A good design will be strongly cohesive and loosely coupled. Hence, our design must have less dependency. A design that makes a code dependent on many other objects or modules is considered a poor design. If Dependency Inversion (DI) is violated, any change that happens in the dependent modules will have a bad impact on our module, leading to a ripple effect.

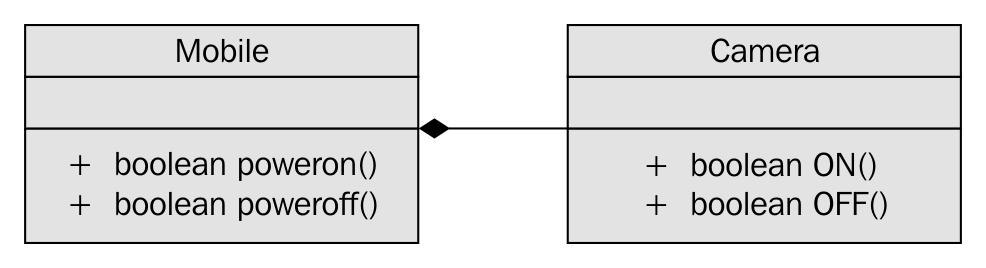

Let's take a simple example to understand the power of DI. A Mobile class "has a" Camera object and notice that has a form is composition. Composition is an exclusive ownership where the lifetime of the Camera object is directly controlled by the Mobile object:

As you can see in the preceding image, the Mobile class has an instance of Camera and the has a form used is composition, which is an exclusive ownership relationship.

Let's take a look at the Mobile class implementation, as follows:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Mobile {

private:

Camera camera;

public:

Mobile ( );

bool powerOn();

bool powerOff();

};

class Camera {

public:

bool ON();

bool OFF();

};

bool Mobile::powerOn() {

if ( camera.ON() ) {

cout << "\nPositive Logic - assume some complex Mobile power ON logic happens here." << endl;

return true;

}

cout << "\nNegative Logic - assume some complex Mobile power OFF logic happens here." << endl;

<< endl;

return false;

}

bool Mobile::powerOff() {

if ( camera.OFF() ) {

cout << "\nPositive Logic - assume some complex Mobile power OFF logic happens here." << endl;

return true;

}

cout << "\nNegative Logic - assume some complex Mobile power OFF logic happens here." << endl;

return false;

}

bool Camera::ON() {

cout << "\nAssume Camera class interacts with Camera hardware here\n" << endl;

cout << "\nAssume some Camera ON logic happens here" << endl;

return true;

}

bool Camera::OFF() {

cout << "\nAssume Camera class interacts with Camera hardware here\n" << endl;

cout << "\nAssume some Camera OFF logic happens here" << endl;

return true;

}

In the preceding code, Mobile has implementation-level knowledge about Camera, which is a poor design. Ideally, Mobile should be interacting with Camera via an interface or an abstract class with pure virtual functions, as this separates the Camera implementation from its contract. This approach helps replace Camera without affecting Mobile and also gives an opportunity to support a bunch of Camera subclasses in place of one single camera.

Wondering why it is called Dependency Injection (DI) or Inversion of Control (IOC)? The reason it is termed dependency injection is that currently, the lifetime of Camera is controlled by the Mobile object; that is, Camera is instantiated and destroyed by the Mobile object. In such a case, it is almost impossible to unit test Mobile in the absence of Camera, as Mobile has a hard dependency on Camera. Unless Camera is implemented, we can't test the functionality of Mobile, which is a bad design approach. When we invert the dependency, it lets the Mobile object use the Camera object while it gives up the responsibility of controlling the lifetime of the Camera object. This process is rightly referred to as IOC. The advantage is that you will be able to unit test the Mobile and Camera objects independently and they will be strongly cohesive and loosely coupled due to IOC.

Let's refactor the preceding code with the DI design principle:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class ICamera {

public:

virtual bool ON() = 0;

virtual bool OFF() = 0;

};

class Mobile {

private:

ICamera *pCamera;

public:

Mobile ( ICamera *pCamera );

void setCamera( ICamera *pCamera );

bool powerOn();

bool powerOff();

};

class Camera : public ICamera {

public:

bool ON();

bool OFF();

};

//Constructor Dependency Injection

Mobile::Mobile ( ICamera *pCamera ) {

this->pCamera = pCamera;

}

//Method Dependency Injection

Mobile::setCamera( ICamera *pCamera ) {

this->pCamera = pCamera;

}

bool Mobile::powerOn() {

if ( pCamera->ON() ) {

cout << "\nPositive Logic - assume some complex Mobile power ON logic happens here." << endl;

return true;

}

cout << "\nNegative Logic - assume some complex Mobile power OFF logic happens here." << endl;

<< endl;

return false;

}

bool Mobile::powerOff() {

if ( pCamera->OFF() ) {

cout << "\nPositive Logic - assume some complex Mobile power OFF logic happens here." << endl;

return true;

}

cout << "\nNegative Logic - assume some complex Mobile power OFF logic happens here." << endl;

return false;

}

bool Camera::ON() {

cout << "\nAssume Camera class interacts with Camera hardware here\n" << endl;

cout << "\nAssume some Camera ON logic happens here" << endl;

return true;

}

bool Camera::OFF() {

cout << "\nAssume Camera class interacts with Camera hardware here\n" << endl;

cout << "\nAssume some Camera OFF logic happens here" << endl;

return true;

}

The changes are highlighted in bold in the preceding code snippet. IOC is such a powerful technique that it lets us decouple the dependency as just demonstrated; however, its implementation is quite simple.