Personal digital assistants (PDAs ) have become quite commonplace these days, and as Linux adepts, we want to use them with our favorite operating system. In this section, we explain how to synchronize PDAs with Linux desktops.

This section is not about running Linux on PDAs, even though this is possible as well. People have successfully run Linux and Linux application software on the HP/Compaq iPaq line. One PDA product line, the Sharp Zaurus series, even comes with Linux preinstalled, though it does not show up very obviously when using the device. http://www.handhelds.org has a lot of valuable information about running Linux on PDAs.

Using your PDA with your desktop means, for most intents and purposes, synchronizing the data on your PDA with the data on your desktop computer. For example, you will want to keep the same address book on both computers, and synchronization software will achieve this for you.

Do not expect PDA vendors to ship Linux synchronization software; even the Sharp Zaurus—which, as mentioned, runs Linux on the PDA—comes with only Windows desktop synchronization software. But as always, Linux people have been able to roll their own; a number of packages are available for this purpose.

Synchronizing your PDA with your desktop involves a number of steps:

Creating the actual hardware connection and making the hardware (the PDA and its cradle or other means of connection) known to Linux.

Installing software that handles special synchronization hardware such as HotSync buttons

Installing software that handles the actual synchronization of data objects

Using desktop software that ensures synchronization at the application level (e.g., between the PDA calendar and your desktop calendar software)

Let’s have a look at the hardware first. PDAs are usually connected to the desktop by means of a so-called cradle, a small unit that is wired to the computer and accepts the PDA in order to connect it electrically. Sometimes, a direct sync cable is used, attached to both the desktop computer and the PDA. The connection on the desktop computer side is either a USB interface or—much less often these days—a serial interface.

The first step in getting the connection to work is to see whether your PDA is recognized by the kernel. So connect the cradle (or the direct cable) to your computer and your PDA. Take a look at the kernel log messages, which you can do by becoming root and typing tail -f /var/log/messages. (More information on kernel log messages is presented in “Managing System Logs” in Chapter 10.)

Now, while viewing the kernel log messages, force a synchronization attempt from the PDA, such as by pressing the HotSync button at the cradle or issuing a command in the user interface of the PDA that performs a synchronization. If the PDA is connected via USB, you should see something like the following (some lines were truncated to fit the book’s page):

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: ohci_hcd 0000:02:06.1: wakeup

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: klogd 1.4.1, ---------- state change ----------

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: usb 3-2: new full speed USB device using address

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: usb 3-2: Product: Palm Handheld

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: usb 3-2: Manufacturer: Palm, Inc.

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: usb 3-2: SerialNumber: 3030063041944034303506909

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: visor 3-2:1.0: Handspring Visor / Palm OS convert

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: usb 3-2: Handspring Visor / Palm OS converter now

Jun 21 10:32:52 tigger kernel: usb 3-2: Handspring Visor / Palm OS converter nowIn this case, a USB-connected Palm Tungsten T3 was found. If nothing shows up, several things could have gone wrong: the hardware connection could be broken, the synchronization request could not have been recognized, or the kernel could be missing the necessary driver modules. Chapter 18 has more information about locating and installing kernel driver modules, in case that’s the problem.

Next, you need the software that synchronizes actual data over the wire. For the very common Palm family of PDA (which also includes the Sony Clié, the Handspring Visor, and many other look-alikes), this is the pilot-link package. The package is already included with many popular distributions; if you need to download it, you can find it at http://www.pilot-link.org. Usually, you are not going to use the programs contained in this package directly, but through other application software that builds on them. What this package contains, besides the building blocks for creating said application software, is conduits, small applications that support one particular type of data to be synchronized. There are conduits for the calendar, the address book, and so on.

Up to this point, the software and procedures we’ve described were dependent on the type of PDA you want to synchronize, and independent of your desktop software. The actual software that you are going to interact with, however, is different for different desktops. We look here at KPilot, a comprehensive package for the KDE desktop that synchronizes Palm-like PDAs with both KDE desktop applications such as KOrganizer and KAddressBook and GNOME desktop applications such as Evolution.

KPilot, at http://www.kpilot.org, consists of two programs, kpilotDaemon and kpilot. In theory, you need only kpilotDaemon, as this is the software that waits for the HotSync button to be pressed and then performs the synchronization. In practice, you will want to use the kpilot application at least initially, as it allows you to configure the daemon and check that everything works as expected.

