Everybody who has even the slightest connection with computers and has not heard about, or used, the World Wide Web, most have spent some serious time under a rock. Like word processors or spreadsheets some centuries ago, the Web is what gets many people to use computers at all in the first place. We cover here some of the tools you can use to access the Web on Linux.

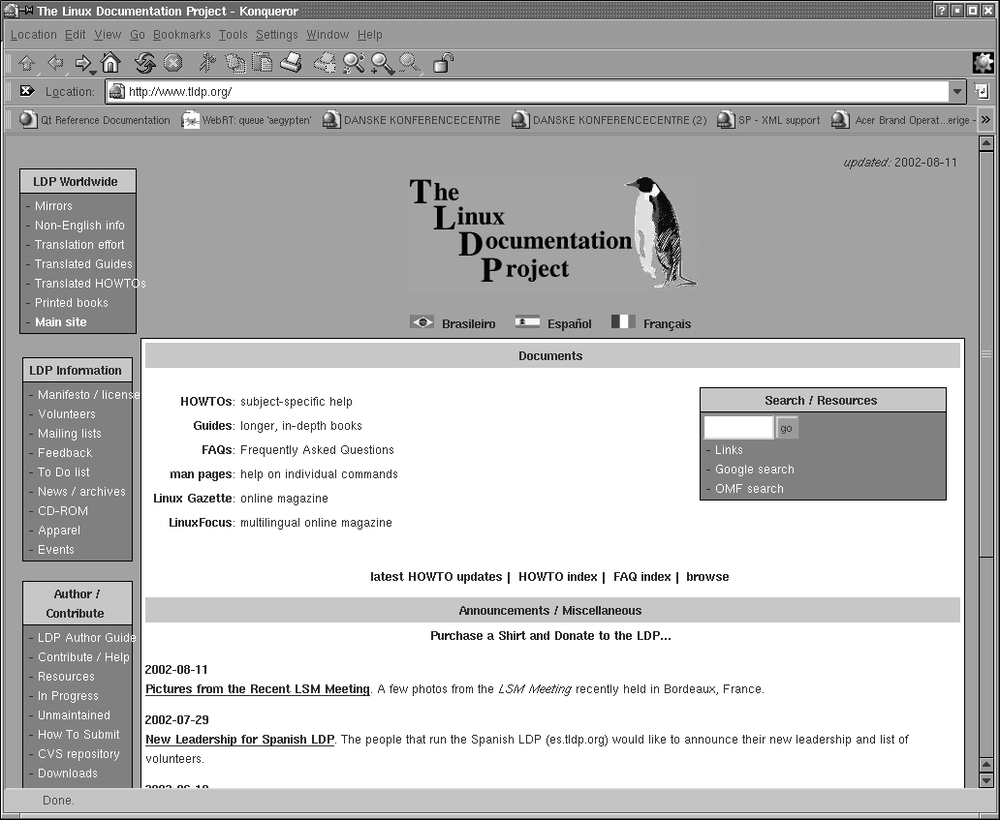

Linux was from the beginning intimately connected to the Internet in general and the Web in particular. For example, the Linux Documentation Project (LDP ) provides various Linux-related documents via the Web. The LDP home page, located at http://www.tldp.org, contains links to a number of other Linux-related pages around the world. The LDP home page is shown in Figure 5-1.

