If Windows systems are to interact with Linux systems via text-mode tools, you must locate matching Windows clients to Linux servers or locate Windows servers for Linux clients. The first task is considerably easier and likely to be more productive than the second; although text-mode Windows login servers do exist, they aren’t nearly as useful as Linux remote text-mode login servers because Windows was never designed with this sort of operation in mind.

Windows client software for both

Telnet and SSH protocols is fairly easy to find. In fact, all

versions of Windows that support TCP/IP networking ship with a Telnet

client. Type TELNET in a DOS prompt window or

select the Telnet item from the Start menu to launch this client.

If you’re not satisfied with the features of the standard Windows Telnet server or if you want to use SSH to access your Linux system, you’ll need to look elsewhere. One excellent resource is the Free SSH web site’s Windows page, http://freessh.org/windows.html, which lists Windows SSH clients and servers, of both the free and the pay variety. Many of these SSH clients can also handle Telnet and other protocols, so they’re well worth investigating.

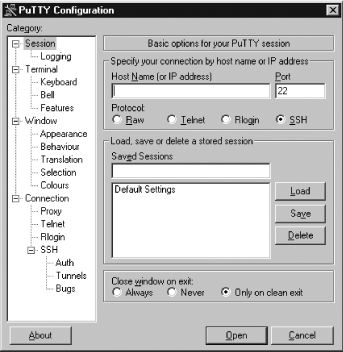

As an example of a Windows text-mode login client, consider PuTTY (http://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/putty/). This program can handle rlogin, Telnet, and SSH protocols. When you first launch it, you’ll see a PuTTY Configuration dialog box, as shown in Figure 10-1. To open a basic SSH session, type the hostname or IP address of the server in the Host Name (or IP Address) field, check that the Protocol item is set to SSH, and then click Open. The first time you connect, the system will notify you that the server’s host key is not cached. This is normal for an initial connection, so click Yes to accept the key. The system will then prompt you for a username and password in the access window and, if you enter them correctly, you’ll be in and able to use the remote system.

For more advanced uses, you can adjust various options by clicking their categories in the list in the Category field of the PuTTY Configuration dialog box. If you regularly use particular settings (including connections to specific servers), you can make the adjustments you want, type a session name in the Saved Sessions field, and click Save to save your settings. Thereafter, double-clicking on the session name launches a session with those settings.

Windows, unlike Linux, was not designed with remote text-mode use in mind. Although Windows has DOS—a text-mode OS—in its history, Windows simply never embraced the notion of remote text-mode access in the way Linux has. Furthermore, Windows is tied more tightly to its GUI for both common user programs and system administration than is Linux, so using it from a text-mode login will tie your hands in terms of the tasks you can accomplish.

These caveats aside, remote text-mode access tools for Windows are available. Because these tools are of limited utility, I don’t describe them in great detail, but they do deserve a few pointers. A few of the available servers include:

- Cygwin OpenSSH

The Cygwin package includes an OpenSSH server, whose setup and basic operation is documented at http://tech.erdelynet.com/cygwin-sshd.html. This configuration provides access to a Windows system using the Cygwin environment, which resembles a Unix environment but enables you to run many text-mode DOS and Windows programs.

- OpenSSH for Windows

This package borrows from Cygwin but doesn’t install a full Cygwin environment. As a result, when you log into the server, you’ll see a DOS-style C:\> prompt. You can learn more at http://sshwindows.sourceforge.net/.

- Georgia Softworks Telnet and SSH

Georgia Softworks (http://www.georgiasoftworks.com) sells a commercial Telnet server for Windows and a commercial SSH server for Windows. These packages provide unusually good terminal emulation; that is, they do a better job than most at enabling you to run text-mode programs that require extensive cursor control, such as text-mode editors.

As noted earlier, the Free SSH site’s Windows page (http://freessh.org/windows.html) provides pointers to Windows SSH servers as well as SSH clients, so you can consult it for links to more servers. As a general rule, the free offerings are scarce, but several commercial products are available.

One of the difficulties in using a text-mode Windows remote-access

tool manifests itself when you try to run programs that move the

cursor around the screen in an arbitrary way, such as text editors.

Under Linux, a set of libraries between programs and the screen

display handle the translation for any number of display

types—a text-mode console, an xterm window,

a remote Telnet session, and so on. (In fact, some Windows Telnet and

SSH clients provide options that influence how they interact with

these libraries by changing their terminal

emulation mode, which can improve their ability to handle

features such as colored text.) Windows lacks these libraries, so the

remote-access server must either implement these translations

themselves or ignore the issue. The former is a difficult task, so

many servers ignore the issue. The result is an inability to run

text-mode programs that do more than display text in a simple linear

fashion. For instance, typing EDIT in an

OpenSSH for Windows session effectively hangs the session.

Despite these limitations, text-mode login tools for Windows can be handy in some situations; you can run simple tools and scripts that don’t rely on GUI components or the more advanced text-mode features. If you have a specific use in mind for the access, you might be able to track down or write a program to do a job, thus saving considerable bandwidth (and, hence, time) that might otherwise be required to use a GUI login tool. You can also use an SSH server as a way to establish encrypted connections to other servers running on the Windows machine, by using SSH’s port-forwarding capabilities.