Chapter 1 Empty Cup Mind

So here you are; bone dry and bottle empty. This is where your path begins. Just follow the yellow brick road, and soon we’ll be face to face with Oz, the great and terrible. In this chapter, we’ll see how rootkits fit into the greater scheme of things. Specifically, we’ll look at the etymology of the term “rootkit,” how this technology is used in the basic framework of an attack cycle, and how it’s being used in the field. To highlight the distinguishing characteristics of a rootkit, we’ll contrast the technology against several types of malware and dispel a couple of common misconceptions.

1.1 An Uninvited Guest

A couple of years ago, a story appeared in the press about a middle-aged man who lived alone in Fukuoka, Japan. Over the course of several months, he noticed that bits of food had gone missing from his kitchen. This is an instructive lesson: If you feel that something is wrong, trust your gut.

So, what did our Japanese bachelor do? He set up a security camera and had it stream images to his cell phone.1 One day his camera caught a picture of someone moving around his apartment. Thinking that it was a thief, he called the police, who then rushed over to apprehend the burglar. When the police arrived, they noticed that all of the doors and windows were closed and locked. After searching the apartment, they found a 58-year-old woman named Tatsuko Horikawa curled up at the bottom of a closet. According to the police, she was homeless and had been living in the closet for the better half of a year.

The woman explained to the police that she had initially entered the man’s house one day when he left the door unlocked. Japanese authorities suspected that the woman only lived in the apartment part of the time and that she had been roaming between a series of apartments to minimize her risk of being caught.2 She took showers, moved a mattress into the closet where she slept, and had bottles of water to tide her over while she hid. Police spokesman Horiki Itakura stated that the woman was “neat and clean.”

In a sense, that’s what a rootkit is: It’s an uninvited guest that’s surprisingly neat, clean, and difficult to unearth.

1.2 Distilling a More Precise Definition

Although the metaphor of a neat and clean intruder does offer a certain amount of insight, let’s home in on a more exact definition by looking at the origin of the term. In the parlance of the UNIX world, the system administrator’s account (i.e., the user account with the least number of security restrictions) is often referred to as the root account. This special account is sometimes literally named “root,” but it’s a historical convention more than a requirement.

Compromising a computer and acquiring administrative rights is referred to as rooting a machine. An attacker who has attained root account privileges can claim that he or she rooted the box. Another way to say that you’ve rooted a computer is to declare that you own it, which essentially infers that you can do whatever you want because the machine is under your complete control. As Internet lore has it, the proximity of the letters p and o on the standard computer keyboard has led some people to substitute pwn for own.

Strictly speaking, you don’t necessarily have to seize an administrator’s account to root a computer. Ultimately, rooting a machine is about gaining the same level of raw access as that of the administrator. For example, the SYSTEM account on a Windows machine, which represents the operating system itself, actually has more authority than that of accounts in the Administrators group. If you can undermine a Windows program that’s running under the SYSTEM account, it’s just as effective as being the administrator (if not more so). In fact, some people would claim that running under the SYSTEM account is superior because tracking an intruder who’s using this account becomes a lot harder. There are so many log entries created by SYSTEM that it would be hard to distinguish those produced by an attacker.

Nevertheless, rooting a machine and maintaining access are two different things (just like making a million dollars and keeping a million dollars). There are tools that a savvy system administrator can use to catch interlopers and then kick them off a compromised machine. Intruders who are too noisy with their newfound authority will attract attention and lose their prize. The key, then, for intruders is to get in, get privileged, monitor what’s going on, and then stay hidden so that they can enjoy the fruits of their labor.

The Jargon File’s Lexicon3 defines a rookit as a “kit for maintaining root.” In other words:

A rootkit is a set of binaries, scripts, and configuration files (e.g., a kit) that allows someone covertly to maintain access to a computer so that he can issue commands and scavenge data without alerting the system’s owner.

A well-designed rootkit will make a compromised machine appear as though nothing is wrong, allowing an attacker to maintain a logistical outpost right under the nose of the system administrator for as long as he wishes.

The Attack Cycle

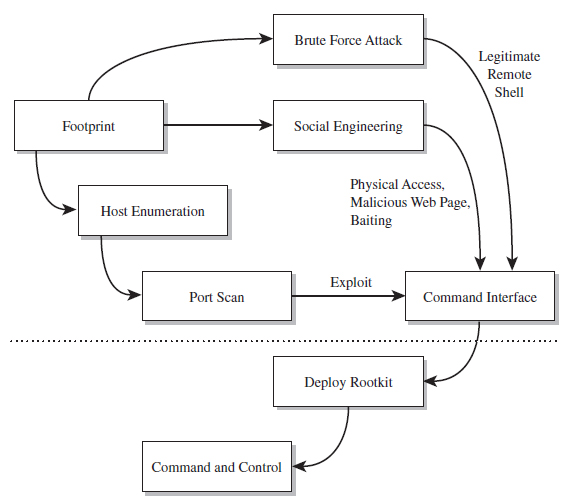

About now you might be wondering: “Okay, so how are machines rooted in the first place?” The answer to this question encompasses enough subject matter to fill several books.4 In the interest of brevity, I’ll offer a brief (if somewhat incomplete) summary.

Assuming the context of a precision attack, most intruders begin by gathering general intelligence on the organization that they’re targeting. This phase of the attack will involve sifting through bits of information like an organization’s DNS registration and assigned public IP address ranges. It might also include reading Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, annual reports, and press releases to determine where the targeted organization has offices.

If the attacker has decided on an exploit-based approach, they’ll use the Internet footprint they discovered in the initial phase of intelligence gathering to enumerate hosts via a ping sweep or a targeted IP scan and then examine each live host they find for standard network services. To this end, tools like nmap are indispensable.5

After an attacker has identified a specific computer and compiled a list of listening services, he’ll try to find some way to gain shell access. This will allow him to execute arbitrary commands and perhaps further escalate his rights, preferably to that of the root account (although, on a Windows machine, sometimes being a Power User is sufficient). For example, if the machine under attack is a web server, the attacker might launch a Structured Query Language (SQL) injection attack against a poorly written web application to compromise the security of the associated database server. Then, he can leverage his access to the database server to acquire administrative rights. Perhaps the password to the root account is the same as that of the database administrator?

The exploit-based approach isn’t the only attack methodology. There are myriad ways to get access and privilege. In the end, it’s all about achieving some sort of interface to the target (see Figure 1.1) and then increasing your rights.6

Figure 1.1

This interface doesn’t even have to be a traditional command shell; it can be a proprietary API designed by the attacker. You could just as easily establish an interface by impersonating a help desk technician or shoulder surfing. Hence, the tools used to root a machine will run the gamut: from social engineering (e.g., spear-phishing, scareware, pretext calls, etc.), to brute-force password cracking, to stealing backups, to offline attacks like Joanna Rutkowska’s “Evil Maid” scenario.7 Based on my own experience and the input of my peers, software exploits and social engineering are two of the more frequent avenues of entry for mass-scale attacks.

