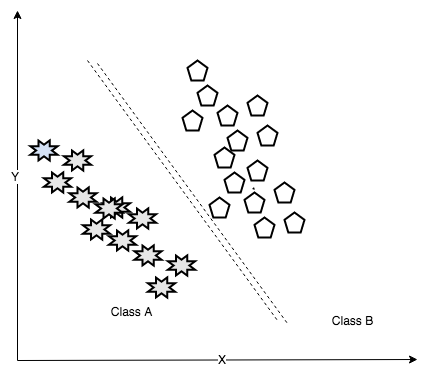

Classification is the process of dividing data into multiple classes. Unknown data is ingested and divided into categories based on characteristics or features. Classification problems are an instance of supervised learning since the training data is labelled.

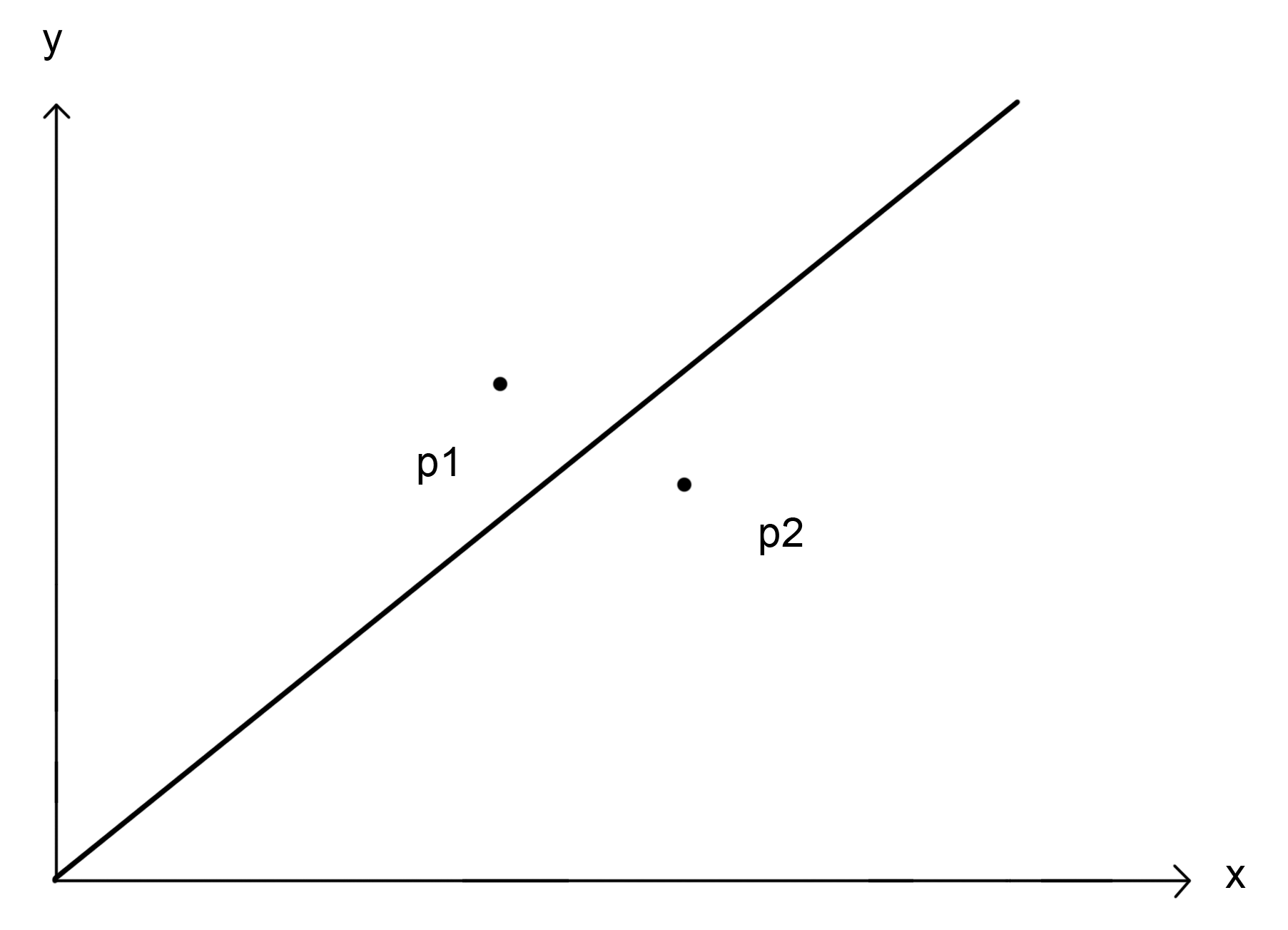

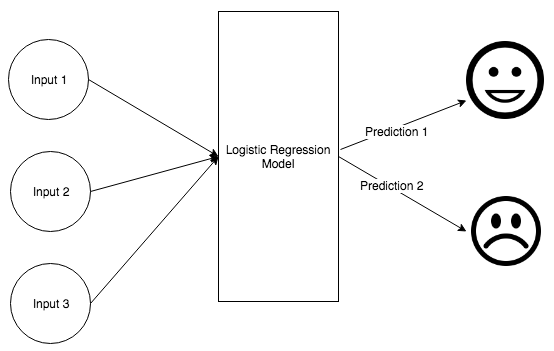

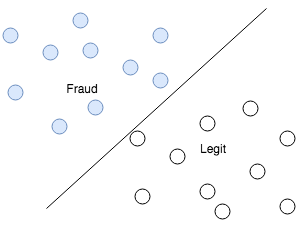

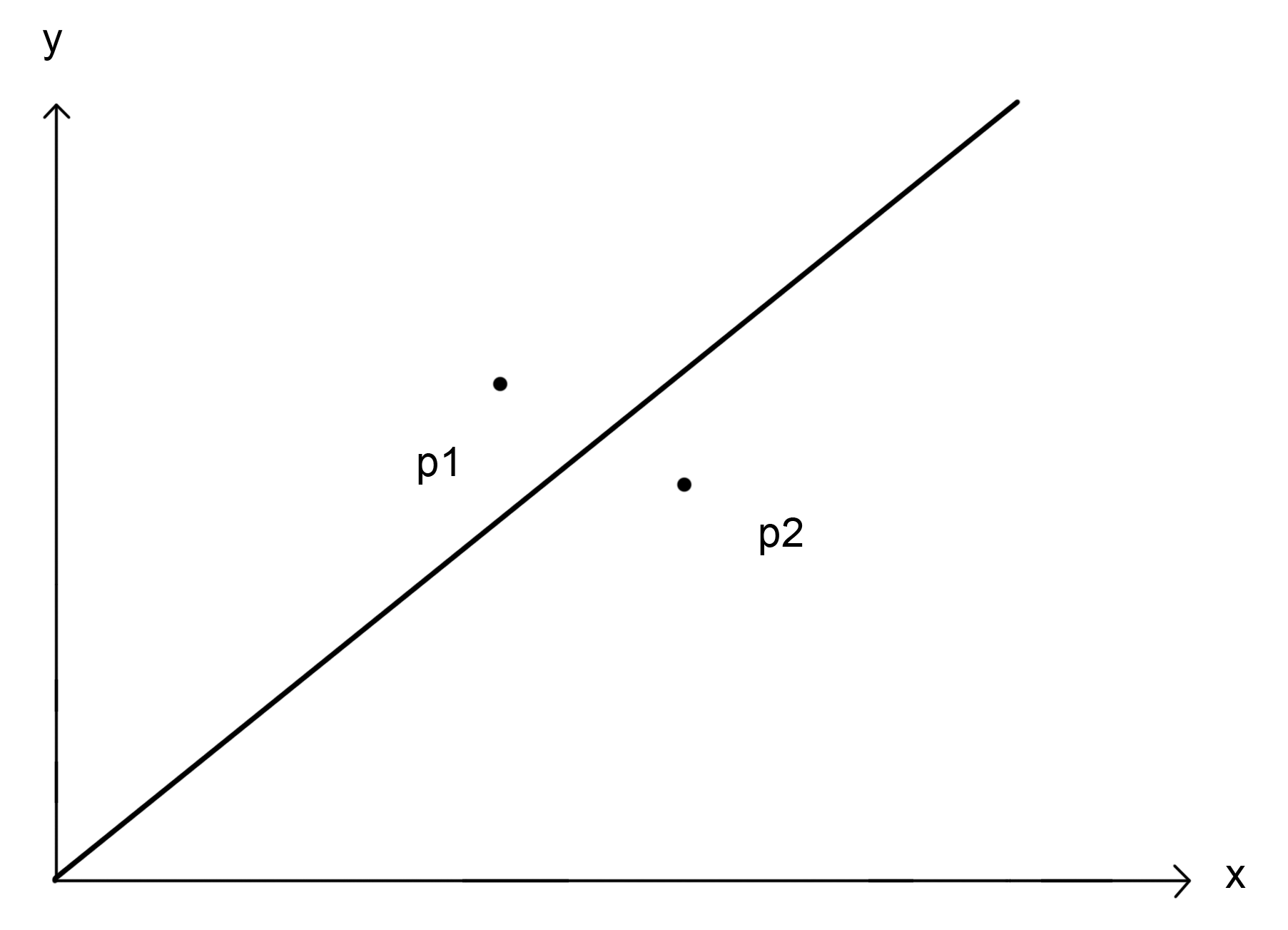

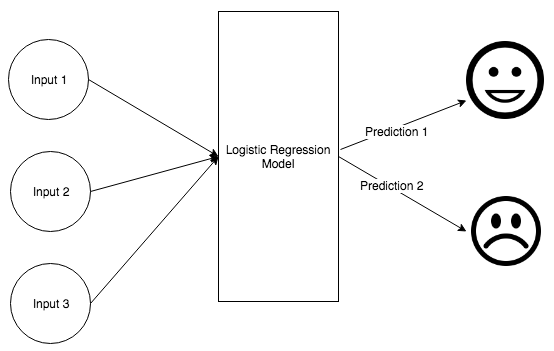

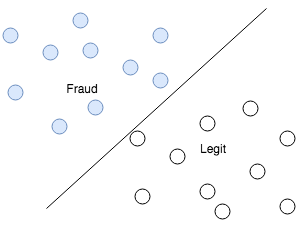

Web data classification is a classic example of this type of learning, where web contents get categorized with models to their respective type based on their textual content like news, social media, advertisements, and so on. The following diagram shows data classified into two classes:

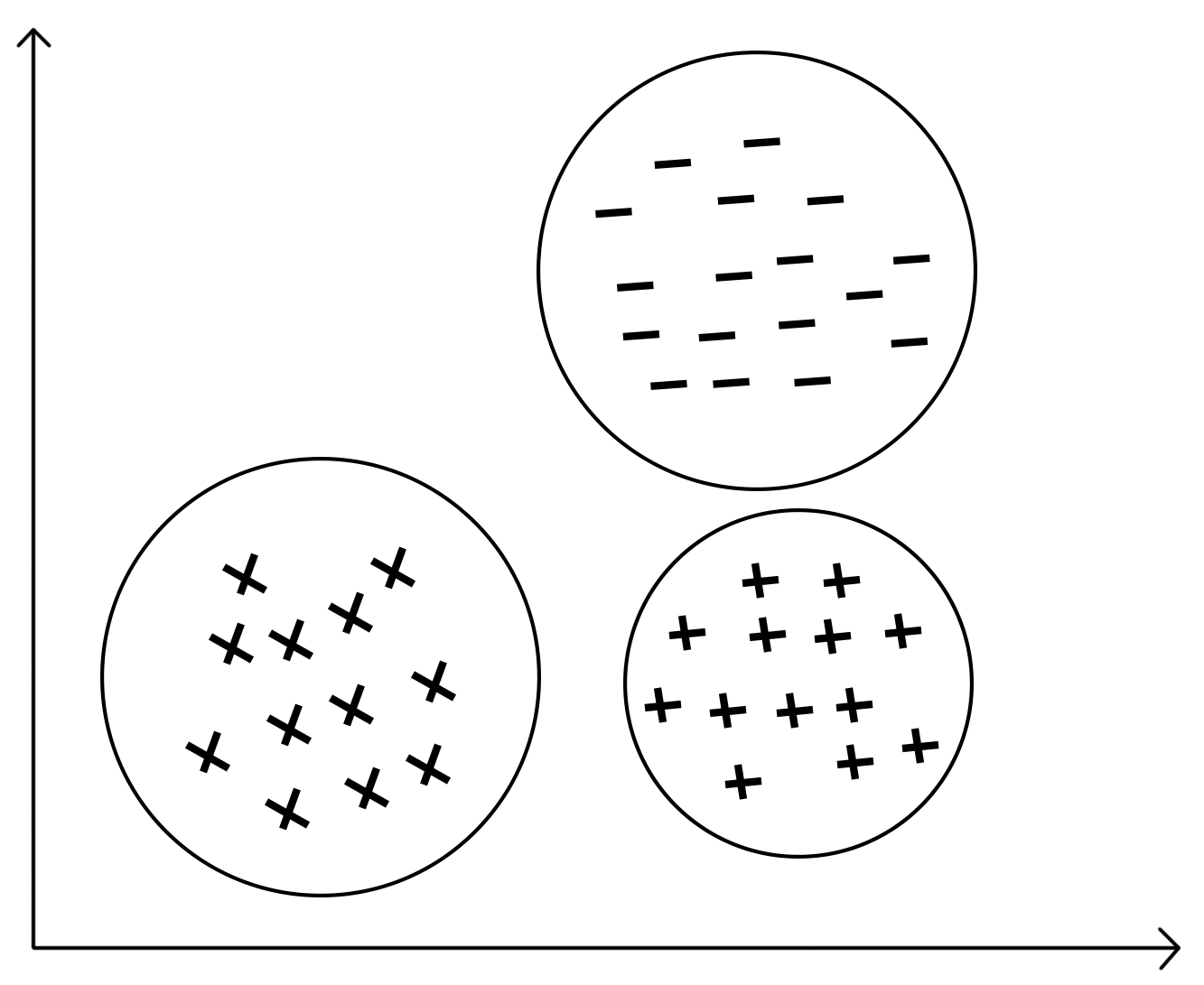

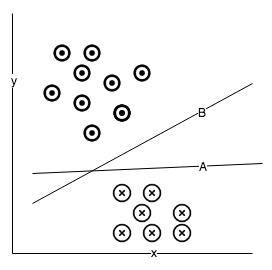

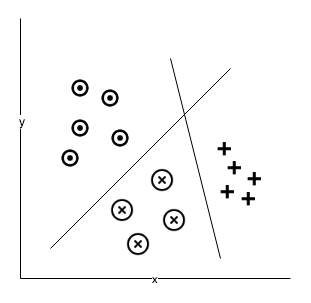

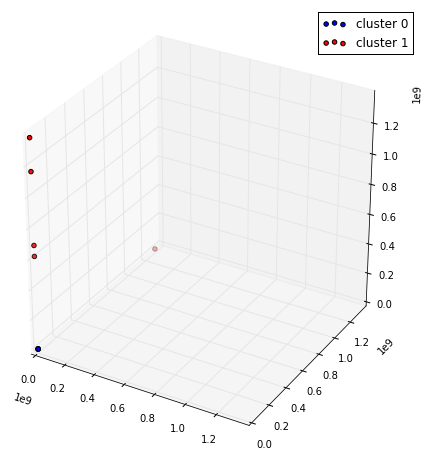

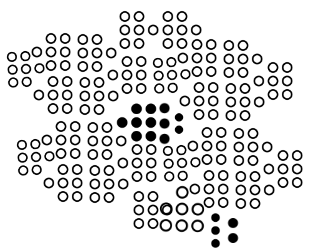

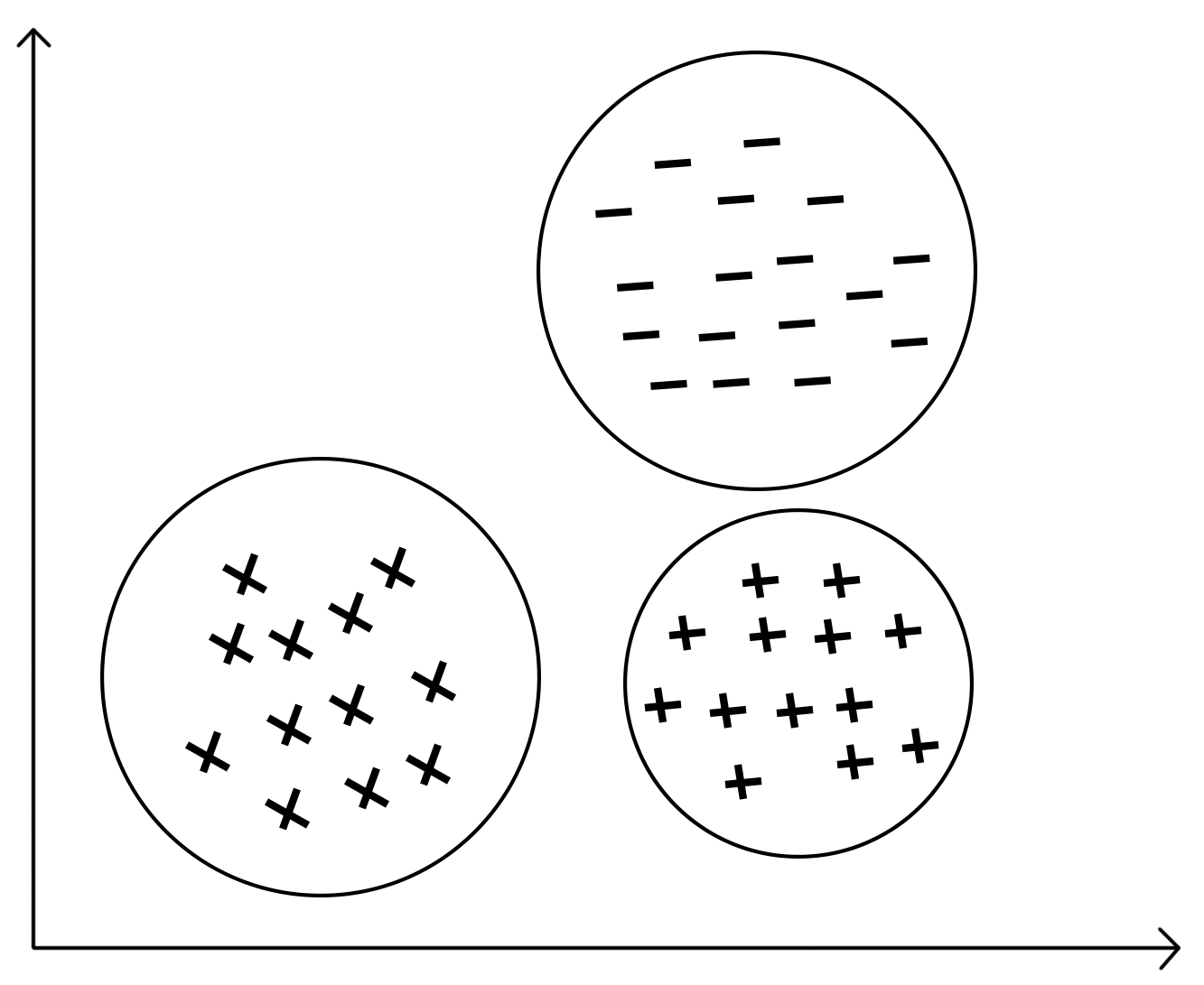

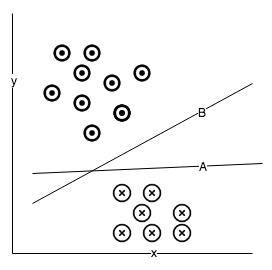

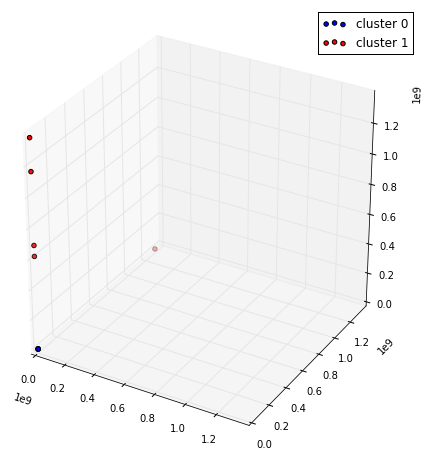

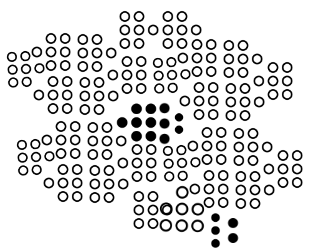

Clustering is the process of grouping data and putting similar data into the same group. Clustering techniques use a series of data parameters and go through several iterations before they can group the data. These techniques are most popular in the fields of information retrieval and pattern recognition. Clustering techniques are also popularly used in the demographic analysis of the population. The following diagram shows how similar data is grouped in clusters:

