Linux can be an effective addition to a Windows network for several reasons, most of which boil down to cost. Windows has achieved dominance, in part, by being less expensive than competitors from the 1990s, but today Linux can be less expensive to own and operate. This is particularly true if you’re running Windows NT 4.0, which has reached end-of-life and is no longer supported. (Windows 2000 will soon fall into this category, as well.) For these old versions of Windows, you’re faced with the prospect of paying to upgrade to a newer version of Windows or switch to another operating system. Linux can be that other OS, but you should know something about Linux’s features and capabilities before you deploy it.

Effectively deploying Linux requires understanding the OS’s capabilities and where it makes the most sense to use. This chapter begins with a look at the Linux roles that this book describes in subsequent chapters. The bulk of this chapter is devoted to an overview of Linux’s capabilities and requirements when used as a server or as a desktop system. Because you may be considering replacing Windows systems with Linux, this chapter concludes with a comparison of Linux to Windows in these two roles.

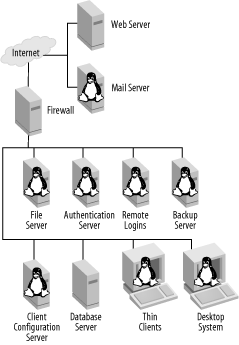

Most operating systems—and Linux is no exception to this rule—can be used in a variety of ways. You can run Linux (or Windows, or Mac OS, or most other common general-purposes OSs) on personal productivity desktop systems, on mail server computers, on routers, and so on. This book doesn’t cover every possible use of Linux; instead, it focuses on how Linux interacts with Windows systems on a local area network (LAN) or how Linux can take over traditional Windows duties. This book will further focus on areas in which you can get the most “bang for the buck” by deploying Linux, either in addition to or instead of Windows systems. Chapter 2 covers Linux deployment strategies in greater detail, but, for now, consider Figure 1-1, which depicts a typical office network. Linux’s mascot is a penguin (known as Tux), so Figure 1-1 uses penguin images to mark the areas of Linux deployment covered in this book.

Of course, Linux can be used in roles not shown in Figure 1-1. In fact, Linux can be an excellent choice for an OS for such roles as a web server; however, because such uses aren’t LAN-centric or don’t tie closely to Windows, this book doesn’t cover them. You might want to begin with just one or two functions for Linux on your network, such as a file server or a Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) server. Some systems, such as backend database servers, may be so vital and data-intensive that replacing them with Linux systems, although possible, is a major undertaking that can’t be adequately covered here.