The Role of Rootkits in the Attack Cycle

Rootkits are usually brought into play at the tail end of an attack cycle. This is why they’re referred to as post-exploit tools. Once you’ve got an interface and (somehow) escalated your privileges to root level, it’s only natural to want to retain access to the compromised machine (also known as a plant or a foothold). Rootkits facilitate this continued access. From here, an attacker can mine the target for valuable information, like social security numbers, relevant account details, or CVV2s (i.e., full credit card numbers, with the corresponding expiration dates, billing addresses and three-digit security codes).

Or, an attacker might simply use his current foothold to expand the scope of his influence by attacking other machines within the targeted network that aren’t directly routable. This practice is known as pivoting, and it can help to obfuscate the origins of an intrusion (see Figure 1.2).

Notice how the last step in Figure 1.2 isn’t a pivot. As I explained in this book’s preface, the focus of this book is on the desktop because in many cases an attacker can get the information they’re after by simply targeting a client machine that can access the data being sought after. Why spend days trying to peel back the layers of security on a hardened enterprise-class mainframe when you can get the same basic results from popping some executive’s desktop system? For the love of Pete, go for the low-hanging fruit! As Richard Bejtlich has observed, “Once other options have been eliminated, the ultimate point at which data will be attacked will be the point at which it is useful to an authorized user.”8

Figure 1.2

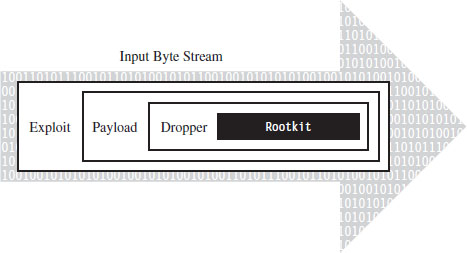

Single-Stage Versus Multistage Droppers

The manner in which a rootkit is installed on a target can vary. Sometimes it’s installed as a payload that’s delivered by an exploit. Within this payload will be a special program called a dropper, which performs the actual installation (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3

A dropper serves multiple purposes. For example, to help the rootkit make it past gateway security scanning, the dropper can transform the rootkit (e.g., compress it, encode it, or encrypt it) and then encapsulate it as an internal data structure. When the dropper is finally executed, it will drop (i.e., unpack/decode/decrypt and install) the rootkit. A well-behaved dropper will then delete itself, leaving only what’s needed by the rootkit.

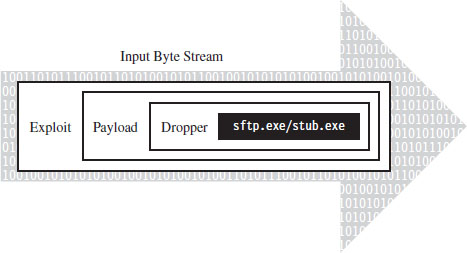

Multistage droppers do not include the rootkit as a part of their byte stream. Instead, they’ll ship with small programs like a custom FTP client, browser add-on, or stub program whose sole purpose in life is to download the rootkit over the network from a remote location (see Figure 1.4). In more extreme cases, the original stub program may download a second, larger stub program, which then downloads the rootkit proper such that installing the rootkit takes two separate phases.

Figure 1.4

The idea behind multistage droppers is to minimize the amount of forensic evidence that the dropper leaves behind. This way, if an investigator ever gets his hands on a dropper that failed to detonate and self-destruct properly, he won’t be able to analyze your rootkit code. For example, if he tries to run the dropper in an isolated sandbox environment, the stub program can’t even download the rootkit. In the worst-case scenario, the stub program will realize that it’s in a virtual environment and do nothing. This train of thought fits into The Grugq’s strategy of data contraception, which we’ll go into later on in the book.

Other Means of Deployment

There’s no rule that says a rootkit has to be deployed via exploit. There are plenty of other ways to skin a cat. For example, if an attacker has social engineered his way to console access, he may simply use the built-in FTP client or a tool like wget9 to download and run a dropper.

Or, an attacker could leave a USB thumb drive lying around, as bait, and rely on the drive’s AutoRun functionality to execute the dropper. This is exactly how the agent.btz worm found its way onto computers in CENTCOM’s classified network.10

What about your installation media? Can you trust it? In the pathologic case, a rootkit could find its way into the source code tree of a software product before it hits the customer. Enterprise software packages can consist of millions of lines of code. Is that obscure flaw really a bug or is it a cleverly disguised back door that has been intentionally left ajar?

This is a scenario that investigators considered in the aftermath of Operation Aurora.11 According to an anonymous tip (e.g., information provided by someone familiar with the investigation), the attackers who broke into Google’s source code control system were able to access the source code that implemented single sign-on functionality for network services provided by Google. The question then is, did they just copy it so that they could hunt for exploits or did they alter it?

There are even officials who are concerned that intelligence services in other countries have planted circuit-level rootkits on processors manufactured overseas.12 This is one of the dangers that results from outsourcing the development of critical technology to other countries. The desire for short-term profit undercuts this county’s long-term strategic interests.

A Truly Pedantic Definition

Now that you have some context, let’s nail down the definition of a rootkit one last time. We’ll start by noting how the experts define the term. By the experts, I mean guys like Mark Russinovich and Greg Hoglund. Take Mark Russinovich, for example, a long-term contributor to the Windows Internals book series from Microsoft and also to the Sysinternals tool suite. According to Mark, a rootkit is

“Software that hides itself or other objects, such as files, processes, and Registry keys, from view of standard diagnostic, administrative, and security software.”13

Greg Hoglund, the godfather of Windows rootkits, offered the following definition in the book that he co-authored with Jamie Butler:14

“A rootkit is a set of programs and code that allows a permanent or consistent, undetectable presence on a computer.”

Greg’s book first went to press in 2005, and he has since modified his definition:

“A rootkit is a tool that is designed to hide itself and other processes, data, and/or activity on a system”

In the blog entry that introduces this update definition, Greg adds:15

“Did you happen to notice my definition doesn’t bring into account intent or the word ‘intruder’?”

Note: As I mentioned in this book’s preface, I’m assuming the vantage point of a Black Hat. Hence, the context in which I use the term “rootkit” is skewed in a manner that emphasizes attack and intrusion.

In practice, rootkits are typically used to provide three services:

Concealment.

Concealment.

Command and control (C2).

Command and control (C2).

Surveillance.

Surveillance.

Without a doubt, there are packages that offer one or more of these features that aren’t rootkits. Remote administration tools like OpenSSH, GoToMyPC by Citrix, and Windows Remote Desktop are well-known standard tools. There’s also a wide variety of spyware packages that enable monitoring and data exfiltration (e.g., Spector Pro and PC Tattletale). What distinguishes a rootkit from other types of software is that it facilitates both of these features (C2 and surveillance, that is), and it allows them to be performed surreptitiously.

