Helping a group of people coordinate their work or private lives—their calendars and task lists, their notes and address books, and so forth—presents one of the rare opportunities for computers to actually solve a real, everyday problem. Imagine being able to change a meeting by dragging a text box to a new time slot in the calendar application, and having the software system automatically inform all other attendees of the change, ask them whether they still want to attend, and update their own calendars automatically. Such software, which supports groups of people who are interacting, coordinating with each other, and cooperating, is commonly referred to as groupware .

For all but the simplest needs of very small groups, it is usually sensible to store the information that is to be shared or exchanged between the members at a central location on the network. Often a computer is dedicated to this purpose; it is then referred to as a groupware server. Access to this server is managed in different ways by different groupware projects. Most offer access via web browsers. Many also allow users to work with full-fledged client applications such as Kontact or Evolution, which then connect to the server using various protocols to read and manipulate the data stored there. In this context such applications are often referred to as groupware suites.

We first look at what is possible using only client capabilites, without access to a groupware server, and then examine the different server solutions that are available and what addtional benefits they bring.

Thanks to a set of established Internet standards, groupware users can collaborate not only using a single groupware server—within a single organization, for example—but also to a certain extent with partners using different groupware clients and servers on Linux or Windows. This is done by sending email messages that contain the groupware information as attachments back and forth. All the available Linux groupware suites (Kontact, Evolution, and Mozilla) support this, as do proprietary clients on Windows and Mac OS such as MS Outlook or Lotus Notes.

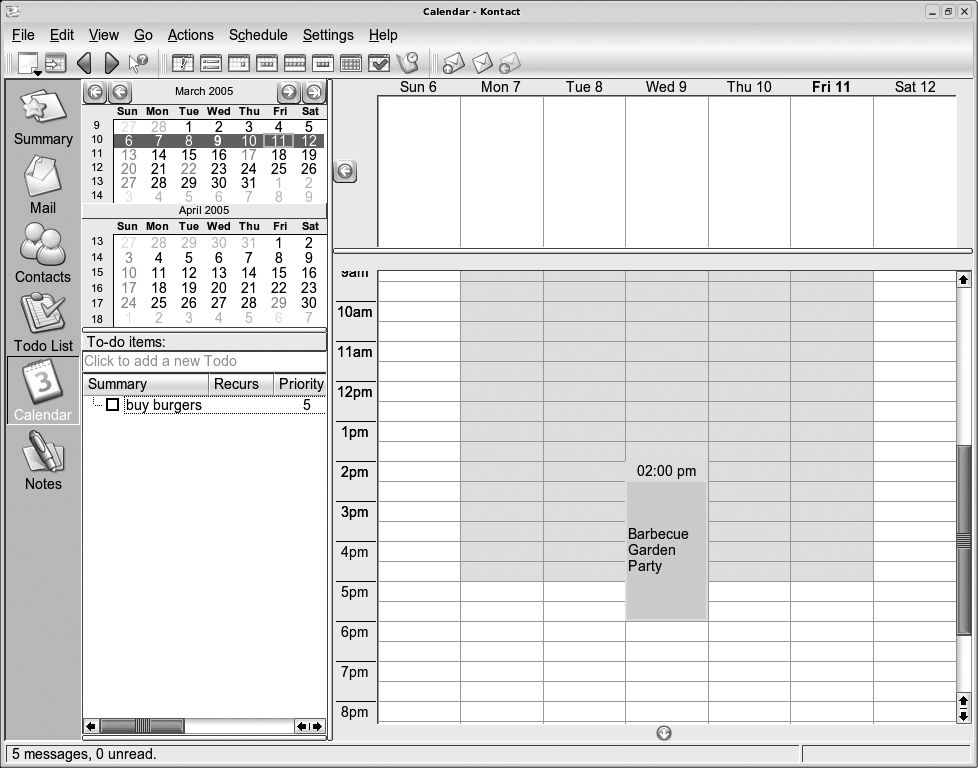

As an example, let’s look at what ensues when you invite your friendly neighbor, who happens to still be running Windows and using MS Outlook, to your barbecue garden party on Wednesday. To do that you open your calendar to the current week and create a new event on Wednesday afternoon. (See Figure 8-46. We use Kontact in this example.) Add your neighbor as an attendee of the event and, since without him the party would be no fun, set his participation to be required. Once you’ve entered all the relevant information and closed the dialog, an email is constructed and sent to the email address of your neighbor. This message consists of a text part with the description of the event and an additional messsage part containing the details of the event in a certain format, which is specified in RFC 2446 and referred to as iTip.

