Chapter 2. The Big Picture

Chapter 2. SVG and the Web

In the last few years, a quiet revolution has been taking place in web browsers and operating systems. Solid implementations of SVG have become standard in both desktop and mobile browsers.

As this has happened, web developers and designers have become more confident in using SVG to display content that moves beyond HTML layout. They have also been combining SVG with the power of the newer, efficient, and standardized JavaScript engines to build sophisticated information graphics and interactive games. Anyone working with data visualization on the web is now gaining familiarity with SVG as a tool.

The history of SVG has not been straightforward.

As with HTML, CSS, and the other standards that make up the web, the development of SVG has been a process of back-and-forth compromises between the authors of specifications, the builders of web browsers that implement them, and the designers of web pages that use them. Unlike those other languages, however, the SVG specification did not develop slowly and incrementally—it was created fully formed, as an incredibly complex graphics language.

If you work with HTML and CSS web design, you will find many aspects of SVG familiar—and a few quite different. The SVG standard was built upon other web standards, most notably XML and CSS, and has a complex DOM that can be manipulated with JavaScript. In that way, it is very similar to HTML. But because the primary focus of SVG is graphics, not text, it intersects and connects the parts of the web platform that you usually try to keep separate: content, formatting, and functionality.

This chapter starts with a refresher about the main web languages and their separate roles. It then looks at how SVG interacts with these languages. We adapt the stoplight example from Chapter 1 to show how you can build on a simple SVG to create complete web pages.

SVG and the Web Platform

If you are only interested in SVG as an image format—as a tool to create static, unchanging pictures—you don’t need to worry too much about the other web standards. To take full advantage of SVG as a graphical web application, however, you will need to leverage the entire web platform to build and extend your graphics.

Where does SVG fit on the web platform? SVG is an XML language, describing a structured document. However, because SVG is a graphics format, the structure of the document cannot be separated from its visual presentation. SVG elements represent geometric shapes, text, and embedded images that will be displayed onscreen according to a clearly defined geometric layout. Other markup defines complex artistic effects to be applied to the graphical elements.

SVG exists because not all documents can be displayed with HTML and CSS. Sometimes content and layout are inseparable. In charts and diagrams, the position of text conveys its meaning as much as the words it contains. Other meaning is conveyed by symbols, colors, and shapes—without any words at all. Any complete representation of the content of these documents includes the layout and graphical features.

The same could be said about any image, and images have been part of web pages since the early days of HTML. The W3C even standardized the PNG (Portable Network Graphics) image format, which encodes icons and diagrams in compact files and can be used royalty-free by any software or developer.

But SVG is different. All other image formats on the web are displayed as single, complete entities. SVG, as an XML document, has structured content with a corresponding DOM (document object model). Stylesheets and scripts can access and modify the components of the graphic. Search engines and assistive technologies can read text labels and metadata.

SVG on the web can be used as independent files—as complete web pages or web apps—with hyperlinks and JavaScript-based interaction to connect it to the rest of the web. However, SVG was not designed to display large blocks of text. Nor does it include form-input elements or other specialized features of HTML.

The most effective use of SVG is not as a replacement for HTML, but as a complement to it. SVG web applications are nearly always presented as part of larger HTML web pages, either as embedded objects or—with increasing frequency—directly included inline within the HTML markup.

The Changing Web

As SVG has been integrated into web pages, the web pages themselves have changed. The HTML5 specification and the many CSS level 3 (and beyond!) modules have significantly changed the relationship between SVG and the rest of the web platform. The dramatically improved performance of JavaScript since 2009 and the rise of JavaScript-based SVG libraries, such as Snap.svg and D3.js, are smoothing away many of the rough edges between implementations.

Note

This book uses the terms HTML5 and CSS3 fairly generically. One of the main references for HTML, the WHATWG Living Standard, doesn’t use any version numbers; the competing spec at W3C is progressing through version numbers 5.1 to 5.2. These incremental changes can all be thought of as HTML5+.

On the CSS side, the level 3 and 4 modules of existing features are being developed at the same time as level 1 and 2 modules for new features. All of these (essentially, anything beyond the CSS 2.1 specification) can be thought of as CSS3+.

Nonetheless, when working with SVG in the browser, you must always be aware that implementations of the SVG standards are imperfect, incomplete, and frequently changing. This becomes all the more important when you are taking advantage of the features of HTML5 and CSS3 that directly integrate SVG. Cross-browser compatibility is an issue not only as it relates to support of the SVG standard, but also as it relates to support for new features in HTML, CSS, DOM, and JavaScript.

At the time of writing, the best supported version of SVG is 1.1; this specification was created in 2005, without any major new features being added to the original SVG standard. It was republished in 2011 as a second edition, with corrections and a new format, but the same features.

A proposed SVG 2 standard was published in September 2016. It adds many commonly requested features, clarifies numerous details, and improves coordination with HTML and CSS. Other more advanced SVG features are being proposed through additional modules.

Note

There have been other SVG efforts, but these have not had a significant impact on the web. The draft SVG 1.2 standard was ambitious, adding features that would put it in line to replace Microsoft PowerPoint, as well as advanced vector manipulation of graphics. It was abandoned as unworkable when it became clear that the future of SVG would be in the browsers, not specialized software.

A simplified standard, SVG Tiny, was developed for mobile devices. The SVG Tiny 1.2 standard was finalized, with some new features from the main SVG 1.2 proposal; however, it fell out of favor as mobile browsers shifted toward displaying standard web pages.

At the time of writing, there is some risk that SVG 2 may be added to this list. Some features have initial browser implementations, but on other features, none of the implementation teams are ready to make the first move.

