Practical Electronic Recipes

with Arduino and Raspberry Pi

Copyright © 2017 Simon Monk. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com/safari). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491953402 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Electronics Cookbook, the cover image of an elephantnose fish, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

978-1-491-95340-2

[LSI]

Traditional wisdom requires people using electronics to have at least an EE degree before they can do anything useful, but in this book the whole subject of electronics is given the highly respected O’Reilly Cookbook treatment and is broken down into recipes. These recipes make it possible for the reader to access the book at random, following the recipe that solves their problem and learning as much or as little about the theory as they are comfortable with.

While it is impossible to cover in one volume everything in a complex and wide-ranging subject like electronics, I have tried to select recipes that seem to come up most frequently when I talk to other makers, hobbyists, and inventors.

If you are into electronics or want to get into electronics, then this is the book that will help you get more from your hobby. The book is full of built-and-tested recipes that you can trust to do just what you need them to do, no matter what your level of expertise.

If you are new to electronics then this book will serve as a guide to get you started; if you are an experienced electronics maker, it will act as a useful reference.

This book has been gestating for a while. I believe that the original concept came from no less a person than Tim O’Reilly himself. The idea was to fill the gap in the market between books like the Arduino Cookbook and the Raspberry Pi Cookbook and heavyweight electronics textbooks.

In other words, to cover more of the fundamentals of electronics and topics peripheral to the use of microcontrollers that often get neglected, except in heavyweight electronic tomes. Topics such as how to construct various types of power supply, using the right transistor for switching, using analog and digital ICs, as well as how to construct projects and prototypes and use test equipment.

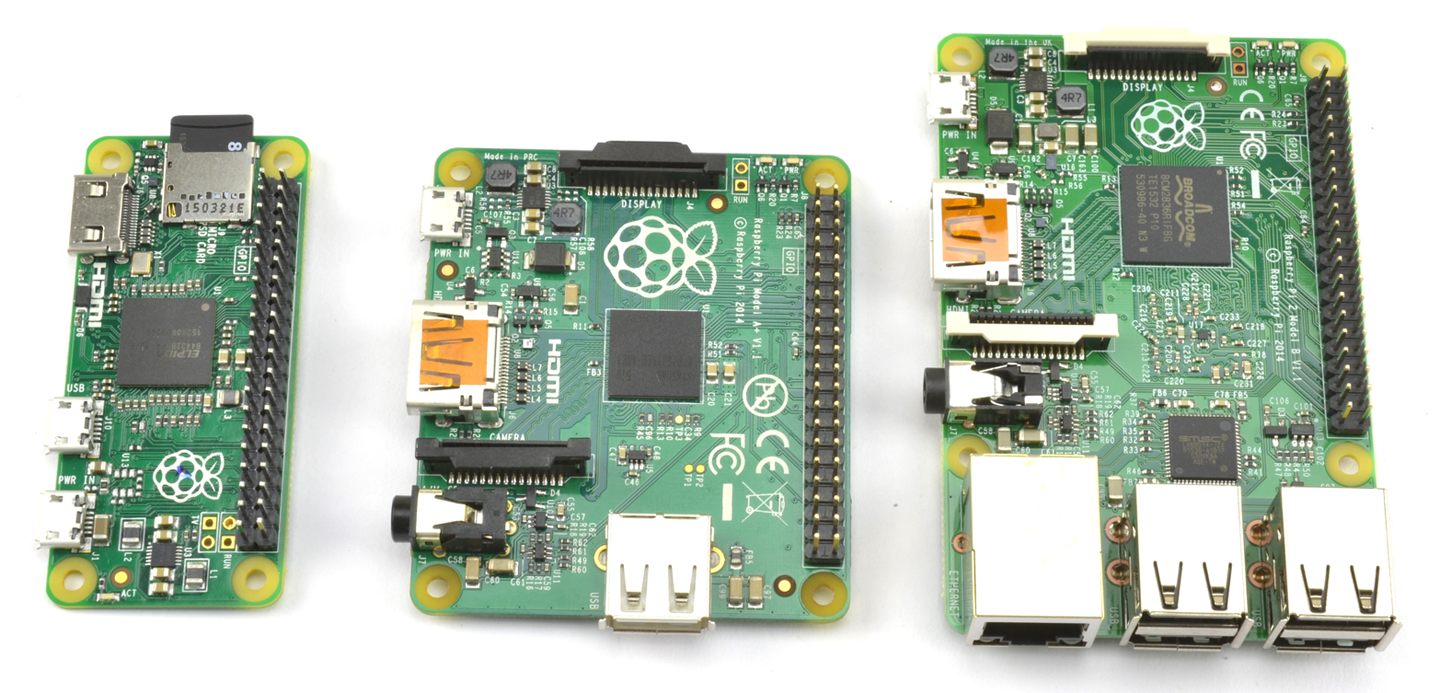

Boards like the Arduino and Raspberry Pi have lured whole new generations of makers, hobbyists, and inventors into the world of electronics. Components and tools are now low cost and within the reach of more people than at any time in history. Hackspaces and Fab Labs have electronic workstations where you can use tools to realize your projects.

The free availability of information including detailed designs means that you can learn from and adapt other people’s work for your own specific needs.

Many people who start with electronics as a hobby progress to formal education in electronic engineering, or just jump straight to product design as an inventor and entrepreneur. After all, if you have access to a computer and a few tools and components, you can build a working prototype of your great invention and then find someone to manufacture it for you, all financed with the help of crowdfunding. The barrier of entry to the electronics business is at an all-time low.

As a “cookbook” you can dive in and use any recipe, rather than read the book in order. Where you have a recipe that relies on some knowledge or skills from another recipe, there will be a link back to the prerequisite recipe.

The recipes are arranged in chapters, with Chapters 1 to 6 providing more fundamental recipes, some concerning theory but mostly about different types of component (your recipe ingredients). These chapters are:

The next section of chapters looks at how the components introduced in the first section can be used together in various recipes covering pretty much anything electronic that you might like to design.

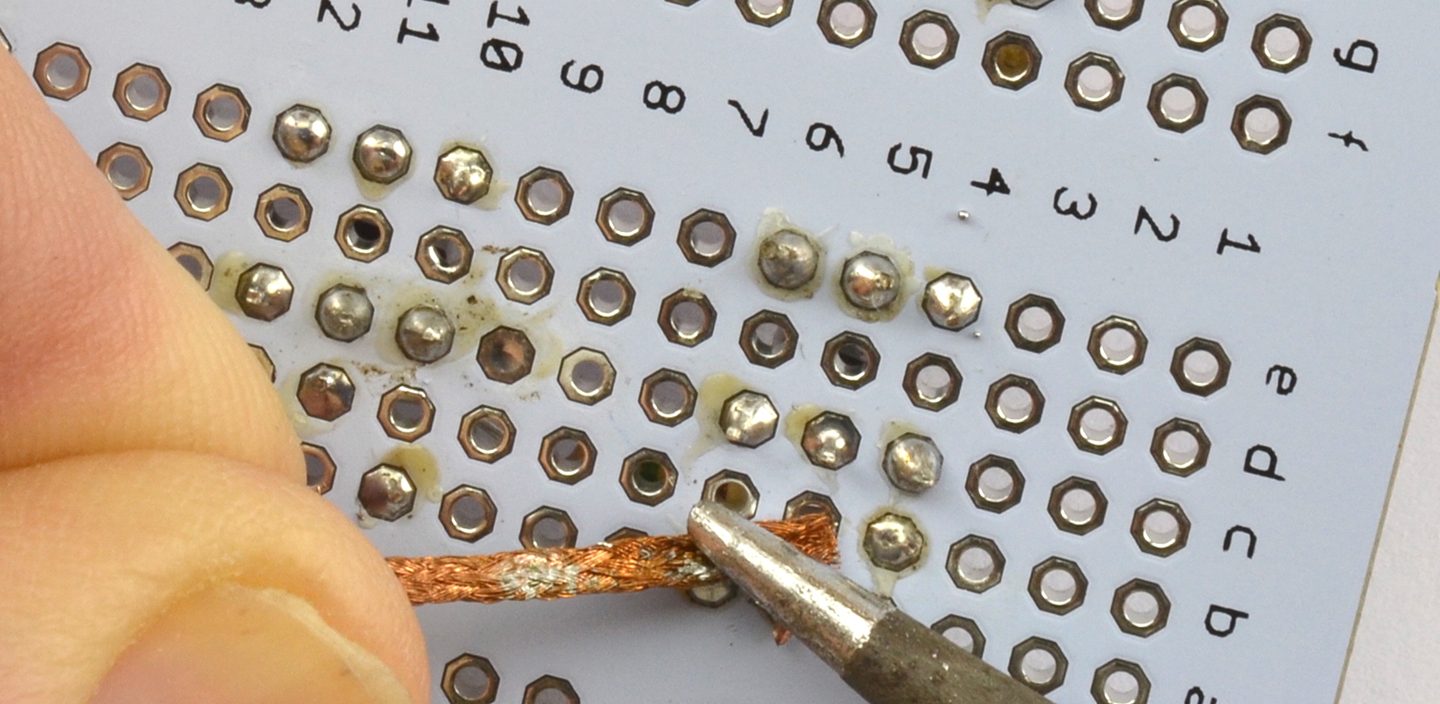

The final section of the book contains recipes for construction and the use of tools.

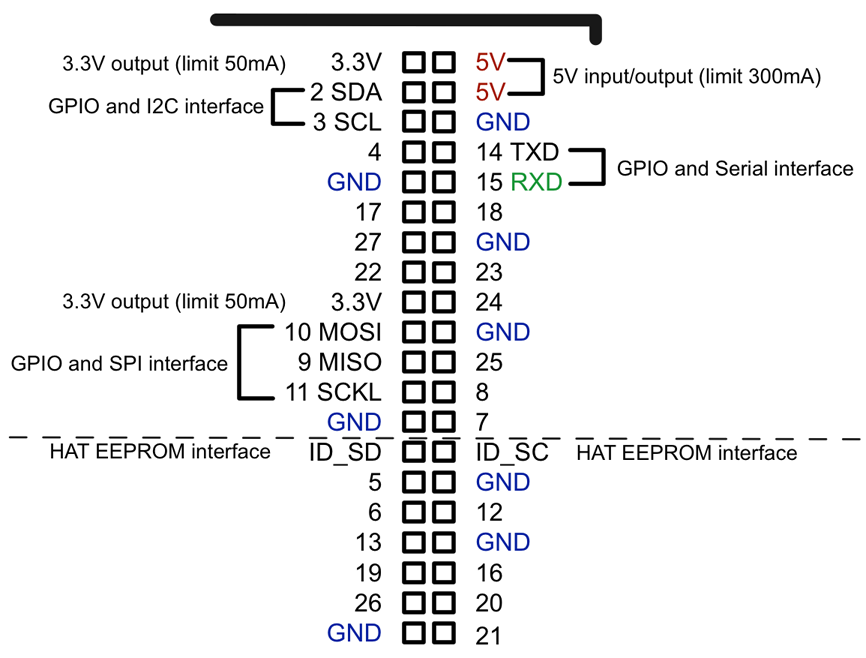

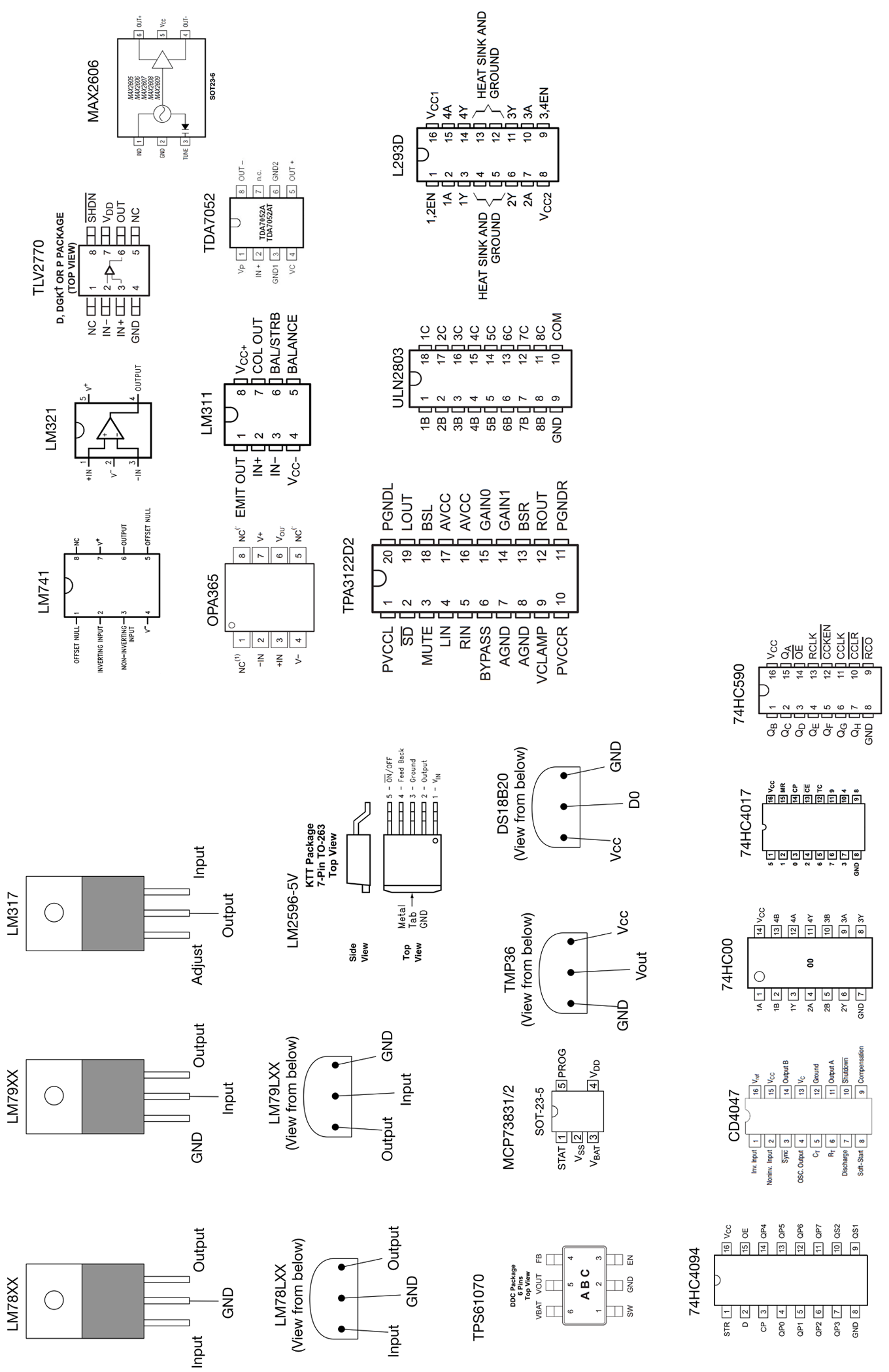

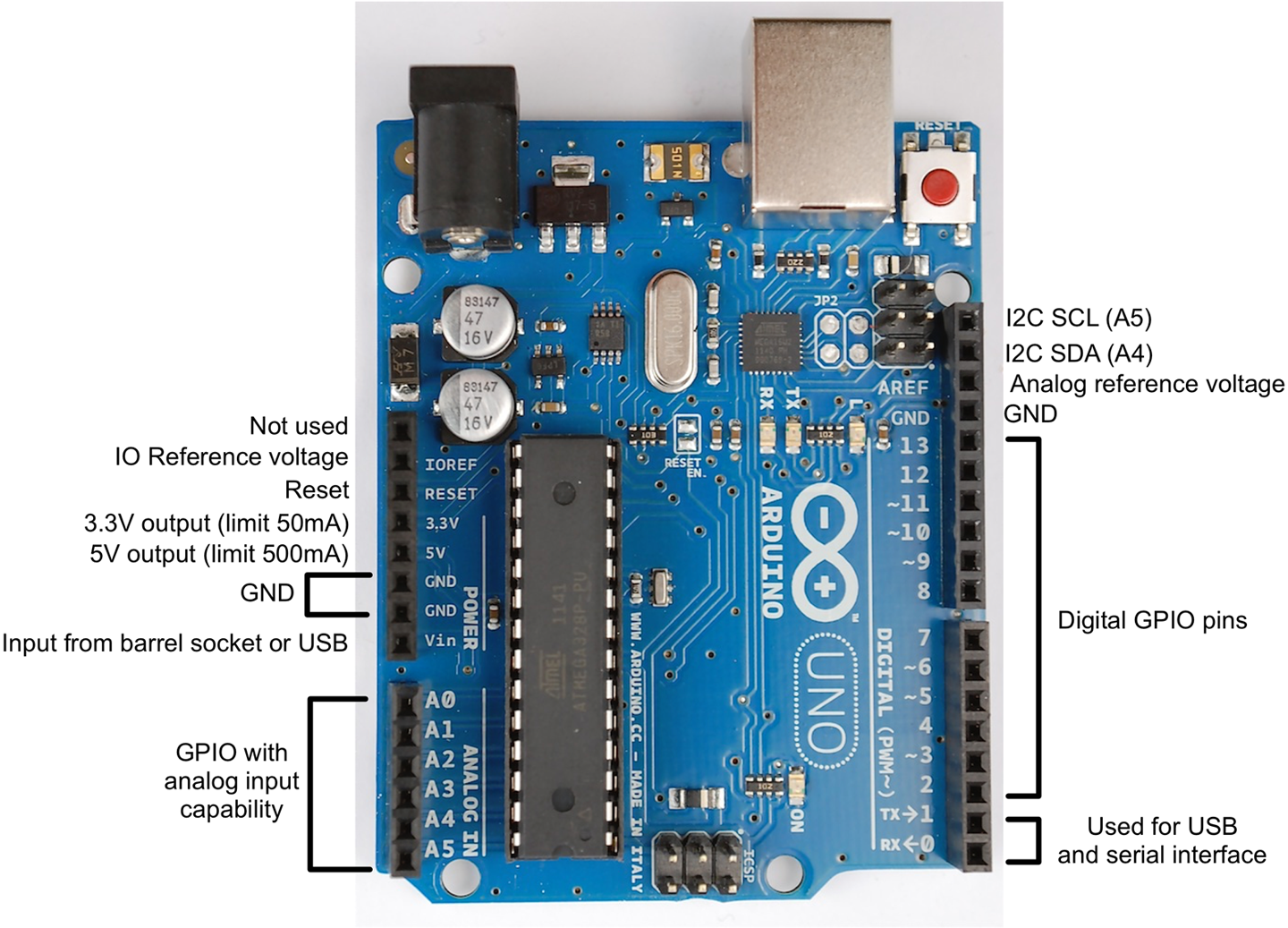

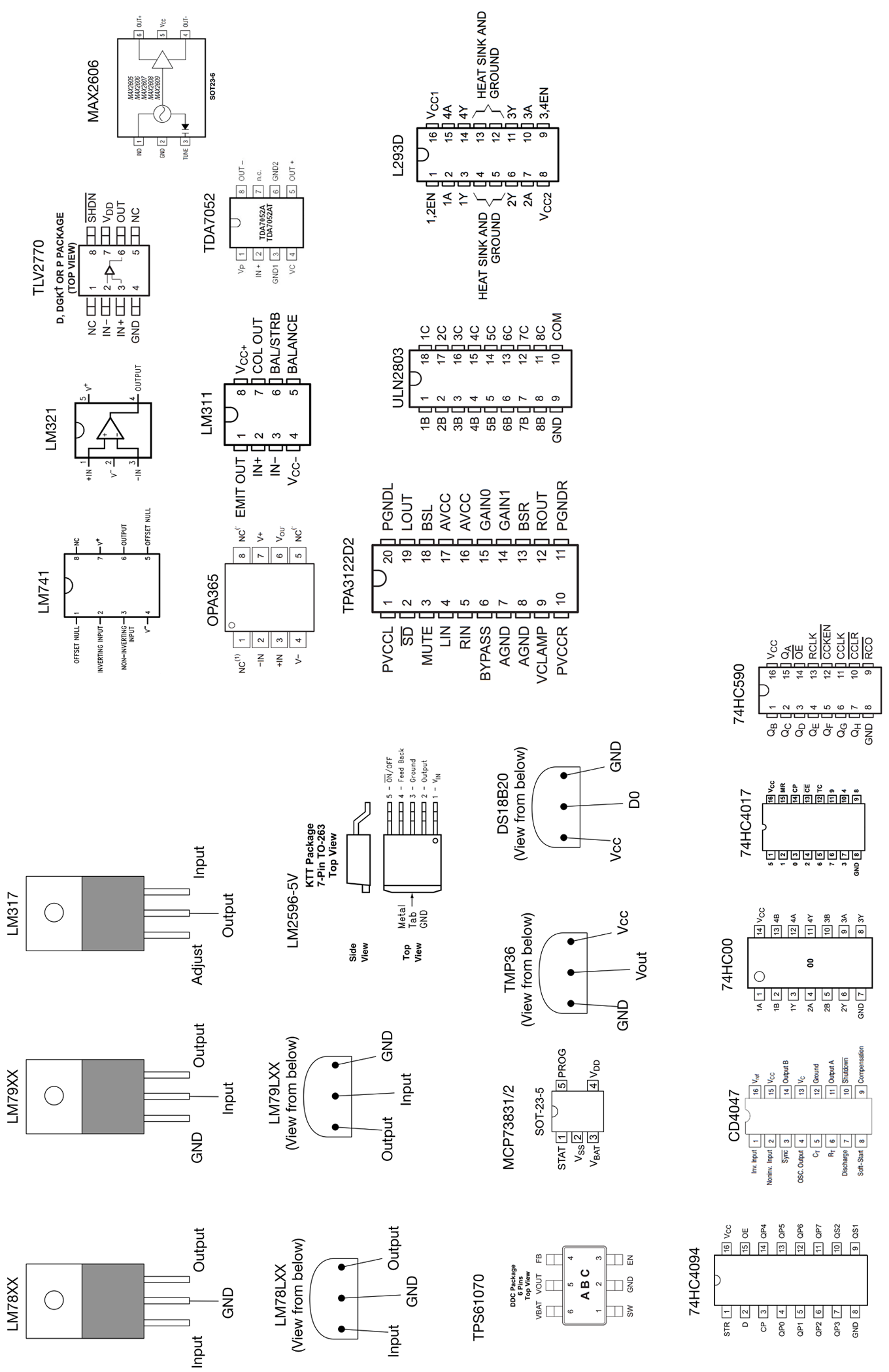

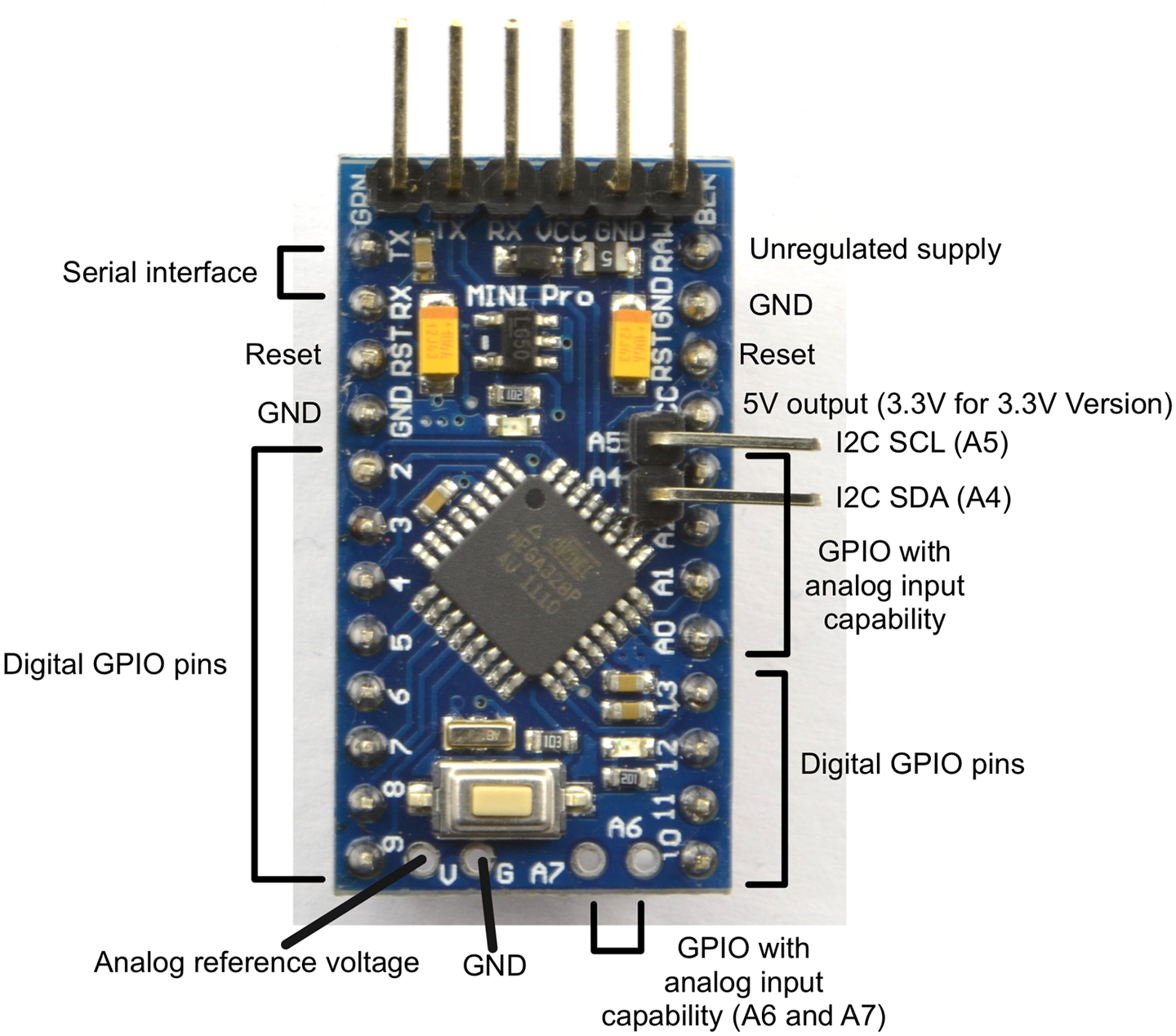

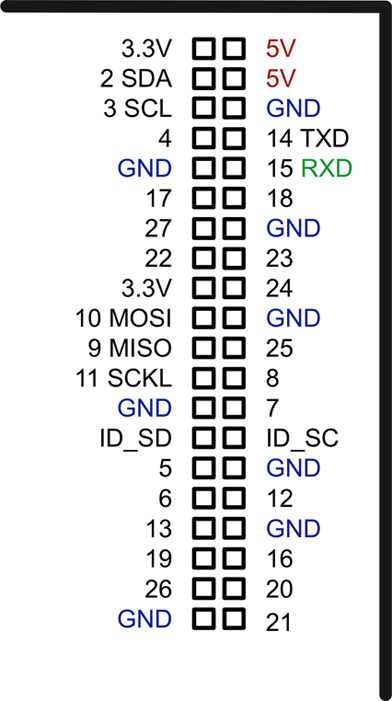

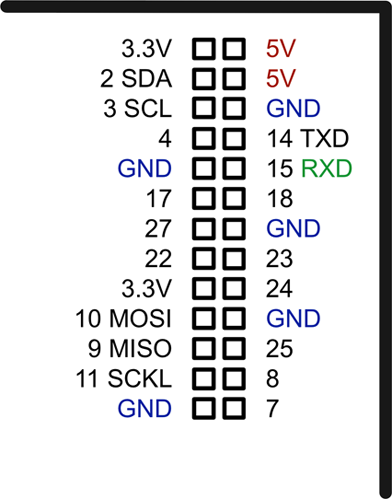

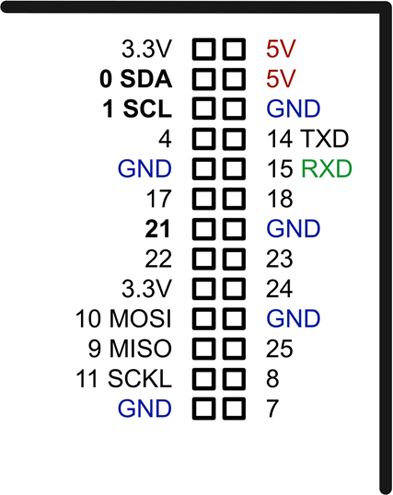

The book also includes appendices that list all the parts used in the book along with useful suppliers and provide pinouts for devices including the Arduino and Raspberry Pi.

There are many wonderful resources available for the electronics enthusiast.

If you are looking for project ideas then sites like Hackaday and Instructables are a great source of inspiration.

When it comes to getting help with a project, you will often get great advice from the many experienced and knowledgable people that hang out on the following forums. Remember to search the forum before asking your question, in case it has come up before (usually it has) and always explain your question clearly, or “experts” can get impatient with you.

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant widthUsed for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width boldShows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italicShows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values determined by context.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/simonmonk/electronics_cookbook.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing a CD-ROM of examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “Electronics Cookbook by Simon Monk (O’Reilly). Copyright 2017 Simon Monk, 978-1-491-95340-2.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

Safari (formerly Safari Books Online) is a membership-based training and reference platform for enterprise, government, educators, and individuals.

Members have access to thousands of books, training videos, Learning Paths, interactive tutorials, and curated playlists from over 250 publishers, including O’Reilly Media, Harvard Business Review, Prentice Hall Professional, Addison-Wesley Professional, Microsoft Press, Sams, Que, Peachpit Press, Adobe, Focal Press, Cisco Press, John Wiley & Sons, Syngress, Morgan Kaufmann, IBM Redbooks, Packt, Adobe Press, FT Press, Apress, Manning, New Riders, McGraw-Hill, Jones & Bartlett, and Course Technology, among others.

For more information, please visit http://oreilly.com/safari.

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at http://bit.ly/electronics-cookbook.

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

For more information about our books, courses, conferences, and news, see our website at http://www.oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: http://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: http://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/oreillymedia

Thanks to Duncan Amos, David Whale, and Mike Bassett for their technical reviews of the book and the many useful comments that they provided to help make this book as good as it could be.

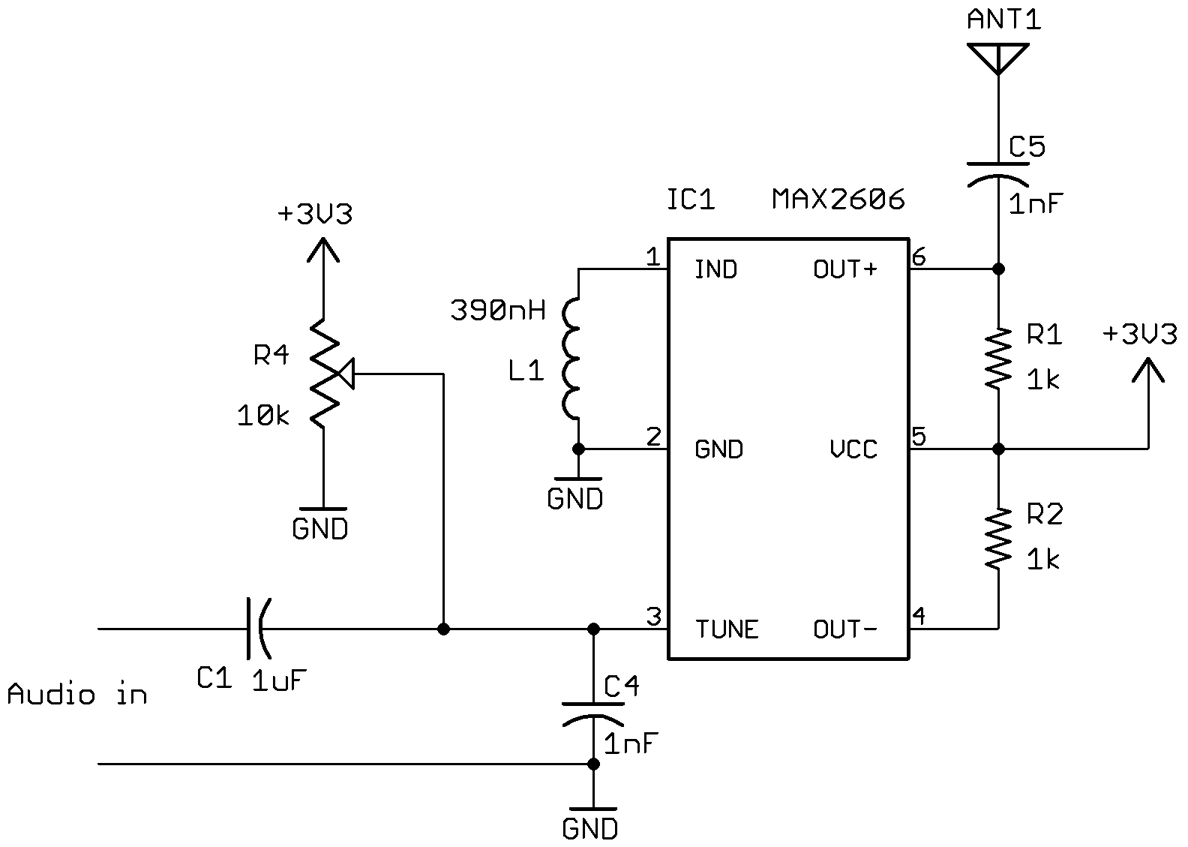

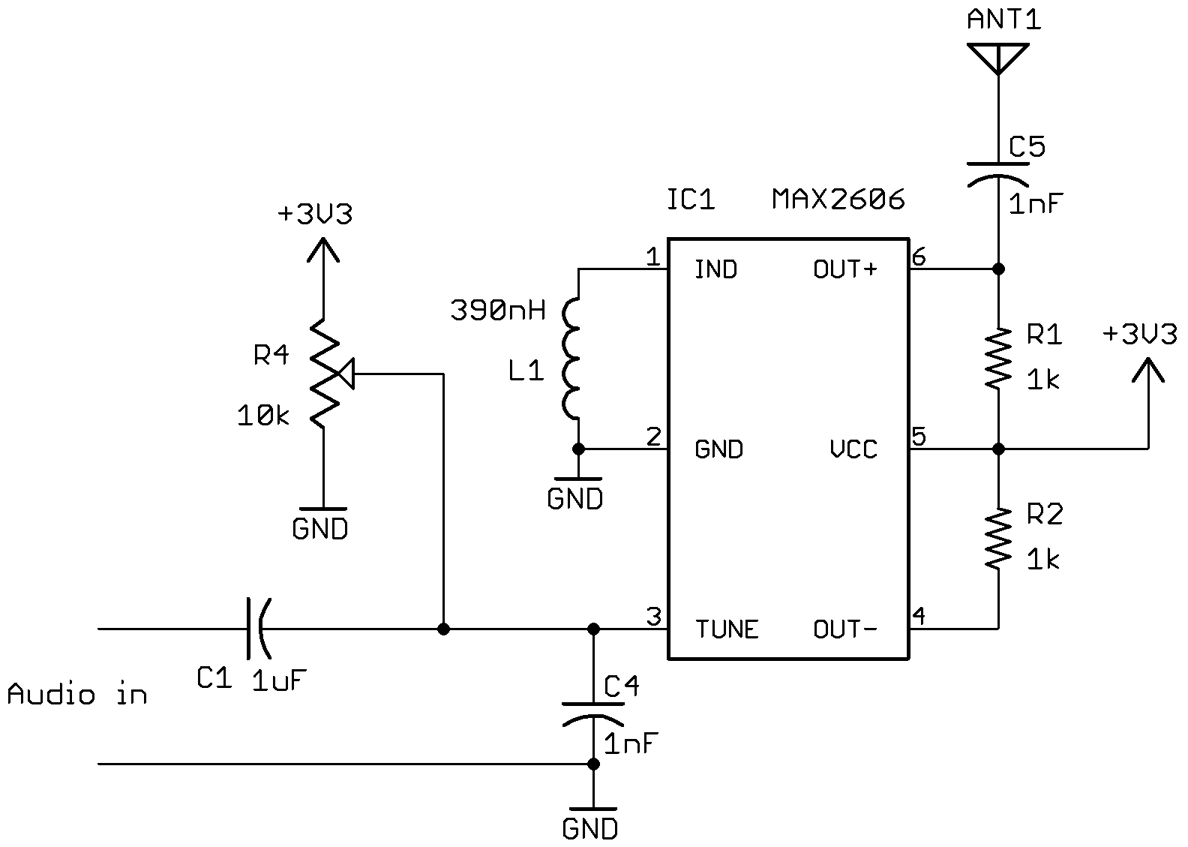

I’d also like to thank Afroman for permission to use his great FM transmitter design and the guys at Digi-Key for their help in compiling parts codes.

As always, it’s been a pleasure working with the professionals at O’Reilly, in particular Jeff Bleiel, Heather Scherer, and of course, Brian Jepson.

Although this book is fundamentally about practice rather than theory, there are a few theoretical aspects of electronics that are almost impossible to avoid.

In particular, if you understand the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance many other things will make a lot more sense.

Similarly, the relationship between power, voltage, and current crops up time and time again.

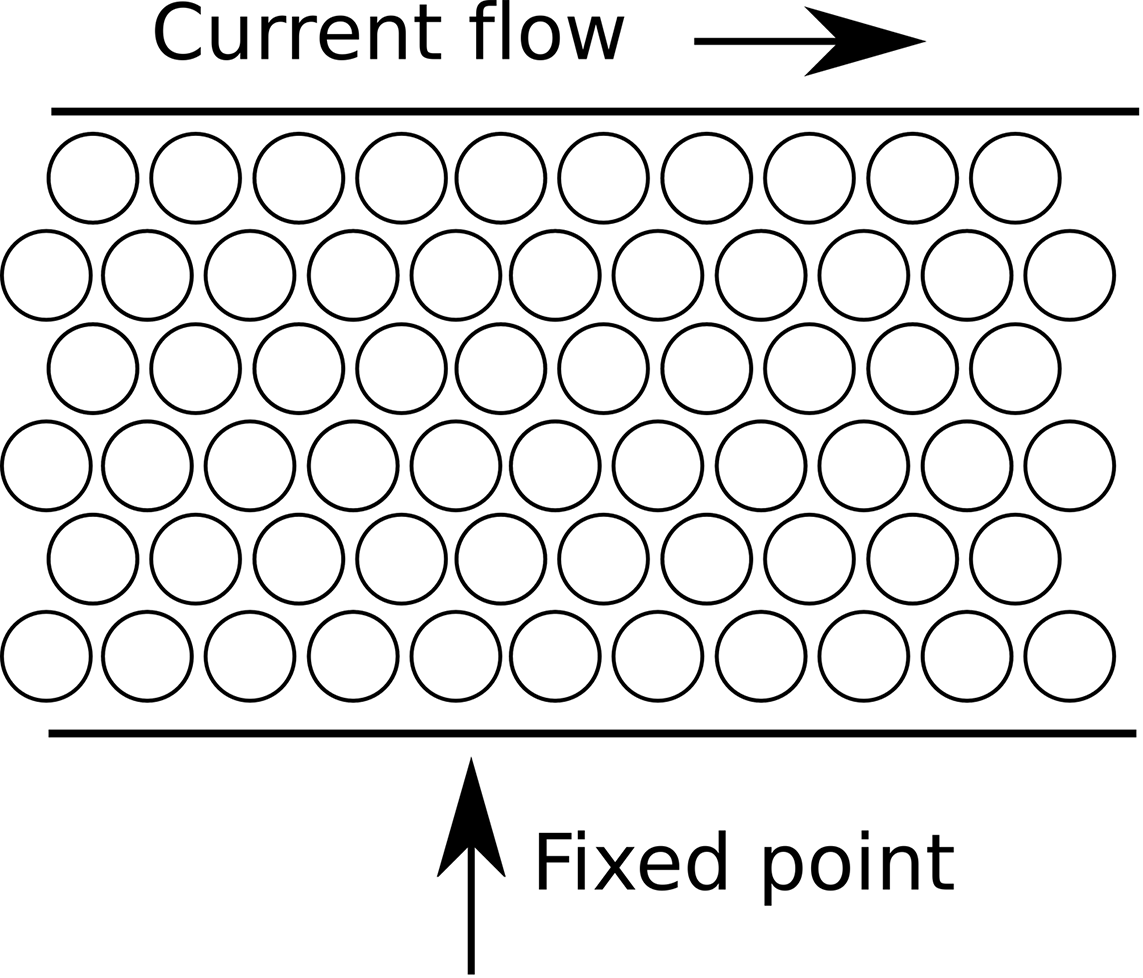

As the word current suggests, the meaning of current in electronics is close to that of the current in a river. You could think of the strength of the current in a pipe as being the amount of water passing a point in the pipe every second. This might be measured in so many gallons per second.

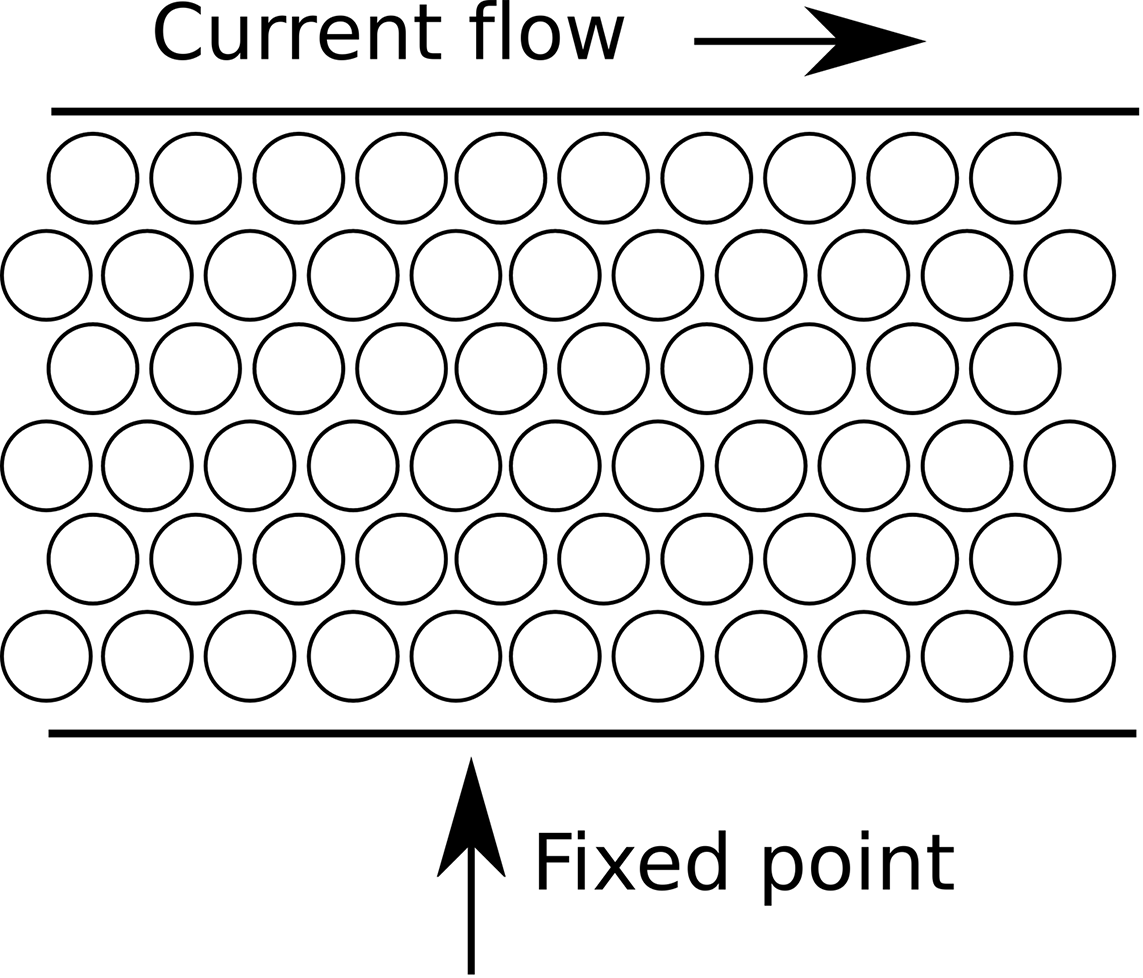

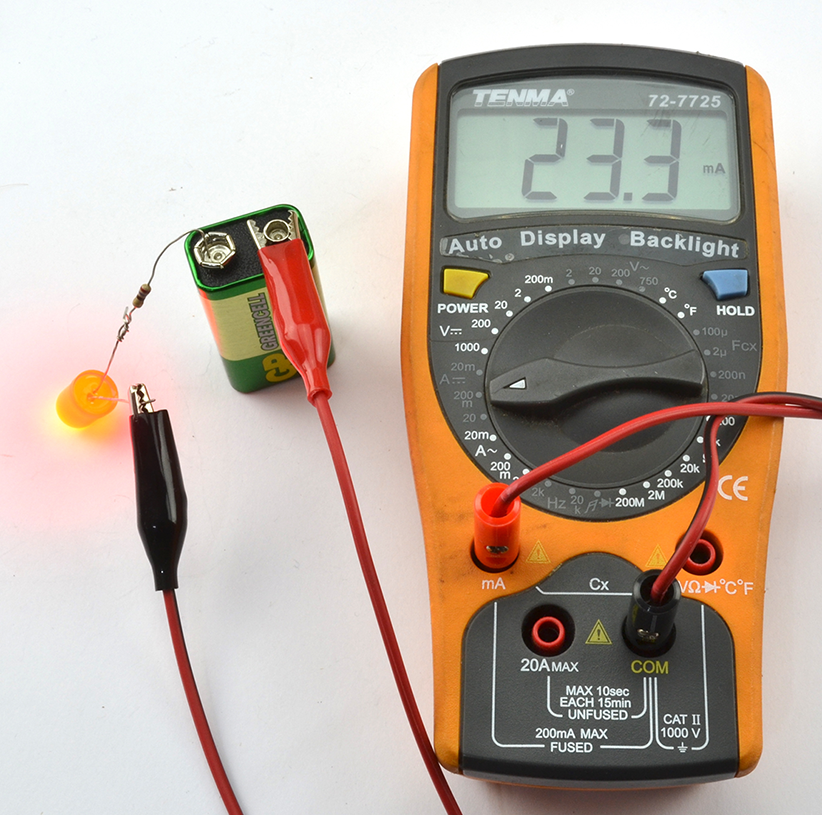

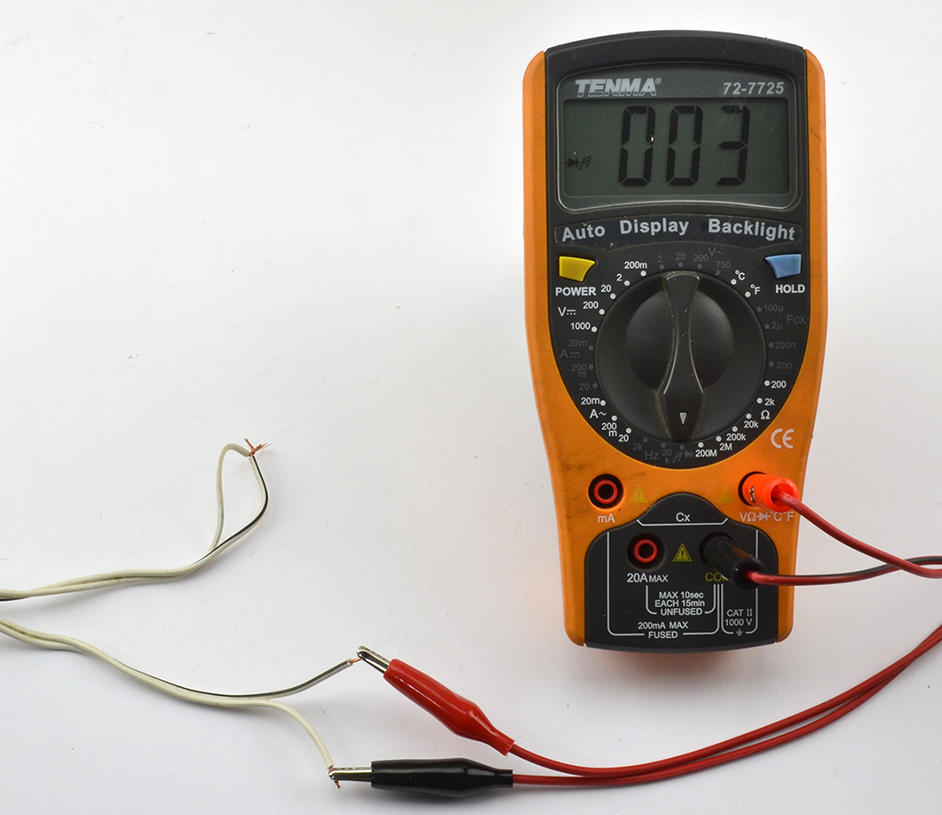

In electronics, current is the amount of charge carried by electrons passing a point in a wire per second (Figure 1-1). The unit of current is the ampere, abbreviated as amp or as unit symbol A.

For a list of units and unit prefixes such as mA, see Appendix D.

To learn more about current in a circuit, see Recipe 1.4.

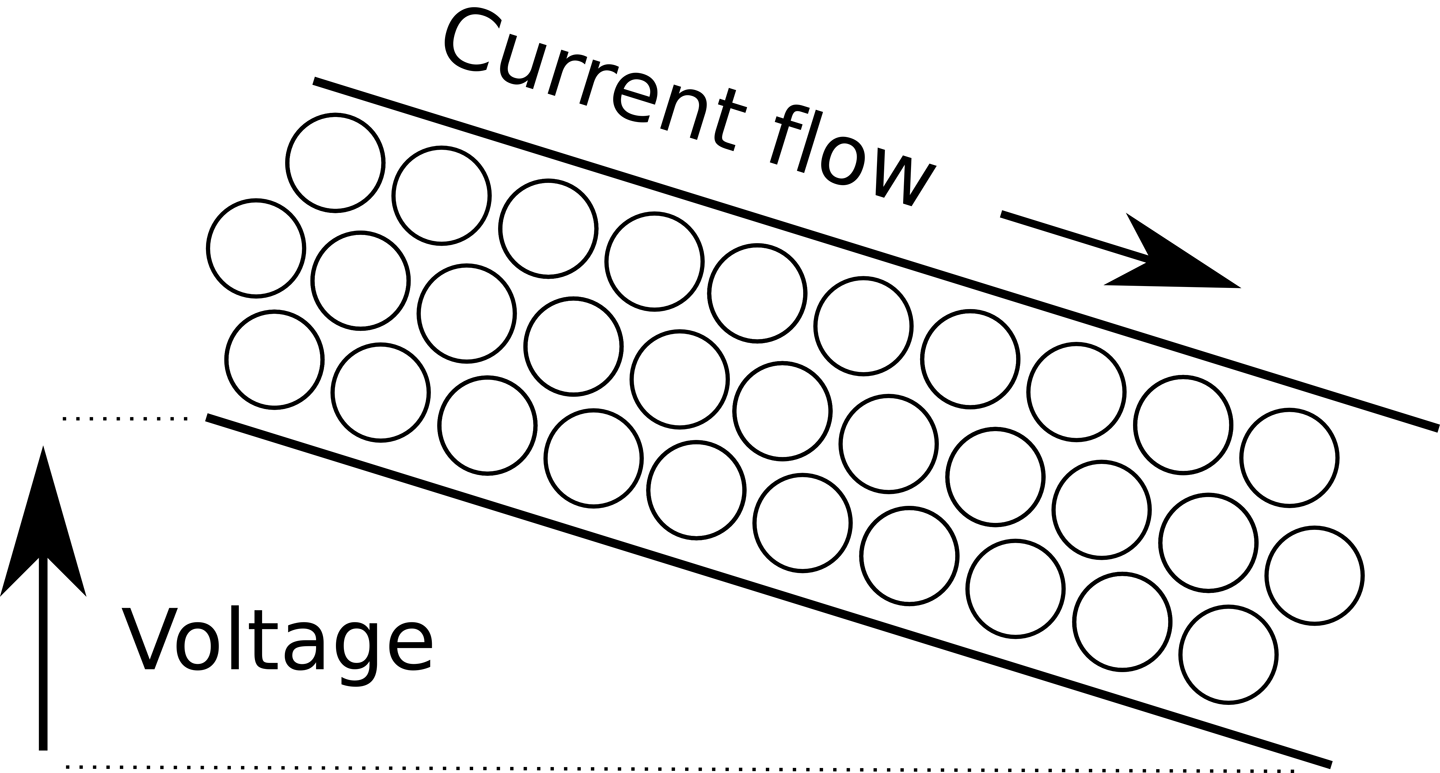

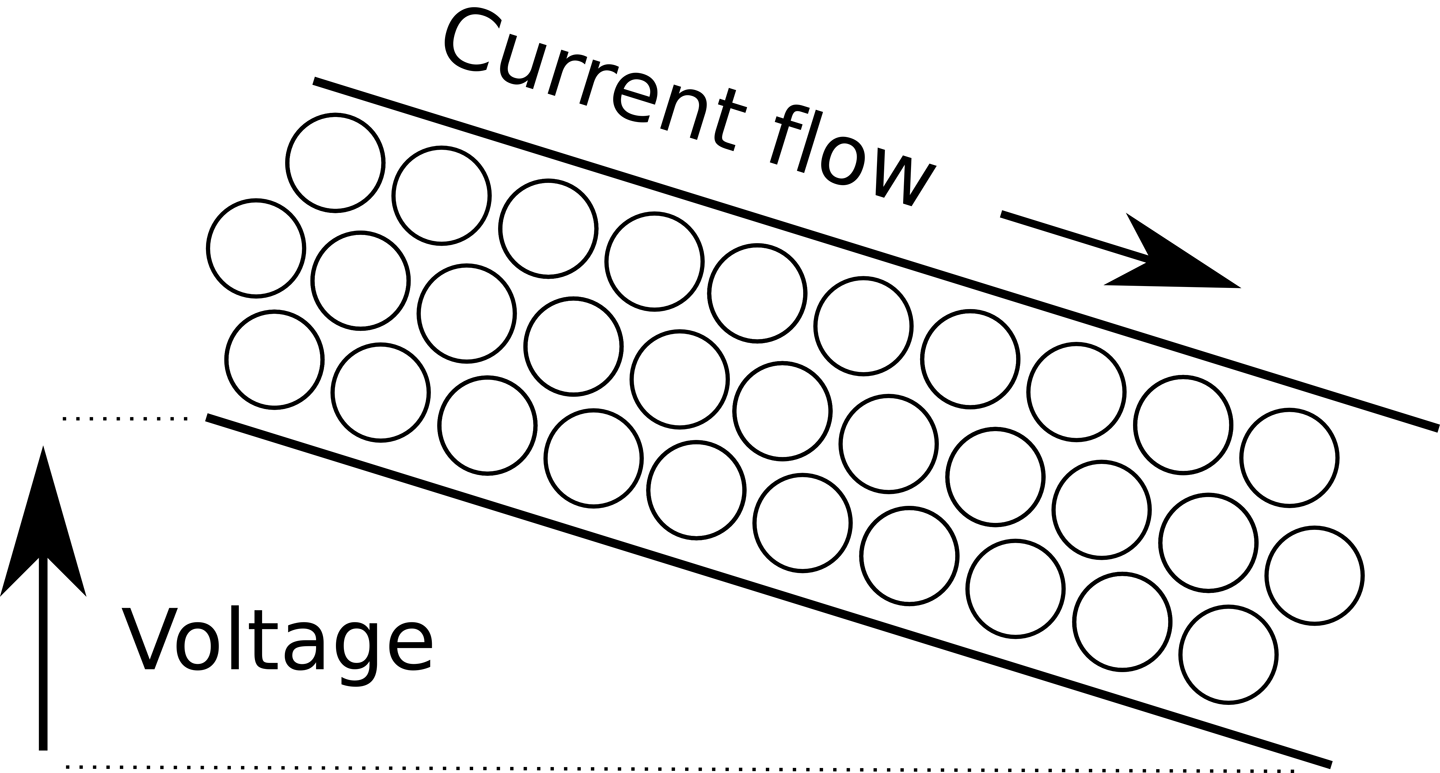

In Recipe 1.1 you read how current is the rate of flow of charge. That current will not flow without something influencing it. In a water pipe, that might be because one end of the pipe is higher than the other.

To understand voltage, it can be useful to think of it as being similar to height in a system of water pipes. Just like height, it is relative, so the height of a pipe above sea level does not determine how fast the water flows through a pipe, but rather how much higher one end of the pipe is than the other (Figure 1-2).

Voltage might refer to the voltage across a wire (from one end to the other) and in other situations, it might refer to the voltage from one terminal of a battery to another. The common feature is that for voltage to make any sense, it must refer to two points; the higher voltage is the positive voltage, marked with a +.

It is the difference in voltage that makes a current flow in a wire. If there is no difference in voltage between one end of a wire and another then no current will flow.

The unit of voltage is the volt. An AA battery has about 1.5V across its terminals. An Arduino operates at 5V, while a Raspberry Pi operates at 3.3V, although it requires a 5V supply that it reduces to 3.3V.

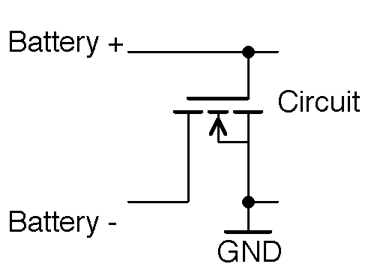

Sometimes it seems like voltage is used to refer to a single point in an electronic circuit rather than a difference between two points. In such cases the voltage then means the difference between the voltage at one point in the circuit and ground. Ground (usually abbreviated as GND) is a local reference voltage against which all other voltages in the circuit are measured. This is, if you like, 0V.

