Chapter 16 The Tao of Rootkits

In organizations like the CIA, it’s standard operating procedure for security officers to periodically monitor people with access to sensitive information even if there is no explicit reason to suspect them.

The same basic underlying logic motivates preemptive security assessments in information technology (IT).1 Don’t assume a machine is secure simply because you’ve slapped on a group policy, patched it, and installed the latest anti-virus signatures. Oh no, you need to roll your sleeves up and actually determine if someone has undermined the integrity of the system. Just because a machine seems to be okay doesn’t mean that it hasn’t acquired an uninvited guest.

As an attacker, to survive this sort of aggressive approach you’ll need to convince the analyst that nothing is wrong, so that he can fill out his report and move on to the next machine (“nothing wrong, boss, no one here but us sheep”). You need to deprive him of information, which in this case would be indicators that the machine is compromised. This calls for low-and-slow anti-forensics.

In this chapter, we step back from the trees to view the forest, so to speak. We’re going to pull it all together to see how the various forensic and anti-forensic techniques fit in the grand scheme of things.

The Dancing Wu Li Masters

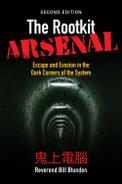

Let’s begin by reviewing the intricate dance of attack and counterattack as it has evolved over time. In doing so, we’ll be in a position where we can better appreciate the recurring themes that appear (see Figure 16.1).

In the early days, a rootkit might be something as simple as a bundle of modified system programs or a file system patch (e.g., a bootkit). Postmortem disk analysis proved to be an acceptable defense against this kind of attack, and it still is. The investigator arrives on scene, creates a forensic duplicate of disk storage, and sends it through a battery of procedures that will ultimately digest the image into a set of files. Assuming the availability of a baseline snapshot, the investigator can take this set of files and use a cross-time diff to identify files that have been altered or introduced by an attacker.

Figure 16.1

Despite the emergence of hash-collision attacks, there’s always the threat of raw binary comparison. If you’ve altered a known system file or installed a new executable, eventually it will be unearthed.

Historically speaking, attackers then tried to conceal their tools by moving them to areas where they wouldn’t be recognized as files. The caveat of this approach is that, somewhere along the line, there has to be an executable (e.g., an altered boot sector) to load and launch the hidden tools, and this code must exist out in the open. As Jesse Kornblum observed, a rootkit may want to hide, but it also needs to execute. The forensic investigator will take note of this conspicuous executable and dissect it using the procedures of static analysis.

The attacker can construct the initiating executable in such a way to make it more difficult to inspect. Using a layered strategy, he can minimize the size of his footprint by implementing the executable as the first phase of a multistage loader. This loading code can be embedded in an existing file (using an infector engine like Mistfall) to make it less conspicuous and also armored to deter examination.

Although this may put a short-term halt to static analysis, at some point the injected code will need to execute. Then the malicious payload will, at least partially, reveal itself, and the investigator can wield the tools of runtime analysis to peek under the hood and see what the code does when it’s launched.

To make life more difficult for the investigator, the attacker can fortify his code using techniques that are typically used by creators of software protection suites to foil reverse engineering and safeguard their intellectual property (e.g., obfuscation, dynamic encoding, anti-debugger landmines, etc.).

When a Postmortem Isn’t Enough

Some people would argue that once the investigator finds a suspicious-looking file, the game is already lost. The goal of a rootkit is to remain under the radar, and the best way to counter an exhaustive postmortem disk analysis is to stay memory resident such that the rootkit never touches the disk to begin with. Such is the power of data source elimination.