At the receiving end, your neighbor’s Outlook mailer detects the incoming message as an invitation to an event and reads the relevant information from the attachments. One attachment asks your neighbor whether he’ll be able to attend and whether the invitation should be accepted, declined, or accepted tentatively. Since he’s not quite sure that Wednesday might be the night of a sports event he plans to watch, let’s say he chooses to accept the event tentatively. The event is then added to his own calendar inside Outlook and a reply message is constructed and sent, again containing a special iTip attachment.

Once that message makes it back to you, Kontact will inform you that the person you invited has tentatively accepted the invitation, and will enter that information into your calendar. As soon as your neighbor decides to either decline or accept the invitation, an update message will be sent and the status updated accordingly in your calendar upon receipt of that message. Should you decide to delete the event from your calendar, such an update message would in turn be sent to all attendees automatically.

The described mechanisms work not only for events, but also for assigning and sending tasks to other people and being informed when those tasks have been completed. To do that, you can add participants to tasks in Kontact’s Todo List view by right-clicking on a task, selecting Edit, and then opening the Attendees tab of the dialog that pops up. Of course, this functionality is also available in other clients, such as Evolution or Mozilla; the dialogs just look a bit different.

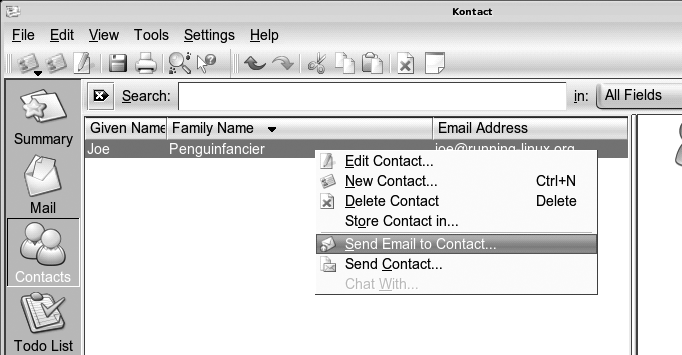

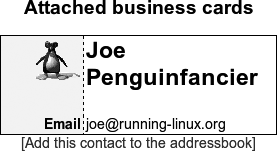

Similar to the iTip format (or iCal, which iTip is based on), there is an Internet standard for exchanging contact information called vCard. To communicate your new street address and phone number to your grandmother, who uses Mozilla on Windows for managing her many contacts, you could send her a message with your vCard attached (Figure 8-47). Using Kontact, this is as easy as right-clicking on your entry in the address book and selecting Send Contact. The resulting message should be easily understandable by most email programs on Windows, Linux, or the Mac. Most programs offer the user some convenient way to import the received vCard into his or her own address book. You can see how Kontact’s mail component presents such a message in Figure 8-48.

As we have seen, it is quite possible to carry out basic group organization using only email mechanisms. This has two advantages: no groupware server is needed, and the operations work across different platforms and clients. On the other hand, things such as sharing a common calendar between several people or allowing read-only access to centrally managed information are not easily done with this scheme. This is where a groupware server starts to make sense.

Linux is supported as a platform by a wide range of groupware server solutions, including both open source projects and proprietary products. They all offer a core set of functionality for email, calendaring, and address and task management, but also contain various extensions for things such as resource management, time tracking, and even project planning. In general, these systems can be extended with custom components to offer functionality that is not provided by the standard package. Such components are sometimes available from the creators themselves, but are also often developed by third-party developers or as part of individual consulting projects.

The following sections describe the most well-known solutions available as free software at the time of this writing, with their respective focus areas and peculiarities.

The Kolab project grew out of a contract given by the German Federal Agency of IT Security to a group of companies to build a groupware solution accessible by both Outlook on Microsoft Windows and a KDE client on Linux. The developers created a sequence of concept documents and reference server implementations (called Kolab 1 and Kolab 2). They also built the abilitity to access these servers and operate on their data into the KDE Kontact suite client. Additionally, a closed-source plug-in for MS Outlook and a web-based client were developed.

The server implementation (Kolab 2) includes popular free software server components such as the Cyrus IMAP server for mail storage, the Postfix mail transfer agent, OpenLDAP as a directory service, and the Apache web server. It is a complete, standalone system that installs itself from scratch onto a basic Linux machine without any outside dependencies. The Kolab server is unique in that it does not store the groupware data in a relational database, like many of the others do, but instead uses mail folders inside the IMAP server for storage. Finally, it provides a unified management interface, written in PHP, to the components.

