Chapter 2 Overview of Anti-Forensics

While I was working on the manuscript to this book’s first edition, I came to the realization that the stealth-centric tactics used by rootkits fall within the more general realm of anti-forensics (AF). As researchers like The Grugq have noted, AF is all about quantity and quality. The goal of AF is to minimize the quantity of useful trace evidence that’s generated in addition to ensuring that the quality of this information is also limited (as far as a forensic investigation is concerned). To an extent, this is also the mission that a rootkit seeks to fulfill.

In light of this, I decided to overhaul the organization of this book. Although my focus is still on rootkits, the techniques that I examine will use AF as a conceptual framework. With the first edition of The Rootkit Arsenal, I can see how a reader might have mistakenly come away with the notion that AF and rootkit technology are distinct areas of research. Hopefully, my current approach will show how the two are interrelated, such that rootkits are a subset of AF.

To understand AF, however, we must first look at computer forensics. Forensics and AF are akin to the yin and yang of computer security. They reflect complementary aspects of the same domain, and yet within one are aspects of the other. Practicing forensics can teach you how to hide things effectively and AF can teach you how to identify hidden objects.

In this part of the book, I’ll give you an insight into the mindset of the opposition so that your rookit might be more resistant to their methodology. As Sun Tzu says, “Know your enemy.” The general approach that I adhere to is the one described by Richard Bejtlich1 in the definitive book on computer forensics. At each step, I’ll explain why an investigator does what he or she does, and as the book progresses I’ll turn around and show you how to undermine an investigator’s techniques.

Everyone Has a Budget: Buy Time

Although there is powerful voodoo at our disposal, the ultimate goal isn’t always achieving complete victory. Sometimes the goal is to make forensic analysis prohibitively expensive; which is to say that raising the bar high enough can do the trick. After all, the analysts of the real world are often constrained by budgets and billable hours. In some police departments, the backlog is so large that it’s not uncommon for a machine to wait up to a year before being analyzed.2 It’s a battle of attrition, and we need to find ways to buy time.

2.1 Incident Response

Think of incident response (IR) as emergency response for suspicious computer events. It’s a planned series of actions performed in the wake of an issue that hints at more serious things. For example, the following events could be considered incidents:

The local intrusion detection system generates an alert.

The local intrusion detection system generates an alert.

The administrator notices odd behavior.

The administrator notices odd behavior.

Something breaks.

Something breaks.

Intrusion Detection System (and Intrusion Prevention System)

An intrusion detection system (IDS) is like an unarmed, off-duty cop who’s pulling a late-night shift as a security guard. An IDS install doesn’t do anything more than sound an alarm when it detects something suspicious. It can’t change policy or interdict the attacker. It can only hide around the corner with a walkie-talkie and call HQ with the bad news.

IDS systems can be host-based (HIDS) and network-based (NIDS). An HIDS is typically a software package that’s installed on a single machine, where it scans for malware locally. An NIDS, in contrast, tends to be an appliance or dedicated server that sits on the network watching packets as they fly by. An NIDS can be hooked up to a SPAN port of a switch, a test access port between the firewall and a router, or simply be jacked into a hub that’s been strategically placed.

In the late 1990s, intrusion prevention systems (IPSs) emerged as a more proactive alternative to the classic IDS model. Like an IDS, an IPS can be host-based (HIPS) or network-based (NIPS). The difference is that an IPS is allowed to take corrective measures once it detects a threat. This might entail denying a malicious process access to local system resources or dropping packets sent over the network by the malicious process.

Having established itself as a fashionable acronym, IPS products are sold by all the usual suspects. For example, McAfee sells an NIPS package,3 as does Cisco (i.e., the Cisco IPS 4200 Series Sensors4). If your budget will tolerate it, Checkpoint sells an NIPS appliance called IPS-1.5 If you’re short on cash, SNORT is a well-known open source NIPS that has gained a loyal following.6

Odd Behavior

In the early days of malware, it was usually pretty obvious when your machine was compromised because a lot of the time the malware infection was the equivalent of an Internet prank. As the criminal element has moved into this space, compromise has become less conspicuous because attackers are more interested in stealing credentials and siphoning machine resources.

In this day and age, you’ll be lucky if your anti-virus package displays a warning. More subtle indications of a problem might include a machine that’s unresponsive, because it’s being used in a DDoS attack, or (even worse) configuration settings that fail to persist because underlying system APIs have been subverted.

