Chapter 15 Going Out-of-Band

Our quest to foil postmortem analysis led us to opt for memory-resident tools. Likewise, in an effort to evade memory carving tools at runtime, we decided to implement our rootkit using kernel-mode shellcode. Nevertheless, in order to score some CPU time, somewhere along the line we’ll have to modify the targeted operating system so that we can embezzle a few CPU cycles. To this end, the options we have at our disposal range from sophomoric to subtle (see Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Ways to Capture CPU Time

| Strategy | Tactic | Elements Altered |

| Modify static elements | Hooking | IAT, SSDT, GDT, IDT, MSRs |

| In-place patching | System calls, driver routines | |

| Detour patching | System calls, driver routines | |

| Modify dynamic elements | Alter repositories | Registry hives, event logs |

| DKOM | EPROCESS, DRIVER_SECTION structures | |

| Alter callbacks | PE image .data section |

With enough digging, these modifications could be unearthed. However, that’s not to say that the process of discovery itself would be operationally feasible or that our modifications would even be recognized for what they are. In fact, most forensic investigators (who are honest about it) will admit that a custom-built shellcode rootkit hidden away in the far reaches of kernel space would probably go undetected.

Nevertheless, can we push the envelope even farther? For instance, could we take things to the next level by using techniques that allow us to remain concealed without altering the target operating system at all? In the spirit of data source elimination, could we relocate our code outside of the OS proper and manipulate things from this out-of-band vantage point? That’s what this chapter is all about.

Note: The term out-of-band is used both in networking and in system management. Put roughly, it refers to communication/access that occurs outside of the normal established channels (whatever the normal channels may be, it’s sort of context sensitive). In this case, we’re interacting with the targeted computer from an unorthodox location.

As I mentioned earlier in the book, the techniques we’ll examine in this chapter highlight a recurring trend. Vendors attempt to defend against malware by creating special fortified regions of execution (e.g., additional rings of privilege in memory, dedicated processor modes, hardware-level security add-ons, etc.). At first glance this might seem to be a great idea, until the malware that security architects are trying to counter eventually weasels its way inside of the castle gate and takes up residence in these very same fortified zones.

Ways to Jump Out-of-Band

The operating system doesn’t exist in isolation. If you dive down toward the HAL, so to speak, eventually you cross the border into hardware. This is the final frontier of rootkit design, to subsist in the rugged terrain that’s home to chipsets and firmware. Here, in the bleak outer reaches, you’ll have to survive without the amenities that you had access to in the relatively friendly confines of user mode and kernel mode. In this journey down into the hardware, there are basically three different outposts that you can use to stash an out-of-band rootkit.

Additional processor modes.

Additional processor modes.

Firmware.

Firmware.

Lights-out management facilities.

Lights-out management facilities.

Over the course of this chapter, I’ll survey each of these options and examine the trade-offs associated with each one.

15.1 Additional Processor Modes

Recall that the mode of an Intel processor determines how it operates. Specifically, the processor’s mode determines how it organizes memory, which machine instructions it understands, and the architectural features that are available. The IA-32 architecture supports three modes:

Real mode.

Real mode.

Protected mode.

Protected mode.

System management mode (SMM).

System management mode (SMM).

We’re already intimately familiar with real mode and protected mode, so in this chapter we’ll look at SMM in greater detail.

Intel processors that support virtualization also implement two additional modes:

Root mode.

Root mode.

Non-root mode.

Non-root mode.

In root mode, the processor executes with an even higher level of privilege than that of kernel mode and has complete control over the machine’s hardware. Root mode also gives the processor access to a special subset of instructions that are a part of Intel’s Virtual-Machine eXtensions (VMX). These VMX instructions are what allow the processor to manage guest virtual machines. The virtual machines run in non-root mode, where the efficacy of the VMX instructions has been hobbled to limit their authority.

Note: With rootkits that run in SMM or that act as rogue hypervisors, we’re not necessarily exploiting a hardware-level flaw as much as we’re simply leveraging existing functionality. Both technologies are legitimate and well documented. It’s just that we’re using them to remain concealed.

System Management Mode

Historically speaking, SMM has been around much longer than the hardware features that support virtualization. So I’m going to start by looking at SMM. Pedants would point out that SMM rootkits are more powerful than rogue hypervisors (and they’d be correct), but we’ll touch on that later.

What is SMM used for, exactly?

According to the official Intel documentation:

“SMM is a special-purpose operating mode provided for handling system-wide functions like power management, system hardware control, or proprietary OEM designed code. It is intended for use only by system firmware, not by applications software or general-purpose systems software. The main benefit of SMM is that it offers a distinct and easily isolated processor environment that operates transparently to the operating system or executive and software applications.”

The reference to transparent operation hints at why SMM is interesting. What the documentation is saying, in so many words, is that SMM provides us with a way to execute machine instructions in a manner that’s hidden from the targeted operating system.

Note: As I stated at the beginning of this section, SMM is not a recent development. It’s been around since the introduction of the Intel 80386 SL processor (circa October 1990).1 The 80386 SL was a mobile version of the 80386, and power management was viewed as a priority.

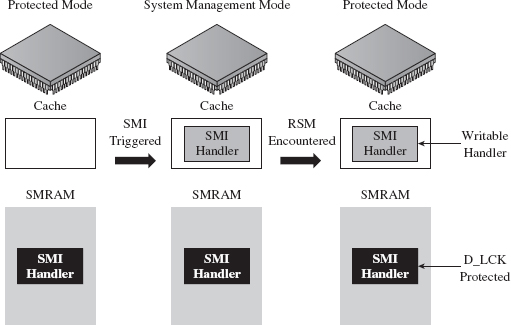

In broad brushstrokes, the transfer of a processor to SMM occurs as follows.

A system management interrupt (SMI) occurs.

A system management interrupt (SMI) occurs.

The processor saves its current state in system management RAM (SMRAM).

