The number of commands on a typical Unix system is enough to fill a few hundred reference pages. And you can add new commands too. The commands we’ll tell you about here are just enough to navigate and to see what you have on the system.

As with Windows and virtually every modern computer system, Unix files are organized into a hierarchical directory structure. Unix imposes no rules about where files have to be, but conventions have grown up over the years. Thus, on Linux you’ll find a directory called /home where each user’s files are placed. Each user has a subdirectory under /home. So if your login name is mdw, your personal files are located in /home/mdw. This is called your home directory. You can, of course, create more subdirectories under it.

If you come from a Windows system, the slash (/) as a path separator may look odd to you

because you are used to the backslash (\). There is nothing tricky about the

slash. Slashes were actually used as path separators long before

people even started to think about MS-DOS or

Windows. The backslash has a different meaning on Unix (turning off

the special meaning of the next character, if any).

As you can see, the components of a directory are separated by slashes. The term pathname is often used to refer to this slash-separated list.

What directory is /home in? The directory named /, of course. This is called the root directory. We have already mentioned it when setting up filesystems.

When you log in, the system puts you in your home directory.

To verify this, use the “print working directory,” or pwd , command:

$ pwd

/home/mdwThe system confirms that you’re in /home/mdw.

You certainly won’t have much fun if you have to stay in one directory all the time. Now try using another command, cd , to move to another directory:

$cd /usr/bin$pwd/usr/bin $cd

Where are we now? A cd with

no arguments returns us to our home directory. By the way, the home

directory is often represented by a tilde (~). So the string ~/programs means that programs is located right under your home

directory.

While we’re thinking about it, let’s make a directory called ~/programs. From your home directory, you can enter either:

$ mkdir programsor the full pathname:

$ mkdir /home/mdw/programsNow change to that directory:

$cd programs$pwd/home/mdw/programs

The special character sequence .. refers to the directory just above the

current one. So you can move back up to your home directory by

typing the following:

$ cd ..You can also always go back to your home directory by just typing:

$ cdno matter where in the directory hierarchy you are.

The opposite of mkdir is rmdir, which removes directories :

$ rmdir programsSimilarly, the rm command deletes files . We won’t show it here because we haven’t yet shown how to create a file. You generally use the vi or Emacs editor for that (see Chapter 19), but some of the commands later in this chapter will create files too. With the -r (recursive) option, rm deletes a whole directory and all its contents. (Use with care!)

At this point, we should note that the graphical desktop environments for Linux, such as KDE and GNOME, come with their own file managers that can perform most of the operations described in this chapter, such as listing and deleting files, creating directories, and so forth. Some of them, like Konqueror (shipped with KDE) and the web browser in that environment, are quite feature-rich. However, when you want to perform a command on many files, which perhaps follow a certain specification, the command line is hard to beat in efficiency, even it takes a while to learn. For example, if you wanted to delete all files in the current directory and all directories beneath that which start with an r and end in .txt, the so-called Z shell (zsh) would allow you to do that with one line:

$ rm **/r*.txtMore about these techniques later.

Enter ls to see what is in a directory. Issued without an argument, the ls command shows the contents of the current directory. You can include an argument to see a different directory:

$ ls /homeSome systems have a fancy ls that displays special files—such as directories and executable files—in bold, or even in different colors. If you want to change the default colors, edit the file /etc/DIR_COLORS, or create a copy of it in your home directory named .dir_colors and edit that.

Like most Unix commands, ls

can be controlled with options that start with a hyphen (-). Make sure you type a space before the

hyphen. One useful option for ls is

-a for “all,” which will reveal to you riches

that you never imagined in your home directory:

$cd$ls -a. .bashrc .fvwmrc .. .emacs .xinitrc .bash_history .exrc

The single dot refers to the current directory, and the double dot refers to the directory right above it. But what are those other files beginning with a dot? They are called hidden files. Putting a dot in front of their names keeps them from being shown during a normal ls command. Many programs employ hidden files for user options—things about their default behavior that you want to change. For instance, you can put commands in the file .Xdefaults to alter how programs using the X Window System operate. Most of the time you can forget these files exist, but when you’re configuring your system you’ll find them very important. We list some of them later.

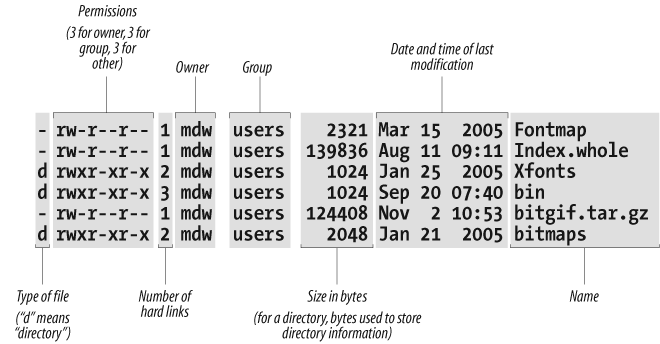

Another useful ls option is -l for “long.” It shows extra information about the files. Figure 4-1 shows typical output and what each field means. Adding the -h (“human” option) shows the file sizes rounded to something more easily readable.

We discuss the permissions, owner, and group fields in a later chapter, Chapter 11. The ls command also shows the size of each file and when it was last modified.

One way to look at a file is to invoke an editor, such as:

$ xemacs .bashrcBut if you just want to scan a file quickly, rather than edit it, other commands are quicker. The simplest is the strangely named cat command (named after the verb concatenate because you can also use it to concatenate several files into one):

$ cat .bashrcBut a long file will scroll by too fast for you to see it, so most people use the more command instead:

$ more .bashrcThis prints a screenful at a time and waits for you to press

the spacebar before printing more. more has a lot of powerful options. For

instance, you can search for a string in the file: press the slash

key (/), type the string, and

press Return.

A popular variation on the more command is called less . It has even more powerful features; for instance, you can mark a particular place in a file and return there later.

Sometimes you want to keep a file in one place and pretend it is in another. This is done most often by a system administrator, not a user. For instance, you might keep several versions of a program around, called prog.0.9, prog.1.1, and so on, but use the name prog to refer to the version you’re currently using. Or you may have a file installed in one partition because you have disk space for it there, but the program that uses the file needs it to be in a different partition because the pathname is hard-coded into the program.

Unix provides links to handle these situations. In this section, we’ll examine the symbolic link, which is the most flexible and popular type. A symbolic link is a kind of dummy file that just points to another file. If you edit or read or execute the symbolic link, the system is smart enough to give you the real file instead. Symbolic links work a lot like shortcuts under MS-Windows, but are much more powerful.

Let’s take the prog example. You want to create a link named prog that points to the actual file, which is named prog.1.1. Enter the following command:

$ ln -s prog.1.1 progNow you’ve created a new file named prog that is kind of a dummy file; if you run it, you’re really running prog.1.1. Let’s look at what ls -l has to say about the file:

$ ls -l prog

lrwxrwxrwx 2 mdw users 8 Nov 17 14:35 prog -> prog.1.1The l at the beginning of

the output line shows that the file is a link, and the little

-> indicates the real file to

which the link points.

Symbolic links are really simple, once you get used to the idea of one file pointing to another. You’ll encounter links all the time when installing software packages.