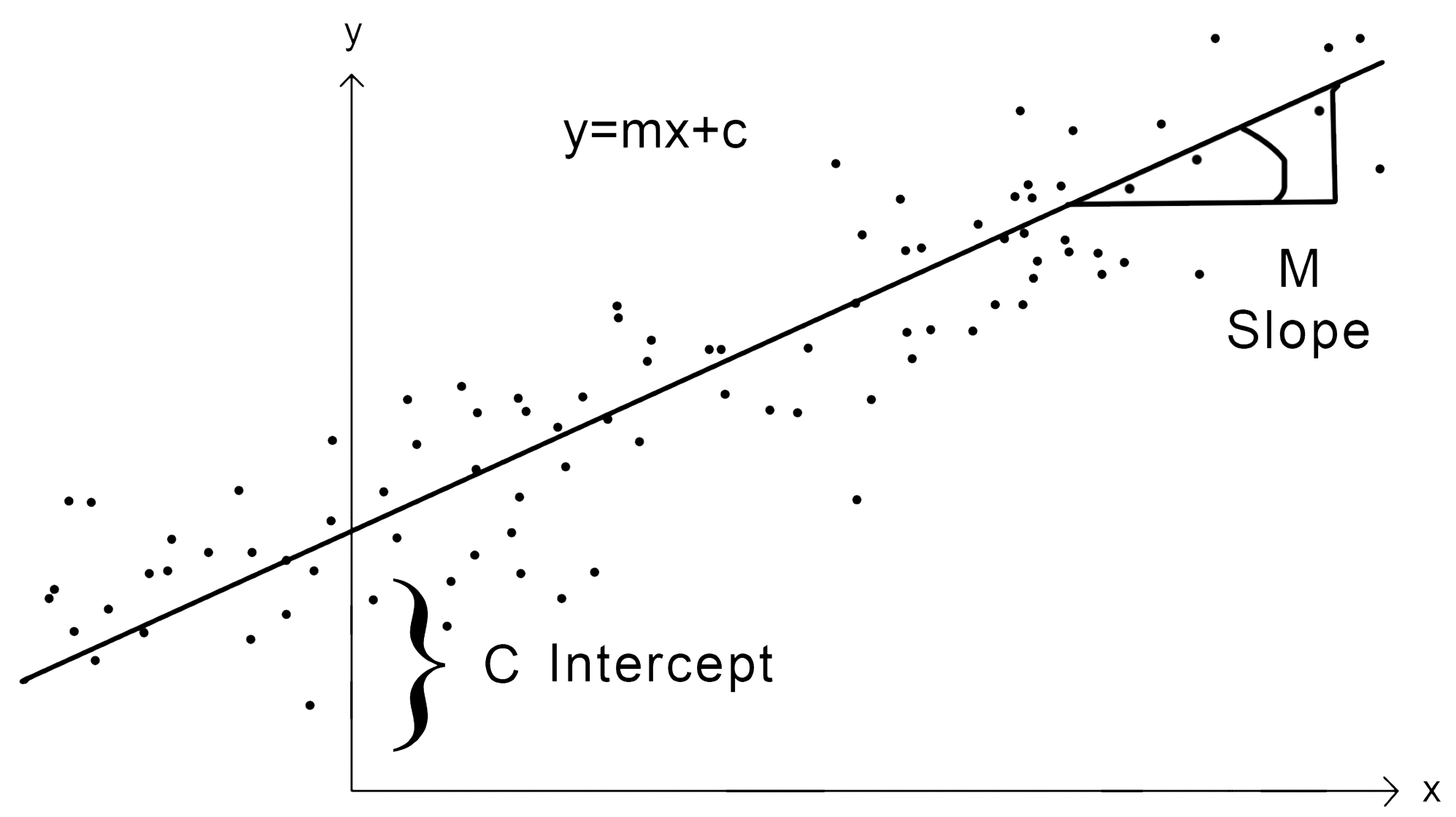

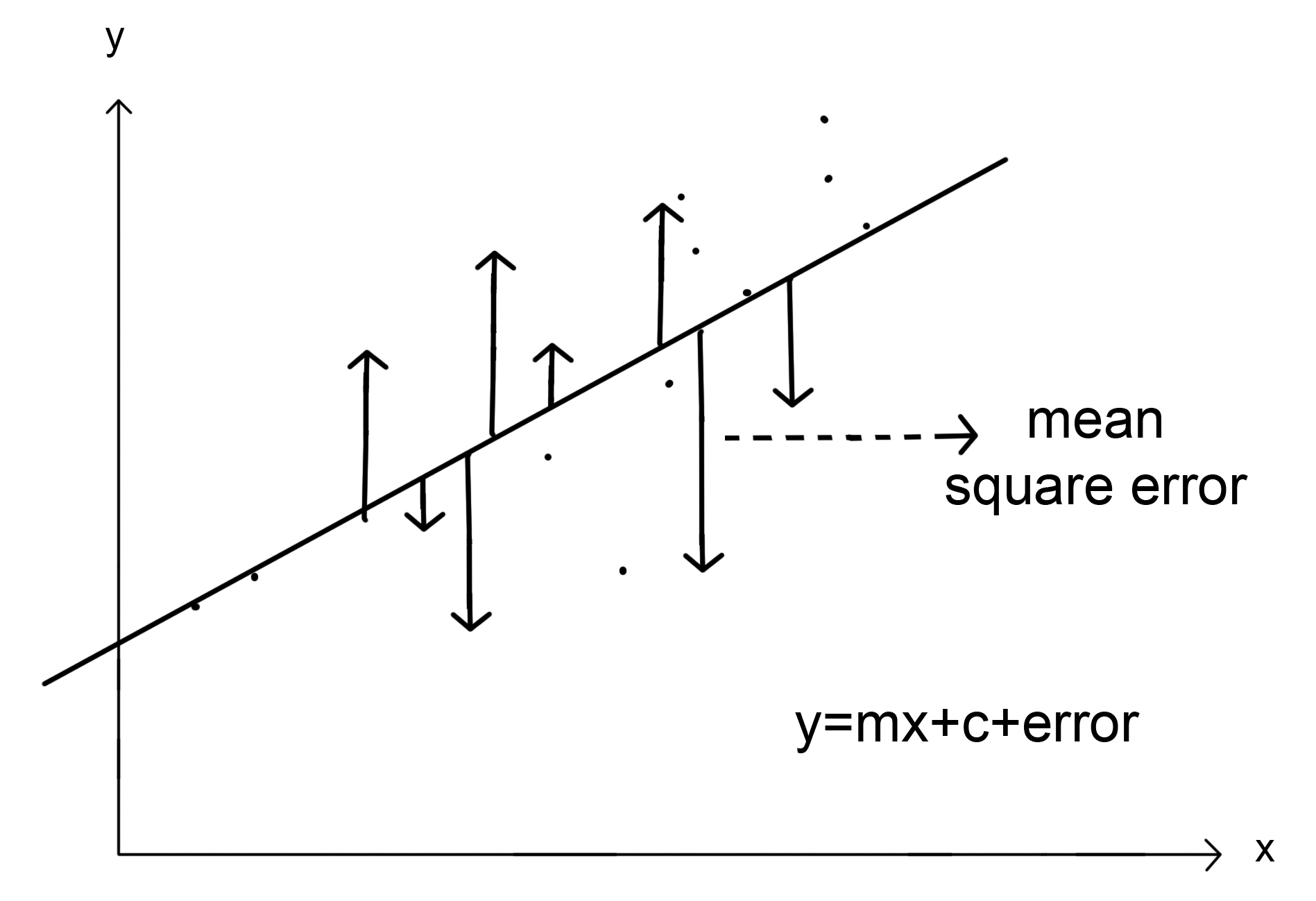

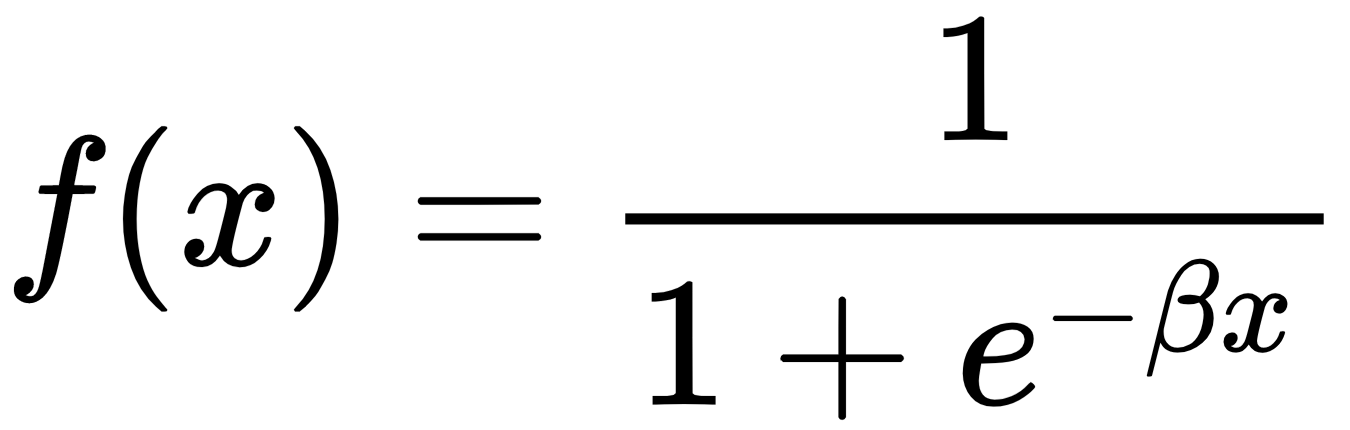

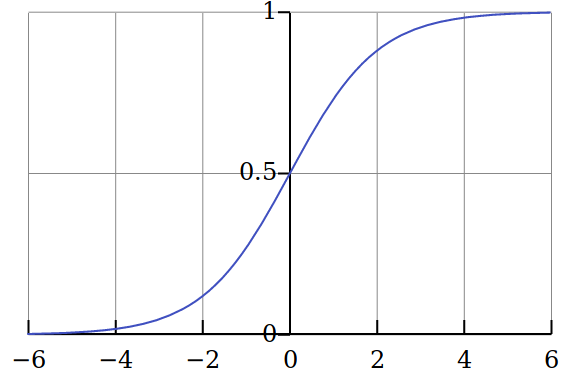

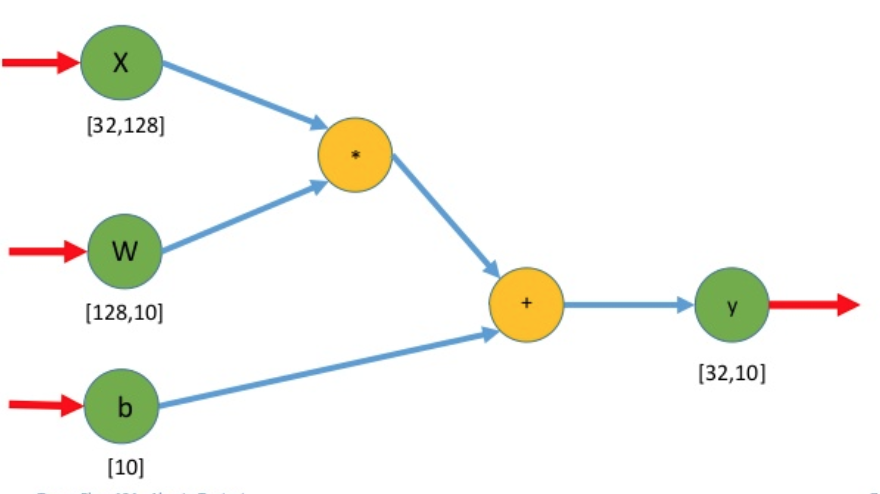

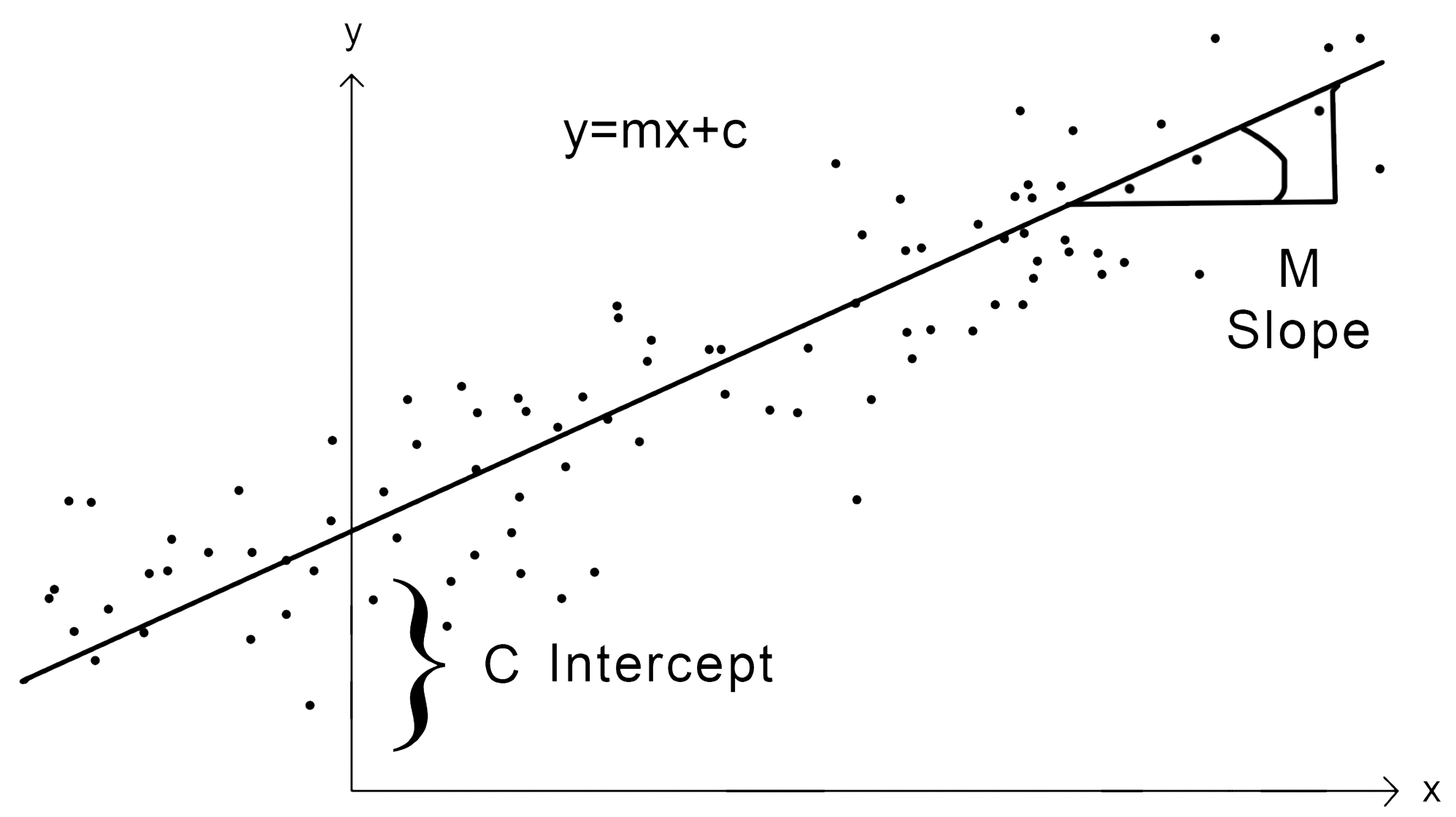

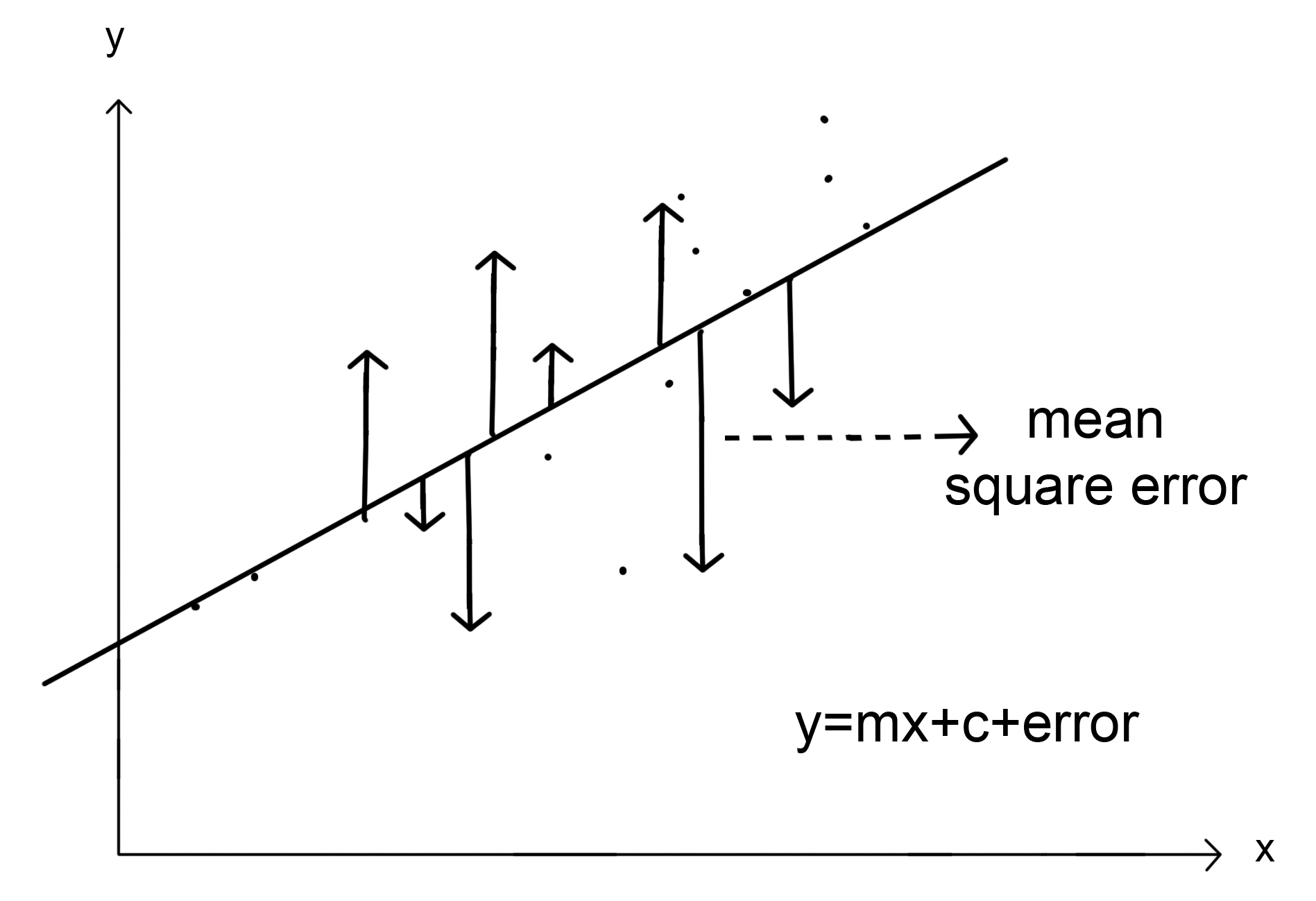

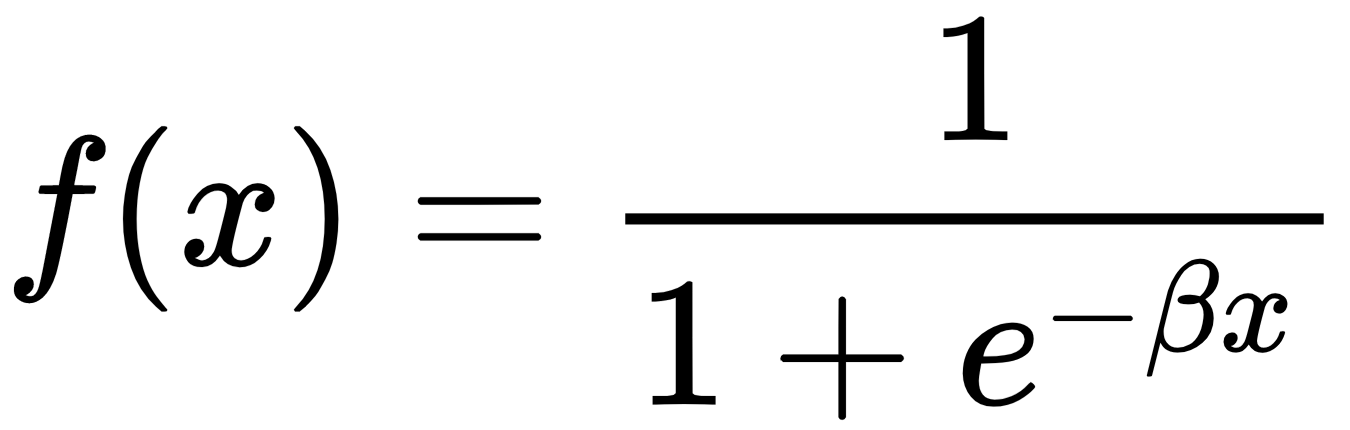

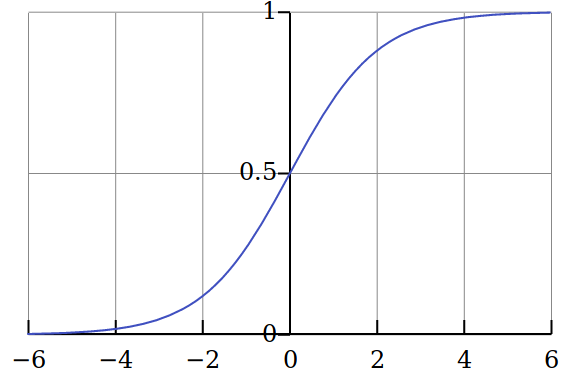

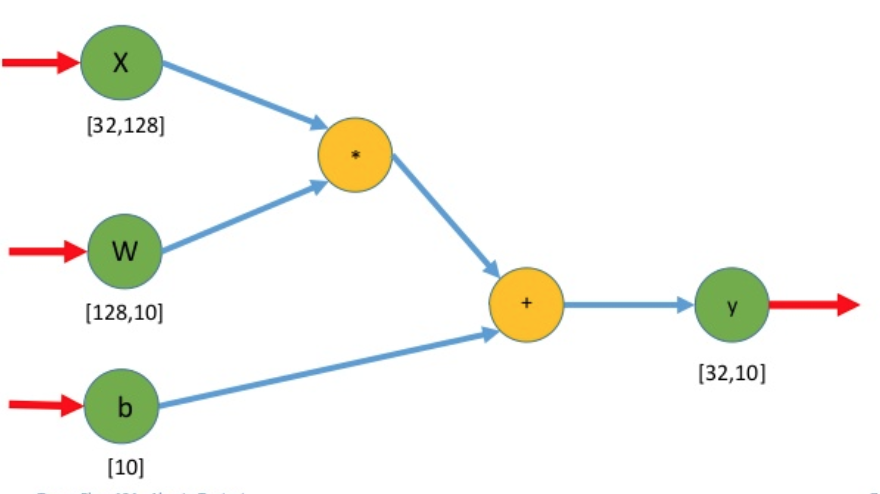

Regressions are statistical processes for analyzing data that helps with both data classification and prediction. In regression, the relationship between two variables present in the data population is estimated by analyzing multiple independent and dependent variables. Regression can be of many types like, linear regression, logistic regression, polynomial regression, lasso regression, and so on. An interesting use case with regression analysis is the fraud detection system. Regressions are also used in stock market analysis and prediction:

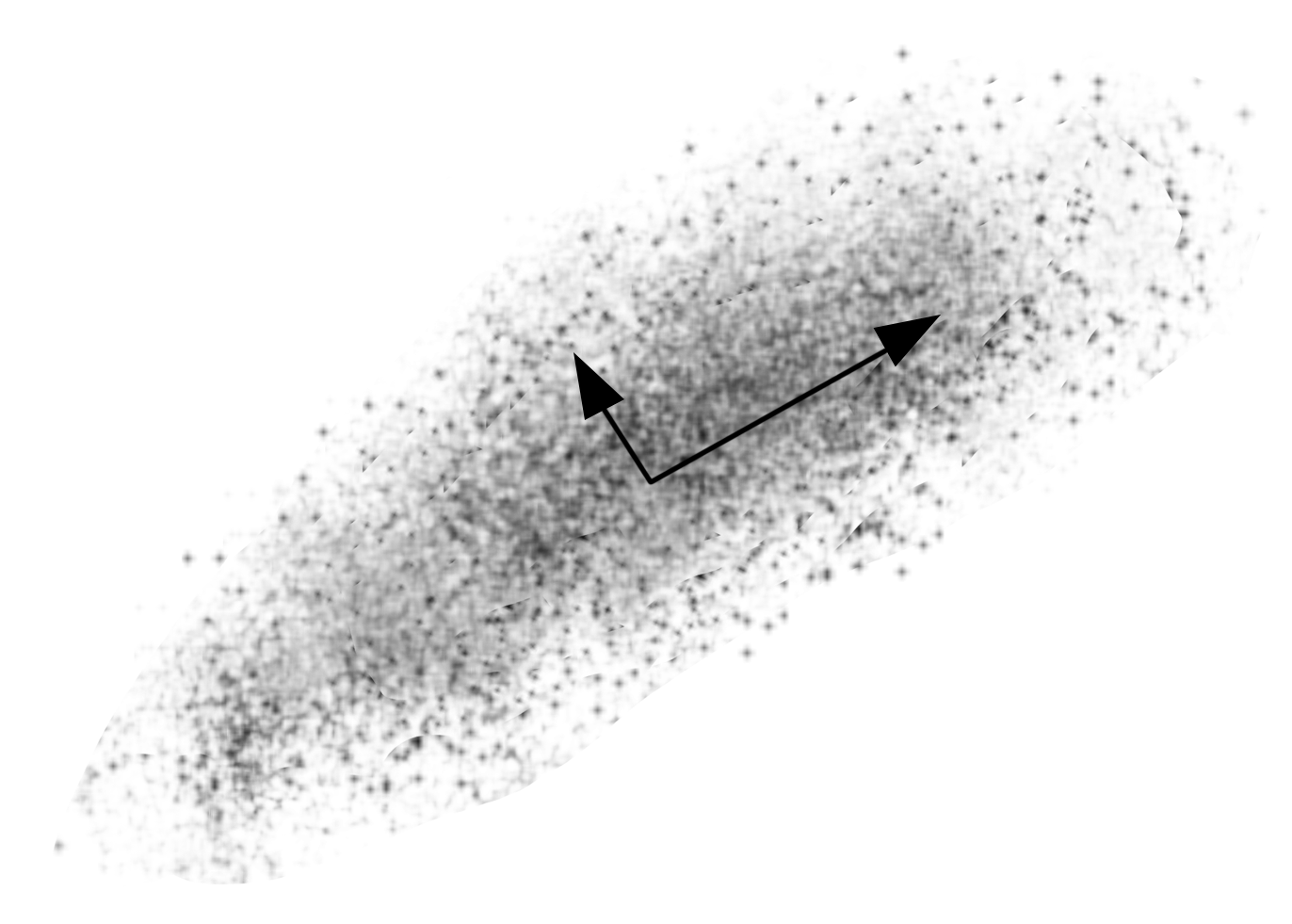

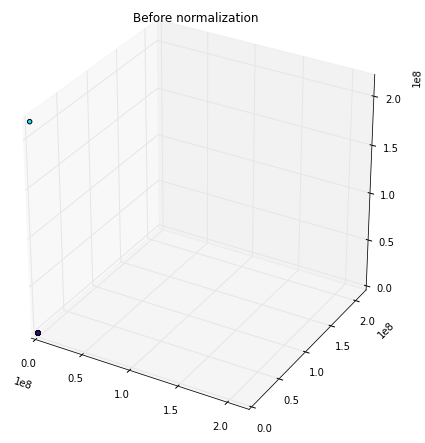

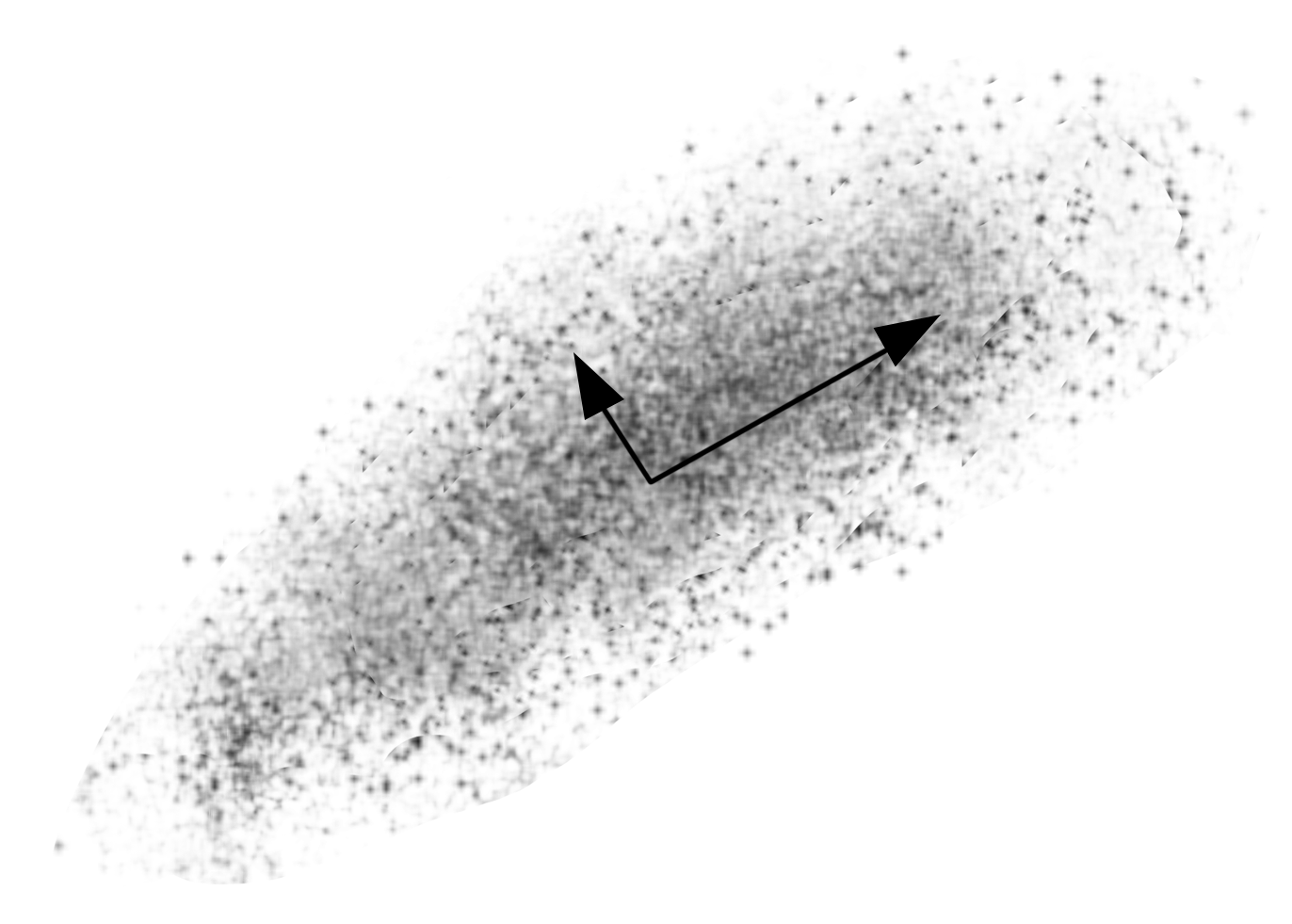

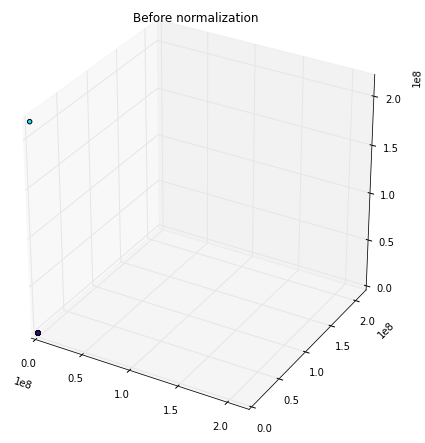

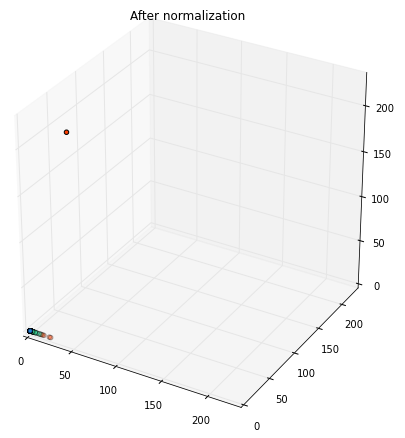

Dimensionality reduction problems are machine learning techniques where high dimensional data with multiple variables is represented with principle variables, without loosing any vital data. Dimensionality reduction techniques are often applied on network packet data to make the volume of data sizeable. These are also used in the process of feature extraction where it is impossible to model with high dimensional data. The following screenshot shows high-dimensional data with multiple variables:

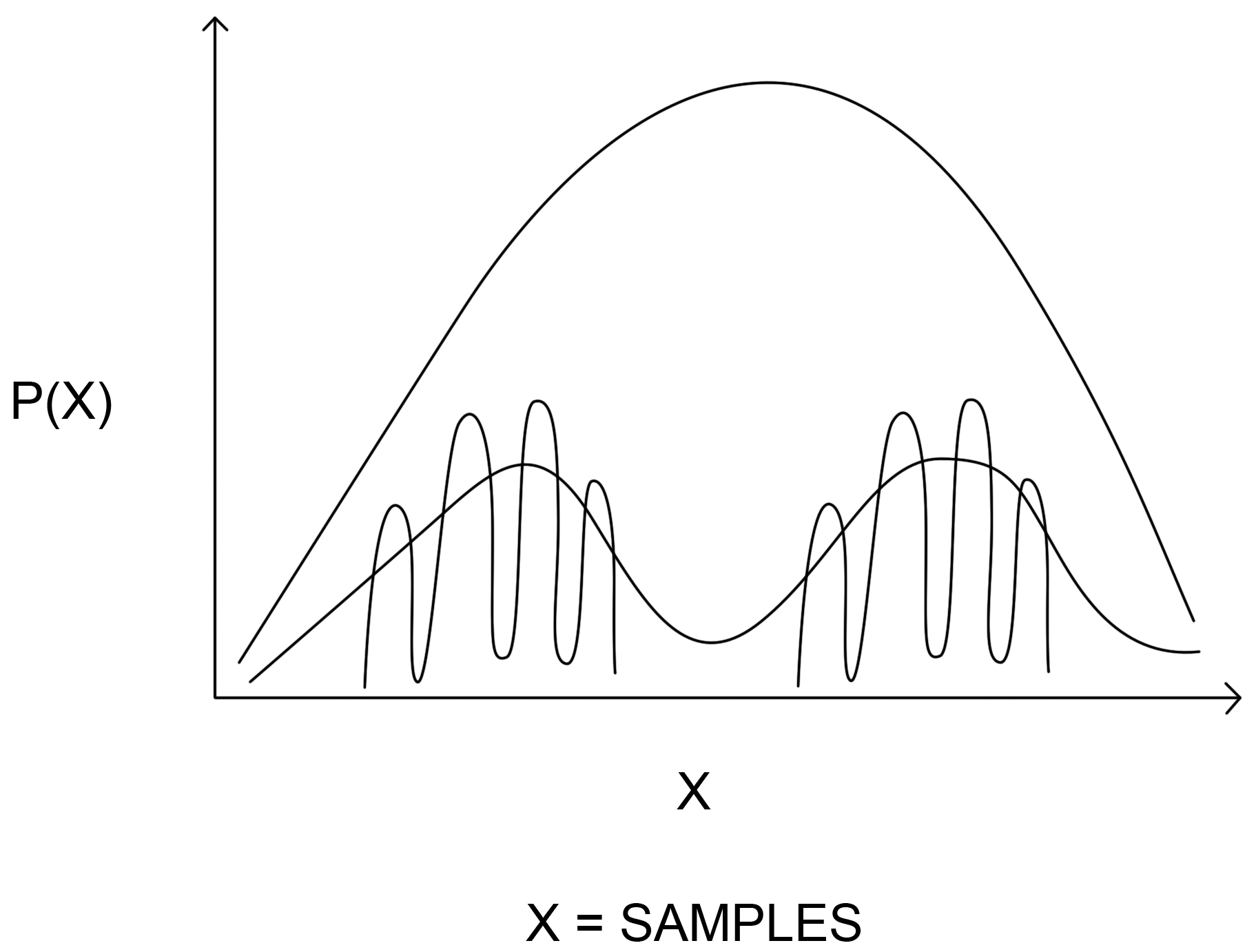

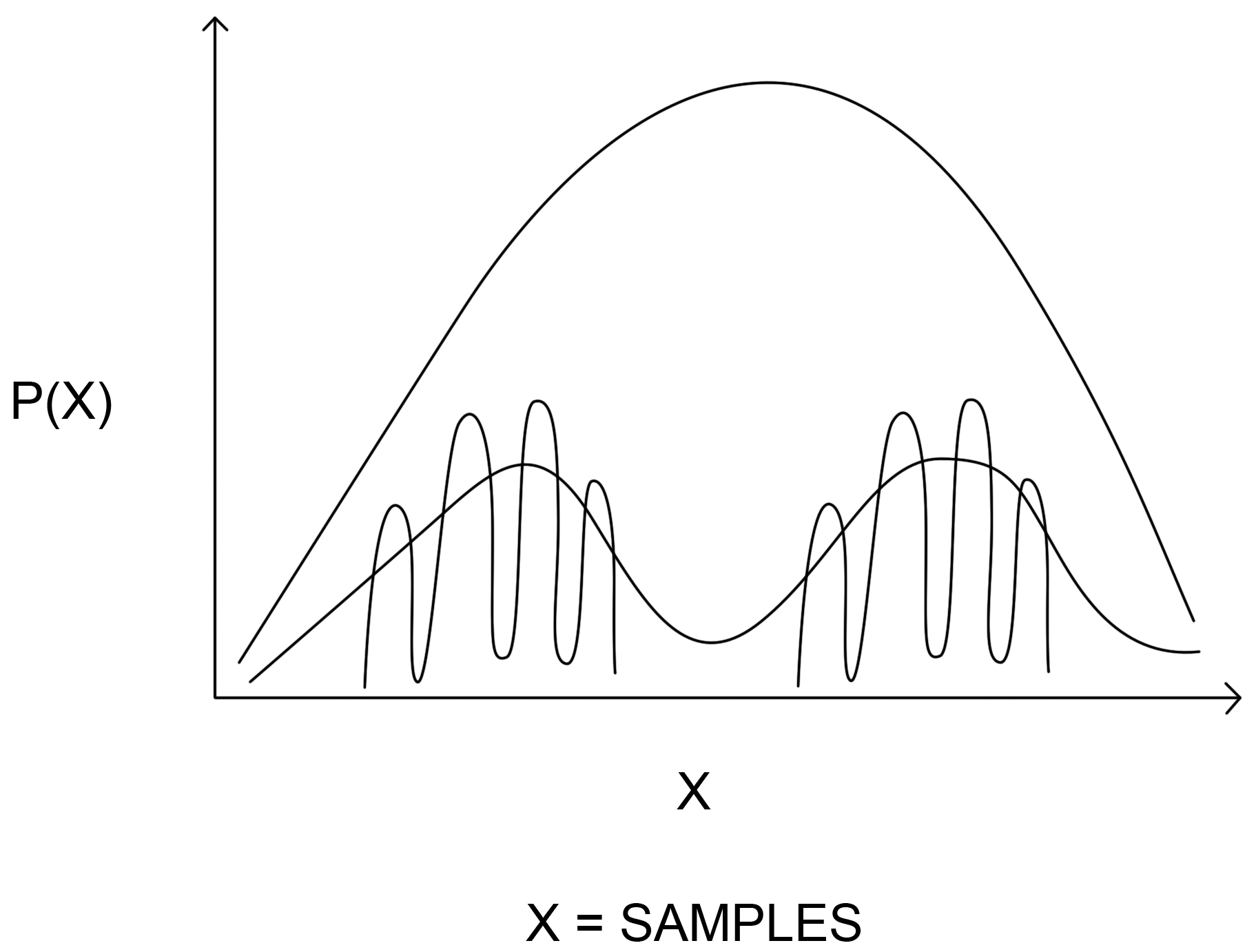

Density estimation problems are statistical learning methods used in machine learning estimations from dense data that is otherwise unobservable. Technically, density estimation is the technique of computing the probability of the density function. Density estimation can be applied on path-parametric and non-parametric data. Medical analysis often uses these techniques for identifying symptoms related to diseases from a very large population. The following diagram shows the density estimation graph:

Deep learning is the form of machine learning where systems learn by examples. This is a more advanced form of machine learning. Deep learning is the study of deep neural networks and requires much larger datasets. Today deep learning is the most sought after technique. Some popular examples of deep learning applications include self driving cars, smart speakers, home-pods, and so on.

So far we have dealt with different machine learning systems. In this section we will discuss the algorithms that drive them. The algorithms discussed here fall under one or many groups of machine learning that we have already covered.

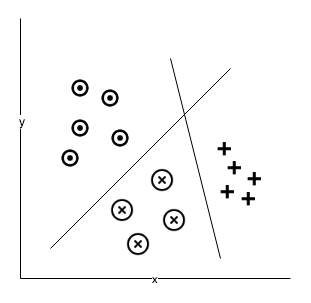

Support vector machines (SVMs) are supervised learning algorithms used in both linear and non linear classification. SVMs operate by creating an optimal hyperplane in high dimensional space. The separation created by this hyperplane is called class. SVMs need very little tuning once trained. They are used in high performing systems because of the reliability they have to offer.

SVMs are also used in regression analysis and in ranking and categorization.

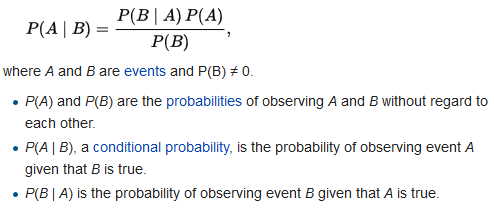

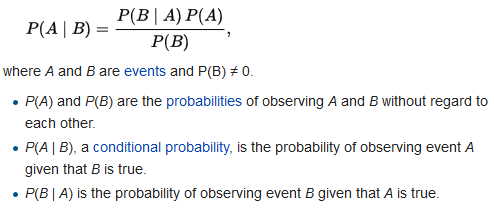

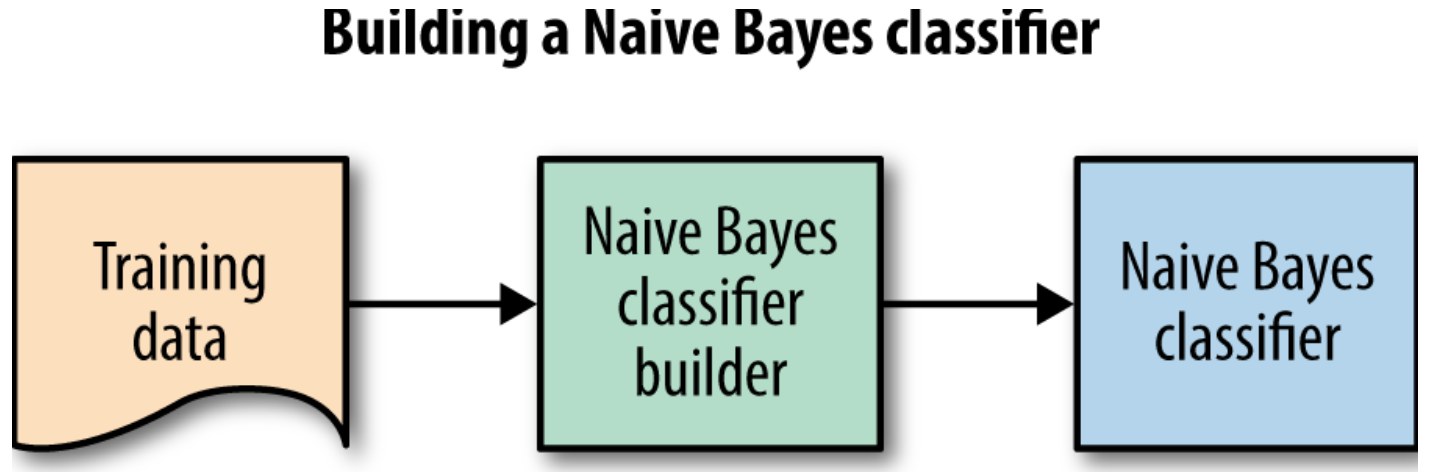

Bayesian network (BN) are probabilistic models that are primarily used for prediction and decision making. These are belief networks that use the principles of probability theory along with statistics. BN uses directed acyclic graph (DAG) to represent the relationship of variables and any other corresponding dependencies.

Decision tree learning is a predictive machine learning technique that uses decision trees. Decision trees make use of decision analysis and predict the value of the target. Decision trees are simple implementations of classification problems and popular in operations research. Decisions are made by the output value predicted by the conditional variable.

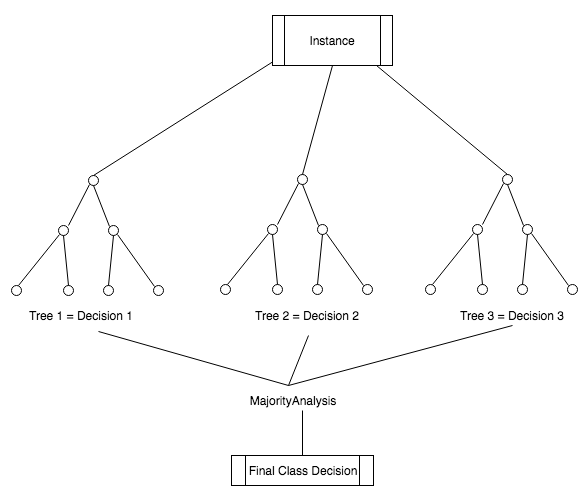

Random forests are extensions of decision tree learning. Here, several decisions trees are collectively used to make predictions. Since this is an ensemble, they are stable and reliable. Random forests can go in-depth to make irregular decisions. A popular use case for random forest is the quality assessment of text documents.

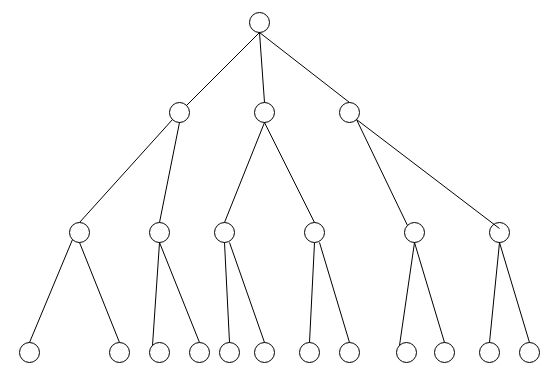

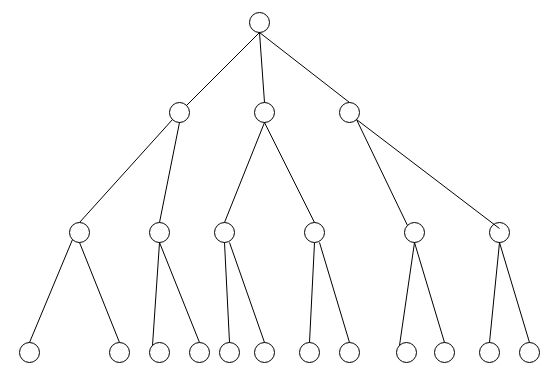

Hierarchical algorithms are a form of clustering algorithm. They are sometimes referred as the hierarchical clustering algorithm (HCA). HCA can either be bottom up or agglomerative, or they may be top down or divisive. In the agglomerative approach, the first iteration forms its own cluster and gradually smaller clusters are merged to move up the hierarchy. The top down divisive approach starts with a single cluster that is recursively broken down into multiple clusters.

Genetic algorithms are meta-heuristic algorithms used in constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. They mimic the physiological evolution process of humans and use these insights to solve problems. Genetic algorithms are known to outperform some traditional machine learning and search algorithms because they can withstand noise or changes in input pattern.

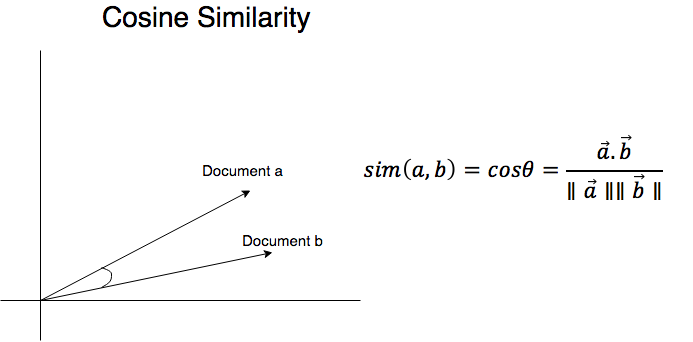

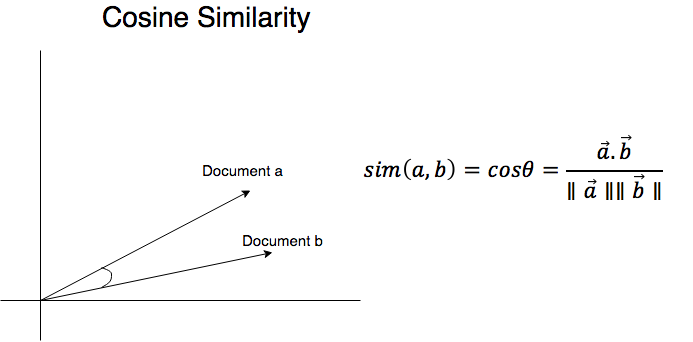

Similarity algorithm are predominantly used in the field of text mining. Cosine similarity is a popular algorithm primarily used to compare the similarity between documents. The inner product space of two vectors identifies the amount of similarity between two documents. Similarity algorithms are used in authorship and plagiarism detection techniques.

ANNs are intelligent computing systems that mimic the human nervous system. ANN comprises multiple nodes, both input and output. These input and output nodes are connected by a layer of hidden nodes. The complex relationship between input layers helps genetic algorithms are known like the human body does.

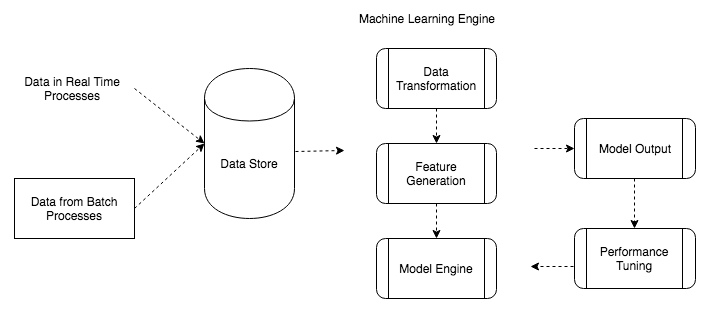

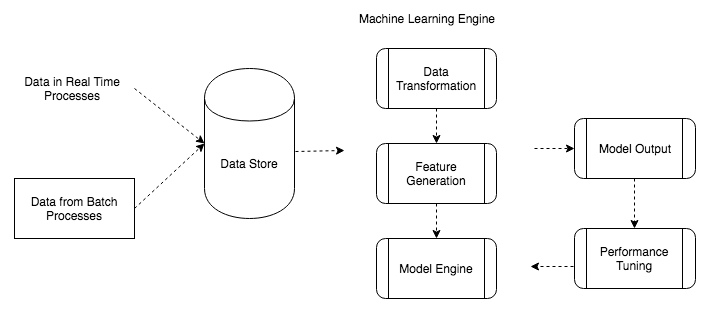

A typical machine learning system comprises a pipeline of processes that happens in a sequence for any type of machine learning system, irrespective of the industry. The following diagram shows a typical machine learning system and the sub-processes involved:

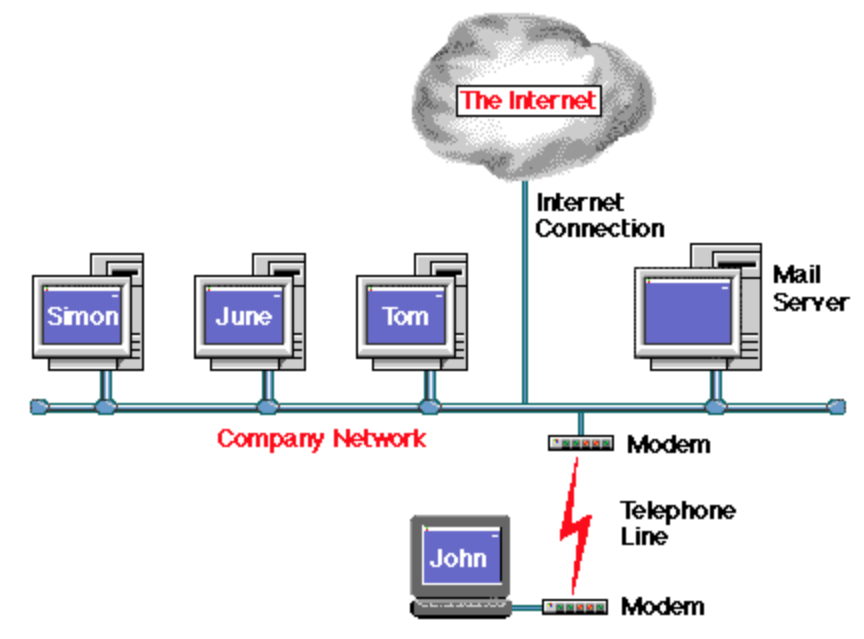

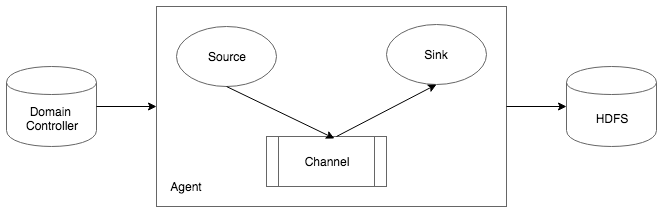

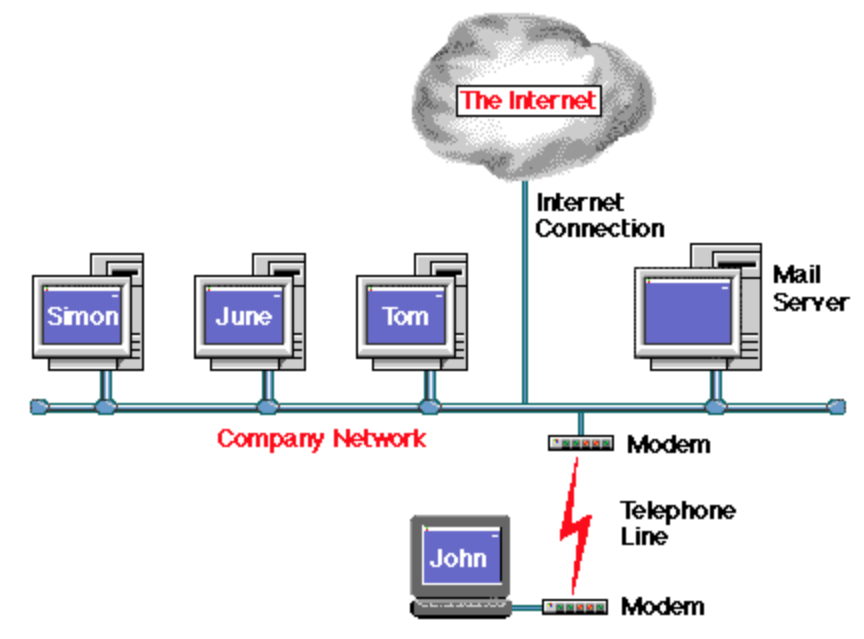

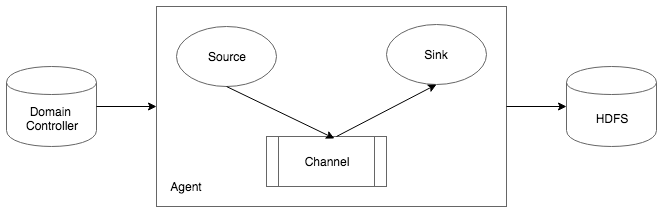

Data is ingested from different sources from real-time systems like IOTS (CCTV cameras), streaming media data, and transaction logs. Data that is ingested can also be data from batch processes or non-interactive processes like Linux cron jobs, Windows scheduler jobs, and so on. Single feed data like raw text data, log files, and process data dumps are also taken in by data stores. Data from enterprise resource planning (ERP), customer relationship management (CRM), and operational systems (OS) is also ingested. Here we analyze some data ingestors that are used in continuous, real-time, or batched data ingestion:

The raw or aggregated data from data collectors is stored in data stores, like SQL databases, NoSQL databases, data warehouses, and distributed systems, like HDFS. This data may require some cleaning and preparation if it is unstructured. The file format in which the data is received varies from database dumps, JSON files, parquet files, avro files, and even flat files. For distributed data storage systems, the data upon ingestion gets distributed to different file formats.

Some of the popular data stores available for use as per industry standards are:

A machine learning model engine is responsible for managing the end-to-end flows involved in making the machine learning framework operational. The process includes data preparation, feature generation, training, and testing a model. In the next section we will discuss each of this processes in detail.

Data preparation is the stage where data cleansing is performed to check for the consistency and integrity of the data. Once the data is cleansed, the data is often formatted and sampled. The data is normalized so that all the data can be measured in the same scale. Data preparation also includes data transformation where the data is either decomposed or aggregated.

Feature generation is the process where data in analyzed and we look for patterns and attributes that may influence model results. Features are usually mutually independent, and are generated from either raw data or aggregated data. The primary goal of feature generation is performing dimensionality reduction and improved performance.

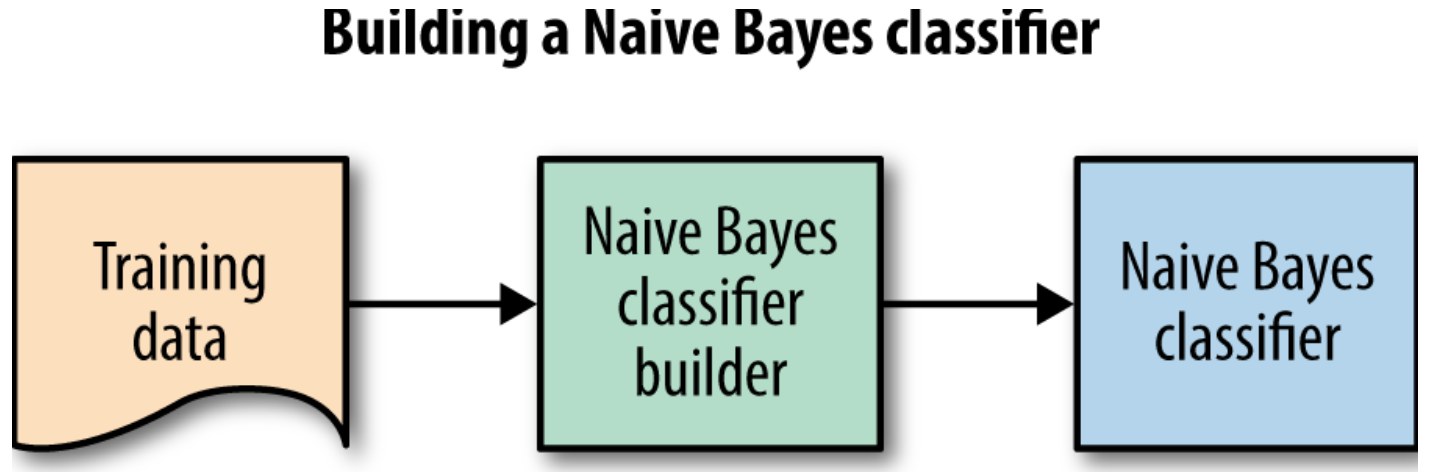

Model training is the phase in which a machine learning algorithm learns from the data in hand. The learning algorithm detects data patterns and relationships, and categorizes data into classes. The data attributes need to be properly sampled to attain the best performance from the models. Usually 70-80 percent of the data is used in the training phase.