The processor saves its current state in system management RAM (SMRAM).

The processor executes the SMI handler, which is also located in SMRAM.

The processor executes the SMI handler, which is also located in SMRAM.

The processor eventually encounters the RSM instruction (e.g., resume).

The processor eventually encounters the RSM instruction (e.g., resume).

The processor loads its saved state information and resumes normal operation.

The processor loads its saved state information and resumes normal operation.

In a nutshell, the operating system is frozen in suspended animation as the CPU switches to the alternate universe of SMM-land where it does whatever the SMI handler tells it to do until the RSM instruction is encountered. The SMI handler is essentially its own little operating system; a microkernel of sorts. It runs with complete autonomy, which is a nice way of saying that you don’t have the benefit of the Windows low-level infrastructure. If you want to communicate with hardware, fine: you get to write the driver code. With great stealth comes great responsibility.

An SMI is just another type of hardware-based interrupt. The processor can receive an SMI via its SMI# pin or an SMI message on the advanced programmable interrupt controller (APIC) bus. For example, an SMI is generated when the power button is pressed, upon USB wake events, and so forth. The bad news is that there’s no hardware-agnostic way to generate an SMI (e.g., the INT instruction). Most researchers seem to opt to generate SMIs as an indirect result of programmed input/output (PIO), which usually entails assembly language incantations sprinkled liberally with the IN and OUT assembler instructions. In other words, they talk to the hardware with PIO and get it to do something that will generate an SMI as an indirect consequence.

Note: While the processor is in SMM, subsequent SMI signals are ignored (i.e., SMM non-reentrant). In addition, all of the interrupts that the operating system would normally handle are disabled. In other words, you can expect debugging your SMI handler to be a royal pain in the backside. Welcome to the big time.

Once an SMI has been received by the processor, it saves its current state in a dedicated region of physical memory: SMRAM. Next, it executes the SMI interrupt handler, which is also situated in SMRAM. Keep in mind that the handler’s stack and data sections reside in SMRAM as well. In other words, all the code and data that make up the SMI handler are confined to SMRAM.

The processor proceeds to execute instructions in SMM until it reaches an RSM instruction. At this point, it reloads the state information that it stashed in SMRAM and resumes executing whatever it was doing before it entered SMM. Be warned that the RSM instruction is only recognized while the processor is in SMM. If you try to execute RSM in another processor mode, the processor will generate an invalid-opcode exception.

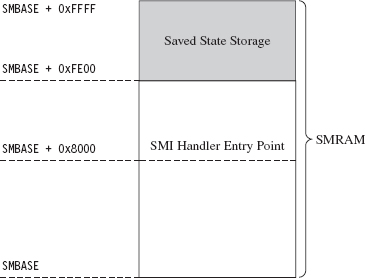

By default, SMRAM is 64 KB in size. This limitation isn’t etched in stone. In fact, SMRAM can be configured to occupy up to 4 GB of physical memory. SMRAM begins at a physical address that we’ll refer to abstractly as SM-BASE. According to Intel’s documentation, immediately after a machine is reset, SMBASE is set to 0x30000 such that the default range of SMRAM is from 0x30000 to 0x3FFFF (see Figure 15.1). Given that the system firmware can recalibrate the parameters of SMRAM at boot time, the value of SMBASE and the address range that constitutes SMRAM can vary. Ostensibly, this allows each processor on a multiprocessor machine to have its own SMRAM.

Figure 15.1

Note: The processor has a special register just for storing the value of SMBASE. This register cannot be accessed directly, but it is stored in SMRAM as a part of the processor’s state when an SMI is triggered. As we’ll see, this fact will come in handy later on.

The processor expects the first instruction of the SMI handler to reside at the address SMBASE + 0x8000. It also stores its previous state data in the region from SMBASE + 0xFE00 to SMBASE + 0xFFFF.

In SMM, the processor acts kind of like it’s back in real mode. There are no privilege levels or linear address mappings. It’s just you and physical memory. The default address and operand size is 16 bits, though address-size and operand-size override prefixes can be used to access a 4-GB physical address space. As in real mode, you can modify everything you can address. This is what makes SMM so dangerous: It gives you unfettered access to the kernel’s underlying data structures.

Access to SMRAM is controlled by flags located in the SMRAM control register (SMRAMC). This special register is situated in the memory controller hub (MCH), the component that acts as the processor’s interface to memory, and the SMRAMC can be manipulated via PIO. The SMRAM control register is an 8-bit register, and there are two flags that are particularly interesting (see Table 15.2).

Table 15.2 SMRAM Control Register Flags

| Flag Name | Bits | Description |

| D_LCK | 4 | When set, the SMRAMC is read-only and D_OPEN is cleared |

| D_OPEN | 6 | When set, SMRAM can be accessed by non-SMM code |

When a machine restarts, typically D_OPEN will be set so that the BIOS can set up SMRAM and load a proper SMI handler. Once this is done, the BIOS is in a position where it can set the D_LCK flag (thus clearing D_OPEN as an intended side-effect; see Table 15.2) to keep the subsequently loaded operating system from violating the integrity of the SMI handler.

As far as publicly available work is concerned, a few years ago at CanSecWest 2006, Loïc Duflot presented a privilege escalation attack that targeted OpenBSD.2 Specifically, he noticed that the D_LCK flag was cleared by default on many desktop platforms. This allowed him to set the D_OPEN flag using PIO and achieve access to SMRAM from protected mode. Having toggled the D_OPEN bit, from there it’s a simple matter of loading a custom SMI handler into SMRAM and triggering an SMI to execute the custom handler. This handler, which has unrestricted access to physical memory, can alter the OpenBSD kernel to increase its privileges.

