Different Kinds of Web Mapping

One very effective way to make map information available to a group of nontechnical end users is to make it available through a web page. Web mapping sites are becoming increasingly popular. There are two broad kinds of web mapping applications: static and interactive.

Static maps displayed as an image on a web page are quite common. If you already have a digital map (e.g., from scanning a document), you can be up and running very quickly with a static map on your web page. Basic web design skills are all you need for this because it is only a single image on a page.

Tip

This book doesn’t teach web design skills. O’Reilly has other books that cover the topic of web design, from basic to advanced, including: Learning Web Design, Web Design in a Nutshell, HTML and XHTML: The Definitive Guide, and many more.

Interactive maps aren’t as commonly seen because they require specialized skills to keep such sites up and running (not to mention the potential costs of buying off-the-shelf software). The term interactive implies that the viewer can somehow interact with the map. This can mean selecting different map data layers to view or zooming into a particular part of the map that you are interested in. All this is done while interacting with the web page and a map image that is repeatedly updated. For example, MapQuest is an interactive web mapping program for finding street addresses and driving directions. You can see it in action at http://www.mapquest.com.

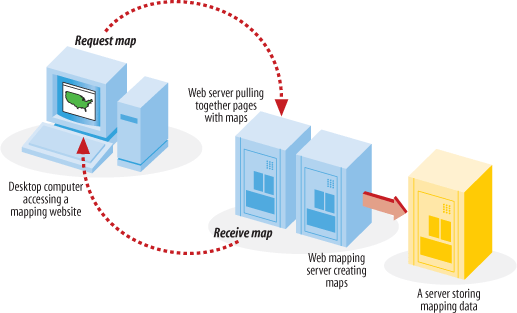

Interactive maps that are accessed through web pages are referred to as web-based maps or simply web maps . These maps can be very powerful, but as mentioned, they can also be difficult to set up due to the technical skills required for maintaining a web server, a mapping server/program and management of the underlying map data. As you can see, these types of maps are fundamentally different from static maps because they are really a type of web-based program or application. Figure 1-2 shows a basic diagram of how an end user requests a map through a web mapping site and what happens behind the scenes. A user requests a map from the web server, and the server passes the request to the web mapping server, who then pulls together all the data. The map is passed all the way back to the end user’s web browser.

Web Map Users

Generally speaking, there are two types of people who use web maps: service providers and end users.

For instance, I am a service provider because I have put together a web site that has an interactive mapping component you can see it at: http://spatialguru.com/maps/apps/global. One of the maps available to my end users shows the locations of several hurricanes. I’m safely tucked away between the Rocky and Coastal mountain ranges in western Canada, so I wouldn’t consider myself a user of the hurricane portion of the site. It is simply a service for others who are interested.

An end user might be someone who is curious about where the hurricanes are, or it may be a critical part of a person’s business to know. For example, they may just wonder how close a hurricane is to a friend’s house or they may need to get an idea of which clients were affected by a particular hurricane. This is a good example of how interactive mapping can be broadly applicable yet specifically useful.

End-user needs can vary greatly. You might seek out a web mapping site that provides driving directions to a particular address. Someone else might want to see an aerial photo and topographic map for an upcoming hiking trip. Some end users have a web mapping site created to meet their specific needs, while others just look on the Internet for a site that has some capabilities they are interested in.

Service providers can have completely different purposes in mind for providing a web map. A service provider might be interested in off-loading some of the repetitive tasks that come his way at the office. Implementing a web mapping site can be an excellent way of taking previously inaccessible data and making it more broadly available. If an organization isn’t ready to introduce staff to more traditional GIS software (which can have a steep learning curve), having one technical expert maintain a web mapping site is a valuable service.

Another reason a service provider might make a web mapping site available is to more broadly disseminate data without having to transfer the raw data to clients. A good example of this is my provincial government, the Province of British Columbia, Canada. They currently have some great aerial photography data and detailed base maps, but if you want the digital data, you have to negotiate a data exchange agreement or purchase the data from them. The other option is to use one of their web mapping sites. They have a site available that basically turns mapping into a self-serve, customizable resource; check it out at: http://maps.gov.bc.ca.

Web Sites with a Web Mapping Component

There are many web mapping sites available for you to use and explore. Table 1-1 lists a few that use software or apply similar principles to the software described in this book.

Web site | Description |

Tsunami disaster mapping site | |

Portal to U.S. topographic, imagery, and street maps | |

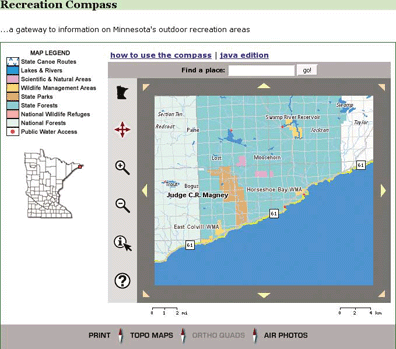

Various recreational and natural resource mapping applications for the state of Minnesota, U.S.A. | |