Something Breaks

In February 2010, a number of XP systems that installed the MS10-015 Windows update started to experience the Blue Screen of Death (BSOD). After some investigation, Microsoft determined that the culprit was the Alureon rootkit, which placed infected machines in an unstable state.7 Thus, if a machine suddenly starts to behave erratically, with the sort of system-wide stop errors normally associated with buggy drivers, it may be a sign that it’s been commandeered by malware.

2.2 Computer Forensics

If the nature of an incident warrants it, IR can lead to a forensic investigation. Computer forensics is a discipline that focuses on identifying, collecting, and analyzing evidence after an attack has occurred.

The goal of a forensic investigation is to determine:

Who the attacker was (could it be more than one individual?).

Who the attacker was (could it be more than one individual?).

What the attacker did.

What the attacker did.

When the attack took place.

When the attack took place.

How they did it.

How they did it.

Why they did it (if possible: money, ideology, ego, amusement?).

Why they did it (if possible: money, ideology, ego, amusement?).

In other words, given a machine’s current state, what series of events led to this state?

Aren’t Rootkits Supposed to Be Stealthy? Why AF?

The primary design goal of a rootkit is to subvert detection. You want to provide the system’s administrator with the illusion that nothing’s wrong. If an incident has been detected (indicating that something is amiss) and a forensic investigation has been initiated, obviously the rootkit failed to do its job. Why do we care what happens next? Why study AF at all: Wouldn’t it be wiser to focus on tactics that prevent detection or at least conceal the incident when it does? Why should we be so concerned about hindering a forensic investigation when the original goal was to avoid the investigation to begin with?

Many system administrators don’t even care that much about the specifics. They don’t have the time or resources to engage in an in-depth forensic analysis. If a server starts to act funny, they may just settle for the nuclear option, which is to say that they’ll simply:

Shut down the machine.

Shut down the machine.

Flash the firmware.

Flash the firmware.

Wipe the drive.

Wipe the drive.

Rebuild from a prepared disk image.

Rebuild from a prepared disk image.

From the vantage point of an attacker, the game is over. Why invest in AF?

The basic problem here is the assumption that an incident always precedes a forensic analysis. Traditionally speaking, it does. In fact, I presented the IR and forensic analysis this way because it was conceptually convenient. At first blush, it would seem logical that one naturally leads to the other.

But this isn’t always the case …

Assuming the Worst-Case Scenario

In a high-security environment, forensic analysis may be used preemptively. Like any counterintelligence officer, the security professional in charge may assume that machines have been compromised a priori and then devote his or her time to smoking out the intruders. In other words, even if a particular system appears to be perfectly healthy, the security professional will use a rigorous battery of assessment and verification procedures to confirm that it’s trustworthy. In this environment, AF isn’t so much about covering up after an incident is discovered as it is about staying under the radar so that a compromised machine appears secure.

Also, some enlightened professionals realize the strength of field-assessed security as opposed to control-compliant security.8 Richard Bejtlich aptly described this using a football game as an analogy. The control-compliant people, with their fixation on configuration settings and metrics, might measure success in terms of the average height and weight of the players on their football team. The assessment people, in contrast, would simply check the current score to see if their team is winning. The bottom line is that a computer can be completely compliant with whatever controls have been specified and yet hopelessly compromised at the same time. A truly security-conscious auditor will realize this and require that machines be field-assessed before they receive a stamp of approval.

Ultimately, the degree to which you’ll need to use anti-forensic measures is a function of the environment that you’re targeting. In the best-case scenario, you’ll confront a bunch of overworked, apathetic system administrators who could care less what happens just as long as their servers are running and no one is complaining.

Hence, to make life interesting, for the remainder of the book I’m going to assume the worst-case scenario: We’ve run up against a veteran investigator who has mastered his craft, has lots of funding, plenty of mandate from leadership, and is armed with all of the necessary high-end tools. You know the type, he’s persistent and thorough. He documents meticulously and follows up on every lead. In his spare time, he purchases used hard drives online just to see what he can recover. He knows that you’re there somewhere, hell he can sense it, and he’s not giving up until he has dragged you out of your little hidey-hole.

