Chapter 6 Life in Kernel Space

Based on feedback that I’ve received from readers, one of the misconceptions that I unintentionally fostered in the first edition of this book was that a kernel-mode driver (KMD) was the same thing as a rootkit. Although a rootkit may include code that somehow gets loaded into kernel space, it doesn’t have to. For normal system engineers, a KMD is just the official channel to gain access to hardware. For people like you and me, it also offers a well-defined entryway into the guts of the operating system. Ultimately, this is useful because it puts you on equal footing with security software, which often loads code into kernel space to assail malware from within the fortified walls of Ring 0.

Using a KMD is system-level coding with training wheels. It gives you a prefabricated environment that has a lot of support services available. In a more austere setting, you may be required to inject code directly into kernel space, outside of the official channels, without having the niceties afforded to a driver. Thus, KMD development will allow us to become more familiar with the eccentricities of kernel space in a stable and well-documented setting. Once you’ve mastered KMDs, you can move on to more sophisticated techniques, like using kernel-mode shellcode.

Think of it this way. If the operating system’s executive was a heavily guarded fortress in the Middle Ages, using a KMD would be like getting past the sentries by disguising yourself as a local merchant and walking through the main gate. Alternatively, you could also use a grappling hook to creep in through a poorly guarded window after nightfall; though in this case you wouldn’t have any of the amenities of the merchant.

Because the KMD is Microsoft’s sanctioned technique for introducing code into kernel space, building KMDs is a good way to become familiar with the alternate reality that exists there. The build tools, APIs, and basic conventions that you run into differ significantly from those of user mode. In this chapter, I’ll show you how to create a KMD, how to load a KMD into memory, how to contend with kernel-mode security measures, and also touch upon related issues like synchronization.

6.1 A KMD Template

By virtue of their purpose, rootkits tend to be small programs. They’re geared toward leaving a minimal system footprint (both on disk and in memory). In light of this, their source trees and build scripts tend to be relatively simple. What makes building rootkits a challenge is the process of becoming acclimated to life in kernel space. Specifically, I’m talking about implementing kernel-mode drivers.

At first blush, the bare metal details of the IA-32 platform (with its myriad of bit-field structures) may seem a bit complicated. The truth is, however, that the system-level structures used by the Intel processor are relatively simple compared with the inner workings of the Windows operating system, which piles layer upon layer of complexity over the hardware. This is one reason why engineers fluent in KMD implementation are a rare breed compared with their user-mode brethren.

Though there are other ways to inject code into kernel space (as you’ll see), kernel-mode drivers are the approach that comes with the most infrastructure support, making rootkits that use them easier to develop and manage. Just be warned that you’re sacrificing stealth for complexity. In this section, I’ll develop a minimal kernel-mode driver that will serve as a template for later KMDs.

Kernel-Mode Drivers: The Big Picture

A kernel-mode driver is a loadable kernel-mode module that is intended to act as a liaison between a hardware device and the operating system’s I/O manager (though some KMDs also interact with the Plug-and-Play manager and the Power manager). To help differentiate them from ordinary binaries, KMDs typically have their file names suffixed by the .SYS extension.

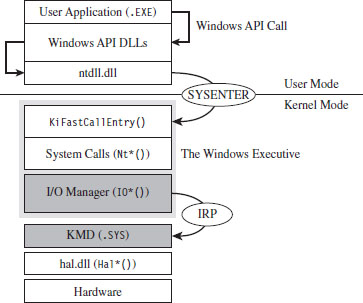

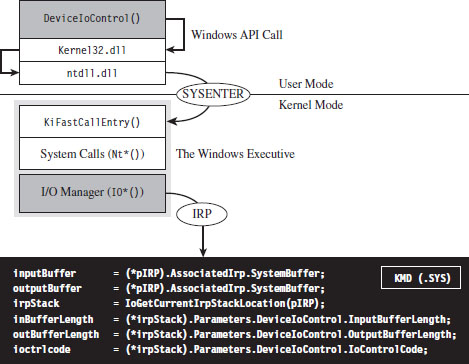

Once it’s loaded into kernel space, there’s nothing to keep a KMD from talking to hardware directly. Nevertheless, a well-behaved KMD will try to follow standard etiquette and use routines exported by the HAL to interface with hardware (imagine going to a party and ignoring the host; it’s just bad manners). On the other side of the interface layer cake (see Figure 6.1), the KMD talks with the I/O manager by receiving and processing chunks of data called I/O request packets (IRPs). IRPs are usually created by the I/O manager on behalf of some user-mode applications that want to communicate with the device via a Windows API call.

Figure 6.1

To feed information to the driver, the I/O manager passes the address of an IRP to the KMD. This address is realized as an argument to a dispatch routine exported by the KMD. The KMD routine will digest the IRP, perform a series of actions, and then return program control back to the I/O manager. There can be instances where the I/O manager ends up routing an IRP through several related KMDs (referred to as a driver stack). Ultimately, one of the exported driver routines in the driver stack will complete the IRP, at which point the I/O manager will dispose of the IRP and report the final status of the original call back to the user-mode program that initiated the request.

The previous discussion may seem a bit foreign (or perhaps vague). This is a normal response; don’t let it discourage you. The details will solidify as we progress. For the time being, all you need to know is that an IRP is a blob of memory used to ferry data to and from a KMD. Don’t worry about how this happens.

From a programmatic standpoint, an IRP is just a structure written in C that has a bunch of fields. I’ll introduce the salient structure members as needed. If you want a closer look to satisfy your curiosity, you can find the IRP structure’s blueprints in wdm.h. The official Microsoft documentation refers to the IRP structure as being “partially opaque” (partially undocumented).

The I/O manager allocates storage for the IRP, and then a pointer to this structure gets thrown around to everyone and their uncle until the IRP is completed. From 10,000 feet, the existence of a KMD centers on IRPs. In fact, to a certain extent a KMD can be viewed as a set of routines whose sole purpose is to accept and process IRPs.

In the spectrum of possible KMDs, our driver code will be relatively straightforward. This is because our needs are modest. The KMDs that we create exist primarily to access the internal operating system code and data structures. The IRPs that they receive will serve to pass commands and data between the user-mode and kernel-mode components of our rootkit.

WDK Frameworks

Introducing new code into kernel space has always been somewhat of a mysterious art. To ease the transition to kernel mode, Microsoft has introduced device driver frameworks. For example, the Windows Driver Model (WDM) was originally released to support the development of drivers on Windows 98 and Windows 2000. In the years that followed, Microsoft came out with the Windows Driver Framework (WDF), which encapsulated the subtleties of WDM with another layer of abstraction. The relationship between the WDM and WDF frameworks is similar to the relationship between COM and COM+, or between the Win32 API and the MFC. To help manage the complexity of a given development technology, Microsoft wraps it up with objects until it looks like a new one. In this book, I’m going to stick to the older WDM.

A Truly Minimal KMD

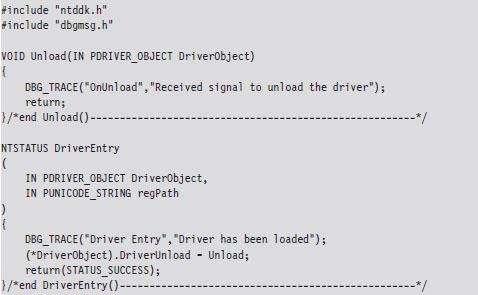

The following snippet of code represents a truly minimal KMD. Don’t panic if you feel disoriented; I’ll step you through this code one line at a time.

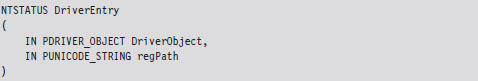

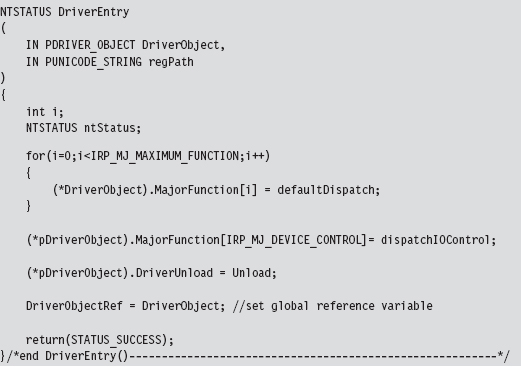

The DriverEntry() routine is executed when the KMD is first loaded into kernel space. It’s analogous to the main() or WinMain() routine defined in a user-mode application. The DriverEntry() routine returns a 32-bit integer value of type NTSTATUS.

