Once the server is running, you must populate the directory with information about your network’s users. To do this, you must understand distinguished name notation. Understanding at least the basics of LDIF files, which can be used to enter information into the directory, is also a necessity. With these pieces of information, you can actually begin populating the directory with user accounts.

Distinguished Names (DNs) are the pointers

to data in a directory. They’re similar in many ways

to filenames in hard-disk filesystems. For example, the Linux

filename /etc/X11/xdm/Xaccess refers to the

Xaccess file in the

/etc/X11/xdm directory, which in turn can be

broken down into a series of subdirectories leading to the root

directory of the Linux directory tree. Similarly, DNs are typically

composed of multiple elements that enable an LDAP implementation to

quickly locate the data. In the case of DNs, though, these elements

are labeled according to type. Common types in an

LDAP directory used for authentication

include Domain Class (DC), Common Name (CN), User ID (UID, which is

equivalent to a username rather than a numeric UID), and sometimes

Organizational Unit (OU). Each abbreviation is converted to lowercase

and separated from its value by an equal sign; these are then strung

together with commas and identified as a DN by using the

dn code and a colon:

dn: cn=Carl Linnaeus,dc=pangaea,dc=edu

This example refers to an entry for the common name Carl Linnaeus in the http://www.pangaea.edu domain. You may have noticed that

this notation is similar to the one for the rootdn

item in the slapd.conf file, as illustrated in

Example 8-1. This is no accident; the

rootdn entry identifies a DN for a user with

special privileges on the server.

Tip

Although the DC components of DN frequently combine to form an Internet domain name that’s associated with the LDAP server, this isn’t a requirement.

Occasionally, variants on this notation are necessary. One of these occurs when the CN for a user is not unique. For instance, suppose your organization has two users named Carl Linnaeus, one in the Botany department and one in the Genetics department. You might then create two DNs that add the appropriate OUs:

dn: cn=Carl Linnaeus+ou=Botany,dc=pangaea,dc=edu dn: cn=Carl Linnaeus+ou=Genetics,dc=pangaea,dc=edu

Tip

In practice, you’ll create these DNs in files with intervening lines that specify other account characteristics, as described in Section 8.3.2.

In this example, the DN begins with a Relative

Distinguished Name (RDN)—cn=Carl Linnaeus+ou=Botany or cn=Carl Linnaeus+ou=Genetics. An RDN uses a plus sign

(+) to separate two attributes, neither of which

is unique by itself. In this example, two users named Carl Linnaeus

exist, and presumably both the Botany and Genetics OUs host other

users.

Tip

The use of the plus sign to separate RDN components means that this

symbol can’t be used within an element without

taking special steps. Specifically, if an element must contain a plus

sign, the plus sign should be preceded by a backslash

(\). Other special characters that should be

preceded by a backslash include a hash mark (#) at

the start of a string, a space at the end of a string, a comma

(,), a double quote (“), a

backslash, a semicolon (;), and angle brackets

(< or >). Chances are you

won’t need to use any of these symbols in the DN

elements for a Unix-based account database, although spaces are

common in databases that originate on Windows systems.

DNs are usually case-insensitive, but case is preserved in storing

them. Thus, cn=carl

linnaeus,dc=pangaea,dc=edu is equivalent to

cn=Carl Linnaeus,dc=pangaea,dc=EDU. This

characteristic is based on matching rules defined in the schema,

though, so it’s not always true.

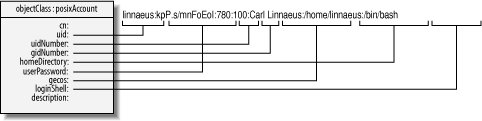

Behind the scenes,

OpenLDAP

may use any of several databases for data storage; but to examine and

modify data, a common plain-text format is desirable. This is where

LDIF comes into the picture; it represents LDAP directory entries

that are invariant across OpenLDAP backends, and even across LDAP

implementations. For the most part, it consists of a series of

attribute names and values, separated by colons. Entries begin with

the DN entry, as described earlier. Subsequent

entries’ content depend on the schemas a directory

uses. The NIS schema defines several object classes, each of which

defines several attributes. For the purposes of this chapter, the

posixAccount object class is one of the most

important of these object classes. This object

class’s attributes roughly correspond to entries in

the traditional Linux /etc/passwd file, as shown

in Figure 8-2.

Every field in the /etc/passwd file maps to an

attribute in the posixAccount object class,

although the names aren’t always intuitive. In

particular, the uid attribute maps to the Linux

username; the uidNumber attribute holds the Linux

UID number. The posixAccount object class also

defines two attributes, cn and

description, that aren’t present

in /etc/passwd. Of these, cn

is required and typically holds the user’s real

name.