Duflot’s slide deck from CanSecWest assumes a certain degree of sophistication on behalf of the reader. For those of you not familiar with the nuances of the associated chipsets, I recommend looking at an article in issue 65 of Phrack entitled “System Management Mode Hack: Using SMM for ‘Other Purposes.’”3 This readable treatise on SMM, written by the likes of BS-Daemon, coideloko, and D0nAnd0n, wades deeper into the hardware-level backdrop surrounding SMM. It also provides a portable library to manipulate the SMRAM control register. This article is definitely worth a read.

At Black Hat DC in 2008, Shawn Embleton and Sherri Sparks presented an SMM-based rootkit (SMBR) that built on Duflot’s work.4 Essentially, they created an SMI handler that communicated directly with the hardware to log keystrokes and then transmit the pilfered data to a remote IP address. It’s interesting to note that on laptops (where power management is crucial), they found it necessary to “hook” the preexisting SMM handler so that they could forward non-rootkit SMI events to the old handler. Without this work-around, modified laptops tended to become unstable due to the frequency of power-related SMI events.

By this time, the vendors started to wise up. In particular, they altered the boot process so that the BIOS explicitly set the D_LCK flag after establishing the original SMI handler. This way, D_OPEN would be automatically cleared (precluding access to SMRAM), and the SMRAM control register would be placed in a read-only state so that D_OPEN could not be further modified by an intruder.

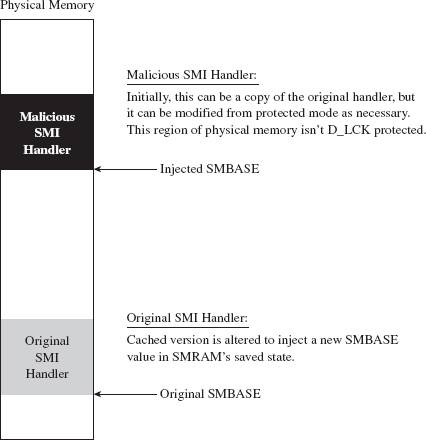

As it turns out, there were two independent research teams working on bypassing this safeguard in parallel. In France, Loïc Duflot and friends were hard at work.5 They discovered that you could use some machine-specific registers, called the memory type range registers (MTRRs), to force the memory containing the SMI handler to be cached when accessed. Furthermore, this cached copy (by virtue of the fact that it resides in an on-chip cache) can be altered (see Figure 15.2).

Figure 15.2

Basically, Duflot’s team modified the cached SMI handler to update the SMBASE value stored in the saved state region of SMRAM. This way, when the processor reloaded its state information, it would end up with a new value in its internal SMBASE register. This gave them the ability to establish and execute a malicious SMI handler in another region of memory, a location not protected by the D_LCK flag (see Figure 15.3). This general approach is what’s known as a cache poisoning strategy. Very clever!

Meanwhile, in Poland, Joanna Rutkowska and her cohorts at Invisible Things Lab were developing a cache poisoning attack that was similar to Duflot’s.6 Additional details on the lab’s SMM-related work were also presented at Black Hat USA 2009.7

Rogue Hypervisors

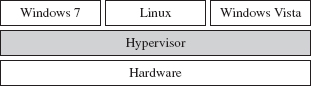

A hypervisor is a low-level layer of software that allows a computer to share its resources so that it can run more than one operating system at a time. To get an intuitive feel for the meaning of this otherwise sci-fi sounding word, think “supervisor” when you see the term “hypervisor.” The operating systems that execute on top of the hypervisor, known as guests, interact with the outside through synthetic hardware, which constitutes a virtual machine. Hence, a hypervisor is often called a virtual machine monitor (VMM). So, what you end up with is a bunch of virtual machines running concurrently on a single physical machine (see Figure 15.4).

Figure 15.3

Figure 15.4

Note: In this discussion, I’m going to stick exclusively to hypervisors that run directly on top of the hardware such that guest operating systems are, to a degree, insulated from direct access to physical devices. This sort of hypervisor is known as a bare metal, type 1, or native hypervisor.

Using a hypervisor, a system administrator can take all of a computer’s physical processors, memory, and disk space and partition it up among competing applications. In this manner, the administrator can limit resource consumption by any particular set of programs. It also helps to ensure that a single buggy application can’t bring down the entire system, even if it succeeds in crashing the virtual machine that’s hosting it. These features help to explain why a hypervisor setup is often referred to as a managed environment.

In spite of all of the marketing hype, historically speaking this is mainframe technology that has filtered down to the midrange as multiprocessor systems have become more commonplace. IBM has been using hypervisors since the late 1960s. It wasn’t until 2005 that hardware vendors like Intel and AMD provided explicit support for virtualization. As hardware support emerged, software vendors like Microsoft and VMware rushed in to leverage it.

Intel support for bare-metal hypervisors (called Intel Virtualization Technology, or simply Intel-VT) began with the introduction of the Intel Pentium 4 processor models 672 and 662. Virtualization is implemented using a set of special instructions and collection of processor-mandated data structures that are referred to in aggregate as Virtual-Machine eXtensions (VMX). There are two different types of VMX operation. As stated earlier, the hypervisor will execute when the processor is in VMX root mode, and the guest operating systems will execute while the processor is in VMX non-root mode.

AMD offers a very similar virtualization technology (i.e., AMD-V), but uses a slightly different vernacular. For example, instead of root mode, AMD calls it host mode. Instead of non-root mode, AMD uses the term guest mode. Intel’s VMX acronym is replaced by AMD’s SVM (as in Security and Virtual Machine architecture).

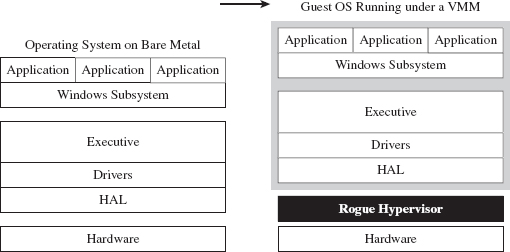

The basic idea behind a rogue hypervisor attack is that a rootkit could surreptitiously install itself as a hypervisor, ensnare the currently running operating system (which is initially executing on bare metal), and trap it inside of a virtual machine. From there, the rootkit can safely manipulate the running instance from the outside (see Figure 15.5). Researchers have used the acronym VMBR, as in virtual machine-based rootkit, to refer to this kind of malicious hypervisor.