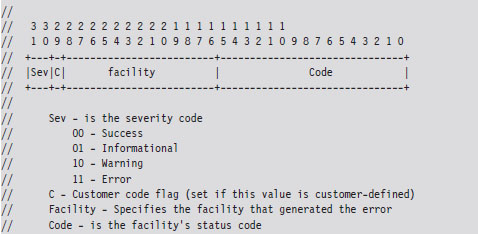

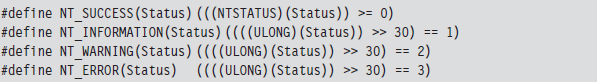

The two highest-order bits of this value define a severity code that offers a general indication of the routine’s final outcome. The layout of the other bits is given in the WDK’s ntdef.h header file.

The following macros, also defined in ntdef.h, can be used to test for a specific severity code.

Now let’s move on to the parameters of DriverEntry().

For those members of the audience who aren’t familiar with Windows API conventions, the IN attribute indicates that these are input parameters (as opposed to parameters qualified by the OUT attribute, which indicates that they return values to the caller). Another thing that might puzzle you is the “P” prefix, which indicates a pointer data type.

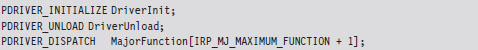

The DRIVER_OBJECT parameter represents the memory image of the KMD. It’s another one of those “partially opaque” structures (see wdm.h in the WDK). It stores metadata that describes the KMD and other fields used internally by the I/O manager. From our standpoint, the most important aspect of the DRIVER_OBJECT is that it stores the following set of function pointers.

By default, the I/O manager sets the DriverInit pointer to store the address of the DriverEntry() routine when it loads the driver. The DriverUnload pointer can be set by the KMD. It stores the address of a routine that will be called when the KMD is unloaded from memory. This routine is a good place to tie up loose ends, close file handles, and generally clean up before the driver terminates. The MajorFunction array is essentially a call table. It stores the addresses of routines that receive and process IRPs (see Figure 6.2).

The regPath parameter is just a Unicode string describing the path to the KMD’s key in the registry. As is the case for Windows services (e.g., Windows Event Log, Remote Procedure Call, etc.), drivers typically leave an artifact in the registry that specifies how they can be loaded and where the driver executable is located. If your driver is part of a rootkit, this is not a good thing because it translates into forensic evidence.

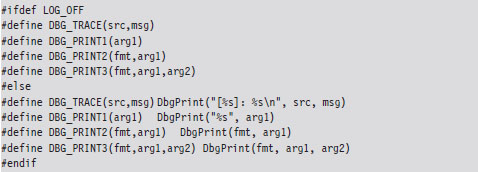

The body of the DriverEntry() routine is pretty simple. I initialize the DriverUnload function pointer and then return STATUS_SUCCESS. I’ve also included a bit of tracing code. Throughout this book, you’ll see it sprinkled in my code. This tracing code is a poor man’s troubleshooting tool that uses macros defined in the rootkit skeleton’s dbgmsg.h header file.

Figure 6.2

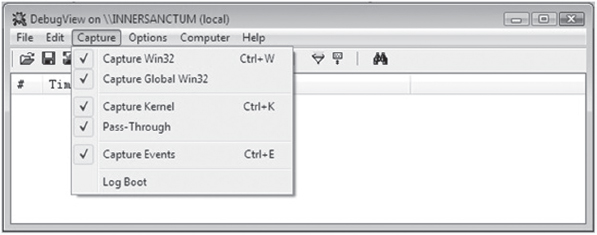

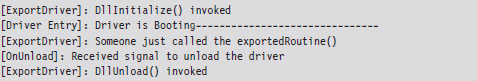

These macros use the WDK’s DbgPrint() function, which is the kernel-mode equivalent of printf(). The DbgPrint() function streams output to the console during a debugging session. If you’d like to see these messages without having to go through the hassle of cranking up a kernel-mode debugger like KD.exe, you can use a tool from Sysinternals named Dbgview.exe. To view DbgPrint() messages with Dbgview.exe, make sure that the Capture Kernel menu item is checked under the Capture menu (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3

One problem with tracing code like this is that it leaves strings embedded in the binary. In an effort to minimize the amount of forensic evidence in a production build, you can set the LOG_OFF macro at compile time to disable tracing.

Handling IRPs

The KMD we just implemented doesn’t really do anything other than display a couple of messages on the debugger console. To communicate with the outside, our KMD driver needs to be able to accept IRPs from the I/O manager. To do this, we’ll need to populate the MajorFunction call table we met earlier. These are the routines that the I/O manager will pass its IRP pointers to.

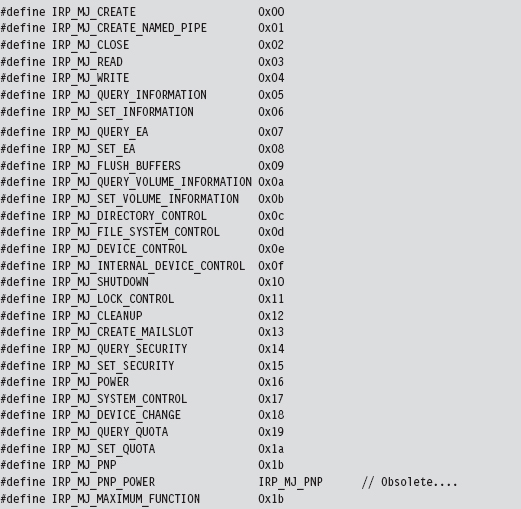

Each IRP that the I/O manager passes down is assigned a major function code of the form IRP_MJ_XXX. These codes tell the driver what sort of operation it should perform to satisfy the I/O request. The list of all possible major function codes is defined in the WDK’s wdm.h header file.

The three most common types of IRPs are

IRP_MJ_READ

IRP_MJ_READ

IRP_MJ_WRITE

IRP_MJ_WRITE

IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL

IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL

Read requests pass a buffer to the KMD (via the IRP), which is to be filled with data from the device. Write requests pass data to the KMD, which is to be written to the device. Device control requests are used to communicate with the driver for some arbitrary purpose (as long as it isn’t for reading or writing). Because our KMD isn’t associated with a particular piece of hardware, we’re interested in device control requests. As it turns out, this is how the user-mode component of our rootkit will communicate with the kernel-mode component.

The MajorFunction array has an entry for each IRP major function code. Thus, if you so desired, you could construct a different function for each type of IRP. But, as I just mentioned, we’re only truly interested in IRPs that correspond to device control requests. Thus, we’ll start by initializing the entire MajorFunction call table (from IRP_MJ_CREATE to IRP_MJ_MAXIMUM_FUNCTI0N) to the same default routine and then overwrite the one special array element that corresponds to device control requests. This should all be done in the Driver-Entry() routine, which underscores one of the primary roles of the function.

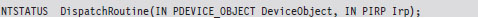

The functions referenced by the MajorFunction array are known as dispatch routines. Though you can name them whatever you like, they must all possess the following type of signature:

The default dispatch routine defined below doesn’t do much. It sets the information field of the IRP’s IoStatus member to the number of bytes successfully transferred (i.e., 0) and then “completes” the IRP so that the I/O manager can dispose of the IRP and report back to the application that initiated the whole process (ostensibly with a STATUS_SUCCESS message).

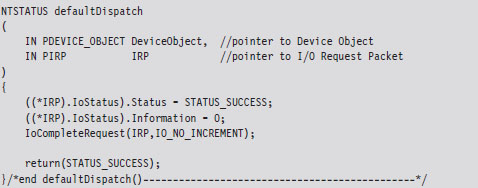

Whereas the defaultDispatch() routine is, more or less, a placeholder of sorts, the dispatchIOControl() function accepts specific commands from user mode. As you can see from the following code snippet, information can be sent or received through buffers. These buffers are referenced by void pointers for the sake of flexibility, allowing us to pass almost anything that we can cast. This is the primary tool we will use to facilitate communication with user-mode code.

The secret to knowing what’s in the buffers, and how to treat this data, is the associated I/O control code (also known as an IOCTL code). An I/O control code is a 32-bit integer value that consists of a number of smaller subfields. As you’ll see, the I/O control code is passed down from the user application when it interacts with the KMD. The KMD extracts the IOCTL code from the IRP and then stores it in the ioctrlcode variable. Typically, this integer value is fed to a switch statement. Based on its value, program-specific actions can be taken.

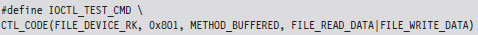

In the previous dispatch routine, IOCTL_TEST_CMD is a constant computed via a macro:

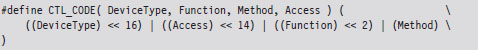

This rather elaborate custom macro represents a specific I/O control code. It uses the system-supplied CTL_CODE macro, which is declared in wdm.h and is used to define new IOCTL codes.

You may be looking at this macro and scratching your head. This is understandable; there’s a lot going on here. Let’s move through the top line in slow motion and look at each parameter individually.

