Spatial Data Queries

One of the strengths of PostGIS is its ability to store spatial data in a mature, enterprise-level, relational database. Data is made available through standard SQL queries, making it readily available to do analysis with another program without having to import and export the data into proprietary data formats. Another key strength is its ability to use spatially aware PostGIS functions to perform the analysis within the database, still using SQL. The spatial data query examples in this section are the most basic possible. PostGIS boasts of a variety of operators and functions for managing, manipulating, and creating spatial data, including the ability to compute geometric buffers, unions, intersections, reprojecting between coordinate systems, and more. The basic examples shown here focus on loading and accessing the spatial data.

To see what data is in the countyp020 table, you can use any basic SQL

query to request a listing. For example, this typical SQL query lists

all data in the table, including the very lengthy geometry definitions.

Running this query isn’t recommended:

# SELECT * FROM countyp020;Getting a list of over 6,000 counties and their geometries would hardly be useful. A more useful query might be something like Example 13-3 which limits and groups the results.

# SELECT DISTINCT county FROM countyp020 WHERE state = 'NM';

county

---------------------------------

Bernalillo County

Catron County

Chaves County

Cibola County

Colfax County

Curry County

DeBaca County

Dona Ana County

Eddy County

Grant County

Guadalupe County

Harding County

Hidalgo County

Lea County

Lincoln County

...

(33 rows)This query lists all the counties in the state of New Mexico

(state = 'NM'). This has nothing to

do with the spatial data, except that all this information was

originally in the shapefile that was loaded. To see some of the

geographic data, you must run a query that returns this

information.

Example 13-4 shows a query that lists all the information about Curry County, including a list of all the geometric points used to define the shape of the county.

Tip

At the beginning of this example the \x command tells psql to list the data in expanded display

mode. This is a bit easier to read when there is a lot of data and

very few records. Using \x a second

time disables expanded mode.

project1=#\xExpanded display is on. project1=#SELECT * FROM countyp020 WHERE state='NM' AND county = 'Curry County';[ RECORD 1 ] ------------------------------------------- ogc_fid | 4345 wkb_geometry | SRID=-1;POLYGON((-103.04238129 34.74721146, -103.04264832 34.36763382,-103.04239655 34.30997849, -103.0424118 34.30216599,-103.73503113 34.30317688, -103.49039459 34.77983856...)) area | 0.358 perimeter | 2.690 countyp020 | 4346 state | NM county | Curry County fips | 35009 state_fips | 35 square_mil | 1404.995

Tip

More recent versions of PostGIS don’t display the geometry as

text by default. To have it display coordinates in text format, you

must use the astext() function with

the wkb_geometry column

like:

SELECT astext(wkb_geometry) FROM...

Some of the geometry information has been removed because the list of coordinates is very long; there is one pair of coordinates for every vertex in the polygon. This example shows how you can access spatial coordinate data directly with your queries. No GIS program is required to get this level of information, just basic SQL. The results may not be in the format you need, but you can modify it to suit your purposes. For example, if you are creating a custom application that needs access to geographic coordinates, you can call a PostgreSQL database, access the geometry of a table, then manipulate the data into the form your application needs.

Most people interested in web mapping don’t need to create their own custom application for accessing and using the power of PostGIS. MapServer, for example, can query PostGIS for the geometry of these features and display it on a map. You only need to know how to point MapServer to the right database and table. More on using MapServer with PostGIS follows later in this chapter.

Building Spatial Indexes

Before doing spatial queries, some preparation work is needed.

To improve spatial query performance, you should build spatial

indexes for any tables that hold geometry data. This is done

using the CREATE INDEX command with a few geometry options.

The command to create an index for the geometry in the countyp020 table looks like this:

# CREATE INDEX idx_countyp020_geo ON countyp020 USING GIST (wkb_geometry

GIST_GEOMETRY_OPS);The idx_countyp020_geo

keyword is used for the name of the index, which is completely

arbitrary. The second parameter countyp020 is the name of the table you are

creating the index for. The field that holds the geometry data is

identified as wkb_geometry.This is

the default name given to the geometry columns of data converted with

the ogr2ogr utility. The rest of

the command consists of keywords needed for the indexing functions to

run and must be used as shown.

Any index creation steps should be followed with the command:

# vacuum analyze <table name>This does some internal database housekeeping, which helps your queries run more efficiently. You can also run it without specifying a particular table, and it will analyze all the tables. With large amounts of data, the vacuum process can take a long time. Running it on all the tables takes even longer to complete.

Critical Tabular Indexes

Spatial indexing on its own doesn’t ensure high

performance in your application. You must generally manage spatial and

nonspatial data querying efficiently. To do so, you should create

regular table indexes for any fields used in the WHERE clause of your query. To optimize for

MapServer data access and querying, you can create an index on the

unique ID for the table. However, the unique ID used by MapServer may

not be apparent. There are two approaches to consider when using

PostGIS layers in MapServer. If you use a simple PostGIS connection statement such

as:

DATA wkb_geometry from countyp020

MapServer uses PostgreSQL’s internal object ID. This is accessed

by referring to it as a field named oid. There are MapServer examples later in

this chapter.