The Kolab server allows users to share calendars and contact folders with each other using fine-grained permissions for groups or individual people. It also offers management of distribution lists and resources such as rooms or cars, and the ability to check the free or busy state of people and resources. There is also a form of delegated authority, in which people can work on behalf of others, such as a secretary acting on behalf of his boss.

You can find more about Kolab at http://www.kolab.org.

The groupware server project (nicknamed OGo) came into being when Skyrix Software AG put its established commercial product under free software licenses and continued as the most significant contributor in the community to improve the product. This move worked out nicely for the company, as both its business and the groupware server project have been thriving ever since.

The OGo server provides a web-based interface to email, calendaring, contacts, and document and tasks management. In addition to the browser-based interface, all data can be accessed via several different standard protocols, so that access from Kontact or Evolution is also possible. Plug-ins that enable Windows users to connect to the server with Outlook exist as well, albeit as a commercial add-on product. Users can share calendars and address books as well as task lists, and can create arbitrary associations between individual entries.

To be fully functional, an OGo installation needs several additional components, such as an IMAP server, a PostgreSQL database, a working mail transfer agent, and a directory service such as OpenLDAP.

You can find more about OGo at http://www.opengroupware.org.

Coming from a common PHP codebase, phpGroupWare and eGroupware offer groupware functionality primarily through browser-based access. Users can manipulate and view their own and other people’s calendars and contact information and manage files, notes, and news items. Several additional optional applications are available.

Both servers need to be installed on top of an existing web server and database and can make use of a mail server for sending and accessing mail via IMAP, if one is available.

More information about phpGroupware and eGroupware is available at the following URL: http://www.phpgroupware.org and http://www.egroupware.org.

The OPEN-XCHANGE server started out as a proprietary product, but has since been put under open source licenses. Like many other solutions, it builds on and works with other server components, such as the Apache web server and OpenLDAP. On top of those, it offers several standard modules, such as a calendar and contacts and tasks management, as well as document and project management, and discussion forum, knowledge base, and web mail components.

Technologically, OPEN-XCHANGE is different from many of the other solutions in that it is built using Java technologies. This makes it attractive if integration with existing Java-based applications is desired.

Read more about OPEN-XCHANGE at http://www.open-xchange.org.

In addition to the free and open source solutions described in the previous sections, several commercial and nonfree alternatives are available as well. All of them are powerful and full-featured, and support Linux as a native platform either exclusively or along with other platforms. The most important ones include Novell Groupwise, Novell SUSE Linux Openexchange (based on OPEN-XCHANGE), Lotus Notes & Domino, Oracle Groupware, and Samsung Contact and Scalix (both based on HP Openmail). The web sites of the respective vendors and products have more information on each of them.

One of the benefits of having information centrally stored and maintained is that changes and updates need only be done in one place and are then available to everyone immediately. This is especially important for contact information, which is prone to change and become out of date. The ability to quickly search through large amounts of contacts flexibly is another requirement that becomes more important the larger the organization gets, with all its internal and external communication partners. To meet this need, so-called directory services have been developed, along with a standard protocol to access and query them. The protocol is Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), shared by a number of implementations, including the open source implementation OpenLDAP and (with typical Microsoft extensions) Microsoft Active Directory. OpenLDAP can be integrated with many of the groupware systems described in the previous sections.

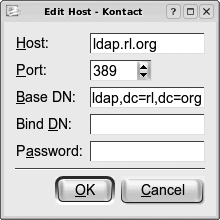

The address book components of all major groupware suites allow the administrator to tie them to one or several LDAP servers, which are then queried for contact information and will be used for email autocompletion when composing emails. In Kontact, the LDAP configuration dialog for adding a new LDAP query host looks like Figure 8-49.

Specify the hostname of the server to be used for queries, the port it listens on (the default should be fine), and a so-called base DN, which is the place in the LDAP hierarchy where searches should start. The choice of base DN can help tailor the LDAP queries to the needs of your users. If, for example, your company has a global address book with subtrees for each of its five continental branches, you might prefer to search only your local branch instead of the full directory. Your site’s administrator should be able to tell you the values to be entered here. If the server only allows queries by authenticated users, enter your credentials as well.

With LDAP access set up, you can try opening up a mail composer in Kontact, for example, and typing someone’s name in the recipient field. After a second or so a list of possible matches that were found in the central LDAP addressbook should be shown. You can then simply select the one you were thinking of from the list. Additionally all groupware suites offer the ability to search for and display someone’s contact information, if you just want to look it up. In Kontact, the query dialog can be shown by clicking the LDAP Lookup button on the toolbar or from the Tools menu.