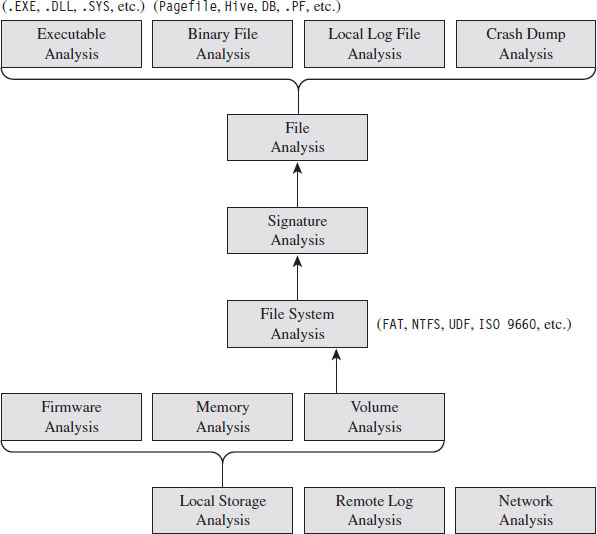

Classifying Forensic Techniques: First Method

The techniques used to perform a forensic investigation can be classified according to where the data being analyzed resides (see Figure 2.1). First and foremost, data can reside either in a storage medium locally (e.g., DRAM, a BIOS chip, or an HDD), in log files on a remote machine, or on the network.

Figure 2.1

On a Windows machine, data on disk is divided into logical areas of storage called volumes, where each volume is formatted with a specific file system (NTFS, FAT, ISO 9660, etc.). These volumes in turn store files, which can be binary files that adhere to some context-specific format (e.g., registry hives, page files, crash dumps, etc.), text-based documents, or executables. At each branch in the tree, a set of checks can be performed to locate and examine anomalies.

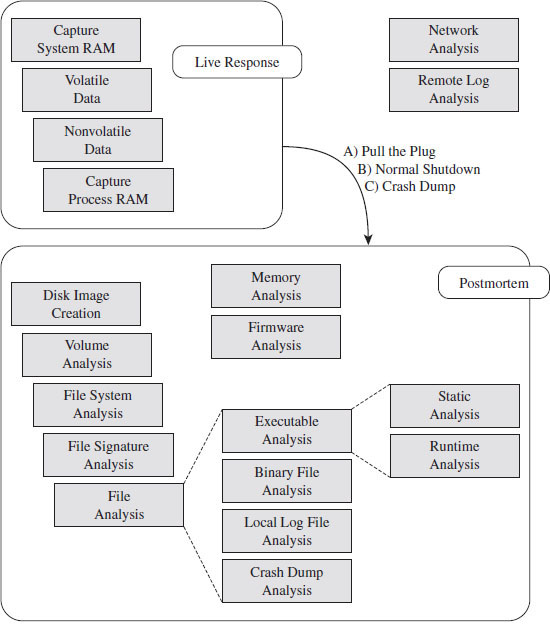

Classifying Forensic Techniques: Second Method

Another way to classify tactics is their chronological appearance in the prototypical forensic investigation. This nature of such an investigation is guided by two ideas:

The “order of volatility.”

The “order of volatility.”

Locard’s exchange principle.

Locard’s exchange principle.

The basic “order of volatility” spelled out by RFC 3227 defines Guidelines for Evidence Collection and Archiving based on degree to which data persists on a system. In particular, see Section 2.1 of this RFC: “When collecting evidence you should proceed from the volatile to the less volatile.”

During the act of collecting data, an investigator normally seeks to heed Locard’s exchange principle, which states that “every contact leaves a trace.” In other words, an investigator understands that the very act of collecting data can disturb the crime scene. So he goes to great lengths to limit the footprint he leaves behind and also to distinguish between artifacts that he has created and the ones that the attacker has left behind.

Given these two central tenets, a forensic investigation will usually begin with a live response (see Figure 2.2).

Live Response

Keeping Locard’s exchange principal in mind, the investigator knows that every tool he executes will increase the size of his footprint on the targeted system. In an effort to get a relatively clear snapshot of the system before he muddies the water, live response often begins with the investigator dumping the memory of the entire system en masse.

Figure 2.2

Once he has captured a memory image of the entire system, the investigator will collect volatile data and then nonvolatile data. Volatile data is information that would be irrevocably lost if the machine suddenly lost power (e.g., the list of running processes, network connections, logon sessions, etc.). Nonvolatile data is persistent, which is to say that we could acquire it from a forensic duplication of the machine’s hard drive. The difference is that the format in which the information is conveyed is easier to read when requested from a running machine.

