Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First Published: December 2018

Production Reference: 1171218

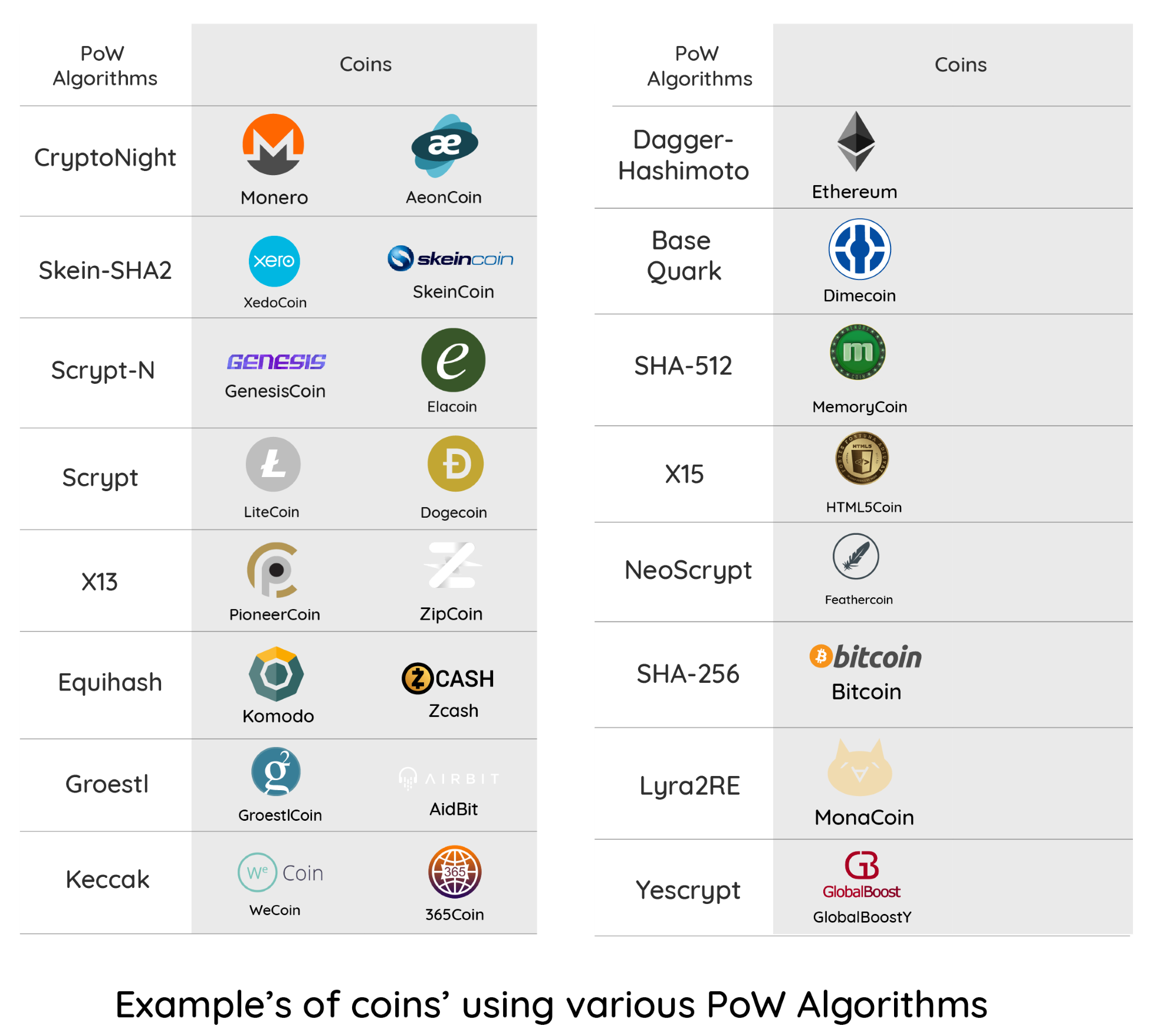