When it comes to rootkits, stealth is the primary concern. Regardless of what else happens, you don’t want to catch the attention of the system administrator. Over the long run, this is the key to surviving behind enemy lines (e.g., the low-and-slow approach). Sure, if you’re in a hurry you can pop a server, set up a Telnet session with admin rights, and install a sniffer to catch network traffic. But your victory will be short lived as long as you can’t hide what you’re doing.

Thus, at long last we finally arrive at my own definition:

“A rootkit establishes a remote interface on a machine that allows the system to be manipulated (e.g., C2) and data to be collected (e.g., surveillance) in a manner that is difficult to observe (e.g., concealment).”

The remaining chapters of this book will investigate the three services mentioned above, although the bulk of the material covered will be focused on concealment: finding ways to design a rootkit and modify the operating system so that you can remain undetected. This is another way of saying that we want to limit both the quantity and quality of the forensic evidence that we leave behind.

Don’t Confuse Design Goals with Implementation

A common misconception that crops up about rootkits is that they all hide processes, or they all hide files, or they communicate over encrypted Inter Relay Chat (IRC) channels, and so forth. When it comes to defining a rootkit, try not to get hung up on implementation details. A rootkit is defined by the services that it provides rather than by how it realizes them. As long as a software deliverable implements functionality that concurrently provides C2, surveillance, and concealment, it’s a rootkit.

This is an important point. Focus on the end result rather than the means. Think strategy, not tactics. If you can conceal your presence on a machine by hiding a process, so be it. But there are plenty of other ways to conceal your presence, so don’t assume that all rootkits hide processes (or some other predefined system object).

Rootkit Technology as a Force Multiplier

In military parlance, a force multiplier is a factor that significantly increases the effectiveness of a fighting unit. For example, stealth bombers like the B-2 Spirit can attack a strategic target without all of the support aircraft that would normally be required to jam radar, suppress air defenses, and fend off enemy fighters.

In the domain of information warfare, rootkits can be viewed as such, a force multiplier. By lulling the system administrator into a false sense of security, a rootkit facilitates long-term access to a machine, and this in turn translates into better intelligence. This explains why many malware packages have begun to augment their feature sets with rootkit functionality.

The Kim Philby Metaphor: Subversion Versus Destruction

It’s one thing to destroy a system; it’s another to subvert it. One of the fundamental differences between the two is that destruction is apparent and, because of this, a relatively short-term effect. Subversion, in contrast, is long term. You can rebuild and fortify assets that get destroyed. However, assets that are compromised internally may remain in a subtle state of disrepair for decades.

Harold “Kim” Philby was a British intelligence agent who, at the height of his career in 1949, served as the MI6 liaison to both the FBI and the newly formed CIA. For years, he moved through the inner circles of the Anglo–U.S. spy apparatus, all the while funneling information to his Russian handlers. Even the CIA’s legendary chief of counter-intelligence, James Jesus Angleton, was duped.

During his tenure as liaison, he periodically received reports summarizing translated Soviet messages that had been intercepted and decrypted as a part of project Venona. Philby was eventually uncovered, but by then most of the damage had already been done. He eluded capture until his defection to the Soviet Union in 1963.

Like a software incarnation of Kim Philby, rootkits embed themselves deep within the inner circle of the system where they can wield their influence to feed the executive false information and leak sensitive data to the enemy.

Why Use Stealth Technology? Aren’t Rootkits Detectable?

Some people might wonder why rootkits are necessary. I’ve even heard some security researchers assert that “in general using rootkits to maintain control is not advisable or commonly done by sophisticated attackers because rootkits are detectable.” Why not just break in and co-opt an existing user account and then attempt to blend in?

I think this reasoning is flawed, and I’ll explain why using a two-part response.

First, stealth technology is part of the ongoing arms race between Black Hats and White Hats. To dismiss rootkits outright, as being detectable, implies that this arms race is over (and I thoroughly assure you, it’s not). As old concealment tactics are discovered and countered, new ones emerge.

I suspect that Greg Hoglund, Jamie Butler, Holy Father, Joanna Rutkowska, and several anonymous engineers working for defense contracting agencies would agree: By definition, the fundamental design goal of a rootkit is to subvert detection. In other words, if a rootkit has been detected, it has failed in its fundamental mission. One failure shouldn’t condemn an entire domain of investigation.

Second, in the absence of stealth technology, normal users create a conspicuous audit trail that can easily be tracked using standard forensics. This means not only that you leave a substantial quantity of evidence behind, but also that this evidence is of fairly good quality. This would cause an intruder to be more likely to fall for what Richard Bejtlich has christened the Intruder’s Dilemma:16

The defender only needs to detect one of the indicators of the intruder’s presence in order to initiate incident response within the enterprise.

If you’re operating as a legitimate user, without actively trying to conceal anything that you do, everything that you do is plainly visible. It’s all logged and archived as it should in the absence of system modification. In other words, you increase the likelihood that an alarm will sound when you cross the line.

1.3 Rootkits != Malware

Given the effectiveness of rootkits and the reputation of the technology, it’s easy to understand how some people might confuse rootkits with other types of software. Most people who read the news, even technically competent users, see terms like “hacker” and “virus” bandied about. The subconscious tendency is to lump all these ideas together, such that any potentially dangerous software module is instantly a “virus.”

Walking through a cube farm, it wouldn’t be unusual to hear someone yell out something like: “Crap! My browser keeps shutting down every time I try to launch it, must be one of those damn viruses again.” Granted, this person’s problem may not even be virus related. Perhaps they just need to patch their software. Nevertheless, when things go wrong, the first thing that comes into the average user’s mind is “virus.”

To be honest, most people don’t necessarily need to know the difference between different types of malware. You, however, are reading a book on rootkits, and so I’m going to hold you to a higher standard. I’ll start off with a brief look at infectious agents (viruses and worms), then discuss adware and spyware. Finally, I’ll complete the tour with an examination of botnets.

Infectious Agents

The defining characteristic of infectious software like viruses and worms is that they exist to replicate. The feature that distinguishes a virus from a worm is how this replication occurs. Viruses, in particular, need to be actively executed by the user, so they tend to embed themselves inside of an existing program. When an infected program is executed, it causes the virus to spread to other programs. In the nascent years of the PC, viruses usually spread via floppy disks. A virus would lodge itself in the boot sector of the diskette, which would run when the machine started up, or in an executable located on the diskette. These viruses tended to be very small programs written in assembly code.17

Back in the late 1980s, the Stoned virus infected 360-KB floppy diskettes by placing itself in the boot sector. Any system that booted from a diskette infected with the Stoned virus would also be infected. Specifically, the virus loaded by the boot process would remain resident in memory, copying itself to any other diskette or hard drive accessed by the machine. During system startup, the virus would display the message: “Your computer is now stoned.” Later on in the book, we’ll see how this idea has been reborn as Peter Kleissner’s Stoned Bootkit.