Tip

The oid column doesn’t

appear in the column listing for a table using \dt, but you can use it in a SELECT statement to see what the values

are.

If MapServer is using a FILTER setting or being used to query

features, building an index for the oid column will improve performance. You can

build one using a standard CREATE

INDEX statement:

# CREATE INDEX idx_countyp020_oid ON countyp020 (oid);

When you use a more complex DATA setting, such as the subquery shown

later in Example 13-10,

you need to specify what unique ID column to use because MapServer

doesn’t necessarily have access to the oid column. You do this with the USING UNIQUE <column name> statement. An index should be

created for this column.

Querying for Spatial Proximity

Normal SQL with tabular data is quite powerful, but

using PostGIS functions to query for spatial relationships between

data opens up another dimension of analysis. GIS analysis software was

once needed to do these kinds of queries, but now you can do it within

a PostGIS database. For example, you can query the countyp020 table to give you a list of the

counties within a certain distance of your home county. You can also

do queries across different tables that have spatial data stored in

them. If you have a table with the coordinates for certain points of

interest, you can query between that table and the countyp020 table to find which county your

points are in. The following examples show some of the basics of

PostGIS, in the context of some typical spatial tasks.

Find the county for a given point

This example will take a point that is within the United

States and use that coordinate to find what county it falls in. A

quick search on the Internet for the location of Mount St. Helens

brings up the site http://www.fs.fed.us/gpnf/volcanocams/msh/faqs/location.shtml.

The site lists the coordinates of the summit as: 46.20 N, 122.18 W.

These coordinates can be used in a query of the countyp020 shapes.

Here is the SQL statement, with some description of the parts following:

#SELECT county#FROM countyp020#WHERE distance( wkb_geometry,#'POINT(-122.18 46.20)'#) = 0;county ---------------------------------------------------- Skamania County (1 row)

SELECTcountyspecifies what column you want to see values from as a result of this query. This example requests the name of the county this point is in.FROMcountyp020identifies which table you are querying counties for. This query is pretty simple, using a single table calledcountyp020.Line three is where the spatial capabilities start to kick in. The

WHEREkeyword begins a section that limits the results you see. In this case, PostgreSQL shows only the counties that meet the criteria specified after theWHEREkeyword.The

WHEREclause contains two parts: the distance function and the criteria to compare the results of the distance function to. The distance function is denoted bydistance(.....). This is a PostGIS function for comparing two geometric features. It takes two parameters, and each must be a geometric feature. The first parameter to use is:wkb_geometry--the name of the column that holds the spatial data in thecountyp020table. The second parameter (separated from the first by a comma) is text that was manually put together:'POINT(-122.18 46.20)'. This is a well-known text (WKT) representation of a geometric point. Here are where the coordinates of Mount St. Helens are used. The have been slightly reformatted so they are in the order:POINT(<longitude> <latitude>)or:

POINT(X Y)

The coordinates are simply wrapped by the word

POINT, to tell PostGIS what kind of geometric feature you are using.The final line in the query tells PostGIS to compare the distance between the two features and limits the results to those that are

=0. These are features that are side by side or overlap each other. The query is sent away, and PostGIS returns the results—a list of all the counties that the point falls in. Of course, there is only one because a point can only be in one place at a time.

If you have several points making a line, you can add those

points here by adding in more pairs of coordinates separated by

commas. The keyword POINT is then

replaced by LINESTRING:

LINESTRING(-122.18 46.20, -122.00 45.00)

All the counties the line went through are now returned:

county ---------------------------------------------------- Skamania County Multnomah County Clackamas County (3 rows)

Querying for nearby county polygons

Shapes within a table can also be compared against each other; this uses the SQL method referred to as a self join. One table is joined back to itself to do some comparisons. Example 13-5 compares one particular county with all the other counties in order to see which counties border it.

Example 13-5 is

much like the previous section’s example, but the WHERE and FROM clauses refer to a second table. In

this case, the second table is the same as the first but is given an

alias. Both tables are given aliases, a and b, respectively. These can now be thought

of as different tables.

#SELECT a.county#FROM countyp020 a,#countyp020 b#WHERE b.county = 'Sonoma County'#AND a.wkb_geometry && b.wkb_geometry;county ---------------------------------------------------- Sonoma County Napa County Yolo County Lake County Mendocino County Marin County Solano County (7 rows)

Table a is targeted by the

query in the SELECT statement.

The list of counties is from table a. The results from that query are

constrained by values in table b.

The first part of the WHERE

clause—b.county = 'Sonoma County'—reduces table b to being, in essence, just one polygon.