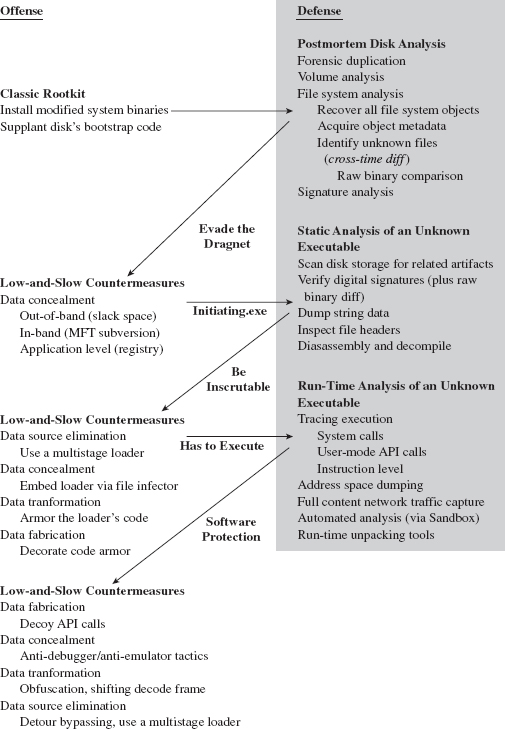

In this case, the investigator can conduct a live incident response while the machine is still running (see Figure 16.2). If the attacker’s code was loaded through normal channels or uses existing APIs to get work done, an audit trail will be generated.

Figure 16.2

Attackers can respond by deploying custom loading programs that allow them to situate modules in memory without having to go through the official channels. To prevent their payloads from being recognized as PE files (by memory-carving tools and the like), an attacker can implement them as shellcode or a virtual machine bytecode.

Even then, Korblum’s rootkit paradox can still come back to haunt us. If a rootkit isn’t registered as a legitimate binary, it will need to modify the system somehow to intercept a thread’s execution path and scrounge CPU time (so that it can run). This is where security packages like HookSafe come into play. The White Hats can always monitor regions of memory that are candidates for rootkit subversion and sound the alarm when an anomaly is detected.

The best way to foil these security tools is to subvert the target system in such a way that it doesn’t leave telltale signs of modification. This is the driving motivation behind the current generation of out-of-band rootkits. These cutting-edge implementations migrate to a vantage point that lies outside the targeted system so that they can extract useful information and communicate with the outside without having to hook into the operating system itself. The rootkits are essentially stand-alone microkernels.

The Battlefield Shifts Again

Let’s assume the attacker has gone completely out-of-band and is operating in a manner that places the rootkit outside of the targeted OS. In this scenario, the defender can still take some solace in a modified version of Kornblum’s paradox:

Rootkits want to remain hidden.

Rootkits want to remain hidden.

Rootkits need to communicate.

Rootkits need to communicate.

Hide all you want on the local machine; if the rootkit is going to communicate, then the corresponding network traffic can be captured and analyzed. Deep packet inspection may indicate the presence of a rootkit.

If traffic is heavy for a given network protocol (e.g., HTTP), an attacker may be able to hide in a crowd by tunneling his data inside of this protocol. If that’s not enough, and the attacker can subvert a nearby router or switch, he can attain an even higher degree of stealth by using a passive covert channel.

16.1 Core Stratagems

As time forges ahead, execution environments evolve, and kernel structures change. Whereas the details of rootkit implementation may assume different forms, the general principles used to guide their design do not. Some computer books direct all their attention to providing a catalogue of current tools and quickly fade into obsolescence. Thus, there’s probably something to be said for working toward establishing a formal system that stands apart from technical minutiae.

The intent of my advice is to transcend any particular operating system or hardware platform and focus on recurring themes that pertain to rootkits in general. To this end, I’ll offer a series of observations that you might find useful. I can’t guarantee that my recommendations will be perfect or even consistent. Naturally, there’s no exact formula. Working with rootkits is still somewhat of an art more than a science. The discipline lies at the intersection of a number of related domains (e.g., reversing, security, device drivers, etc.). The best way to understand the process is through direct exposure so that you can develop your own instincts. Reading a description of the process is no replacement for firsthand experience, hence this chapter’s opening quote.

Respect Your Opponent

To be on the safe side, I would strongly discourage the “they’re all idiots” mindset. The forensic investigators that I’ve had contact with have always been dedicated, competent experts who are constantly striving to hone their skills. To see this for yourself, check out the publications of the Shadowserver Foundation2 or the Information Warfare Monitor.3 It’s a dubious proposition simply to dismiss the investigator. To assess properly who you’re dealing with, in an effort to devise a game plan, you need to recognize and acknowledge his or her strengths. In short, you need to view him or her with a healthy degree of respect.

Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique

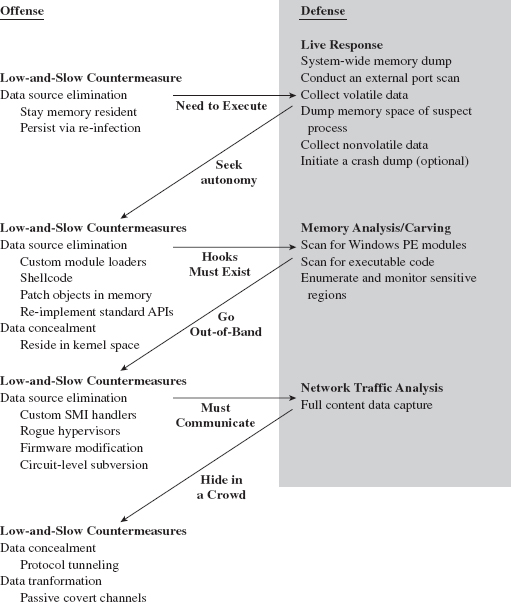

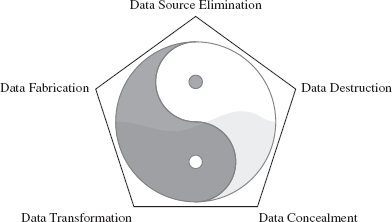

A few years back, while I was researching the material for this book’s first edition, I focused almost exclusively on traditional rootkits: tools that operated by actively concealing objects that already existed (e.g., files, executing processes, network connections, etc.). What I came to realize was that this was just one expression of stealth technology (see Figure 16.3). Joanna Rutkowska’s work on stealth malware was an epiphany of sorts for me.4 Backing up a bit further, I saw that stealth technology was fundamentally anti-forensic in nature (see Figure 16.3). By hiding something, you’re seeking to limit both the quantity and the quality of the forensic data that you leave behind.

Figure 16.3

The secret Gung Fu technique to maximizing the ROI from anti-forensics is to use a layered approach that leverages all five of the anti-forensic strategies (see Figure 16.4). This is our version of the Dim Mak.

Figure 16.4

Specifically, you want to defeat the process of forensic investigation by leaving as little useful evidence as possible (data source elimination and data destruction). The evidence you leave behind should be difficult to capture (data concealment) and even more difficult to understand (data transformation). You can augment the effectiveness of this approach by planting misinformation and luring the investigator into predetermined conclusions (data fabrication).

Resist the Urge to Smash and Grab

From 10,000 feet, anti-forensics is about buying time. Even the most zealous investigator has limits in terms of how many hours he can devote to a given incident. Make him jump through enough hoops and eventually he’ll give up. There are many ways to buy time. If you wanted to, you could leave the investigator with a complete train wreck that would take months to process. The problem with this scorched earth approach is that it runs contrary to our primary goal. We want to stay concealed in such a manner that the investigator doesn’t suspect that we’re even there. Flooding a system with garbage and vandalizing the file system will definitely get someone’s attention. So buy time, but don’t do so in a manner that ends up drawing attention. As The Grugq’s mentor once asserted: Aspire to subtlety.5

Study Your Target

The hallmark of an effective attack is careful planning in conjunction with a sufficient amount of reconnaissance. Leave the noisy automated sweeps to the script kiddies. Take your time and find out as much as you can, as inconspicuously as you can.

Don’t assume that network-based collection is the only way to acquire useful data. Bribery, extortion, and the odd disgruntled employee have all been used in the field. The information you accumulate will give you an idea of how much effort you’ll need to invest. Some targets are monitored carefully, justifying extreme solutions (e.g., a firmware-based rootkit, or a hand-crafted SMI handler, or a rogue hypervisor, etc.). Other targets are maintained by demoralized troops who are poorly paid and could care less what happens, just as long as their servers keep running.