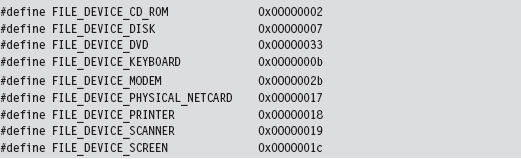

DeviceType The device type represents the type of underlying hardware for the driver. The following is a sample list of predefined device types:

For an exhaustive list, see the ntddk.h header file that ships with the WDK. In general, Microsoft reserves device type values 0x0000 - 0x7FFF (0 through 32,767).

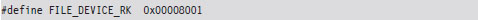

Developers can define their own values in the range 0x8000 - 0xFFFF (32,768 through 65,535). In our case, we’re specifying a vendor-defined value for a new type of device:

Function The function parameter is a program-specific integer value that defines what action is to be performed. Function codes in the range 0x0000- 0x07FF (0 through 2,047) are reserved for Microsoft Corporation. Function codes in the range 0x0800 - 0x0FFF (2,048 through 4,095) can be used by customers. In the case of our sample KMD, we’ve chosen 0x0801 to represent a test command from user mode.

Method This parameter defines how data will pass between user-mode and kernel-mode code. We chose to specify the METHOD_BUFFERED value, which indicates that the OS will create a non-paged system buffer, equal in size to the application’s buffer.

Access The access parameter describes the type of access that a caller must request when opening the file object that represents the device. FILE_READ_DATA allows the KMD to transfer data from its device to system memory. FILE_WRITE_DATA allows the KMD to transfer data from system memory to its device. We’ve logically OR-ed these values so that both access levels hold simultaneously.

Communicating with User-Mode Code

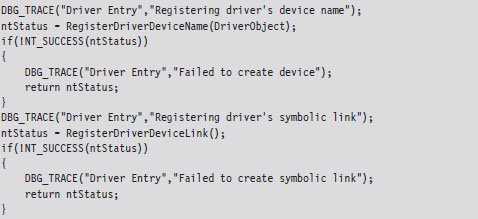

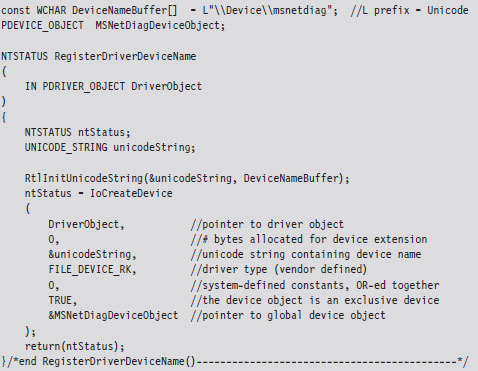

Now that our skeletal KMD can handle the necessary IRPs, we can write user-mode code that communicates with the KMD. To facilitate this, the KMD must advertise its presence. It does this by creating a temporary device object, for use by the driver, and then establishing a user-visible name (i.e., a symbolic link) that refers to this device. These steps are implemented by the following code.

This code can be copied into the KMD’s DriverEntry() routine. The first function call creates a device object and uses a global variable (i.e., MSNetDiagDeviceObject) to store a reference to this object.

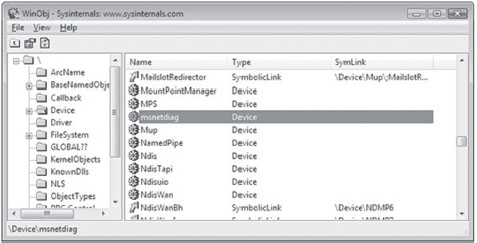

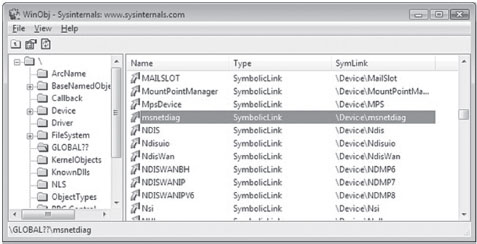

The name of this newly minted object, \Device\msnetdiag, is registered with the operating system using the Unicode string that was derived from the global DeviceNameBuffer array. Most of the hard work is done by the I/O manager via the IoCreateDevice() call. You can verify that this object has been created for yourself by using the WinObj.exe tool from Sysinternals (see Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4

In Windows, the operating system uses an object model to manage system constructs. What I mean by this is easy to misinterpret, so read the following carefully: Many of the structures that populate kernel space can be abstracted to the extent that they can be manipulated using a common set of routines (i.e., as if each structure were derived from a base Object class). Clearly, most of the core Windows OS is written in C, a structured programming language. So I’m NOT referring to programmatic objects like you’d see in Java or C++. Rather, the executive is organizing and treating certain internal structures in a manner that is consistent with the object-oriented paradigm. The WinObj.exe tool allows you to view the namespace maintained by the executive’s Object manager. In this case, we’ll see that \Device\msnetdiag is the name of an object of type Device.

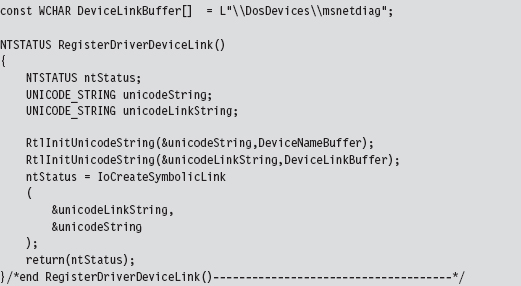

Once we’ve created a device object via a call to RegisterDriverDeviceName(), we can create, and link, a user-visible name to the device with the next function call.

As before, we can use WinObj.exe to verify that an object named msnetdiag has been created under the \GLOBAL?? node. WinObj.exe shows that this object is a symbolic link and references the \Device\msnetdiag object (see Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5

The name that you assign to the driver device and the symbolic link are completely arbitrary. However, I like to use names that sound legitimate (e.g., msnetdiag) to help obfuscate the fact that what I’m registering is part of a rootkit. From my own experience, certain system administrators are loath to delete anything that contains acronyms like “OLE,” “COM,” or “RPC.” Another approach is to use names that differ only slightly from those used by genuine drivers. For inspiration, use the drivers.exe tool that ships with the WDK to view a list of potential candidates.

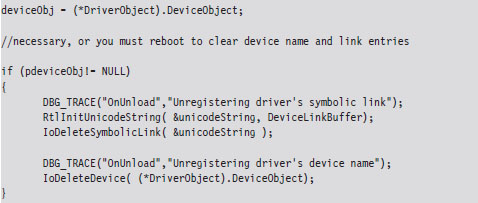

Both the driver device and the symbolic link you create exist only in memory. They will not survive a reboot. You’ll also need to remember to unregister them when the KMD unloads. This can be done by including the following few lines of code in the driver’s Unload() routine:

Note: Besides just offering a standard way of accessing resources, the Object manager and its naming scheme were originally put in place for the sake of supporting the Windows POSIX subsystem. One of the basic precepts of the UNIX world is that “everything is a file.” In other words, all hardware peripherals and certain system resources can be manipulated programmatically as files. These special files are known as device files, and they reside in the /dev directory on a standard UNIX install. For example, the /dev/kmem device file provides access to the virtual address space of the operating system (excluding memory associated with I/O peripherals).

Sending Commands from User Mode

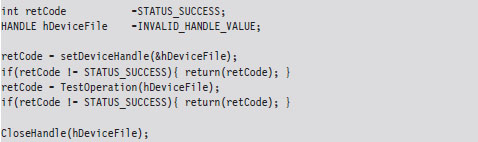

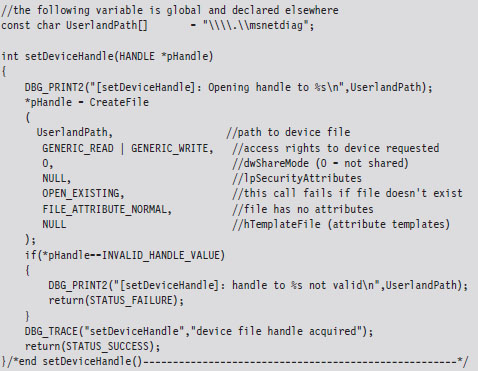

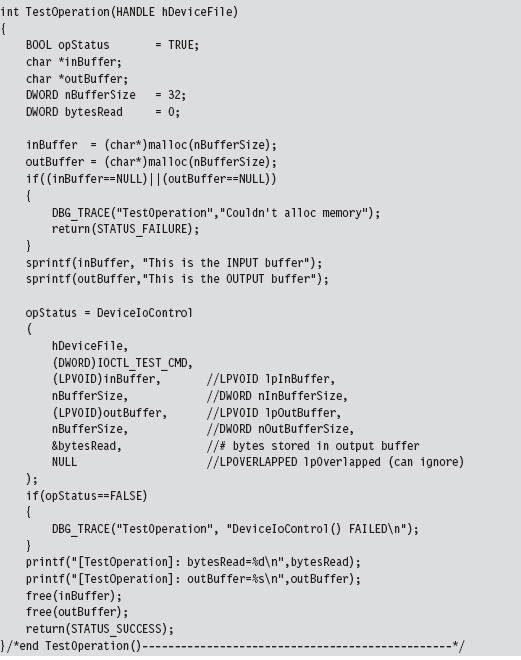

We’ve done everything that we’ve needed to receive and process a simple test command with our KMD. All that we need to do now is to fire off a request from a user-mode program. The following statements perform this task.