To learn more about voltages, see Recipe 1.5.

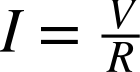

Use Ohm’s Law.

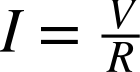

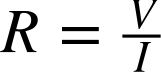

Ohm’s Law states that the current flowing through a wire or electronic component (I) will be the voltage across that wire or component (V) divided by the resistance of the component (R). In other words:

If it is the voltage that you want to calculate, then this formula can be rearranged as:

And, if you know the current flowing through a resistor and the voltage across the resistor, you can calculate the resistance using:

Resistance is the ability of a substance to resist the flow of current. A wire should have low resistance, because you do not usually want the electricity flowing through the wire to be unnecessarily impeded. The thicker the wire, the less its resistance for a given length. So a few feet of thin wire that you might find connecting a battery to a lightbulb (or more likely LED) in a flashlight might have a resistance of perhaps 0.1Ω to 1Ω, whereas the same length of thick AC outlet cable for a kettle may have a resistance of only a couple of milliohms (mΩ).

It is extremely common to want to limit the amount of current flowing through part of a circuit by adding some resistance in the form of a special component called a resistor.

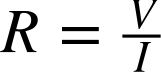

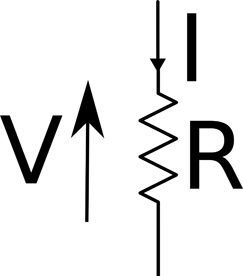

Figure 1-3 shows a resistor (zig-zag line) and indicates the current flowing through it (I) and the voltage across it (V).

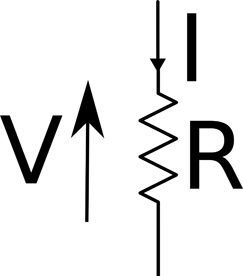

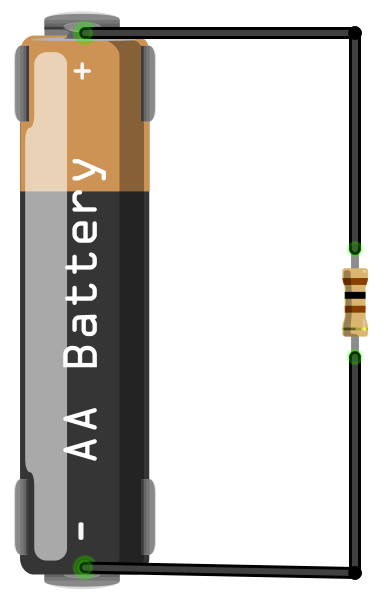

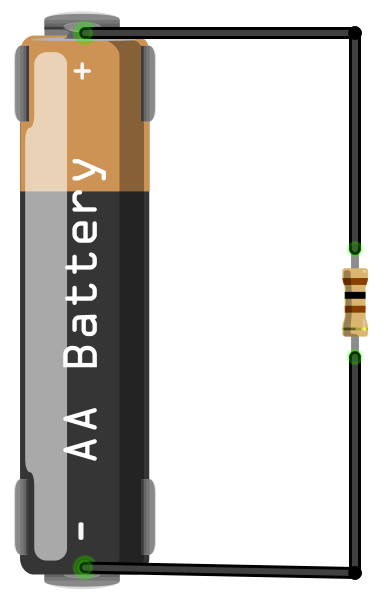

Let’s say that we were to connect a 1.5V battery to a 100Ω resistor as shown in Figure 1-4. The Greek letter Ω (omega) is used as shorthand for the unit of resistance (the “Ohm”).

Using Ohm’s Law, the current is the voltage across the resistor divided by the resistance of the resistor (we can assume that the wires have a resistance of zero).

So, I = 1.5 / 100 = 0.015 A or 15mA.

To understand what happens to current flowing through resistors and wires in a circuit, see Recipe 1.4.

To understand the relationship between current, voltage, and power, see Recipe 1.6.

Use Kirchhoff’s Current Law.

Stated simply, Kichhoff’s Current Law says that at any point on a circuit, the current flowing into that point must equal the current flowing out.

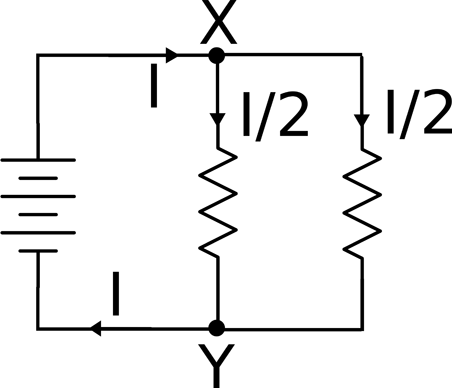

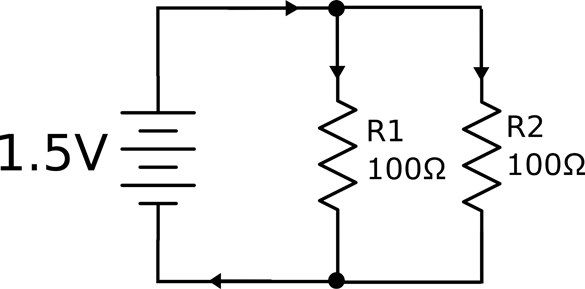

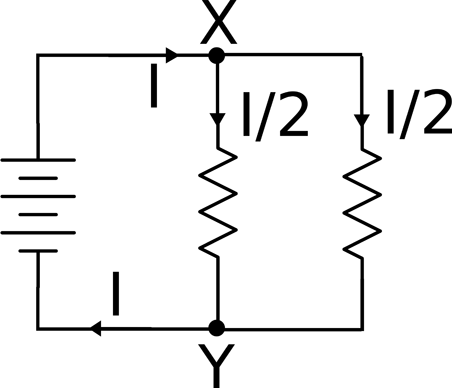

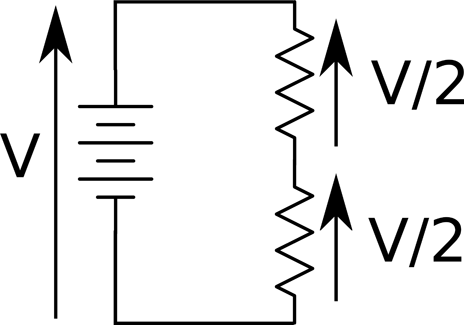

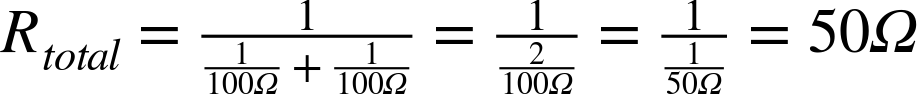

For example, in Figure 1-5 two resistors are in parallel and supplied with a voltage from a battery (note the schematic symbol for a battery on the left of Figure 1-5).

At point X, a current of I will be flowing into point X from the battery, but there are two branches out of X. If the resistors are of equal value then each branch will have half the current flowing through it.

At point Y, the two paths recombine and so the two currents of I/2 flowing into Y will be combined to produce a current of I flowing out of Y.

For Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law, see Recipe 1.5.

For further discussion on resistors in parallel, see Recipe 2.5.

Use Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law.

This law states that all the voltages between various points around a circuit will add up to zero.

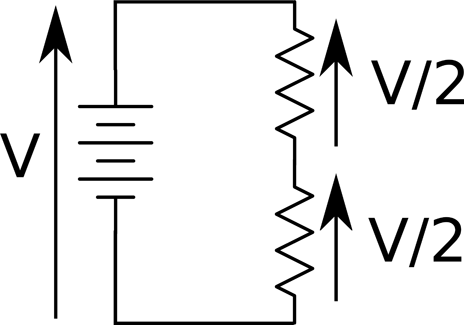

Figure 1-6 shows two resistors in series with a battery. It is assumed that the two resistors are of equal value.

At first glance it is not clear how Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law applies until you look at the polarity of the voltage. On the left, the battery supplies V volts, which is equal in magnitude, but opposite in direction (and hence sign) to the two voltages V/2 across each resistor.

Another way to look at this is that V must be balanced by the two voltages V/2. In other words, V = V/2 + V/2 or V – (V/2 + V/2) = 0.

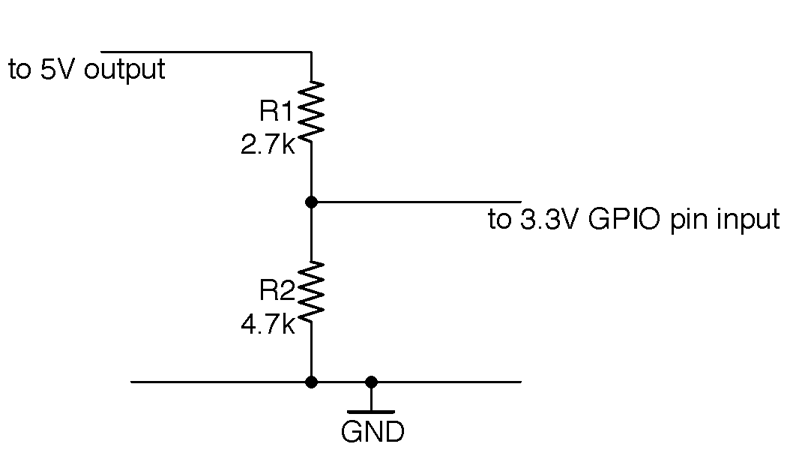

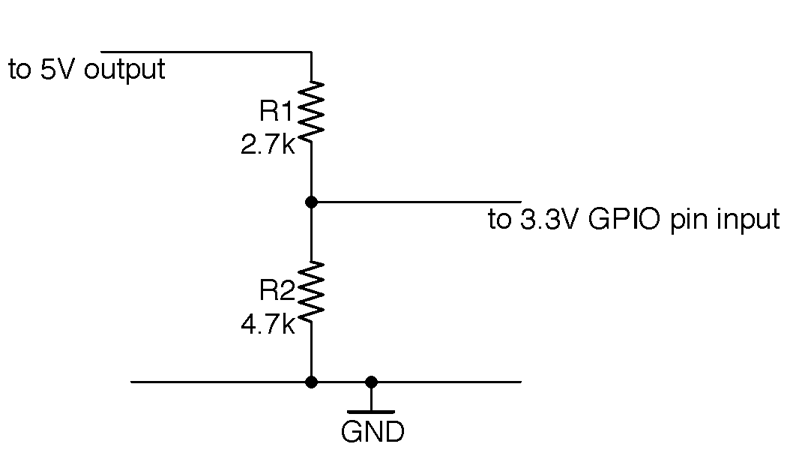

This arrangement of a pair of resistors is also used to scale voltages down (see Recipe 2.6).

For Kirchhoff’s Current Law, see Recipe 1.4.

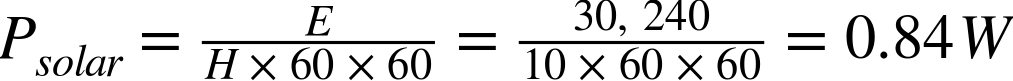

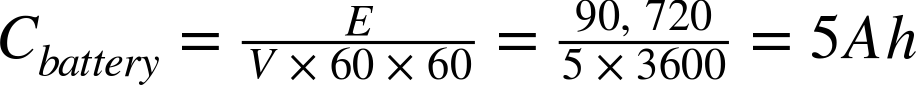

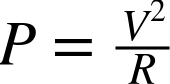

In electronics, power is the rate of conversion of electrical energy to some other form of energy (usually heat). It is measured in Joules of energy per second, which is also known as a watt (W).

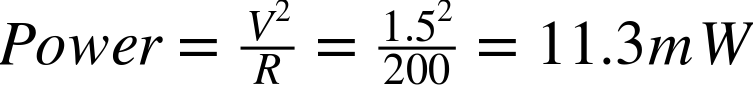

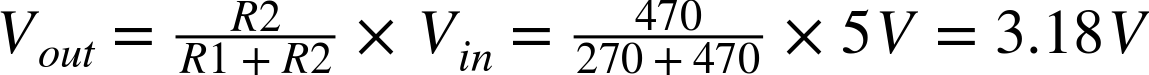

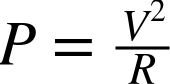

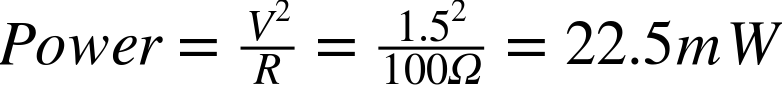

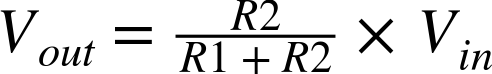

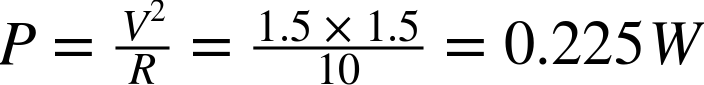

When you wire up a resistor as shown back in Figure 1-4 of Recipe 1.3 the resistor will generate heat and if it’s a significant amount of heat then the resistor will get hot. You can calculate the amount of power converted to heat using the formula:

P = I x V

In other words, the power in watts is the voltage across the resistor (in volts) multiplied by the current flowing through it in amps. In the example of Figure 1-4 where the voltage across the resistor is 1.5V and the current through it was calculated as 15mA, the heat power generated will be 1.5V x 15mA = 22.5mW.

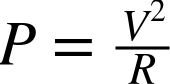

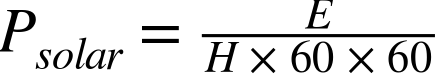

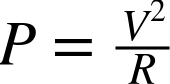

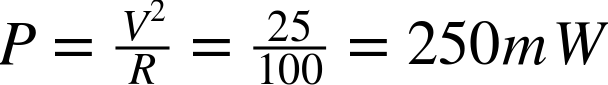

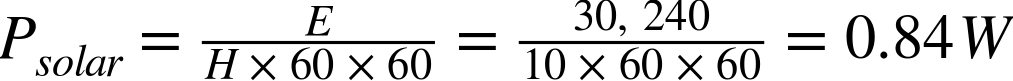

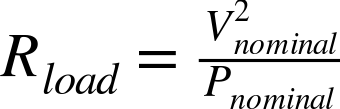

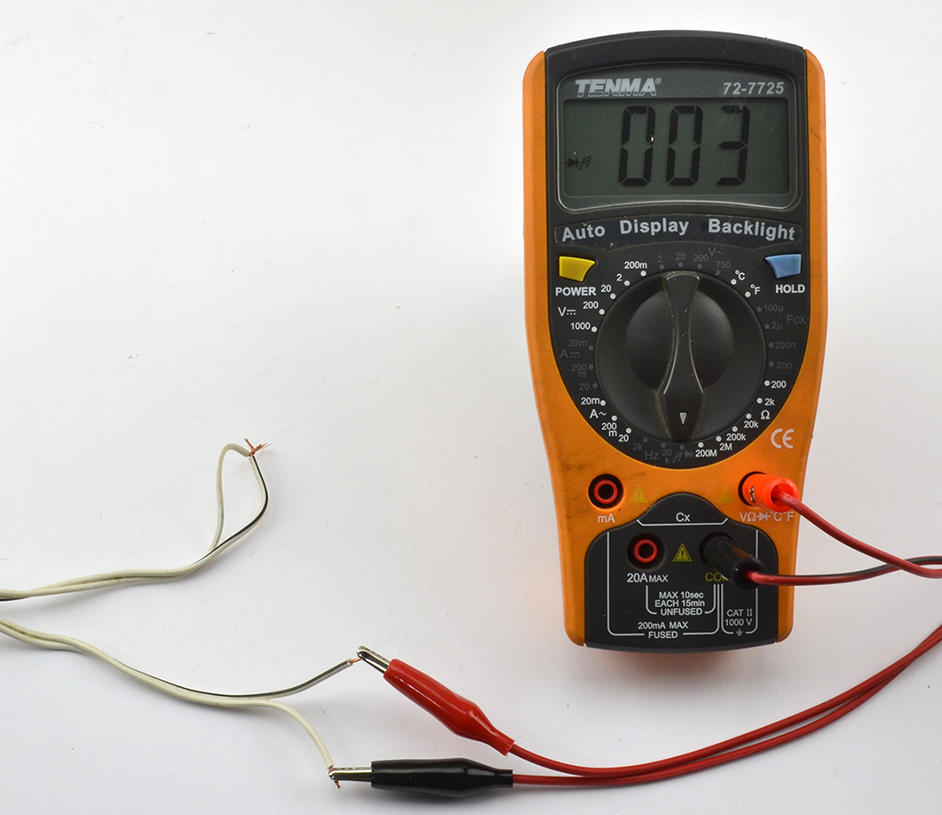

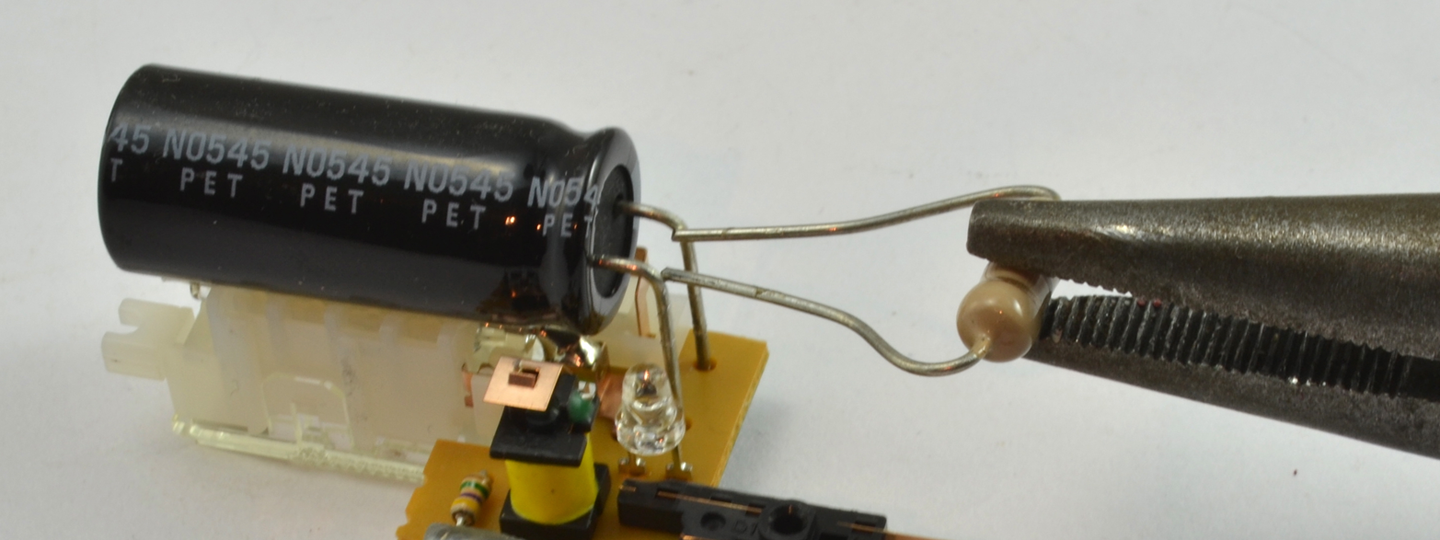

If you know the voltage across the resistor and the resistance of the resistor, then you can combine Ohm’s Law and P=IV and use the formula:

With V=1.5V and R of 100Ω the power is 1.5V x 1.5V / 100Ω = 22.5mW.

For Ohm’s Law see Recipe 1.3.

In all the recipes up to this point, DC is assumed. The voltage is constant and generally what you would expect a battery to supply.

AC is what is supplied by wall outlets, and although it can be reduced to lower voltages (see Recipe 3.9) it is generally of a high (and dangerous) voltage. In the US, this means 110V and in most of the rest of the world 220V or 240V.

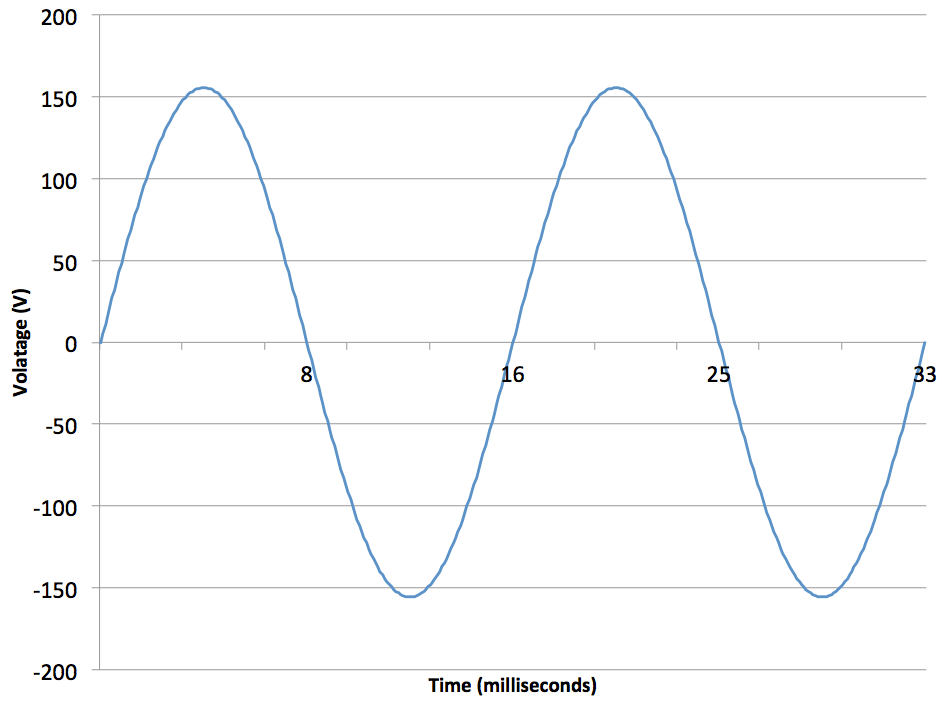

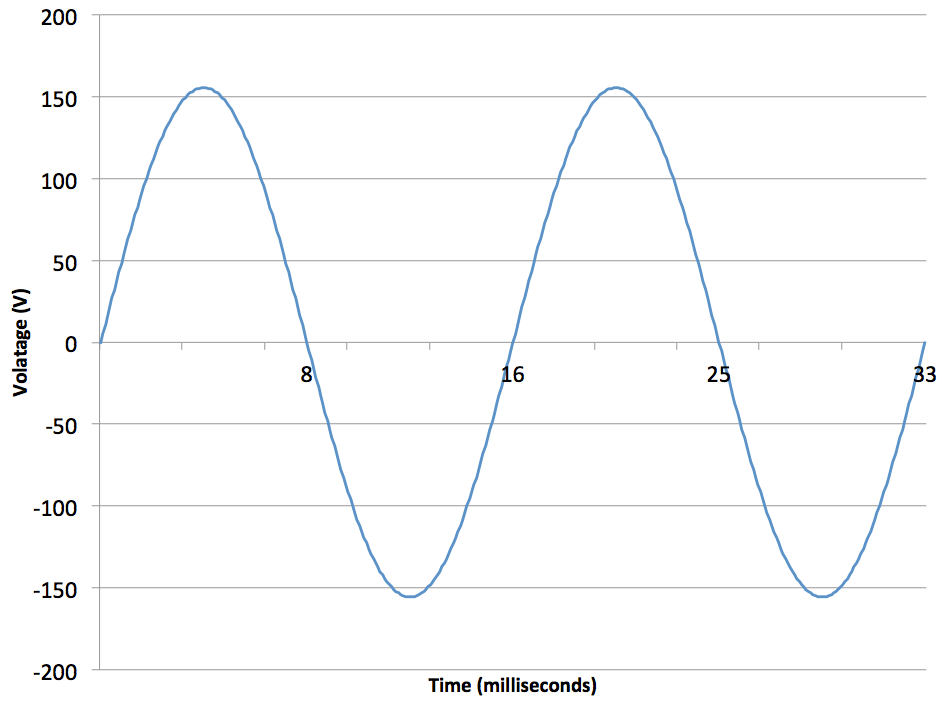

What puts the alternating in alternating current is the fact that the direction of current flow in AC reverses many times per second. Figure 1-7 shows how the voltage varies in a US AC wall outlet.

The first thing to notice is that the voltage follows the shape of a sine wave, gently increasing until it exceeds 150V then heading down past 0V to around –150V and then back up again, taking about 16.6 thousandths of a second (milliseconds, or ms) to complete one full cycle.

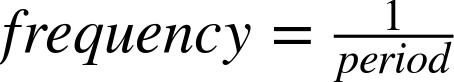

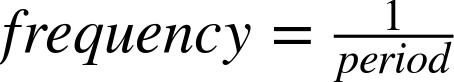

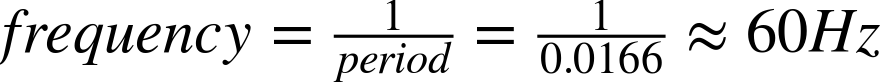

The relationship between the period of AC (time taken for one complete cycle) and the frequency of the AC (number of cycles per second) is:

The unit of frequency is the Hertz (abbreviated as Hz) so you can see that the AC shown in Figure 1-7 has a period of 16.6ms, which is 0.0166 seconds. So you can calculate the frequency as:

You may be wondering why AC from an outlet is described as 110V when it actually manages to swing over a range of over 300V from peak to peak. The answer is that the 110V figure is the equivalent DC voltage that would be capable of providing the same amount of power. This is called the RMS (root mean square) voltage and is the peak voltage divided by the square root of 2 (which is roughly 1.41). So, in the preceding example, the peak voltage of 155V when divided by 1.41 gives a result of roughly 110V RMS.

You will find more information on using AC in Chapter 7.

Resistors are used in almost every electronic circuit, come in a huge variety of shapes and sizes, and are available in a range of values that spans milliohms (thousandths of an ohm) to mega ohms (millions of ohms).

Ohm, the unit of resistance, is usually abbreviated as the Greek letter omega (Ω), although you will sometimes see the letter R used instead. For example, 100Ω and 100R both mean a resistor with a resistance of 100 ohms.

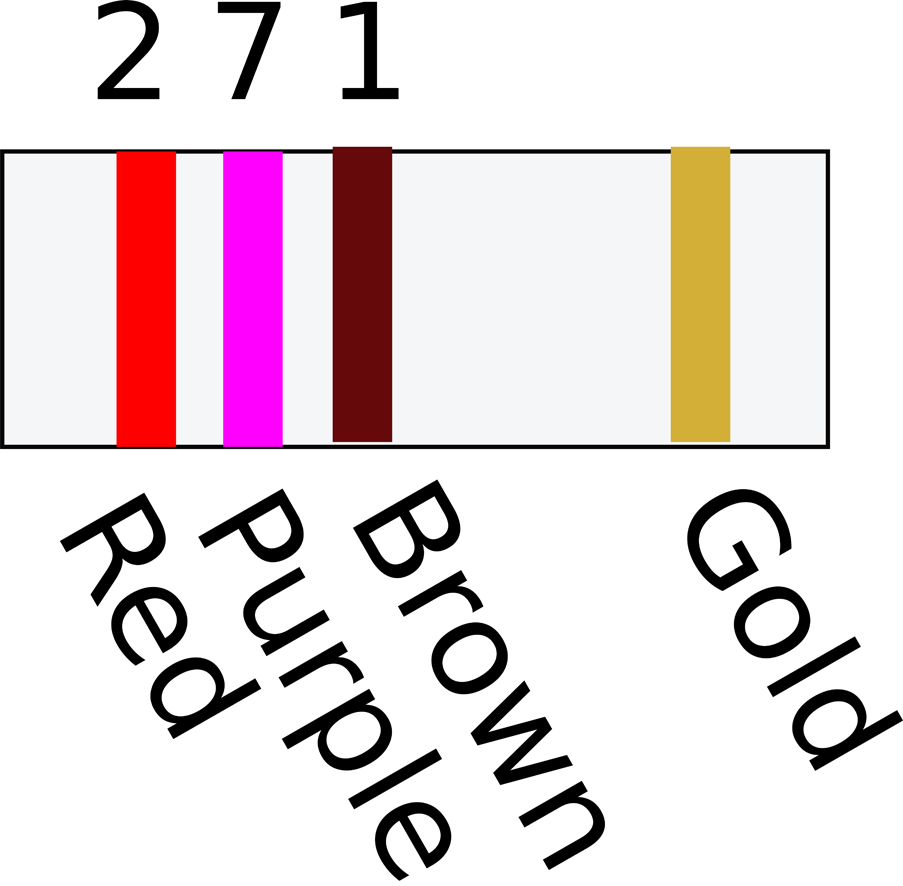

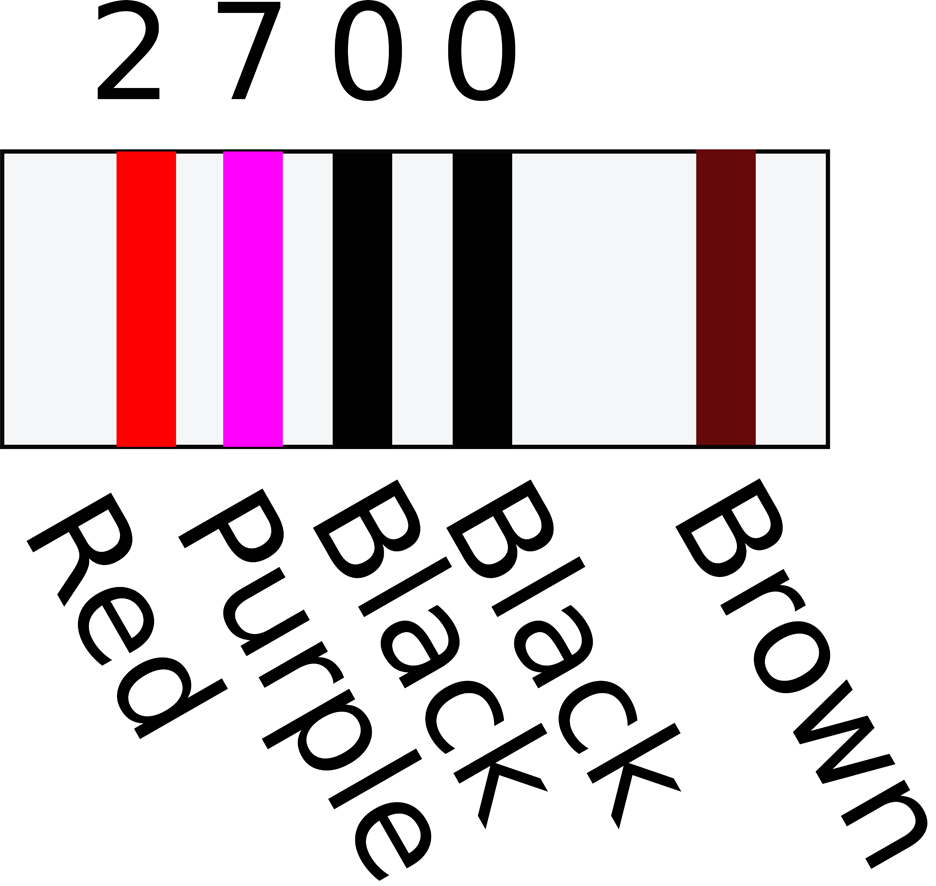

On a through-hole resistor (a resistor with leads) that has colored stripes on it, use the resistor color code.

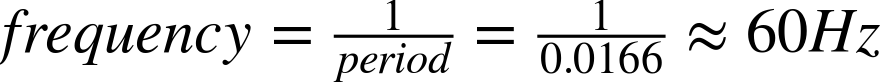

If your resistor has stripes in the same positions as Figure 2-1 then the three stripes together on the left determine the resistor’s value and the single stripe on the right determines the accuracy of the value.

Each color has a value as listed in Table 2-1.

|

Black |

0 |

|

Brown |

1 |

|

Red |

2 |

|

Orange |

3 |

|

Yellow |

4 |

|

Green |

5 |

|

Blue |

6 |

|

Violet |

7 |

|

Gray |

8 |

|

White |

9 |

|

Gold |

1/10 |

|

Silver |

1/100 |

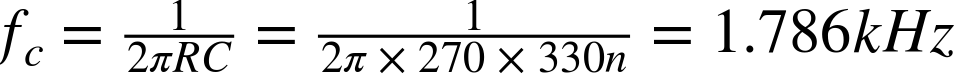

For a three-stripe resistor such as this, the first two stripes determine the basic value (say 27 in Figure 2-1) and the third stripe determines the number of zeros to add to the end. In the example of Figure 2-1, the value of a resistor with stripes red, purple, and brown is 270Ω. I said before that this stripe indicates the number of zeros, but actually, to be more accurate, it is a multiplier. If it has a value of gold, then this means ⅒ of the value indicated by the first two stripes. So brown, black, and gold would indicate a 1Ω resistor.

The stripe on its own specifies the tolerance of the resistor. Silver (rare these days) indicates ±10%, gold ±5%, and brown ±1%.

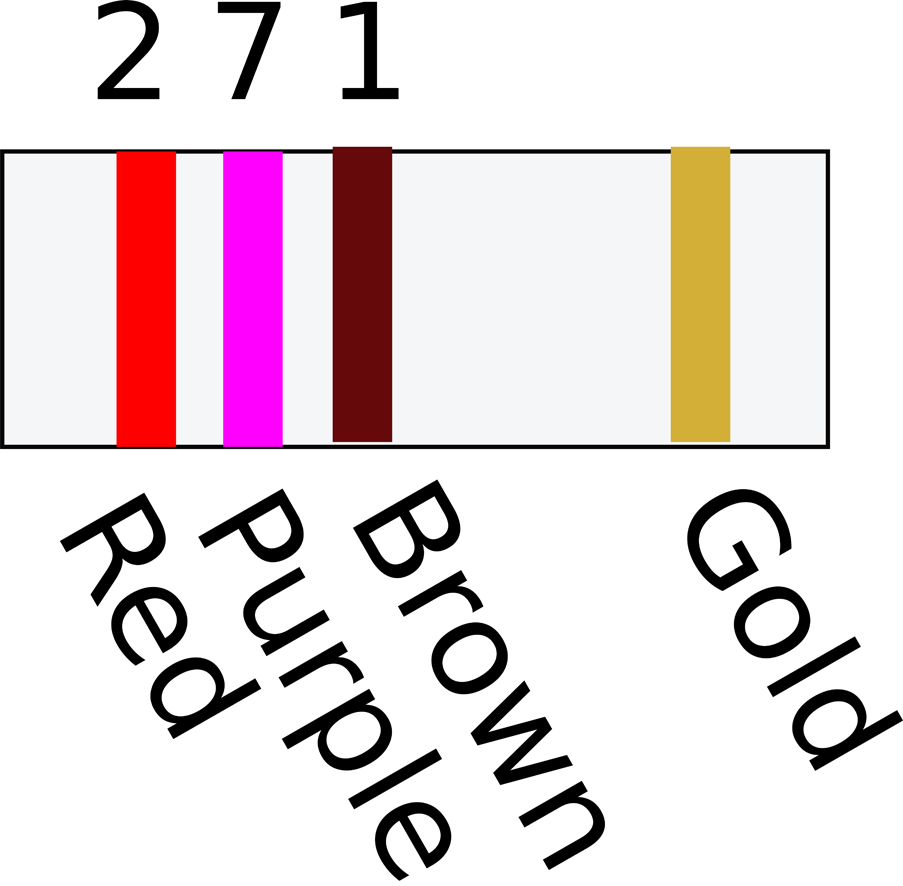

If your resistor has stripes as shown in Figure 2-2 then the value of the resistor is specified with an extra digit of precision. In this case, the first three stripes determine the basic value (in the case of Figure 2-2, 270) and the final digit the number of zeros to add (in this case, 0). This resistor is also 270Ω.

For low-value resistors, gold is used as a multiplier of 0.1 and silver of 0.01. A 1Ω four-stripe resistor would have value stripes of brown, black, black, and silver (100 x 0.01).

Through-hole capacitors also have value labels similar to SMT resistors (see Recipe 3.3).

The ±1% E96 series includes all the base values of the E24 series, but has four times as many values. However, it is very rare to need such precise values of resistor.

If your resistor is to limit current to some other component that might be damaged, perhaps limiting the power to an LED (Recipe 4.4) or into the base of a bipolar transistor (Recipe 5.1), then pick the next largest value of resistor from the E24 series.

For example, if your calculations tell you that the resistor should be a 239Ω resistor, then pick a 240Ω resistor from the E24 series.

In reality, you may decide to limit yourself even further to avoid having to gradually collect every conceivable value of resistor, especially as they are often sold in packs of 100. I generally keep the following resistor values in stock: 10Ω, 100Ω, 270Ω, 470Ω, 1k, 3.3k, 4.7k, 10k, 100k, and 1M.

For full details on all of the resistor series available, see http://www.logwell.com/tech/components/resistor_values.html.

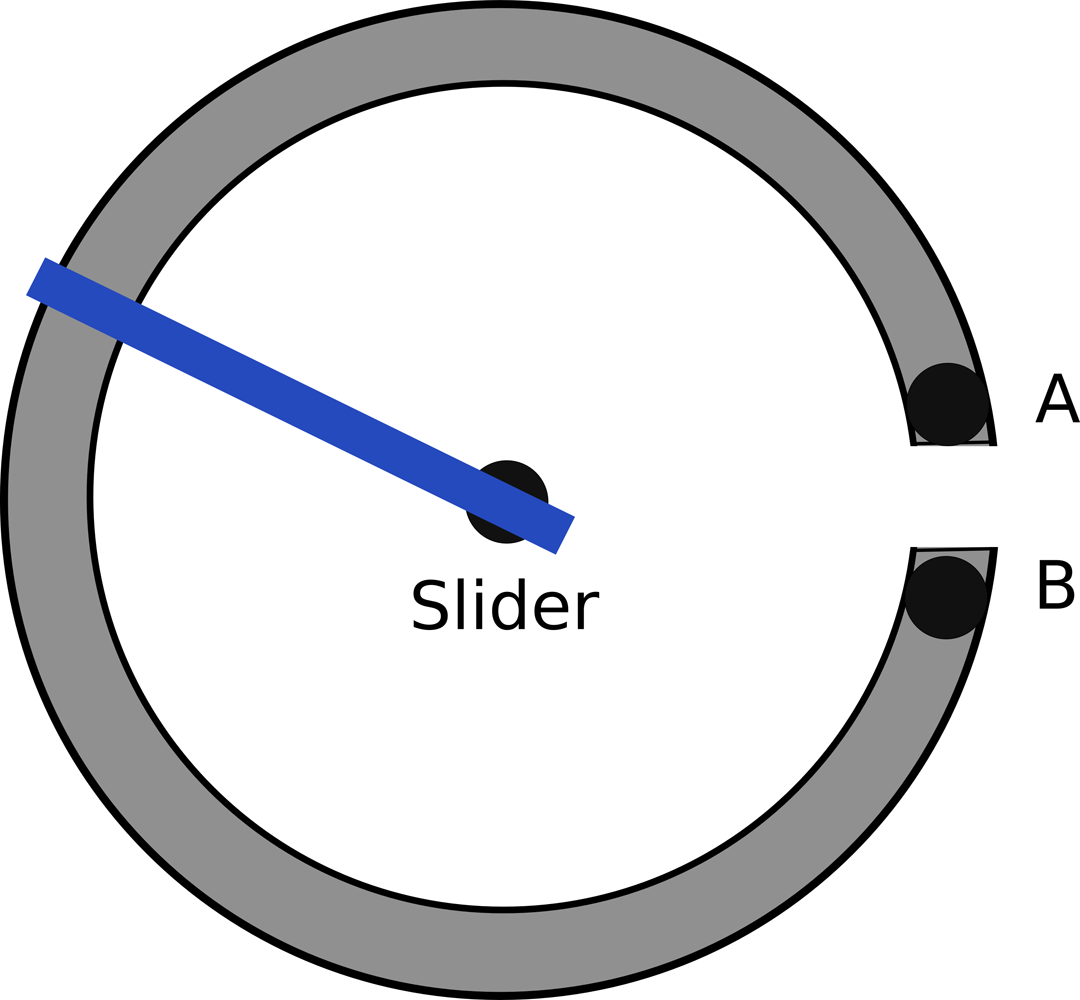

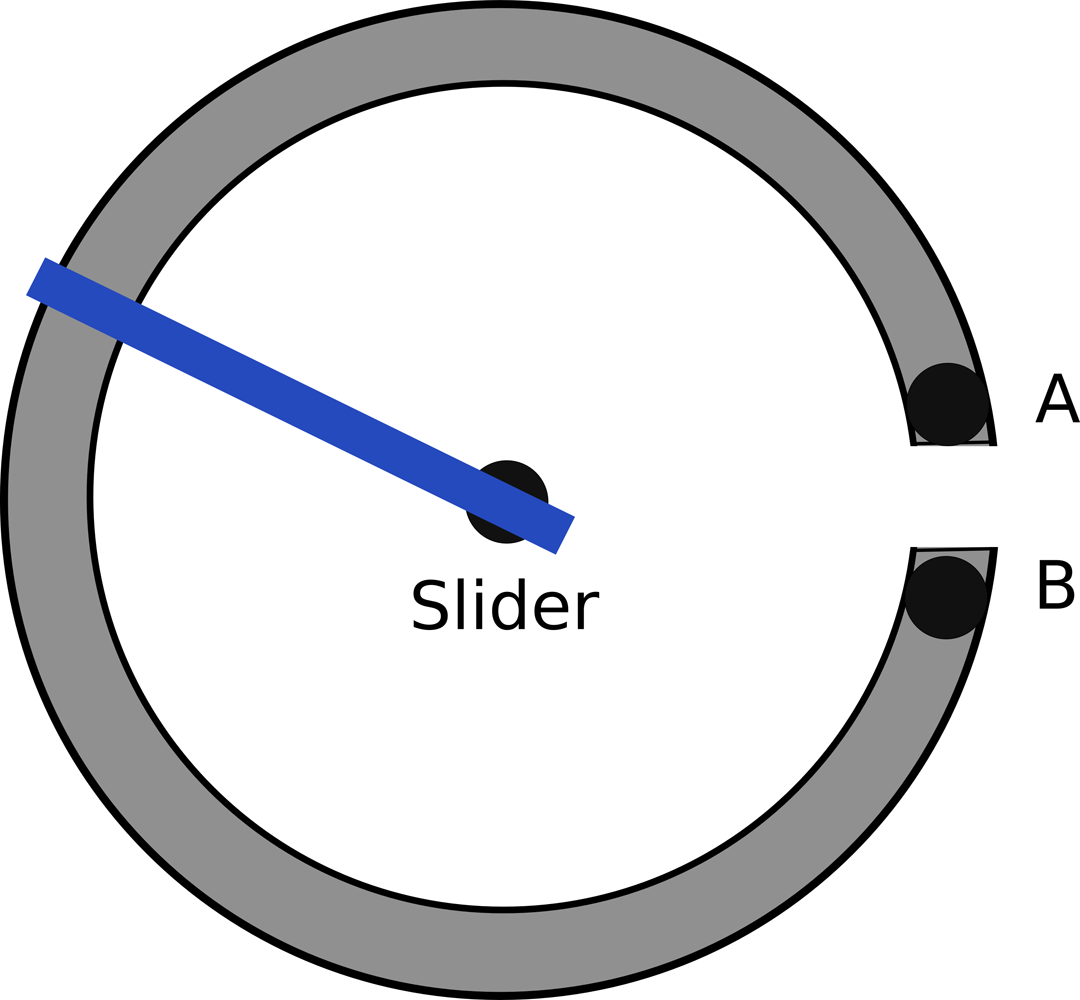

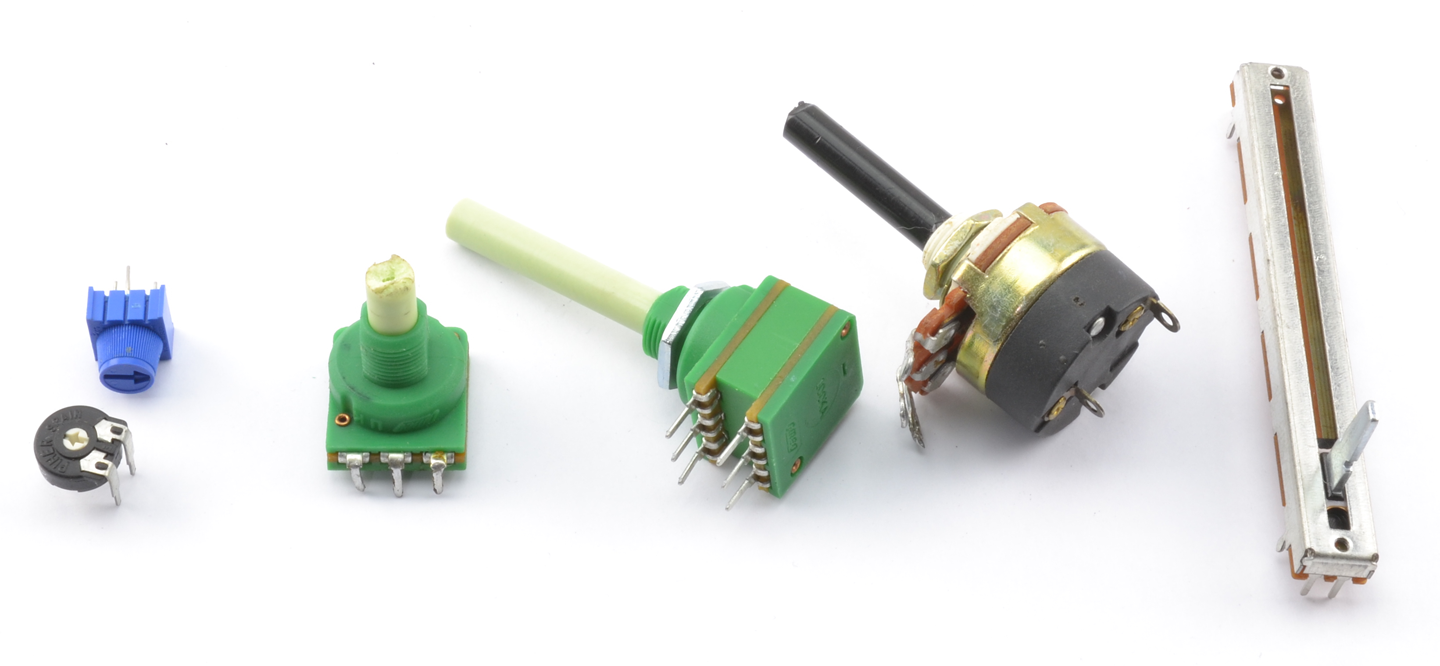

A variable resistor, a.k.a. a pot or potentiometer, is made from a resistive track and a slider that varies its position along the track. By varying the position of the slider you can vary the resistance between the slider and either of the terminals at the ends of the track. The most common pots are rotary like the one shown in Figure 2-3.

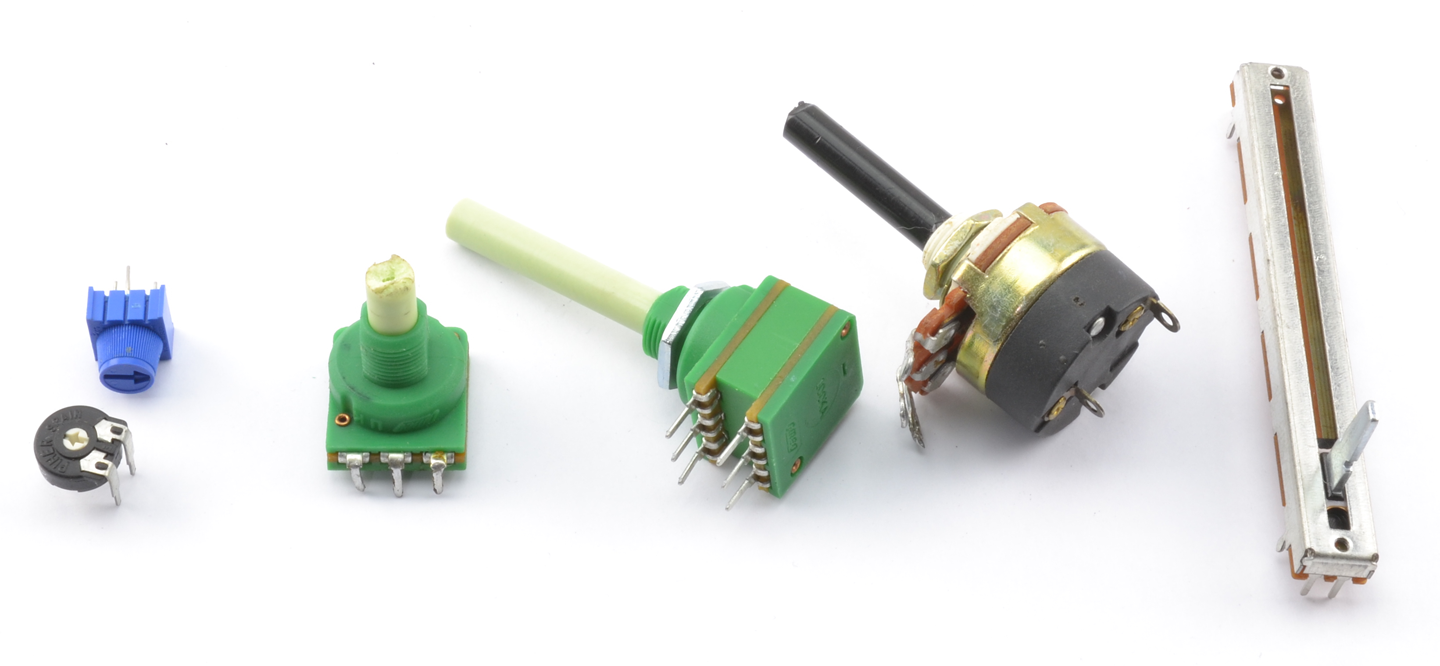

Pots come in a large variety of shapes and sizes. Figure 2-4 shows a selection of pots.

The two pots on the left of Figure 2-4 are called trimmers or trimpots. These devices are designed to be turned using a screwdriver or by twiddling the tiny knob between the thumb and forefinger.

The next pot is a pretty standard device with a threaded barrel that allows the pot to be fixed into a hole. The shaft can be cut to the length required before fixing a knob to it.

There is a dual-gang pot in the middle of Figure 2-4. This is actually two pots with a common shaft and is often employed in stereo volume controls. After that is a similar looking device that combines a pot with an on/off switch. Finally, on the right is a sliding type of pot, the kind that you might find on a mixing desk.

Pots are available with two types of tracks. Linear tracks have a close to linear resistance across the whole range of the pot. So, at the half-way point the resistance will be half of the full range.

Pots with a logarithmic track increase in resistance as a function of the log of the slider position rather than in proportion to the position. This makes them more suitable to volume controls as human perception of loudness is logarithmic. Unless you are making a volume control for an audio amplifier, you probably want a linear pot.

To connect a pot to an Arduino or Raspberry Pi, see Recipe 12.9.

A potentiometer lends itself to being a variable voltage divider (see Recipe 2.6).

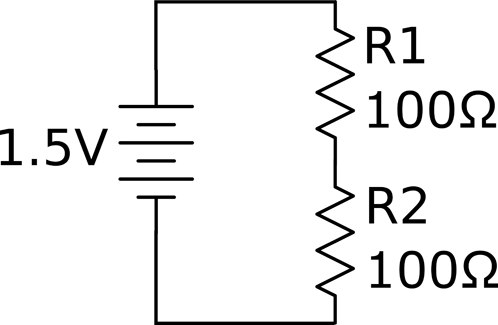

The overall resistance of a number of resistors in series is just the sum of the separate resistances.

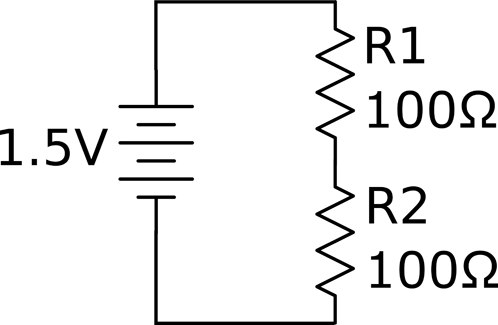

Figure 2-5 shows two resistors in series. The current flows through one resistor and then the second. As a pair, the resistors will be equivalent to a single resistor of 200Ω.

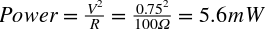

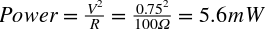

The heating power of each resistor will be  .

.

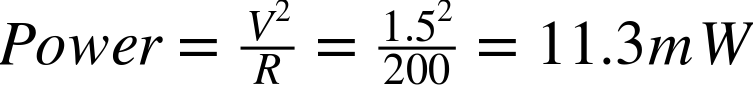

If you used a single resistor of 200Ω then the power would be:

So, by using two resistors, you can double the power.

You may be wondering why you would ever want to use two resistors in series when you could just use one. Power dissipation may be one reason, if you cannot find resistors of sufficient power.

But there are other situations, such as the one shown in Figure 2-6, where you use a variable resistor (pot) with a fixed resistor to make sure that the combination’s resistance does not fall below the value of the fixed resistor.

Resistors in series are often used to form a voltage divider (see Recipe 2.6).

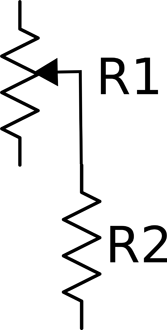

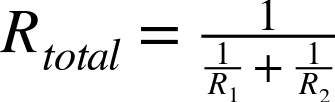

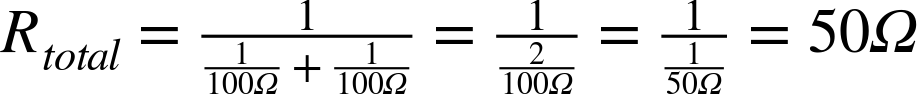

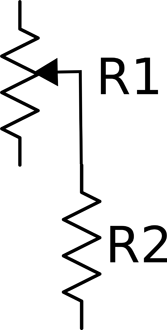

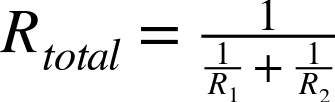

The combined resistance of a number of resistors in parallel is the inverse of the sum of the inverses of the resistors. That is, if there are two resistors R1 and R2 in parallel, then the overall resistance is given by:

In the example shown in Figure 2-7 with two 100Ω resistors in parallel, the arrangement is equivalent to a single resistor of:

Intuitively, this makes perfect sense, because there are now two equally resistive paths through the resistors instead of one as would be the case with a single resistor.

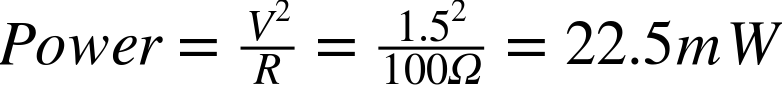

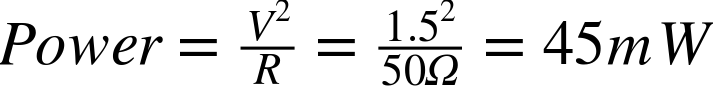

In Figure 2-7 a single 50Ω resistor is equivalent to the two 100Ω resistors in parallel, but what implications does this have for the power ratings of the two resistors?

Intuitively, you would expect the total power dissipation of two 100Ω resistors to be the same as the two 50Ω resistors, but just to be sure let’s do the math.

For each 100Ω resistor, the power will be:

So the total for the two resistors will be 45mW, allowing you to use lower power and more common resistors.

Just as you’d expect, performing the calculation for the single 50Ω resistor you get:

See Recipe 2.4 for resistors in series.

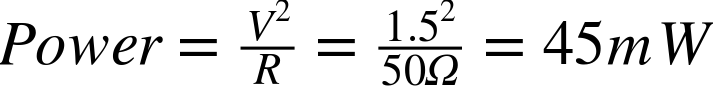

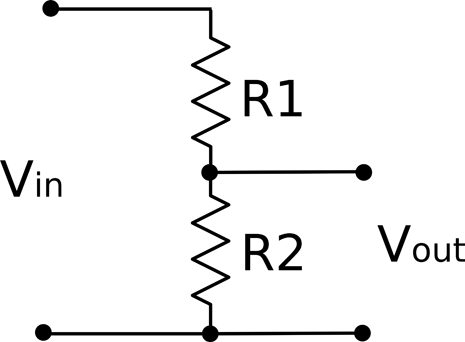

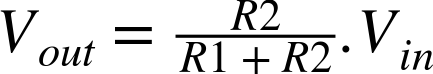

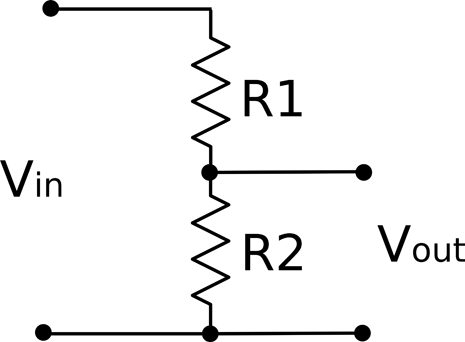

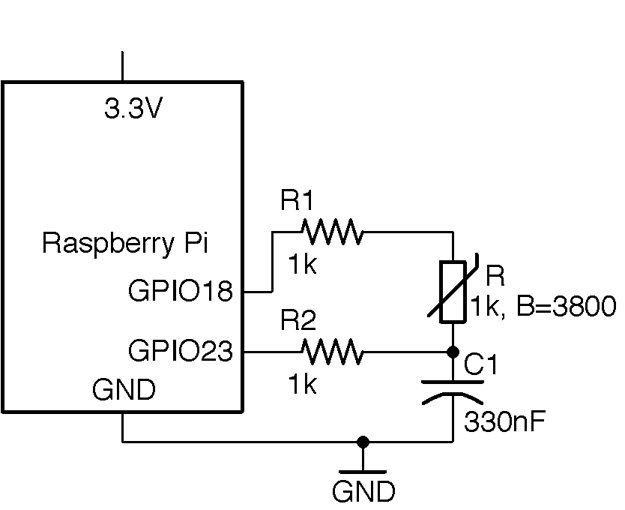

Use two resistors in series as a voltage divider (also called potential divider). The word “potential” indicates the voltage has the potential to do work and make current flow.

