sudo apt install ruby-dev

BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI

BIRMINGHAM - MUMBAI

Copyright © 2017 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: August 2017

Production reference: 1300817

ISBN 978-1-78646-162-9

|

Author Jeganathan Swaminathan |

Copy Editor Gladson Monteiro Muktikant Garimella |

|

Reviewer Brandon James |

Project Coordinator Vaidehi Sawant |

|

Commissioning Editor

Aaron Lazar |

Proofreader Safis Editing |

|

Acquisition Editor Denim Pinto |

Indexer Rekha Nair |

|

Content Development Editor Anurag Ghogre |

Graphics Abhinash Sahu |

|

Technical Editor Madhunikita Sunil Chindarkar |

Production Coordinator Melwyn Dsa |

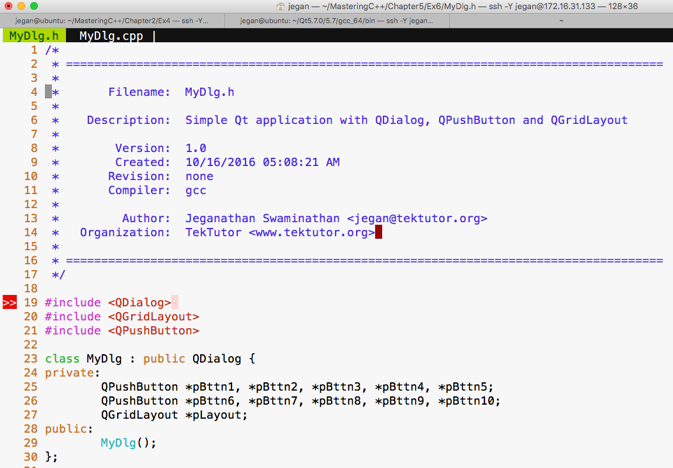

Jeganathan Swaminathan, Jegan for short, is a freelance software consultant and founder of TekTutor, with over 17 years of IT industry experience. In the past, he has worked for AMD, Oracle, Siemens, Genisys Software, Global Edge Software Ltd, and PSI Data Systems. He has consulted for Samsung WTD (South Korea) and National Semiconductor (Bengaluru). He now works as a freelance external consultant for Amdocs (India). He works as freelance software consultant and freelance corporate trainer. He holds CSM, CSPO, CSD, and CSP certifications from Scrum Alliance. He is a polyglot software professional and his areas of interest include a wide range of C++, C#, Python, Ruby, AngularJS, Node.js, Kubernetes, Ansible, Puppet, Chef, and Java technologies. He is well known for JUnit, Mockito, PowerMock, gtest, gmock, CppUnit, Cucumber, SpecFlow, Qt, QML, POSIX – Pthreads, TDD, BDD, ATDD, NoSQL databases (MongoDB and Cassandra), Apache Spark, Apache Kafka, Apache Camel, Dockers, Continuous Integration (CI), Continuous Delivery (CD), Maven, Git, cloud computing, and DevOps. You can reach him for any C++, Java, Qt, QML, TDD, BDD, and DevOps-related training or consulting assignments. Jegan is a regular speaker at various technical conferences.

Brandon James is a support escalation engineer who works with troubleshooting, debugging, and implementing identity management solutions for many enterprise customers for both on-premise and cloud solutions. He worked as a technical reviewer on the Microsoft Identity Manager 2016 Handbook by Packt Publishing. Previously, he worked as a Web Site/Web Application Developer designing and developing websites and internal web applications for various enterprise customers. He holds a B.S. in computer engineering and an M.S. in computer science.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com. Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details. At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Get the most in-demand software skills with Mapt. Mapt gives you full access to all Packt books and video courses, as well as industry-leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career.

Thanks for purchasing this Packt book. At Packt, quality is at the heart of our editorial process. To help us improve, please leave us an honest review on this book's Amazon page at https://www.amazon.com/dp/1786461625.

If you'd like to join our team of regular reviewers, you can email us at customerreviews@packtpub.com. We award our regular reviewers with free eBooks and videos in exchange for their valuable feedback. Help us be relentless in improving our products!

C++ is an interesting programming language that has been around for almost three decades now. It is used to develop complex desktop applications, web applications, networking applications, device drivers, kernel modules, embedded applications, and GUI applications using third-party widget frameworks; literally speaking, C++ can be used in any domain.

Ever since I started programming in 1993, I have cherished the good old technical discussions that I had with many of my colleagues and industry experts that I met from time to time. Of all the technical discussions, one topic gets repeated time and again, which is, "Do you think C++ is a relevant programming language today? Should I continue working on C++ or should I move on to other modern programming languages, such as Java, C#, Scala, or Angular/Node.js?"

I have always felt that one should be open to learning other technologies, but that doesn’t mean having to give up on C++. However, the good news is that with the new C++17 features in place, C++ has been reborn and it is going to stay and rock for many more decades, which is my motivation to write this book.

People have always felt that Java will take over C++, but it has continued to stay. The same discussion started again when C# came into the industry and today again when Angular/Node.js and Scala seem to be more attractive for rapid programming. However, C++ has its own, place and no programming language has been able to take over the place of C++ so far.

There are already many C++ books that help you understand the language, but there are very few books that address developing GUI applications in C++, TDD with C++, and BDD with C++.

C++ has come a long way and has now been adopted in several contexts. Its key strengths are its software infrastructure and resource-constrained applications. The C++ 17 release will change the way developers write code, and this book will help you master your developing skills with C++.

With real-world, practical examples explaining each concept, the book will begin by introducing you to the latest features of C++ 17. It will encourage clean code practices in C++, and demonstrate GUI app development options in C++. You will gain insights into how to avoid memory leaks using smart pointers. Next, you will learn how multithreaded programming can help you achieve concurrency in your applications.

Moving on, you’ll also get an in-depth understanding of the C++ Standard Template Library. We'll explain the concepts of implementing TDD and BDD in your C++ programs, along with template-based generic programming, to equip you with the expertise to build powerful applications. Finally, we’ll round the book off with debugging techniques and best practices. By the time you reach the end of the book, you will have an in-depth understanding of the language and its various facets.

Chapter 1, C++17 Features, explains the new features of C++17 and features that have been removed. It also demonstrates key C++17 features with easy-to-understand examples.

Chapter 2, Standard Template Library, gives an overview of STL, demonstrates various containers and iterators, and explains how to apply useful algorithms on the containers. The chapter also touches on the internal data structures used and their runtime efficiencies.

Chapter 3, Template Programming, gives an overview of generic programming and its benefits. It demonstrates writing function templates and class templates, and overloading function templates. It also touches upon writing generic classes, explicit class specializations, and partial specializations.

Chapter 4, Smart Pointers, explains the issues of using raw pointers and motivates the use of smart pointers. Gradually, this chapter introduces you to the usage of auto_ptr, unique_ptr, shared_ptr, and weak_ptr, and explains ways to resolve cyclic dependency issues.