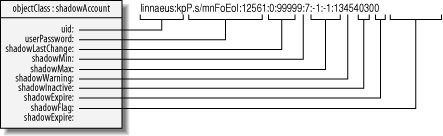

Figure 8-3 shows a mapping of the

shadowAccount object class to entries

traditionally found in /etc/shadow. All these

entries except uid are optional. This attribute,

though, as well as the userPassword and

description attributes, are in fact shared with

the posixAccount object class. Specifying values

for all the required attributes in these two object classes creates a

user account.

Tip

In traditional Linux accounts, using shadow passwords and the

/etc/shadow file increases security. The

equivalent use of the shadowAccount object class

in LDAP does not have this effect, though. When

properly configured, an LDAP account directory should be at least as

secure as a Linux shadow passwords system, whether or not you place

data in the shadowAccount structures. What

shadowAccount does provide is a place to store

password aging and expiration information.

Between these two object classes, you can define an account. To do so

in an LDIF file, you create one line per attribute, plus a few

objectClass attributes pointing to the objects

upon which the posixAccount and

shadowAccount objects rely. The result looks

something like this:

dn: uid=linnaeus,ou=People,dc=pangaea,dc=edu

uid: linnaeus

cn: Carl Linnaeus

objectClass: account

objectClass: posixAccount

objectClass: top

objectClass: shadowAccount

userPassword: {crypt}KpP.s/mnFoEoI

shadowLastChange: 12561

shadowMax: 99999

shadowWarning: 7

loginShell: /bin/bash

uidNumber: 780

gidNumber: 100

homeDirectory: /home/linnaeus

gecos: Carl LinnaeusTip

Don’t start generating accounts by copying this entry. As described in Section 8.3.3, there are easier ways to populate your directory than creating LDIF files by hand.

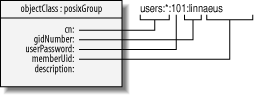

Figure 8-4 shows a mapping of the

posixGroup object class to entries traditionally

found in /etc/group. These entries are necessary

if the server is to deliver group information as well as account

information to clients. Note that these objects are not directly

related to accounts, although they do refer to accounts; the

memberUid attribute points to user accounts.

(Likewise, the gidNumber field in the

posixAccount object class points to a

posixGroup via its gidNumber

field.)

The NIS schema file defines several object classes in addition to

those described here. These object classes enable an LDAP server to

deliver information that’s traditionally contained

in /etc/fstab, /etc/hosts,

/etc/protocols, and more—in short, the

data that’s normally delivered by an NIS server.

Configuring OpenLDAP to deliver this information is similar to

configuring it to deliver account and group information, but such

configurations are beyond the scope of this chapter.

The simplest way to populate an OpenLDAP directory with account and group information is to convert this information from existing account and group files. You can perform this task with scripts available on the Internet. If you’re not migrating accounts directly, you may want to use these tools on a dummy password file to create a template you can use to create new accounts in piecemeal fashion.

The scripts you use to migrate an existing set of Linux accounts can

be obtained from http://www.padl.com/OSS/MigrationTools.html.

The download links at the bottom of this page retrieve a file called

MigrationTools.tgz. This tarball contains a

series of Perl scripts, each of which reads the contents of one or

more system configuration files and creates an equivalent LDIF file.

Tip

The migration tools package described here has a project version

number of 45, as revealed in the

CVSVersionInfo.txt file. If you obtain a more

recent version, you may find that some of the details have changed.

Before running the conversion scripts, you must edit one of them

(migrate_common.ph) so that it holds appropriate

site-specific information. Specifically, change the

$DEFAULT_MAIL_DOMAIN and

$DEFAULT_BASE variables, defined on lines 71 and

74, to point to your DNS domain and your directory’s

base. For instance, to conform to the options shown in Example 8-1, set these options as follows:

$DEFAULT_MAIL_DOMAIN = "pangaea.edu"; $DEFAULT_BASE = "dc=pangaea,dc=edu";

Once this task is done, you can create LDIF files using the

appropriate scripts. Of particular interest are the

migrate_passwd.pl and

migrate_group.pl scripts, which migrate your

account database (including both /etc/passwd and

/etc/shadow) and your

/etc/group file, respectively. Both scripts

accept the name of the source file (just

/etc/passwd in the case of

migrate_passwd.pl) followed by an output file:

#./migrate_passwd.pl /etc/passwd passwd.ldif#./migrate_group.pl /etc/group group.ldif

You can examine the contents of these LDIF files, if you like. At a minimum, you might want to perform a quick check to verify that all your users have entries in the password file. You might also want to eliminate system accounts that don’t require authentication and those that you don’t want to be authenticated via the LDAP server. If you eliminate such accounts, though, be sure that they either exist in your clients’ local account databases or aren’t required by your clients.

Tip

The migration scripts can’t decrypt the already

encrypted passwords in the password database. Therefore,

they’re entered into the LDIF file using the

{crypt} encoding notation.