Once the Internet boom of the 1990s took off, email attachments, browser-based ActiveX components, and pirated software became popular transmission vectors. Recent examples of this include the ILOVEYOU virus,18 which was implemented in Microsoft’s VBScript language and transmitted as an attachment named LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.TXT.vbs.

Note how the file has two extensions, one that indicates a text file and the other that indicates a script file. When the user opened the attachment (which looks like a text file on machines configured to hide file extensions), the Windows Script Host would run the script, and the virus would be set in motion to spread itself. The ILOVEYOU virus, among other things, sends a copy of the infecting email to everyone in the user’s email address book.

Worms are different in that they don’t require explicit user interaction (i.e., launching a program or double-clicking a script file) to spread; worms spread on their own automatically. The canonical example is the Morris Worm. In 1988, Robert Tappan Morris, then a graduate student at Cornell, released the first recorded computer worm out into the Internet. It spread to thousands of machines and caused quite a stir. As a result, Morris was the first person to be indicted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986 (he was eventually fined and sentenced to 3 years of probation). At the time, there wasn’t any sort of official framework in place to alert administrators about an outbreak. According to one in-depth examination,19 the UNIX “old-boy” network is what halted the worm’s spread.

Adware and Spyware

Adware is software that displays advertisements on the user’s computer while it’s being executed (or, in some cases, simply after it has been installed). Adware isn’t always malicious, but it’s definitely annoying. Some vendors like to call it “sponsor-supported” to avoid negative connotations. Products like Eudora (when it was still owned by Qualcomm) included adware functionality to help manage development and maintenance costs.

In some cases, adware also tracks personal information and thus crosses over into the realm of spyware, which collects bits of information about the user without his or her informed consent. For example, Zango’s Hotbar, a plugin for several Microsoft products, in addition to plaguing the user with ad pop-ups also records browsing habits and then phones home to Hotbar with the data. In serious cases, spyware can be used to commit fraud and identity theft.

Rise of the Botnets

The counterculture in the United States basically started out as a bunch of hippies sticking it to the man (hey dude, let your freak flag fly!). Within a couple of decades, it was co-opted by a hardcore criminal element fueled by the immense profits of the drug trade. One could probably say the same thing about the hacking underground. What started out as a digital playground for bored netizens (i.e., citizens online) is now a dangerous no-man’s land. It’s in this profit-driven environment that the concept of the botnet has emerged.

A botnet is a collection of machines that have been compromised (a.k.a. zombies) and are being controlled remotely by one or more individuals (bot herders). It’s a huge distributed network of infected computers that do the bidding of the herders, who issue commands to their minions through command-and-control servers (also referred to as C2 servers, which tend to be IRC or web servers with a high-bandwidth connection).

Bot software is usually delivered as a payload within a virus or worm. The bot herder “seeds” the Internet with the virus/worm and waits for his crop to grow. The malware travels from machine to machine, creating an army of zombies. The zombies log on to a C2 server and wait for orders. A user often has no idea that his machine has been turned, although he might notice that his machine has suddenly become much slower, as he now shares the machine’s resources with the bot herder.

Once a botnet has been established, it can be leased out to send spam, to enable phishing scams geared toward identity theft, to execute click fraud, and to perform distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks. The person renting the botnet can use the threat of DDoS for the purpose of extortion. The danger posed by this has proved serious. According to Vint Cerf, a founding father of the TCP/IP standard, up to 150 million of the 600 million computers connected to the Internet belong to a botnet.20 During a single incident in September 2005, police in the Netherlands uncovered a botnet consisting of 1.5 million zombies.21

Enter: Conficker

Although a commercial outfit like Google can boast a computing cloud of 500,000 systems, it turns out that the largest computing cloud on the planet belongs to a group of unknown criminals.22 According to estimates, the botnet produced by variations of the Conficker worm at one point included as many as 10 million infected hosts.23 The contagion became so prolific that Microsoft offered a $250,000 reward for information that resulted in the arrest and conviction of the hackers who created and launched the worm. However, the truly surprising aspect of Conficker is not necessarily the scale of its host base as much as the fact that the resulting botnet really didn’t do that much.24

According to George Ledin, a professor at Sonoma State University who also works with researchers at SRI, what really interests many researchers in the Department of Defense (DoD) is the worm’s sheer ability to propagate. From an offensive standpoint, this is a useful feature because as an attacker, what you’d like to do is quietly establish a pervasive foothold that spans the infrastructure of your opponent: one big massive sleeper cell waiting for the command to activate. Furthermore, you need to set this up before hostilities begin. You need to dig your well before you’re thirsty so that when the time comes, all you need to do is issue a few commands. Like a termite infestation, once the infestation becomes obvious, it’s already too late.

Malware Versus Rootkits

Many of the malware variants that we’ve seen have facets of their operation that might get them confused with rootkits. Spyware, for example, will often conceal itself while collecting data from the user’s machine. Botnets implement remote control functionality. Where does one draw the line between rootkits and various forms of malware? The answer lies in the definition that I presented earlier. A rootkit isn’t concerned with self-propagation, generating revenue from advertisements, or sending out mass quantities of network traffic. Rootkits exist to provide sustained covert access to a machine so that the machine can be remotely controlled and monitored in a manner that’s difficult to detect.

This doesn’t mean that malware and rootkit technology can’t be fused together. As I said, rootkit technology is a force multiplier, one that can be applied in a number of different theaters. For instance, a botnet zombie might use a covert channel to make its network traffic more difficult to identify. Likewise, a rootkit might utilize armoring, a tactic traditionally in the domain of malware, to foil forensic analysis.

The term stealth malware has been used by researchers like Joanna Rutkowska to describe malware that is stealthy by design. In other words, the program’s ability to remain concealed is built-in, rather than being supplied by extra components. For example, whereas a classic rootkit might be used to hide a malware process in memory, stealth malware code that exists as a thread within an existing process doesn’t need to be hidden.

1.4 Who Is Building and Using Rootkits?

Data is the new currency. This is what makes rootkits a relevant topic: Rootkits are intelligence tools. It’s all about the data. Believe it or not, there’s a large swath of actors in the world theater using rootkit technology. One thing they all have in common is the desire covertly to access and manipulate data. What distinguishes them is the reason why.

Marketing

When a corporate entity builds a rootkit, you can usually bet that there’s a financial motive lurking somewhere in the background. For example, they may want to highlight a tactic that their competitors can’t handle or garner media attention as a form of marketing.

Before Joanna Rutkowska started the Invisible Things Lab, she developed offensive tools like Deepdoor and Blue Pill for COSEINC’s Advanced Malware Laboratory (AML). These tools were presented to the public at Black Hat DC 2006 and Black Hat USA 2006, respectively. According to COSEINC’s website:25

The focus of the AML is cutting-edge research into malicious software technology like rookits, various techniques of bypassing security mechanisms inherent in software systems and applications and virtualization security.