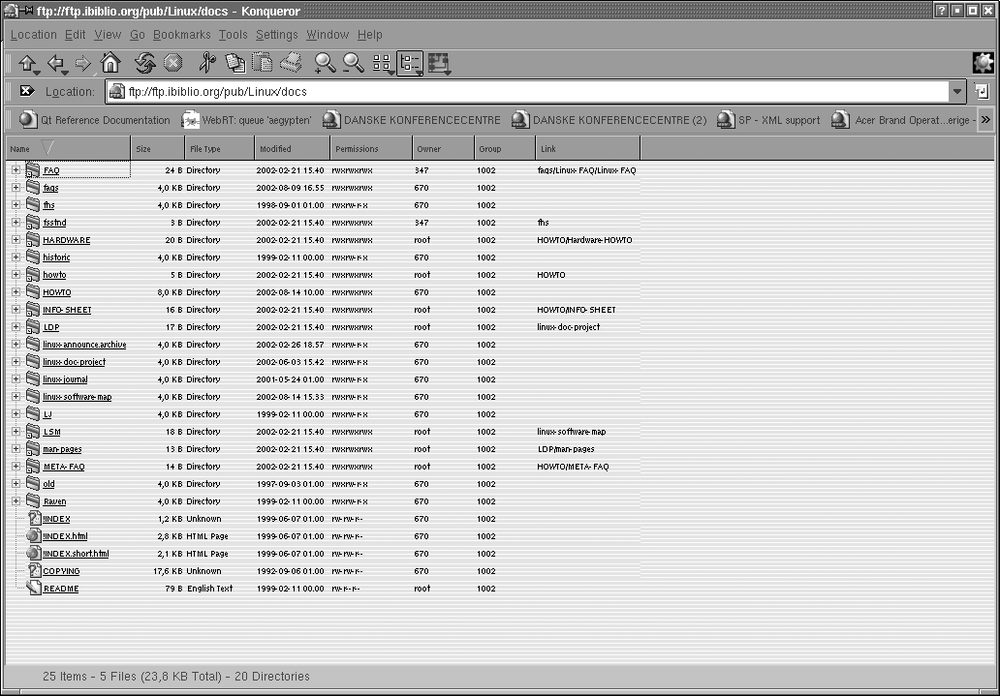

Linux web browsers usually can display information from several types of servers, not just HTTP servers sending clients HTML pages. For example, when accessing a document via HTTP, you are likely to see a page such as that displayed in Figure 5-1--with embedded pictures, links to other pages, and so on. When accessing a document via FTP, you might see a directory listing of the FTP server, as seen in Figure 5-2. Clicking a link in the FTP document either retrieves the selected file or displays the contents of another directory.

The way to refer to a document or other resource on the Web, of course, is through its Uniform Resource Locator, or URL. A URL is simply a pathname uniquely identifying a web document, including the machine it resides on, the filename of the document, and the protocol used to access it (FTP, HTTP, etc.). For example, the Font HOWTO, an online document that describes the optimal use of fonts on Linux, has the following URL:

| http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/html_single/Font-HOWTO/index.html |

Let’s break this down. The first part of the URL, http:, identifies the protocol used for the document, which in this case is HTTP. The second part of the URL, //www.tldp.org, identifies the machine where the document is provided. The final portion of the URL, HOWTO/html_single/Font-HOWTO/index.html, is the logical pathname to the document on www.tldp.org. This is similar to a Unix pathname, in that it identifies the file index.html in the directory HOWTO/html_single/Font-HOWTO. Therefore, to access the Font HOWTO, you’d fire up a browser, telling it to access http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/html_single/Font-HOWTO/index.html. What could be easier?

Actually, the conventions of web servers do make it easier. If you specify a directory as the last element of the path, the server understands that you want the file index.html in that directory. So you can reach the Font HOWTO with a URL as short as:

| http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/html_single/Font-HOWTO/ |

To access a file via anonymous FTP, we can use a URL, such as:

| ftp://ftp.ibiblio.org/pub/linux/docs/FAQ |

This URL retrieves the Linux FAQ. Using this URL with your browser is identical to using ftp to fetch the file by hand.

The best way to understand the Web is to explore it. In the following section we’ll explain how to get started with some of the available browsers. Later in the chapter, we’ll cover how to configure your own machine as a web server for providing documents to the rest of the Web.

Of course, in order to access the Web, you’ll need a machine with direct Internet access (via either Ethernet or PPP). In the following sections, we assume that you have already configured TCP/IP on your system and that you can successfully use clients, such as ssh and ftp.