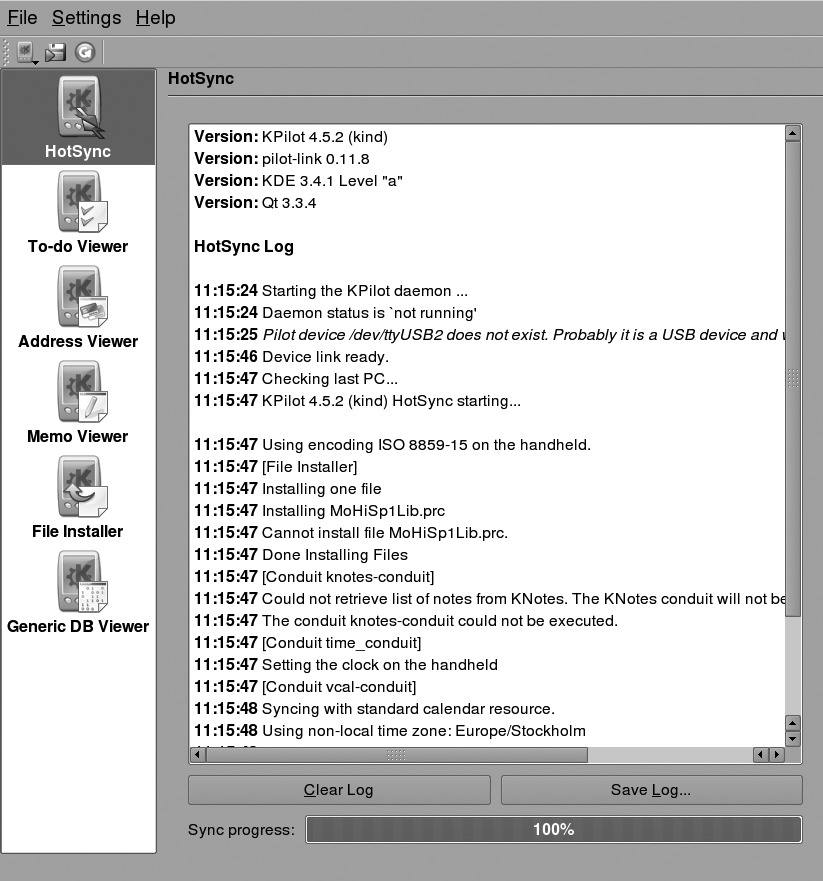

Upon starting up KPilot (Figure 8-45), select Settings → Configure KPilot from the menu bar. The program offers to start the Configuration Wizard; click that button. On the first page, you need to provide two pieces of information: the username stored in the PDA (so that the data is synced with the right desktop data), and the desktop computer port to which the PDA is connected. KPilot offers to autodetect this, which you should always try. If it cannot autodetect your connection (and you have ensured that the actual hardware connection is working, as described in the previous section), try specifying either /dev/ttyUSB1 or /dev/ttyUSB2 (or even higher numbers) if you have a USB-connected PDA, and /dev/ttyS0 or /dev/ttyS1 if you have a serially connected PDA. On the next page, you will be asked which desktop application set you want to synchronize with; pick the right one for you here.

Once you are set up, you can give KPilot a try. It will have started kpilotDaemon automatically if it was not running yet.

During the following steps, keep an eye on the HotSync Log window in KPilot; there could be important information here that can help you troubleshoot problems. If you see the message “Pilot device /dev/ttyUSB2 does not exist. Probably it is a USB device and will appear during a HotSync” or something similar, that’s nothing to worry about.

Now press the HotSync button on the cradle or force a synchronization in whichever way your PDA does this. If you see “Device link ready,” plus many more progress messages about the various conduits, things should be going fine. Notice that if you have a lot of applications installed on your PDA, the synchronization progress can take quite a while.

What can you expect to work on Linux? Synchronizing the standard applications, such as calendar, address book, and notes, should work just fine. For many other commercially available PDA applications, there is no Linux software provided, but since KPilot is able to synchronize Palm databases without actually understanding their contents, you can at least back up and restore this data. You can also install the application packages themselves by means of KPilot’s File Installer. Even the popular news channel synchronization software AvantGo works nicely on Linux.

Things that typically do not work (or are very difficult to get to work) are access to additional storage media such as CompactFlash cards, and applications that perform additional functionality for synchronization (such as downloading new databases from a web site as part of the synchronization process). A typical example of the latter category is airline timetable applications. So if you have a Windows computer available (or have configured your computer to be dual-boot for both Windows and Linux), it can be a good idea to still install the Windows desktop synchronization software. For day-to-day activities, Linux and your PDA (at least Palm-like PDAs) are an excellent combination.

Work is currently being done on creating a unified synchronization application called KitchenSync. Once this is ready, the intention is to replace not only KPilot and other PDA synchronization packages but also the many smaller packages for synchronizing your Linux desktop computer with various types of cellular phones. KitchenSync is a work in progress, and you can find more information about it at http://www.handhelds.org/~zecke/kitchensync.html. Another program that aims in a similar direction is OpenSync.