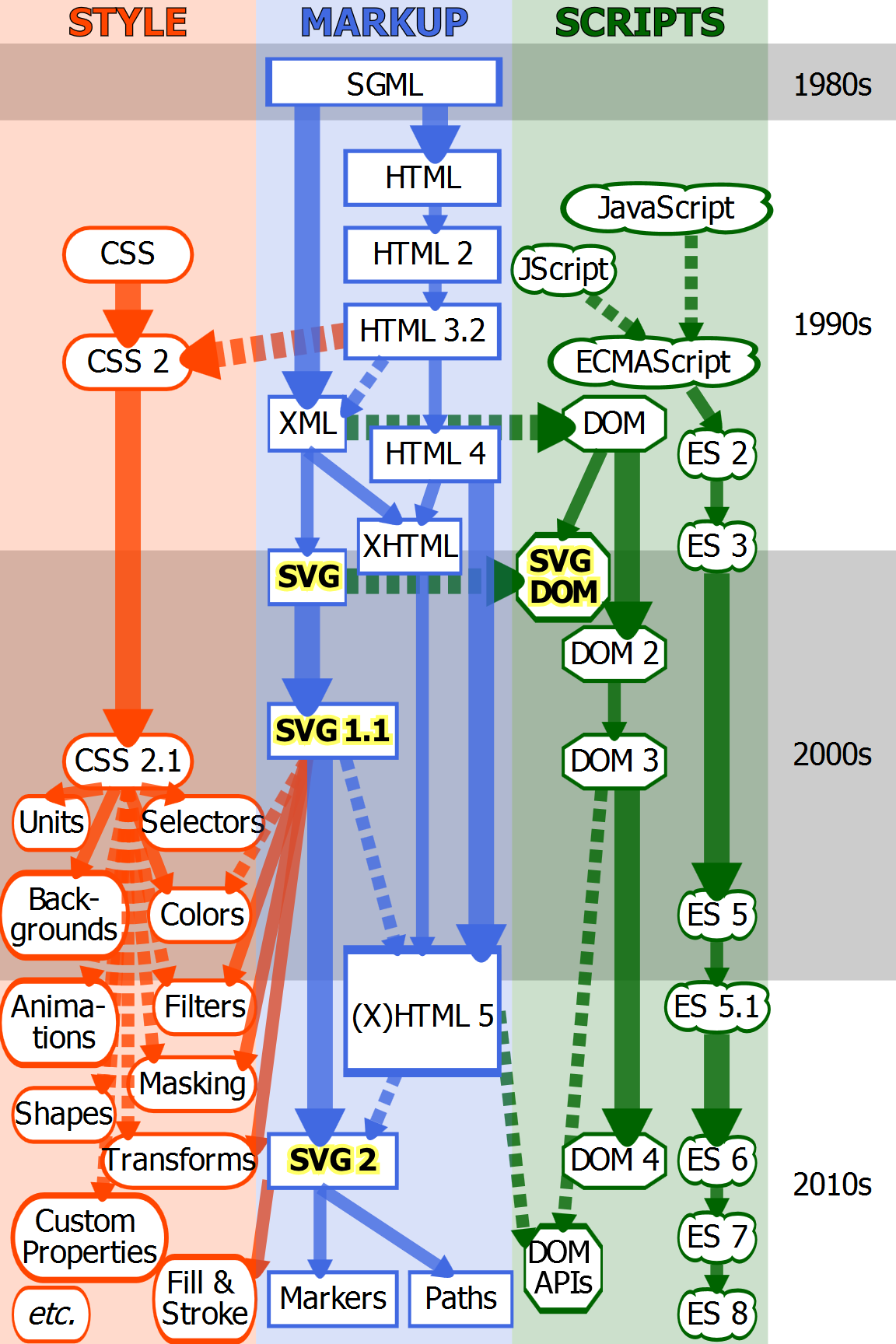

The other web platform languages have also been revised, in parallel to the SVG work. Figure 2-1 sketches out a rough timeline of the past quarter-century of web standards. At the time SVG 1.1 was finalized, the established standards in other areas of the web included CSS level 2, DOM level 2, and ECMAScript (ES) level 3.

Warning

Many SVG-centric tools, such as Apache Batik and libRSVG, have not significantly updated their CSS implementations since then, nor (in the case of Batik) their DOM and JavaScript implementations.

In contrast, as of SVG 2’s publication, the latest web browsers all support DOM level 3 (and much of DOM 4) and ES 5.1 (and some ES 6), as well as many CSS3+ features. And more features are added with every browser update.

This book focuses on SVG in the web browser, and it will often take advantage of the new features from other web specifications. However, many older web browsers and other software are still in use. We will identify areas where you’re likely to stumble across backward-compatibility issues, and suggest workaround or fallback options.

Figure 2-1. Timeline of web platform standards. Solid arrows indicate direct extensions of existing standards; dashed arrows represent more indirect inspiration. Specifications that were abandoned, such as SVG 1.2 or ECMAScript (ES) 4, are not included.

There is another area of browser support to keep in mind: support for SVG at all.

Every major web browser released since 2012 supports both SVG images and inline SVG. But at the time of writing (mid-2017), some older browsers are still in use. The ones you are most likely to need to worry about:

-

Internet Explorer versions 8 and earlier

-

the stock browser for Android versions 2.3 and earlier

If any of these make up an important component of your website’s audience (based on your user-analytics data), you’ll need to consider fallback options.

This book is also very aware of the fact that SVG is still developing. New CSS modules are extending SVG functionality, and SVG 2 introduces a variety of changes. Throughout the book we will highlight these proposed features, which—while not quite ready for production work—are useful to keep in mind as you learn the language. A graphic that is difficult to create now may be much easier with a new tool. The possibilities will be highlighted with “Future Focus” sidebars like the following:

While there is still some inconsistency between the various SVG implementations, most browsers now have sufficient support for static scalable vector graphics and JavaScript-based dynamic content that it is possible to build complete graphical web applications with SVG.

JavaScript in SVG

If you’ve used JavaScript to create a dynamic HTML page, you can use it to create dynamic SVG. SVG elements inherit all the core DOM methods to get and set attributes and styles. The JavaScript itself is parsed and run by the same JS interpreter and just-in-time compiler that runs scripts in your HTML pages.

Tip

That means that you can use modern JavaScript syntax (ES6 and beyond) in modern browsers. However, the examples in this book all use ES5 syntax that should run without error on any browser that supports SVG.

Of course, there are a few complications: SVG is a namespaced XML language, so you need to use namespace-sensitive DOM methods when you’re creating elements or setting xlink attributes. This is true even when creating inline SVG elements in an HTML document. Element and attribute names are also always case-sensitive when created via the DOM.

Programmers switching from HTML to SVG often create code like the following, and wonder why nothing is displaying on the screen:

varsvg=document.createElement("svg");varuse=document.createElement("use");use.setAttribute("xlink:href","#icon");svg.appendChild(use);document.body.appendChild(svg);

This code will create elements that look correct if you inspect them in your browser’s developer tools. If you copy and paste the generated markup to a new file, it will even work correctly if you open that file. But that’s because your friendly neighborhood HTML parser will read the markup in that file and insert the correct namespaces. The DOM methods don’t do that for you.

