The Lightweight Directory Access Protocol is the second of three cross-platform authentication tools described in this book. In reality, though, LDAP is much more than an authentication tool; it’s a protocol for accessing directories , which in this context are essentially databases designed to be read more often than they’re written. As such, LDAP can store many different types of information—Unix or Windows account databases, mappings of hostnames to IP addresses, employee contact information, and so on. This chapter focuses on one narrow use for LDAP, as a network-accessible account authentication system. LDAP makes a viable alternative to NT or Active Directory domains for network authentication of both Windows and Linux servers and desktop systems. It can provide better Linux account database integration, so it’s the smarter choice if you use many Linux systems. It can also provide much more than account authentication information, although such configurations are beyond the scope of this book. Using Linux as an LDAP platform gives you all of Linux’s usual advantages, such as its reliability and low cost.

When setting up an LDAP authentication system, you should first understand some LDAP basics. Despite the word lightweight in the protocol’s name, LDAP is a complex system, with its own terminology and peculiarities. In fact, several LDAP implementations exist, so you must pick one and install it on your Linux LDAP server. You must then set up your directories to handle authentication. Only then can you begin configuring your LDAP clients to use your network’s account directory. (Note that LDAP clients can be servers for other protocols.) Of course, the details of this configuration vary between Linux and Windows clients, so you must know how to handle both.

Tip

You can use a non-Linux LDAP server for authentication. In fact, if you currently use a Windows 200x Active Directory domain controller, it already runs LDAP. You can use this server to authenticate users on Linux systems, but you need to add Unix-style account information to the LDAP directories. Alternatively, you can configure the Linux systems to access the Windows server as an NT domain controller, as described in Chapter 7. This solution requires no changes on the Windows LDAP server and so is likely to be slightly simpler to configure.

At its core, LDAP is a protocol for exchanging data between computers. The LDAP protocol has been independently implemented in several packages, but understanding what problems LDAP is intended to solve will help you understand its features and implementations. As a practical matter, you must also pick an LDAP implementation to run on your LDAP server, as well as LDAP clients for systems that should authenticate against the server.

Directories, and LDAP in particular, are tools for storing data. At this level of analysis, directories are similar to databases. In order to understand directories, though, you should understand a couple of key differences between directories and databases:

Directories are designed to be read more often than they’re written; databases are designed for more equal distribution of read and write accesses. This characteristic simplifies many aspects of a directory’s design and can lead to faster lookups in directories.

The internal structure of databases is designed to support easy sorting and cross-referencing, but the entries are otherwise unstructured. Directories, by contrast, use a hierarchical structure but are less easily sorted than database entries.

LDAP provides tools that enable accessing directories across a network, with the goal of centralizing this information. The central directory can host a variety of information. For instance, it might hold individuals’ computer account information, telephone numbers, office numbers, birth dates, departmental affiliations, and so on. This information is unlikely to change frequently, and individuals throughout an organization may have need to access it. Thus, a network-accessible directory protocol is the ideal way to store such information.

Tip

LDAP, and directories more generally, can handle more than just account or even personal information. For instance, you might store computer help documentation in a directory. This chapter focuses on LDAP as a tool for storing computer account information. For more information on LDAP, including additional potential uses, consult a book on the subject, such as LDAP System Administration (O’Reilly).

One important characteristic of LDAP is that it’s a protocol description. The actual data storage can be in any of several different forms, depending on the features of the LDAP server you choose. For instance, an LDAP server might use plain-text files, a proprietary binary format, or a well-documented database file format. The choice of backend data file format doesn’t affect the operations that can be performed by clients, but it may influence the server’s overall performance level.

LDAP documentation is filled with its own jargon. Some LDAP terms should be familiar to most Linux administrators, but some of it is unique or used oddly:

- Directory

This term, as already described, refers to a data-storage system. Note that the term is unrelated to a filesystem directory, although the two types of directories do have certain common features, such as being methods of data storage. A directory tree refers to the entire collection of structured entries in the directory.

- Attributes

An LDAP attribute is similar to a variable in a programming language; it’s a named identifier for data stored in the directory. Attributes, though, can sometimes hold multiple values.

- Object class

Every entry in a directory is a member of an object class, which defines a collection of attributes for data. You set the object class by setting the

objectClassattribute to a particular value. For instance, when using LDAP to handle accounts, you’ll use theposixAccountclass, among others. This class defines attributes calleduid,userPassword, and so on, to store account information.- Schema

This is a way to define several object classes at once. LDAP implementations ship with standardized schema files that provide many predefined object classes, including some that are useful for handling user accounts. (The schema is a structure for holding data, not the data itself.)

- DC

A domain component identifies the scope of an entry or of an entire tree. Typically, you’ll set

dc=attributes that correspond to your DNS domain or subdomain name.- DN

A distinguished name is the name of an attribute along with a description of where the entry belongs in the directory tree. It’s described in more detail later in this chapter.

- OU

An organizational unit is a common subdivision in a directory. It’s often used to separate departments from one another within a single organization, enabling (for instance) duplication of usernames in two different departments.

- LDIF

The LDAP Data Interchange Format describes information in a way that LDAP can understand. It’s covered in more detail later in this chapter.

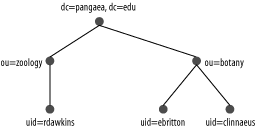

LDAP directories are often represented in graphical form, such as

that shown in Figure 8-1. In practice, these trees

are constructed through the data you place in individual entries,

which appear at the nodes in the tree. The topmost entry in the tree

(dc=pangaea,dc=edu in Figure 8-1), or its root, defines the naming context of

the directory. In this example, the naming context includes two DCs,

which together are equivalent to the http://www.pangaea.edu DNS domain.

Of course, you need actual software to implement an LDAP server. In Linux, the most popular LDAP package is OpenLDAP, which is headquartered at http://www.openldap.org. Other LDAP packages are available, though, and some are popular on non-Linux systems. The most notable of these is probably Microsoft’s Active Directory, which incorporates LDAP and Kerberos functionality. Other products include Sun’s SunOne and Novell’s eDirectory.

Because OpenLDAP is the most common LDAP package for Linux, the rest of this chapter uses it as an example, at least for server operations. In particular, this chapter describes OpenLDAP 2.2. LDAP client configuration should be the same even if you use another LDAP server, though. Many details differ for other LDAP servers, so if you choose to use one, you’ll have to consult its documentation to learn how it differs from OpenLDAP.