Figure 2-8 shows a pair of resistors being used as a voltage divider.

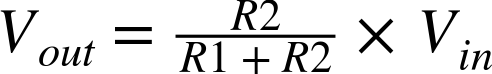

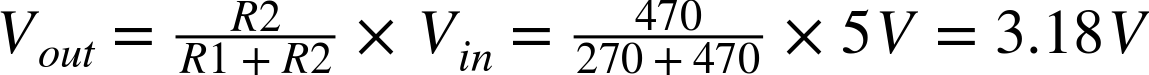

The output voltage (Vout) will be a fraction of the input voltage (Vin) according to the formula:

For example, if R1 is 470Ω, R2 is 270Ω, and Vin is 5V:

Note that if R1 and R2 are equal then the voltage is divided by 2.

A pot naturally forms a potential divider as you can think of it as two resistors in series whose overall resistance adds up to the same value, but the proportion of the resistance of R1 to R2 varies as you turn the knob. This is just how a pot is used in a volume control.

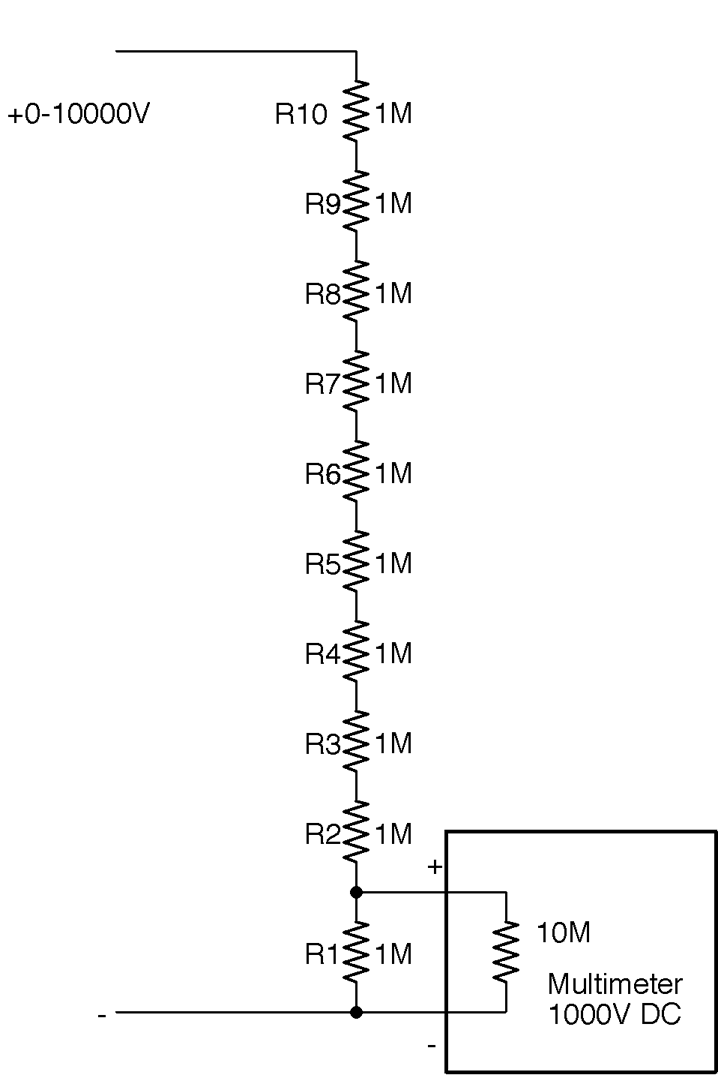

It may be tempting to think of a voltage divider as useful for reducing voltages in power supplies. However, this is not the case, because as soon as you try to use the output of the voltage divider to power something (a load), it is as if another resistor is being put in parallel with R2. This effectively reduces the resistance of the bottom half of the voltage divider and therefore also reduces the output voltage. This will only work if R1 and R2 are much lower than the resistance of the load. This makes them great for reducing signal levels, but of no use for high-power circuits.

See Chapter 7 for various techniques for reducing voltages in power supplies.

For level shifting with a voltage divider, see Recipe 10.17.

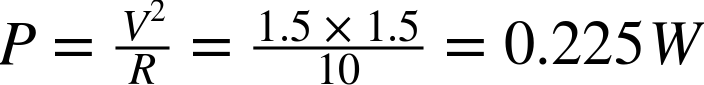

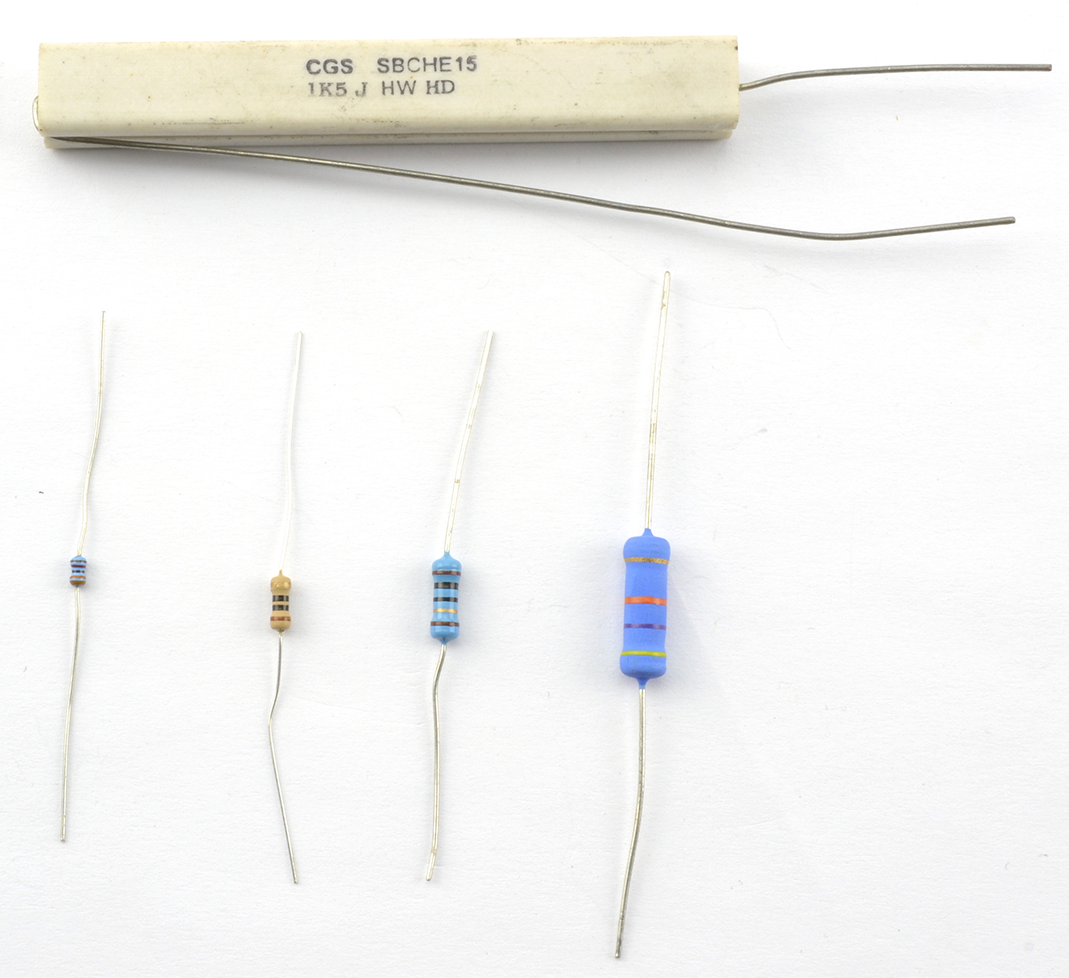

Calculate the power (Recipe 1.6) your resistor will be converting into heat and pick a resistor with a power rating comfortably greater than this value.

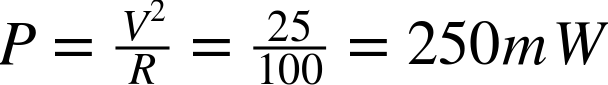

For example, if you have a 10Ω resistor connected directly to the terminals of a 1.5V battery, then the power that the resistor converts to heat can be calculated as:

This means that a standard ¼W resistor will be OK, but you may wish to take the next step up to ½W.

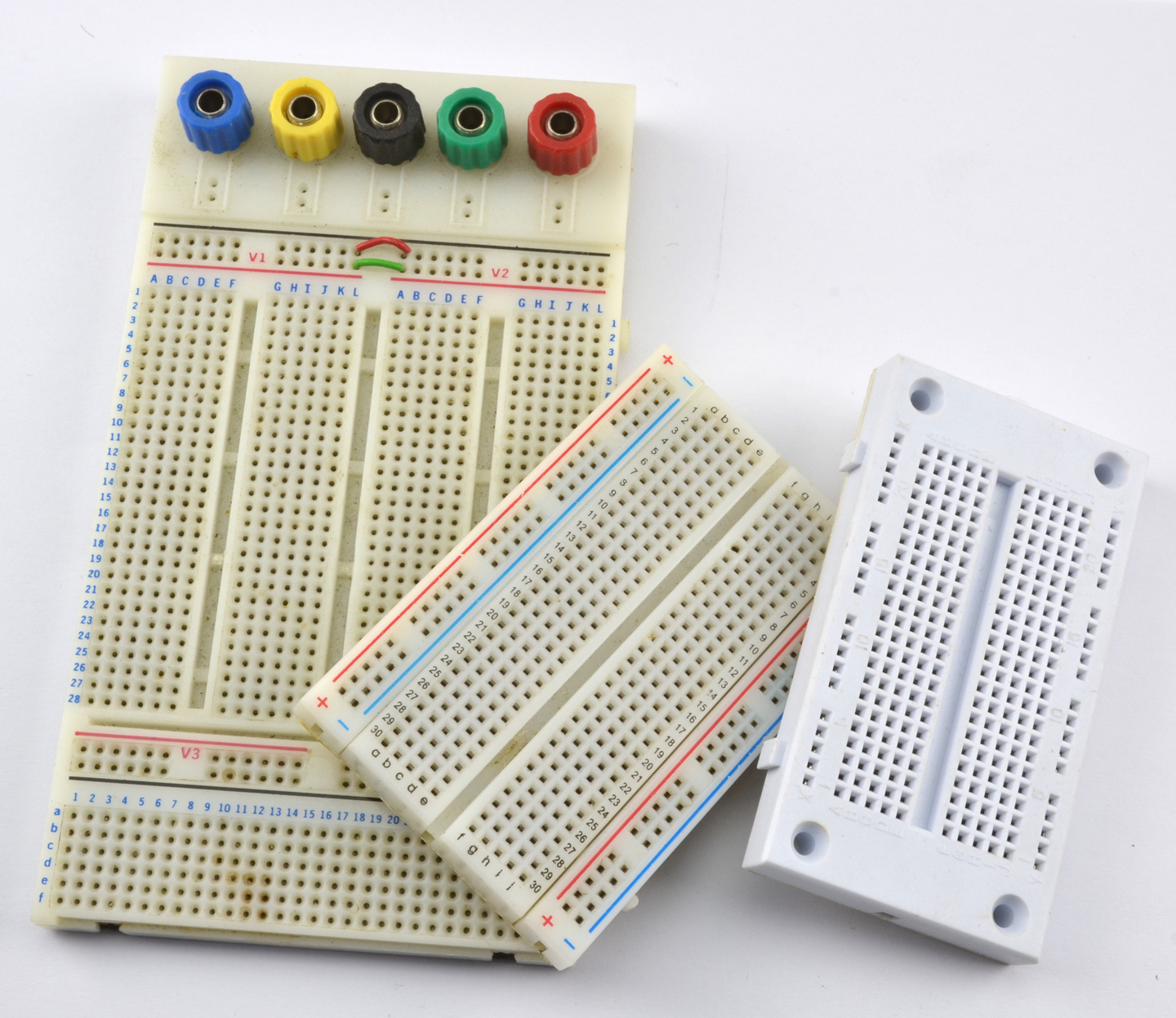

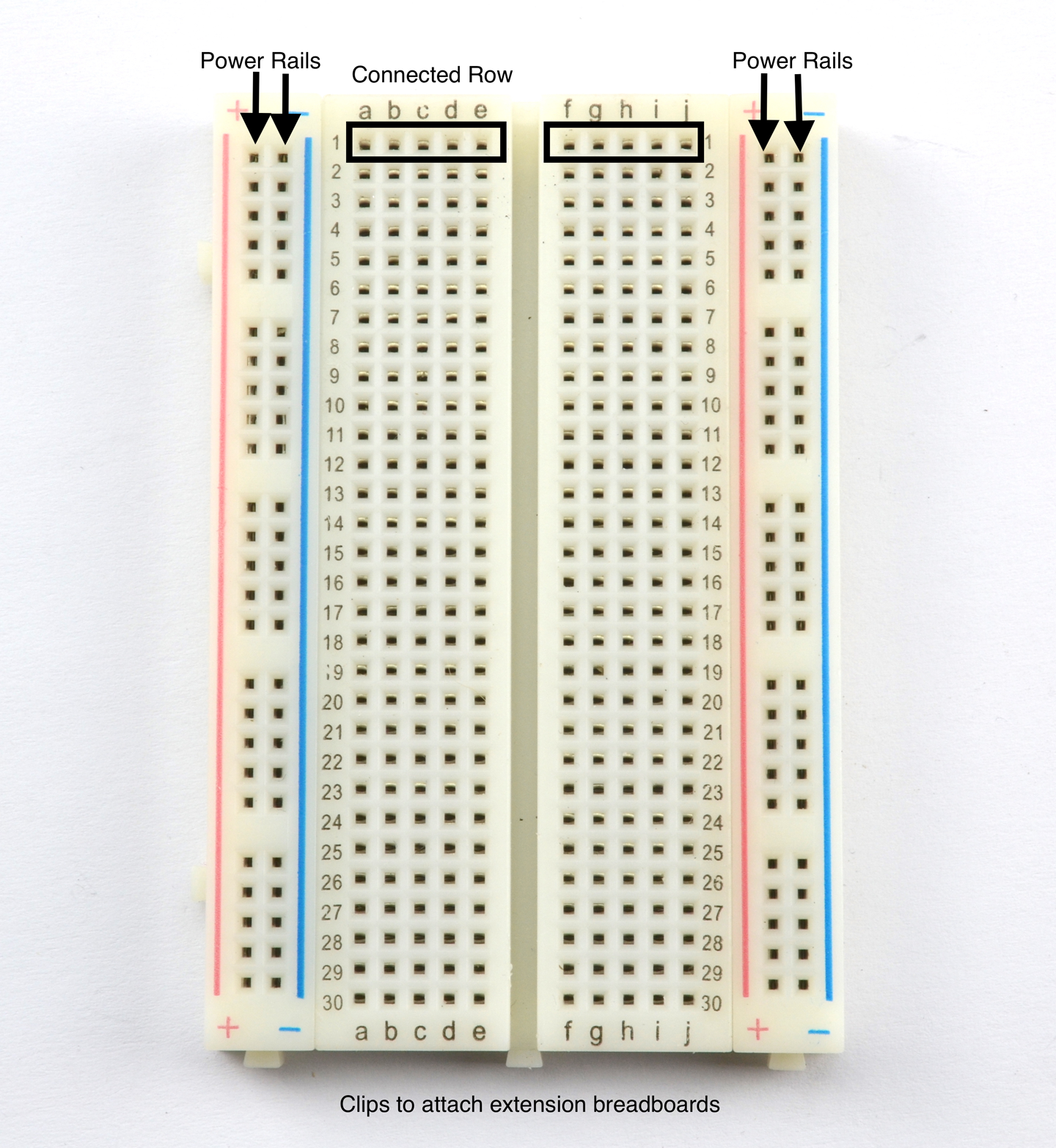

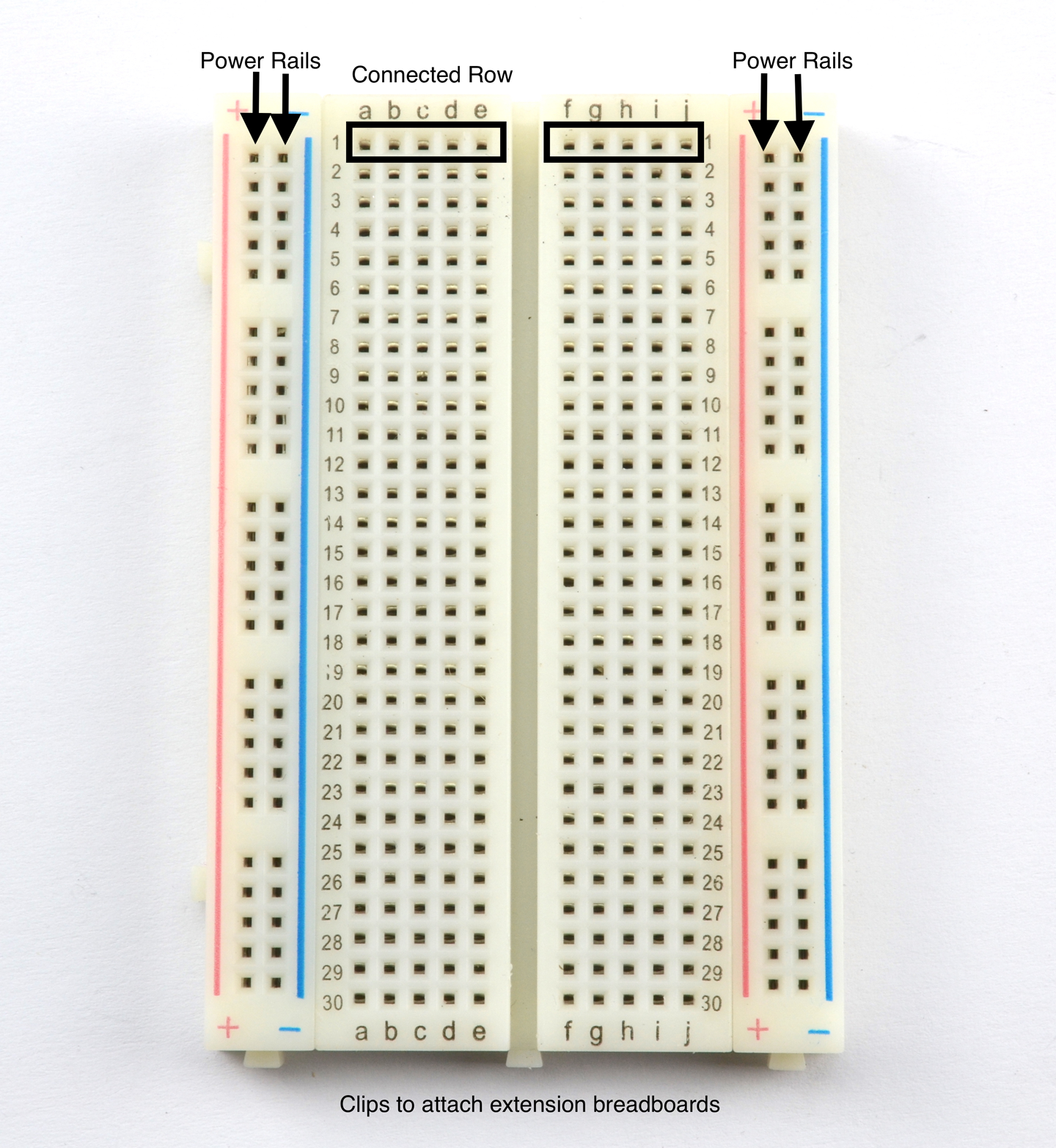

The most common power rating of resistor used by hobbyists is the ¼W (250mW) resistor. These resistors are not so tiny that they are hard to handle or the leads too thin to make good contact in breadboard (Recipe 20.1) yet they are capable of handling enough power for most uses, such as limiting current to LEDs (Recipe 14.1) or used as voltage dividers for low current (Recipe 2.6).

Other common power ratings for through-hole resistors with leads are ½W, 1W, 2W, 5W, 10W, and even higher power resistors.

Figure 2-9 shows a selection of resistors of different power ratings.

When it comes to the tiny surface-mount “chip resistors” that are surface mounted onto circuit boards, power ratings start much lower.

To understand power, see Recipe 1.6.

Use a photoresistor.

A photoresistor (Figure 2-10) is a resistor in a clear plastic package whose resistance varies depending on the amount of light falling on it. The more brightly the photoresistor is illuminated, the lower the resistance.

A typical photoresistor might have a resistance in direct sunlight of 1kΩ increasing to several MΩ in total darkness.

Photoresistors are often used in a voltage-divider arrangement (Recipe 2.6) with a fixed-value resistor to convert the resistance of the photoresistor into a voltage that can then be used with a microcontroller (Recipe 12.6) or comparator (Recipe 17.10).

You will find more details on using a photoresistor in Recipe 12.6.

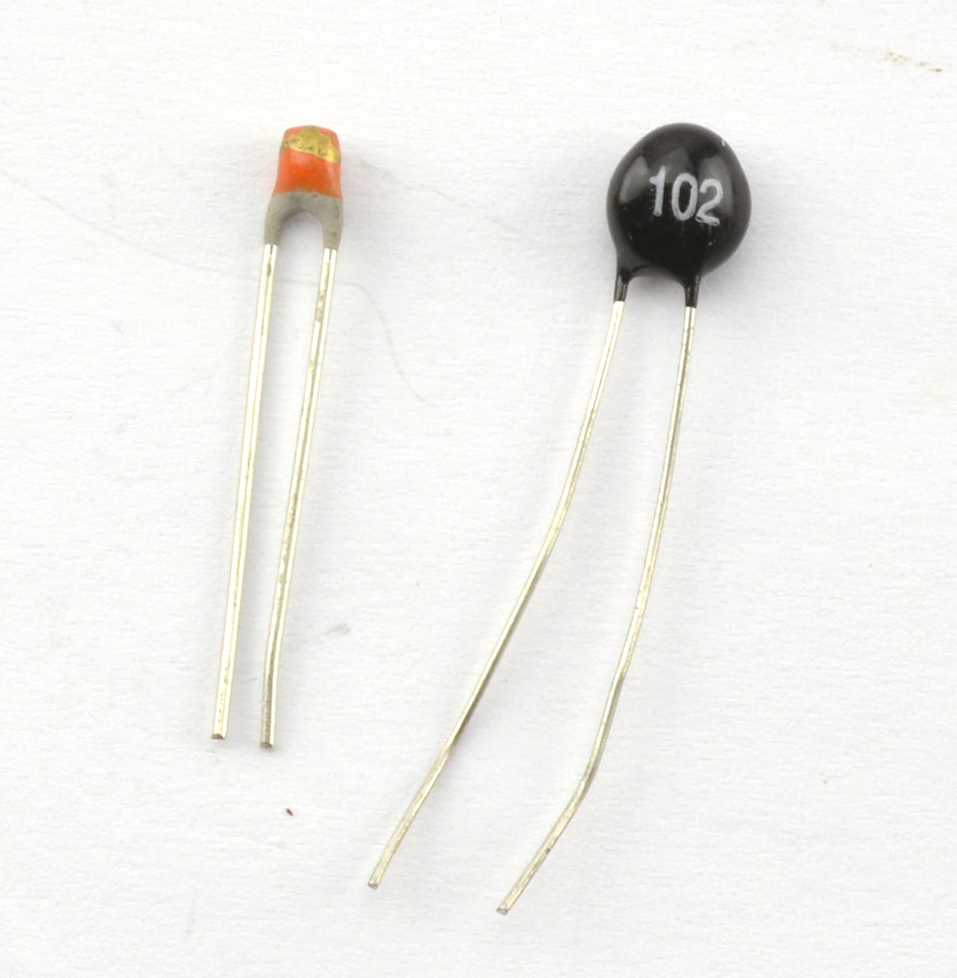

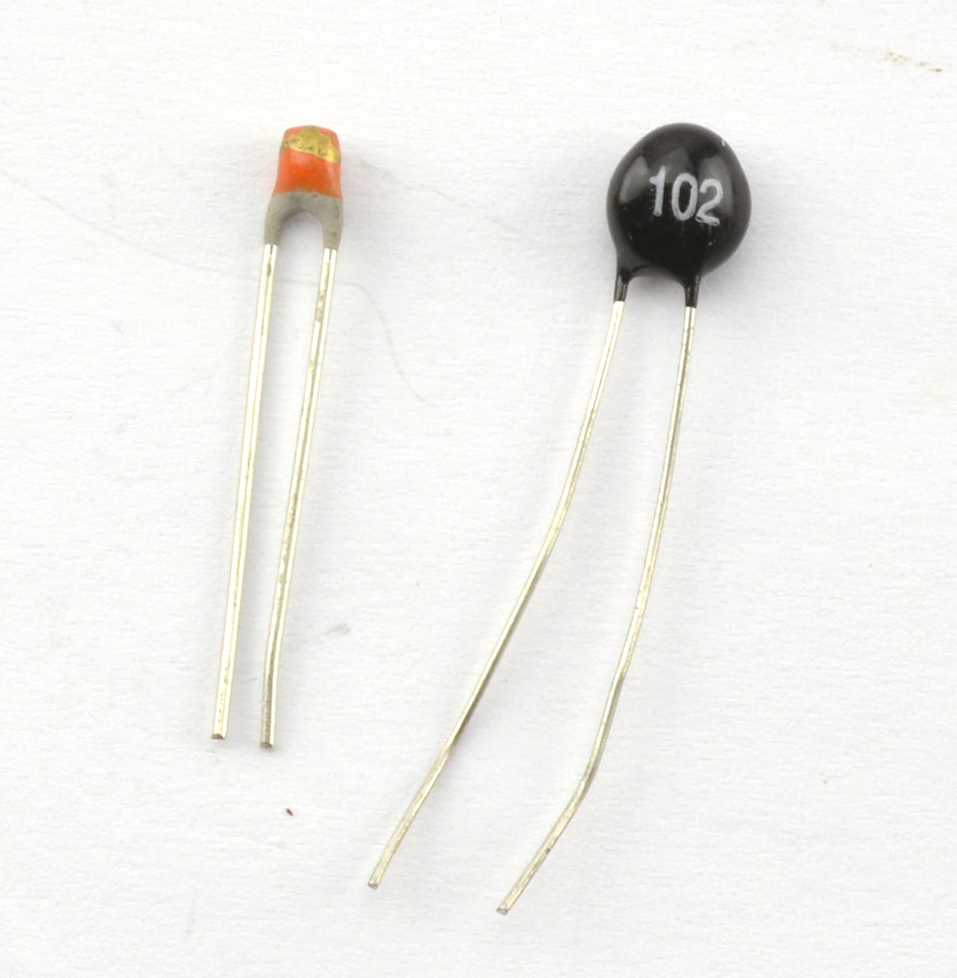

One method is to use a thermistor. Other ways can be found in Recipe 12.10 and Recipe 12.11.

All resistors are slightly sensitive to changes in temperature. However, thermistors (Figure 2-11) are resistors whose resistance is very sensitive to changes in temperature. As with photoresistors (Recipe 2.8), they are often used in a voltage divider (Recipe 2.6) to convert the resistance to a voltage reading that is more convenient.

There are two types of thermistors. NTC (negative temperature coefficient) thermistors are the more common type and their resistance decreases as the temperature increases. PTC (positive temperature coefficient) thermistors have a resistance that increases as the temperature increases.

In addition to being used to measure temperature (see Recipe 12.7) PTC thermistors are also used to limit current. As the current through the thermistor increases, the resistor heats up and thus its resistance increases, reducing the current.

For practical circuits that use a thermistor to measure temperature, see Recipe 12.7 and Recipe 12.8.

Wires all have resistance. A thick copper wire will have a much lower resistance than the same length of a much thinner wire. As someone once said, “the great thing about standards are that there are always lots to choose from.” Nowhere is this more true than for wire thicknesses or gauges. One of the most common standards is AWG (American Wire Gauge) mostly used in the US, and the SWG (Standard Wire Gauge) mostly used in the UK and most logically just the diameter of the wire in mm.

Nearly all wiring used in electronics is made of copper. If you strip the insulation off a wire and it looks silver-colored, then it’s probably still copper, but copper that has been “tinned” to stop it from oxidizing and make it easier to solder.

Table 2-2 shows some commonly used wire gauges along with their resistances in Ω per foot and meter for copper wiring.

| AWG | Diameter (mm) | mΩ/m | mΩ/foot | Max. Current (A) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.255 | 339 | 103 | 0.14 | |

| 28 | 0.376 | 213 | 64.9 | 0.27 | |

| 24 | 0.559 | 84.2 | 25.7 | 0.58 | Solid-core hookup wire |

| 19 | 0.95 | 26.4 | 8.05 | 1.8 | General-purpose multicore wire |

| 15 | 1.8 | 10.4 | 3.18 | 4.7 | Thick multicore wire |

The larger the AWG number the thicker the wire. Wires thinner than 24AWG are most likely to be thin enameled wire designed for winding transformers and indictors, like the wire shown in Figure 2-12.

Solid-core wire is made of a single strand of copper insulated in plastic (Figure 2-13). It is useful with solderless breadboards (Recipe 20.1) but should not be used in situations where it is likely to be flexed as it will break through metal fatigue if bent back and forth. I always have this wire in at least three colors so that I can use black for negative, red for positive, and other colors for nonpower connections.

For general-purpose wire where some movement is likely, use multicore wire made up of a number of strands of wire twisted about each other and encased in plastic insulation. Again, it’s useful to have a selection of colors.

The currents listed in Table 2-2 are only suggestions. The actual current that each gauge of wire can carry without getting too hot depends on many factors, including how well ventilated the project’s case is and whether the wires are all grouped together with a whole load of other wires all getting warm. So treat Table 2-2 as a guide.

When you buy wire, the maximum temperature of the insulation will usually be specified. This is not just because of internal heating of the wire but also for situations where the insulation is to be used in hot environments such as ovens or furnaces.

If you are looking for wires to carry high voltages then you will need a good insulation layer. Again, wires will normally have a breakdown voltage specified for the insulation.

For a table comparing wire gauges, see http://bit.ly/2lOyPIh.

For the current-handling capabilities of wire by gauge, see http://bit.ly/2mbgZS8.

When it comes to digital electronics, capacitors are almost a matter of insurance, providing short-term stores of charge that improve the reliability of circuits. As such their use is often simply a matter of following the recommendations in the IC’s datasheet without the need to do any math.

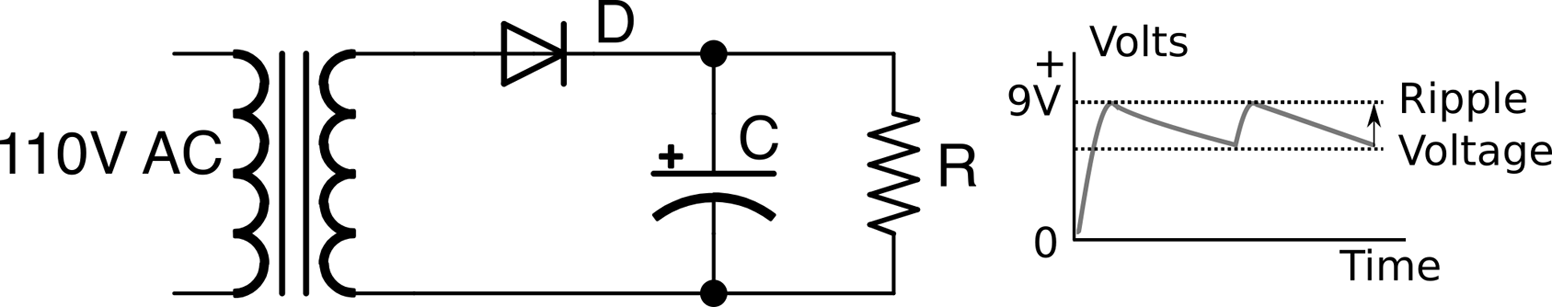

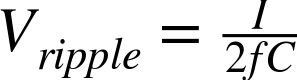

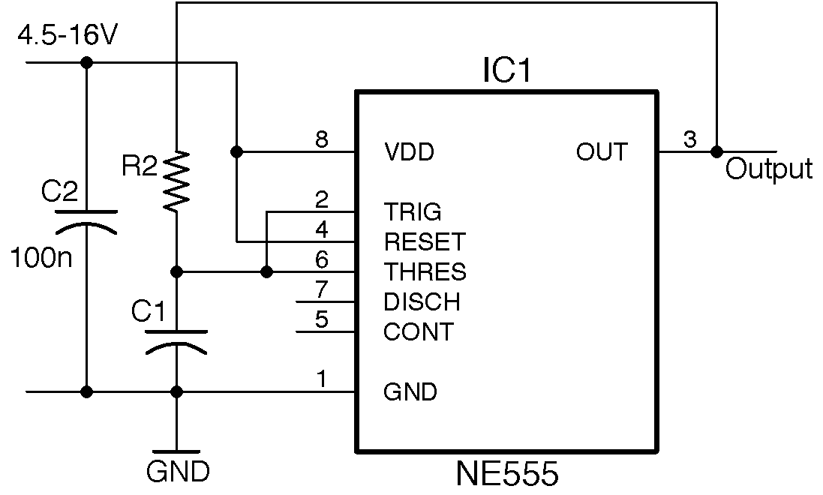

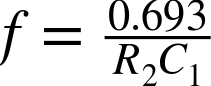

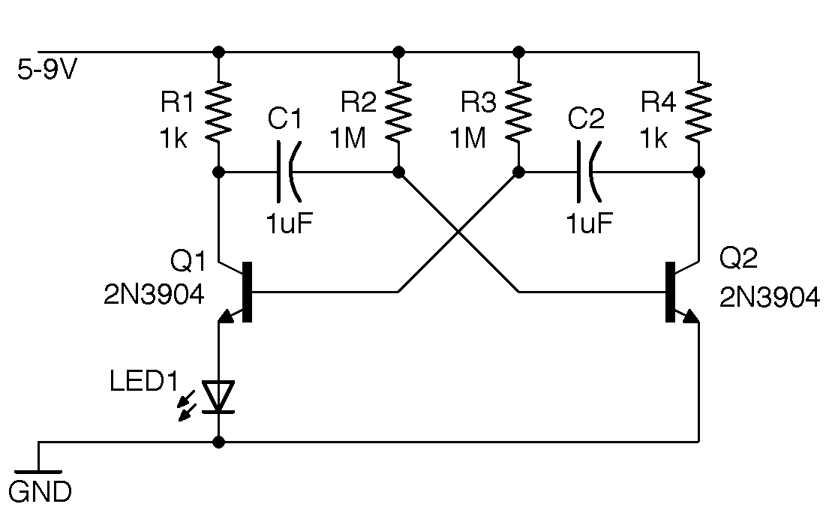

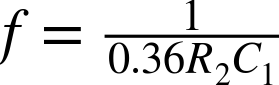

However, when it comes to analog electronics the use of capacitors becomes much more varied. Their ability to store small amounts of charge for a short period of time can be used to set the frequency of oscillators (see Recipe 16.5). They can be used to smooth the ripples for a power supply (see Recipe 7.2) or to couple two audio circuits without transferring the DC part of the signal (see Recipe 17.9).

In fact, capacitors will be used throughout this book in all sorts of ways, so it’s important to understand how they work, how to select the right capacitor, and how to use it.

Inductors are not as common as capacitors, but they are widely used in certain roles, particularly in power supplies (see Chapter 7).

Use a capacitor.

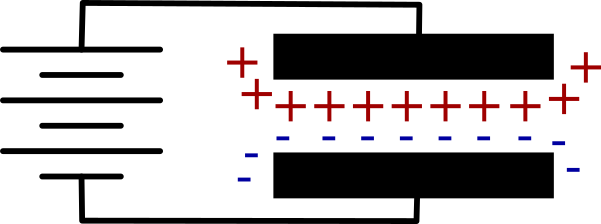

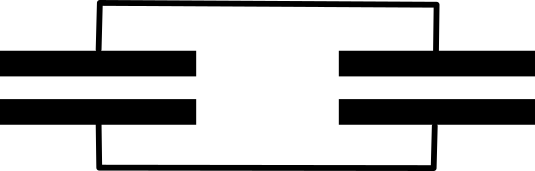

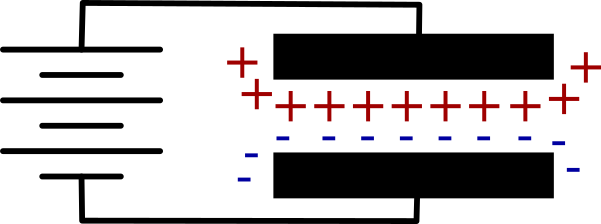

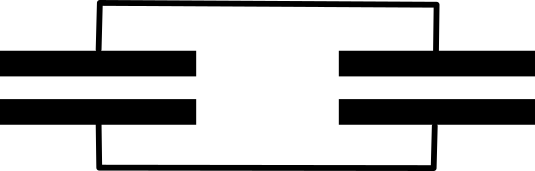

In construction, capacitors are just two conductive surfaces separated by an insulating layer (Figure 3-1).

In fact, the insulating layer between the conductive surfaces of the capacitor can just be air, although a capacitor using an air gap will be of very low value. In fact, the value of the capacitor depends on the area of the conducting plates, how close they are together, and how good an insulator separates them. So the greater the area of the plates and the smaller the distance between them the greater the capacitance (the more charge it can store).

Individual electrons do not flow through a capacitor, but those on one side of the capacitor influence those on the other. If you apply a voltage source like a battery to a capacitor, then the plate of the capacitor connected to the positive supply of the battery will accumulate positive charge and the electric field this generates will create a negative charge of equal magnitude on the opposite plate.

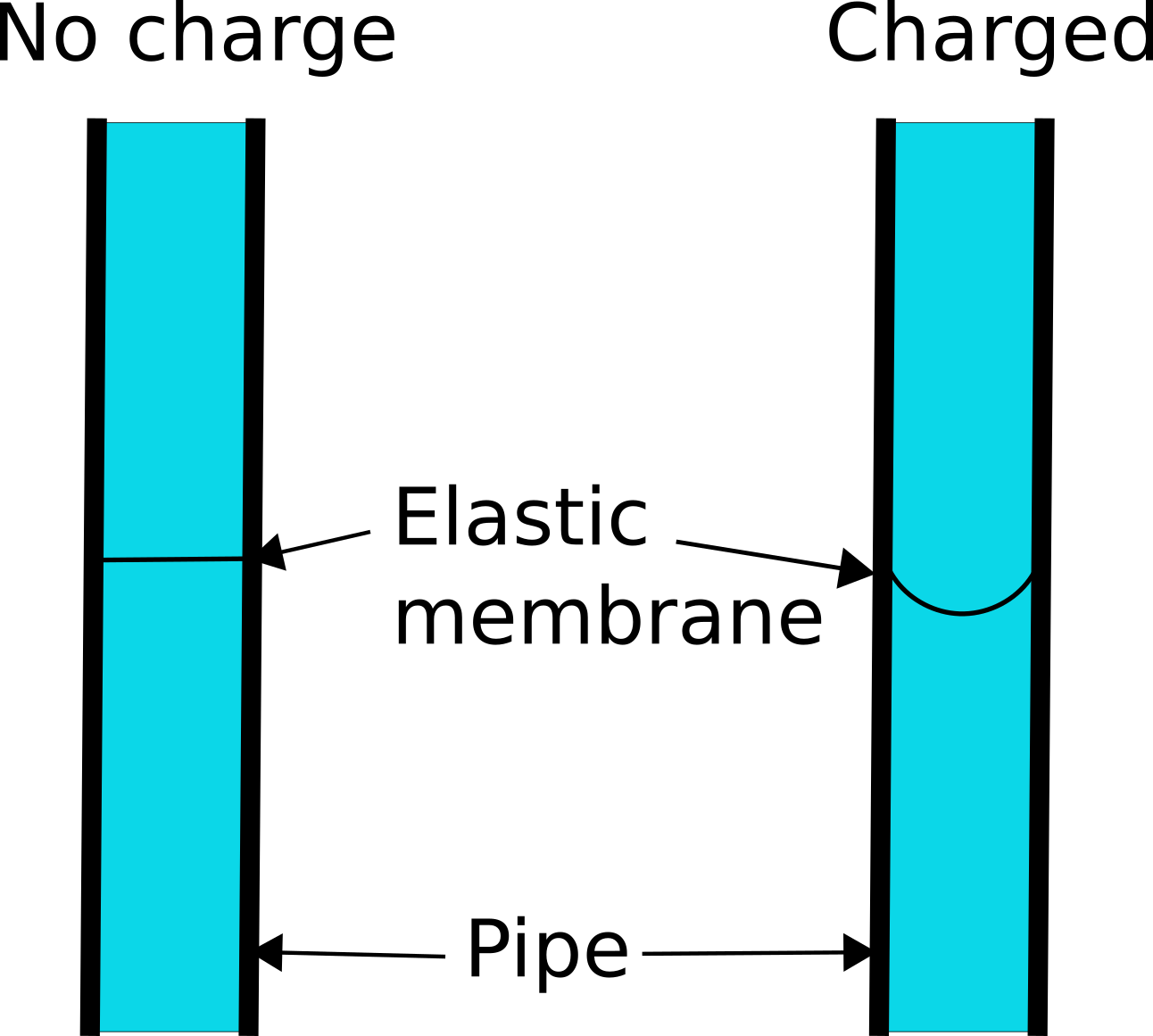

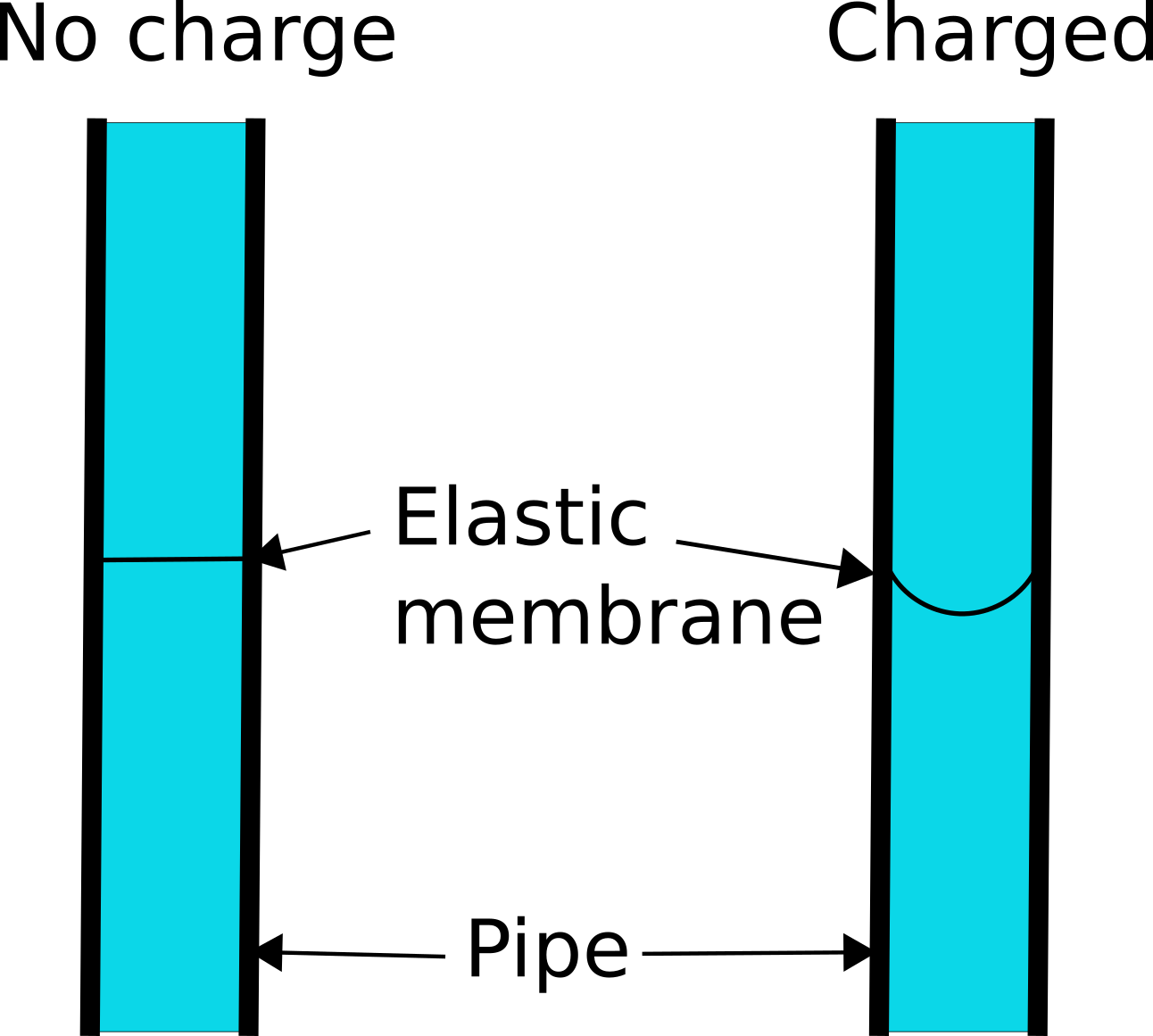

In water terms, you can think of a capacitor as an elastic membrane in a pipe (Figure 3-2) that does not allow water to pass all the way through the pipe, but will stretch, allowing the capacitor to be charged. If the capacitor is stretched too far then the elastic membrane will rupture. This is why exceeding the maximum voltage of a capacitor is likely to destroy it.

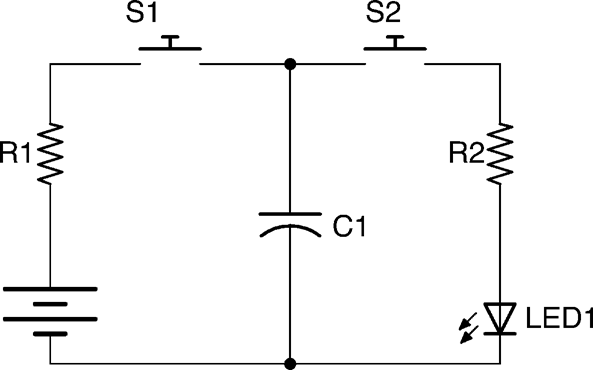

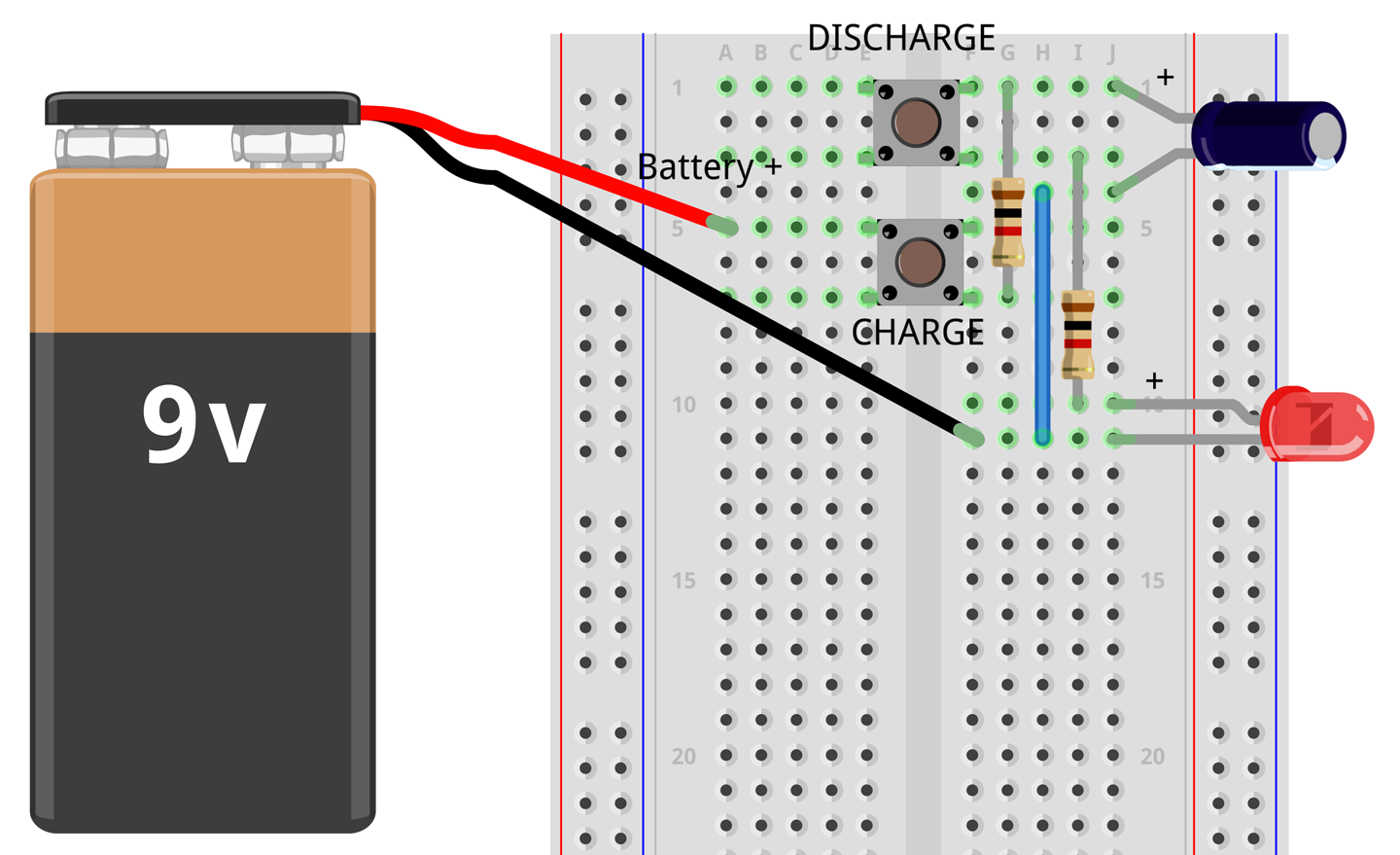

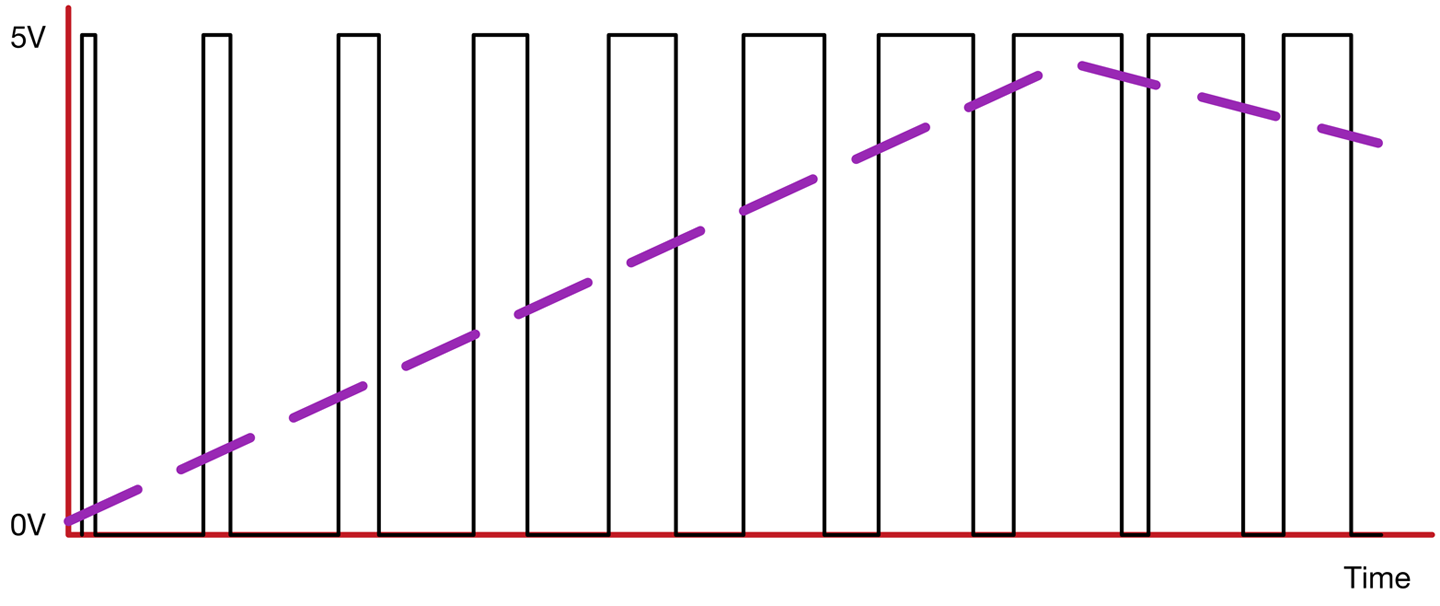

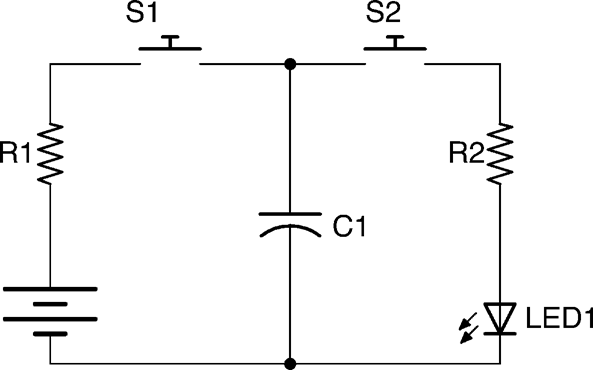

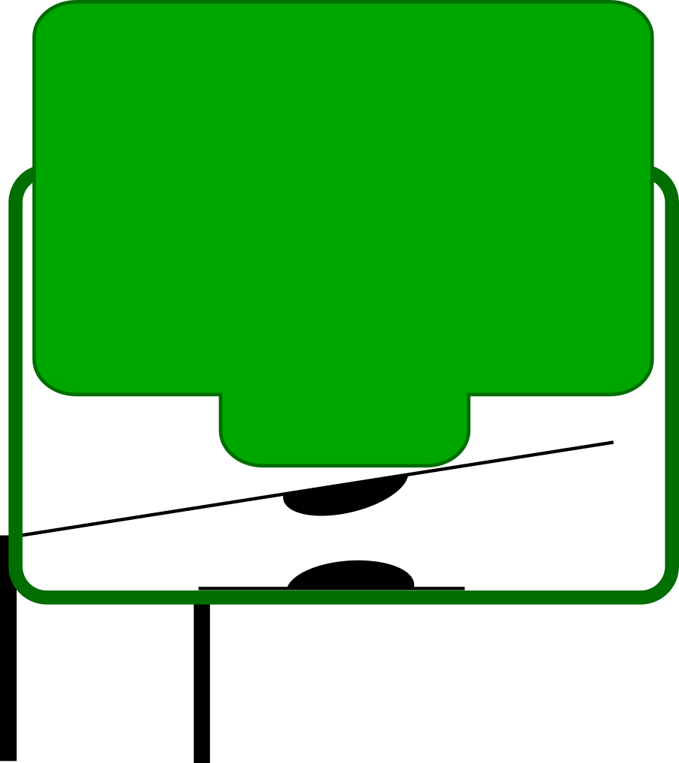

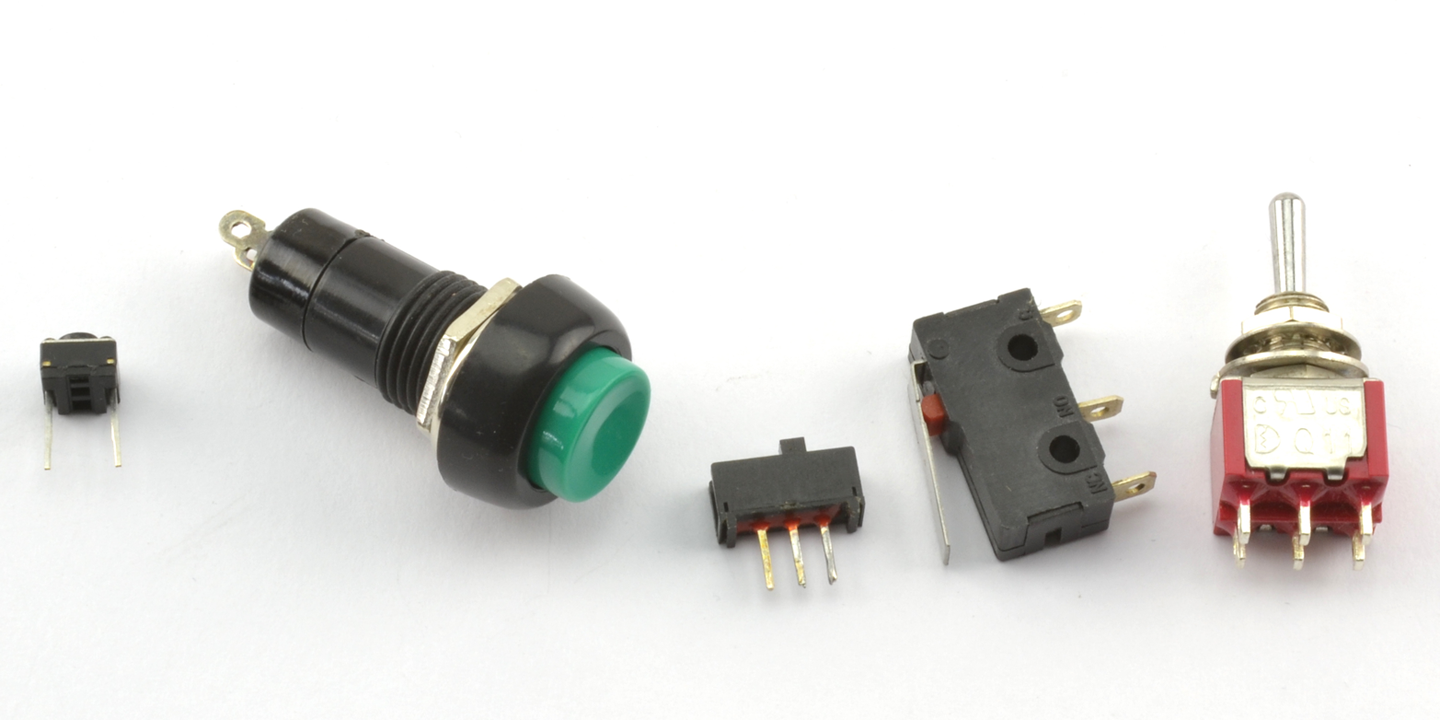

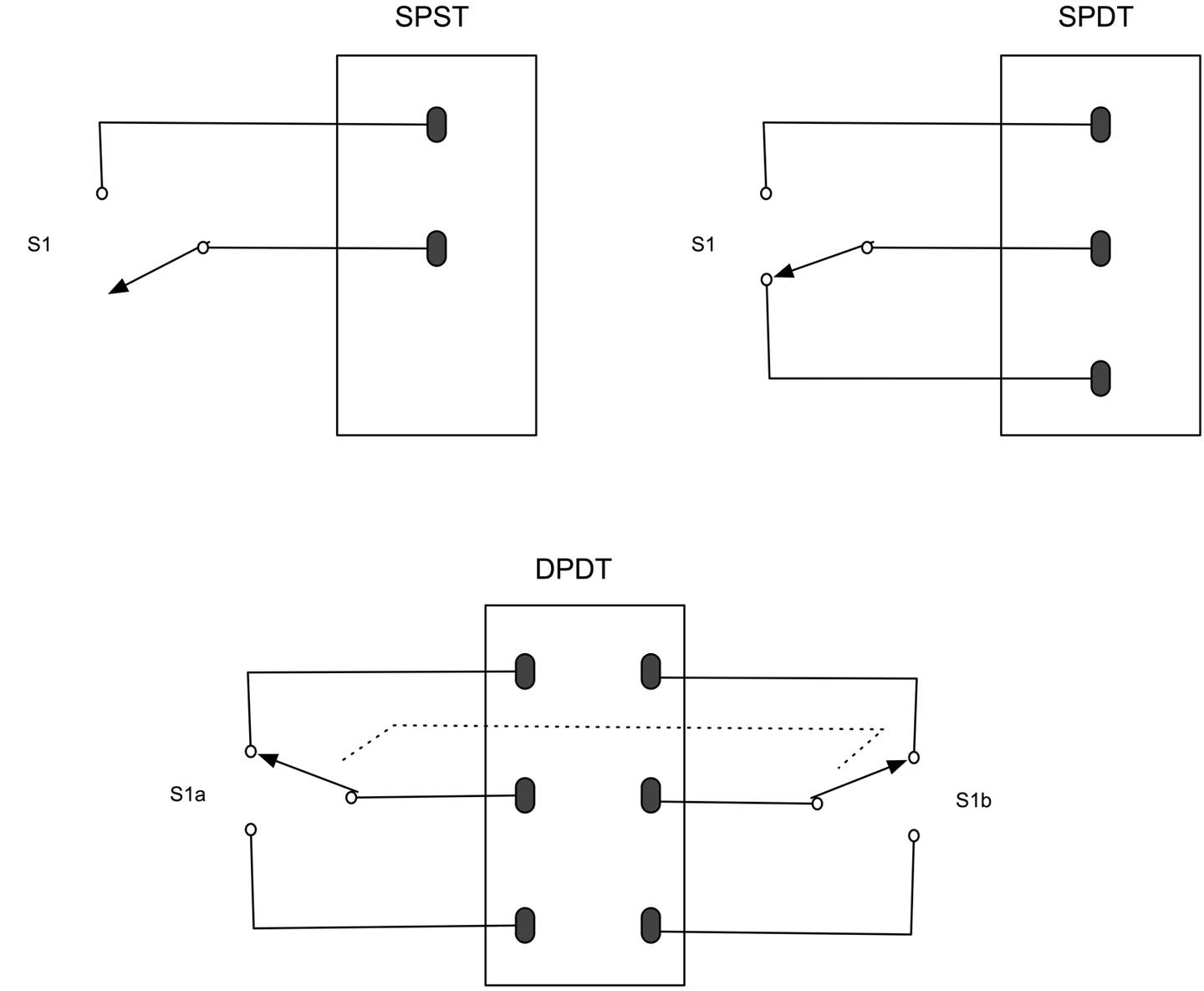

When you apply a voltage across a capacitor it will almost instantly charge to that voltage. But if you charge it through a resistor then it will take time to become full of charge. Figure 3-3 shows how a capacitor can be charged or discharged through the use of the switches S1 and S2.