This is exactly the approach taken by the Blue Pill Project, a rootkit proof-of-concept developed by Joanna Rutkowska, Alexander Tereshkin, and Rong Fan. The first version of Blue Pill was conceived while Joanna was doing research for COSEINC, and it used AMD’s SVM platform. She gave a briefing on this work at Black Hat USA 2006.8 After Joanna left COSEINC, in spring 2007, she teamed up with Alexander and Rong to develop a cleanroom implementation of Blue Pill that supported both Intel VMX and AMD SVM technology.

Figure 15.5

There were other research teams working on malicious hypervisors right around the same time period. For example, in 2006 a joint project between the University of Michigan and Microsoft Research produced a VMBR known as SubVirt.9 Likewise, at Black Hat USA 2006, Dino Dai Zovi presented a VMBR called Vitriol that used Intel VMX.10

Of the three sample implementations, Blue Pill appears to be the most sophisticated (though, who knows what’s been privately developed and deployed in the wild). Blue Pill handles both Intel and AMD platforms, can install itself at run time, can remain memory resident to foil a postmortem disk analysis, and accommodates novel countermeasures to thwart detection.11

So far, we’ve examined the case where an intruder installs and then deploys a custom-built hypervisor. Why not simply compromise an existing hypervisor and turn it into a double agent of sorts? This is exactly the strategy posed by Rafal Wojtczuk at Black Hat USA in 2008. In his presentation, he demonstrated how to subvert the Xen hypervisor using a DMA attack to modify physical memory and install a back door.12 This approach is advantageous because an attacker doesn’t have to worry about hiding the fact that a hypervisor has been installed. It also conserves development effort because the attacker can leverage the existing infrastructure to get things done.

White Hat Countermeasures

As Black Hats and their ilk have been devising ways to make use of hypervisors to conceal malicious payloads, the White Hats have also been hard at work identifying techniques that use virtualization technology to safeguard systems. For example, in 2009 a research team from North Carolina State University presented a proof-of-concept tool at the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)’s Conference on Computer and Communications Security.13 Their tool, which they christened HookSafe, is basically a lightweight hypervisor that enumerates a set of sensitive spots in kernel space (e.g., regions that a kernel-mode rootkit might try to alter) and relocates them to another location where access is more carefully regulated.

But what if the rootkit is, itself, a hypervisor and not just a garden-variety kernel-mode rootkit? Naturally, you’ve got to go down one level deeper. One researcher from Intel, Yuriy Bulygin, suggested that you could rely on embedded microcontrollers that reside in the motherboard’s north-bridge to keep an eye out for VMBRs. He presented his proof of concept, called DeepWatch, at Black Hat 2008.14 His general idea was extended upon by the research team at Invisible Things, in the form of a tool called HyperGuard, which uses a custom SMI handler in conjunction with onboard chipsets to protect against malicious hypervisors.15

More recently, some of the researchers involved with the development of HookSafe came out with a software-based solution, known as HyperSafe, which monitors a computer for rogue hypervisors. This effort was funded in part by the U.S. Army Research Office, and a fairly detailed description of the tool’s inner workings was presented at the 2010 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy.16 Personally, as you may have guessed, I’m a bit dubious of any tool that relies strictly on software to guarantee system integrity.

At the time of this book’s writing, the researchers at Invisible Things announced that they had developed an open source operating system, Qubes OS, which draws heavily on the Xen hypervisor to provide security through isolation.17 Their architecture enables application-specific virtual machines to be launched, executed, and then reverted back to a known secure state. This way, if your browser gets compromised, the system, as a whole, won’t suffer because the browser is limited to the confines of its own virtual environment.

ASIDE

Isolation could be seen as the pragmatist’s route to better security. Hey, it worked for the KGB, although they called it compartmentalization. A more rigorous strategy would be to rely exclusively on software that has proved (e.g., mathematically) to be correct. For the time being, this is impracticable as it would require original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) and system vendors to essentially go back to the drawing board with regard to hardware and software design. Yet, steps have been taken in this direction. Specifically, at the 22nd ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP) in 2009, a group of researchers from Australia presented a general-purpose kernel, known as seL4, which could be formally proved to be functionally correct.18 I suspect that formal correctness may end up being the long-term solution even if it’s not feasible over the short term.

Rogue Hypervisors Versus SMM Rootkits

Both VMBRs and SMBRs use special processor modes to stay concealed. So which one is more powerful? Well, intuitively, the fact that a tool like Hyper-Guard uses an SMI handler should help indicate which region offers a better vantage point for an attacker. But, personally, I don’t think that this alone is really sufficient enough to declare that SMBRs are the king of all rootkits. In the end, it really comes down to what your priorities are.

For example, because SMM has been around longer, it offers a larger pool of potential targets. However, SMBRs are more difficult to build. As I mentioned earlier, there really is no built-in debugger support in SMM, and (trust me) there are times when you’re going to wish you had a debugger. Not to mention that the SMM environment is more hostile/foreign. VMBRs operate with access to familiar protected-mode memory features like paging. All SMBRs get is a flat physical address space, and that’s it. As I’ve observed before, there’s usually a trade-off between the level of stealth you attain and development effort involved.

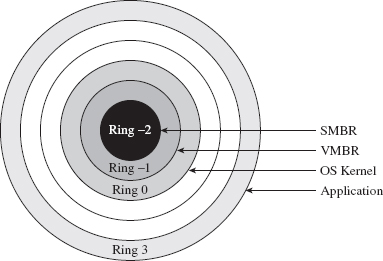

At the same time, SMM code runs with greater privilege than a hypervisor. Specifically, an SMI handler can lock down access to SMRAM so that not even a hypervisor can access it. Likewise, an SMI handler has unrestricted access to the memory containing the resident hypervisor. This is one reason why VMBRs are referred to as Ring – 1 rootkits, and SMBRs are referred to as Ring – 2 rootkits (see Figure 15.6).