Let’s drill down into the function calls that this code makes. The first thing this code does is to access the symbolic device link established by the KMD. Then, it uses this link to open a handle to the KMD’s device object.

If a handle to the msnetdiag device is successfully acquired, the user-mode code invokes a standard Windows API routine (i.e., DeviceIoControl()) that sends the I/O control code that we defined earlier.

The user-mode application will send information to the KMD via an input buffer, which will be embedded in the IRP that the KMD receives. What the KMD actually does with this buffer depends upon how the KMD was designed to respond to the I/O control code. If the KMD wishes to return information back to the user-mode code, it will populate the output buffer (which is also embedded in the IRP).

To summarize roughly what happens: the user-mode application allocates buffers for both input and output. Then, it calls the DeviceIoControl() routine, feeding it the buffers and specifying an I/O control code. The I/O control code value will determine what the KMD does with the input buffer and what it returns in the output buffer.

The arguments to DeviceIoControl() migrate across the border into kernel mode where the I/O manager repackages them into an IRP structure. The IRP is then passed to the dispatch routine in the KMD that handles the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL major function code. The dispatch routine then inspects the I/O control code and takes whatever actions have been prescribed by the developer who wrote the routine (see Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6

6.2 Loading a KMD

You’ve seen how to implement and build a KMD. The next step in this natural progression is to examine different ways to load the KMD into memory and manage its execution. There are a number of different ways that people have found to do this, ranging from officially documented to out-and-out risky.

In the sections that follow, I will explore techniques to load a KMD and comment on their relative trade-offs:

The Service Control manager.

The Service Control manager.

Using export drivers.

Using export drivers.

Leveraging an exploit in the kernel.

Leveraging an exploit in the kernel.

Strictly speaking, the last method listed is aimed at injecting arbitrary code into Ring 0, not just loading a KMD. Drivers merely offer the most formal approach to accessing the internals of the operating system and are thus the best tool to start with.

Note: There are several techniques for loading code into kernel space that are outdated. For example, in August 2000, Greg Hoglund posted code on NTBUGTRAQ that demonstrated how to load a KMD using an undocumented system call named ZwSetSystemInformation(). There are also other techniques that Microsoft has countered by limiting user-mode privileges, like writing directly to \Device\PhysicalMemory or modifying driver code that has been paged to disk. Whereas I covered these topics in the first edition of this book, for the sake of brevity I’ve decided not to do so in this edition.

6.3 The Service Control Manager

This is the “Old Faithful” of driver loading. By far, the Service Control Manager (SCM) offers the most stable and sophisticated interface. This is the primary reason why I use the SCM to manage KMDs during the development phase. If a bug does crop up, I can rest assured that it’s probably not a result of the code that loads the driver. Initially relying on the SCM helps to narrow down the source of problems.

The downside to using the SCM is that it leaves a significant amount of forensic evidence in the registry. Whereas a rootkit can take measures to hide these artifacts at runtime, an offline disk analysis is another story. In this case, the best you can hope for is to obfuscate your KMD and pray that the system administrator doesn’t recognize it for what it really is. This is one reason why you should store your driver files in the standard folder (i.e., %windir%\system32\drivers). Anything else will arouse suspicion during an offline check.

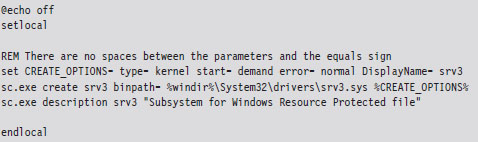

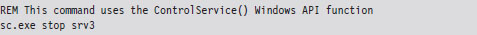

Using sc.exe at the Command Line

The built-in sc.exe command is the tool of choice for manipulating drivers from the command line. Under the hood, it interfaces with the SCM programmatically via the Windows API to perform driver management operations.

Before the SCM can load a driver into memory, an entry for the driver must be entered into the SCM’s database. You can register this sort of entry using the following script.

The sc.exe create command corresponds to the CreateService() Windows API function. The second command, which defines the driver’s description, is an attempt to obfuscate the driver in the event that it’s discovered.

Table 6.1 lists and describes the command-line parameters used with the create command.

Table 6.1 Create Command Arguments

| Parameter | Description |

| binpath | Common header files |

| type | Kernel-mode driver source code and build scripts |

| start | Binary deliverable (.SYS file) |

| error | Object code output, fed to WDK linker |

| DisplayName | User-mode source code, build scripts, and binaries |

The start parameter can assume a number of different values (see Table 6.2). During development, demand is probably your best bet. For a production KMD, I would recommend using the auto value.

Table 6.2 Start Command Arguments

| Parameter | Description |

| boot | Loaded by the system boot loader (winload.exe) |

| system | Loaded by ntoskrnl.exe during kernel initialization |

| auto | Loaded by the System Control manager (services.exe) |

| demand | Driver must be manually loaded |

| disabled | This driver cannot be loaded |

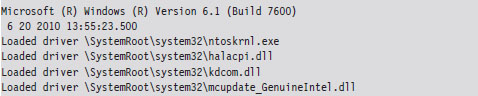

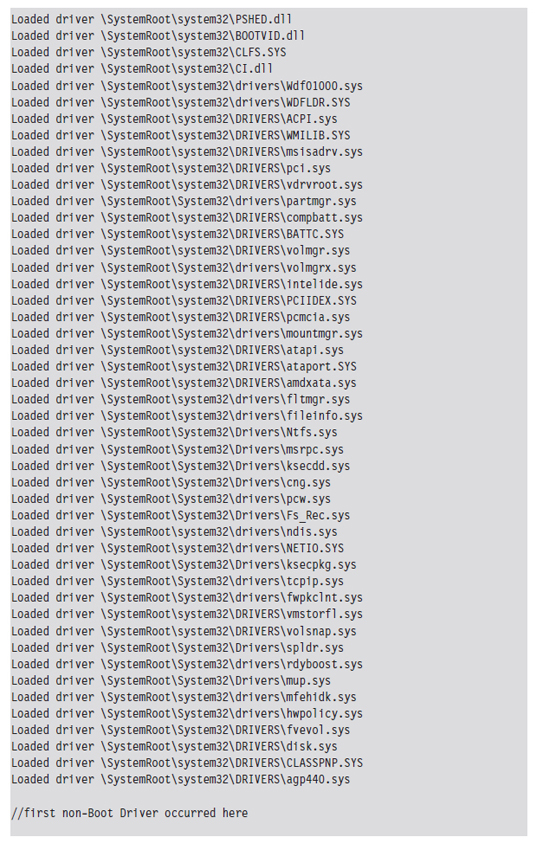

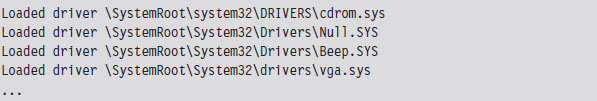

The first three entries in Table 6.2 (e.g., boot class drivers, system class drivers, and auto class drivers) are all loaded automatically. As explained in Chapter 4, what distinguishes them is the order in which they’re introduced into memory. Boot class drivers are loaded early on by the system boot loader (winload.exe). System class drivers are loaded next, when the Windows executive (ntoskrnl.exe) is initializing itself. Auto-start drivers are loaded near the end of system startup by the SCM (services.exe).

During development, you’ll want to set the error parameter to normal (causing a message box to be displayed if a driver cannot be loaded). In a production environment, where you don’t want to get anyone’s attention, you can set error to ignore.

Once the driver has been registered with the SCM, loading it is a simple affair.

To unload the driver, invoke the sc.exe stop command.

If you want to delete the KMD’s entry in the SCM database, use the delete command. Just make sure that the driver has been unloaded before you try to do so.

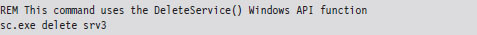

Using the SCM Programmatically

While the command-line approach is fine during development, because it allows driver manipulation to occur outside of the build cycle, a rootkit in the wild will need to manage its own KMDs. To this end, there are a number of Windows API calls that can be invoked. Specifically, I’m referring to service functions documented in the SDK (e.g., CreateService(), StartService(), ControlService(), DeleteService(), etc.).

