Preface

The quandary of information technology (IT) is that everything changes. It’s inevitable. The continents of high technology drift on a daily basis right underneath our feet. This is particularly true with regard to computer security. Offensive tactics evolve as attackers find new ways to subvert our machines, and defensive tactics progress to respond in kind. As an IT professional, you’re faced with a choice: You can proactively educate yourself about the inherent limitations of your security tools … or you can be made aware of their shortcomings the hard way, after you’ve suffered at the hands of an intruder.

In this book, I don the inimical Black Hat in hopes that, by viewing stealth technology from an offensive vantage point, I can shed some light on the challenges that exist in the sphere of incident response. In doing so, I’ve waded through a vast murky swamp of poorly documented, partially documented, and undocumented material. This book is your opportunity to hit the ground running and pick up things the easy way, without having to earn a lifetime membership with the triple-fault club.

My goal herein is not to enable bad people to go out and do bad things. The professional malware developers that I’ve run into already possess an intimate knowledge of anti-forensics (who do you think provided material and inspiration for this book?). Instead, this collection of subversive ideas is aimed squarely at the good guys. My goal is both to make investigators aware of potential blind spots and to help provoke software vendors to rise and meet the massing horde that has appeared at the edge of the horizon. I’m talking about advanced persistent threats (APTs).1

APTs: Low and Slow, Not Smash and Grab

The term “advanced persistent threat” was coined by the Air Force in 2006.2 An APT represents a class of attacks performed by an organized group of intruders (often referred to as an “intrusion set”) who are both well funded and well equipped. This particular breed of Black Hat executes carefully targeted campaigns against high-value installations, and they relentlessly assail their quarry until they’ve established a solid operational foothold. Players in the defense industry, high-tech vendors, and financial institutions have all been on the receiving end of APT operations.

Depending on the defensive measures in place, APT incidents can involve more sophisticated tools, like custom zero-day exploits and forged certificates. In extreme cases, an intrusion set might go so far as to physically infiltrate a target (e.g., respond to job postings, bribe an insider, pose as a telecom repairman, conduct breaking and entry (B&E), etc.) to get access to equipment. In short, these groups have the mandate and resources to bypass whatever barriers are in place.

Because APTs often seek to establish a long-term outpost in unfriendly territory, stealth technology plays a fundamental role. This isn’t your average Internet smash-and-grab that leaves a noisy trail of binaries and network packets. It’s much closer to a termite infestation; a low-and-slow underground invasion that invisibly spreads from one box to the next, skulking under the radar and denying outsiders any indication that something is amiss until it’s too late. This is the venue of rootkits.

1 What’s New in the Second Edition?

Rather than just institute minor adjustments, perhaps adding a section or two in each chapter to reflect recent developments, I opted for a major overhaul of the book. This reflects observations that I received from professional researchers, feedback from readers, peer comments, and things that I dug up on my own.

Out with the Old, In with the New

In a nutshell, I added new material and took out outdated material. Specifically, I excluded techniques that have been proved less effective due to technological advances. For example, I decided to spend less time on bootkits (which are pretty easy to detect) and more time on topics like shellcode and memory-resident software. There were also samples from the first edition that work only on Windows XP, and I removed these as well. By popular demand, I’ve also included information on rootkits that reside in the lower rings (e.g., Ring – 1, Ring – 2, and Ring – 3).

The Anti-forensics Connection

While I was writing the first edition, it hit me that rootkits were anti-forensic in nature. After all, as The Grugq has noted, anti-forensics is geared toward limiting both the quantity and quality of forensic data that an intruder leaves behind. Stealth technology is just an instance of this approach: You’re allowing an observer as little indication of your presence as possible, both at run time and after the targeted machine has been powered down. In light of this, I’ve reorganized the book around anti-forensics so that you can see how rootkits fit into the grand scheme of things.

2 Methodology

Stealth technology draws on material that resides in several related fields of investigation (e.g., system architecture, reversing, security, etc.). In an effort to maximize your return on investment (ROI) with regard to the effort that you spend in reading this book, I’ve been forced to make a series of decisions that define the scope of the topics that I cover. Specifically, I’ve decided to:

Focus on anti-forensics, not forensics.

Focus on anti-forensics, not forensics.

Target the desktop.

Target the desktop.

Put an emphasis on building custom tools.

Put an emphasis on building custom tools.

Include an adequate review of prerequisite material.

Include an adequate review of prerequisite material.

Demonstrate ideas using modular examples.

Demonstrate ideas using modular examples.

Focus on Anti-forensics, Not Forensics

A book that describes rootkits could very well end up being a book on forensics. Naturally, I have to go into some level of detail about forensics. Otherwise, there’s no basis from which to talk about anti-forensics. At the same time, if I dwell too much on the “how” and “why” of forensics (which is awfully tempting, because the subject area is so rich), I won’t have any room left for the book’s core material. Thus, I decided to touch on the basic dance steps of forensic analysis only briefly as a launch pad to examine counter-measures.

