Now, let's refactor the threadProc function and synchronize the critical section that modifies and accesses the balance. We need a locking mechanism that will only allow one thread to either read or write the balance. The C++ thread support library offers an apt lock called mutex. The mutex lock is an exclusive lock that will only allow one thread to operate the critical section code within the same process boundary. Until the thread that has acquired the lock releases the mutex lock, all other threads will have to wait for their turn. Once a thread acquires the mutex lock, the thread can safely access the shared resource.

The main.cpp file can be refactored as follows; the changes are highlighted in bold:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

#include "Account.h"

using namespace std;

enum ThreadType {

DEPOSITOR,

WITHDRAWER

};

mutex locker;

Account account(5000.00);

void threadProc ( ThreadType typeOfThread ) {

while ( 1 ) {

switch ( typeOfThread ) {

case DEPOSITOR: {

locker.lock();

cout << "Account balance before the deposit is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

account.deposit( 2000.00 );

cout << "Account balance after deposit is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

locker.unlock();

this_thread::sleep_for( 1s );

}

break;

case WITHDRAWER: {

locker.lock();

cout << "Account balance before withdrawing is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

account.deposit( 1000.00 );

cout << "Account balance after withdrawing is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

locker.unlock();

this_thread::sleep_for( 1s );

}

break;

}

}

}

int main( ) {

thread depositor ( threadProc, ThreadType::DEPOSITOR );

thread withdrawer ( threadProc, ThreadType::WITHDRAWER );

depositor.join();

withdrawer.join();

return 0;

}

You may have noticed that the mutex is declared in the global scope. Ideally, we could have declared the mutex inside a class as a static member as opposed to a global variable. As all the threads are supposed to be synchronized by the same mutex, ensure that you use either a global mutex lock or a static mutex lock as a class member.

The refactored threadProc in main.cpp source file looks as follows; the changes are highlighted in bold:

void threadProc ( ThreadType typeOfThread ) {

while ( 1 ) {

switch ( typeOfThread ) {

case DEPOSITOR: {

locker.lock();

cout << "Account balance before the deposit is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

account.deposit( 2000.00 );

cout << "Account balance after deposit is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

locker.unlock();

this_thread::sleep_for( 1s );

}

break;

case WITHDRAWER: {

locker.lock();

cout << "Account balance before withdrawing is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

account.deposit( 1000.00 );

cout << "Account balance after withdrawing is "

<< account.getBalance() << endl;

locker.unlock();

this_thread::sleep_for( 1s );

}

break;

}

}

}

The code that is wrapped between lock() and unlock() is the critical section that is synchronized by the mutex lock.

As you can see, there are two critical section blocks in the threadProc function, so it is important to understand that only one thread can enter the critical section. For instance, if the depositor thread has entered its critical section, then the withdrawal thread has to wait until the depositor thread releases the lock and vice versa.

Technically speaking, we could replace all the raw lock() and unlock() mutex methods with lock_guard as this ensures the mutex is always unlocked even if the critical section block of the code throws an exception. This will avoid starving and deadlock scenarios.