In the testing phase we validate the model we built in the testing phase. Testing is usually done with 20 percent of the data. Cross validations methods help determine the model performance. The performance of the model can be tested and tuned.

Performance tuning and error detection are the most important iterations for a machine learning system as it helps improve the performance of the system. Machine learning systems are considered to have optimal performance if the generalized function of the algorithm gives a low generalization error with a high probability. This is conventionally known as the probably approximately correct (PAC) theory.

To compute the generalization error, which is the accuracy of classification or the error in forecast of regression model, we use the metrics described in the following sections.

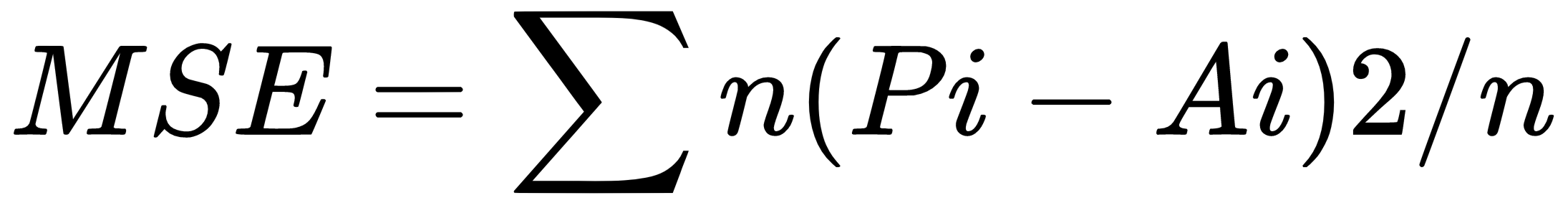

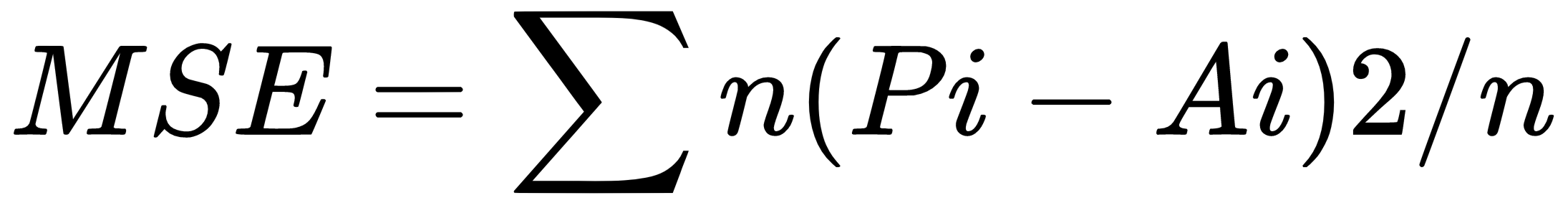

Imagine for a regression problem we have the line of best fit and we want to measure the distance of each point from the regression line. Mean squared error (MSE) is the statistical measure that would compute these deviations. MSE computes errors by finding the mean of the squares for each such deviations. The following shows the diagram for MSE:

Where i = 1, 2, 3...n

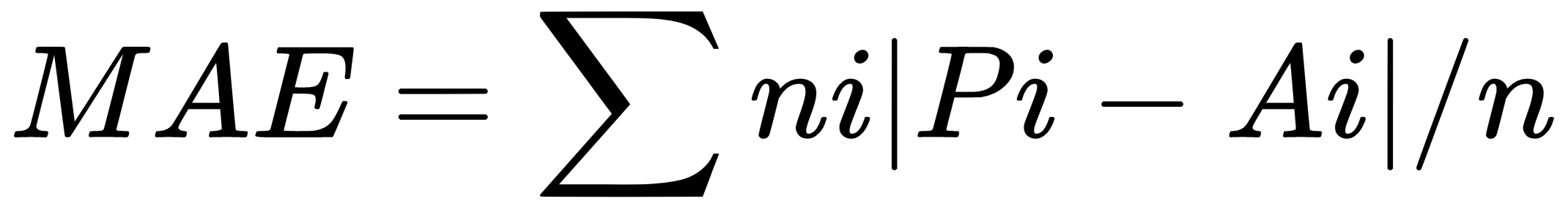

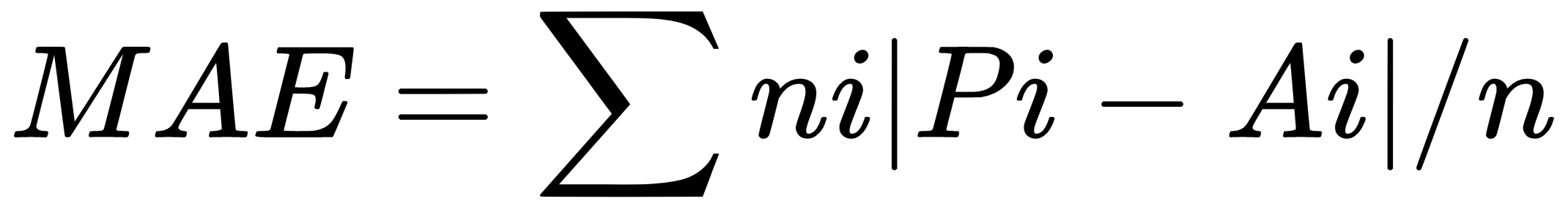

Mean absolute error (MAE) is another statistical method that helps to measure the distance (error) between two continuous variables. A continuous variable can be defined as a variable that could have an infinite number of changing values. Though MAEs are difficult to compute, they are considered as better performing than MSE because they are independent of the square function that has a larger influence on the errors. The following shows the MAE in action:

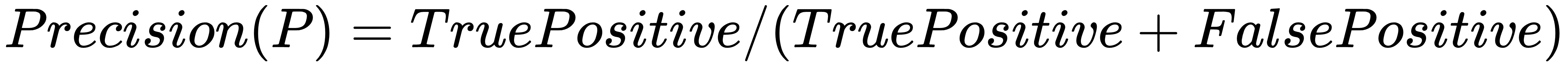

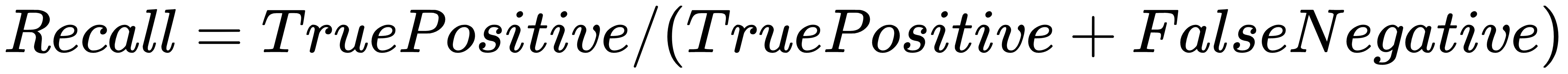

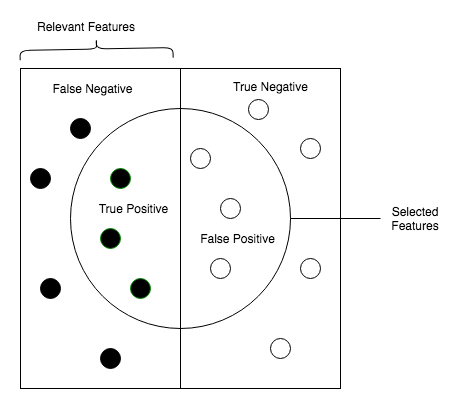

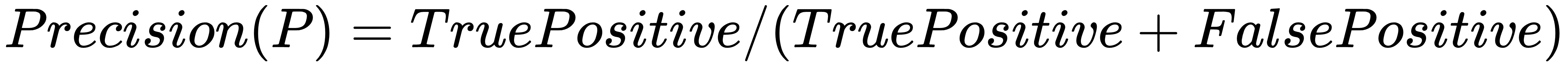

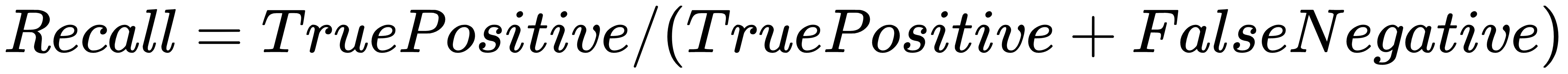

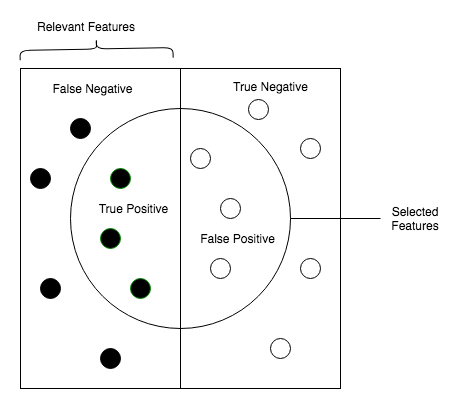

Another measure for computing the performance for classification problems is estimating the precision, recall, and accuracy of the model.

Precision is defined as the number of true positives present in the mixture all retrieved instances:

Recall is the number of true positives identified from the total number of true positives present in all relevant documents:

Accuracy measures the percentage of closeness of the measured value from the standard value:

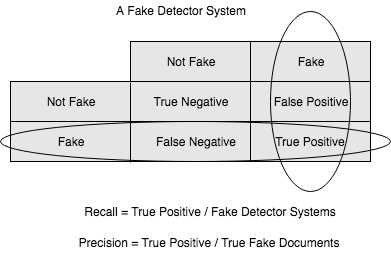

Fake document detection is a real-world use case that could explain this. For fake news detector systems, precision is the number of relevant fake news articles detected from the total number of documents that are detected. Recall, on the other hand, measures the number of fake news articles that get retrieved from the total number of fake news present. Accuracy measures the correctness with which such a system detects fake news. The following diagram shows the fake detector system:

Models with a low degree of accuracy and high generalization errors need improvement to achieve better results. Performance can be improved either by improving the quality of data, switching to a different algorithm, or tuning the current algorithm performance with ensembles.

Fetching more data to train a model can lead to an improvement in performance. Lowered performance can also be due to a lack of clean data, hence the data needs to be cleansed, resampled, and properly normalized. Revisiting the feature generation can also lead to improved performance. Very often, a lack of independent features within a model are causes for its skewed performance.

A model performance is often not up to the mark because we have not made the right choice of algorithm. In such scenarios, performing a baseline testing with different algorithms helps us make a proper selection. Baseline testing methods include, but are not limited to, k-fold cross validations.

The performance of a model can be improved by ensembling the performance of multiple algorithms. Blending forecasts and datasets can help in making correct predictions. Some of the most complex artificially intelligent systems today are a byproduct of such ensembles.

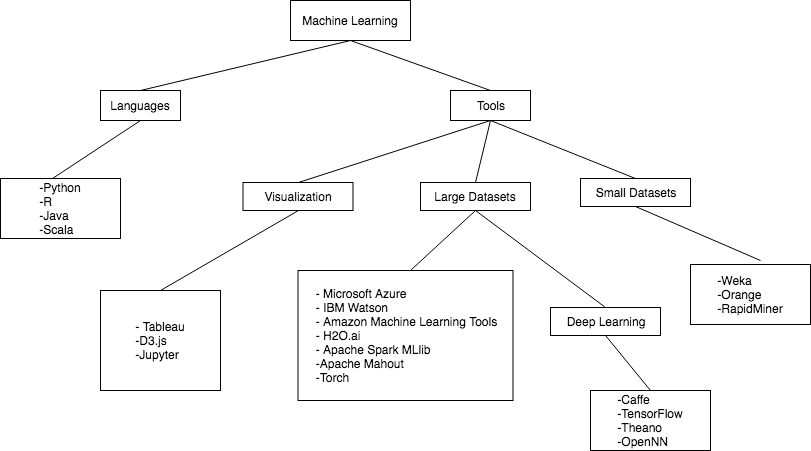

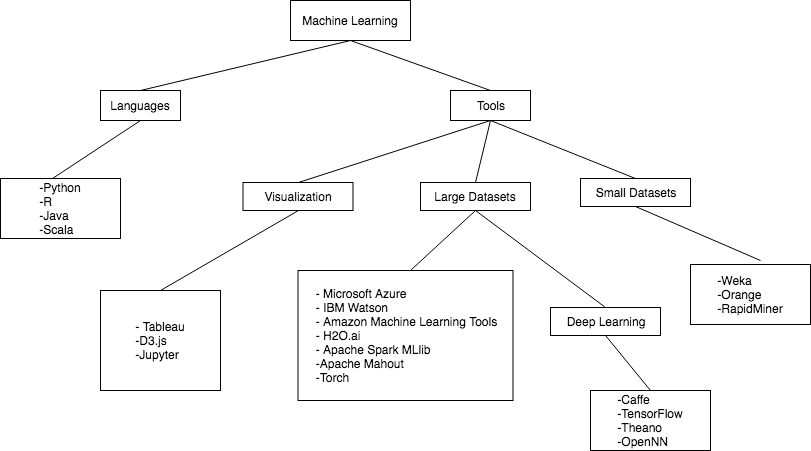

We have so far established that machine learning is used heavily in industries and in the field of data driven research. Thus let's go through some machine learning tools that help to create such machine learning applications with both small or larger-scale data. The following flow diagram shows the various machine learning tools and languages that are currently at our disposal:

Python is the preferred language for developing machine learning applications. Though not the fastest, Python is extensively adapted by data scientists because of its versatility.

Python supports a wide range of tools and packages that enable machine learning experts to implement changes with much agility. Python, being a scripting language, is easy to adapt and code in. Python is extensively used for the graphical user interfaces (GUI) development.

Python 2.x is an older version compared to Python 3.x. Python 3.x was first developed in 2008 while the last Python 2.x update came out in 2010. Though it is perfectly fine to use table application with the 2.x, it is worthwhile to mention that 2.x has not been developed any further from 2.7.

Almost every machine learning package in use has support for both the 2.x and the 3.x versions. However, for the purposes of staying up-to-date, we will be using version 3.x in the uses cases we discuss in this book.

Once you have made a decision to install Python 2 or Python 3, you can download the latest version from the Python website at the following URL:

https://www.python.org/download/releases/

On running the downloaded file, Python is installed in the following directory unless explicitly mentioned:

C:\Python2.x

C:\Python3.x

/usr/bin/python

/usr/bin/python

To check the version of Python installed, you can run the following code:

import sys

print ("Python version:{}",format(sys.version))

The top Python interactive development environments (IDEs) commonly used for developing Python code are as follows:

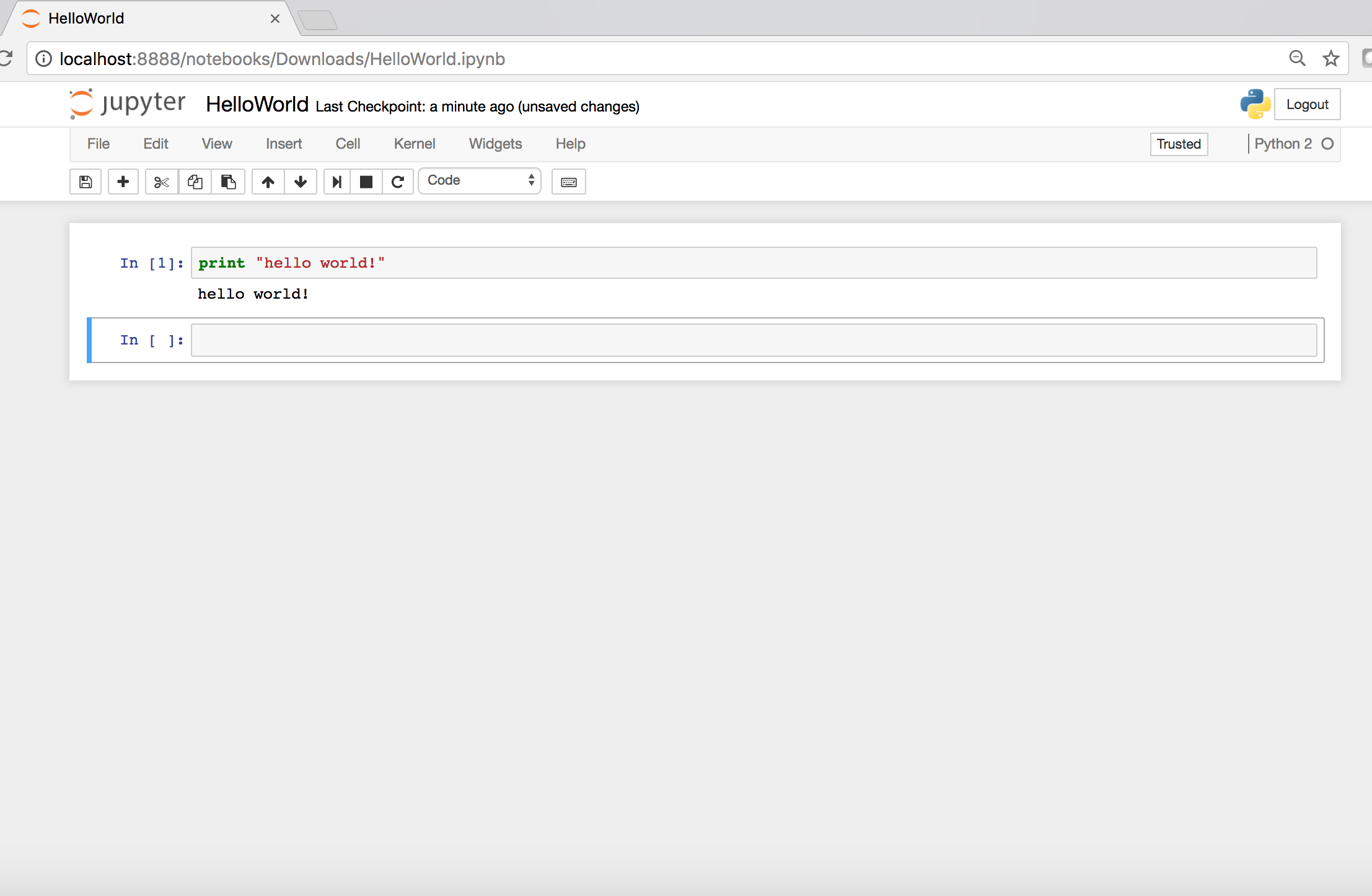

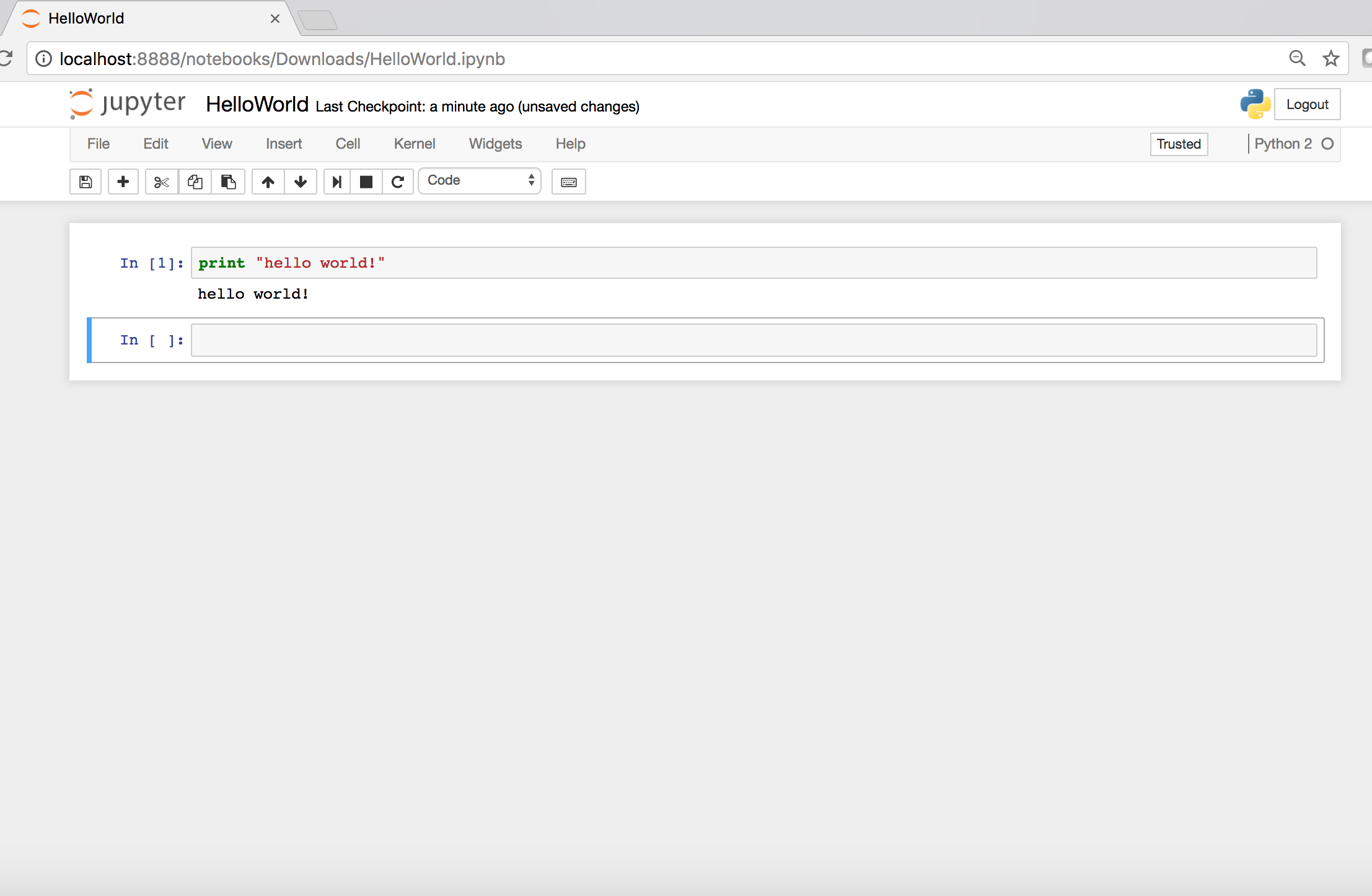

For developmental purposes, we will be using IPython Jupyter Notebook due to its user-friendly interactive environment. Jupyter allows code transportation and easy mark-downs. Jupyter is browser-based, thus supporting different types of imports, exports, and parallel computation.

To download Jupyter Notebook, it is recommended that you:

https://www.anaconda.com/download/

pip install --upgrade pip

pip3 install jupyter

If the user is on Python 2, pip3 needs be replaced by pip.

After installation, you can just type jupyter notebook to run it. This opens Jupyter Notebook in the primary browser. Alternatively, you can open Jupyter from Anaconda Navigator. The following screenshot shows the Jupyter page:

In this section, we discuss packages that form the backbone for Python's machine learning architecture.

NumPy is a free Python package that is used to perform any computation task. NumPy is absolutely important when doing statistical analysis or machine learning. NumPy contains sophisticated functions for solving linear algebra, Fourier transform, and other numerical analysis. NumPy can be installed by running the following:

pip install numpy

To install this through Jupyter, use the following:

import sys

!{sys.executable} -m pip install numpy

SciPy is a Python package that is created on top of the NumPy array object. SciPy contains an array of functions, such as integration, linear algebra, and e-processing functionalities. Like NumPy, it can also be installed likewise. NumPy and SciPy are generally used together.

To check the version of SciPy installed on your system, you can run the following code:

import scipy as sp

print ("SciPy version:{}",format(sp.version))

Scikit-learn is a free Python package that is also written in Python. Scikit-learn provides a machine learning library that supports several popular machine learning algorithms for classification, clustering, regression, and so on. Scikit-learn is very helpful for machine learning novices. Scikit-learn can be easily installed by running the following command:

pip install sklearn

To check whether the package is installed successfully, conduct a test using the following piece of code in Jupyter Notebook or the Python command line:

import sklearn

If the preceding argument throws no errors, then the package has been successfully installed.

Scikit-learn requires two dependent packages, NumPy and SciPy, to be installed. We will discuss their functionalities in the following sections. Scikit-learn comes with a few inbuilt datasets like:

Other public datasets from libsvm and svmlight can also be loaded, as follows:

http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~cjlin/libsvmtools/datasets/

A sample script that uses scikit-learn to load data is as follows:

from sklearn.datasets import load_boston

boston=datasets.load_boston()

The pandas open source package that provides easy to data structure and data frame. These are powerful for data analysis and are used in statistical learning. The pandas data frame allows different data types to be stored alongside each other, much unlike the NumPy array, where same data type need to be stored together.

Matplotlib is a package used for plotting and graphing purposes. This helps create visualizations in 2D space. Matplotlib can be used from the Jupyter Notebook, from web application server, or from the other user interfaces.

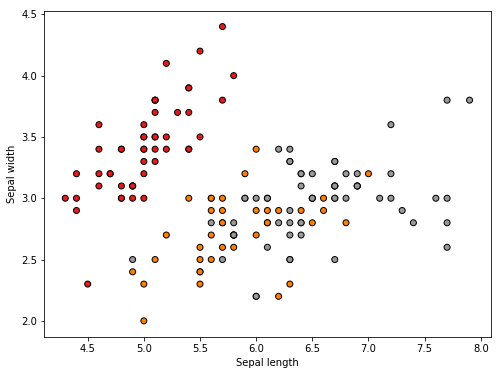

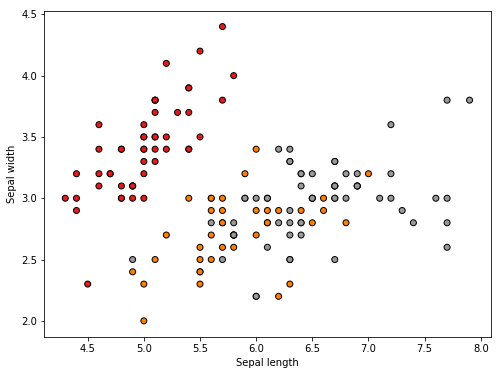

Let's plot a small sample of the iris data that is available in the sklearn library. The data has 150 data samples and the dimensionality is 4.