As part of the live response process, some investigators will also scan a suspected machine from a remote computer to see which ports are active. Discrepancies that appear between the data collected locally and the port scan may indicate the presence of an intruder.

If, during the process of live response, the investigator notices a particular process that catches his attention as being suspicious, he may dump the memory image of this process so that he can dissect it later on.

When Powering Down Isn’t an Option

Once the live response has completed, the investigator needs to decide if he should power down the machine to perform a postmortem, how he should do so, and if he can afford to generate additional artifacts during the process (i.e., create a crash dump). In the event that the machine in question cannot be powered down, live response may be the only option available.

This can be the case when a machine is providing mission critical services (e.g., financial transactions) and the owner literally cannot afford downtime. Perhaps the owner has signed a service level agreement (SLA) that imposes punitive measures for downtime. The issue of liability also rears its ugly head as the forensic investigator may also be held responsible for damages if the machine is shut down (e.g., operational costs, recovering corrupted files, lost transaction fees, etc.). Finally, there’s also the investigative angle. In some cases, a responder might want to keep a machine up so that he can watch what an attacker is doing and perhaps track the intruder down.

The Debate over Pulling the Plug

One aspect of live response that investigators often disagree on is how to power down a machine. Should they perform a normal shutdown or simply yank the power cable (or remove the battery)?

Both schools of thought have their arguments. Shutting down a machine through the appropriate channels allows the machine to perform all of the actions it needs to in order to maintain the integrity of the file system. If you yank the power cable of a machine, it may leave the file system in an inconsistent state.

In contrast, formally shutting down the machine also exposes the machine to shutdown scripts, scheduled events, and the like, which could be maliciously set as booby traps by an attacker who realizes that someone is on to him. I’ll also add that there have been times where I was looking at a compromised machine while the attacker was actually logged on. When the attacker believed I was getting too close for comfort, he shut down the machine himself to destroy evidence. Yanking the power allows the investigator to sidestep this contingency by seizing initiative.

In the end, it’s up to the investigator to use his or her best judgment based on the specific circumstances of an incident.

To Crash Dump or Not to Crash Dump

If the machine being examined can be shut down, creating a crash dump file might offer insight into the state of the system’s internal structures. Kernel debuggers are very powerful and versatile tools. Entire books have been written on crash dump analysis (e.g., Dmitry Vostokov’s Memory Dump Analysis Anthology).

This is definitely not an option that should be taken lightly, as crash dump files can be disruptive. A complete kernel dump consumes gigabytes of disk space and can potentially destroy valuable evidence. The associated risk can be somewhat mitigated by redirecting the dump file to a non-system drive via the Advanced System Properties window. In the best-case scenario, you’d have a dedicated volume strictly for archiving the crash dump.

Postmortem Analysis

If tools are readily available, a snapshot of the machine’s BIOS and PCIROM can be acquired for analysis. The viability of this step varies greatly from one vendor to the next. It’s best to do this step after the machine has been powered down using a DOS boot disk or a live CD so that the process can be performed without the risk of potential interference. Although, to be honest, I wouldn’t get your hopes up. At the first sign of trouble, most system administrators will simply flash their firmware with the most recent release and forego forensics.

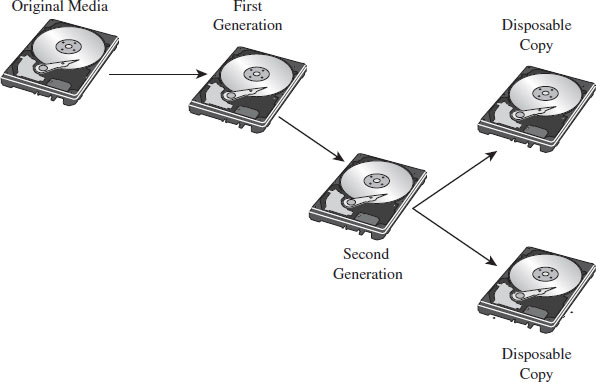

Once the machine has been powered down, a forensic duplicate of the machine’s drives will be created in preparation for file system analysis. This way, the investigator can poke around the directory structure, inspect suspicious executables, and open up system files without having to worry about destroying evidence. In some cases (see Figure 2.3), a first-generation copy will be made to spawn other second-generation copies so that the original medium only has to be touched once before being bagged and tagged by the White Hats.