When you close switch S1, C1 will charge through R1 until C1 reaches the battery voltage. Open S1 again and the now charged capacitor will retain its charge. Eventually the capacitor will lose its charge through self-discharge.

If you now close S2, C1 will now discharge through R2 and LED1, which will light brightly at first and then more dimly as C1 is discharged.

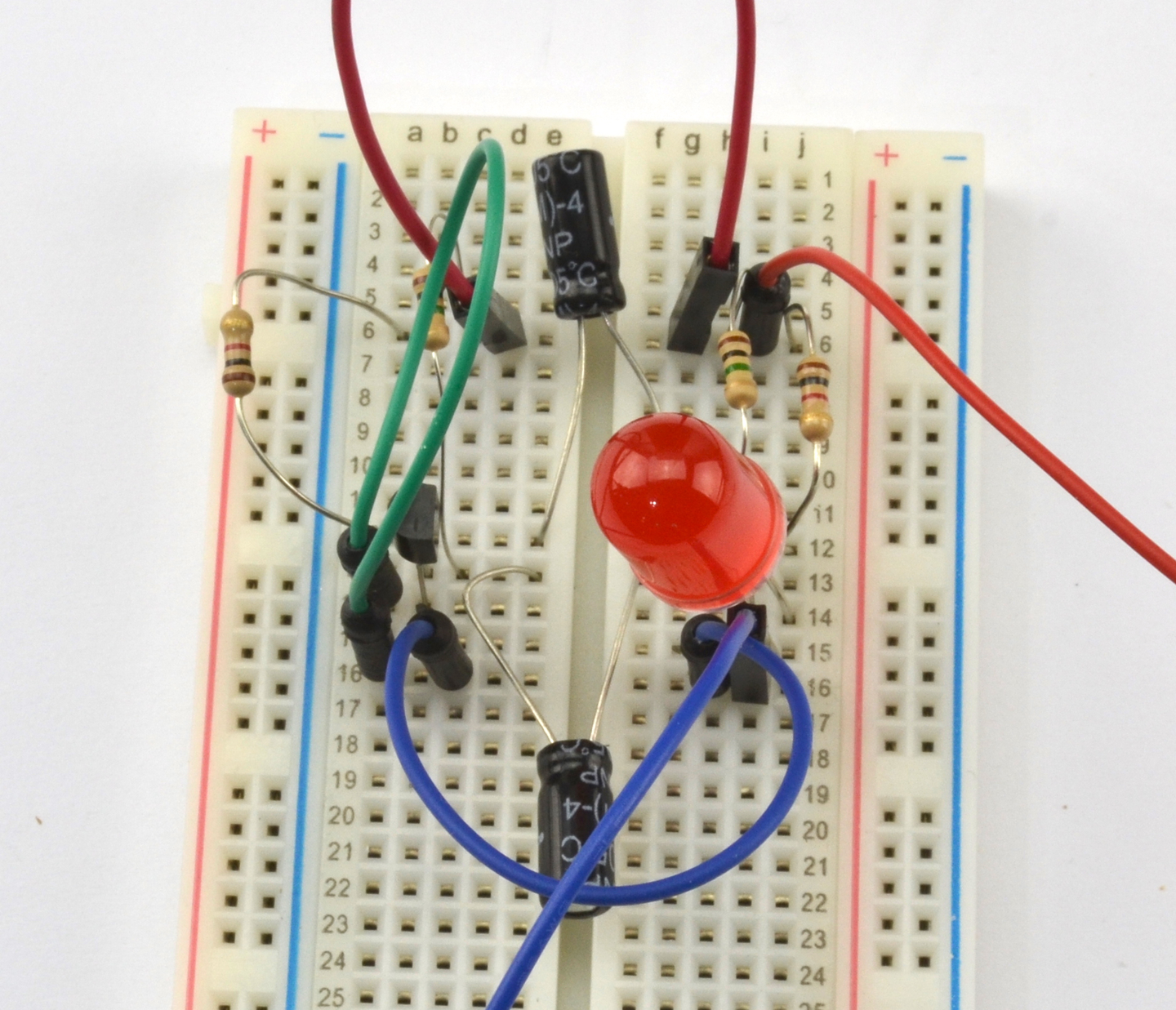

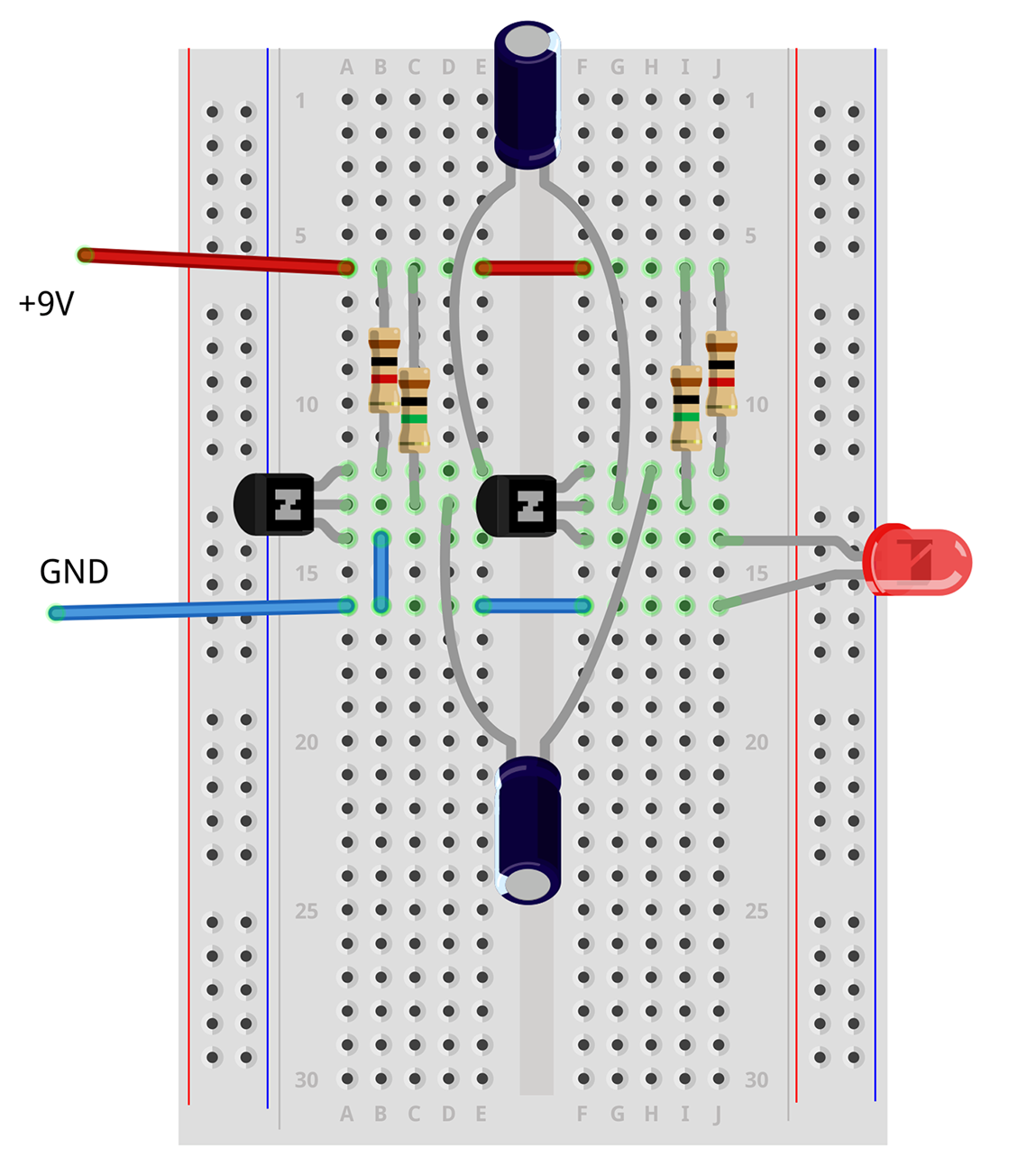

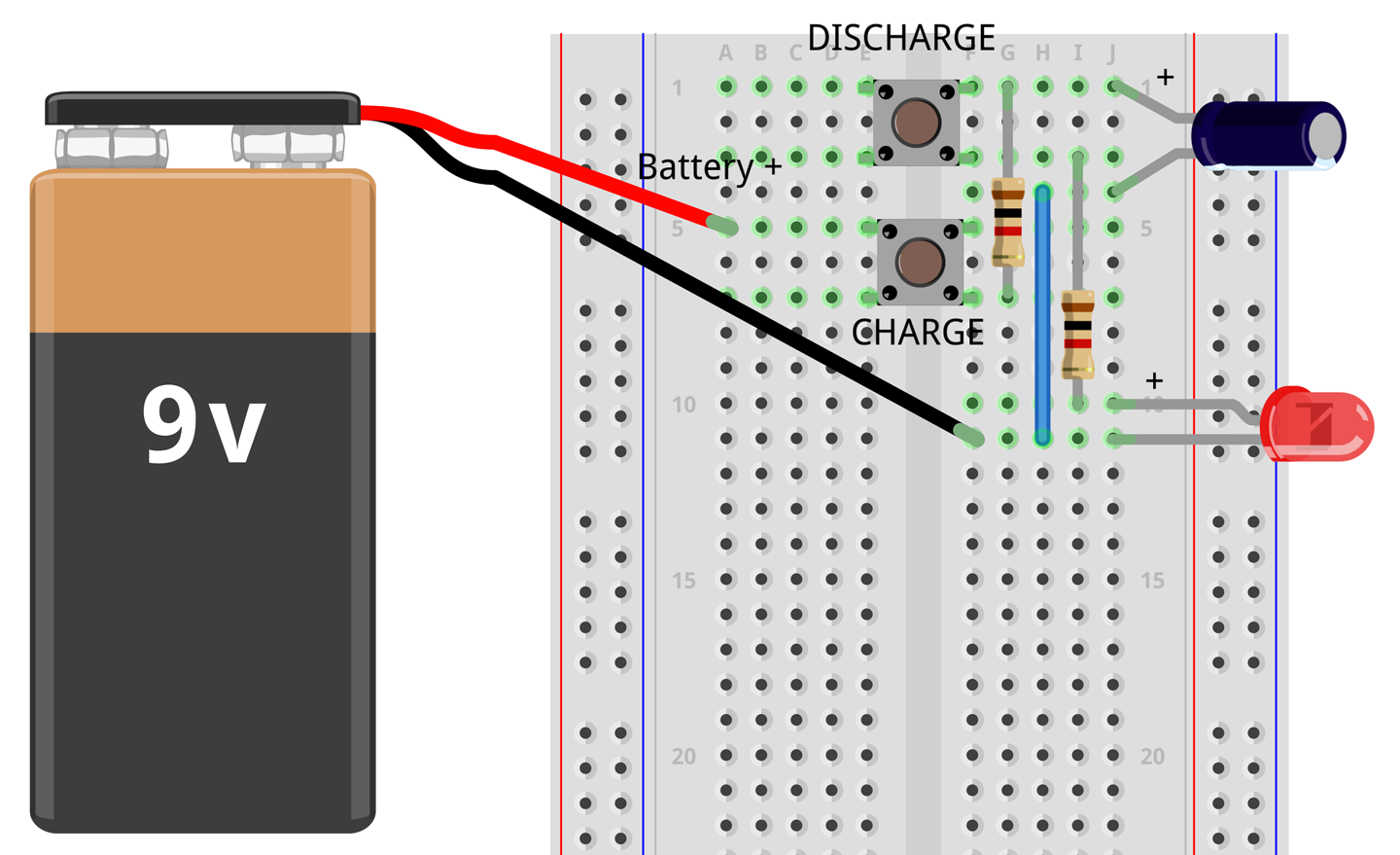

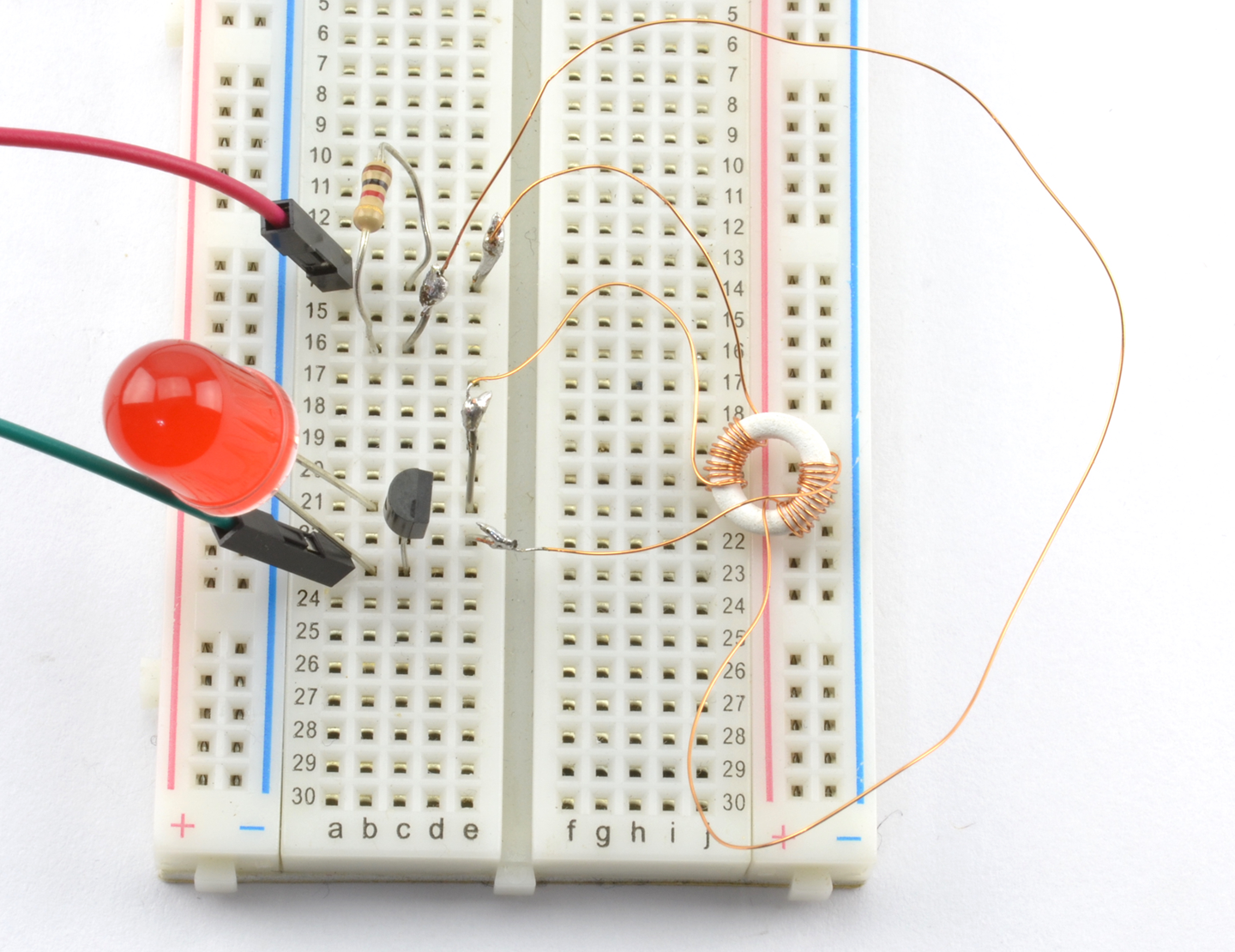

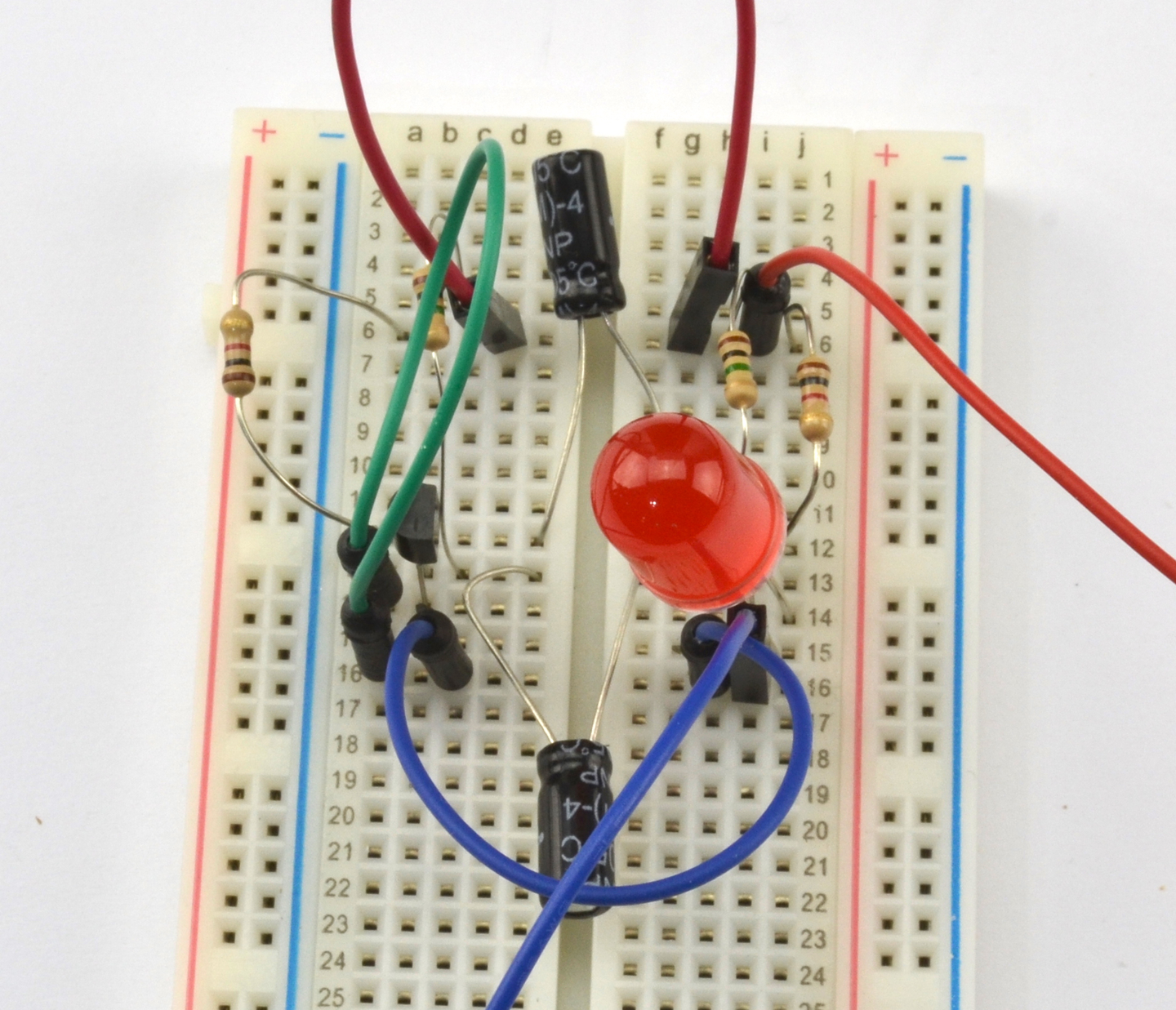

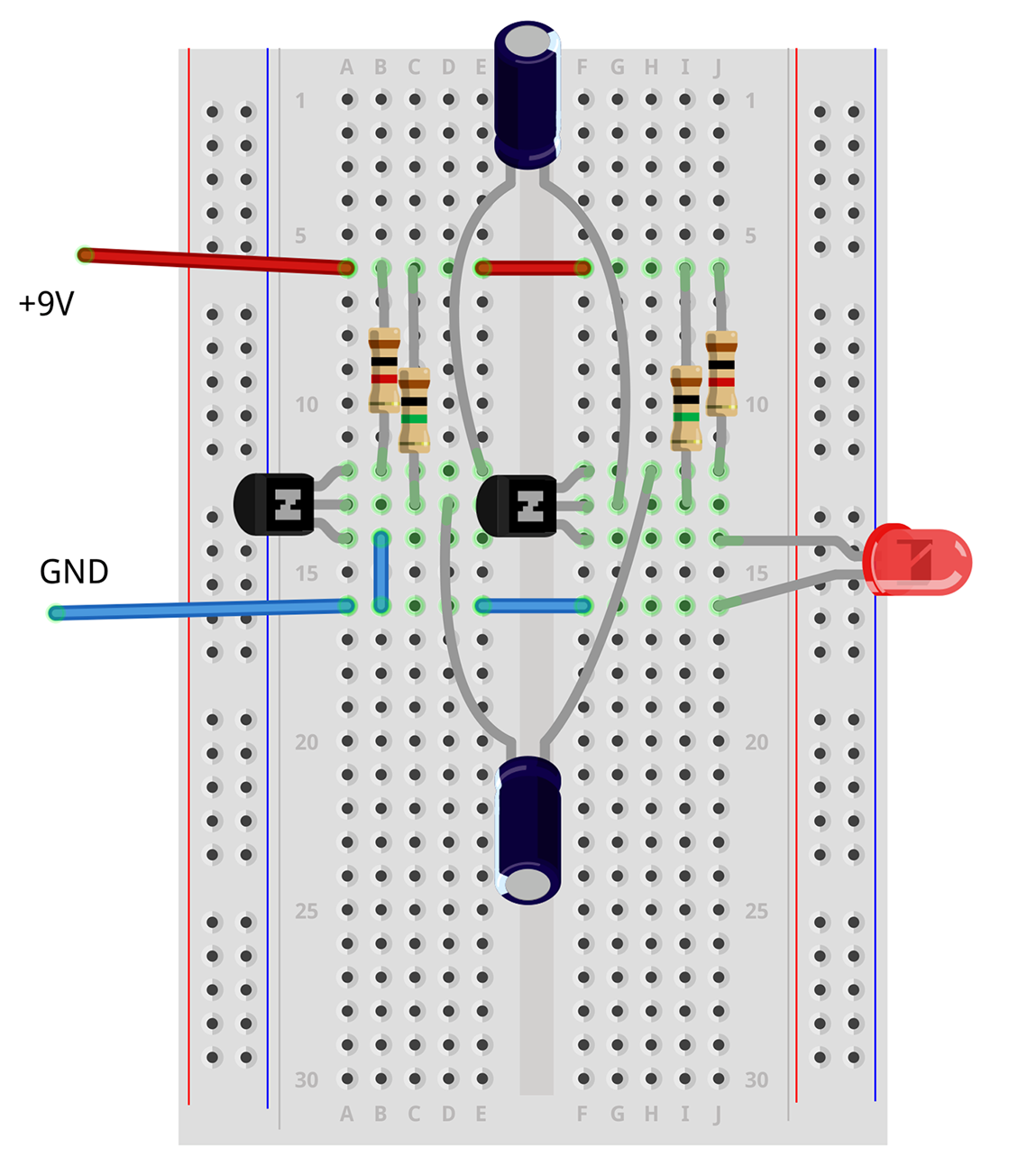

If you want to experiment with the schematic diagram of Figure 3-3, then build up the breadboard diagram shown in Figure 3-4. For an introduction to breadboard, see Recipe 20.1. Use 1kΩ resistors and a 100µF capacitor.

Press the button labeled CHARGE for a second or two to charge the capacitor then release the button and press the DISCHARGE button. The LED should glow brightly for a second or so and then dim until it extinguishes after a second or so.

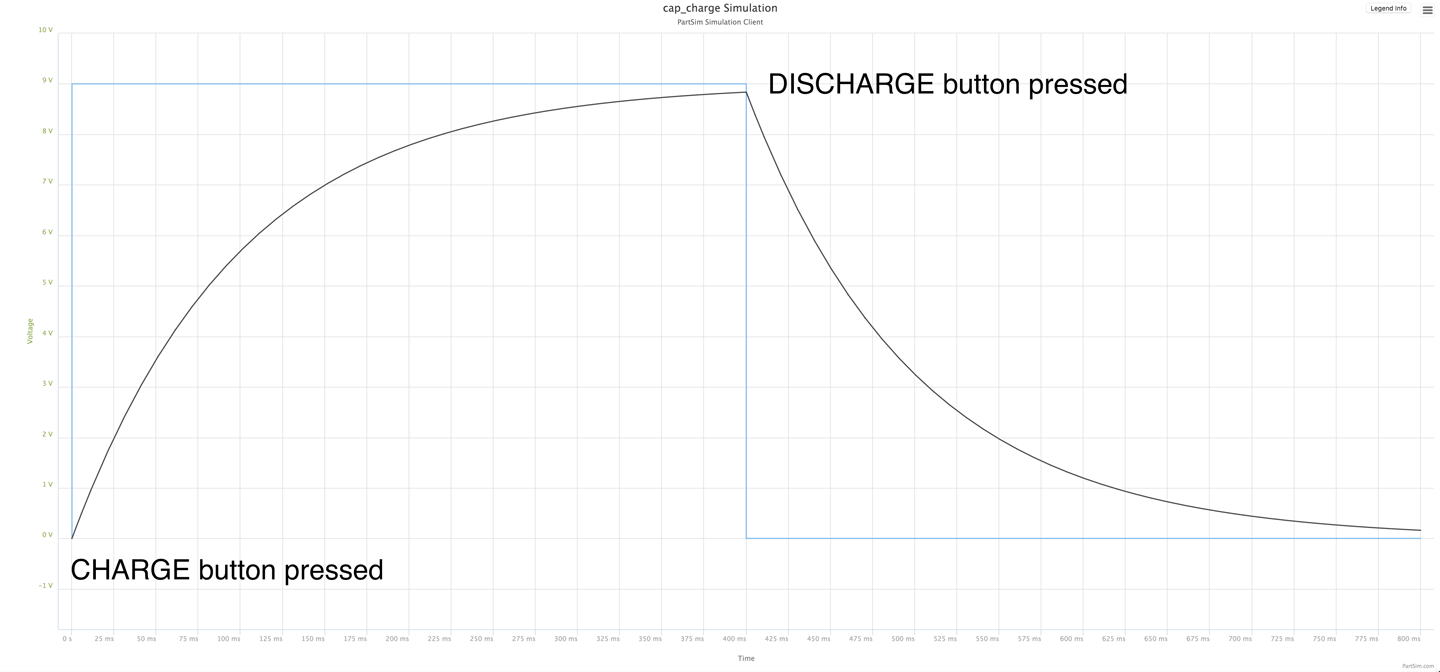

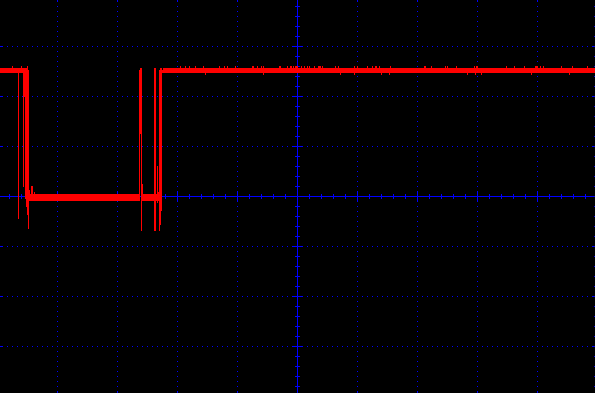

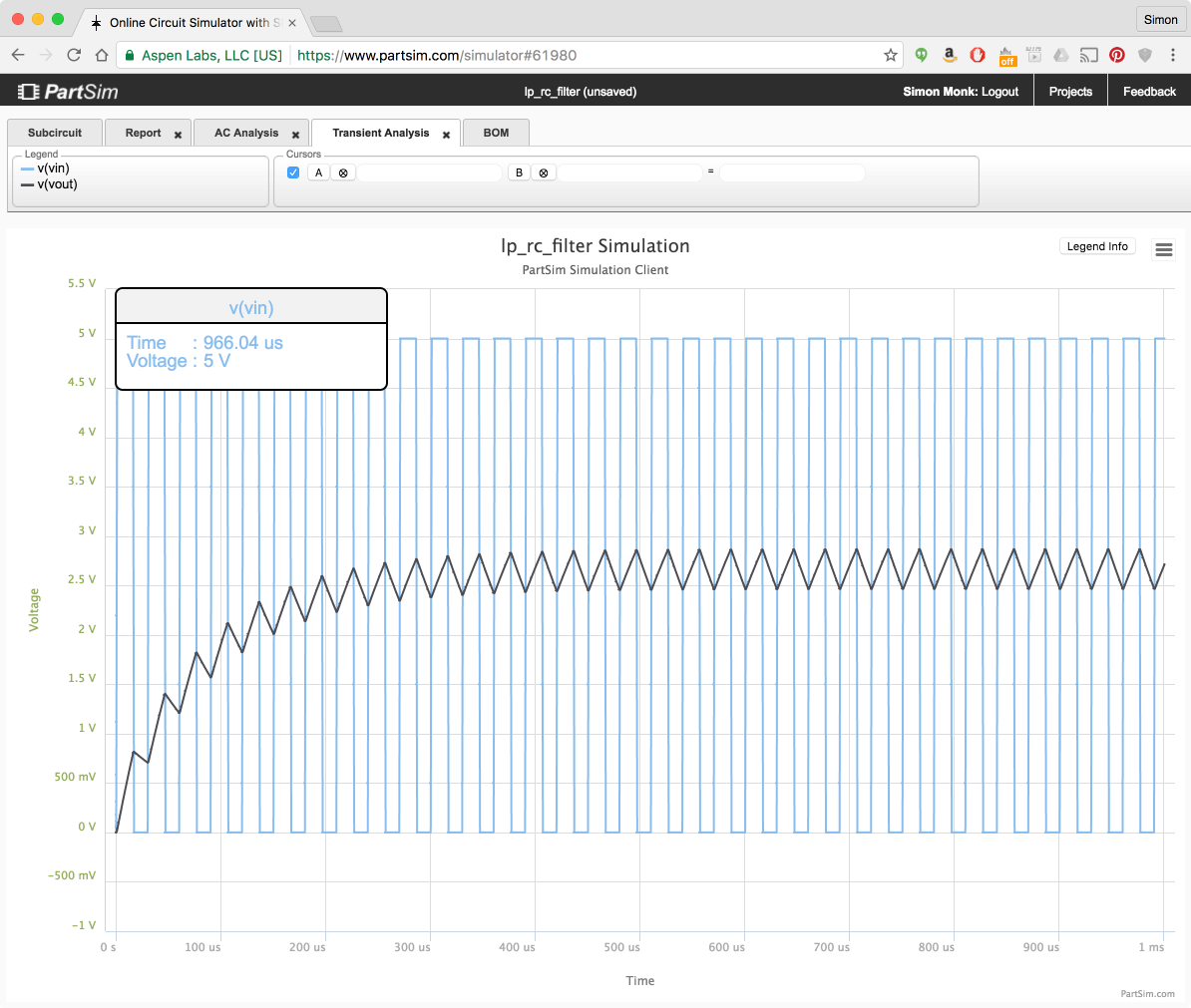

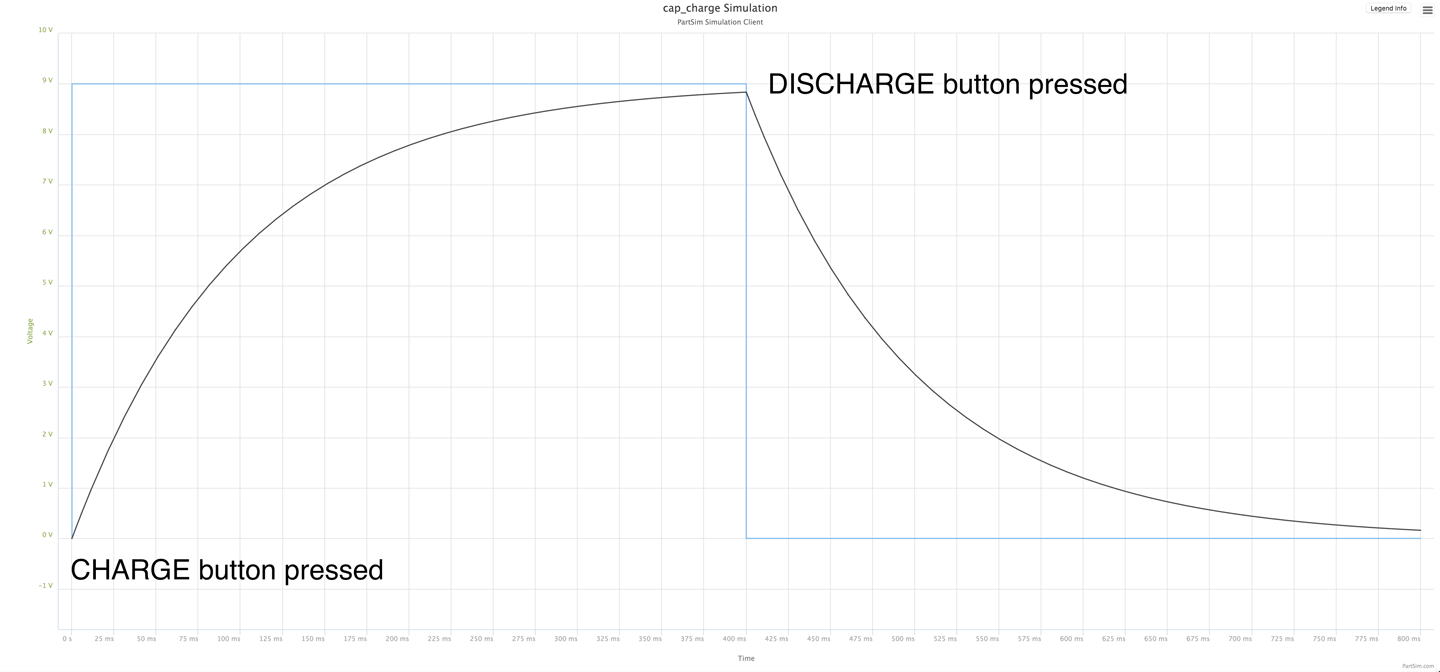

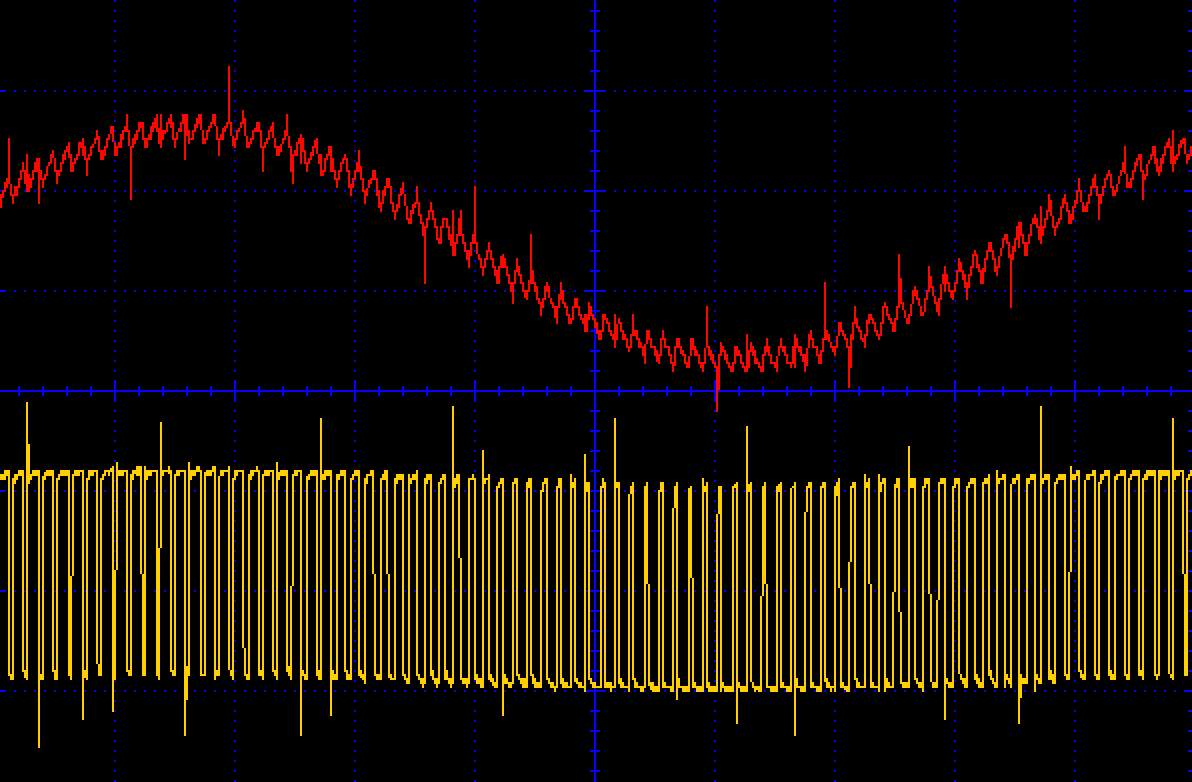

If you were to monitor the voltage across the capacitor while it was first being charged and then discharged, you would see something similar to Figure 3-5.

In Figure 3-5 the square-shaped waveform is the voltage applied to the capacitor through a 1kΩ resistor. For the first 400ms this is 9V. But as you can see the voltage across the capacitor does not increase linearly, but rather increases faster at first and then gradually tails off as the voltage across the capacitor gets closer to the battery voltage.

Similarly, when the capacitor discharges, the voltage decreases sharply at first and then starts to tail off.

So, if a capacitor stores electrical energy, you may be wondering how this differs from a rechargeable battery. Well, in fact a special type of very high capacitance capacitor called a supercapacitor is sometimes used in place of a rechargeable battery for applications that require a very rapid storage and release of energy. The differences between a capacitor and a battery include:

For information on using a solderless breadboard, see Recipe 20.1.

The voltage curves of Figure 3-5 were created using a circuit simulator (Recipe 21.11). You can experiment with this simulation online using PartSim at http://bit.ly/2mrtrhs.

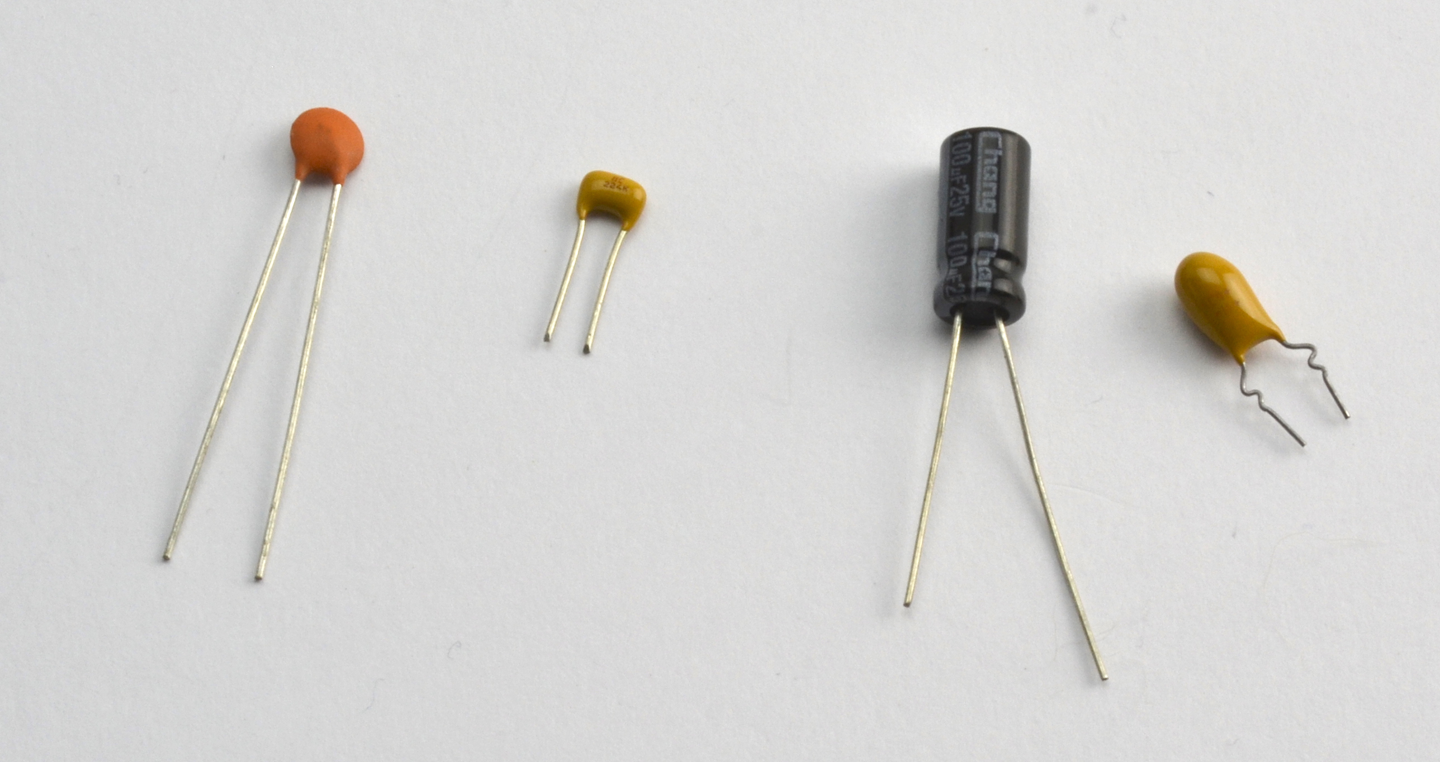

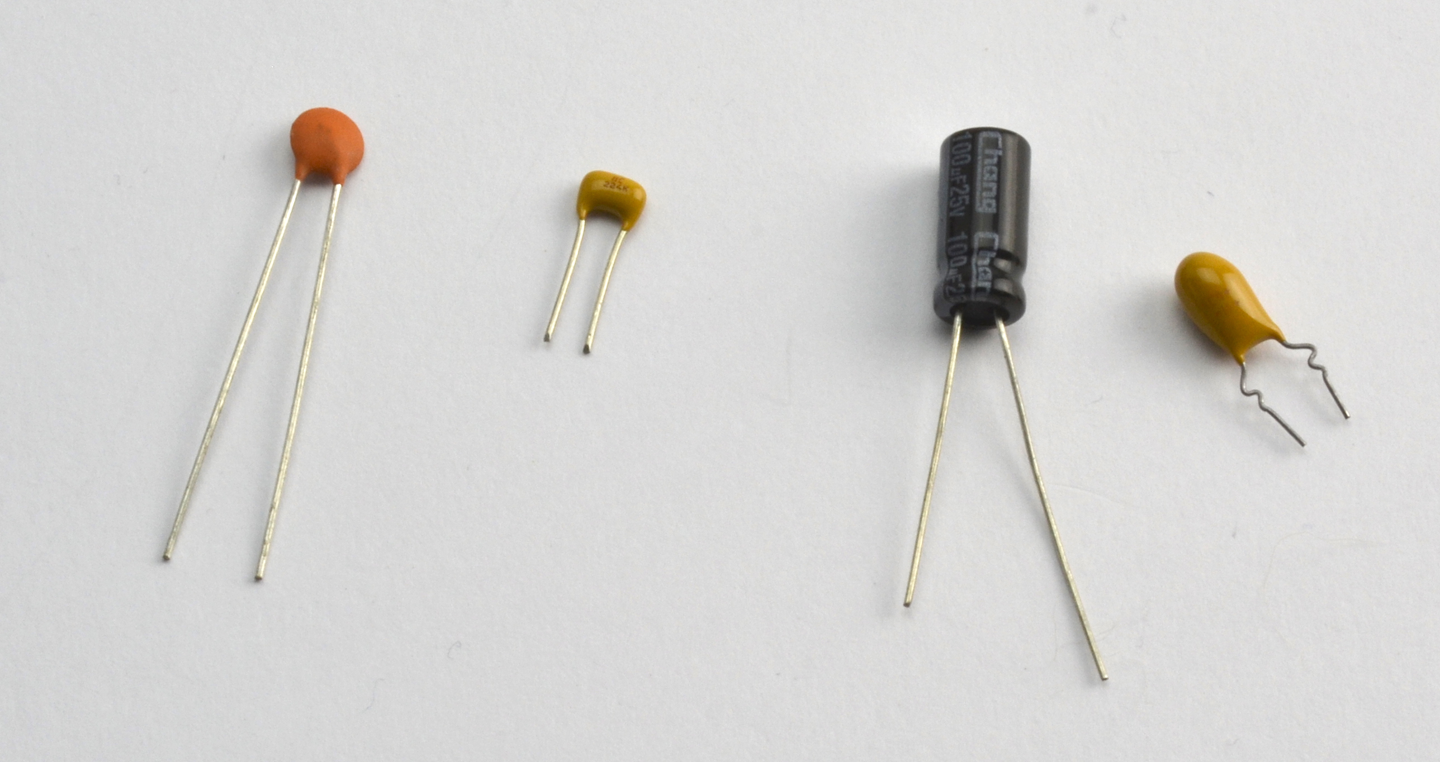

Unless your application needs capacitors with special features, the following rule of thumb applies.

In most cases, for capacitors between 1pF and 1nF use a disc capacitor (Figure 3-6a). For capacitors between 1nF and 1µF use a multilayer ceramic capacitor (MLC; Figure 3-6b) and for capacitors above 1µF use an aluminum electrolytic capacitor (Figure 3-6c). The rightmost capacitor is a tantulum electrolytic capacitor.

Although disc ceramic, MLC, and aluminum electrolytic capacitors are the most commonly used types of capacitor, there are other types:

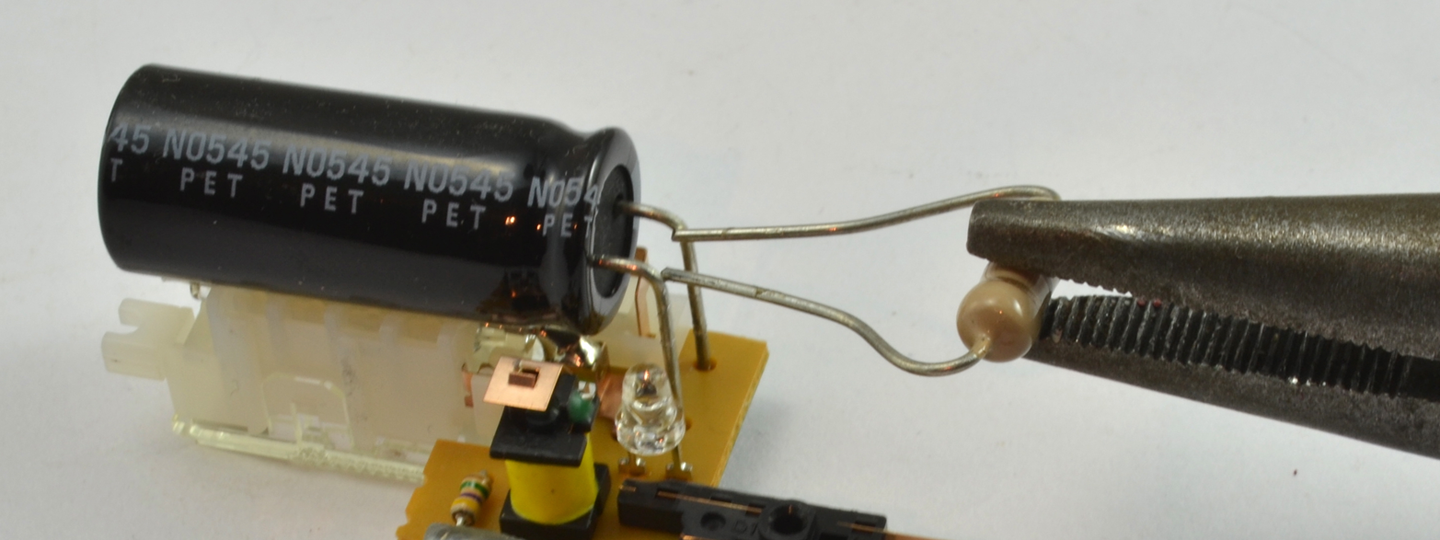

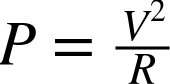

Capacitors are less reliable than resistors. Exceed the voltage rating and you are likely to damage the insulating layer. Electrolytic capacitors use an electrolyte contained in an aluminum can that creates a very thin layer of oxide as the insulator. These are especially prone to failure due to overvoltage, or overtemperature, or just age. If vintage HiFi equipment fails, it is usually the large electrolytic capacitors in the power supplies that are the cause of the failure. In addition, if an electrolytic capacitor does fail then it can spray out the electrolyte in a somewhat messy manner.

In addition to the actual capacitance of a capacitor, there are a number of other factors to consider when selecting a device. Of critical importance is the voltage rating. Unless you are creating something that uses high voltages, this is not usually a problem with smaller value capacitors, as they are generally rated at least 50V. However, as soon as you get into the range of electrolytics then you will be in a trade-off between capacitor size and voltage. Electrolytic capacitors are commonly available in voltage ratings of 6.3V, 10V, 25V, 30V, 40V, 50V, 63V, 100V, 160V, 200V, 250V, 400V, and 450V. It is unusual to find electrolytic capacitors with a higher voltage rating than 500V.

The temperature rating becomes important when the capacitors are being rapidly charged and discharged, as a capacitor will always have an internal resistance called its equivalent series resistance (ESR) that causes heating during charging and discharging.

Small-value MLC capacitors generally have a very low ESR of little more than the resistance caused by their leads. This allows them to charge and discharge extremely quickly. A high-value electrolytic capacitor might have an ESR of a few hundred mΩ. This both limits the speed at which the capacitors can charge and discharge and causes a heating effect.

For the use of electrolytic capacitors to smooth out voltage ripple from power supplies, see Recipe 7.4.

Small, low-value SMD capacitors are generally unmarked, and so you should label them as soon as you buy them.

Electrolytic capacitors usually have their capacitance value and voltage rating printed on the package. Polarized through-hole electrolytic capacitors are also usually supplied with the positive lead longer than the negative lead and the negative lead marked with a minus sign or a diamond symbol.

Most other capacitors use a numbering system similar to that of SMD resistors. The value is usually three digits and a letter. The first two digits are the base value and the third digit is the number of zeros to follow. The base value being the value in pF (pico Farad; see Appendix D).

For example, a 100pF capacitor would have the three digits 101 (a 1, a 0, followed by one further 0). A 100nF capacitor would be marked 104 (a 1, a 0, followed by four further 0s); that is, 100,000 pF or 100nF.

The letter after the digits indicates the tolerance (J, K, or M for ±5%, ±10%, and ±20%, respectively).

To read resistor color codes, see Recipe 2.1.

Looking at Figure 3-7, you can see two capacitors in parallel double up on the surface area of the conductive plates and therefore may correctly assume that the overall capacitance is the sum of the two capacitances.

It is actually quite common to place a number of capacitors in parallel to increase the overall capacitance. It is especially common when smoothing a high-power transformer-based power supply for, say, an audio amplifier where it is important to remove as much ripple from the power supply as possible (see Recipe 7.2).

In such systems it is common to use a number of different capacitors of different types and values in parallel to minimize the effects of ESR (see Recipe 3.2).

For capacitors in series, see Recipe 3.5.

It is unusual to connect capacitors in series. Occasionally, this will be done as part of a more complex circuit such as in Recipe 7.12.

For capacitors in parallel, see Recipe 3.4.

Supercapacitors are low-voltage capacitors that have extremely high capacitances. They are primarily used as energy-storage devices in situations that would otherwise use rechargeable batteries.

They can have values up into the hundreds of F (Farads). Note that the top of the capacitance range for an aluminum electrolytic is around 0.22F.