We import the sklearn and matplotlib libraries in our Python environment and check the data and the features, as shown in the following code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import datasets

iris = datasets.load_iris()

print(iris.data.shape) # gives the data size and dimensions

print(iris.feature_names)

The output can be seen as follows:

We extract the first two dimensions and plot it on an X by Y plot as follows:

X = iris.data[:, :2] # plotting the first two dimensions

y = iris.target

x_min, x_max = X[:, 0].min() - .5, X[:, 0].max() + .5

y_min, y_max = X[:, 1].min() - .5, X[:, 1].max() + .5

plt.figure(2, figsize=(8, 6))

plt.clf()plt.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=y, cmap=plt.cm.Set1,

edgecolor='k')

plt.xlabel('Sepal length')

plt.ylabel('Sepal width')

We get the following plot:

MongoDB can store unstructured data that is fast and capable of retrieving large amounts of data over a small time. MongoDB uses a JSON format to store data in rows. Thus, any data without a common schema can be stored. We will be using MongoDB in the next few chapters because of its distributed nature. MongoDB has a fault tolerant distribution by shredding the data into multiple servers. MongoDB generates a primary key as you store data.

To install MongoDB on your Windows, macOS, or Linux systems, run the following steps:

https://www.mongodb.com/download-center

sudo apt-get install -y mongodb-org

To use MongoDB from within Python we will be using the PyMongo Library. PyMongo contains tools that helps you to work with MongoDB. There are libraries that act as an object data mapper for MongoDB, however PyMongo is the recommended one.

To install PyMongo, you can run the following:

python -m pip install pymongo

Alternatively, you can use the following:

import sys

!{sys.executable} -m pip install pymongo

Finally, you can get started with using MongoDB by importing the PyMongo library and then setting up a connection with MongoDB, as shown in the following code:

import pymongo

connection = pymongo.MongoClient()

On creating a successful connection with MongoDB, you can continue with different operations, like listing the databases present and so on, as seen in the following argument:

connection.database_names() #list databases in MongoDB

Each database in MongoDB contains data in containers called collections. You can retrieve data from these collections to pursue your desired operation, as follows:

selected_DB = connection["database_name"] selected_DB.collection_names() # list all collections within the selected database

In this section we will discuss how to set up a machine learning environment. This starts with a use case that we are trying to solve, and once we have shortlisted the problem, we select the IDE where we will do the the end-to-end coding.

We need to procure a dataset and divide the data into testing and training data. Finally, we finish the setup of the environment by importing the ideal packages that are required for computation and visualization.

Since we deal with machine learning use cases for the rest of this book, we choose our use case in a different sector. We will go with the most generic example, that is, prediction of stock prices. We use a standard dataset with xx points and yy dimensions.

We come up with a use case that predicts the onset of a given few features by creating a stock predictor that ingests in a bunch of parameters and uses these to make a prediction.

We can use multiple data sources, like audio, video, or textual data, to make such a prediction. However, we stick to a single text data type. We use scikit-learn's default diabetes dataset to to come up with a single machine learning model that is regression for doing the predictions and error analysis.

We will use open source code available from the scikit-learn site for this case study. The link to the code is available as shown in the following code:

http://scikit-learn.org/stable/auto_examples/linear_model/plot_ols.html#sphx-glr-auto-examples-linear-model-plot-ols-py

We will import the following packages:

Since we will be using regression for our analysis, we import the linear_model, mean_square_error, and r2_score libraries, as seen in the following code:

print(__doc__)

# Code source: Jaques Grobler

# License: BSD 3 clause

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn import datasets, linear_model

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, r2_score

We import the diabetes data and perform the following actions:

The associated code for the preceding code is:

# Load the diabetes dataset

diabetes = datasets.load_diabetes()

print(diabetes.data.shape) # gives the data size and dimensions

print(diabetes.feature_names

print(diabetes.DESCR)

The data has 442 rows of data and 10 features. The features are:

['age', 'sex', 'bmi', 'bp', 's1', 's2', 's3', 's4', 's5', 's6']

To train the model we use a single feature, that is, the bmi of the individual, as shown:

# Use only one feature

diabetes_X = diabetes.data[:, np.newaxis, 3]

Earlier in the chapter, we discussed the fact that selecting a proper training and testing set is integral. The last 20 items are kept for testing in our case, as shown in the following code:

# Split the data into training/testing sets

diabetes_X_train = diabetes_X[:-20]#everything except the last twenty itemsdiabetes_X_test = diabetes_X[-20:]#last twenty items in the array

Further we also split the targets into training and testing sets as shown:

# Split the targets into training/testing sets

diabetes_y_train = diabetes.target[:-20]

everything except the last two items

diabetes_y_test = diabetes.target[-20:]

Next we perform regression on this data to generate results. We use the testing data to fit the model and then use the testing dataset to make predictions on the test dataset that we have extracted, as seen in the following code:

# Create linear regression object

regr = linear_model.LinearRegression()

#Train the model using the training sets

regr.fit(diabetes_X_train, diabetes_y_train)

# Make predictions using the testing set

diabetes_y_pred = regr.predict(diabetes_X_test)

We compute the goodness of fit by computing how large or small the errors are by computing the MSE and variance, as follows:

# The mean squared error

print("Mean squared error: %.2f"

% mean_squared_error(diabetes_y_test, diabetes_y_pred))

# Explained variance score: 1 is perfect prediction

print('Variance score: %.2f' % r2_score(diabetes_y_test, diabetes_y_pred))

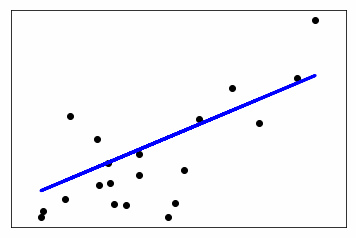

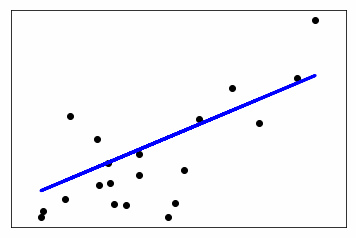

Finally, we plot the prediction using the Matplotlib graph, as follows:

# Plot outputs

plt.scatter(diabetes_X_test, diabetes_y_test, color='black')

plt.plot(diabetes_X_test, diabetes_y_pred, color='blue', linewidth=3)

plt.xticks(())

plt.yticks(())

plt.show()

The output graph looks as follows:

In this chapter, we have gone through the basics of machine learning. We briefly discussed how machine learning fits into daily use cases and its relationship with the cybersecurity world. We also learned the different aspects of data that we need to know to deal with machine learning. We discussed the different segregation of machine learning and the different machine learning algorithms. We also dealt with real-world platforms that are available on this sector.

Finally, we learned the hands-on aspects of machine learning, IDE installation, installation of packages, and setting up the environment for work. Finally, we took an example and worked on it from end to end.

In the next chapter, we will learn about time series analysis and ensemble modelling.

In this chapter, we will study two important concepts of machine learning: time series analysis and ensemble learning. These are important concepts in the field of machine learning.

We use these concepts to detect anomalies within a system. We analyze historic data and compare it with the current data to detect deviations from normal activities.

The topics that will be covered in this chapter are the following:

A time series is defined as an array of data points that is arranged with respect to time. The data points are indicative of an activity that takes place at a time interval. One popular example is the total number of stocks that were traded at a certain time interval with other details like stock prices and their respective trading information at each second. Unlike a continuous time variable, these time series data points have a discrete value at different points of time. Hence, these are often referred to as discrete data variables. Time series data can be gathered over any minimum or maximum amount of time. There is no upper or lower bound to the period over which data is collected.

Time series data has the following:

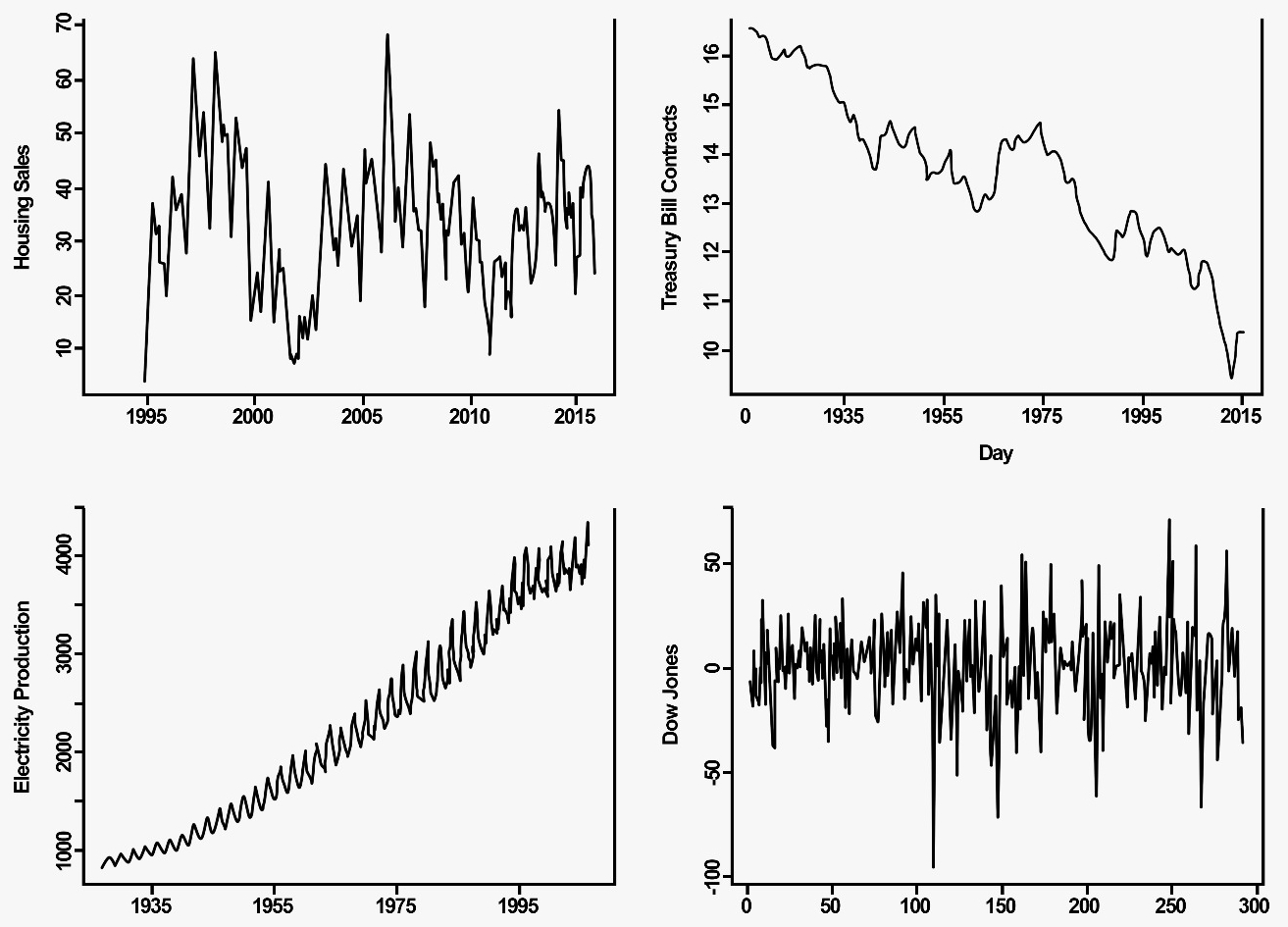

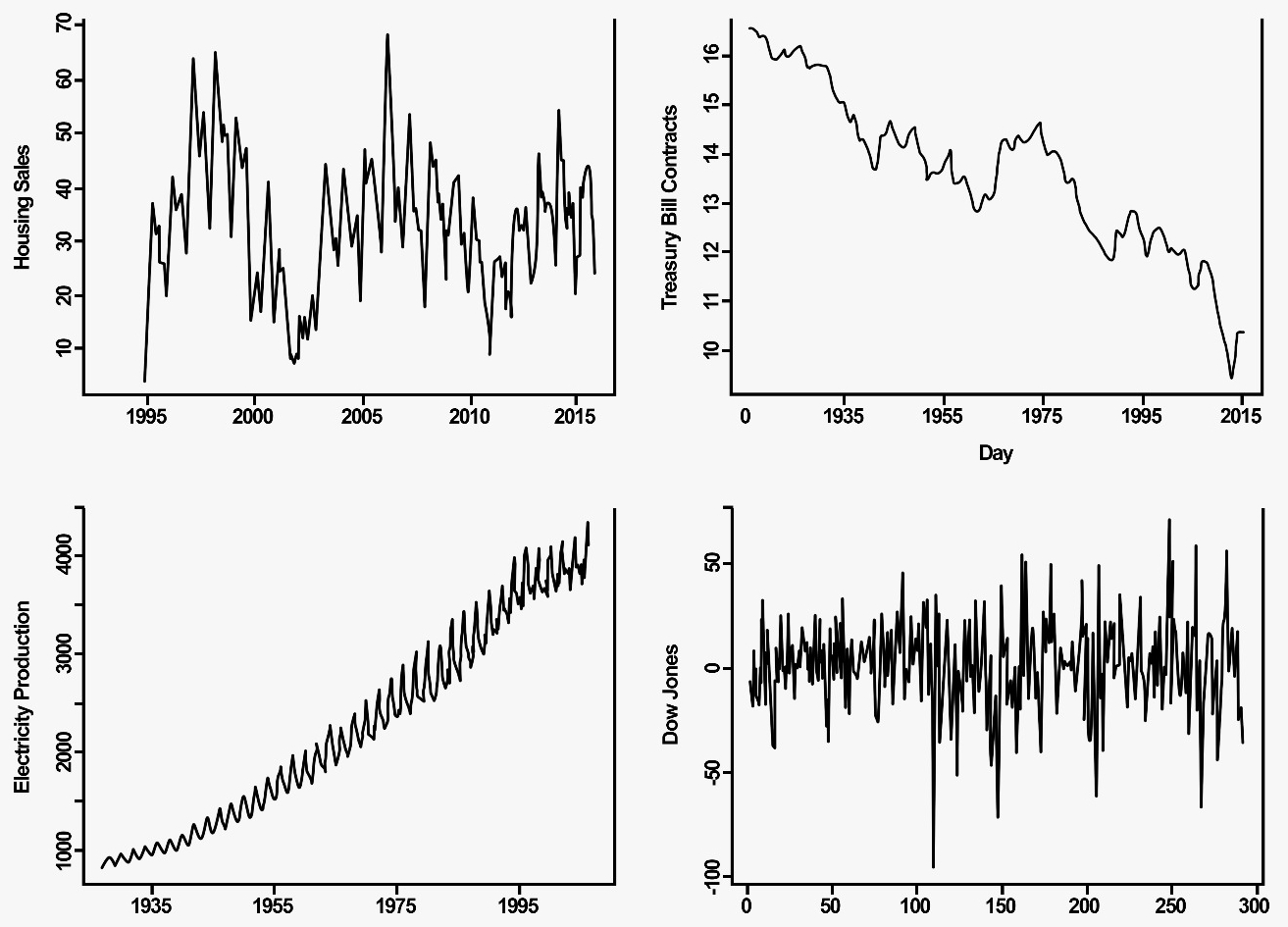

The following diagram shows the graphs for Housing Sales (top-left), Treasury Bill Contracts (top-right), Electricity Production (bottom-left), and Dow Jones (bottom-right):

Time series analysis is the study of where time series data points are mined and investigated. It is a method of interpreting quantitative data and computing the changes that it has undergone with respect to time. Time series analysis involves both univariate and multivariate time analysis. These sorts of time-based analysis are used in many areas like signal processing, stock market predictions, weather forecasting, demographic related-predictions, and cyber-attack detection.

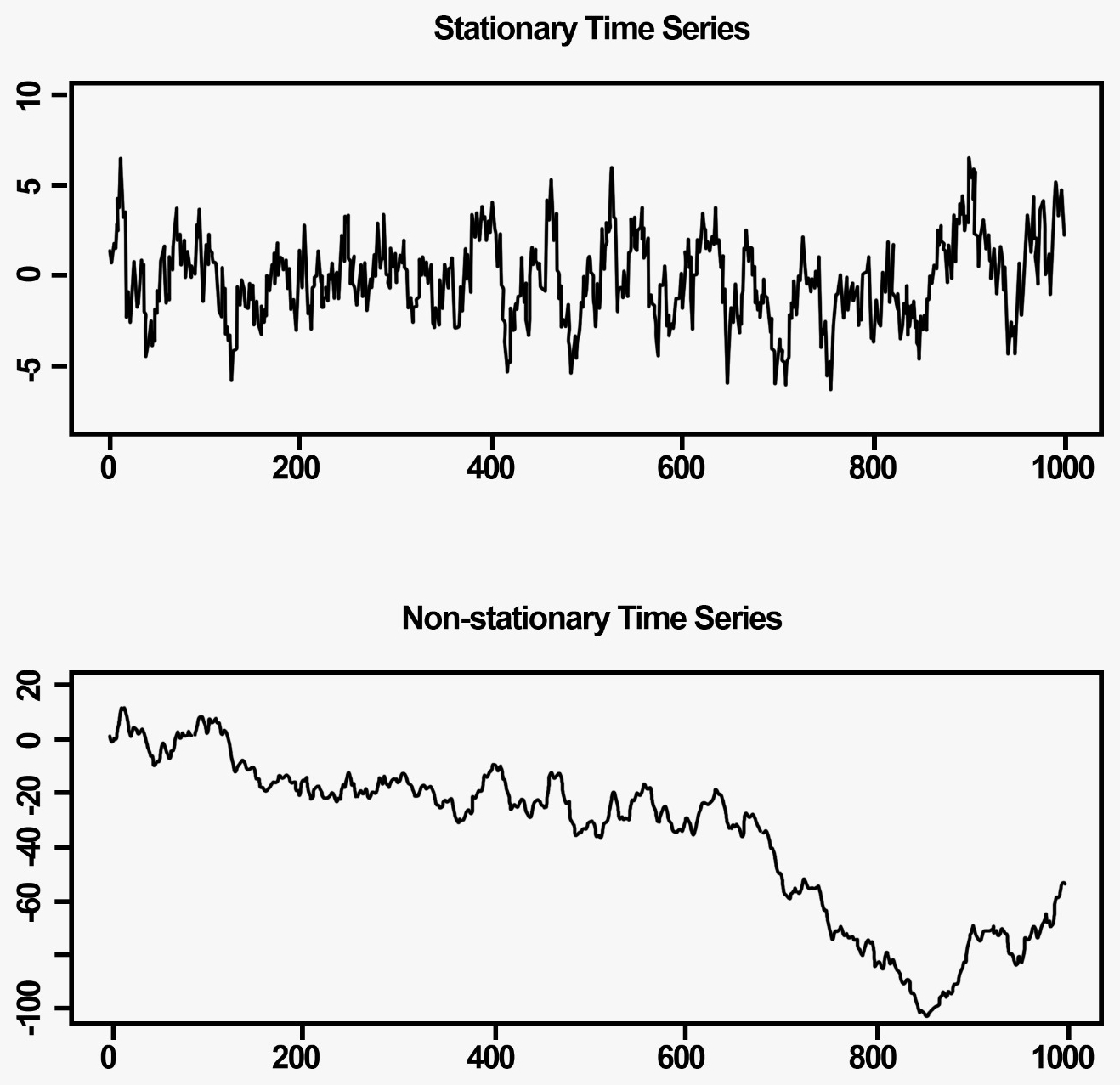

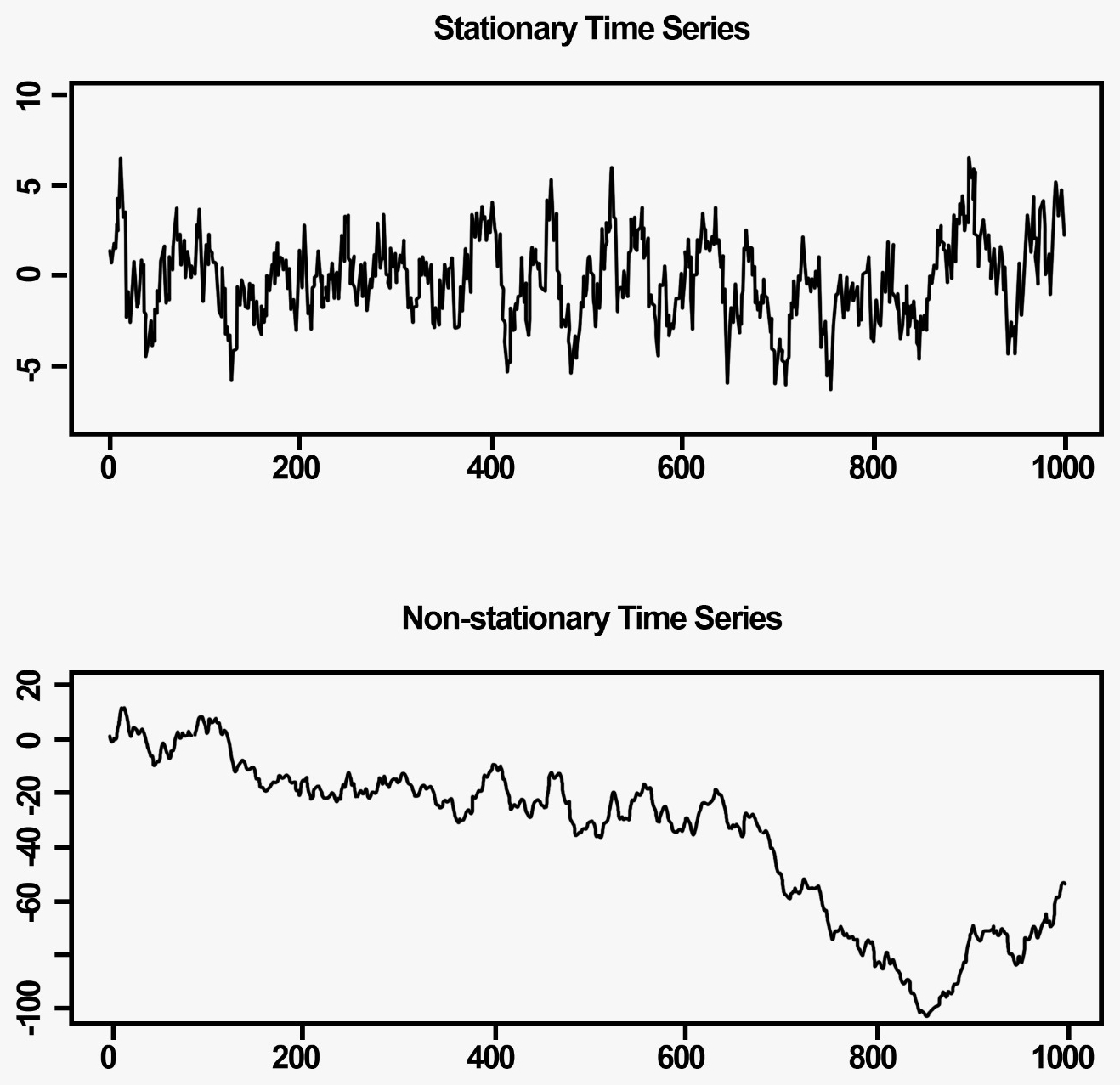

A time series needs to be stationary or else building a time series model on top is not technically possible. This can be called a prerequisite for model building. For a stationary time series, the mean, variance, and autocorrelation are consistently distributed over time.

The following graphs show the wave forms for Stationary Time Series (top) and Non-Stationary Time series (bottom):

A strictly stationary process is a process with a random probability distribution, such that its joint probability distribution is independent of time.

Strong sense stationarity: A time series T is called strongly or strictly stationary if two or more random vectors have equal joint distribution for all indices and integers, for example:

Random vector 1 = { Xt1, Xt2, Xt3, ..., Xtn}

Random vector 2 = { Xt1 +s, Xt2 + s, Xt3+s, ..., Xtn +s}

Weak or wide sense stationarity: A time series T is called weakly stationary if it has a shift invariance for the first and second moments of the process.

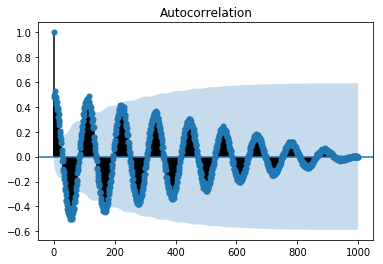

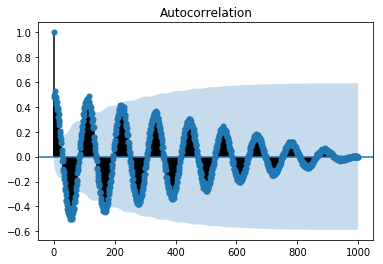

In this section, we will be learning about autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation function.

In order to choose two variables as a candidate for time series modeling, we are required to perform a statistical correlation analysis between the said variables. Here each variable, the Gaussian curve, and Pearson's coefficient are used to identify the correlation that exists between two variables.

In time series analysis, the autocorrelation measures historic data called lags. An autocorrelation function (ACF) is used to plot such correlations with respect to lag. In Python the autocorrelation function is computed as follows:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as p

from statsmodels.graphics.tsaplots import plot_acf

data = p.Series(0.7 * np.random.rand(1000) + 0.3 * np.sin(np.linspace(-9 * np.pi, 9 * np.pi, num=1000)))

plot_acf(data)

pyplot.show()

The output for the preceding code is as follows:

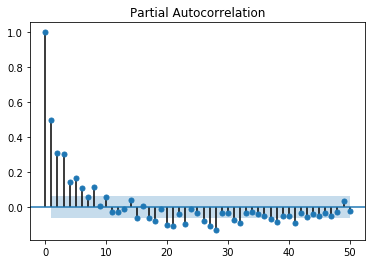

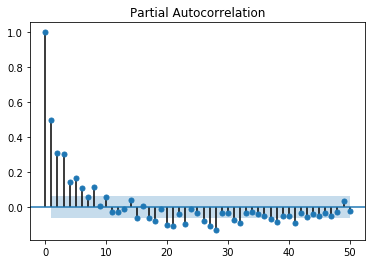

Partial autocorrelation function (PACF) can be defined as a time series where there is a restricted or incomplete correlation between the values for shorter time lags.

PACF is not at all like ACF; with PACE the autocorrelation of a data point at the current point and the autocorrelation at a period lag have a direct or indirect correlation. PACF concepts are heavily used in autoregressive models.

In Python, the PACF function can be computed as follows:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as p

from statsmodels.graphics.tsaplots import plot_pacf

data = p.Series(0.7 * np.random.rand(1000) + 0.3 * np.sin(np.linspace(-9 * np.pi, 9 * np.pi, num=1000)))

plot_pacf(data, lag = 50)

pyplot.show()

The output for PACF can be seen as shown:

Based on the use-case type that we have in hand, the relationship between the number of temporal sequences and time can be distributed among multiple classes. Problems bucketed into each of these classes have different machine learning algorithms to handle them.