Figure 15.6

15.2 Firmware

SMBRs and VMBRs rely on legitimate, well-documented processor features. Now let’s plunge deeper down the rabbit hole into less friendly territory and explore other low-level components that can be used to facilitate a rootkit.

Mobo BIOS

The motherboard’s BIOS firmware is responsible for conducting basic hardware tests and initializing system devices in anticipation of the OS bootstrap process. As we saw earlier in the first part of this book, at some point the BIOS loads the OS boot loader from disk into memory, at some preordained location, and officially hands off execution. This is where BIOS-based subversion tends to begin. In this scenario, the attacker will somehow modify the BIOS iteratively to patch the operating system as it loads to both disable security functionality and establish an environment for a malicious payload.

A common tactic, which is also a mainstay of bootkits,19 is to hook the 0x13 real-mode interrupt (e.g., which is used for primitive disk I/O) and scan bytes read from disk for the file signature of the operating system’s boot manager. Once the boot manager is detected, it can be patched before it gets a chance to execute. As additional system components are loaded into memory, they too can be iteratively patched by previously patched components. Once you’ve preempted the operating system and acquired a foothold in the system, you’re free to undermine whatever OS feature you please, as Peter Kleissner can readily attest.20

At this point, I should issue a disclaimer: I can’t possibly cover even a fraction of the material that this topic deserves. The best I can do is to provide enough background material so that you can hit the ground running with the reference pointers that I provide. Once more, I’d be sorely pressed to offer a recipe that would be generally useful, as when we hunker down into the hardware, it’s pretty much nothing but instance-specific details.

In all honesty, this topic is broad enough and deep enough that it probably deserves a book in and of itself. In fact, such a book exists, and it isn’t a bad read in my humble opinion (though it sticks primarily to the Award BIOS).21 If you want an executive-style summary of Salihun’s book, I’d recommend digging into the presentation that Anibal Sacco and Alfredo Ortega gave at CanSecWest Vancouver 2009, entitled Persistent BIOS Infection.22

Much of what’s done in the area of BIOS subversion is the work of independent researchers working within a limited budget in an after-hours type setting (e.g., a year’s worth of Sunday afternoons). The results tend to be software geared toward proof of concept. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, as POC code can be an excellent learning tool. Nevertheless, to see what’s possible when you have a funded effort, we can examine a product called Computrace, which is sold by Absolute Software.23 Computrace is what’s known as inventory tracking software. It’s used to allow system administrators to locate lost or stolen computers (laptops especially).

In the spirit of a hybrid rootkit, the Computrace product consists of two components:

Application agent.

Application agent.

Persistence module.

Persistence module.

The application agent is installed in the operating system as a nondescript service named “Remote Procedure Call (RPC) Net” (i.e., %windir%\system32\ rpcnet.exe). In this case, the binary is simply attempting to hide in a crowd by assuming a description that could be easily confused for something else (see Figure 15.7).

Figure 15.7

The persistence module exists to ensure the presence of the application agent and to re-install it in the event that someone, like a thief, reformats the hard drive. Several hardware OEMs have worked with Absolute Software to embed the persistence module at the BIOS level.24 One can only imagine how effective an attack could be if such low-level persistence technology were commandeered. You’d essentially have a self-healing rootkit. At Black Hat USA in 2009, our friends Sacco and Ortega discussed ways to subvert Computrace to do just that.25

Although patching the BIOS firmware is a sexy attack vector, it doesn’t come without trade-offs. First and foremost, assuming you actually succeed in patching the BIOS firmware, you’ll probably need to initiate a reboot in order for it to take effect. Depending on your target, this can be a real attention grabber.

Then there’s also the inconvenient fact that patching the BIOS isn’t as easy as it used to be. Over the years, effective security measures have started to gain traction. For instance, some motherboards have been designed so that they only allow the vendor’s digitally signed firmware to be flashed. This sort of defense can take significant effort to surmount.

Leave it to Invisible Things to tackle the unpleasant problems in security. At Black Hat USA in 2009, Rafal Wojtczuk and Alexander Tereshkin explained how they found a way to re-flash the BIOS on Intel Q45-based desktop machines.26 Using an elaborate heap overflow exploit, they showed how it was possible to bypass the digital signature verification that’s normally performed. Granted, this attack requires administrator access and a reboot to succeed. But it can also be initiated remotely without the user’s knowledge. The moral of the story: be very suspicious of unplanned restarts.

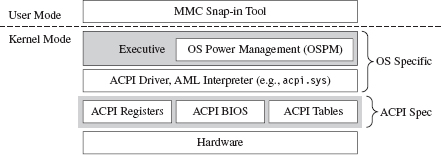

ACPI Components

The Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI) specification is an industry standard that spells out BIOS-level interfaces that enable OS-directed power management.27 ACPI doesn’t mandate how the corresponding software or hardware should be implemented; it defines the manner in which they should communicate (ACPI is an interface specification) (see Figure 15.8).

Figure 15.8

An implementation of the ACPI specification is composed of three elements:

The ACPI system description tables.

The ACPI system description tables.

The ACPI registers.

The ACPI registers.

The ACPI BIOS.

The ACPI BIOS.

The ACPI BIOS is merely that part of the motherboard BIOS that’s compliant with the ACPI specification. Likewise, there’s nothing that surprising about the ACPI registers either: just another set of hardware-level cubby holes.