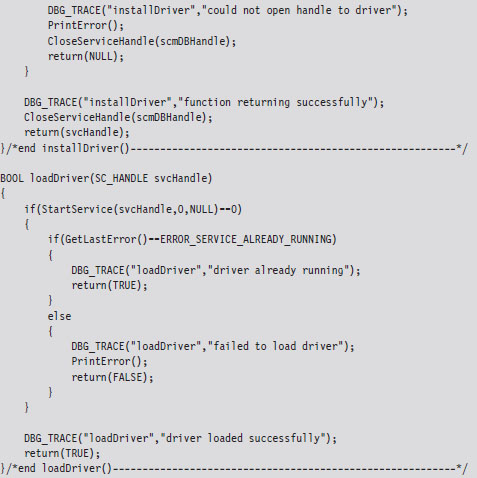

The following code snippet includes routines for installing and loading a KMD using the Windows Service API.

Registry Footprint

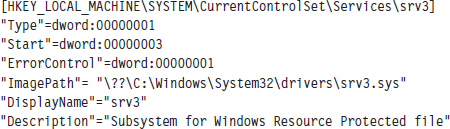

When a KMD is registered with the SCM, one of the unfortunate by-products is a conspicuous footprint in the registry. For example, the skeletal KMD we looked at earlier is registered as a driver named “srv3.” This KMD will have an entry in the SYSTEM registry hive under the following key:

HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\srv3

We can export the contents of this key to see what the SCM stuck there:

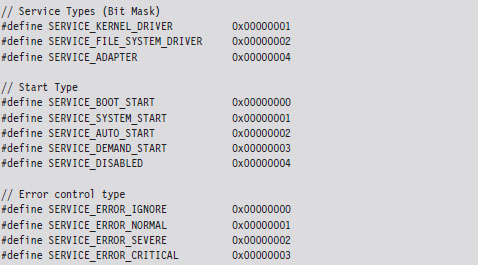

You can use macros defined in WinNT.h to map the hex values in the registry dump to parameter values and verify that your KMD was installed correctly.

6.4 Using an Export Driver

The registry footprint that the SCM generates is bad news because any forensic investigator worth his or her salt will eventually find it. One way to load driver code without leaving telltale artifacts in the registry is to use an export driver.

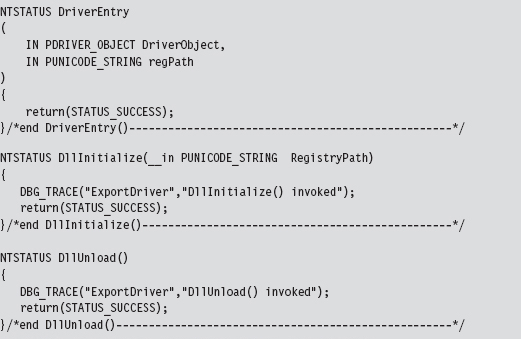

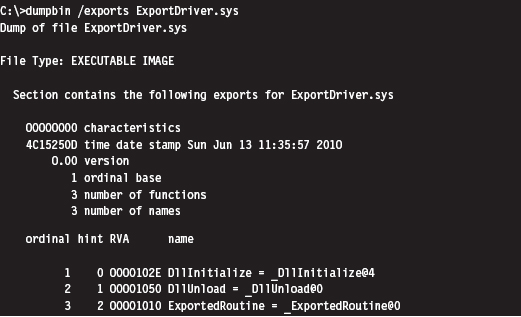

In a nutshell, an export driver is the kernel-mode equivalent of a DLL. It doesn’t require an entry in the SCM’s service database (hence no registry entry). It also doesn’t implement a dispatch table, so it cannot handle IRPs. A bare-bones export driver need only implement three routines: DriverEntry(), DllInitialize(), and DllUnload().

The DriverEntry() routine is just a stub whose sole purpose is to appease the WDK’s build scripts. The other two routines are called to perform any housekeeping that may need to be done when the export driver is loaded and then unloaded from memory.

Windows maintains an internal counter for each export driver. This internal counter tracks the number of other drivers that are importing routines from an export driver. When this counter hits zero, the export driver is unloaded from memory.

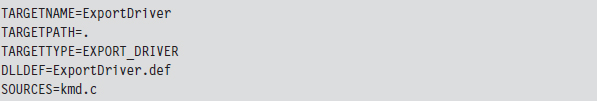

Building an export driver requires a slightly modified SOURCES file.

Notice how the TARGETTYPE macro has been set to EXPORT_DRIVER. We’ve also introduced the DLLDEF macro to specify the location of an export definition file. This file lists the routines that the export file will make available to the outside world.

The benefit of using this file is that it saves us from dressing up the export driver’s routines with elaborate storage-class declarations (e.g., __ declspec(dllexport)). The keyword PRIVATE that appears after the first two routines in the EXPORTS section of the export definition file tells the linker to export the DllInitialize and DllUnload symbols from the export driver, but not to include them in the import library file (e.g., the .LIB file) that it builds. The build process for an export driver generates two files:

ExportDriver.lib

ExportDriver.lib

ExportDriver.sys

ExportDriver.sys

The .LIB file is the import library that I just mentioned. Drivers that invoke routines from our export driver will need to include this file as a part of their build cycle. They will also need to add the following directive in their SOURCES file.

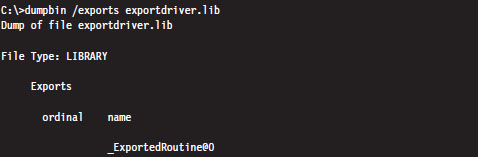

Using dumpbin.exe, you can see that the PRIVATE export directives had the desired effect. The DllInitialize and DllUnload symbols have not been exported.

The .SYS file is the export driver proper, our kernel-mode dynamically linked library (even though it doesn’t end with the .DLL extension). This file will need to be copied to the %windir%\system32\drivers\ directory in order to be accessible to other drivers.

You can use the dumpbin.exe command to see the routines that are exported.

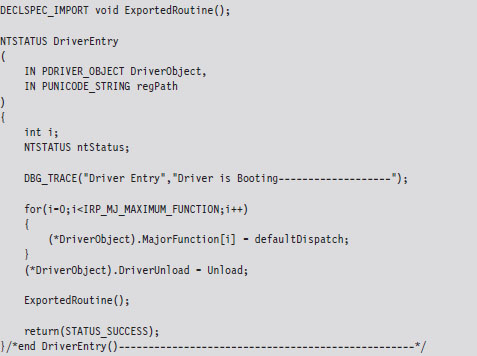

The driver that invokes routines from an export driver must declare them with the DECLSPEC_IMPORT macro. Once this step has been taken, an export driver routine can be called like any other routine.

The output of this code will look something like:

As mentioned earlier, the operating system will keep track of when to load and unload the driver. From our standpoint, this is less than optimal because it would be nice if we could just stick an export driver in %windir%\system32\ drivers\ and then have it automatically load without the assistance of yet another driver.

6.5 Leveraging an Exploit in the Kernel

Although export drivers have a cleaner registry profile, they still suffer from two critical shortcomings. Specifically:

Export drivers must persist in %WinDir%\system32\drivers.

Export drivers must persist in %WinDir%\system32\drivers.

Export driver code must be called from within another KMD.

Export driver code must be called from within another KMD.

So, even though export drivers don’t leave a calling card in the registry, they still leave an obvious footprint on the file system, not to mention that invoking the routines in an exported driver requires us to load a KMD of our own, which forces us to touch the registry (thus negating the benefits afforded by the export driver).

These complications leave us looking for a more stealthy way to load code into kernel space.

If you’re a connoisseur of stack overflows, shellcode, and the like, yet another way to inject code into the kernel is to use flaws in the operating system itself. Given the sheer size of the Windows code base, and the Native API interface, statistically speaking the odds are that at least a handful of zero-day exploits will always exist. It’s bug conservation in action. This also may lead one to ponder whether back doors have been intentionally introduced and concealed as bugs. I wonder how hard it would be for a foreign intelligence agency to plant a mole inside a vendor’s development teams?

Even if Windows, as a whole, were free of defects, an attacker could always shift their attention away from Windows and instead focus on bugs in existing third-party kernel-mode drivers. It’s the nature of the beast. People seem to value new features more than security.

The trade-offs inherent to this tactic are extreme. Whereas using exploits to drop a rootkit in kernel space offers the least amount of stability and infrastructure, it also offers the lowest profile. With greater risk comes greater reward.

But don’t take my word for it. Listen to the professionals. As Joanna Rutkowska has explained:

“There are hundreds of drivers out there, usually by 3rd party firms, and it is *easy* to find bugs in those drivers. And Microsoft cannot do much about it.

This is and will be the ultimate way to load any rootkit on any Windows system, until Microsoft switches to some sort of micro-kernel architecture, or will not isolate drivers in some other way (e.g., ALA Xen driver domains).

This is the most generic attack today.”

6.6 Windows Kernel-Mode Security

Now that we have a basic understanding of how to introduce code into the kernel, we can look at various measures Microsoft has included in Windows to make this process difficult for us. In particular, I’m going to look at the following security features:

Kernel-mode code signing.

Kernel-mode code signing.

Kernel patch protection.

Kernel patch protection.