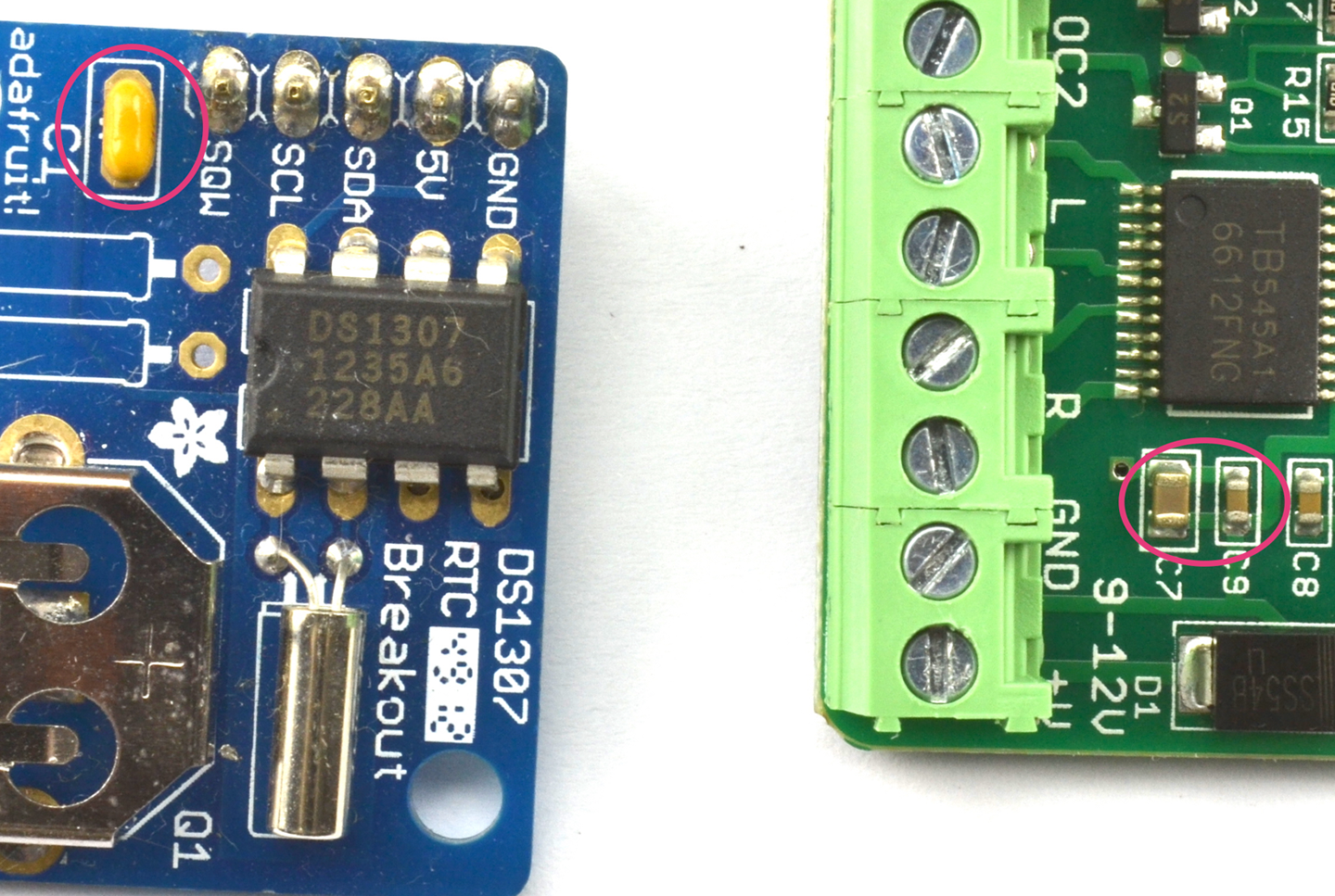

Low (comparatively) value supercapacitors of perhaps a few F are sometimes used as alternatives to rechargeable batteries or long-life lithium batteries to power ICs in standby mode to retain memory in static RAM that would otherwise be lost, or to power real-time clock (RTC) chips so a device using an RTC IC will keep the time if it’s powered off for a while.

Extremely high-value supercapacitors are available that offer an alternative to rechargeable batteries for larger capacity energy storage.

Supercapacitors with values of 500F or more can be bought for just a few dollars. The maximum voltage for a supercapacitor is 2.7V so, for higher voltage use, the capacitors can be placed in series with special protection circuitry to ensure the 2.7V limit is not exceeded as the bank of capacitors are charged.

Supercapacitors generally look like standard aluminum electrolytic capacitors. At present, their energy storage is still quite a long way from that of rechargeable batteries and because they are capacitors, the voltage decreases much more quickly than when discharging a battery.

See Recipe 3.7 to calculate the energy stored in super capacitors and normal capacitors.

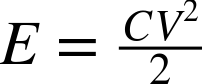

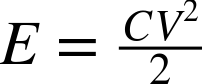

The energy stored in a capacitor in J is calculated as:

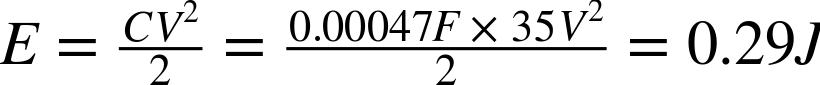

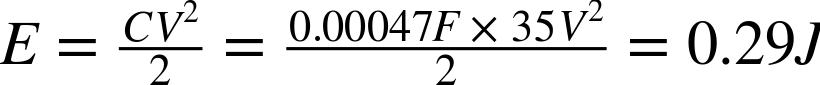

Taking a medium-sized electrolytic of 470µF at 35V the energy stored would be:

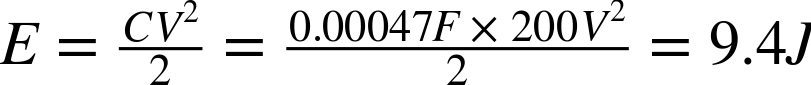

which is not very much energy. Since the energy storage is proportional to the square of the voltage, the results for a capacitor of the same value but at 200V are much more impressive:

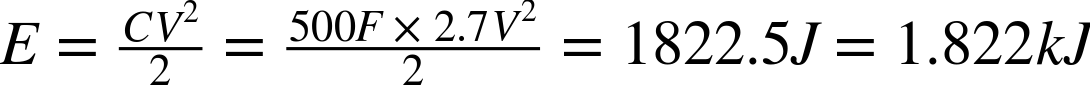

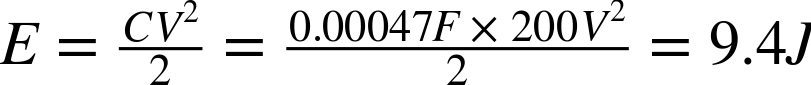

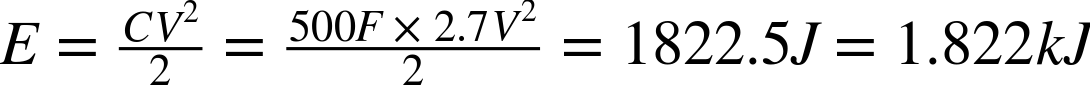

For a 500F 2.7V supercapacitor, the results are even more impressive:

By way of comparison, a single 1.5V AA battery of 2000mAH stores around:

For information on rechargeable batteries, see Recipe 8.3.

An inductor is, at its simplest, just a coil of wire. At DC, it behaves just like any length of wire and will have some resistance, but when AC flows through it, it starts to do something interesting.

A change in current in one direction in an inductor causes a change in voltage in the opposite direction. This effect is more marked the higher the frequency of the AC flowing through the inductor. The net result of this is that the higher the frequency of the AC, the more the inductor resists the flow of current. So as not to confuse this effect with ordinary resistance, it is called reactance but it still has units of Ω.

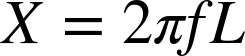

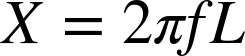

The reactance X of an inductor can be calculated by the formula:

Where f is the frequency of the AC (cycles per second) and L is the inductance of the inductor whose units are the Henry (H). This resistive effect does not generate heat like a resistor, but rather returns the energy to the circuit.

The inductance of an inductor will depend on the number of turns of wire as well as what the wire is wrapped around. So, very low-value inductors may be just a couple of turns of wire without any core (called air-core inductors). Higher value inductors will generally use an iron or more likely ferrite core. Ferrite is a magnetic ceramic material.

The current-carrying capability of an inductor generally depends on the thickness of the wire used in the coil.

Inductors are used in switched mode power supplies (SMPS) where they are pulsed at a high frequency (see Recipe 7.8 and Recipe 7.9). They are also used extensively in radio-frequency electronics, where they are often combined with a capacitor to form a tuned circuit (see Chapter 19).

A type of inductor called a choke is designed to let DC pass while blocking the AC part of a signal. This prevents unwanted radio-frequency noise from infiltrating a circuit. You will often find a USB lead has a lump in it near one end. This is a ferrite choke, which is just a cylinder of ferrite material that encloses the cables and increases the inductance of the wire to a level where it can suppress high-frequency noise.

For more information on the use of inductors in SMPSs, see Recipe 7.8 and Recipe 7.9.

See Recipe 3.9 for more information on transformers.

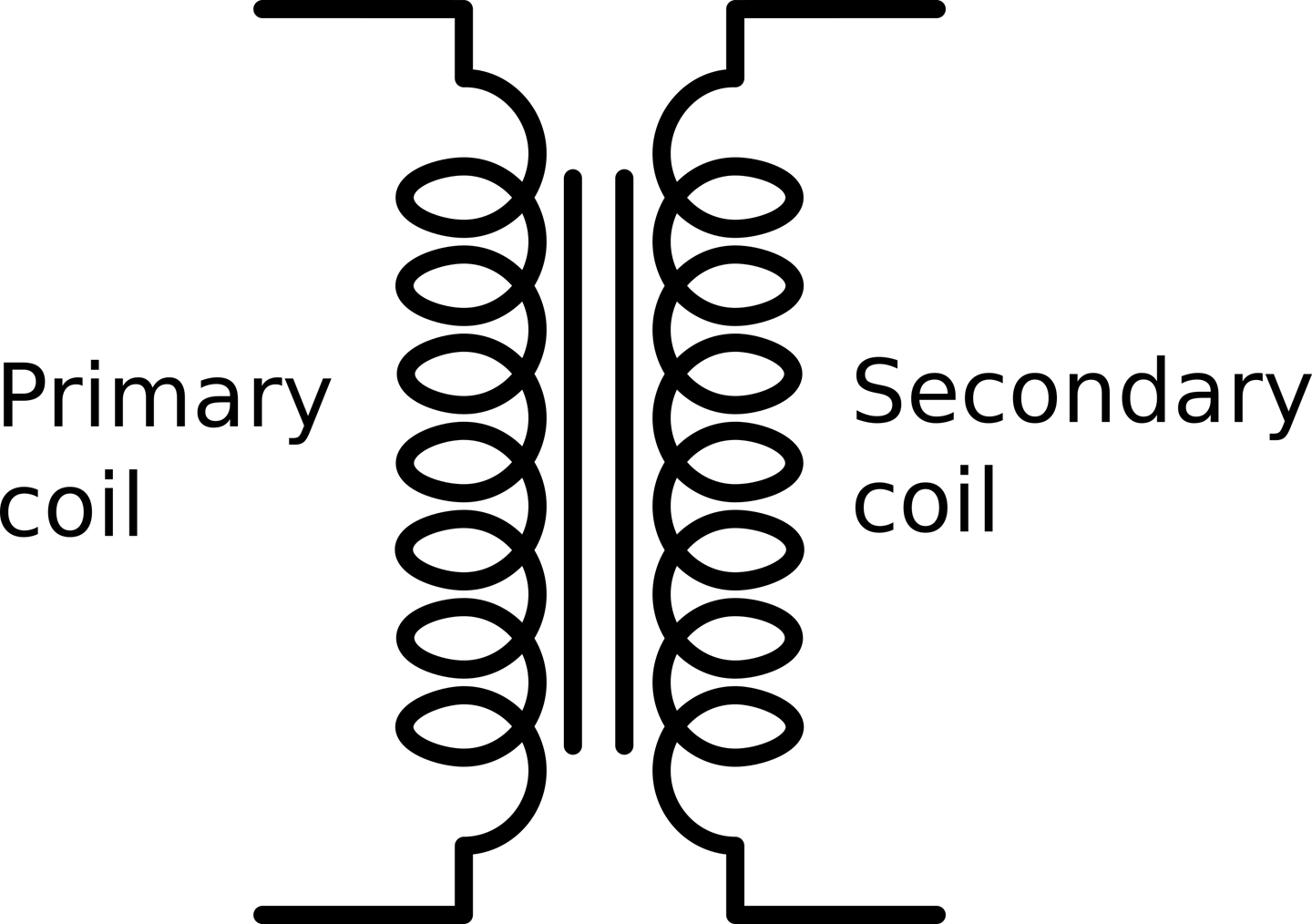

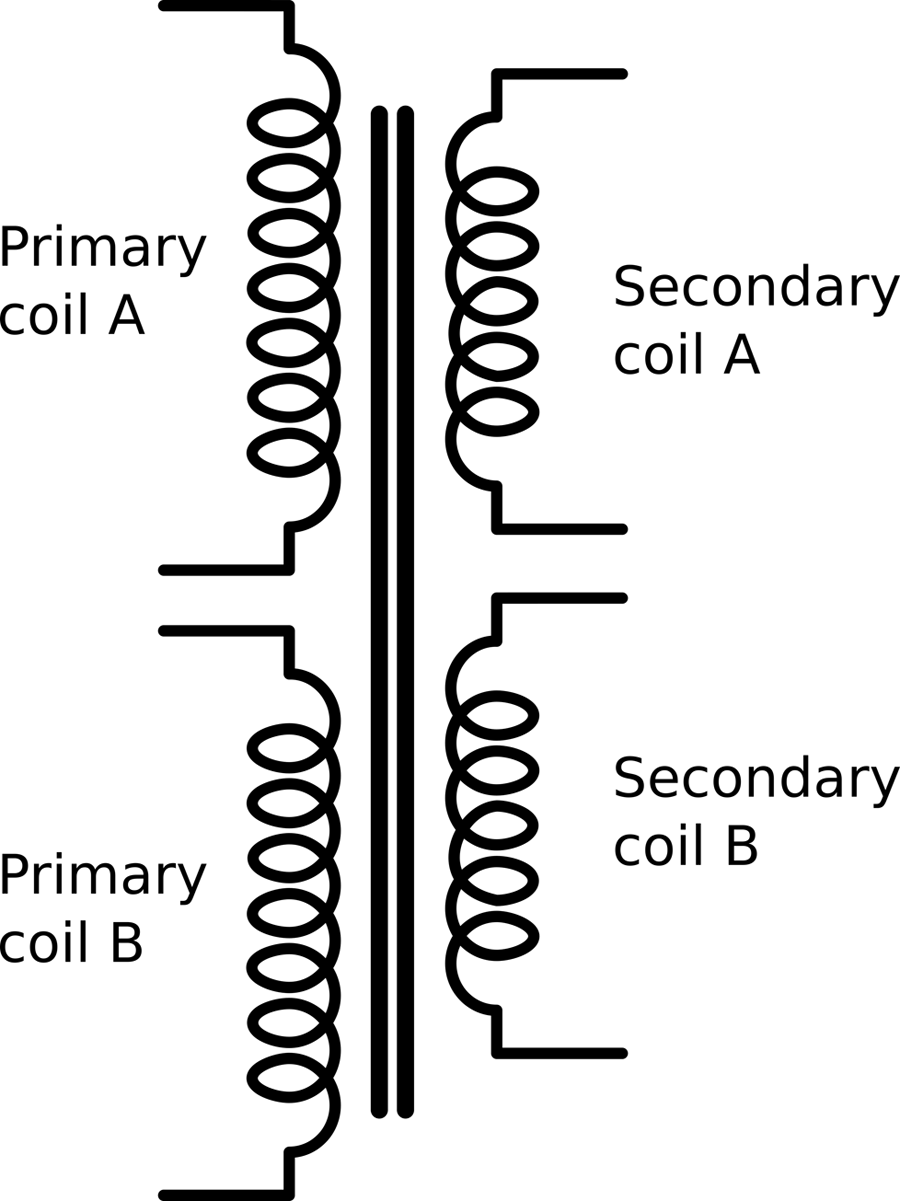

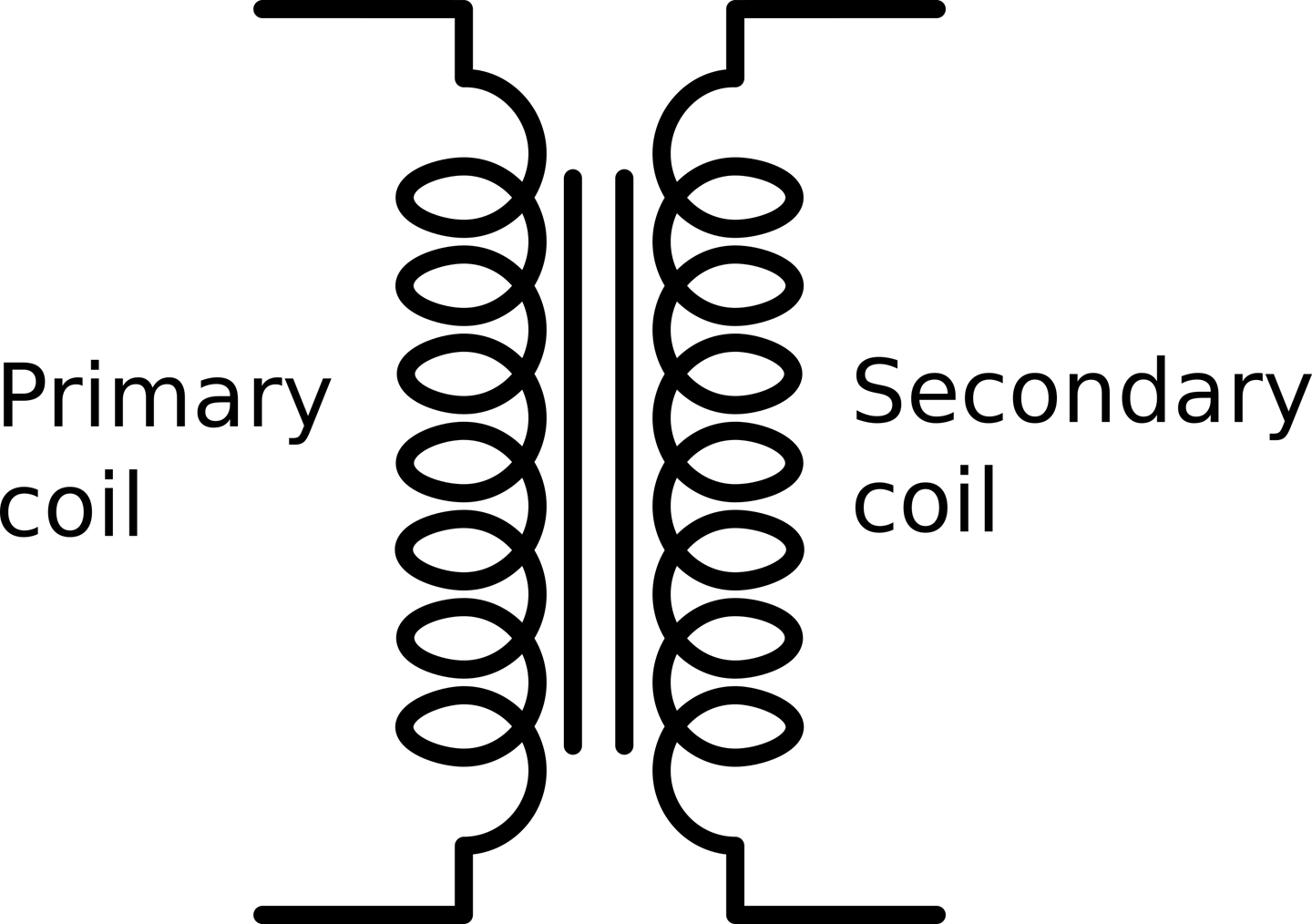

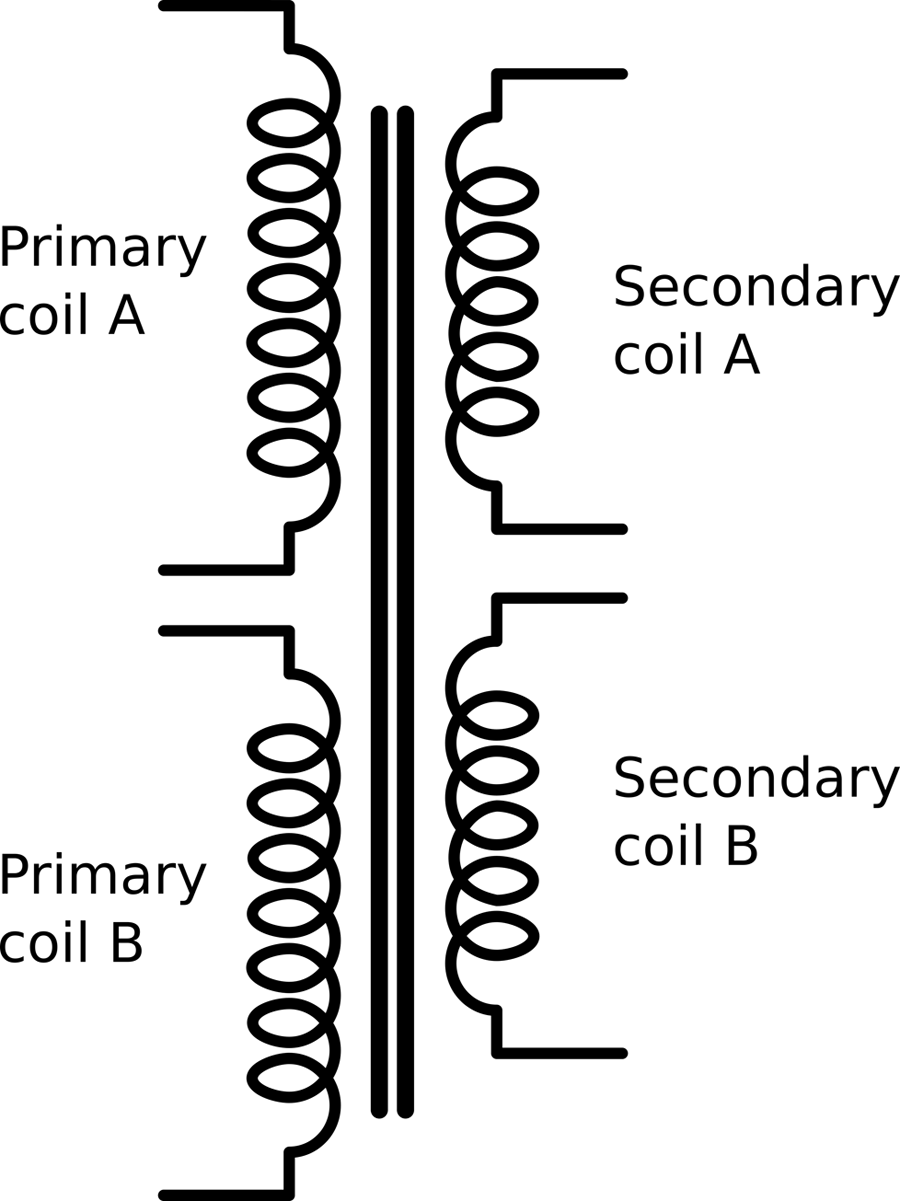

A transformer is essentially two or more inductor coils wrapped onto a single core. Figure 3-8 shows the schematic diagram for a transformer that also gives a clue as to how it works.

A transformer has primary coils and secondary coils. Figure 3-8 shows one of each. The primary coil is driven by AC, say the 110V from an AC outlet, and the secondary is connected to the load.

The voltage at the secondary is determined by the ratio of the number of turns on the primary to the number of turns on the secondary. Thus if the primary has 1000 turns and the secondary just 100, then the AC voltage will be reduced by a factor of 10.

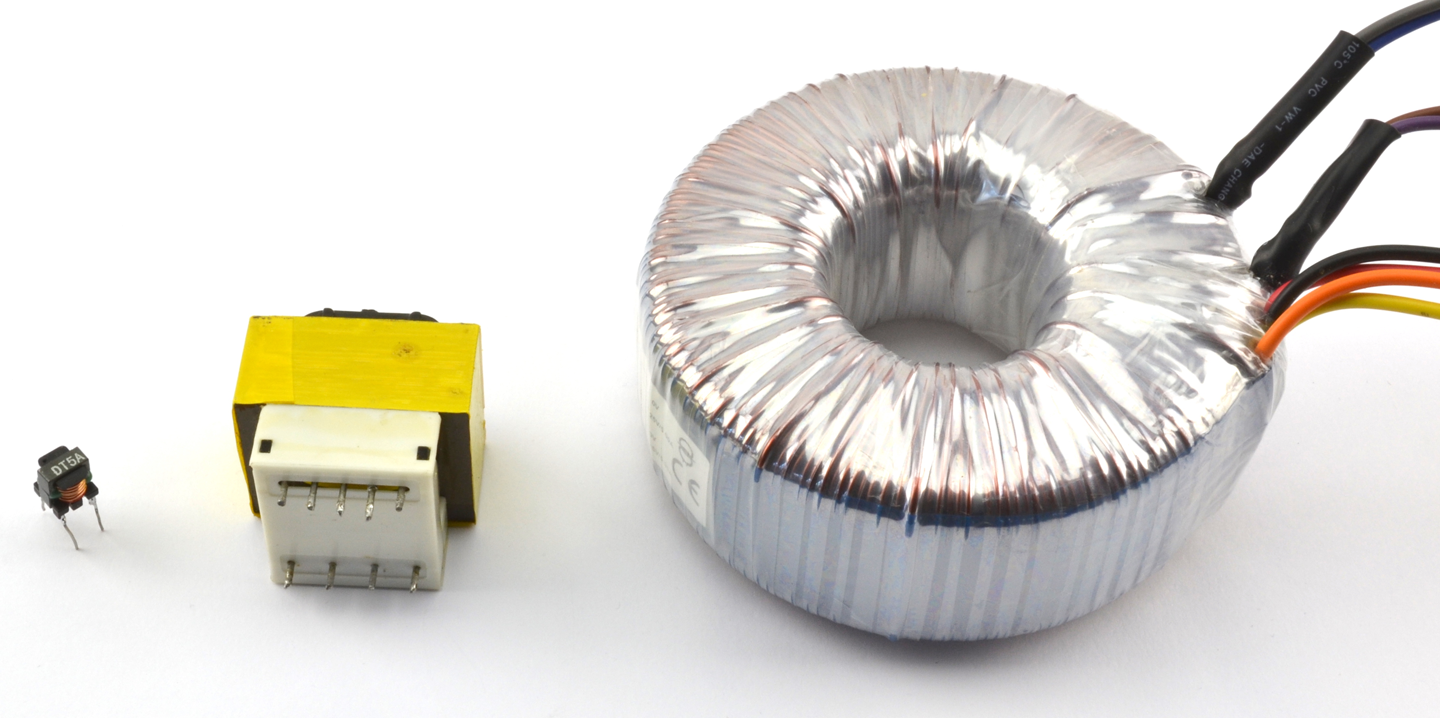

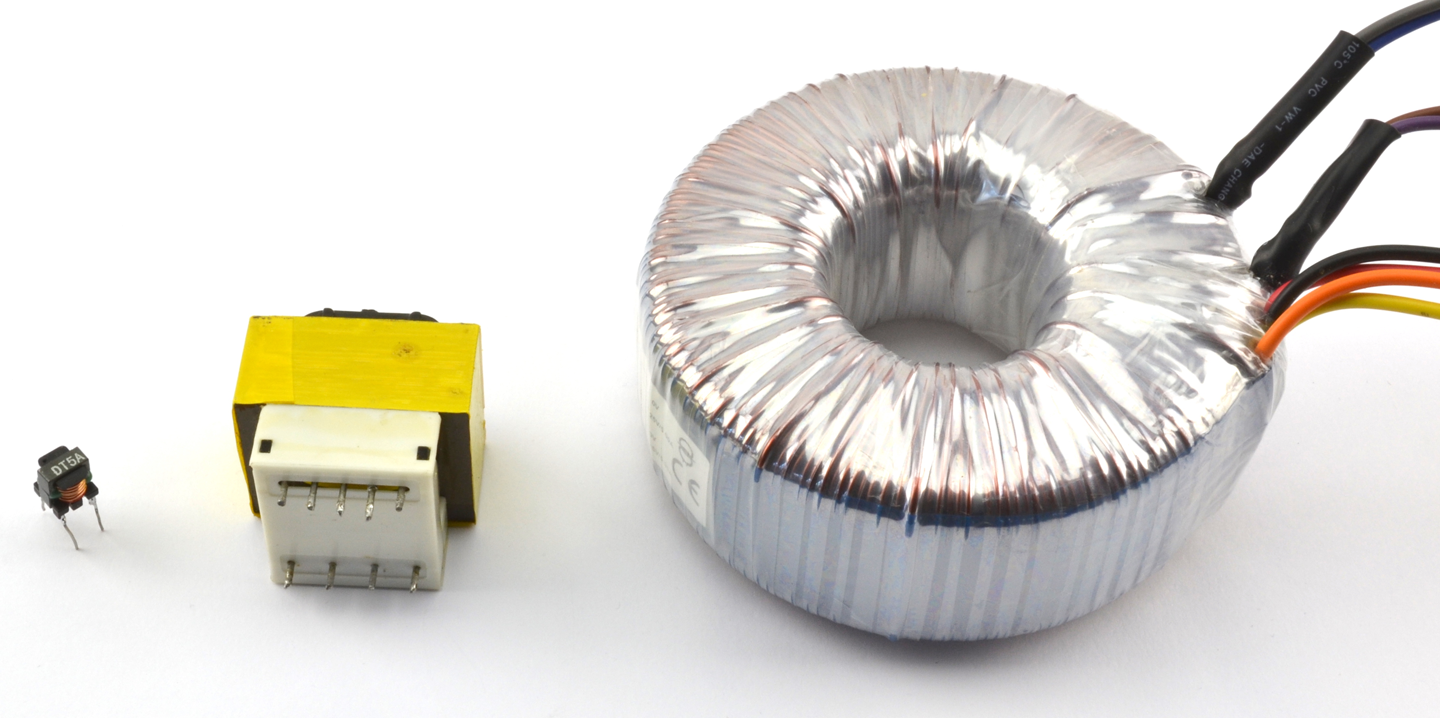

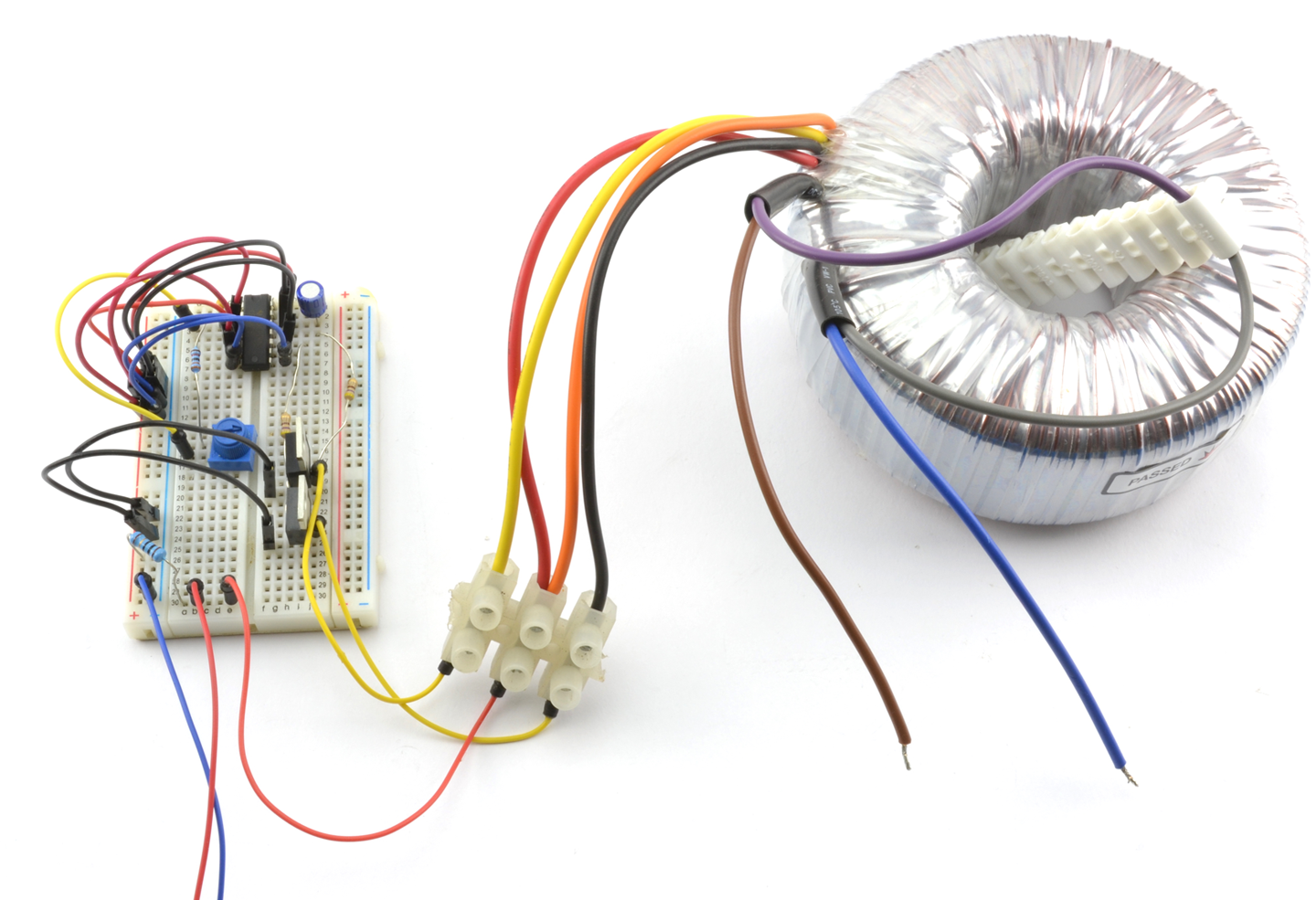

Figure 3-9 shows a selection of transformers. As you can see they come in a wide range of sizes.

In Figure 3-9 there is a small high-frequency transformer on the left that was taken from a disposable flash camera where it was used to step up pulsed DC (almost AC) from a 1.5V battery to the 400V needed by a Xenon flash tube.

The type of transformer shown in the center is commonly used to step-down 110V AC to a low voltage, say 6V or 9V.

The transformer on the right is also designed to step-down AC outlet voltages to lower voltages. It is called a torroidal transformer and the primary and secondary coils are wrapped around a single torroidal former (donut shaped arrangement of iron layers), on top of each other. These transformers are often used in HiFi equipment where the noise found in most SMPSs is considered too high for high-end HiFi amplifiers.

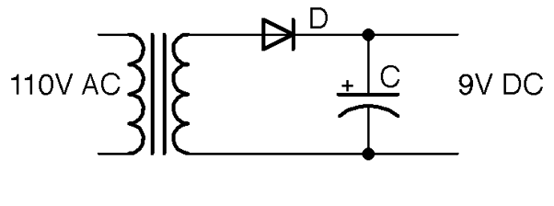

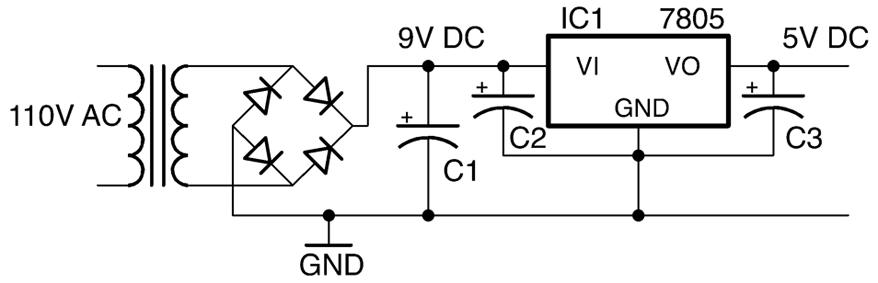

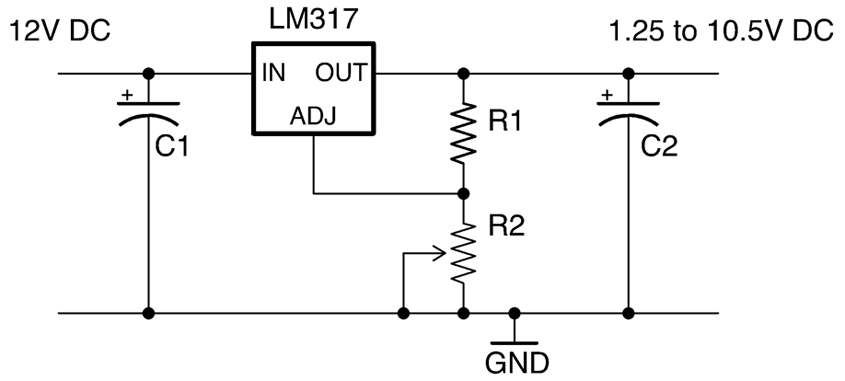

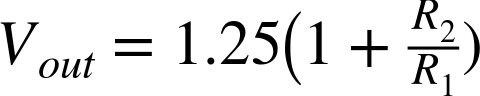

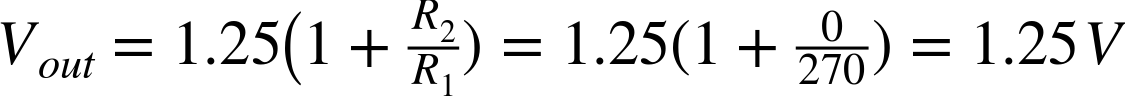

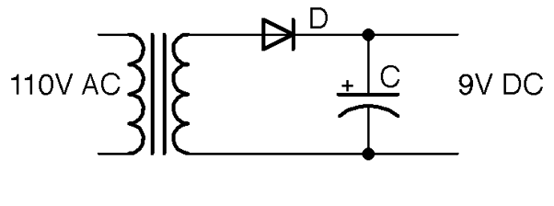

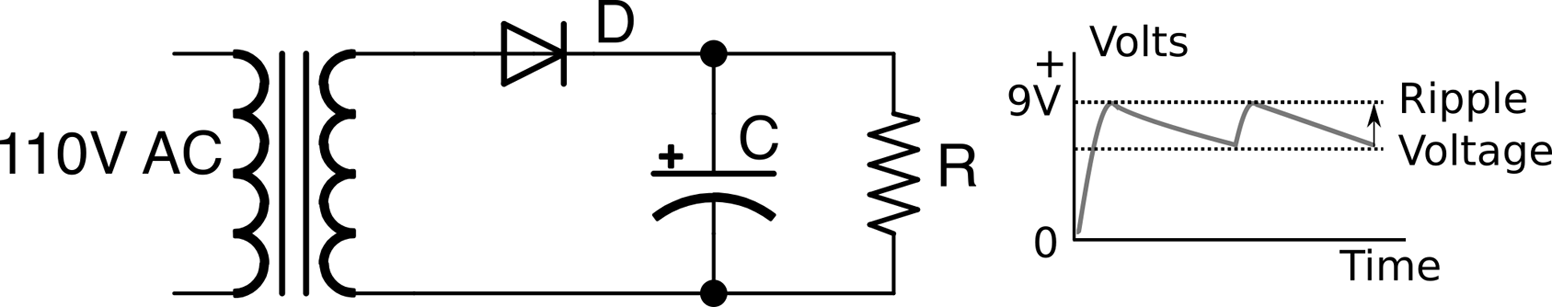

It used to be that if you wanted to power a low-voltage DC appliance such as a radio receiver from an AC outlet, then you would first use a transformer to drop the 100V AC at 60Hz to, say, 9V. You would then rectify and smooth the low-voltage AC into DC.

These days, an SMPS (see Recipe 7.8) is normally used as transformers are expensive and heavy items with iron and long lengths of copper-winding wire. However, transformers are still used in SMPS but operate at a very much higher frequency than 60Hz. Operating at a high frequency (often 100s of kHz) allows the transformers to be much smaller and lighter than low-frequency transformers while retaining good efficiency.

This video shows a torroidal transformer winding machine in action: https://youtu.be/82PpCzM2CUg.

Recipe 7.1 describes how to use a transformer to convert one AC voltage to another.

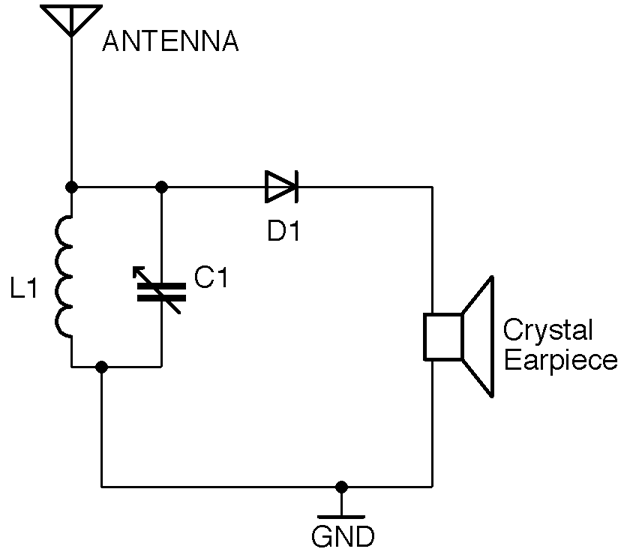

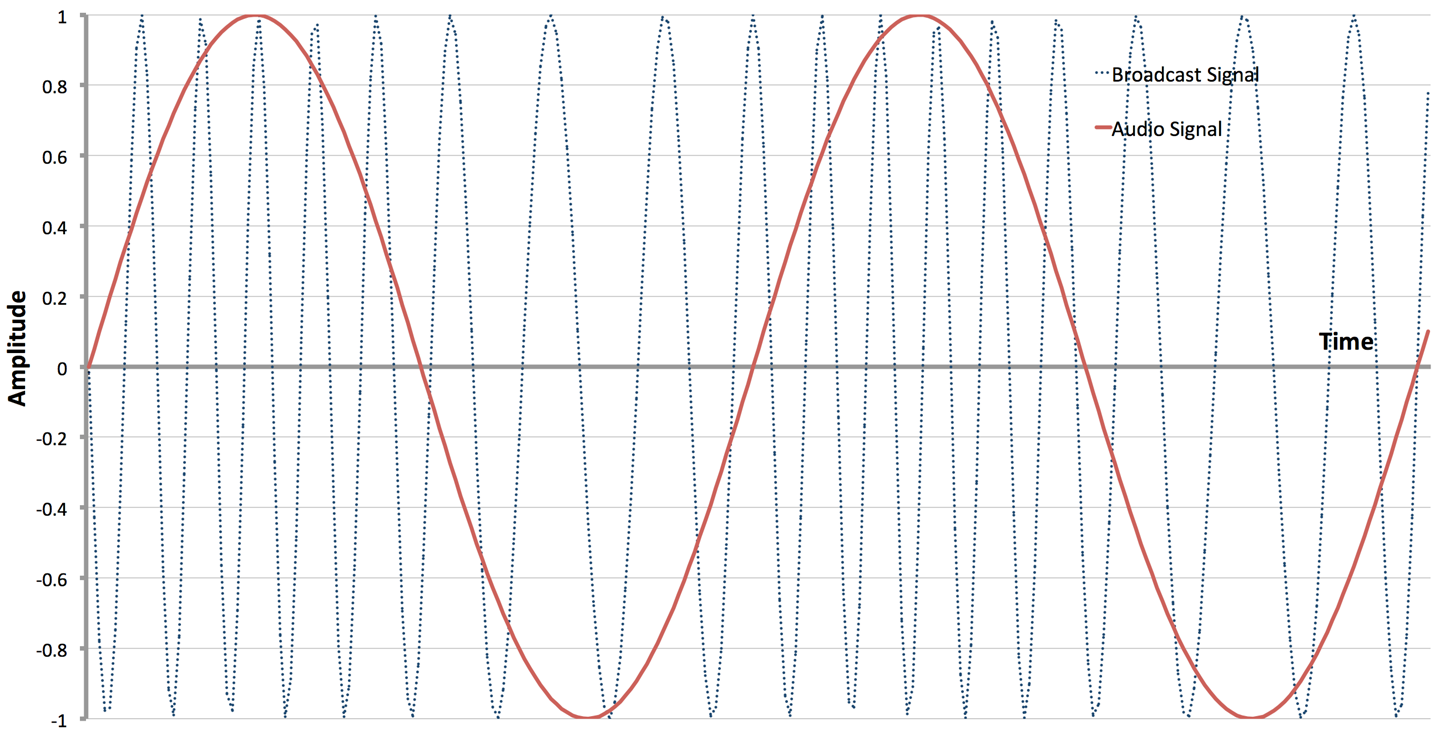

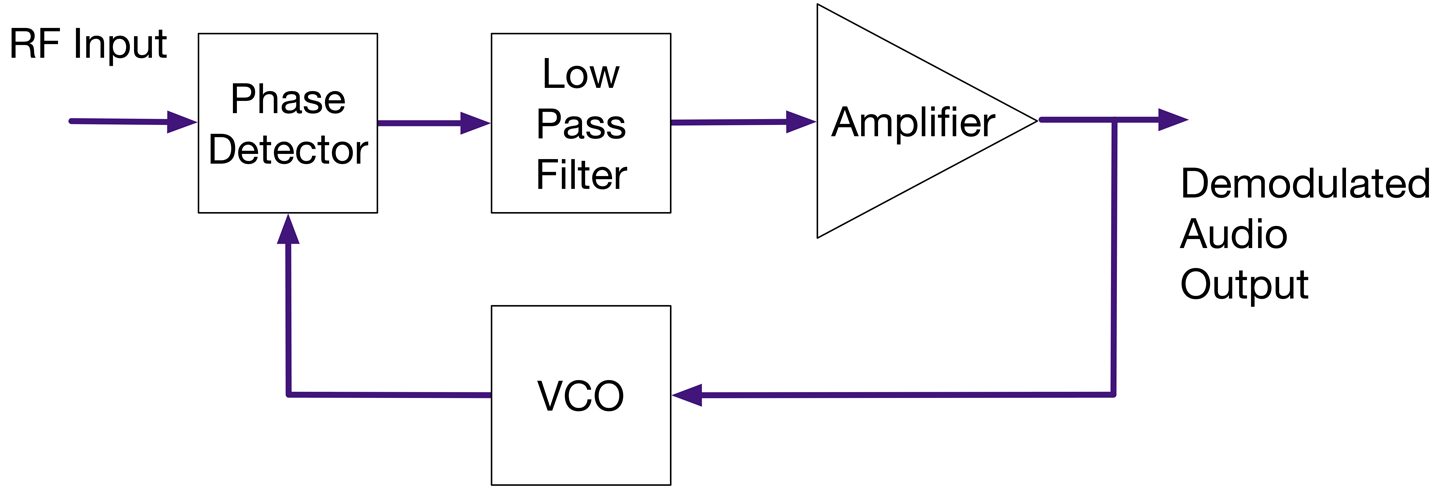

The first diodes to be used in electronics were cat’s whisker detectors used in crystal radios. These comprised a crystal of a semiconductor material (often lead sulphide or silicon). The cat’s whisker is simply a bare wire that is held in an adjustable bracket that touches the semiconductor crystal. By carefully moving the whisker around, at certain points of contact the arrangement would act as a diode, only allowing current to flow in one direction. This property is needed in a simple radio receiver to detect the radio signal so that it can be heard (see Chapter 19).

Today diodes are much easier to use and come in all sorts of shapes and sizes.

A diode is a component that only allows current to flow through it in one direction. It’s a kind of one-way valve if you want to think of it in terms of water running through pipes, which of course is a simplification. In reality the diode offers very low resistance in one direction and very high resistance in the other. In other words, the one-way valve restricts the flow a tiny bit when open and also leaks slightly when closed. But most of the time, thinking of a diode as a one-way valve for electrical current works just fine.

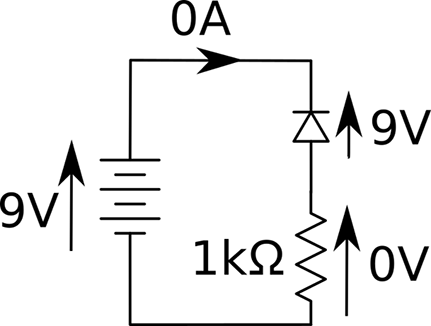

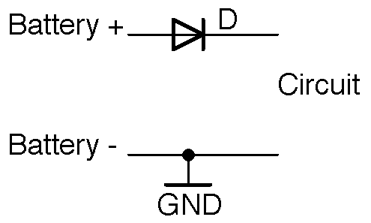

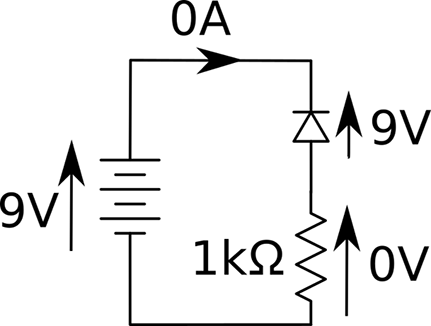

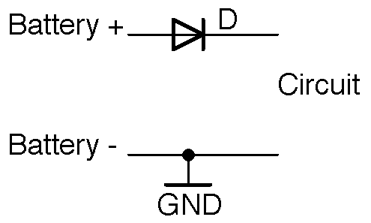

There are lots of specialized types of diodes, but let’s start with the most common and basic diode, the rectifier diode. Figure 4-1 shows such a diode in a circuit with a battery and resistor.

In this case, the diode allows flow of current and is considered forward-biased. The two leads of the diode are called the anode (abbreviated as “a”) and cathode (abbreviated rather confusingly as “k”). For a diode to be forward-biased, the anode needs to be at a higher voltage than the cathode, as shown in Figure 4-1.

One interesting property of a forward-biased diode is that unlike a resistor, the voltage across it does not vary in proportion to the current flowing through it. Instead, the voltage remains almost constant, no matter how much current flows through it. This varies depending on the type of diode, but is generally about 0.5V.

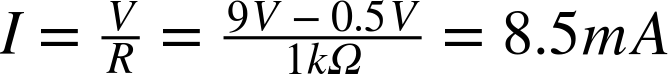

In the case of Figure 4-1, we can calculate that the current flowing through the resistor will be:

This is only 0.5mA less than if the diode were to be replaced with wire.

In Figure 4-2 the diode is facing the other direction. It is reverse-biased and consequently almost no current will flow through the resistor.

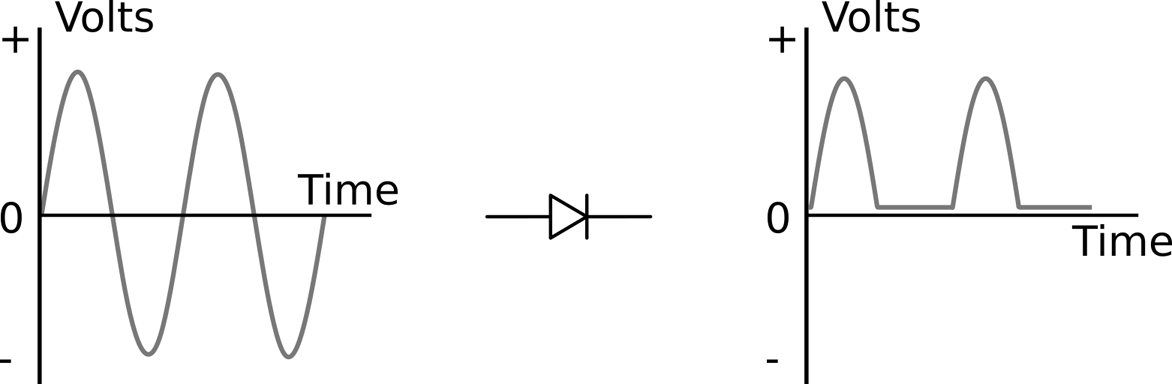

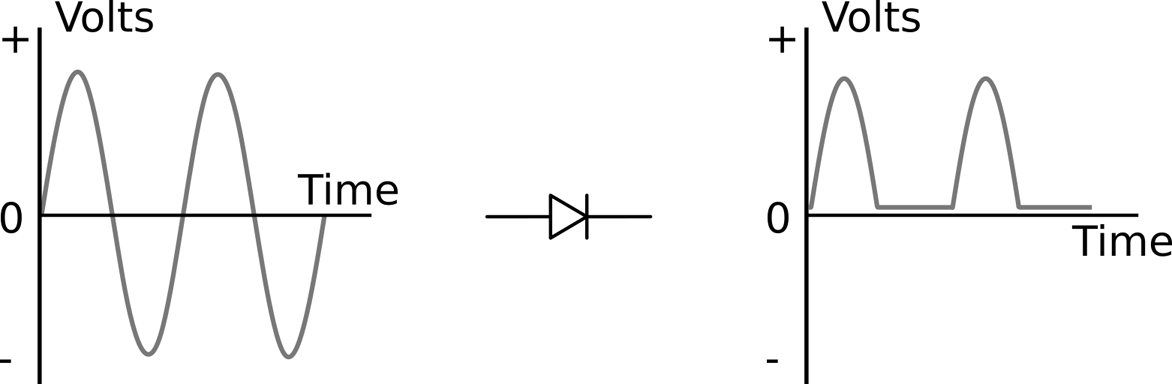

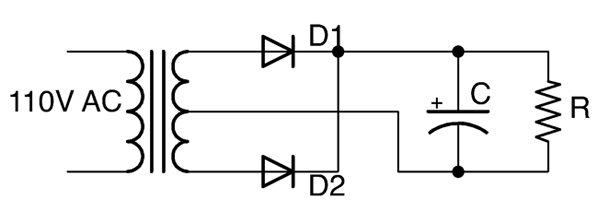

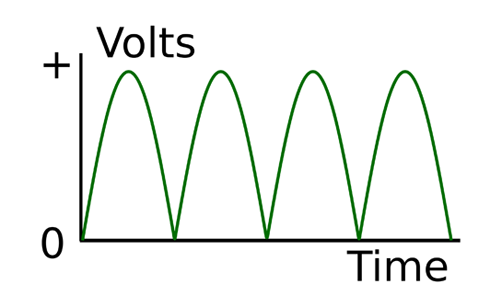

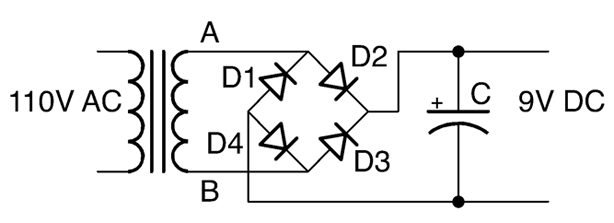

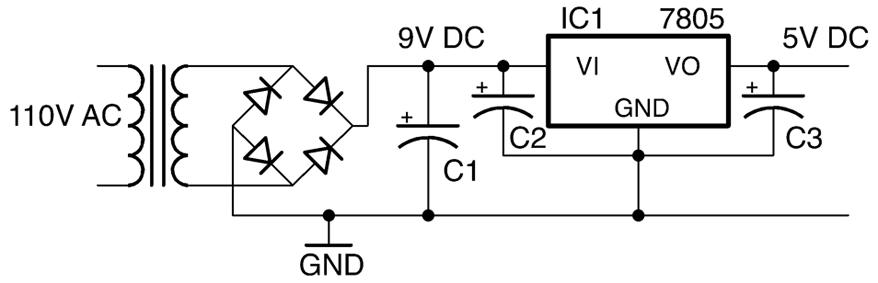

The diode’s one-way effect can be used to convert AC (Recipe 1.7) into DC. Figure 4-3 shows the effect of a diode on an AC voltage source.

This effect is called rectification (see Recipe 7.2). The negative part of the cycle is unused. This still isn’t true DC because even though the voltage never becomes negative it still swings from 0V up to a maximum and back down rather than remain constant. The next stage would be to add a capacitor in parallel with the load resistor that would smooth out the signal to a flat and almost constant DC voltage.

For information on using diodes in power supplies, see Recipe 7.2 and Recipe 7.3.