The description tables are worth delving into a little. They’re used in a manner that’s consistent with their name; they describe the machine’s hardware. Here’s the catch: ACPI description tables may also include definition blocks, which can store a platform-neutral bytecode called ACPI Machine Language (AML). The indigenous operating system is responsible for interpreting this bytecode and executing it. Usually, the system will use an ACPI driver to implement this functionality.28 At Black Hat DC in 2006, John Heasman showed how to introduce malicious AML code into the ACPI description tables to facilitate deployment of a rootkit.29

The downside of subverting the description tables is that they’re visible to the operating system. This lends itself to cross-diff analysis, which can be used to detect foreign AML code. Also, as mentioned earlier, vendors can also use digital signature measures to prevent unsigned hardware-level updates. Finally, if an administrator is truly paranoid, he can simply disable ACPI in the BIOS setup or perhaps load an operating system that doesn’t leverage the technology (i.e., doesn’t have ACPI drivers).

Expansion ROM

Expansion ROM houses firmware that resides on peripheral hardware devices (e.g., video cards, networking cards, etc.). During the POST cycle, the BIOS walks through these devices, copying the contents of expansion ROM into memory and engaging the motherboard’s processor to execute the ROM’s initialization code. Expansion ROM can be sabotaged to conduct the same sort of attacks as normal BIOS ROM. For a graphic illustration of this, see John Heasman’s Black Hat DC 2007 talk on implementing a rootkit that targets the expansion ROM on PCI devices.30

Of the myriad devices that you can interface to the motherboard, the firmware that’s located in network cards is especially attractive as a rootkit garrison. There are a number of reasons for this:

Access to low-level covert channels.

Access to low-level covert channels.

A limited forensic footprint.

A limited forensic footprint.

Defense is problematic.

Defense is problematic.

A subverted network card can be programmed to capture and transmit packets without assistance (or intervention) of system-level drivers. In other words, you can create a covert channel against which software-level firewalls offer absolutely no defense. However, at the same time, I would strongly caution that anyone monitoring network traffic would see connections that aren’t visible locally at the machine’s console (and that can look suspicious).

A rootkit embedded in a network card’s firmware would also leave nothing on disk, unless, of course, it was acting as the first phase of a multistage loader. This engenders fairly decent concealment as firmware analysis has yet to make its way into the mainstream of forensic investigation. At the hardware level, the availability of tools and documentation varies too much.

Finally, an NIC-based rootkit is a powerful concept. I mean, assuming your machine is using a vulnerable network card, if your machine is merely connected to a network, then it has got a big “kick me” sign written on it. In my own travels, I’ve heard some attackers dismissively refer to firewalls as “speed bumps.” Perhaps this is a reason why. There’s some hardware-level flaw that we don’t know about …

To compound your already creeping sense of paranoia, there’s been a lot of research in this area. At Hack.Lu 2010, Guillaume Delugré presented a step-by-step guide for hacking the EEPROM firmware to Broadcom’s NetXtreme’s family of NICs.31 He discusses how to access the firmware, how to debug it, and how to modify it. This slide deck is a good launch pad.

At CanSecWest in March 2010, two different independent teams discussed ways of building an NIC-based rootkit. First up was Arrigo Triulzi, who developed a novel technique that has been called the “Jedi Packet Trick.”32 The technique is based on a remote diagnostic feature implemented in certain Broadcom cards (i.e., models BCM5751, BCM5752, BCM5753, BCM5754, BCM5755, BCM5756, BCM5764, and BCM5787). By sending a specially crafted packet to the NIC, Arrigo was able to install malicious firmware.

In addition to Triulzi’s work, Yves-Alexis Perez and Loïc Duflot from the French Network and Information Security Agency also presented their findings.33 They were able to exploit a bug in Broadcom’s remote administration functionality (which is based on an industry standard known as Alert Standard Format, or ASF) to run malicious code inside the targeted network controller and install a back door on a Linux machine.

UEFI Firmware

The Extensible Firmware Interface (EFI) specification was originally developed in the late 1990s by Intel to describe services traditionally implemented by the motherboard’s BIOS. The basic idea was to create the blueprints for a firmware-based platform that had more features and flexibility in an effort to augment the boot process for the next generation of Intel motherboards. In 2005, an industry group including Intel, AMD, IBM, HP, and Lenovo got together and co-opted EFI to create the Unified Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI).34

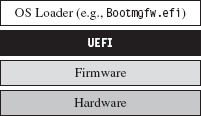

In a nutshell, UEFI defines a stand-alone platform that supports its own pre-OS drivers and applications. Think of UEFI as fleshing out the details of a miniature OS. This tiny OS exists solely to load a much larger one (e.g., Windows 7 or Linux) (see Figure 15.9). Just like any OS, the complexity of the UEFI execution environment is a double-edged sword. Sure, it provides lots of new bells and whistles, but in the wrong hands these features can morph into attack vectors. Like any operating system, a UEFI system can be undermined to host a rootkit.

Figure 15.9

There has been some publicly available work on hacking the UEFI. See, for example, John Heasman’s Black Hat USA 2007 presentation.35 Exactly a year later, at Black Hat USA 2008, Don Bailey and Martin Mocko gave a talk about leveraging the UEFI to load a rogue hypervisor during the pre-OS stage (in an effort to adhere to the basic tenet that it’s best to load deep and load first).36

15.3 Lights-Out Management Facilities

With the passage of time, the OEMs have been unable to resist the urge to put more and more functionality at the motherboard level. It’s gotten to the point where they’ve engineered fully functional stand-alone systems apart from the installed OS so that the machine can be accessed and managed without the customer even having to install an operating system (or even turn the darn thing on, hence the term lights-out).

Intel’s Active Management Technology (AMT) is a perfect example of this.37 It has its own independent processor to execute AMT code (which is stored in flash memory). It has its own plot of run-time memory, which is segregated from normal RAM via the AMT chipset. It also has a dedicated connection to networking hardware. Heck, the AMT chipset even supports a stand-alone web server! This is the mother of all maintenance shafts.