Kernel-Mode Code Signing (KMCS)

On the 64-bit release of Windows, Microsoft requires KMDs to be digitally signed with a Software Publishing Certificate (SPC) in order to be loaded into memory. Although this is not the case for 32-bit Windows, all versions of Windows require that the small subset of core system binaries and all of the boot drivers be signed. The gory details are spelled out by Microsoft in a document known as the KMCS Walkthrough, which is available online.1

Boot drivers are those drivers loaded early on by Winload.exe. In the registry, they have a start field that looks like:

This corresponds to the SERVICE_BOOT_START macro defined in WinNT.h.

You can obtain a list of core system binaries and boot drivers by enabling boot logging and then cross-referencing the boot log against what’s listed in HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services. The files are listed according to their load order during startup, so all you really have to do is find the first entry that isn’t a boot driver.

If any of the boot drivers fail their initial signature check, Windows will refuse to start up. This hints at just how important boot drivers are and how vital it is to get your rootkit code running as soon as possible.

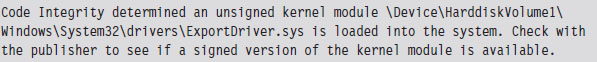

Under the hood, Winload.exe implements the driver signing checks for boot drivers.2 On the 64-bit version of Windows, ntoskrnl.exe uses routines exported from CI.DLL to take care of checking signatures for all of the other drivers.3 Events related to loading signed drivers are archived in the Code Integrity operational event log. This log can be examined with the Event Viewer using the following path:

Application and Services Logs | Microsoft | Windows | CodeIntegrity | Operational

Looking through these events, I noticed that Windows caught the export driver that we built earlier in the chapter:

Microsoft does provide an official channel to disable KMCS (in an effort to make life easier for developers). You can either attach a kernel debugger to a system or press the F8 button during startup. If you press F8, one of the bootstrap options is Disable Driver Signature Enforcement. In the past, there was a BCDedit.exe option to disable driver signing requirements that has since been removed.

KMCS Countermeasures

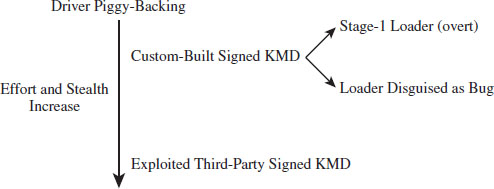

So just how does one deal with driver signing requirements? How can you load arbitrary code into kernel space when Microsoft has imposed the restriction that only signed KMDs can gain entry? One approach is simply to piggyback on an existing driver (see Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7

If you have the money and a solid operational cover, you can simply buy an SPC and distribute your code as a signed driver. From a forensic standpoint, however, this is way too brazen. You should at least try to make your signed driver less conspicuous by implementing functionality to load code from elsewhere into memory so that your primary attack payload isn’t embedded in the signed driver. In the domain of exploit development, this is known as a stage-1 loader.

This is exactly the approach that Linchpin Labs took. In June 2007, Linchpin released the Atsiv Utility, which was essentially a signed driver that gave users the ability to load and unload unsigned drivers. The Atsiv driver was signed and could be loaded by Vista running on x64 hardware. The signing certificate was registered to a company (DENWP ATSIV INC) that was specifically created by people at Linchpin Labs for this purpose. Microsoft responded exactly as you would expect them to. In August 2007, they had VeriSign revoke the Atsiv certificate. Then they released an update for Windows Defender that allows the program to detect and remove the Atsiv driver.

A more subtle tact would be to create a general-purpose KMD that actually has a legitimate purpose (like mounting a virtual file system) and then discreetly embed a bug that could be leveraged to load code into kernel space. This at least affords a certain amount of plausible deniability.

Yet another way to deal with driver signing requirements would be to shift your attention to legitimate third-party drivers distributed by a trusted vendor. Examples of this have already cropped up in the public domain. In July 2007, a Canadian college student named Alex Ionescu (now a contributor to the Windows Internals series) posted a tool called Purple Pill on his blog. The tool included a signed driver from ATI that could be dropped and exploited to perform arbitrary memory writes to kernel space, allowing unsigned drivers to be loaded. Several weeks later, perhaps with a little prodding from Microsoft, ATI patched the drivers to address this vulnerability.

ASIDE

How long would it have taken ATI to patch this flaw had it not been brought to light? How many other signed drivers possess a flaw like this? Are these bugs really bugs? In a world where heavily funded attacks are becoming a reality, it’s entirely plausible that a fully functional hardware driver may intentionally be released with a back door that’s carefully disguised as a bug. Think about it for a minute.

This subtle approach offers covert access with the added benefit of plausible deniability. If someone on the outside discovers the bug and publicizes his or her findings, the software vendor can patch the “bug” and plead innocence. No alarms will sound, nobody gets pilloried. After all, this sort of thing happens all the time, right?

It’ll be business as usual. The driver vendor will go out and get a new code signing certificate, sign their “fixed” drivers, then have them distributed to the thousands of machines through Windows Update. Perhaps the driver vendor will include a fresh, more subtle, bug in the “patch” so that the trap door will still be available to the people who know of it (now that’s what I call chutzpah).

In June 2010, researchers from anti-virus vendor VirusBlokAda headquartered in Belarus published a report on the Stuxnet rootkit, which used KMDs signed using a certificate that had been issued to Realtek Semiconductor Corp. from VeriSign. Investigators postulated that the KMDs may be legitimate modules that were subverted, but no official explanation has been provided to explain how this rootkit commandeered a genuine certificate belonging to a well-known hardware manufacturer. Several days after VirusBlokAda released its report, VeriSign revoked the certificate in question.

At the end of the day, the intent behind these signing requirements is to associate a driver with a publisher (i.e., authentication). So, in a sense, Microsoft would probably acknowledge that this is not intended as a foolproof security mechanism.

Kernel Patch Protection (KPP)

KPP, also known as PatchGuard, was originally implemented to run on the 64-bit release of XP and the 64-bit release of Windows Server 2003 SP1. It has been included in subsequent releases of 64-bit Windows.

PatchGuard was originally deployed in 2005. Since then, Microsoft has released several upgrades (e.g., Version 2 and Version 3) to counter bypass techniques. Basically, what PatchGuard does is to keep tabs on a handful of system components:

The SSDT

The SSDT

The IDT(s) (one for each core)

The IDT(s) (one for each core)

The GDT(s) (one for each core)

The GDT(s) (one for each core)

The MSR(s) used by SYSENTER (one for each core)

The MSR(s) used by SYSENTER (one for each core)

Basic system modules.

Basic system modules.

The system modules monitored include:

ntoskrnl.exe

ntoskrnl.exe

hal.dll

hal.dll

ci.dll

ci.dll

kdcom.dll

kdcom.dll

pshed.dll

pshed.dll

clfs.dll

clfs.dll

ndis.sys

ndis.sys

tcpip.sys

tcpip.sys

Periodically, PatchGuard checks these components against known good copies or signatures. If, during one of these periodic checks, PatchGuard detects a modification, it issues a bug check with a stop code equal to 0x00000109 (CRITICAL_STRUCTURE_CORRUPTION), and the machine dies a fiery Viking death.

KPP Countermeasures

Given that driver code and PatchGuard code both execute in Ring 0, there’s nothing to prevent a KMD from disabling PatchGuard checks (unless, of course, Microsoft takes a cue from Intel and moves beyond a two-ring privilege model). The kernel engineers at Microsoft are acutely aware of this fact and perform all sorts of programming acrobatics to obfuscate where the code resides, what it does, and the internal data-structures that it manipulates. In other words, they can’t keep you from modifying PatchGuard code, so they’re going to try like hell to hide it.

Companies like Authentium and Symantec have announced that they’ve found methods to disable PatchGuard. Specific details available to the general public have also appeared in a series of three articles published by Uniformed.org. Given this book’s focus on IA-32 as the platform of choice, I will relegate details of the countermeasures to the three articles at Uniformed.org. Inevitably this is a losing battle. If someone really wants to invest the time and resources to figure out how things work, they will. Microsoft is hoping to raise the bar high enough such that most engineers are discouraged from doing so.

Note: The all-seeing eye of KPP probably isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be. Let’s face it, the code integrity checks can’t be everywhere at once any more than the police. If you institute temporary modifications to the Windows executive just long enough to do whatever it is you need to do and then restore the altered code to its original state, you may be able to escape detection altogether. All you need is a few milliseconds.

6.7 Synchronization

KMDs often manipulate data structures in kernel space that other OS components touch. To protect against becoming conspicuous (i.e., bug checks), a rootkit must take steps to ensure that it has mutually exclusive access to these data structures.

Windows has its own internal synchronization primitives that it uses to this end. The problem is that they aren’t exported, making it problematic for us to use the official channels to get something all to ourselves. Likewise, we could define our own spin locks and mutex objects within a KMD. The roadblock in this case is that our primitives are unknown to the rest of the operating system. This leaves us to use somewhat less direct means to get exclusive access.