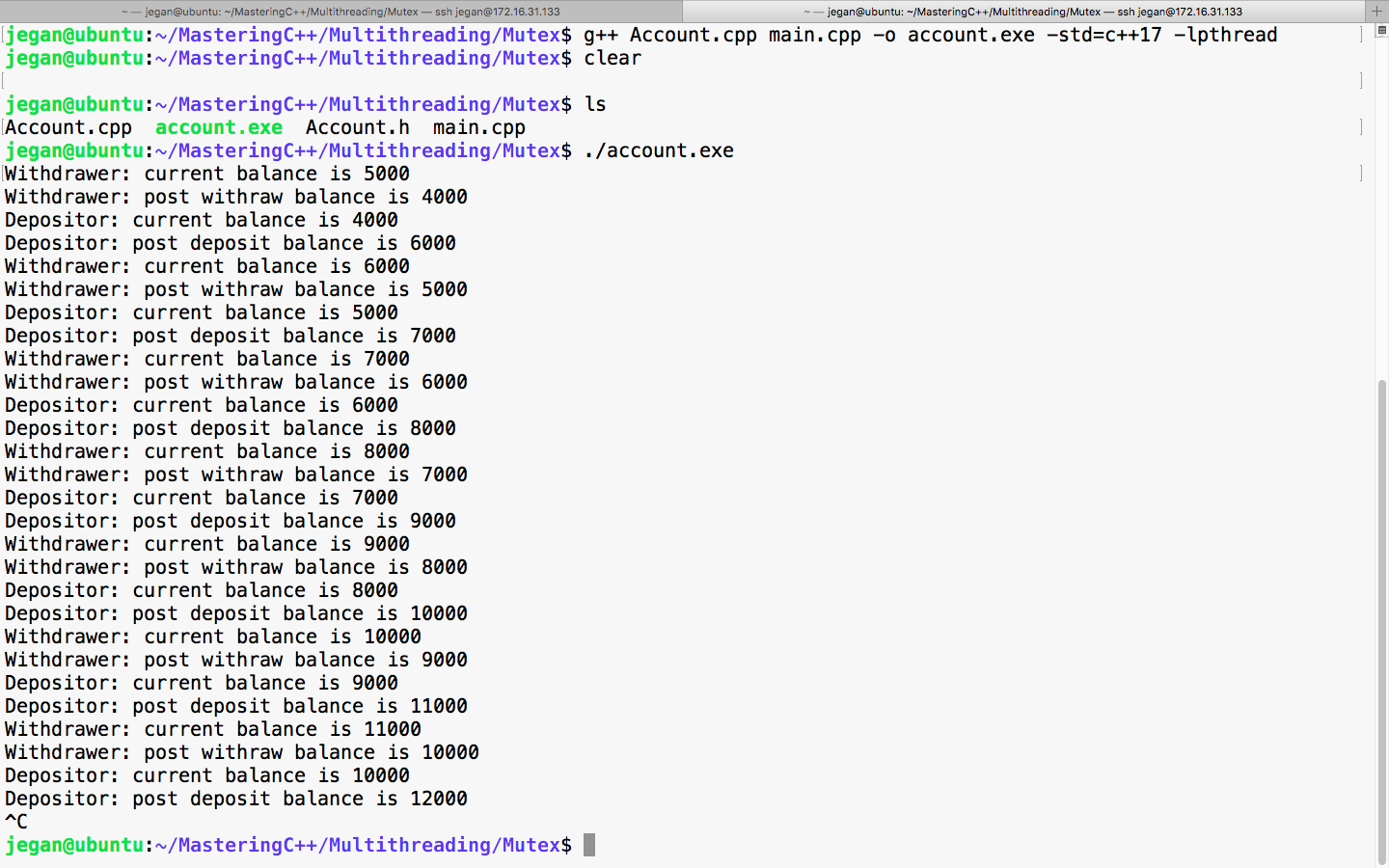

It is time to check the output of our refactored program:

Great, did you check the balance reported by DEPOSITOR and WITHDRAWER threads? Yep, they are always consistent, aren't they? Yes, the output confirms that the code is synchronized and it is thread-safe now.

Though our code is functionally correct, there is room for improvement. Let's refactor the code to make it object-oriented and efficient.

Let's reuse the Thread class and abstract all the thread-related stuff inside the Thread class and get rid of the global variables and threadProc.

To start with, let's observe the refactored Account.h header, as follows:

#ifndef __ACCOUNT_H

#define __ACCOUNT_H

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Account {

private:

double balance;

public:

Account( double balance );

double getBalance();

void deposit(double amount);

void withdraw(double amount);

};

#endif

As you can see, the Account.h header hasn't changed as it already looks clean.

The respective Account.cpp source file looks as follows:

#include "Account.h"

Account::Account(double balance) {

this->balance = balance;

}

double Account::getBalance() {

return balance;

}

void Account::withdraw(double amount) {

if ( balance < amount ) {

cout << "Insufficient balance, withdraw denied." << endl;

return;

}

balance = balance - amount;

}

void Account::deposit(double amount) {

balance = balance + amount;

}

It is better if the Account class is separated from the thread-related functionalities to keep things neat. Also, let's understand how the Thread class that we wrote could be refactored to use the mutex synchronization mechanism as shown ahead:

#ifndef __THREAD_H

#define __THREAD_H

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

using namespace std;

#include "Account.h"

enum ThreadType {

DEPOSITOR,

WITHDRAWER

};

class Thread {

private:

thread *pThread;

Account *pAccount;

static mutex locker;

ThreadType threadType;

bool stopped;

void run();

public:

Thread(Account *pAccount, ThreadType typeOfThread);

~Thread();

void start();

void stop();

void join();

void detach();

};

#endif

In the Thread.h header file shown previously, a couple of changes are done as part of refactoring. As we would like to synchronize the threads using a mutex, the Thread class includes the mutex header of the C++ thread support library. As all the threads are supposed to use the same mutex lock, the mutex instance is declared static. Since all the threads are going to share the same Account object, the Thread class has a pointer to the Account object as opposed to a stack object.

The Thread::run() method is the Thread function that we are going to supply to the Thread class constructor of the C++ thread support library. As no one is expected to invoke the run method directly, the run method is declared private. As per our Thread class design, which is similar to Java and Qt, the client code would just invoke the start method; when the OS scheduler gives a green signal to run, the run thread procedure will be called automatically. Actually, there is no magic here since the run method address is registered as a Thread function at the time of creating the thread.

The Thread.cpp source can be refactored as follows:

#include "Thread.h"

mutex Thread::locker;

Thread::Thread(Account *pAccount, ThreadType typeOfThread) {

this->pAccount = pAccount;

pThread = NULL;

stopped = false;

threadType = typeOfThread;

}

Thread::~Thread() {

delete pThread;

pThread = NULL;

}

void Thread::run() {

while(1) {

switch ( threadType ) {

case DEPOSITOR:

locker.lock();

cout << "Depositor: current balance is " << pAccount->getBalance() << endl;

pAccount->deposit(2000.00);

cout << "Depositor: post deposit balance is " << pAccount->getBalance() << endl;

locker.unlock();

this_thread::sleep_for(1s);

break;

case WITHDRAWER:

locker.lock();

cout << "Withdrawer: current balance is " <<

pAccount->getBalance() << endl;

pAccount->withdraw(1000.00);

cout << "Withdrawer: post withraw balance is " <<

pAccount->getBalance() << endl;

locker.unlock();

this_thread::sleep_for(1s);

break;

}

}

}

void Thread::start() {

pThread = new thread( &Thread::run, this );

}

void Thread::stop() {

stopped = true;

}

void Thread::join() {

pThread->join();

}

void Thread::detach() {

pThread->detach();

}

The threadProc function that was there in main.cpp has moved inside the Thread class's run method. After all, the main function or the main.cpp source file isn't supposed to have any kind of business logic, hence they are refactored to improve the code quality.

Now let's see how clean is the main.cpp source file after refactoring:

#include "Account.h"

#include "Thread.h"

int main( ) {

Account account(5000.00);

Thread depositor ( &account, ThreadType::DEPOSITOR );

Thread withdrawer ( &account, ThreadType::WITHDRAWER );

depositor.start();

withdrawer.start();

depositor.join();

withdrawer.join();

return 0;

}

The previously shown main() function and the overall main.cpp source file looks short and simple without any nasty complex business logic hanging around.