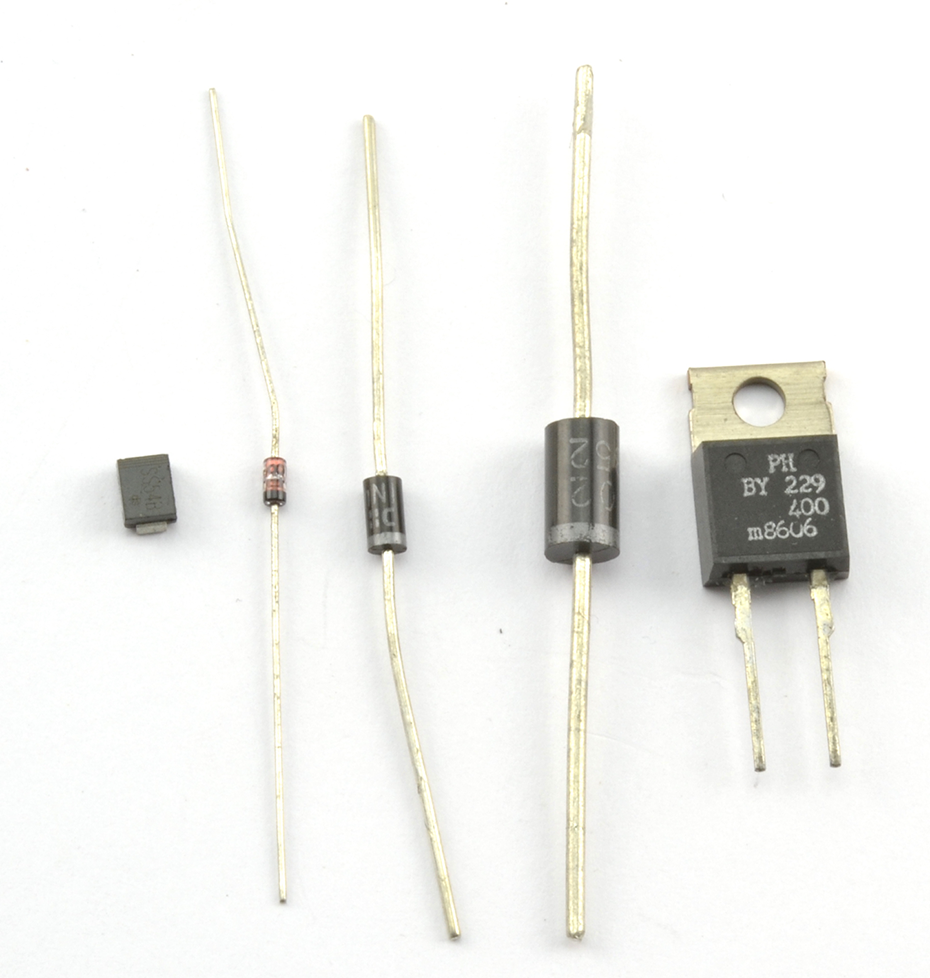

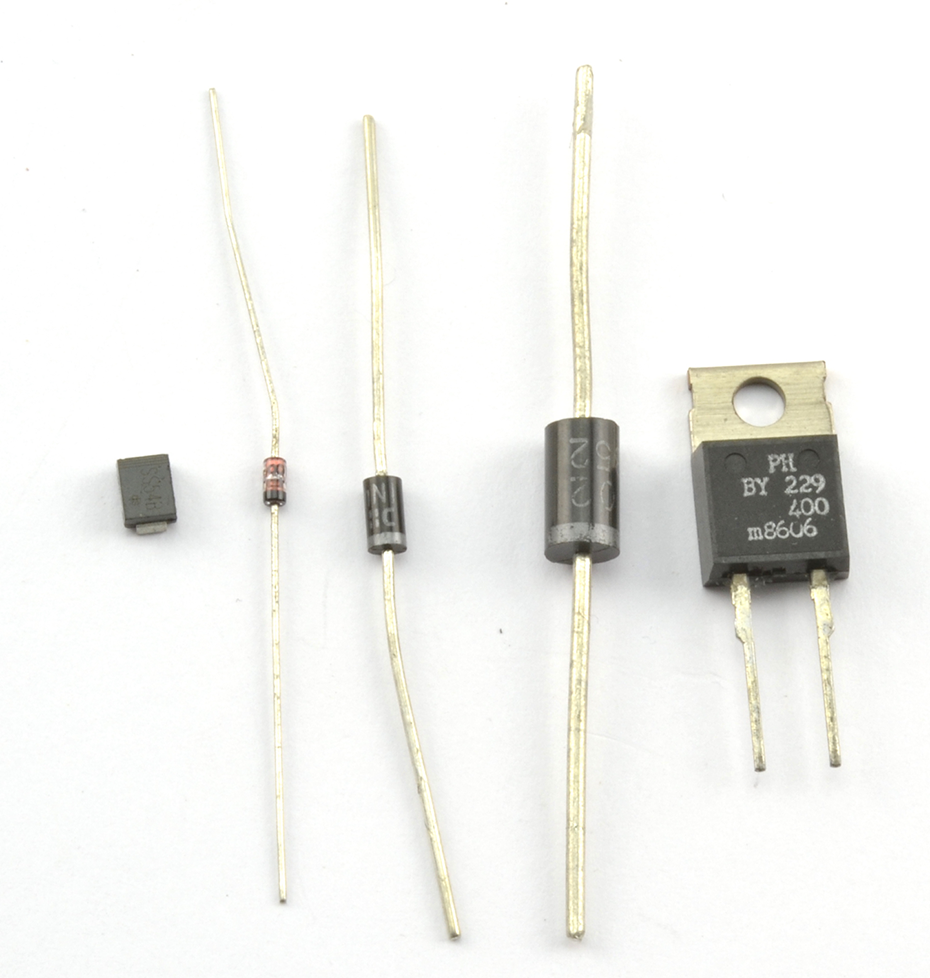

Figure 4-4 shows different types of diodes. Generally, the bigger the diode package, the greater its power-handling capability. Most diodes are a black plastic cylinder with a line at one end that points to the cathode (the end that should be more negative for forward-biased operation).

The diode on the left of Figure 4-4 is an SMD. The through-hole diodes to the right get larger, the higher the current rating.

There are many different types of diodes. Unlike resistors that are bought as a particular value resistor (say, 1kΩ) diodes are identified by the manufacturer’s part number.

Some of the most commonly used rectifier diodes are listed in Table 4-1.

| Part Number | Typical Forward Voltage | Maximum Current | DC Blocking Voltage | Recovery Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1N4001 | 0.6V | 1A | 50V | 30µs |

| 1N4004 | 0.6V | 1A | 400V | 30µs |

| 1N4148 | 0.6V | 200mA | 100V | 4ns |

| 1N5819 | 0.3V | 1A | 40V | 10ns |

The forward voltage, often abbreviated as Vf, is the voltage across the diode when forward-biased. The DC-blocking voltage is the reverse-biased voltage that if exceeded may destroy the diode.

The recovery time of a diode refers to how quickly the diode can switch from forward-biased conducting to reverse-biased blocking. This is not instantaneous in any diode and in some applications fast switching is needed.

The 1N5819 diode is called a Schottky diode. These types of diodes have much lower forward voltage and generate less heat.

You can find the datasheet for the 1N4000 family of diodes here: http://bit.ly/2lOtD71.

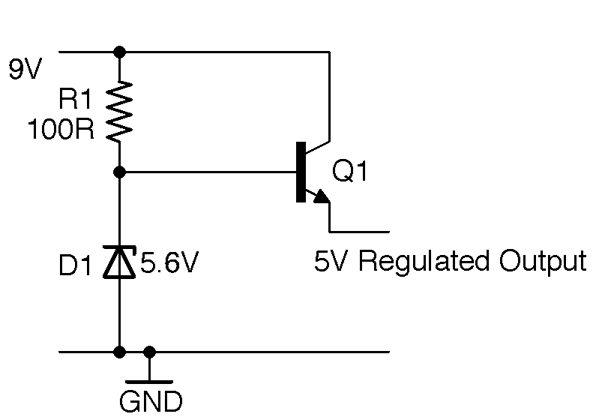

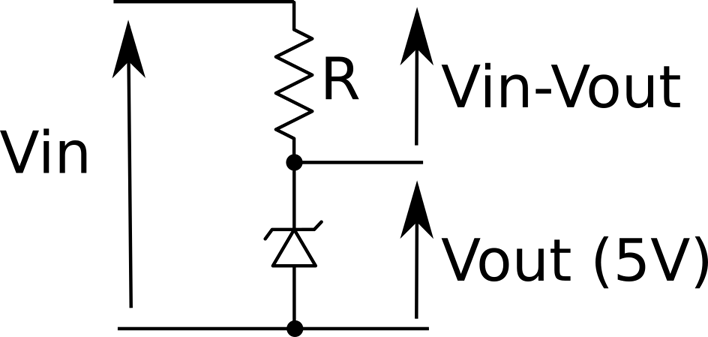

When forward-biased, Zener diodes behave just like regular diodes and conduct. At low voltages, when reverse-biased they have high resistance just like normal diodes. However, when the reverse-biased voltage exceeds a certain level (called the breakdown voltage), the diodes suddenly conduct as if they were forward-biased.

In fact, regular diodes do the same thing as Zener diodes but at a high voltage and not a voltage that is carefully controlled. The difference with a Zener diode is that the diode is deliberately designed for this breakdown to occur at a certain voltage (say, 5V) and for the Zener diode to be undamaged by such a “breakdown.”

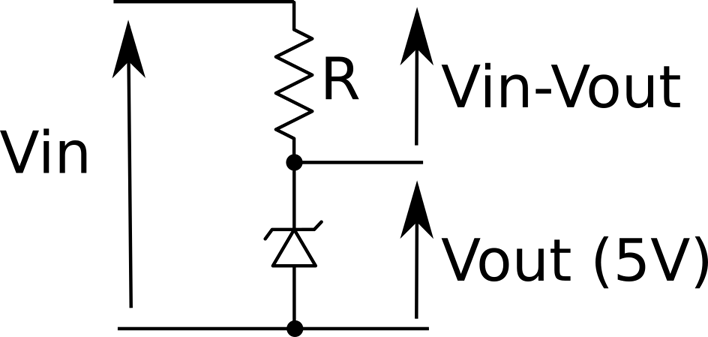

Zener diodes are useful for providing a reference voltage (see the schematic in Figure 4-5). Note the slightly different component symbol for a Zener diode with the little arms on the cathode.

The resistor R limits the current flowing through the Zener diode. This current is always assumed to be much greater than the current flowing into a load across the diode.

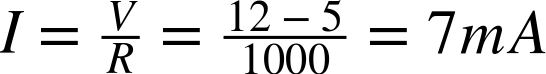

This circuit is only well suited to providing a voltage reference. A voltage reference provides a stable voltage but with hardly any load current; for example, when the circuit is used with a transistor as in Recipe 7.4. So a resistor value of, say, 1kΩ would, if Vin was 12V, allow a current of:

The output voltage will remain roughly 5V whatever Vin is as long as it’s greater than 5V. To understand how this happens, imagine that the voltage across the Zener diode is less than its 5V breakdown voltage. The Zener’s resistance will therefore be high and so the voltage across it due to the voltage divider effect of R and the Zener will be higher than the breakdown voltage. But wait, since the breakdown voltage is exceeded it will conduct, bringing the Vout down to 5V. If it falls below that, the diode will turn off and the Vout will increase again.

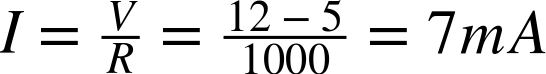

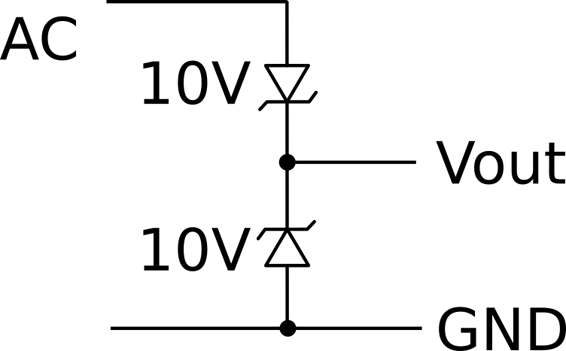

Zener diodes are also used to protect sensitive electronics from high-voltage spikes due to static discharge or incorrectly connected equipment. Figure 4-6 shows how an input to an amplifier not expected to exceed ±10V can be protected from both high positive and negative voltages. When the input voltage is within the allowed range the Zener will be high resistance and not interfere with the input signal, but as soon as the voltage is exceeded in either direction the Zener will conduct the excess voltage to ground.

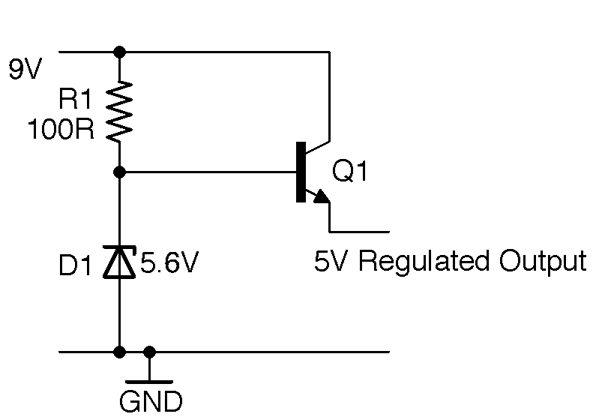

Although you would generally use a voltage-regulator IC (see Recipe 7.4), you can use a Zener diode combined with a transistor to act as a voltage regulator.

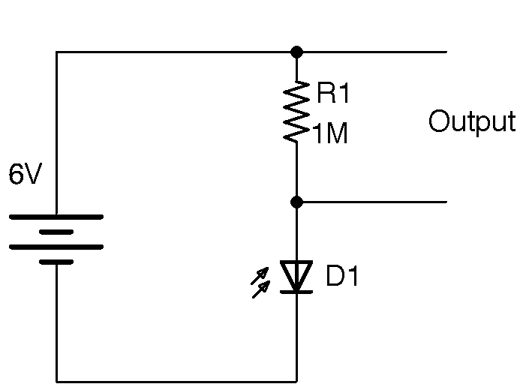

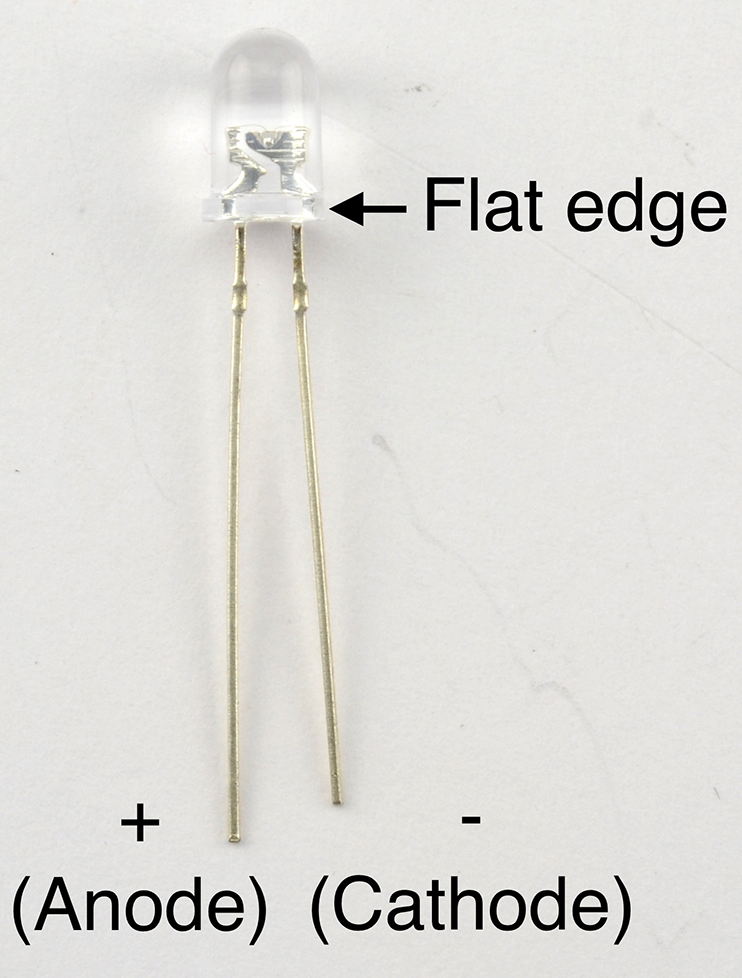

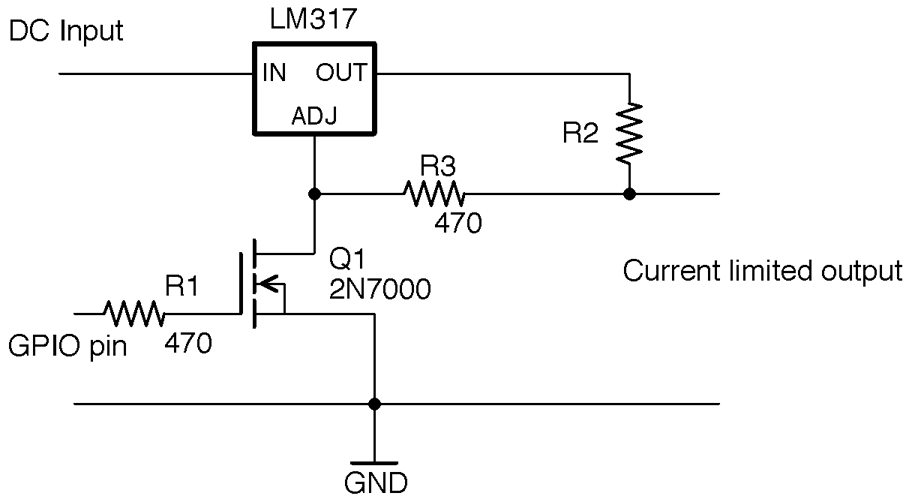

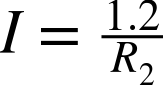

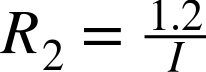

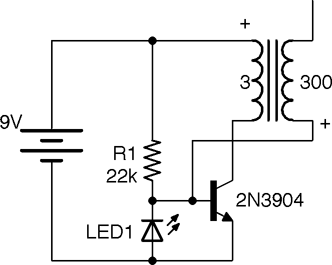

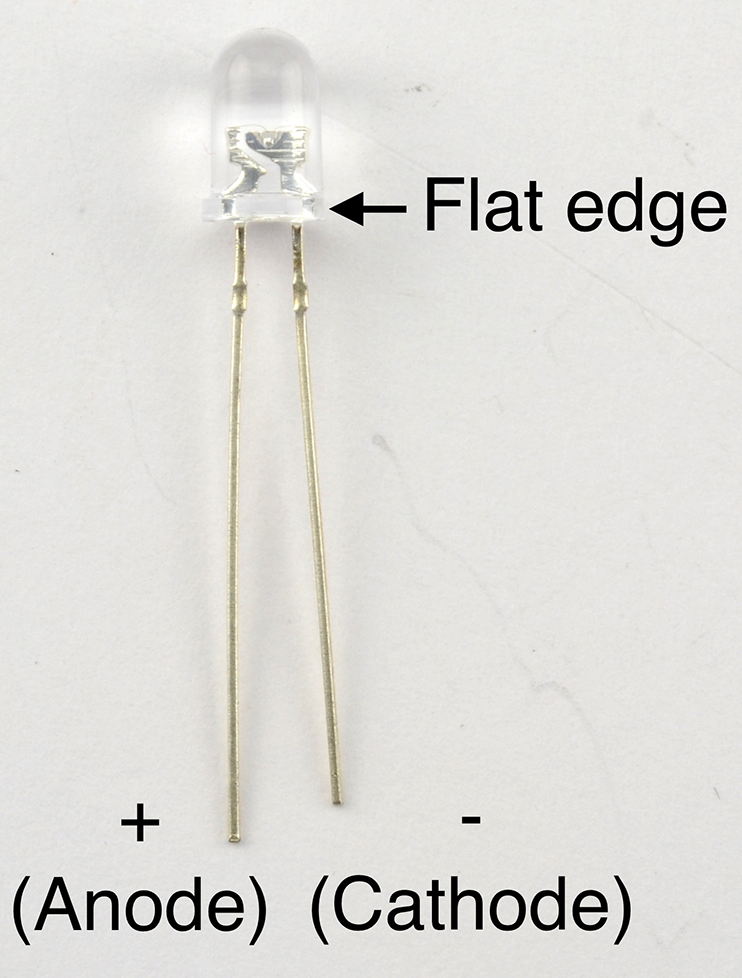

LEDs are like regular diodes in that when reverse-biased they block the flow of current, but when forward-biased they emit light.

The forward voltage of an LED is more than the usual 0.5V of a rectifier and depends on the color of the LED. Generally a standard red LED will have a forward voltage of about 1.6V.

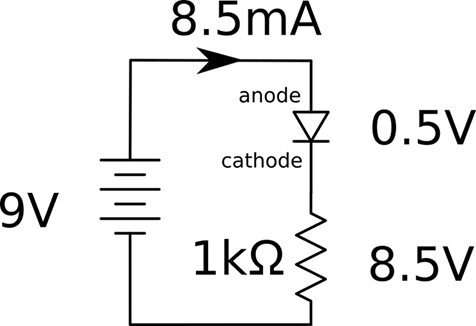

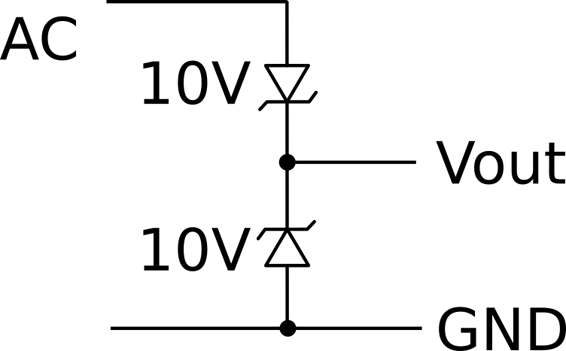

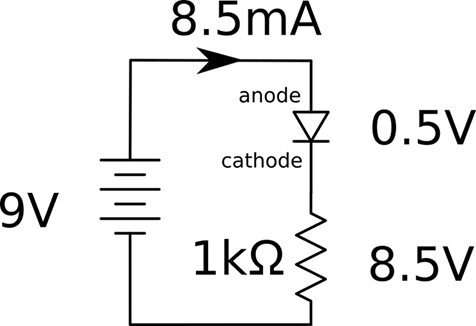

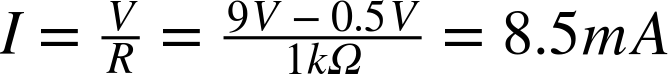

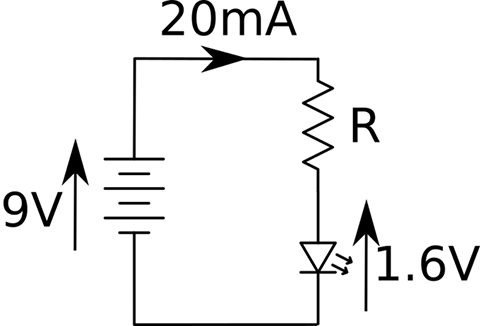

Figure 4-7 shows an LED in series with a resistor. The resistor is necessary to prevent too much current from flowing through the LED and damaging it.

An LED used as an illuminator will generally emit some light at 1mA but usually needs about 20mA for optimum brightness. The LED’s datasheet will tell you its optimal and maximum forward currents.

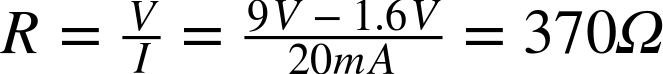

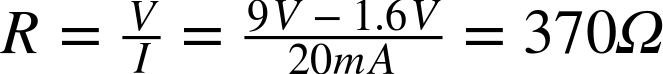

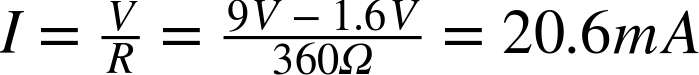

As an example, if in Figure 6-5 the voltage source is a 9V battery and the LED has a forward voltage of 1.6V, you can calculate the resistor value needed using Ohm’s Law:

370Ω is not a common resistor value (see Recipe 2.2) so you could pick a 360Ω resistor, in which case the current would be:

which would be just fine.

Finding suitable resistor values for LEDs to limit the current is such a common task that there is really no need to go through these calculations all the time. In Recipe 14.1 you will find a practical recipe for rule-of-thumb selection of current-limiting resistors.

For information on driving different types of LED, see Chapter 14.

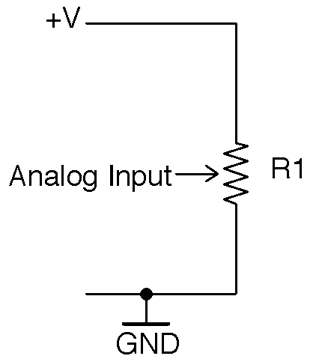

Use a photodiode. You can also use a photoresistor (Recipe 2.8) or a phototransistor (Recipe 5.7).

A photodiode is a diode that is sensitive to light. A photodiode usually has a transparent window, but photodiodes designed for infrared use have a black plastic case. The black plastic case is transparent to IR and usefully stops the photodiode from being sensitive to visible light.

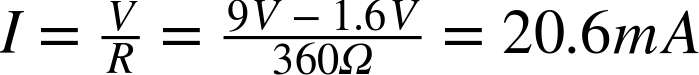

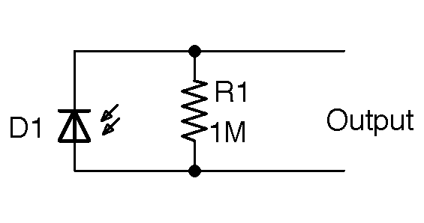

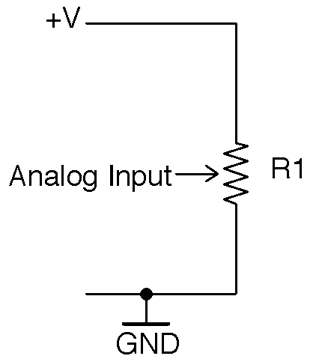

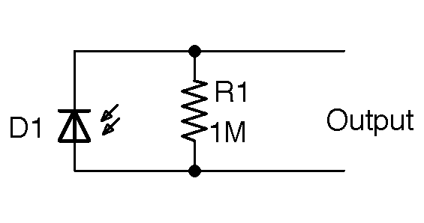

Photodiodes can be treated as little tiny photovoltaic solar cells. When illuminated they generate a small current. Figure 4-8 shows how you can use a photodiode with a resistor to produce a small voltage that you could then use in your circuits.

In this circuit, the voltage when illuminated brightly might only be 100mV.

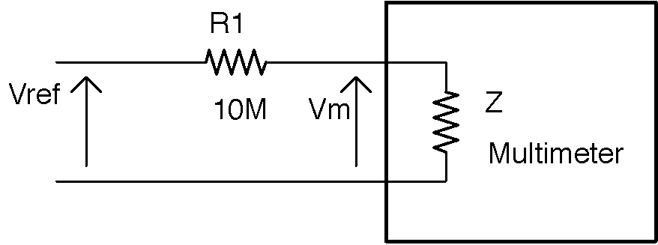

The resistor is necessary so that the small current from the photodiode is converted into a voltage (V=IR). Otherwise, any voltage that you measure will be depend on the resistance (called impedance when not from a resistor) of whatever is measuring the voltage. So, for example, a multimeter with an input impedance of 10MΩ would provide a completely different (and lower) reading than a multimeter with a 100MΩ input impedance.

R1 makes the voltage consistent. The impedance of whatever is connected to the output needs to be much higher in value than R1. If this is an op-amp (see Chapter 17) then the input impedance is likely to be hundreds of MΩ and so will not alter the output voltage appreciably. The smaller you make R1, the lower the output voltage will be, so it’s a matter of striking a balance.

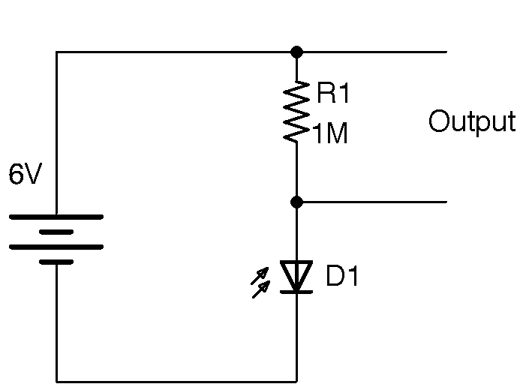

Better sensitivity can be achieved by using the photodiode in a photoconductive mode with a voltage source (Figure 4-9).

Photoresistors (Recipe 12.6) and phototransistors (Recipe 5.7) tend to be used more than photodiodes as they are more sensitive.

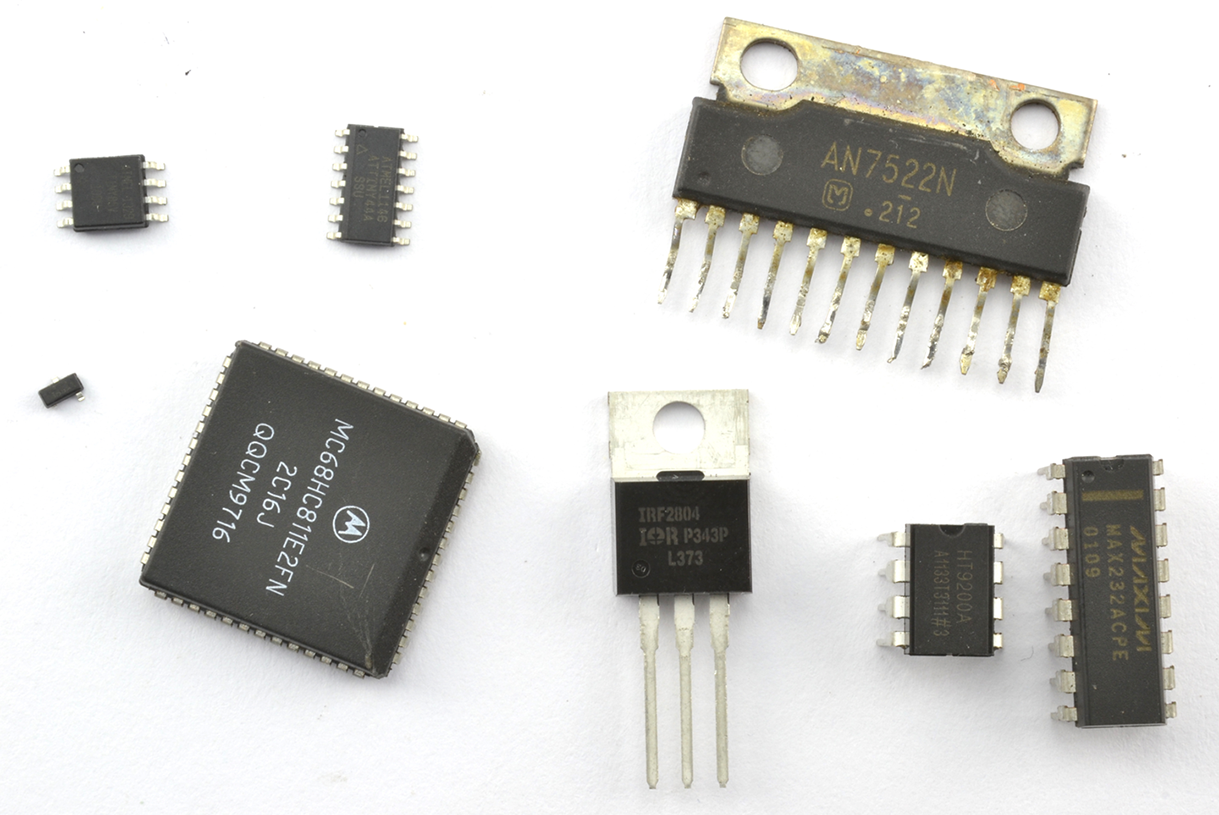

Transistors are used to control the flow of a current. In digital electronics this control takes the form of an on/off action, with the transistor acting as an electronic switch.

Transistors are also used in analog electronics where they can be used to amplify signals in a linear manner. However, these days, a better (cheaper and more reliable) way to do this is to use an integrated circuit (chip) that combines lots of transistors and other components into a single convenient package.

This chapter does not cover all types of transistors or semiconductor devices, but instead focuses on the most common ones, which are generally low in cost and easy to use. There are other exotic devices like the unijunction transistors and SCRs (silicon-controlled rectifiers) that used to be popular, but are now seldom used.

The other thing deliberately left out of this cookbook is the usual theory of how semiconductors like diodes and transistors work. If you are interested in the physics of electronics, there are many books and useful resources on semiconductor theory, but just to make use of transistors, you do not really need to know about holes, electrons, and doping N and P regions.

This chapter will concentrate on the use of transistors in their digital role. You will find information on using transistors for analog circuits in Chapter 16.

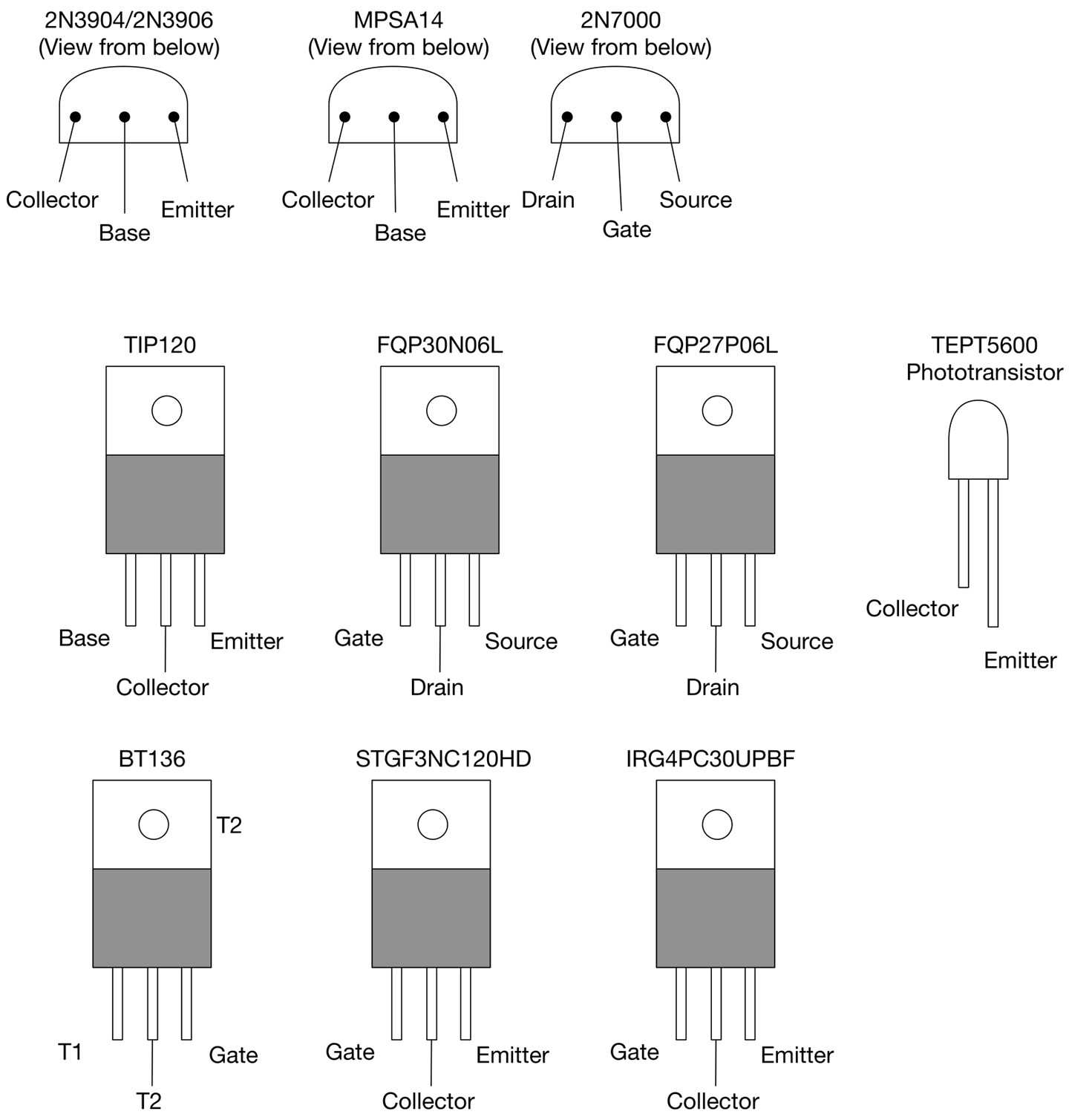

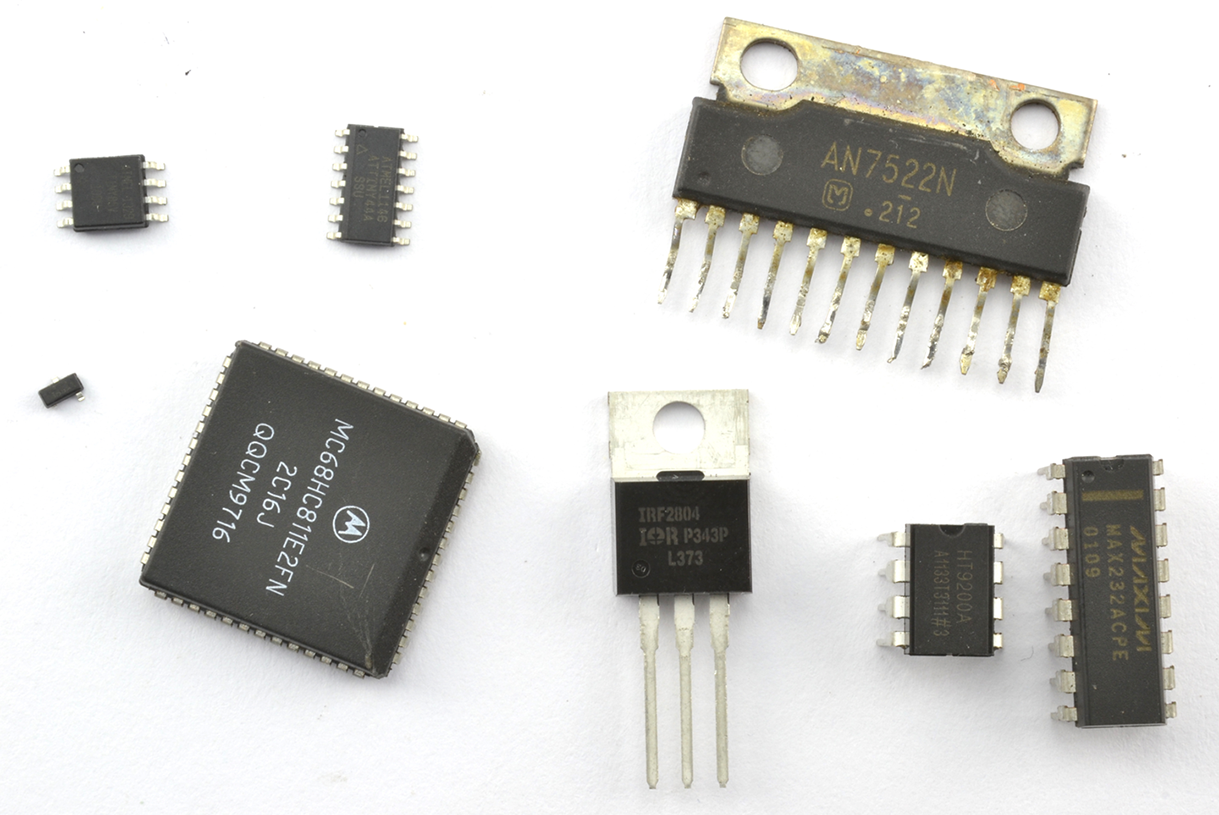

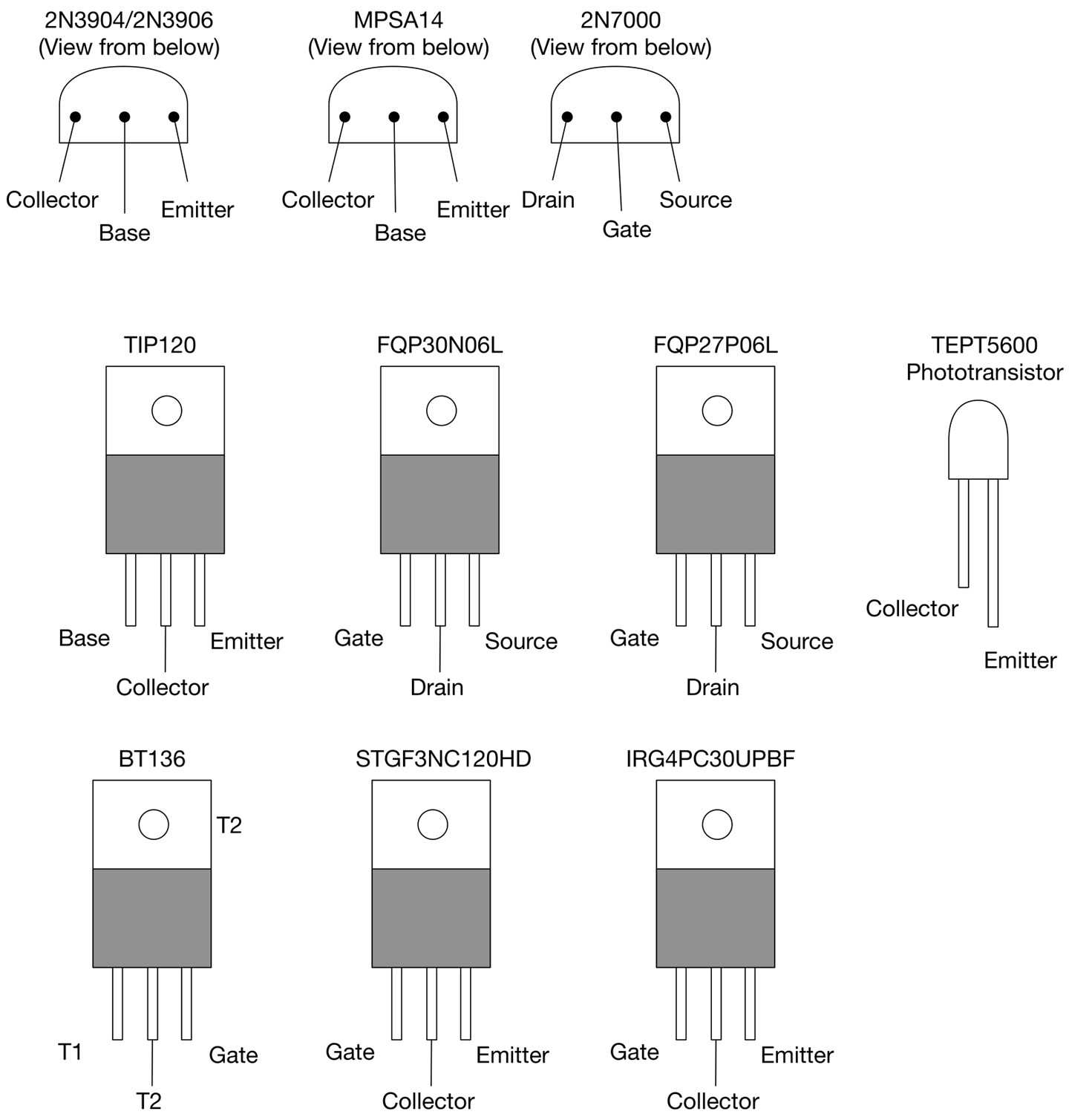

In this chapter, you will encounter a wide variety of transistors. Appendix A includes pinouts for the transistors used in this chapter and throughout the book.

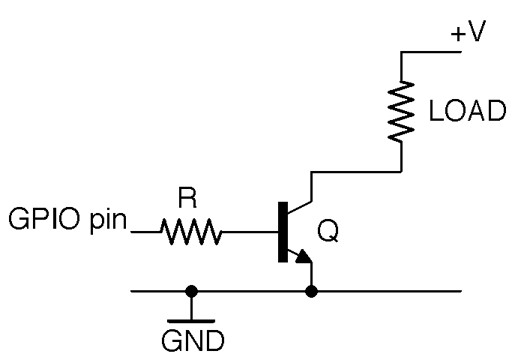

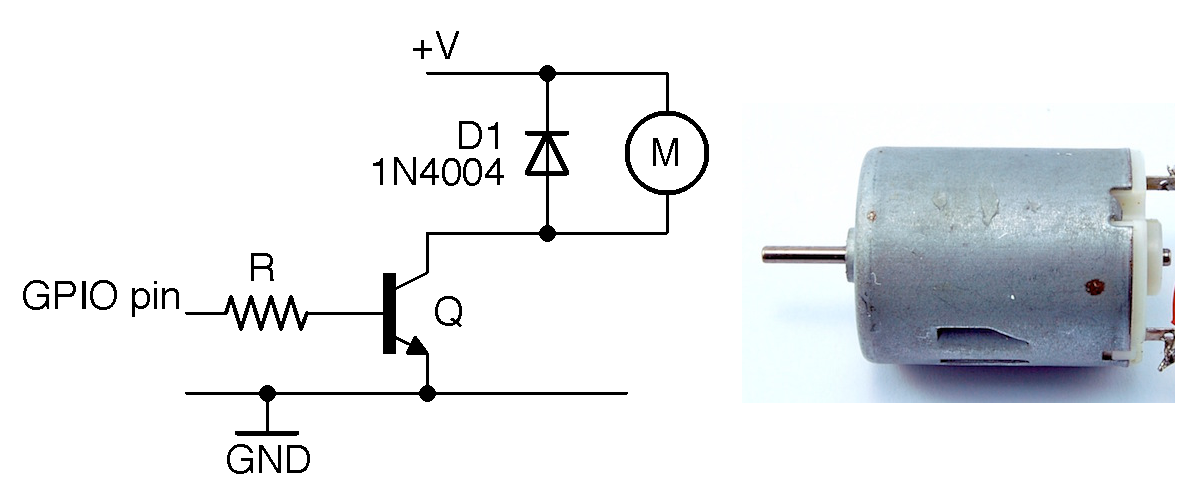

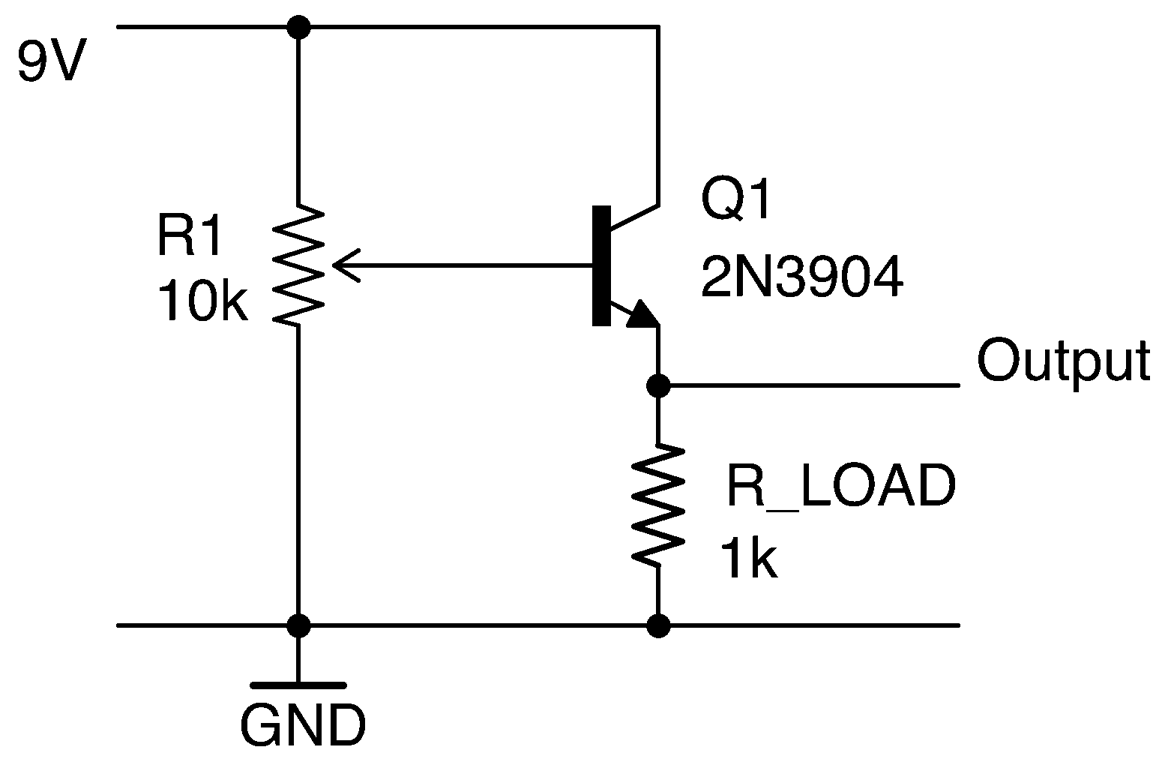

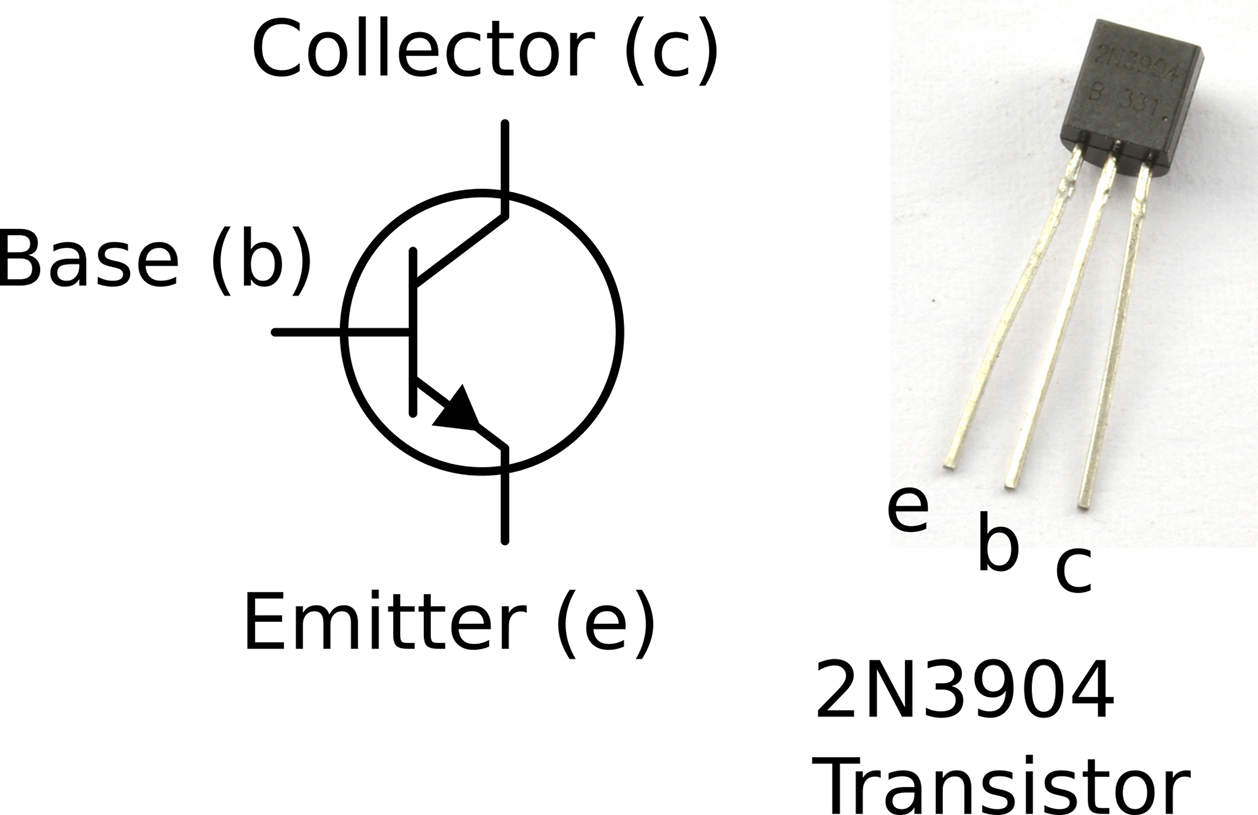

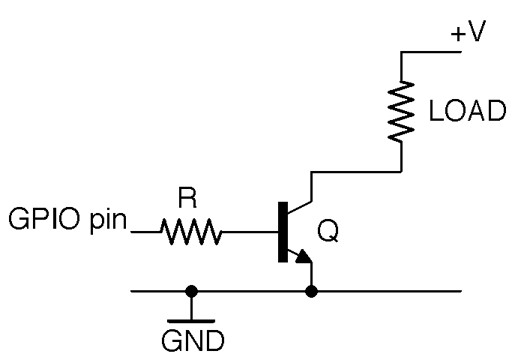

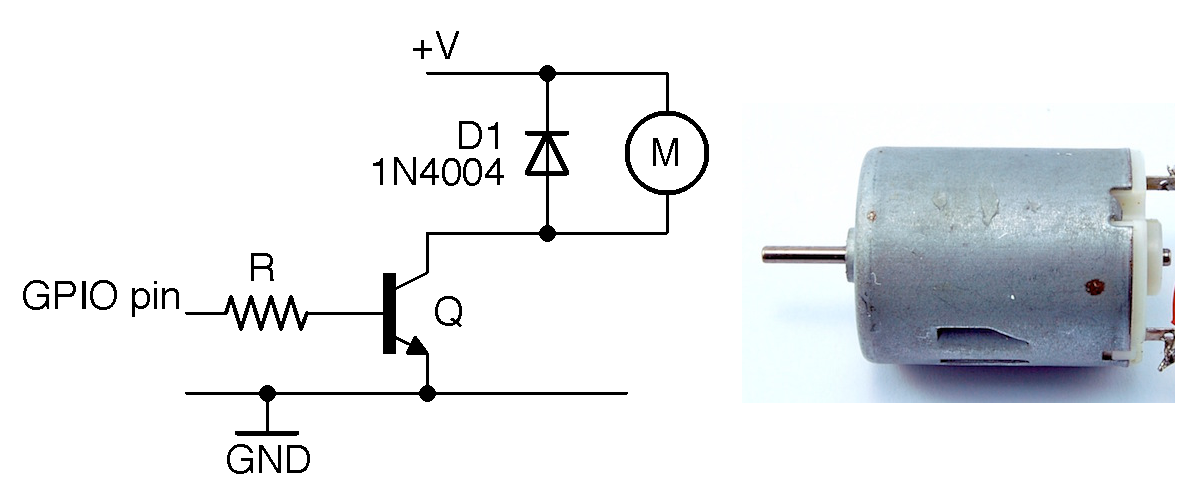

Use a low-cost bipolar junction transistor (BJT).