Stochastic processes are random mathematical objects that can be defined using random variables. These data points are known to randomly change over time. Stochastic processes can again be divided into three main classes that are dependent on historic data points. They are autoregressive (AR) models, the moving average (MA) model, and integrated (I) models. These models combine to form the autoregressive moving average (ARMA), the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), and the autoregressive fractional integrated moving average (ARFIMA). We will use these in later sections of the chapter.

Artificial neural network (ANN) is an alternative to stochastic processes in time series models. ANN helps in forecasting, by using regular detection and pattern recognition. It uses this intelligence to detect seasonalities and helps generalize the data. In contrast with stochastic models like multilayer perceptrons, feedforward neural network (FNN), and time lagged neural network (TLNN) are mainly used in nonlinear time series models.

A support vector machine (SVM) is another accurate non-linear technique that can be used to derive meaningful insight from time series data. They work best when the data is non-linear and non-stationary. Unlike other time series models, SVMs can predict without requiring historic data.

Time series help detect interesting patterns in data, and thus identify the regularities and irregularities. Their parameters refer to the level of abstraction within the data. A time series model can thus be divided into components, based on the level of abstraction. These components are the systematic components and non-systematic components.

These are time series models that have recurring properties, and the data points show consistency. Hence they can be easily modeled. These systematic patterns are trends, seasonality, and levels observed in the data.

These are time series models that lack the presence of seasonal properties and thus cannot be easily modeled. They are haphazard data points marked against time and lack any trend, level, or seasonality. Such models are abundant in noise. Often inaccurate data collection schemes are responsible for such data patterns. Heuristic models can be used such non-systematic models.

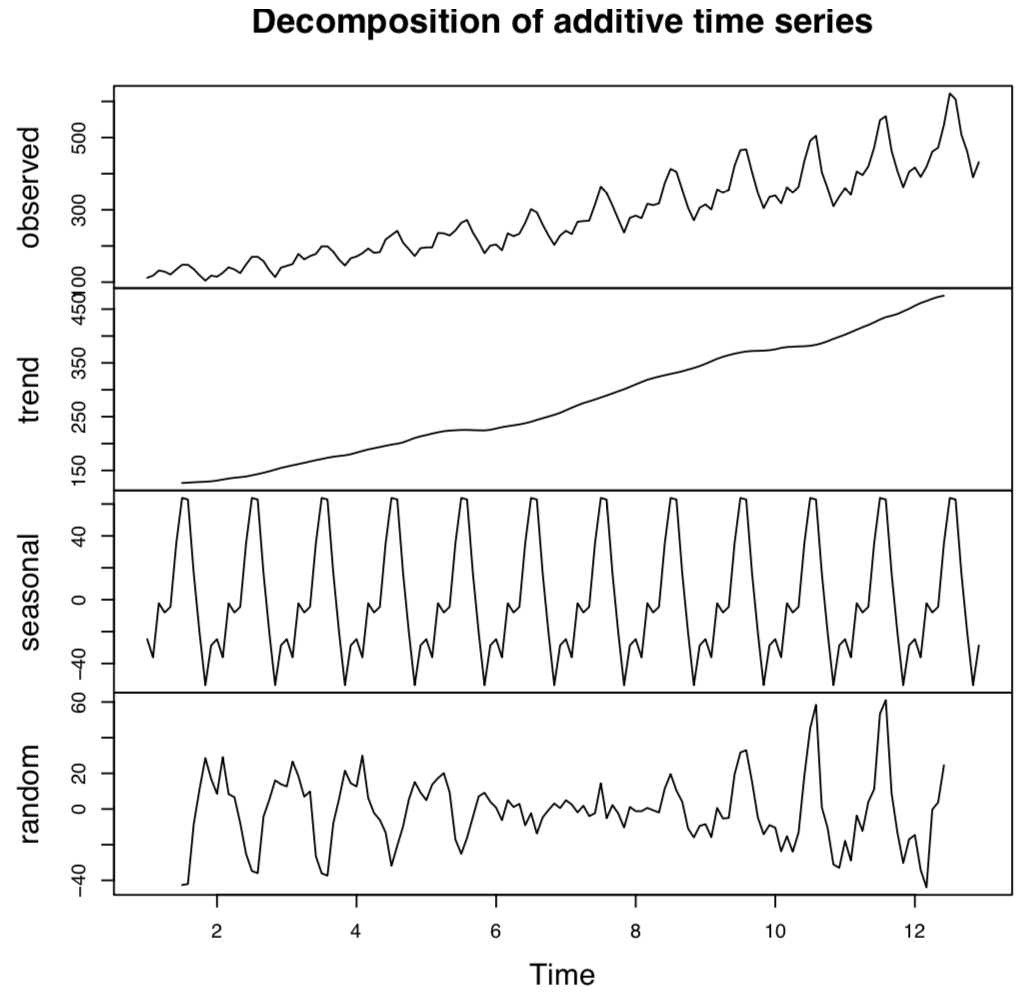

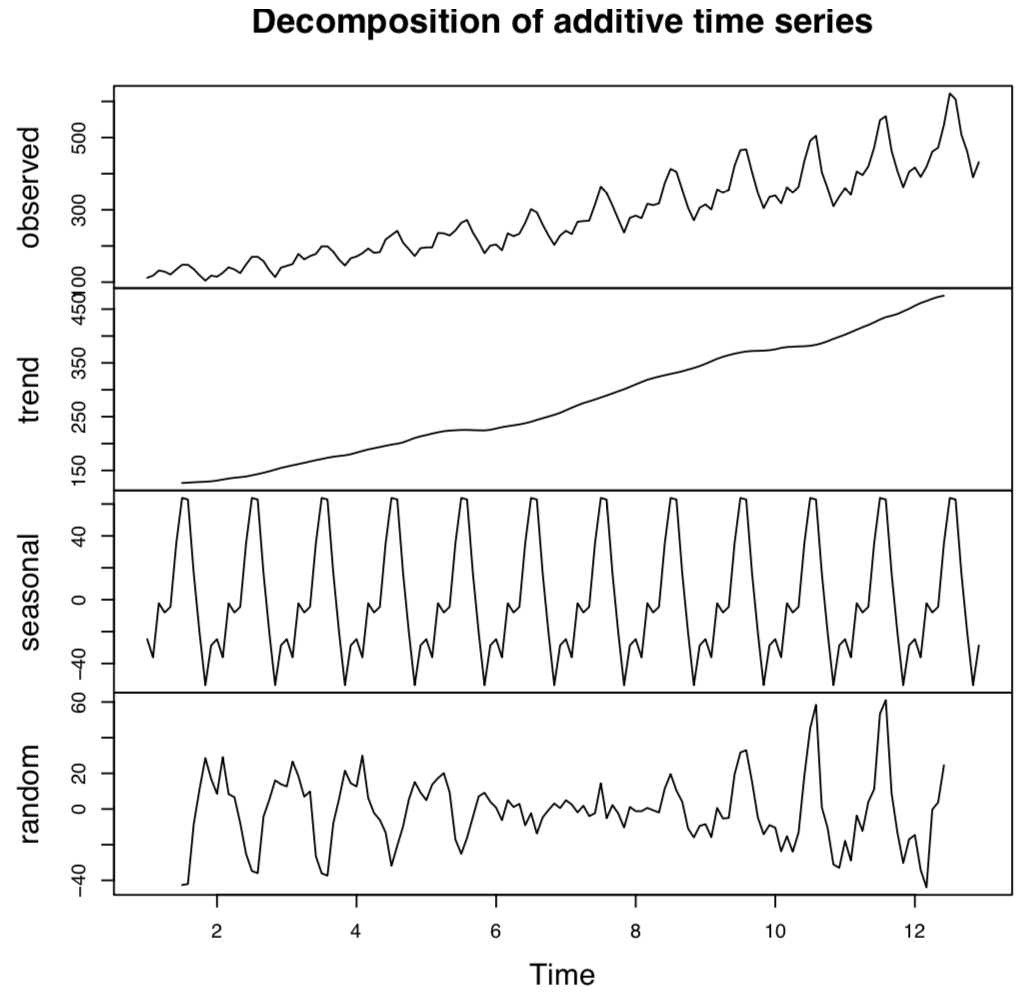

Time series decomposition is a better way of understanding the data in hand. Decomposing the model creates an abstract model that can be used for generalization of the data. Decomposition involves identifying trends and seasonal, cyclical, and irregular components of the data. Making sense of data with these components is the systematic type of modeling.

In the following section, we will look at these recurring properties and how they help analyze time series data.

We have discussed moving averages with respect to time series before. The level can be defined as the average or mean of a bunch of time series data points.

Values of data points in a time series keep either decreasing or increasing with time. They may also follow a cyclic pattern. Such an increase or decrease in data point values are known as the trend of the data.

The values of data point increases or decreases are more periodic, and such patterns are called seasonality. An example of this behavior could be a toy store, where there is an increase and decrease in the amount of toys sold, but in the Thanksgiving season in November, every year there is a spike in sales that is unlike the increase or decrease seen rest of the year.

These are random increases or decreases of values in the series. We will be generally dealing with the preceding systematic components in the form of additive models, where additive models can be defined as the sum of level, trend, seasonality, and noise. The other type is called the multiplicative model, where the components are products of each other.

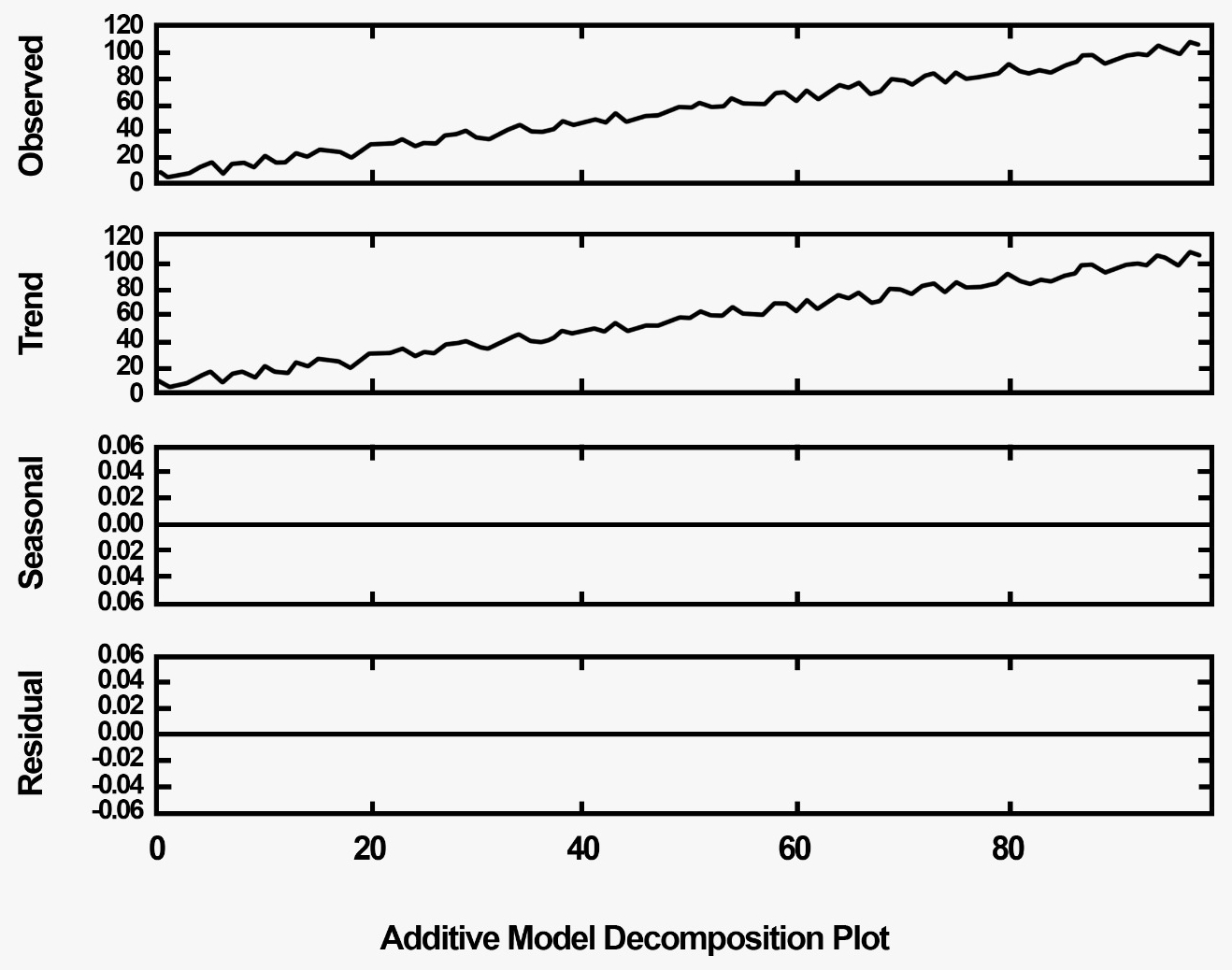

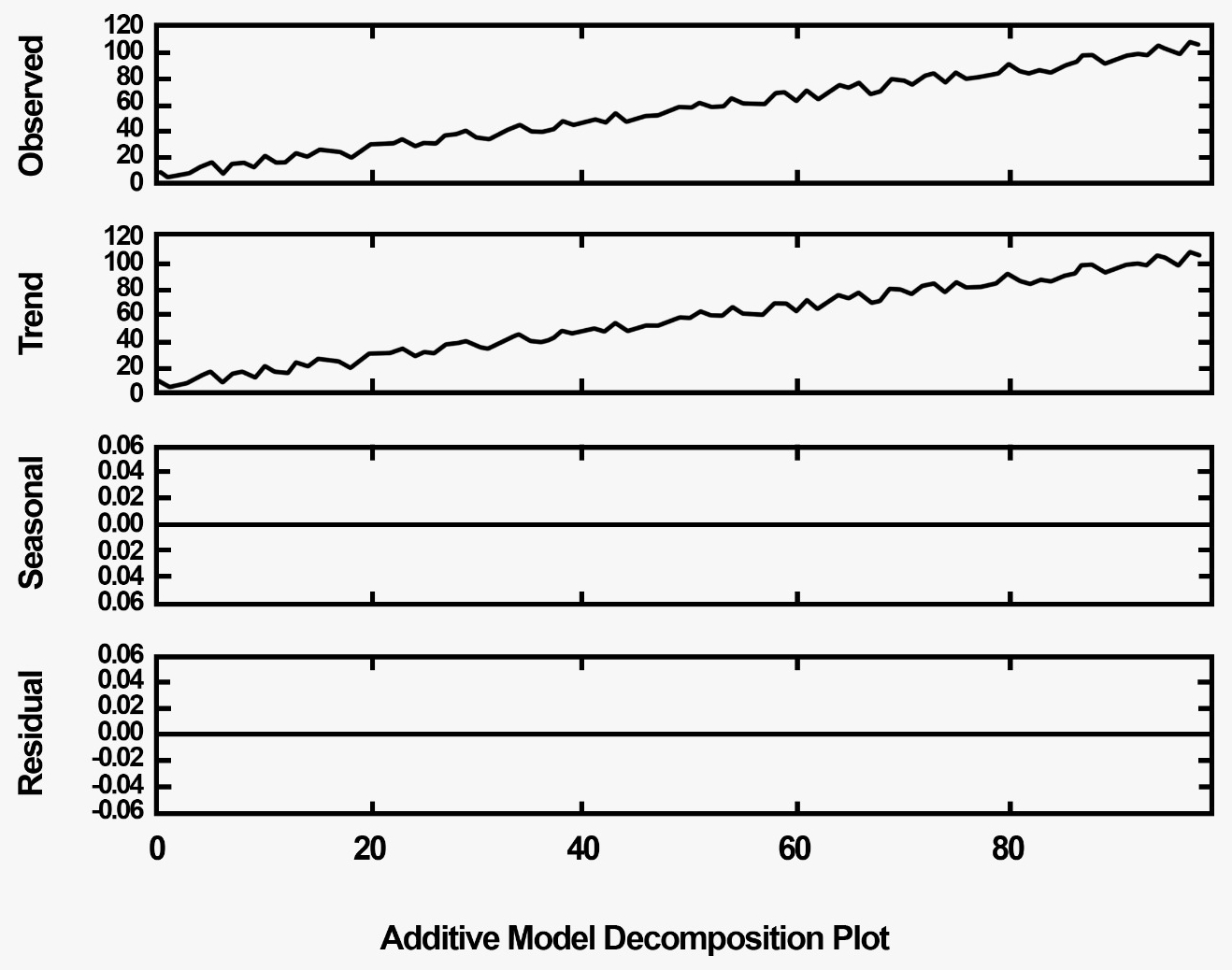

The following graphs help to distinguish between additive and multiplicative models. This graph shows the additive model:

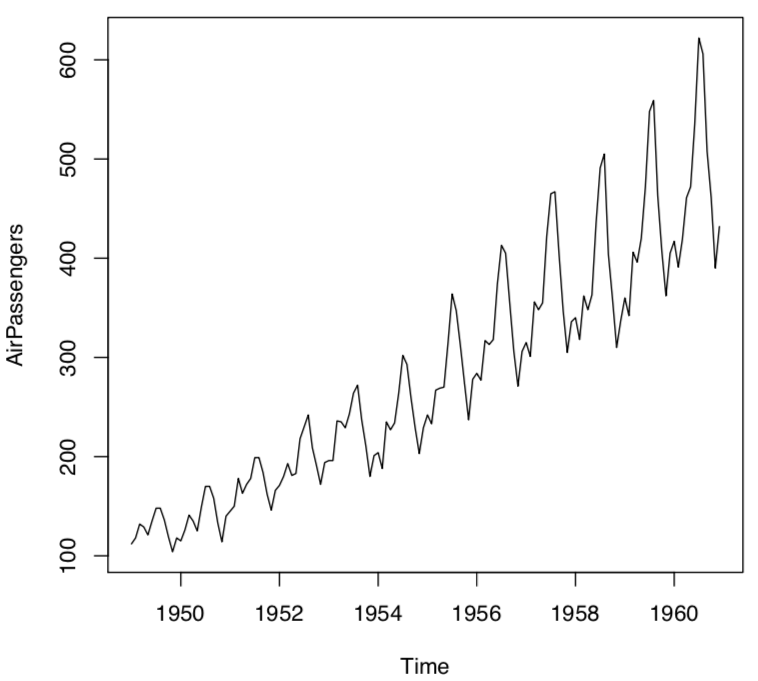

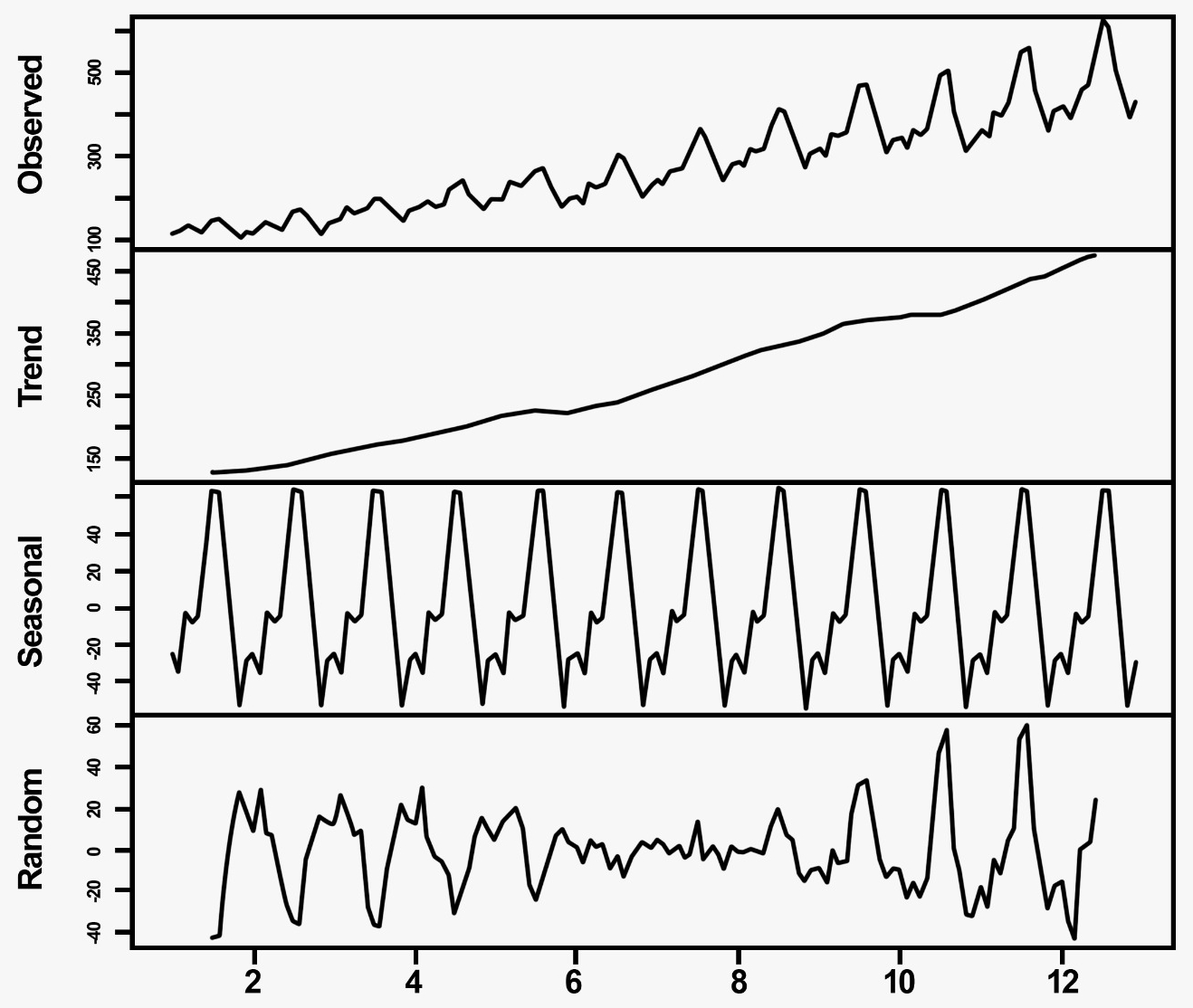

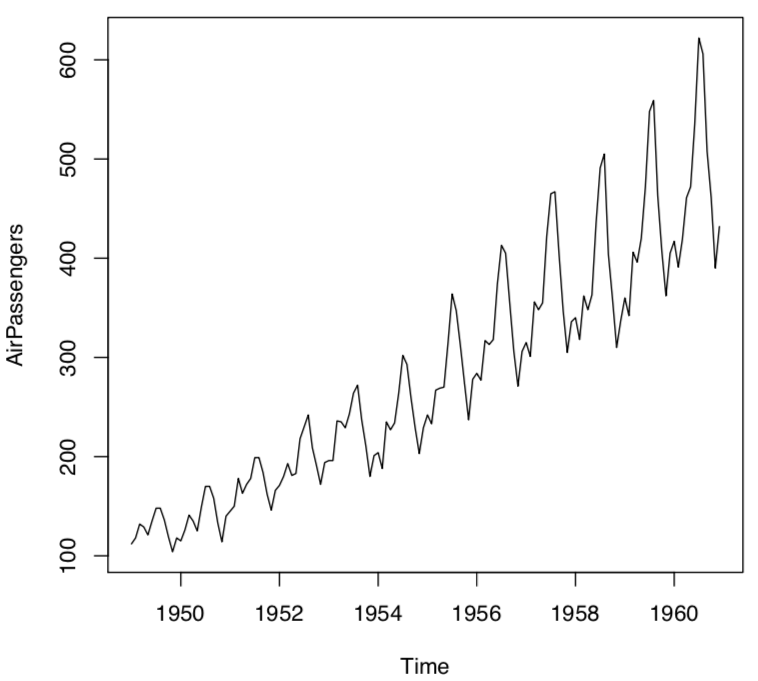

Since data decomposition has a major role in data analyzing, we understand these different components by using pandas inbuilt dataset that is the "International airline passengers: monthly totals in thousands, Jan 49 – Dec 60" dataset. The dataset contains a total of 144 observations of sales from the period of 1949 to 1960 for Box and Jenkins.