If the investigator dumped the system’s memory at the beginning of the live response phase, or captured the address space of a particular process, or decided to take the plunge and generate a full-blown crash dump, he will ultimately end up with a set of binary snapshots. The files representing these snapshots can be examined with all the other files that are carved out during the postmortem.

Figure 2.3

Non-Local Data

During either phase of the forensic analysis, if the requisite network logs have been archived, the investigator can gather together all of the packets that were sent to and from the machine being scrutinized. If system-level log data has been forwarded to a central location, this also might be a good opportunity to collect this information for analysis. This can be used to paint a picture of who was communicating with the machine and why. Network taps are probably the best way to capture this data.9

2.3 AF Strategies

Anti-forensics aims to defeat forensic analysis by altering how data is stored and managed. The following general strategies (see Table 2.1) will recur throughout the book as we discuss different tactics. This AF framework is an amalgam of ideas originally presented by The Grugq10 and Marc Rogers.11

Table 2.1 AF Strategies

| Strategy | Tactical Implementations |

| Data destruction | File scrubbing, file system attacks |

| Data concealment | In-band, out-of-band, and application layer concealment |

| Data transformation | Compression, encryption, code morphing, direct edits |

| Data fabrication | Introduce known files, string decoration, false audit trails |

| Data source elimination | Data contraception, custom module loaders |

Recall that you want to buy time. As an attacker, your goal is to make the process of forensic analysis so grueling that the investigator is more likely to give up or perhaps be lured into prematurely reaching a false conclusion (one that you’ve carefully staged for just this very reason) because it represents a less painful, although logically viable, alternative. Put another way: Why spend 20 years agonizing over a murder case when you can just as easily rule it out as a suicide? This explains why certain intelligence agencies prefer to eliminate enemies of the state by means of an “unfortunate accident.”

To reiterate our objective in terms of five concepts:

You want to buy time by leaving as little useful evidence as possible (data source elimination and data destruction).

You want to buy time by leaving as little useful evidence as possible (data source elimination and data destruction).

The evidence you leave behind should be difficult to capture (data concealment) and even more difficult to understand (data transformation).

The evidence you leave behind should be difficult to capture (data concealment) and even more difficult to understand (data transformation).

You can augment the effectiveness of this approach by planting misinformation and luring the investigator into predetermined conclusions (data fabrication).

You can augment the effectiveness of this approach by planting misinformation and luring the investigator into predetermined conclusions (data fabrication).

Data Destruction

Data destruction helps to limit the amount of forensic evidence generated by disposing of data securely after it is no longer needed or by sabotaging data structures used by forensic tools. This could be as simple as wiping the memory buffers used by a program or it could involve repeated overwriting to turn a cluster of data on disk into a random series of bytes. In some cases, data transformation can be used as a form of data destruction.

Rootkits often implement data destruction in terms of a dissolving batch file. One of the limitations of the Windows operating system is that an executing process can’t delete its corresponding binary on disk. But, one thing that an executing process can do is create a script that does this job on its behalf. This script doesn’t have to be a batch file, as the term suggests; it could be any sort of shell script. This is handy for droppers that want to self-destruct after they’ve installed a rootkit.

Data Concealment

Data concealment refers to the practice of storing data in such a manner that it’s not likely to be found. This is a strategy that often relies on security through obscurity, and it’s really only good over the short term because eventually the more persistent White Hats will find your little hacker safe house. For example, if you absolutely must store data on a persistent medium, then you might want to hide it by using reserved areas like the System Volume Information folder.

Classic rootkits rely heavily on active concealment. Usually, this entails modifying the host operating system in some way after the rootkit has launched; the goal being to hide the rootkit proper, other modules that it may load, and activity that the rookit is engaged in. Most of these techniques rely on a trick of some sort. Once the trick is exposed, forensic investigators can create an automated tool to check and see if the trick is being used.

Data Transformation

Data transformation involves taking information and repackaging it with an algorithm that disguises its meaning. Steganography, the practice of hiding one message within another, is a classic example of data transformation. Substitution ciphers, which replace one quantum of data with another, and transposition ciphers, which rearrange the order in which data is presented, are examples of data transformation that don’t offer much security. Standard encryption algorithms like triple-DES, in contrast, are a form of data transformation that can offer a higher degree of security.

