As we said, most of the time you can get by with the default security the system gives you. But there are always exceptions, particularly for system administrators. To take a simple example, suppose you are creating a directory under /home for a new user. You have to create everything as root, but when you’re done you have to change the ownership to the user; otherwise, that user won’t be able to use the files! (Fortunately, if you use the adduser command discussed earlier in "Creating Accounts,” it takes care of ownership for you.)

Similarly, certain utilities and programs such as the MySQL database and News have their own users. No one ever logs in as mysql or News, but those users and groups must exist so that the utilities can do their job in a secure manner. In general, the last step when installing software is usually to change the owner, group, and permissions as the documentation tells you to do.

The chown command changes the owner of a file, and the chgrp command changes the group. On Linux, only root can use chown for changing ownership of a file, but any user can change the group to another group to which he belongs.

So after installing some software named sampsoft, you might change both the owner and the group to bin by executing:

#chown bin sampsoft#chgrp bin sampsoft

You could also do this in one step by using the dot notation:

# chown bin.bin sampsoftThe syntax for changing permissions is more complicated. The permissions can also be called the file’s “mode,” and the command that changes permissions is chmod. Let’s start our exploration of this command through a simple example. Say you’ve written a neat program in Perl or Tcl named header, and you want to be able to execute it. You would type the following command:

$ chmod +x headerThe plus sign means “add a permission,” and the x indicates which permission to add.

If you want to remove execute permission, use a minus sign in place of a plus:

$ chmod -x headerThis command assigns permissions to all levels: user, group, and other. Let’s say that you are secretly into software hoarding and don’t want anybody to use the command but yourself. No, that’s too cruel—let’s say instead that you think the script is buggy and want to protect other people from hurting themselves until you’ve exercised it. You can assign execute permission just to yourself through the command:

$ chmod u+x headerWhatever goes before the plus sign is the level of permission,

and whatever goes after is the type of permission. User permission

(for yourself) is u, group permission is g, and other is o. So to assign permission to both yourself

and the file’s group, enter:

$ chmod ug+x headerYou can also assign multiple types of permissions:

$ chmod ug+rwx headerYou can learn a few more shortcuts from the chmod manual page in order to impress someone looking over your shoulder, but they don’t offer any functionality besides what we’ve shown you.

As arcane as the syntax of the mode argument may seem, there’s another syntax that is even more complicated. We have to describe it, though, for several reasons. First of all, there are several situations that cannot be covered by the syntax, called symbolic mode , that we’ve just shown. Second, people often use the other syntax, called absolute mode , in their documentation. Third, there are times you may actually find the absolute mode more convenient.

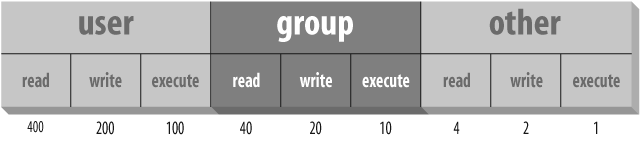

To understand absolute mode, you have to think in terms of bits and octal notation. Don’t worry, it’s not too hard. A typical mode contains three characters, corresponding to the three levels of permission (user, group, and other). These levels are illustrated in Figure 11-2. Within each level, there are three bits corresponding to read, write, and execute permission.

Let’s say you want to give yourself read permission and no permission to anybody else. You want to specify just the bit represented by the number 400. So the chmod command would be:

$ chmod 400 headerTo give read permission to everybody, choose the correct bit from each level: 400 for yourself, 40 for your group, and 4 for other. The full command is:

$ chmod 444 headerThis is like using a mode +r, except that it simultaneously removes any write or execute permission. (To be precise, it’s just like a mode of =r, which we didn’t mention earlier. The equal sign means “assign these rights and no others.”)

To give read and execute permission to everybody, you have to add up the read and execute bits: 400 plus 100 is 500, for instance. So the corresponding command is:

$ chmod 555 headerwhich is the same as =rx. To give someone full access, you would specify that digit as a 7: the sum of 4, 2, and 1.

One final trick: how to set the default mode that is assigned to each file you create (with a text editor, the > redirection operator, and so on). You do so by executing a umask command, or putting one in your shell’s startup file. This file could be called .bashrc, .cshrc, or something else depending on the shell you use (we discussed startup files in Chapter 4).

The umask command takes an argument like the absolute mode in chmod, but the meaning of the bits is inverted. You have to determine the access you want to grant for user, group, and other, and subtract each digit from 7. That gives you a three-digit mask.

For instance, say you want yourself to have all permissions (7), your group to have read and execute permissions (5), and others to have no permissions (0). Subtract each bit from 7 and you get 0 for yourself, 2 for your group, and 7 for other. So the command to put in your startup file is

umask 027

A strange technique, but it works. The chmod command looks at the mask when it interprets your mode; for instance, if you assign execute mode to a file at creation time, it will assign execute permission for you and your group, but will exclude others because the mask doesn’t permit them to have any access.