Creating elements named “svg” and “use” in an HTML document, without setting a namespace, just creates HTMLUnknownElement objects with those names. Doing the same in an SVG document creates generic XML Element objects.

Tip

If you’re ever unsure of what type of JavaScript object you’re working with, you can print its constructor.name property to the console. The constructor property of an object is the function that defined it. And a function’s name property is a simple string containing its, well, name.

In the same way, setting an attribute with the name xlink:href creates an attribute with that literal name, including the : character.

The following code creates similar-looking elements, but this time with the correct namespaces. It will add an inline SVG icon to the end of the page (assuming you already have another SVG element with id="icon" somewhere in the page):

varns={svg:"http://www.w3.org/2000/svg",xlink:"http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink"};varsvg=document.createElementNS(ns.svg,"svg");varuse=document.createElementNS(ns.svg,"use");use.setAttributeNS(ns.xlink,"href","#icon");svg.appendChild(use);document.body.appendChild(svg);

It’s definitely not ideal. Once again, you have to hardcode XML namespace URLs in your code.

Alternatively, you can use the HTML parser from JavaScript, by setting the innerHTML property of an HTML element:

vardiv=document.createElement("div");div.innerHTML='<svg><use xlink:href="#icon" /></svg>'document.body.appendChild(div.firstChild);

Much better! But be warned: this only works in an HTML document, which will correctly create an HTMLElement object for the <div>.

The latest versions of web browsers even support innerHTML on SVG elements, but that is a recent addition to the core DOM specs. It isn’t supported in older browsers, because innerHTML was previously only defined for HTML elements.

Tip

In browsers that support it, setting innerHTML on an SVG element will use either the HTML or XML parser, depending on what type of document the code is running in.

As we discuss in Chapter 4, JavaScript libraries that are designed to work with SVG can take care of this namespace hassle—but JavaScript libraries designed only for HTML can create the same problems as the initial broken code snippet.

Also be aware that some methods you may be familiar with from HTML are not part of the core DOM specifications. Some of these, such as the focus() method to control keyboard focus, have been added to SVG elements in SVG 2—but they aren’t universally implemented yet.

Even worse, some features, such as className, look similar between HTML and SVG, but are structured differently. Many existing API patterns were ignored by the original SVG DOM definitions. List data types used numberOfItems instead of length, and didn’t support JavaScript object [index] access; SVG 2 has added the more familiar patterns, but again—support isn’t universal yet.

Warning

Because of these changes, scripts might work well in your browser but stumble in others. At the time of writing, Chrome and Firefox support most of the SVG 2 DOM changes, but Safari/WebKit and Microsoft Edge are a little further behind. And of course, older versions of all browsers may have problems.

As a sort of consolation prize for the missing HTML DOM methods and mismatched patterns, the SVG specifications introduced a variety of SVG-specific methods and properties to make graphical calculations easier. Unfortunately, many of these features were not universally implemented, and some have become obsolete as SVG switches to an animation model more compatible with CSS. Nonetheless, there are still a few useful features that can be relied on in most web browsers.

You can do a lot with these and the core DOM methods that have good support. We’ll have numerous simple examples of scripted SVG throughout the book.

Which brings up the question: how do you get your JavaScript into your SVG?

If you’re working with inline SVG, any script running in your HTML file has access to your inline SVG elements. So you can include an HTML <script> element in the page <head> or <body>, as you usually would.

SVG also has its own <script> element. To add JavaScript to a standalone SVG file, you can include a <script> element anywhere between the opening and closing <svg> tags. The SVG <script> element is very similar to its HTML counterpart, but they aren’t identical.

Tip

If you include a <script> element as a child of an <svg> element that is inline in HTML, the parser will create an SVGScriptElement, not an HTMLScriptElement.

To include an external JavaScript file with an SVG <script> element, use an xlink:href attribute (not src like in HTML) to give the file location.

If you instead include the JavaScript code between the <script> tags, remember to wrap it in an XML character data (CDATA) block, so that less-than and greater-than operators or ampersands (<, >, and &) do not cause XML validation errors. Combining both types of scripts would look like Example 2-1.

Example 2-1. Adding scripts to a standalone SVG file

<svgxmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"xml:lang="en"xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink"><title>My Standalone D3 Data Visualization</title><scriptxlink:href="/assets/d3.min.js"/><script><![CDATA[if(1<0){console.log("Uh oh, math is broken.","But my XML markup isn't.");}/* more & more JS code */]]></script></svg>

Since we’re using an

xlink:hrefattribute later, we included the extra namespace declaration on the root<svg>element.

Because this is XML, a

<script>tag can be self-closing (with/>) if it doesn’t have any text content.

The

<![CDATA[ ... ]]>structure can be used anywhere in an XML file to indicate that the enclosed text should be treated as plain text, not markup. It’s usually required for JavaScript, and can also be used for CSS code that might have special characters in comments.

The CDATA markup should also be fine if you copy the SVG code into an HTML file, but only if it is inside an inline <svg>, not in a (non-XML) HTML script.

Tip

To be extra sure that your scripts don’t break, regardless of XML or HTML parser, you can use JavaScript line comments to hide the CDATA markup:

<script>//<![CDATA[/* This script will work wherever. *///]]></script>

As in HTML, scripts in an SVG file are executed in the order they appear in the markup. When a script references an external file, the browser waits until the file has downloaded and run before continuing. The SVG <script> element does not yet have an async or defer attribute, equivalent to those added to HTML5. Of course, if you’re using inline SVG, you can use asynchronous HTML script elements to manipulate your SVG elements.

Tip

There’s one other way to get JavaScript into your SVG: onevent attributes, like onload or onclick. These work much the same way as in HTML, and—just like in HTML—they are mostly discouraged in the modern web.

We’ve already alluded to one common use of scripted SVG: cross-browser animation support. Example 2-2 shows JavaScript that could be used to replace the CSS animation from Examples 1-8 or 1-9 from Chapter 1. The code uses classes to select the elements, so it works with either the simple or labeled SVG markup: just remember to remove the CSS animation code from the <style> element!

The <script> element should be included at the end of the file (right before the closing </svg> tag). That way, it won’t run until the rest of the file has been parsed.