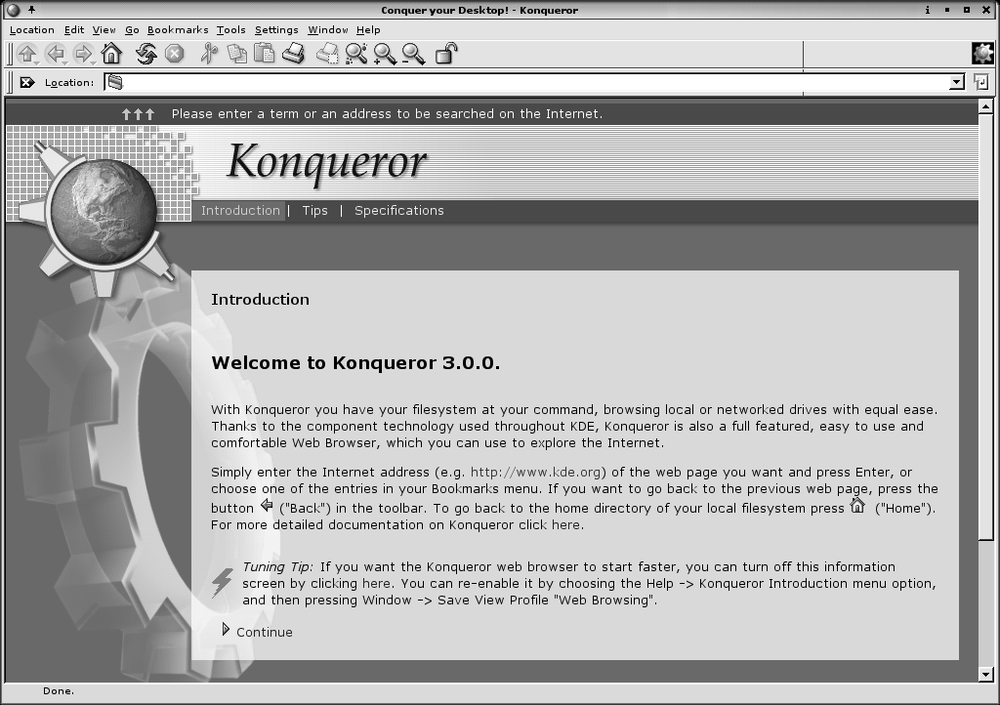

Konqueror is one of the most popular browsers for Linux. It features JavaScript and Java support, can run Firefox plug-ins (which allow you to add functions such as viewing Flash presentations), and is well integrated into the KDE desktop described in “The K Desktop Environment” in Chapter 3. Actually, when you install KDE, Konqueror will be installed as an integral part of the system. In the section on KDE, we have already described how to use Konqueror to read local information files. Now we are going to use it to browse the Web.

Most things in Konqueror are quite obvious, but if you want to read more about it, you can use Konqueror to check out http://www.konqueror.org.

Here, we assume that you’re using a networked Linux machine running X and that you have Konqueror installed. As stated before, your machine must be configured to use TCP/IP, and you should be able to use clients, such as ssh and ftp.

Starting Konqueror is simple. Run the command:

eggplant$konquerorurl

where url is the complete web

address, or URL, for the document you wish to view. If you don’t

specify a URL, Konqueror will display a splash

screen, as shown in Figure

5-3.

If you run Konqueror from within KDE, you can simply type Alt-F2 to open the so-called minicli window, and type the URL. This will start up Konqueror and point it directly to the URL you have specified.

We assume that you have already used a web browser to browse the Web on some computer system, so we won’t go into the very basics here; we’ll just point out a few Linux-specific things.

Keep in mind that retrieving documents on the Web can be slow at times. This depends on the speed of the network connection from your site to the server, as well as the traffic on the network at the time. In some cases, web sites may be so loaded that they simply refuse connections; if this is the case, Konqueror displays an appropriate error message. At the bottom edge of the Konqueror window, a status report is displayed, and while a transfer is taking place, the KDE gear logo in the upper-right corner of the window animates. Clicking the logo, by the way, will open a new Konqueror window.

As you traverse links within Konqueror, each document is saved in the window history, which can be recalled using the Go menu. Pressing the Back button (the one that shows an arrow pointing to the left) in the top toolbar of the Konqueror window moves you back through the window history to previously visited documents. Similarly, the Forward button moves you forward through the history.

In addition, the sidebar in Konqueror can show you previously visited web sites; that is a very useful feature if you want to go to a web site that you have visited some time ago — too long ago for it to still appear in the Go menu — but you do not remember the name any more. The History pane of the sidebar has your visited URLs sorted by sites. If you do not have a sidebar in your Konqueror window, it may be hidden; press F9 in that case, or select Window → Show Navigation Panel from the menu bar. The sidebar has several panels, of which one at a time is shown; the one you want in this case is the one depicted by a little clock. Click on the clock icon to see the previously visited sites.

You can also bookmark frequently visited web sites (or URLs) to Konqueror’s “bookmarks .” Whenever you are viewing a document that you might want to return to later, choose Add Bookmark from the Bookmarks menu, or simply press Ctrl-B. You can display your bookmarks by choosing the Bookmarks menu. Selecting any item in this menu retrieves the corresponding document from the Web. Finally, you can also display your bookmarks permanently in another pane of the sidebar by clicking on the yellow star. And of course, Konqueror comes with ample features for managing your bookmarks. Just select Bookmarks → Edit Bookmarks, and sort away!

You can also use the sidebar for navigating your home directory, your hardware, your session history, and many other things. Just try it, and you will discover many useful features.

Besides the sidebar, another feature that can increase your browsing experience considerably is the so-called tabbed browsing . First made popular by the open source browser Mozilla (see later in this chapter), Konqueror has really taken tabbed browsing to its heart and provides a number of useful features. For example, when you are reading a web page that contains an interesting link that you might want to follow later, while continuing on the current page now, you can right-click that link and select Open in New Tab from the context menu. This will create a new tab with the caption of that page as its header, but leave the current page open. You can finish reading the current page and then go on to one of those that you had opened while reading. Since all pages are on tabs in the single browser window, this does not clutter your desktop, and it is very easy to find the page you want. In order to close a tab, just click on the little icon with the tabs and the red cross.