16.2 Identifying Hidden Doors

The idea of studying your target isn’t limited to the physical environment of the target. Once you discover the target’s operating system, you may need to do some homework to determine which tools to use. In this day and age, with the banks trying to get customers to do their business online via their smart phones, it’s not uncommon for a mobile operating system like Google’s Android to be the target.

You heard me, not a z-Series mainframe from IBM or a Sun SPARC enterprise M9000 server. The low-hanging fruit with the keys to the kingdom may be stored on a dinky little handheld device. This is what happens when executives decide that convenience trumps security.

On Dealing with Proprietary Systems

On a proprietary system, where access to source code is limited, poking around for new holes usually translates into lengthy sessions with a kernel debugger, where the most you’ll have to work with is assembly code and symbol packages. Thus, it’s worthwhile to become comfortable with your target platform’s debugging tools, its assembly language, runtime API, and the program flow conventions that it uses (i.e., building a stack frame, setting up a system call, handling exceptions, etc.). Reversing assembly code is like reading music. With enough experience, you can grasp the song that the individual notes form.

Another area in which you should accumulate knowledge is the target platform’s executable file format. Specifications exist for most binaries even if the exact details of how they’re loaded is undisclosed. Understanding the native executable format will offer insight into how the different components of an application are related and potentially give you enough information to successfully patch its memory image or to build a custom loader.

Taking the time to become familiar with the tools that allow you to examine and modify the composition of an executable is also a worthwhile endeavor. Utilities like dumpbin.exe are an effective way to perform the first cut of the reverse-engineering process by telling you what a specific binary imports and exports.

Staking Out the Kernel

Having familiarized yourself with the target platform’s tools, you’re ready to perform surgery. But before you start patching system internals, you need to know what to patch. Your first goal should be to start by enumerating the system call interface. The level of documentation you encounter may vary. Most UNIX-based systems provide all the gory details. Microsoft does not.

One way to start the ball rolling is to trace an application thread that invokes a user-mode API to perform disk access (or some other API call that’s likely to translate into a system call). The time that you spent studying the native debugging tools will start paying off here. Tracing the user-mode API will allow you to see what happens as the thread traverses the system call gate and dives into kernel mode. Most operating systems will use a call table of some sort to route program control to the appropriate address. Dissecting this call table to determine its layout and composition will yield the information that you’re after.

At this stage of the game, you’re ready to dig deeper, and the kernel’s debug symbols become your best friend. Once you’ve identified an interesting system call, you can disassemble it to see what other routines it calls and which data structures it touches. In many cases, the system call may rely heavily on undocumented kernel-mode routines to perform the heavy lifting. For truly sensitive code, the kind that performs integrity checking, keep in mind that Microsoft will try to protect itself through obfuscation and misdirection.

Kingpin: Hardware Is the New Software

In a sense, the rootkit arms race has evolved into a downward spiral to the metal, as Black Hats look for ways to evade detection by remaining out-of-band. Whereas kernel-mode drivers were good enough in the early 1990s, the investigators are catching up. Now you’ve got to become hardware literate.

Hardware-level Gung Fu takes things to a whole different level by dramatically expanding the field of battle. It often entails more digging, a more extensive skillset, a smorgasbord of special tools, and the sort of confidence that only comes with experience. If you want to get your feet wet in this area, I recommend reading through Joe Grand’s tutorial.6

Leverage Existing Research

Don’t wear a hair shirt if you don’t have to. The Internet is a big place, and someone may very well have tackled an issue similar to the one that you’re dealing with. I’m not saying you should fall back on cut-and-paste programming or link someone else’s object code into your executable. I’m just saying that you shouldn’t spend time reverse-engineering undocumented material when someone else has done the legwork for you. The Linux–NTFS project is a perfect example of this.

The same goes for partially documented material. For instance, when I was researching the Windows PE file format, Matt Pietrek’s articles were a heck of a lot easier to digest than the official specification (which is definitely not a learning device, just a reference).