I’m keenly aware that my coverage may be insufficient for some readers. For those who desire a more substantial treatment of the basic tenets of forensic analysis, there are numerous resources available that delve deeper into this topic.

Target the Desktop

In the information economy, data is the coin of the realm. Nations rise and fall based on the integrity and accuracy of the data their leaders can access. Just ask any investment banker, senator, journalist, four-star general, or spy.3

Given the primacy of valuable data, one might naïvely assume that foiling attackers would simply be a matter of “protecting the data.” In other words, put your eggs in a basket, and then watch the basket.

Security professionals like Richard Bejtlich have addressed this mindset.4 As Richard notes, the problem with just protecting the data is that data doesn’t stand still in a container; it floats around the network from machine to machine as people access it and update it. Furthermore, if an authorized user can access data, then so can an unauthorized intruder. All an attacker has to do is find a way to pass himself off as a legitimate user (e.g., steal credentials, create a new user account, or piggyback on an existing session).

Bejtlich’s polemic against the “protect the data” train of thought raises an interesting point: Why attack a heavily fortified database server, which is being carefully monitored and maintained, when you could probably get at the same information by compromising the desktop machine of a privileged user? Why not go for the low-hanging fruit?

In many settings, the people who access sensitive data aren’t necessarily careful about security. I’m talking about high-level executives who get local admin rights by virtue of their political clout or corporate rainmakers who are granted universal read–write privileges on the customer accounts database, ostensibly so they can do their jobs. These people tend to wreck their machines as a matter of course. They install all sorts of browser add-ins and toy gadgets. They surf with reckless abandon. They turn their machines into a morass of third-party binaries and random network sessions, just the sort of place where an attacker could blend in with the background noise.

In short, the desktop is a soft target. In addition, as far as the desktop is concerned, Microsoft owns more than 90 percent of the market. Hence, throughout this book, practical examples will target the Windows operating system running on 32-bit Intel hardware.

Put an Emphasis on Building Custom Tools

The general tendency of many security books is to offer a survey of the available tools, accompanied by comments on their use.

With regard to rootkits, however, I think that it would be a disservice to you if I merely stuck to widely available tools. This is because public tools are, well … public. They’ve been carefully studied by the White Hats, leading to the identification of telltale signatures and the development of automated countermeasures. The ultimate packing executable (UPX) executable packer and Zeus malware suite are prime examples of this. The average forensic investigator will easily be able to recognize the artifacts that these tools leave behind.

In light of this, the best way to keep a low profile and minimize your chances of detection is to use your own tools. It’s not enough simply to survey existing technology. You’ve got to understand how stealth technology works under the hood so that you have the skillset necessary to construct your own weaponry. This underscores the fact that some of the more prolific Black Hats, the ones you never hear about, are also accomplished developers.

Over the course of its daily operation, the average computer spits out gigabytes of data in one form or another (log entries, registry edits, file system changes, etc.). The only way that an investigator can sift through all this data and maintain a semblance of sanity is to rely heavily on automation. By using custom software, you’re depriving investigators of the ability to rely on off-the-shelf tools and are dramatically increasing the odds in your favor.

Include an Adequate Review of Prerequisite Material

Dealing with system-level code is a lot like walking around a construction site for the first time. Kernel-mode code is very unforgiving. The nature of this hard-hat zone is such that it shelters the cautious and punishes the foolhardy. In these surroundings, it helps to have someone who knows the terrain and can point out the dangerous spots. To this end, I put a significant amount of effort in covering the finer points of Intel hardware, explaining obscure device-driver concepts, and dissecting the appropriate system-level application programming interfaces (APIs). I wanted to include enough background material so that you don’t have to read this book with two other books in your lap.

Demonstrate Ideas Using Modular Examples

This book isn’t a brain-dump of an existing rootkit (though such books exist). This book focuses more on transferable ideas.

The emphasis of this book is on learning concepts. Hence, I’ve tried to break my example code into small, easy-to-digest sample programs. I think that this approach lowers the learning threshold by allowing you to focus on immediate technical issues rather than having to wade through 20,000 lines of production code. In the source code spectrum (see Figure 1), the examples in this book would probably fall into the “Training Code” category. I build my sample code progressively so that I provide only what’s necessary for the current discussion at hand, and I keep a strong sense of cohesion by building strictly on what has already been presented.

Figure 1

Over years of reading computer books, I’ve found that if you include too little code to illustrate a concept, you end up stifling comprehension. If you include too much code, you run the risk of getting lost in details or annoying the reader. Hopefully I’ve found a suitable middle path, as they say in Zen.