Let's import and plot the data:

from pandas import Series

from matplotlib import pyplot

airline = Series.from_csv('/path/to/file/airline_data.csv', header=0)

airline.plot()

pyplot.show()

The following graph shows how there is a seasonality in data and a subsequent increase in the height(amplitude) of the graph as the years have progressed:

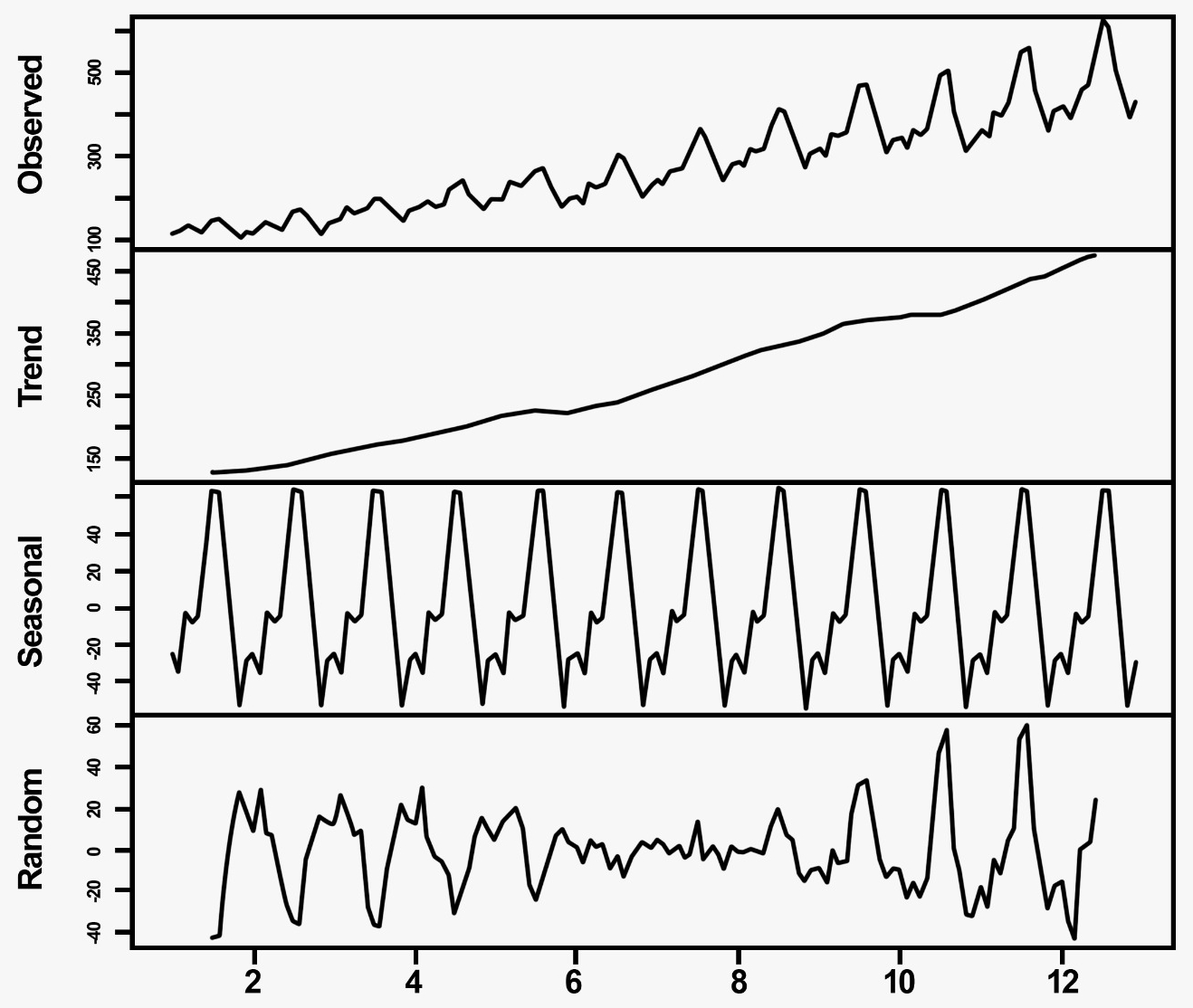

We can mathematically compute the trend and the seasonality for the preceding graph with an additive model as shown:

from pandas import Series

from matplotlib import pyplot

from statsmodels.tsa.seasonal import seasonal_decompose

airline = Series.from_csv('/path/to/file/airline_data.csv', header=0)

result = seasonal_decompose(airline, model='additive')

result.plot()

pyplot.show()

The output for the preceding code is as shown follows:

The preceding graph can be interpreted as follows:

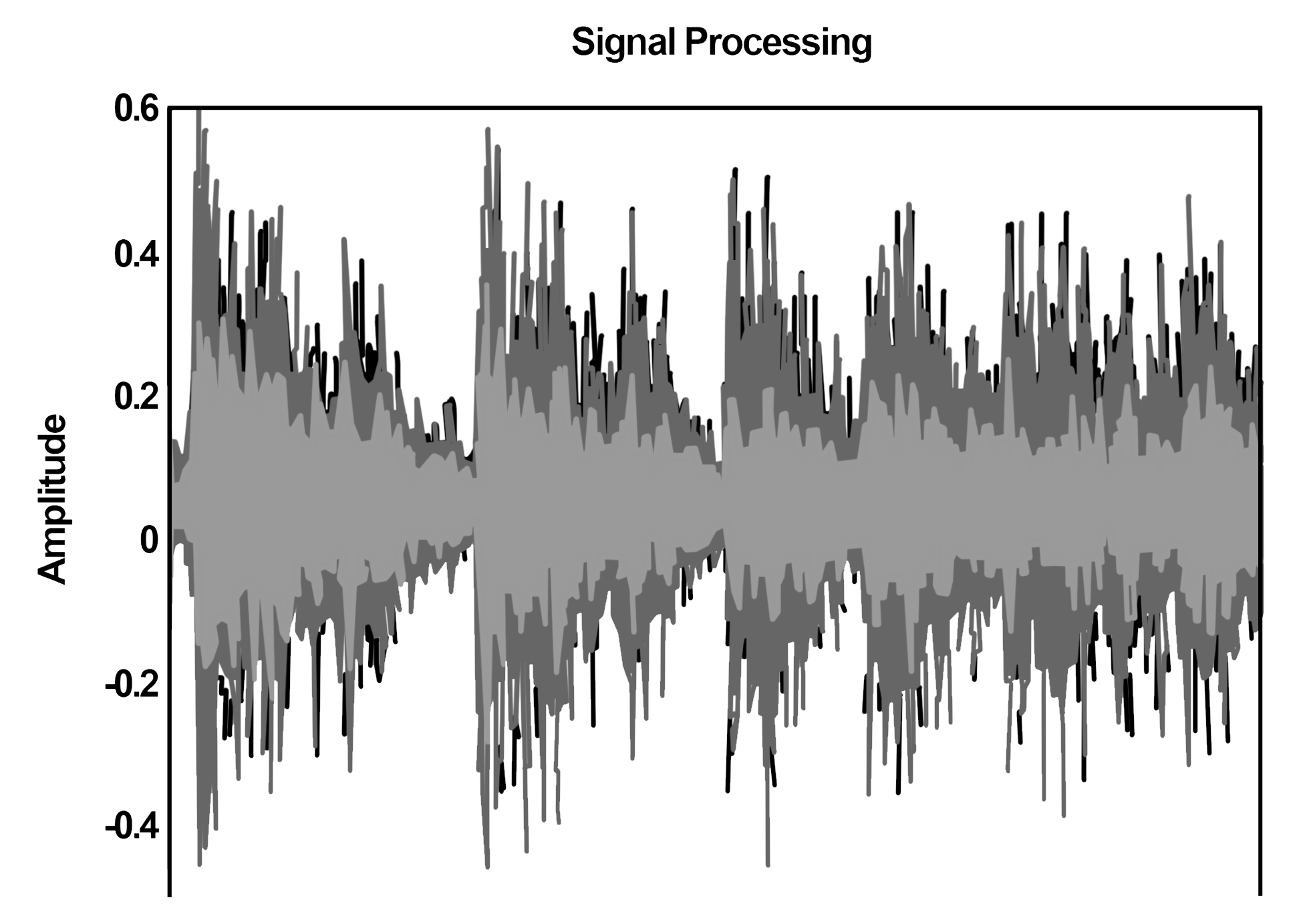

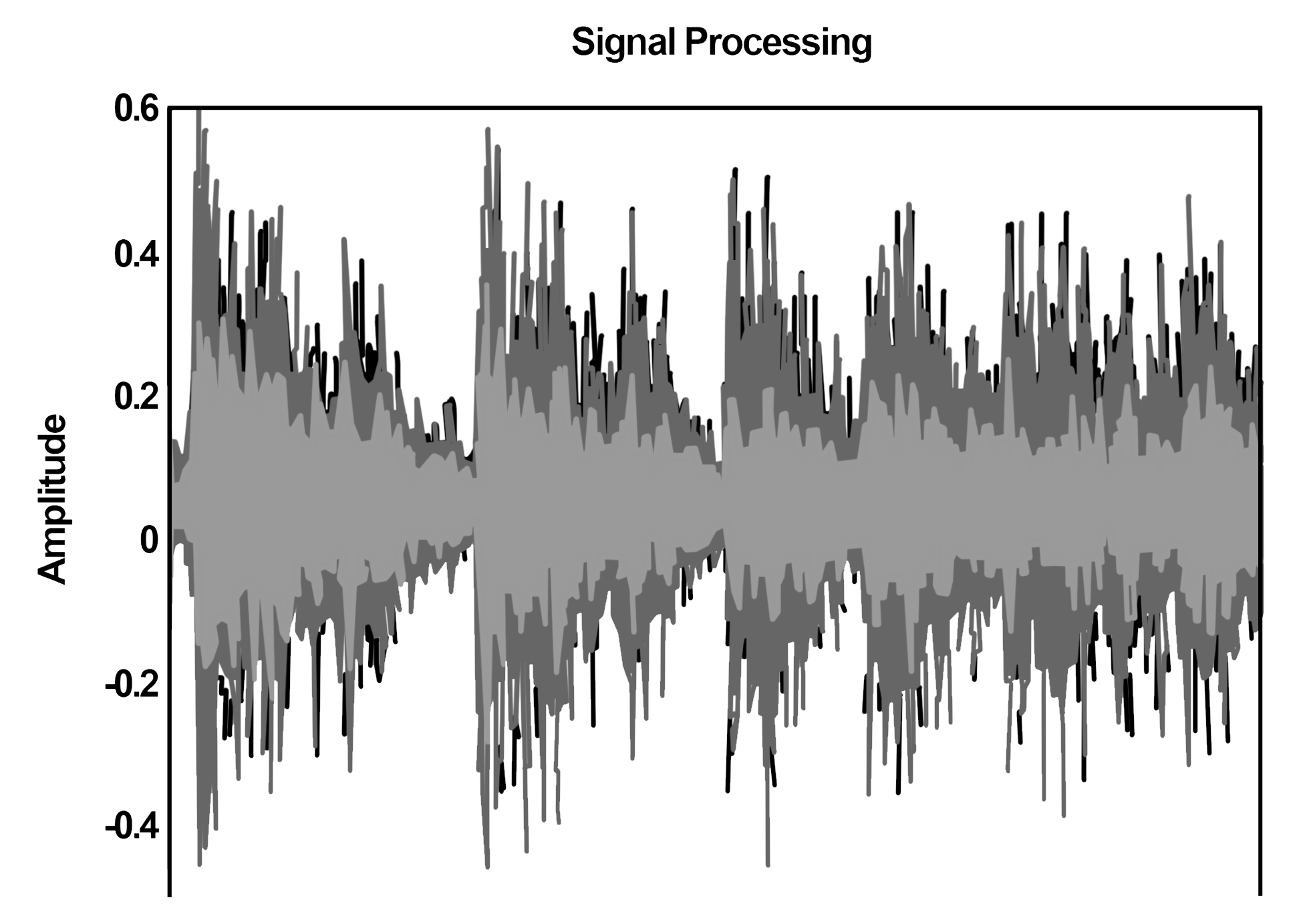

In the Signal processing section, we will discuss the different fields where time series are utilized to extract meaningful information from very large datasets. Be it social media analysis, click stream trends, or system log generations, time series can be used to mine any data that has a similar time-sensitive approach to data collection and storage.

Digital signal processing uses time series analysis to identify a signal from a mixture of noise and signals. Signal processing uses various methods to perform this identification, like smoothing, correlation, convolution, and so on. Time series helps measure deviations from the stationary behaviors of signals. These drifts or deviations are the noise, as follows:

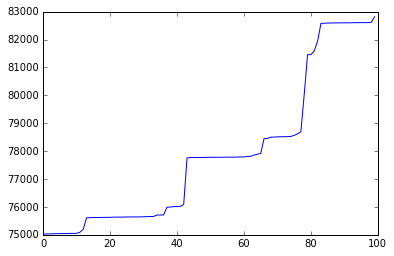

Stock market predictions are yet another use case for time series analysis. Investors can make an educated guess about stocks by analyzing data. Though non-mathematical components like the history of the company do play a art in stock market predictions, they largely depend on the historic stock market trends. We can do a trend analysis of the historic trade-in prices of different stocks and use predictive analytics to predict future prices. Such analytics need data points, that is, stock prices at each hour over a trading period. Quantitative analysts and trading algorithms make investment decisions using these data points by performing time series analysis.

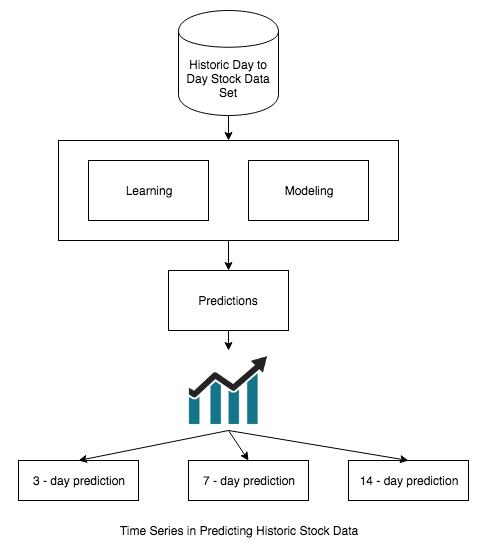

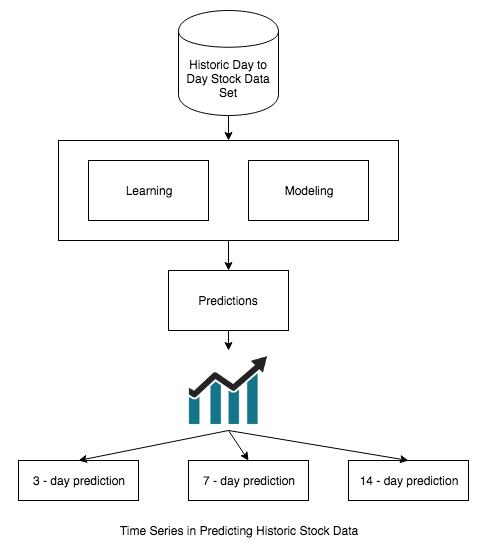

The following diagram shows a time series using historic stock data to make predictions:

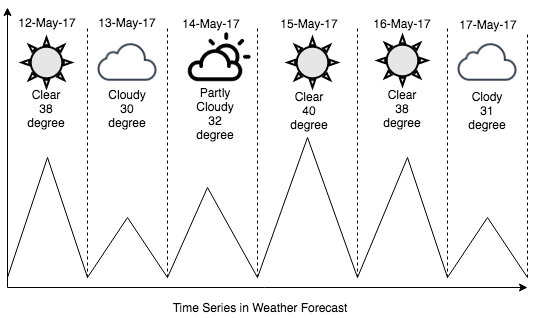

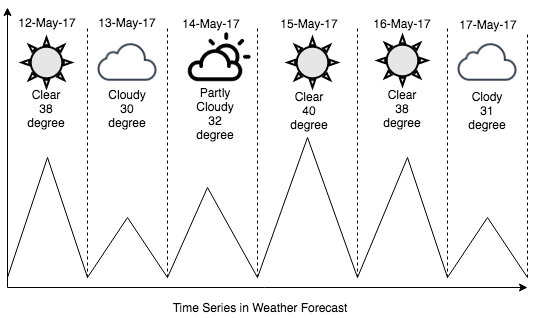

Time series analysis is a well-used process in the field of meteorology. Temperature data points obtained over a period of time help to detect the nature of possible climate changes. They consider seasonality in the data to predict weather changes like storms, hurricanes, or blizzards and then adapt precautions to mitigate the harmful side-effects.

The following shows a time series in a weather forecast:

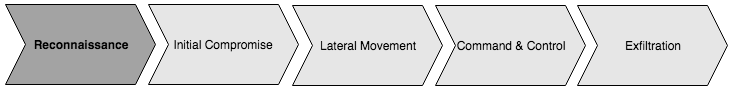

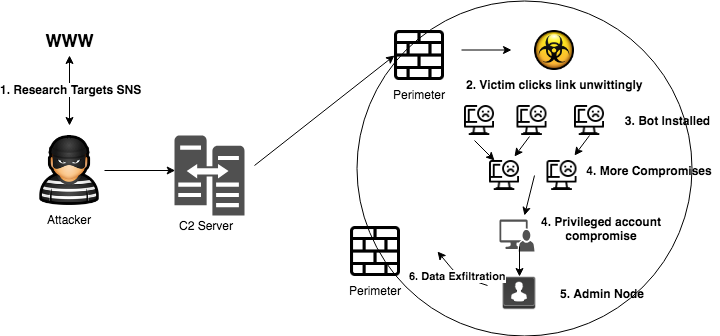

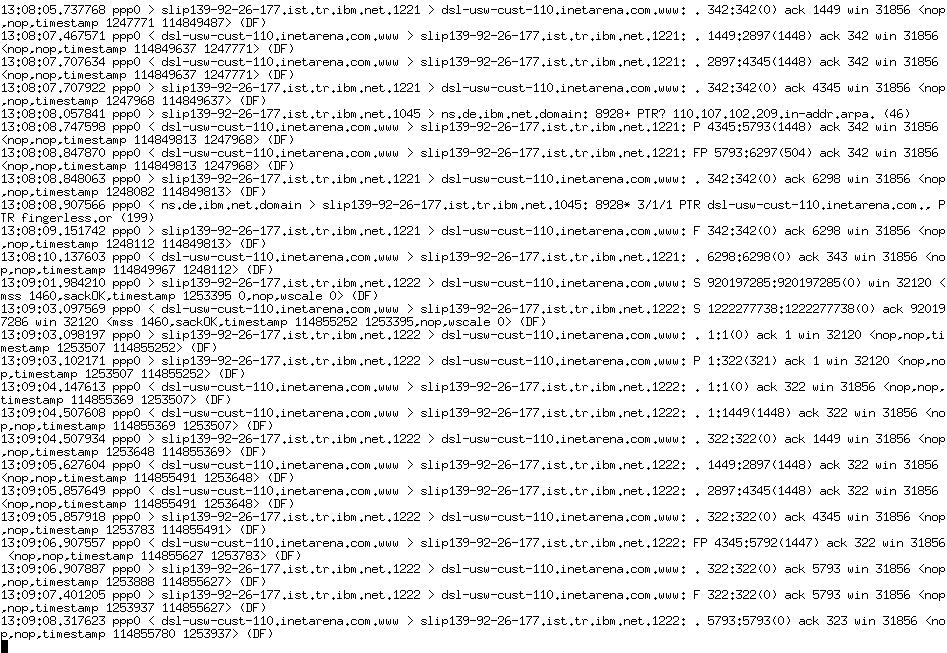

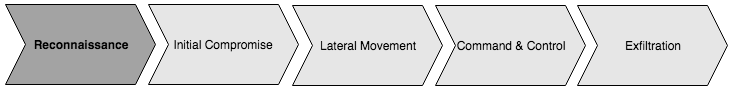

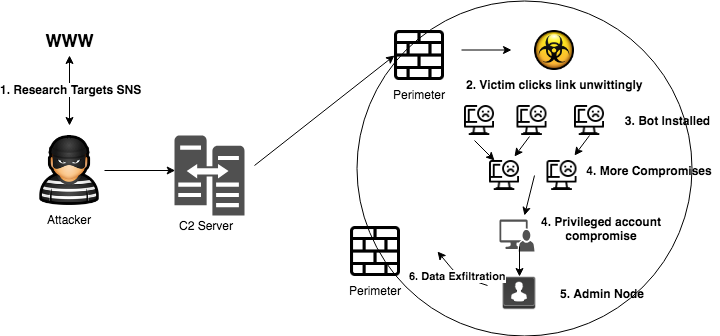

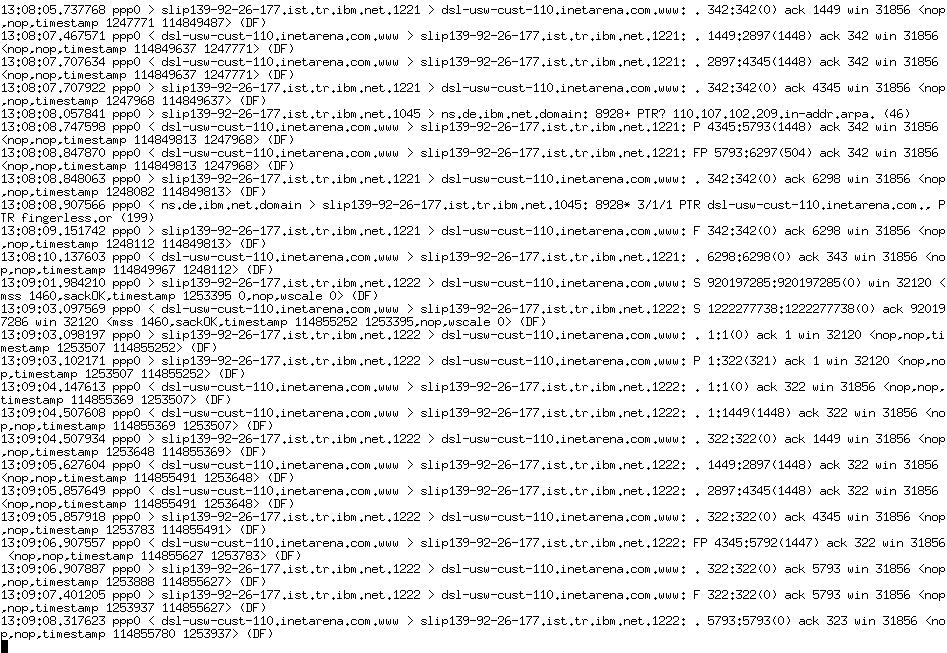

We can use time series concepts to detect early signs of malware compromise or a cyber attack against a system. In the earliest phase of the attack, the malware just sniffs through the system looking for vulnerabilities. The malware goes looking for loosely open ports and peripherals, thus sniffing information about the system. These early stages of cyber attack are very similar to what the military does when it surveys a new region, looking for enemy activities. This stage in a cyber attack is called the Reconnaissance.

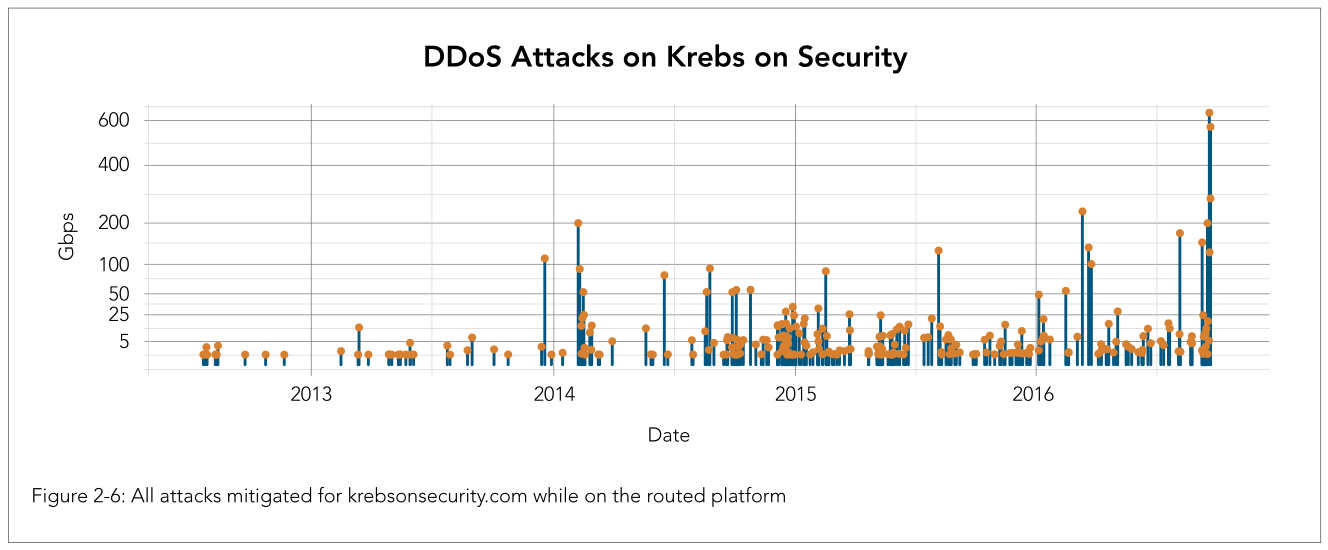

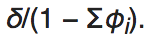

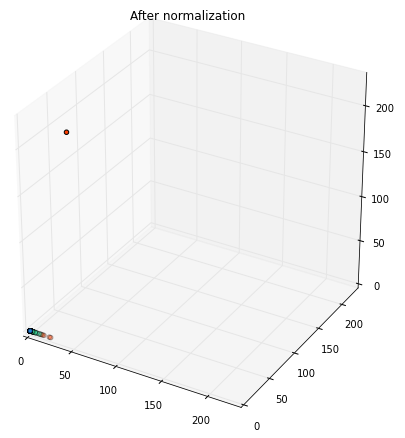

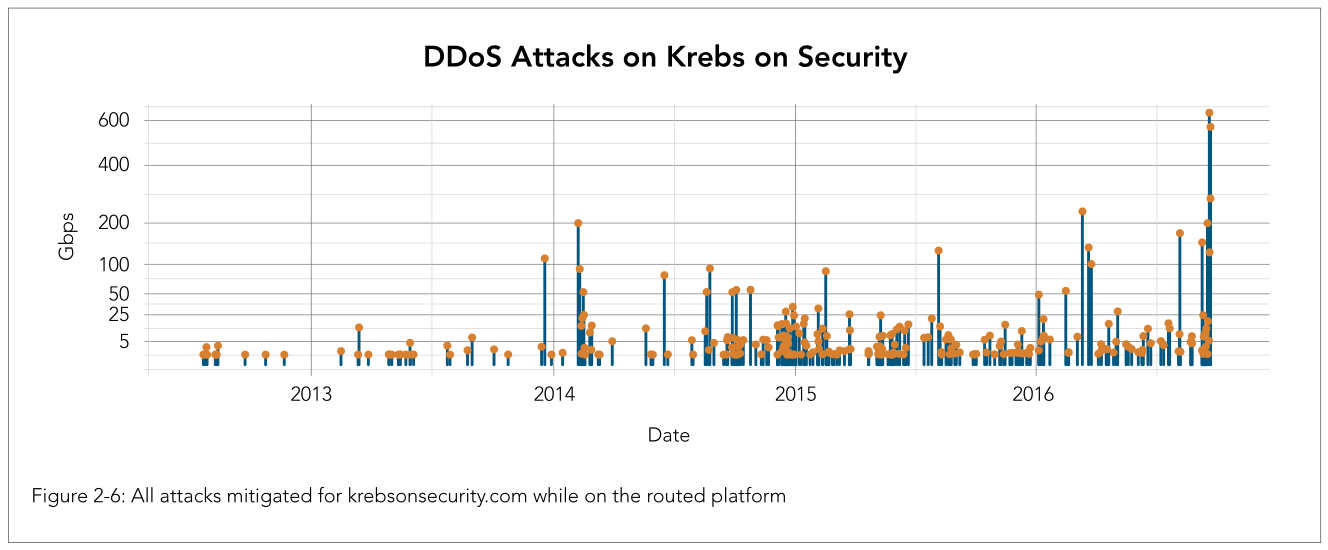

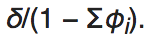

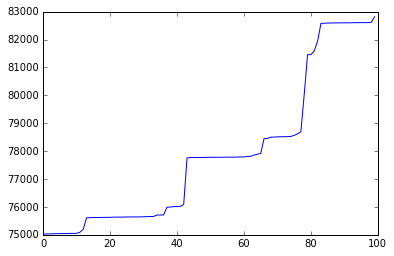

Computer attacks interrupt day-to-day services and cause data losses and network interruption. Time series analyses are popular machine learning methods that help to quantitatively detect anomalies or outliers in data, by either data fitting or forecasting. Time series analysis helps thwarting compromises and keep information loss to a minimum. The following graph shows the attacks mitigated on a routed platform:

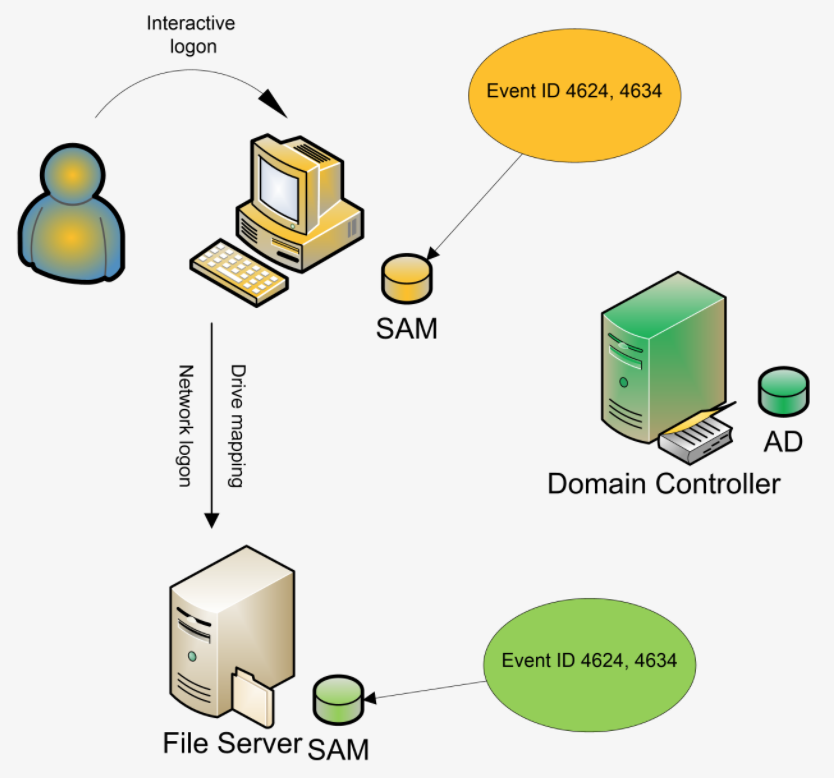

Time series analysis can be used to detect attack attempts, like failed logins, using a time series model. Plotting login attempts identifies spikes (/) in failed logins. Such spikes are indicative of account takeover (ATO).