Thus, before pulling out the kernel debugger and a hex editor, always perform a bit of due diligence on the Internet to see if related work has already been done. I’d rather spend a couple of hours online looking for an answer, and assume the risk that I might not find anything, than spend two months analyzing hex dumps. After all, the dissemination of technical and scientific information was the original motivation behind the World Wide Web to begin with.

16.3 Architectural Precepts

Having performed the necessary reconnaissance, you should now possess a basic set of requirements. These requirements will guide you through the design phase. The following design considerations should also help move you in the right direction.

Load First, Load Deep

In the battle between the attacker and defender, the advantage usually goes to:

Whoever achieves the higher level of privilege.

Whoever achieves the higher level of privilege.

Whoever loads his code first.

Whoever loads his code first.

Multi-ring privilege models have been around since the Stone Age. Though the IA-32 family supports four privilege levels, back in the early 1970s the Honeywell 6180 CPU supported eight rings of memory protection under MULTICS. Regardless of how many rings a particular processor can use, the deeper a rootkit can embed itself, the safer it is. Once a rootkit has maximized its privileges, it can attack security software that is running at lower privilege levels, much like castle guards in the Middle Ages who poured boiling oil down on their enemies.

Given the need to attain residence in the innermost ring, one way to gain the upper hand is to load first (i.e., preferably pre-boot, when the targeted machine is the most impressionable). This concept was originally illustrated during the development of bootkits. By executing during system startup, a bootkit is in a position where it can capture system components as they load into memory, altering them just before they execute. In this fashion, a bootkit can disable the integrity checking and other security features that would normally hinder infiltration into the kernel.

The same holds for SMM-based techniques. Once an SMI handler has been installed and the SMRAM control registers have been configured, it’s very difficult to storm the front gate. Whoever sets up camp in SMRAM first has the benefit of fairly solid fortifications, hence the appeal of firmware-based rootkits.

Strive for Autonomy

During development, you may be tempted to speed up your release cycle by relying heavily on existing system services and APIs. The downside of this approach is that it makes your code dependent on these services. This means a paper trail. In other words, your code will be subject to limitations that the infrastructure imposes and the auditing policy that it adheres to.

Ask any civil servant who works in a large bureaucracy. They’ll agree that there’s something to be said for the sense of empowerment that comes with autonomy. The more you rely on your own code, the fewer rules you have to follow, and the harder it is for someone to see what your code is doing, not to mention that your ability to function correctly isn’t constrained via dependence on other components (that may or may not be working properly). We saw this sort of dynamic appear when discussing the SCM, the Native API, and NDIS protocol drivers.

Moving toward the ultimate expression of this strategy, we could construct an out-of-band rootkit that has its own internal hardware drivers and its own set of dedicated run-time libraries so that it relies very little (if at all) on the host operating system. If we don’t rely on the target operating system to provide basic services and we build our own, there’s no bookkeeping metadata that can give us away.

Butler Lampson: Separate Mechanism from Policy

In you’re dealing with a high-value target that’s well protected, you might not be able to perform as much reconnaissance as you’d like. In some instances, all you may have to start with is a series of open ports at the other end of a network connection. If this is the case, your code will need to be flexible enough to handle multiple scenarios. A rootkit that can tunnel data over multiple protocols will have a better chance of connecting to the outside if the resident firewall blocks most outgoing traffic by default. A rootkit that can dynamically adjust which API routines it invokes, and what it patches in memory, is more likely to survive in a heterogeneous computing environment.

16.4 Engineering a Rootkit

Having established a set of abstract design goals and a skeletal blueprint, we can look at more concrete implementation issues. This is where the hypothetical domain of thought experiments ends and the mundane reality of nuts-and-bolts development begins.

Stealth Versus Development Effort

The price tag associated with autonomy can be steep. As we saw in the previous chapter, an out-of-band rootkit must typically deploy all of its own driver code. That’s not to say that it can’t be done or that it hasn’t been done. I’m just asserting that it takes more resources and a deeper skillset. In the software industry, there are people who make their living writing device driver code.