Rootkits sometimes use a data transformation technique known as armoring. To evade file signature analysis and also to make static analysis more challenging, a rootkit may be deployed as an encrypted executable that decrypts itself at runtime. A more elaborate instantiation of this strategy is to conceal the machine instructions that compose a rootkit by recasting them in such a way that they appear to be ASCII text. This is known as the English shellcode approach.12

Data Fabrication

Data fabrication is a truly devious strategy. Its goal is to flood the forensic analyst with false positives and bogus leads so that he ends up spending most of his time chasing his tail. You essentially create a huge mess and let the forensic analysts clean it up. For example, if a forensic analyst is going to try and identify an intruder using file checksums, then simply alter as many files on the volume as possible.

Data Source Elimination

Sometimes prevention is the best cure. This is particularly true when it comes to AF. Rather than put all sorts of energy into covering up a trace after it gets generated, the most effective route is one that never generates the evidence to begin with. In my opinion, this is where the bleeding edge developments in AF are occurring.

Rootkits that are autonomous and rely very little (or perhaps even not at all) on the targeted system are using the strategy of data source elimination. They remain hidden not because they’ve altered underlying system data structures, as in the case of active concealment, but because they don’t touch them at all. They aren’t registered for execution by the kernel, and they don’t have a formal interface to the I/O subsystem. Such rootkits are said to be stealthy by design.

2.4 General Advice for AF Techniques

Use Custom Tools

Vulnerability frameworks like Metasploit and application packers like UPX are no doubt impressive tools. However, because they are publicly available and have such a large following, they’ve been analyzed to death, resulting in the identification of well-known signatures and the construction of special-purpose forensic tools. For example, at Black Hat USA 2009, Peter Silberman and Steve Davis led a talk called “Metasploit Autopsy: Reconstructing the Crime Scene”13 that demonstrated how you could parse through memory and recover the command history of a Meterpreter session.

Naturally, a forensic analyst will want to leverage automation to ease his workload and speed things up. There’s an entire segment of the software industry that caters to this need. By developing your own custom tools, you effectively raise the bar by forcing the investigator to reverse your work, and this can buy you enough time to put the investigator at a disadvantage.

Low and Slow Versus Scorched Earth

As stated earlier, the goal of AF is to buy time. There are different ways to do this: noisy and quiet. I’ll refer to the noisy way as scorched earth AF. For instance, you could flood the system with malware or a few gigabytes of legitimate drivers and applications so that an investigator might mistakenly attribute the incident to something other than your rootkit. Another dirty trick would be to sabotage the file system’s internal data structures so that the machine’s disks can’t be mounted or traversed postmortem.

The problem with scorched earth AF is that it alerts the investigator to the fact that something is wrong. Although noisy tactics may buy you time, they also raise a red flag. Recall that we’re interested in the case where an incident hasn’t yet been detected, and forensic analysis is being conducted preemptively to augment security.

We want to reinforce the impression that everything is operating normally. We want to rely on AF techniques that adhere to the low-and-slow modus operandi. In other words, our rootkits should use only those AF tools that are conducive to sustaining a minimal profile. Anything that has the potential to make us conspicuous is to be avoided.

Shun Instance-Specific Attacks

Instance-specific attacks against known tools are discouraged. Recall that we’re assuming the worst-case scenario: You’re facing off against a skilled forensic investigator. These types aren’t beholden to their toolset. Forget Nintendo forensics. The experts focus on methodology, not technology. They’re aware of:

the data that’s available;

the data that’s available;

the various ways to access that data.

the various ways to access that data.

If you landmine one tool, they’ll simply use something else (even if it means going so far as to crank up a hex editor). Like it or not, eventually they’ll get at the data.

Not to mention that forcing a commercial tool to go belly-up and croak is an approach that borders on scorched earth AF. I’m not saying that these tools are perfect. I’ve seen a bunch of memory analysis tools crash and burn on pristine machines (this is what happens when you work with a proprietary OS like Windows). I’m just saying that you don’t want to tempt fate.