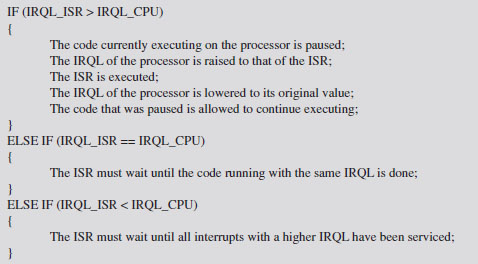

Interrupt Request Levels

Each interrupt is mapped to an interrupt request level (IRQL) indicating its priority so that when the processor is faced with multiple requests, it can attend to more urgent interrupts first. The interrupt service routine (ISR) associated with a particular interrupt runs at the interrupt’s IRQL. When an interrupt occurs, the operating system locates the ISR, via the interrupt descriptor table (IDT), and assigns it to a specific processor. What happens next depends upon the IRQL that the processor is currently running at relative to the IRQL of the ISR.

Assume the following notation:

IRQL_CPU _ the IRQL at which the processor is currently executing.

IRQL_ISR _ the IRQL assigned to the interrupt handler.

The system uses the following algorithm to handle interrupts:

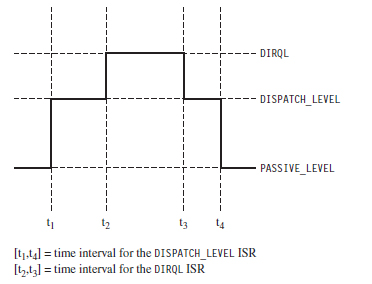

This basic algorithm accommodates interrupts occurring on top of other interrupts. In other words, at any point, an ISR can be paused if an interrupt arrives that has a higher IRQL than the current one being serviced (see Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.8

This basic scheme ensures that interrupts with higher IRQLs have priority. When a processor is running at a given IRQL, interrupts with an IRQL less than or equal to that of the processor are masked off. However, a thread running at a given IRQL can be interrupted to execute instructions running at a higher IRQL.

ASIDE

Try not to get IRQLs confused with thread scheduling and thread priorities, which dictate how the processor normally splits up its time between contending paths of execution. Like a surprise visit by a head of state, interrupts are exceptional events that demand special attention. The processor literally puts its thread processing on hold until all outstanding interrupts have been handled. When this happens, thread priority becomes meaningless and IRQL is all that matters. If a processor is executing code at an IRQL above PASSIVE_LEVEL, then the thread that the processor is executing can only be preempted by a thread possessing higher IRQL. This explains how IRQL can be used as a synchronization mechanism on single-processor machines.

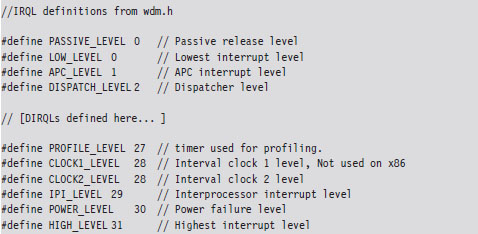

Each IRQL is mapped to a specific integer value. However, the exact mapping varies based on the processor being used. The following macro definitions, located in wdm.h, specify the IRQL-to-integer mapping for the IA-32 processor family.

User-mode programs execute PASSIVE_LEVEL, as do common KMD routines (e.g., DriverEntry(), Unload(), most IRP dispatch routines, etc.). The documentation that ships with the WDK indicates the IRQL required in order for certain driver routines to be called. You may notice there’s a nontrivial gap between DISPATCH_LEVEL and PROFILE_LEVEL. This gap is for arbitrary hardware device IRQLs, known as DIRQLs.

Windows schedules all threads to run at IRQLs below DISPATCH_LEVEL. The operating system’s thread scheduler runs at an IRQL of DISPATCH_LEVEL. This is important because it means that a thread running at or above an IRQL of DISPATCH_LEVEL cannot be preempted because the thread scheduler itself must wait to run. This is one way for threads to gain mutually exclusive access to a resource on a single-processor system.

Multiprocessor systems are more subtle because IRQL is processor-specific. A given thread, accessing some shared resource, may be able to ward off other threads on a given processor by executing at or above DISPATCH_LEVEL. However, there’s nothing to prevent another thread on another processor from concurrently accessing the shared resource. In this type of multiprocessor scenario, normally a synchronization primitive like a spin lock might be used to control who gets sole access. Unfortunately, as explained earlier, this isn’t possible because we don’t have direct access to the synchronization objects used by Windows and, likewise, Windows doesn’t know about our primitives.

What do we do? One clever solution, provided by Hoglund and Butler in their book on rootkits, is simply to raise the IRQL of all processors to DISPATCH_LEVEL. As long as you can control the code that’s executed by each processor at this IRQL, you can acquire a certain degree of exclusive access to a shared resource.

For example, you could conceivably set things up so that one processor runs the code that accesses the shared resource and all the other processors execute an empty loop. One might see this as sort of a parody of a spin lock.

ASIDE

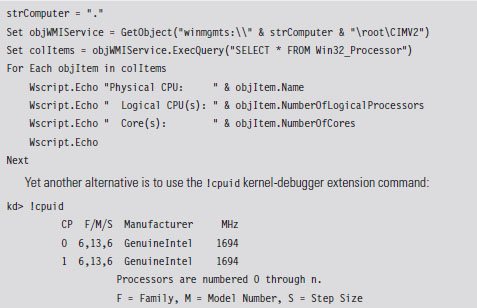

The most direct way to determine the number of processors (or cores) installed on a machine is to perform a system reset and boot into the BIOS setup program. If you can’t afford to reboot your machine (perhaps you’re in a production environment), you can always use the Intel Processor Identification Tool. There’s also the coreinfo.exe tool that ships with the Sysinternals tool suite (my personal favorite). If you don’t want to download software, you can always run the following Windows management interface (WMI) script:

There are a couple of caveats to this approach. The first caveat is you’ll need to be judicious about what you do while executing at the DISPATCH_LEVEL IRQL. In particular, the processor cannot service page faults when running at this IRQL. This means that the corresponding KMD code must be running in non-paged memory, and all of the data that it accesses must also reside in non-paged memory. To do otherwise would be to invite a bug check.

The second caveat is that the machine’s processors will still service interrupts assigned to an IRQL above DISPATCH_LEVEL. This isn’t such a big deal, however, because such interrupts almost always correspond to hardware-specific events that have nothing to do with manipulating the system data structures that our KMD will be accessing. In the words of Hoglund and Butler, this solution offers a form of synchronization that is “relatively safe” (not foolproof).

Deferred Procedure Calls

When you service a hardware interrupt and have the processor at an elevated IRQL, everything else is put on hold. Thus, the goal of most ISRs is to do whatever they need to do as quickly as possible.

In an effort to expedite interrupt handling, a service routine may decide to postpone particularly expensive operations that can afford to wait. These expensive operations are rolled up into a special type of routine, a deferred procedure call (DPC), which the ISR places into a system-wide queue. Later on, when the DPC dispatcher invokes the DPC routine, it will execute at an IRQL of DISPATCH_LEVEL (which tends to be less than the IRQL of the originating service routine). In essence, the service routine is delaying certain things to be executed later at a lower priority, when the processor isn’t so busy.

No doubt you’ve seen this type of thing at the post office, where the postal worker behind the counter tells the current customer to step aside to fill out a change-of-address form and then proceeds to serve the next customer.

Another aspect of DPCs is that you can designate which processor your DPC runs on. This feature is intended to resolve synchronization problems that might occur when two processors are scheduled to run the same DPC concurrently.

If you read back through Hoglund and Butler’s synchronization hack, you’ll notice that we need to find a way to raise the IRQL of each processor to DISPATCH_LEVEL. This is why DPCs are valuable in this instance. DPCs give us a convenient way to target a specific processor and have that processor run code at the necessary IRQL.

Implementation

Now we’ll see how to implement our ad hoc mutual-exclusion scheme using nothing but IRQLs and DPCs. We’ll use it several times later on in the book, so it is worth walking through the code to see how things work. The basic sequence of events is as follows:

Step 1. Raise the IRQL of the current CPU to DISPATCH_LEVEL.

Step 1. Raise the IRQL of the current CPU to DISPATCH_LEVEL.

Step 2. Create and queue DPCs to raise the IRQLs of the other CPUs.

Step 2. Create and queue DPCs to raise the IRQLs of the other CPUs.

Step 3. Access the shared resource while the DPCs spin in empty loops.

Step 3. Access the shared resource while the DPCs spin in empty loops.

Step 4. Signal to the DPCs so that they can stop spinning and exit.

Step 4. Signal to the DPCs so that they can stop spinning and exit.

Step 5. Lower the IRQL of the current processor back to its original level.