As an engineer, on behalf of whatever constraints you’re working under, you may be forced into a situation where you have to sacrifice stealth in the name of expediency or stability. That’s often what engineering is about, making concessions to find the right balance between competing requirements.

This is one area where the large organizations, the ones capable of building commercial satellites, have an advantage. They’re well funded, highly organized, and possess the necessary talent and industry connections to implement a custom out-of-band solution. What they lack outright, they can buy. Based on what outfits like Marvell and Teknovus are doing, chipset hacks are entirely feasible. Insider expertise is pervasive and readily available—for a price.

Use Custom Tools

This is something I can’t stress enough. The elite of the underground are known for building their own tools. The minute that an attack tool makes its way out into general availability, it will be studied exhaustively for signatures and patterns. The White Hats will immediately start working to counter the newly discovered tool with tools of their own in an effort to save time via automation.

You don’t want them to have this benefit. By using a custom tool you’re essentially forcing the investigator to have to build a counter-tool from scratch, resulting in a barrier to entry that might just convince the investigator to give up. In the best-case scenario, the investigator may even fail to recognize that a dedicated tool is being used because he can’t recognize its signature. Imagine for a moment, if you will, a clean-room implementation of an attack platform like Metasploit …

During the course of my own work, I’ve found that it pays to build tools first, before work on the primary deliverable begins. Go ahead and take the time to make them robust and serviceable, so they can withstand the beating you’re going to give them later on. This up-front investment will yield dividends later on.

Stability Counts: Invest in Best Practices

The desire to gain the high ground logically leads to developing code that will execute in unorthodox environments. Hence, it’s wise to code defensively. Special emphasis should be placed on preventing, detecting, reporting, and correcting potential problems. All it takes is one bad pointer or one type cast error to bring everything crashing down.

Not only that, but production-grade rootkits and their supporting tools can grow into nontrivial deliverables. Back at SOURCE Boston in 2010, I recall H.D. Moore commenting that the code base for Metasploit had reached more than 100,000 lines. The intricacy of a suite like this is great enough that a formal engineering process is called for.

Go ahead and take the time to build and maintain scaffolding code. Create unit tests for each subsystem. Research and use design patterns. Consider using an object-oriented approach to help manage complexity. Also, don’t get caught up in development and forget to deploy a revision control system and (inevitably) a bug tracking database. In other words, this is no place for the reckless abandon of cowboy-style software engineering.

At the end of the day, it’s all about stability. Crashes are conspicuous. Nothing gets the attention of a system administrator like a machine that turns blue. To a degree, I’d be willing to sacrifice sophistication for stability. It doesn’t matter how advanced your rootkit is if it gets discovered as a result of unexpected behavior.

Gradual Enhancement

Expect things to progress gradually. Be meticulous. Start with small victories and then build on them. Start with a simple technique, then re-implement with a more sophisticated one.

For example, if you’re going to modify a system call, see if you can start by implementing it with a hook. Hooking is easier to perform (you’re essentially swapping pointers in a call table), and this will allow you to focus on details of the modification rather than the logistics of injecting code. This way if something does go wrong, you’ll have a much better idea of what caused the problem.

After you’ve achieved a working hook routine, translating the hook into a full-blown detour patch isn’t that difficult. At this point, you know that the hook works, and this will allow you to focus on the details of inserting the corresponding program control detours.

One of the problems associated with detour patching is that it causes the execution path to stray into a foreign address space, something that security software might notice (i.e., suspicious-looking jump statements near the beginning or end of the system call). If at all possible, see if you can dispense with a detour patch in favor of an in-place patch, where you alter the existing bytes that make up the system call instead of re-routing program control to additional code.

Also, keep in mind that you may need to disable memory protection before you implement a patch. Some operating systems try to protect kernel routines by making them read/execute-only. And don’t forget to be wary of synchronization. You don’t want other threads executing a system call while you’re modifying it. Keep this code as short and sweet as possible.

