Linux can fit into a network’s email picture in any of several ways. One obvious way is to function as your domain’s primary mail server, handling SMTP and, if you desire, POP or IMAP. Used in this way, the Linux mail server will most likely communicate with Windows desktop systems as POP or IMAP clients. This configuration can work quite well, but many Windows networks already have a Microsoft Exchange mail server. At first glance, there seems to be little reason to deploy a Linux mail server if you already have a working Microsoft Exchange server. Sometimes, though, a Linux server can be used to help an Exchange server.

Tip

Microsoft Exchange provides features that are most readily used by Microsoft email clients, and that aren’t fully replicated by non-Microsoft servers. Thus, depending on your needs, a Linux server might not be an adequate replacement for an Exchange server. Some projects are underway to change this. Specifically, the SuSE Linux Openexchange Server (SLOX; http://www.suse.de/en/business/products/openexchange/), Kroupware (http://kroupware.org), and the Open Source Exchange Replacement (OSER; http://www.thewybles.com/oser/) are projects intended to replace the Exchange server, while otlkon (http://otlkcon.sourceforge.net) aims to provide Linux client features. Note that these projects aren’t quite drop-in replacements or aren’t yet finished. Thus, Linux can’t yet replace an Exchange server, but Linux can supplement one.

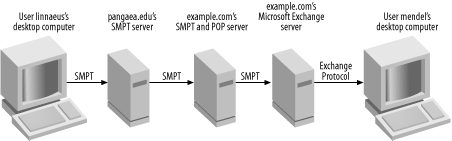

A Linux mail server is commonly used as an additional link in the email chain, appearing just before the Microsoft Exchange server, as shown in Figure 13-3. Placed in this way, the Linux mail server functions as a filter, similar to a firewall. Using tools designed to detect and remove spam and worms (as described in the Section 13.5), the Linux system can keep these unwanted messages from ever reaching the Exchange server. This can be preferable to filtering them out on the Exchange server because it reduces the load on the Exchange server, improving performance, particularly for entirely local actions. Another advantage of this configuration is that you can use strong packet-filter firewall rules on the Exchange server, protecting it from all outside access attempts. You can also use a Linux system to determine which of several internal servers should receive any given email; for instance, you can direct email according to the username to either of two or three servers, each of which handles only some of your site’s local users.

Figure 13-3. A Linux mail server can fit into an existing Exchange network as an email filter system

Configuring a Linux mail server this way isn’t greatly different from configuring it as a domain’s only mail server. The main difference is that the system forwards all the mail it receives; it treats few or no messages as local. This is done by setting the server’s mail relay options, as described in an earlier section.

Warning

A Linux mail server configured this way can protect you from spam and worms that originate outside your network. If you send your outgoing mail through the Linux mail server, it can also protect outside systems from worms that might get loose on your local network. Local mail that’s handled exclusively by the Exchange server won’t be examined, however, unless you configure Exchange to send even local mail via the Linux server, which increases the network load between those two systems. Thus, if a worm breaks loose on your local network, it can still spread quickly to other computers.