MapScript Examples

MapServer map files are still a key component to writing a MapScript-based application. If you have a map file ready to use, you can start accessing and manipulating it right away. However, a powerful feature of MapScript is the ability to create maps on the fly without having a map file. In this case, you can build your map from scratch.

In the first two examples, a simple map file is used, as shown in Example 14-1. In the third example, a custom map file is created using MapScript. To keep the example short and simple, I’ve removed optional components like the scale bar, legend, and reference map.

MAP

SIZE 600 300

EXTENT -180 -90 180 90

IMAGECOLOR 180 180 250

IMAGETYPE PNG

UNITS DD

WEB

IMAGEPATH "/srv/www/htdocs/tmp/"

IMAGEURL "/tmp/"

END

LAYER

NAME countries

TYPE POLYGON

STATUS DEFAULT

DATA countries_simpl

CLASS

NAME 'Countries'

OUTLINECOLOR 100 100 100

COLOR 200 200 200

END

END

ENDTip

You can download the country boundary data in shapefile format from http://ftp.intevation.de/freegis/worlddata/freegis_worlddata-0.1_simpl.tar.gz.

This compressed file contains a shapefile called countries_simpl. The map file example assumes that the countries_simpl.* files are in the same folder as the map file. This dataset is used elsewhere in this book.

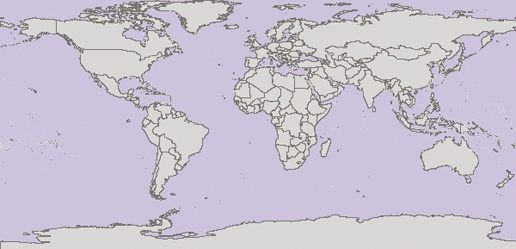

The map file shown in Example 14-1 produces the map shown in Figure 14-2.

Multiple programming languages can be used with MapScript. The examples in this chapter use the Python programming language. To show how Python and other languages compare, the same MapScript example is shown in Python, Perl, PHP, Java, and Ruby at the end of this chapter.

Warning

To keep these examples as simple as possible, no error checking, optimization, or modularization is included. These examples aren’t intended to be used as-is in a production environment.

Opening the Map File and Drawing the Map

The most basic functionality of MapServer is its ability to read in a map file and create an image showing the map. This can be done with MapScript in only a few short steps, as shown in Example 14-2.

# map1.py

# Python MapScript Example 1

import mapscript

# Set the map file to use

mapfile = "global.map"

# Create a mapObj, initialized with the mapfile above

mapobject = mapscript.mapObj(mapfile)

# Create an imgObj that has an image of the map

mapimage = mapobject.draw()

# Save the mapimage to a file

mapimage.save("worldmap.png")In Example 14-2,

the lines starting with the pound #

symbol are comments that help describe the process. In other

languages, comments may be coded differently. As you can see, this is

a very short example. Here’s a description of each line of

code.

mapfile = "global.map"

This line doesn’t use MapScript at all; rather it sets the

mapfile variable to a string that

points to the global.map map file

it loads in the next step.

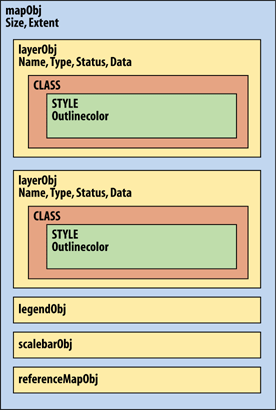

mapobject = mapscript.mapObj(mapfile)

This line creates an object that becomes the core of the

application, the map object or mapObj. Just like a map file (which includes

the map object and has layers, projections, and other settings in it),

so mapObj is the highest level in

the MapScript object hierarchy. All the other objects used in this

example are taken from it.

Many attributes and methods are available for the mapObj. In this example, only one method is

used.

mapimage = mapobject.draw()

The draw method of the mapobject returns an image object or

imgObj. This object is stored in

the variable mapimage.

mapimage.save("worldmap.png")The final step uses the save() method to take the map image and save

it to a file. The output filename for the image is given as a string

directly in the method, but can also be assigned as a separate string

variable like mapfile was

earlier.

Tip

If you provide an empty string for the filename in the

save() method, MapScript prints

the image to stdout. Depending on

the language and how the application is being run, stdout may be a terminal, interpreter

shell, web page, etc.

That’s it! Now you can take this basic example and incorporate some mapping capabilities into your own application.

Manipulating Map Settings

Example 14-3 demonstrates Python MapScript interacting with the map object. It shows how to create a new class that uses a class expression to highlight a certain country.