Use a Layered Defense

Recall that we’re assuming the worst-case scenario; that forensic tools are being deployed preemptively by a reasonably paranoid security professional. To defend ourselves, we must rely on a layered strategy that implements in-depth defense: We must use several anti-forensic tactics in concert with one another so that the moment investigators clear one hurdle, they slam head first into the next one.

It’s a battle of attrition, and you want the other guy to cry “Uncle” first. Sure, the investigators will leverage automation to ease their load, but there’s always that crucial threshold where relying on the output of an expensive point-and-click tool simply isn’t enough. Like I said earlier, these guys have a budget.

2.5 John Doe Has the Upper Hand

In the movie Se7en, there’s a scene near the end where a homicide detective played by Morgan Freeman realizes that the bad guy, John Doe, has outmaneuvered him. He yells over his walkie-talkie to his backup: “Stay away now, don’t - don’t come in here. Whatever you hear, stay away! John Doe has the upper hand!”

In a sense, as things stand now, the Black Hats have the upper hand. Please be aware that I’m not dismissing all White Hats as inept. The notion often pops up in AF circles that forensic investigators are a bunch of idiots. I would strongly discourage this mindset. Do not, under any circumstances, underestimate your opponent. Nevertheless, the deck is stacked in favor of the Black Hats for a number of reasons.

Attackers Can Focus on Attacking

An advanced persistent threat (APT) is typically tasked with breaking in, and he can focus all of his time and energy on doing so; he really only needs to get it right once. Defenders must service business needs. They can’t afford to devote every waking hour to fending off wolves. Damn it, they have a real job to do (e.g., unlock accounts, service help desk tickets, respond to ungrateful users, etc.). The battle cry of every system administrator is “availability,” and this dictate often trumps security.

Defenders Face Institutional Challenges

Despite the clear and present threats, investigators are often mired by a poorly organized and underfunded bureaucracy. Imagine being the director of incident response in a company with more than 300,000 employees and then having to do battle with the folks in human resources just to assemble a 10-man computer emergency response team (CERT). This sort of thing actually happens. Now you can appreciate how difficult it is for the average security officer at a midsize company to convince his superiors to give him the resources he needs. As Mandiant’s Richard Bejtlich has observed: “I have encountered plenty of roles where I am motivated and technically equipped, but without resources and power. I think that is the standard situation for incident responders.”14

Security Is a Process (and a Boring One at That)

Would you rather learn how to crack safes or spend your days stuck in the tedium of the mundane procedures required to properly guard the safe?

Ever-Increasing Complexity

One might be tempted to speculate that as operating systems like Windows evolve, they’ll become more secure, such that the future generations of malware will dwindle into extinction. This is pleasant fiction at best. It’s not that the major players don’t want to respond, it’s just that they’re so big that their ability to do so in a timely manner is constrained. The procedures and protocols that once nurtured growth have become shackles.

For example, according to a report published by Symantec, in the first half of 2007 there were 64 unpatched enterprise vulnerabilities that Microsoft failed to (publicly) address.15 This is at least three times as many unpatched vulnerabilities as any other software vendor (Oracle was in second place with 13 unpatched holes). Supposedly Microsoft considered the problems to be of low severity (e.g., denial of service on desktop platforms) and opted to focus on more critical issues.

According to the X-Force 2009 Trend and Risk Report released by IBM in February 2010, Microsoft led the pack in both 2008 and 2009 with respect to the number of critical and high operating system vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities are the severe ones, flaws in implementation that most often lead to complete system compromise.

One way indirectly to infer the organizational girth of Microsoft is to look at the size of the Windows code base. More code means larger development teams. Larger development teams require additional bureaucratic infrastructure and management support (see Table 2.2).

Looking at Table 2.2, you can see how the lines of code spiral ever upward. Part of this is due to Microsoft’s mandate for backwards compatibility. Every time a new version is released, it carries requirements from the past with it. Thus, each successive release is necessarily more elaborate than the last. Complexity, the mortal enemy of every software engineer, gains inertia.

Microsoft has begun to feel the pressure. In the summer of 2004, the whiz kids in Redmond threw in the towel and restarted the Longhorn project (now Windows Server 2008), nixing 2 years worth of work in the process. What this trend guarantees is that exploits will continue to crop up in Windows for quite some time. In this sense, Microsoft may very well be its own worst enemy.