Example 2-2. Using JavaScript to animate an SVG stoplight

<script><![CDATA[(function(){varlights=["green","yellow","red"];varnLights=lights.length;varlit=2;functioncycle(){lit=(lit+1)%nLights;varlitElement,selector;for(vari=0;i<nLights;i++){selector="."+lights[i]+" .lit";litElement=document.querySelector(selector);litElement.style["visibility"]=(i==lit)?"visible":"hidden";}}cycle();setInterval(cycle,3000);})();]]></script>

The code is contained in an immediately-invoked anonymous function. Although not required, this is good coding practice to avoid conflicts between different scripts on a page. A function creates a closure to encapsulate variables. The “immediately-invoked anonymous” part means we are going to run it immediately after defining it, and don’t need a name to refer to it later.

The

lightsarray holds the class names that distinguish each light group. Because the number of lights won’t be changing, we can store it in a variable as well.

The red light is initially lit in the markup; this corresponds to index 2 in the

lightsarray (JavaScript array indices start at 0 for the first element).

The

cycle()function will change the lights.

To start the cycle, the

litvariable is advanced by one; the modulus operator (%) ensures that it cycles back to 0 when it reaches the length of the array.

At each stage of the cycle, each color of light will be modified to either hide or show the “lit” graphic. One of the three won’t change, but updating them all keeps the code simple and ensures that it only depends on the

litstate, not on knowledge of the current DOM styles.

The “lit”

<use>element for each color is retrieved via thequerySelector()method; a CSS selector of the form “.red .lit” will select the first element of classlitthat is a child of an element with classred.

The

visibilitystyle property is set to eithervisibleorhiddenaccording to whether this light should currently be lit. Modifying thestyleproperty of an element object has the same effect as setting an inline style. It therefore overrides the presentation attribute in the markup.

The cycle function is run once to turn the light green, and then is called at regular intervals on a 3-second (3,000ms) timer.

The anonymous function is run immediately: the syntax

(function(){ /*...*/ })()parses and runs the encapsulated code.

Although this isn’t a full web application—there is no interaction with the user—it demonstrates how SVG elements can be accessed and modified from a script.

There’s nothing SVG-specific about the JavaScript code: it selects elements using CSS selectors and the document.querySelector() method, and sets the visibility style according to which lit bulb should be displayed. A timer runs the cycle again after every 3-second interval.

Warning

The querySelector() method and its sibling querySelectorAll() are convenient ways to locate elements. Because they use CSS selectors, they can find elements based on any combination of tag names, class names, and parent-child relationships. However, versions of WebKit and Blink browsers prior to mid-2015 had a bug that prevented them from working for SVG mixed-case tag and attribute names, such as linearGradient or viewBox, in HTML documents. Related bugs affected the getElementsByTagName() methods.

To improve backward compatibility, use classes on these elements if you need to select them in your inline SVG code.

JavaScript and SVG can do more than recreate simple animations, of course.

Scripts can be used to implement complex logic and user interaction. They are also useful for calculating the coordinates of shapes in geometric designs and data visualizations. You could even use JavaScript to implement your own form-input elements or wrapped-text blocks in SVG. But it’s generally easier to use HTML for that.

The stoplight graphic now cycles through green, yellow, and red lights when you view it in any modern web browser, and even in Internet Explorer 9 (the earliest IE to have SVG support). However, you won’t get any animation, in any browser, if you reference the SVG from the src attribute of an HTML <img> element!

It’s an extra complication when you’re dealing with SVG in web pages: the behavior of SVG on the web can be quite different, depending on how the SVG is incorporated in the page.

Embedding SVG in Web Pages

If you’re using SVG on the web, you’ll usually want to integrate the graphics within larger HTML files. There are three main ways that SVG can be added to web pages:

-

SVG as an image

-

SVG as an embedded document

-

inline SVG

Each embedding mode has advantages and disadvantages.

SVG as an HTML Image

The most straightforward method of combining SVG and HTML is to use a self-contained SVG file as an image in the HTML <img> tag.