The same sort of work is done at outfits like Security-Assessment.com, a New Zealand–based company that showcased the DDefy rootkit at Black Hat Japan 2006. The DDefy rootkit used a kernel-mode filter driver (i.e., ddefy. sys) to demonstrate that it’s entirely feasible to undermine runtime disk imaging tools.

Digital Rights Management

This comes back to what I said about financial motives. Sony, in particular, used rootkit technology to implement digital rights management (DRM) functionality. The code, which installed itself with Sony’s CD player, hid files, directories, tasks, and registry keys whose names begin with “$sys$.”26 The rootkit also phoned home to Sony’s website, disclosing the player’s ID and the IP address of the user’s machine. After Mark Russinovich, of System Internals fame, talked about this on his blog, the media jumped all over the story and Sony ended up going to court.

It’s Not a Rootkit, It’s a Feature

Sometimes a vendor will use rootkit technology simply to insulate the user from implementation details that might otherwise confuse him. For instance, after exposing Sony’s rootkit, Mark Russinovich turned his attention to the stealth technology in Symantec’s SystemWorks product.27

SystemWorks offered a feature known as the “Norton Protected Recycle Bin,” which utilized a directory named NPROTECT. SystemWorks created this folder inside of each volume’s RECYCLER directory. To prevent users from deleting it, SystemWorks concealed the NPROTECT folder from certain Windows directory enumeration APIs (i.e., FindFirst()/FindNext()) using a custom file system filter driver.28

As with Sony’s DRM rootkit, the problem with this feature is that an attacker could easily subvert it and use it for nefarious purposes. A cloaked NTPROTECT provides storage space for an attacker to place malware because it may not be scanned during scheduled or manual virus scans. Once Mark pointed this out to Symantec, they removed the cloaking functionality.

Law Enforcement

Historically speaking, rookits were originally the purview of Black Hats. Recently, however, the Feds have also begun to find them handy. For example, the FBI developed a program known as Magic Lantern, which, according to reports,29 could be installed via email or through a software exploit. Once installed, the program surreptitiously logged keystrokes. It’s likely that the FBI used this technology, or something very similar, while investigating reputed mobster Nicodemo Scarfo Jr. on charges of gambling and loan sharking.30 According to news sources, Scarfo was using PGP31 to encrypt his files, and the FBI agents would’ve been at an impasse unless they got their hands on the encryption key. I suppose one could take this as testimony to the effectiveness of the PGP suite.

More recently, the FBI has created a tool referred to as a “Computer and Internet Protocol Address Verifier” (CIPAV). Although the exact details of its operation are sketchy, it appears to be deployed via a specially crafted web page that leverages a browser exploit to load the software.32 In other words, CIPAV gets on the targeted machine via a drive-by download. Once installed, CIPAV funnels information about the targeted host (e.g., network configuration, running programs, IP connections) back to authorities. The existence of CIPAV was made public in 2007 when the FBI used it to trace bomb threats made by a 15-year-old teenager.33

Some anti-virus vendors have been evasive in terms of stating how they would respond if a government agency asked them to whitelist its binaries. This brings up a disturbing point: Assume that the anti-virus vendors agreed to ignore a rootkit like Magic Lantern. What would happen if an attacker found a way to use Magic Lantern as part of his own rootkit?

Industrial Espionage

As I discussed in this book’s preface, high-ranking intelligence officials like the KGB’s Vladimir Kryuchkov are well aware of the economic benefits that industrial espionage affords. Why invest millions of dollars and years of work to develop technology when it’s far easier to let someone else do the work and then steal it? For example, in July 2009, a Russian immigrant who worked for Goldman Sachs as a programmer was charged with stealing the intellectual property related to a high-frequency trading platform developed by the company. He was arrested shortly after taking a job with a Chicago firm that agreed to pay him almost three times more than the $400,000 salary he had at Goldman.34

In January 2010, both Google35 and Adobe36 announced that they had been targets of sophisticated cyberattacks. Although Adobe was rather tight-lipped in terms of specifics, Google claimed that the attacks resulted in the theft of intellectual property. Shortly afterward, the Wall Street Journal published an article stating that “people involved in the investigation” believe that the attack included up to 34 different companies.37

According to an in-depth analysis of the malware used in the attacks,38 the intrusion at Google was facilitated by a javascript exploit that targeted Internet Explorer (which is just a little ironic, given that Google develops its own browser in-house). This exploit uses a heap spray attack to inject embedded shellcode into Internet Explorer, which in turn downloads a dropper. This dropper extracts an embedded Dynamic-Link Library (DLL) into the %SystemRoot%\System32 directory and then loads the DLL into a svchost.exe module. The installed software communicates with its C2 server over a faux HTTPS session.

There’s no doubt that industrial espionage is a thriving business. The Defense Security Service publishes an annual report that compiles accounts of intelligence “collection attempts” and “suspicious contacts” identified by defense contractors who have access to classified information. According to the 2009 report, which covers data collected over the course of 2008, “commercial entities attempted to collect defense technology at a rate nearly double that of governmental or individual collector affiliations.”39

Political Espionage

Political espionage differs from industrial espionage in that the target is usually a foreign government rather than a corporate entity. National secrets have always been an attractive target. The potential return on investment is great enough that they warrant the time and resources necessary to build a military-grade rootkit. For example, in 2006 the Mossad surreptitiously planted a rootkit on the laptop of a senior Syrian government official while he was at a hotel in London. The files that they exfiltrated from the laptop included construction plans and photographs of a facility that was believed to be involved in the production of fissile material.40 In 2007, Israeli fighter jets bombed the facility.

On March 29, 2009, an independent research group called the Information Warfare Monitor released a report41 detailing a 10-month investigation of a system of compromised machines they called GhostNet. The study revealed a network of 1,295 machines spanning 103 countries where many of the computers rooted were located in embassies, ministries of foreign affairs, and the offices of the Dalai Lama. Researchers were unable to determine who was behind GhostNet. Ronald Deibert, a member of the Information Warfare Monitor, stated that “This could well be the CIA or the Russians. It’s a murky realm that we’re lifting the lid on.”42

Note: Go back and read that last quote one more time. It highlights a crucial aspect of cyberwar: the quandary of attribution. I will touch upon this topic and its implications, at length, later on in the book. There is a reason why intelligence operatives refer to their profession as the “wilderness of mirrors.”

A year later, in conjunction with the Shadow Server Foundation, the Information Warfare Monitor released a second report entitled Shadows in the Cloud: Investigating Cyber Espionage 2.0. This report focused on yet another system of compromised machines within the Indian government that researchers discovered as a result of their work on GhostNet.