These scripts don’t create entries for the top-level DNs. If you haven’t created them already, you should add them to the start of each file. For the password file, the entries for the example domain are these:

dn: dc=pangaea,dc=edu objectClass: domain dc: pangaea dn: ou=People,dc=pangaea,dc=edu objectClass: organizationalUnit ou: People

The entry to add to the start of the groups file is similar:

dn: ou=Group,dc=pangaea,dc=edu objectClass: organizationalUnit ou: Group

Of course, in both cases, you must make changes to the

dn and dc lines suitable for

your organization. Once you’ve done this,

you’re ready to add the LDIF files to your LDAP

directory. You can do this with either the ldapadd

command or the slapadd command, using the

-f or -l parameters

(respectively) to pass the name of the LDIF file you want to add. You

might also want to use -v, which provides feedback

on the success of the operations. (If you use

ldapadd, though, you’ll first

need to perform additional client configurations, as described in the

next section.) For instance, these commands add both the files

created earlier:

#slapadd -v -l passwd.ldif#slapadd -v -l group.ldif

Account maintenance on an OpenLDAP server uses various utilities

whose names begin with ldap, as described

earlier. Of particular interest are ldapadd, which

adds accounts; ldapmodify, which modifies existing

accounts; and ldapdelete, which deletes accounts.

You can run these commands on any LDAP client computer (including the

LDAP server itself, if it’s properly configured as a

client); they use the network protocol to communicate with the

server.

These tools rely on the /etc/openldap/ldap.conf

configuration file. Before you can use these tools, therefore, you

should edit this file. Normally, you must set the

BASE and URI options, and

possibly point the system to a certificate file:

BASE dc=pangaea,dc=edu URI ldaps://ldap.pangaea.edu TLS_CACERT /etc/openldap/ssl/certs/slapd-cert.crt

The first of these entries should be familiar by now;

it’s the root of the LDAP directory

you’ll be using. The URI entry

points to the LDAP server, using a URI format similar to that used to

express web addresses, except that it begins with the

ldaps:// keyword. You can use

ldap:// rather than ldaps:// if

you don’t want to require the use of SSL encryption.

(The system may still negotiate TLS encryption during the session,

however.) If you specify an LDAPS port in the URI, you must point the

server to a file that contains certificates (via

TLS_CACERT) or to a directory that contains

certificate files (via TLS_CACERTDIR). You must

copy the certificate you generated on the server to this location. If

you don’t, the client tools will refuse to

communicate with the server.

In order to perform most account maintenance tasks, you must access

the server with sufficient privileges; by default, the LDAP utilities

perform anonymous accesses. You can specify a suitable high-privilege

DN with the -D option. When you do, you must also

include the -W option to have the utility prompt

you for a password. You can use the administrative DN and password

you specified in your slapd.conf.

To add an account, you should prepare an LDIF file. You can use an

entry from an LDIF file created from /etc/passwd

using migrate_passwd.pl as a model, if you like.

You can then pass this file to ldapadd:

$ ldapadd -D cn=manager,dc=pangaea,dc=edu -W -f acct.ldifTip

Because you’re passing the authentication information to the server, you don’t need type this command as root.

The ldapmodify command works in much the same way,

except that the file you pass to the utility contains modifications

to an existing entry rather than new account information. To delete

an account, you use the ldapdelete command, omit

the -f parameter, and instead pass the DN of the

account you want to delete:

$ ldapdelete -D cn=manager,dc=pangaea,dc=edu -W uid=linnaeus,ou=People, dc=pangaea,dc=eduThis example deletes the linnaeus

account in the People unit on the

LDAP server. Changing a password is similar, but you must also pass

the -S option to be prompted for the new password,

as well as changing the name of the tool:

$ldappasswd -D cn=manager,dc=pangaea,dc=edu -S -W uid=linnaeus,ou=People,dc=pangaea,dc=eduNew password: Re-enter new password: Enter LDAP Password: Result: Success (0)

Unlike the standard Linux passwd command, ldappasswd prompts for the new password before prompting for the administrative LDAP password. As with most password-handling tools, this one doesn’t echo the passwords to the screen.

Tip

The ldappasswd command isn’t

intended as a full replacement for passwd. If you

configure the /etc/pam.d/passwd file to use

LDAP, as described in Section 8.4.4 and Appendix A, the standard Linux

passwd command will change users’

passwords on the LDAP server instead of or in addition to changing

the local password when an ordinary user calls this tool. The

ldappasswd command is useful mainly when a user

has forgotten a password; you can use your LDAP administrative access

to replace the forgotten password.

If you’re used to normal Linux account maintenance tools such as useradd and userdel, these LDAP account maintenance tools may seem awkward at first. If you keep a template LDIF file handy and prepare scripts with the necessary options, DNs can save you a lot of typing and make using these tools far more intuitive.

Various additional tools exist that help manage LDAP accounts. For instance, phpLDAPadmin (http://phpldapadmin.sourceforge.net/) is a web-based tool that provides a point-and-click interface to your account database. You could also write some scripts yourself to help simplify these tasks.