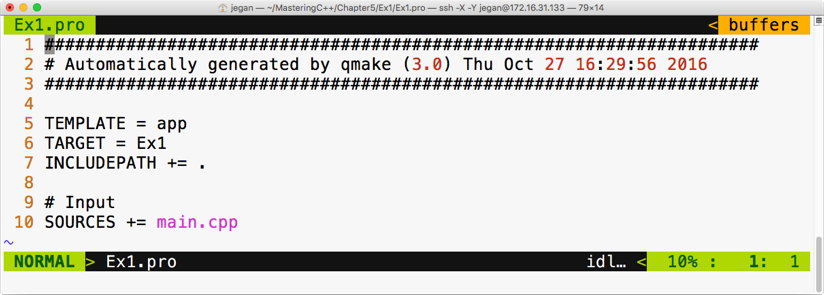

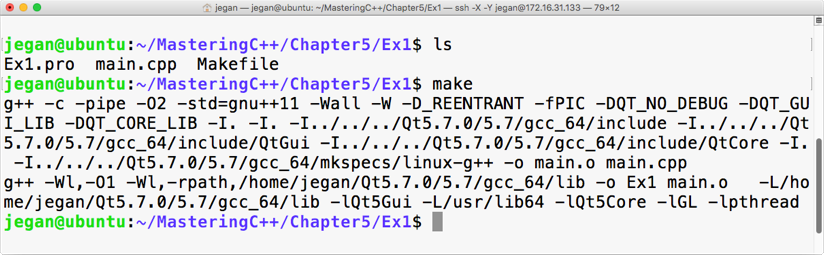

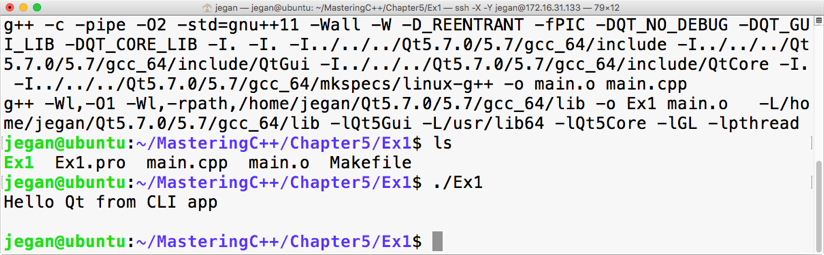

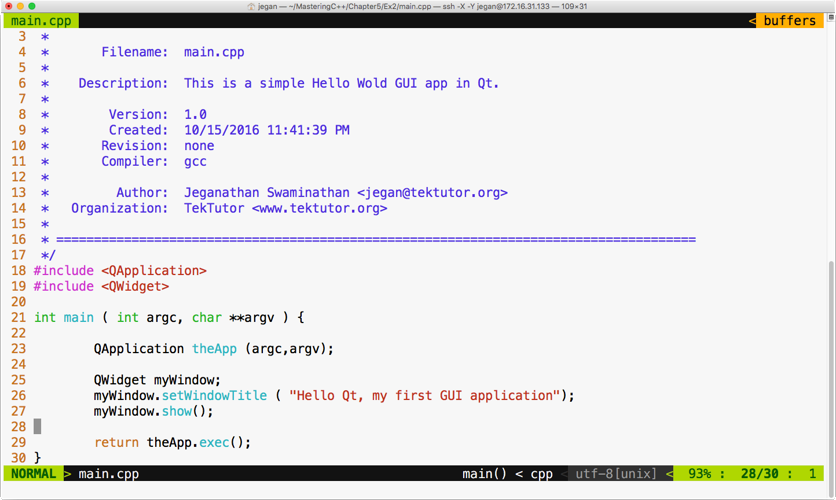

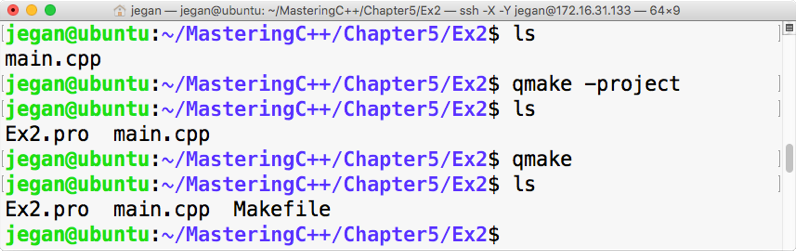

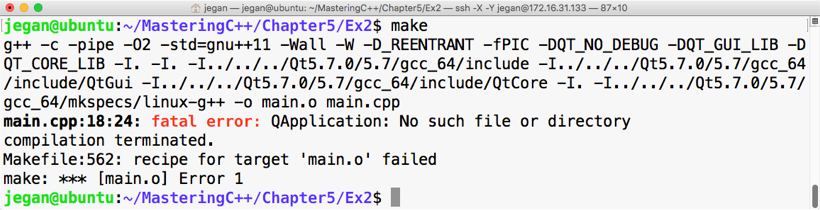

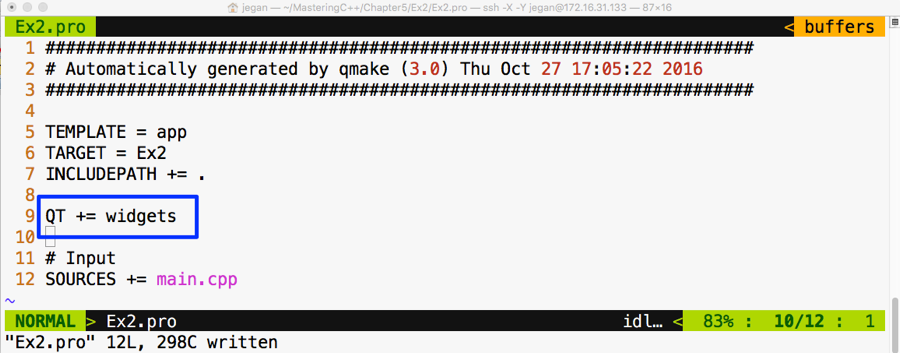

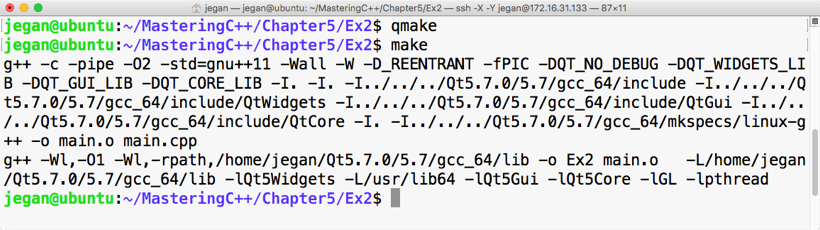

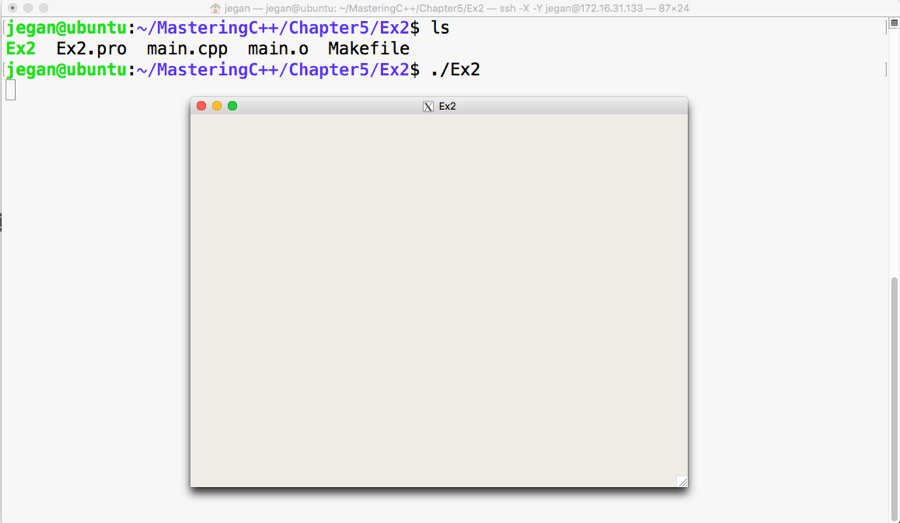

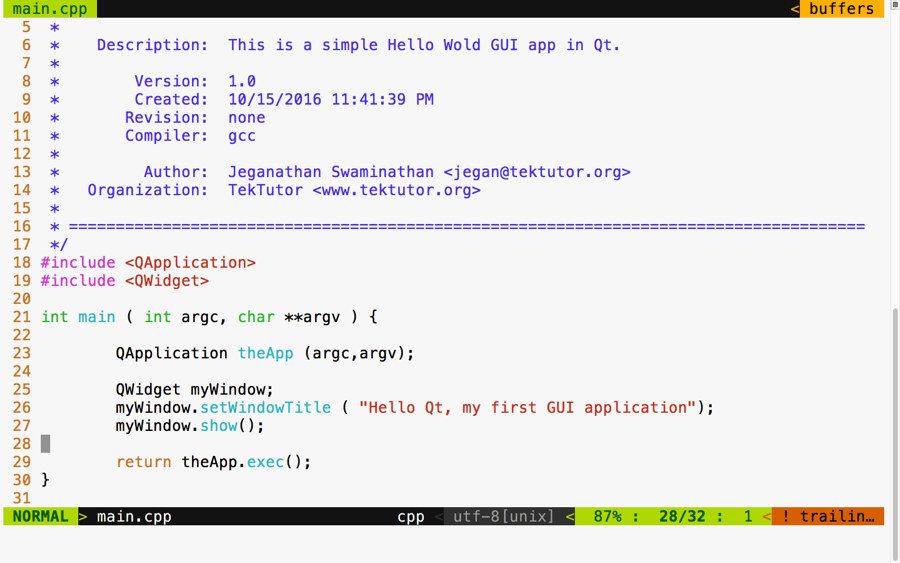

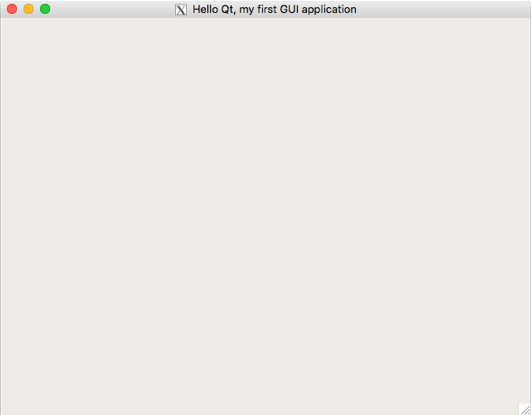

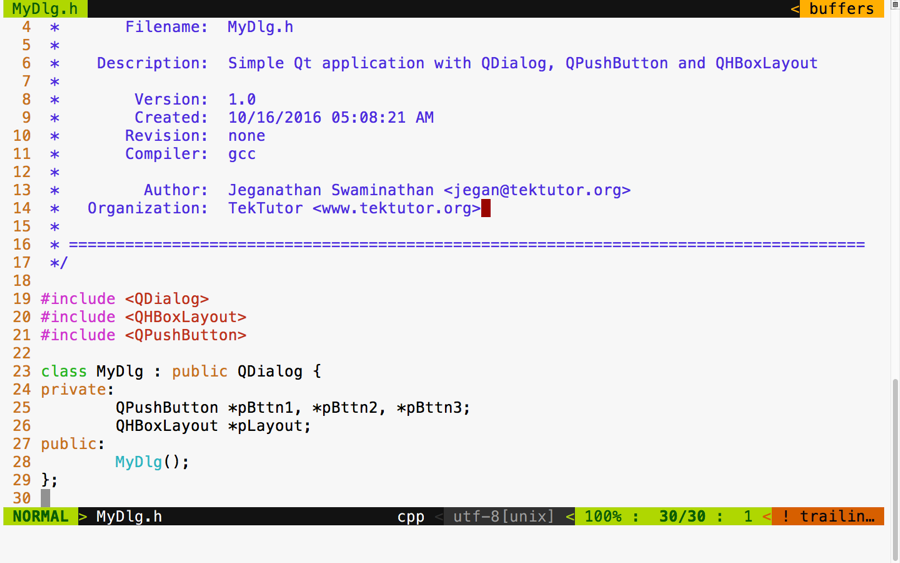

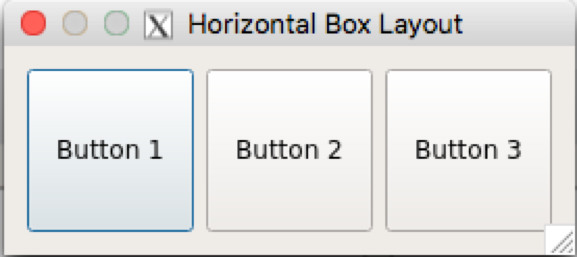

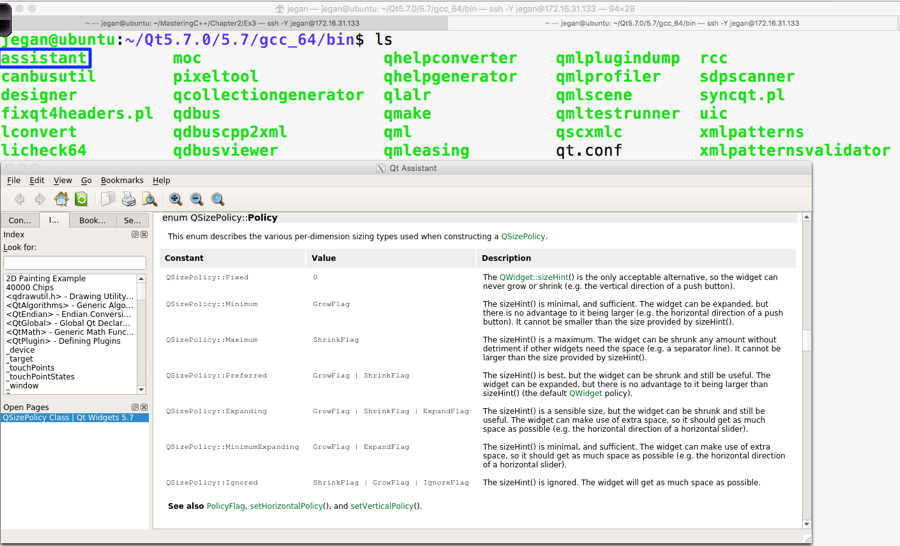

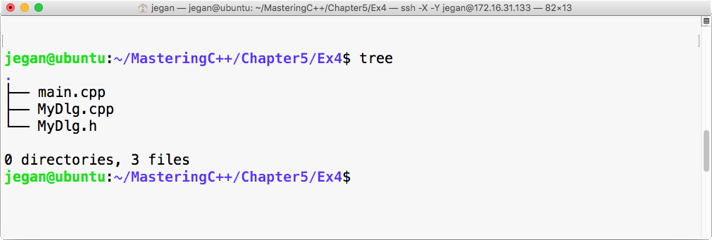

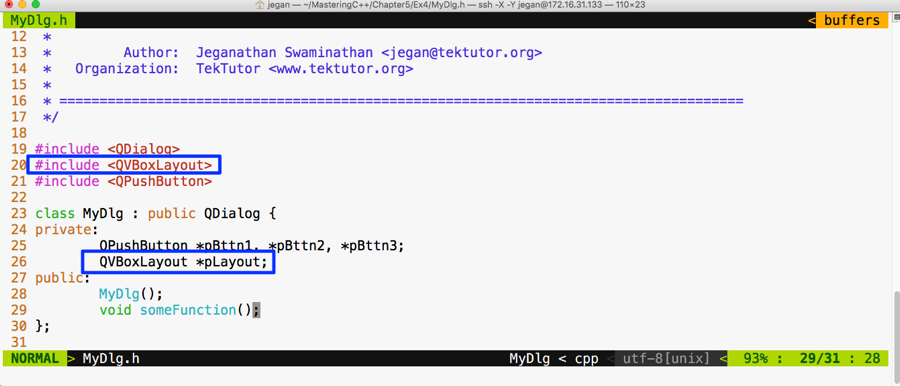

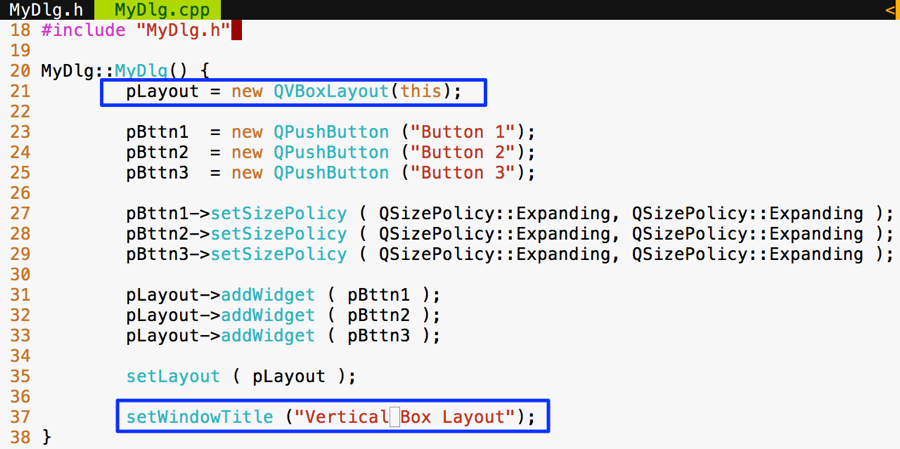

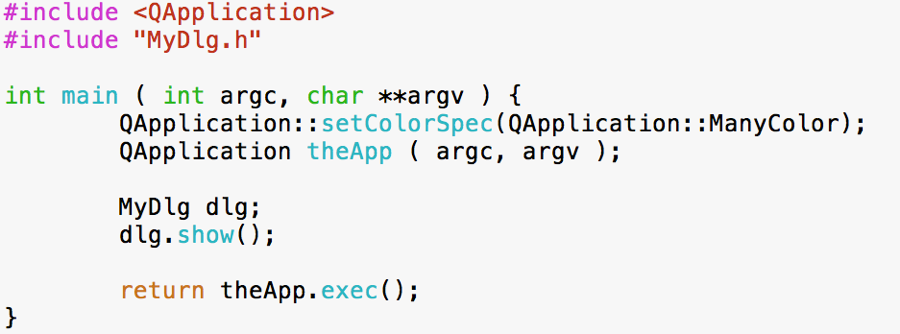

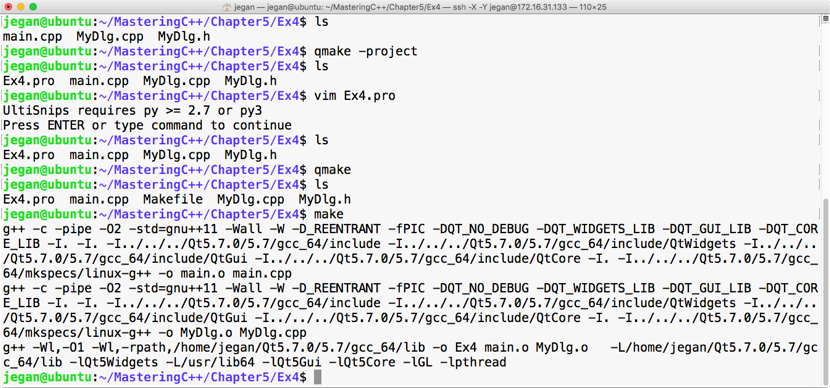

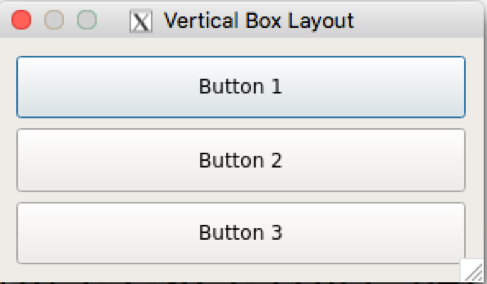

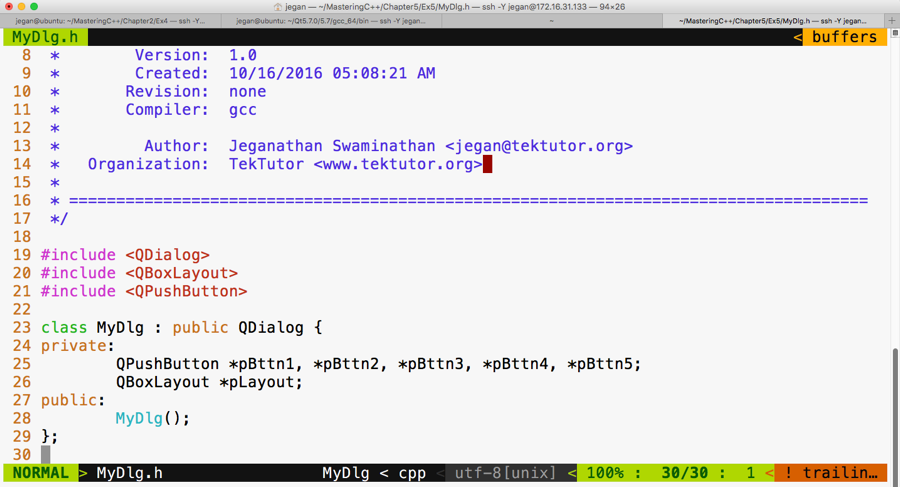

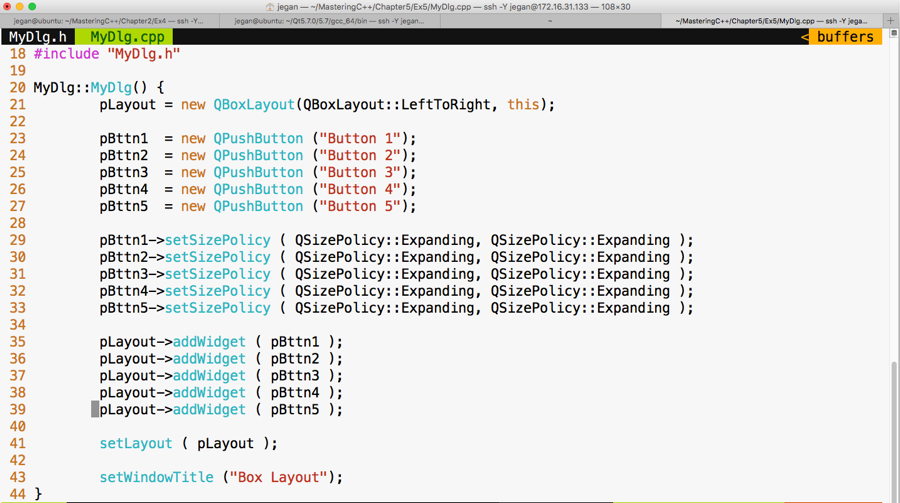

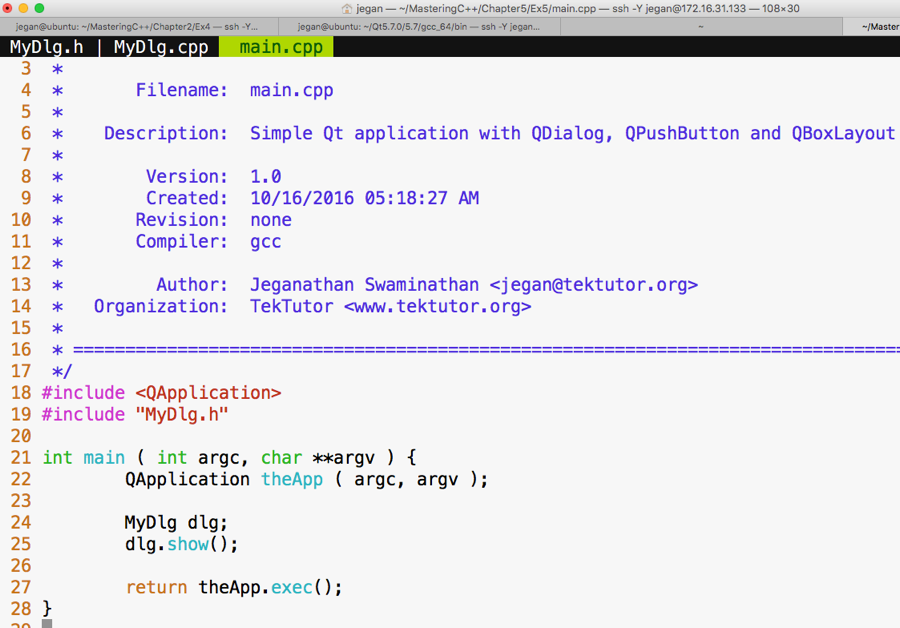

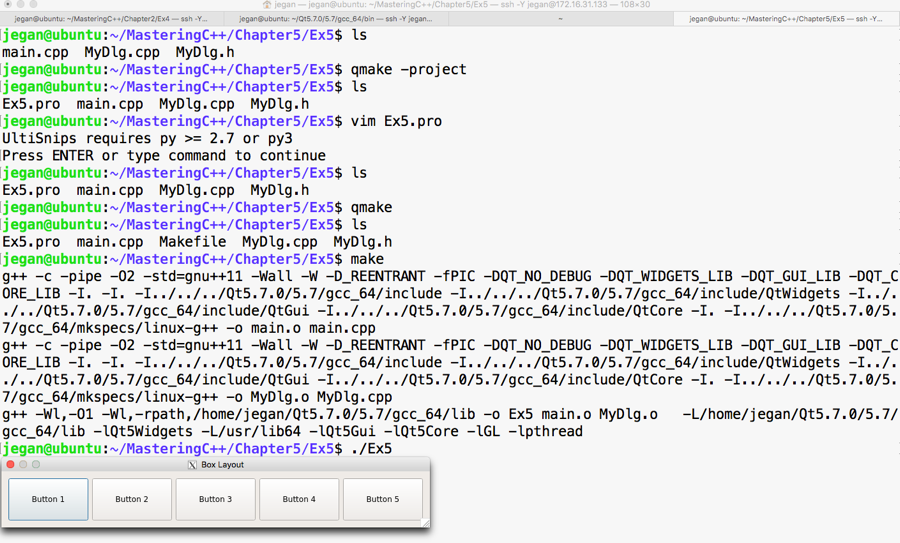

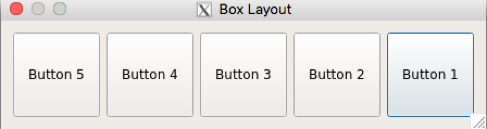

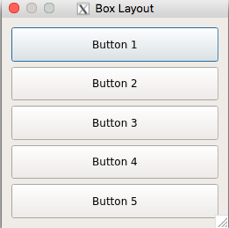

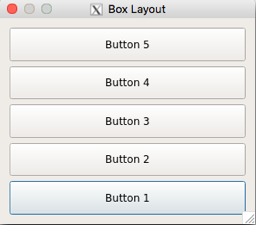

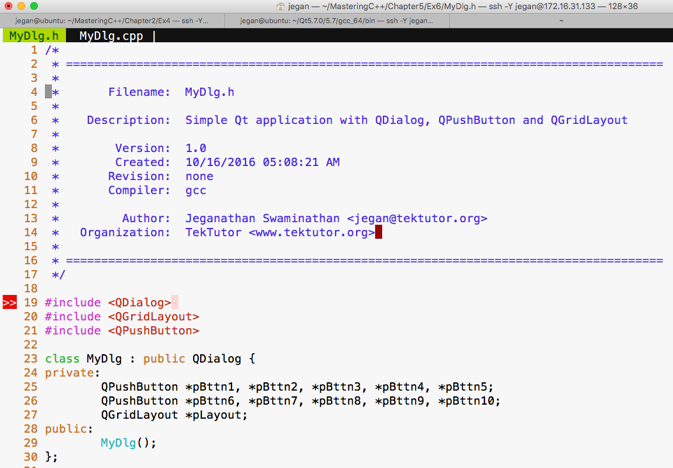

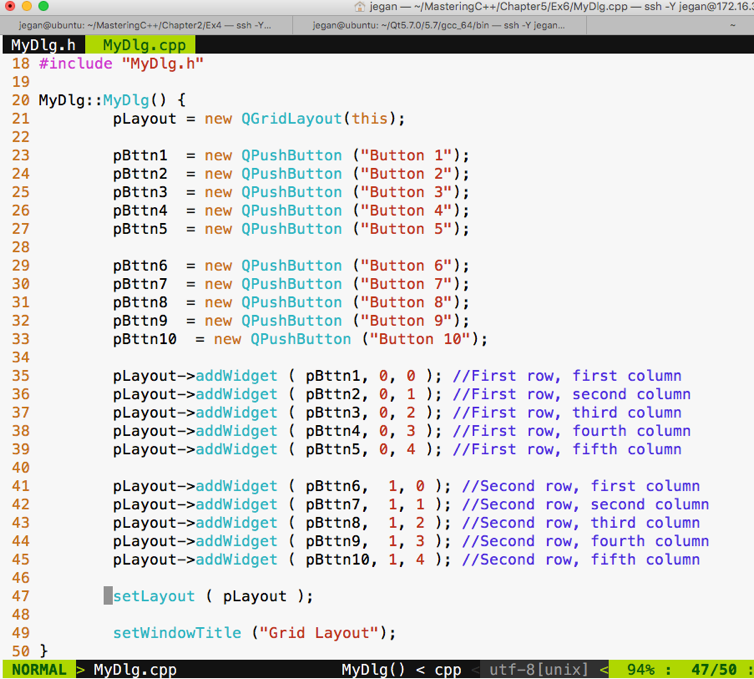

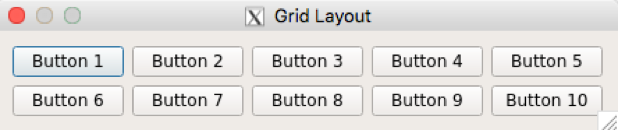

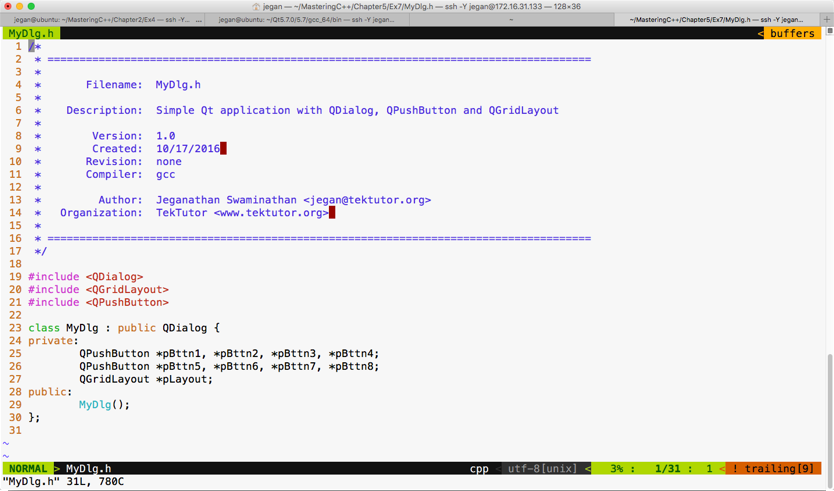

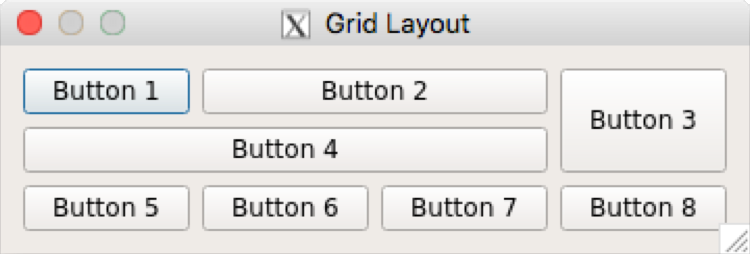

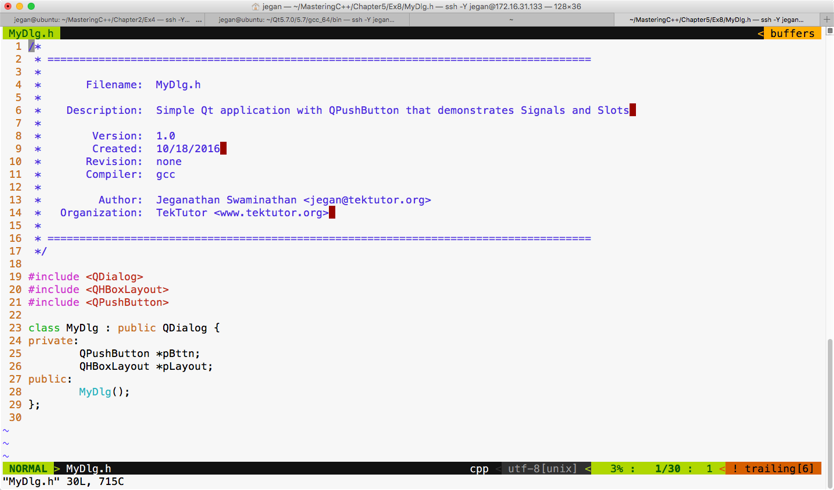

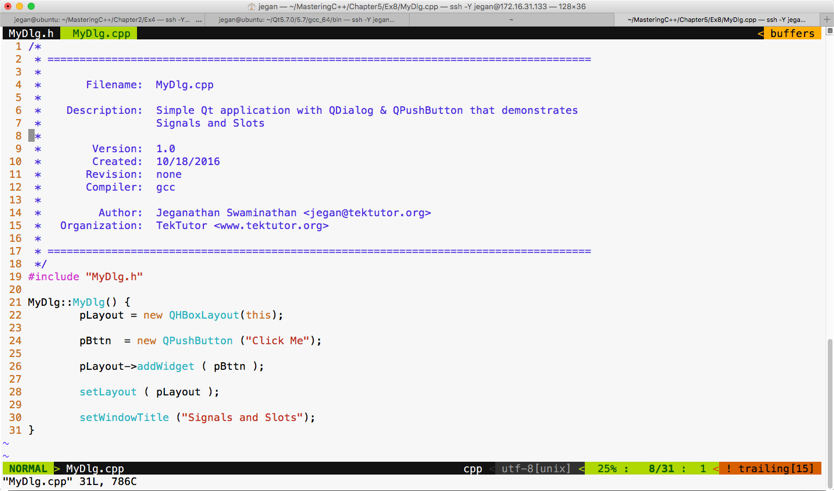

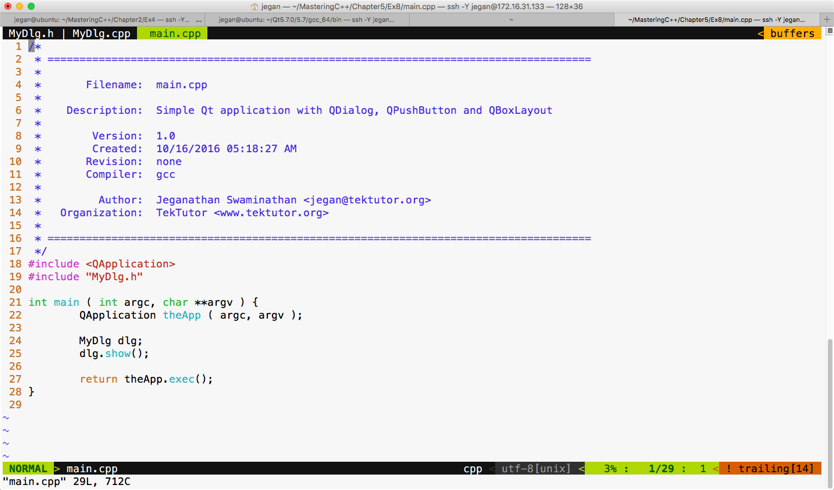

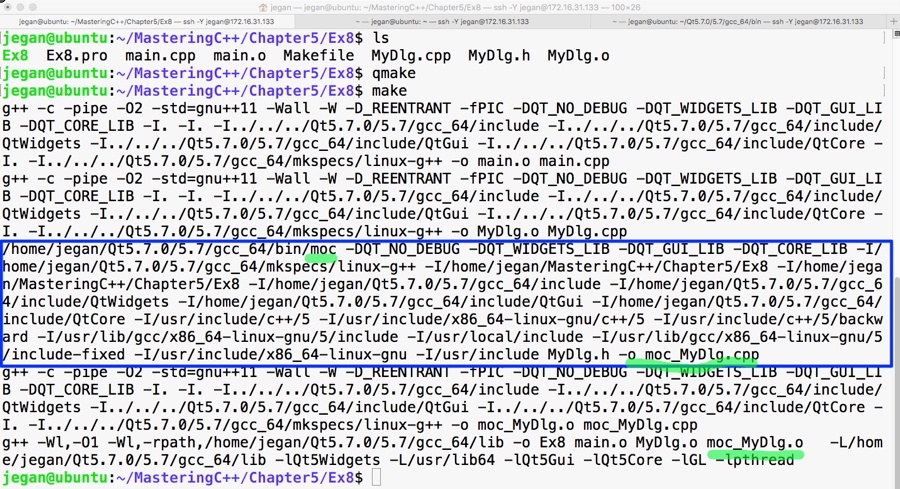

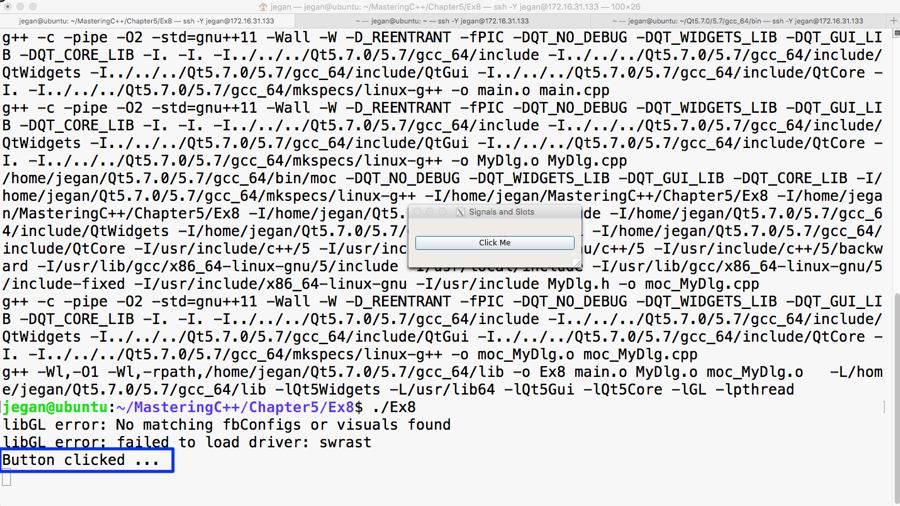

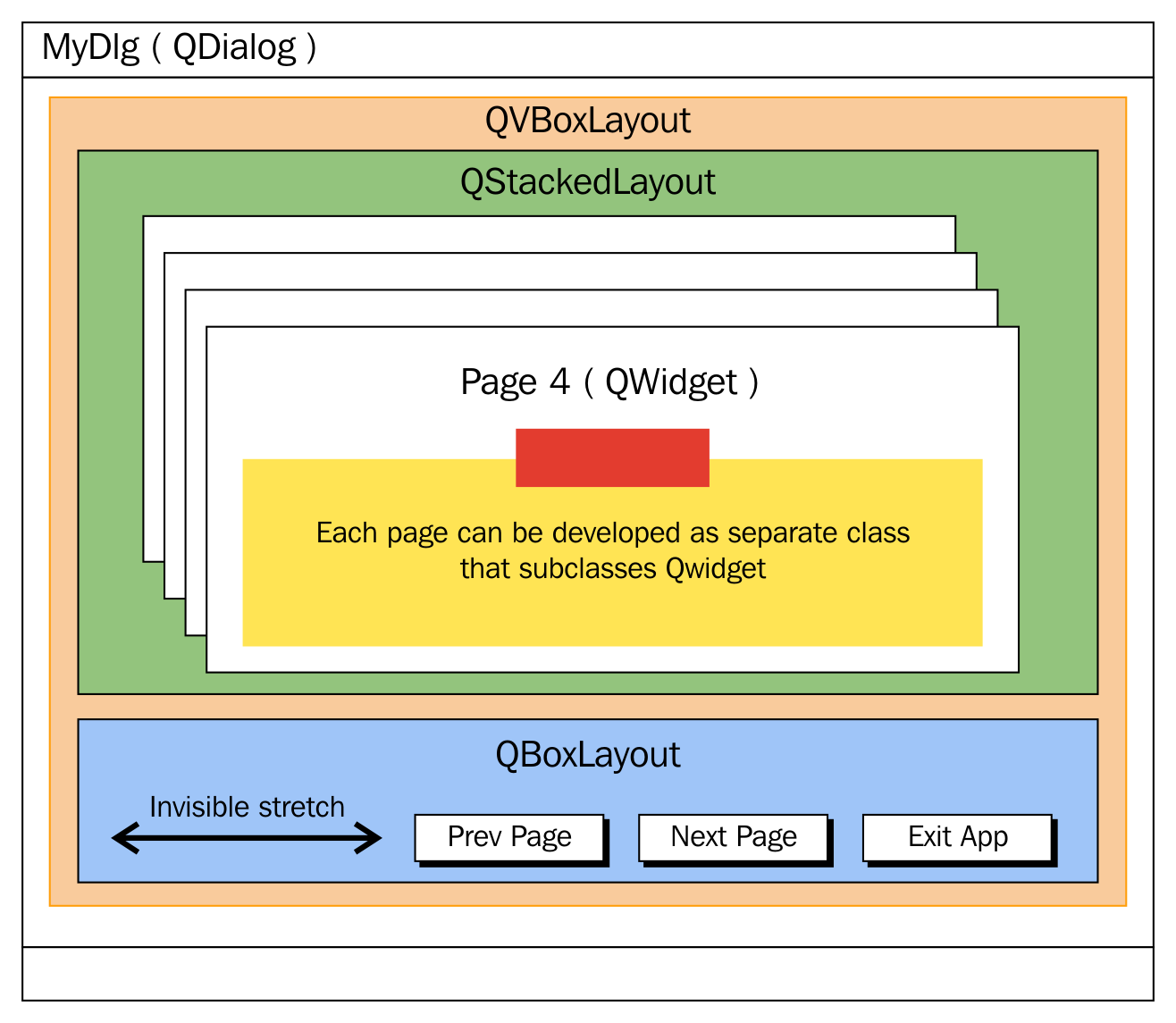

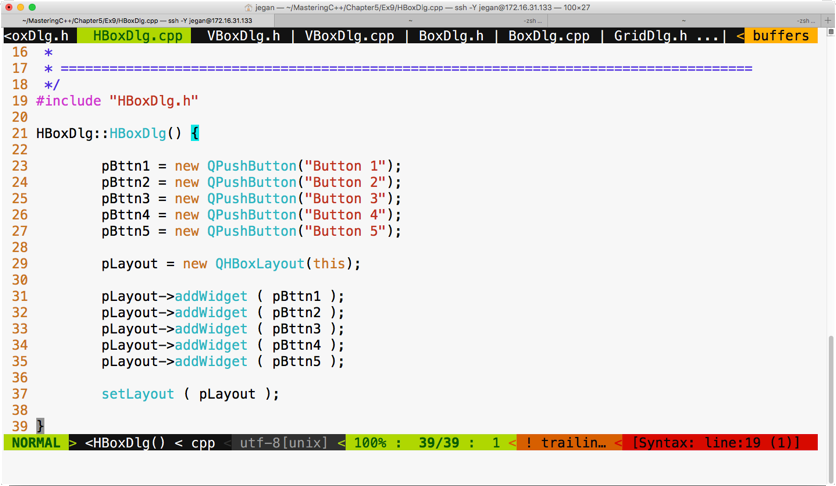

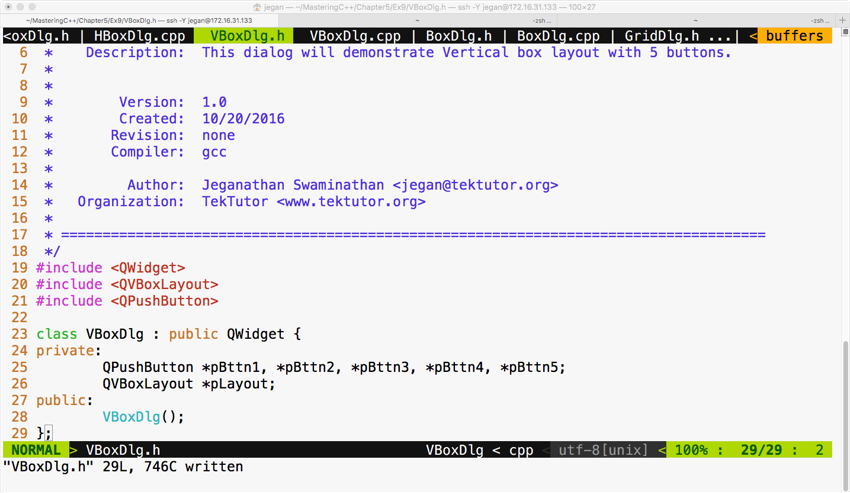

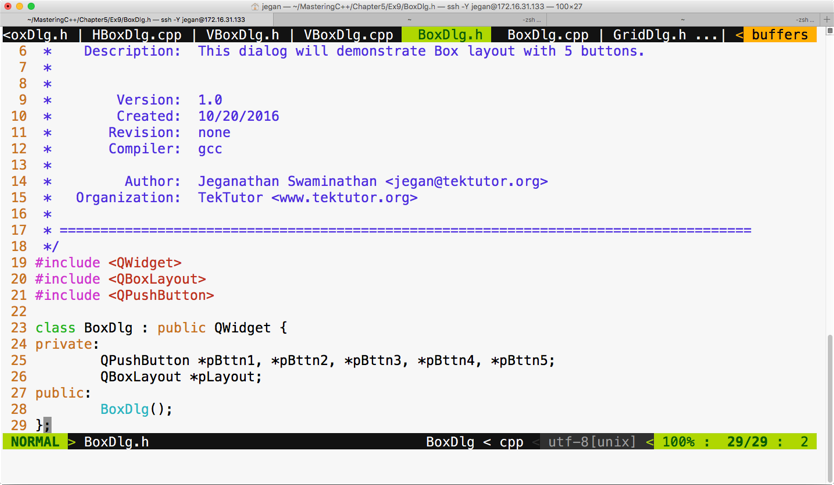

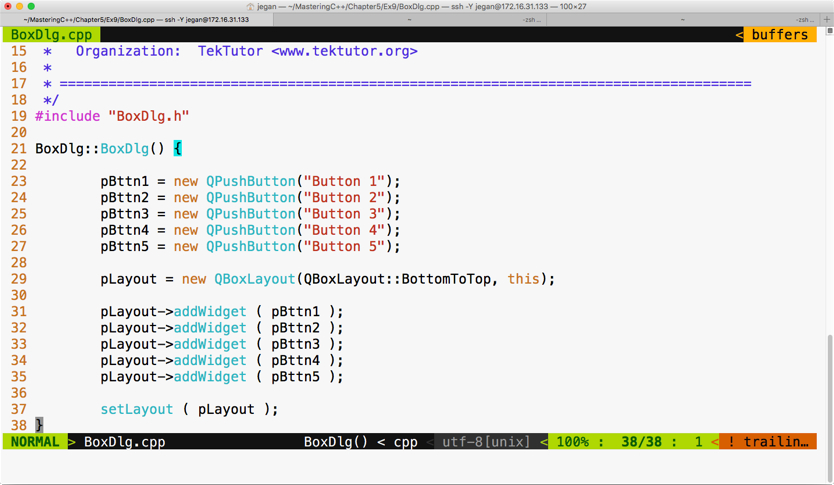

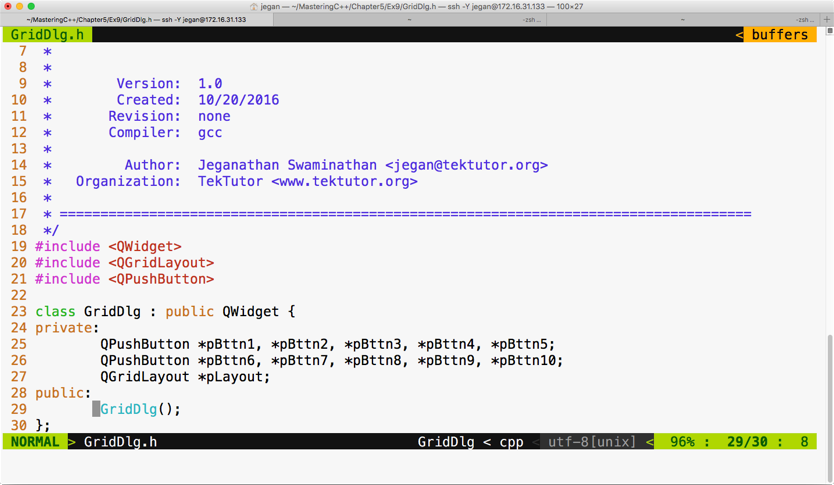

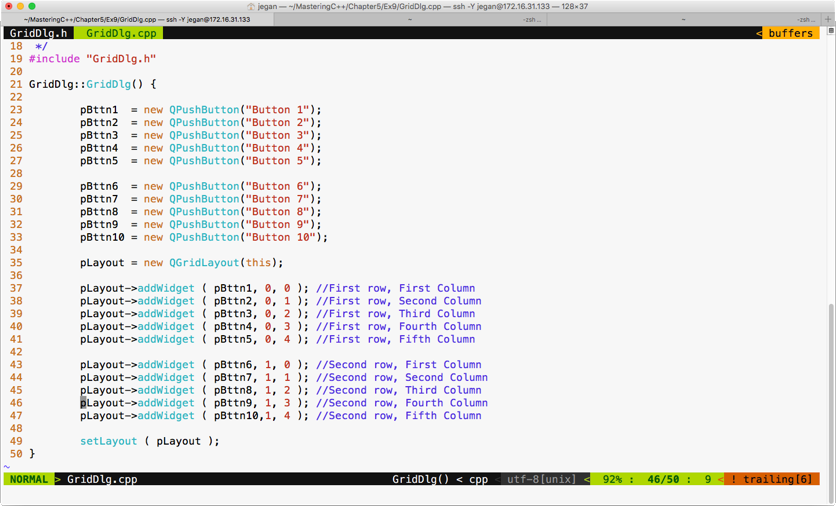

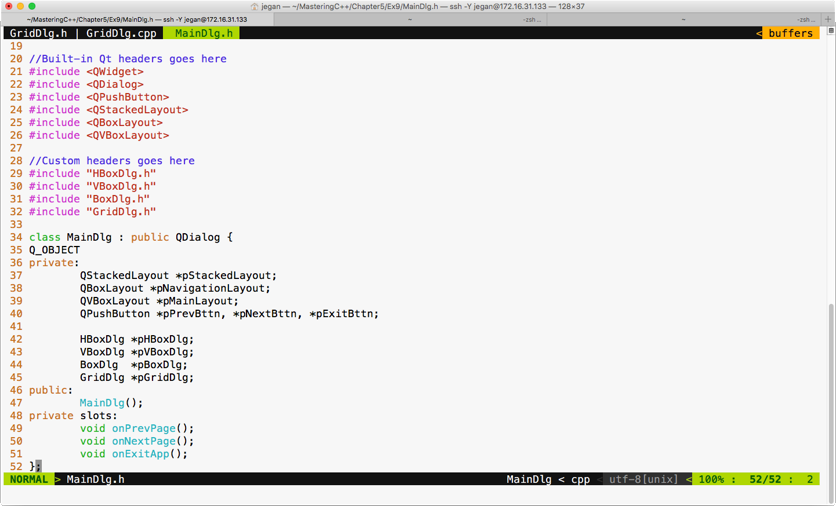

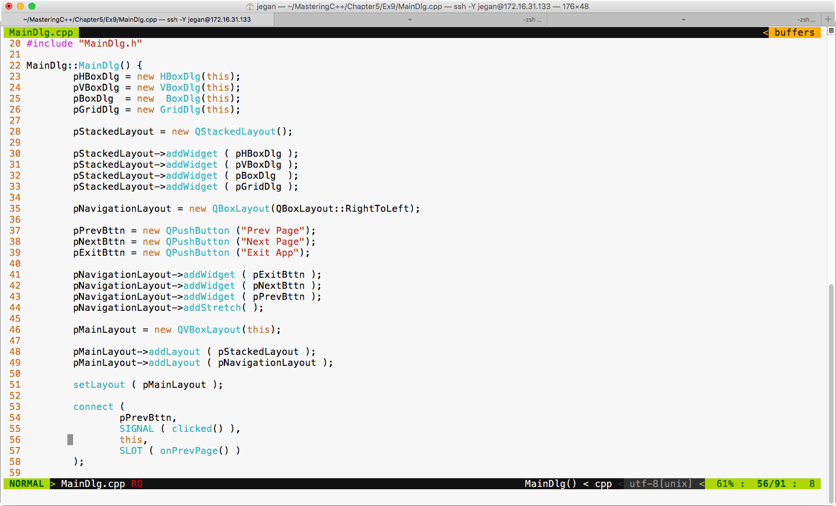

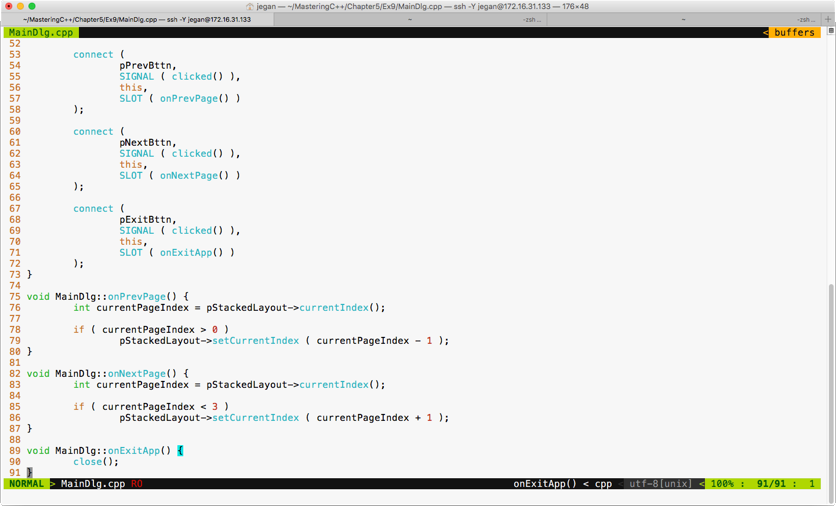

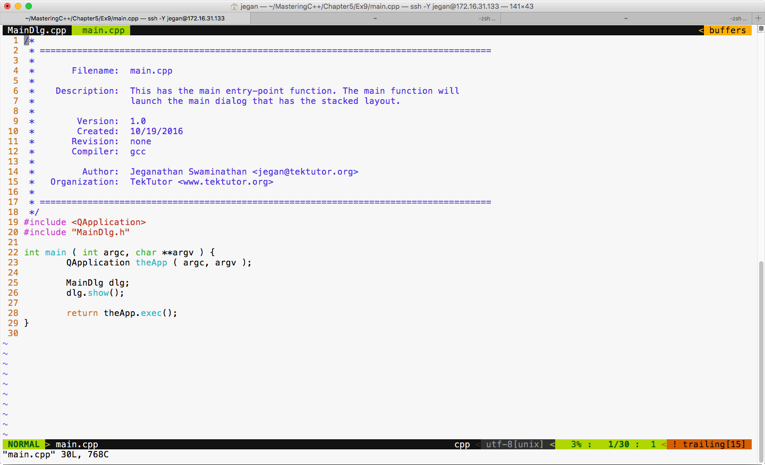

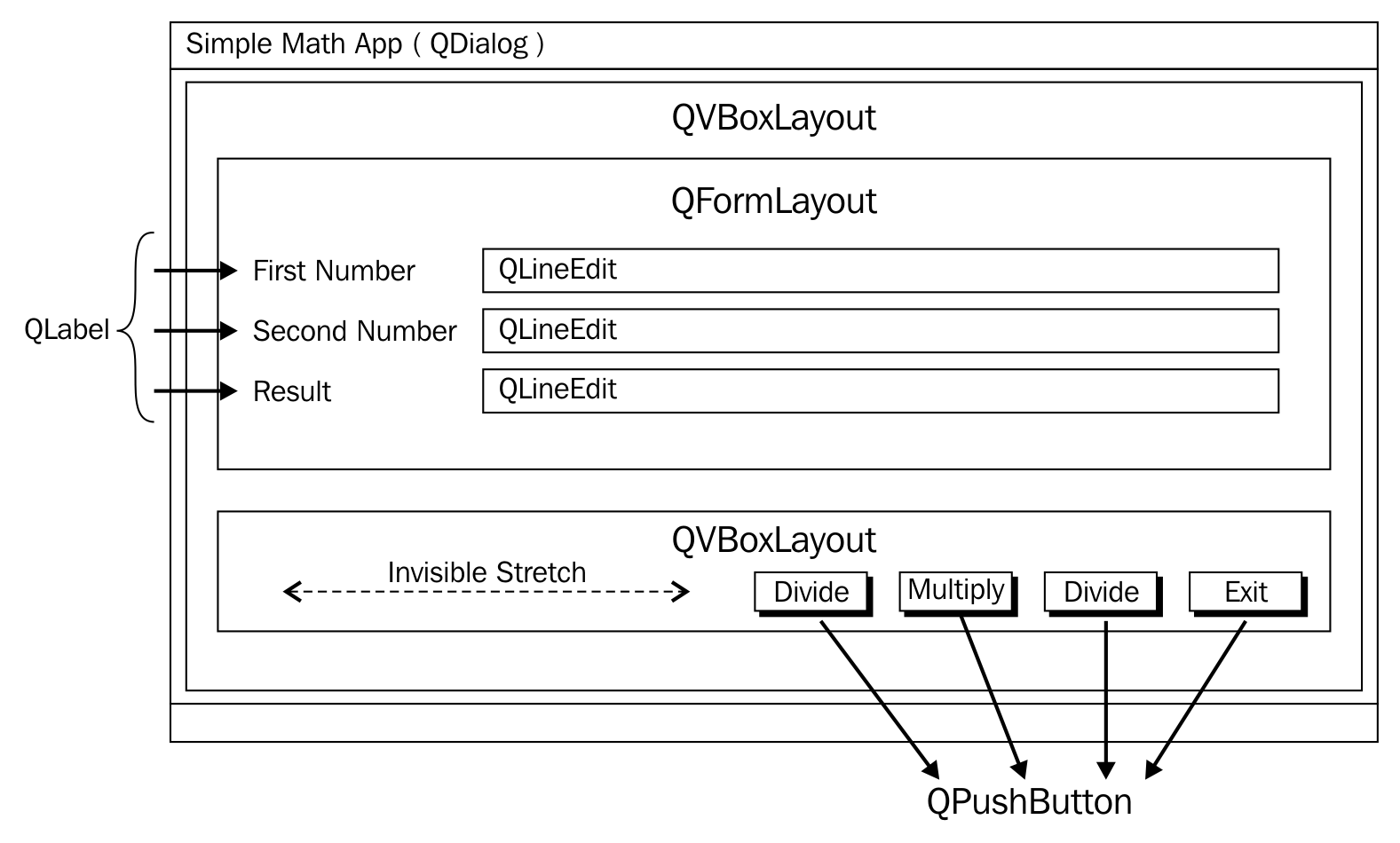

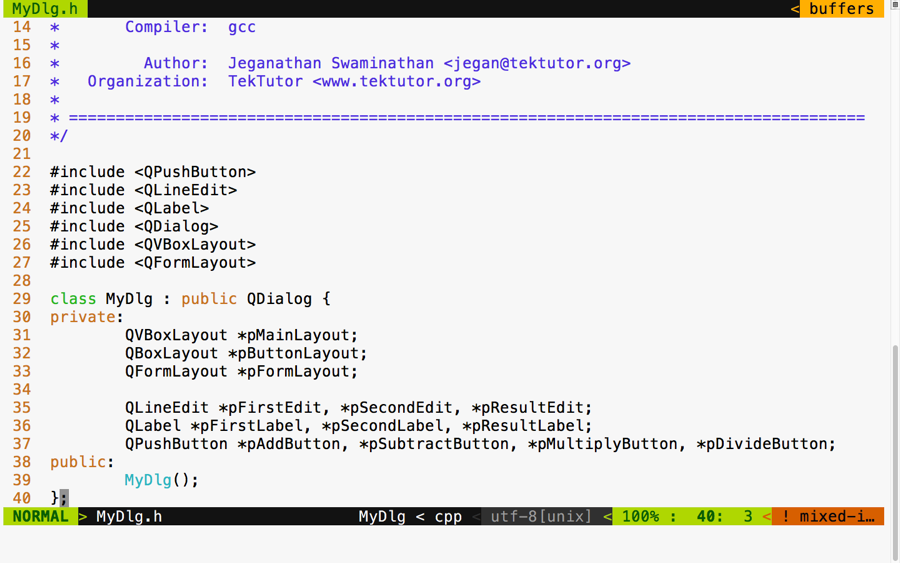

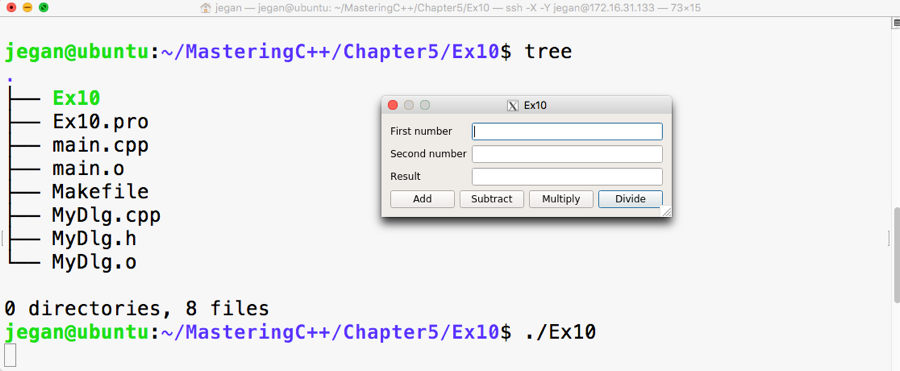

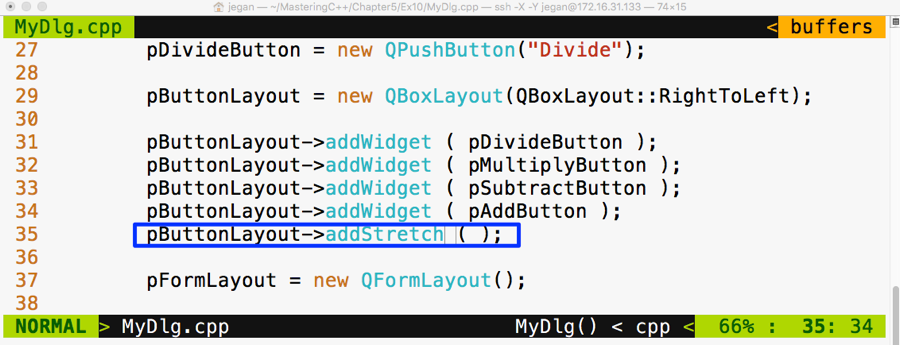

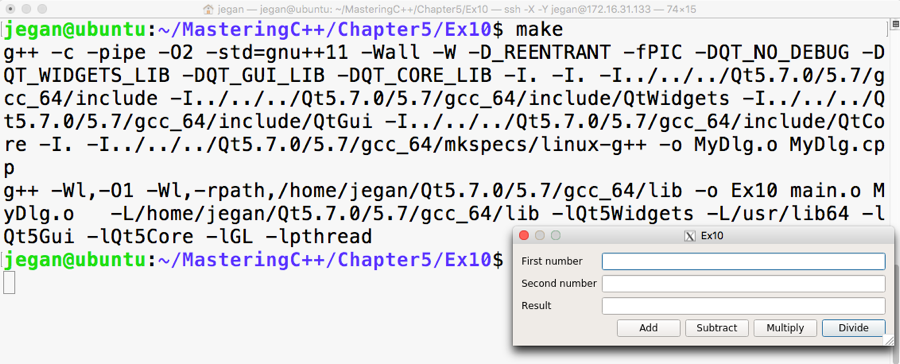

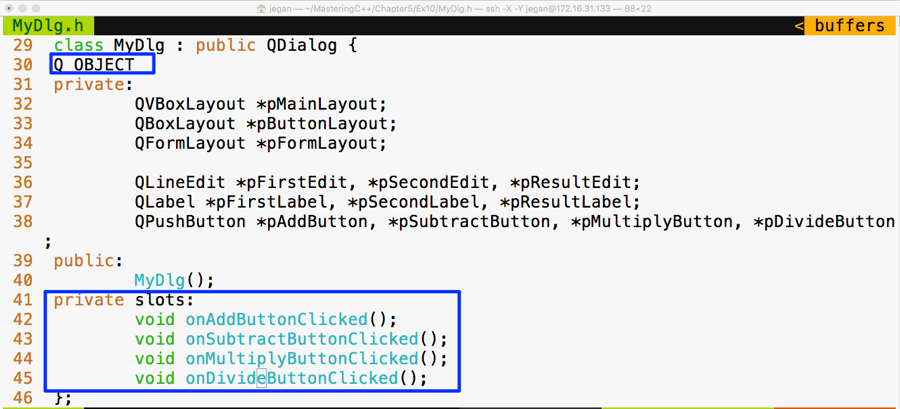

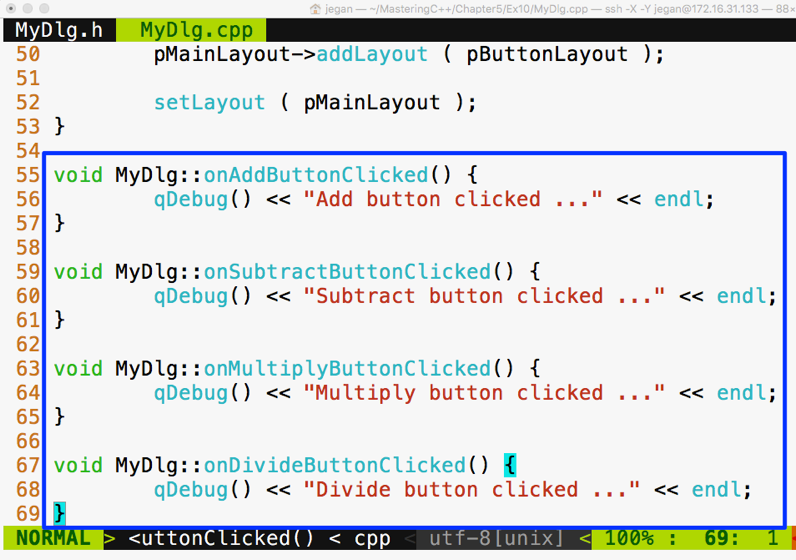

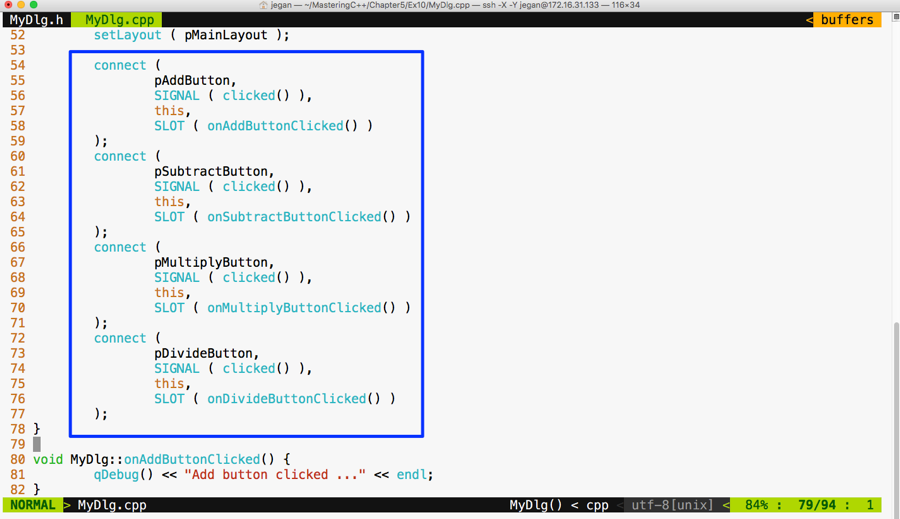

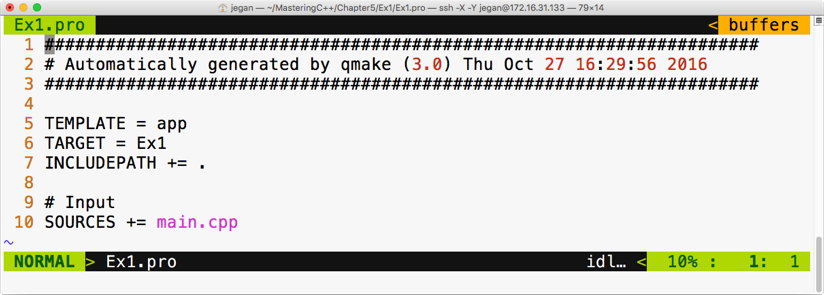

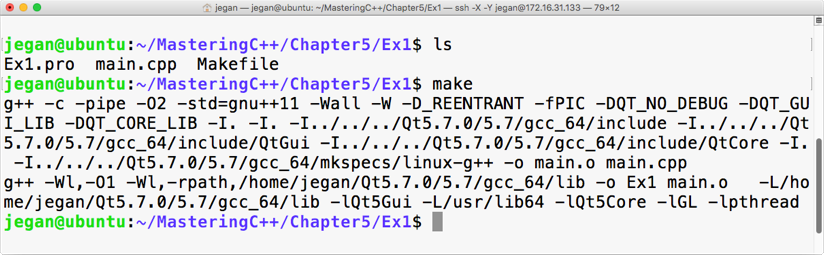

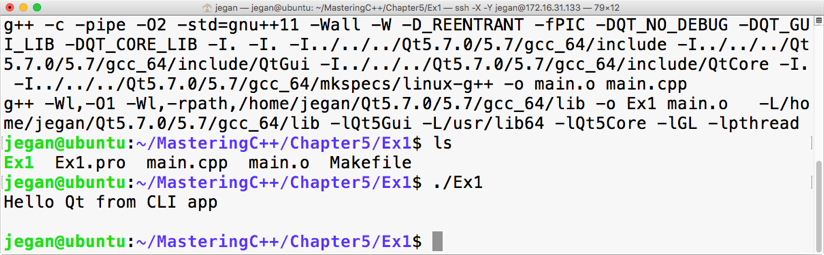

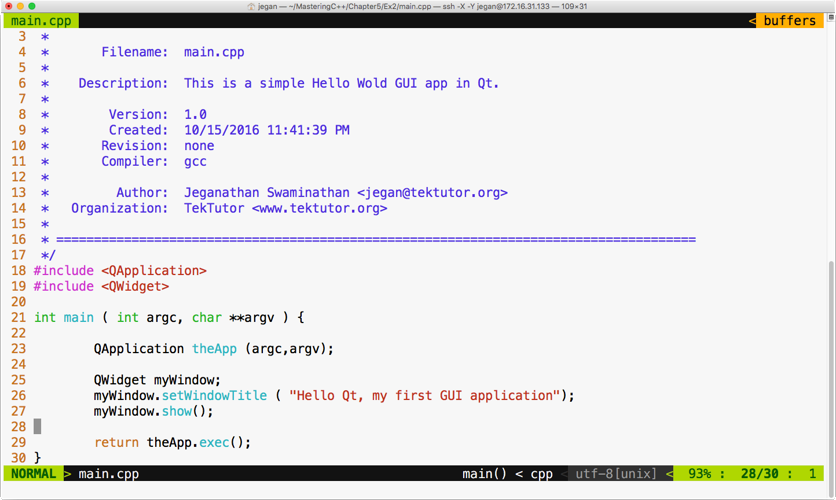

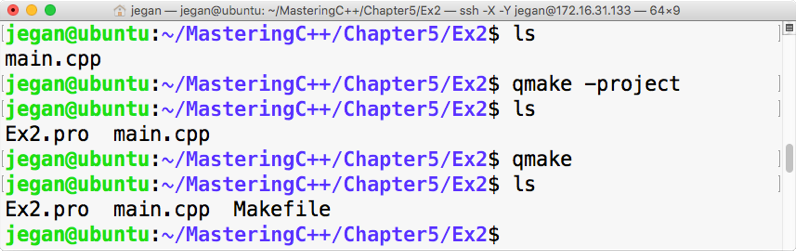

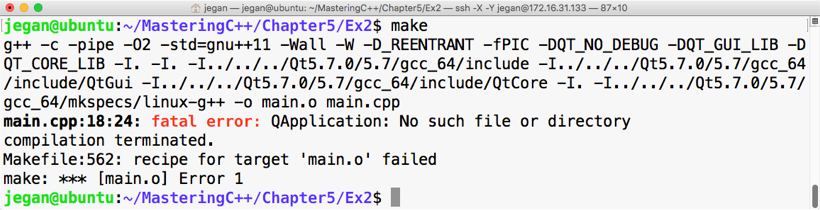

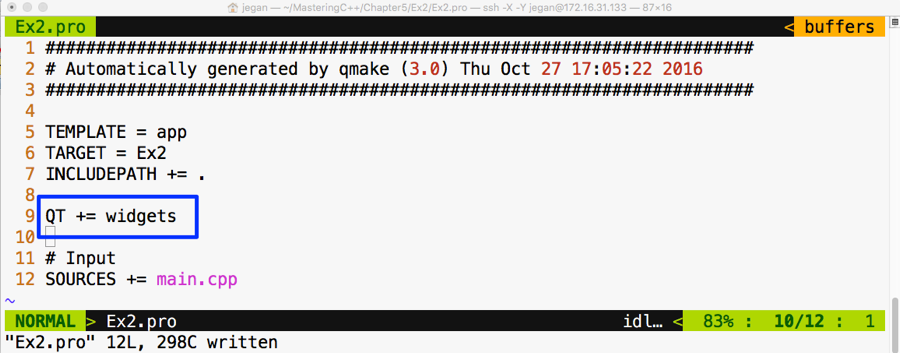

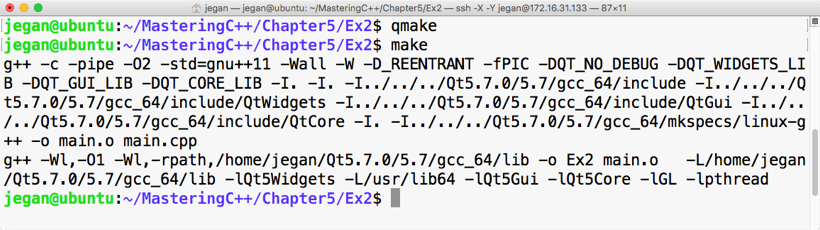

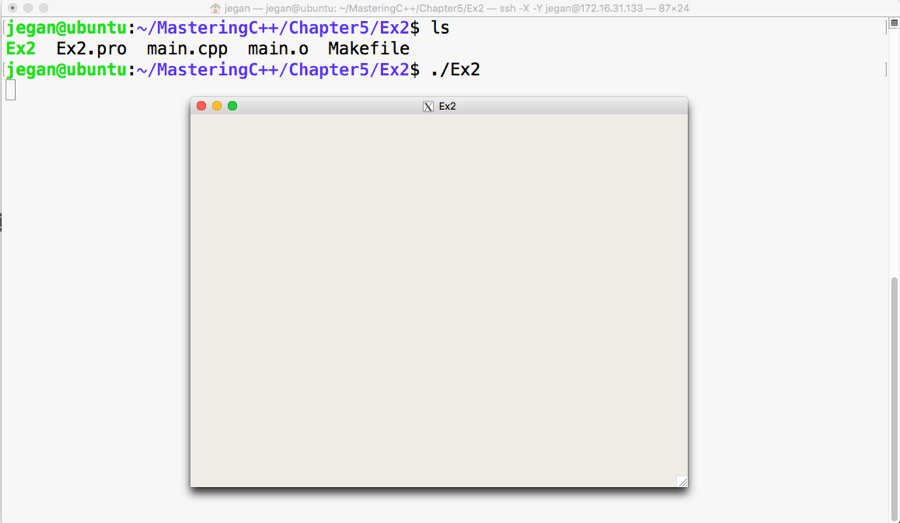

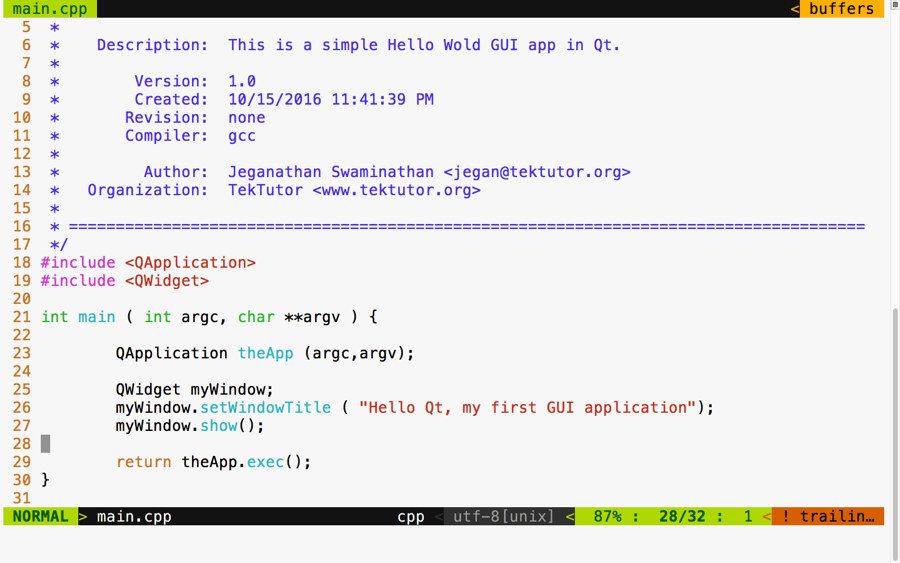

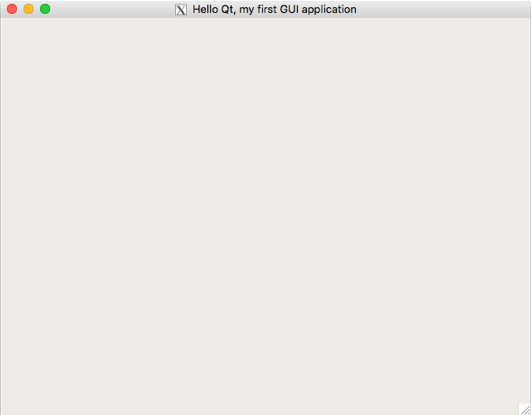

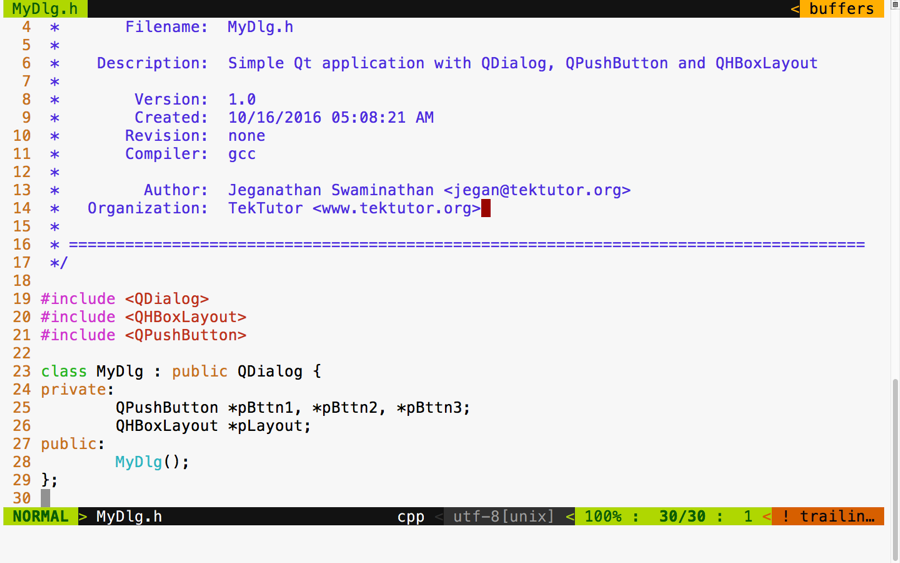

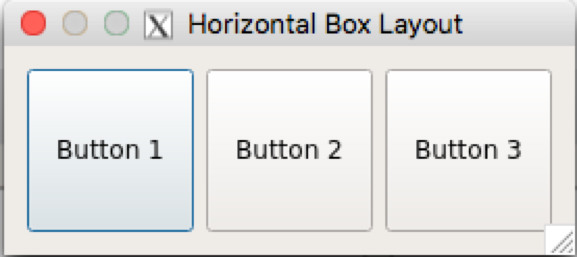

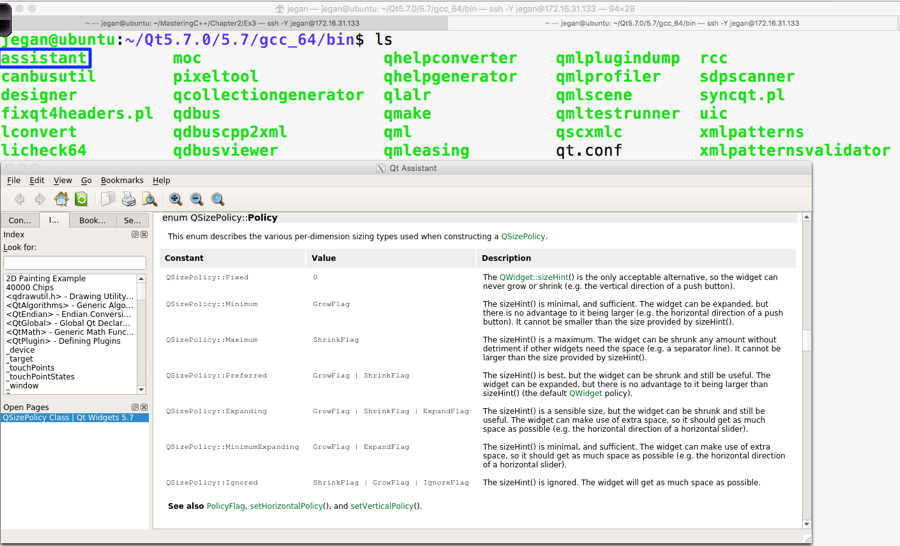

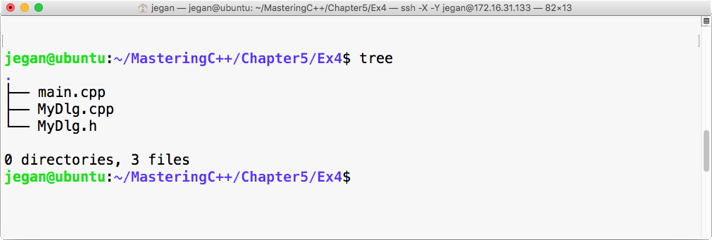

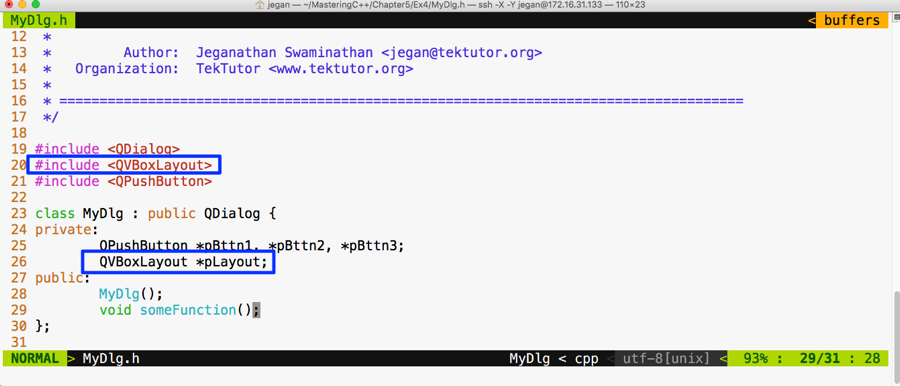

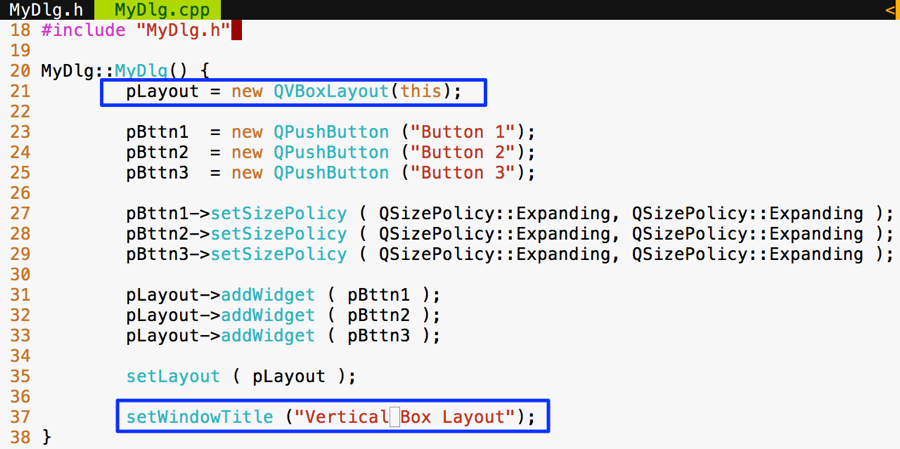

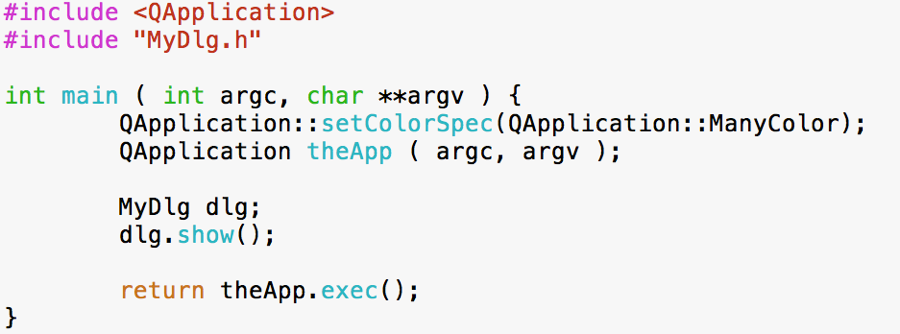

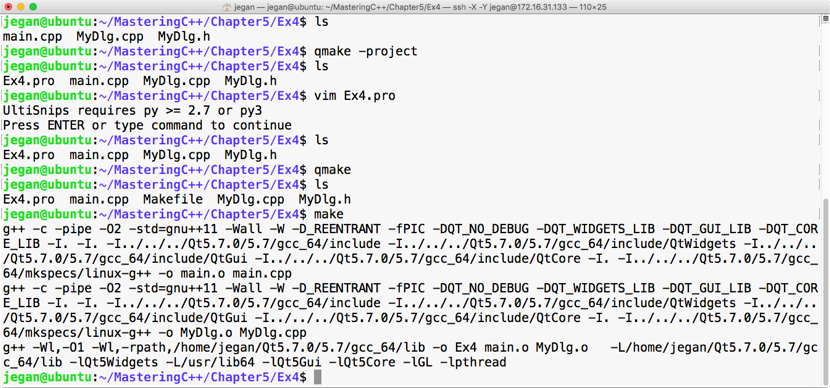

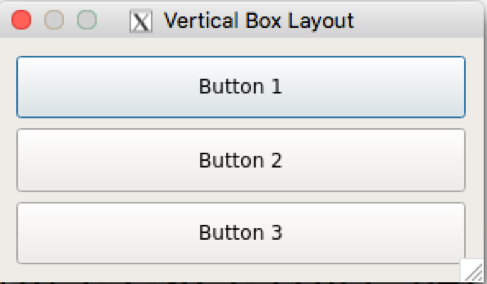

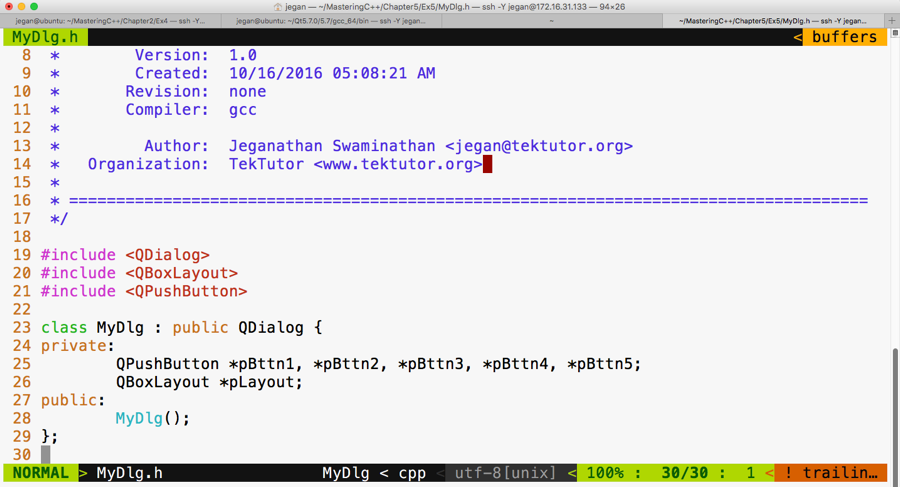

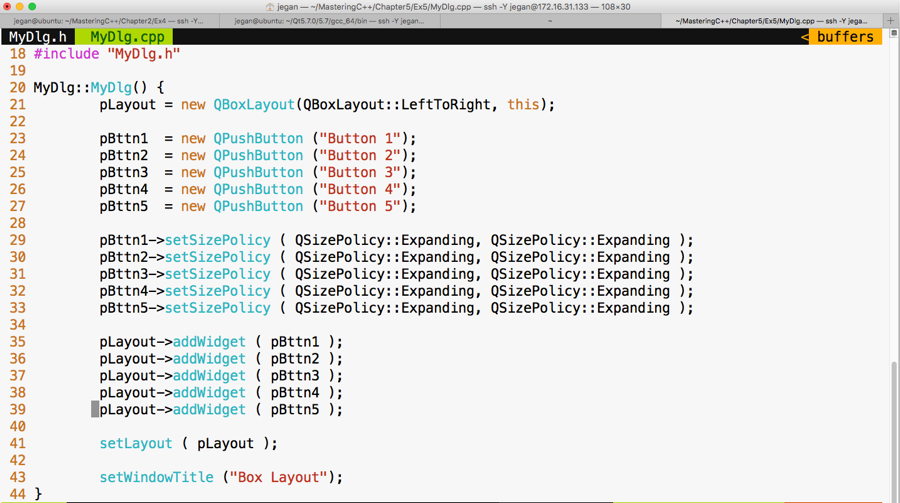

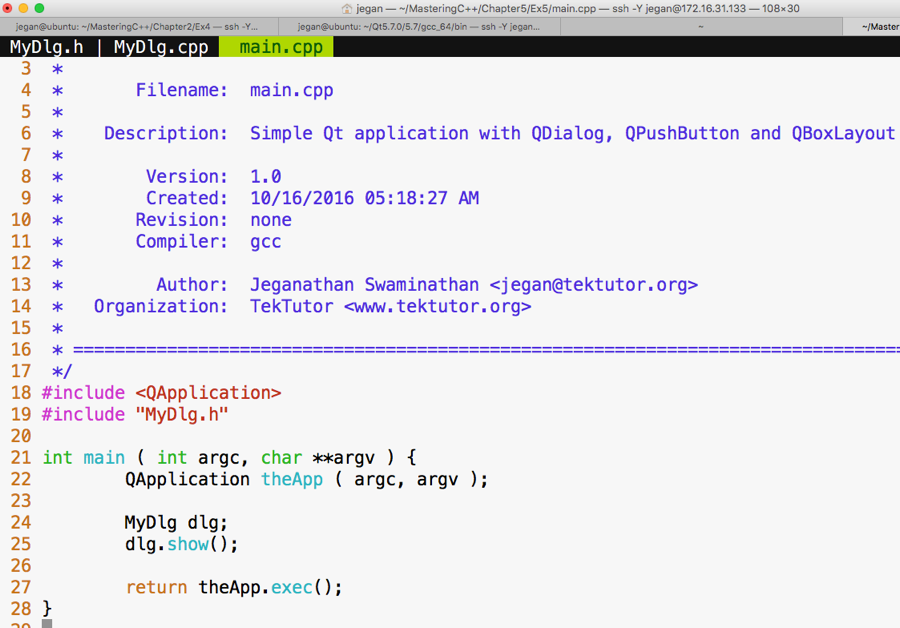

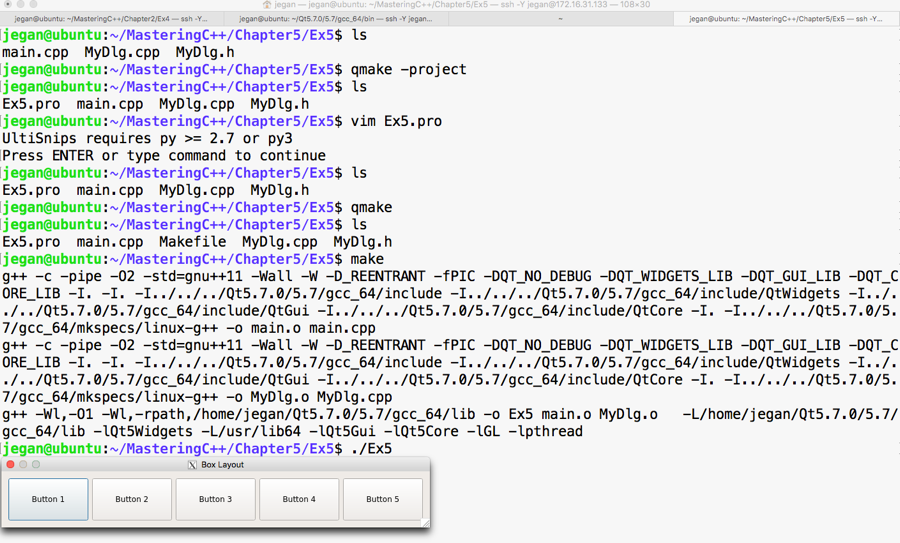

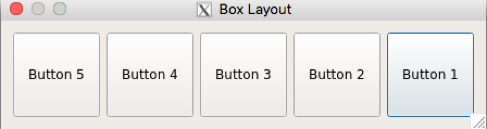

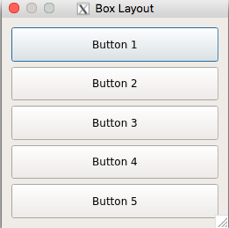

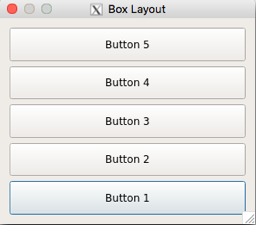

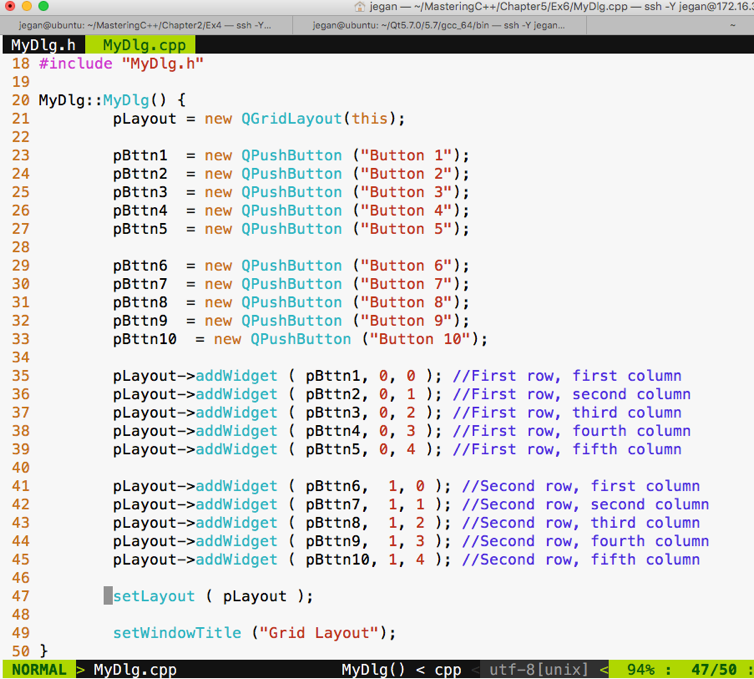

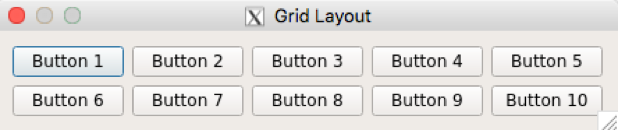

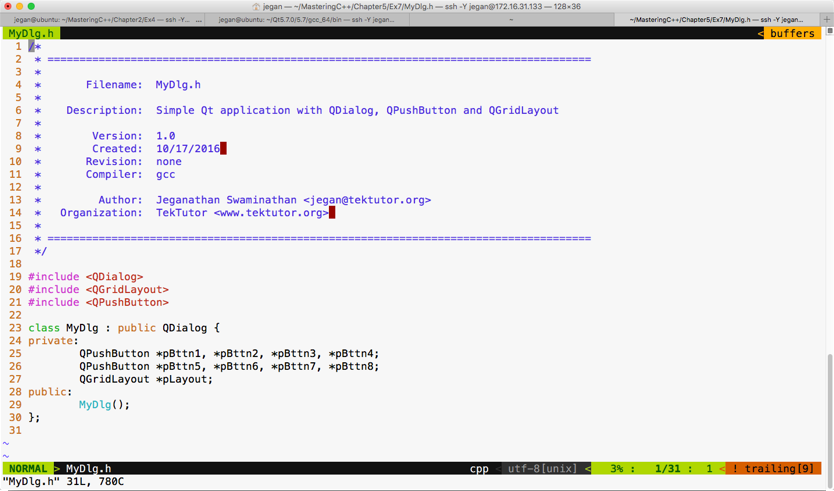

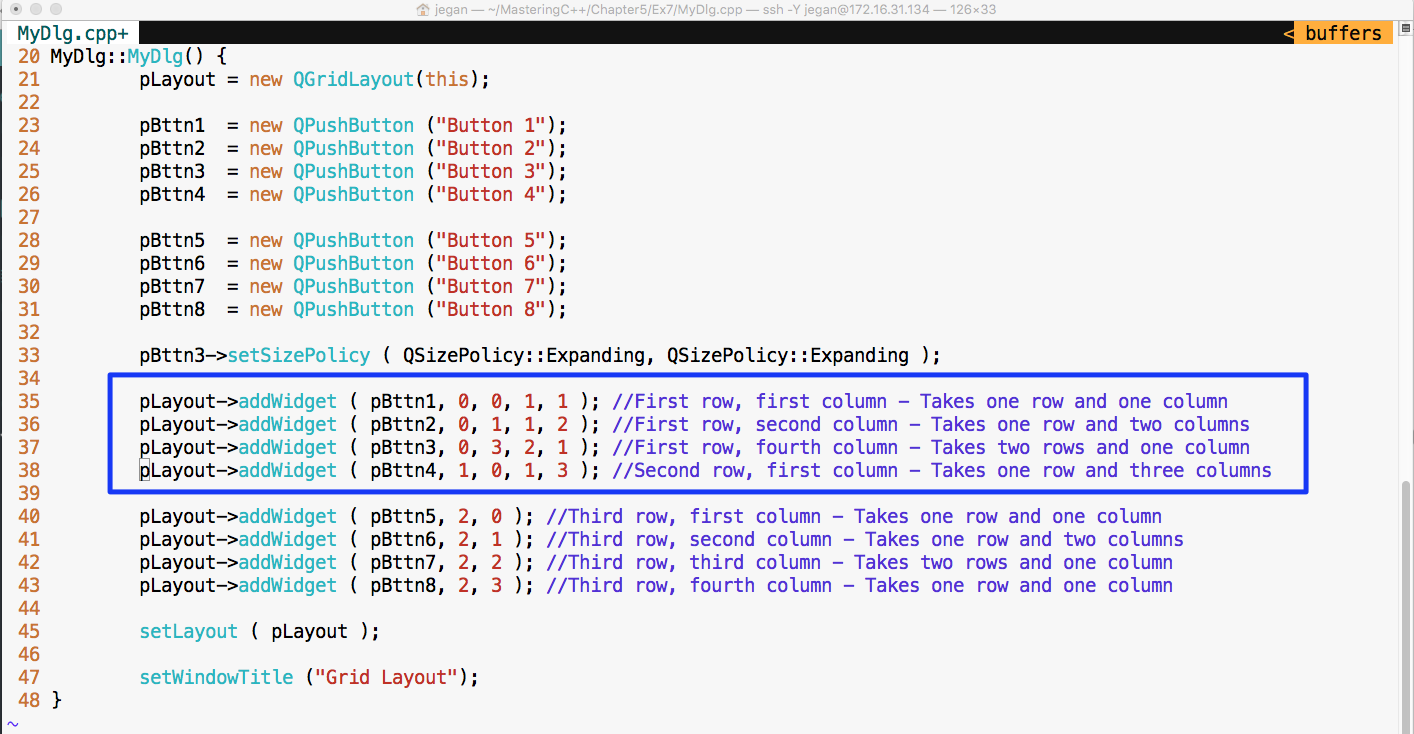

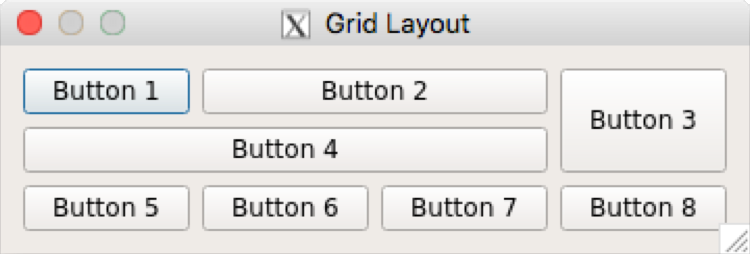

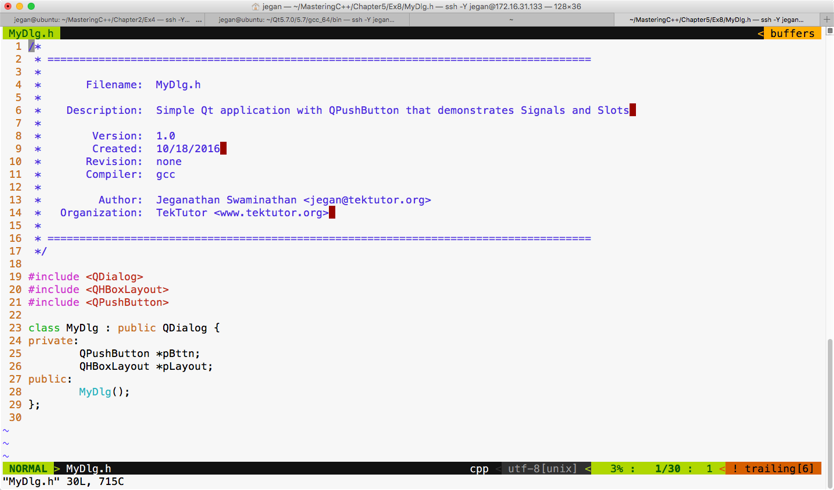

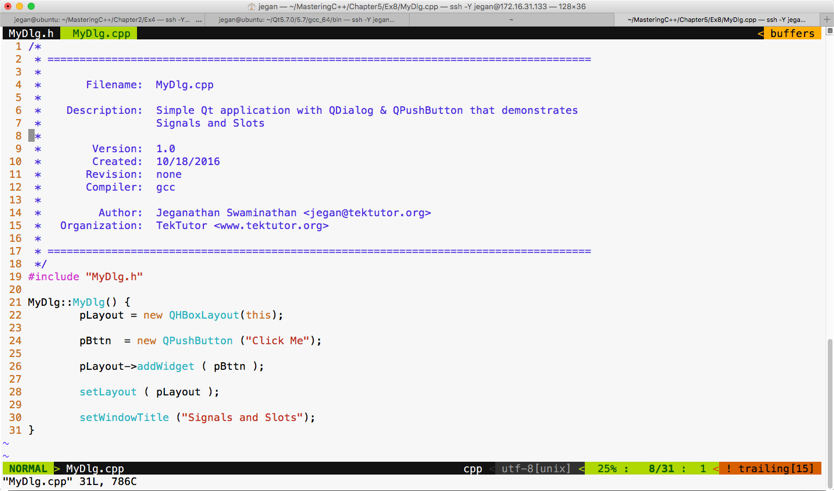

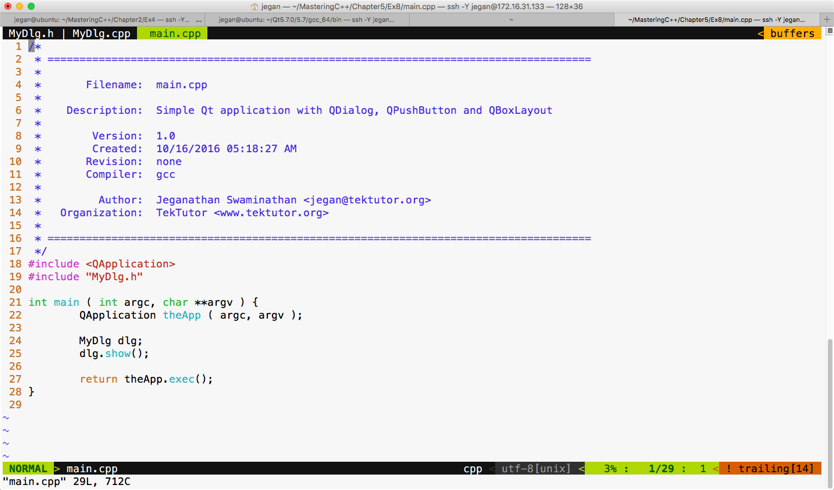

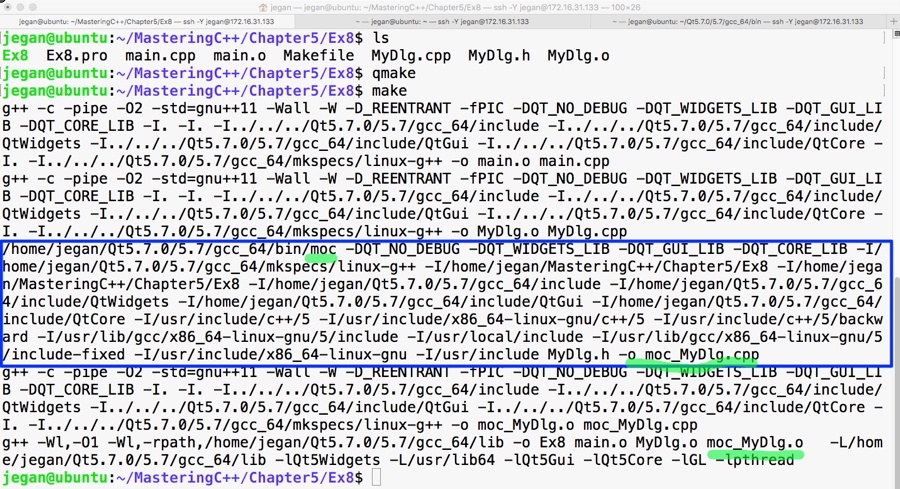

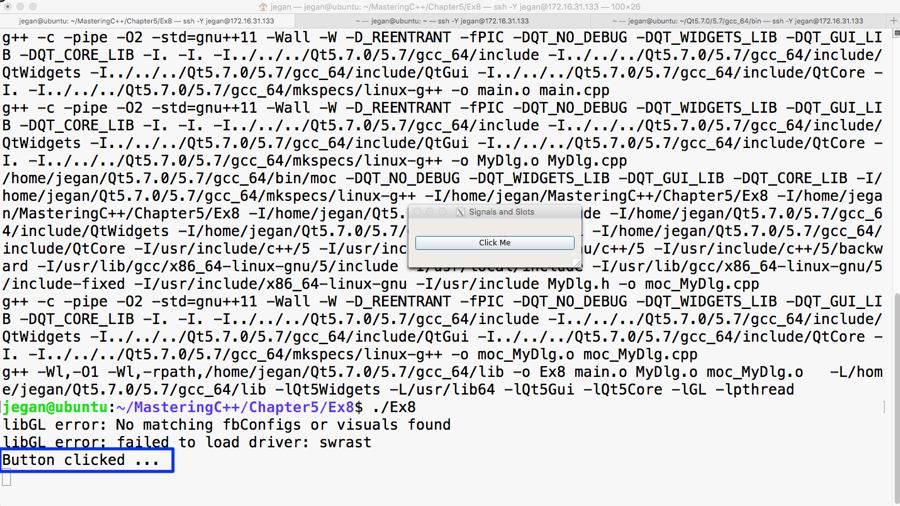

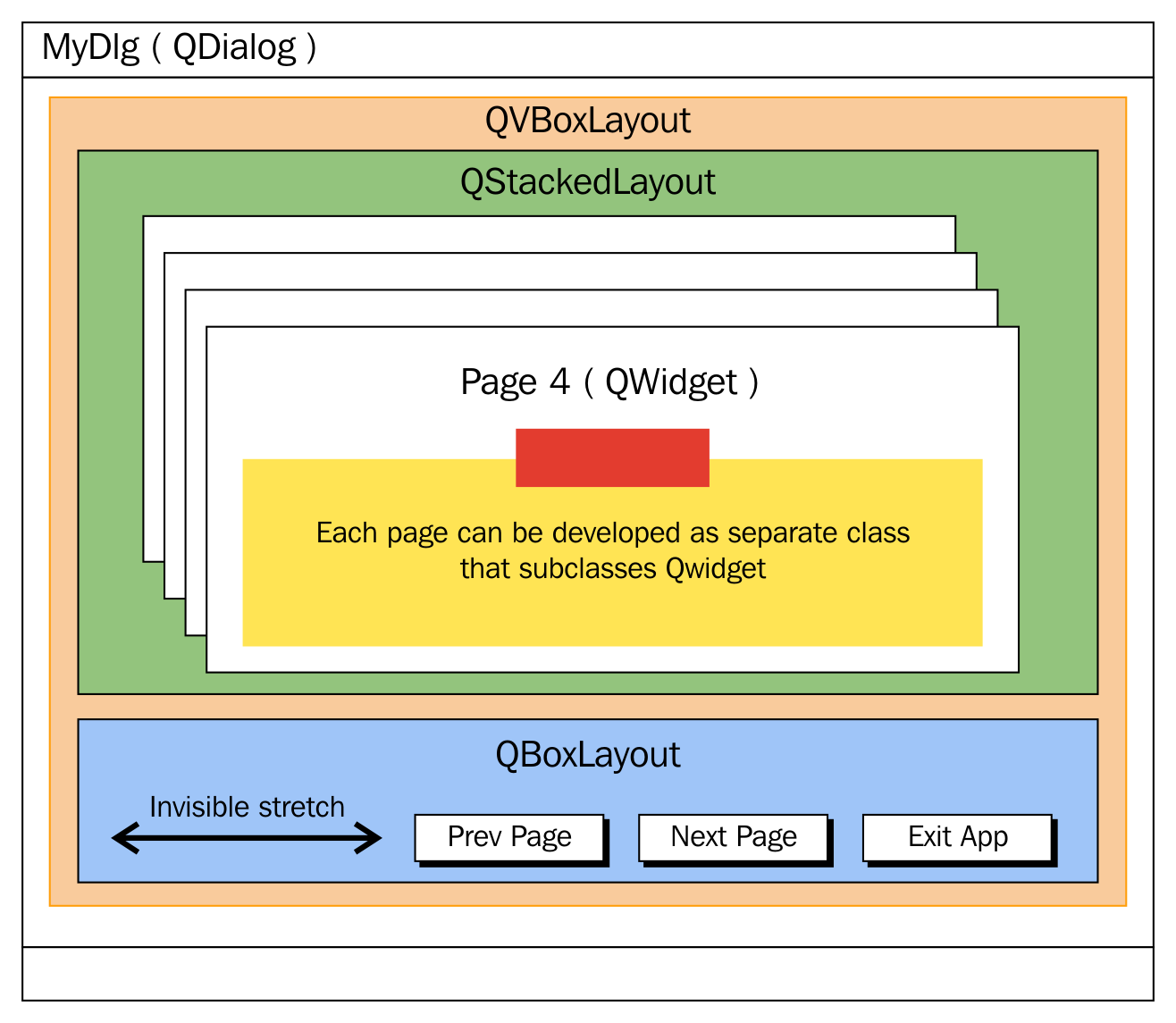

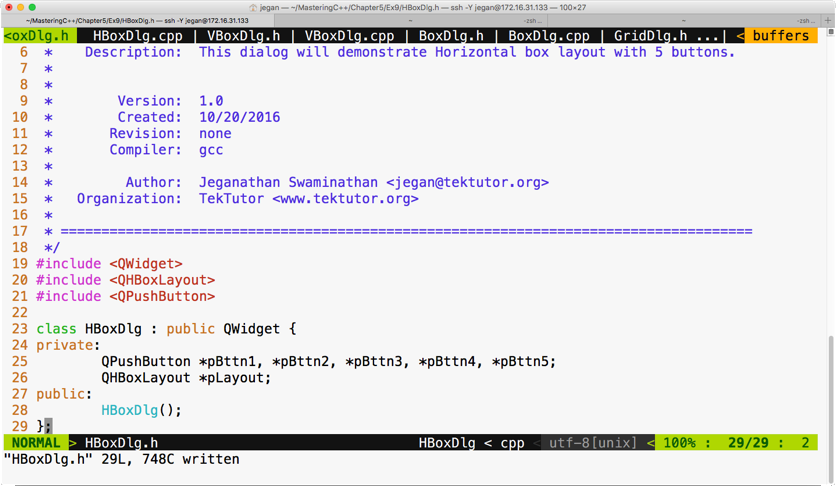

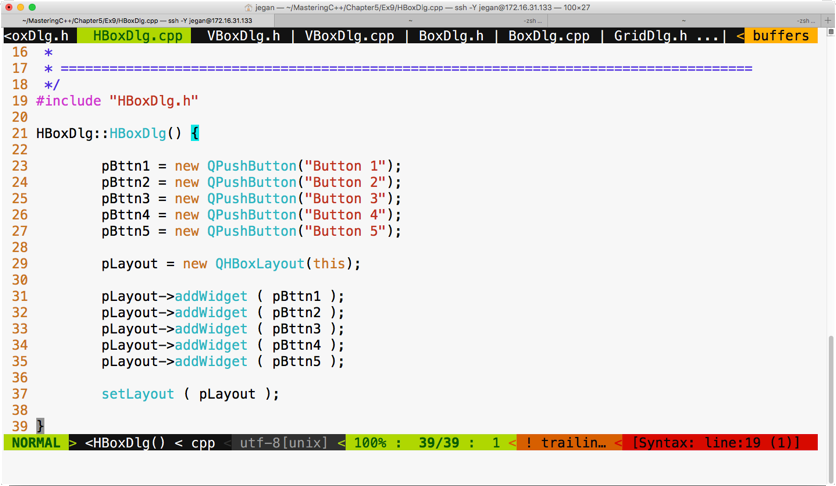

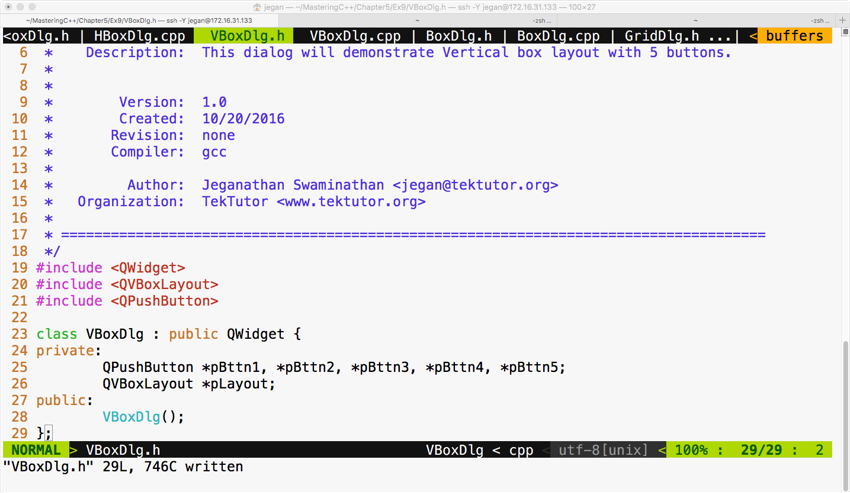

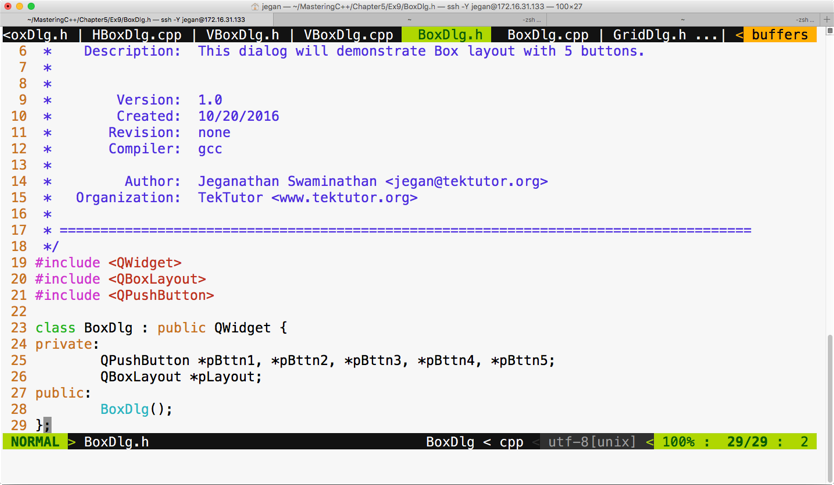

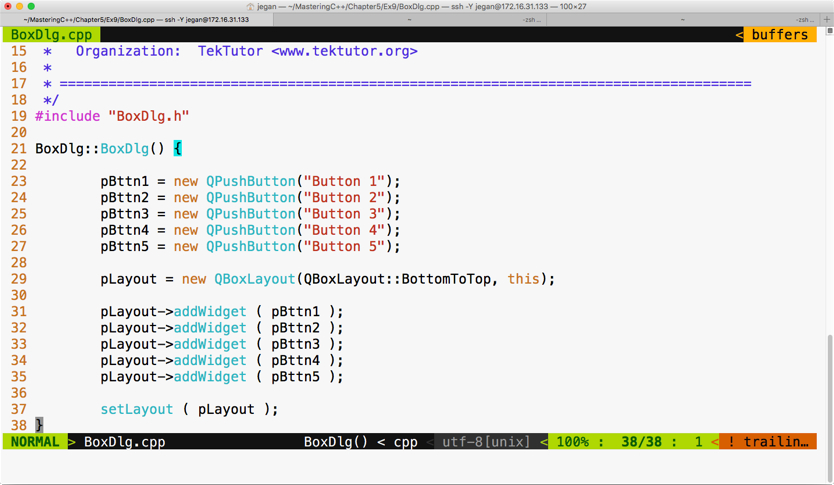

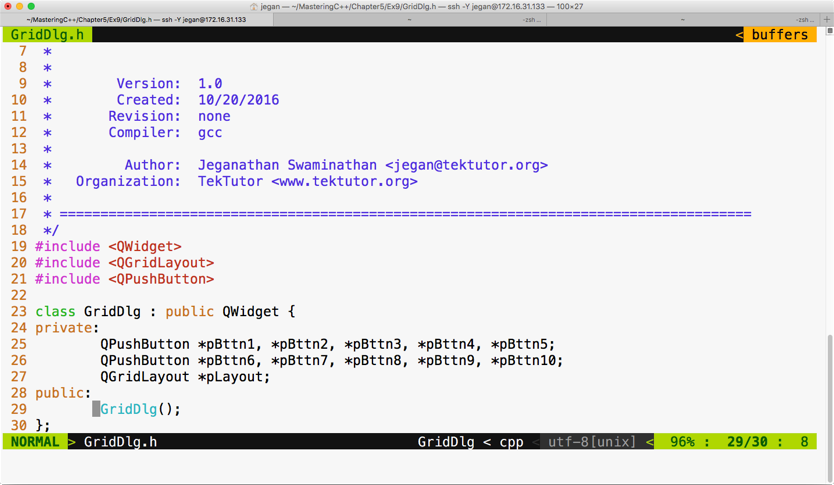

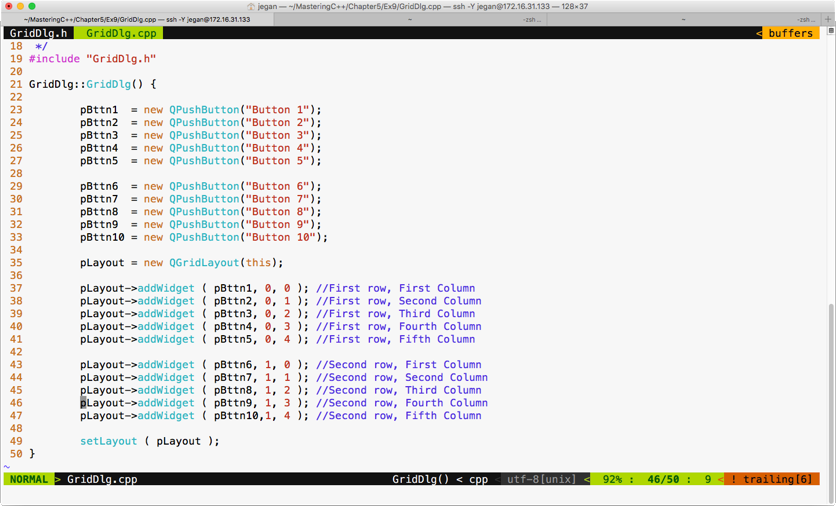

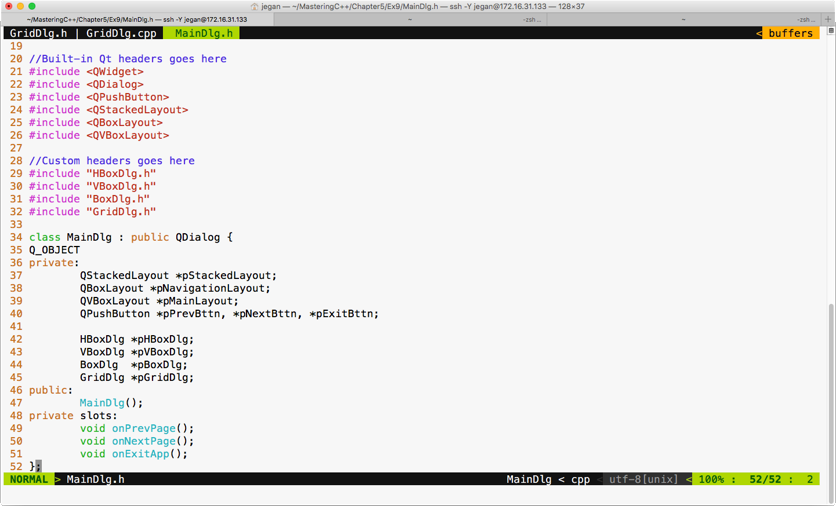

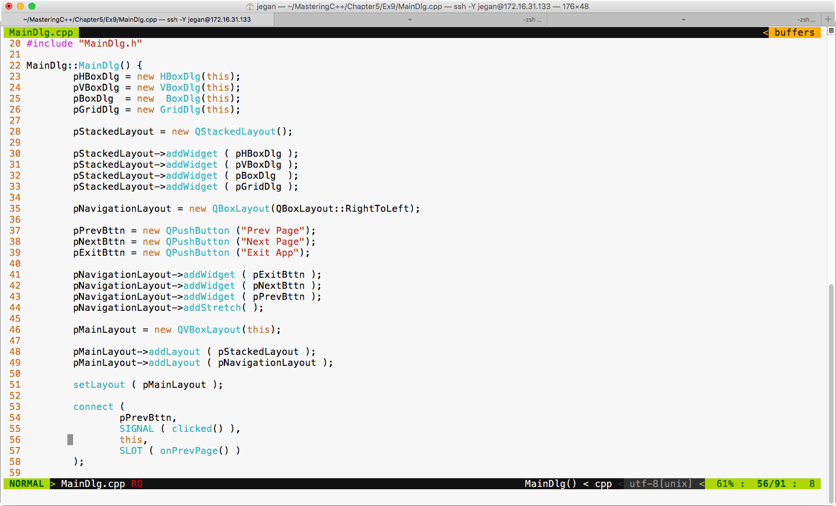

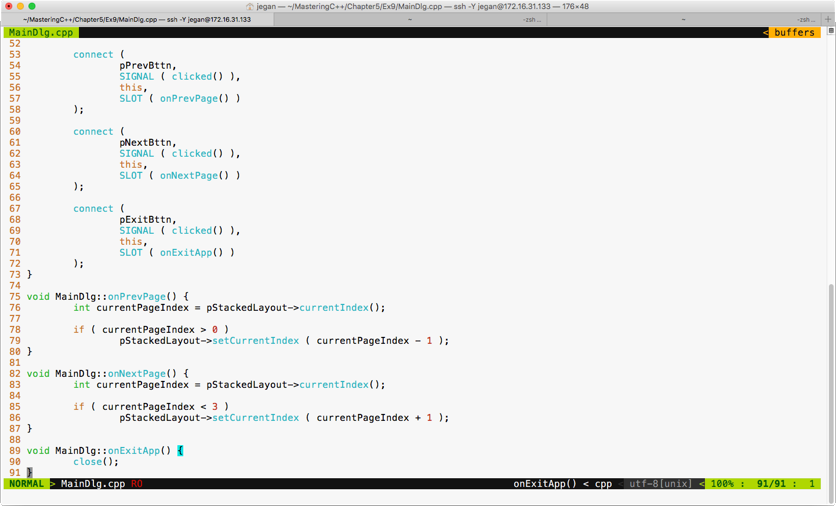

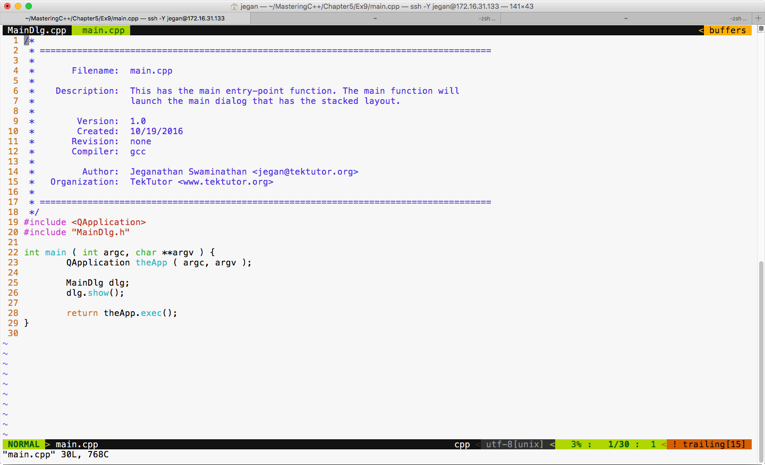

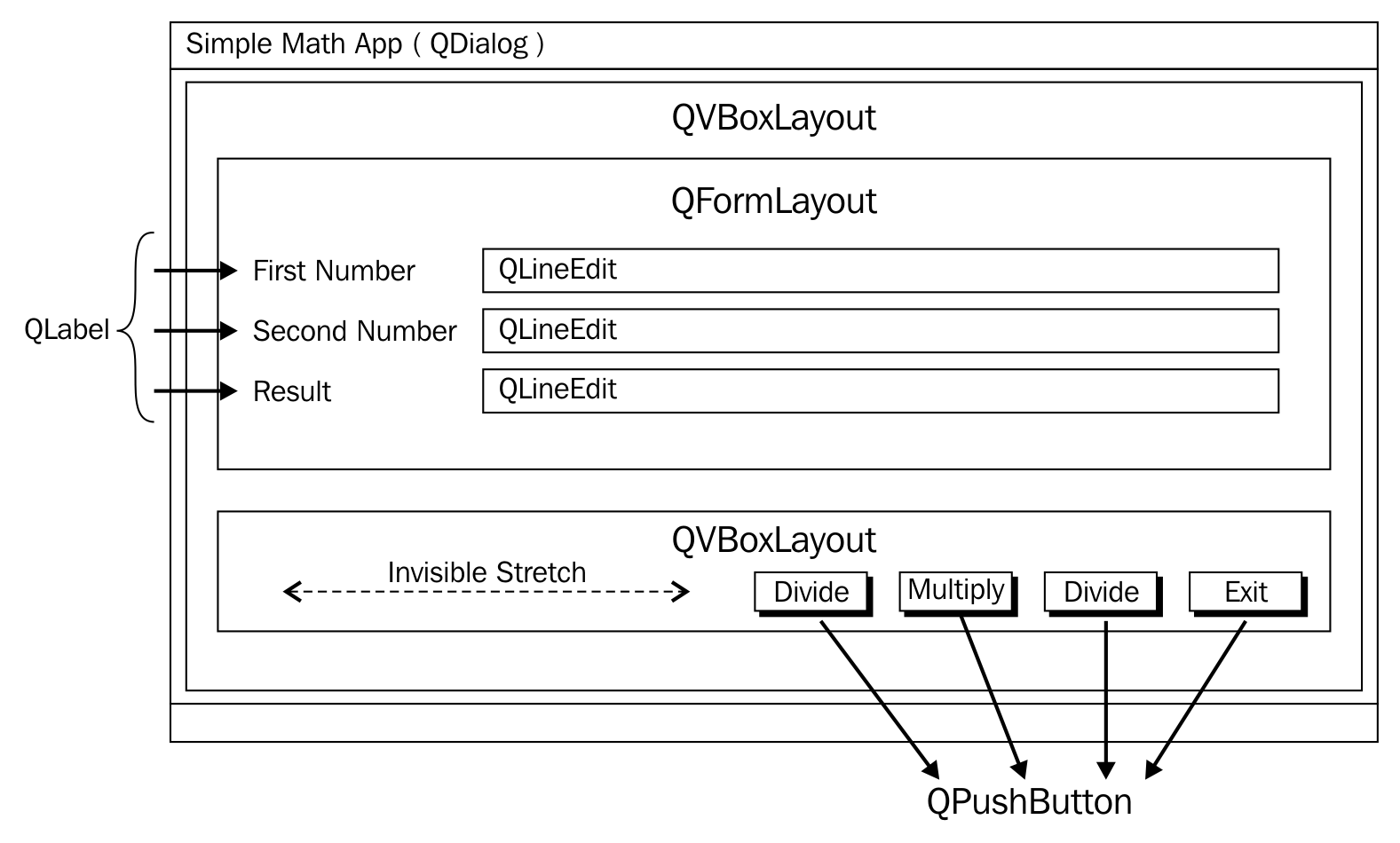

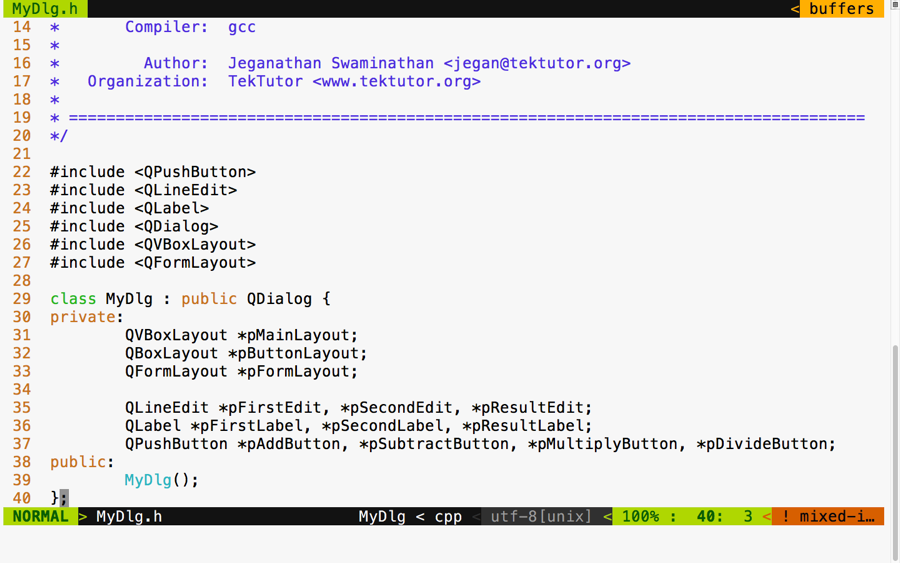

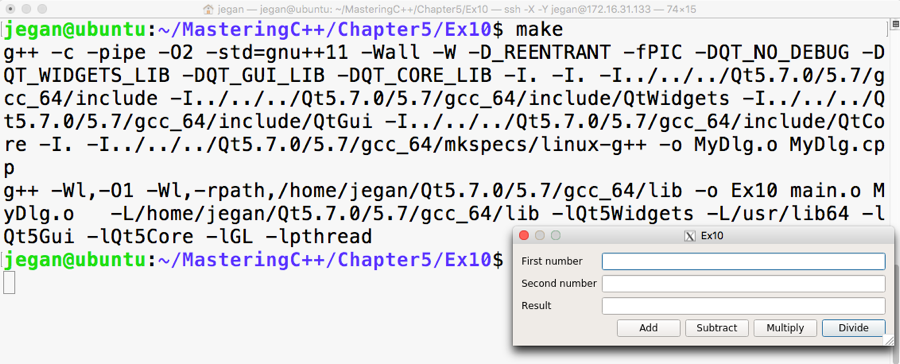

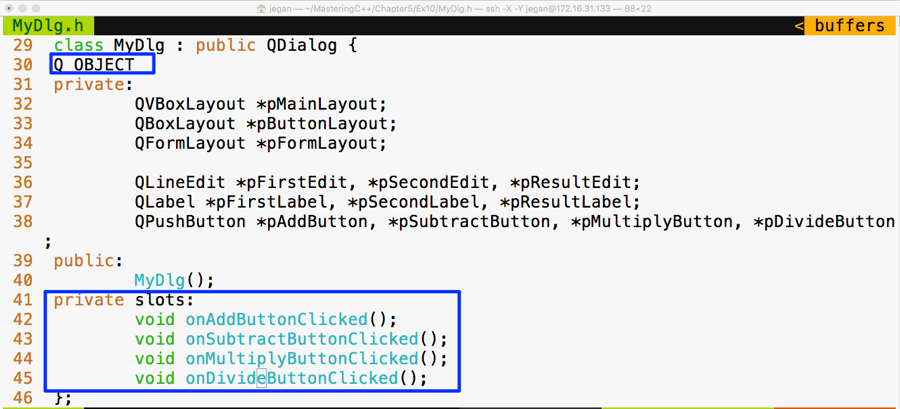

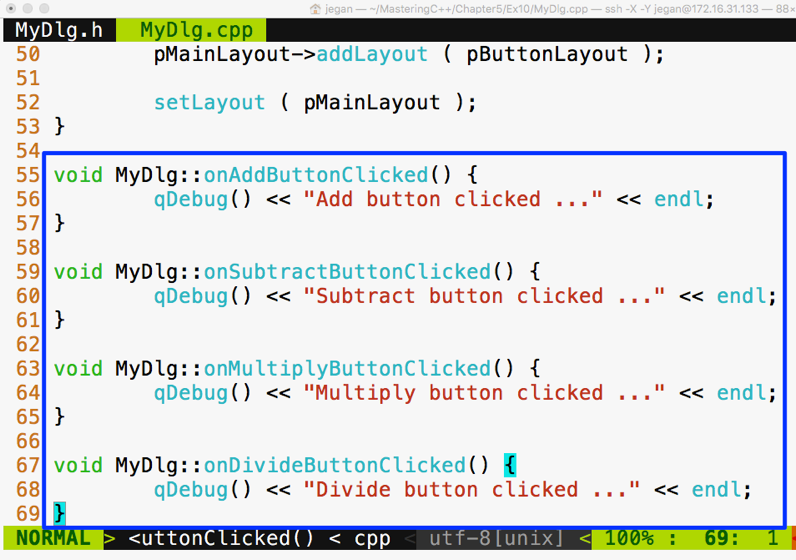

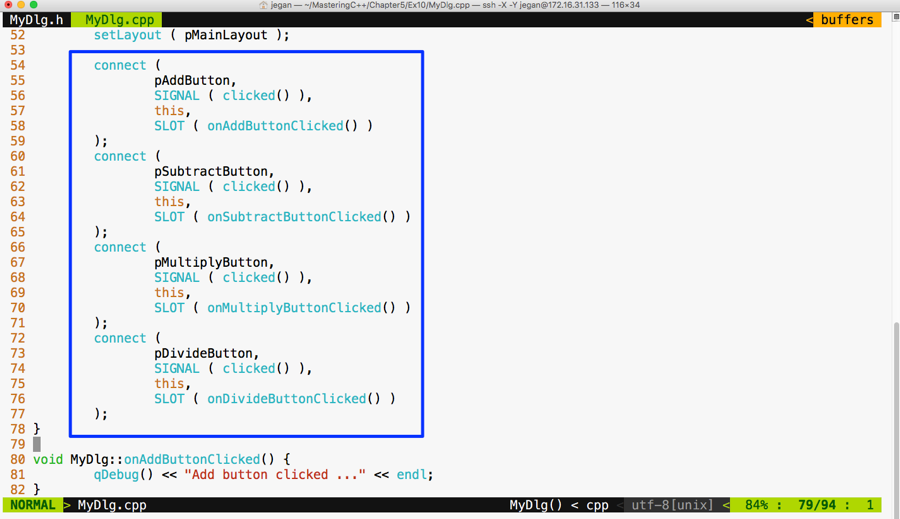

Chapter 5, Developing GUI Applications in C++, gives an overview of Qt and provides you with step-by-step instructions to install Qt on Linux and Windows. The chapter gradually helps you develop impressive GUI applications with interesting widgets and various layouts.