Step 5. Lower the IRQL of the current processor back to its original level.

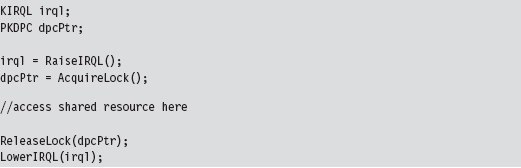

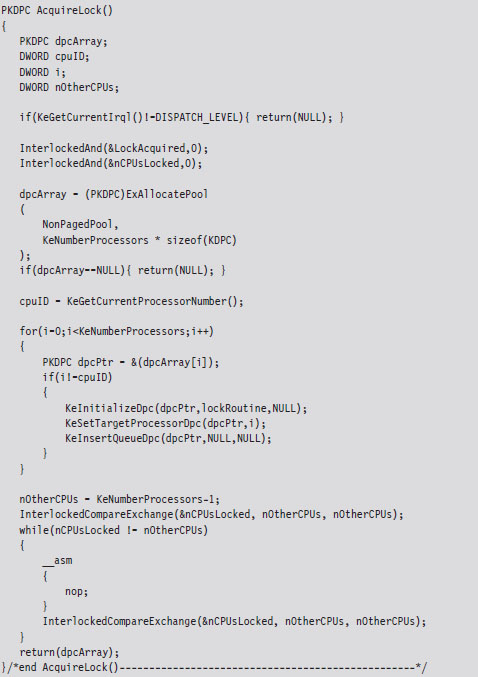

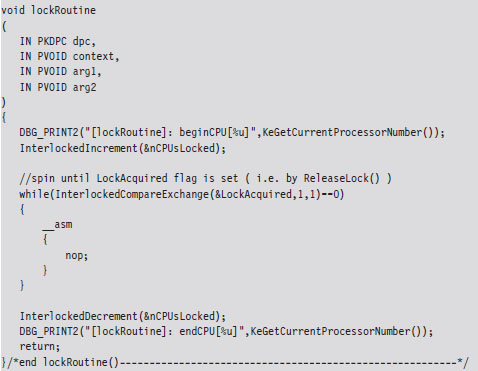

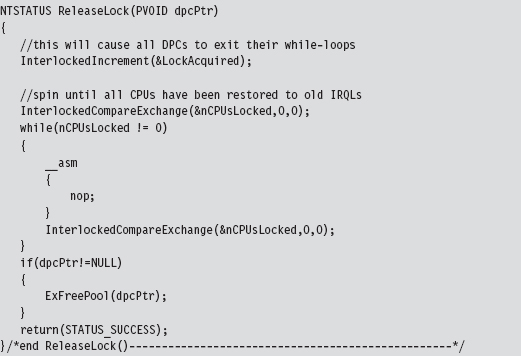

In C code, this looks like:

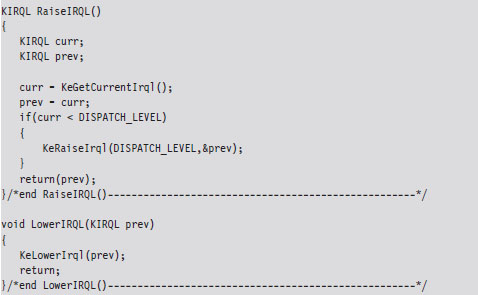

The RaiseIRQL() and LowerIRQL() routines are responsible for raising and lowering the IRQL of the current thread (the thread that will ultimately access the shared resource). These two routines rely on kernel APIs to do most of the lifting (KeRaiseIrql() and KeLowerIrql()).

The other two routines, AcquireLock() and ReleaseLock(), create and decommission the DPCs that raise the other processors to the DISPATCH_LEVEL IRQL. The AcquireLock() routine begins by checking to make sure that the IRQL of the current thread has been set to DISPATCH_LEVEL (in other words, it’s ensuring that RaiseIRQL() has been called).

Next, this routine invokes atomic operations that initialize the global variables that will be used to manage the synchronization process. The LocksAcquired variable is a flag that’s set when the current thread is done accessing the shared resource (this is somewhat misleading because you’d think that it would be set just before the shared resource is to be accessed). The nCPUs-Locked variable indicates how many of the DPCs have been invoked.

After initializing the synchronization global variables, AcquireLock() allocates an array of DPC objects, one for each processor. Using this array, this routine initializes each DPC object, associates it with the lockRoutine() function, then inserts the DPC object into the DPC queue so that the dispatcher can load and execute the corresponding DPC. The routine spins in an empty loop until all of the DPCs have begun executing.

The lockRoutine() function, which is the software payload executed by each DPC, uses an atomic operation to increase the nCPUsLocked global variable by 1. Then the routine spins until the LockAcquired flag is set. This is the key to granting mutually exclusive access. While one processor runs the code that accesses the shared resource (whatever that resource may be), all the other processors are spinning in empty loops.

As mentioned earlier, the LockAcquired flag is set after the main thread has accessed the shared resource. It’s not so much a signal to begin as it is a signal to end. Once the DPC has been released from its empty while-loop, it decrements the nCPUsLocked variable and fades away into the ether.

The ReleaseLock() routine is invoked once the shared resource has been modified and the invoking thread no longer requires exclusive access. This routine sets the LockAcquired flag so that the DPCs can stop spinning and then waits for all of them to complete their execution paths and return (it will know this has happened once the nCPUsLocked global variable is zero).

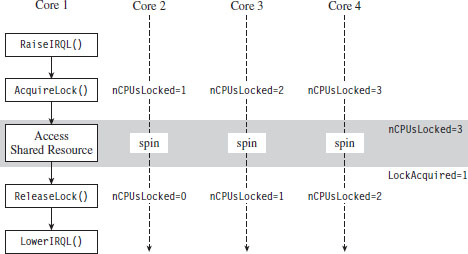

I can sympathize if none of this is intuitive on the first pass. It wasn’t for me. To help get the gist of what I’ve described, take a look at Figure 6.9 and read the summary that follows. Once you’ve digested it, go back over the code for a second pass. Hopefully by then things will be clear.

Figure 6.9

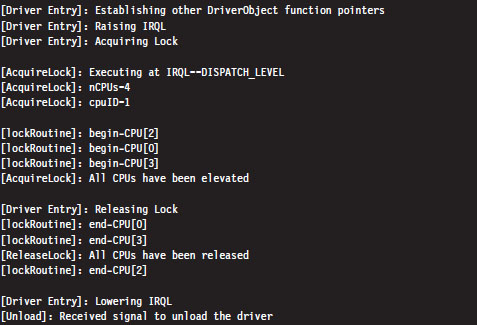

To summarize the basic sequence of events in Figure 6.9:

The code running on one of the processors (Core 1 in this example) raises its own IRQL to preclude thread scheduling on its own processor.

Next, by calling AcquireLock(), the thread running on Core 1 creates a series of DPCs, where each DPC targets one of the remaining processors (Cores 2 through 4). These DPCs raise the IRQL of each processor, increment the nCPUsLocked global variable, and then spin in while-loops, giving the thread on Core 1 the opportunity to safely access a shared resource.

When nCPUsLocked is equal to 3, the thread on Core 1 (which has been waiting in a loop for nCPUsLocked to be 3) will know that the coast is clear and that it can start to manipulate the shared resource.

When the thread on Core 1 is done, it invokes ReleaseLock(), which sets the LockAcquired global variable. Each of the looping DPCs notices that this flag has been set and break out of their loops. The DPCs then each decrement the nCPUsLocked global variable. When this global variable is zero, the Release-Lock() function will know that the DPCs have returned and exit itself. Then the code running on Core 1 can lower its IRQL, and our synchronization campaign officially comes to a close. Whew!

The output of the corresponding IRQL code will look something like:

I’ve added a few print statements and newline characters to make it more obvious as to what’s going on.

One final word of warning: While mutual-exclusive access is maintained in this manner, the entire system essentially grinds to a screeching halt. The other processors spin away in tight little empty loops, doing nothing, while you do whatever it is you need to do with the shared resource. In the interest of performance, it’s a good idea for you to keep things short and sweet so that you don’t have to keep everyone waiting for too long, so to speak.

6.8 Conclusions

Basic training is over. We’ve covered all of the prerequisites that we’ll need to dive into the low-and-slow anti-forensic techniques that rootkits use. We have a basic understanding of how Intel processors facilitate different modes of execution and how Windows leverages these facilities to provide core system services. We surveyed the development tools available to us and how they can be applied to introduce code into obscure regions normally reserved for a select group of system engineers. This marks the end of Part I. We’ve done our homework, and now we can move on to the fun stuff.

1. http://www.microsoft.com/whdc/driver/install/drvsign/kmcs-walkthrough.mspx.

2. http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/STM/cmvp/documents/140-1/140sp/140sp1326.pdf.

3. http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/STM/cmvp/documents/140-1/140sp/140sp890.pdf.