Table 2.2 Windows Lines of Code

| Version | Lines of Code | Reference |

| NT 3.1 | 6 million | “The Long and Winding Windows NT Road,” Business-Week, February 22, 1999 |

| 2000 | 35 million | Michael Martinez, “At Long Last Windows 2000 Operating System to Ship in February,” Associated Press, December 15, 1999 |

| XP | 45 million | Alex Salkever, “Windows XP: A Firewall for All,” Business-Week, June 12, 2001 |

| Vista | 50 million | Lohr and Markoff, “Windows Is So Slow, but Why?” New York Times, March 27, 2006 |

ASIDE

Microsoft used to divulge the size of their Windows code base, perhaps to indicate the sophistication of their core product. In fact, this information even found its way into the public record. Take, for instance, the time when James Allchin, then Microsoft’s Platform Group Vice President, testified in court as to the size of Windows 98 (he guessed that it was around 18 million lines).16 With the release of Windows 7, however, Redmond has been perceptibly tight-lipped.

2.6 Conclusions

This chapter began by looking at the dance steps involved in the average forensic investigation, from 10,000 feet, as a way to launch a discussion of AF. What we found was that it’s possible to subvert forensic analysis by adhering to five strategies that alter how information is stored and managed in an effort to:

Leave behind as little useful evidence as possible.

Leave behind as little useful evidence as possible.

Make the evidence that’s left behind difficult to capture and understand.

Make the evidence that’s left behind difficult to capture and understand.

Plant misinformation to lure the investigator to predetermined conclusions.

Plant misinformation to lure the investigator to predetermined conclusions.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, rootkit technology is a subset of AF that relies exclusively on low-and-slow stratagems. The design goals of a rootkit are to provide three services: remote access, monitoring, and concealment. These services can be realized by finding different ways to manipulate system-level components. Indeed, most of this book will be devoted to this task using AF as a framework within which to introduce ideas.

But before we begin our journey into subversion, there are two core design decisions that must be made. Specifically, the engineer implementing a root-kit must decide:

What part of the system they want the rootkit to interface with.

What part of the system they want the rootkit to interface with.

Where the code that manages this interface will reside.

Where the code that manages this interface will reside.

These architectural issues depend heavily on the distinction between Windows kernel-mode and user-mode execution. To weigh the trade-offs inherent in different techniques, we need to understand how the barrier between kernel mode and user mode is instituted in practice. This requirement will lead us to the bottom floor, beneath the sub-basement of system-level software: to the processor. Inevitably, if you go far enough down the rabbit hole, your pursuit will lead you to the hardware.

Thus, we’ll spend the next chapter focusing on Intel’s 32-bit processor architecture (Intel’s documentation represents this class of processors using the acronym IA-32). Once the hardware underpinnings have been fleshed out, we’ll look at how the Windows operating system uses facets of the IA-32 family to offer memory protection and implement the great divide between kernel mode and user mode. Only then will we finally be in a position where we can actually broach the topic of rootkit implementation.

1. Richard Bejtlich, Keith Jones, and Curtis Rose, Real Digital Forensics: Computer Security and Incident Response, Addison-Wesley Professional, 2005.

2. Nick Heath, “Police in Talks over PC Crime ‘Breathalysers’ Rollout,” silicon.com, June 3, 2009.

3. http://www.mcafee.com/us/enterprise/products/network_security/.

4. http://www.cisco.com/en/US/products/hw/vpndevc/ps4077/index.html.

5. http://www.checkpoint.com/products/ips-1/index.html.

7. http://blogs.technet.com/msrc/archive/2010/02/17/update-restart-issues-after-installingms10-015-and-the-alureon-rootkit.aspx.

8. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2006/07/control-compliant-vs-field-assessed.html.

9. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2009/01/why-network-taps.html.

10. The Grugq, “Defeating Forensic Analysis on Unix,” Phrack, Issue 59, 2002.

11. Marc Rogers, “Anti-Forensics” (presented at Lockheed Martin, San Diego, September 15, 2005).

12. Joshua Mason, Sam Small, Fabian Monrose, and Greg MacManus, English Shellcode, ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2009.

13. http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-usa-09/SILBERMAN/BHUSA09-Silberman-MetasploitAutopsy-PAPER.pdf.

14. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2008/08/getting-job-done.html.

15. Government Internet Security Threat Report, Symantec Corporation, September 2007, p. 44.

16. United States vs. Microsoft, February 2, 1999, AM Session.