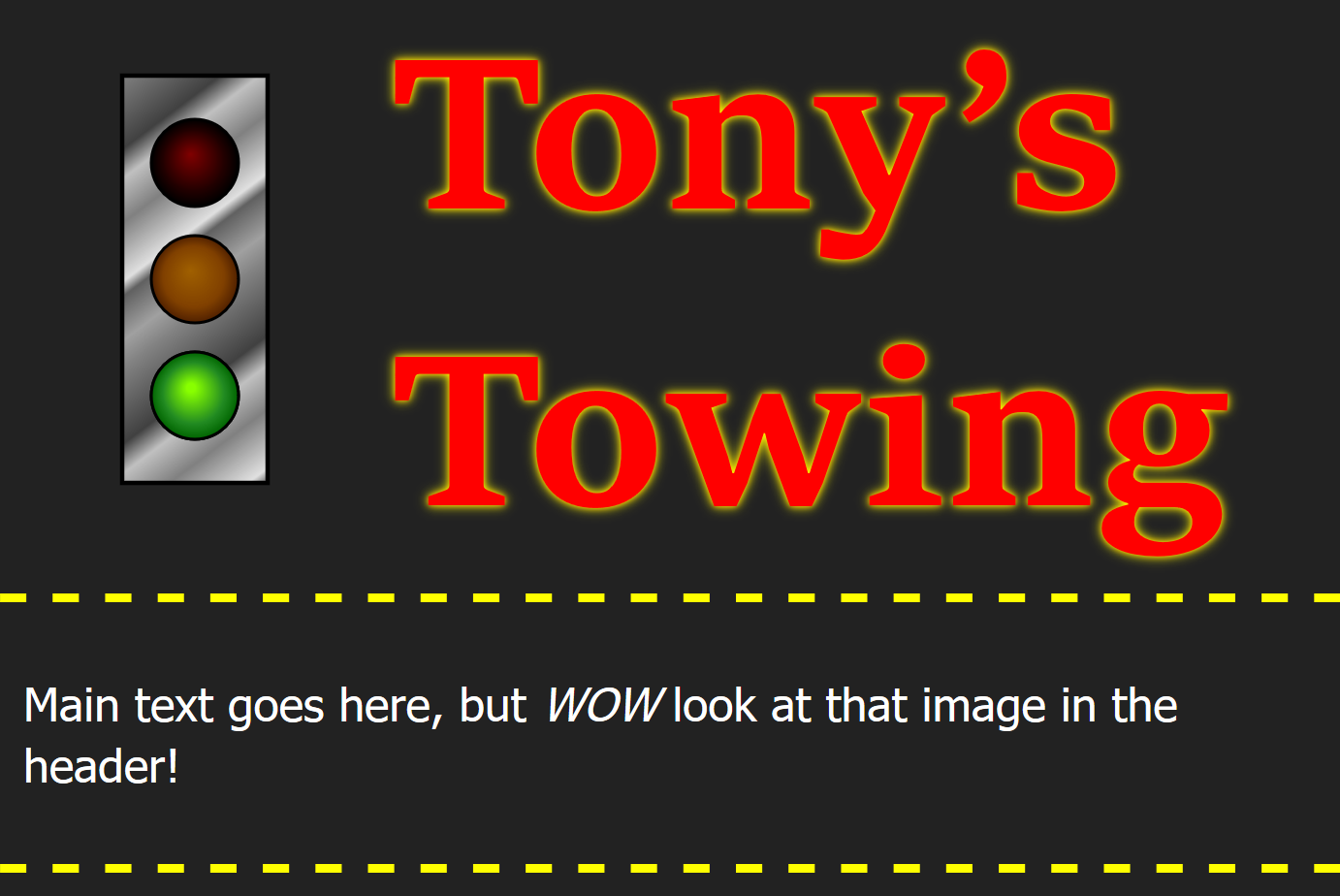

Figure 2-2. Sample web page using an SVG image file

Example 2-3 provides the code for a super-simple web page using the CSS-animated SVG stoplight from Example 1-8. Figure 2-2 shows the result.

Example 2-3. CSS-animated stoplight as an image in a web page

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>SVG Images within HTML</title><style>body{background-color:#222;color:white;margin:0;padding:0;font-family:sans-serif;}header,main{border-bottom:dashedyellow;}header{min-height:12em;font-family:serif;}headerh1{margin:0;color:red;text-shadow:yellow004px,orange002px;font-size:500%;}headerimg{height:10em;float:left;margin:1em2em;}p{padding:0.5em;}</style></head><body><header><imgsrc="../ch01-overview-files/animated-stoplight-css.svg"role="img"alt="Traffic light"/><h1>Tony’s Towing</h1></header><main><p>Main text goes here, but<em>WOW</em>look at that image in the header!</p></main></body></html>

The <img> element should be familiar to most web developers. The src attribute provides the URL of the image file. An alt attribute provides text that will be shown if the user has turned off image downloads, or is using a screen reader. It will also be shown in older browsers that can’t render SVG.

The role="img" attribute would normally be redundant on an <img> element. It is required to fix an SVG-specific accessibility bug in Apple’s VoiceOver screen reader:

Warning

Without role="img", some versions of WebKit+VoiceOver treat an <img> element with an SVG source as an embedded document. The alt attribute is ignored, as the browser instead looks for titles in the SVG file.

This is one more reason you should always have a <title> in your standalone SVG files. But the title for the SVG might not be a good alternative text for the way you are using it in this web page. So use role="img" and alt to get consistent alternative text for all users.

In HTML5+, the <img> element has a big sister, the <picture> element, and a new attribute srcset. Together, they allow you to give the browser a set of alternative versions of the image to use in different contexts. The most common use is to provide low- and high-resolution versions of a photograph, for different screen sizes and screen resolutions.

With SVG images, you don’t need to worry about screen resolution. So you won’t need srcset. But <picture> can still be useful.

A <picture> element allows you to provide alternative file types as well as alternative file sizes. As a result, it can be used to provide a fallback raster image for SVG.

The <picture> element is always used in combination with an <img>. It groups that image with the <source> elements that define alternative files. For SVG fallback, the <img> element references your fallback image (a PNG, GIF, or JPEG), and will be used in older browsers. A <source> element references the SVG equivalent, and is used in modern browsers. The syntax is as follows:

<picture><sourcetype="image/svg+xml"srcset="url-to-graphic.svg"/><imgsrc="url-to-fallback.png"alt="Description"/></picture>

Note that you must use srcset, not src, on a <source> element inside a <picture>, even though there is only one file in the set.

Warning

Browsers that support SVG but don’t support <picture> will get the fallback. This includes Internet Explorer 9 to 11, and Safari 4 to 9. All browsers released in 2016 or later (and some released before then) will get the SVG.

If you really want users on medium-old browsers to get the SVG instead of the PNG, you can add a JavaScript polyfill like PictureFill. But you have to weigh the benefits of SVG against the cost of the extra JavaScript.

There are a couple other features to emphasize in Example 2-3. First, note that the height of the image is being set in em-units, versus the height of 320px that was set in the SVG file (Example 1-8). Just like other image types, the SVG can be scaled to fit. Unlike other image types, the image will be drawn at whatever resolution is needed to fill the given size. The width of the image isn’t set in Example 2-3; since both height and width were set in the SVG file, the image will scale in proportion to the height.

Warning

Or at least, that’s how it usually works. Internet Explorer scales the width of the image area in proportion to the height you set, but doesn’t scale the actual drawing to fit into that area. There’s an easy solution, however; it involves the viewBox attribute that we’ll discuss in Chapter 8.

The second thing to note is that this is the animated SVG that is embedded. Declarative animation, including CSS animation and SVG/SMIL animation elements, runs as normal within SVG used as images—in browsers that support that animation type at all.

Warning

Or at least, that’s how it’s supposed to work.

MS Edge prior to version 15 (released April 2017) and Firefox prior to version 51 (released end of 2016) will not animate an SVG embedded as an image in a web page, even though CSS animation is supported in other SVG elements and SMIL-style animation elements in images are supported in Firefox!

And of course, older browsers do not support CSS animations, in SVG images or otherwise.

Why not use the scripted SVG animation from Example 2-2, which has better browser support? Because scripts do not run within images. That’s not a bug, it’s defined in the HTML spec: for security and performance reasons, files loaded as images can’t have scripted content.

There are some other important limitations of SVG used as images:

-

SVG in images won’t load external files (such as external stylesheets or embedded photos).

-

SVG in images won’t receive user interaction events (such as mouse clicks or hover movements).

-

SVG in images can’t be modified by the parent web page’s scripts or styles.

The limitations are the same if you reference an SVG image from within CSS, as a background image or other decorative graphic (an embedding option we’ll discuss more thoroughtly in Chapter 3).

Interactive Embedded SVG

If you want to use an external SVG file without (most of) the limitations of images, you can use an embedded <object>, replacing the <img> tag from Example 2-3 with the following:

<objectdata="animated-stoplight-scripted.svg"type="image/svg+xml"></object>

If you try this, you’ll note that the graphic doesn’t scale to fit like the image did. Again, that can be fixed with a viewBox attribute.

You can also add a fallback for older browsers, by including an <img> element as a child of the <object> element (with the src of the <img> referencing a raster image file), but beware that some older browsers (including most versions of Internet Explorer) will download both the SVG and the fallback.