Once you’ve succeeded in patching a system routine, see if you can reproduce the same result by altering dynamic system objects. Code is static. It’s not really intended to change, and this lends itself to detection by security software. Why not alter something that’s inherently dynamic by definition? Callback tables are a favorite target of mine.

With regard to kernel objects, if you can display the contents of a system data structure, you’re not that far away from being able to modify it. Thus, the first step you should take when dealing with a set of kernel data structures is to see if you can successfully enumerate them and dump all of their various fields to the debug console. Not only will this help to reassure you that you’re on the right path, but also you can recycle the code later on as a debugging aid.

The kernel debugger is an excellent lab for initial experiments, providing an environment where you can develop hunches and test them out. The kernel debugger extension commands, in particular, can be used to verify the results of modifications that your rootkit institutes.

As with system code, don’t forget to be wary of synchronization. Also, although you may be able to alter or remove data structures with abandon, it’s more risky dynamically to “grow” preexisting kernel data objects. Working in the address space of the kernel is like being a deep-sea scuba diver. Even with a high-powered flashlight, the water is cloudy and teaming with stuff that you can’t necessarily see. If you extend out beyond the edge of a given kernel object in search of extra space, you may end up overwriting something that’s already there and crash the system.

Failover: The Self-Healing Rootkit

When taking steps to protect your rootkit from operational failures, don’t put all of your eggs in one basket. One measure by itself may be defeated. Defend your rootkit by implementing redundant failover measures that reinforce each other.

Like the U.S. Federal Reserve banking system, a self-healing rootkit might keep multiple hot backups in place in the event that one of the primary components of the current instance fails. Naturally, there’s a trade-off here that you’re making with regard to being detected. The more modules that you load into memory and the more files you persist on disk, the greater your chances are of being detected.

Yet another example of this principle in action would be to embed an encrypted file system within an encrypted file system. If the forensic investigator is somehow able to crack the outer file system, he’ll probably stop there with the assumption that he’s broken the case.

16.5 Dealing with an Infestation

The question of how to restore a compromised machine arises frequently. Based on my experience, the best solution is to have a solid disaster recovery plan, one that you’ve refined over the course of several dry runs. You can replace hardware, you can re-install software, but once your data is corrupted/stolen … POOF! That’s it, game over.

If you’re not 100 percent certain what a malware application does, you can’t necessarily be sure that you’ve gotten rid of it. Once the operating system has been compromised, you can’t trust it to tell you the truth. Once more, even off-line forensic analysis isn’t guaranteed to catch everything. The only way to be absolutely sure that you’ve gotten rid of the malware is to (in the following order):

Boot from a trusted medium.

Boot from a trusted medium.

Flash your firmware.

Flash your firmware.

Scrub your disk.

Scrub your disk.

Rebuild from scratch (and patch).

Rebuild from scratch (and patch).

This underscores my view on software that touts itself as a cure-all. Most of the time, someone is trying to sell you snake oil. I don’t like these packages because I feel like they offer a false sense of security. Don’t ever gamble with the stability or security of your system. If you’ve been rooted, you need to rebuild, patch, and flash the firmware. Yes, it’s painful and tedious, but it’s the only true way to re-establish a trusted environment.

Look at it this way. If you have a current backup (e.g., a pristine image) and a well-rehearsed plan in place, you can probably rebuild your machine in an hour. Or, you can scan your machine with anti-virus software and, after a couple of hours, hope that it cleaned up your system. The difference between these two, from the standpoint of resource investment, is that with a rebuild you have the benefit of knowing that the machine is clean.

There is no easy, sweet-sounding answer. One reason why certain security tools sell so well is that the tool allows people to believe that they can avoid facing this fact.

1.http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2006/07/control-compliant-vs-field-assessed.html.

2. http://www.shadowserver.org/wiki/.

3. http://www.infowar-monitor.net/.

4. http://invisiblethings.org/papers/malware-taxonomy.pdf.

5. http://www.csoonline.com/article/216370/where-is-hacking-now-a-chat-with-grugq.

6. http://www.grandideastudio.com/wp-content/uploads/hardware_is_the_new_software_slides.pdf.