At Black Hat 2009, Rafal Wojtczuk and Alexander Tereshkin of Invisible Things Lab demonstrated how to bypass the chipset’s memory segregation and modify the code that the AMT executes38 while at the same time acquiring access to the memory space used by the installed operating system. Using this sort of attack, you could install a rootkit that wouldn’t require any interaction with the targeted OS, but at the same time you could manipulate the target and extract whatever information you needed without leaving a footprint. This explains why such tools have been called Ring –3 rootkits.

15.4 Less Obvious Alternatives

Finally, there are a couple of options that might not be readily apparent (well, at least not to me). These two tactics represent both ends of the rootkit spectrum. One is remarkably simple, and the other demands access to the crown jewels of the hi-tech industry.

Onboard Flash Storage

Certain OEMs often design their machines to support internal flash memory keys, presumably to serve as an alternate boot device, an encryption security key, or for mass storage. These keys can be refashioned into a malware safe house where you can deploy a rootkit. For example, on July 20, 2010, a user posted a query on Dell’s support forum after receiving a phone call from a Dell representative that made him suspicious.39 A couple of hours later, someone from Dell responded:

“The service phone call you received was in fact legitimate. As part of Dell’s quality process, we have identified a potential issue with our service mother board stock, like the one you received for your PowerEdge R410, and are taking preventative action with our customers accordingly. The potential issue involves a small number of PowerEdge server motherboards sent out through service dispatches that may contain malware. This malware code has been detected on the embedded server management firmware as you indicated.”

As Richard Bejtlich commented, “This story is making the news and Dell will update customers in a forum thread?!?”40

As it turns out, a worm (i.e., W32.Spybot) was discovered in flash storage on a small subset of replacement motherboards (not in the firmware). Dell never indicated how the malware found its way into the flash storage.

Circuit-Level Tomfoolery

Now we head into the guts of the processor core itself. As Rutkowska stated in this chapter’s opening quote, this may very well be the ultimate attack vector as far as rootkits are concerned. Given that, as of 2010, hardware vendors like Intel can pack as many as 2.9 billion transistors on a single chip, I imagine it wouldn’t be that difficult to embed a tiny snippet of logic that, given the right set of conditions, provides a covert back door to higher privilege levels.

There are approximately 1,550 companies involved with the design of integrated circuits (roughly 600 in Asia, 700 in North America, and 250 elsewhere).41 Couple this with the fact that 80 percent of all computer chips are manufactured outside the United States.42 Motive, opportunity, means; it’s all there.

How much effort do you suppose it would take for an intelligence service, industry competitor, or organized criminal group to plant/bribe someone with the necessary access to “inadvertently” introduce a “flaw” into a commodity processor? Once more, once this modification had been introduced, would it even be possible to detect? Do OEMs have the resources to trace through every possible combination of inputs that could trigger malicious logic? Although work has been done by researchers toward developing possible defenses against this sort of scenario (e.g., tamper-evident processors43), the current state of affairs on the ground doesn’t look very encouraging.

Huawei Technologies is the largest supplier of networking equipment in China. In 2009, the company became one of the world’s largest purveyors of global mobile network gear, second only to Ericsson.44 When asked about the likelihood of someone tampering with equipment sold by Huawei, Bruce Schneier (Chief Security Office at BT) stated that it “certainly wouldn’t surprise me at all.”45

Surely China isn’t alone as a potential suspect. Do you suppose that American vendors may have cooperated with our intelligence services to implement one or two cleverly disguised back channels in hardware?

My friends, welcome to the final frontier.

Though most rootkits tend to exist as software-based constructs, work has already been done toward identifying and targeting machines based solely on their processors. This could be seen as an initial move toward hardware-resident tools. For instance, at the First International Alternative Workshop on Aggressive Computing and Security in 2009, a group of researchers known as “The FED Team” presented work that identified a machine’s processor based on the nuances of how it evaluates complicated mathematical expressions.46

Once a targeted processor has been identified, perhaps one with a writable microcode store (like the Intel Xeon47), an attacker could upload a payload that hides out within the confines of the processor itself, making detection extremely problematic.

15.5 Conclusions

“SMM rootkits sound sexy, but, frankly, the bad guys are doing just fine using traditional kernel mode malware.”

—Joanna Rutkowska

In this chapter, we’ve focused on what is, without a doubt, the bleeding edge of rootkit technology. But is all of the extra work worth it? Once more, is hunkering down at the hardware level even a logistically sane option?

The answer to this question: It depends.

For example, if you’re focused on building stealth features into a botnet, then probably not. With botnets, portability is an issue. You want your payload to run on as many machines as possible, so you tend toward the least common denominator (e.g., software-enhanced concealment). The sad fact is that most users don’t even know to look at services.msc or to disable unnecessary browser add-ons, such that kernel-mode stealth is more than enough to do the job.

A FEW WORDS ON STUXNET

Despite the media frenzy surrounding Stuxnet, where journalists have described it as “hyper-sophisticated,”48 I believe that Stuxnet actually resides in the previous category. At least as far as anti-forensic tactics are concerned, I would assert that it’s using fairly dated technology.

For example, to map DLLs into memory, Stuxnet relies on a well-known hook-based approach that alters a handful of lower-level APIs used by the Kernel32.LoadLibrary() routine.49 This strategy generates forensic artifacts by virtue of the fact that a DLL loaded in this manner ends up in memory, and in the system’s run-time bookkeeping, but fails to show up on disk (a telltale sign, just ask the response team at Guidance Software). In other words, the absence of an artifact is itself an artifact.

A less conspicuous strategy is to use what’s been called reflective DLL injection, which is what contemporary suites like Metasploit use.50 Essentially, reflective DLL injection sidesteps the Windows loader entirely in favor of a custom user-mode loader (an idea that was presented years ago by researchers like The Grugq; e.g., data contraception).