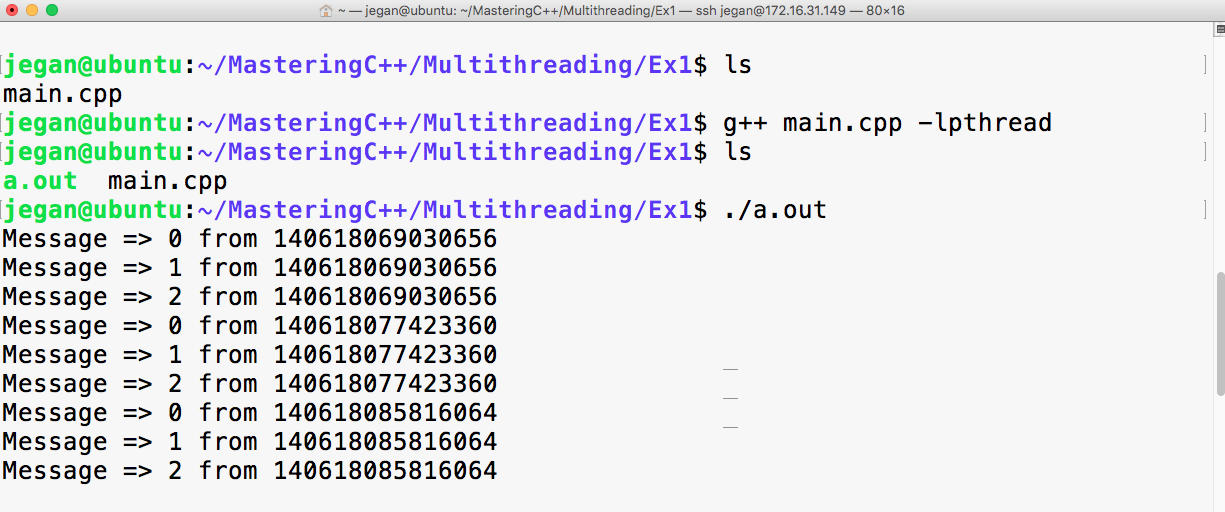

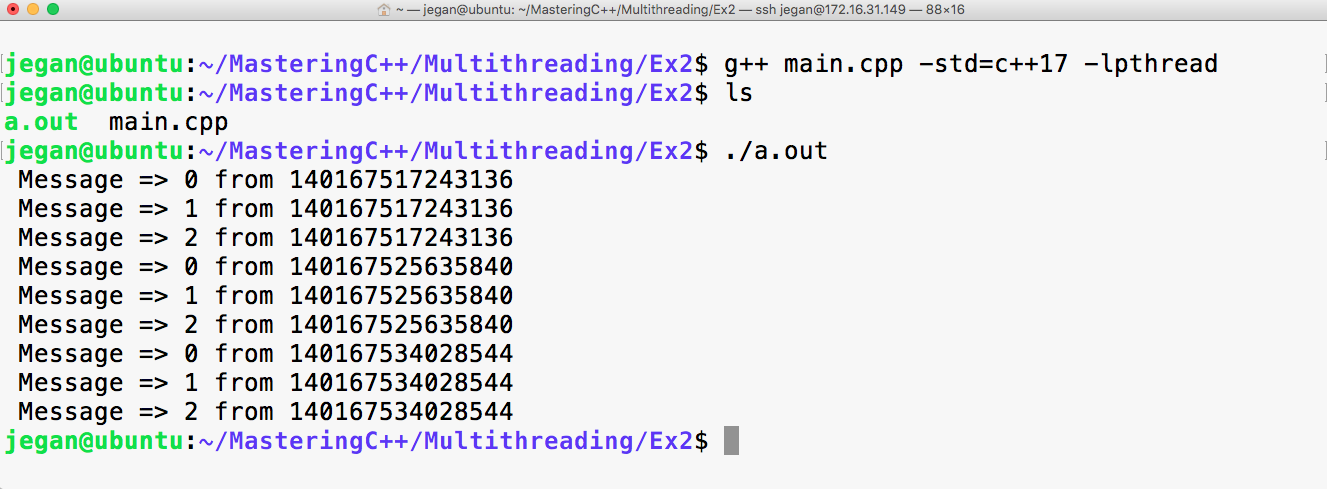

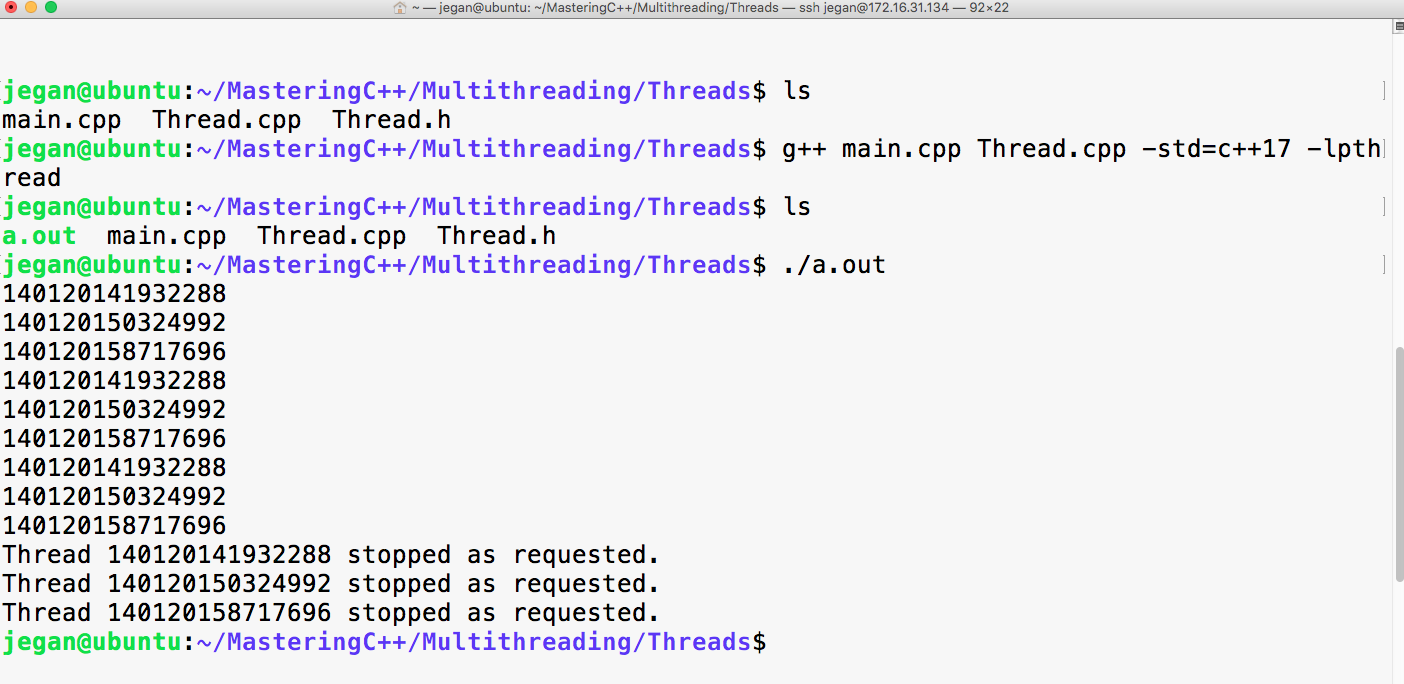

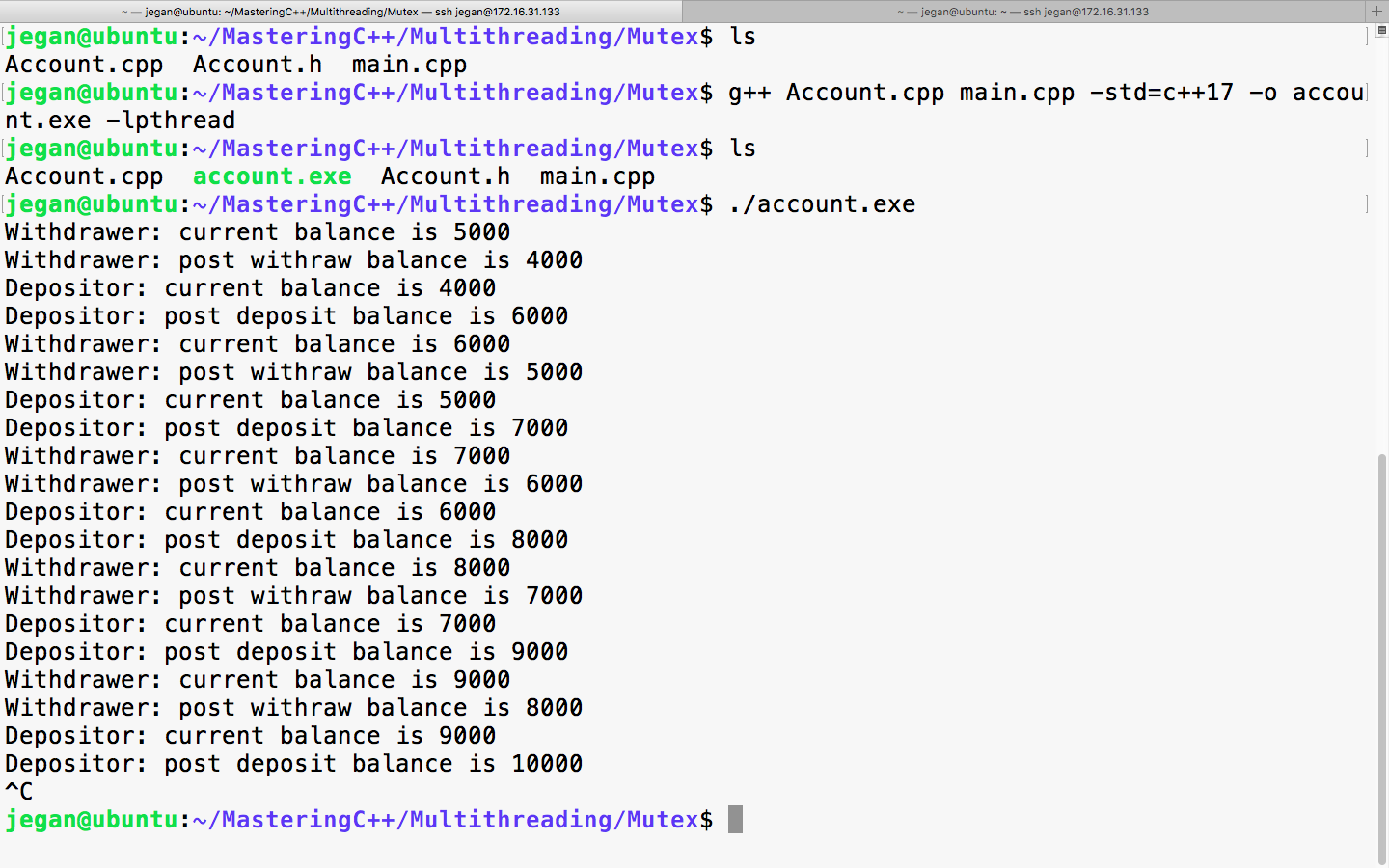

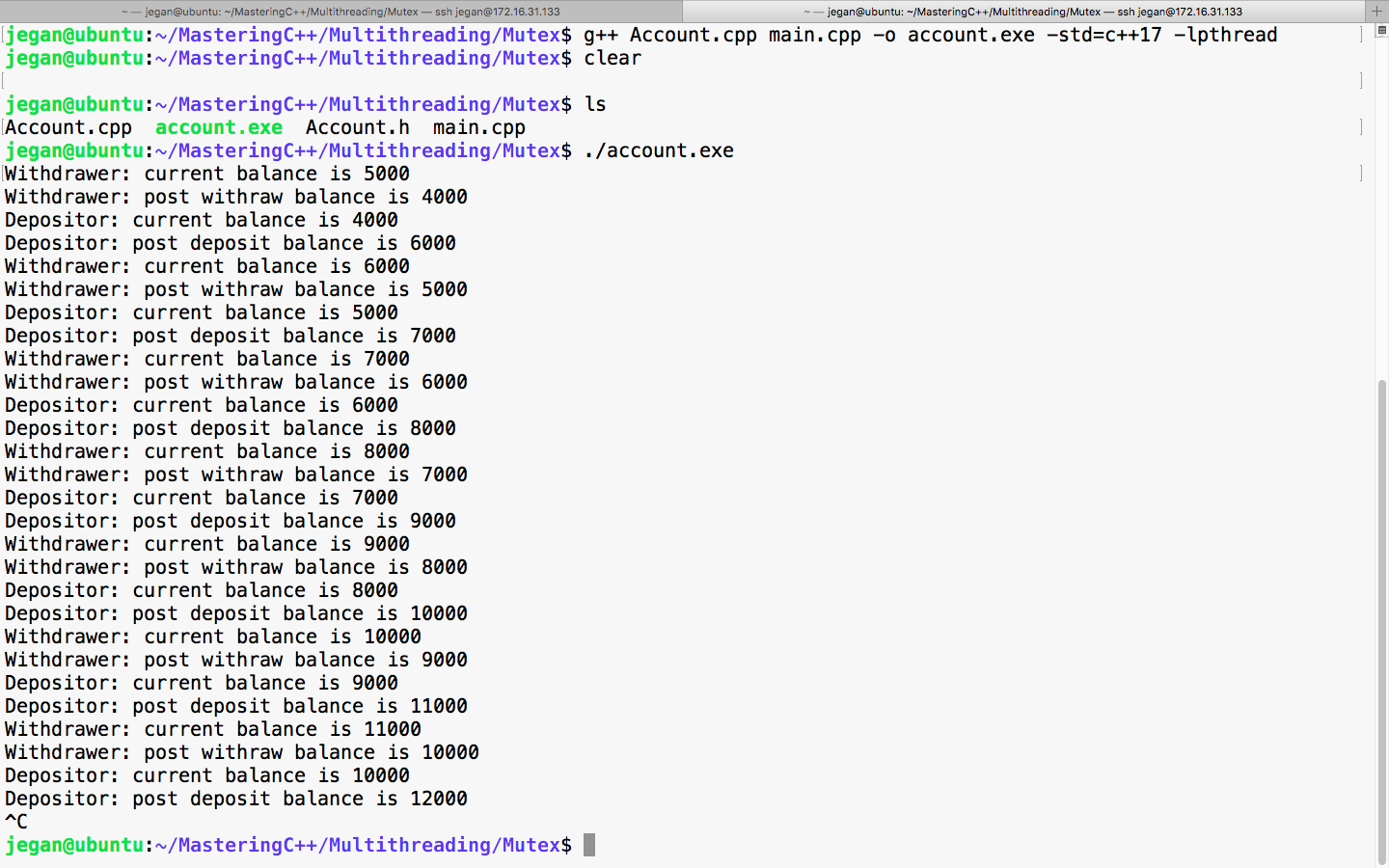

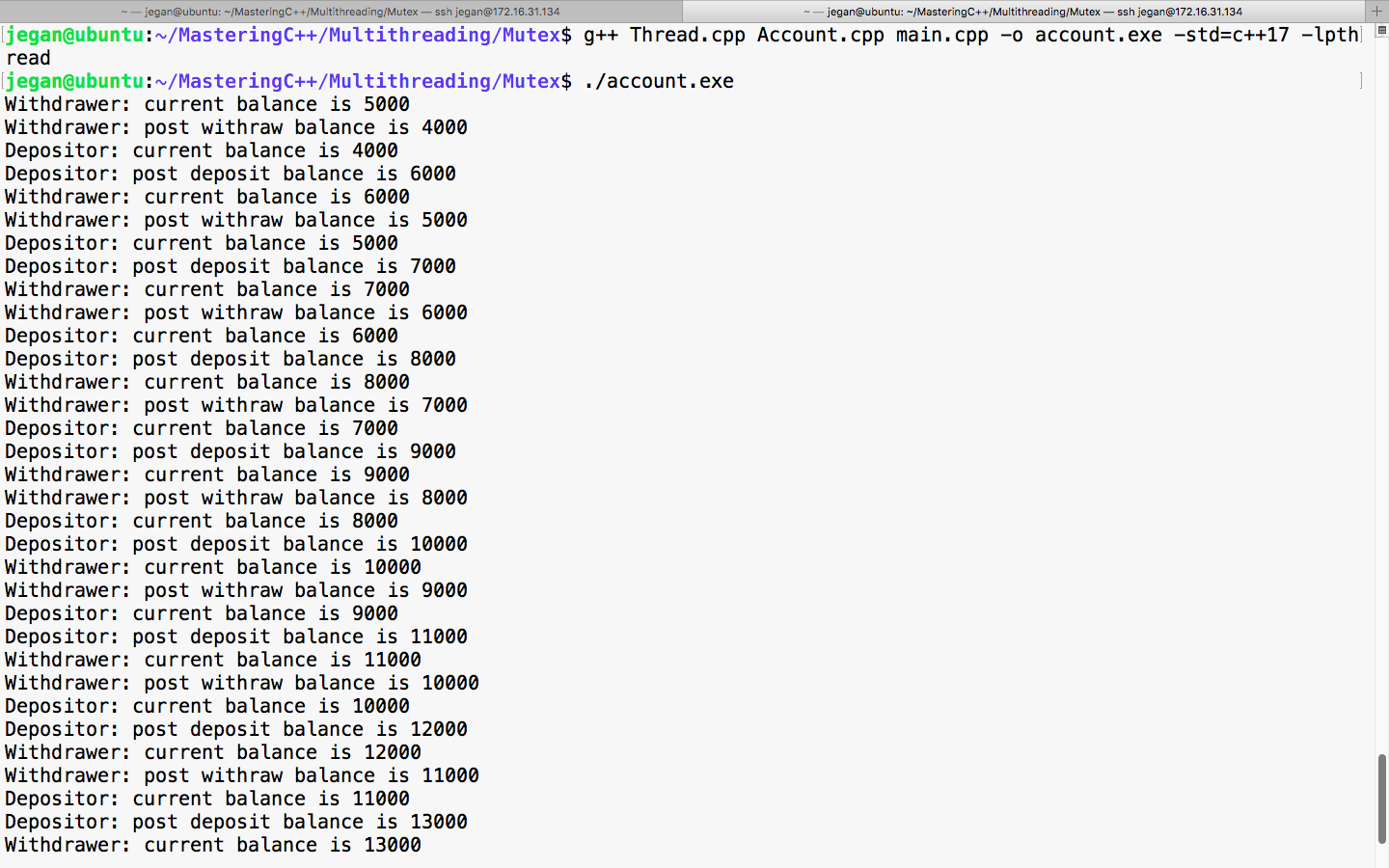

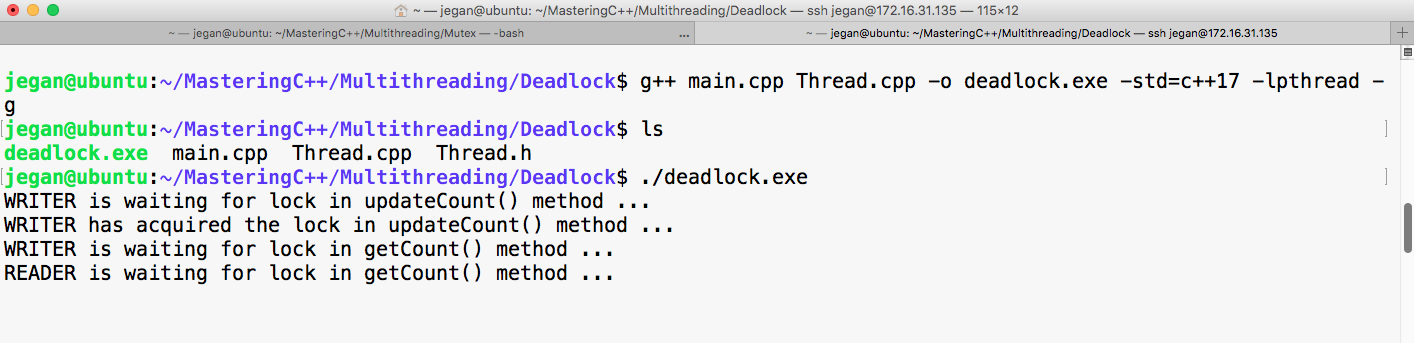

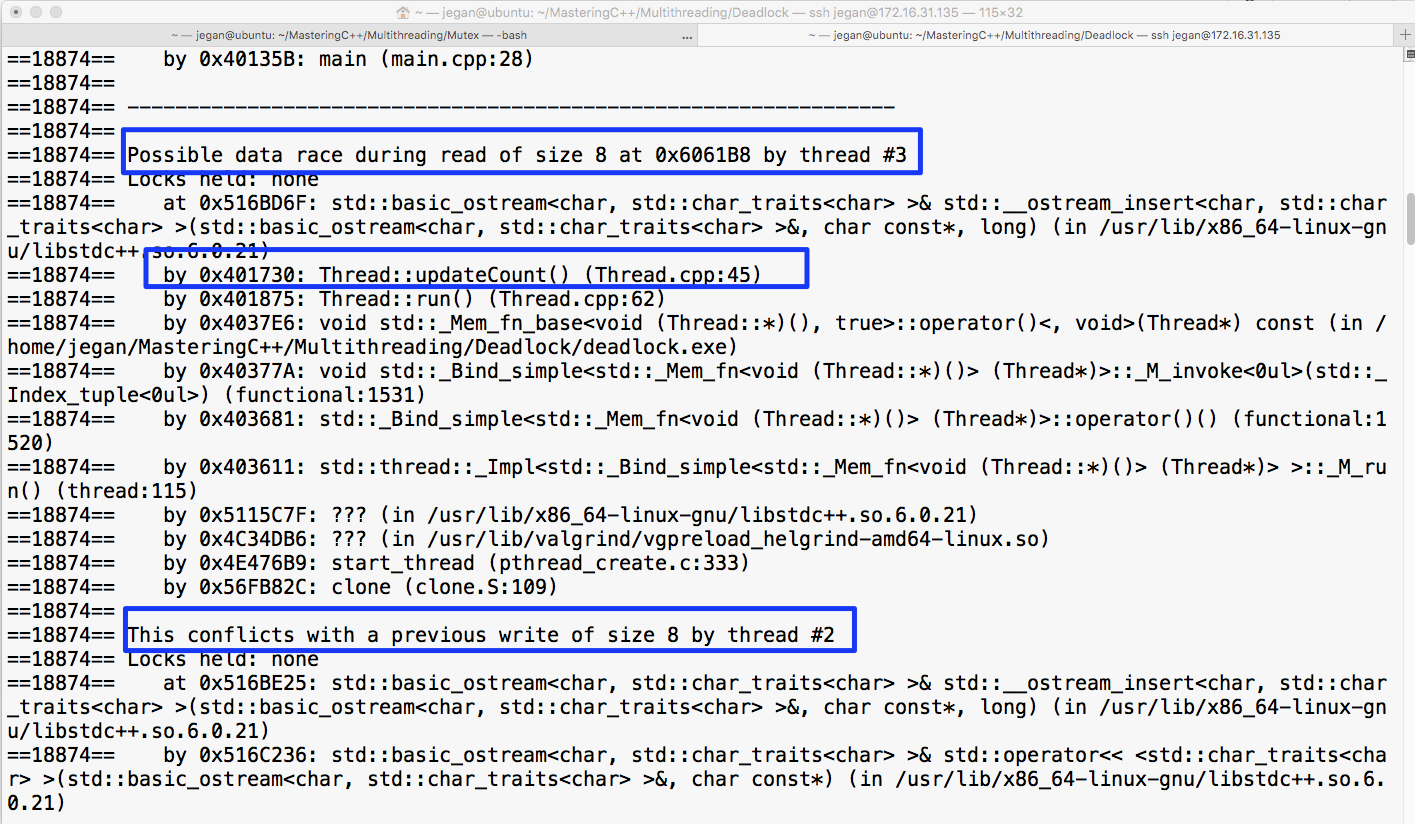

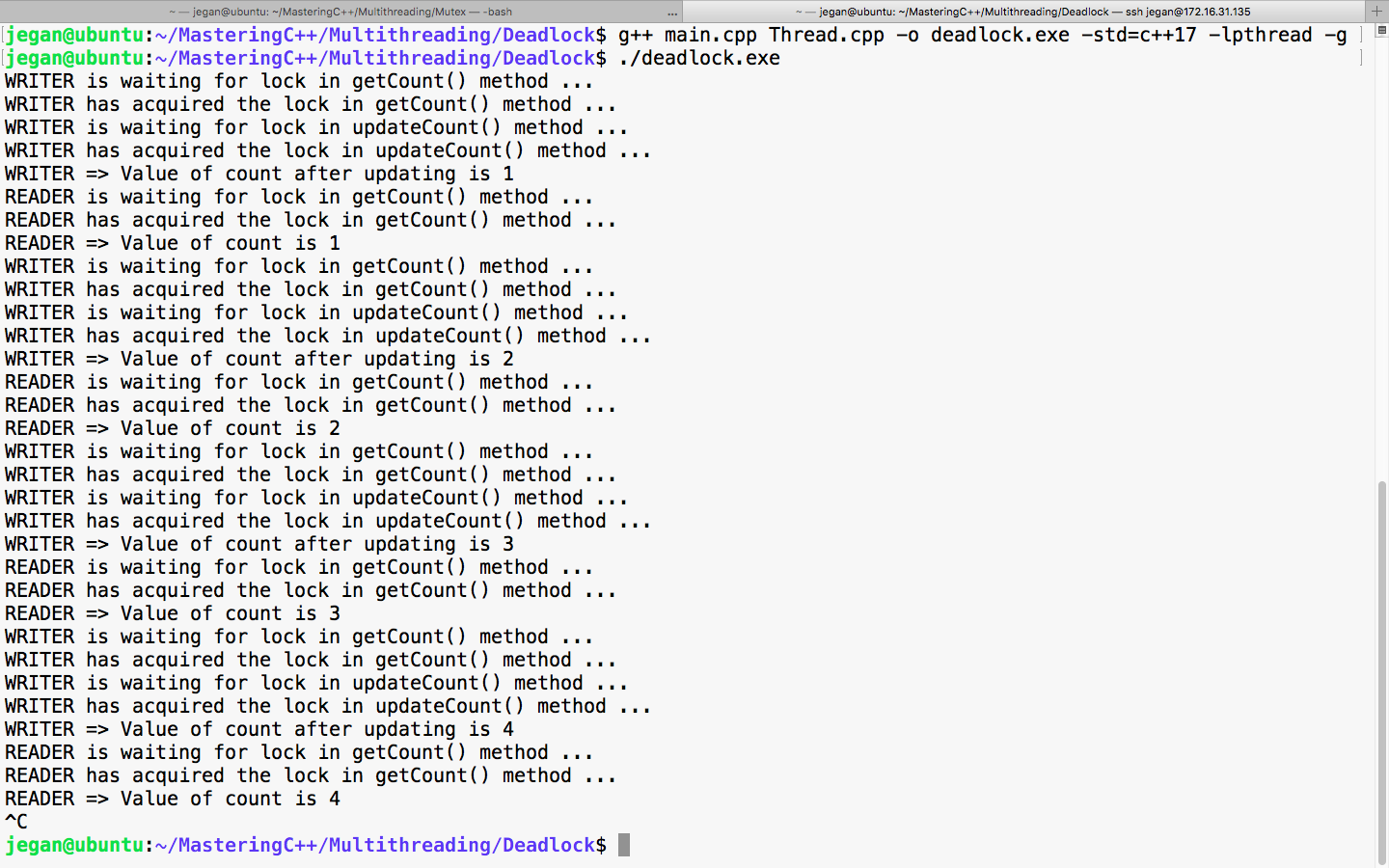

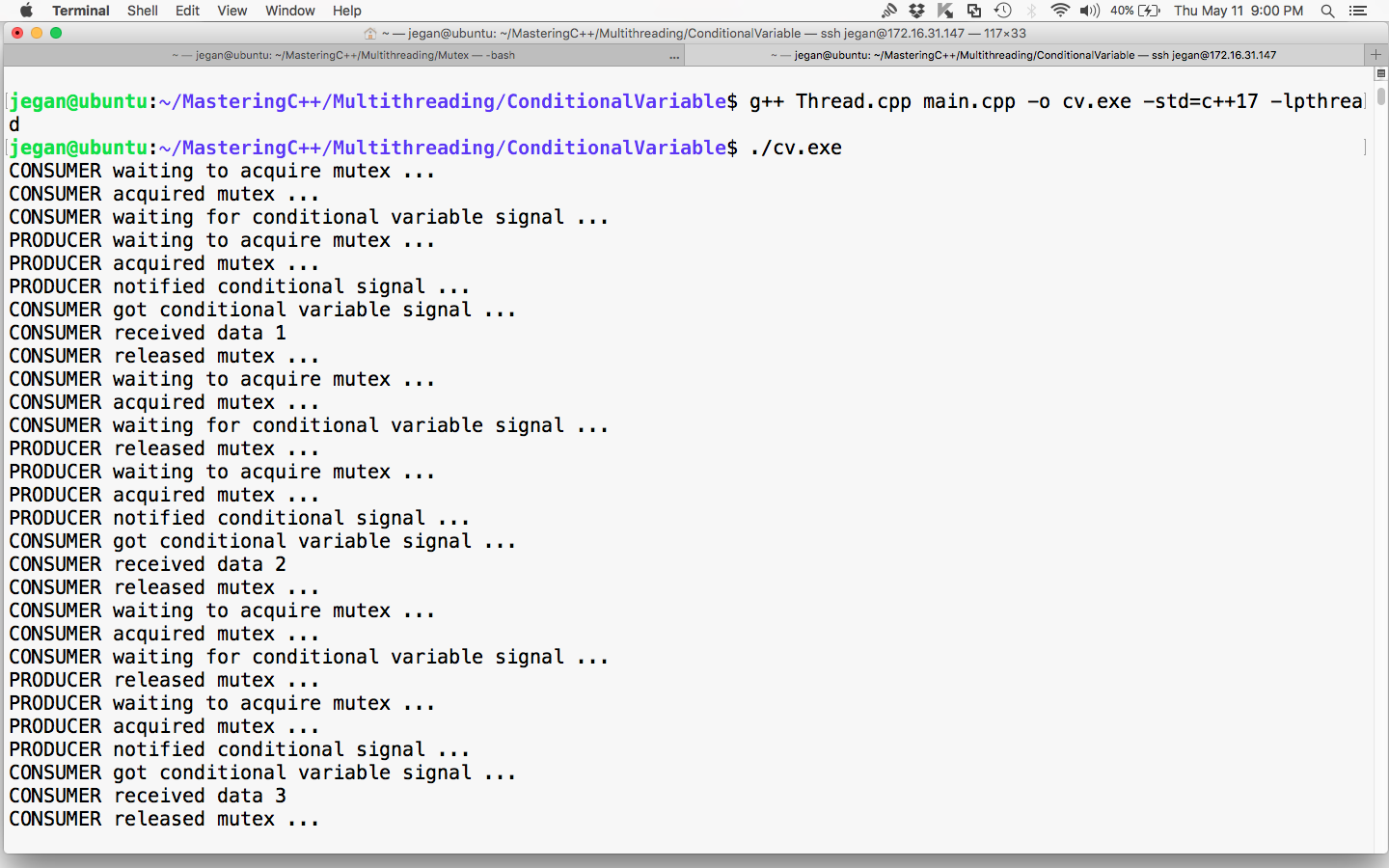

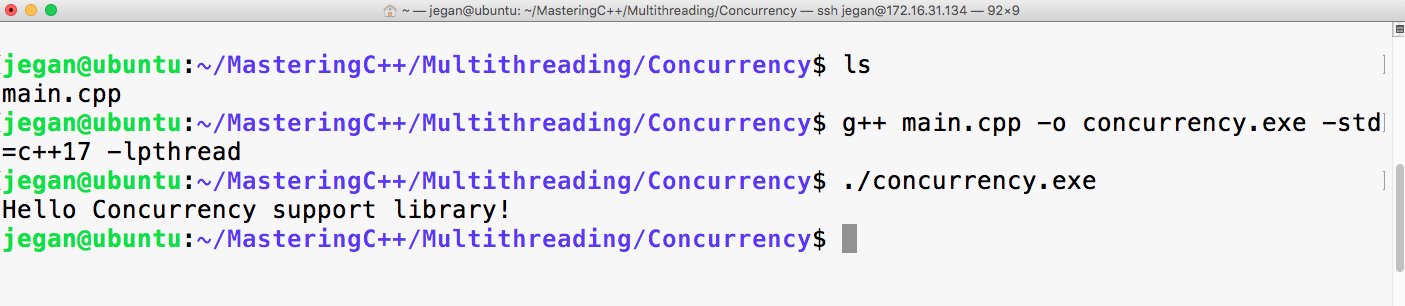

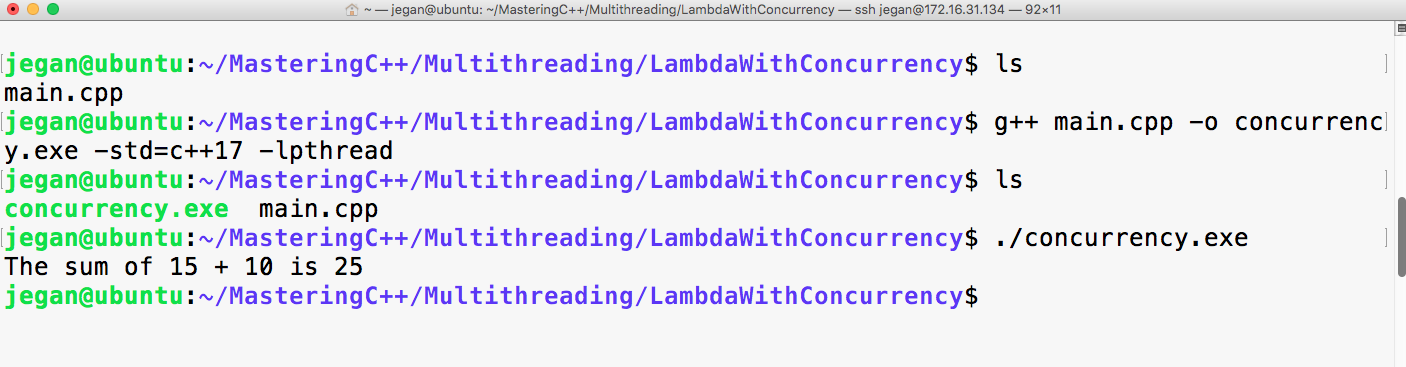

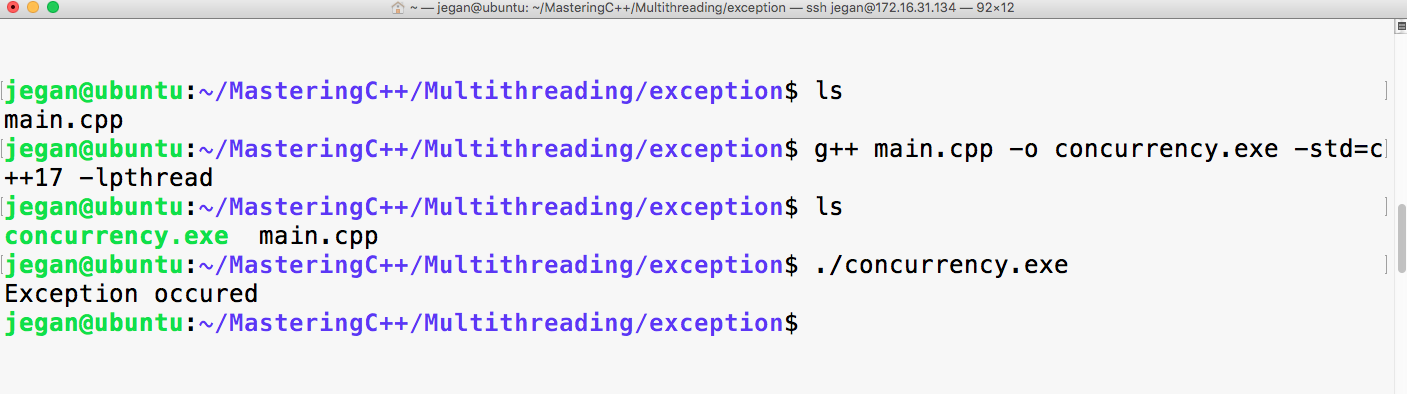

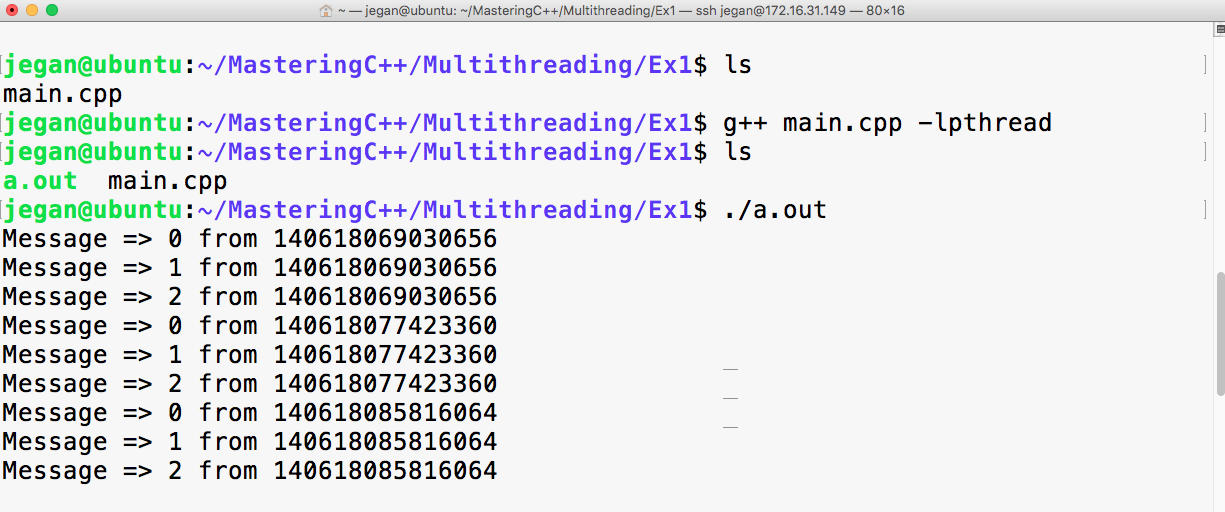

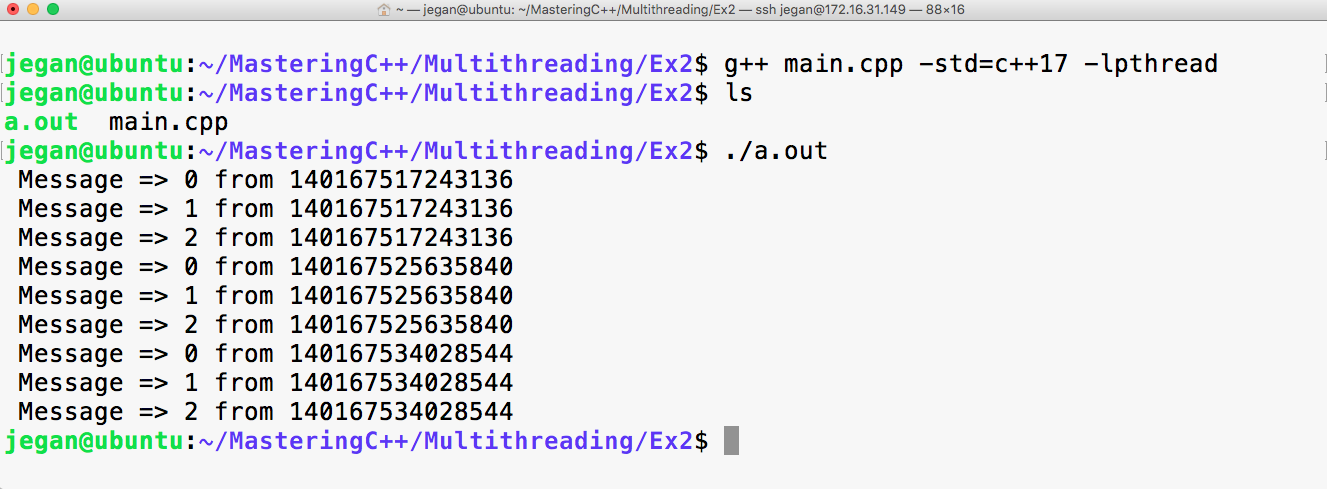

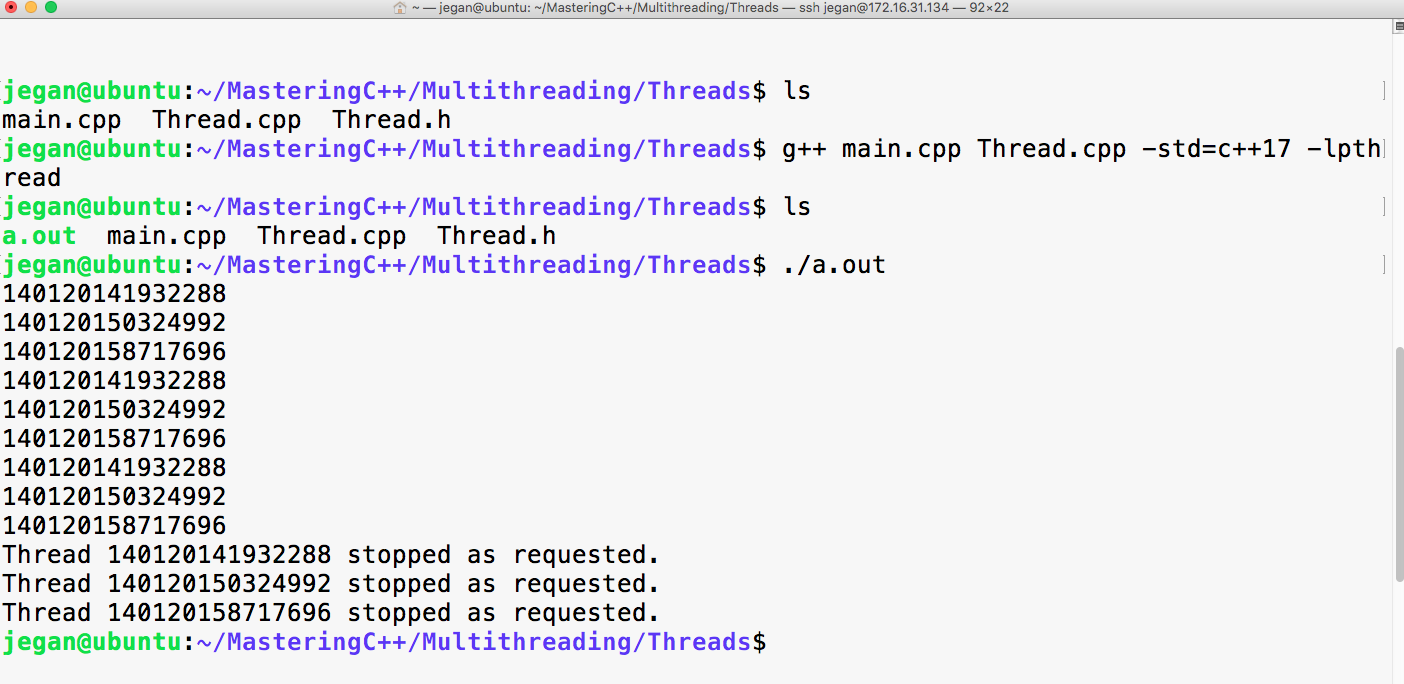

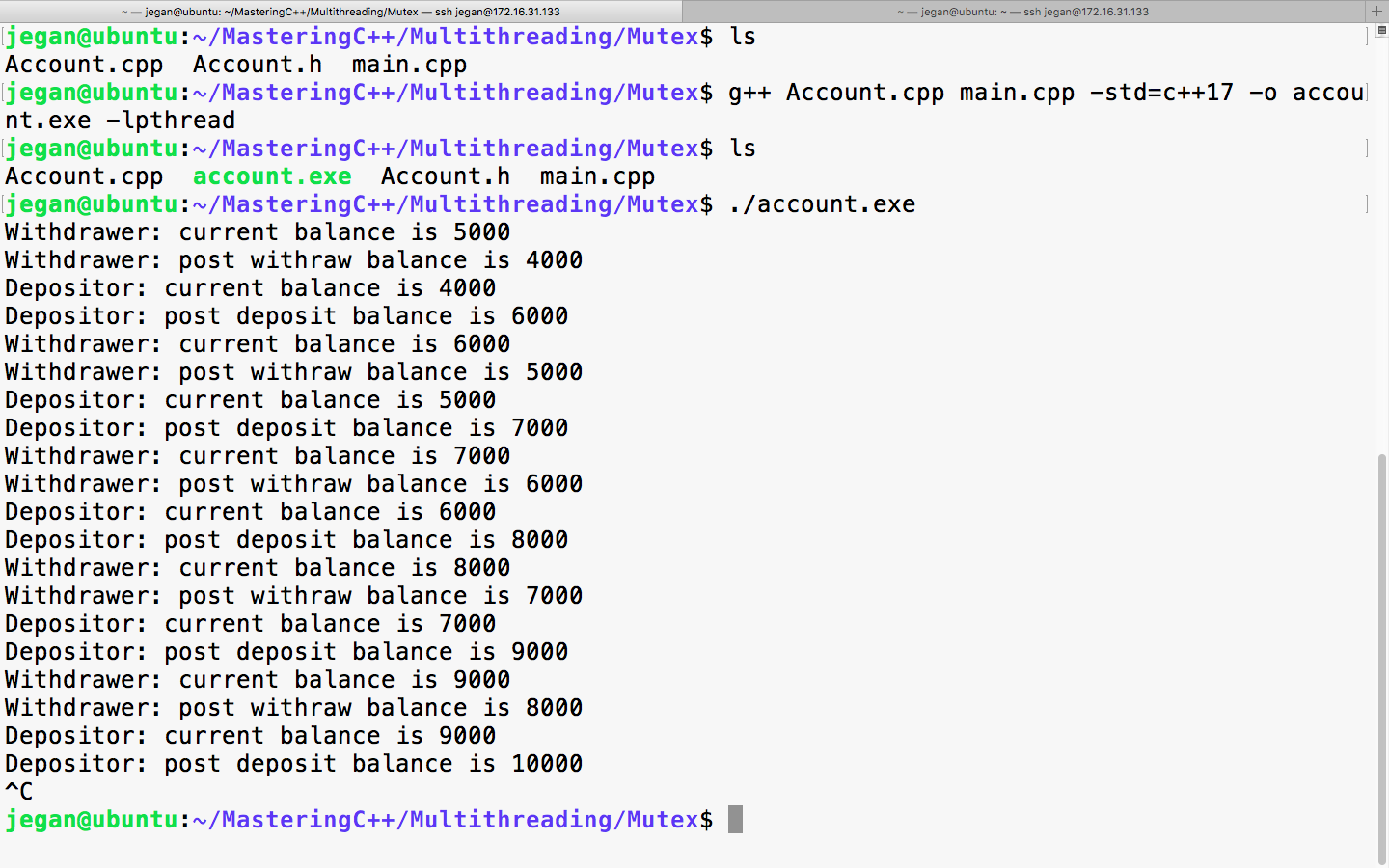

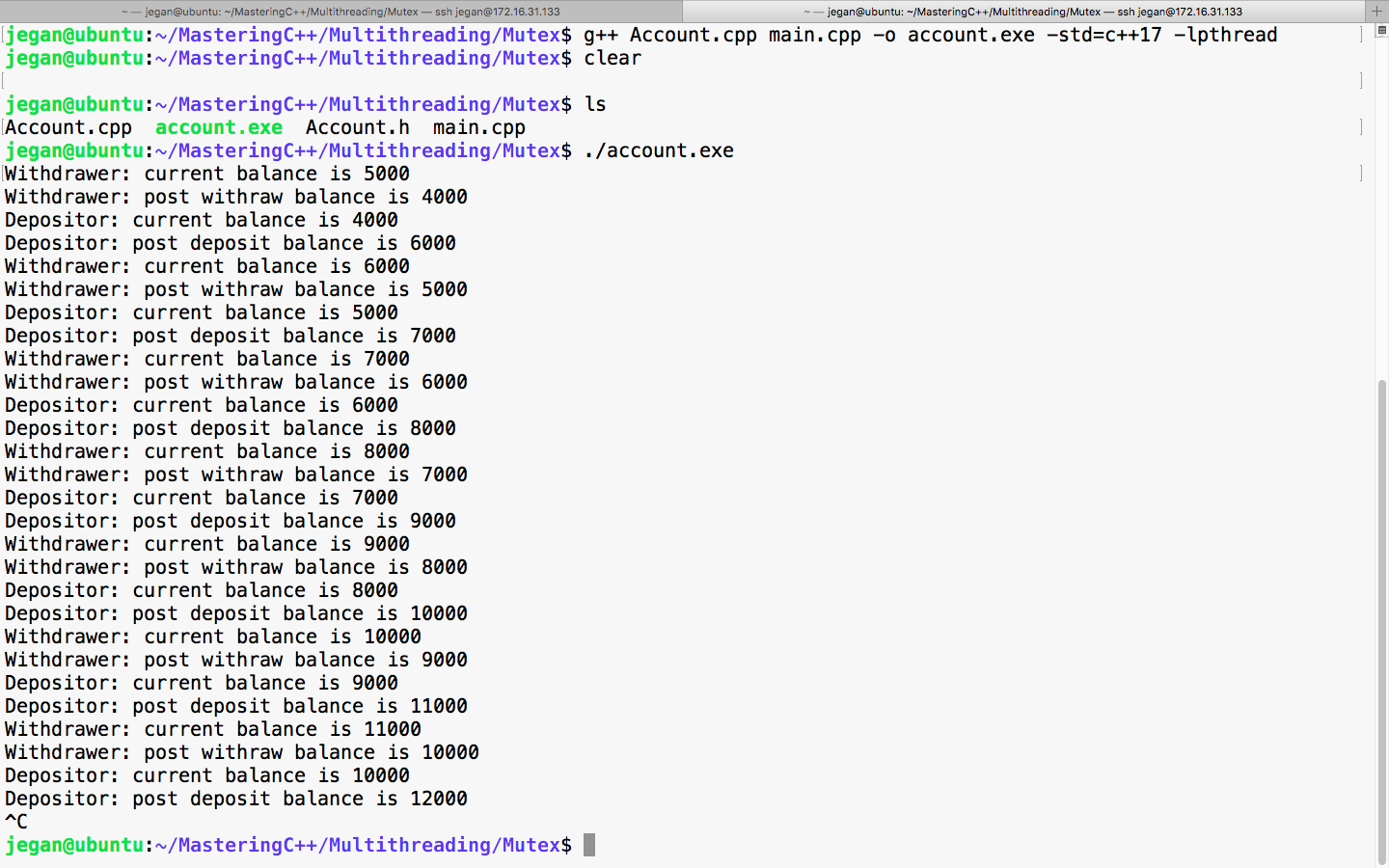

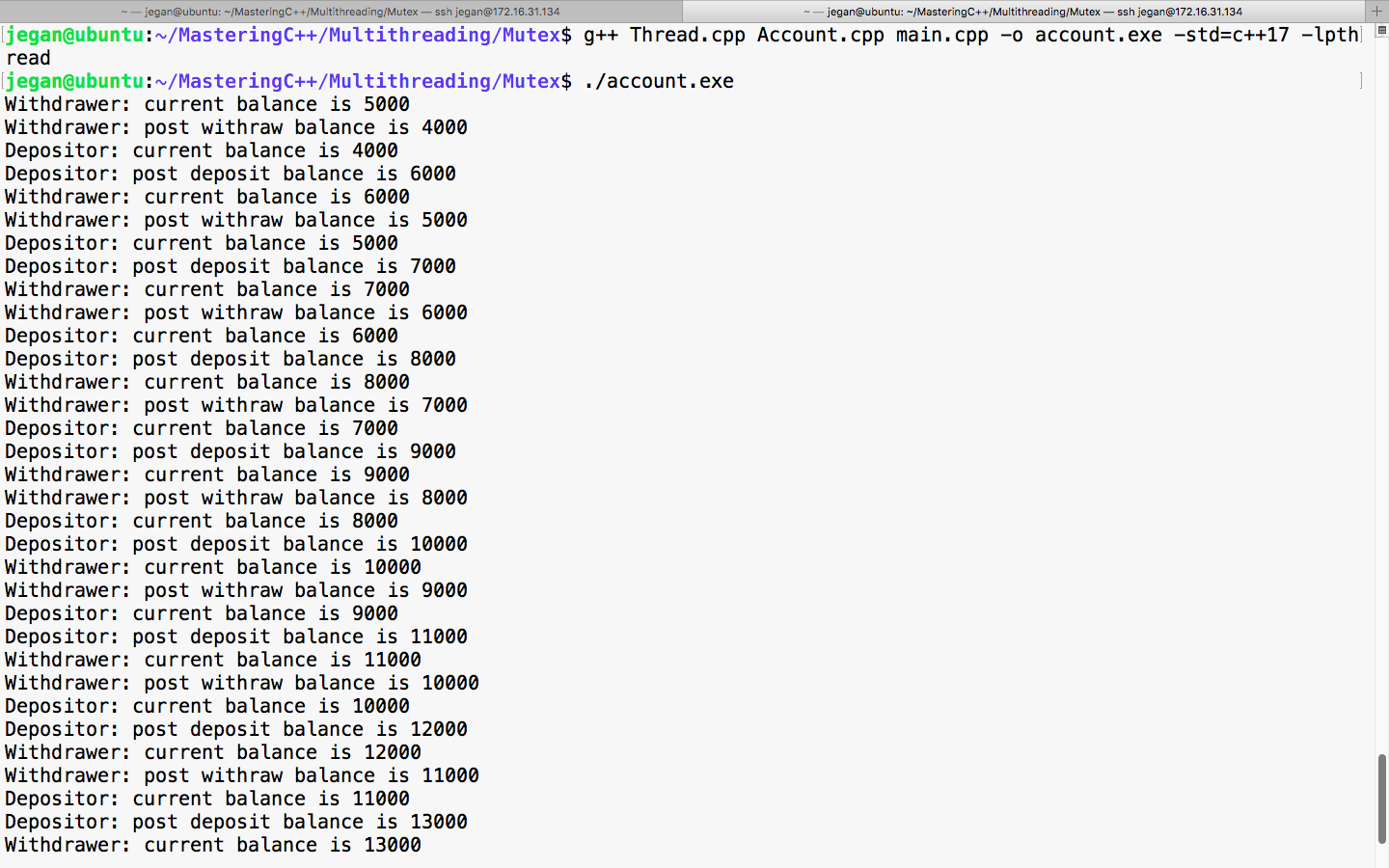

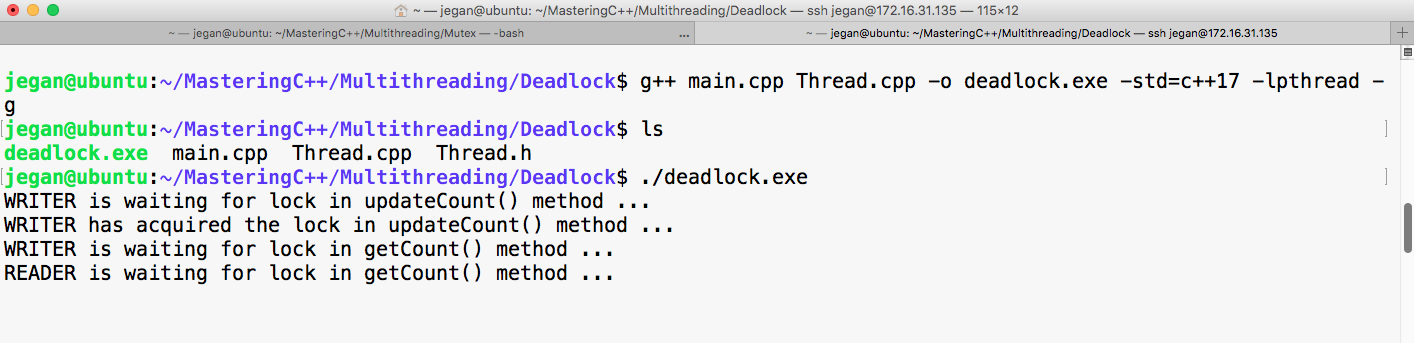

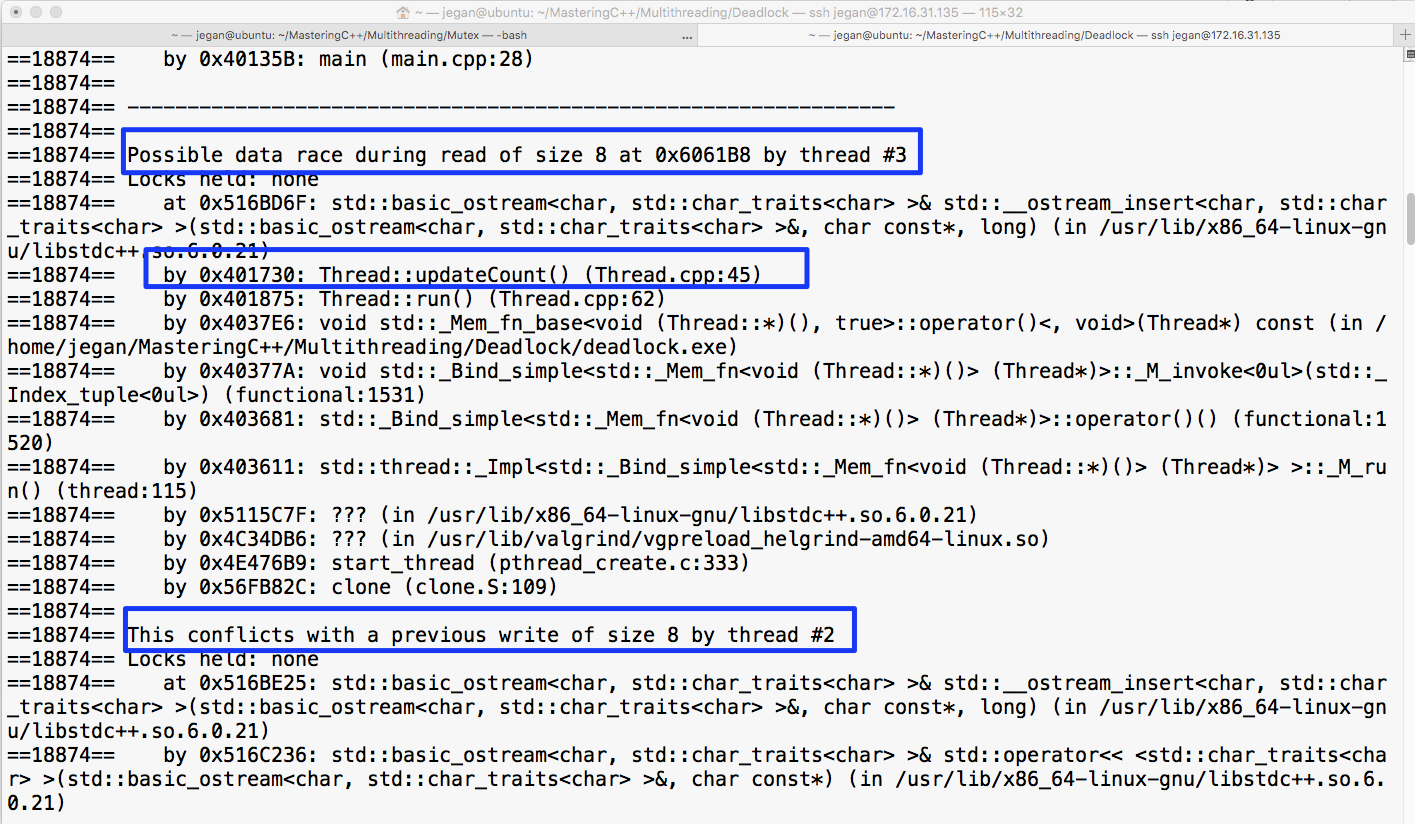

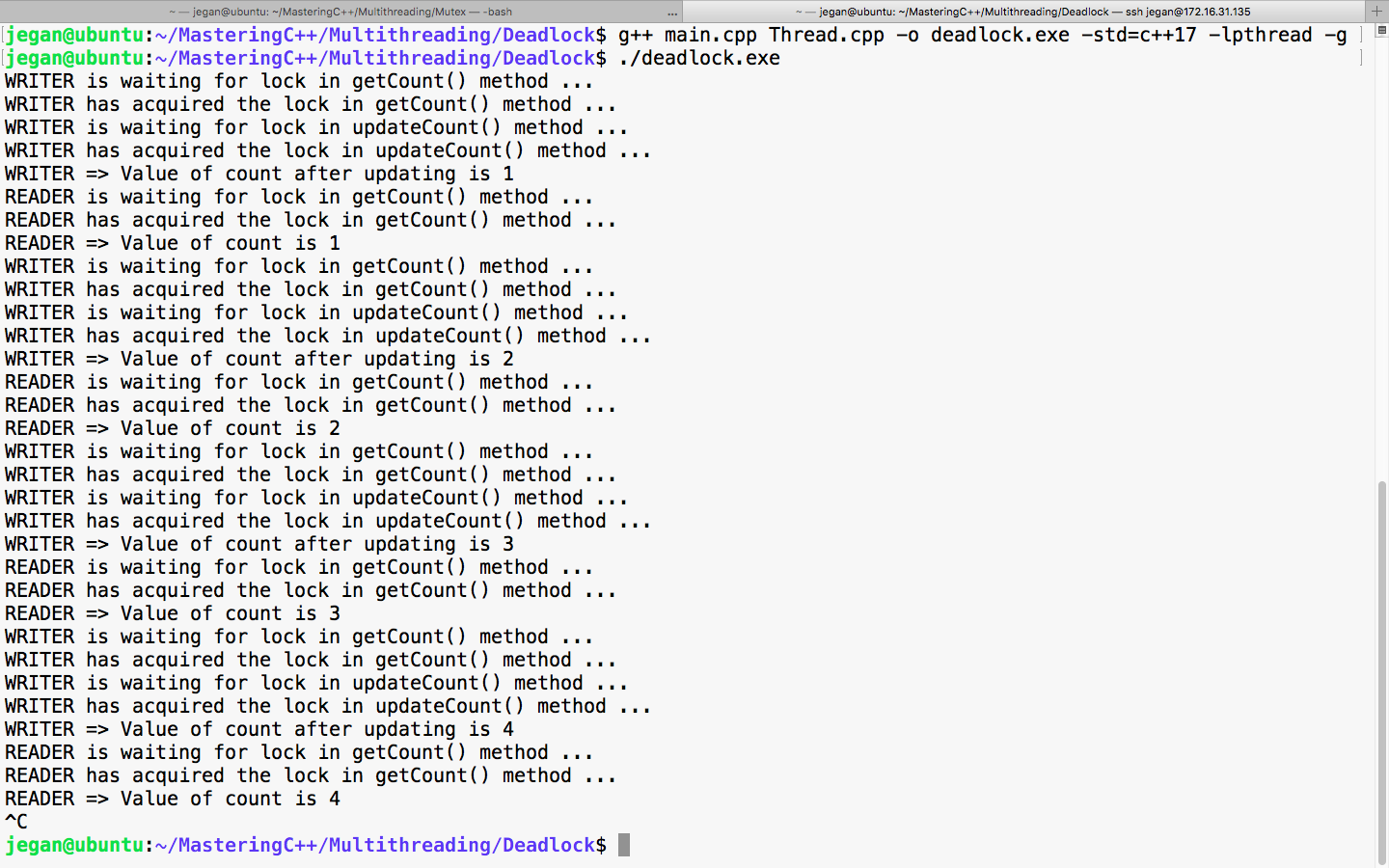

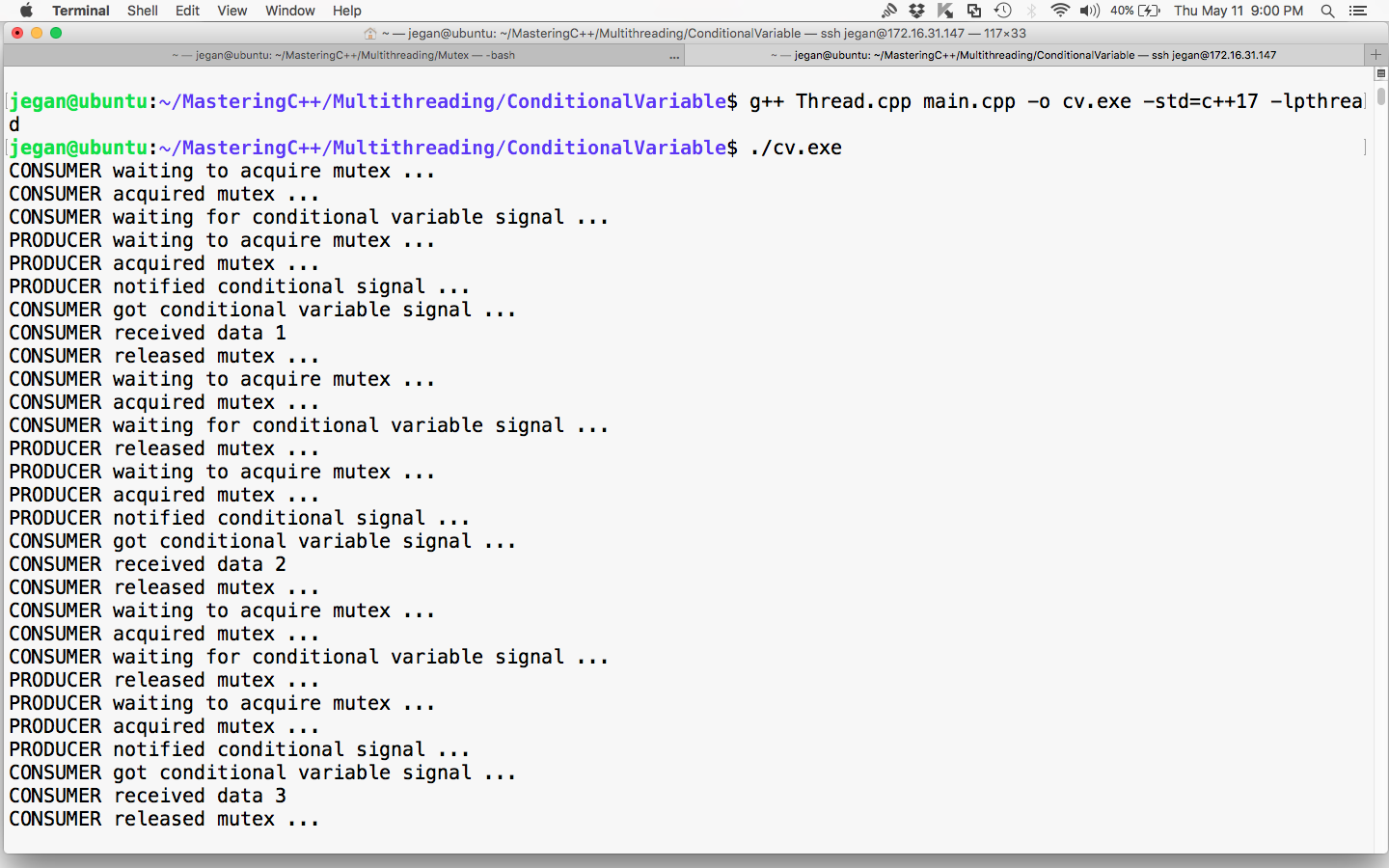

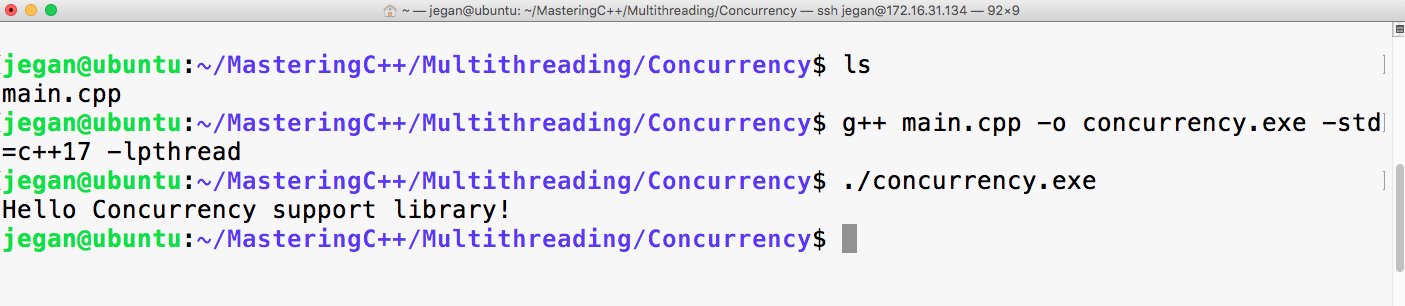

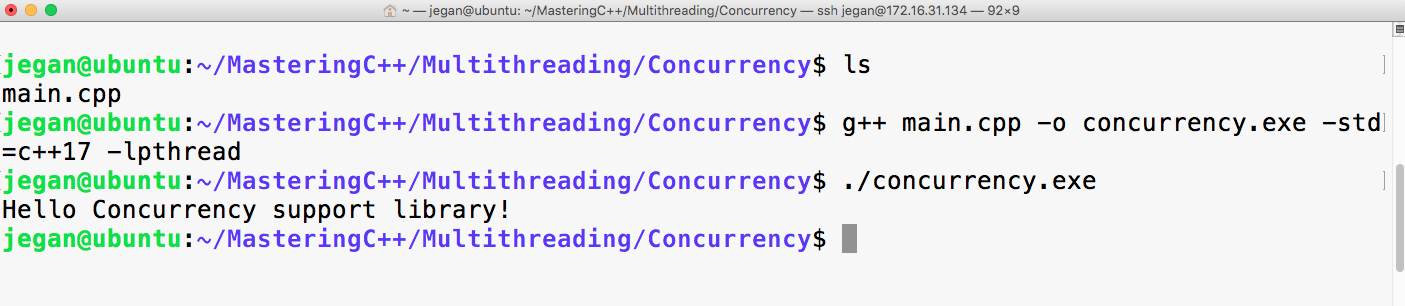

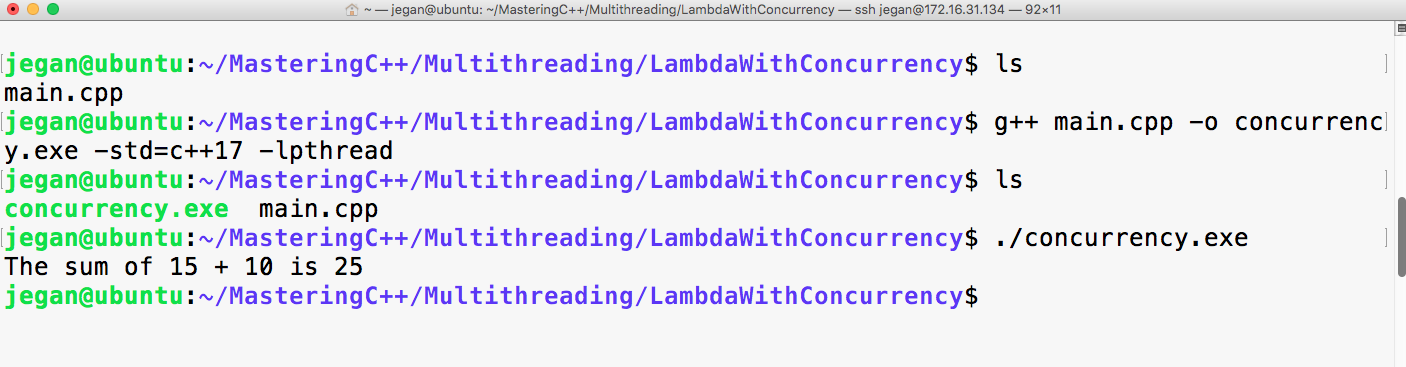

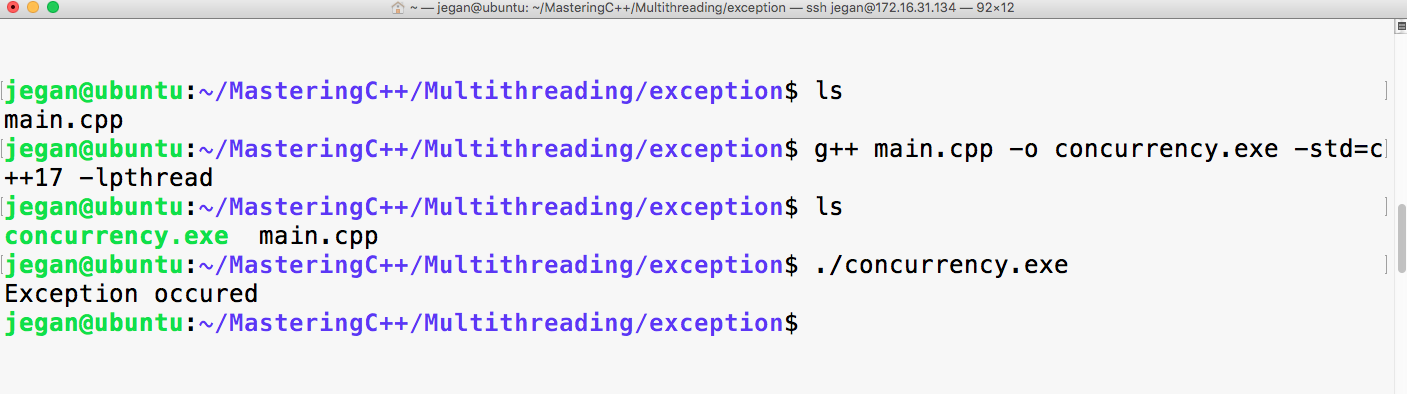

Chapter 6, Multithreaded Programming and Inter-Process Communication, introduces to the POSIX pthreads library and discusses the native C++ thread library. It also discusses the benefits of using the C++ thread library. Later, it helps you write multithreaded applications, explores ways to manage the threads, and explains the use of synchronization mechanisms. The chapter discusses deadlocks and possible solutions. Toward the end of the chapter, it introduces you to the concurrency library.