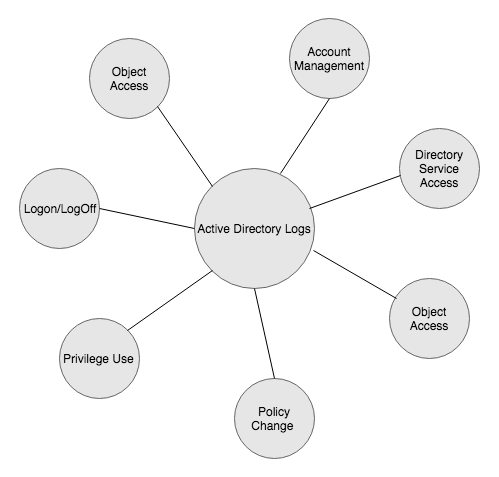

Time series identify another cyber security use case—data exfiltration is the process in which the unauthorized transfer of data takes place from a computer system to a malicious location. Time series can identify huge network data packets being transported out of the network. Data exfiltration could be because of either an outsider compromise or an insider threat. In a later section of the chapter, we will use ensemble learning methods to identify the source of the attack.

We will learn the details of the attack in the next section. The goal of this chapter is to be able to detect reconnaissance so that we are able to prevent the system being compromised in the early stages and keep the loss of information to a minimum.

Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) is a cybersecurity menace which disrupts online services by sending an overwhelming amount of network traffic. These attacks are manually started with botnets that flood the target network. These attacks could have either of the following characteristics:

Time series analysis helps identify network patterns with respect to time. Such pattern detection is done with the historic monitoring of network traffic data. It helps to identify attacks like DDoS. These attacks can be very critical if implemented. Baselining the regular traffic of a network and then overlaying the network with a compromised activity on top of it will help to detect deviations from the normal.

We will be analyzing this use case and will choose a machine learning model that will help detect such DDoS attacks before they crash the entire network.

We will work with a dataset that compromises traffic received by a website, say, donotddos.com. We will analyze 30 days of historic network traffic data from this website and detect whether the current traffic being received by the website is a part of any DDoS attack or not.

Before we go into the details of this use case we will analyze the datatime data type of Python since it will form the building block of any time series model.

This section has some short exercises to illustrate the features of time series elements:

from datetime import datetime

timestamp_now = datetime.now()

datetime(2018, 3, 14, 0, 10, 2, 17534)

By executing the preceding code you'll get the following output:

datetime.datetime(2018, 3, 14, 0, 10, 2, 17534)

time_difference = datetime(2018,3,14) - datetime(2015,2,13,0,59)

datetime.timedelta(1124, 82860)

time_difference.days = 1124

time_difference.seconds = 82860

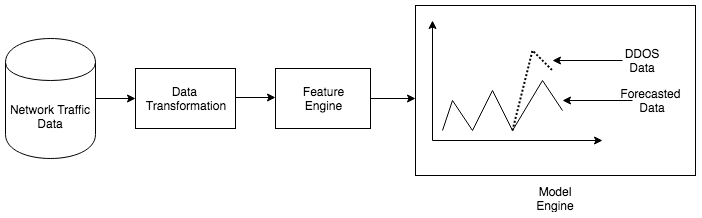

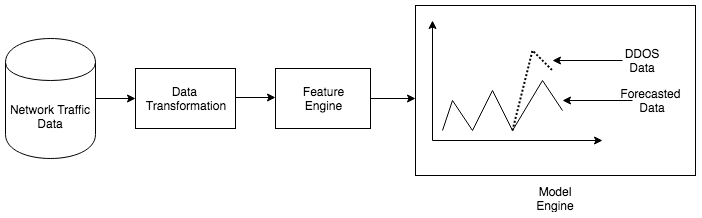

The use case undergoes the following stages:

The following diagram sums up the entire procedure:

We import the relevant Python packages that will be needed for the visualization of this use case, as follows:

import pandas as p import seaborn as sb import numpy as n %matplotlib inline import matplotlib.pyplot as pl

We have data in a CSV file, a text file separated by commas. While importing the data we also identify the headers in the data. Since we deal with packet capture data from the network, the columns captured are as follows:

pdata_frame = pd.read_csv("path/to/file.csv", sep=',', index_col = 'Sl Num', names = ["Sl Num", "Time", "Source", "Destination","Volume", "Protocol"])

Let's dump the first few lines of the data frame and have a look at the data. The following code displays the first 10 lines of the packet capture dataset:

pdata_frame.head(n=9)

The output of the preceding is as follows:

| Sl Num | Time | Source | Destination |

Volume

|

Protocol |

| 1 | 1521039662 | 192.168.0.1 | igmp.mcast.net | 5 | IGMP |

| 2 | 1521039663 | 192.168.0.2 | 239.255.255.250 | 1 | IGMP |

| 3 | 1521039666 | 192.168.0.2 | 192.168.10.1 | 2 | UDP |

| 4 | 1521039669 | 192.168.10.2 | 192.168.0.8 | 20 | DNS |

| 5 | 1521039671 | 192.168.10.2 | 192.168.0.8 | 1 | TCP |

| 6 | 1521039673 | 192.168.0.1 | 192.168.0.2 | 1 | TCP |

| 7 | 1521039674 | 192.168.0.2 | 192.168.0.1 | 1 | TCP |

| 8 | 1521039675 | 192.168.0.1 | 192.168.0.2 | 5 | DNS |

| 9 | 1521039676 | 192.168.0.2 | 192.168.10.8 | 2 | DNS |

Our dataset is largely clean so we will directly transform the data into more meaningful forms. For example, the timestamp of the data is in epoch format. Epoch format is alternatively known as Unix or Posix time format. We will convert this to the date-time format that we have previously discussed, as shown in the following:

import time

time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(1521388078))

Out: '2018-03-18 21:17:58'

We perform the preceding operation on the Time column, add it to a new column, and call it Newtime:

pdata_frame['Newtime'] = pdata_frame['Time'].apply(lambda x: time.strftime('%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S', time.localtime(float(x))))

Once we have transformed the data to a more readable format, we look at the other data columns. Since the other columns look pretty cleansed and transformed, we will leave them as is. The volume column is the next data that we will look into. We aggregate volume in the same way by the hour and plot it with the following code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.scatter(pdata_frame['time'],pdata_frame['volume'])

plt.show() # Depending on whether you use IPython or interactive mode, etc.

To carry out any further analysis on the data, we need to aggregate the data to generate features.

We extract the following features:

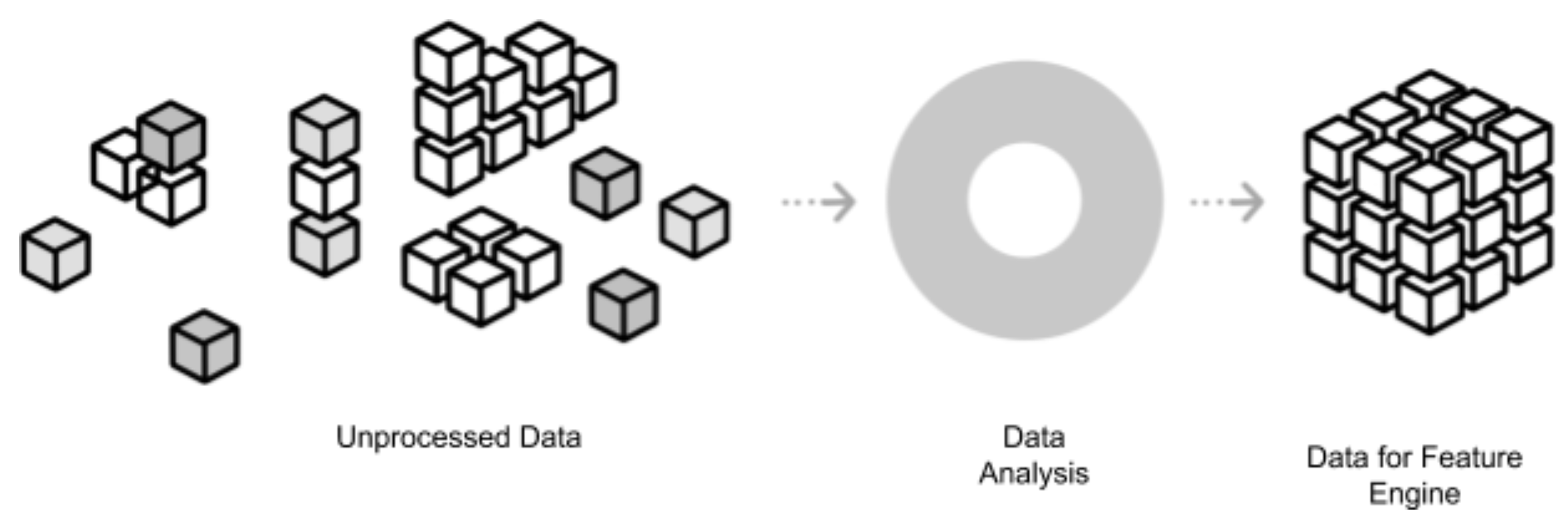

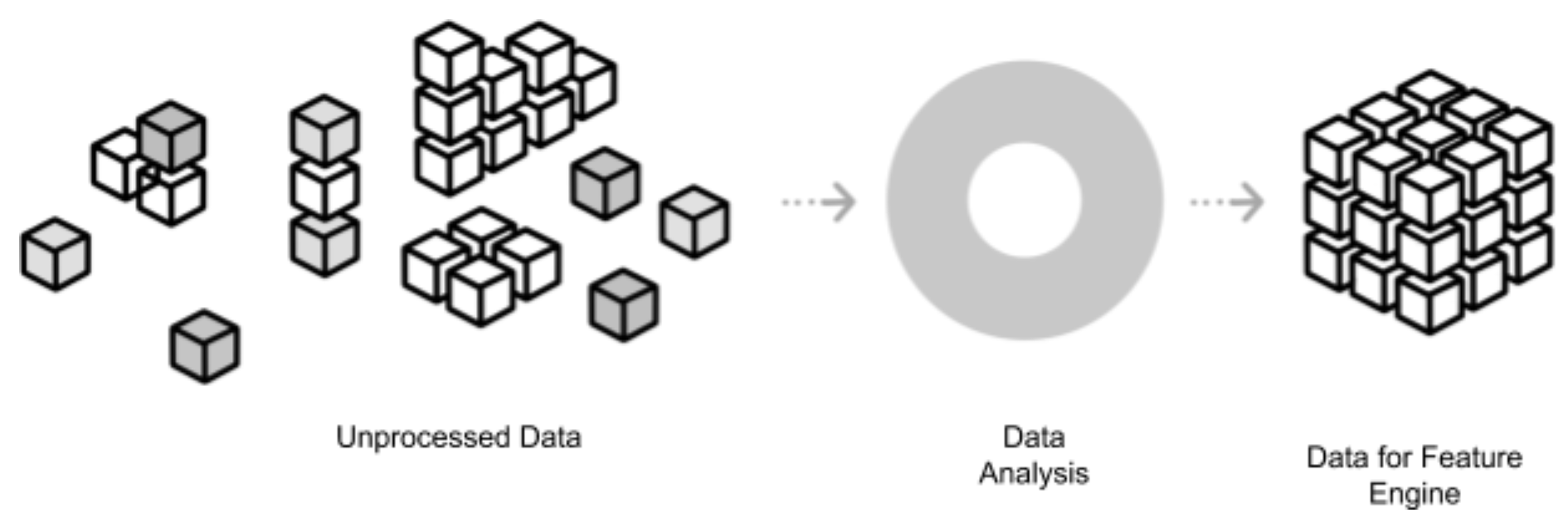

The following image shows how unprocessed data changes to data for the feature engine using data analysis:

Since our computations are done per minute, we round off the time to the nearest minute, as shown in the following code:

_time = pdata_frame['Time'] #Time column of the data frame

edited_time = []

for row in pdata_frame.rows:

arr = _time.split(':')

time_till_mins = str(arr[0]) + str(arr[1])

edited_time.append(time_till_mins) # the rounded off time

source = pdata_frame['Source'] # source address

The output of the preceding code is the time rounded off to the nearest minute, that is, 2018-03-18 21:17:58 which will become 2018-03-18 21:17:00 as shown:

'2018-03-18 21:17:00'

'2018-03-18 21:18:00'

'2018-03-18 21:19:00'

'2018-03-18 21:20:00'

'2018-03-19 21:17:00'

We count the number of connections established per minute for a particular source by iterating through the time array for a given source:

connection_count = {} # dictionary that stores count of connections per minute

for s in source:

for x in edited_time :

if x in connection_count :

value = connection_count[x]

value = value + 1

connection_count[x] = value

else:

connection_count[x] = 1

new_count_df #count # date #source

The connection_count dictionary gives the number of connections. The output of the preceding code looks like:

| Time | Source | Number of Connections |

| 2018-03-18 21:17:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 5 |

| 2018-03-18 21:18:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 1 |

| 2018-03-18 21:19:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 10 |

| 2018-03-18 21:17:00 | 192.168.0.3 | 2 |

| 2018-03-18 21:20:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 3 |

| 2018-03-19 22:17:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 3 |

| 2018-03-19 22:19:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 1 |

| 2018-03-19 22:22:00 | 192.168.0.2 | 1 |

| 2018-03-19 21:17:00 | 192.168.0.3 | 20 |

We will decompose the data with the following code to look for trends and seasonality in the data. Decomposition of the data promotes more effective detection of an anomalous behavior, a DDoS attack, as shown in the following code:

from statsmodels.tsa.seasonal import seasonal_decompose

result = seasonal_decompose(new_count_df, model='additive')

result.plot()

pyplot.show()

The data generates a graph as follows; we are able to recognize the seasonality and trend of the data in general:

Next we find the ACF function for the data to understand the autocorrelation among the variables, with the following piece of code:

from matplotlib import pyplot

from pandas.tools.plotting import autocorrelation_plot

autocorrelation_plot(new_count_df)

pyplot.show()

Now that we have identified a seasonality, the trend in the network data will baseline the data by fitting to a stochastic model. We have already defined systematic parameters, and we will apply them next.

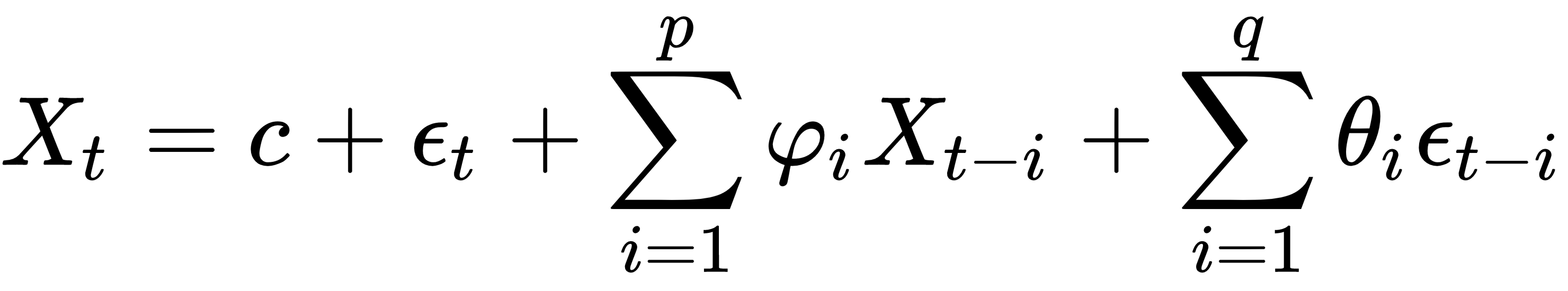

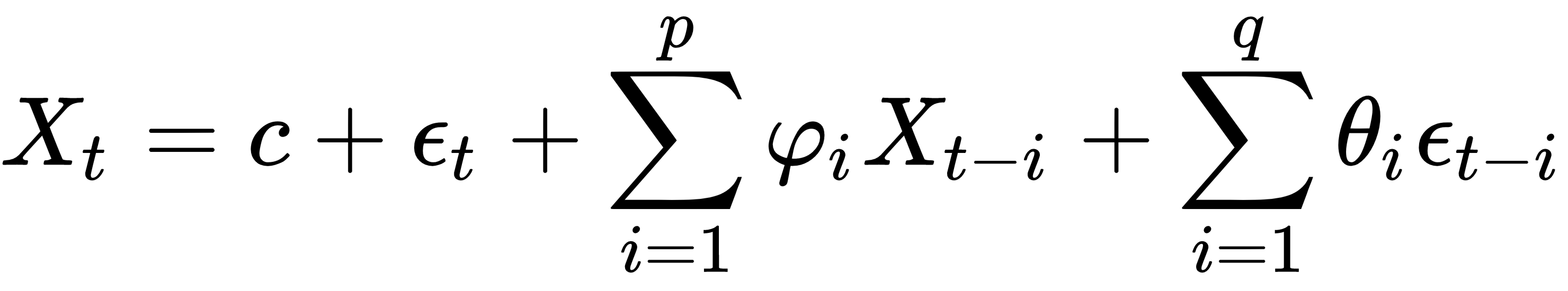

This is a weak stochastic stationary process, such that, when provided with a time series Xt, ARMA helps to forecast future values with respect to current values. ARMA consists of two actions:

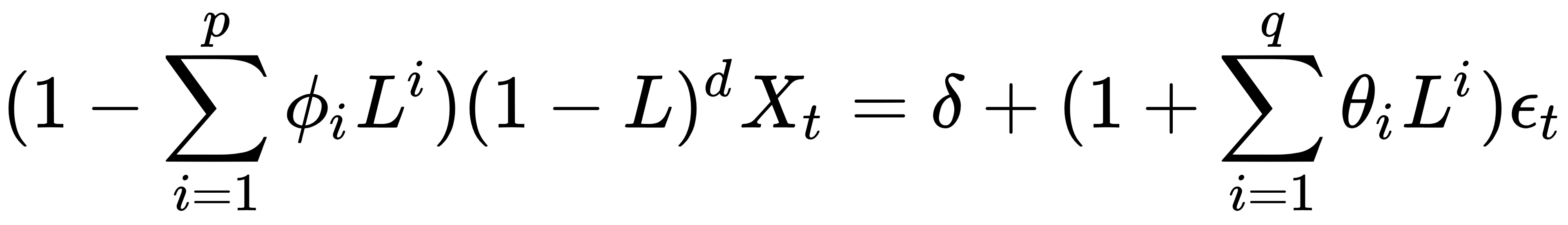

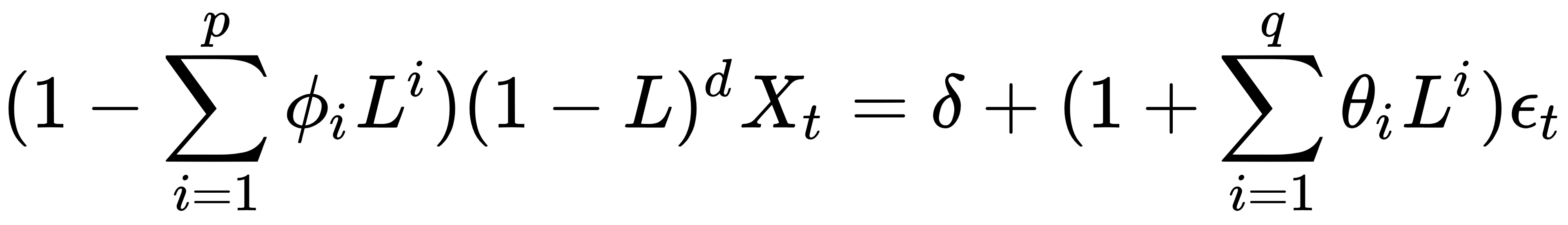

ARIMA is a generalized version of ARMA. It helps us to understand the data or make predictions. This model can be applied to non-stationary sets and hence requires an initial differential step. ARIMA can be either seasonal or non-seasonal. ARIMA can be defined with (p,d,q) where:

Where:

This is a generalized ARIMA model that allows non-integer values of the differencing parameter. It is in time series models with a long memory.

Now that we have discussed the details of each of these stochastic models, we will fit the model with the baseline network data. We will use the stats models library for the ARIMA stochastic model. We will pass the p, d, q values for the ARIMA model. The lag value for autoregression is set to 10, the difference in order is set to 1, and the moving average is set to 0. We use the fit function to fit the training/baseline data. The fitting model is shown as follows:

# fitting the model

model = ARIMA(new_count_df, order=(10,1,0))

fitted_model = model.fit(disp=0)

print(fitted_model.summary())

The preceding is the model that is fitted in the entire training set, and we can use it to find the residuals in the data. This method helps us to understand data better, but is not used in forecasts. To find the residuals in the data, we can do the following in Python:

# plot residual errors

residuals_train_data = DataFrame(fitted_model.resid)

residuals_train_data.plot()

pyplot.show()

Finally we will use the predict() function to predict what the current pattern in data should be like. Thus we bring in our current data, which supposedly contains the data from the DDoS attack:

from statsmodels.tsa.arima_model import ARIMA

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

ddos_predictions = list()

history = new_count_df

for ddos in range(len(ddos_data)):

model = ARIMA(history, order=(10,1,0))

fitted_model = model.fit(disp=0)

output =fitted_model.forecast()

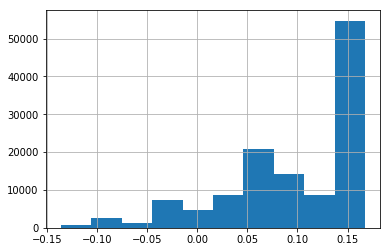

We can plot the error that is the difference between the forecasted DDoS free network data and the data with the network, by computing the mean square error between them, as shown in the following code:

pred = output[0]

ddos_predictions.append(pred)

error = mean_squared_error(ddos_data,ddos_predictions)

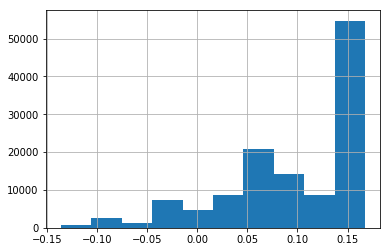

The output of the preceding code is the following plot where the dense line is the forecasted data and the dotted line is the data from the DDoS attack.

Ensemble learning methods are used to improve performance by taking the cumulative results from multiple models to make a prediction. Ensemble models overcome the problem of overfitting by considering outputs of multiple models. This helps in overlooking modeling errors from any one model.

Ensemble learning can be a problem for time series models because every data point has a time dependency. However, if we choose to look at the data as a whole, we can overlook time dependency components. Time dependency components are conventional ensemble methods like bagging, boosting, random forests, and so on.

Ensembling of models to derive the best model performance can happen in many ways.

In this ensemble method, the mean of prediction results is considered from the multiple number of predictions that have been made. Here, the mean of the ensemble is dependent on the choice of ensemble; hence, their value changes from one model to another:

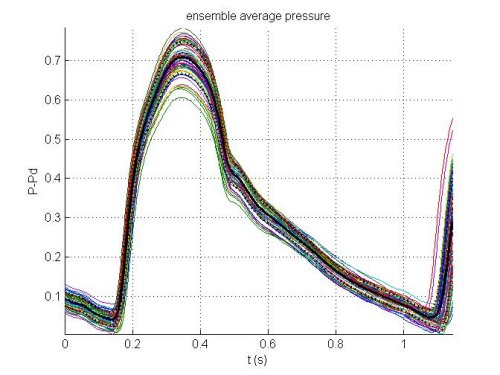

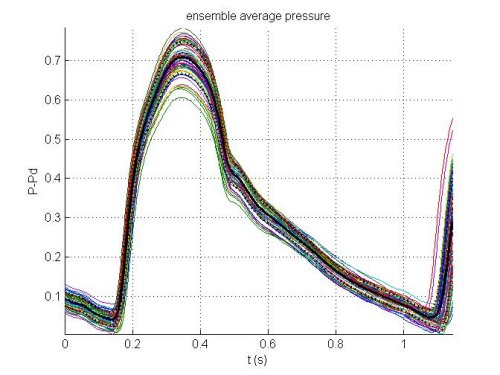

In this ensemble method, the forecast that gets unanimously voted by multiple models wins and is considered as the end result. For example, while classifying an email as spam, if at least three out of four emails classify a document as spam, then it is considered as spam.

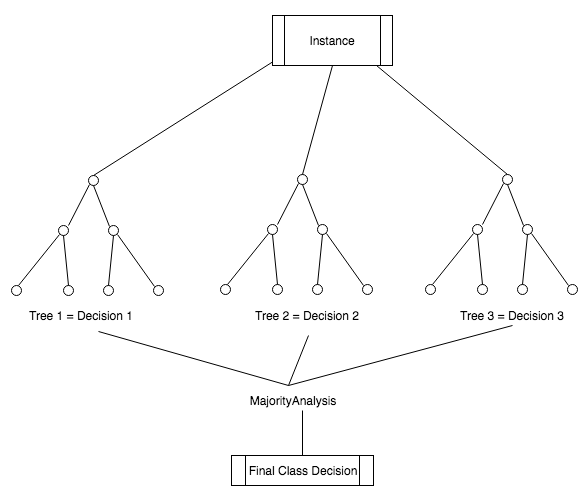

The following diagram shows the classification by majority vote:

In this ensemble method, weights are assigned to multiple models and, while taking the average of each of these predictions, the weight is also considered. In this method, the models that have more weight receive more preference.