3 This Book’s Structure

As I mentioned earlier, things change. The battlefront is shifting. In my opinion, the bad guys have found fairly effective ways to foil disk analysis and the like, which is to say that using a postmortem autopsy is a bit passé; the more sophisticated attackers have solved this riddle. This leaves memory analysis, firmware inspection, and network packet capture as the last lines of defense.

From the chronological perspective of a typical incident response, I’m going to present topics in reverse. Typically, an investigator will initiate a live response and then follow it up with a postmortem (assuming that it’s feasible to power down the machine). I’ve opted to take an alternate path and follow the spy-versus-spy course of the arms race itself, where I introduce tactics and countertactics as they emerged in the field. Specifically, this book is organized into four parts:

Part I: Foundations

Part I: Foundations

Part II: Postmortem

Part II: Postmortem

Part III: Live Response

Part III: Live Response

Part IV: Summation

Part IV: Summation

Once we’ve gotten the foundations out of the way I’m going to start by looking at the process of postmortem analysis, which is where anti-forensic techniques originally focused their attention. Then the book will branch out into more recent techniques that strive to undermine a live response.

Part I: Foundations

Part I lays the groundwork for everything that follows. I begin by offering a synopsis of the current state of affairs in computer security and how anti-forensics fits into this picture. Then I present an overview of the investigative process and the strategies that anti-forensic technology uses to subvert this process. Part I establishes a core framework, leaving specific tactics and implementation details for later chapters.

Part II: Postmortem

The second part of the book covers the analysis of secondary storage (e.g., disk analysis, volume analysis, file system analysis, and analysis of an unknown binary). These tools are extremely effective against an adversary who has modified existing files or left artifacts of his own behind. Even in this day and age, a solid postmortem examination can yield useful information.

Attackers have responded by going memory resident and relying on multistage droppers. Hence, another area that I explore in Part II is the idea of the Userland Exec, the development of a mechanism that receives executable code over a network connection and doesn’t rely on the native OS loader.

Part III: Live Response

The quandary of live response is that the investigator is operating in the same environment that he or she is investigating. This means that a knowledgeable intruder can interfere with the process of data collection and can feed misinformation to the forensic analyst. In this part of the book, I look at root-kit tactics that attackers have used in the past both to deny information to the opposition at run time and to allay the responder’s suspicions that something may be wrong.

Part IV: Summation

If you’re going to climb a mountain, you might as well take a few moments to enjoy the view from the peak. In this final part, I step back from the minutiae of rootkits to view the subject from 10,000 feet. For the average forensic investigator, hindered by institutional forces and limited resources, I’m sure the surrounding landscape looks pretty bleak. In an effort to offer a ray of hope to these beleaguered White Hats perched with us on the mountain’s summit, I end the book by discussing general strategies to counter the danger posed by an attacker and the concealment measures he or she uses.

It’s one thing to point out the shortcomings of a technology (heck, that’s easy). It’s another thing to acknowledge these issues and then search for constructive solutions that realistically address them. This is the challenge of being a White Hat. We have the unenviable task of finding ways to plug the holes that the Black Hats exploit to make our lives miserable. I feel your pain, brother!

4 Audience

Almost 20 years ago, when I was in graduate school, a crusty old CEO from a local bank in Cleveland confided in me that “MBAs come out of business school thinking that they know everything.” The same could be said for any training program, where students mistakenly assume that the textbooks they read and the courses they complete will cover all of the contingencies that they’ll face in the wild. Anyone who’s been out in the field knows that this simply isn’t achievable. Experience is indispensable and impossible to replicate within the confines of academia.

Another sad truth is that vendors often have a vested interest in overselling the efficacy of their products. “We’ve found the cure,” proudly proclaims the marketing literature. I mean, who’s going to ask a customer to shell out $100,000 for the latest whiz-bang security suite and then stipulate that they still can’t have peace of mind?

In light of these truisms, this book is aimed at the current batch of security professionals entering the industry. My goal is to encourage them to understand the limits of certain tools so that they can achieve a degree of independence from them. You are not your tools; tools are just labor-saving devices that can be effective only when guided by a battle-tested hand.

Finally, security used to be an obscure area of specialization: an add-on feature, if you will, an afterthought. With everyone and his brother piling onto the Internet, however, this is no longer the case. Everyone needs to be aware of the need for security. As I watch the current generation of users grow up with broadband connectivity, I can’t help but cringe when I see how brazenly many of these youngsters click on links and activate browser plug-ins. Oh, the horror, … the horror. I want to yell: “Hey, get off that social networking site! What are you? Nuts?” Hence, this book is also for anyone who’s curious enough (or perhaps enlightened enough) to want to know why rootkits can be so hard to eradicate.