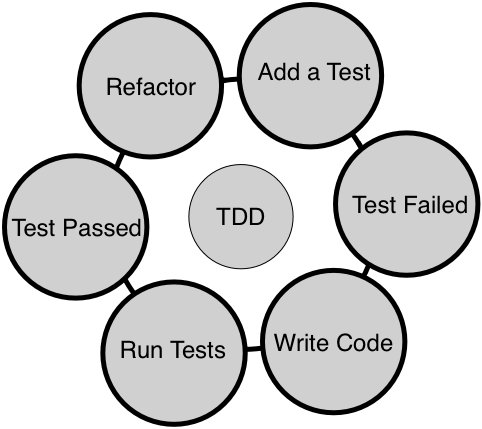

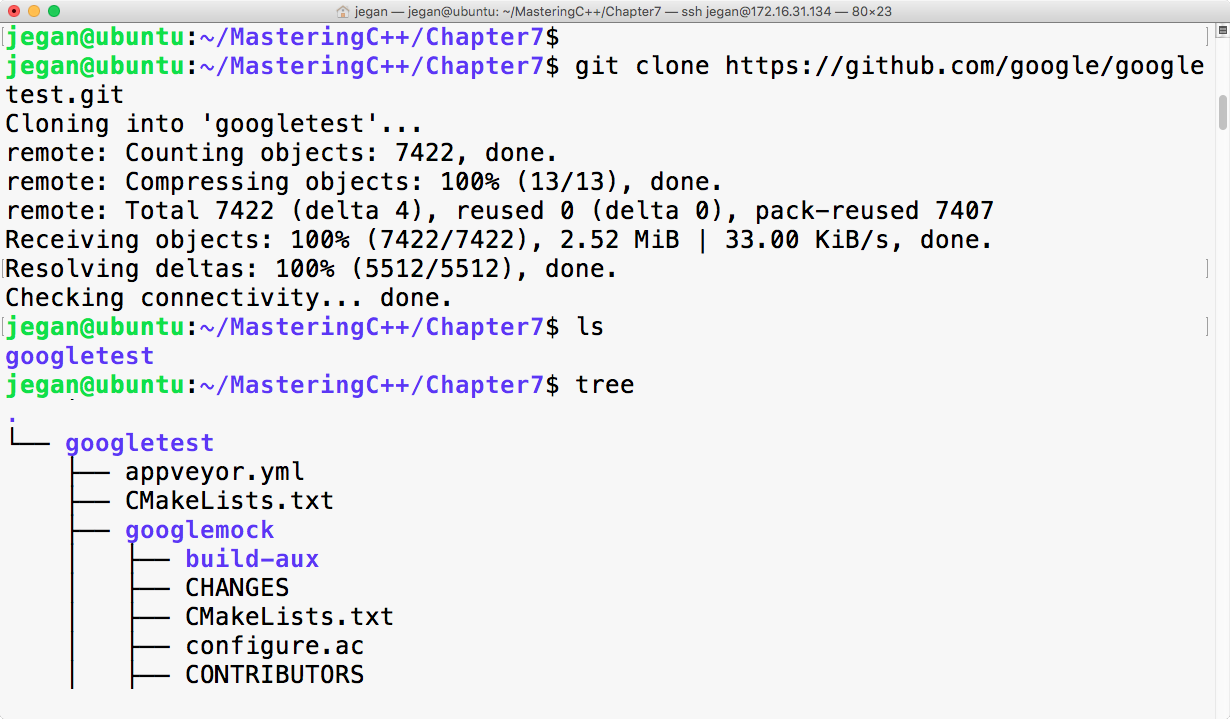

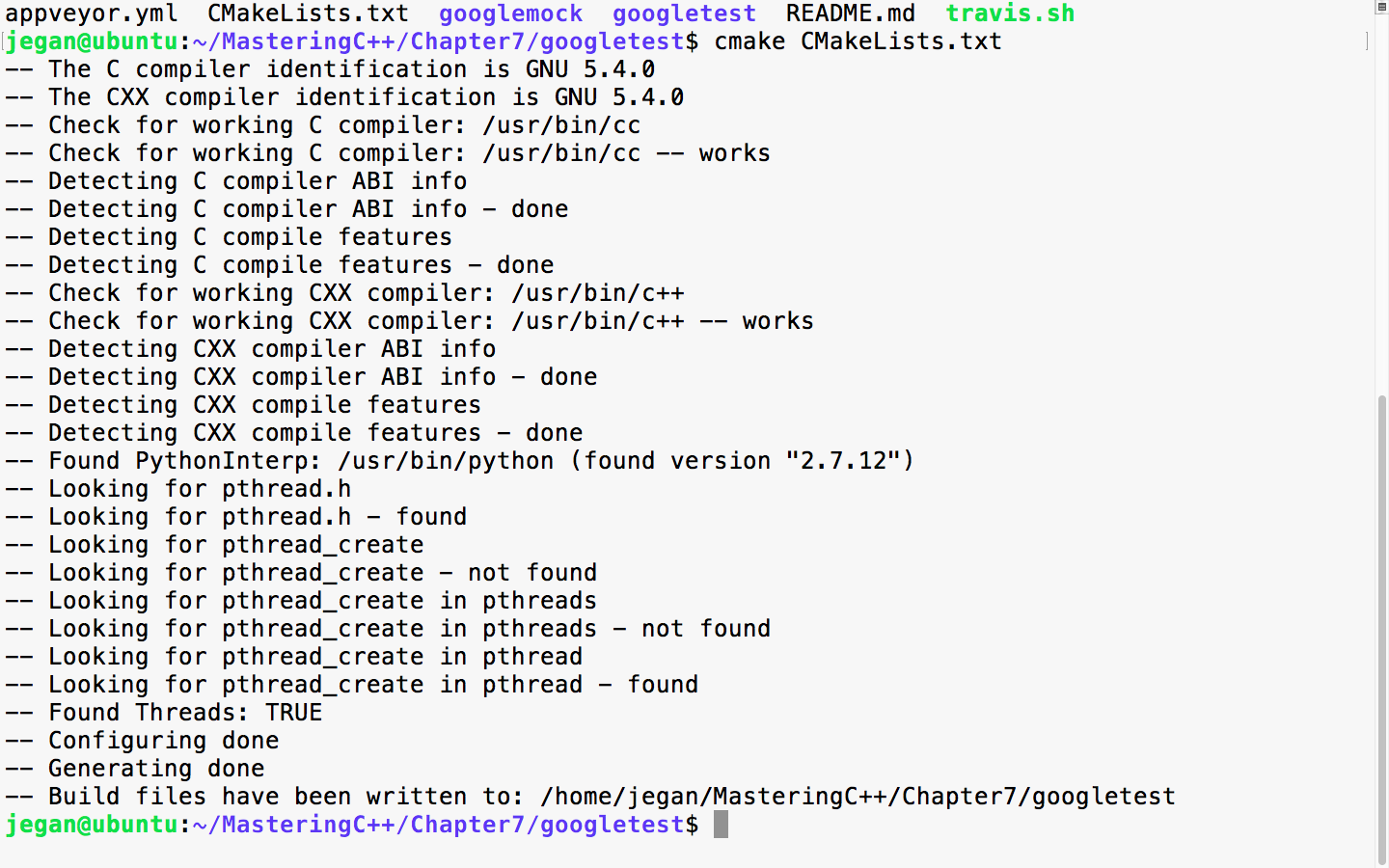

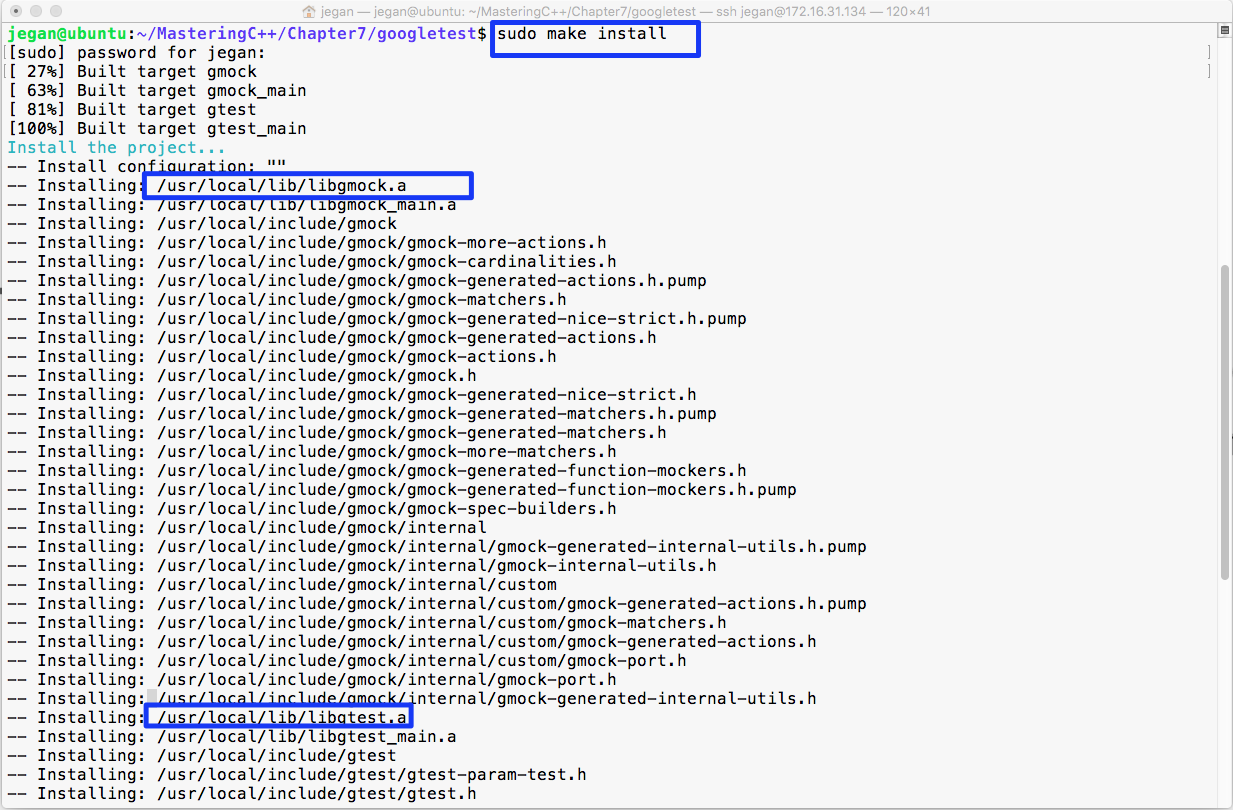

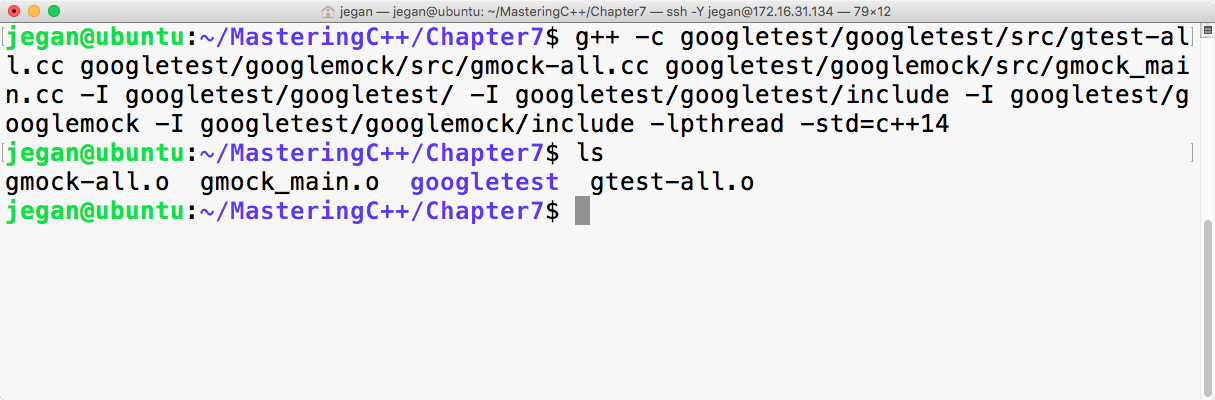

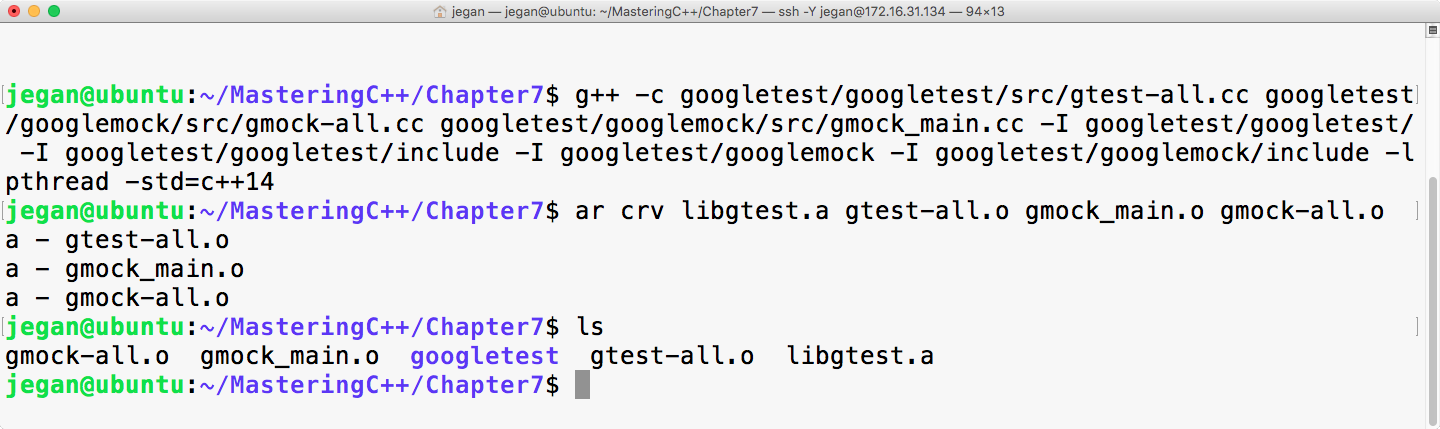

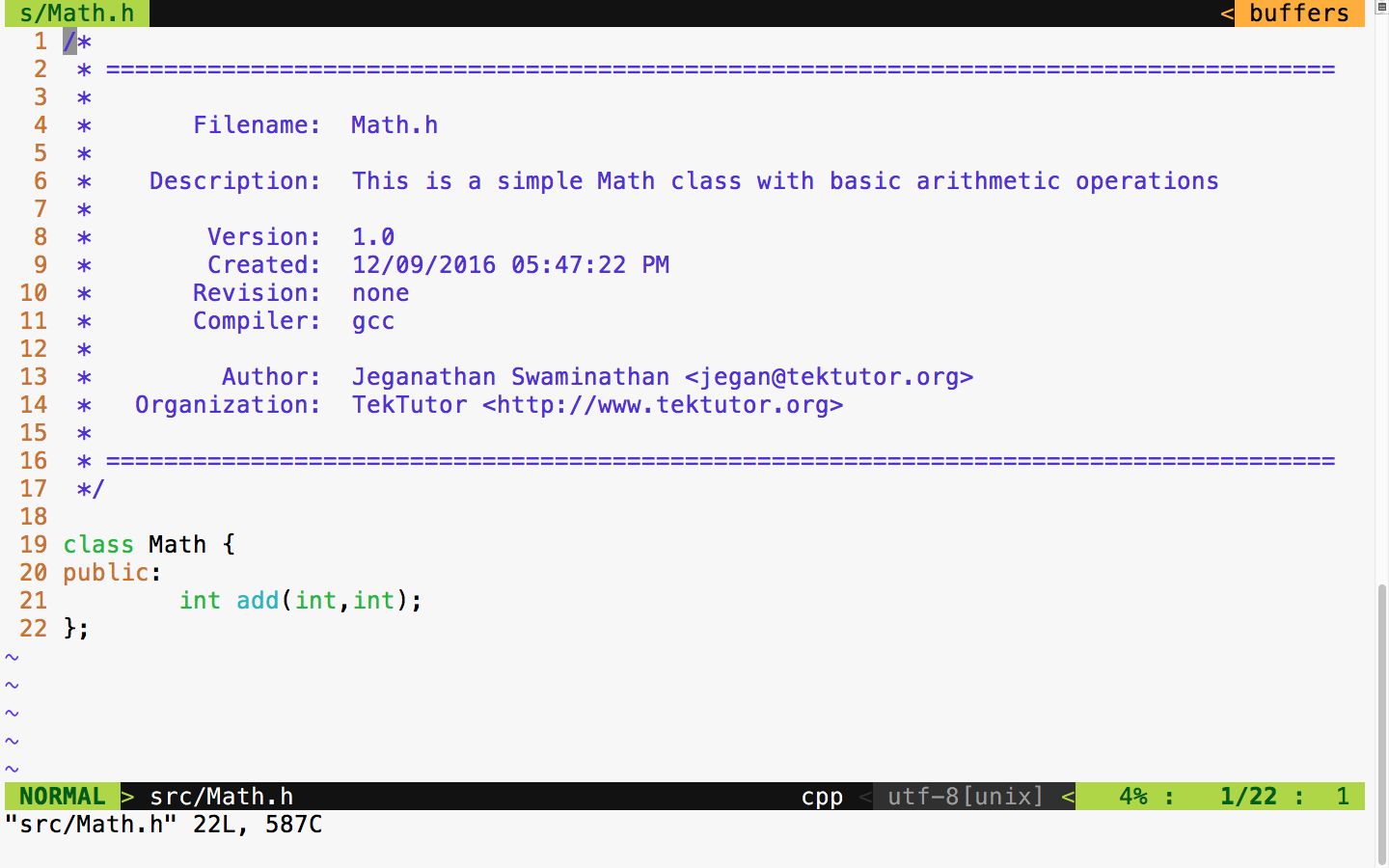

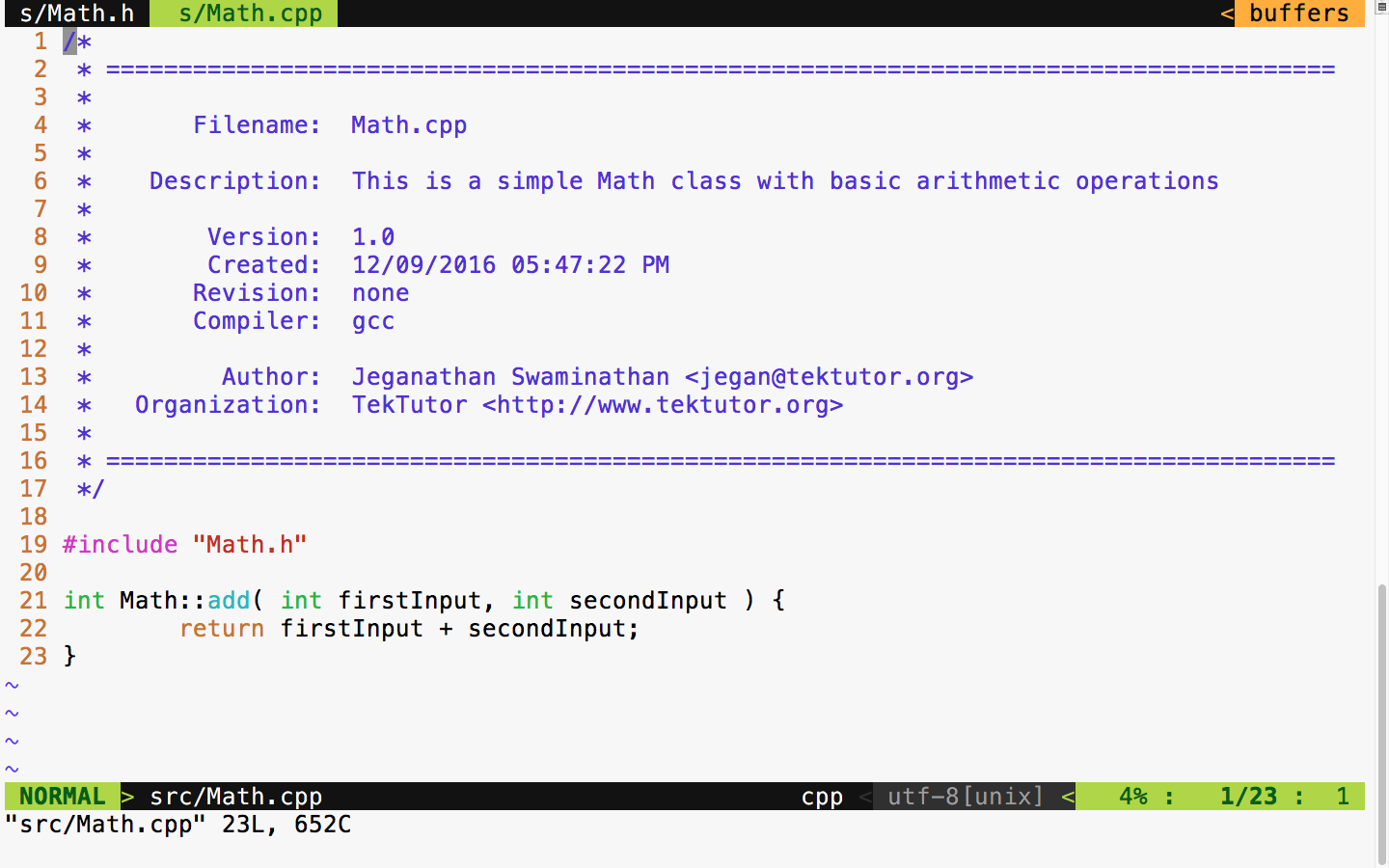

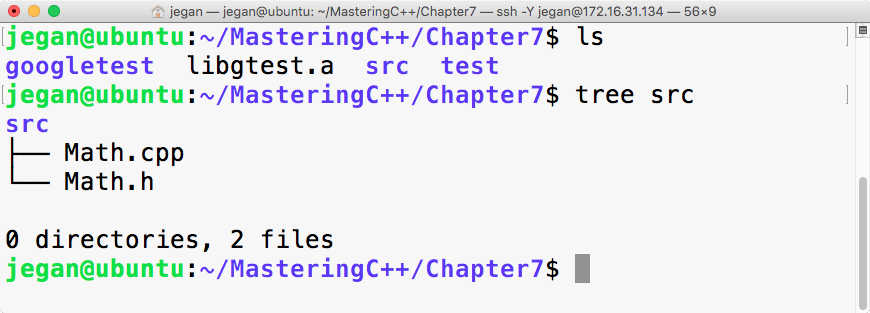

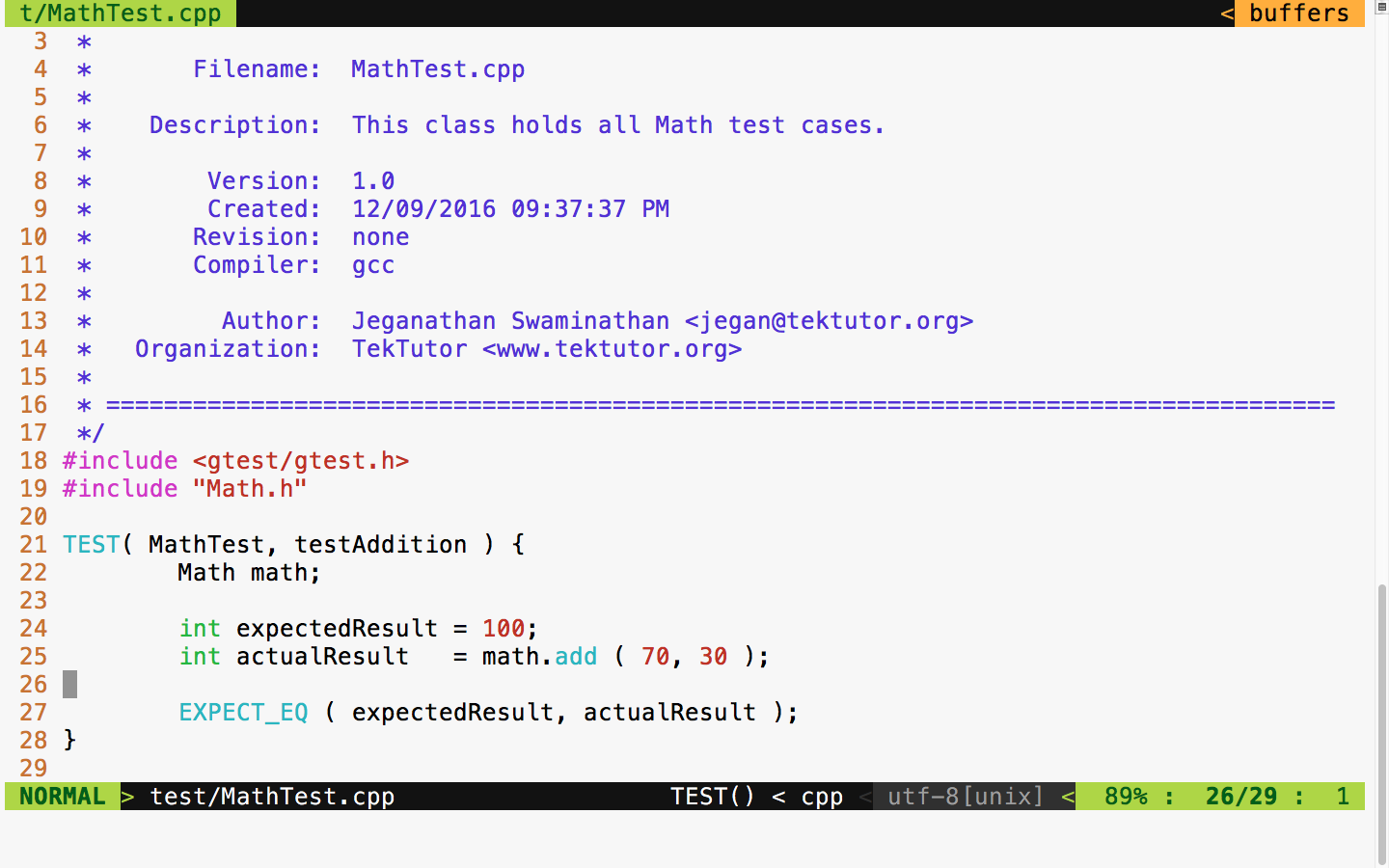

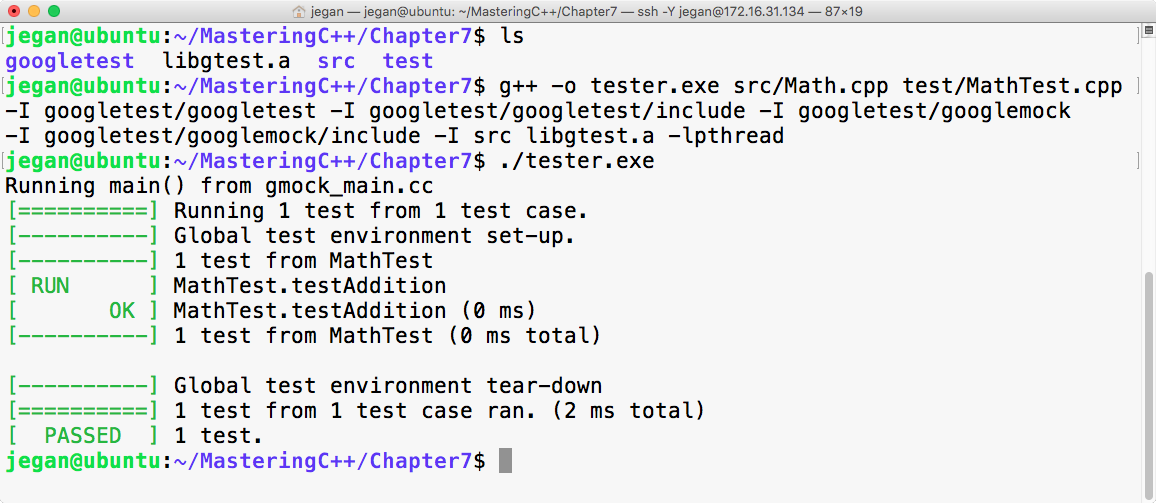

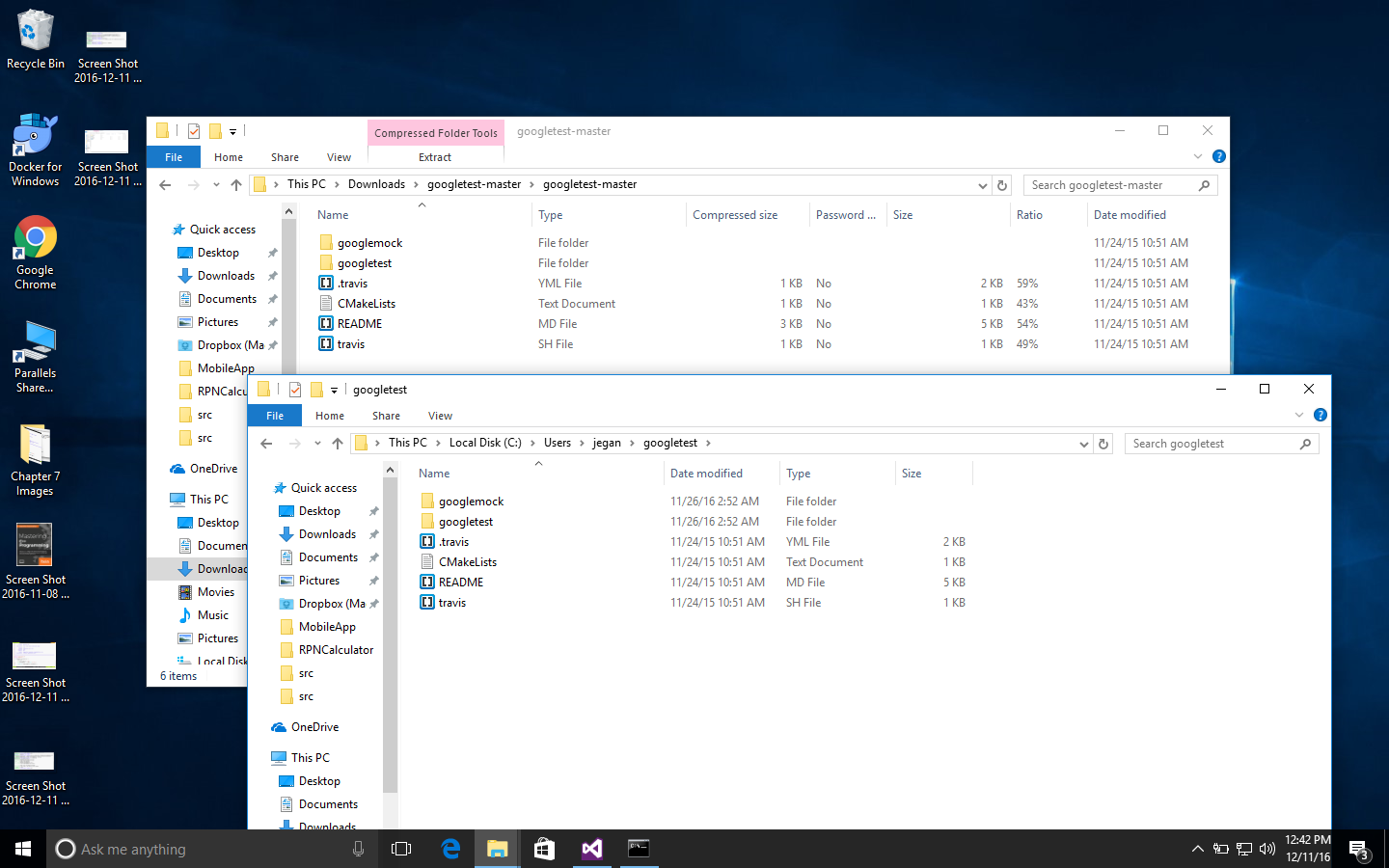

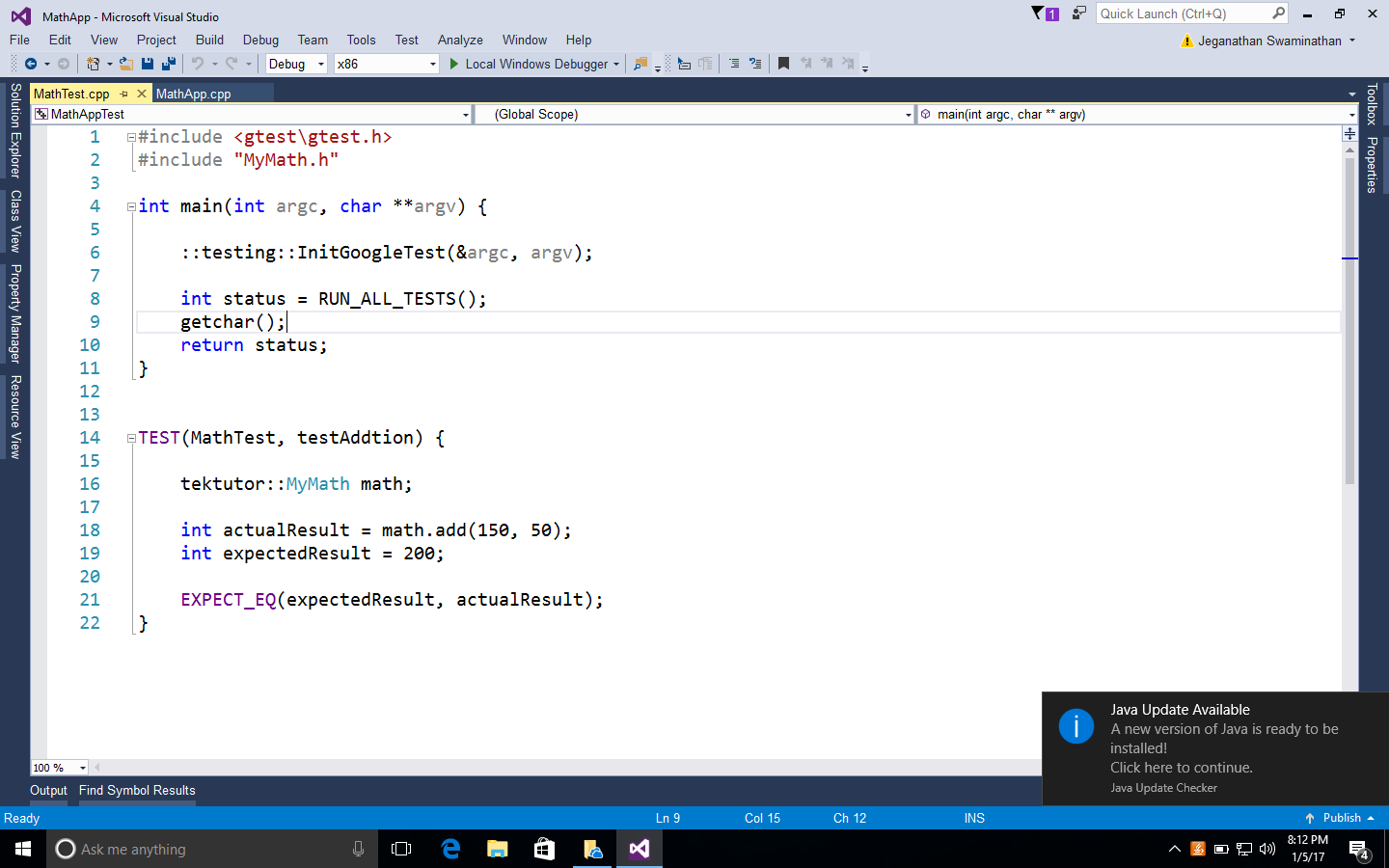

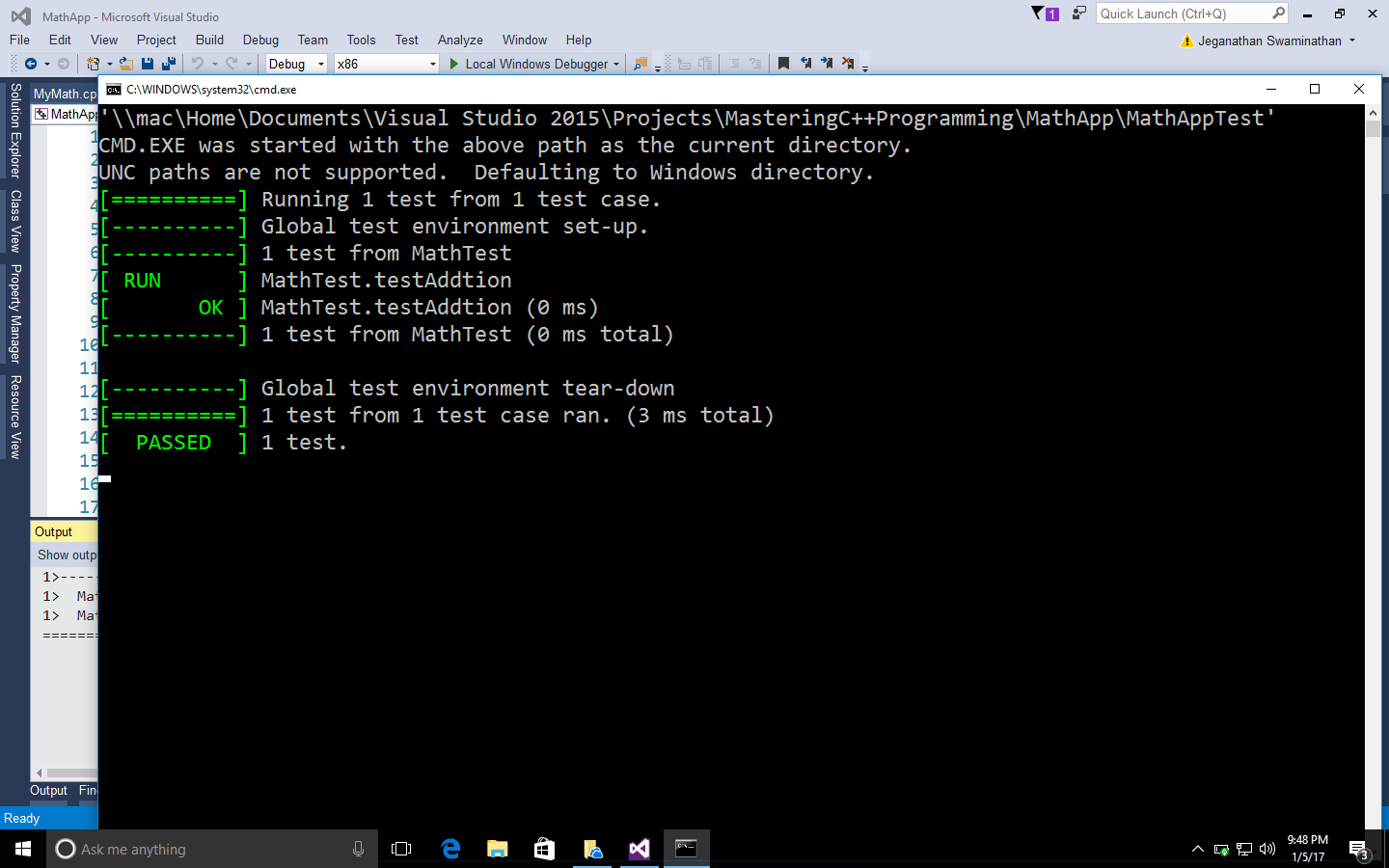

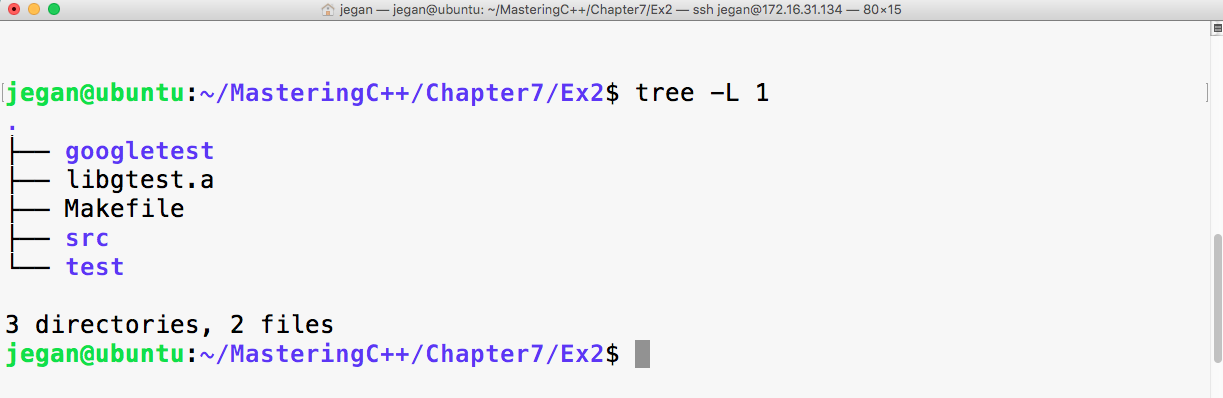

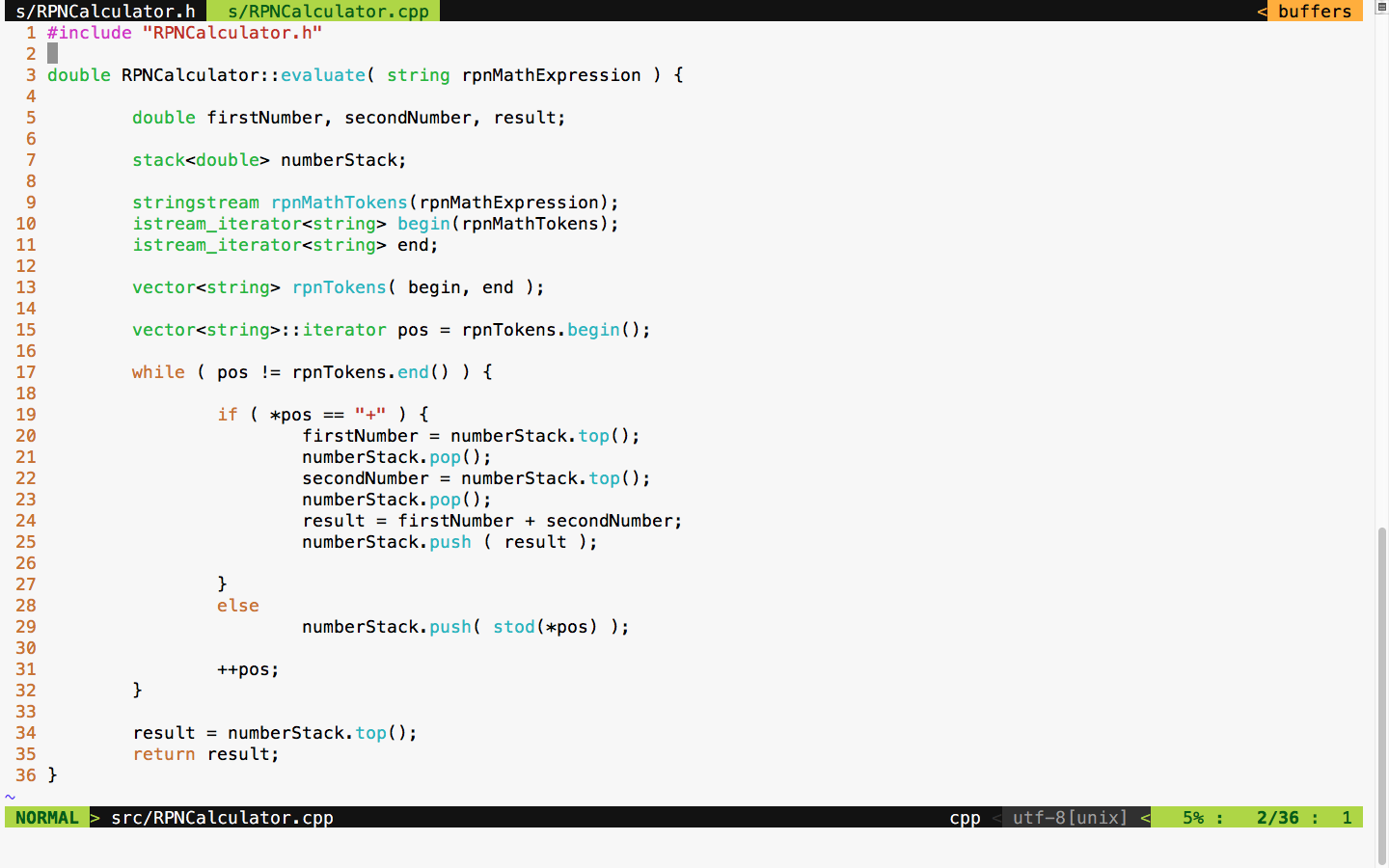

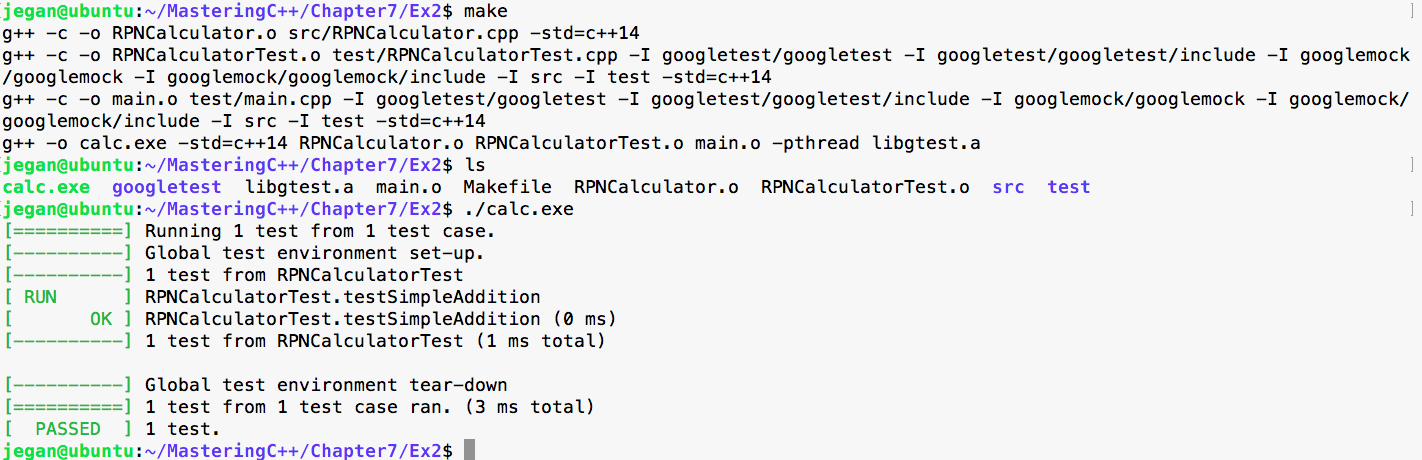

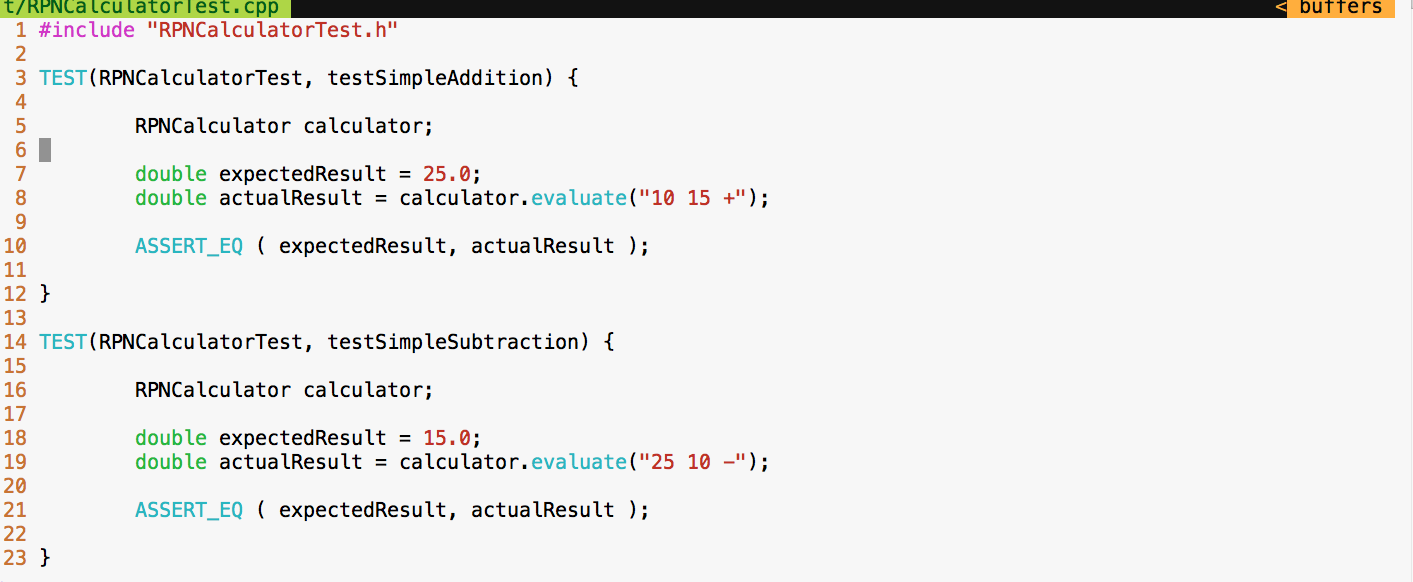

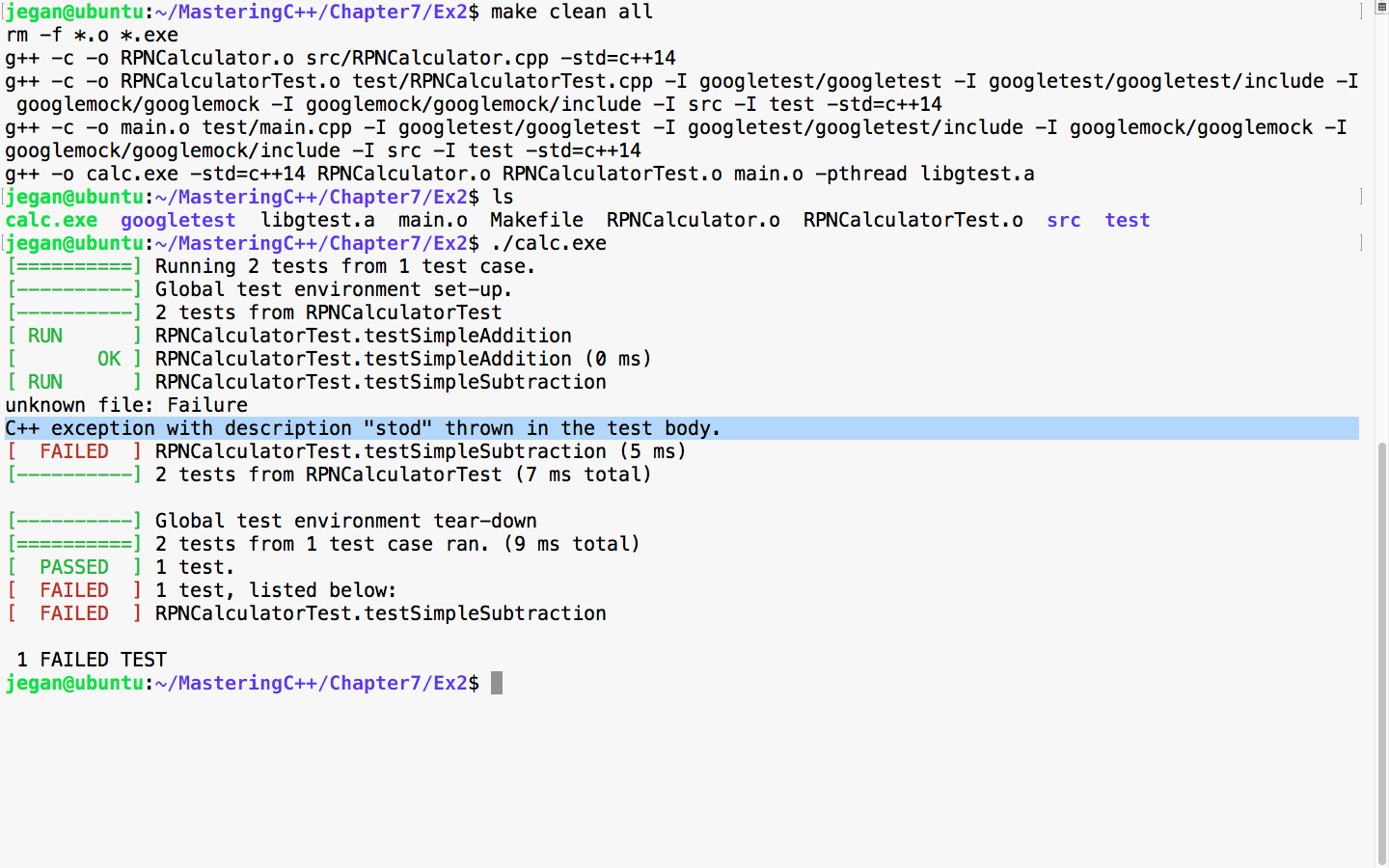

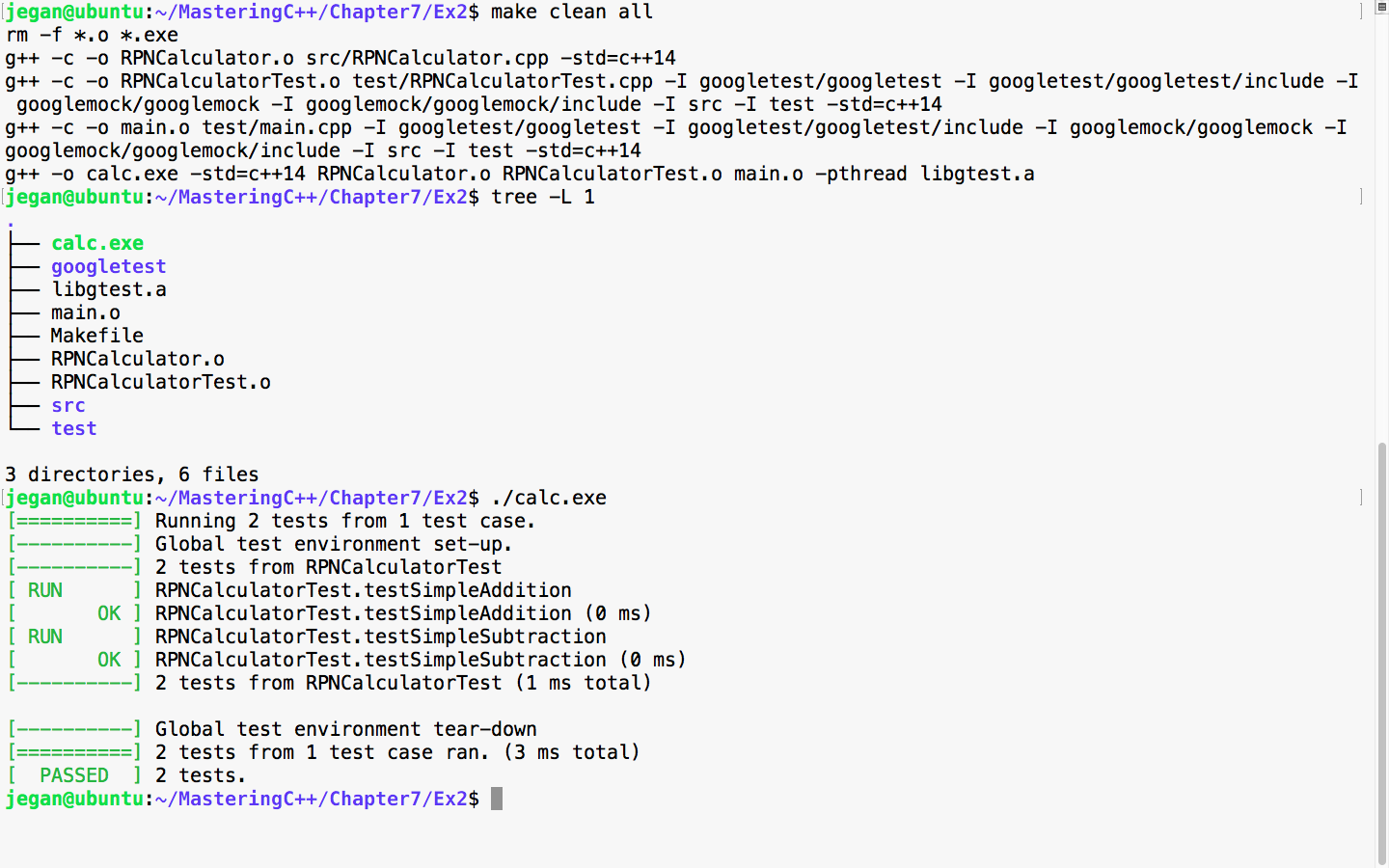

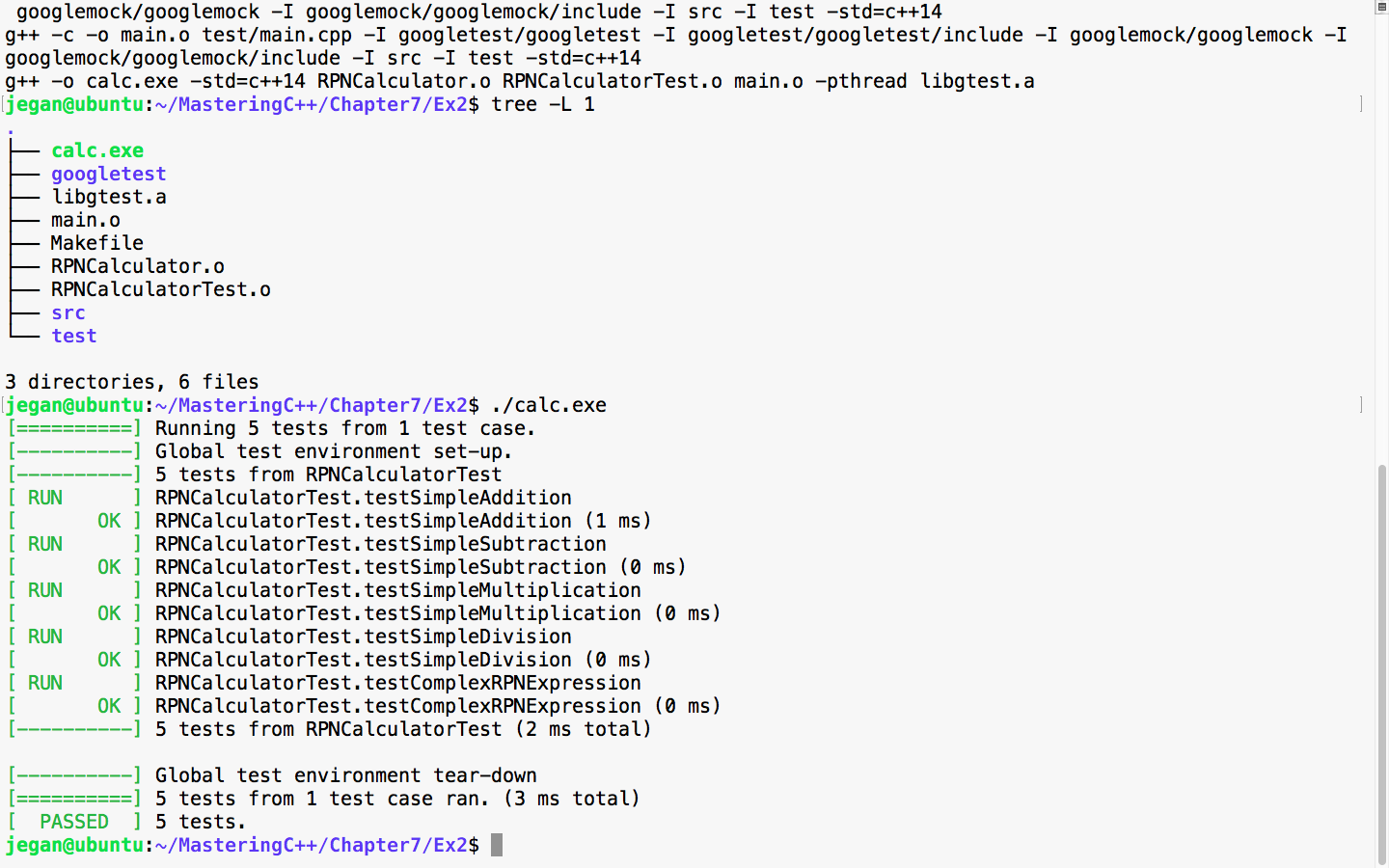

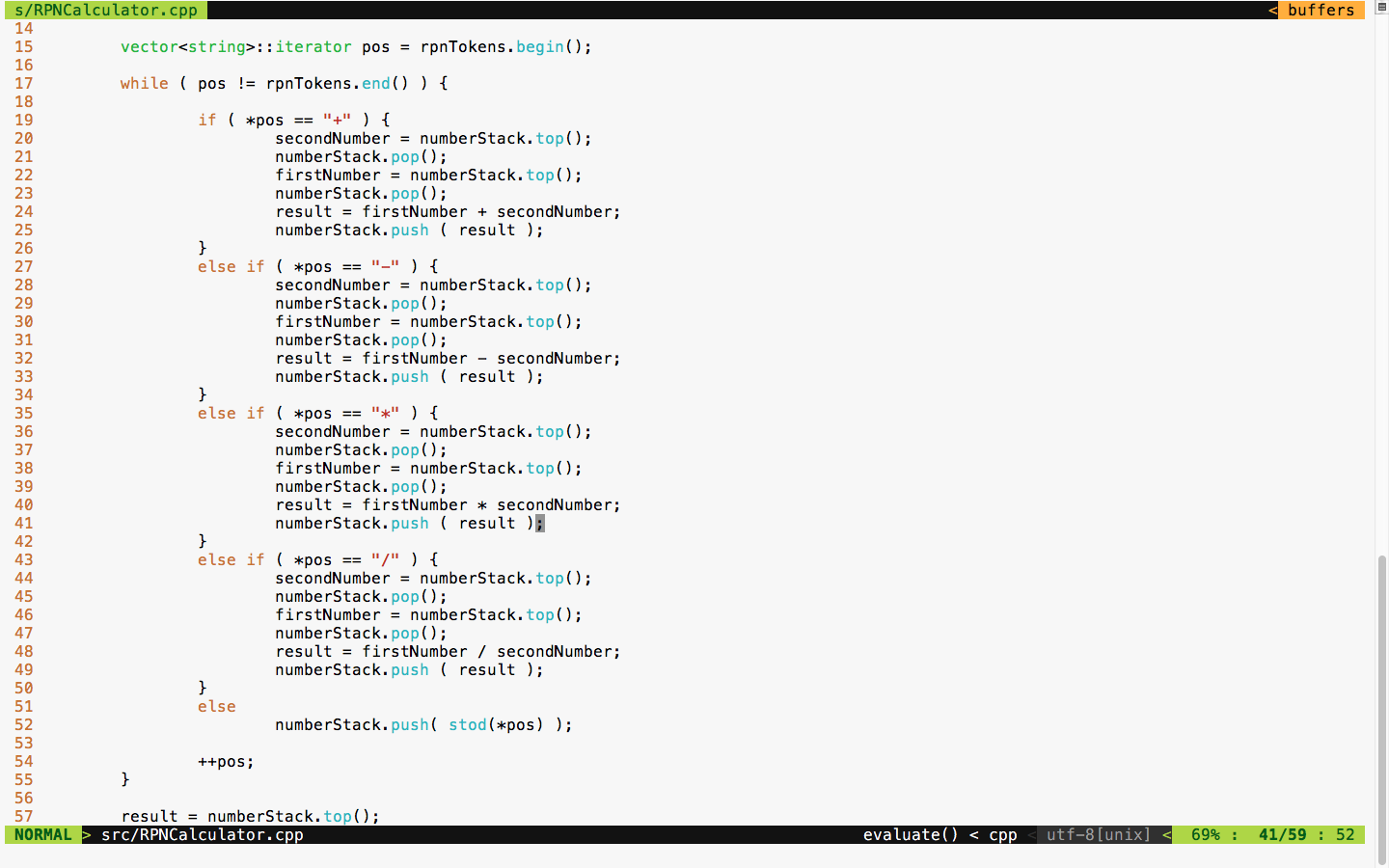

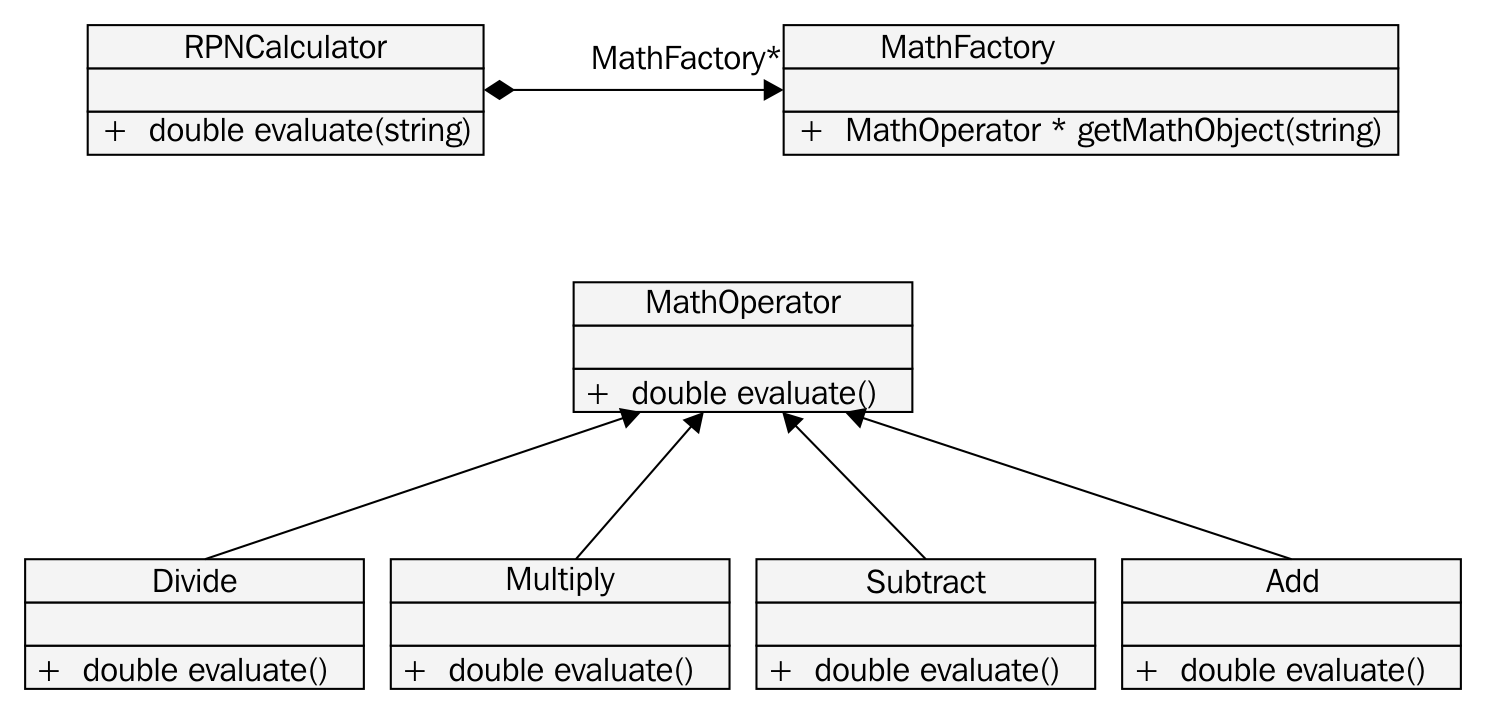

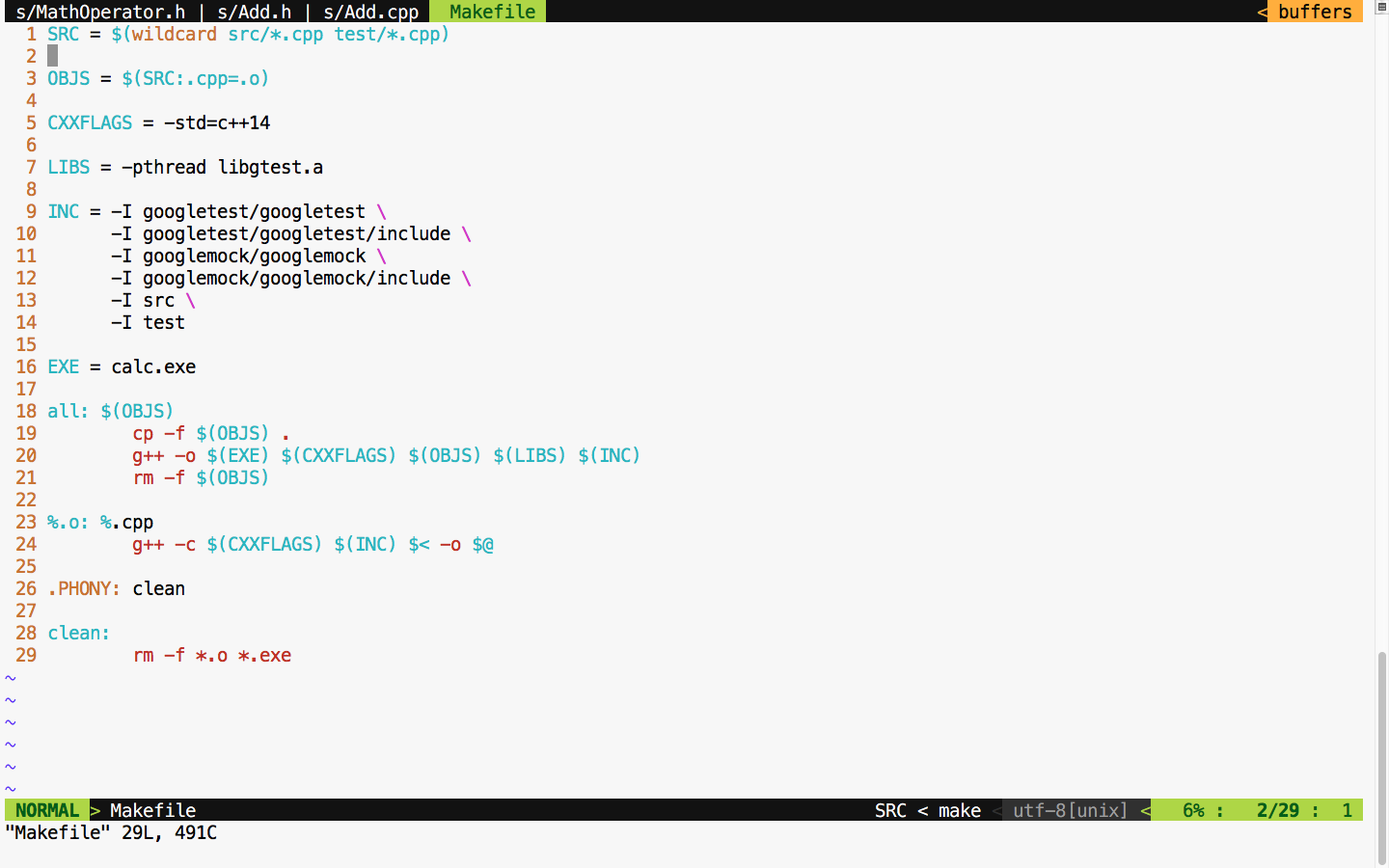

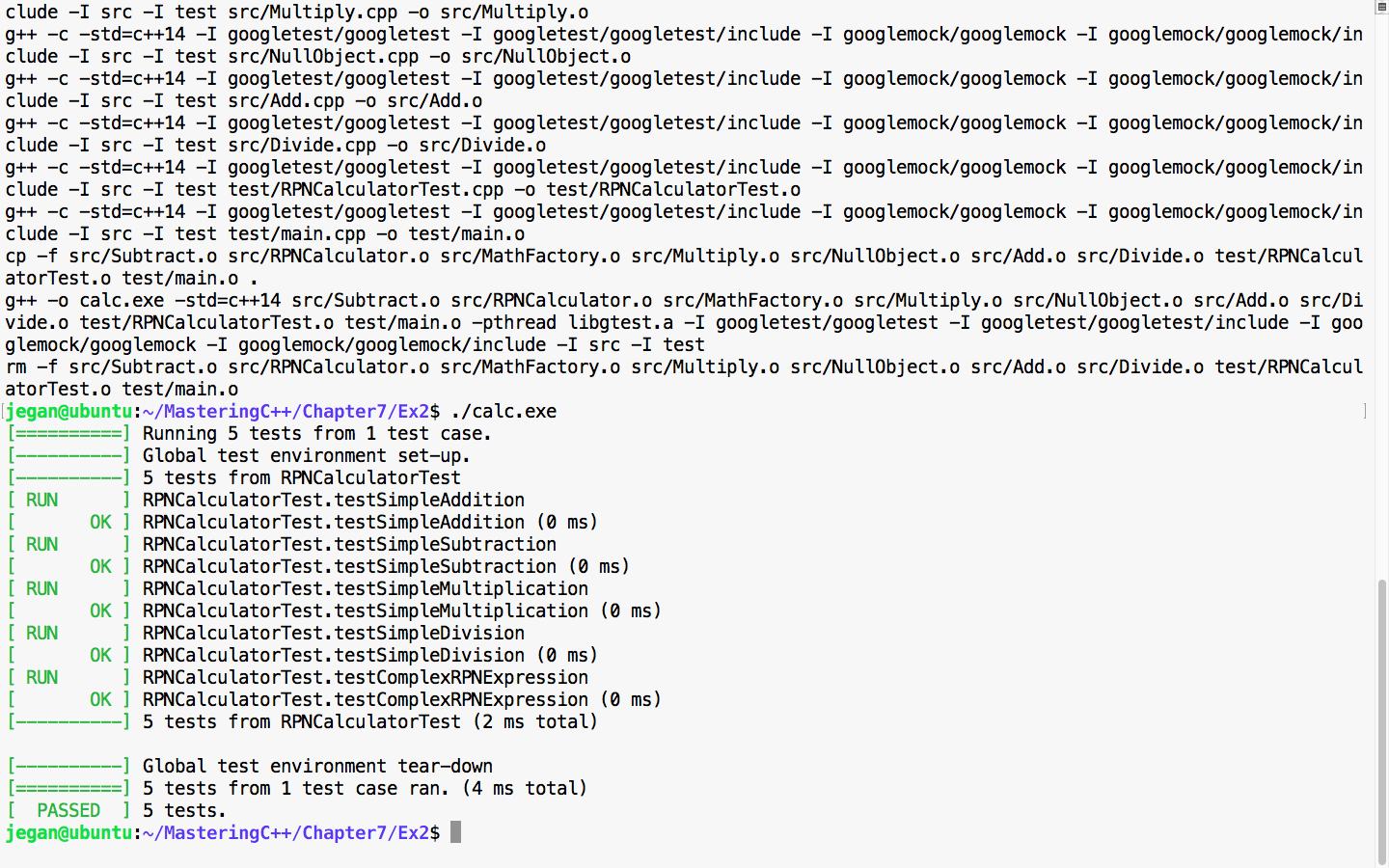

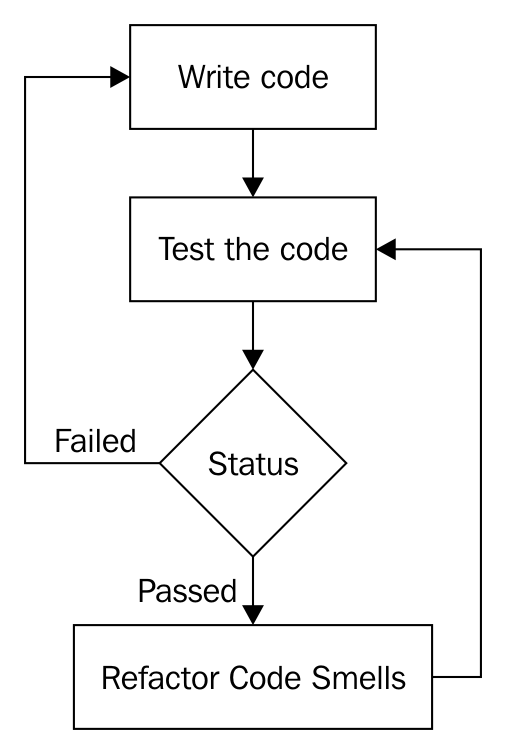

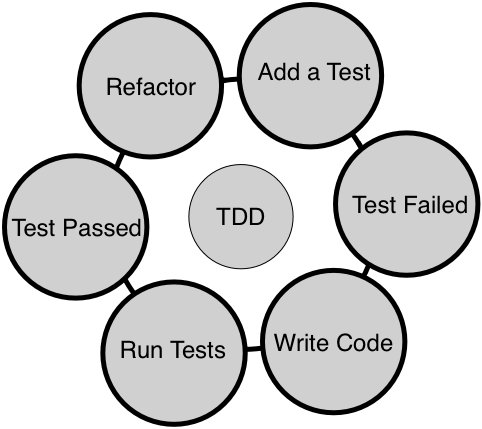

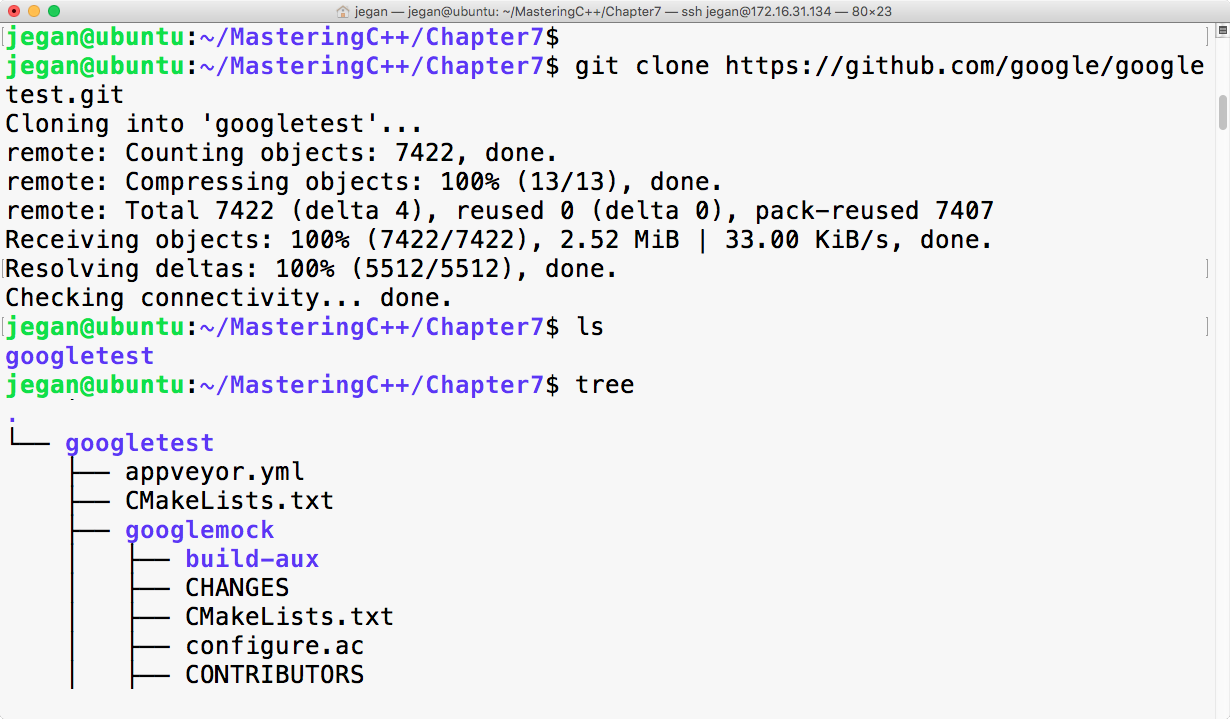

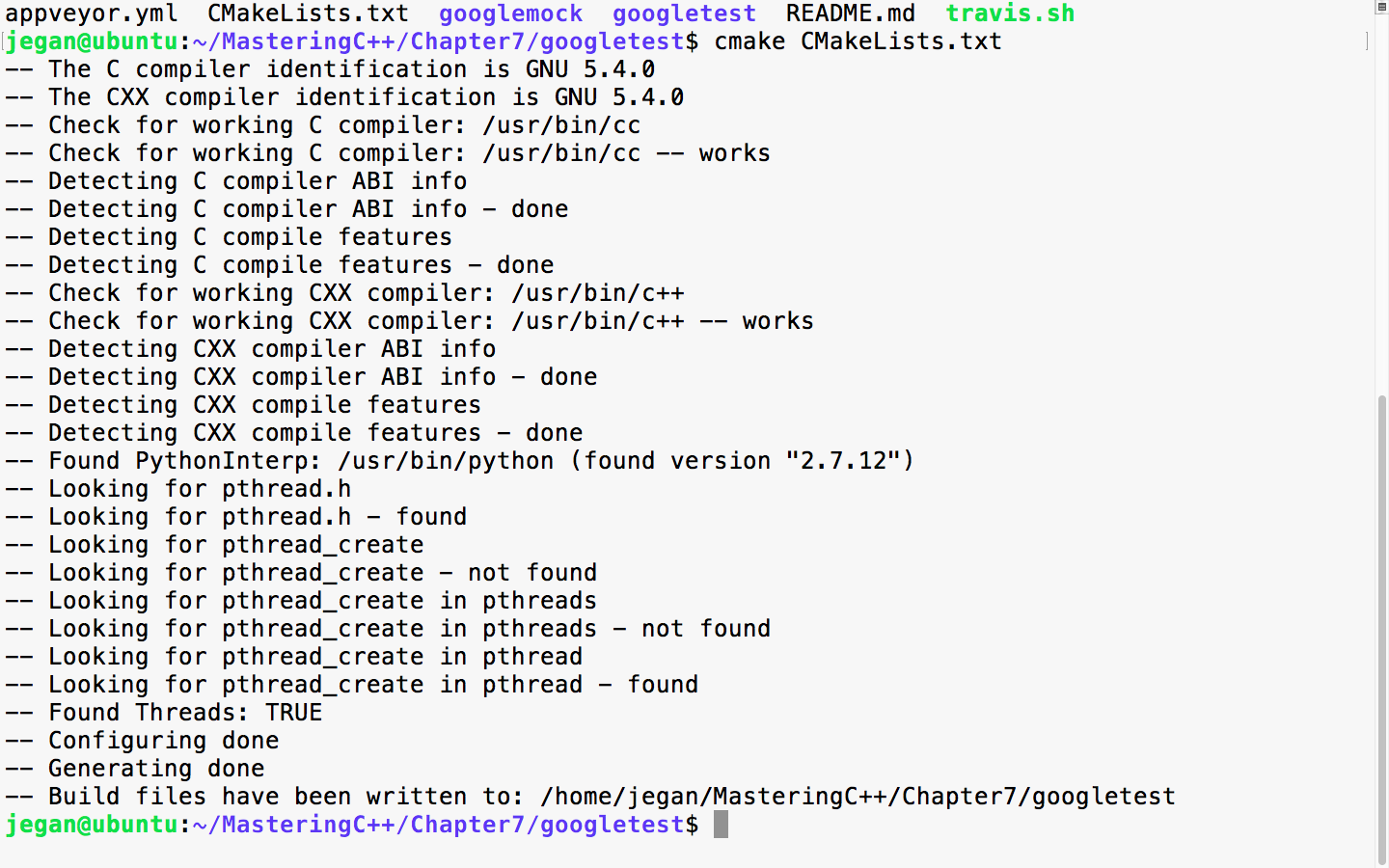

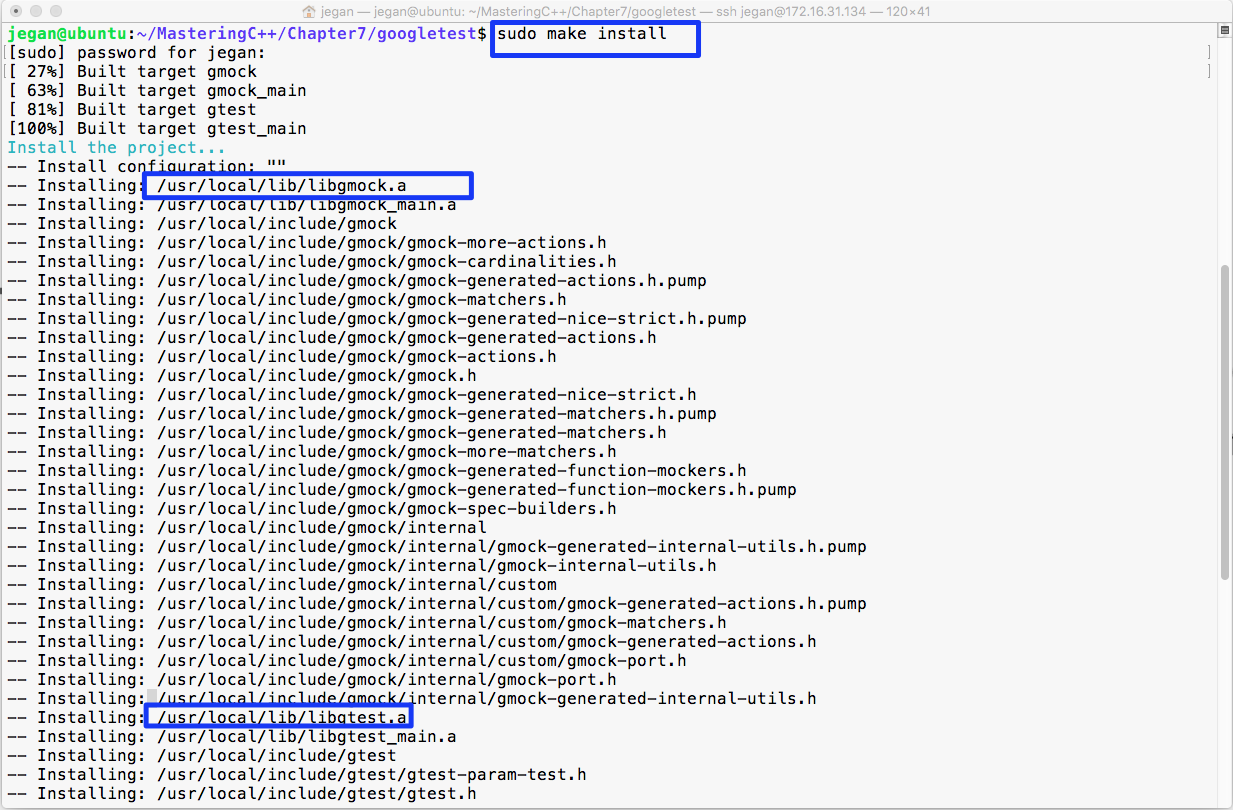

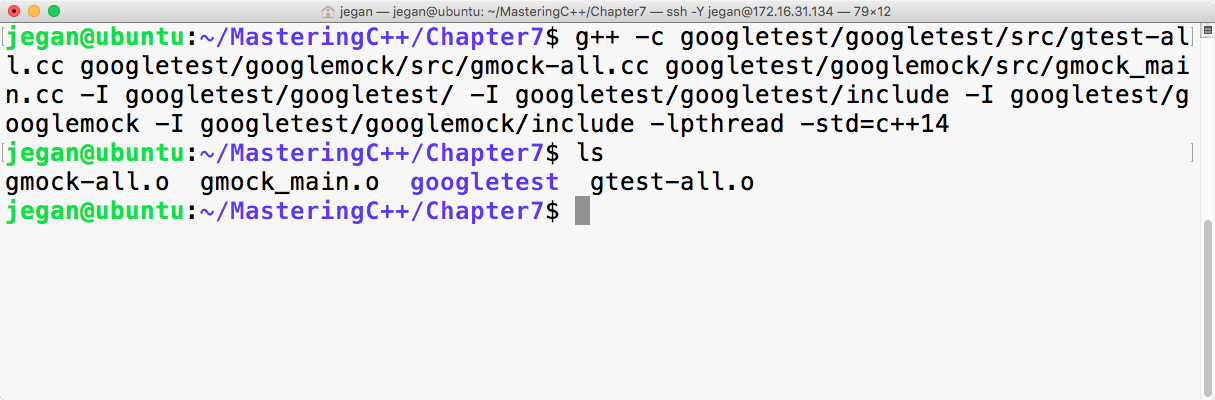