Researchers claim that this new network was more stealthy and complex than GhostNet.43 It used a multitiered set of C2 servers that utilized cloud-based and social networking services to communicate with compromised machines. By accessing the network’s C2 servers, researchers found a treasure trove of classified documents that included material taken from India’s Defense Ministry and sensitive information belonging to a member of the National Security Council Secretariat.

Cybercrime

Cybercrime is rampant. It’s routine. It’s a daily occurrence. The Internet Crime Complaint Center, a partnership between the FBI, Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the National White Collar Crime Center, registered 336,655 cybercrime incidents in 2009. The dollar loss of these incidents was approximately $560 million.44 Keep in mind that these are just the incidents that get reported.

As the Internet has evolved, its criminal ecosystem has also matured. It’s gotten to the point where you can buy malware as a service. In fact, not only do you get the malware, but also you get support and maintenance.45 No joke, we’re talking full-blown help desks and ticketing systems.46 The model for malware development has gone corporate, such that the creation and distribution of malware has transformed into a cooperative process where different people specialize in different areas of expertise. Inside of the typical organization you’ll find project managers, developers, front men, and investors. Basically, with enough money and the right connections, you can outsource your hacking entirely to third parties.

One scareware vendor, Innovative Marketing Ukraine (IMU), hired hundreds of developers and generated a revenue of $180 million in 2008.47 This cybercrime syndicate had all the trappings of a normal corporation, including a human resources department, an internal IT staff, company parties, and even a receptionist.

A study released by RSA in April 2010 claims that “domains individually representing 88 percent of the Fortune 500 were shown to have been accessed to some extent by computers infected by the Zeus Trojan.”48 One reason for the mass-scale proliferation of Zeus technology is that it has been packaged in a manner that makes it accessible to nontechnical users. Like any commercial software product, the Zeus kit ships with a slick GUI that allows the generated botnet to be tailored to the user’s requirements.

Botnets have become so prevalent that some malware toolkits have features to disable other botnet software from a targeted machine so that you have exclusive access. For example, the Russian SpyEye toolkit offers a “Kill Zeus” option that can be used by customers to turn the tables on botnets created with the Zeus toolkit.

It should, then, come as no surprise that rootkit technology has been widely adopted by malware as a force multiplier. In a 2005 interview with SecurityFocus.com, Greg Hoglund described how criminals were bundling the FU rootkit, a proof-of-concept implementation developed by Jamie Butler, in with their malware. Greg stated that “FU is one of the most widely deployed rootkits in the world. [It] seems to be the rootkit of choice for spyware and bot networks right now, and I’ve heard that they don’t even bother recompiling the source.”49

Who Builds State-of-the-Art Rootkits?

When it comes to rootkits, our intelligence agencies rely heavily on private sector technology. Let’s face it: Intelligence is all about acquiring data (sometimes by illicit means). In the old days, this meant lock picking and microfilm; something I’m sure that operatives with the CIA excelled at. In this day and age, valuable information in other countries is stockpiled in data farms and laptops. So it’s only natural to assume that rootkits are a standard part of modern spy tradecraft. For instance, in March 2005 the largest cellular service provider in Greece, Vodafone-Panafon, found out that four of its Ericsson AXE switches had been compromised by rootkits.

These rootkits modified the switches to both duplicate and redirect streams of digitized voice traffic so that the intruders could listen in on calls. Ironically the rootkits leveraged functionality that was originally in place to facilitate legal intercepts on behalf of law enforcement investigations. The rootkits targeted the conversations of more than 100 highly placed government and military officials, including the prime minister of Greece, ministers of national defense, the mayor of Athens, and an employee of the U.S. embassy.

The rootkits patched the switch software so that the wiretaps were invisible, none of the associated activity was logged, and so that the rootkits themselves were not detectable. Once more, the rootkits included a back door to enable remote access. Investigators reverse-engineered the rootkit’s binary image to create an approximation of its original source code. What they ended up with was roughly 6,500 lines of code. According to investigators, the rootkit was implemented with “a finesse and sophistication rarely seen before or since.”50

The Moral Nature of a Rootkit

As you can see, a rootkit isn’t just a criminal tool. Some years back, I worked with a World War II veteran of Hungarian descent who observed that the moral nature of a gun often depended on which side of the barrel you were facing. One might say the same thing about rootkits.

In my mind, a rootkit is what it is: a sort of stealth technology. Asking whether rootkits are inherently good or bad is a ridiculous question. I have no illusions about what this technology is used for, and I’m not going to try and justify, or rationalize, what I’m doing by churching it up with ethical window dressing. As an author, I’m merely acting as a broker and will provide this information to whomever wants it. The fact is that rootkit technology is powerful and potentially dangerous. Like any other tool of this sort, both sides of the law take a peculiar (almost morbid) interest in it.

1.5 Tales from the Crypt: Battlefield Triage

When I enlisted as an IT foot soldier at San Francisco State University, it was like being airlifted to a hot landing zone. Bullets were flying everywhere. The university’s network (a collection of subnets in a class B address range) didn’t have a firewall to speak of, not even a Network Address Translation (NAT) device. Thousands of machines were just sitting out in the open with public IP addresses. In so many words, we were free game for every script kiddy and bot herder on the planet.

The college that hired me manages roughly 500 desktop machines and a rack of servers. At the time, these computers were being held down by a lone system administrator and a contingent of student assistants. To be honest, faced with this kind of workload, the best that this guy could hope to do was to focus on the visible problems and pray that the less conspicuous problems didn’t creep up and bite him in the backside. The caveat of this mindset is that it tends to allow the smaller fires to grow into larger fires, until the fires unite into one big firestorm. But, then again, who doesn’t like a good train wreck?

It was in this chaotic environment that I ended up on the receiving end of attacks that used rootkit technology. A couple of weeks into the job, a coworker and I found the remnants of an intrusion on our main file server. The evidence was stashed in the System Volume Information directory. This is one of those proprietary spots that Windows wants you blissfully to ignore. According to Microsoft’s online documentation, the System Volume Information folder is “a hidden system folder that the System Restore tool uses to store its information and restore points.”51

The official documentation also states that “you might need to gain access to this folder for troubleshooting purposes.” Normally, only the operating system has permissions to this folder, and many system administrators simply dismiss it (making it the perfect place to stash hack tools).

Note: Whenever you read of a system-level object being “reserved,” as The Grugq has noted this usually means that it’s been reserved for hackers. In other words, undocumented and cryptic-sounding storage areas, which system administrators are discouraged from fiddling with, make effective hiding spots.