Portal for Canadian trails information and maps | |

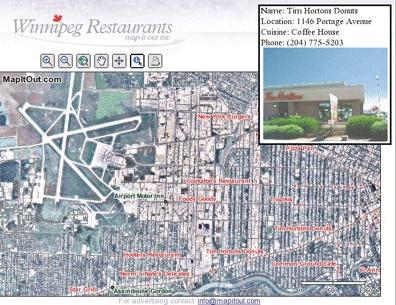

Restaurant locating and viewing site for the city of Winnipeg, Canada | |

Portal to Gulf of Maine (U.S.A.) mapping applications and web services | |

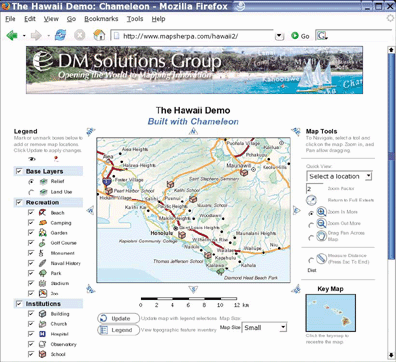

Comprehensive atlas of Hawaii, U.S.A. | |

Real-time U.S.A. weather maps | |

View global imagery and places |

Figures 1-3, 1-4, and 1-5 show the web pages of three such sites. They show how diverse some MapServer applications can be, from street-level mapping to statewide overviews.

Of course, not all maps out there are built with MapServer; Table 1-2 lists other mapping sites that you may want to look to for inspiration.

Web site | Description |

U.S. portal to maps and mapping data | |

Locate hotels, tourism, and street maps | |

Portal to applications and data | |

Search for a place; find an address | |

Find an address; plan a route | |

Maps showing the location of some MapServer users | |

Thousands of rare/antique maps | |

Find an address; get driving directions, or check real-time traffic | |

Google maps that focus on North America and require Windows | |

Canadian topographic maps and aerial photos | |

Canadian portals to geographic information and services; include premade maps |

Behind the web page

To some people, web mapping sites may appear quite simple, while to others, they look like magic. The inner workings of a web mapping site can vary depending on the software used, but there are some common general concepts:

The web server takes care of web page requests and provides pages with images, etc. included, back to the requestor.

The web mapping server accepts requests relayed from the web server. The request asks for a map with certain content and for a certain geographic area. It may also make requests for analysis or query results in a tabular form. The web mapping server program then creates the required map images (or tabular data) and sends them back to the web server for relay back to the end user.

The web mapping server needs to have access to the data sources required for the mapping requests, as shown in Figure 1-2. This can include files located on the same server or across an internal network. If web mapping standards are used, data can also come from other web mapping servers through live requests.

More information on the process of web mapping services can be found in Chapters 4, 11, and 12: those chapters discuss MapServer in depth.

Making your own web mapping site

This book will teach about several of the components necessary to build your web mapping site, as well as general map data management. To give you an overview of the kinds of technology involved, here are some of the basic requirements of a web mapping site. Only the web mapping server and mapping data components from this list are discussed in this book.

- A computer

This should be a given, but it’s worth noting that the more intensive the web mapping application you intend to host, the more powerful the computer you will want to have. Larger and more complex maps take longer to process; a faster processor completes requests faster. Internet hosting options are often too simplistic to handle web mapping sites, since you need more access to the underlying operating system and web server. Hosting services specifically for web mapping may also be available. The computer’s operating system can be a barrier to running some applications. In general, Windows and Linux operating systems are best supported, whereas Mac OS X and other Unix-based systems are less so.

- An Internet connection

It is conceivable that you would have a web mapping site running just for you or for an internal (i.e., corporate) network, but if you want to share it with the public, you need a publicly accessible network connection. Some personal Internet accounts limit your ability to host these types of services, requiring additional business class accounts that carry a heavier price tag. Performance of a web mapping site largely depends on the bandwidth of the Internet connection. If, for example, you produce large images (that have larger file sizes), though they run instantaneously on your computer, such images may take seconds to relay to an end user.

- A web server

A web server is needed to handle the high-level communications between the end user (who is using a web browser to access your mapping site) and the underlying mapping services on your computer. It presents a web page containing maps and map-related tools to the end user. Two such servers are Apache HTTP Server (http://httpd.apache.org/) and Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) (http://www.microsoft.com/WindowsServer2003/iis/default.mspx). If you use an Internet service provider to host your web server, you may not be able to access the required underlying configuration settings for the software.

- A web mapping server

The web mapping server is the engine behind the maps you see on a web page. The mapping server or web mapping program needs to be configured to communicate between the web server and assemble data layers into an appropriate image. This book focuses on MapServer, but there are many choices available.

- Mapping data

A map isn’t possible without some sort of mapping information for display. This can be satellite imagery, database connections, GIS software files, text files with lists of map coordinates, or other web mapping servers over the Internet. Mapping data is often referred to as spatial or geospatial data and can be used in an array of desktop mapping programs or web mapping servers.

- Mapping metadata

This isn’t a basic requirement, but I mentioned it here because it will emerge as a major requirement in the future. Metadata is data about data. It often describes where the mapping data came from, how it can be used, what it contains, and who to contact with questions. As more and more mapping data becomes available over the Internet, the need for cataloging the information is essential. Services already exist that search out and catalog online data sources so others can find them easily.

Over the course of this book, you’ll learn to assemble these components into your own interactive mapping service.