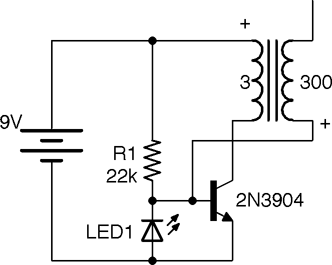

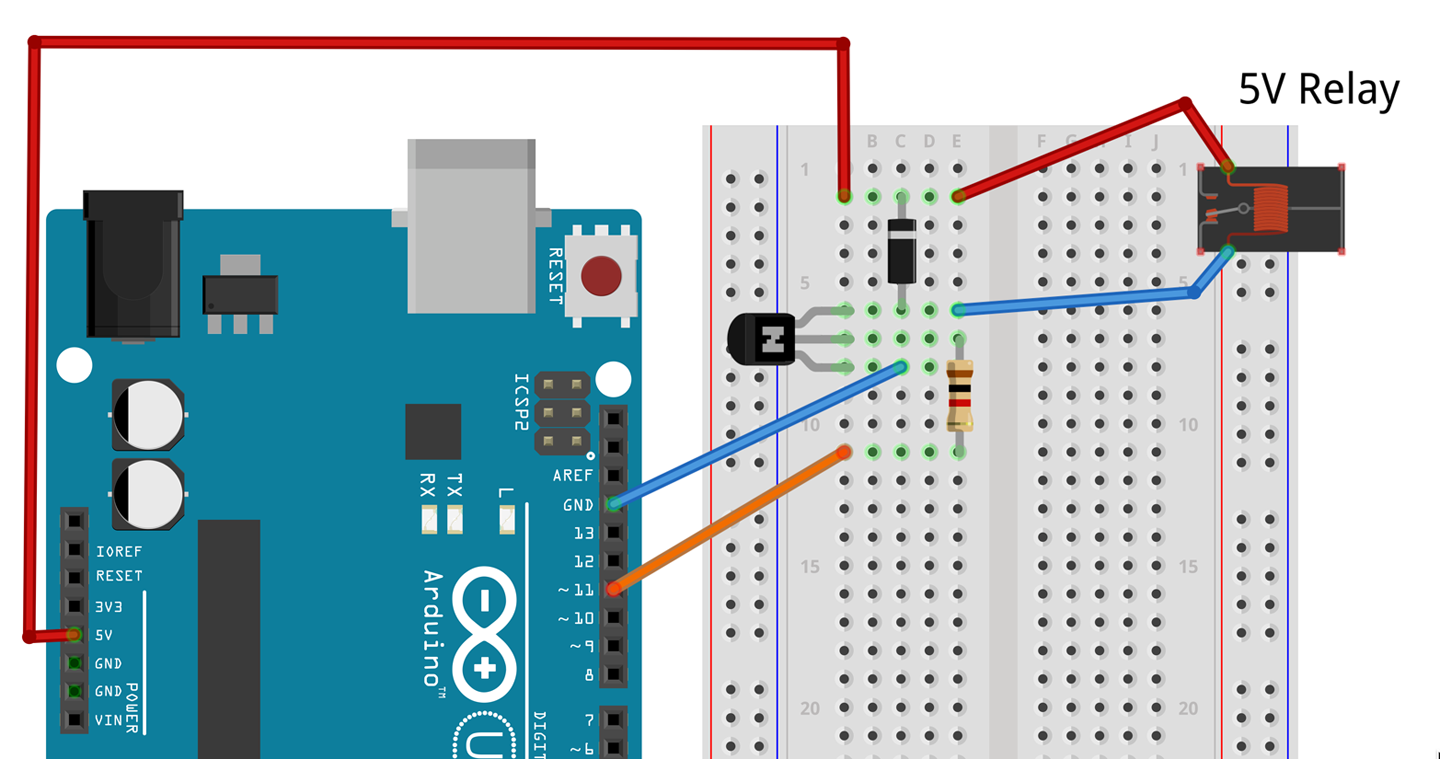

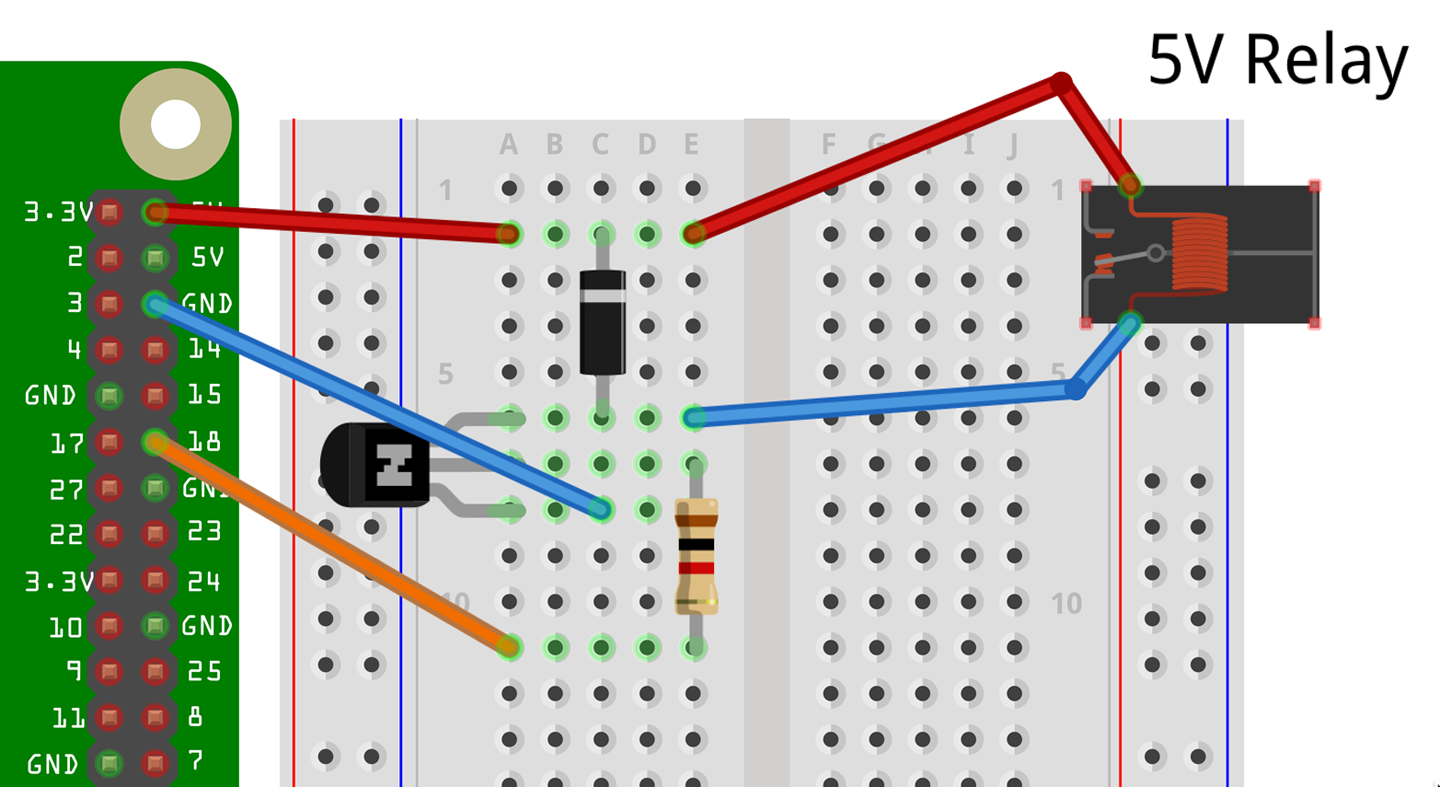

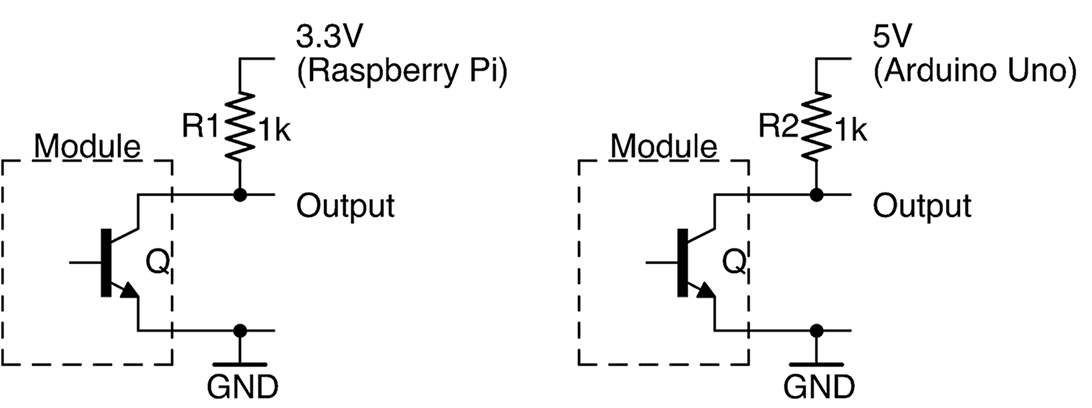

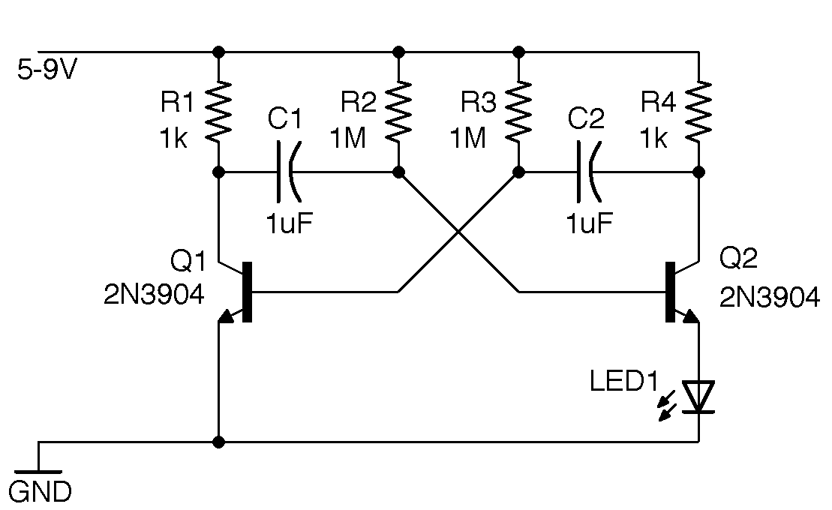

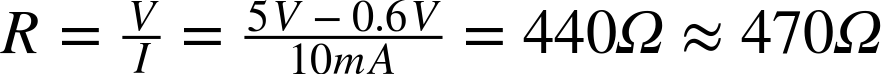

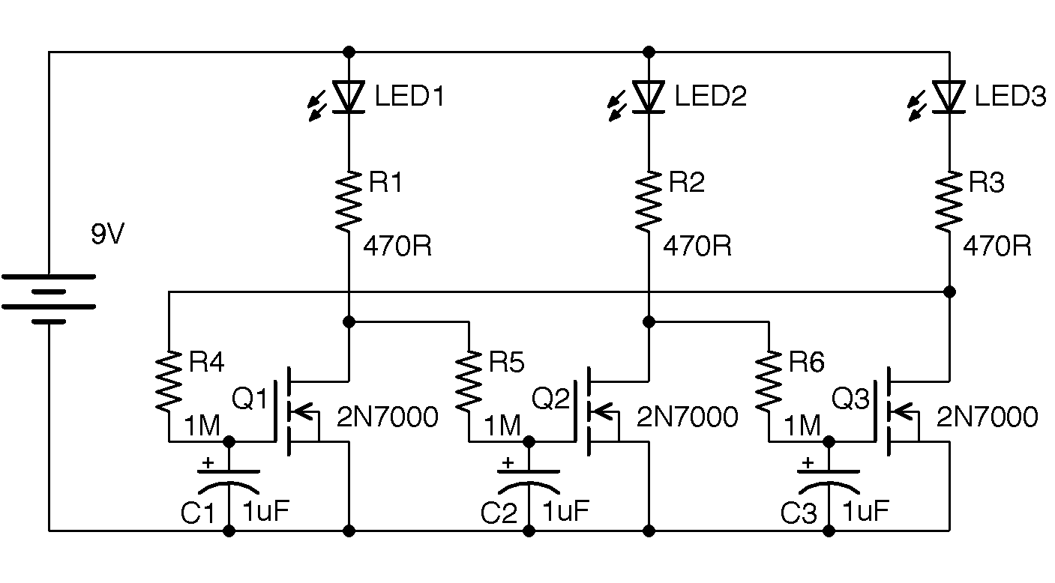

BJTs like the 2N3904 cost just a few cents and are often used with a microcontroller output pin from an Arduino or Raspberry Pi to increase the current the pin can control.

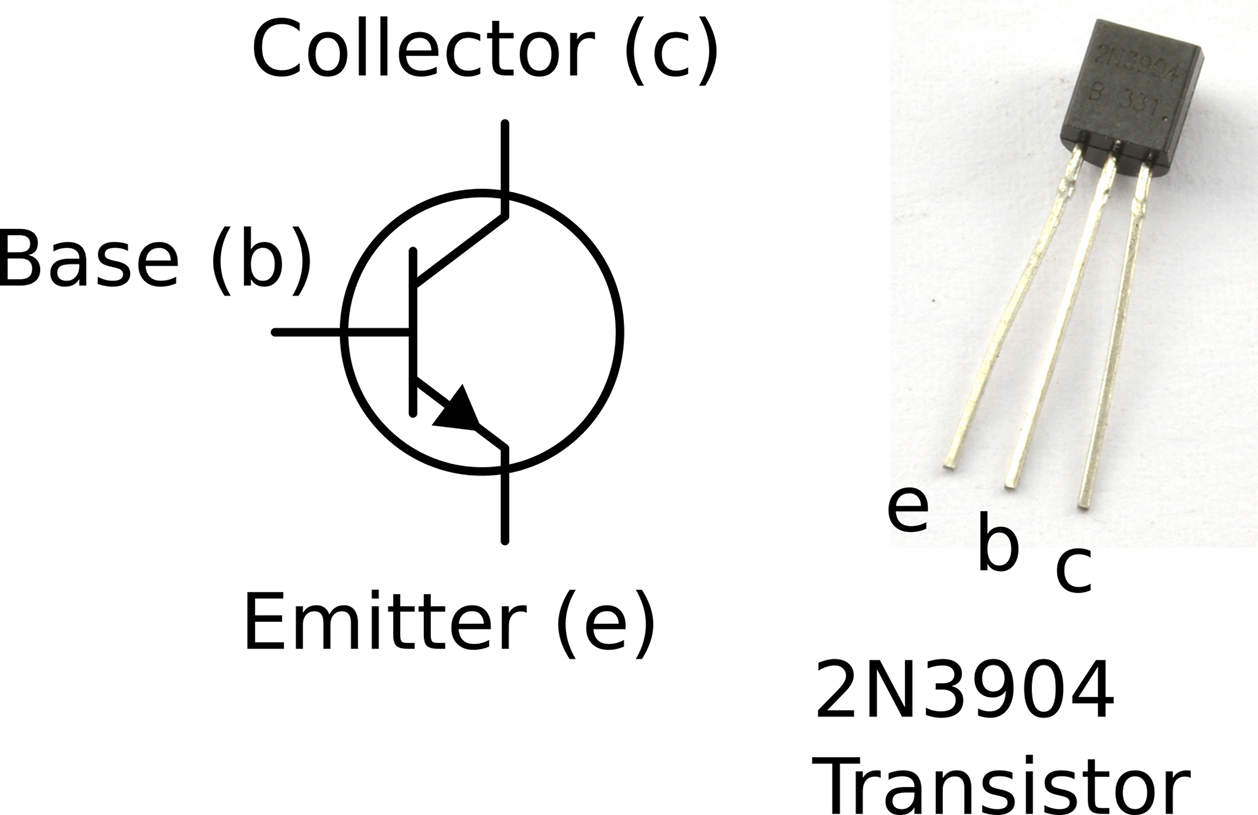

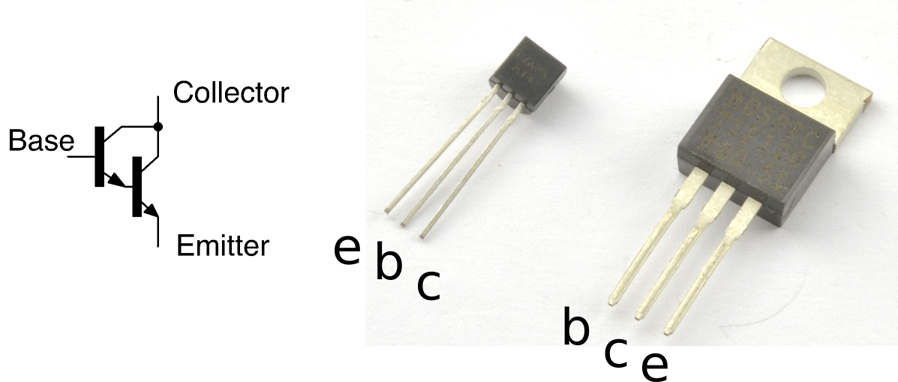

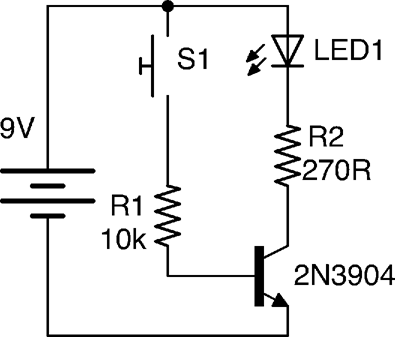

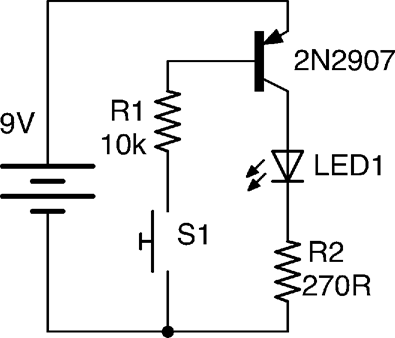

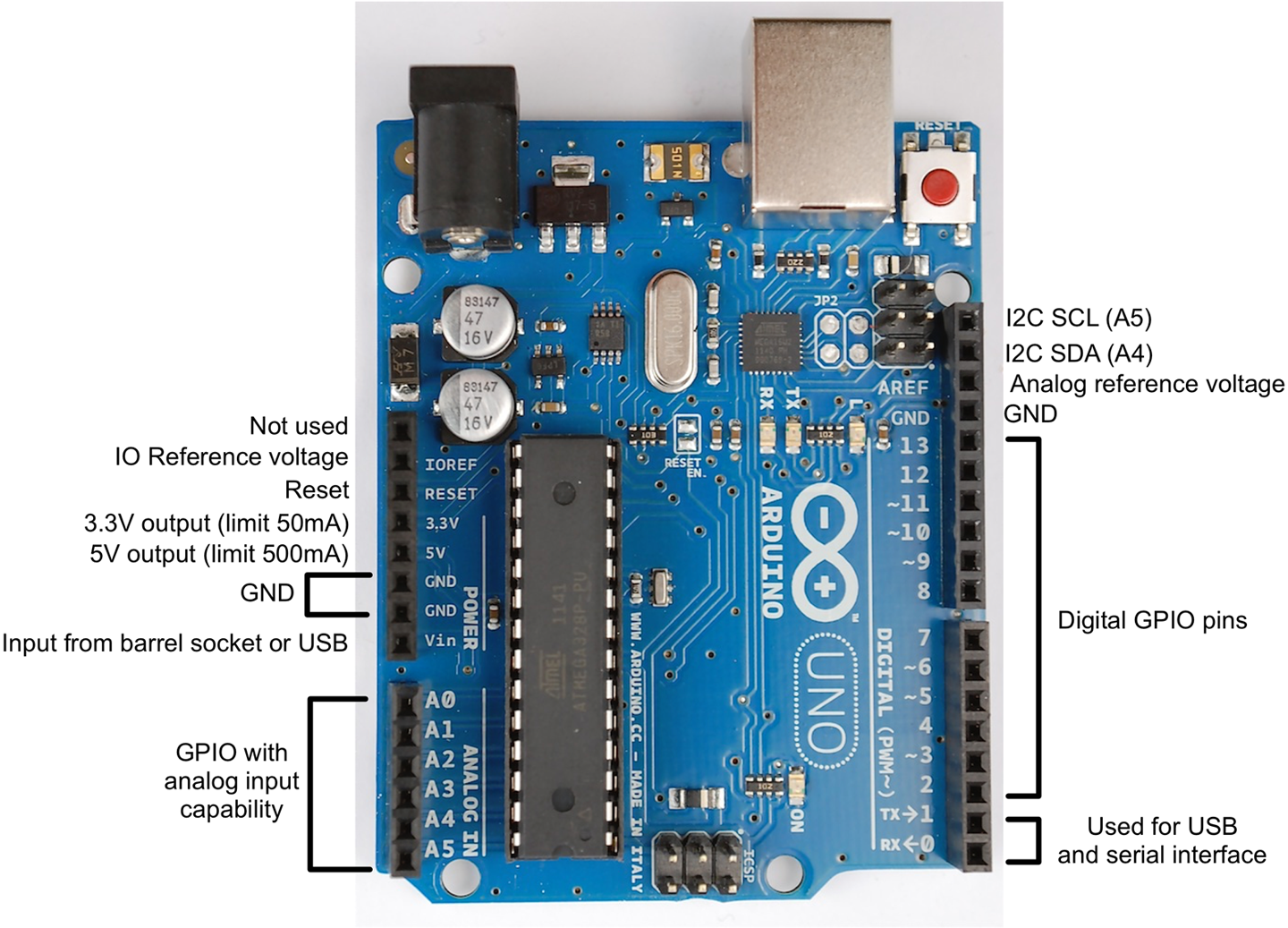

Figure 5-1 shows the schematic symbol for a BJT alongside one of the most popular models of this kind of transistor, the 2N3904. The 2N3904 is in a black plastic package called a TO-92 and you will find that many different low-power transistor models come supplied in the TO-92 package.

The transistor is usually shown with a circle around it, but sometimes just the symbol inside the circle is used.

The three connections to the transistor in Figure 5-1 are from top to bottom:

The main current flowing into the collector and out of the emitter is controlled by a much smaller current flowing into the base and out of the emitter. The ratio of the base current to the collector current is called the current gain of the transistor and is typically somewhere between 100 and 400. So for a transistor with a gain of 100, a 1mA current flowing from base to emitter will allow a current of up to 100mA to flow from collector to emitter.

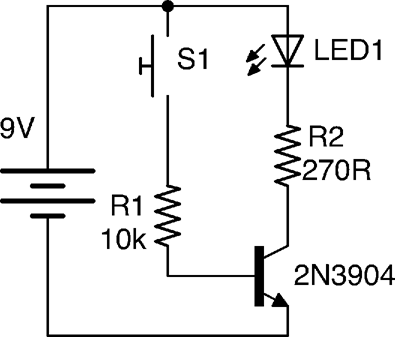

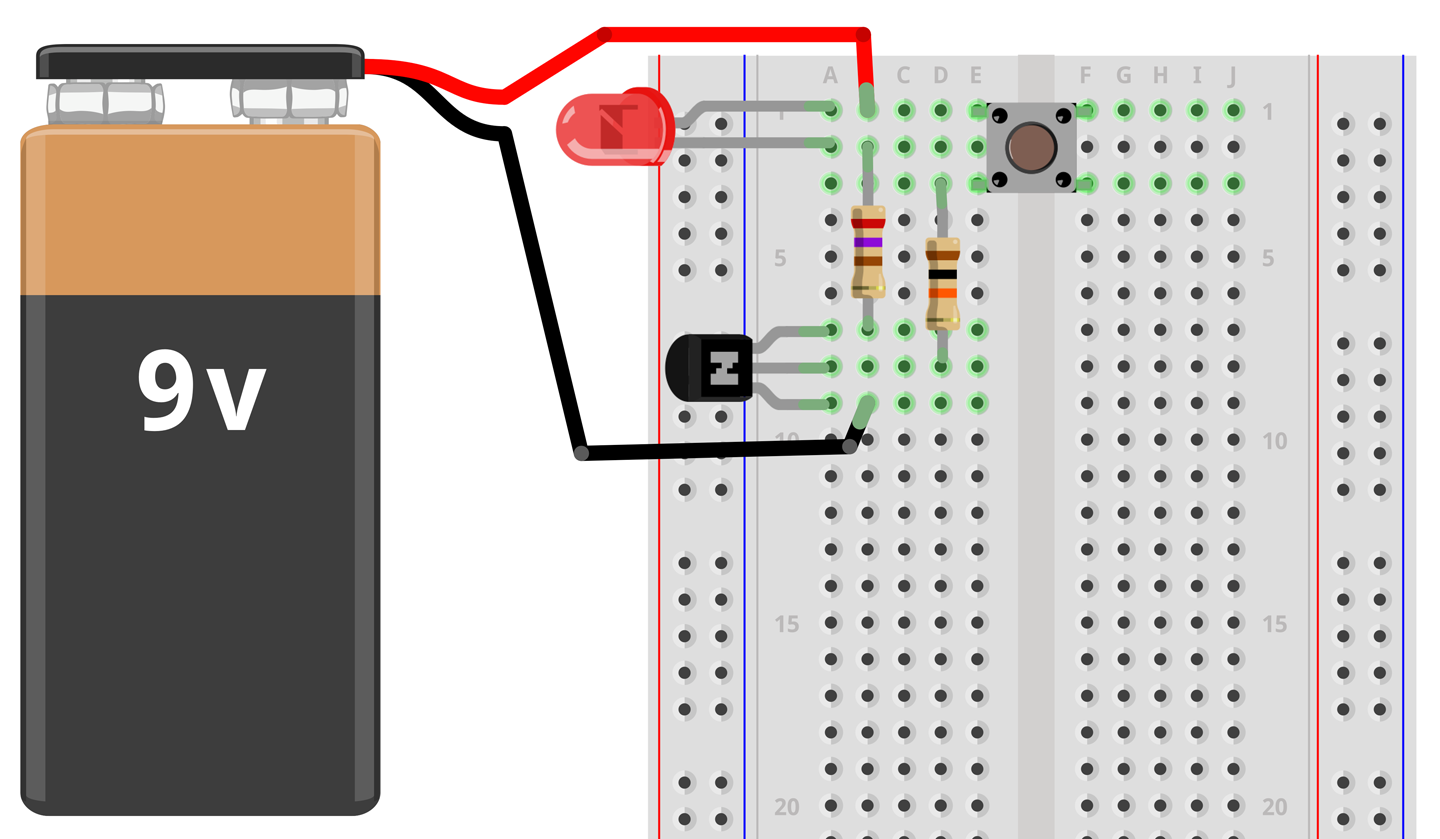

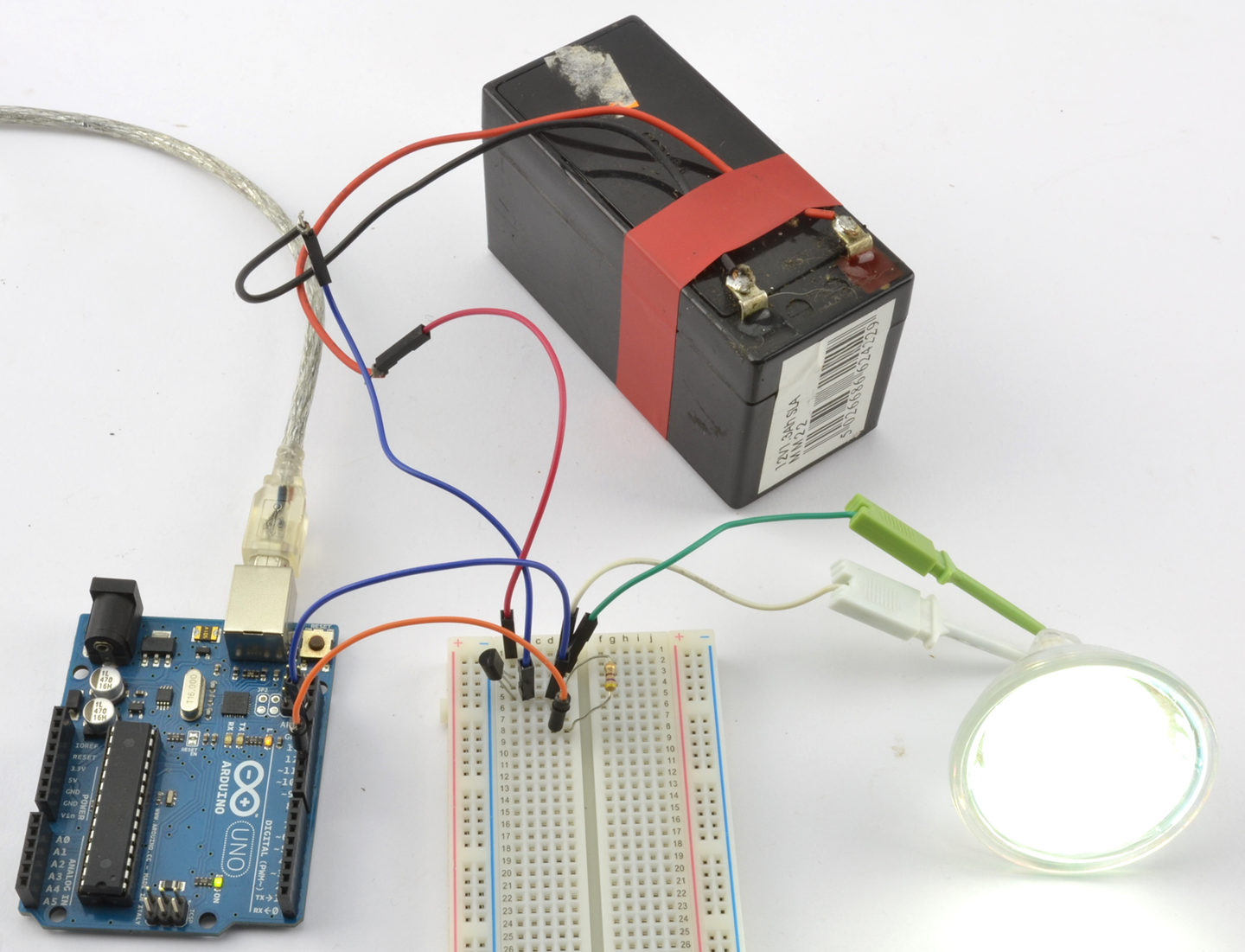

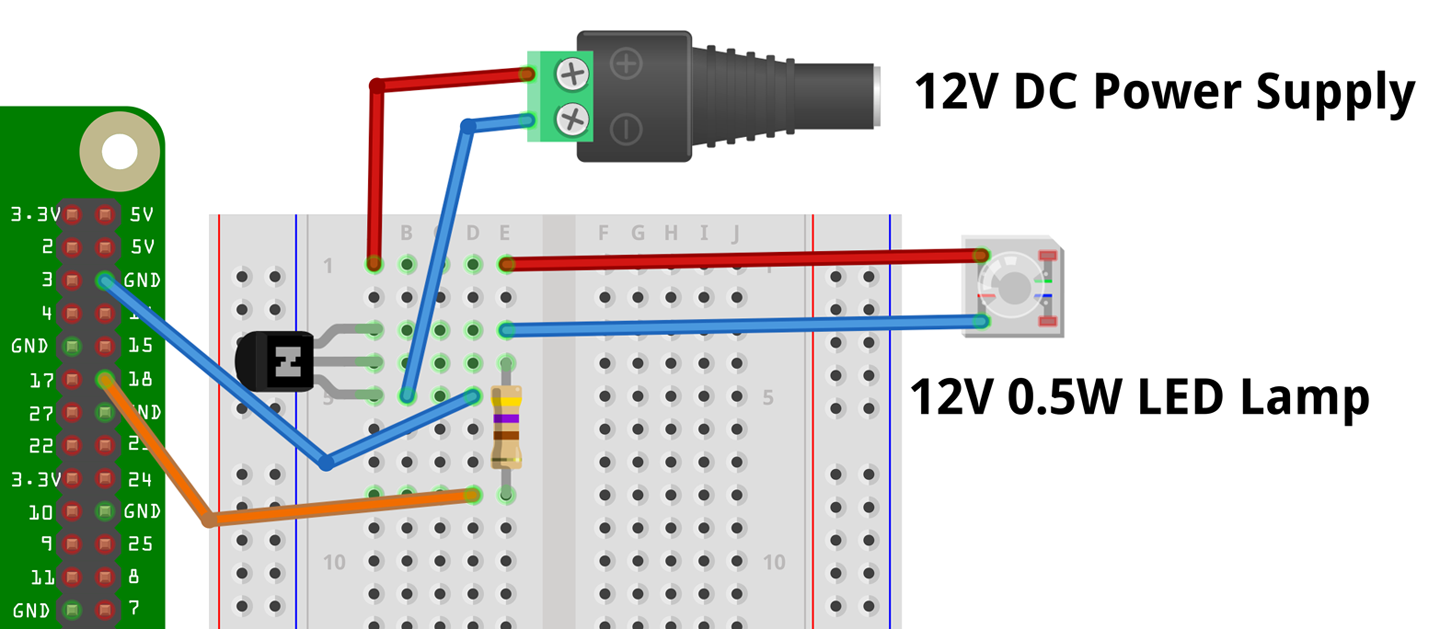

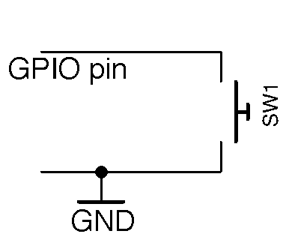

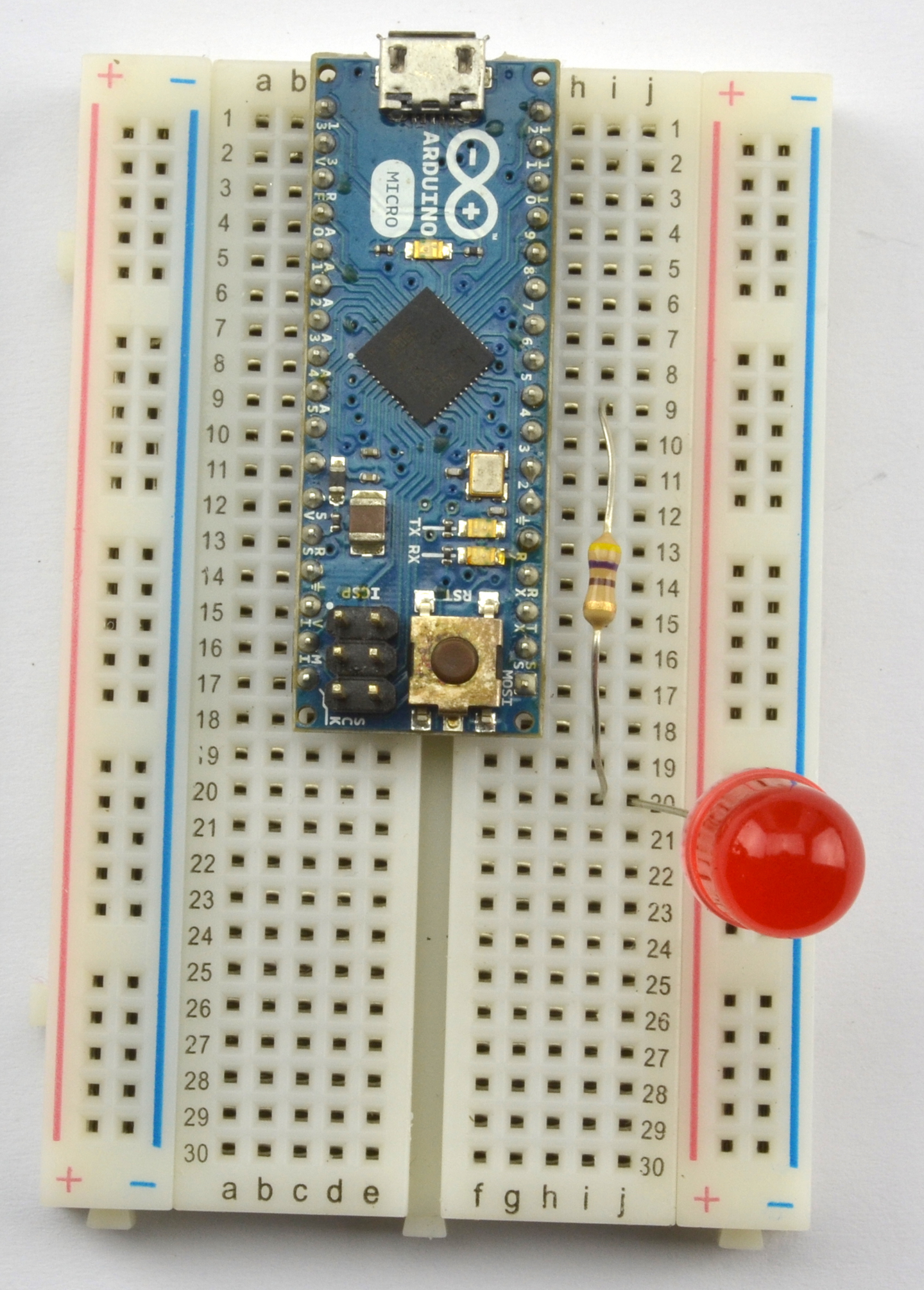

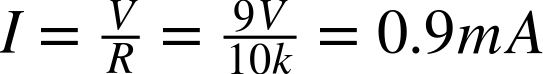

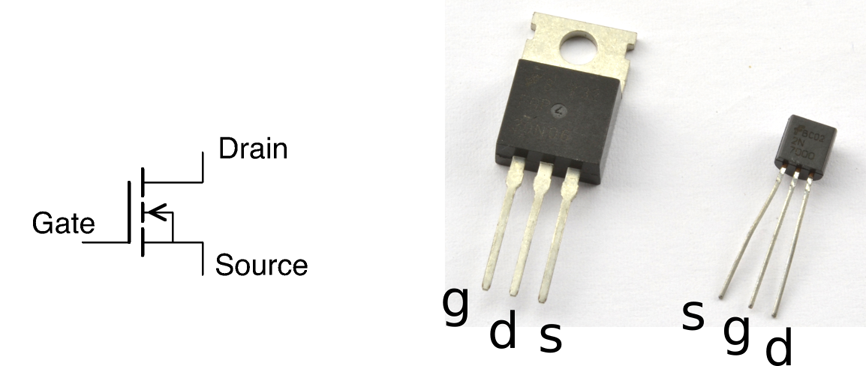

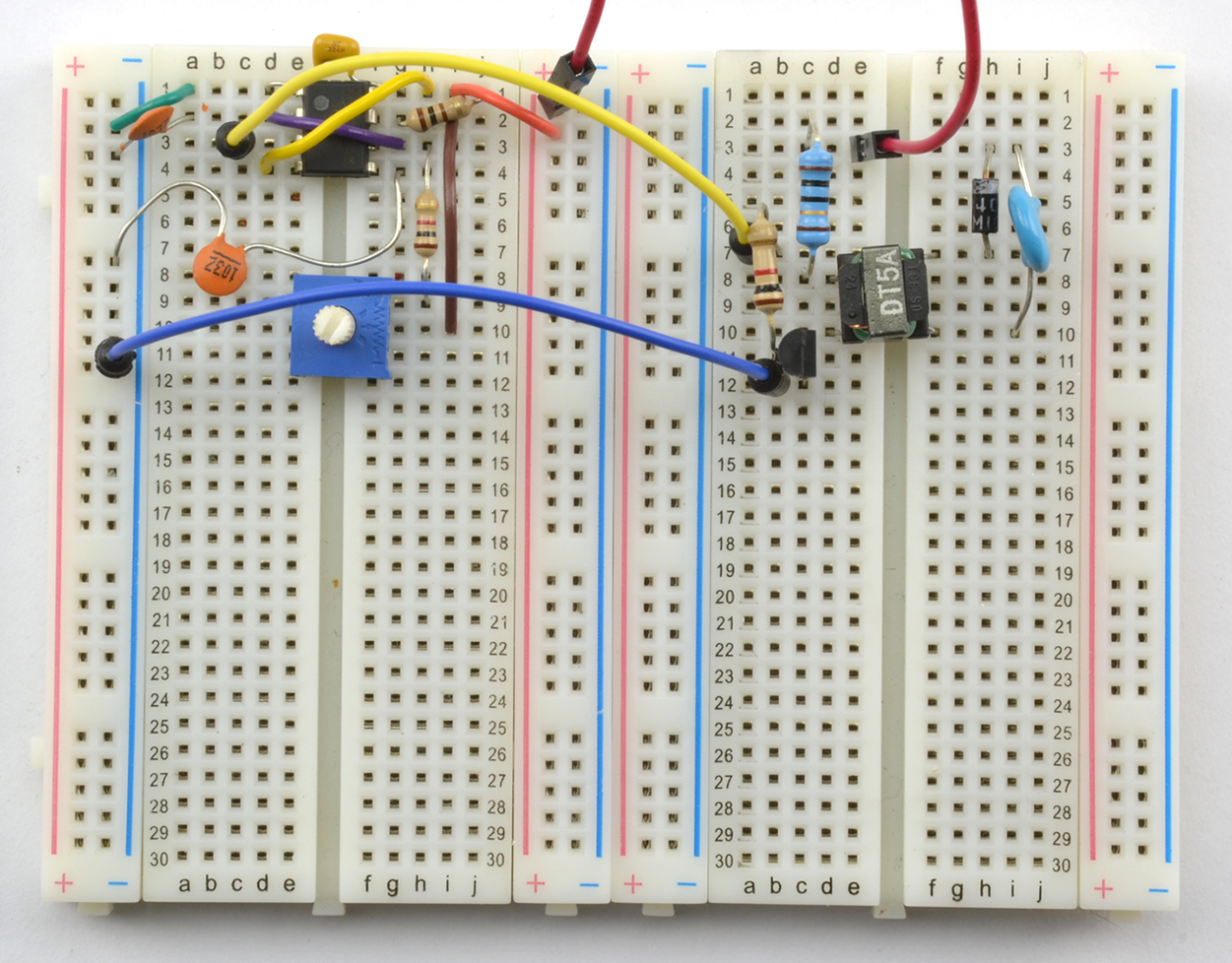

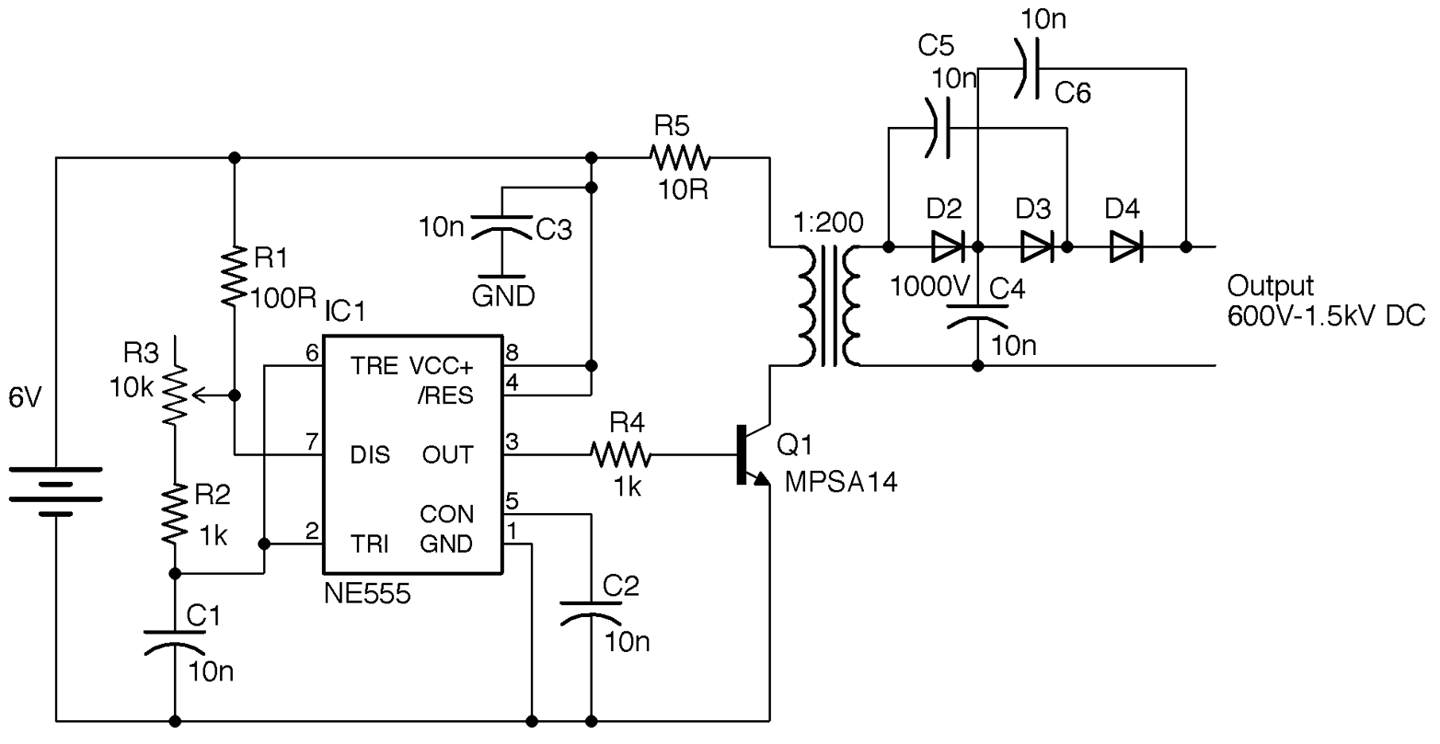

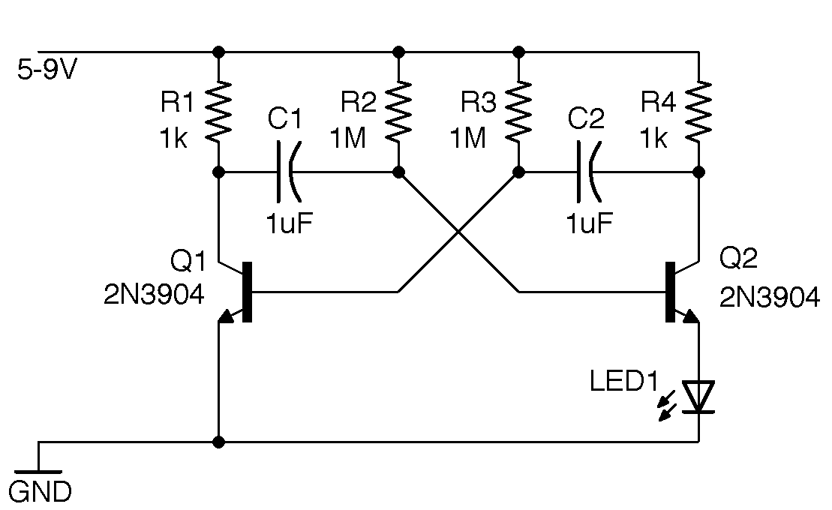

To get a feel for how such a transistor could be used as a switch, build the circuit shown in Figure 5-2 using the breadboard layout shown in Figure 5-3. For help getting started with breadboard tutorial, see Recipe 20.1.

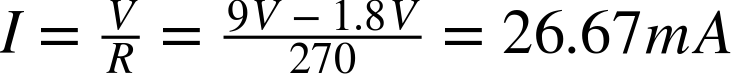

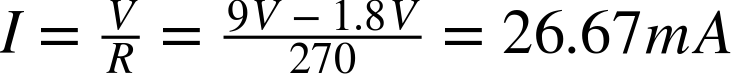

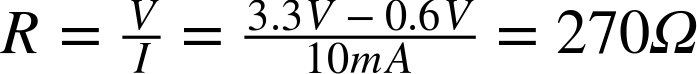

The push switch will turn the LED on when its pressed. Although this could be achieved much more easily by just putting the switch in series with the LED and R2, the important point is that the switch is supplying current to the transistor through R1. A quick calculation shows that the maximum current that could possibly flow through R1 and the base is:

In reality the current is less than this, because we are ignoring the 0.6V between the base and emitter of the transistor. If you want to be more precise, then the current is actually:

This tiny current flowing through the base is controlling a much bigger current of roughly (assuming Vf of LED 1.8V):

Just like a diode, when the BJT is in use there will be an almost constant voltage drop of around 0.5V to 1V between the base and emitter connections of the transistor.

A resistor limiting the current that can flow into the base of the transistor (R1 in Figure 5-2) is essential, because if too much current flows through the base then the transistor will overheat and eventually die in a puff of smoke.

Because the base of a transistor only requries a small current to control a much bigger current, it is tempting to think of the base as having a built-in resistance to a large current flowing. This is not the case, since it will draw a self-destructively large current as soon as its base voltage exceeds 0.6V or so. So, always use a base resistor like R1.

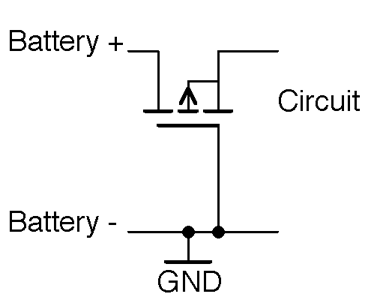

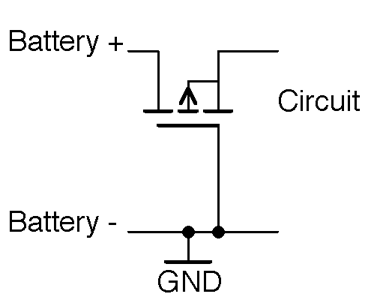

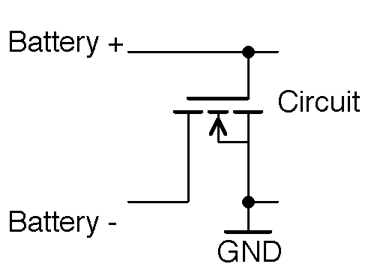

The BJT transistor described earlier is the most common and is an NPN type of transistor (negative positive negative). This is not a case of the transistor being indecisive, but relates to the fact that the transistor is made up like a sandwich with N-type (negative) semiconductor as the bread and P-type (positive) semiconductor as the filling. If you want to know what this means and understand the physics of semiconductors, then take a look at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bipolar_junction_transistor.

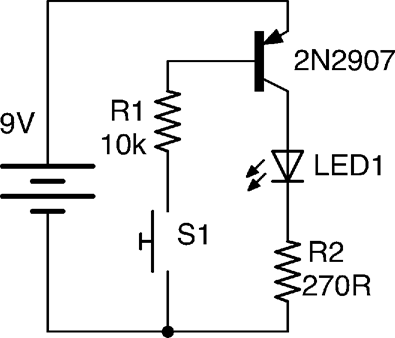

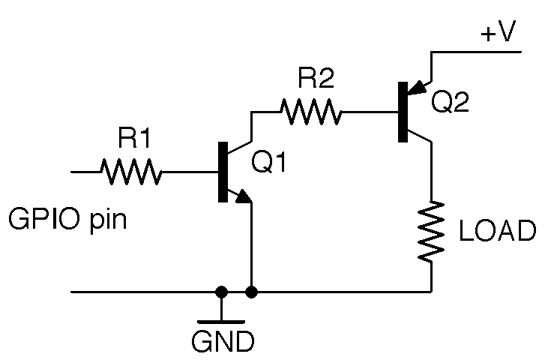

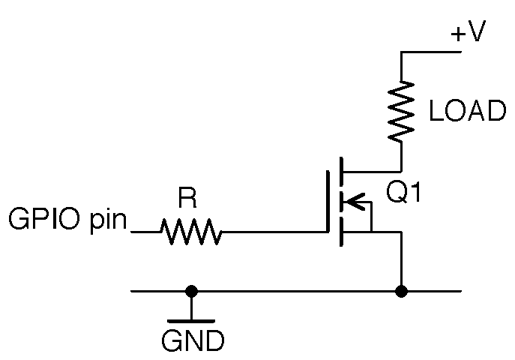

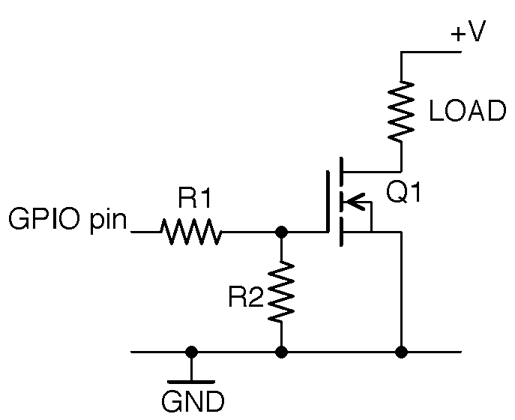

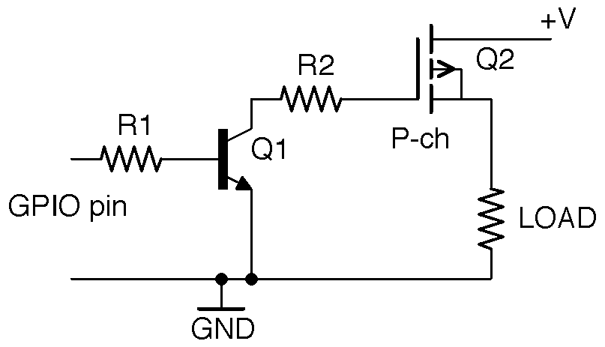

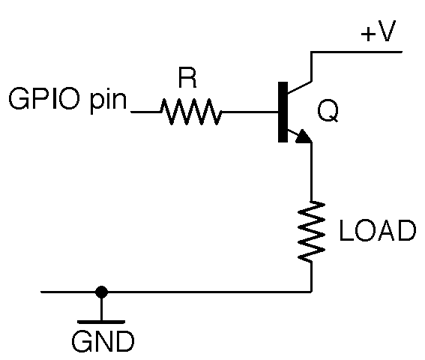

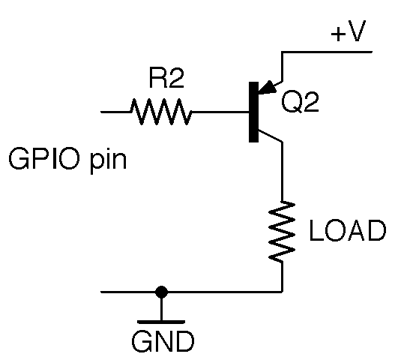

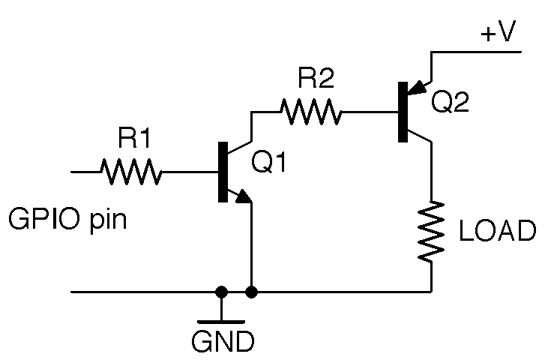

There is another less commonly used type of BJT called a PNP (positive negative positive) transistor. The filling in this semiconductor sandwich is negatively doped. This means that everything is flipped around. In Figure 5-2 the load (LED and resistor) is connected to the positive end of the power supply and switched on the negative side to ground. If you were to use a PNP transistor the circuit would look like Figure 5-4. You can find out more about using PNP transistors in Recipe 11.2.

If the gain of your transistor is not enough, you may need to consider a Darlington transistor (Recipe 5.2) or MOSFET (Recipe 5.3).

If, on the other hand, you need to switch a high-power load then you should consider a power MOSFET (Recipe 5.3) or IGBT (Recipe 5.4).

You can find the datasheet for the popular low-power BJT, the 2N3904, here: http://www.farnell.com/datasheets/1686115.pdf.

Use a Darlington transistor.

A regular BJT will typically only have a gain (ratio of base current to collector current) of perhaps 100. A lot of the time, this will be sufficient, but sometimes more gain is required. A convenient way of achieving this is to use a Darlington transistor, which will typically have a gain of 10,000 or more.

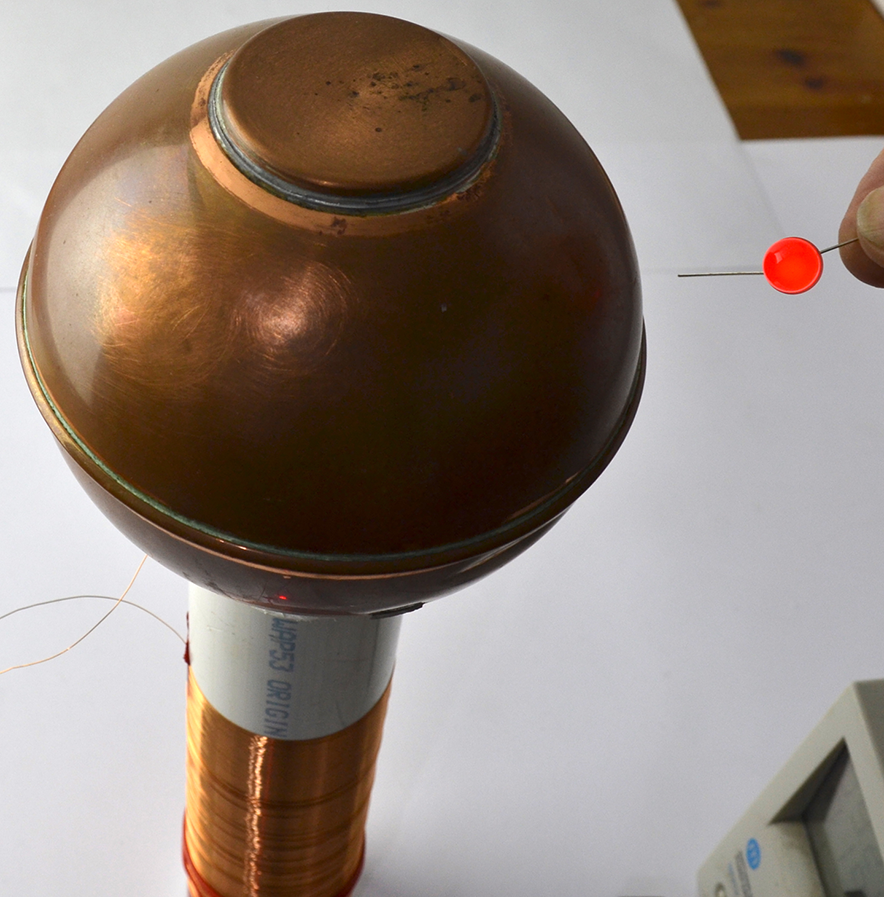

A Darlington transistor is actually made up of two regular BJTs in one package as shown in Figure 5-5. Two common Darlington transistors are shown next to the schematic symbol. The smaller one is the MPSA14 and the larger the TIP120. See Recipe 5.5 for more information on these transistors.

The overall current gain of the pair of transistors in this arrangement is the gain of the first transistor multiplied by the gain of the second. It’s easy to see why this is the case, as the base of the second transistor is supplied with current from the collector of the first.

Although you can use a Darlington transistor in designs just as if it were a single BJT, one effect of arranging the transistors like this is that there are now two voltage drops between the base and emitter. The Darlington transistor behaves like a regular NPN BJT with an exceptionally high gain but a base-emitter voltage drop of twice that of a normal BJT.

A popular and useful Darlington transistor is the TIP120. This is a high-power device that can handle a collector current of up to 5A.

You can find the datasheet for the TIP120 here: http://bit.ly/2mHBQy6 and the MPSA14 here: http://bit.ly/2mI1vXF.