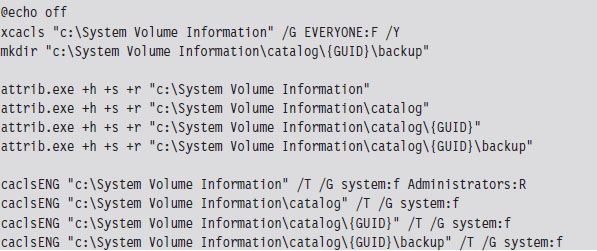

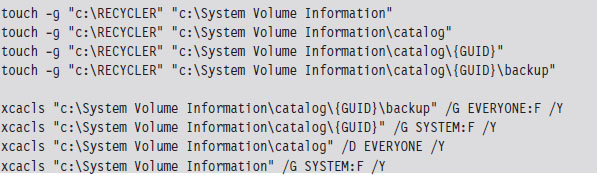

The following series of batch file snippets is a replay of the actions that attackers took once they had a foothold on our file server. My guess is that they left this script behind so that they could access it quickly without having to send files across the WAN link. The attackers began by changing the permissions on the System Volume Information folder. In particular, they changed things so that everyone had full access. They also created a backup folder where they could store files and nested this folder within the System Volume directory to conceal it.

The calcsENG.exe program doesn’t exist on the standard Windows install. It’s a special tool that the attackers brought with them. They also brought their own copy of touch.exe, which was a Windows port of the standard UNIX program.

Note: For the sake of brevity, I have used the string “GUID” to represent the global unique identifier “F750E6C3-38EE-11D1-85E5-00C04FC295EE.”

To help cover their tracks, they changed the time stamp on the System Volume Information directory structure so that it matched that of the Recycle Bin, and then further modified the permissions on the System Volume Information directory to lock down everything but the backup folder. The tools that they used probably ran under the SYSTEM account (which means that they had compromised the server completely). Notice how they place their backup folder at least two levels down from the folder that has DENY access permissions. This is, no doubt, a move to hide their presence on the server.

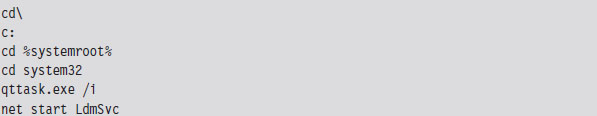

After they were done setting up a working folder, they changed their focus to the System32 folder, where they installed several files (see Table 1.1). One of these files was a remote access program named qttask.exe.

Table 1.1 Evidence from the Scene

| File | Description |

| qttask.exe | FTP-based C2 component |

| pwdump5.exe | Dumps password hashes from the local SAM DB52 |

| lyae.cmm | ASCII banner file |

| pci.acx, wci.acx | ASCII text configuration files |

| icp.nls, icw.nls | Language support files |

| libeay32.dll, ssleay32.dll | DLLs used by OpenSSL53 |

| svcon.crt | PKI certificates used by DLLs |

| svcon.key | ASCII text registry key entry |

| SAM | Security accounts manager |

| DB | Database |

| PKI | Public key infrastructure |

Under normal circumstances, the qttask.exe executable would be Apple’s QuickTime player, a standard program on many desktop installations. A forensic analysis of this executable on a test machine proved otherwise (we’ll discuss forensics and anti-forensics later on in the book). In our case, qttask.exe was a modified FTP server that, among other things, provided a remote shell. The banner displayed by the FTP server announced that the attack was the work of “Team WzM.” I have no idea what WzM stands for, perhaps “Wort zum Montag.” The attack originated on an IRC port from the IP address 195.157.35.1, a network managed by Dircon.net, which is headquartered in London.

Once the FTP server was installed, the batch file launched the server. The qttask.exe executable ran as a service named LdmSvc (the display name was “Logical Disk Management Service”). In addition to allowing the rootkit to survive a reboot, running as a service was also an attempt to escape detection. A harried system administrator might glance at the list of running services and (particularly on a dedicated file server) decide that the Logical Disk Management Service was just some special “value-added” Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) program.

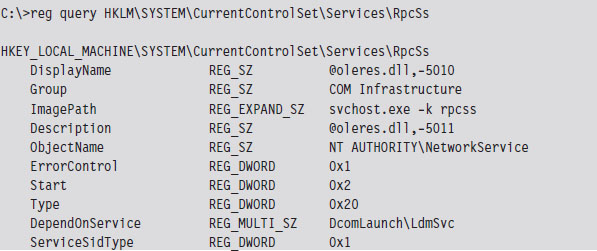

The attackers made removal difficult for us by configuring several key services, like Remote Procedure Call (RPC) and the Event Logging service, to be dependent upon the LdmSvc service. They did this by editing service entries in the registry (see HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services). Some of the service registry keys possess a REG_MULTI_SZ value named DependOnService that fulfills this purpose. Any attempt to stop LdmSvc would be stymied because the OS would protest (i.e., display a pop-up window), reporting to the user that core services would also cease to function. We ended up having manually to edit the registry, to remove the dependency entries, delete the LdmSvc sub-key, and then reboot the machine to start with a clean slate.

On a compromised machine, we’d sometimes see entries that looked like:

Note how the DependOnService field has been set to include LdmSvc, the faux Logical Disk Management service.

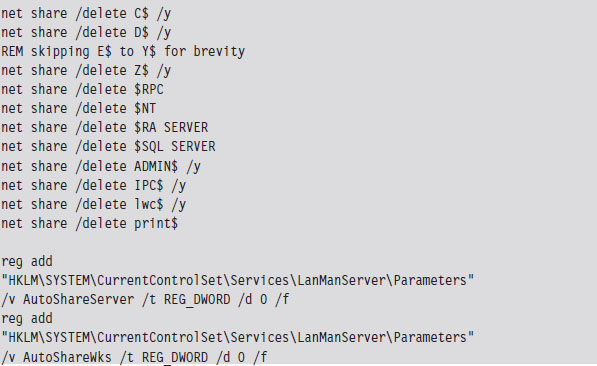

Like many attackers, after they had established an outpost on our file server, they went about securing the machine so that other attackers wouldn’t be able to get in. For example, they shut off the default hidden shares.

Years earlier, back when NT 3.51 was cutting edge, the college’s original IT director decided that all of the machines (servers, desktops, and laptops) should all have the same password for the local system administrator account. I assume this decision was instituted so that technicians wouldn’t have to remember as many passwords or be tempted to write them down. However, once the attackers ran pwdump5, giving them a text file containing the file server’s Lan Manager (LM) and New Technology Lan Manager (NTLM) hashes, it was the beginning of the end. No doubt, they brute forced the LM hashes offline with a tool like John the Ripper54 and then had free reign to every machine under our supervision (including the domain controllers). Game over, they sank our battleship.

In the wake of this initial discovery, it became evident that Hacker Defender had found its way on to several of our servers, and the intruders were gleefully watching us thrash about in panic. To amuse themselves further, they surreptitiously installed Microsoft’s Software Update Services (SUS) on our web server and then adjusted the domain’s group policy to point domain members to the rogue SUS server.

Just in case you’re wondering, Microsoft’s SUS product was released as a way to help administrators provide updates to their machines by acting as a LAN-based distribution point. This is particularly effective on networks that have a slow WAN link. Whereas gigabit bandwidth is fairly common in American universities, there are still local area networks (e.g., Kazakhstan) where dial-up to the outside is as good as it gets. In slow-link cases, the idea is to download updates to a set of one or more web servers on the LAN, and then have local machines access updates without having to get on the Internet. Ostensibly, this saves bandwidth because the updates only need to be downloaded from the Internet once.