You could also use an <embed> element or <iframe> with much the same effect. There is slightly different support in older browsers and no fallback option. As we discuss in Chapter 8, scaling behavior is also different for <iframe>, and less consistent between browsers.

Embedded objects can load external files, run scripts, and (with a little extra work and some security restrictions) use those scripts to interact with the main document. However, they are still separate documents, and they have separate stylesheets.

Warning

Just like an HTML file in an <iframe>, an embedded SVG object should be a fully interactive and accesible part of the main web page. However, they can be a little buggy in browsers. Test carefully, including keyboard interaction and screen reader exposure, if you’re embedding interactive SVG as an <object>.

There’s another option for fully interactive SVG: inline SVG in the HTML markup. Inline SVG has its own complications, but also many unique features.

Using SVG in HTML5 Documents

Perhaps the biggest step toward establishing SVG as the vector graphics language for the web came from the people who work on HTML standards.

When SVG was first proposed, as an XML language, it was expected that developers would insert SVG content directly into other XML documents—including XHTML—using XML namespaces to indicate the switch in content type. But most web authors weren’t interested in adopting the stricter syntax of XML when browsers rendered their HTML just fine.

Note

Modern HTML standards have developed after much conflict between the W3C (World Wide Web Consortium), promoting XHTML, and a parallel group, the WHATWG (Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group), promoting a “living standard” of HTML as developers and browsers used it. Both groups publish competing HTML specifications.

By the time the W3C decided that HTML5 was stable (in 2014), they had long yielded the XML debate. Authors can choose to use XML-compatible markup, but non-XML HTML is the default. Some discord between the two groups remains, but the net effect is that the latest HTML standards are (mostly) reflected in the latest browsers, and have been updated based on plenty of real-world experience.

With HTML developing separately from XML, it could have easily left SVG behind as another too-complicated coding language. Instead, the HTML5 standard (and the WHATWG living standard) welcomed the idea of SVG content mixed in with HTML markup, just without the need for XML namespaces.

By making SVG a de facto extension of HTML, the HTML working groups acknowledged that SVG was a fundamental part of the future of the web. This has had—and will continue to have—a huge impact on SVG.

HTML5 also introduced a number of new elements and attributes. The examples in this book will touch on some of the new HTML features but won’t go into too much detail; there are plenty of great resources on using HTML5 out there.

For using SVG, the most important thing to know about HTML5 is the <svg> element.

An <svg> element in HTML represents an SVG graphic to be included in the document. Unlike other ways of embedding SVG in web pages, the graphic isn’t contained in a separate file; instead, the SVG content is included directly within the HTML file, as child content of the <svg> element.

The integration isn’t one-way. It’s also possible to include HTML elements as children of SVG content. The SVG <foreignObject> element creates a layout box within an SVG drawing, in which an HTML document fragment can be displayed.

Again, the elements are in the same file, nested in the same DOM. The HTML elements must be marked with proper XML namespaces in a standalone SVG file, but the HTML parser automatically accepts HTML content inside <foreignObject>.

Warning

The <foreignObject> was never supported in Internet Explorer, although it is available in Microsoft Edge. Foreign objects in SVG are somewhat quirky in most web browsers, and are best used only for small amounts of content.

There are some key differences to keep in mind between using SVG code in HTML5 documents versus using it in standalone SVG files.

The most common area of difficulty is XML namespaces. The HTML parser ignores them.

If a web page is sent to the browser as an HTML file, namespace declarations have no effect. Namespace prefixes will be interpreted as part of the element or attribute name they precede, except for attributes like xlink:href and xml:lang, which are hardcoded into the parser. If the same markup is parsed by the XML parser (for example, if the web page is sent to the browser as an XHTML file), the resulting document object model may be different.

Tip

This book will try to use the most universally compatible syntax for SVG, and to identify any areas where you’re likely to have problems.

To further confuse matters, the DOM is sensitive to namespaces (as we warned earlier in the chapter). If you are dynamically creating SVG, you need to be aware of XML namespaces regardless of whether or not you’re working inside an HTML5 document.

Another important feature of SVG in HTML5 is that the <svg> element has a dual purpose: it is the parent element of the SVG graphic, but it also describes the box within the web page where that graphic should be inserted. You can position and style the box using CSS, the same as you would an <img> or <object> referencing an external SVG file.

Including SVG content within your primary HTML file enables scripts to manipulate both HTML and SVG content as one cohesive document. CSS styles inherit from HTML parent elements to SVG children. Among other benefits, this means that you can use dynamic CSS pseudoclass selectors—such as :hover or :checked—on HTML elements to control the appearance of child or sibling SVG content.