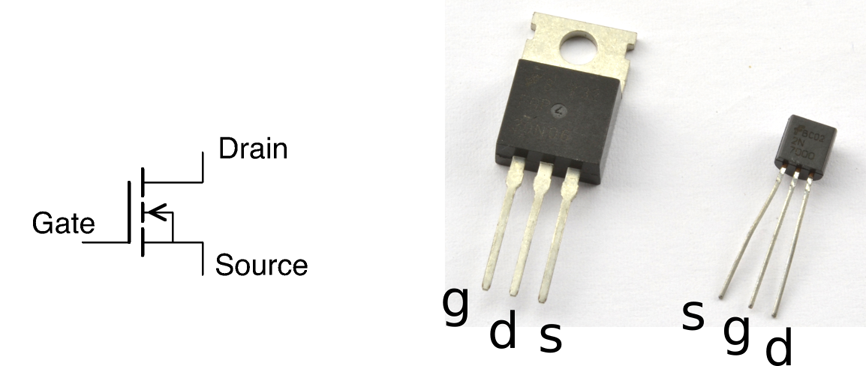

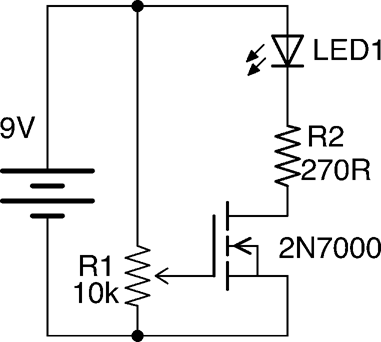

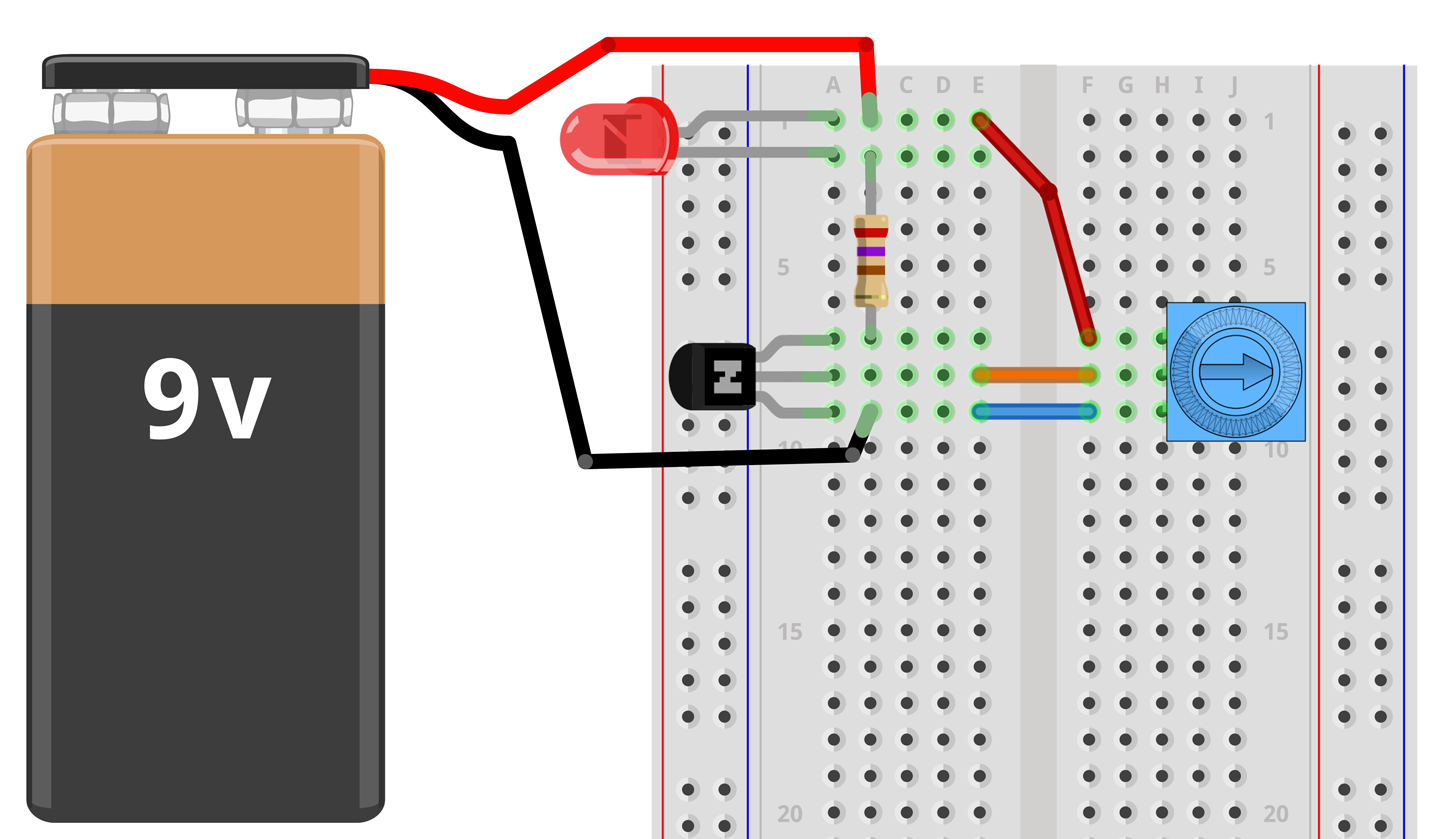

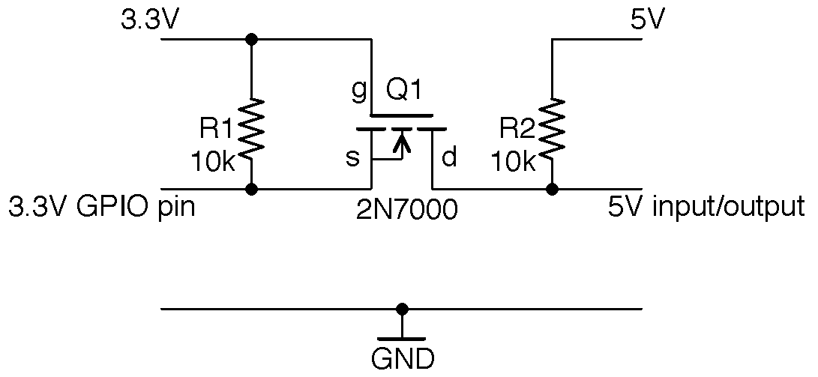

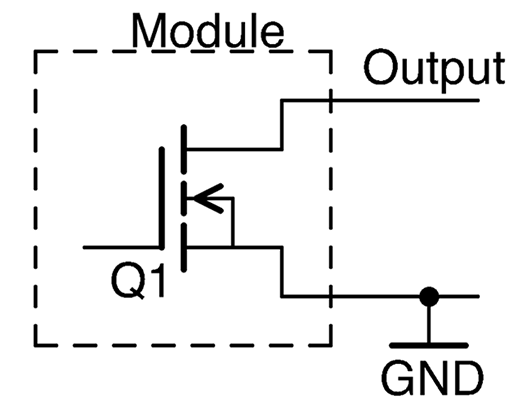

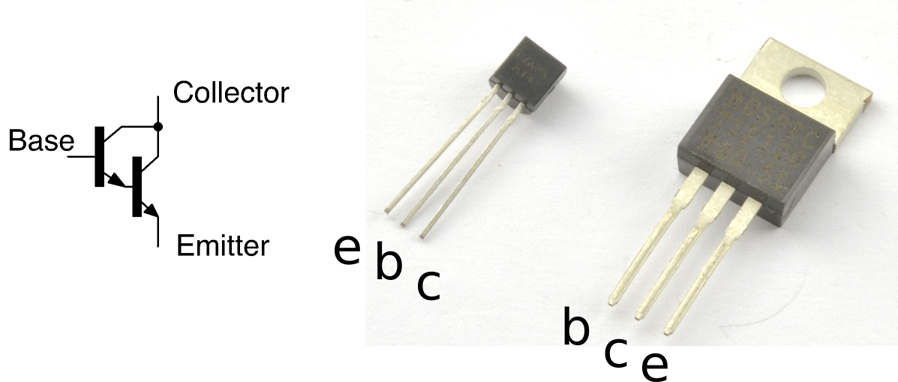

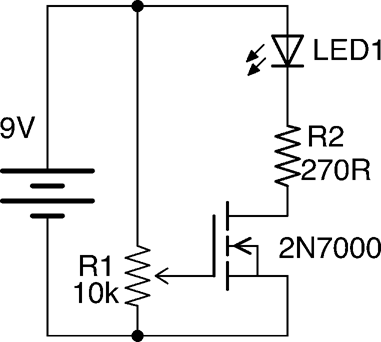

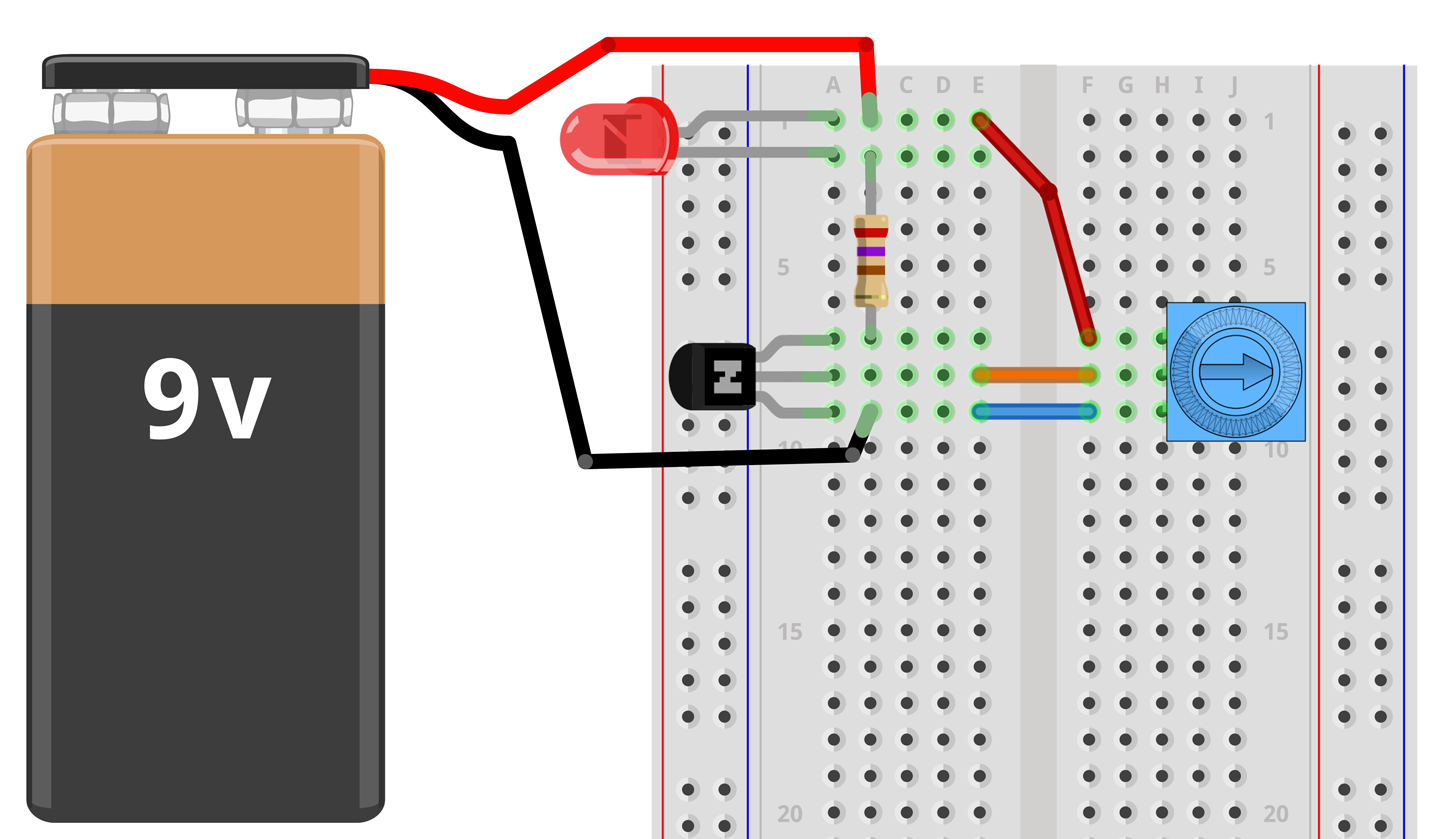

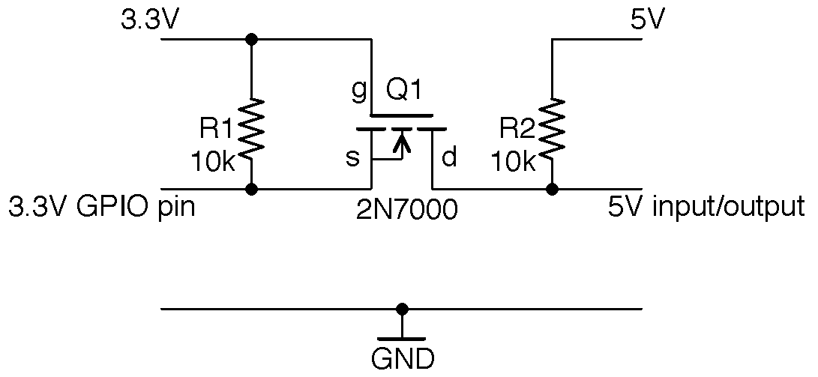

MOSFETs (metal-oxide semiconductor field effect transistors) do not have an emitter, base, and collector, but rather a source, gate, and drain. Like BJTs, MOSFETs come in two flavors: N-channel and P-channel. It is the N-channel that is most used and will be described in this recipe. Figure 5-6 shows the schematic symbol for an N-channel MOSFET with a couple of common MOSFETs next to it. The larger transistor (in a package called TO-220) is an FQP30N06 transistor capable of switching 30A at 60V. The hole in the TO-220 package is used to bolt it to a heatsink, something that is only necessary when switching high currents. The small transistor on the right is the 2N7000, which is good for 500mA at 60V.

Rather than multiply a current in the way that a BJT does, there is no electrical connection between the gate and other connections of the MOSFET. The gate is separated from the other connections by an insulating layer. If the gate-drain voltage exceeds the threshold voltage of the MOSFET, then the MOSFET conducts and a large current can flow between the drain and source connections of the MOSFET. The threshold voltage varies between 2V and 10V. MOSFETs designed to work with digital outputs from a microcontroller such as an Arduino or Raspberry Pi are called logic-level MOSFETs and have a gate-threshold voltage guaranteed to be below 3V.

If you look at the datasheet for a MOSFET you will see that it specifies on and off resistances for the transistor. An on resistance might be as low as a few mΩ and the off resistance many MΩ. This means that MOSFETs can switch much higher currents than BJTs before they start to get hot.

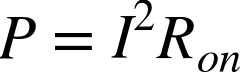

You can calculate the heat power generated by the MOSFET using the current flowing through it and its on resistance using the following formula. For more information on power, see Recipe 1.6.

The schematic and breadboard layout used in Recipe 5.1 needs a little modification to be used to experiment with a MOSFET. The variable resistor is now used to set the gate voltage from 0V to the battery voltage. The revised schematic and breadboard layouts are shown in Figures 5-7 and 5-8, respectively.

With the trimpot’s knob at the 0V end of its track, the LED will not be lit. As the gate voltage increases to about 2V the LED will start to light and when the gate voltage gets to about 2.5V the LED should be fully on.

Try disconnecting the end of the lead going to the slider of the pot and touch it to the positive supply from the battery. This should turn the LED on, and it should stay on even after you take the lead from the gate away from the positive supply. This is because there is sufficient charge sitting on the gate of the MOSFET to keep its gate voltage above the threshold. As soon as you touch the gate to ground, the charge will be conducted away to ground and the LED will extinguish.

Since MOSFETs are voltage- rather than current-controlled devices you might be surprised to find that under some circumstances you do have to consider the current flowing into the gate. That is because the gate acts like one terminal of a capacitor. This capacitor has to charge and discharge and so when pulsed at high frequency the gate current can become significant. Using a current-limiting resistor to the gate will prevent too much current from flowing.

Another difference between using a MOSFET and a BJT is that if the gate connection is left floating, then the MOSFET can turn on when you aren’t expecting it. This can be prevented by connecting a resistor between the gate and source of the MOSFET.

To use MOSFETs with a microcontroller output, see Recipe 11.3.

To use a MOSFET for polarity protection, see Recipe 7.17.

For level shifting using a MOSFET, see Recipe 10.17.

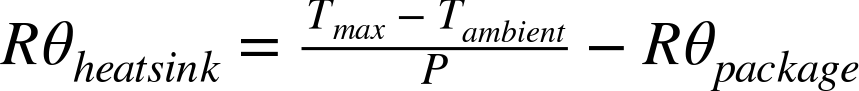

For the use of heatsinks, see Recipe 20.7.

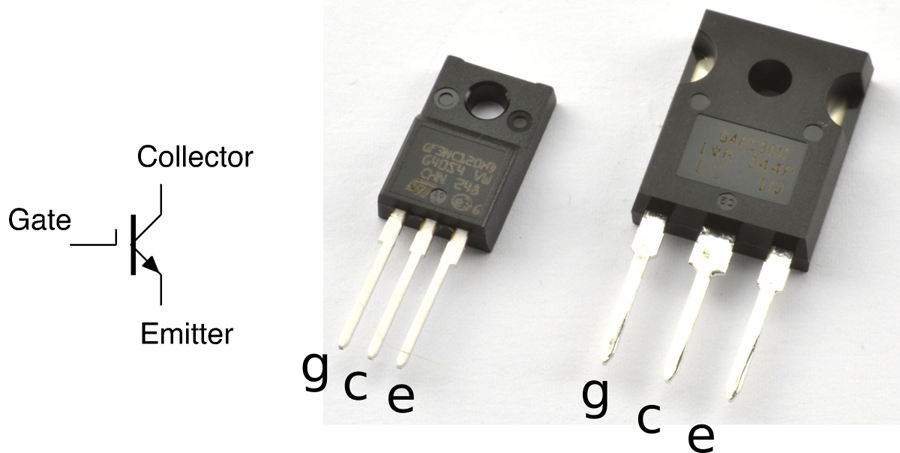

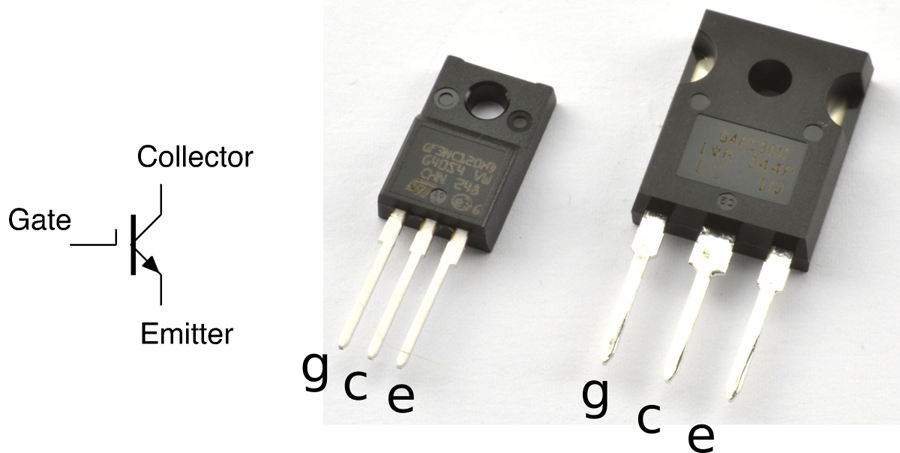

An IGBT (insulated gate bipolar transistor) is an exotic type of transistor found in high-power, high-voltage switching applications. They are fast switching, and generally are particularly well specified when it come to operating voltage. Switching voltages of 1000V are not uncommon.

A BJT has base, emitter, and collector; a MOSFET has a gate, source, and drain; and an IGBT combines the two, having a gate, emitter, and collector. Figure 5-9 shows the schematic symbol for an IGBT alongside two IGBTs. The smaller of the two (STGF3NC120HD) is capable of switching 7A at 1.2kV and the even bigger one (IRG4PC30UPBF) 23A at 600V.

IGBTs are voltage-controlled devices just like a MOSFET, but the switching side of the transistor behaves just like a BJT. The gate of an IGBT will have a threshold voltage just like a MOSFET.

IGBTs are sometimes used in the same role as high-power MOSFETs but have the advantage over MOSFETs of being able to switch higher voltages at equally large currents.

For information on BJTs see Recipe 5.1 and for MOSFETS see Recipe 5.3.

You can find the datasheet for the STGF3NC120HD here: http://bit.ly/2msNM6v.

The IRG4PC30UPBF datasheet is here: http://bit.ly/2msXTb9.

Stick to a basic set of go-to transistors for most applications until you have more unusual requirements and then find something that fits the bill.

A good set of go-to transistors is shown in Table 5-1.

| Transistor | Type | Package | Max. Current | Max. Volts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2N3904 | Bipolar | TO-92 | 200mA | 40V |

| 2N7000 | MOSFET | TO-92 | 200mA | 60V |

| MPSA14 | Darlington | TO-92 | 500mA | 30V |

| TIP120 | Darlington | TO-220 | 5A | 60V |

| FQP30N06L | MOSFET | TO-220 | 30A | 60V |

When shopping for an FQP30N06L, make sure the MOSFET is the “L” (for logic) version, with “L” on the end of the part name; otherwise, the gate-threshold voltage requirement may be too high to connect the gate of the transistor to a microcontroller output especially if it is operating at 3.3V.

The MPSA14 is actually a pretty universally useful device for currents up to 1A, although at that current there is a voltage drop of nearly 3V and the device gets up to a temperature of 120°C! At 500mA, the voltage drop is a more reasonable 1.8V and the temperature 60°C.

To summarize, if you only need to switch around 100mA then a 2N3904 will work just fine. If you need up to 500mA, use an MPSA14. Above that, the FQP30N06L is probably the best choice, unless price is a consideration, because the TIP120 is considerably cheaper.

Reasons for straying from the transistors listed in Table 5-1 include:

For information on BJTs see Recipe 5.1, for MOSFETs Recipe 5.3, and for IGBTs Recipe 5.4.

To decide on a transistor for switching with an Arduino or Raspberry Pi, see Recipe 11.5.

Once you start to push transistors beyond a light load, you will find that they start to get hot. If they get too hot they will burn out and be permanently destroyed. To avoid this, either use a transistor with greater current-handling capability or fix a heatsink to it (Recipe 20.7).

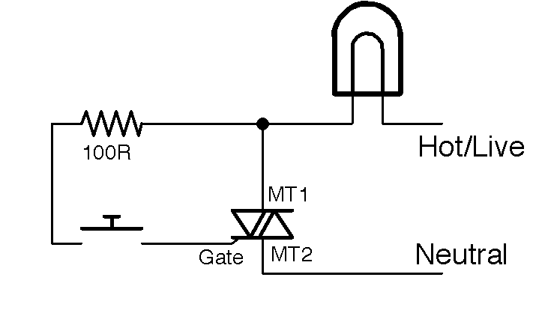

TRIAC (TRIode for alternating current) is a semiconductor-switching device designed specifically to switch AC.

BJT and MOSFETs are not useful for switching AC. They can only do that if you split the positive and negative halves of the cycle and switch each with a separate transistor. It is far better to use a TRIAC that can be thought of as a switchable pair of back-to-back diodes.

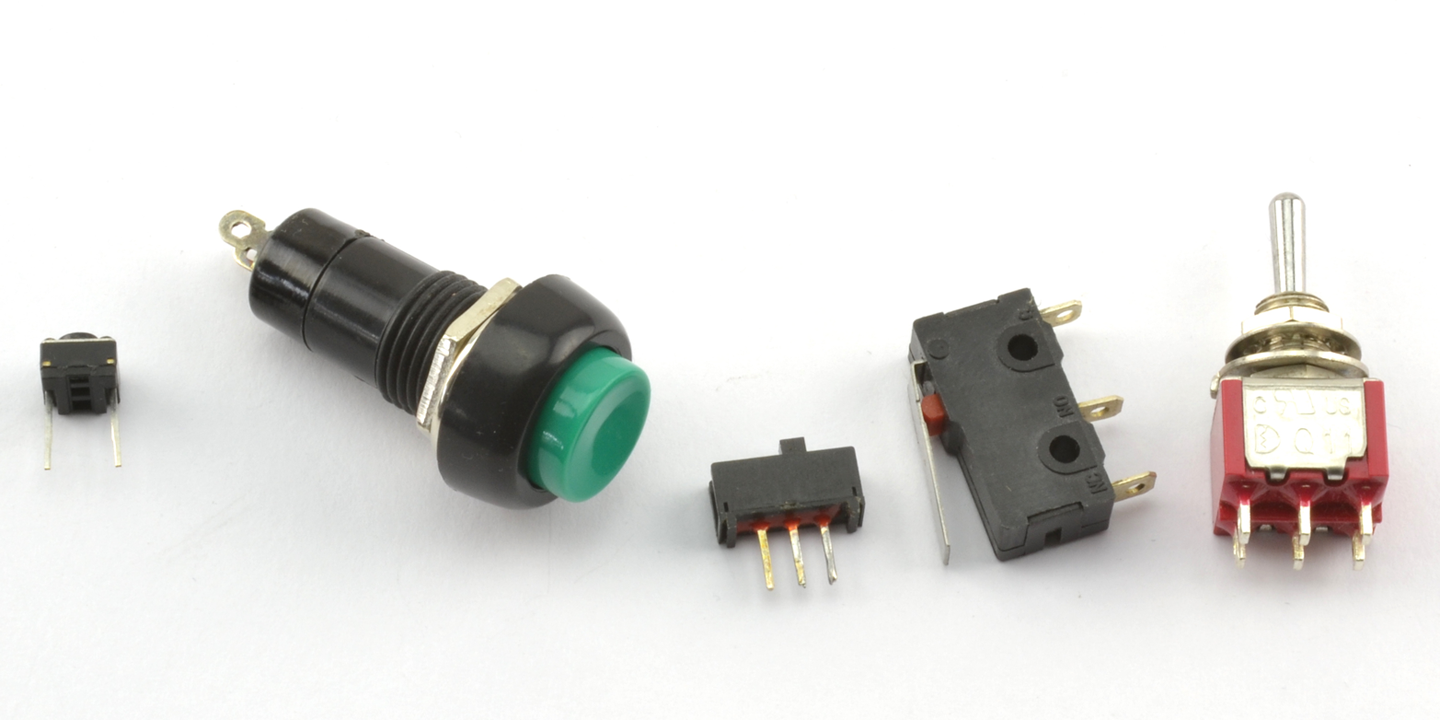

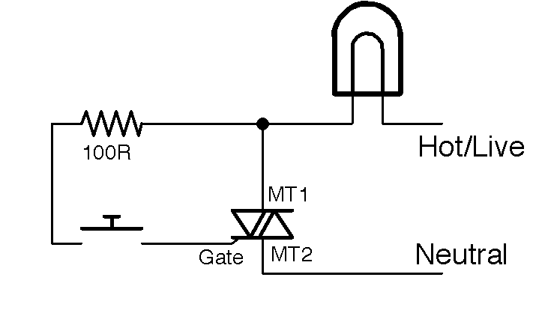

Figure 5-10 shows how a TRIAC might be used to switch a high AC load using a small current switch. A circuit like this is often used so that a small low-power mechanical switch can be used to switch a large AC current.

The 110V or 220V AC that you find in your home kills thousands of people every year. It can burn you and it can stop your heart, so please do not attempt to build the circuits described here unless you are absolutely sure that you can do so safely.

Also, see Recipe 21.12.

When the switch is pressed a small current (tens of milliamps) flows into the gate of the TRIAC. The TRIAC conducts and will continue conducting until the AC crosses zero volts again. This has the benefit that the power is switched off at low power when the voltage is close to zero, reducing the power surges and electrical noise that would otherwise occur if switching inductive loads like motors.

However, the load could still be switched on at any point in the circuit, generating considerable noise. Zero-crossing circuits (see Recipe 5.9) are used to wait until the next zero crossing of the AC before turning the load on, reducing electrical noise further.

See Recipe 1.7 on AC.

For information on solid-state relays using TRIACs, see Recipe 11.10.

TRIACs are usually supplied in TO-220 packages. For pinouts, see Appendix A.

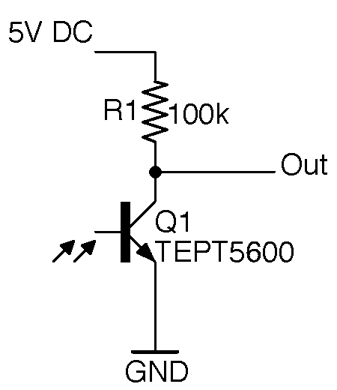

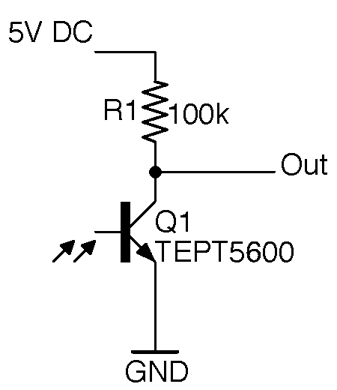

A phototransistor is essentially a regular BJT with a translucent top surface that allows light to reach the actual silicon of the transistor. Figure 5-11 shows how you can use a phototransistor to produce an output voltage that varies as the level of light falling on the transistor changes.

When the photoresistor is brightly illuminated, it will turn on and conduct, pulling the output voltage toward 0V. In complete darkness, the transistor will be completely off and the output voltage will rise to the supply voltage of 5V.

Some phototransistors look like regular transistors with three pins and a clear top and others (like the TEPT5600 used in Figure 5-11) come in LED-like packages with pins for the emitter and collector, but no pin for the base. For phototransistors that look like LEDs, the longer pin is usually the emitter. Phototransistors are nearly always NPN devices.

As a light-sensing element, the phototransistor is more sensitive than a photodiode and responds more quickly than a photoresistor. Phototransistors have the advantage over photoresistors that they are manufactured using cadmium sulphide and some countries have trade restrictions on devices containing this material.

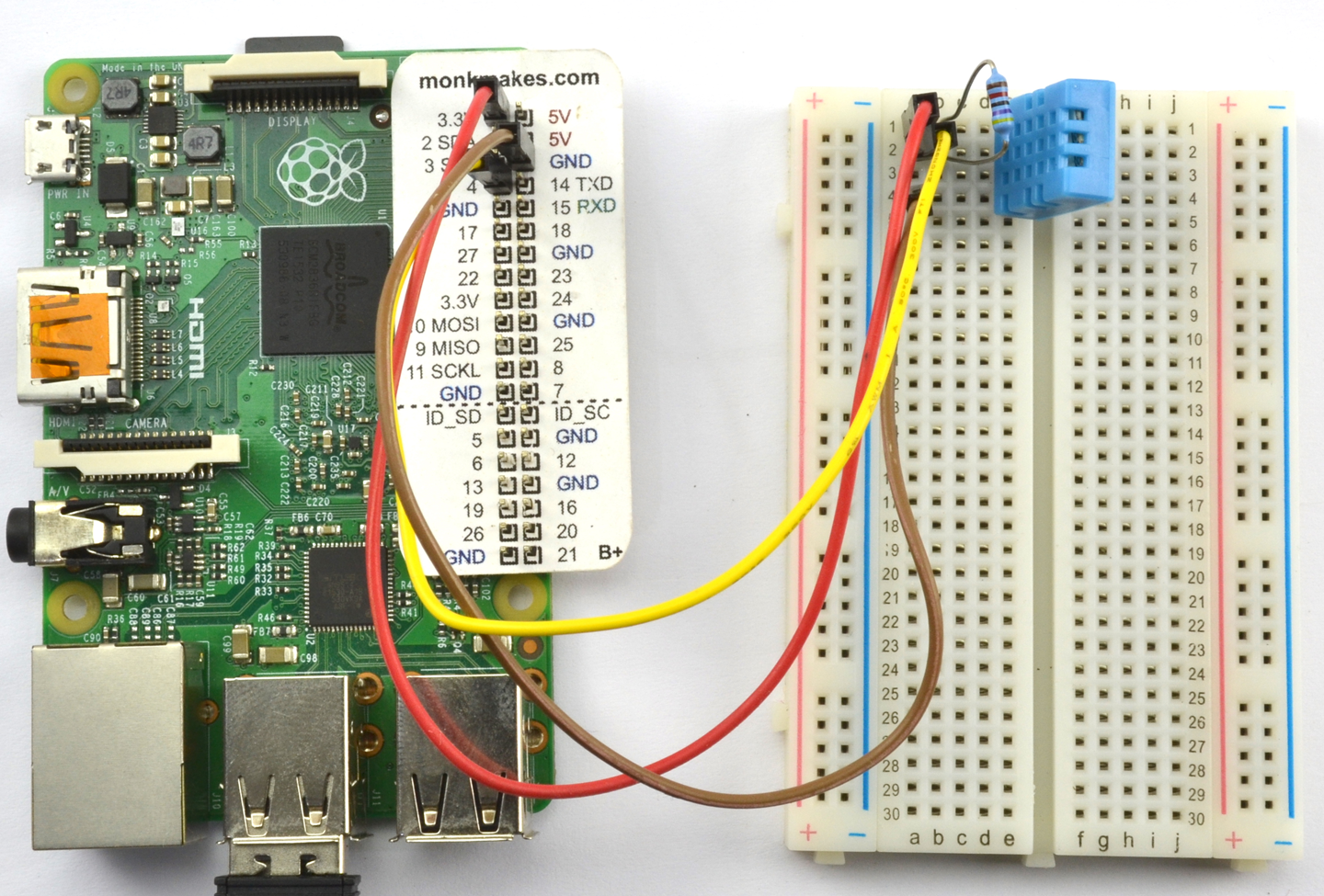

The output of the circuit of Figure 5-11 can be directly connected to an Arduino’s analog input (Recipe 10.12) to take light readings as an alternative to using a photoresistor (Recipe 12.3 and Recipe 12.6).

For the TEPT5600 datasheet, see http://bit.ly/2m8vhS0.

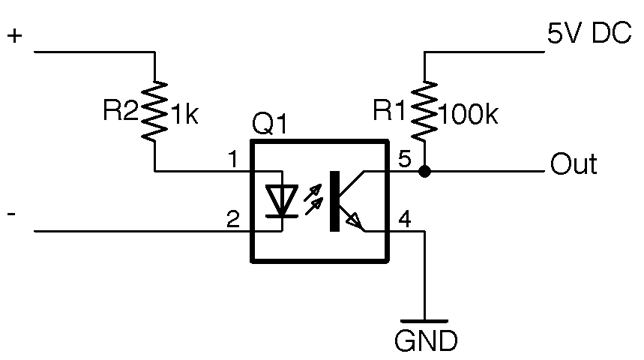

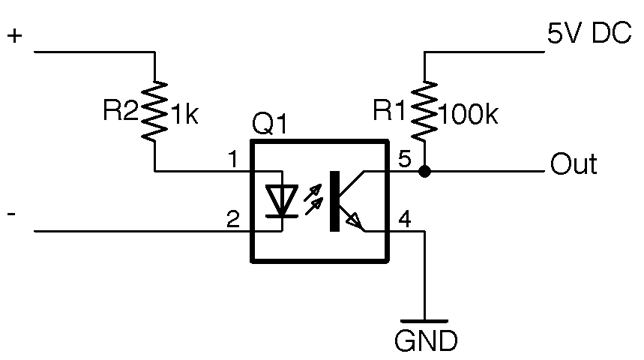

Use an opto-coupler, which consists of an LED and phototransistor sealed in a single lightproof package.

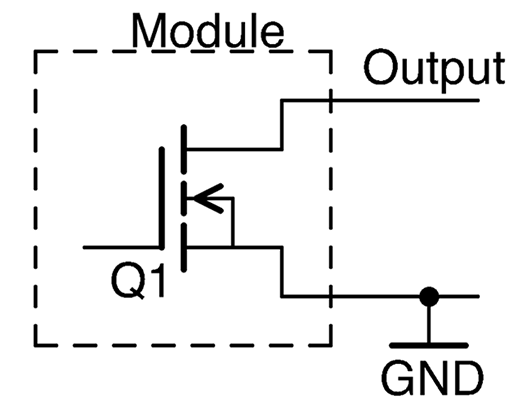

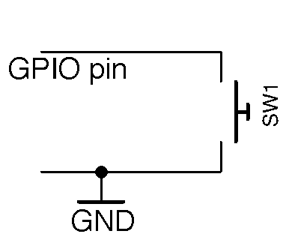

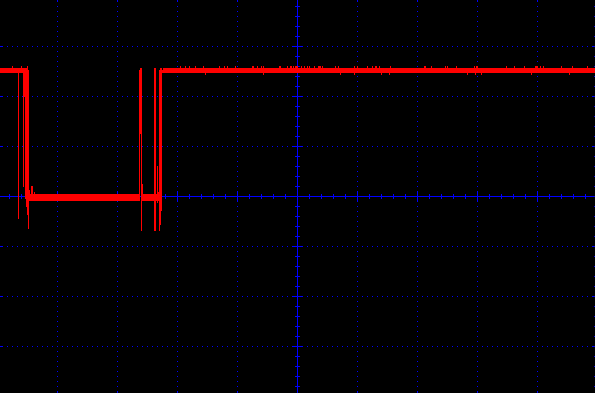

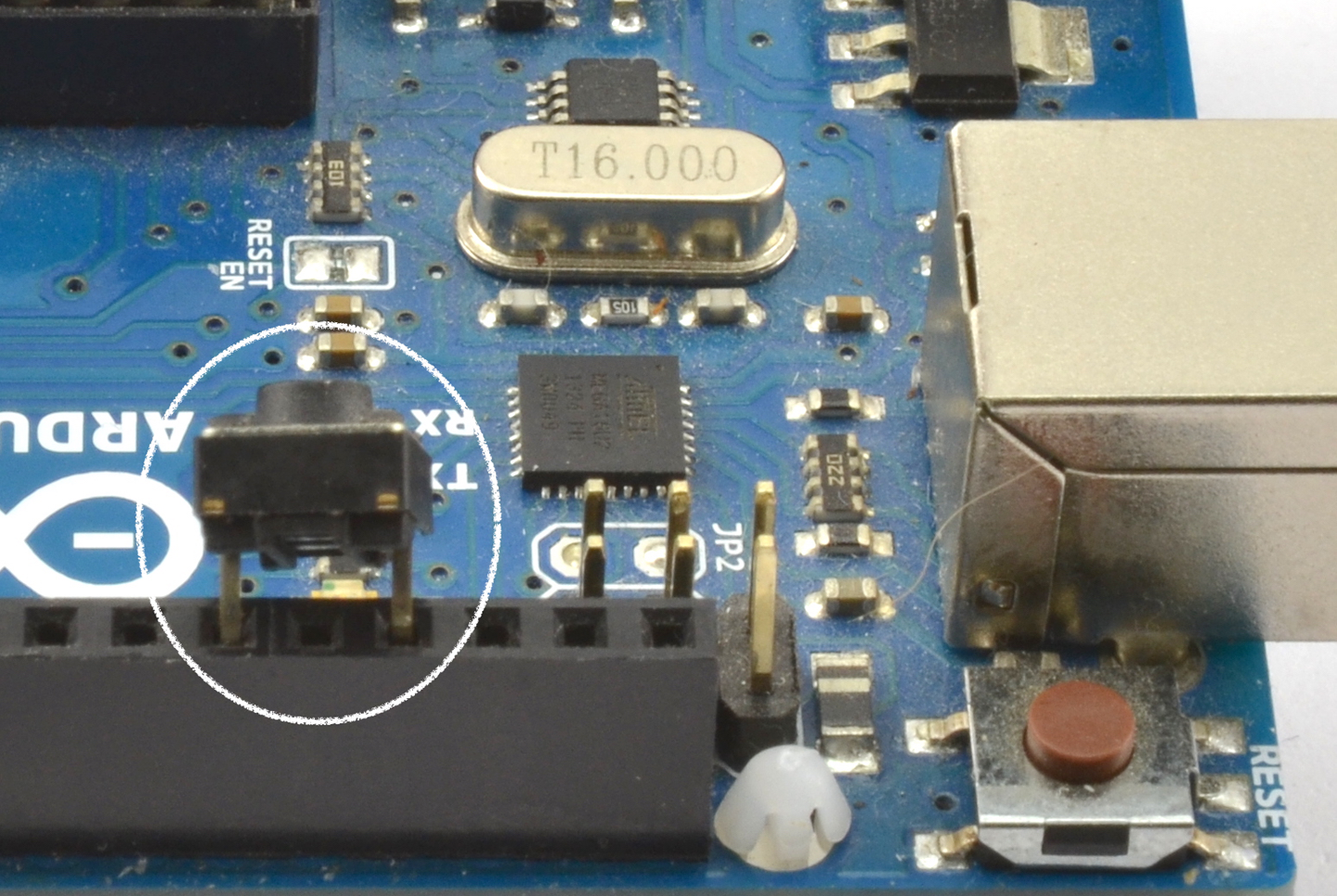

Figure 5-12 shows how an opto-coupler can be used. When a voltage is applied across the + and – terminals, a current flows through the LED and it lights, illuminating the phototransistor and turning on the transistor. This brings the output down to close to 0V. When the LED is not powered, the transistor is off and R1 pulls the output up to 5V.

The important point is that the lefthand side of the circuit has no electrical connection to the righthand side. The link is purely optical.

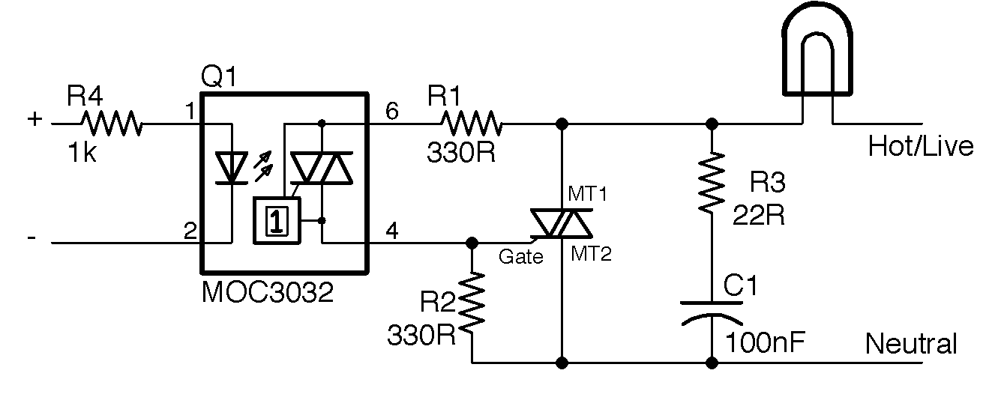

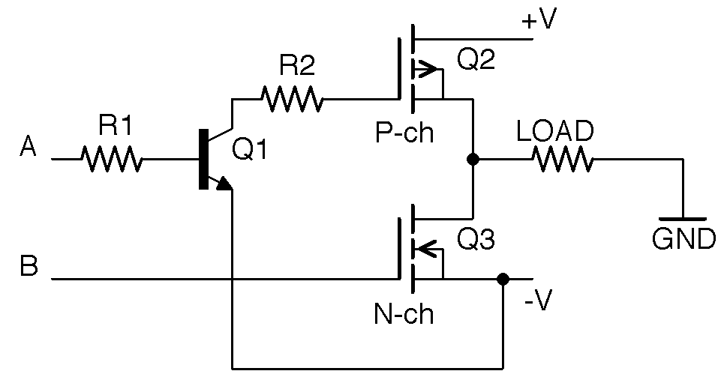

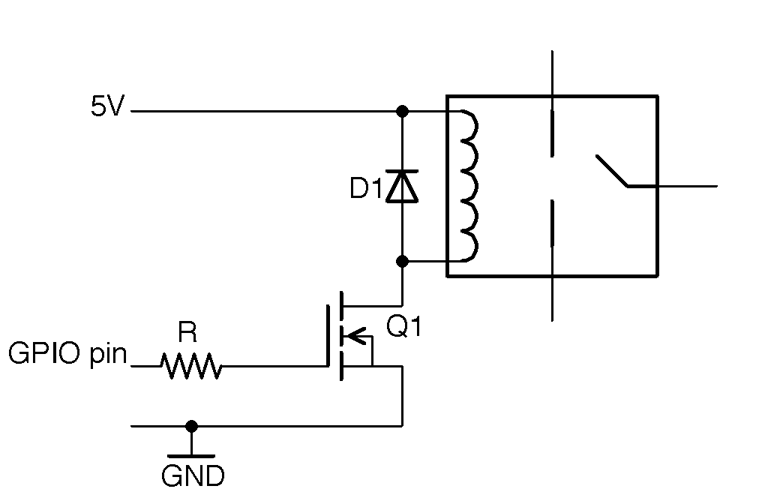

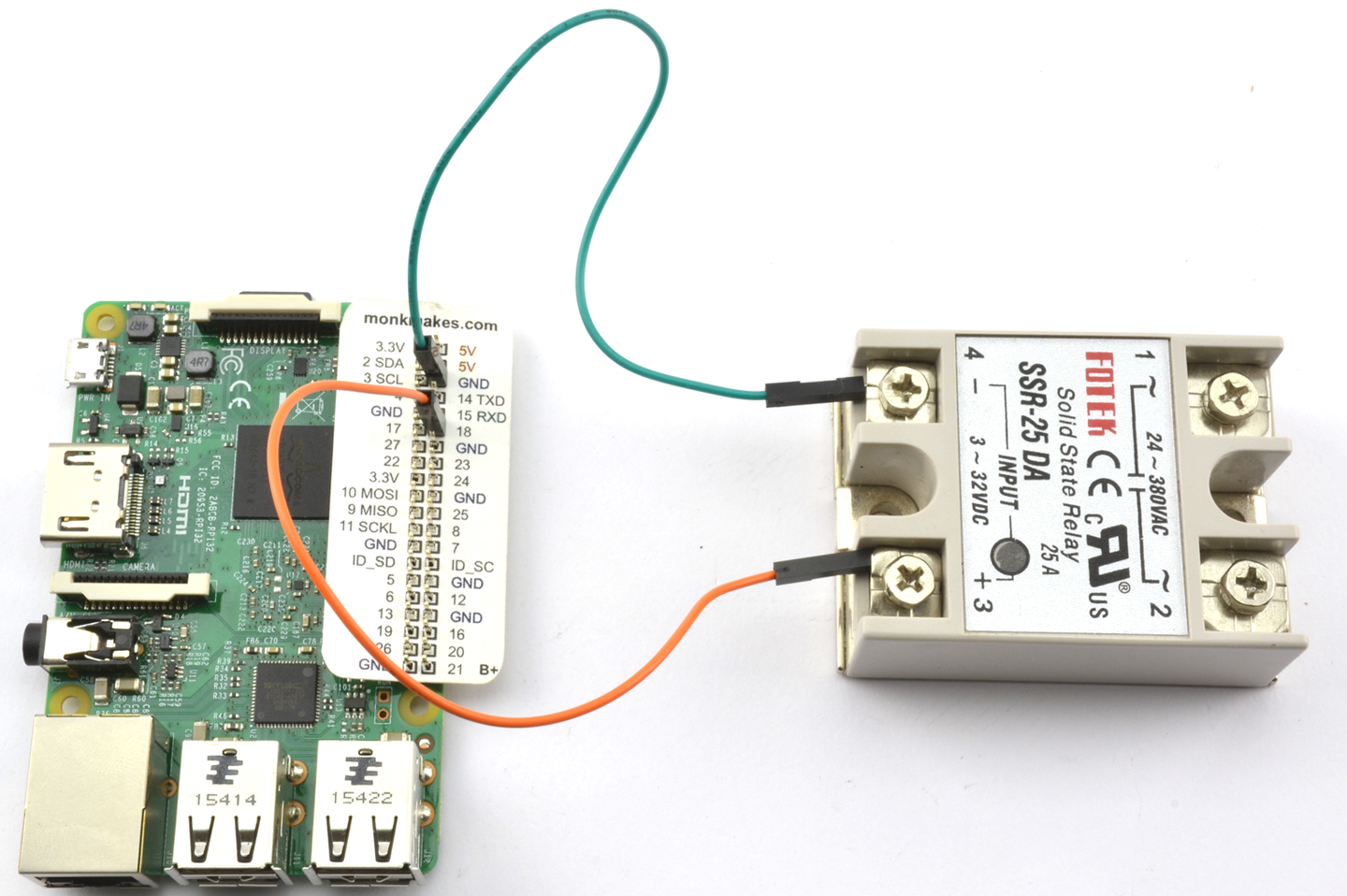

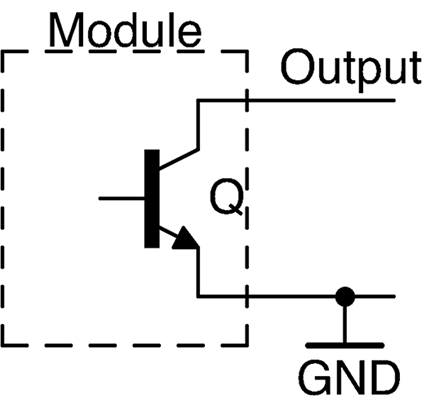

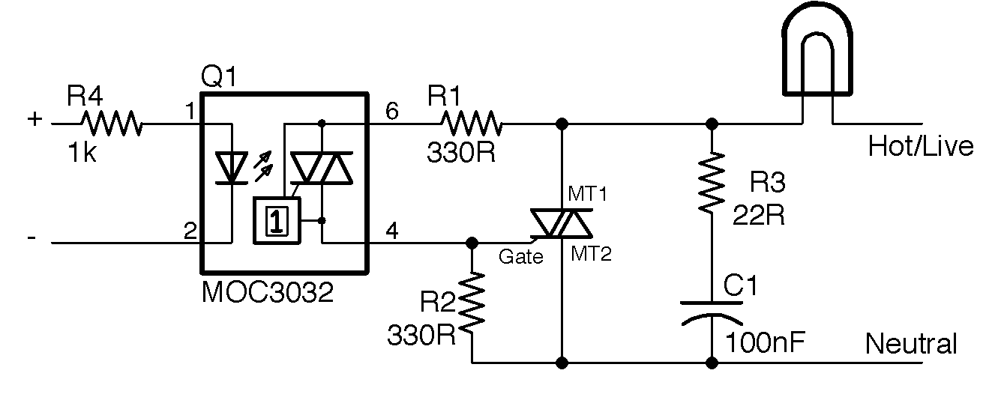

When the sensing transistor is a TRIAC (see Recipe 5.6) the device is known as an opto-isolator rather than opto-coupler and the low-power TRIAC inside the opto-isolator can be used to switch AC using a more powerful TRIAC as shown in Figure 5-13. This circuit is often called an SSR (solid-state relay) as it performs much the same role as a relay would in AC switching, but without the need for any moving parts.

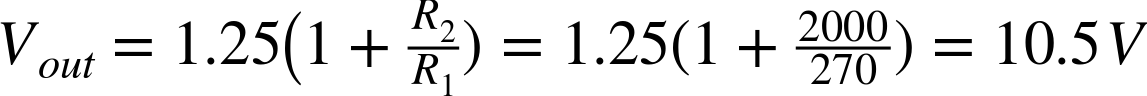

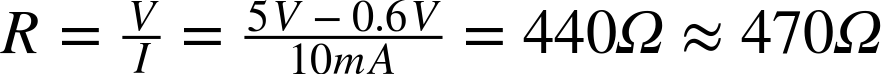

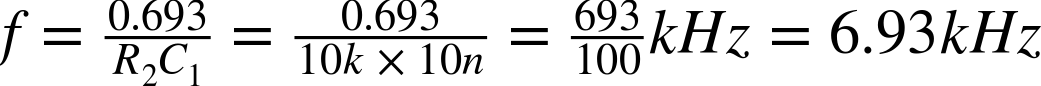

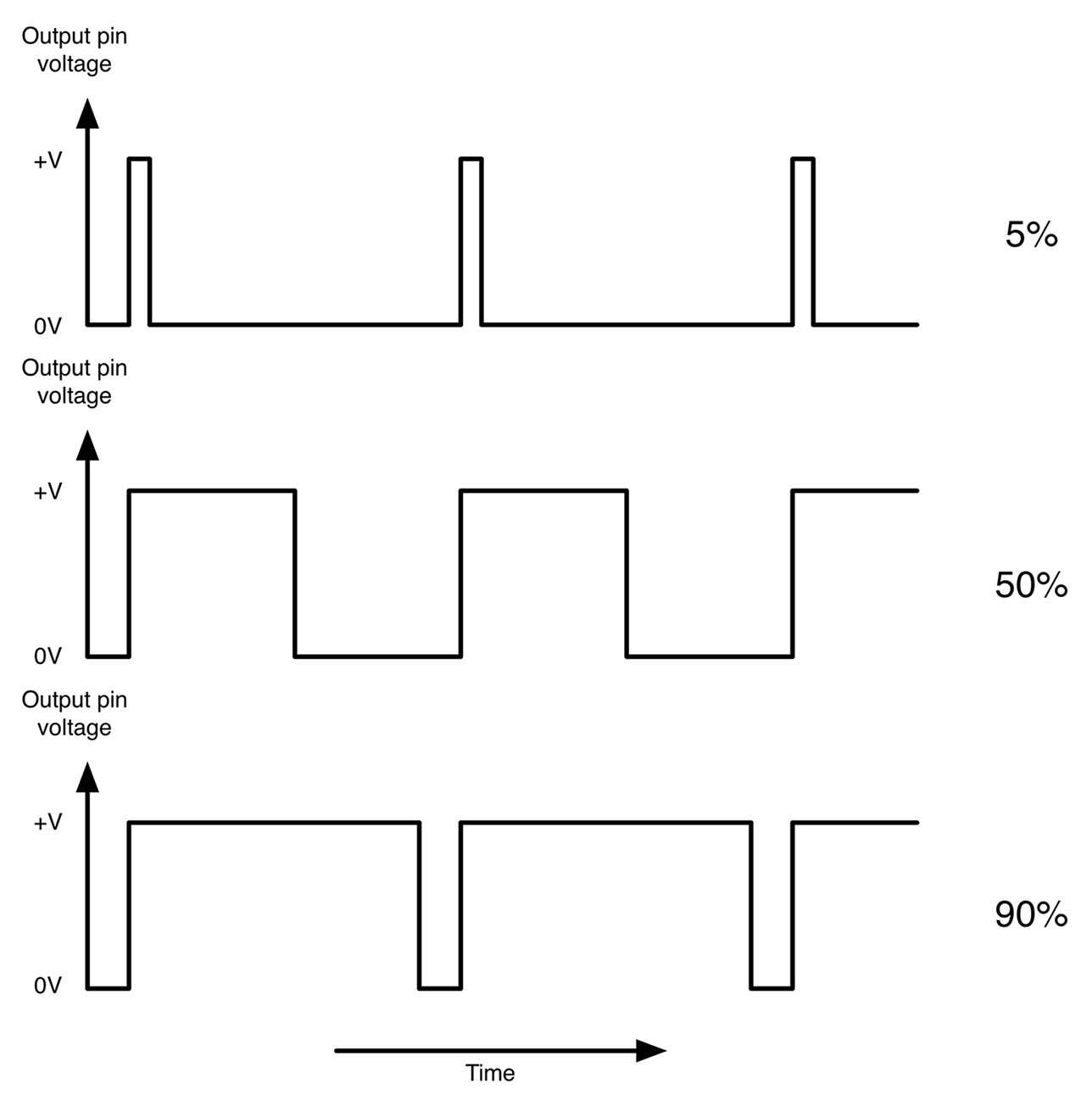

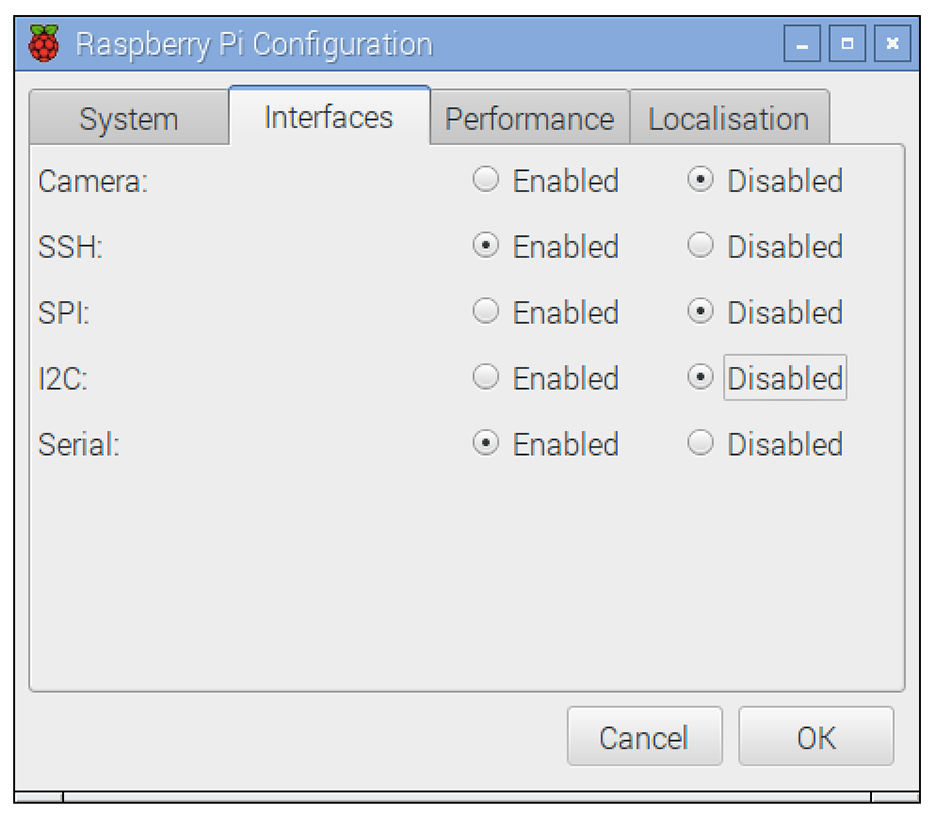

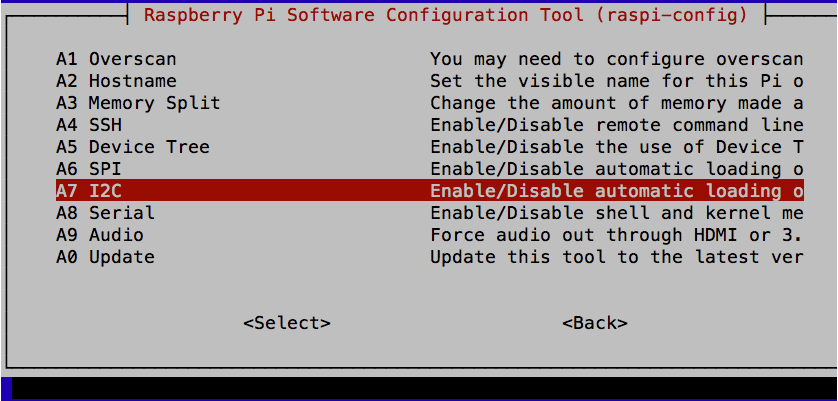

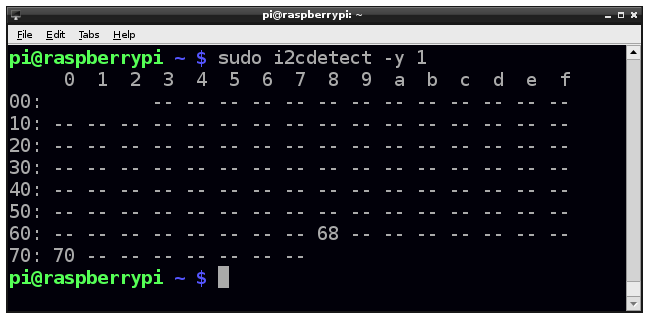

You should not work with high voltages unless you are completely sure that you can do so safely and understand the risks. See Recipe 21.12 for more information on working with high voltages.