5 Prerequisites

Stealth technology, for the most part, targets system-level structures. Since the dawn of UNIX, the C programming language has been the native tongue of conventional operating systems. File systems, thread schedulers, hardware drivers; they’re all implemented in C. Given that, all of the sample code in this book is implemented using a mixture of C and Intel assembler.

In the interest of keeping this tome below the 5-pound limit, I have assumed that readers are familiar with both of these languages. If this is not the case, then I’d recommend picking up one of the many books available on these specific languages.

6 Conventions

This book is a mishmash of source code, screen output, hex dumps, and hidden messages. To help keep things separate, I’ve adopted certain formatting rules.

The following items are displayed using the Letter Gothic font:

File names.

File names.

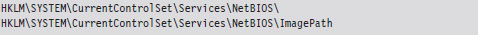

Registry keys.

Registry keys.

Programmatic literals.

Programmatic literals.

Screen output.

Screen output.

Source code.

Source code.

Source code is presented against a gray background to distinguish it from normal text. Portions of code considered especially noteworthy are highlighted using a black background to allow them to stand out.

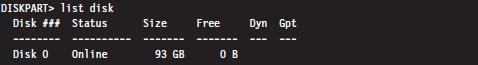

Screen output is presented against a DOS-like black background.

Registry names have been abbreviated according to the following standard conventions.

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE = HKLM

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE = HKLM

HKEY_CURRENT_USER = HKCU

HKEY_CURRENT_USER = HKCU

Registry keys are indicated by a trailing backslash. Registry key values are not suffixed with a backslash.

Words will appear in italic font in this book for the following reasons:

To define new terms.

To define new terms.

To place emphasis on an important concept.

To place emphasis on an important concept.

To quote another source.

To quote another source.

To cite a source.

To cite a source.

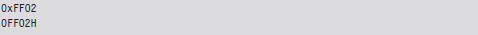

Numeric values appear throughout the book in a couple of different formats. Hexadecimal values are indicated by either prefixing them with “0x” or appending “H” to the end. Source code written in C tends to use the former, and IA-32 assembly code tends to use the latter.

Binary values are indicated either explicitly or implicitly by appending the letter “B.” You’ll see this sort of notation primarily in assembly code.

7 Acknowledgments

The security community as a whole owes a debt of gratitude to the pioneers who generously shared what they discovered with the rest of us. I’m talking about researchers such as David Aitel, Jamie Butler, Maximiliano Cáceres, Loïc Duflot, Shawn Embleton, The Grugq, Holy Father, Nick Harbour, John Heasman, Elias Levy, Vinnie Liu, Mark Ludwig, Wesley McGrew, H.D. Moore, Gary Nebbett, Matt Pietrek, Mark Russinovich, Joanna Rutkowska, Bruce Schneier, Peter Silberman, Sherri Sparks, Sven Schreiber, Arrigo Triulzi, and countless others. Much of what I’ve done herein builds on the public foundation of knowledge that these people left behind, and I feel obliged to give credit where it’s due. I only hope this book does the material justice.

Switching focus to the other side of the fence, professionals like Richard Bejtlich, Michael Ligh, and Harlan Carvey have done an outstanding job building a framework for dealing with incidents in the field. Based on my own findings, I think that the “they’re all idiots” mindset that crops up in anti-forensics is awfully naïve. Underestimating the aptitude or tenacity of an investigator is a dubious proposition. An analyst with the resources and discipline to follow through with a rigorous methodology will prove a worthy adversary to even the most skilled attacker.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

I owe a debt of gratitude to a server administrator named Alex Keller, whom I met years ago at San Francisco State University. The half-day that I spent watching him clean up our primary domain controller was time well spent. Pen and paper in hand, I jotted down notes furiously as he described what he was doing and why. With regard to live incident response, I couldn’t have asked for a better mentor.

Thanks again Alex for going way beyond the call of duty, for being decent enough to patiently pass on your tradecraft, and for encouraging me to learn more. SFSU is really lucky to have someone like you aboard.

Then, there are distinguished experts in related fields that take the time to respond to my queries and generally put up with me. In particular, I’d like to thank Noam Chomsky, Norman Matloff, John Young, and George Ledin.

Last, but not least, I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to all of the hardworking individuals at Jones & Bartlett Learning whose efforts made this book possible; Tim Anderson, Senior Acquisitions Editor; Amy Rose, Production Director; and Amy Bloom, Managing Editor.

Θ(ex),

Bill Blunden

www.belowgotham.com

1. “Under Cyberthreat: Defense Contractors,” BusinessWeek. July 6, 2009.

2. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2010/01/what-is-apt-and-what-does-it-want.html.

3. Michael Ruppert, Crossing the Rubicon, New Society Publishers, 2004.

4. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2009/10/protect-data-idiot.html.