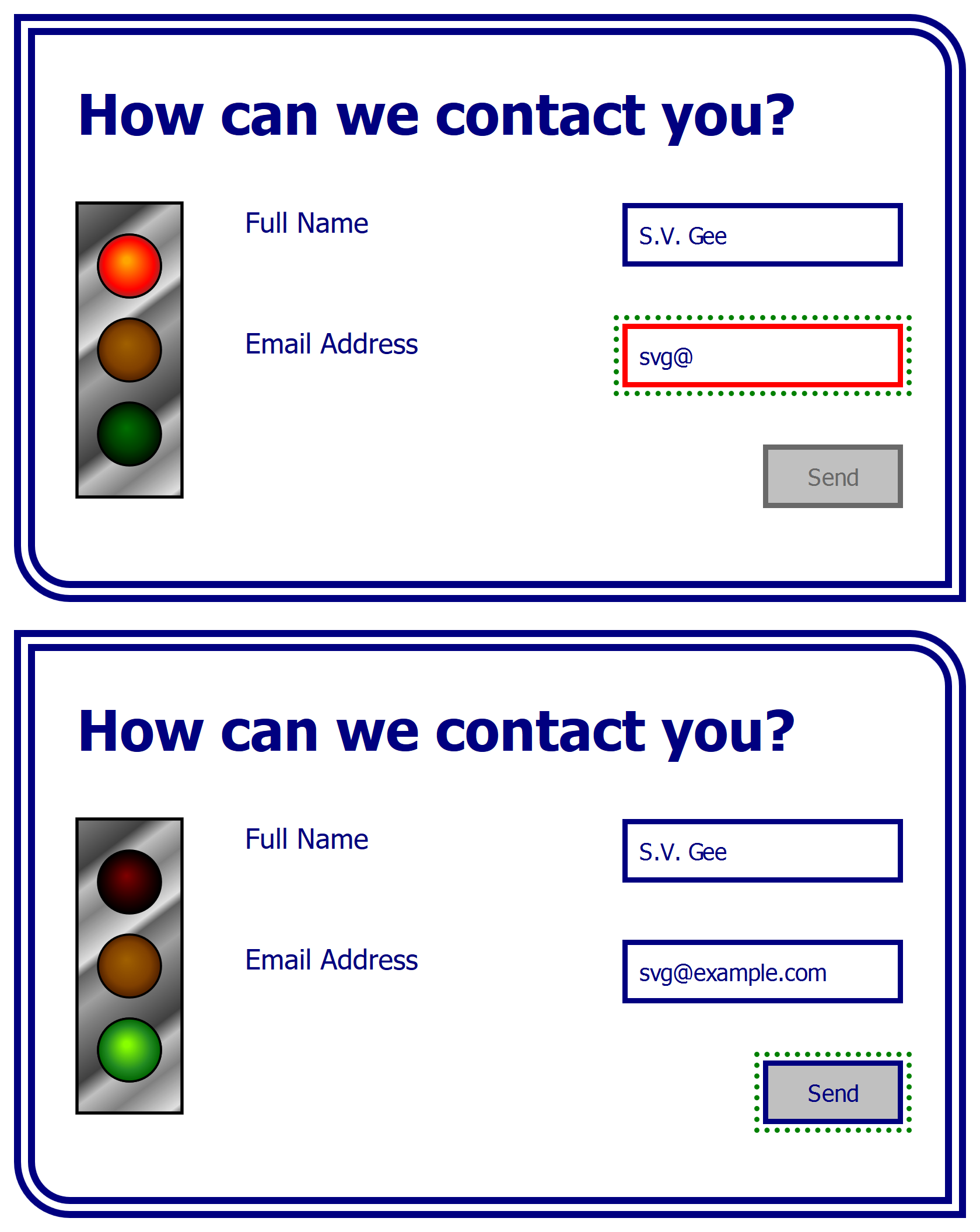

Example 2-4 uses HTML5 form validation and the :valid and :invalid pseudoclasses to turn an inline SVG version of the stoplight graphic into a warning light. If any of the user’s entries in the form are invalid, the stoplight will display red. If the form is valid and ready to submit, the light will be green. And finally, if the browser doesn’t support these pseudoclasses, the light will stay yellow regardless of what the user types.

Example 2-4. Controlling inline SVG with HTML form validation and CSS pseudoclasses

HTML markup:

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>Inline SVG within HTML</title><linkrel="stylesheet"type="text/css"href="svg-inline-styles.css"></head><body><formid="contactForm"method="post"><h1>How can we contact you?</h1><svgwidth="140"height="320"viewBox="20 20 140 320"preserveAspectRatio="xMinYMin meet"aria-label="stoplight"role="img"><defs><circleid="light"cx="70"r="30"/></defs><rectx="20"y="20"width="100"height="280"fill="url(gradients.svg#metal) silver"stroke="black"stroke-width="3"/><gstroke="black"stroke-width="2"><gclass="red light"><usexlink:href="#light"y="80"fill="url(gradients.svg#red-light-off) maroon"/><useclass="lit"xlink:href="#light"y="80"fill="url(gradients.svg#red-light-on) red"visibility="hidden"/></g><gclass="yellow light"><usexlink:href="#light"y="160"fill="url(gradients.svg#yellow-light-off) #705008"/><useclass="lit"xlink:href="#light"y="160"fill="url(gradients.svg#yellow-light-on) yellow"/></g><gclass="green light"><usexlink:href="#light"y="240"fill="url(gradients.svg#green-light-off) #002804"/><useclass="lit"xlink:href="#light"y="240"fill="url(gradients.svg#green-light-on) lime"visibility="hidden"/></g></g></svg><label><inputtype="text"name="CustomerName"required/>Full Name</label><label><inputtype="email"name="CustomerEmail"required/>Email Address</label><buttontype="submit">Send</button></form></body></html>

A linked stylesheet contains the CSS, both for the HTML form content and for the inline SVG.

The body of the web page contains a single

<form>element. The form contains a heading and the input elements, but also the SVG that will give feedback about the user’s entries.

Much of the SVG code should look familiar by now; changes are described next.

The SVG code is a modified version of the stoplight SVG code we used in the CSS-animated and JS-animated versions of the stoplight (Examples 1-8 and 2-2).

The attributes on the <svg> element have been changed to fit the new context. For one thing, there is no xmlns. For a pure HTML document, no namespaces are required (for XHTML, they would be); the HTML5 parser knows to switch to SVG mode when it reaches an opening <svg> tag.

The width and height attributes provide a default size for the SVG; the final size will be controlled by CSS. Two new attributes (viewBox and preserveAspectRatio) control the scaling of the graphic; we’ll talk more about them in Chapter 8. For now, just trust that these are the magic that make the SVG drawing scale to fit the dimensions we give it within the HTML page.

Tip

The particular attribute values in Example 2-4 also ensure that the graphic will be drawn flush against the top-left edges of the SVG area, making it line up neatly with the heading text.

The aria-label and role attributes on the <svg> tell screen readers to treat the SVG in the same way as an <img> with alt="stoplight"; we’ll talk more about ARIA in Chapter 17. The actual validation information about the form inputs will be communicated directly to the screen reader by the browser.

Inside the SVG, the main change is that we’ve removed all the gradient definitions and put them in a separate file, gradients.svg. As mentioned in Chapter 1, most browsers do not support this, so you probably would not want to do this in production; it’s used here so we can focus on the new code.

Here, we use the fact that fill can declare fallback colors, in case there’s a problem with URL references. We’ll talk more about the fallback syntax in Chapter 12. Browsers that don’t show the gradients use the solid colors instead. It’s not pretty, but it’s functional.

We’ve also changed the visibility presentation attributes. In other examples, we’ve left the red light on by default, but now we only want the red light to show if it is meaningful. The visibility="hidden" presentation attributes on the red and green lights ensure that they display in the “off” state by default. The yellow light is by default “lit.”

The rest of the code describes the form itself. HTML5 form validation attributes have been used that will trigger invalid states:

-

Both fields are

required, and so will be invalid when empty. -

The second field is of

type="email"; browsers that recognize this type will mark it as invalid unless the content meets the standard format of an email address.