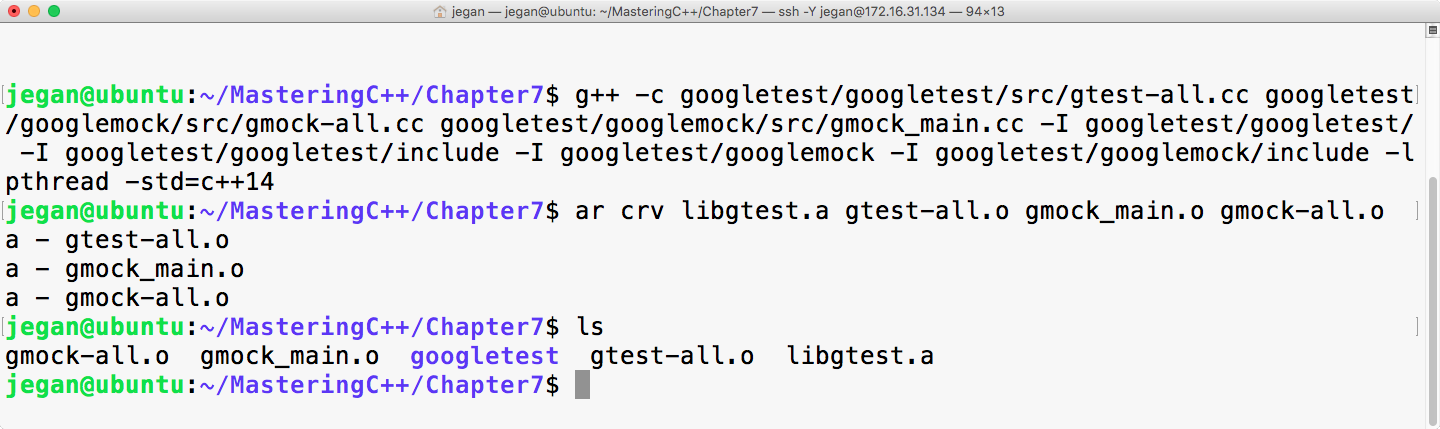

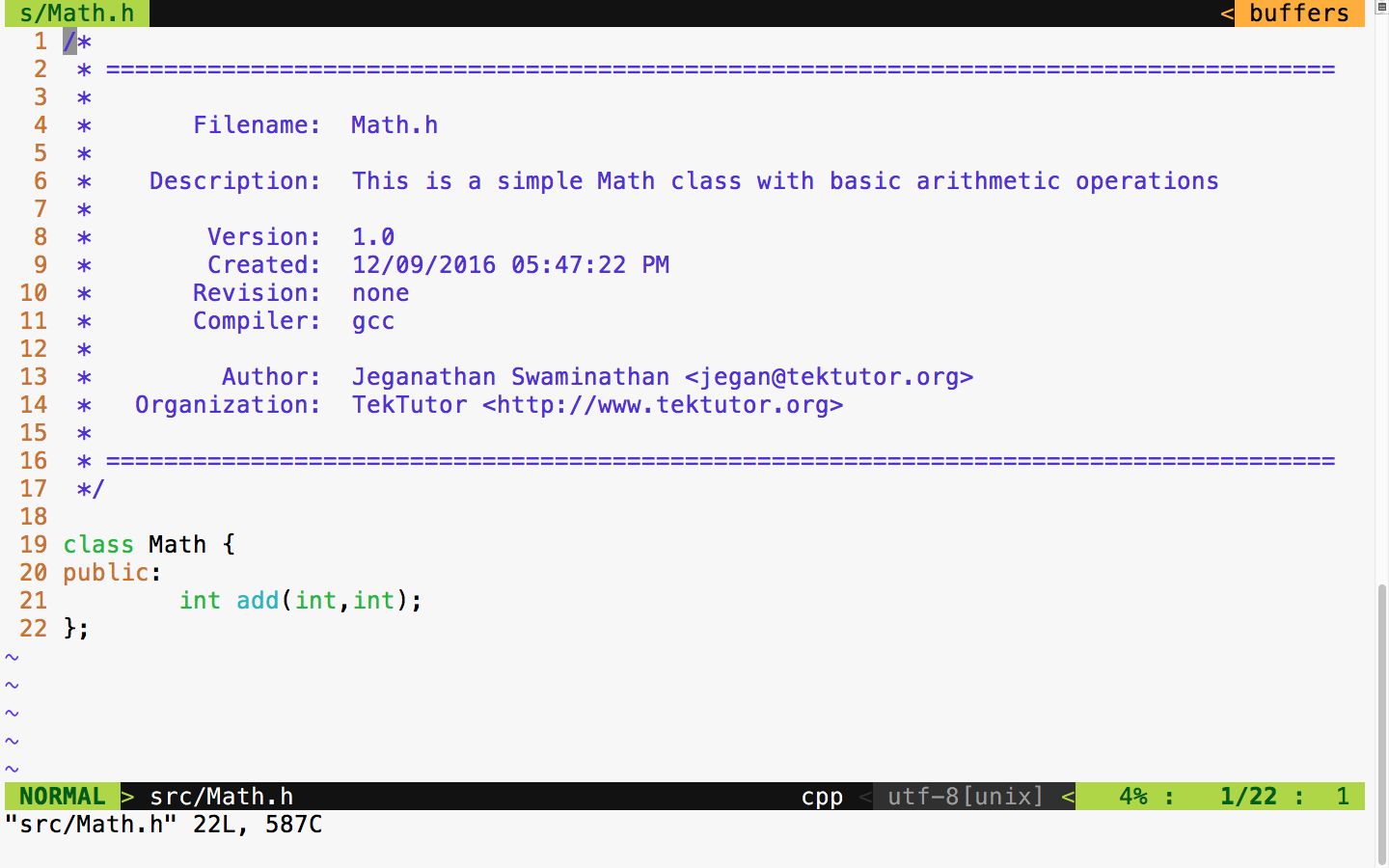

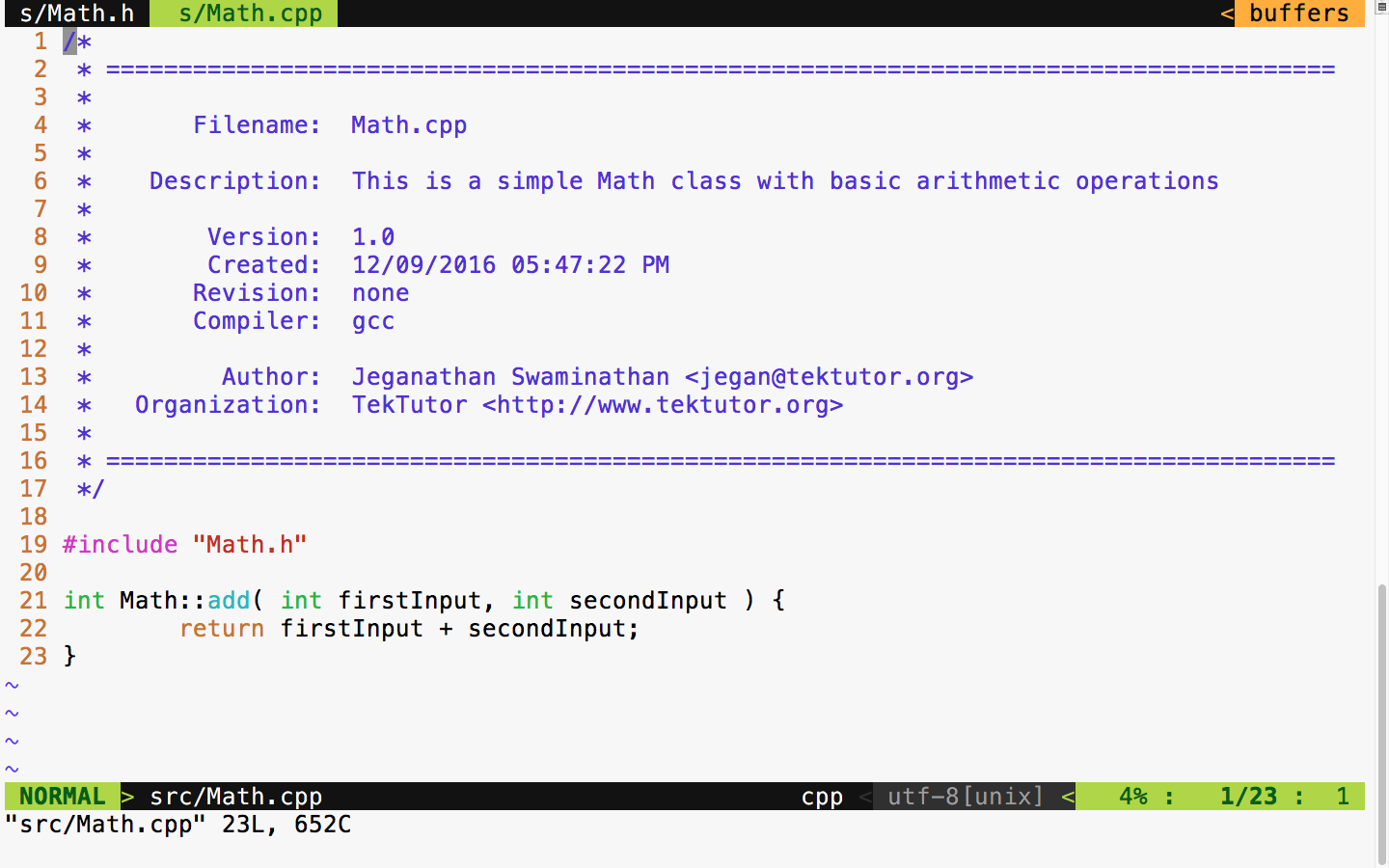

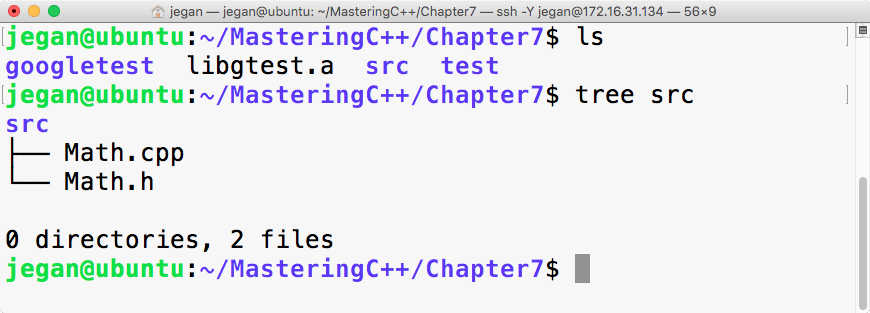

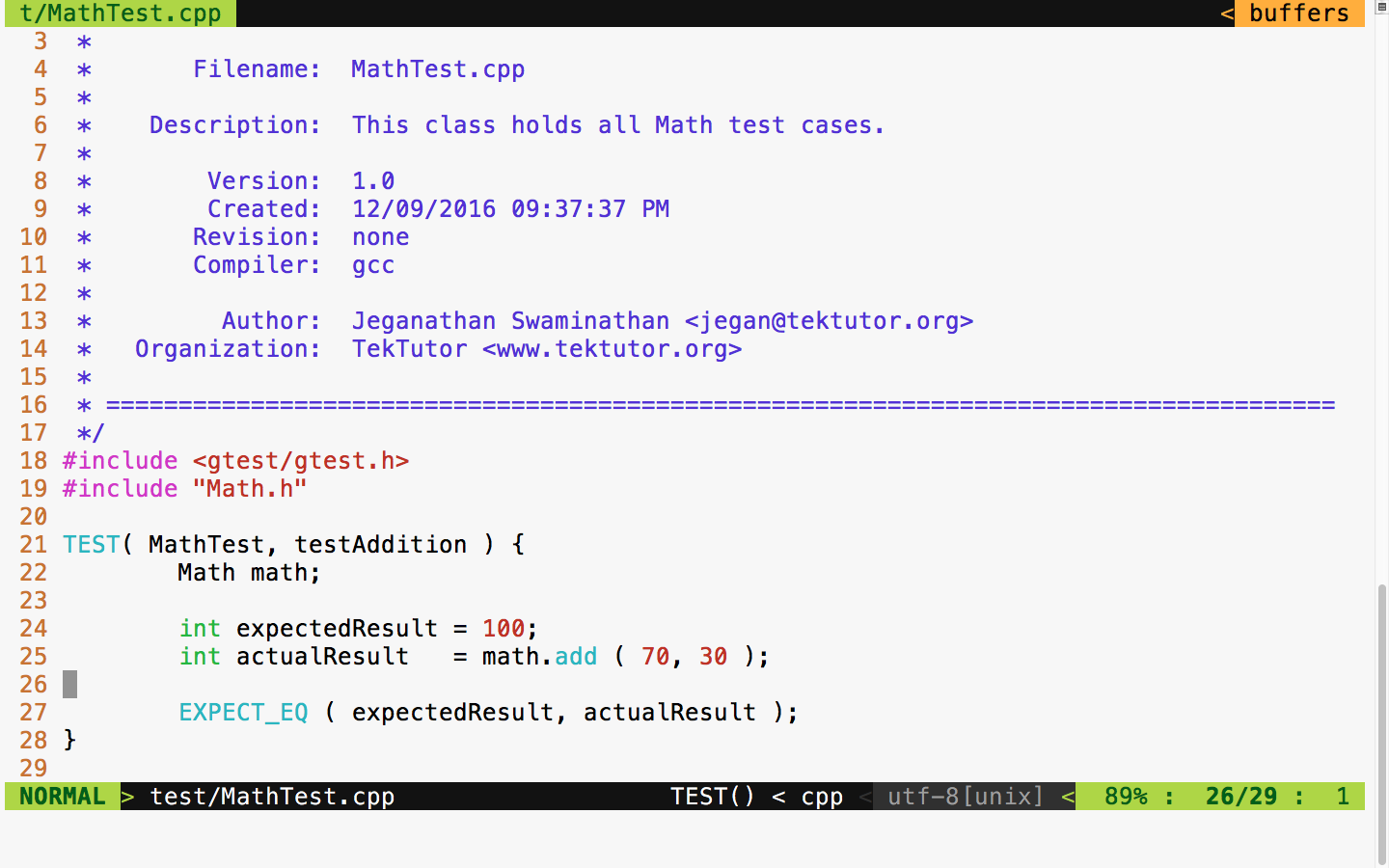

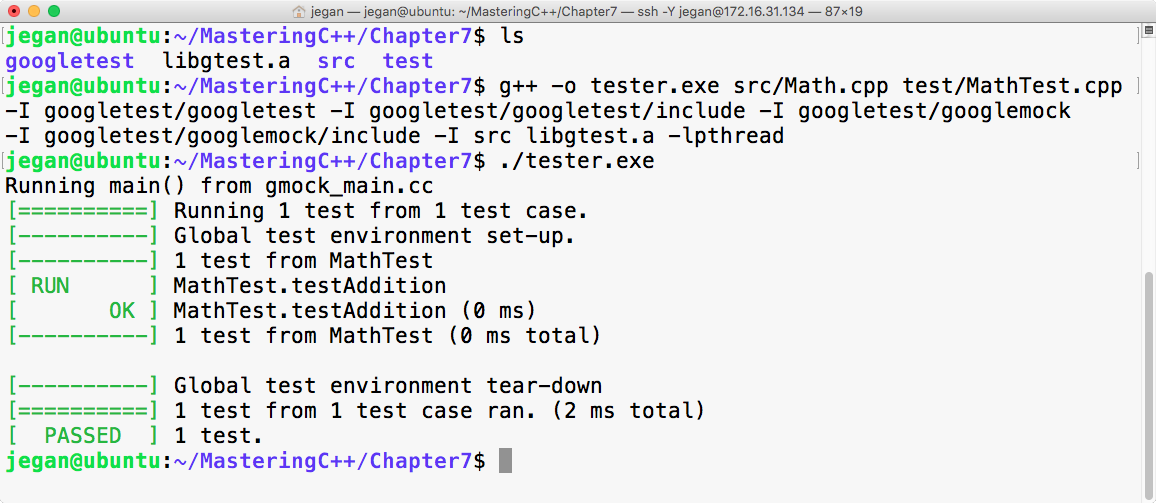

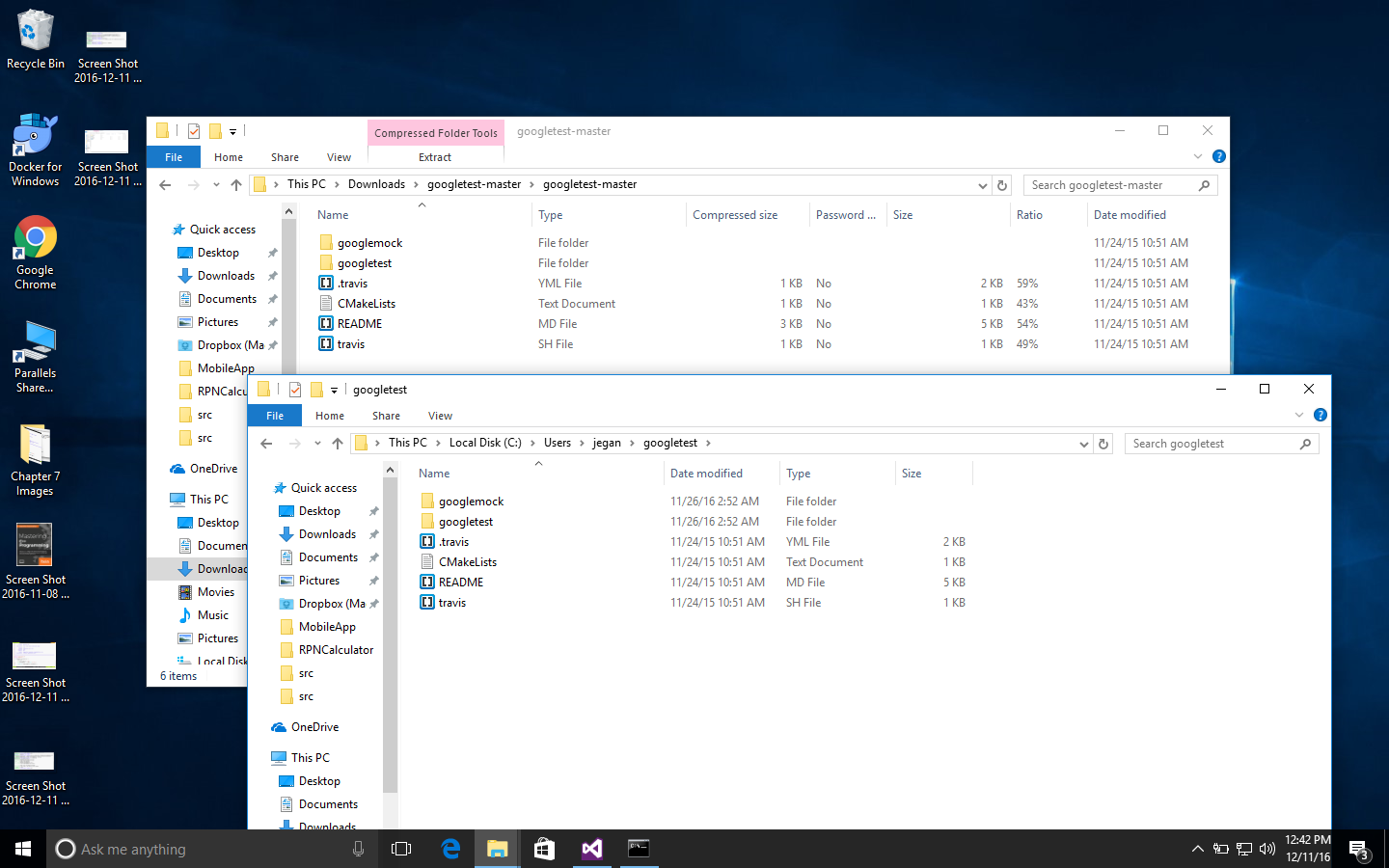

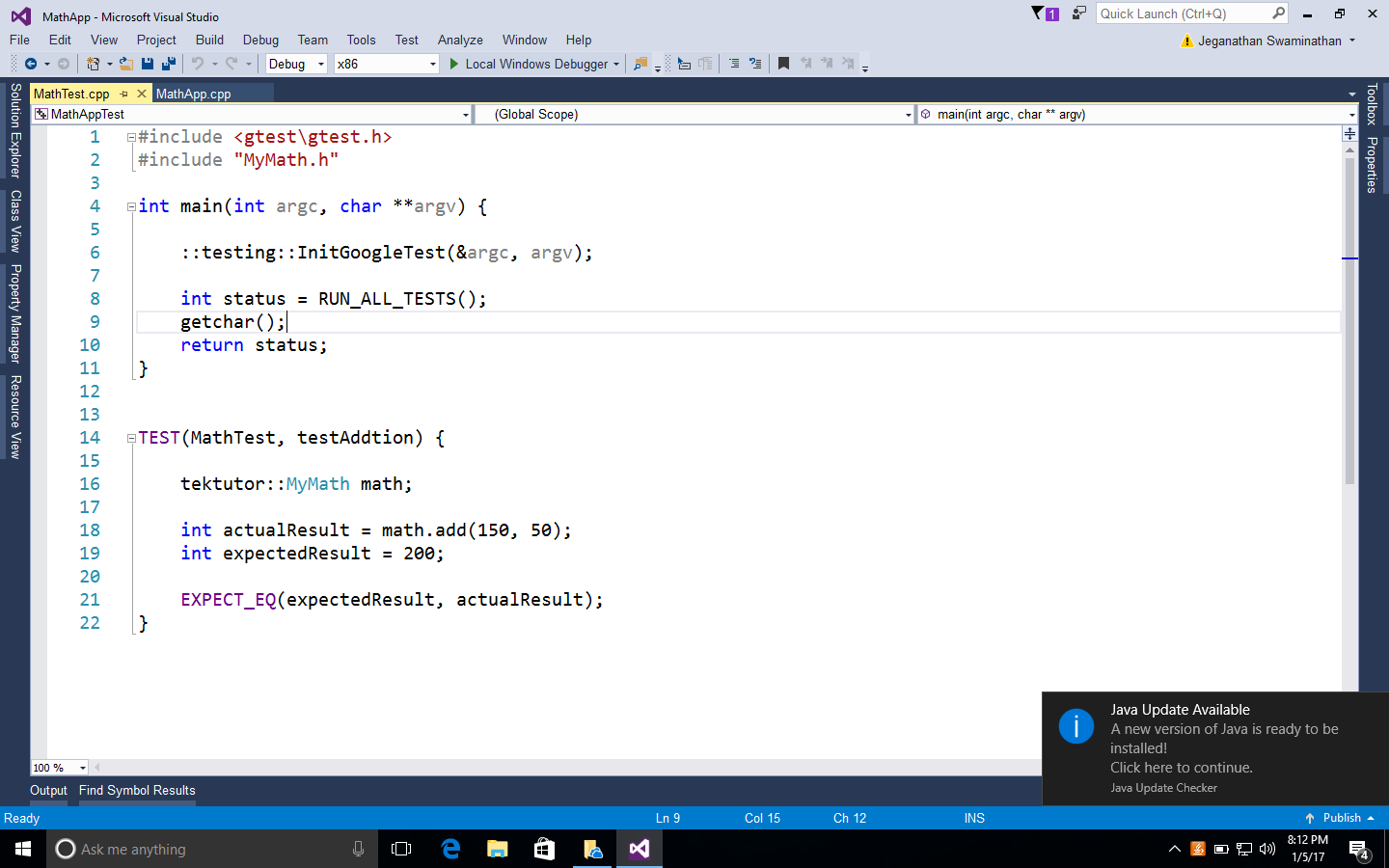

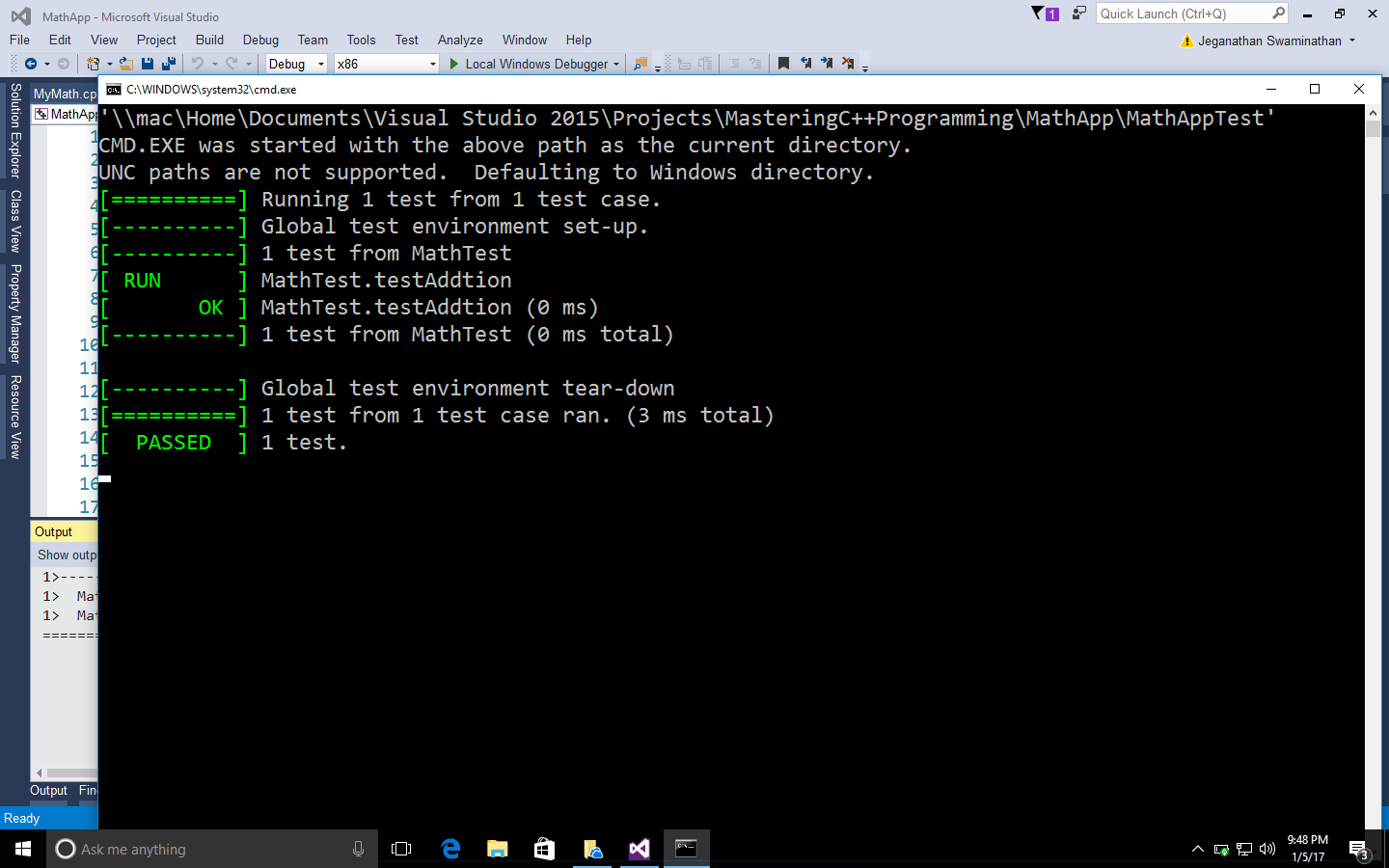

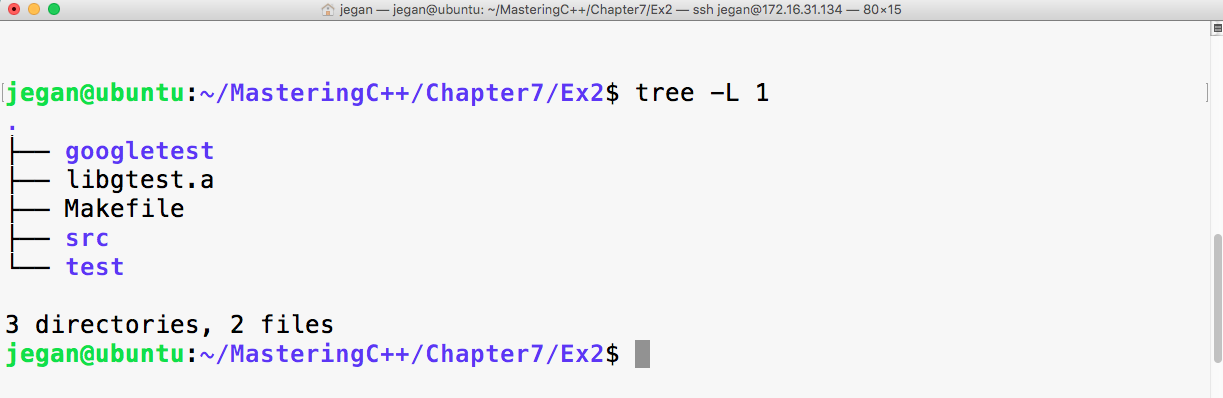

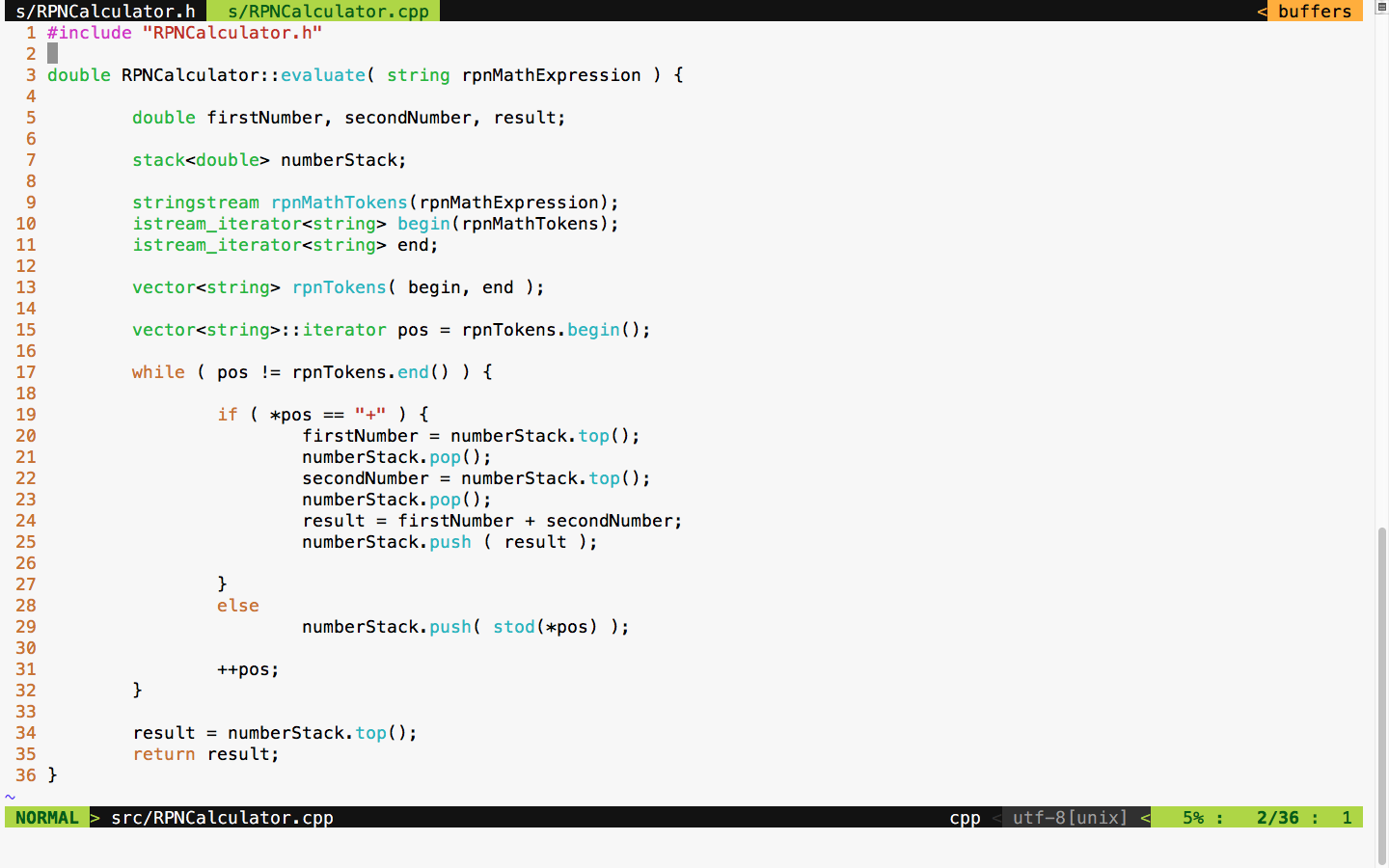

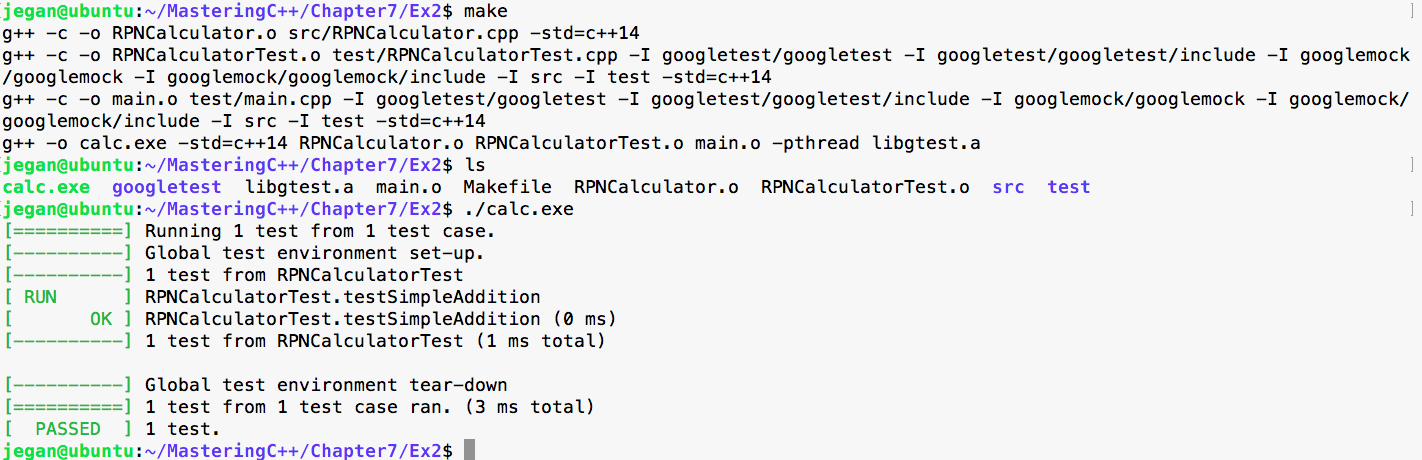

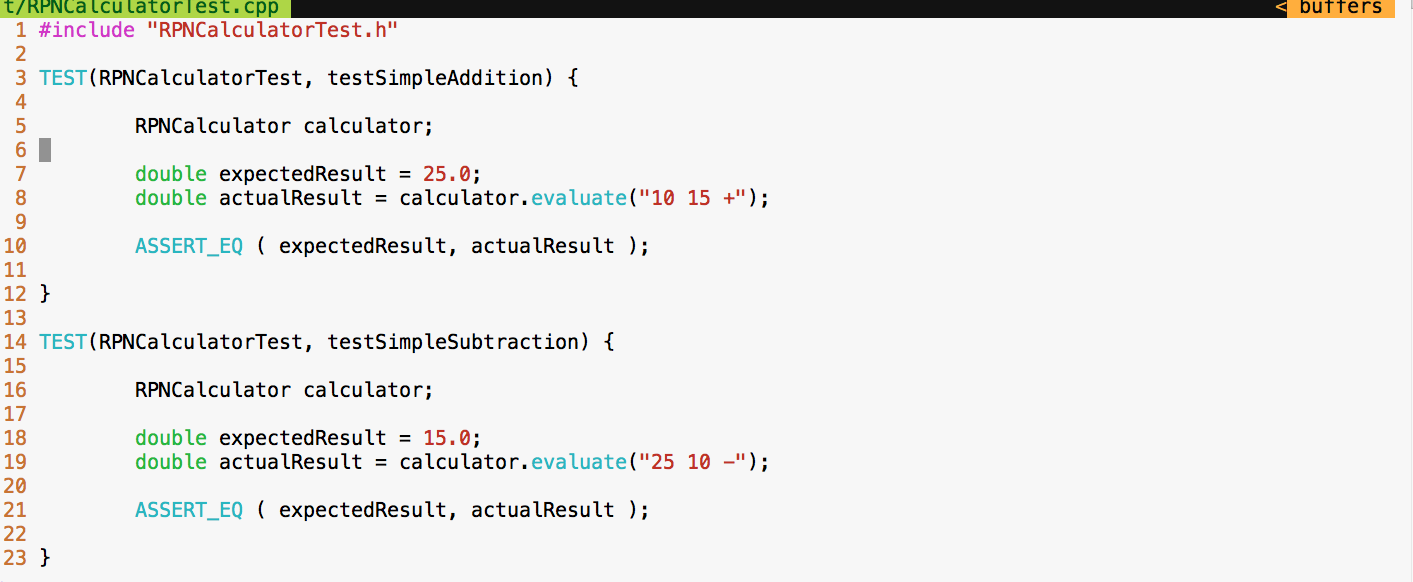

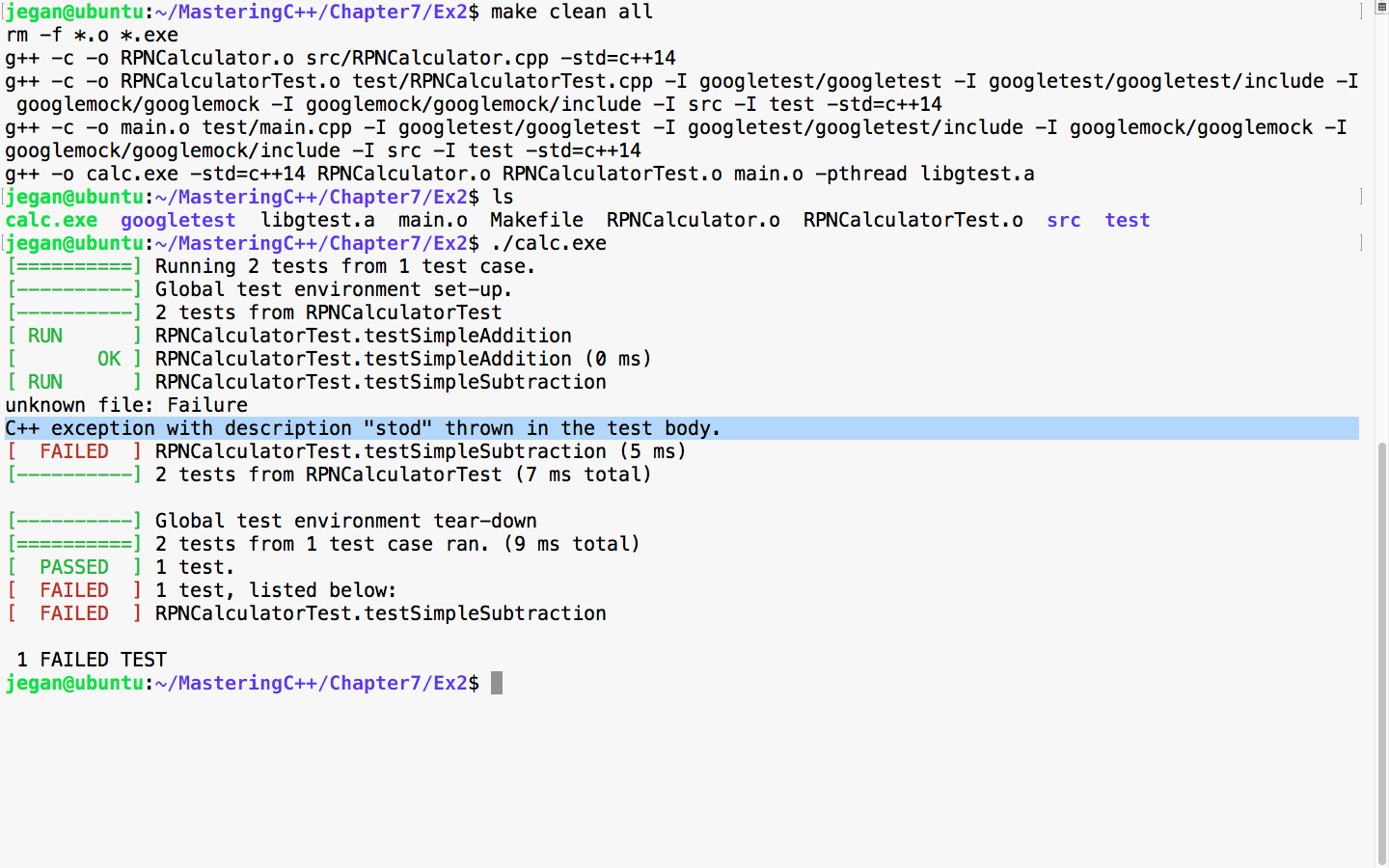

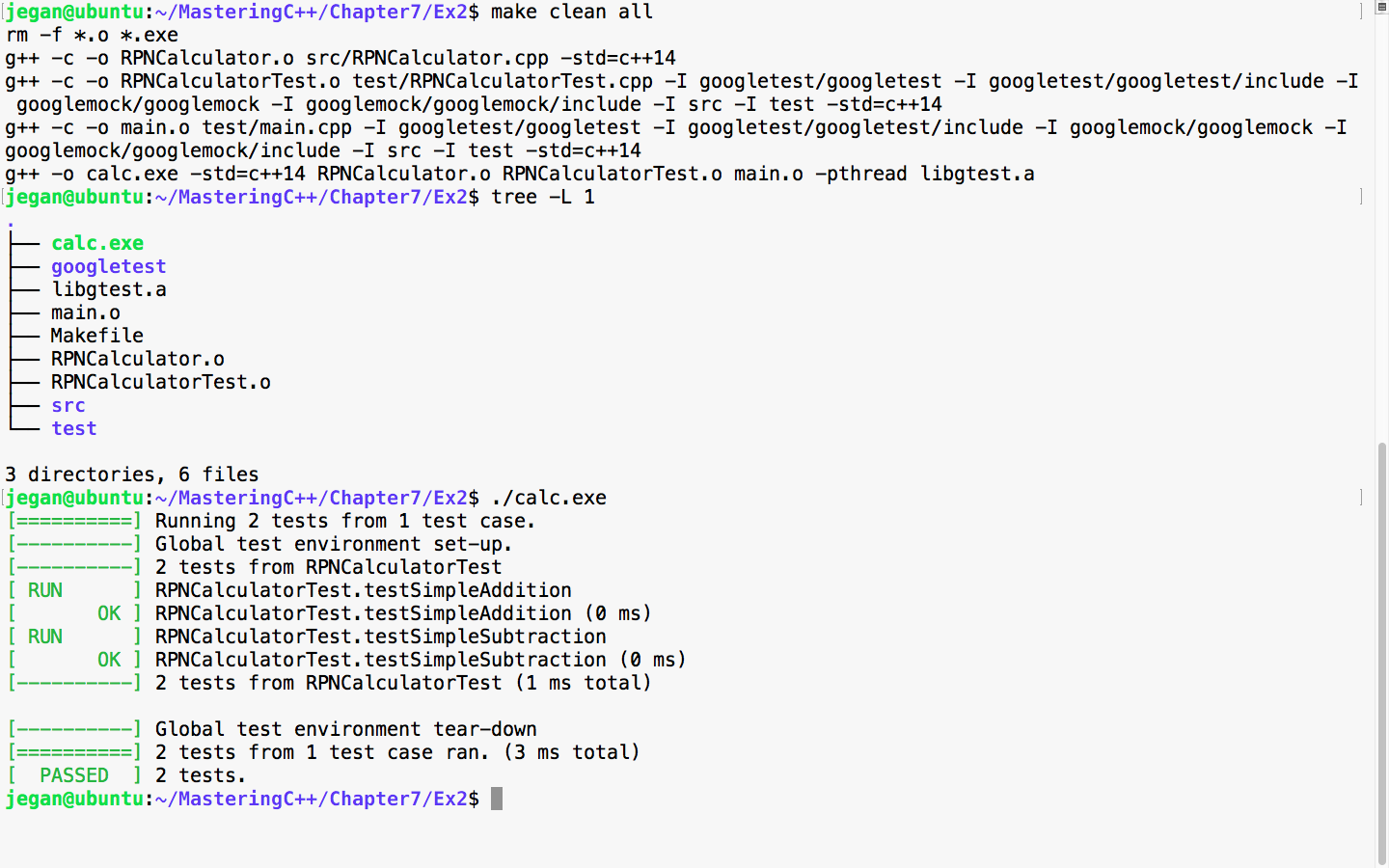

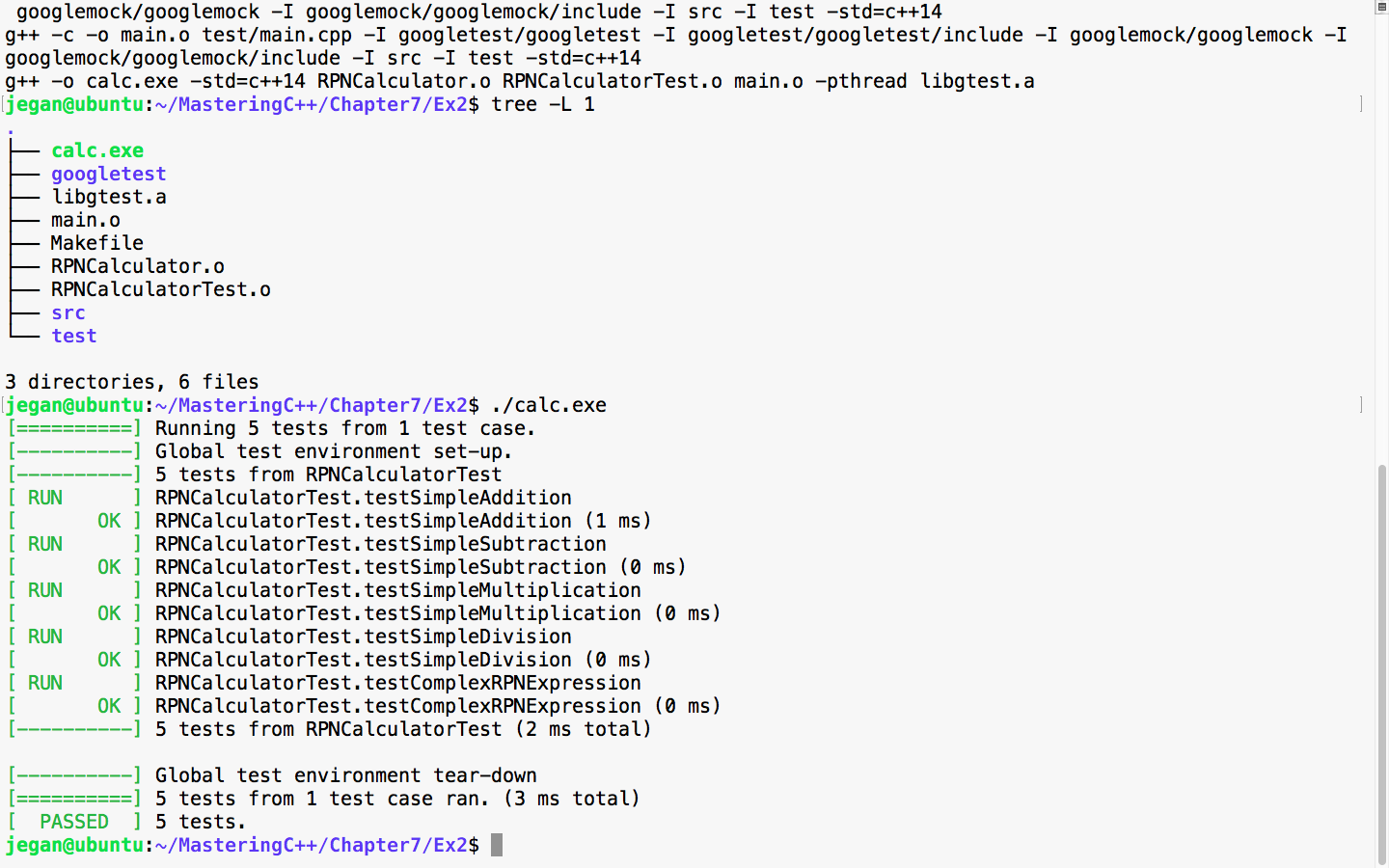

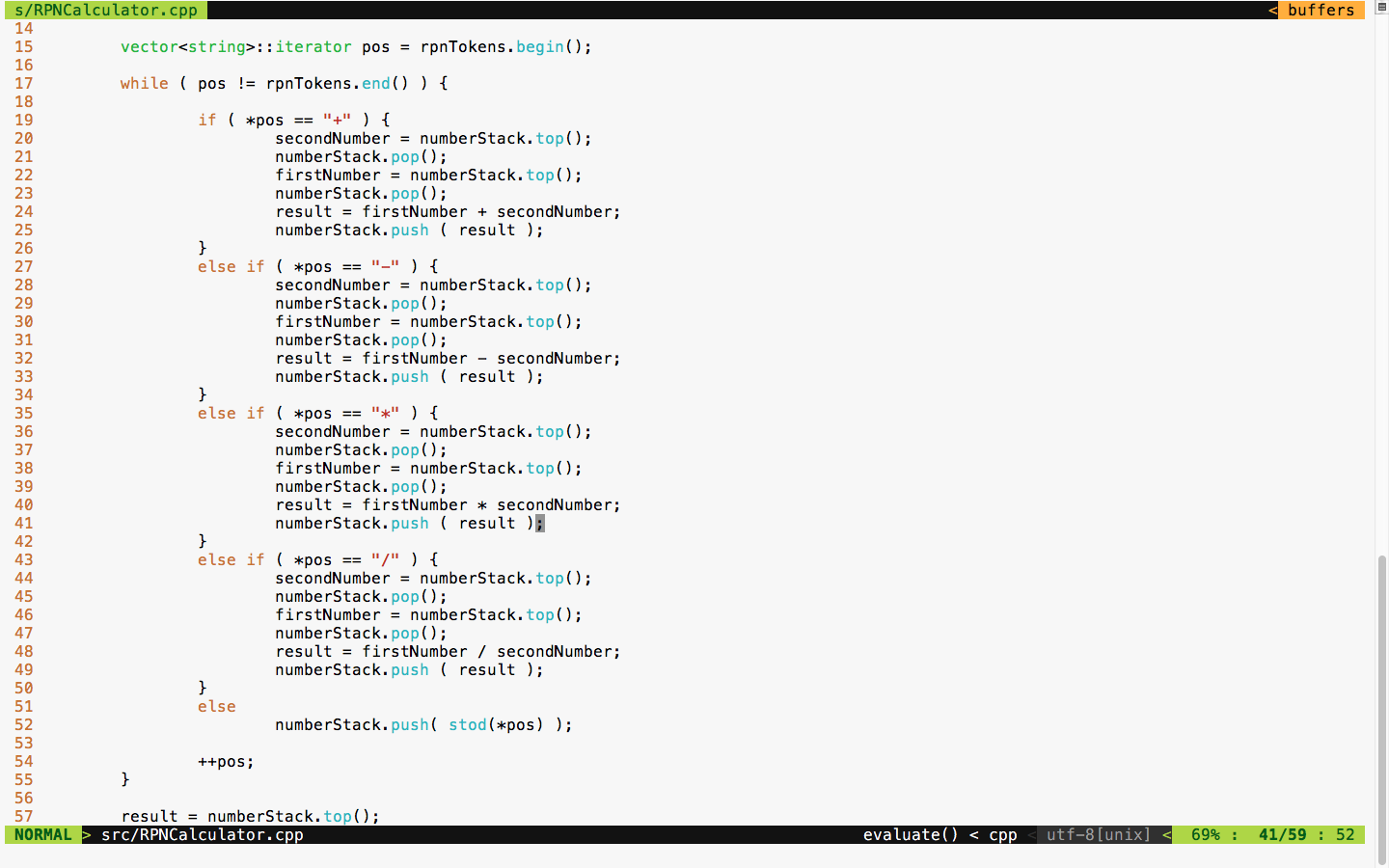

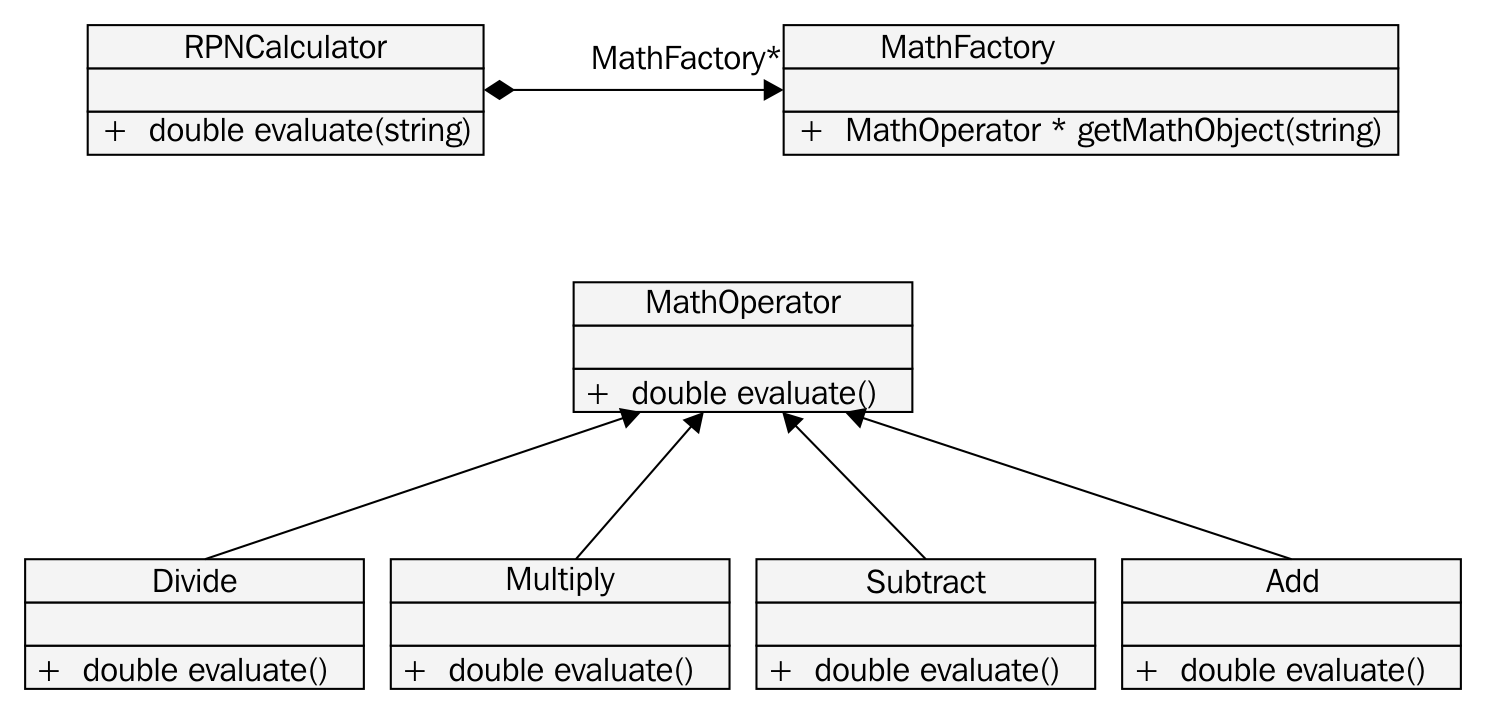

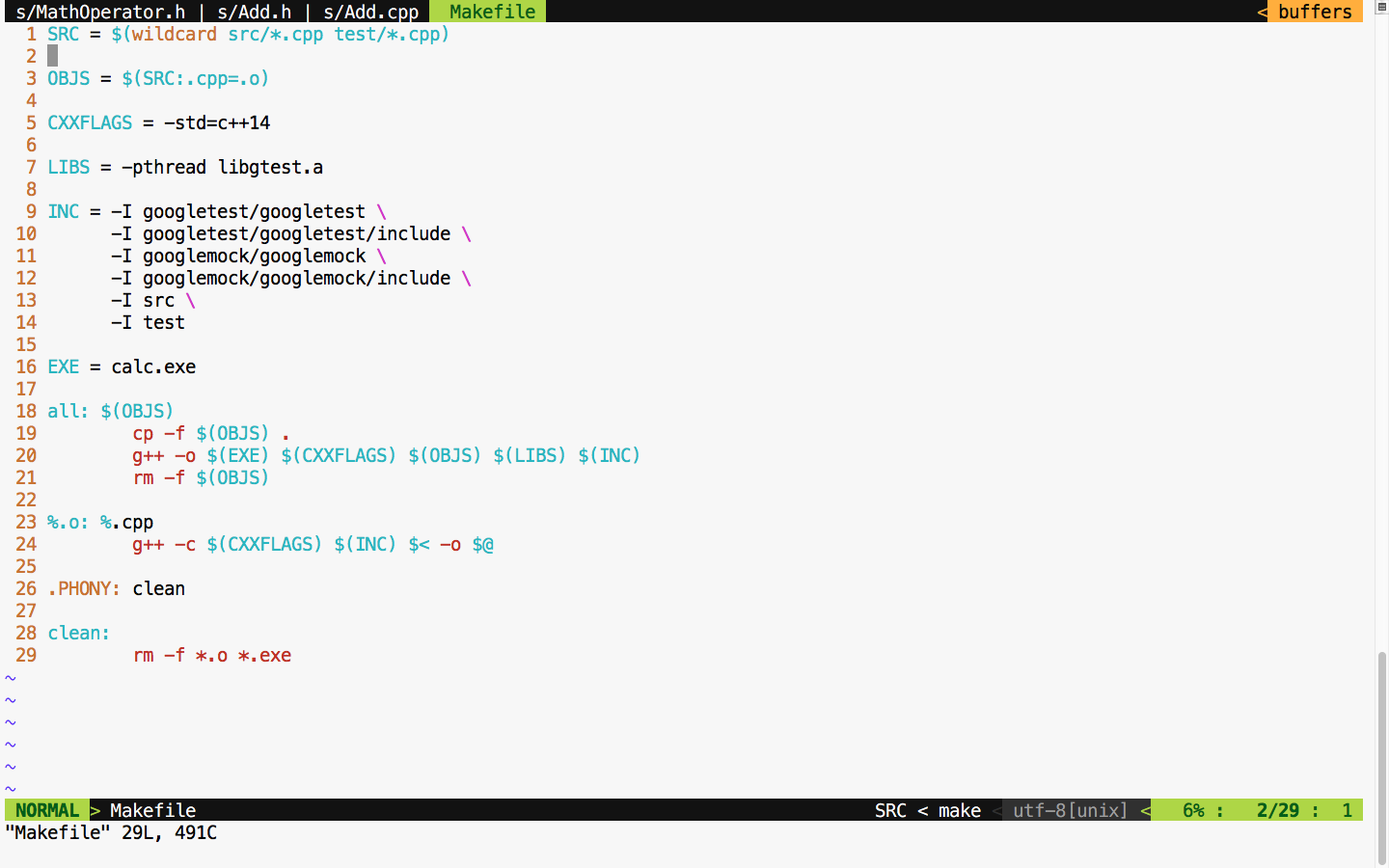

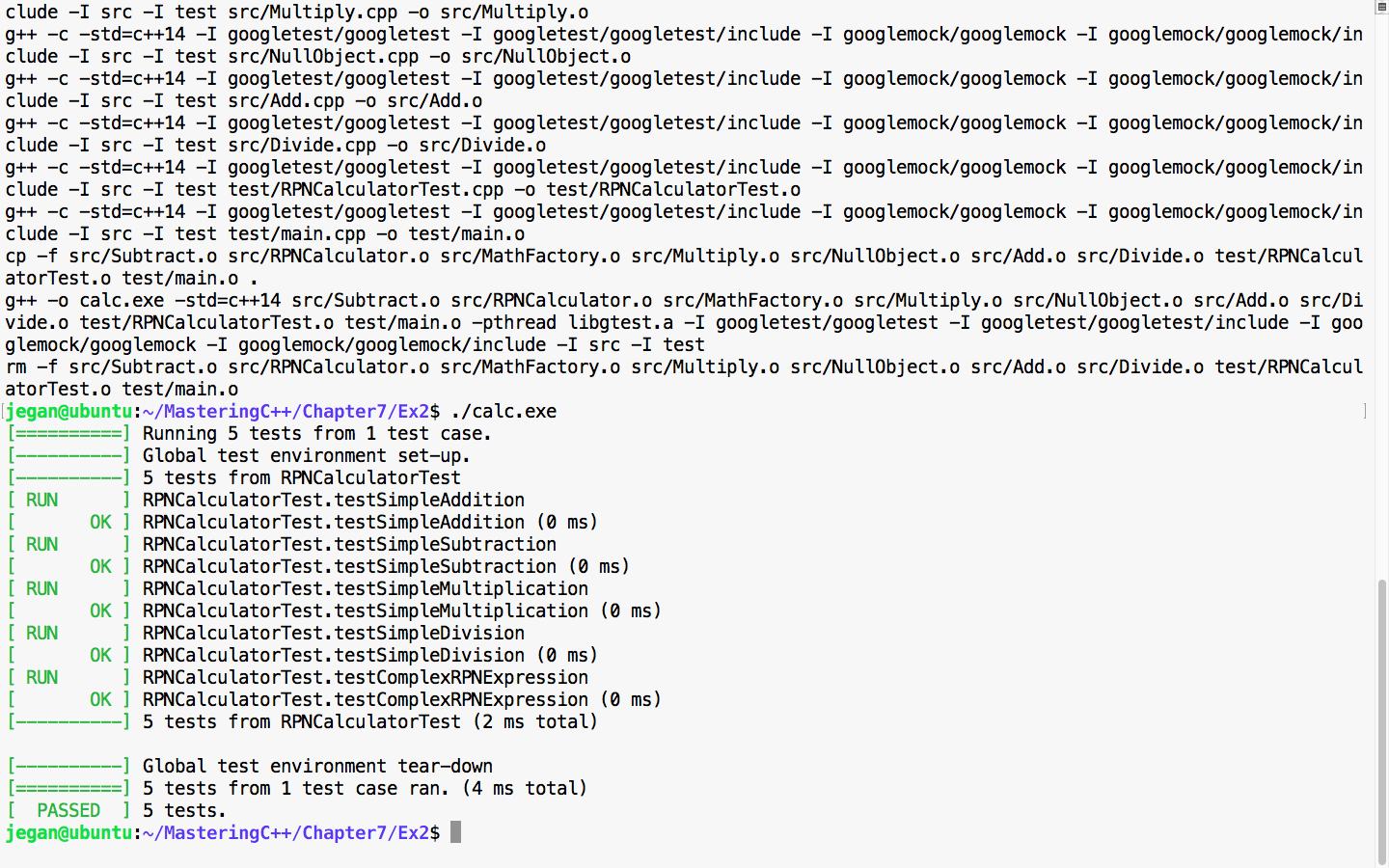

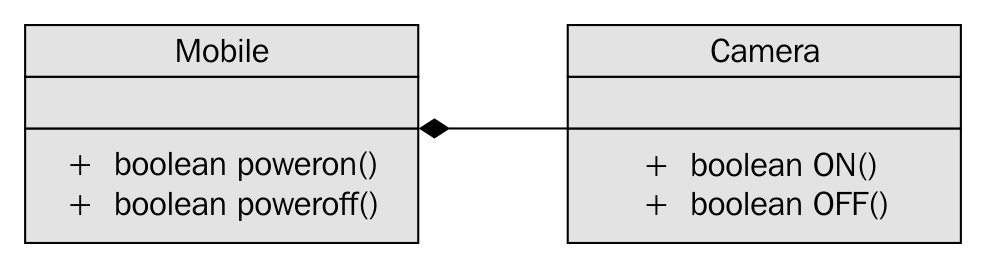

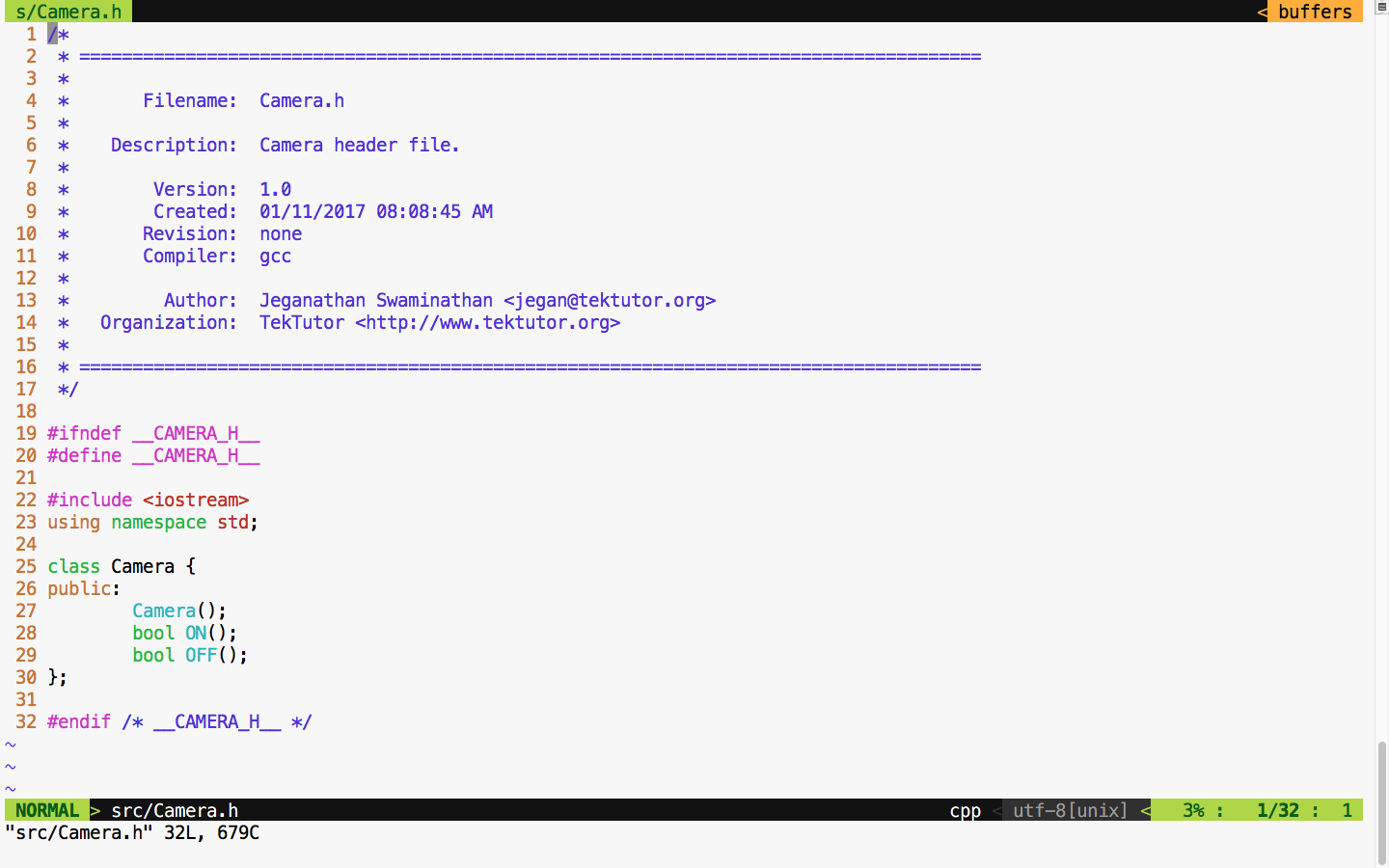

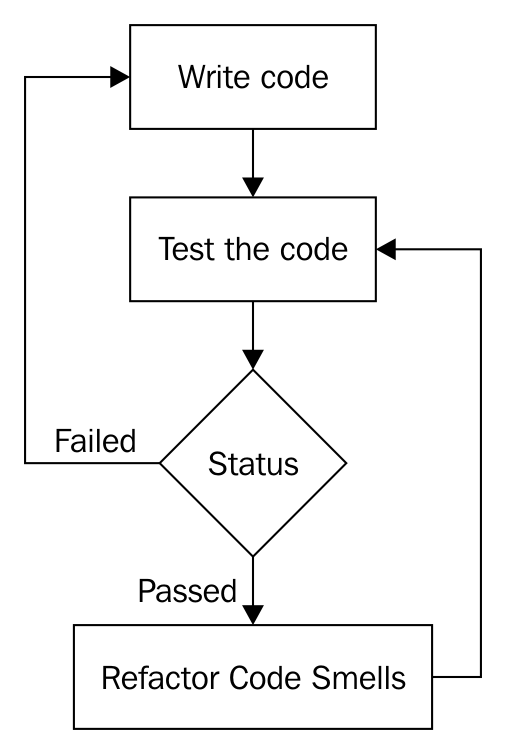

Chapter 7, Test-Driven Development, gives a brief overview of TDD and clarifies FAQs on TDD. This chapter provides you with step-by-step instructions to install Google test framework and integrate it with the Linux and Windows platforms. It helps you develop applications using TDD with an easy-to-understand tutorial style.