This constraint makes the query much more manageable. The query

would be relatively useless if it tried to find all counties and all

their neighbors. Don’t wait up for the answer!

The final line of the query, a.wkb_geometry && b.wkb_geometry, is where PostGIS comes in.

Both the geometry columns are compared using the && operator. This operator

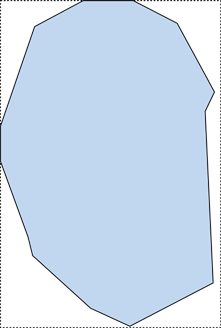

compares the bounding box (bbox) of each shape to check for

overlaps. The bounding box of a shape is the rectangle that

encompasses the extent of the shape, as shown by the dashed

rectangular outline in Figure 13-1.

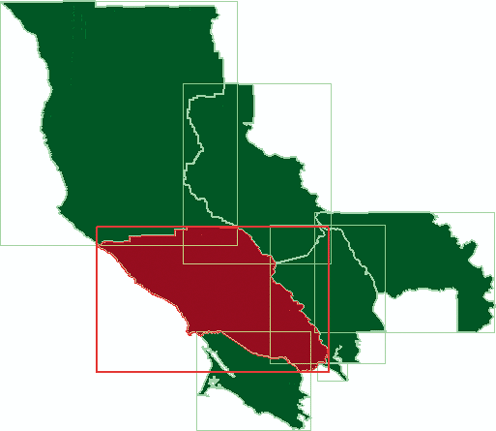

The query in Example 13-5 compares the bounding box of Sonoma County with the shapes of the other bounding boxes. Figure 13-2 shows the shapes and their bounding boxes. Notice how they overlap. When there is an overlap between Sonoma County’s bounding box (shown in red) and the shape of another (shown in green), that other county is selected as a match.

Using bounding boxes this way makes spatial querying much more efficient. PostGIS doesn’t have to do a lot of complex calculations for every vertex or line of every polygon. Instead, it does a rough check using the bounding box rectangles. This uses less memory and is processed much faster.

This exercise is supposed to show which counties bordered Sonoma County. If you study Figure 13-2, you will notice that one county isn’t an adjacent neighbor but its bounding box overlaps Sonoma County’s bounding box. This is Yolo County, highlighted in Figure 13-3.

The && operator is

intended to quickly check the general location of shapes. It can’t

tell you that two shapes are adjacent, but only if they are close to

one another. If two shapes don’t have overlapping bounding boxes,

they will not be adjacent. This function is helpful when doing

spatial queries because it allows further analysis by PostGIS to

focus only on the shapes that might overlap.

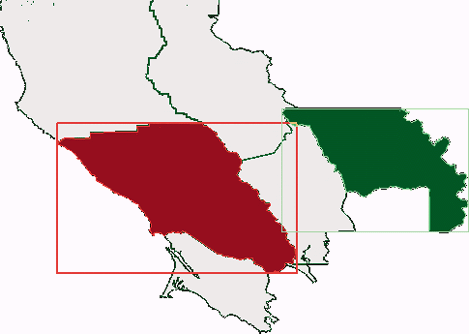

To take the query example one step further, the PostGIS

Distance() function must be used

to determine how close the counties actually are. Example 13-6 is almost

identical to Example

13-5 but includes one more WHERE clause.

#SELECT a.county#FROM countyp020 a,#countyp020 b#WHERE b.county = 'Sonoma County'#AND a.wkb_geometry && b.wkb_geometry#AND distance(a.wkb_geometry, b.wkb_geometry) = 0;county ---------------------------------------------------- Sonoma County Napa County Lake County Mendocino County Marin County Solano County (6 rows)

The only difference is the last line:

AND distance(a.wkb_geometry, b.wkb_geometry) = 0;The distance function

requires two sets of geometry features as parameters. PostGIS

calculates the minimum distance between the features in the a.wkb_geometry and b.wkb_geometry columns. If there are any

shapes that don’t share the same border as Sonoma County, they are

rejected.

Because the &&

operator is still being used, the distance function is used only to compare

the seven features returned by the query in Example 13-5. The resulting

set of features are shown on a map in Figure 13-4. Yolo County is

no longer part of the result set.

Planning to visualize query results

If you plan to visualize your results, you can create a view

or table with the results of your query. To create a view of the

query in Example 13-6,

you need to add the CREATE

VIEW

<view

name> AS keywords to the beginning of the SQL

statement and wrap your command with parenthesis like this:

#CREATE VIEW mycounties AS(SELECT a.county......=0);

This view can be accessed just like any table by referring to

the name of the view mycounties,

instead of the name of a table.

You will also need to make sure to include the geometry

results in a column of the query. Earlier examples listed only

tabular data, but in order to produce graphics, you need to have a

geometry column in your query results. For example, you can modify

the SELECT a.county statement in Example 13-6, by adding the

geometry column from table a:

# SELECT a.county, a.wkb_geometry