Warning

The :valid and :invalid pseudoclass selectors are supported on <form> elements (as opposed to individual <input> elements) in Firefox (versions 13+), WebKit/Safari (version 9+), and Blink browsers (Chrome and Opera, since early 2015). Microsoft Edge (as of EdgeHTML version 15) and older versions of other browsers display the indeterminate yellow light.

For more universal browser support, you could use a script to listen for changes in focus between input elements, and set regular CSS classes on the <form> element based on whether any of the input elements are in the invalid state. The stylesheet would also need to be modified so that these classes also control the SVG styles.

Since this isn’t a book about JavaScript, we’re not going to write out that script in detail. Once again, nothing about the script would be SVG-specific. The SVG effects are controlled entirely by the (pseudo-)classes on the parent <form>.

The styles that control the appearance of both the form and the SVG are in a separate file, linked from within the HTML <head>. Example 2-5 presents the CSS code that controls the interaction.

Example 2-5. CSS stylesheet for the code in Example 2-4

CSS Styles: svg-inline-styles.css

@charset"UTF-8";/* Form styles */form{display:block;max-width:30em;padding:1.5em;overflow:auto;border:double12px;border-radius:02em;color:navy;font-family:sans-serif;}h1{margin:001em;}label,button{display:block;clear:right;padding:003em;}input,button{float:right;min-width:6em;max-width:70%;padding:0.5em;color:inherit;border:solid;}button{background:silver;}input:invalid{border-color:red;box-shadow:none;/* override browser defaults */}input:focus,button:focus{outline:greendotted;outline-offset:2px;}form:invalidbutton[type="submit"]{color:dimGray;}/* SVG styles */formsvg{float:left;width:6em;height:12em;max-width:25%;max-height:80vh;overflow:visible;}form:valid.green.lit{/* If the validator thinks all form elements are ok,the green light will display */visibility:visible;}form:invalid.red.lit{/* If the validator detects a problem in the form,the red light will display */visibility:visible;}form:valid.yellow.lit,form:invalid.yellow.lit{/* If either validator class is recognized,turn off the yellow light */visibility:hidden;}

The first batch of style rules defines the appearance of the HTML form elements, including using the :invalid selector to style individual inputs that cannot be submitted as-is, and :focus selectors to identify the active field.

The <svg> element itself is styled as a floated box with a standard width and height that will shrink on small screens. The overflow is set to visible to prevent the strokes of the rectangle from being clipped, now that the rectangle has been moved flush against the edge of the SVG.

The remaining rules control the visibility of the lights, taking advantage of the fact that CSS rules override the defaults set with presentation attributes. If the form matches the :valid selector, the bright green light is revealed; if it matches :invalid, the bright red light is displayed. Finally, if either of those selectors is recognized by the browser, the illuminated version of the yellow light is hidden. If the selectors aren’t recognized (or if the CSS doesn’t load), the presentation attributes ensure that only the yellow light is lit.

Figure 2-3 shows the web page in action: when the form is invalid (because of a problem with the email field) versus when it is complete and showing the green light. The screenshots are from Firefox, which at the time of writing is the only browser that supports both the pseudoclasses and SVG gradients from external files.

This demo uses familiar CSS approaches (classes and pseudoclasses) to style SVG in a dynamic way. But this is only the beginning of how SVG and CSS can be integrated.

Figure 2-3. A web page using inline SVG to enhance form validation feedback

Using SVG with CSS3

CSS has also advanced considerably since SVG 1.1 was introduced. The core CSS specification was updated to version 2.1, and finalized in 2011. But already, work had begun on a variety of CSS modules, each focusing on specific topics. There is no single CSS3 specification, but the many modules are collectively known as CSS level 3.

Many of the original CSS3 features are widely implemented in web browsers, and you can use them without problem when designing SVG for the web. SVG tools that still rely exclusively on the SVG 1.1 specifications, however, may not support them. Nonetheless, thanks to CSS’s error-resistant syntax, the old software shouldn’t break completely; it should just ignore the parts it does not understand.

Some of the newer specifications, although widely implemented, are still not entirely stable. Others are very experimental.

The W3C working group periodically publishes an informal “snapshot” of the state of CSS standards, with links to the modules. The latest version is at https://www.w3.org/TR/CSS/.

The new CSS modules include many graphical effects—such as masking, filters, and transformations—that are direct extensions of features from SVG. These standards replace the corresponding SVG definitions, allowing the same syntax to be used for all CSS-styled content. There are no competing chapters in SVG 2. Support for these effects in browsers is more erratic (we’ll discuss the details in the relevant chapters); many bugs remain, but they are slowly being squashed.

Not all aspects of CSS3 were developed in collaboration with SVG.

Other new CSS features introduced similar-but-different graphical features that put CSS in direct competition with SVG for some simple vector graphics. Whenever this book discusses a feature of SVG that has a CSS equivalent, we’ll highlight the similarities and differences using “CSS Versus SVG” notes like this:

The relationship between CSS and SVG is so complex, and so important, that we’ve given it a separate chapter. Chapter 3 will look at the ways CSS can be used to enhance SVG, and SVG can be used to enhance CSS. It will also consider the ways in which CSS has started to replace SVG for simple graphics like the stoplight example we’ve been using so far.

Summary: SVG and the Web

This chapter aimed to provide a big picture of SVG on the web, considering both the role of SVG on the web and the way it can complement (and be complemented by) other web technologies.

The web is founded on the intersection of many different coding languages and standards, each with its own role to play. For the most part, web authors are encouraged to separate their web page code into the document text and structure (HTML), its styles and layout (CSS), and its logic and functionality (JavaScript).

SVG redefines this division to support documents where layout and graphical appearance are a fundamental part of the structure and meaning. It provides a way to describe an image as a structured document, with distinct elements defined by their geometric presentation and layout, that can be styled with CSS and modified with JavaScript.

The SVG standard has developed in fits and starts. The practical use of SVG on the web is only just starting to achieve its potential. There are still countless quirks and areas of cross-browser incompatibility, which we’ll mention whenever possible in the rest of the book. Hopefully, the messy history of SVG and the interdependent web standards has reinforced the fact that the web, in general, is far from a perfect or complete system, and SVG on the web is still relatively new.

The goal of this book is to help you work with SVG on the web, focusing on the way SVG is currently supported in web browsers, rather than the way the language was originally defined. In many cases, this will include warnings about browser incompatibilities and suggestions of workarounds. However, support for SVG may have changed by the time you read this, so open up your web browser(s) and test out anything you’re curious about.