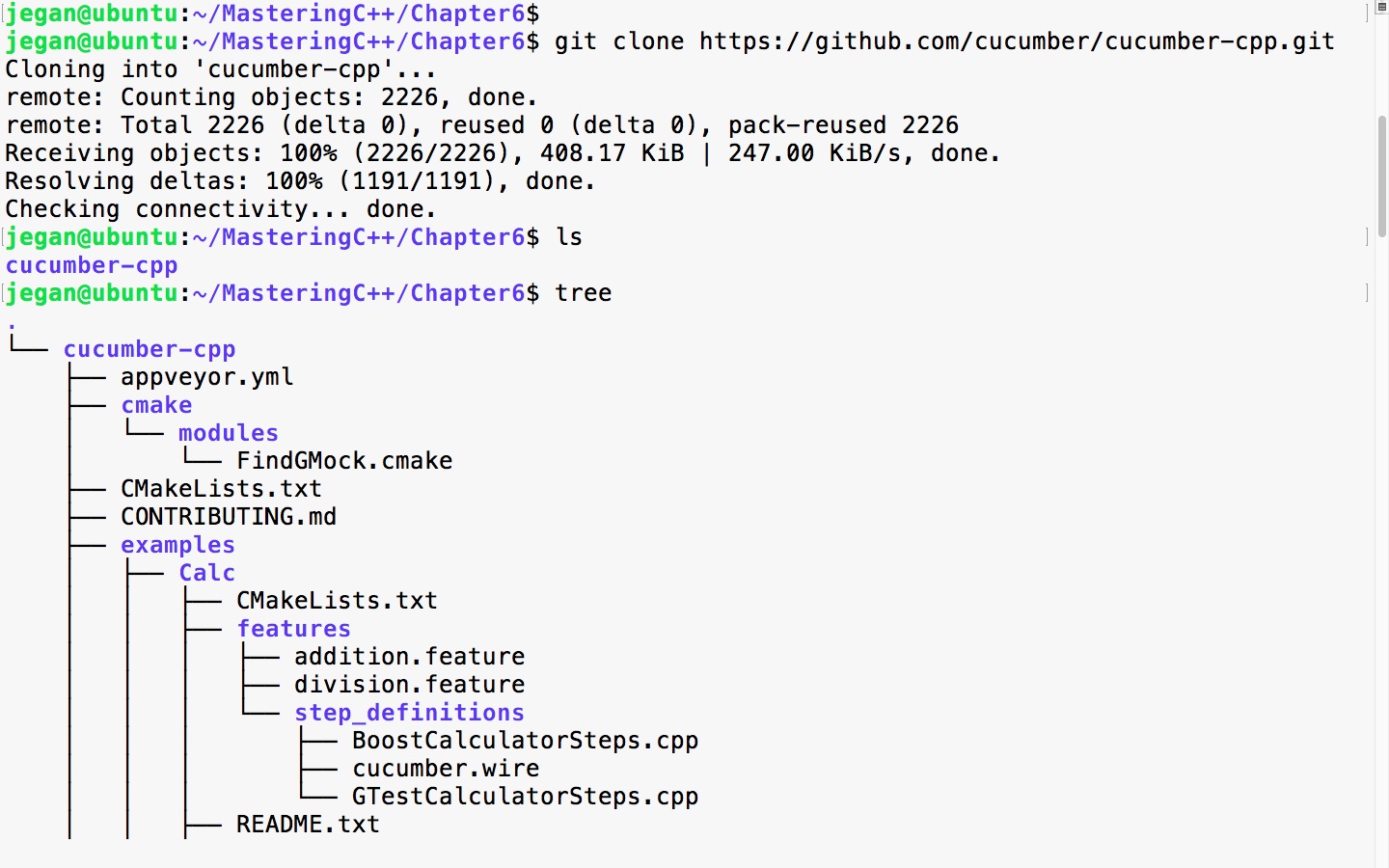

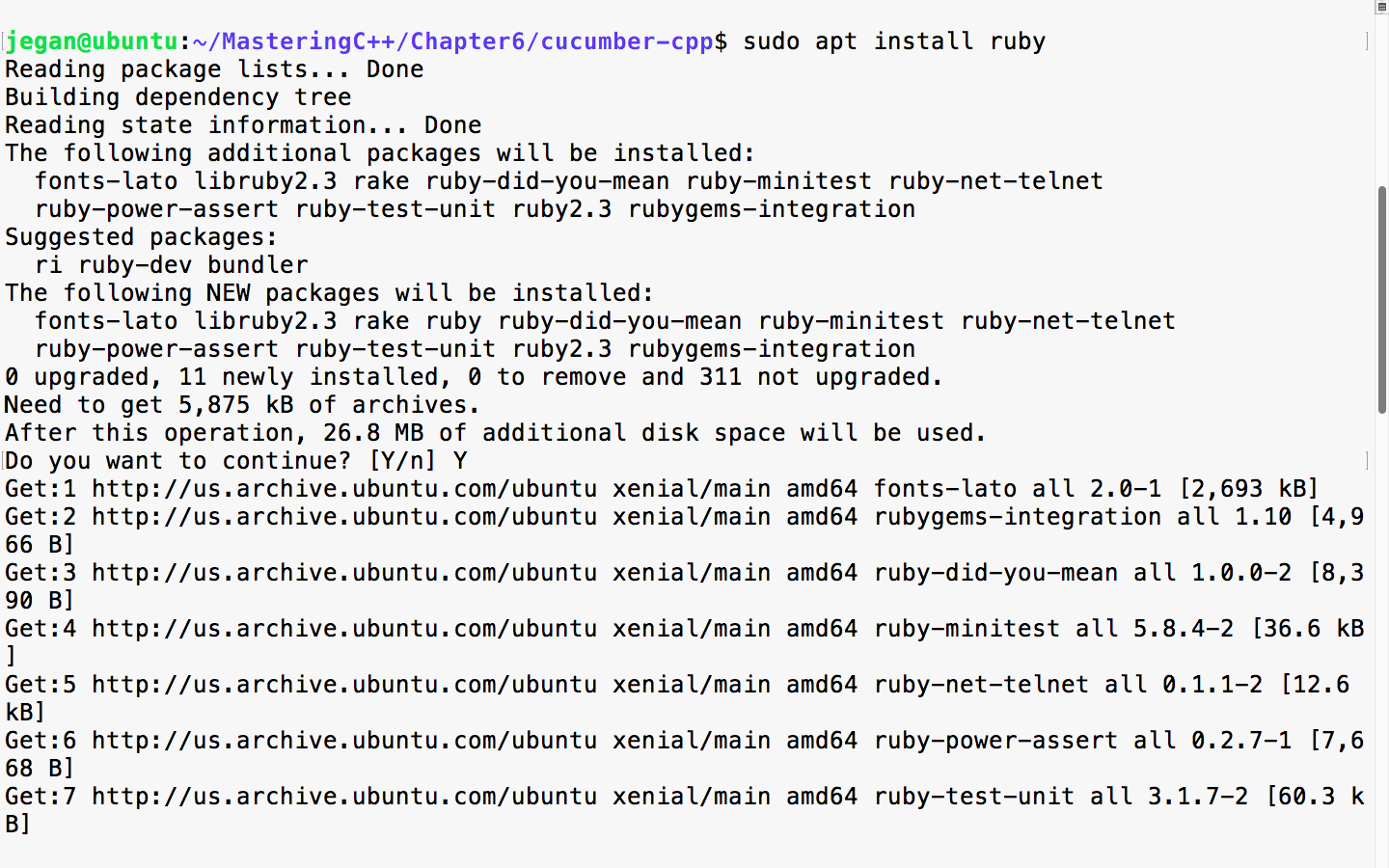

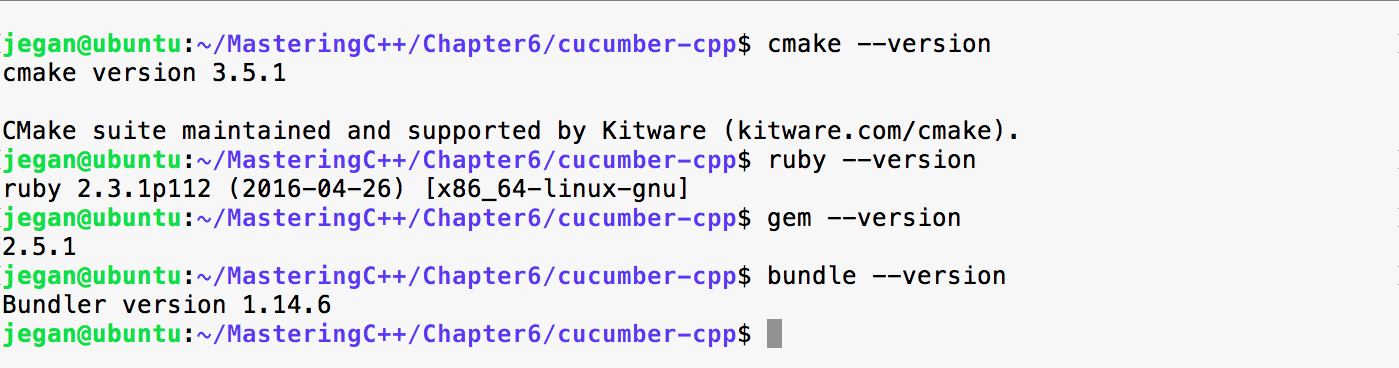

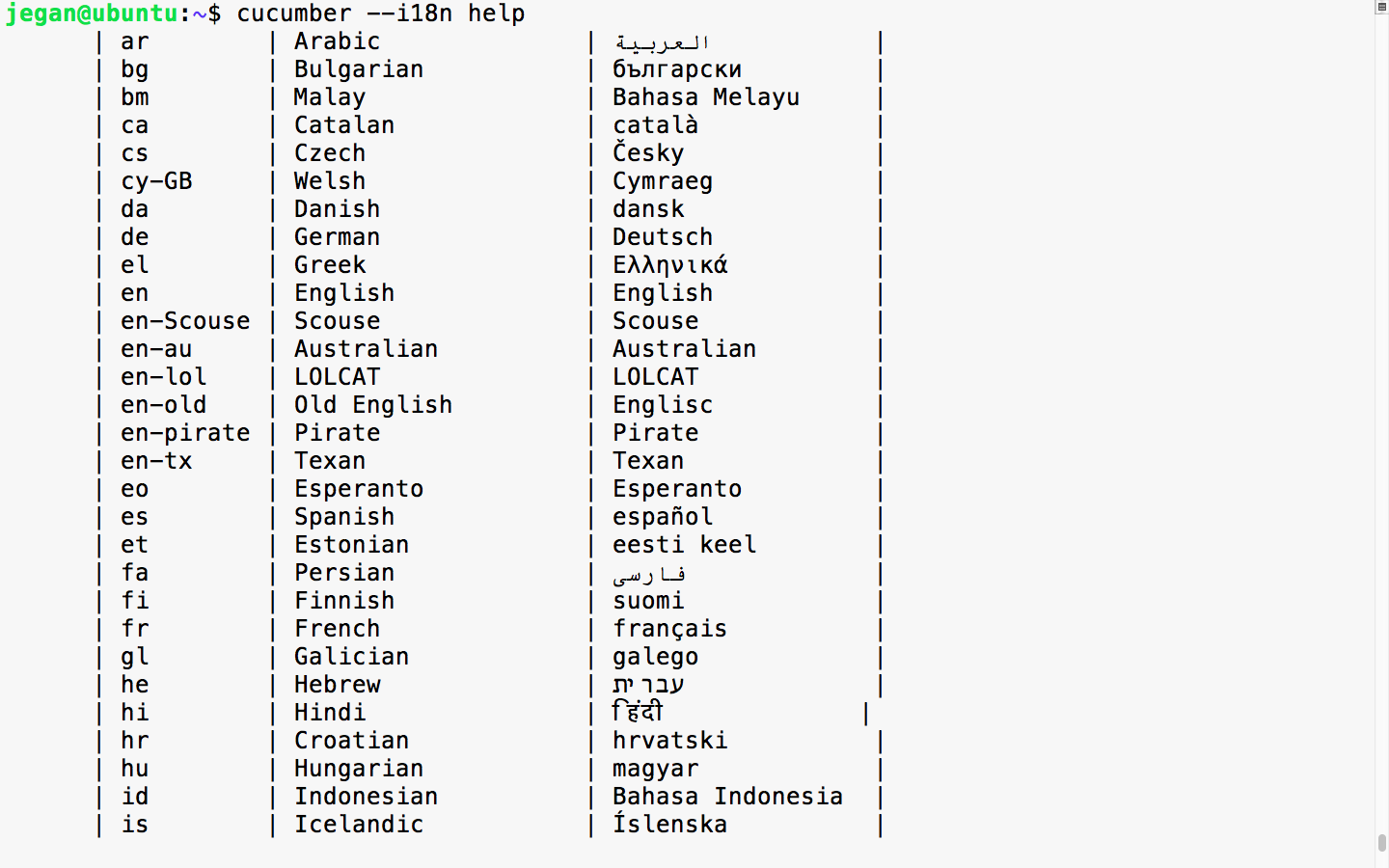

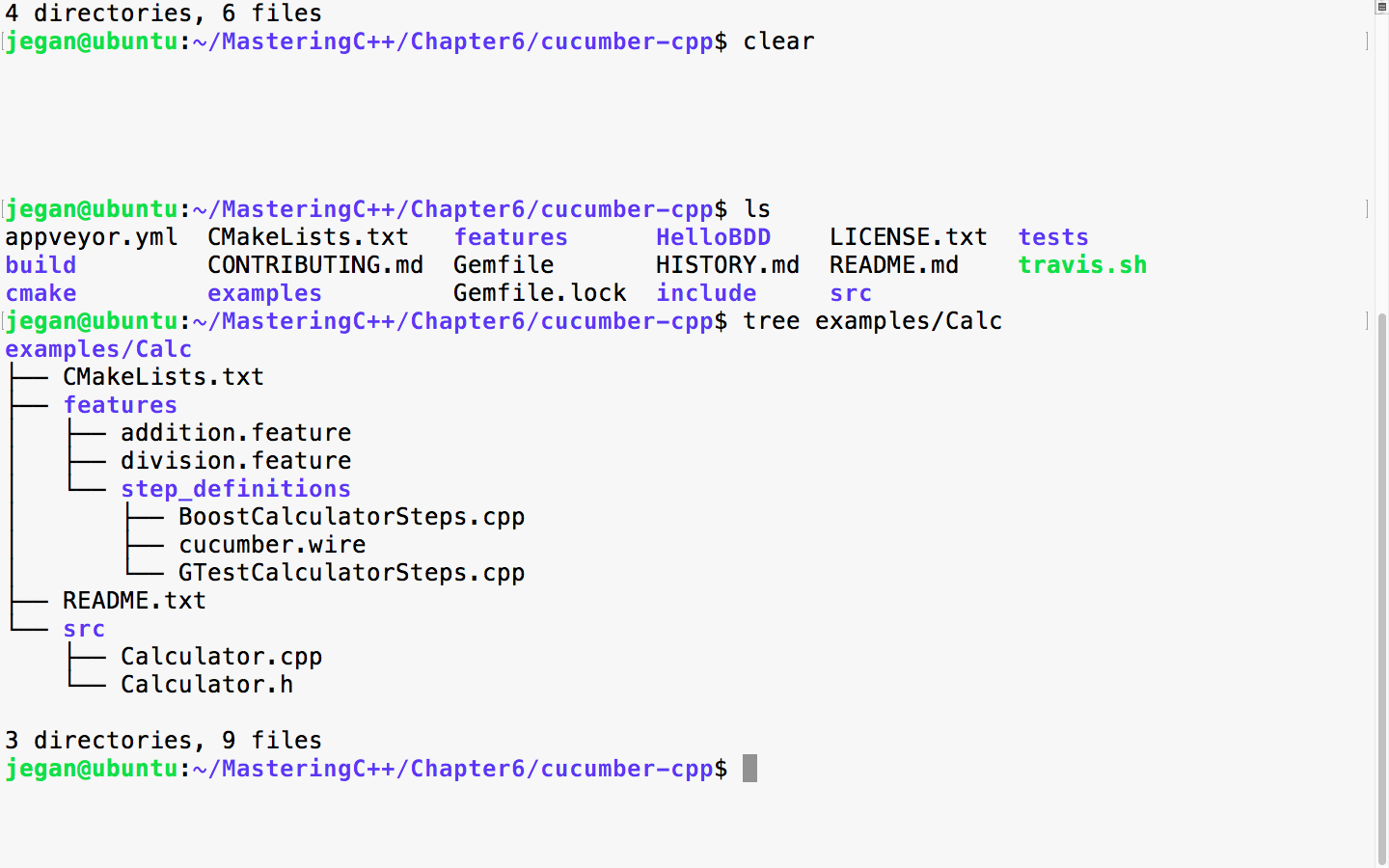

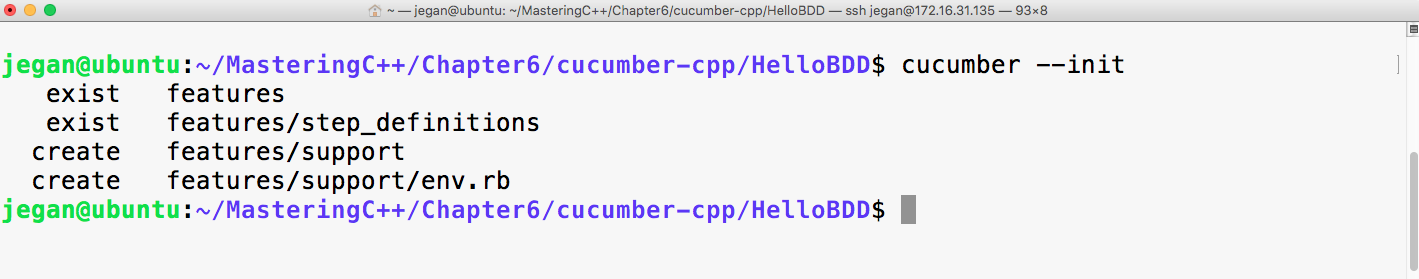

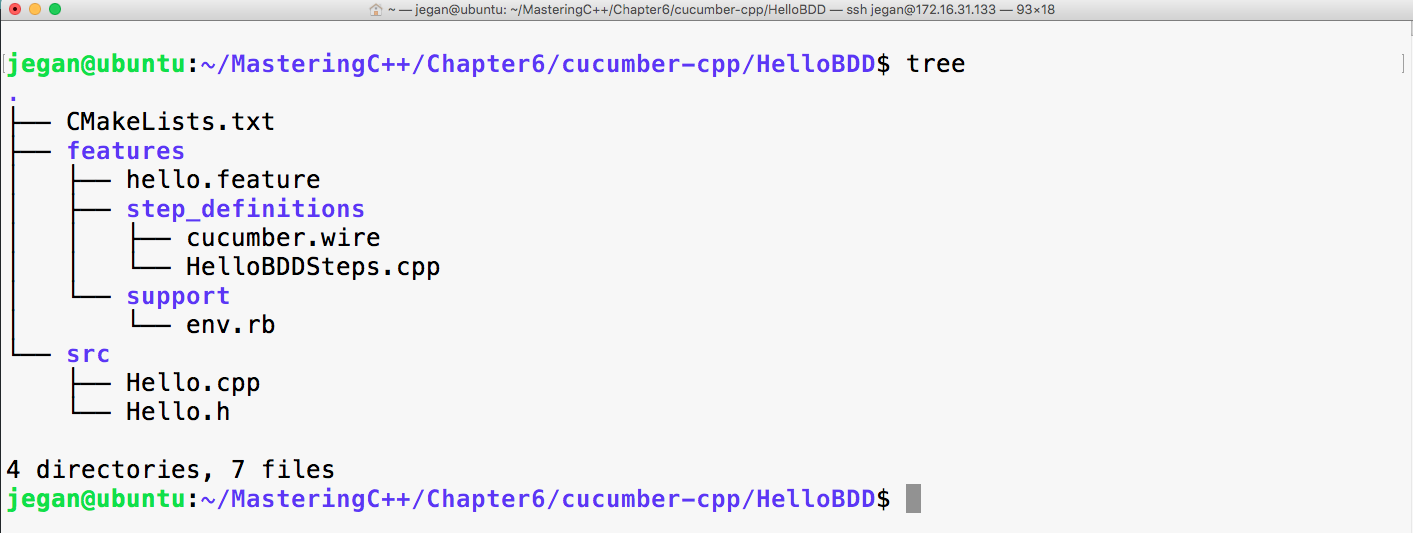

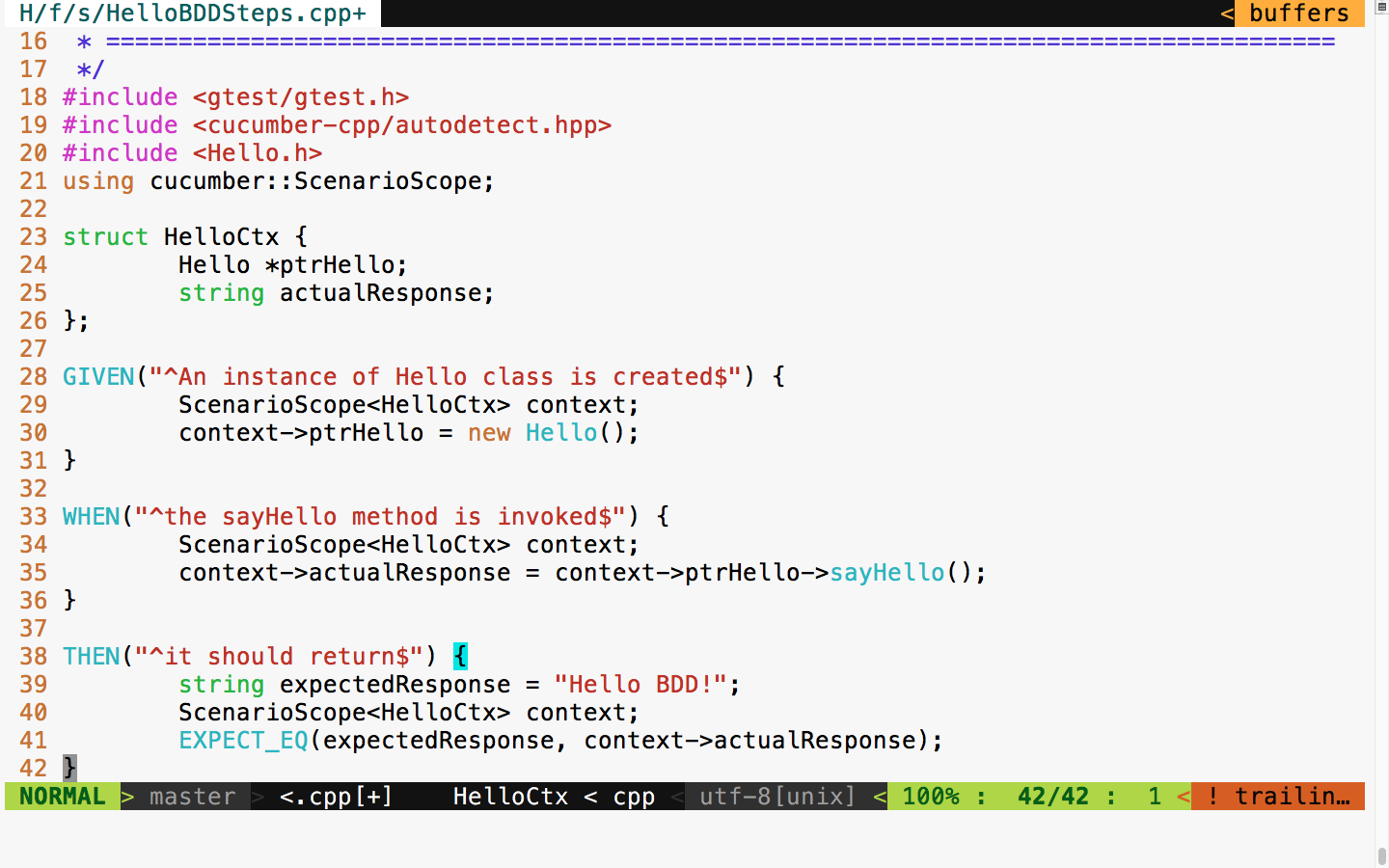

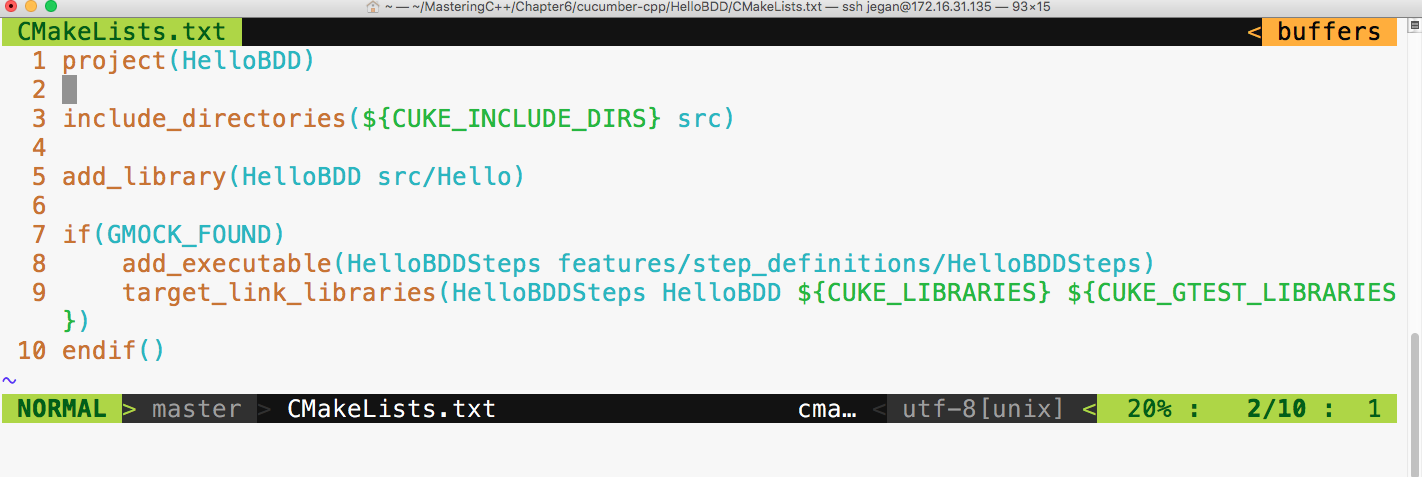

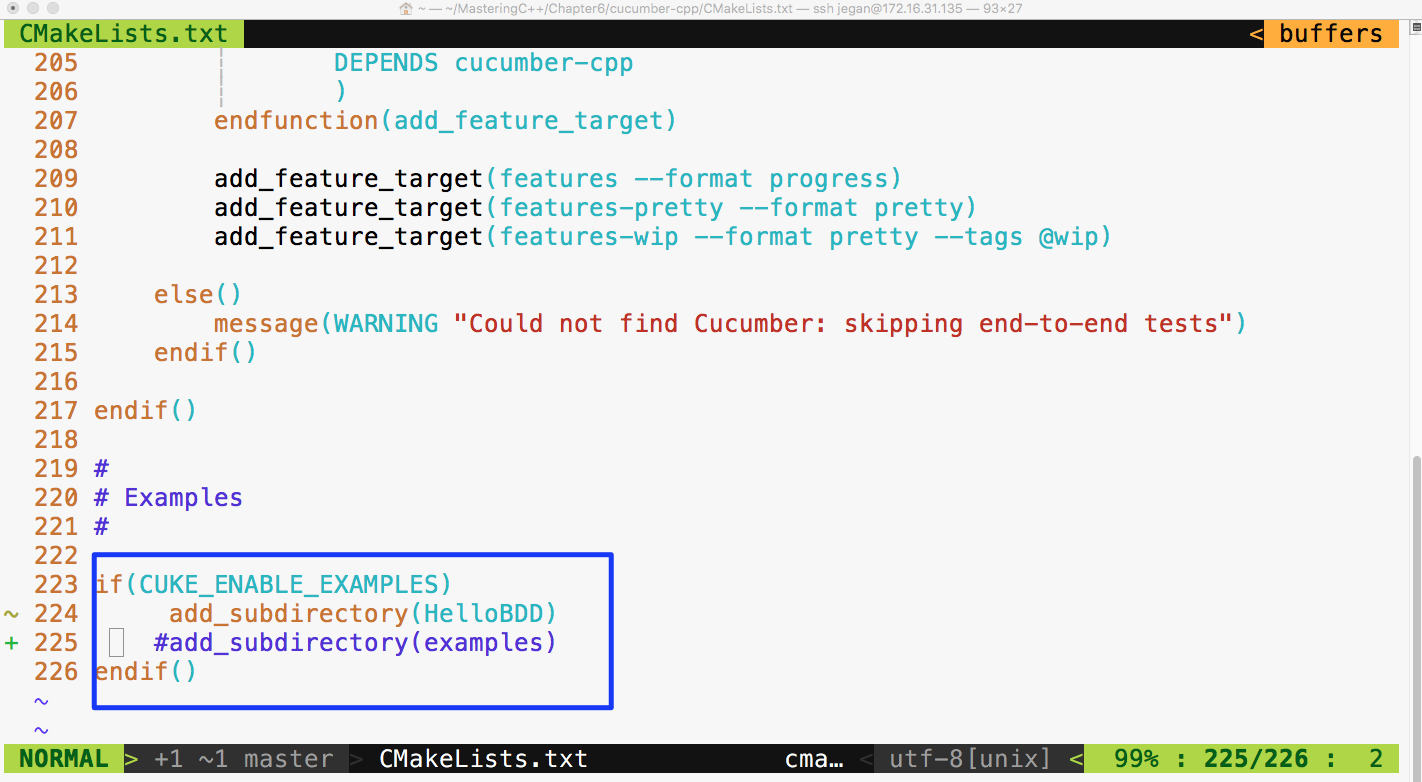

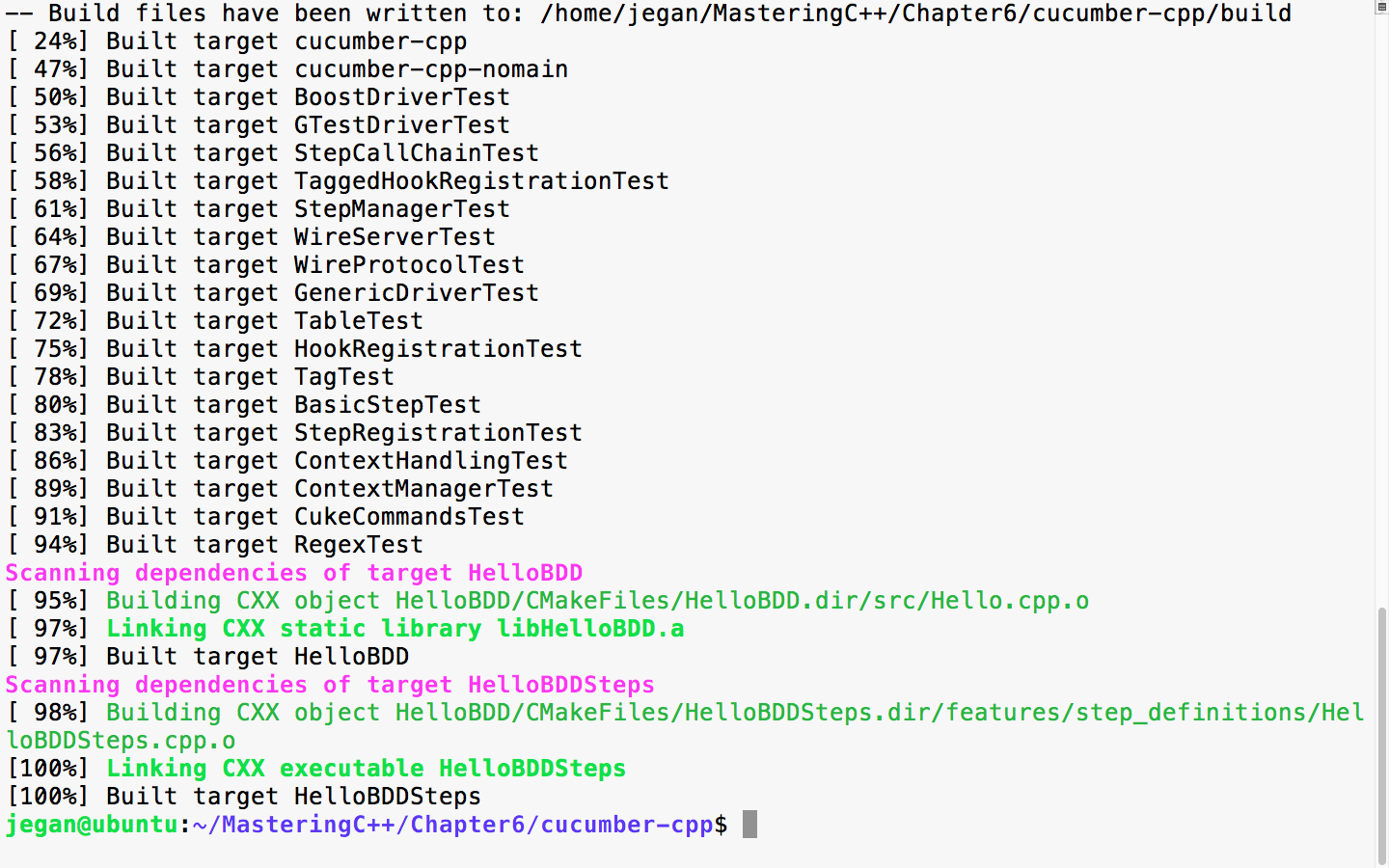

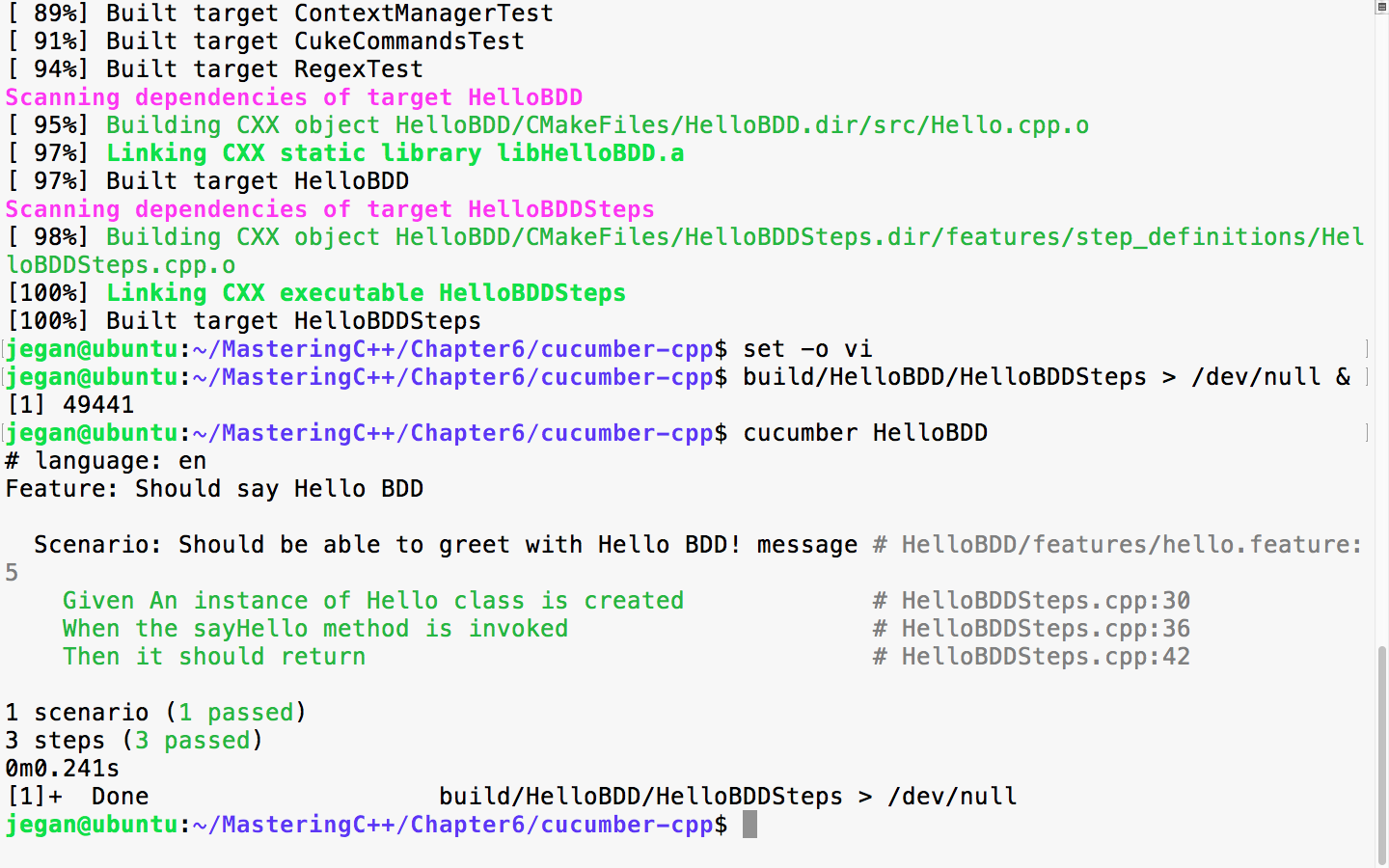

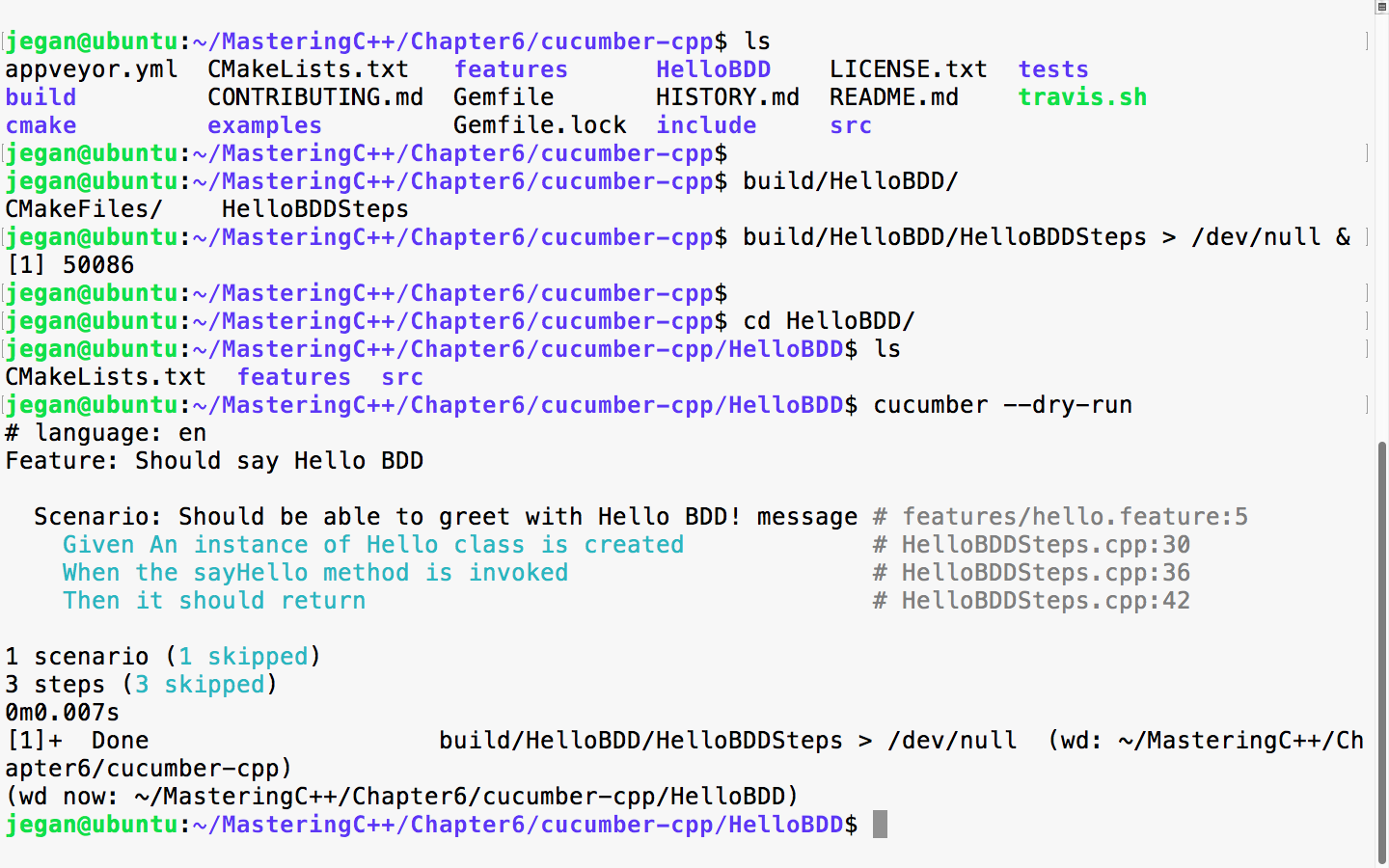

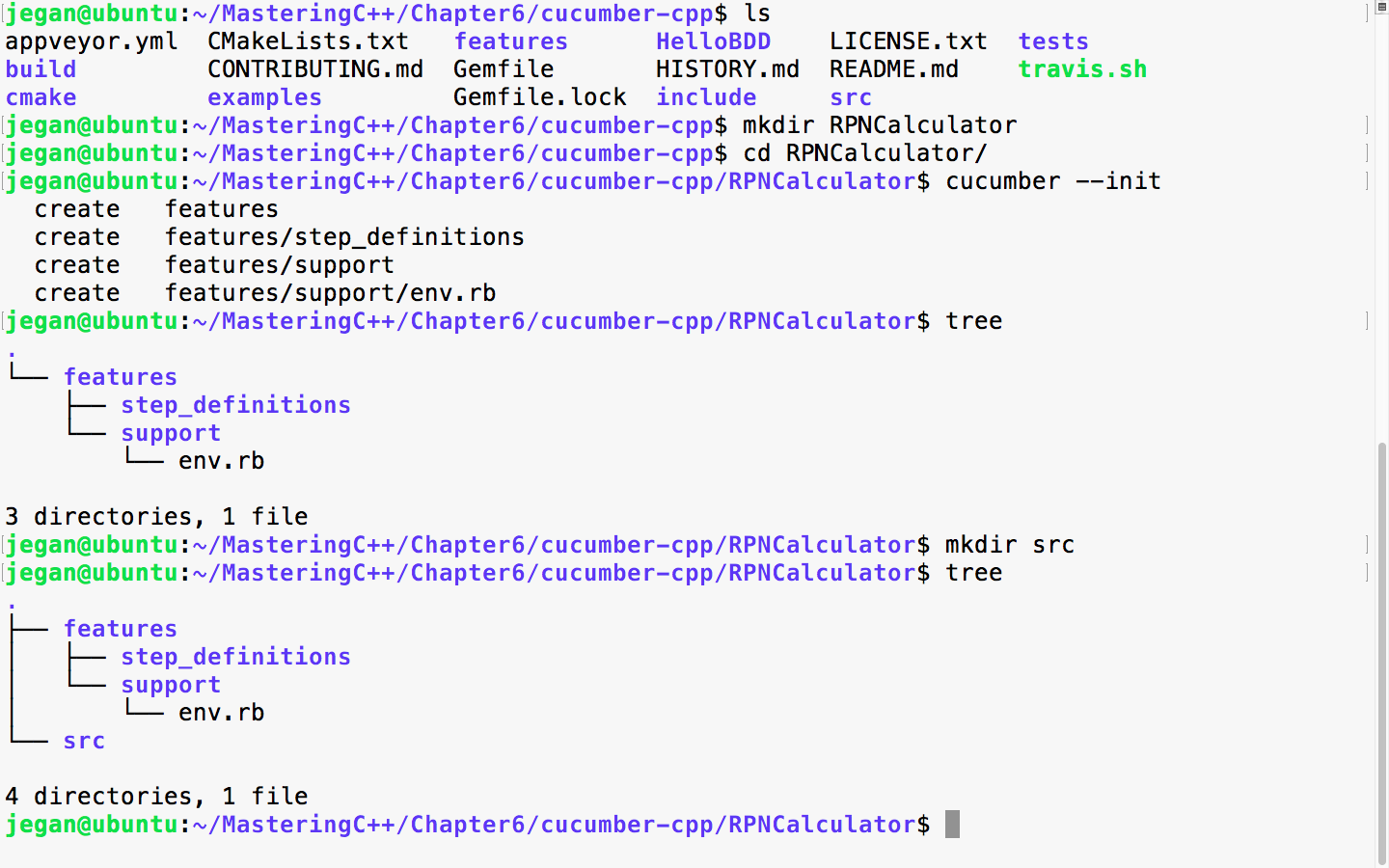

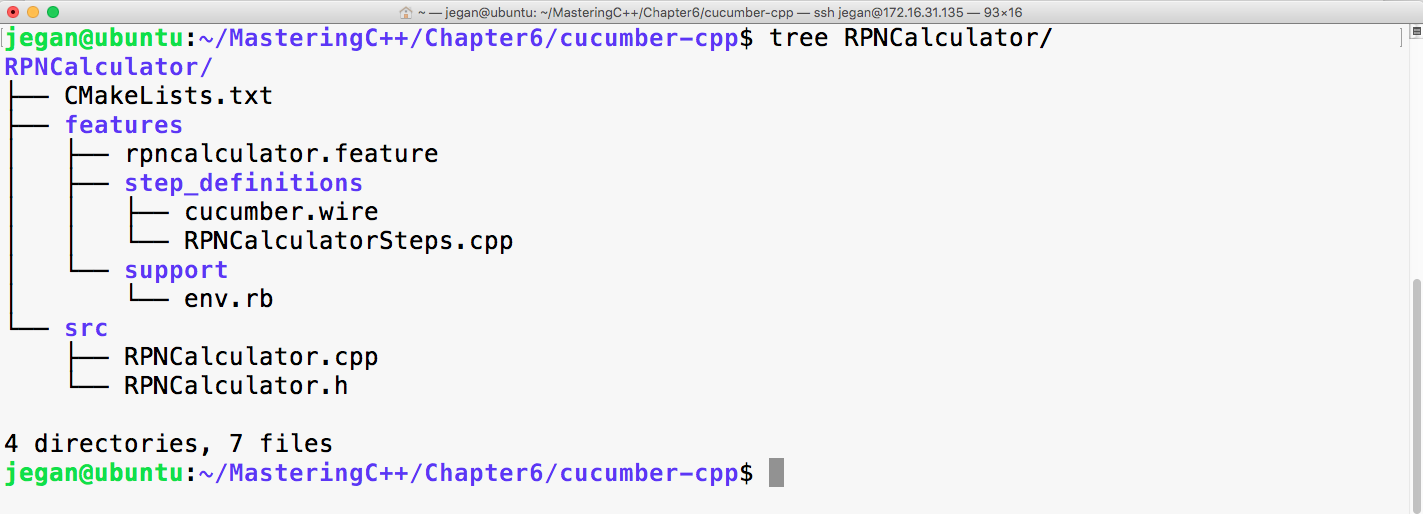

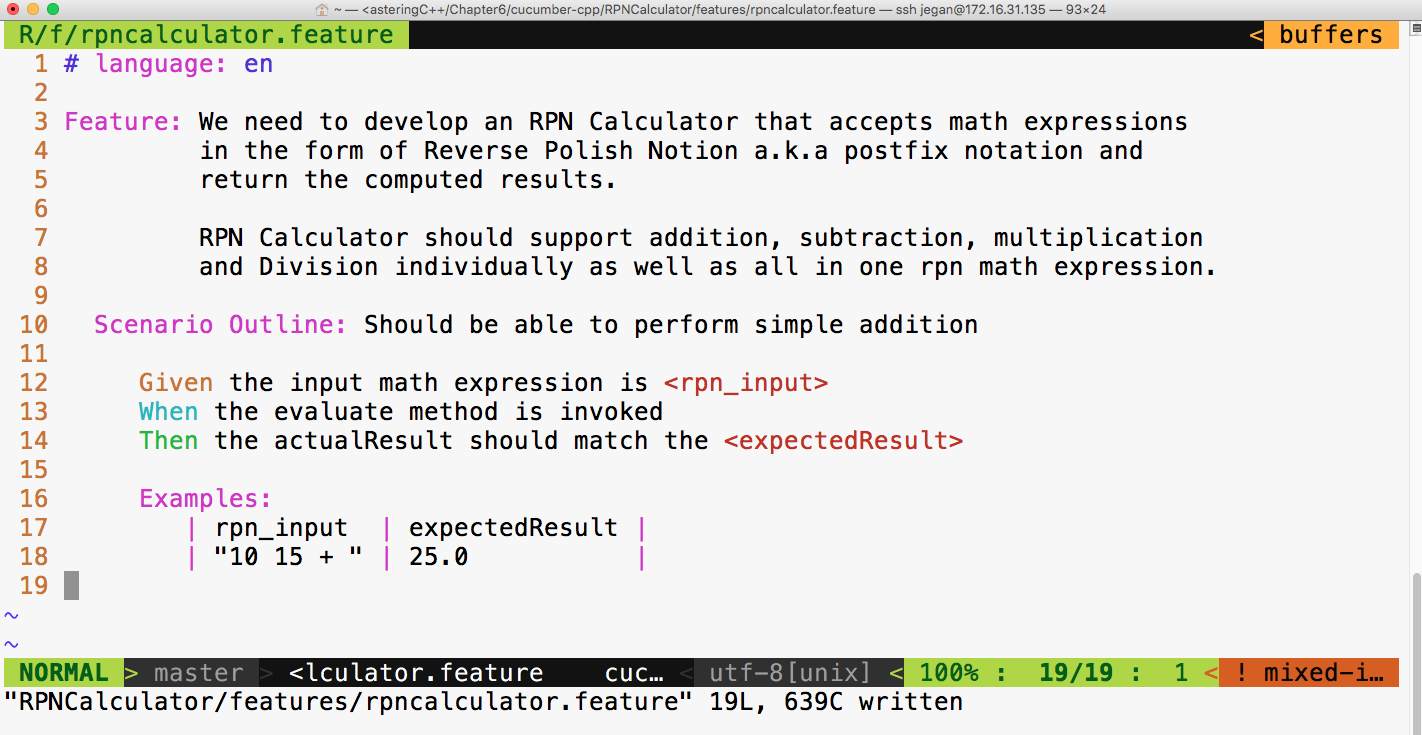

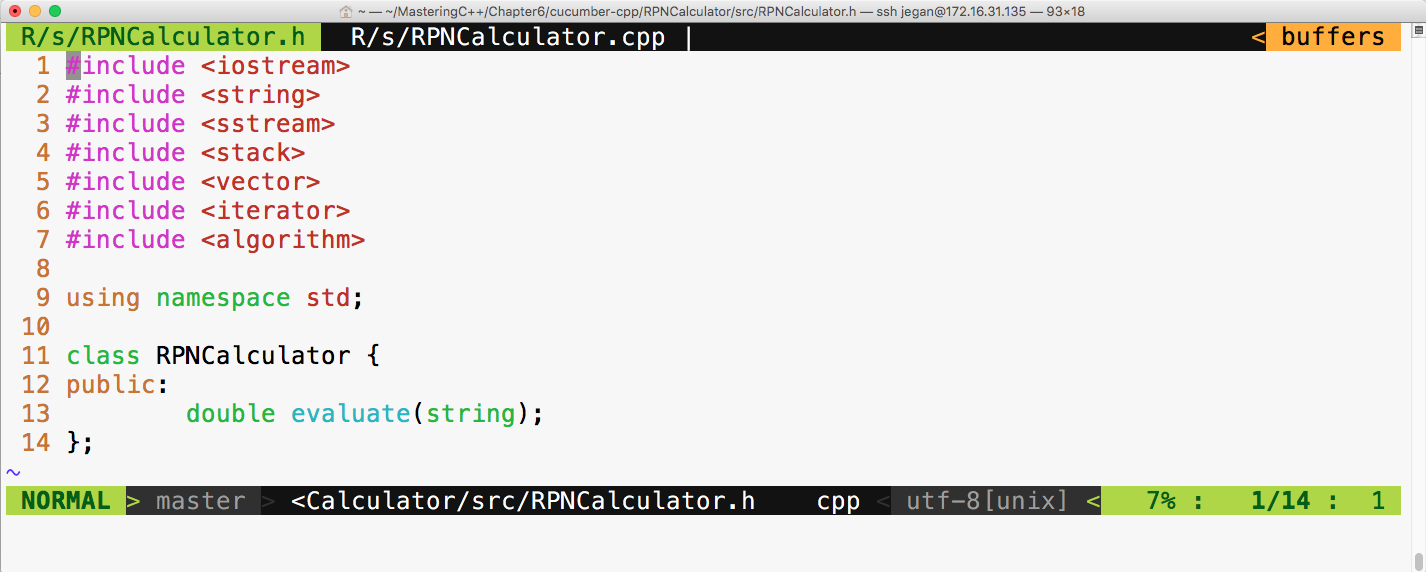

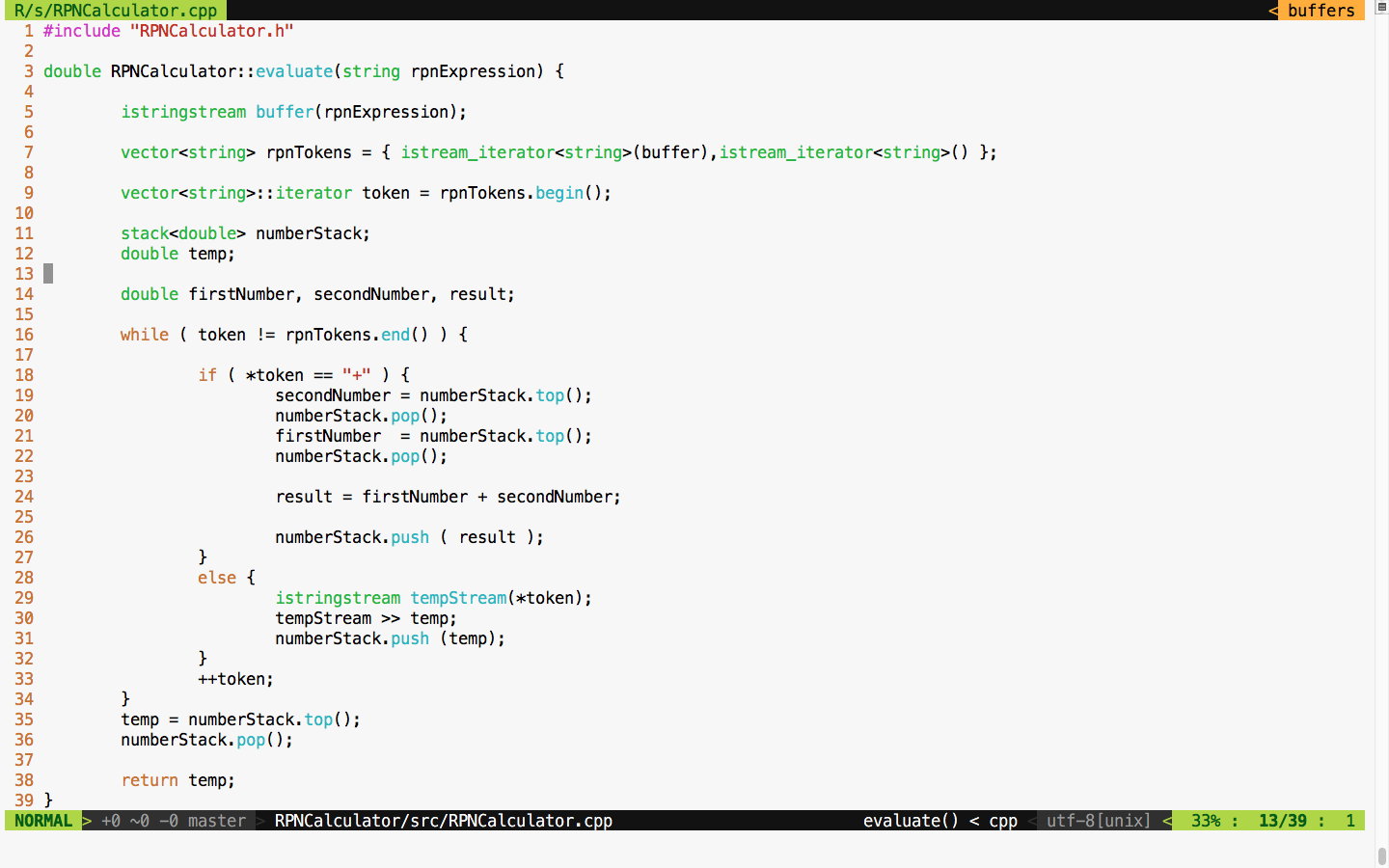

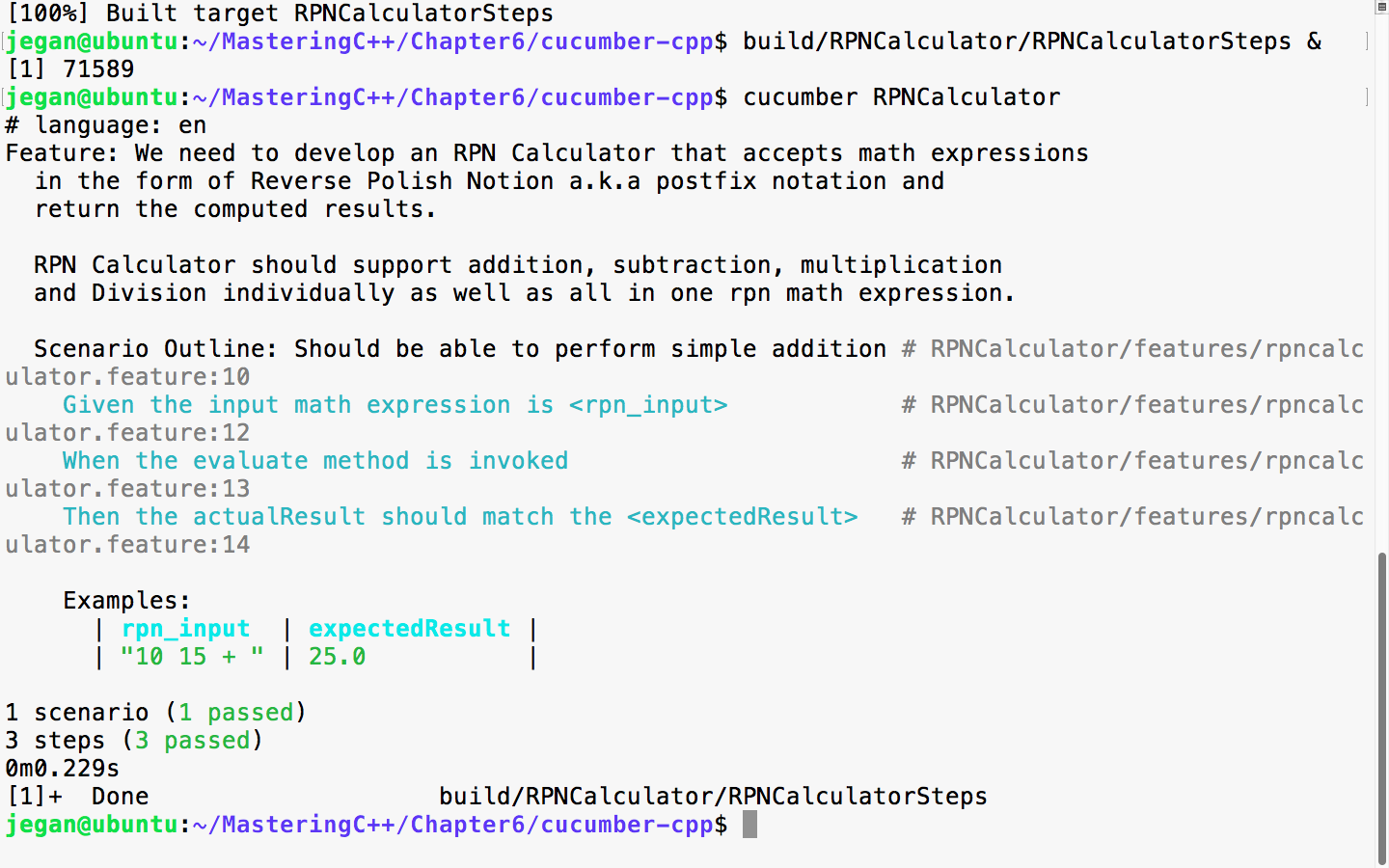

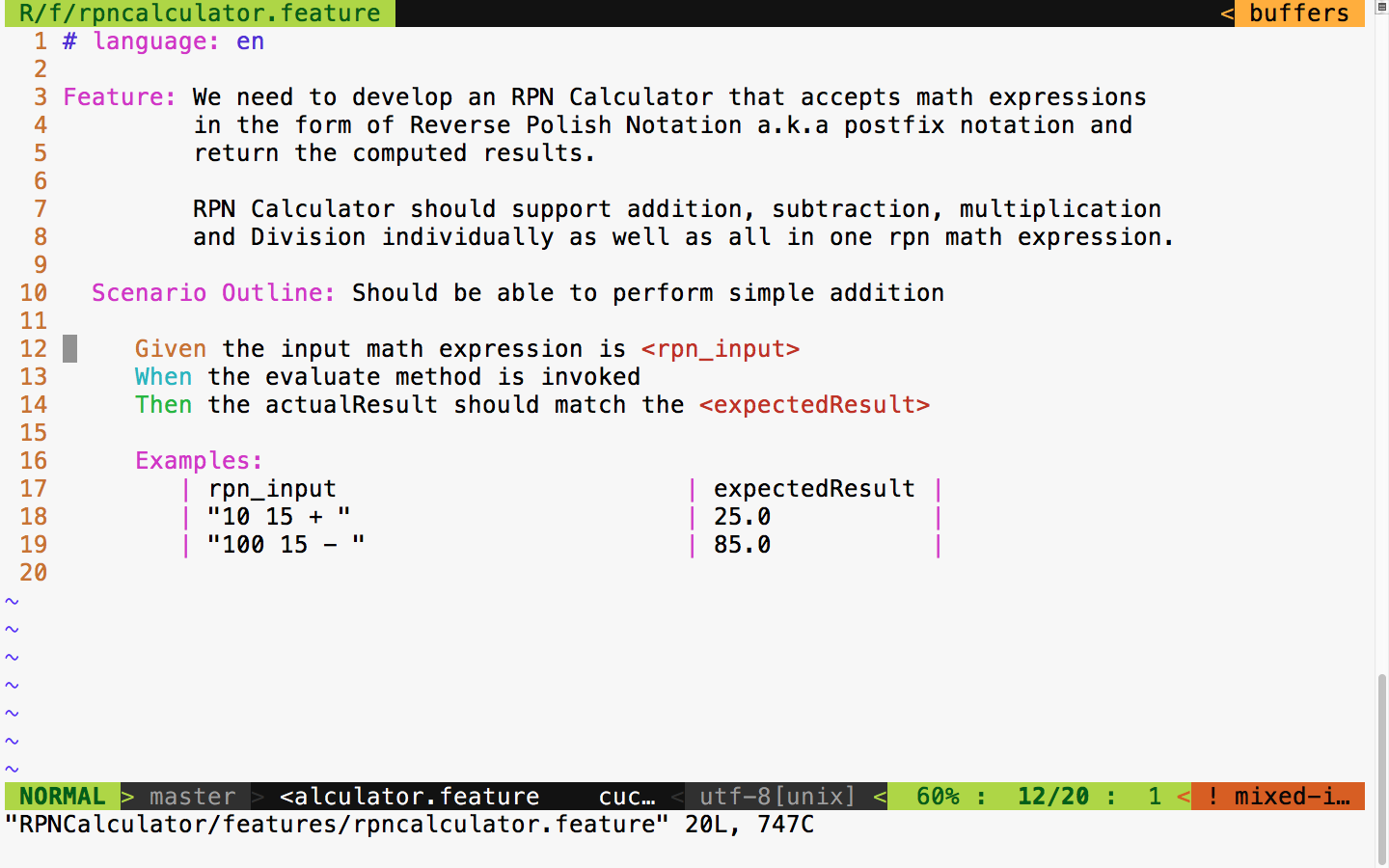

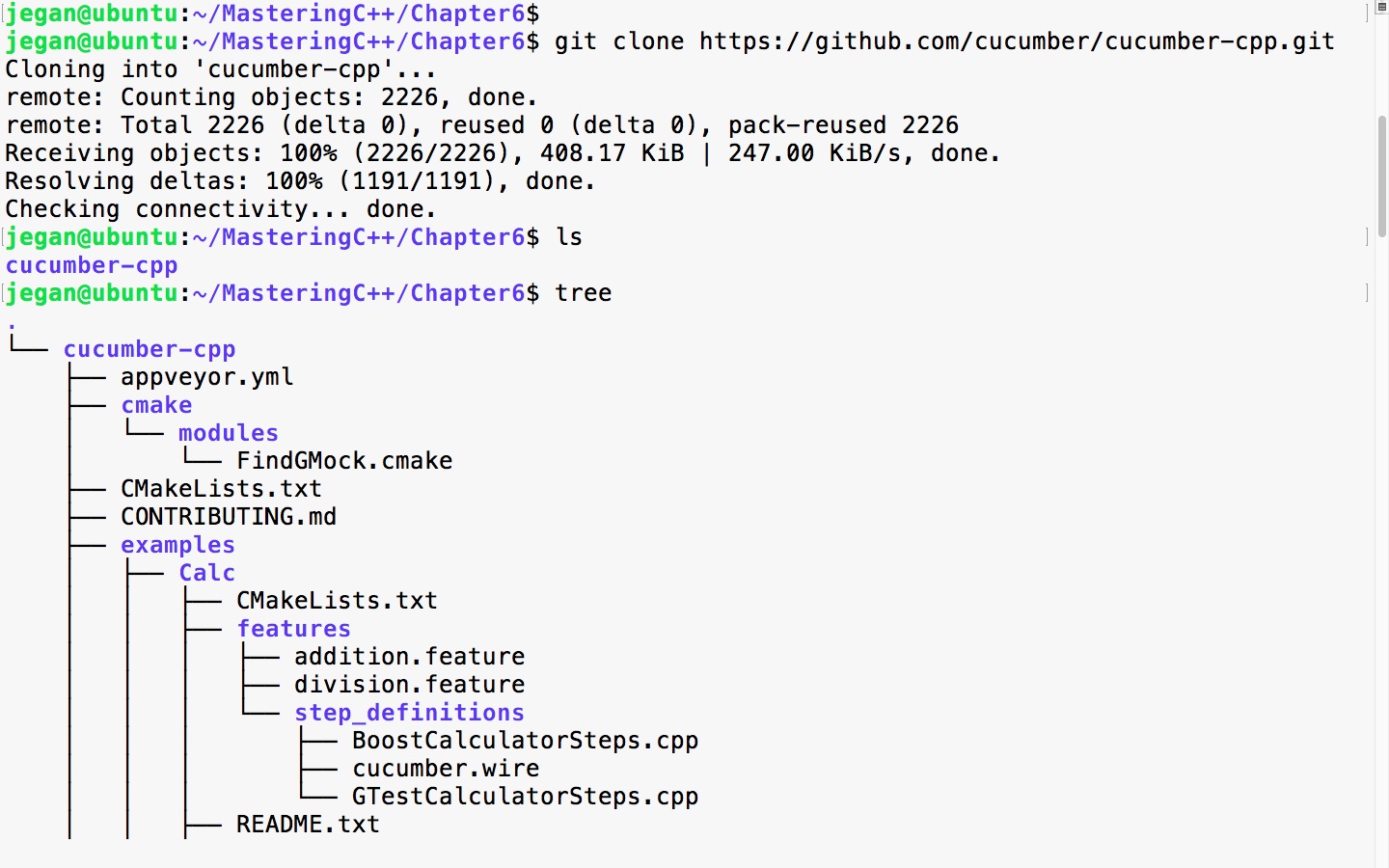

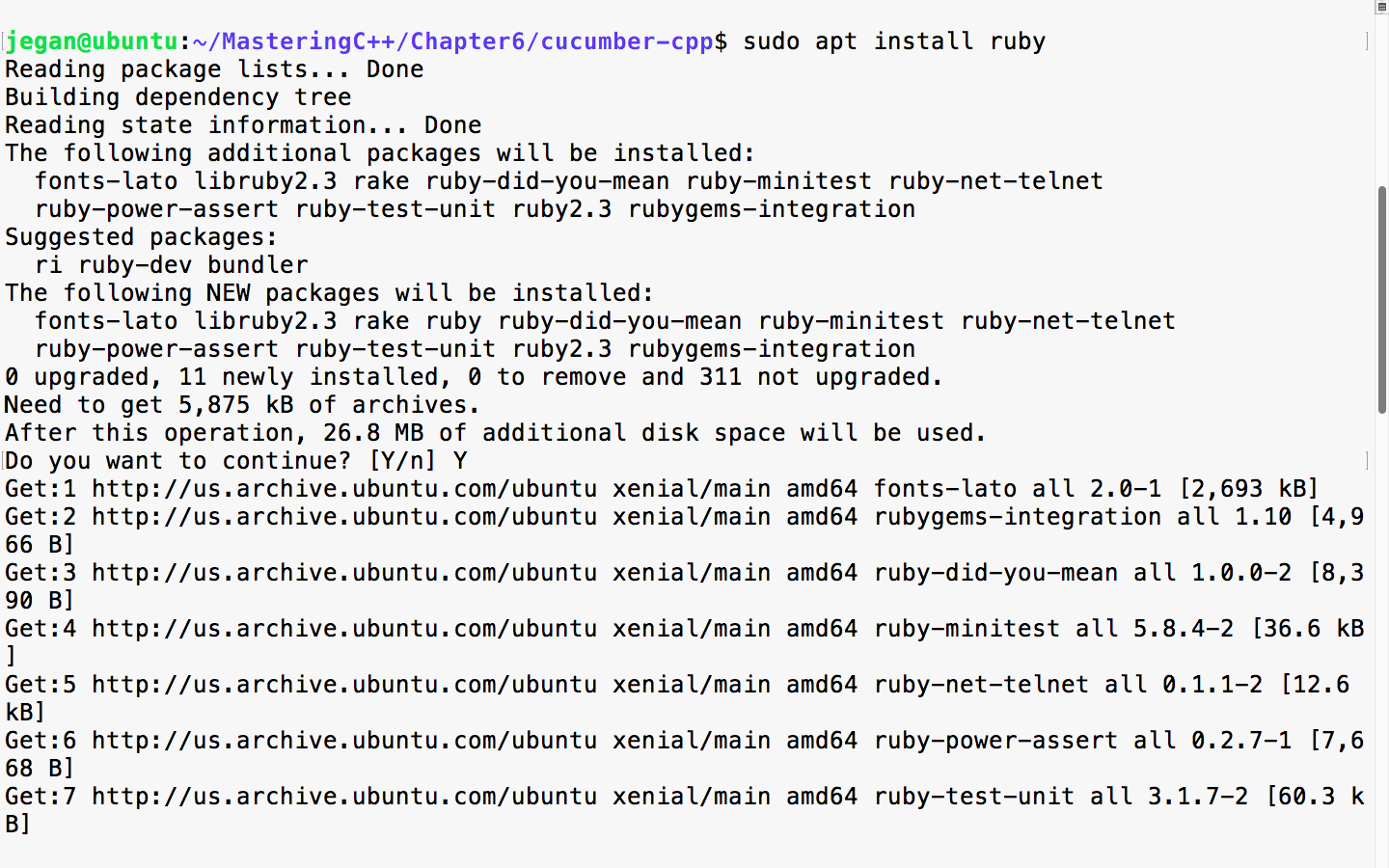

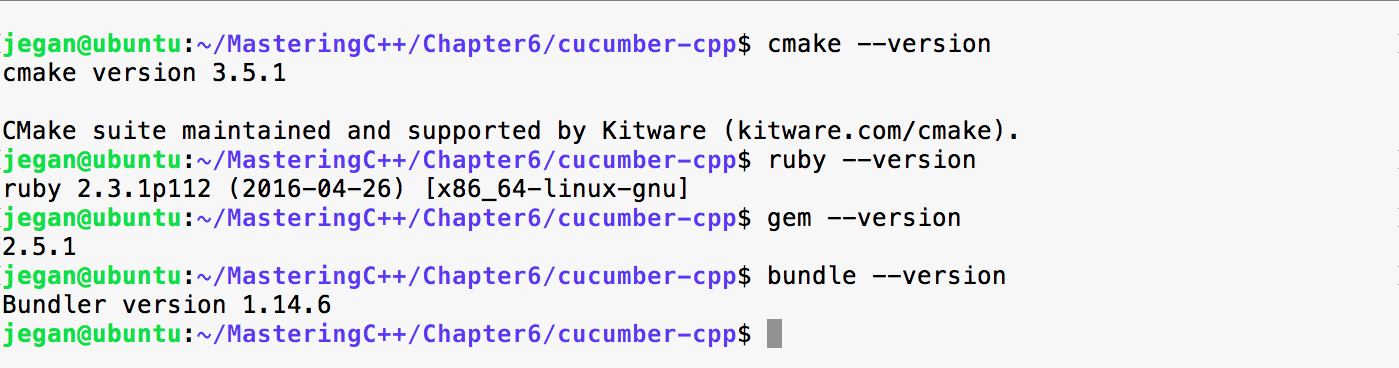

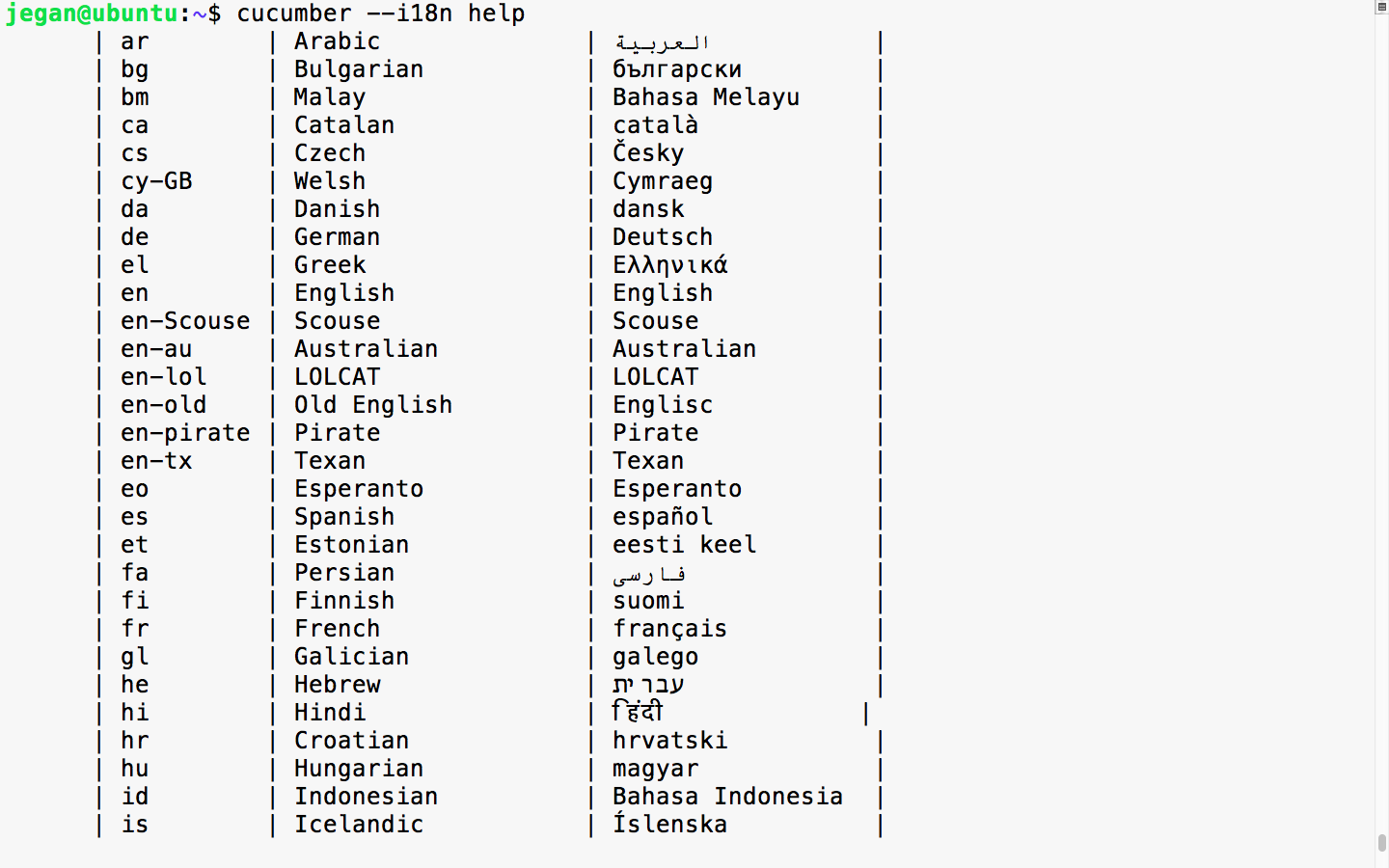

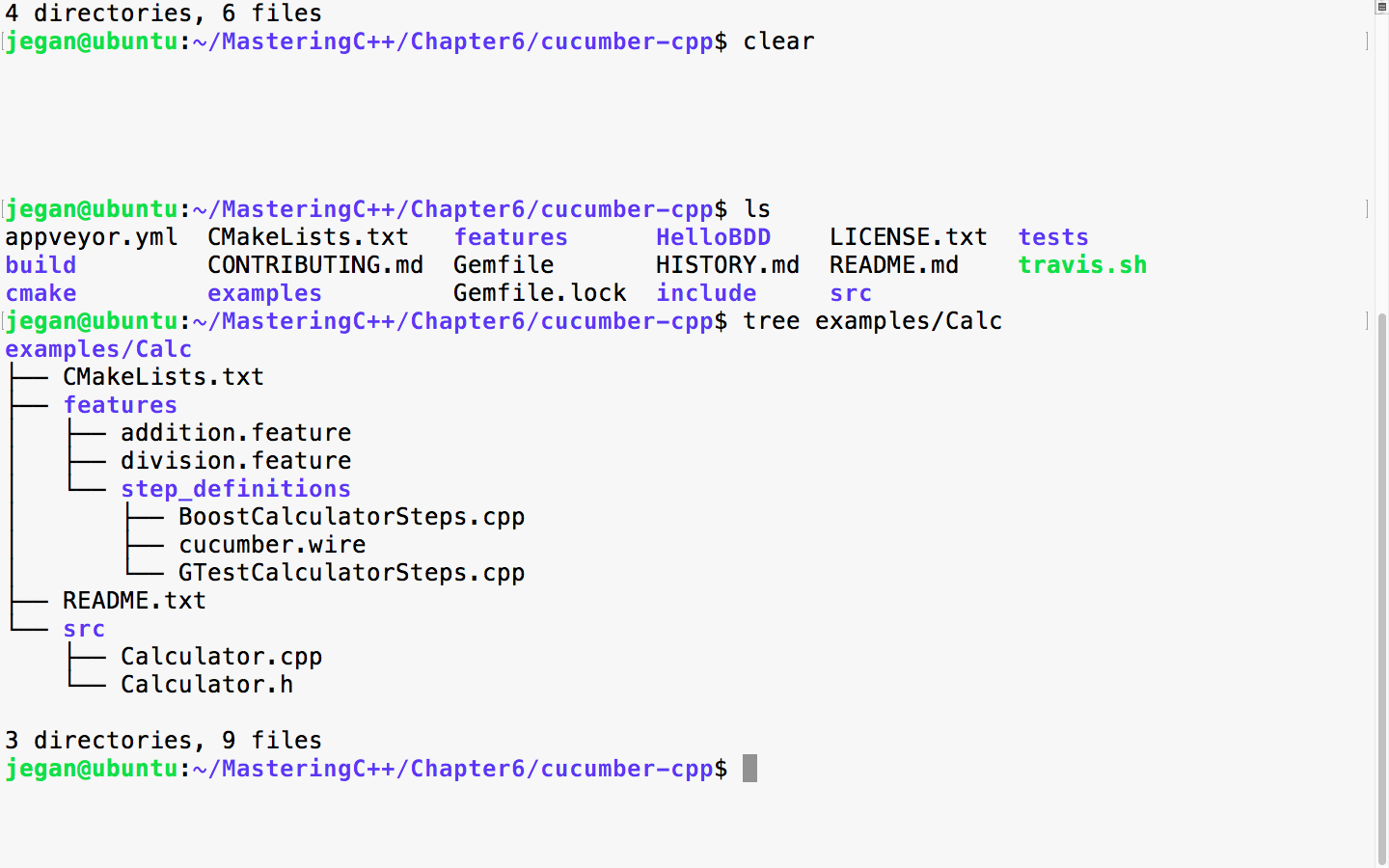

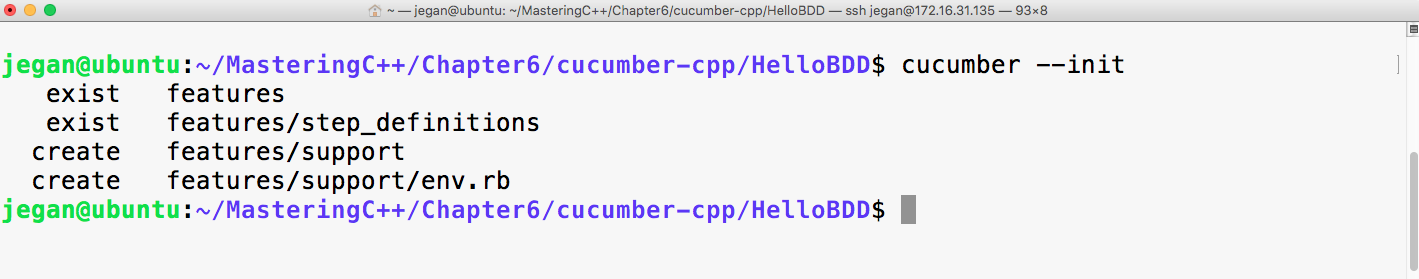

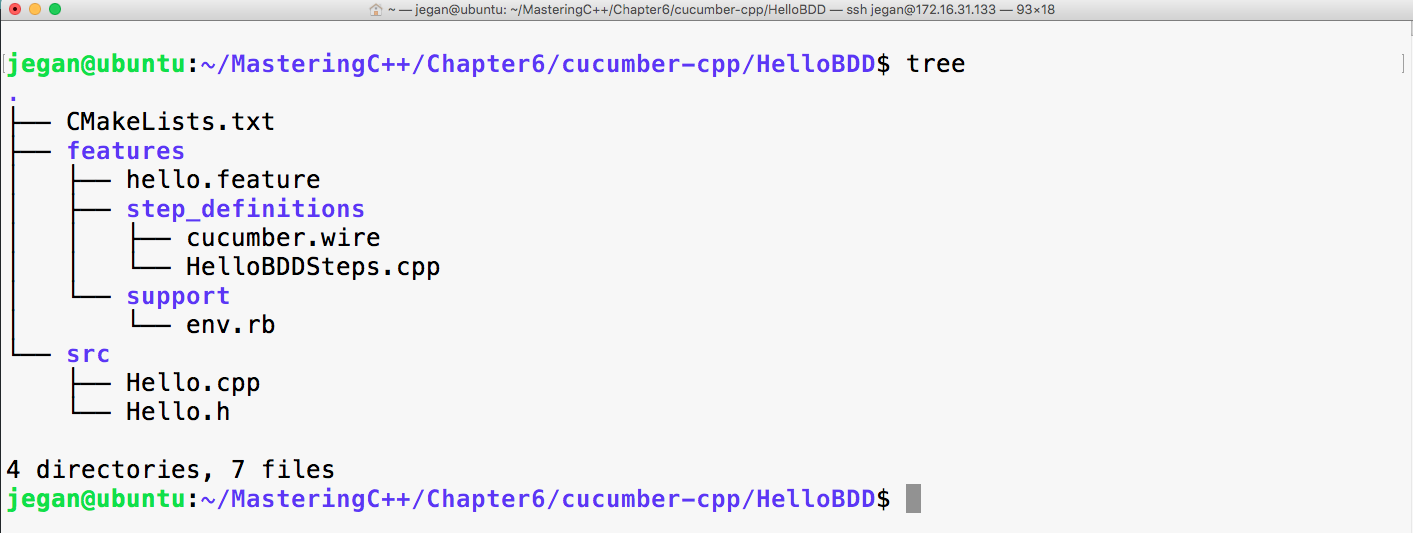

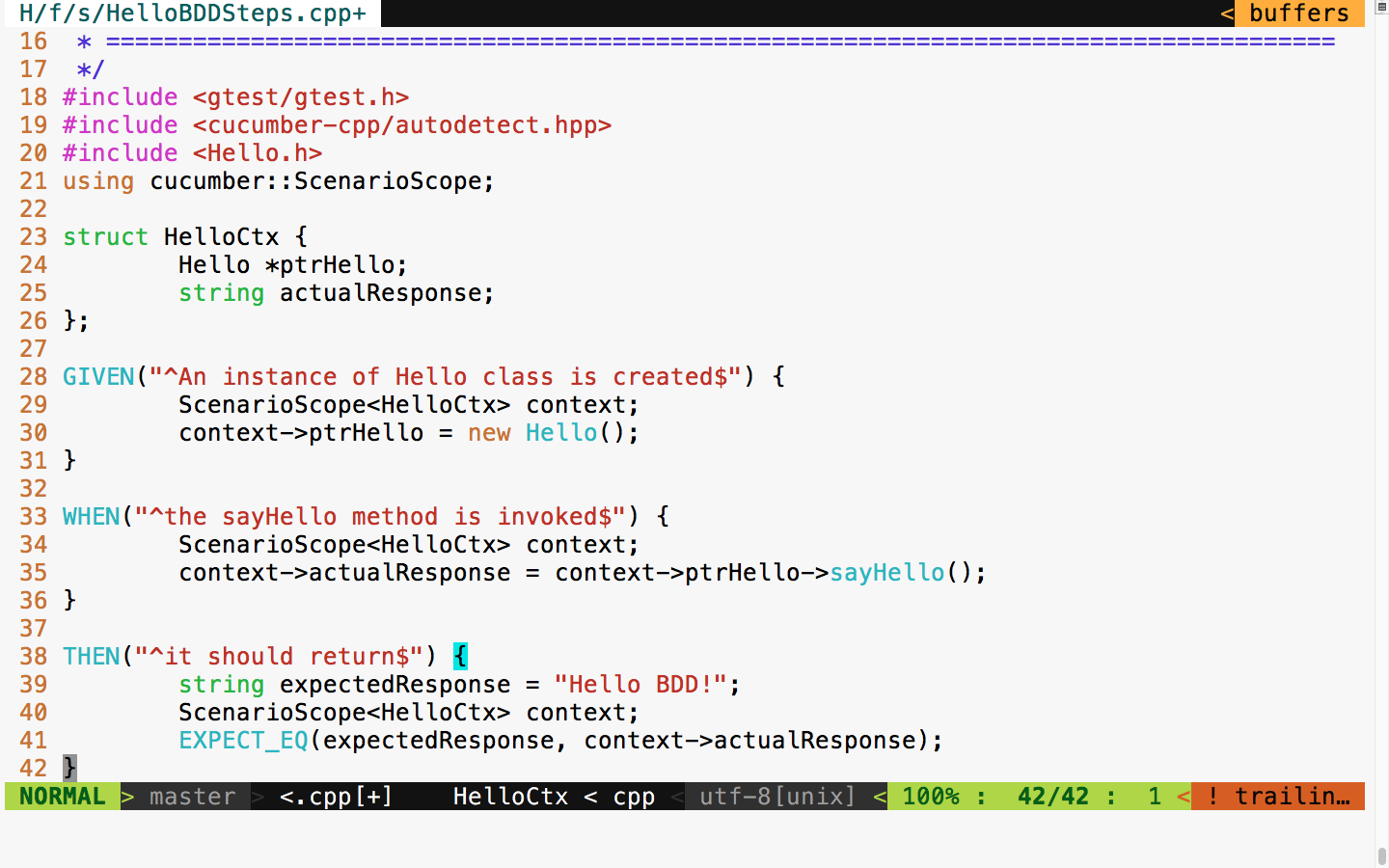

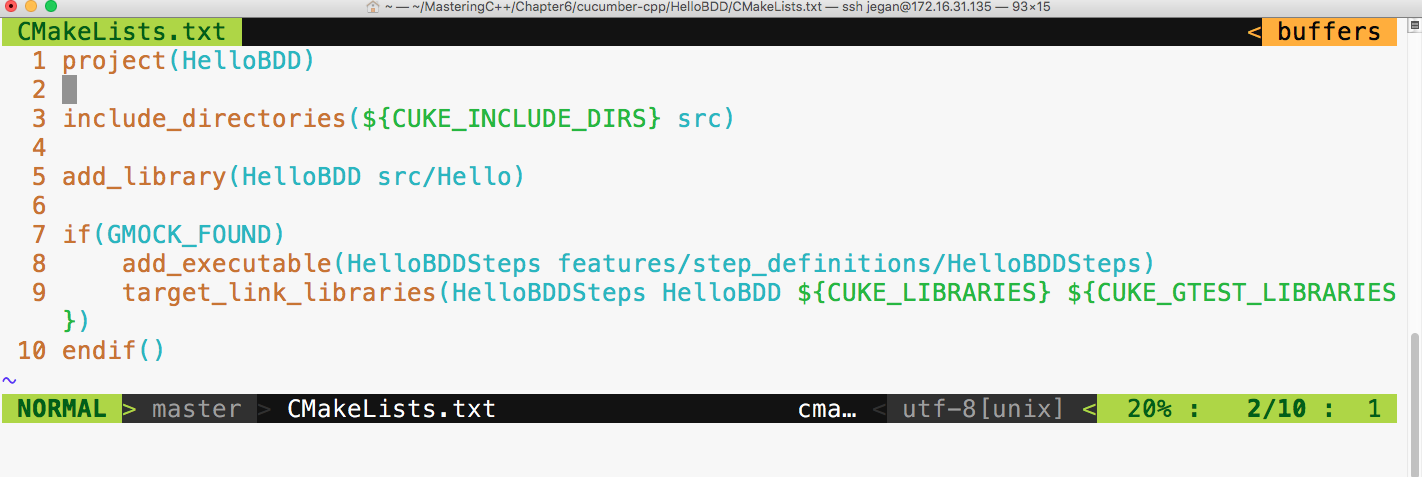

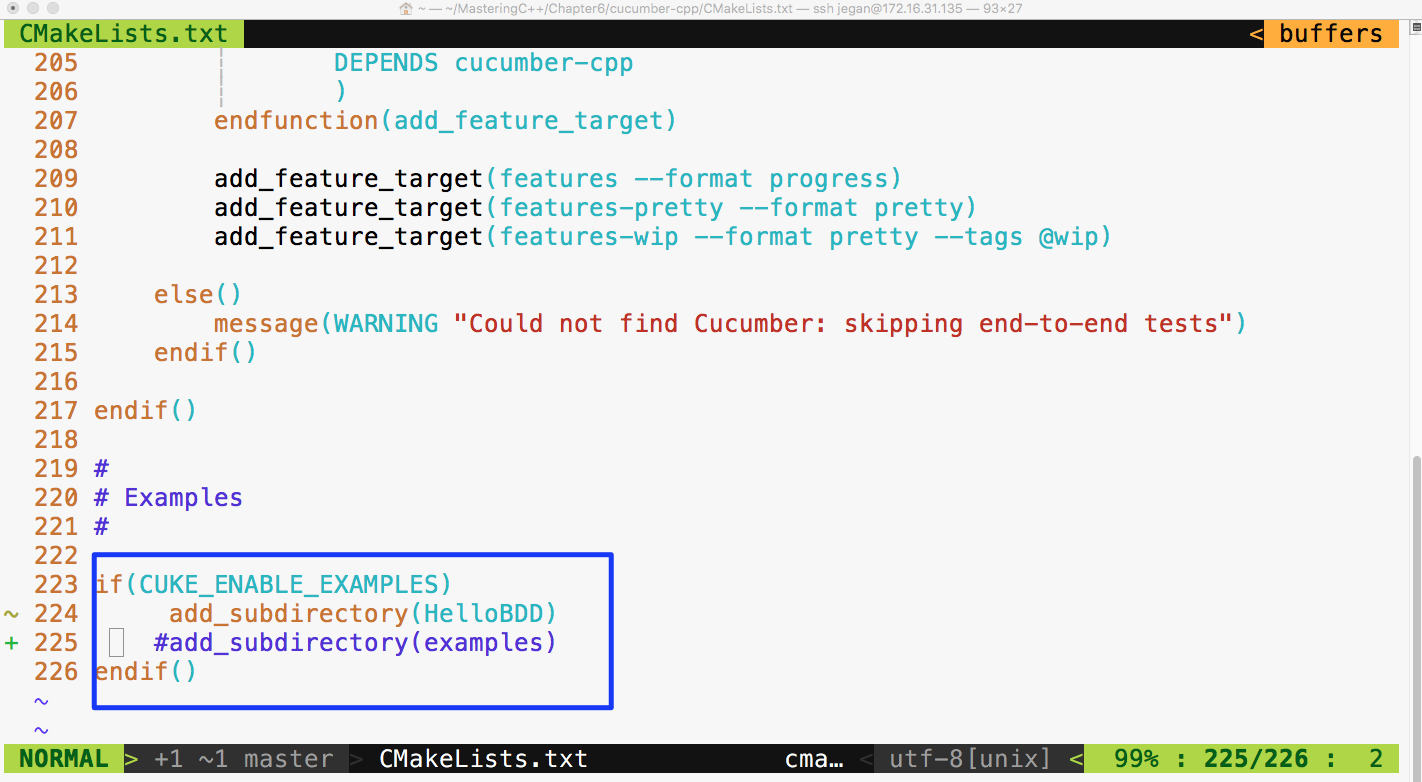

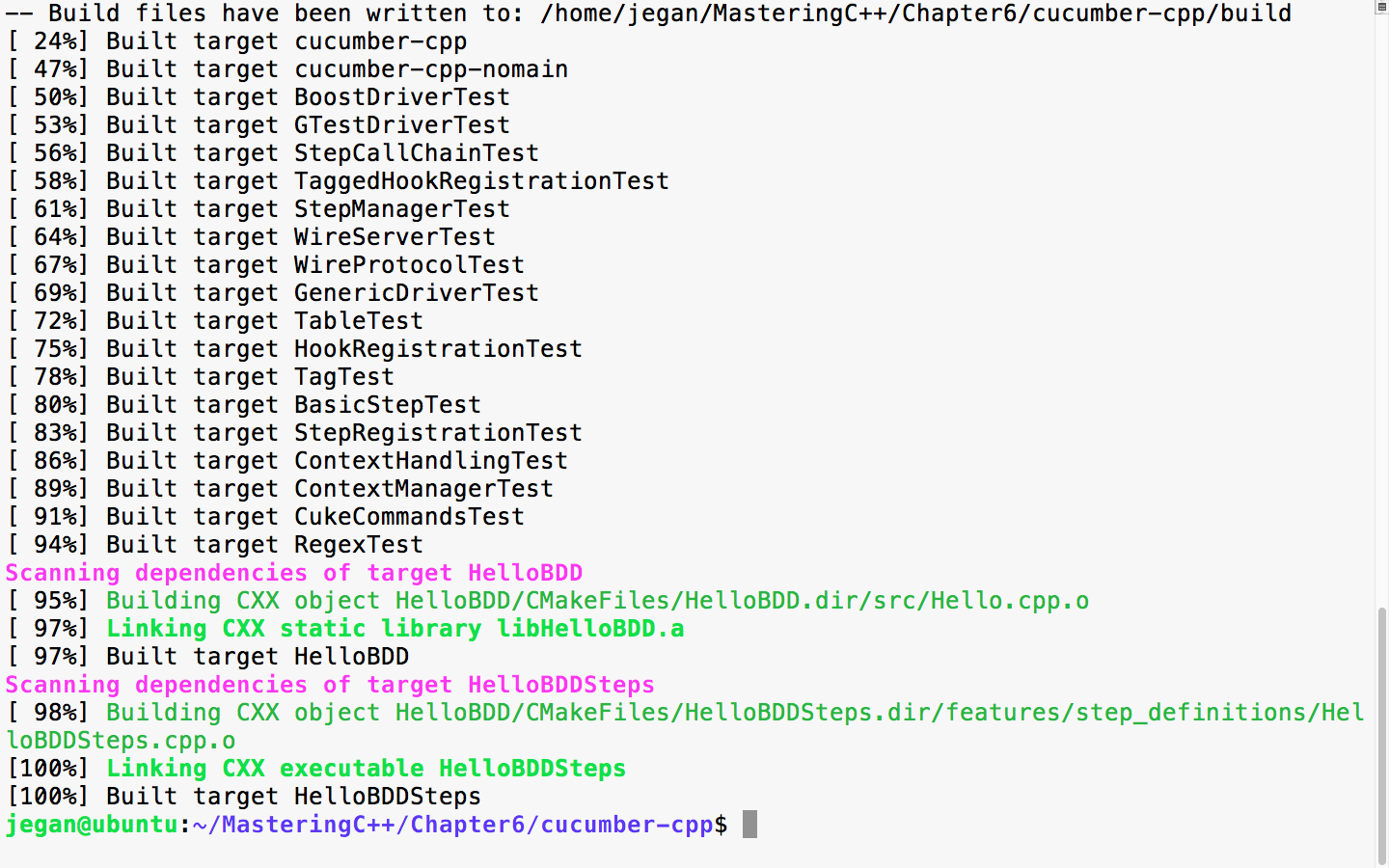