Stuxnet also uses DLLs packed with UPX. Any anti-forensic developer worth his salt knows that UPX leaves a signature that’s easy for a trained investigator to recognize. A brief glance at the file headers is usually enough. Once recognized, unpacking is a cakewalk. Now, I would expect that if the engineers who built this software took the time and care to implement the obscure programming logic control (PLC) features that they did, they’d also have the resources and motivation to develop custom packing components. I mean, if you’re going to pack your code, at least make it difficult for the forensic guy wading through your payload. C’mon! It’s not that much work.

Why even use DLLs? Why not create some special-purpose file format that relies on a shrouded address table and utilizes an embedded virtual machine to execute one-of-a-kind bytecode? Really, if you have a real budget backing you up, why not go full bore? Heck, I know I would. Ahem.

Although Stuxnet does indeed manipulate hardware, it doesn’t take refuge in the hardware to conceal itself (as a truly hyper-sophisticated rootkit would). What all of this seems to indicate is that the people who built this in some respects took the path of least resistance. They opted to trade development effort for a forensic footprint. Is this the superweapon that the media is making Stuxnet out to be?

However, if you’re part of an organized group that has been formally tasked with a specific target, and you have the funding to develop (read bribe) an inside source to determine the chipsets involved, and the data you’re after is valuable enough, … .

We’ve seen what a lone gunman like Arrigo Triulzi can do with little or no funding and a ten-pack of cheap networking cards (hats off to you, Arrigo). Now take the subset of people that possesses the technical expertise to construct a MIRVed SLBM. To be honest, for these folks, implementing a hardware-level rootkit would probably be a rather pedestrian affair. Mix them together with the engineers who actually designed the processors being targeted, and you can create the sort of rootkit that keeps system administrators like me up at night.

1. http://www.intel.com/pressroom/kits/quickrefyr.htm.

2. http://cansecwest.com/slides06/csw06-duflot.ppt.

3. http://www.phrack.org/issues.html?issue=65&id=7#article.

4. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1460892.

5. http://cansecwest.com/csw09/csw09-duflot.pdf.

6. http://www.invisiblethingslab.com/resources/misc09/smm_cache_fun.pdf.

7. http://www.invisiblethingslab.com/resources/bh09usa/Attacking%20Intel%20BIOS.pdf.

8. http://blackhat.com/presentations/bh-usa-06/BH-US-06-Rutkowska.pdf.

9. http://www.eecs.umich.edu/virtual/papers/king06.pdf.

10. http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-usa-06/BH-US-06-Zovi.pdf.

11. http://securitywatch.eweek.com/showdown_at_the_blue_pill_corral.html.

12. http://invisiblethingslab.com/resources/bh08/part1.pdf.

13. http://discovery.csc.ncsu.edu/pubs/ccs09-HookSafe.pdf.

14. http://www.c7zero.info/stuff/bh-usa-08-bulygin.ppt.

15. http://invisiblethingslab.com/resources/bh08/part2-full.pdf.

16. http://people.csail.mit.edu/costan/readings/oakland_papers/hypersafe.pdf.

17. http://qubes-os.org/Home.html.

18. http://ertos.nicta.com.au/publications/papers/Klein_EHACDEEKNSTW_09.pdf.

19. http://www.nvlabs.in/uploads/projects/vbootkit/vbootkit_nitin_vipin_whitepaper.pdf.

20. http://www.stoned-vienna.com/downloads/Paper.pdf.

21. Darmawan Salihun, BIOS Disassembly Ninjutsu Uncovered, A-List Publishing, 2006.

22. http://www.coresecurity.com/files/attachments/Persistent_BIOS_Infection_CanSecWest09.pdf.

23. http://www.absolute.com/Shared/FAQs/CT-FAQ-TEC-E.sflb.ashx.

24. http://www.absolute.com/en/products/bios-compatibility.aspx.

25. http://www.coresecurity.com/content/Deactivate-the-Rootkit.

26. http://invisiblethingslab.com/resources/bh09usa/Attacking%20Intel%20BIOS.pdf.

27. http://www.acpi.info/DOWNLOADS/ACPIspec40a.pdf.

28. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa286523.aspx.

29. http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-federal-06/BH-Fed-06-Heasman.pdf.

30. http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-dc-07/Heasman/Paper/bh-dc-07-Heasman-WP.pdf.

31. http://esec-lab.sogeti.com/dotclear/public/publications/10-hack.lu-nicreverse_slides.pdf.

32. http://www.alchemistowl.org/arrigo/Papers/Arrigo-Triulzi-CANSEC10-Project-Maux-III.pdf.

33. http://www.ssi.gouv.fr/site_article185.html.

35. http://www.ngsconsulting.com/research/papers/BH-VEGAS-07-Heasman.pdf.

36. http://x86asm.net/articles/uefi-hypervisors-winning-the-race-to-bare-metal/.

37. http://www.intel.com/technology/platform-technology/intel-amt/.

38. http://invisiblethingslab.com/resources/bh09usa/Ring%20-3%20Rootkits.pdf.

39. http://en.community.dell.com/support-forums/servers/f/956/t/19339458.aspx.

40. http://taosecurity.blogspot.com/2010/07/dell-needs-psirt.html.

41. John Villasenor, “The Hacker in Your Hardware,” Scientific American, August 2010, p. 82.

42. John Markoff, “Old Trick Threatens the Newest Weapons,” New York Times, October 27, 2009.

43. http://www.cs.columbia.edu/~simha/cal/pubs/pdfs/TEMP_Oakland10.pdf.

44. http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSLD56804020091113.

45. Alan Reiter, “Huawei’s US Sales Push Raises Security Concerns,” Internet Evolution, September 10, 2010.

46. http://www.esiea-recherche.eu/iawacs_2009_papers.html.

47. http://support.microsoft.com/kb/936357.

48. Mark Clayton, “Stuxnet malware is ‘weapon’ out to destroy … Iran’s Bushehr nuclear plant?” Christian Science Monitor, September 21, 2010.

49. http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/w32stuxnet-installation-details.

50. http://www.harmonysecurity.com/files/HS-P005_ReflectiveDllInjection.pdf.