As mentioned previously, you can access new URLs by running konqueror with the URL as the argument. However, you can also simply type the URL in the location bar near the top of the Konqueror window. The location bar has autocompletion: if you start typing an address that you have visited before, Konqueror will automatically display it for your selection. Once you are done entering the URL (with or without help from autocompletion), you simply press the Enter key, and the corresponding document is retrieved.

Konqueror is a powerful application with many options. You can customize Konqueror’s behavior in many ways by selecting Settings → Configure Konqueror. The sections Web Behavior and Web Shortcuts provide particularly interesting settings. In the section Cookies, you can configure whether you want to accept cookies domain by domain and even check the cookies already stored on your computer. Compare this to browsers that hide the cookies deep in some hidden directory and make it hard for you to view them (or even impossible without the use of extra programs!).

Finally, one particular feature deserves mention. Web browsers register themselves with the server using the so-called User Agent string, which is a piece of text that can contain anything, but usually contains the name and version of the web browser, and the name and version of the host operating system. Some notably stupid webmasters serve different web pages (or none at all!) when the web browser is not Internet Explorer because they think that Internet Explorer is the only web browser capable of displaying their web site.[*] But by going to the Browser Identification section, you can fool the web server into believing that you are using a different browser, one that the web server is not too snobbish to serve documents to. Simply click New, select the domain name that you want to access, and either type an Identification string of your own, or select one of the predefined ones.

Konqueror is not the only browser that reads web documents. Another browser available for Linux is Firefox , a descendant of Mozilla, which in turn started its life as the open source version of Netscape Navigator , the browser that made the Web popular to many in the first place. If your distribution does not contain Firefox already, you can get it from http://www.mozilla.org/products/firefox/. Firefox’s features are in many aspects similar to Konqueror’s, and most things that you do with one you should be able to do with the other. Konqueror wins over Firefox in terms of desktop integration if you use the KDE desktop, of course, and also has more convenience features, whereas Firefox is particularly strong at integrating nonstandard technologies such as Flash. Firefox also comes with a very convenient pop-up blocker that will display a little box at the top of your browser window when it has blocked one of those annoying pop-ups. You can select to always block it (and not be told about it anymore), always allow pop-ups from that site (they could be important information about your home banking account), or allow the pop-up once.

Firefox has one particular powerful feature that is often overlooked: its extensions. By selecting Tools → Extensions from the menu bar, a dialog with installed extensions pops up; it is quite likely that you initially don’t have any (unless your distributor or system administrator has preinstalled some for you). Click on the Get More Extensions link, and a long list with extensions that have been contributed to Firefox will show up. By default, you will see the list of the most popular and the list of the newest extensions, but take some time to discover all categories that seem interesting to you, there are a lot of goodies in here.

We would like to point out two extensions that we have found particularly interesting. Adblock adds a small overlay that looks like a tab to parts of the rendered web page that it suspects to be banner advertising. Just click on that little tab, click OK in the dialog that pops up (or edit the URL to be blocked, maybe to be even more general), and enjoy web pages without banner ads. It can actually become an addiction to refine the blocking patterns so much that you do not see any banner advertising anymore while surfing the Web. But just zapping a single one is a source of joy.

The other extension that we found particularly interesting is ForecastFox. It lets you select a number of locations on the earth and then displays small icons in the status bar (or other locations at your discretion) that show the current weather at those locations. Hover the mouse over one of those icons, and you will get a tooltip with more detailed information.

As with Konqueror, you should plan to spend some time with Firefox in order to explore all its possibilities. In many aspects, such as security, privacy, and browsing convenience, it beats the most often used browser on the Web these days hands down.

Yet another versatile browser is w3m . It is a text-based browser, so you miss the pictures on a web site. But this makes it fast, and you may find it convenient. You can also use it without the X Window System. Furthermore, when you want to save a page as plain text, w3m often provides a better format than other browsers, because text-based rendering is its main purpose in life. Then there is the ad-financed browser Opera, which has become quite popular lately, and finally, for those who never want to leave Emacs, there is Emacs/W3, a fully featured web browser you can use within Emacs or XEmacs.

[*] A web site that can be browsed with only one browser or that calls itself “optimized for browser X” should make you virtually run away, wringing your hands in wrath over such incompetence on the part of the webmaster.