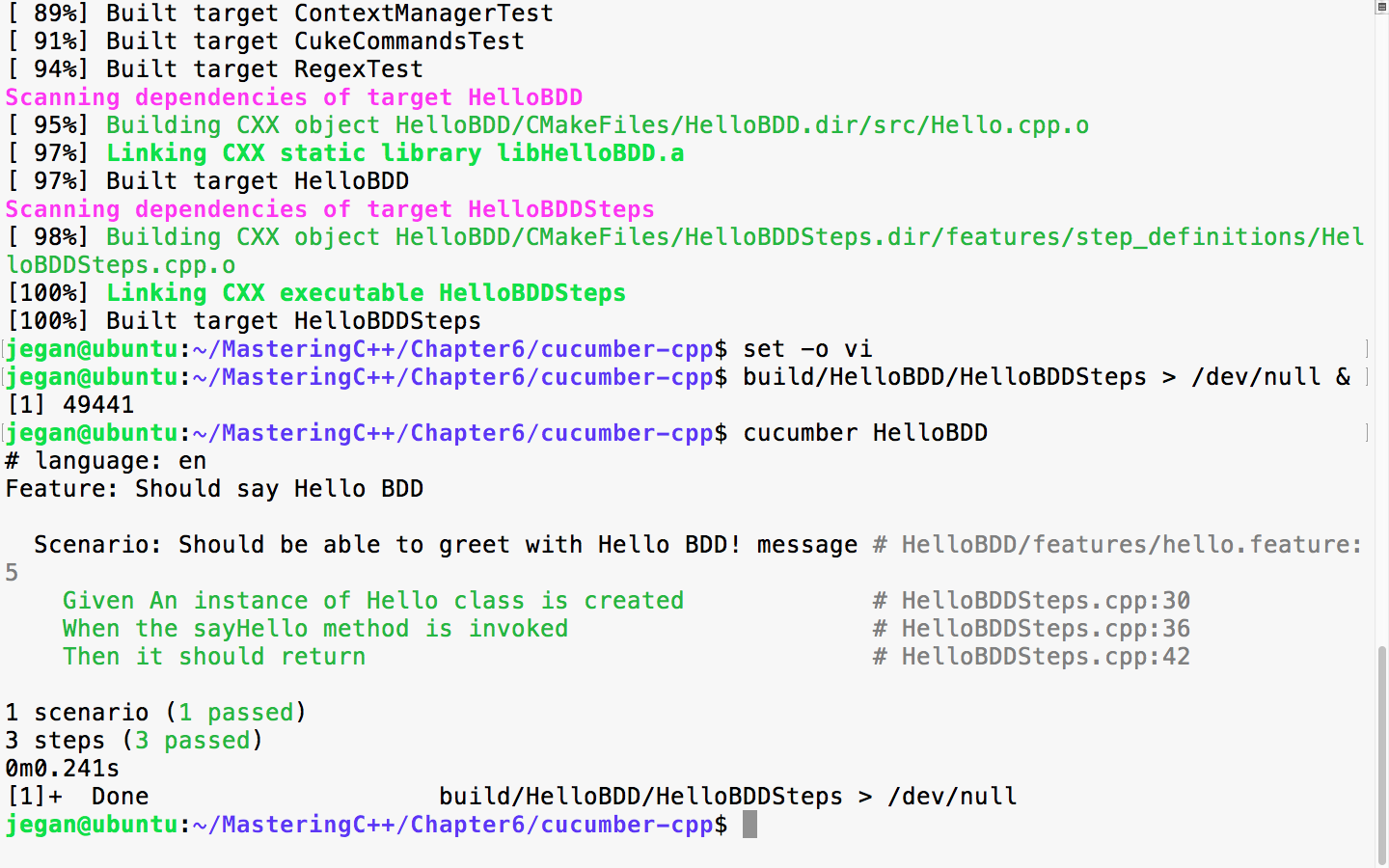

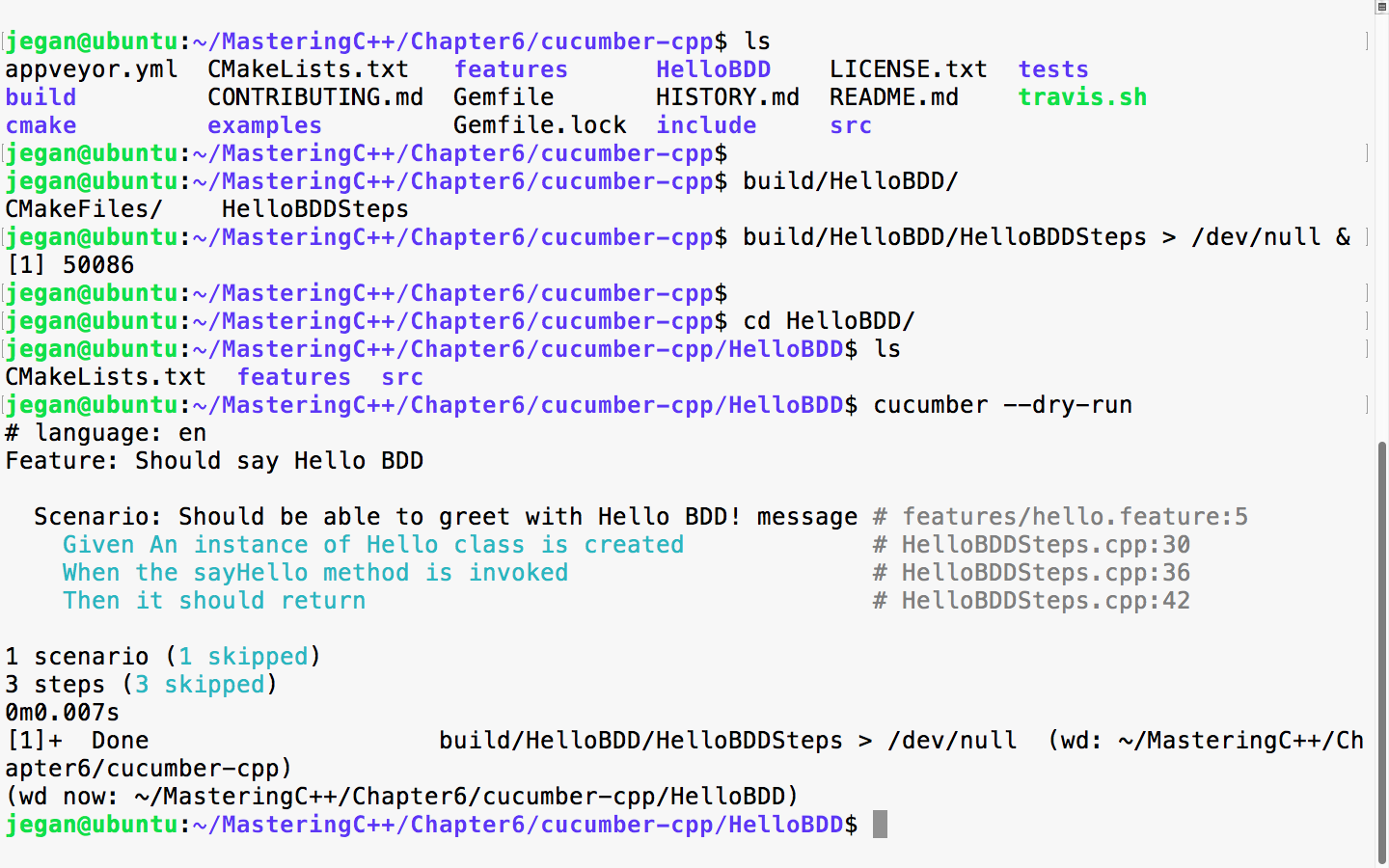

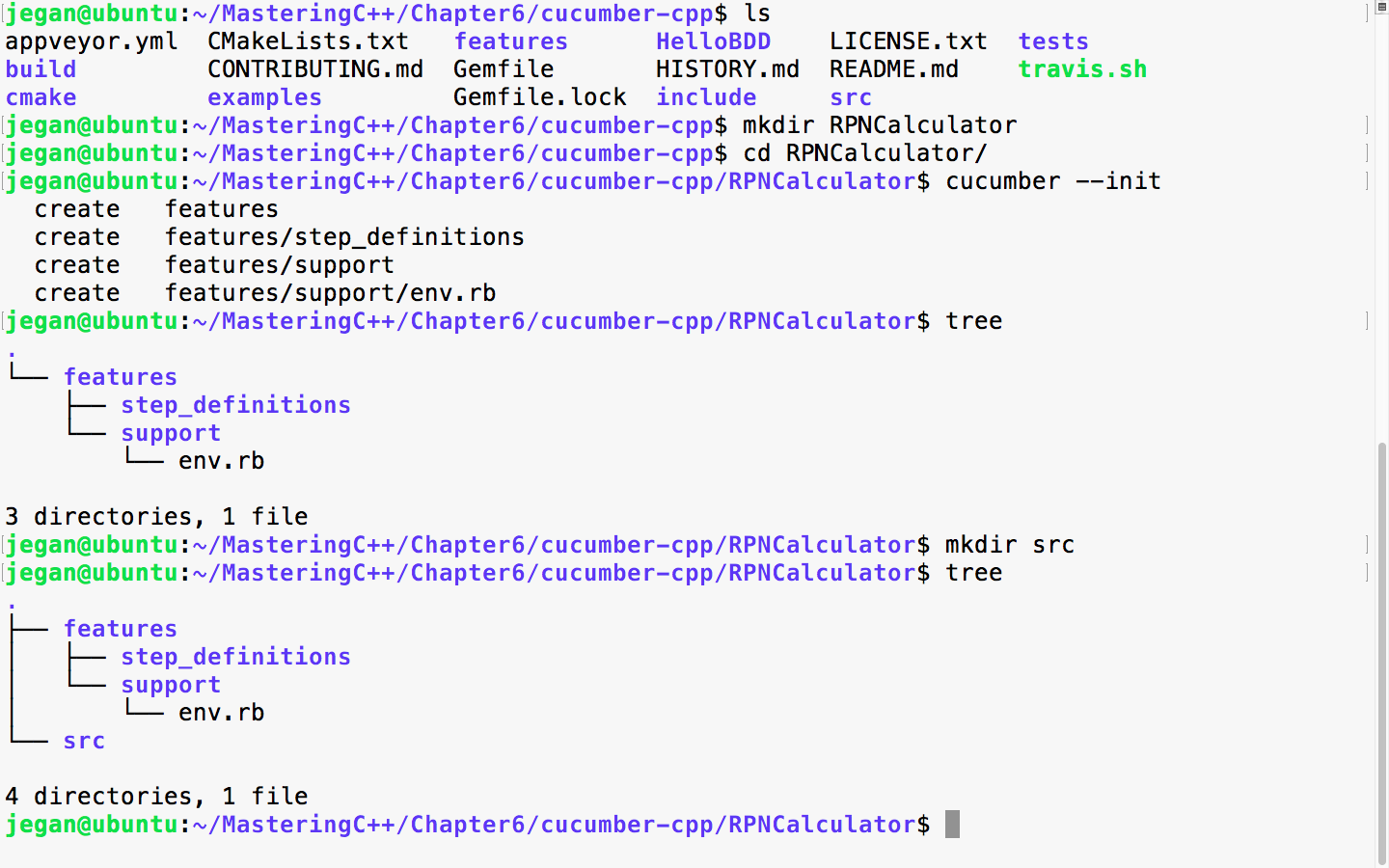

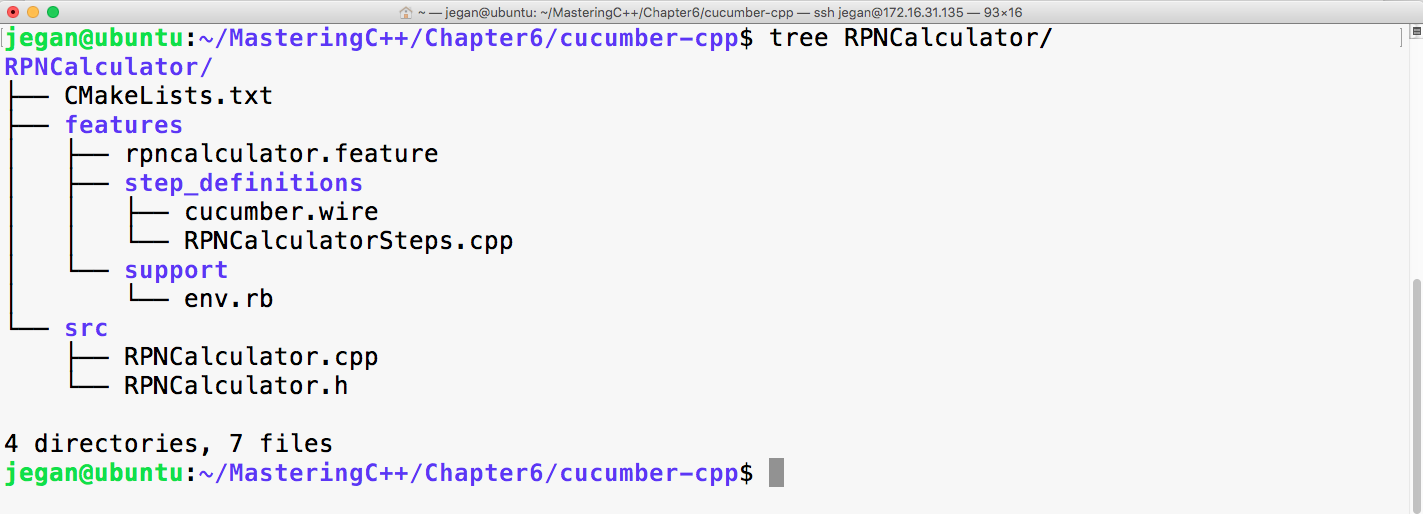

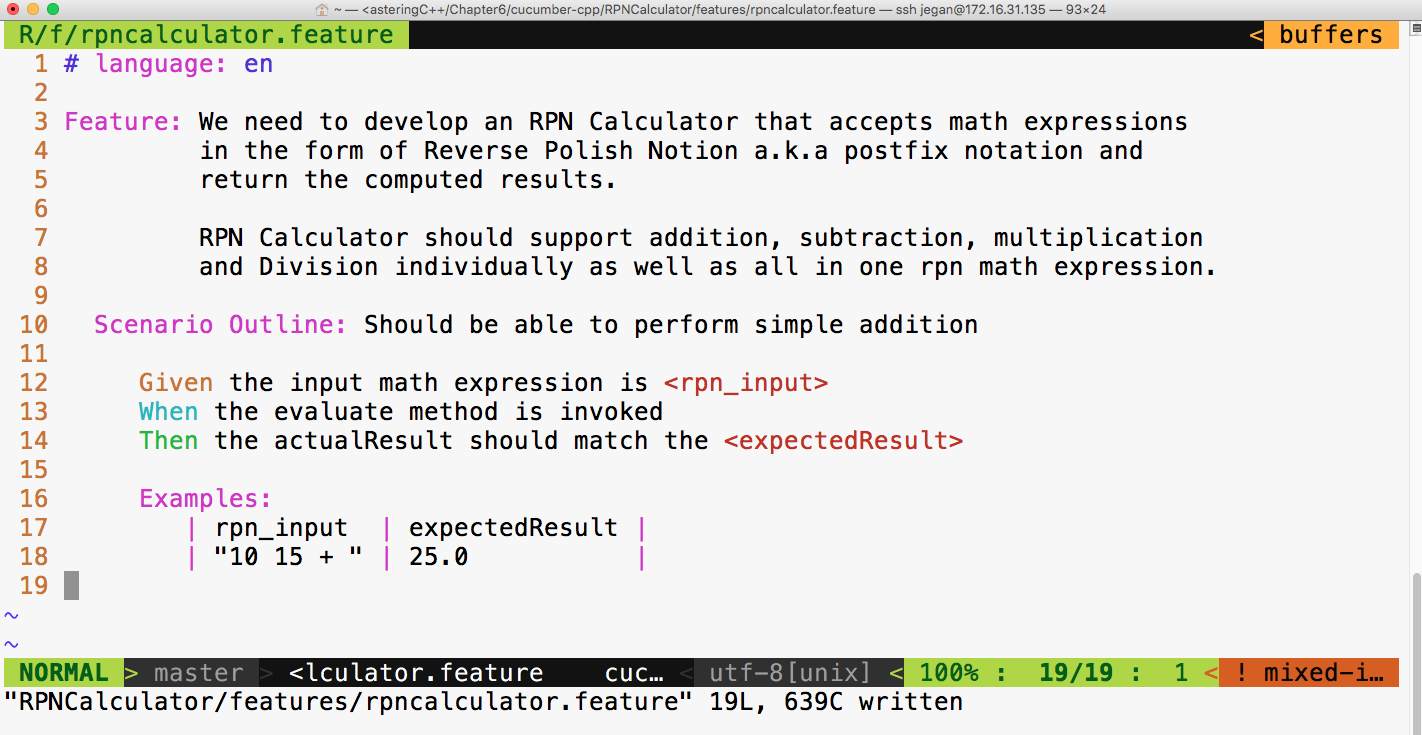

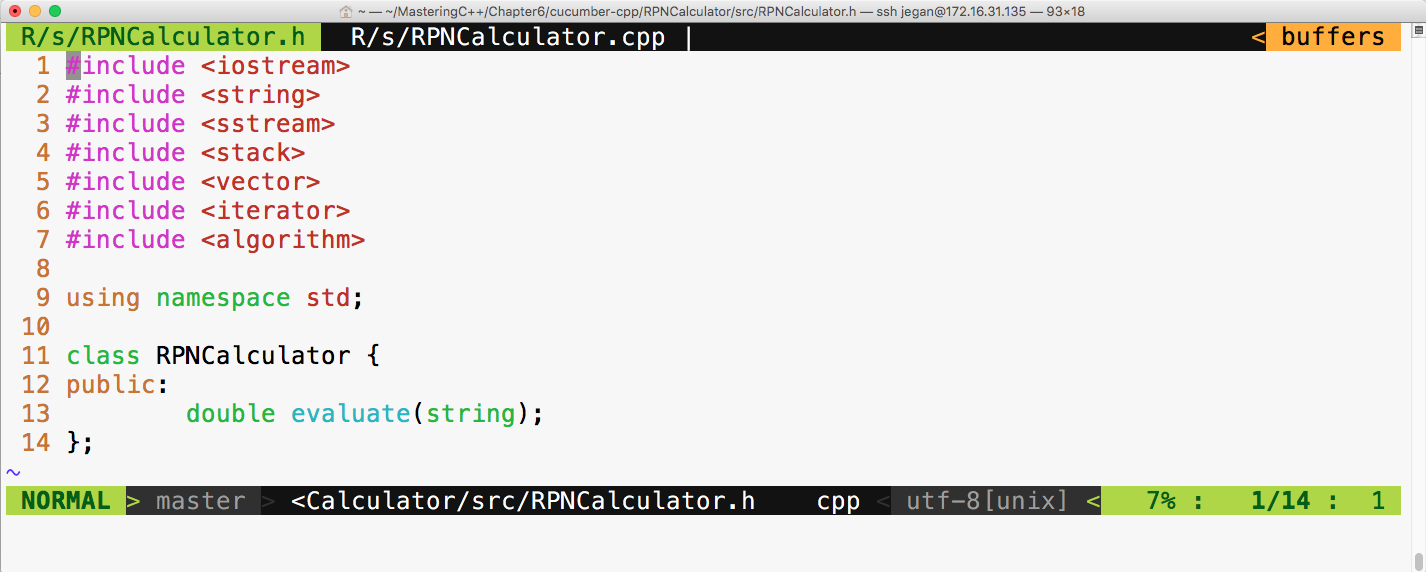

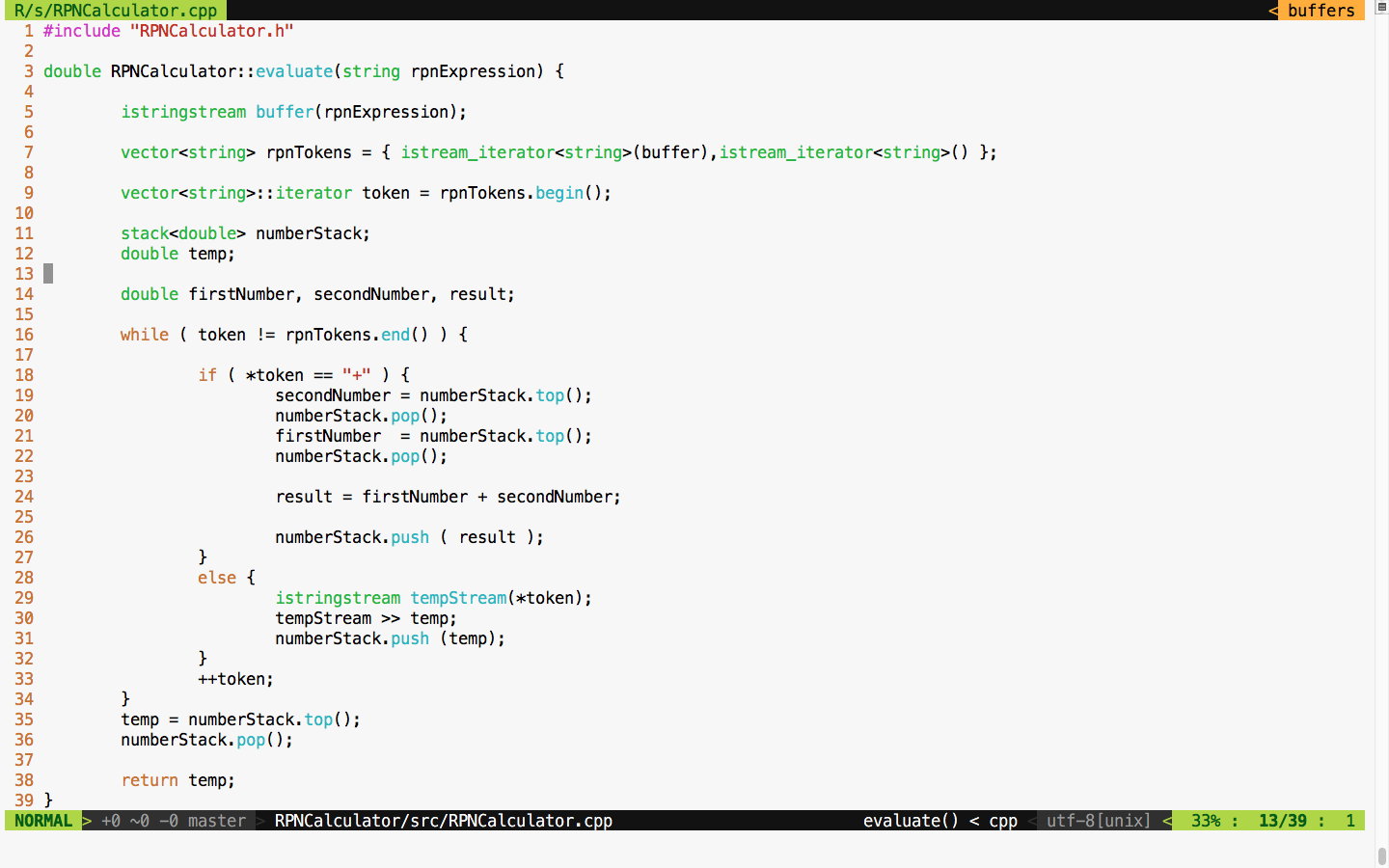

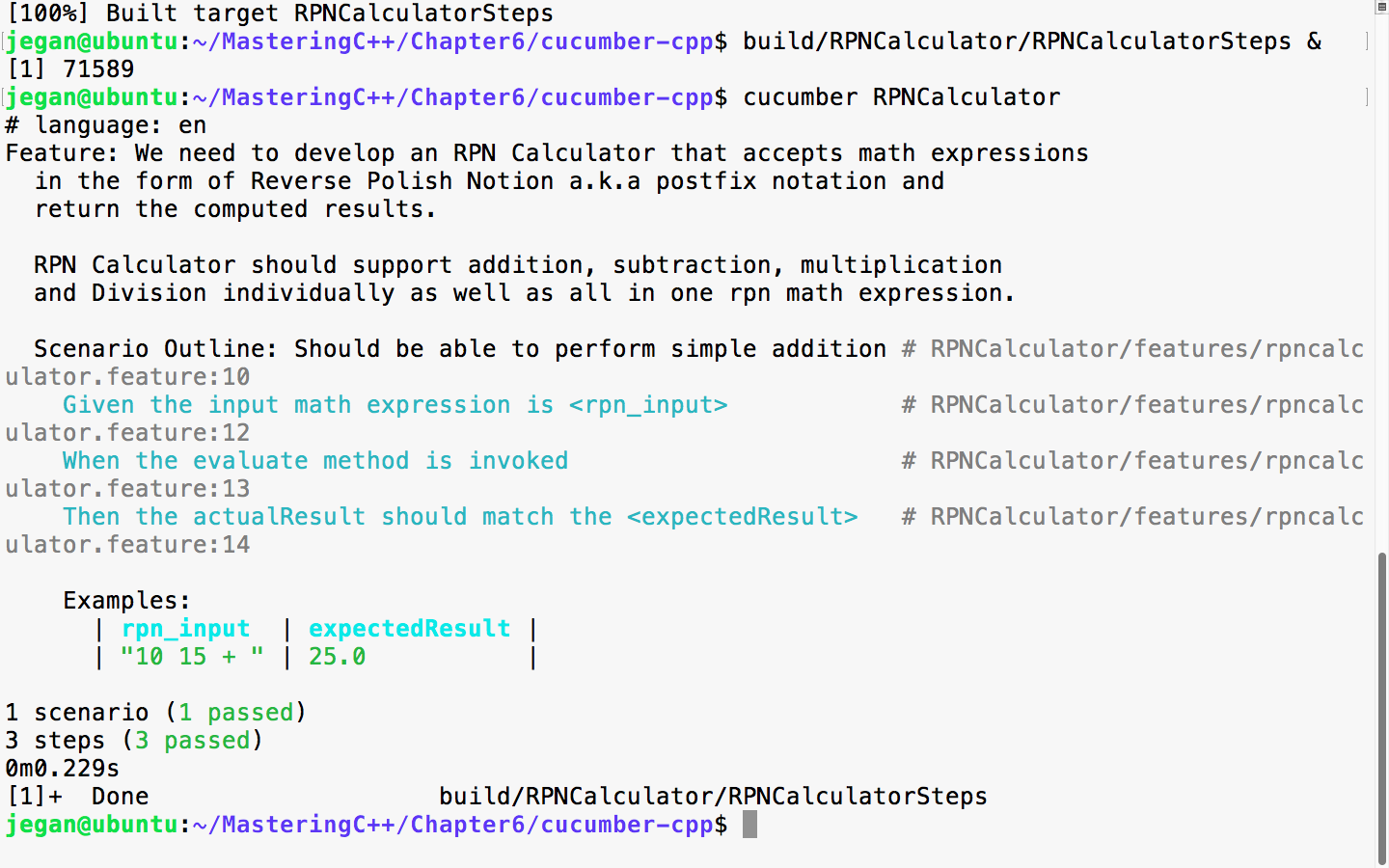

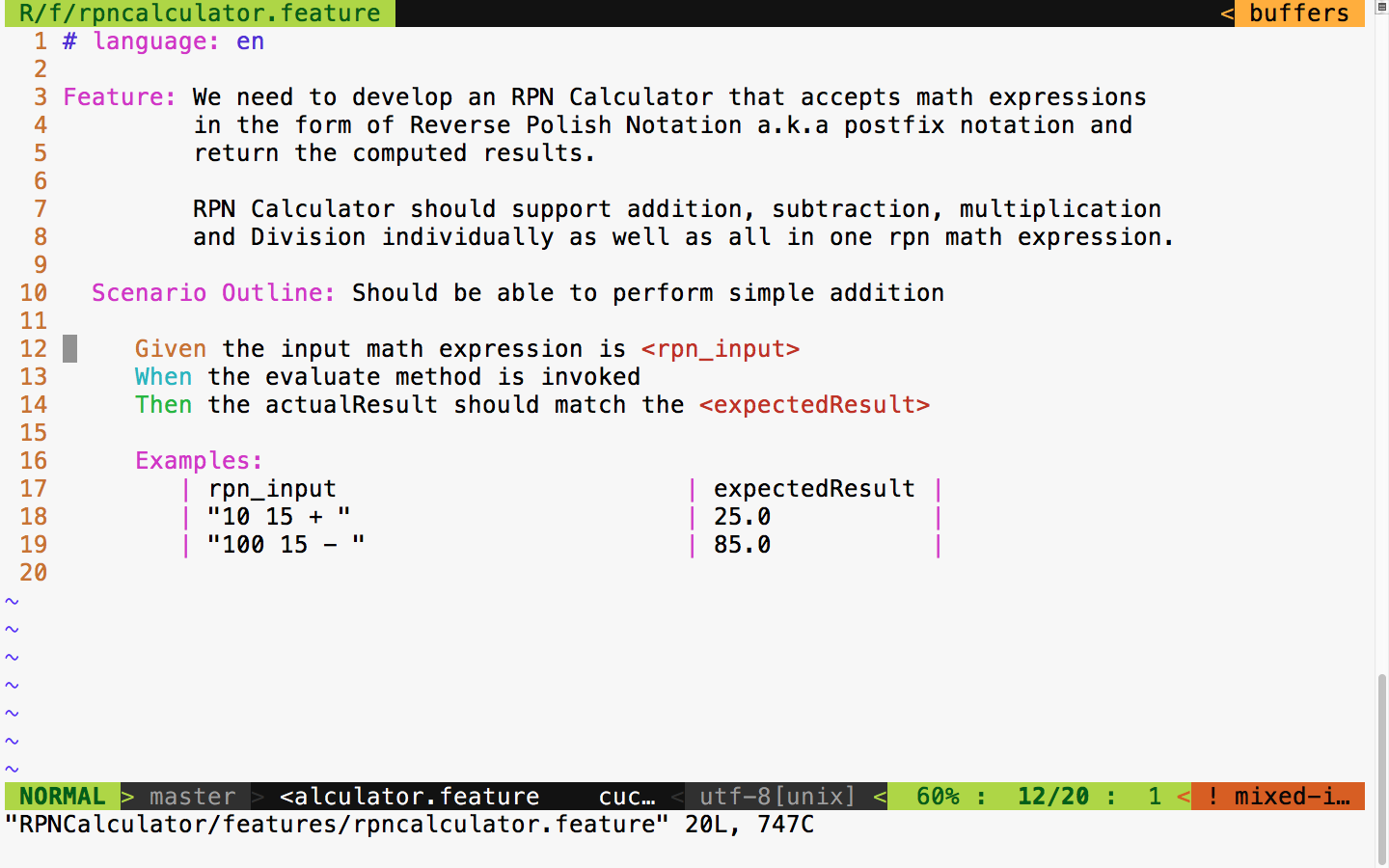

Chapter 8, Behavior-Driven Development, gives an overview of BDD and guides you through the installation, integration, and configuration of the Cucumber framework on Linux platforms. It also explains Gherkin and helps you write BDD test cases.

Chapter 9, Debugging Techniques, discusses the various strategies and techniques followed in the industry for debugging your application problems. Later, it helps you understand the use of the GDB and Valgrind tools for step by step debugging, watching variables, fixing various memory-related issues, including memory leaks.

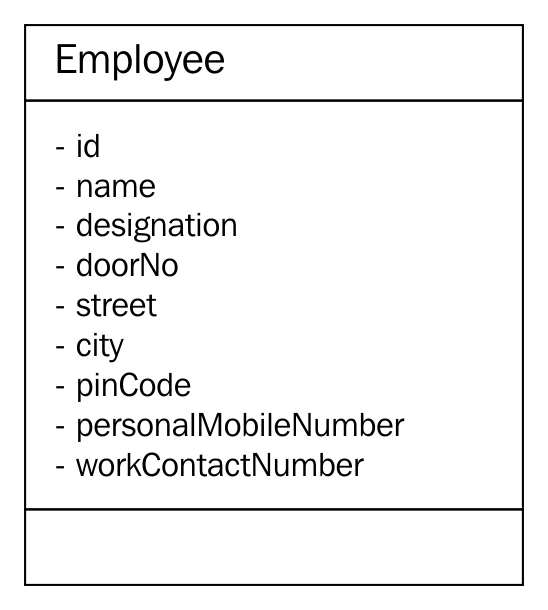

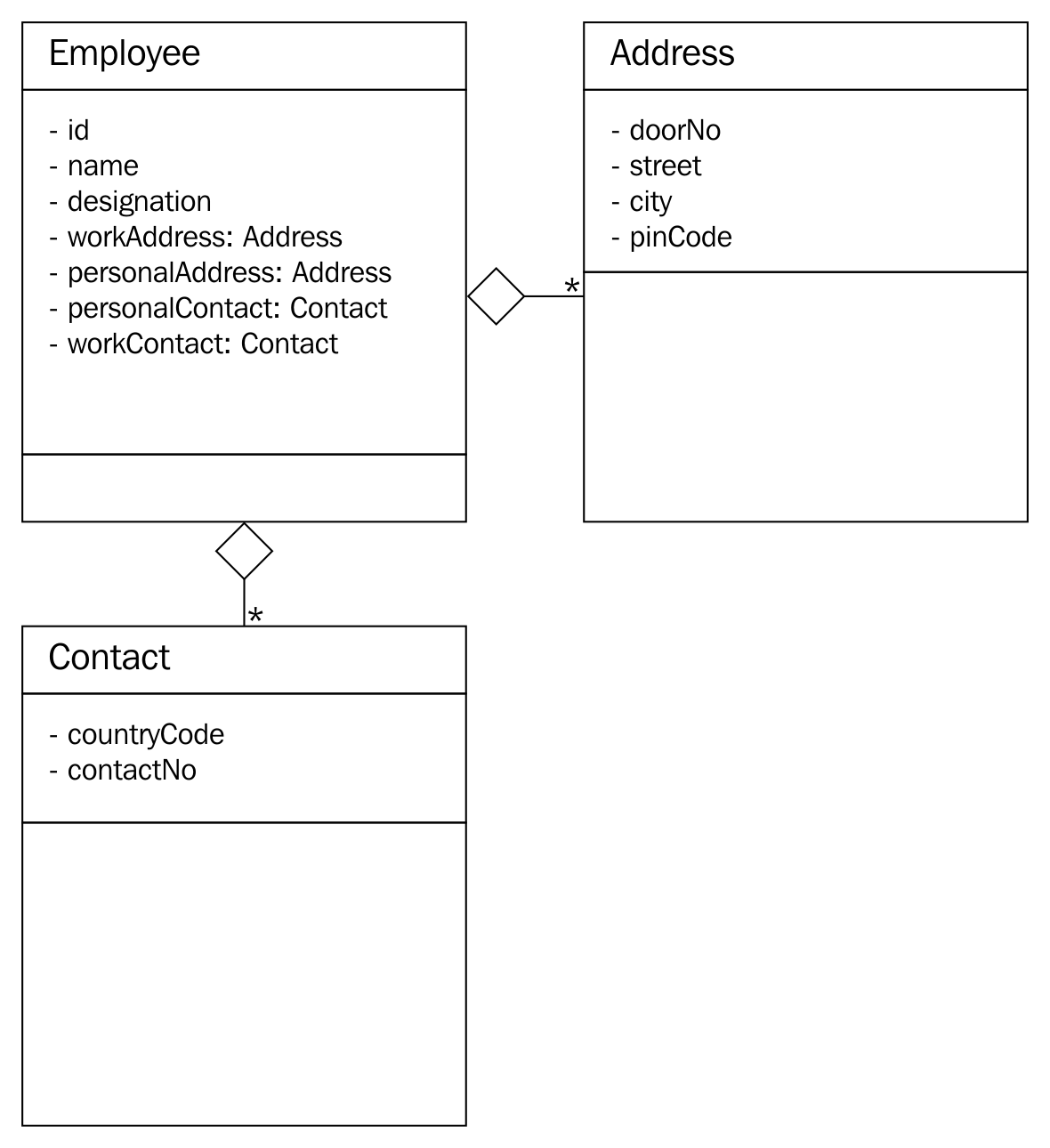

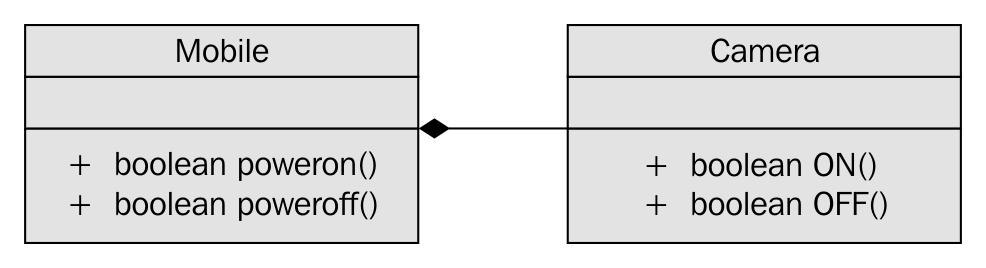

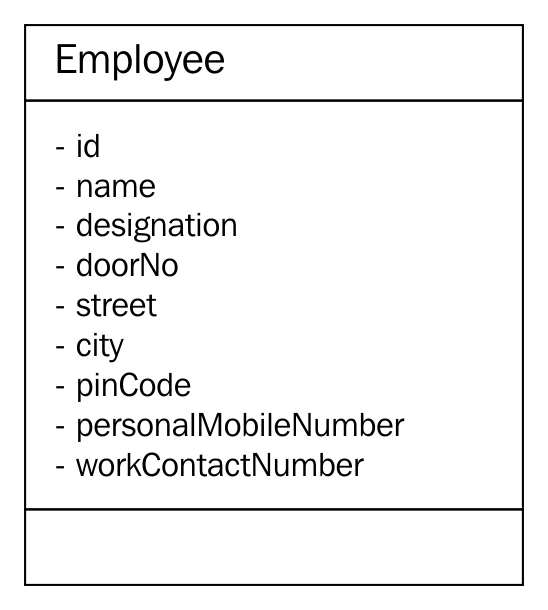

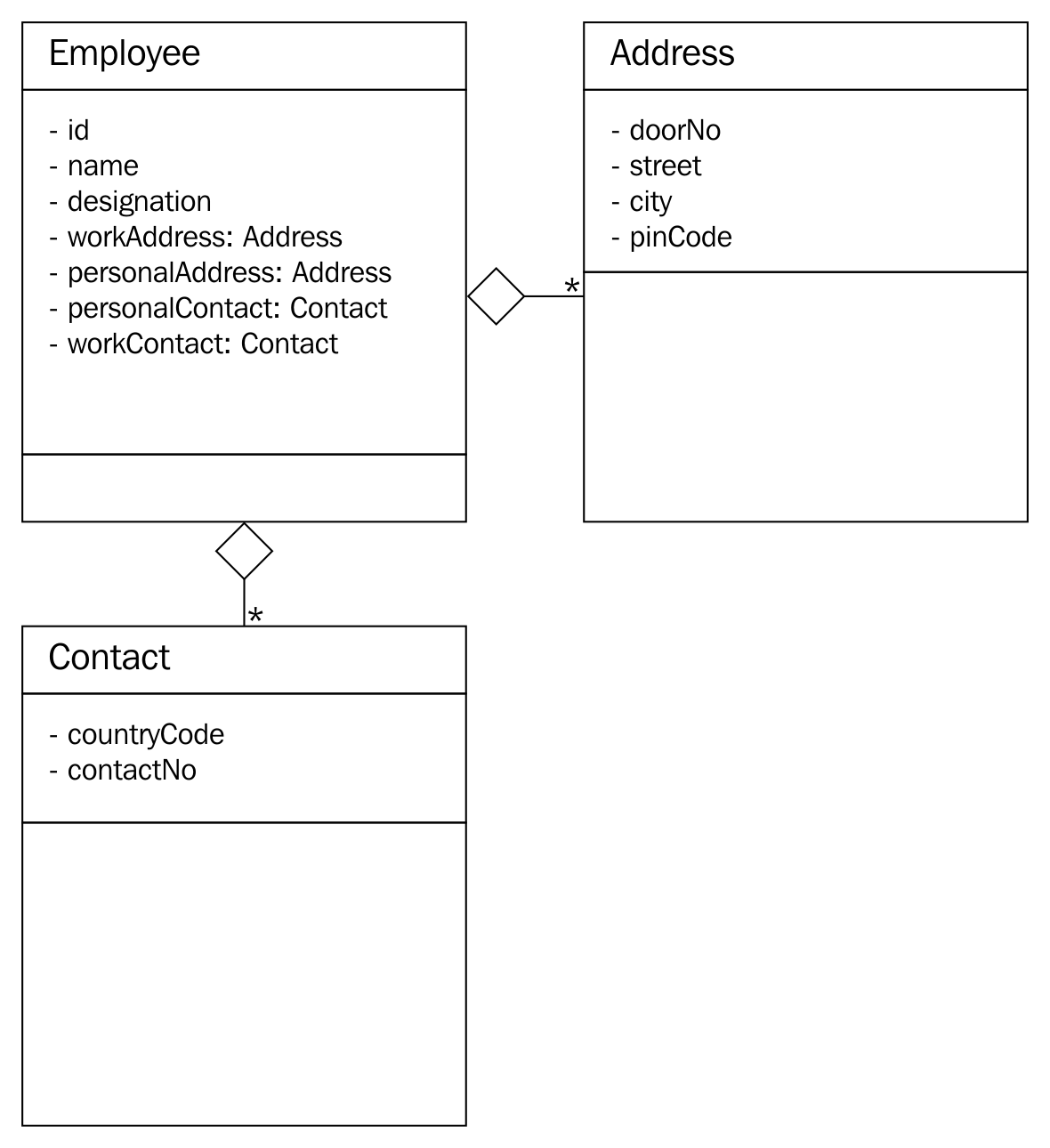

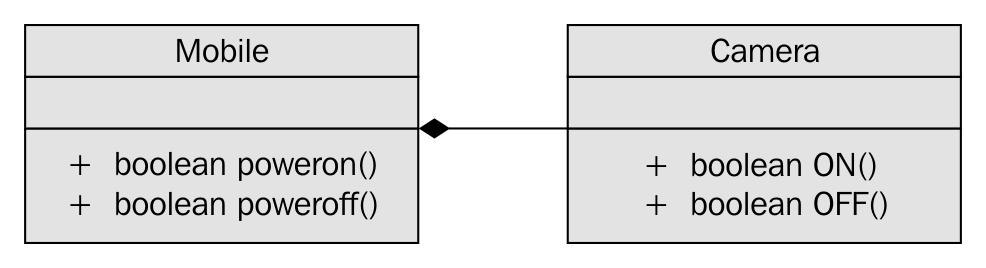

Chapter 10, Code Smells and Clean Code Practices, discusses various code smells and refactoring techniques.