Although this sounds great on paper, and the Microsoft Certified System Engineer (MCSE) exams would have you believe that it’s the greatest thing since sliced bread, SUS servers can become a single point of failure and a truly devious weapon if compromised. The intruders used their faux SUS server to install a remote administration suite called DameWare on our besieged desktop machines (which dutifully installed the .MSI files as if they were a legitimate update). Yes, you heard right. Our update server was patching our machines with tools that gave the attackers a better foothold on the network. The ensuing cleanup took the better part of a year. I can’t count the number of machines that we rebuilt from scratch. When a machine was slow to respond or had locked out a user, the first thing we did was to look for DameWare.

As it turns out, the intrusions in our college were just a drop in the bucket as far as the spectrum of campus-wide security incidents was concerned. After comparing notes with other IT departments, we concluded that there wasn’t just one group of attackers. There were, in fact, several groups of attackers, from different parts of Europe and the Baltic states, who were waging a virtual turf war to see who could stake the largest botnet claim in the SFSU network infrastructure. Thousands of computers had been turned to zombies (and may still be, to the best of my knowledge).

1.6 Conclusions

By now you should understand the nature of rootkit technology, as well as how it’s used and by whom. In a nutshell, the coin of this realm is stealth: denying certain information to the machine’s owner in addition to perhaps offering misinformation. Put another way, we’re limiting both the quantity of forensic information that’s generated and the quality of this information. Stepping back from the trees to view the forest, a rootkit is really just a kind of anti-forensic tool. This, dear reader, leads us directly to the next chapter.

1. “Japanese Woman Caught Living in Man’s Closet,” China Daily, May 31, 2008.

2. “Japanese Man Finds Woman Living in his Closet,” AFP, May 29, 2008.

3. http://catb.org/jargon/html/index.html.

4. Stuart McClure, Joel Scambray, & George Kurtz, Hacking Exposed, McGraw-Hill, 2009, ISBN-13: 978-0071613743.

6. mxatone, “Analyzing local privilege escalations in win32k,” Uninformed, October 2008.

7. http://theinvisiblethings.blogspot.com/2009/01/why-do-i-miss-microsoft-bitlocker.html.

8. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2009/10/protect-data-where.html.

9. http://www.gnu.org/software/wget/.

10. Kevin Poulsen, “Urban Legend Watch: Cyberwar Attack on U.S. Central Command,” Wired, March 31, 2010.

11. John Markoff, “Cyberattack on Google Said to Hit Password System,” New York Times, April 19, 2010.

12. John Markoff, “Old Trick Threatens the Newest Weapons,” New York Times, October 26, 2009.

13. Mark Russinovich, Rootkits in Commercial Software, January 15, 2006, http://blogs.technet.com/markrussinovich/archive/2006/01/15/rootkits-in-commercial-software.aspx.

14. Greg Hoglund and Jamie Butler, Rootkits: Subverting the Windows Kernel, Addison-Wesley, 2005, ISBN-13: 978-0321294319.

15. http://rootkit.com/blog.php?newsid=440&user=hoglund.

16. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2009/05/defenders-dilemma-and-intruders-dilemma.html.

17. Mark Ludwig, The Giant Black Book of Computer Viruses, American Eagle Publications, 1998.

18. http://us.mcafee.com/virusInfo/default.asp?id=description&virus_k=98617.

19. Eugene Spafford, “Crisis and Aftermath,” Communications of the ACM, June 1989, Volume 32, Number 6.

20. Tim Weber, “Criminals may overwhelm the web,” BBC News, January 25, 2007.

21. Gregg Keizer, “Dutch Botnet Suspects Ran 1.5 Million Machines,” TechWeb, October 21, 2005.

22. Robert Mullins, “The biggest cloud on the planet is owned by … the crooks,” NetworkWorld, March 22, 2010.

23. http://mtc.sri.com/Conficker/.

24. John Sutter, “What Ever Happened to The Conficker Worm,” CNN, July 27, 2009.

25. http://www.coseinc.com/en/index.php?rt=about.

26. Mark Russinovich, Sony, Rootkits and Digital Rights Management Gone Too Far, October, 31, 2005.

27. Mark Russinovich, Rootkits in Commercial Software, January, 15, 2006.

28. http://www.symantec.com/avcenter/security/Content/2006.01.10.html.

29. Ted Bridis, “FBI Develops Eavesdropping Tools,” Washington Post, November 22, 2001.

30. John Schwartz, “U.S. Refuses To Disclose PC Tracking,” New York Times, August 25, 2001.

32. Kevin Poulsen, “FBI Spyware: How Does the CIPAV Work?” Wired, July 18, 2007.

33. Kevin Poulsen, “Documents: FBI Spyware Has Been Snaring Extortionists, Hackers for Years,” Wired, April 16, 2009.

34. Matthew Goldstein, “A Goldman Trading Scandal?” Reuters, July 5, 2009.

35. http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2010/01/new-approach-to-china.html.

36. http://blogs.adobe.com/conversations/2010/01/adobe_investigates_corporate_n.html.

37. Jessica Vascellaro, Jason Dean, and Siobhan Gorman, “Google Warns of China Exit Over Hacking,” Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2010.

38. http://www.hbgary.com/wp-content/themes/blackhat/images/hbgthreatreport_aurora.pdf.

39. http://dssa.dss.mil/counterintel/2009/index.html.

40. Kim Zetter, “Mossad Hacked Syrian Official’s Computer Before Bombing Mysterious Facility,” Wired, November 3, 2009.

41. http://www.infowar-monitor.net/research/.

42. John Markoff, “Vast Spy System Loots Computers in 103 Countries,” New York Times, March 29, 2009.

43. John Markoff and David Barboza, “Researchers Trace Data Theft to Intruders in China,” New York Times, April 5, 2010.

44. http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreport/2009_IC3Report.pdf.

45. Ry Crozier, “Cybercrime-as-a-service takes off,” itnews.com, March 12, 2009.

46. http://blog.damballa.com/?p=454.

47. Jim Finkle, “Inside a Global Cybercrime Ring,” Reuters, March 24, 2010.

48. http://www.rsa.com/products/consumer/whitepapers/10872_CYBER_WP_0410.pdf.

49. Federico Biancuzzi, “Windows Rootkits Come of Age,” SecurityFocus.com, September 27, 2005.

50. Vassilis Prevelakis and Diomidis Spinellis, “The Athens Affair,” IEEE Spectrum Online, July 2007.

51. Microsoft Corporation, How to gain access to the System Volume Information folder, Knowledge Base Article 309531, May 7, 2007.

52. http://passwords.openwall.net/microsoft-windows-nt-2000-xp-2003-vista.