# map2.py # Python MapScript Example 2 import mapscript # Set the map file to use mapfile = "global.map" # Create a mapObj, initialized with the mapfile above mapobject = mapscript.mapObj(mapfile)# Get the first layer and set a classification attribute layer1 = mapobject.getLayer(0) layer1.classitem = "NAME"# Get the first Class in the layer and duplicate it classCanada = layer1.getClass(0) layer1.insertClass(classCanada)# Give the class a meaningful name classCanada.name = "Canada"# Set the expression used to limit the features drawn classCanada.setExpression("Canada")# Get the Style and modify the Color used canadaStyle = classCanada.getStyle(0) canadaStyle.color.setRGB(250, 250, 125)# Create an imgObj that has an image of the map mapimage = mapobject.draw() # Save the mapimage to a file mapimage.save("worldmap.png")

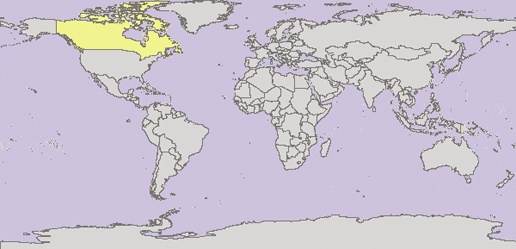

This example modifies the properties of the layer, adds a new class, and changes its color. Perhaps the most powerful feature it demonstrates is the ability to create or modify expressions that limit what features are drawn. The map produced is shown in Figure 14-3.

The following is a closer examination of Example 14-3.

layer1 = mapobject.getLayer(0) layer1.classitem = "NAME"

The setting of the classitem

layer property is really the first new line added to this example.

Just like setting a CLASSITEM

property in the map file, this setting allows the use of an expression

that filters the features shown in a class. In this case, the

attribute called "NAME" is queried

using the value of the expression. This won’t be used until the

setExpression() function later

on.

classCanada = layer1.getClass(0) layer1.insertClass(classCanada)

This may look a little obscure. The first line gets the first

class (0) defined for the layer. In

the map file there is only one CLASS object defined. The insertclass() function creates a second

class by copying the original. The purpose of this example is to show

Canada highlighted on the world map, therefore we keep the first class

in place without modifying and then make a copy of it and filter out

all countries other than Canada.

classCanada.name = "Canada"

classCanada.setExpression("Canada")Setting the .name property

for a class allows it to be used when drawing a legend. In this case,

a legend isn’t being drawn, but it is a good habit to always name your

classes for future reference.

The setExpression() function

is the heart of this example. You may have been expecting to see some

kind of logical statement such as an SQL clause like:

...where country = 'Canada'

That style of statement is possible, but this example shows a

simple way of doing the same thing. The value set in the expression

here is used along with the classitem property for the layer. Therefore,

behind the scenes, the statement: [NAME] =

"Canada" is used to exclude

features that don’t meet this criteria.

You can set statements like this in setExpression() too, without having a

classitem set for the layer, but

getting the syntax right can be tricky and varies depending on the

type of data source. The more simple you can keep it, the better. For

more information on using expressions with MapServer, see the "Understanding Operators"

section in Chapter 10.

canadaStyle = classCanada.getStyle(0) canadaStyle.color.setRGB(250, 250, 125)

These final new lines simply change the color of the features (those that meet the expression logic) to a highlighting yellow. The value (250, 250, 125) represents the proportion of red, green, and blue color values to shade the features with.

Creating a Map File from Scratch

The next example, Example 14-4, doesn’t use an existing map file but creates its own. The map file it creates is similar to that shown in Example 14-1. The sections are laid out to mimic the structure of the map file in Example 14-1 so that you can easily follow the logic of the program.

# custommapfile.py

# Build a custom map file using Python MapScript

import mapscript

# Create the map object, set properties

map = mapscript.mapObj()

map.name = "CustomMap"

map.setSize(600,300)

map.setExtent(-180.0,-90.0,180.0,90.0)

map.imagecolor.setRGB(180, 180, 250)

map.units = mapscript.MS_DD

# Set the web object image properties

map.web.imagepath = "/srv/www/htdocs/tmp/"

map.web.imageurl = "/tmp/"

# Create the layer object, as a child of the map

layer = mapscript.layerObj(map)

layer.name = "countries"

layer.type = mapscript.MS_LAYER_POLYGON

layer.status = mapscript.MS_DEFAULT

layer.data = "countries_simpl"

layer.template = "template.html"

# Create the class object as a child of the layer

class1 = mapscript.classObj(layer)

class1.name = "Countries"

# Create a style object as a child of the class

style = mapscript.styleObj(class1)

style.outlinecolor.setRGB(100, 100, 100)

style.color.setRGB(200, 200, 200)

# Write the map object into a map file

map.save("custom.map")The map file that this script creates doesn’t look identical to Example 14-1 because MapScript creates several other default values. However, the map file functions in the same manner and produces the same map image as a result.

Warning

The object names used in this example are simple but not

necessarily recommended because they are so close to the names of

actual MapScript objects. This isn’t a problem in this example, but

would be a problem if the class1

object had been named class.

Because class is a reserved

keyword for many programming languages, it produces an error if used

as a object name.