You will need to be equipped with the following tools before you get started with the book:

The OS required is Ubuntu 16.04 64-bit or later. The hardware configuration should at least be of 1 GB RAM and 20 GB ROM. A virtual machine with this configuration should also suffice.

This book is for experienced C++ developers. If you are a novice C++ developer, then it’s highly recommended that you get a solid understanding of the C++ language before reading this book.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning. Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles are shown as follows: "The initialize() method initializes the deque iterator pos to the first data element stored within deque."

A block of code is set as follows:

#include <iostream>

int main ( ) {

const int x = 5, y = 5;

static_assert ( 1 == 0, "Assertion failed" );

static_assert ( 1 == 0 );

static_assert ( x == y );

return 0;

}

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

#include "Account.h"

using namespace std;

enum ThreadType {

DEPOSITOR,

WITHDRAWER

};

mutex locker;

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

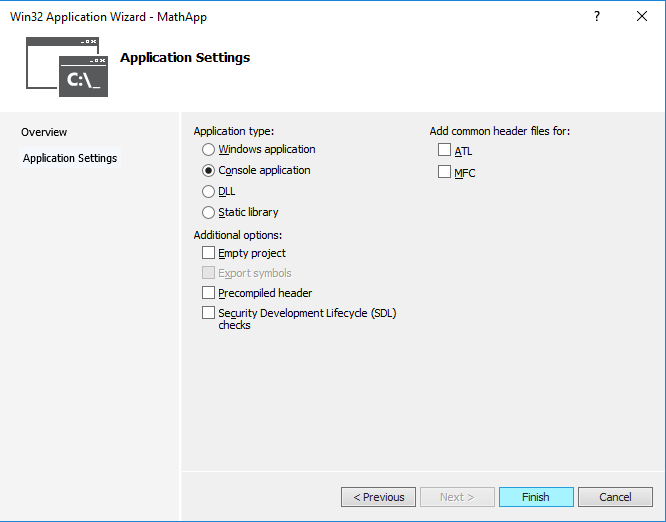

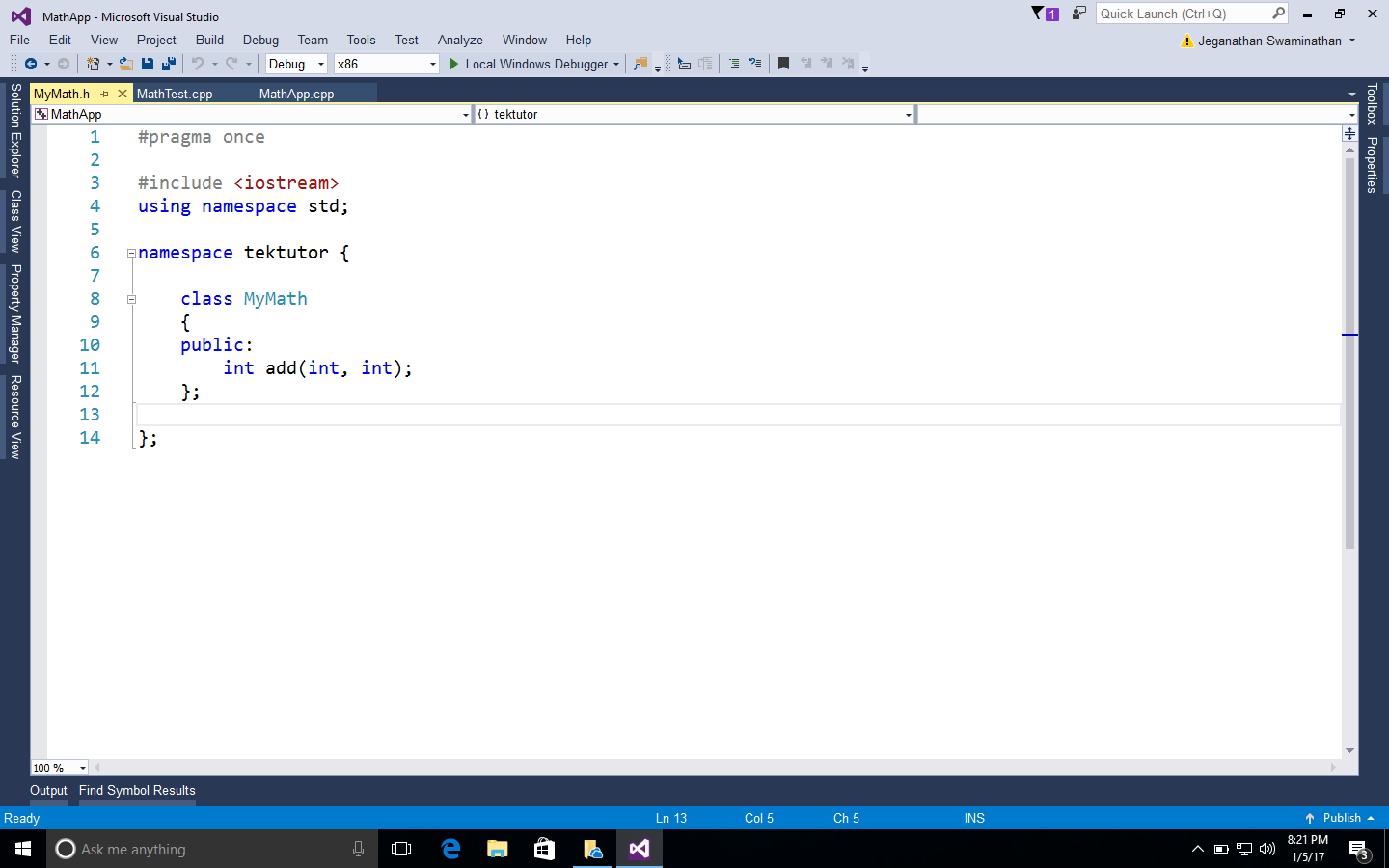

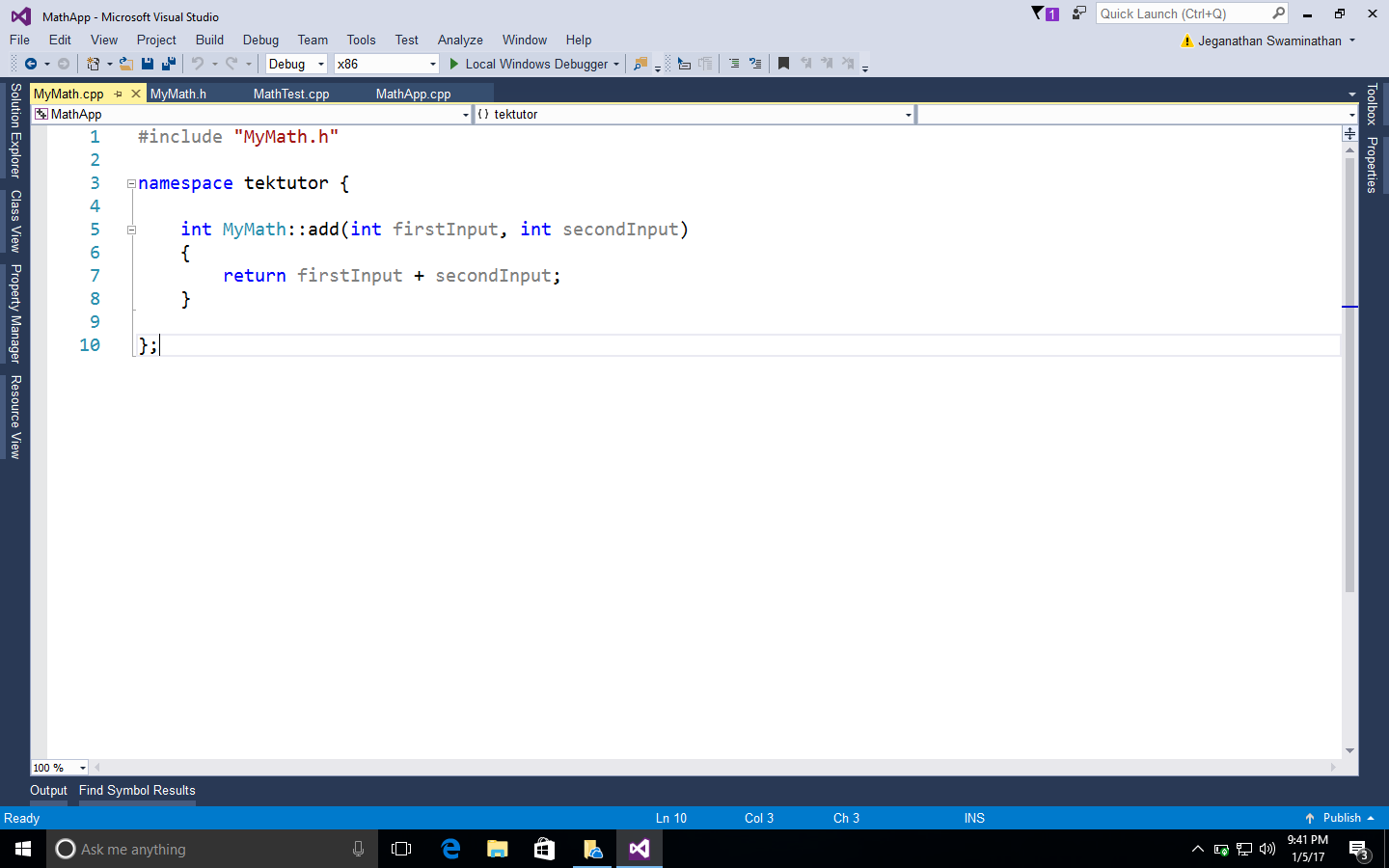

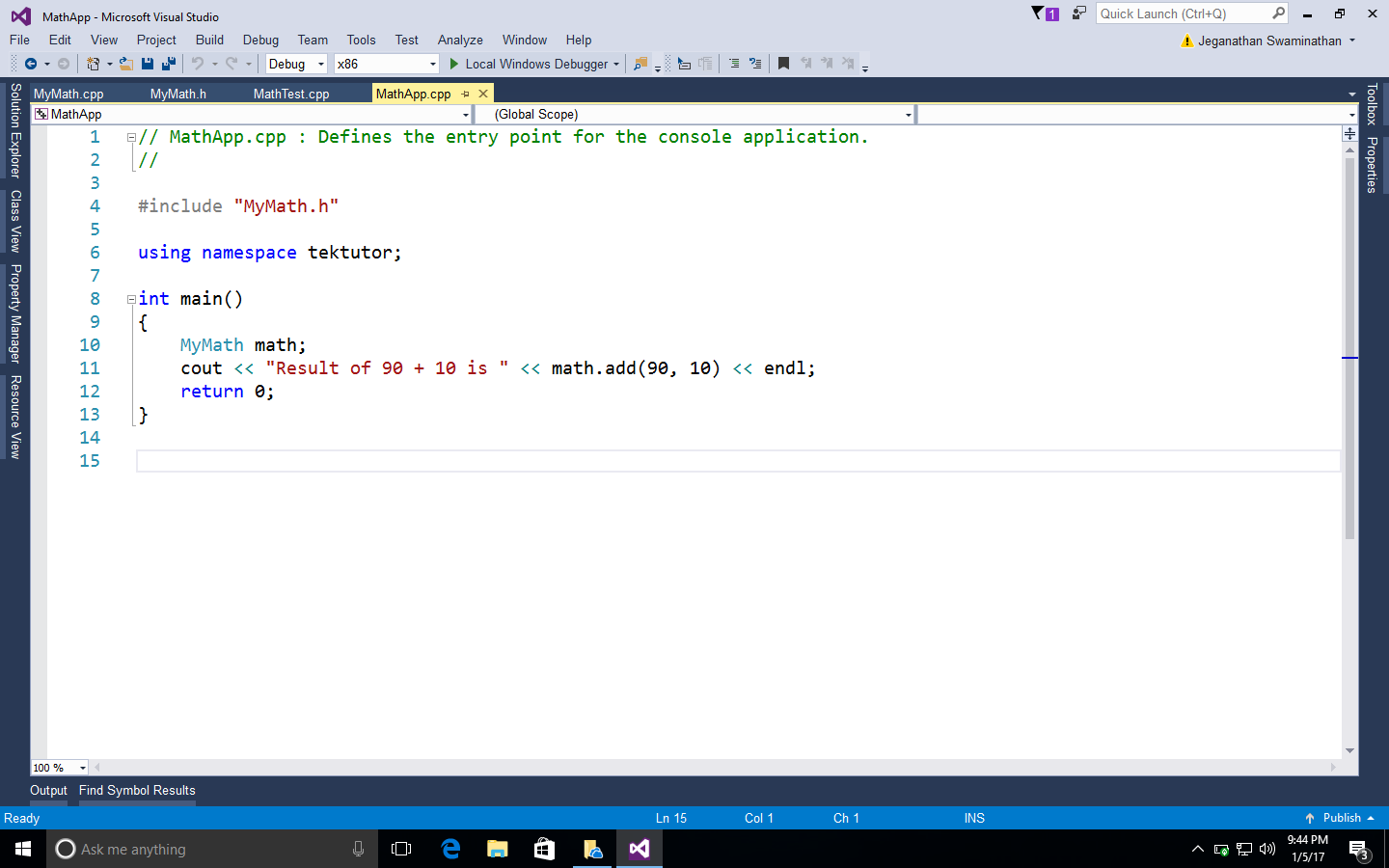

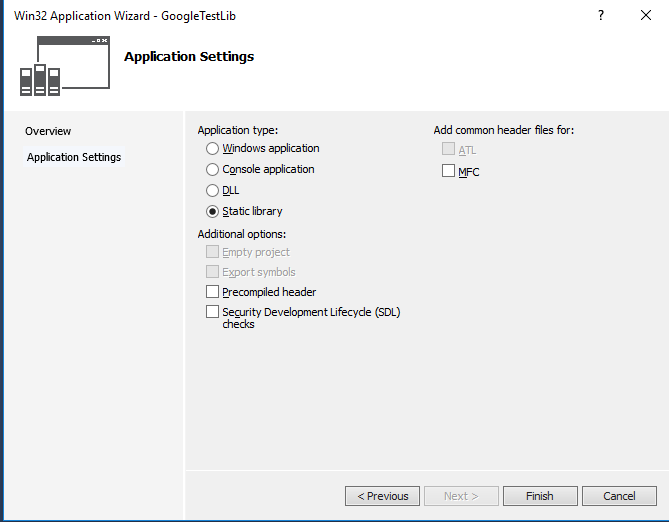

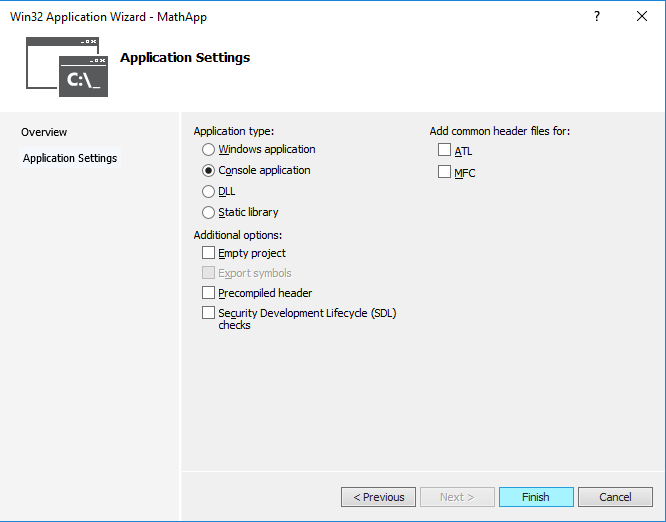

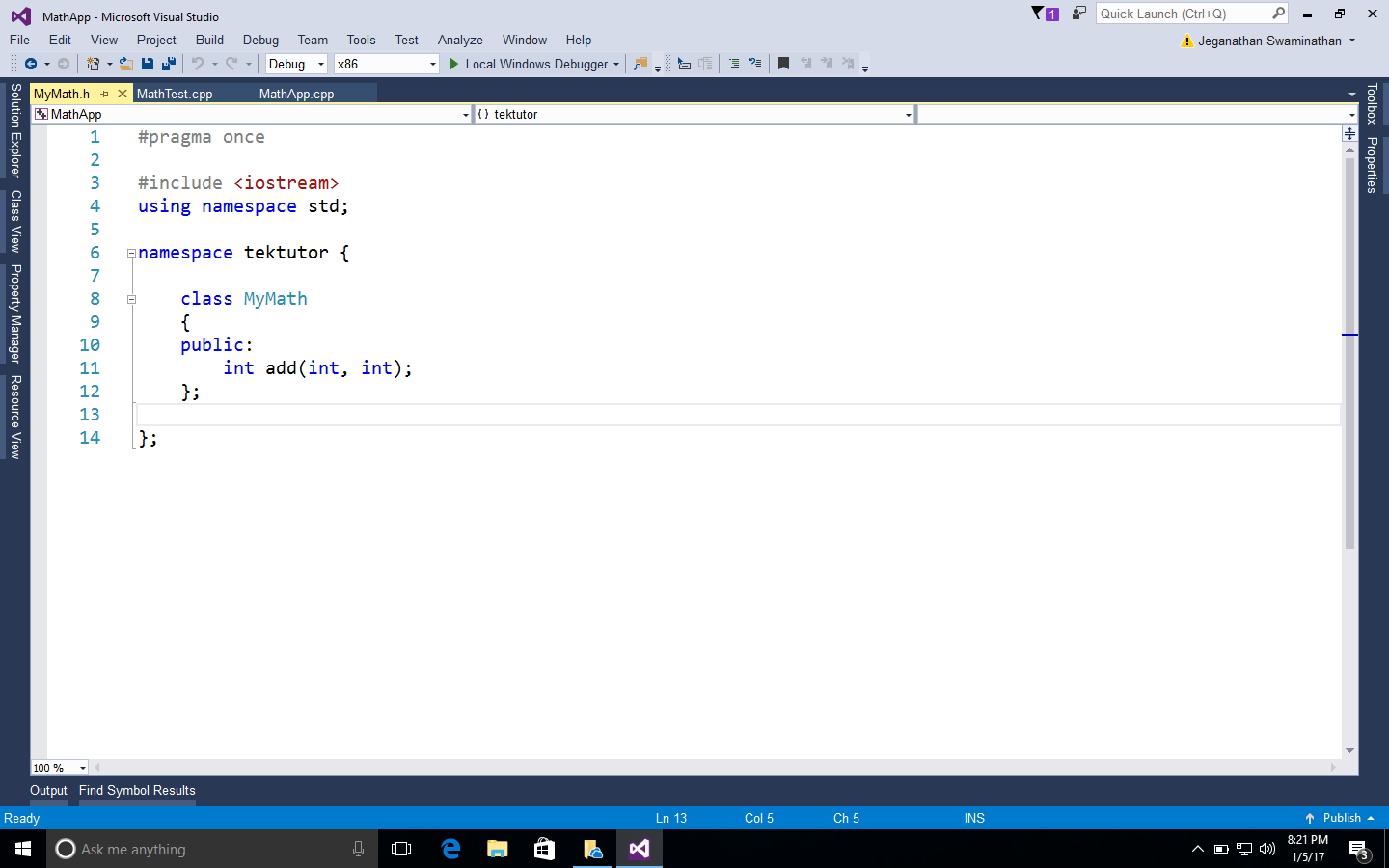

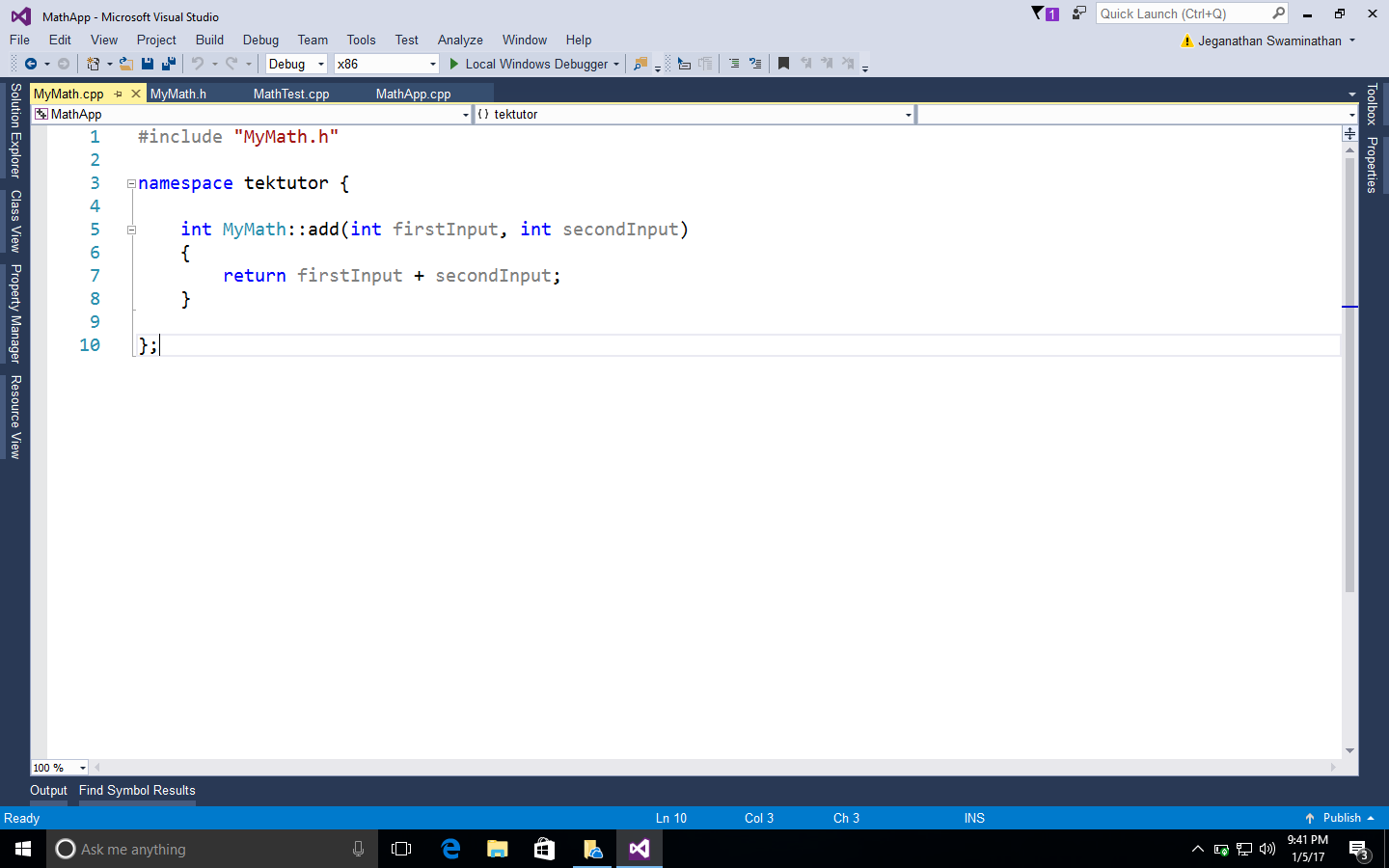

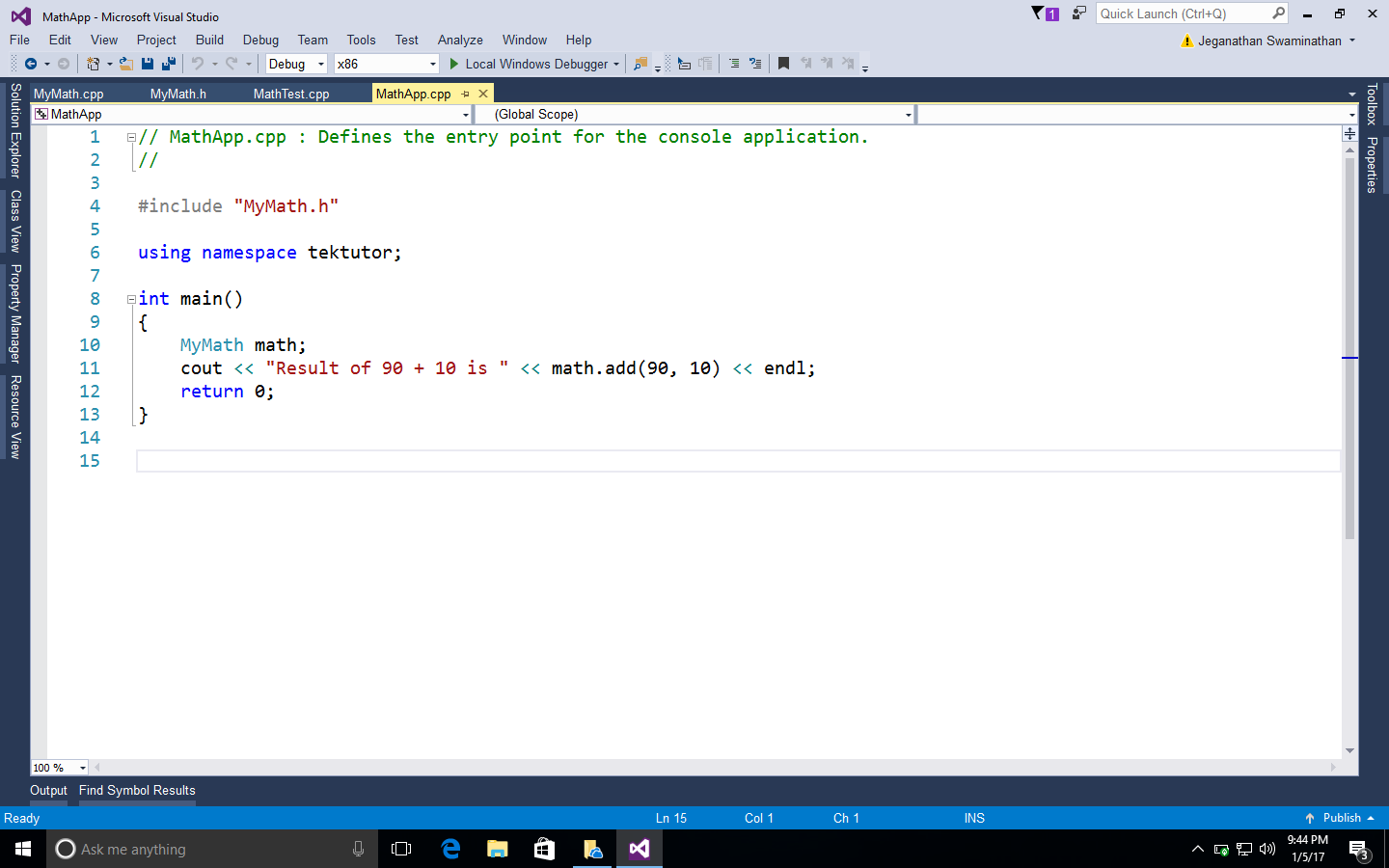

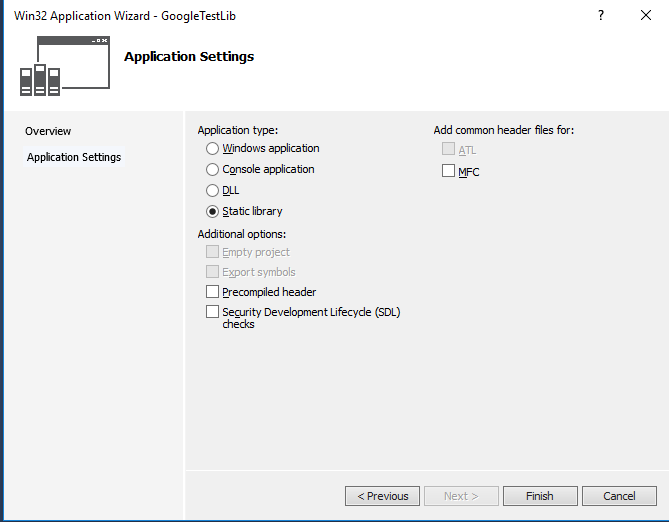

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, for example, in menus or dialog boxes, appear in the text like this: " You need to create a new project named MathApp by navigating to New Project | Visual Studio | Windows | Win32 | Win32 Console Application."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book-what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of. To send us general feedback, simply email feedback@packtpub.com, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message. If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you. You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Mastering-Cpp-Programming. We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books-maybe a mistake in the text or the code-we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title. To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the suspected pirated material. We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at questions@packtpub.com, and we will do our best to address the problem.

In this chapter, you will be learning the following concepts:

As you know, the C++ language is the brain child of Bjarne Stroustrup, who developed C++ in 1979. The C++ programming language is standardized by International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

The initial standardization was published in 1998, commonly referred to as C++98, and the next standardization C++03 was published in 2003, which was primarily a bug fix release with just one language feature for value initialization. In August 2011, the C++11 standard was published with several additions to the core language, including several significant interesting changes to the Standard Template Library (STL); C++11 basically replaced the C++03 standard. C++14 was published in December, 2014 with some new features, and later, the C++17 standard was published on July 31, 2017.

At the time of writing this book, C++17 is the latest revision of the ISO/IEC standard for the C++ programming language.

This chapter requires a compiler that supports C++17 features: gcc version 7 or later. As gcc version 7 is the latest version at the time of writing this book, I'll be using gcc version 7.1.0 in this chapter.

The complete list of C++17 features can be found at http://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/compiler_support#C.2B.2B17_features.

To give a high-level idea, the following are some of the new C++17 features:

Otherwise, there are many new interesting features that were added to the core C++ language: STL, lambadas, and so on. The new features give a facelift to C++, and starting from C++17, as a C++ developer, you will feel that you are working in a modern programming language, such as Java or C#.

The following features are now removed in C++17:

Let's explore the following C++17 key features one by one in the following sections:

Until the C++14 standard, the syntax supported for a nested namespace in C++ was as follows:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace org {

namespace tektutor {

namespace application {

namespace internals {

int x;

}

}

}

}

int main ( ) {

org::tektutor::application::internals::x = 100;

cout << "\nValue of x is " << org::tektutor::application::internals::x << endl;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

Value of x is 100

Every namespace level starts and ends with curly brackets, which makes it difficult to use nested namespaces in large applications. C++17 nested namespace syntax is really cool; just take a look at the following code and you will readily agree with me:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

namespace org::tektutor::application::internals {

int x;

}

int main ( ) {

org::tektutor::application::internals::x = 100;

cout << "\nValue of x is " << org::tektutor::application::internals::x << endl;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output remains the same as the previous program:

Value of x is 100

C++17 introduced new rules for auto-detection of the initializer list, which complements C++14 rules. The C++17 rule insists that the program is ill-formed if an explicit or partial specialization of std::initializer_list is declared:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <typename T1, typename T2>

class MyClass {

private:

T1 t1;

T2 t2;

public:

MyClass( T1 t1 = T1(), T2 t2 = T2() ) { }

void printSizeOfDataTypes() {

cout << "\nSize of t1 is " << sizeof ( t1 ) << " bytes." << endl;

cout << "\nSize of t2 is " << sizeof ( t2 ) << " bytes." << endl;

}

};

int main ( ) {

//Until C++14

MyClass<int, double> obj1;

obj1.printSizeOfDataTypes( );

//New syntax in C++17

MyClass obj2( 1, 10.56 );

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

Values in integer vectors are ...

1 2 3 4 5

Values in double vectors are ...

1.5 2.5 3.5

The static_assert macro helps identify assert failures during compile time. This feature has been supported since C++11; however, the static_assert macro used to take a mandatory assertion failure message till, which is now made optional in C++17.

The following example demonstrates the use of static_assert with and without the message:

#include <iostream>

#include <type_traits>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

const int x = 5, y = 5;

static_assert ( 1 == 0, "Assertion failed" );

static_assert ( 1 == 0 );

static_assert ( x == y );

return 0;

}

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

g++-7 staticassert.cpp -std=c++17

staticassert.cpp: In function ‘int main()’:

staticassert.cpp:7:2: error: static assertion failed: Assertion failed

static_assert ( 1 == 0, "Assertion failed" );

staticassert.cpp:8:2: error: static assertion failed

static_assert ( 1 == 0 );

From the preceding output, you can see that the message, Assertion failed, appears as part of the compilation error, while in the second compilation the default compiler error message appears, as we didn't supply an assertion failure message. When there is no assertion failure, the assertion error message will not appear as demonstrated in static_assert ( x == y ). This feature is inspired by the C++ community from the BOOST C++ library.

The std::invoke() method can be used to call functions, function pointers, and member pointers with the same syntax:

#include <iostream>

#include <functional>

using namespace std;

void globalFunction( ) {

cout << "globalFunction ..." << endl;

}

class MyClass {

public:

void memberFunction ( int data ) {

std::cout << "\nMyClass memberFunction ..." << std::endl;

}

static void staticFunction ( int data ) {

std::cout << "MyClass staticFunction ..." << std::endl;

}

};

int main ( ) {

MyClass obj;

std::invoke ( &MyClass::memberFunction, obj, 100 );

std::invoke ( &MyClass::staticFunction, 200 );

std::invoke ( globalFunction );

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

MyClass memberFunction ...

MyClass staticFunction ...

globalFunction ...

The std::invoke( ) method is a template function that helps you seamlessly invoke callable objects, both built-in and user-defined.

You can now initialize multiple variables with a return value with a really cool syntax, as shown in the following code sample:

#include <iostream>

#include <tuple>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

tuple<string,int> student("Sriram", 10);

auto [name, age] = student;

cout << "\nName of the student is " << name << endl;

cout << "Age of the student is " << age << endl;

return 0;

}

In the preceding program, the code highlighted in bold is the structured binding feature introduced in C++17. Interestingly, we have not declared the string name and int age variables. These are deduced automatically by the C++ compiler as string and int, which makes the C++ syntax just like any modern programming language, without losing its performance and system programming benefits.

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

Name of the student is Sriram

Age of the student is 10

There is an interesting new feature that allows you to declare a local variable bound to the if and switch statements' block of code. The scope of the variable used in the if and switch statements will go out of scope outside the respective blocks. It can be better understood with an easy to understand example, as follows:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

bool isGoodToProceed( ) {

return true;

}

bool isGood( ) {

return true;

}

void functionWithSwitchStatement( ) {

switch ( auto status = isGood( ) ) {

case true:

cout << "\nAll good!" << endl;

break;

case false:

cout << "\nSomething gone bad" << endl;

break;

}

}

int main ( ) {

if ( auto flag = isGoodToProceed( ) ) {

cout << "flag is a local variable and it loses its scope outside the if block" << endl;

}

functionWithSwitchStatement();

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding program is as follows:

flag is a local variable and it loses its scope outside the if block

All good!

I'm sure you will love what you are about to see in the sample code. Though templates are quite useful, a lot of people don't like it due to its tough and weird syntax. But you don't have to worry anymore; take a look at the following code snippet:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <typename T1, typename T2>

class MyClass {

private:

T1 t1;

T2 t2;

public:

MyClass( T1 t1 = T1(), T2 t2 = T2() ) { }

void printSizeOfDataTypes() {

cout << "\nSize of t1 is " << sizeof ( t1 ) << " bytes." << endl;

cout << "\nSize of t2 is " << sizeof ( t2 ) << " bytes." << endl;

}

};

int main ( ) {

//Until C++14

MyClass<int, double> obj1;

obj1.printSizeOfDataTypes( );

//New syntax in C++17

MyClass obj2( 1, 10.56 );

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Size of t1 is 4 bytes.

Size of t2 is 8 bytes.

Just like the inline function in C++, you could now use inline variable definitions. This comes in handy to initialize static variables, as shown in the following sample code:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class MyClass {

private:

static inline int count = 0;

public:

MyClass() {

++count;

}

public:

void printCount( ) {

cout << "\nCount value is " << count << endl;

}

};

int main ( ) {

MyClass obj;

obj.printCount( ) ;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++-7 main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the preceding code is as follows:

Count value is 1

In this chapter, you got to know interesting new features introduced in C++17. You learned the super simple C++17 nested namespace syntax. You also learned datatype detection with a braced initializer list and the new rule imposed in the C++17 standard.

You also noticed that static_assert can be done without assert failure messages. Also, using std::invoke(), you can now invoke global functions, function pointers, member functions, and static class member functions. And, using structured binding, you could now initialize multiple variables with a return value.

You also learned that the if and switch statements can have a local-scoped variable right before the if condition and switch statements. You learned about auto type detection of class templates. Lastly, you used inline variables.

There are many more C++17 features, but this chapter attempts to cover the most useful features that might be required for most of the developers. In the next chapter, you will be learning about the Standard Template Library.

This chapter will cover the following topics:

Let's look into the STL topics one by one in the following sections.

The C++ Standard Template Library (STL) offers ready-made generic containers, algorithms that can be applied to the containers, and iterators to navigate the containers. The STL is implemented with C++ templates, and templates allow generic programming in C++.

The STL encourages a C++ developer to focus on the task at hand by freeing up the developer from writing low-level data structures and algorithms. The STL is a time-tested library that allows rapid application development.

The STL is an interesting piece of work and architecture. Its secret formula is compile-time polymorphism. To get better performance, the STL avoids dynamic polymorphism, saying goodbye to virtual functions. Broadly, the STL has the following four components:

The STL architecture stitches all the aforementioned four components together. It has many commonly used algorithms with performance guarantees. The interesting part about STL algorithms is that they work seamlessly without any knowledge about the containers that hold the data. This is made possible due to the iterators that offer high-level traversal APIs, which completely abstracts the underlying data structure used within a container. The STL makes use of operator overloading quite extensively. Let's understand the major components of STL one by one to get a good grasp of the STL conceptually.

The STL algorithms are powered by C++ templates; hence, the same algorithm works irrespective of what data type it deals with or independently of how the data is organized by a container. Interestingly, the STL algorithms are generic enough to support built-in and user-defined data types using templates. As a matter of fact, the algorithms interact with the containers via iterators. Hence, what matters to the algorithms is the iterator supported by the container. Having said that, the performance of an algorithm depends on the underlying data structure used within a container. Hence, certain algorithms work only on selective containers, as each algorithm supported by the STL expects a certain type of iterator.

An iterator is a design pattern, but interestingly, the STL work started much before

Gang of Four published their design patterns-related work to the software community. Iterators themselves are objects that allow traversing the containers to access, modify, and manipulate the data stored in the containers. Iterators do this so magically that we don't realize or need to know where and how the data is stored and retrieved.

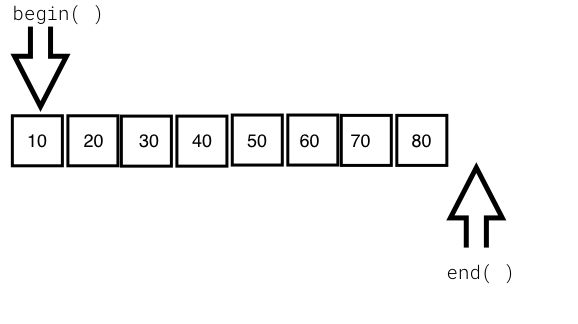

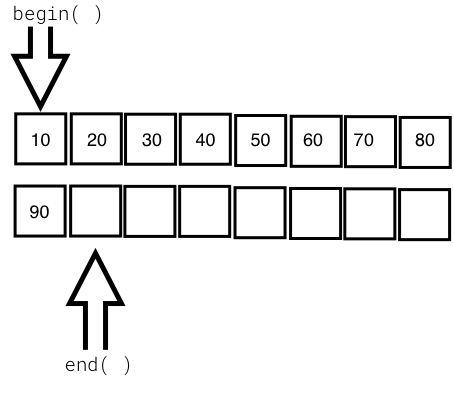

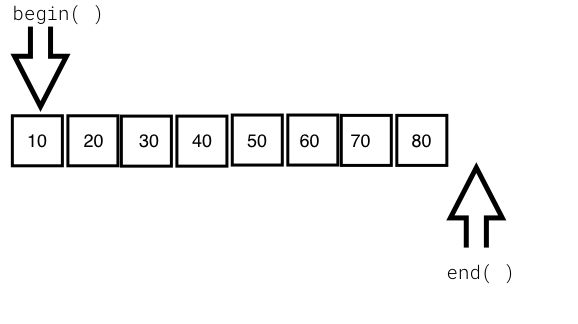

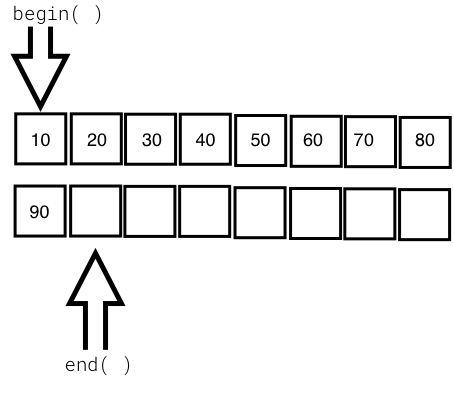

The following image visually represents an iterator:

From the preceding image, you can understand that every iterator supports the begin() API, which returns the first element position, and the end() API returns one position past the last element in the container.

The STL broadly supports the following five types of iterators:

The container implements the iterator to let us easily retrieve and manipulate the data, without delving much into the technical details of a container.

The following table explains each of the five iterators:

|

The type of iterator |

Description |

|

Input iterator |

|

|

Output iterator |

|

|

Forward iterator |

|

|

Bidirectional iterator |

|

|

Random-access iterator |

|

STL containers are objects that typically grow and shrink dynamically. Containers use complex data structures to store the data under the hood and offer high-level functions to access the data without us delving into the complex internal implementation details of the data structure. STL containers are highly efficient and time-tested.

Every container uses different types of data structures to store, organize, and manipulate data in an efficient way. Though many containers may seem similar, they behave differently under the hood. Hence, the wrong choice of containers leads to application performance issues and unnecessary complexities.

Containers come in the following flavors:

The objects stored in the containers are copied or moved, and not referenced. We will explore every type of container in the upcoming sections with simple yet interesting examples.

Functors are objects that behave like regular functions. The beauty is that functors can be substituted in the place of function pointers. Functors are handy objects that let you extend or complement the behavior of an STL function without compromising the object-oriented coding principles.

Functors are easy to implement; all you need to do is overload the function operator. Functors are also referred to as functionoids.

The following code will demonstrate the way a simple functor can be implemented:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

template <typename T>

class Printer {

public:

void operator() ( const T& element ) {

cout << element << "\t";

}

};

int main () {

vector<int> v = { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 };

cout << "\nPrint the vector entries using Functor" << endl;

for_each ( v.begin(), v.end(), Printer<int>() );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

Let's quickly compile the program using the following command:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

Let's check the output of the program:

Print the vector entries using Functor

10 20 30 40 50

We hope you realize how easy and cool a functor is.

The STL supports quite an interesting variety of sequence containers. Sequence containers store homogeneous data types in a linear fashion, which can be accessed sequentially. The STL supports the following sequence containers:

As the objects stored in an STL container are nothing but copies of the values, the STL expects certain basic requirements from the user-defined data types in order to hold those objects inside a container. Every object stored in an STL container must provide the following as a minimum requirement:

Let's explore the sequence containers one by one in the following subsections.

The STL array container is a fixed-size sequence container, just like a C/C++ built-in array, except that the STL array is size-aware and a bit smarter than the built-in C/C++ array. Let's understand an STL array with an example:

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

using namespace std;

int main () {

array<int,5> a = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

cout << "\nSize of array is " << a.size() << endl;

auto pos = a.begin();

cout << endl;

while ( pos != a.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "\t";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Size of array is 5

1 5 2 4 3

The following line declares an array of a fixed size (5) and initializes the array with five elements:

array<int,5> a = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

The size mentioned can't be changed once declared, just like a C/C++ built-in array. The array::size() method returns the size of the array, irrespective of how many integers are initialized in the initializer list. The auto pos = a.begin() method declares an iterator of array<int,5> and assigns the starting position of the array. The array::end() method points to one position after the last element in the array. The iterator behaves like or mimics a C++ pointer, and dereferencing the iterator returns the value pointed by the iterator. The iterator position can be moved forward and backwards with ++pos and --pos, respectively.

The following table shows some commonly used array APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at( int index ) |

This returns the value stored at the position referred to by the index. The index is a zero-based index. This API will throw an std::out_of_range exception if the index is outside the index range of the array. |

|

operator [ int index ] |

This is an unsafe method, as it won't throw any exception if the index falls outside the valid range of the array. This tends to be slightly faster than at, as this API doesn't perform bounds checking. |

|

front() |

This returns the first element in the array. |

|

back() |

This returns the last element in the array. |

|

begin() |

This returns the position of the first element in the array |

|

end() |

This returns one position past the last element in the array |

|

rbegin() |

This returns the reverse beginning position, that is, it returns the position of the last element in the array |

|

rend() |

This returns the reverse end position, that is, it returns one position before the first element in the array |

|

size() |

This returns the size of the array |

The array container supports random access; hence, given an index, the array container can fetch a value with a runtime complexity of O(1) or constant time.

The array container elements can be accessed in a reverse fashion using the reverse iterator:

#include <iostream>

#include <array>

using namespace std;

int main () {

array<int, 6> a;

int size = a.size();

for (int index=0; index < size; ++index)

a[index] = (index+1) * 100;

cout << "\nPrint values in original order ..." << endl;

auto pos = a.begin();

while ( pos != a.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "\t";

cout << endl;

cout << "\nPrint values in reverse order ..." << endl;

auto rpos = a.rbegin();

while ( rpos != a.rend() )

cout << *rpos++ << "\t";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

We will use the following command to get the output:

./a.out

The output is as follows:

Print values in original order ...

100 200 300 400 500 600

Print values in reverse order ...

600 500 400 300 200 100

Vector is a quite useful sequence container, and it works exactly as an array, except that the vector can grow and shrink at runtime while an array is of a fixed size. However, the data structure used under the hood in an array and vector is a plain simple built-in C/C++ style array.

Let's look at the following example to understand vectors better:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

vector<int> v = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

cout << "\nSize of vector is " << v.size() << endl;

auto pos = v.begin();

cout << "\nPrint vector elements before sorting" << endl;

while ( pos != v.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "\t";

cout << endl;

sort( v.begin(), v.end() );

pos = v.begin();

cout << "\nPrint vector elements after sorting" << endl;

while ( pos != v.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "\t";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The preceding code can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Size of vector is 5

Print vector elements before sorting

1 5 2 4 3

Print vector elements after sorting

1 2 3 4 5

The following line declares a vector and initializes the vector with five elements:

vector<int> v = { 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 };

However, a vector also allows appending values to the end of the vector by using the vector::push_back<data_type>( value ) API. The sort() algorithm takes two random access iterators that represent a range of data that must be sorted. As the vector internally uses a built-in C/C++ array, just like the STL array container, a vector also supports random access iterators; hence the sort() function is a highly efficient algorithm whose runtime complexity is logarithmic, that is, O(N log2 (N)).

The following table shows some commonly used vector APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at ( int index ) |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It throws the std::out_of_range exception if the index is invalid. |

|

operator [ int index ] |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It is faster than at( int index ), since no bounds checking is performed by this function. |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the vector. |

|

back() |

This returns the last value stored in the vector. |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the vector is empty, and false otherwise. |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the vector. |

|

reserve( int size ) |

This reserves the initial size of the vector. When the vector size has reached its capacity, an attempt to insert new values requires vector resizing. This makes the insertion consume O(N) runtime complexity. The reserve() method is a workaround for the issue described. |

|

capacity() |

This returns the total capacity of the vector, while the size is the actual value stored in the vector. |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values. |

|

push_back<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a new value at the end of the vector. |

It would be really fun and convenient to read and print to/from the vector using istream_iterator and ostream_iterator. The following code demonstrates the use of a vector:

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

int main () {

vector<int> v;

cout << "\nType empty string to end the input once you are done feeding the vector" << endl;

cout << "\nEnter some numbers to feed the vector ..." << endl;

istream_iterator<int> start_input(cin);

istream_iterator<int> end_input;

copy ( start_input, end_input, back_inserter( v ) );

cout << "\nPrint the vector ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

Basically, the copy algorithm accepts a range of iterators, where the first two arguments represent the source and the third argument represents the destination, which happens to be the vector:

istream_iterator<int> start_input(cin);

istream_iterator<int> end_input;

copy ( start_input, end_input, back_inserter( v ) );

The start_input iterator instance defines an istream_iterator iterator that receives input from istream and cin, and the end_input iterator instance defines an end-of-file delimiter, which is an empty string by default (""). Hence, the input can be terminated by typing "" in the command-line input terminal.

Similarly, let's understand the following code snippet:

cout << "\nPrint the vector ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

The copy algorithm is used to copy the values from a vector, one element at a time, to ostream, separating the output with a tab character (\t).

Every STL container has its own advantages and disadvantages. There is no single STL container that works better in all the scenarios. A vector internally uses an array data structure, and arrays are fixed in size in C/C++. Hence, when you attempt to add new values to the vector at the time the vector size has already reached its maximum capacity, then the vector will allocate new consecutive locations that can accommodate the old values and the new value in a contiguous location. It then starts copying the old values into the new locations. Once all the data elements are copied, the vector will invalidate the old location.

Whenever this happens, the vector insertion will take O(N) runtime complexity. As the size of the vector grows over time, on demand, the O(N) runtime complexity will show up a pretty bad performance. If you know the maximum size required, you could reserve so much initial size upfront in order to overcome this issue. However, not in all scenarios do you need to use a vector. Of course, a vector supports dynamic size and random access, which has performance benefits in some scenarios, but it is possible that the feature you are working on may not really need random access, in which case a list, deque, or some other container may work better for you.

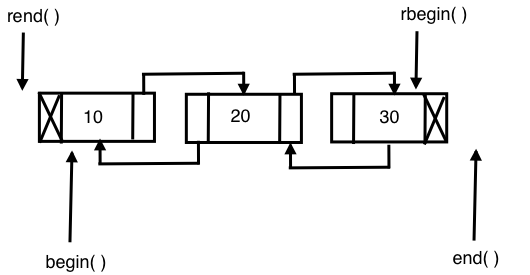

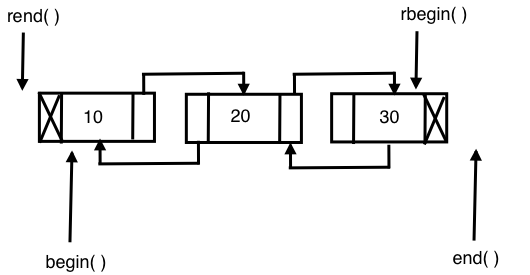

The list STL container makes use of a doubly linked list data structure internally. Hence, a list supports only sequential access, and searching a random value in a list in the worst case may take O(N) runtime complexity. However, if you know for sure that you only need sequential access, the list does offer its own benefits. The list STL container lets you insert data elements at the end, in the front, or in the middle with a constant time complexity, that is, O(1) runtime complexity in the best, average, and worst case scenarios.

The following image demonstrates the internal data structure used by the list STL:

Let's write a simple program to get first-hand experience of using the list STL:

#include <iostream>

#include <list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

list<int> l;

for (int count=0; count<5; ++count)

l.push_back( (count+1) * 100 );

auto pos = l.begin();

cout << "\nPrint the list ..." << endl;

while ( pos != l.end() )

cout << *pos++ << "-->";

cout << " X" << endl;

return 0;

}

I'm sure that by now you have got a taste of the C++ STL, its elegance, and its power. Isn't it cool to observe that the syntax remains the same for all the STL containers? You may have observed that the syntax remains the same no matter whether you are using an array, a vector, or a list. Trust me, you will get the same impression when you explore the other STL containers as well.

Having said that, the previous code is self-explanatory, as we did pretty much the same with the other containers.

Let's try to sort the list, as shown in the following code:

#include <iostream>

#include <list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

list<int> l = { 100, 20, 80, 50, 60, 5 };

auto pos = l.begin();

cout << "\nPrint the list before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "-->" ));

cout << "X" << endl;

l.sort();

cout << "\nPrint the list after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "-->" ));

cout << "X" << endl;

return 0;

}

Did you notice the sort() method? Yes, the list container has its own sorting algorithms. The reason for a list container to support its own version of a sorting algorithm is that the generic sort() algorithm expects a random access iterator, whereas a list container doesn't support random access. In such cases, the respective container will offer its own efficient algorithms to overcome the shortcoming.

Interestingly, the runtime complexity of the sort algorithm supported by a list is O (N log2 N).

The following table shows the most commonly used APIs of an STL list:

|

API |

Description |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the list |

|

back() |

This returns the last value stored in the list |

|

size() |

This returns the count of values stored in the list |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the list is empty, and false otherwise |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values stored in the list |

|

push_back<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a value at the end of the list |

|

push_front<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a value at the front of the list |

|

merge( list ) |

This merges two sorted lists with values of the same type |

|

reverse() |

This reverses the list |

|

unique() |

This removes duplicate values from the list |

|

sort() |

This sorts the values stored in a list |

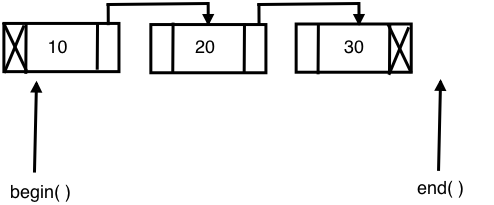

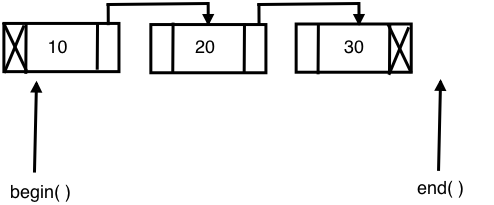

The STL's forward_list container is built on top of a singly linked list data structure; hence, it only supports navigation in the forward direction. As forward_list consumes one less pointer for every node in terms of memory and runtime, it is considered more efficient compared with the list container. However, as price for the extra edge of performance advantage, forward_list had to give up some functionalities.

The following diagram shows the internal data-structure used in forward_list:

Let's explore the following sample code:

#include <iostream>

#include <forward_list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

forward_list<int> l = { 10, 10, 20, 30, 45, 45, 50 };

cout << "\nlist with all values ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << "\nSize of list with duplicates is " << distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) << endl;

l.unique();

cout << "\nSize of list without duplicates is " << distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) << endl;

l.resize( distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) );

cout << "\nlist after removing duplicates ..." << endl;

copy ( l.begin(), l.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output will be as follows:

list with all values ...

10 10 20 30 45 45 50

Size of list with duplicates is 7

Size of list without duplicates is 5

list after removing duplicates ...

10 20 30 45 50

The following code declares and initializes the forward_list container with some unique values and some duplicate values:

forward_list<int> l = { 10, 10, 20, 30, 45, 45, 50 };

As the forward_list container doesn't support the size() function, we used the distance() function to find the size of the list:

cout << "\nSize of list with duplicates is " << distance( l.begin(), l.end() ) << endl;

The following forward_list<int>::unique() function removes the duplicate integers and retains only the unique values:

l.unique();

The following table shows the commonly used forward_list APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the forward_list container |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the forward_list container is empty and false, otherwise |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values stored in forward_list |

|

push_front<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a value to the front of forward_list |

|

merge( list ) |

This merges two sorted forward_list containers with values of the same type |

|

reverse() |

This reverses the forward_list container |

|

unique() |

This removes duplicate values from the forward_list container |

|

sort() |

This sorts the values stored in forward_list |

Let's explore one more example to get a firm understanding of the forward_list container:

#include <iostream>

#include <forward_list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

forward_list<int> list1 = { 10, 20, 10, 45, 45, 50, 25 };

forward_list<int> list2 = { 20, 35, 27, 15, 100, 85, 12, 15 };

cout << "\nFirst list before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

cout << "\nSecond list before sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list2.begin(), list2.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

list1.sort();

list2.sort();

cout << "\nFirst list after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

cout << "\nSecond list after sorting ..." << endl;

copy ( list2.begin(), list2.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << endl;

list1.merge ( list2 );

cout << "\nMerged list ..." << endl;

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

cout << "\nMerged list after removing duplicates ..." << endl;

list1.unique();

copy ( list1.begin(), list1.end(), ostream_iterator<int>(cout, "\t") );

return 0;

}

The preceding code snippet is an interesting example that demonstrates the practical use of the sort(), merge(), and unique() STL algorithms.

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

First list before sorting ...

10 20 10 45 45 50 25

Second list before sorting ...

20 35 27 15 100 85 12 15

First list after sorting ...

10 10 20 25 45 45 50

Second list after sorting ...

12 15 15 20 27 35 85 100

Merged list ...

10 10 12 15 15 20 20 25 27 35 45 45 50 85 100

Merged list after removing duplicates ...

10 12 15 20 25 27 35 45 50 85 100

The output and the program are pretty self-explanatory.

The deque container is a double-ended queue and the data structure used could be a dynamic array or a vector. In a deque, it is possible to insert an element both at the front and back, with a constant time complexity of O(1), unlike vectors, in which the time complexity of inserting an element at the back is O(1) while that for inserting an element at the front is O(N). The deque doesn't suffer from the problem of reallocation, which is suffered by a vector. However, all the benefits of a vector are there with deque, except that deque is slightly better in terms of performance as compared to a vector as there are several rows of dynamic arrays or vectors in each row.

The following diagram shows the internal data structure used in a deque container:

Let's write a simple program to try out the deque container:

#include <iostream>

#include <deque>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

int main () {

deque<int> d = { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 };

cout << "\nInitial size of deque is " << d.size() << endl;

d.push_back( 60 );

d.push_front( 5 );

cout << "\nSize of deque after push back and front is " << d.size() << endl;

copy ( d.begin(), d.end(), ostream_iterator<int>( cout, "\t" ) );

d.clear();

cout << "\nSize of deque after clearing all values is " << d.size() <<

endl;

cout << "\nIs the deque empty after clearing values ? " << ( d.empty()

? "true" : "false" ) << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Intitial size of deque is 5

Size of deque after push back and front is 7

Print the deque ...

5 10 20 30 40 50 60

Size of deque after clearing all values is 0

Is the deque empty after clearing values ? true

The following table shows the commonly used deque APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at ( int index ) |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It throws the std::out_of_range exception if the index is invalid. |

|

operator [ int index ] |

This returns the value stored at the indexed position. It is faster than at( int index ) since no bounds checking is performed by this function. |

|

front() |

This returns the first value stored in the deque. |

|

back() |

This returns the last value stored in the deque. |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the deque is empty and false, otherwise. |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the deque. |

|

capacity() |

This returns the total capacity of the deque, while size() returns the actual number of values stored in the deque. |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values. |

|

push_back<data_type>( value ) |

This adds a new value at the end of the deque. |

Associative containers store data in a sorted fashion, unlike the sequence containers. Hence, the order in which the data is inserted will not be retained by the associative containers. Associative containers are highly efficient in searching a value with O( log n ) runtime complexity. Every time a new value gets added to the container, the container will reorder the values stored internally if required.

The STL supports the following types of associative containers:

Associative containers organize the data as key-value pairs. The data will be sorted based on the key for random and faster access. Associative containers come in two flavors:

The following associative containers come under ordered containers, as they are ordered/sorted in a particular fashion. Ordered associative containers generally use some form of Binary Search Tree (BST); usually, a red-black tree is used to store the data:

The following associative containers come under unordered containers, as they are not ordered in any particular fashion and they use hash tables:

Let's understand the previously mentioned containers with examples in the following subsections.

A set container stores only unique values in a sorted fashion. A set organizes the values using the value as a key. The set container is immutable, that is, the values stored in a set can't be modified; however, the values can be deleted. A set generally uses a red-black tree data structure, which is a form of balanced BST. The time complexity of set operations are guaranteed to be O ( log N ).

Let's write a simple program using a set:

#include <iostream>

#include <set>

#include <vector>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main( ) {

set<int> s1 = { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 };

set<int> s2 = { 2, 3, 7, 8, 10 };

vector<int> v( s1.size() + s2.size() );

cout << "\nFirst set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

cout << "\nSecond set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s2.begin(), s2.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

auto pos = set_difference ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

cout << "\nValues present in set one but not in set two are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

v.clear();

v.resize ( s1.size() + s2.size() );

pos = set_union ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

cout << "\nMerged set values in vector are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

First set values are ...

1 3 5 7 9

Second set values are ...

2 3 7 8 10

Values present in set one but not in set two are ...

1 5 9

Merged values of first and second set are ...

1 2 3 5 7 8 9 10

The following code declares and initializes two sets, s1 and s2:

set<int> s1 = { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 };

set<int> s2 = { 2, 3, 7, 8, 10 };

The following line will ensure that the vector has enough room to store the values in the resultant vector:

vector<int> v( s1.size() + s2.size() );

The following code will print the values in s1 and s2:

cout << "\nFirst set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

cout << "\nSecond set values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s2.begin(), s2.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

The set_difference() algorithm will populate the vector v with values only present in set s1 but not in s2. The iterator, pos, will point to the last element in the vector; hence, the vector resize will ensure that the extra spaces in the vector are removed:

auto pos = set_difference ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

The following code will print the values populated in the vector v:

cout << "\nValues present in set one but not in set two are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

The set_union() algorithm will merge the contents of sets s1 and s2 into the vector, and the vector is then resized to fit only the merged values:

pos = set_union ( s1.begin(), s1.end(), s2.begin(), s2.end(), v.begin() );

v.resize ( pos - v.begin() );

The following code will print the merged values populated in the vector v:

cout << "\nMerged values of first and second set are ..." << endl;

copy ( v.begin(), v.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

The following table describes the commonly used set APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

insert( value ) |

This inserts a value into the set |

|

clear() |

This clears all the values in the set |

|

size() |

This returns the total number of entries present in the set |

|

empty() |

This will print true if the set is empty, and returns false otherwise |

|

find() |

This finds the element with the specified key and returns the iterator position |

|

equal_range() |

This returns the range of elements matching a specific key |

|

lower_bound() |

This returns an iterator to the first element not less than the given key |

|

upper_bound() |

This returns an iterator to the first element greater than the given key |

A map stores the values organized by keys. Unlike a set, a map has a dedicated key per value. Maps generally use a red-black tree as an internal data structure, which is a balanced BST that guarantees O( log N ) runtime efficiency for searching or locating a value in the map. The values stored in a map are sorted based on the key, using a red-black tree. The keys used in a map must be unique. A map will not retain the sequences of the input as it reorganizes the values based on the key, that is, the red-black tree will be rotated to balance the red-black tree height.

Let's write a simple program to understand map usage:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

map<string, long> contacts;

contacts["Jegan"] = 123456789;

contacts["Meena"] = 523456289;

contacts["Nitesh"] = 623856729;

contacts["Sriram"] = 993456789;

auto pos = contacts.find( "Sriram" );

if ( pos != contacts.end() )

cout << pos->second << endl;

return 0;

}

Let's compile and check the output of the program:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output is as follows:

Mobile number of Sriram is 8901122334

The following line declares a map with a string name as the key and a long mobile number as the value stored in the map:

map< string, long > contacts;

The following code snippet adds four contacts organized by name as the key:

contacts[ "Jegan" ] = 1234567890;

contacts[ "Meena" ] = 5784433221;

contacts[ "Nitesh" ] = 4567891234;

contacts[ "Sriram" ] = 8901122334;

The following line will try to locate the contact with the name, Sriram, in the contacts map; if Sriram is found, then the find() function will return the iterator pointing to the location of the key-value pair; otherwise it returns the contacts.end() position:

auto pos = contacts.find( "Sriram" );

The following code verifies whether the iterator, pos, has reached contacts.end() and prints the contact number. Since the map is an associative container, it stores a key=>value pair; hence, pos->first indicates the key and pos->second indicates the value:

if ( pos != contacts.end() )

cout << "\nMobile number of " << pos->first << " is " << pos->second << endl;

else

cout << "\nContact not found." << endl;

The following table shows the commonly used map APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

at ( key ) |

This returns the value for the corresponding key if the key is found; otherwise it throws the std::out_of_range exception |

|

operator[ key ] |

This updates an existing value for the corresponding key if the key is found; otherwise it will add a new entry with the respective key=>value supplied |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the map is empty, and false otherwise |

|

size() |

This returns the count of the key=>value pairs stored in the map |

|

clear() |

This clears the entries stored in the map |

|

count() |

This returns the number of elements matching the given key |

|

find() |

This finds the element with the specified key |

A multiset container works in a manner similar to a set container, except for the fact that a set allows only unique values to be stored whereas a multiset lets you store duplicate values. As you know, in the case of set and multiset containers, the values themselves are used as keys to organize the data. A multiset container is just like a set; it doesn't allow modifying the values stored in the multiset.

Let's write a simple program using a multiset:

#include <iostream>

#include <set>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

multiset<int> s = { 10, 30, 10, 50, 70, 90 };

cout << "\nMultiset values are ..." << endl;

copy ( s.begin(), s.end(), ostream_iterator<int> ( cout, "\t" ) );

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The output can be viewed with the following command:

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Multiset values are ...

10 30 10 50 70 90

Interestingly, in the preceding output, you can see that the multiset holds duplicate values.

A multimap works exactly as a map, except that a multimap container will allow multiple values to be stored with the same key.

Let's explore the multimap container with a simple example:

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <vector>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

multimap< string, long > contacts = {

{ "Jegan", 2232342343 },

{ "Meena", 3243435343 },

{ "Nitesh", 6234324343 },

{ "Sriram", 8932443241 },

{ "Nitesh", 5534327346 }

};

auto pos = contacts.find ( "Nitesh" );

int count = contacts.count( "Nitesh" );

int index = 0;

while ( pos != contacts.end() ) {

cout << "\nMobile number of " << pos->first << " is " <<

pos->second << endl;

++index;

if ( index == count )

break;

}

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Mobile number of Nitesh is 6234324343

Mobile number of Nitesh is 5534327346

An unordered set works in a manner similar to a set, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A set makes use of red-black trees while an unordered set makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of set operations is O( log N) while the time complexity of unordered set operations is O(1); hence, the unordered set tends to be faster than the set.

The values stored in an unordered set are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in a set, which stores values in a sorted fashion. If performance is the criteria, then an unordered set is a good bet; however, if iterating the values in a sorted fashion is a requirement, then set is a good choice.

An unordered map works in a manner similar to a map, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A map makes use of red-black trees while unordered map makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of map operations is O( log N) while that of unordered map operations is O(1); hence, an unordered map tends to be faster than a map.

The values stored in an unordered map are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in a map where values are sorted by keys.

An unordered multiset works in a manner similar to a multiset, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A multiset makes use of red-black trees while an unordered multiset makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of multiset operations is O( log N) while that of unordered multiset operations is O(1). Hence, an unordered multiset tends to be faster than a multiset.

The values stored in an unordered multiset are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in a multiset where values are stored in a sorted fashion. If performance is the criteria, unordered multisets are a good bet; however, if iterating the values in a sorted fashion is a requirement, then multiset is a good choice.

An unordered multimap works in a manner similar to a multimap, except that the internal behavior of these containers differs. A multimap makes use of red-black trees while an unordered multimap makes use of hash tables. The time complexity of multimap operations is O( log N) while that of unordered multimap operations is O(1); hence, an unordered multimap tends to be faster than a multimap.

The values stored in an unordered multimap are not organized in any particular fashion, unlike in multimaps where values are sorted by keys. If performance is the criteria, then an unordered multimap is a good bet; however, if iterating the values in a sorted fashion is a requirement, then multimap is a good choice.

Container adapters adapt existing containers to provide new containers. In simple terms, STL extension is done with composition instead of inheritance.

STL containers can't be extended by inheritance, as their constructors aren't virtual. Throughout the STL, you can observe that while static polymorphism is used both in terms of operator overloading and templates, dynamic polymorphism is consciously avoided for performance reasons. Hence, extending the STL by subclassing the existing containers isn't a good idea, as it would lead to memory leaks because container classes aren't designed to behave like base classes.

The STL supports the following container adapters:

Let's explore the container adapters in the following subsections.

Stack is not a new container; it is a template adapter class. The adapter containers wrap an existing container and provide high-level functionalities. The stack adapter container offers stack operations while hiding the unnecessary functionalities that are irrelevant for a stack. The STL stack makes use of a deque container by default; however, we can instruct the stack to use any existing container that meets the requirement of the stack during the stack instantiation.

Deques, lists, and vectors meet the requirements of a stack adapter.

A stack operates on the Last In First Out (LIFO) philosophy.

The following table shows commonly used stack APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

top() |

This returns the top-most value in the stack, that is, the value that was added last |

|

push<data_type>( value ) |

This will push the value provided to the top of the stack |

|

pop() |

This will remove the top-most value from the stack |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values present in the stack |

|

empty() |

This returns true if the stack is empty; otherwise it returns false |

It's time to get our hands dirty; let's write a simple program to use a stack:

#include <iostream>

#include <stack>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

stack<string> spoken_languages;

spoken_languages.push ( "French" );

spoken_languages.push ( "German" );

spoken_languages.push ( "English" );

spoken_languages.push ( "Hindi" );

spoken_languages.push ( "Sanskrit" );

spoken_languages.push ( "Tamil" );

cout << "\nValues in Stack are ..." << endl;

while ( ! spoken_languages.empty() ) {

cout << spoken_languages.top() << endl;

spoken_languages.pop();

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following command:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Values in Stack are ...

Tamil

Kannada

Telugu

Sanskrit

Hindi

English

German

French

From the preceding output, we can see the LIFO behavior of stack.

A queue works based on the First In First Out (FIFO) principle. A queue is not a new container; it is a templatized adapter class that wraps an existing container and provides the high-level functionalities that are required for queue operations, while hiding the unnecessary functionalities that are irrelevant for a queue. The STL queue makes use of a deque container by default; however, we can instruct the queue to use any existing container that meets the requirement of the queue during the queue instantiation.

In a queue, new values can be added at the back and removed from the front. Deques, lists, and vectors meet the requirements of a queue adapter.

The following table shows the commonly used queue APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

push() |

This appends a new value at the back of the queue |

|

pop() |

This removes the value at the front of the queue |

|

front() |

This returns the value in the front of the queue |

|

back() |

This returns the value at the back of the queue |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the queue is empty; otherwise it returns false |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the queue |

Let's use a queue in the following program:

#include <iostream>

#include <queue>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

queue<int> q;

q.push ( 100 );

q.push ( 200 );

q.push ( 300 );

cout << "\nValues in Queue are ..." << endl;

while ( ! q.empty() ) {

cout << q.front() << endl;

q.pop();

}

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following commands:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Values in Queue are ...

100

200

300

From the preceding output, you can observe that the values were popped out in the same sequence that they were pushed in, that is, FIFO.

A priority queue is not a new container; it is a templatized adapter class that wraps an existing container and provides high-level functionalities that are required for priority queue operations, while hiding the unnecessary functionalities that are irrelevant for a priority queue. A priority queue makes use of a vector container by default; however, a deque container also meets the requirement of the priority queue. Hence, during the priority queue instantiation, you could instruct the priority queue to make use of a deque as well.

A priority queue organizes the data in such a way that the highest priority value appears first; in other words, the values are sorted in a descending order.

The deque and vector meet the requirements of a priority queue adaptor.

The following table shows commonly used priority queue APIs:

|

API |

Description |

|

push() |

This appends a new value at the back of the priority queue |

|

pop() |

This removes the value at the front of the priority queue |

|

empty() |

This returns true when the priority queue is empty; otherwise it returns false |

|

size() |

This returns the number of values stored in the priority queue |

|

top() |

This returns the value in the front of the priority queue |

Let's write a simple program to understand priority_queue:

#include <iostream>

#include <queue>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main () {

priority_queue<int> q;

q.push( 100 );

q.push( 50 );

q.push( 1000 );

q.push( 800 );

q.push( 300 );

cout << "\nSequence in which value are inserted are ..." << endl;

cout << "100\t50\t1000\t800\t300" << endl;

cout << "Priority queue values are ..." << endl;

while ( ! q.empty() ) {

cout << q.top() << "\t";

q.pop();

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}

The program can be compiled and the output can be viewed with the following command:

g++ main.cpp -std=c++17

./a.out

The output of the program is as follows:

Sequence in which value are inserted are ...

100 50 1000 800 300

Priority queue values are ...

1000 800 300 100 50

From the preceding output, you can observe that priority_queue is a special type of queue that reorders the inputs in such a way that the highest value appears first.

In this chapter you learned about ready-made generic containers, functors, iterators, and algorithms. You also learned set, map, multiset, and multimap associative containers, their internal data structures, and common algorithms that can be applied on them. Further you learned how to use the various containers with practical hands-on code samples.

In the next chapter, you will learn template programming, which helps you master the essentials of templates.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

Let's now start learning generic programming.

Generic programming is a style of programming that helps you develop reusable code or generic algorithms that can be applied to a wide variety of data types. Whenever a generic algorithm is invoked, the data types will be supplied as parameters with a special syntax.