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

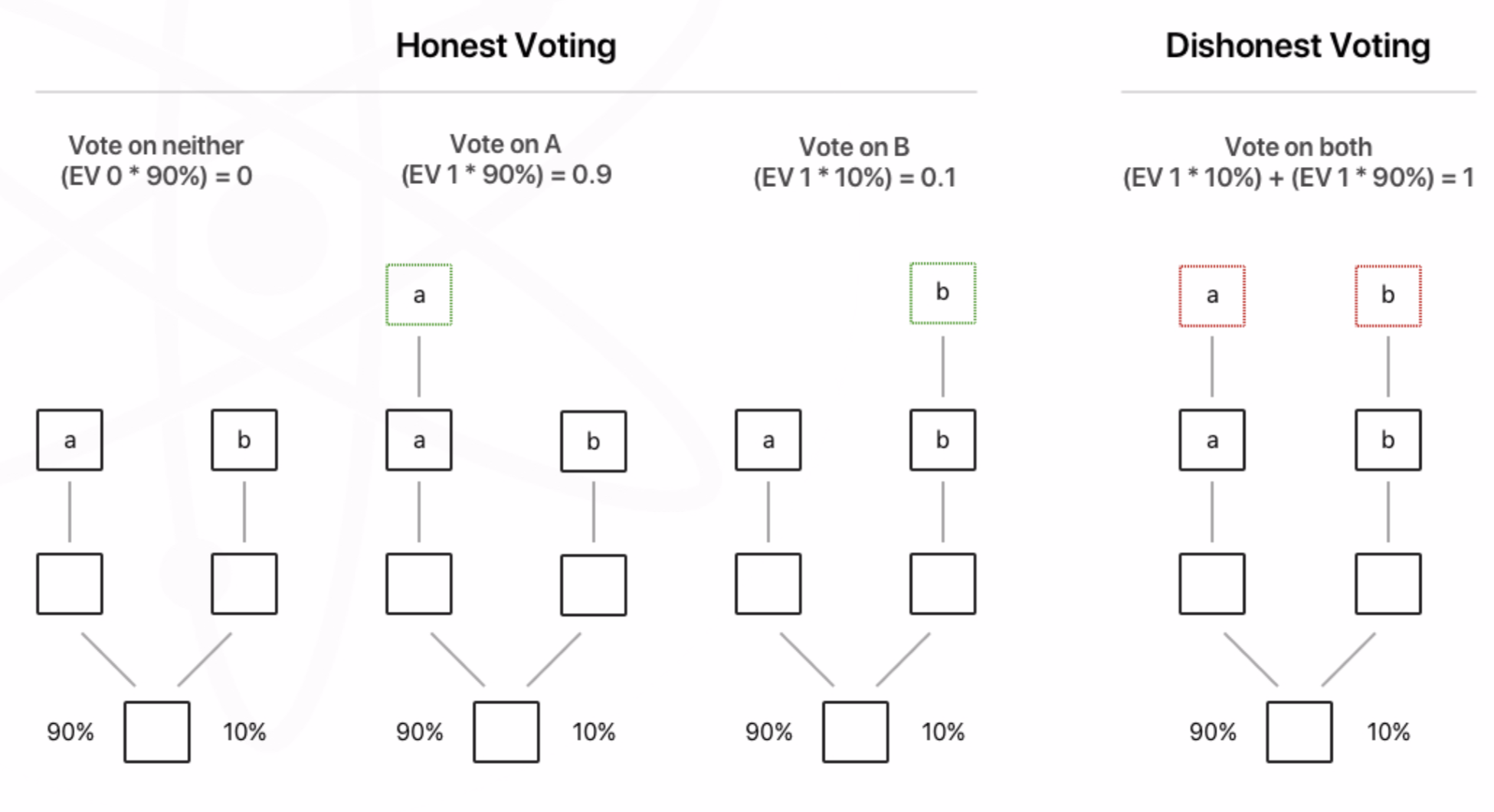

Livery Place, 35 Livery Street

Birmingham, B3 2PB, U.K.

ISBN 978-1-78995-472-2

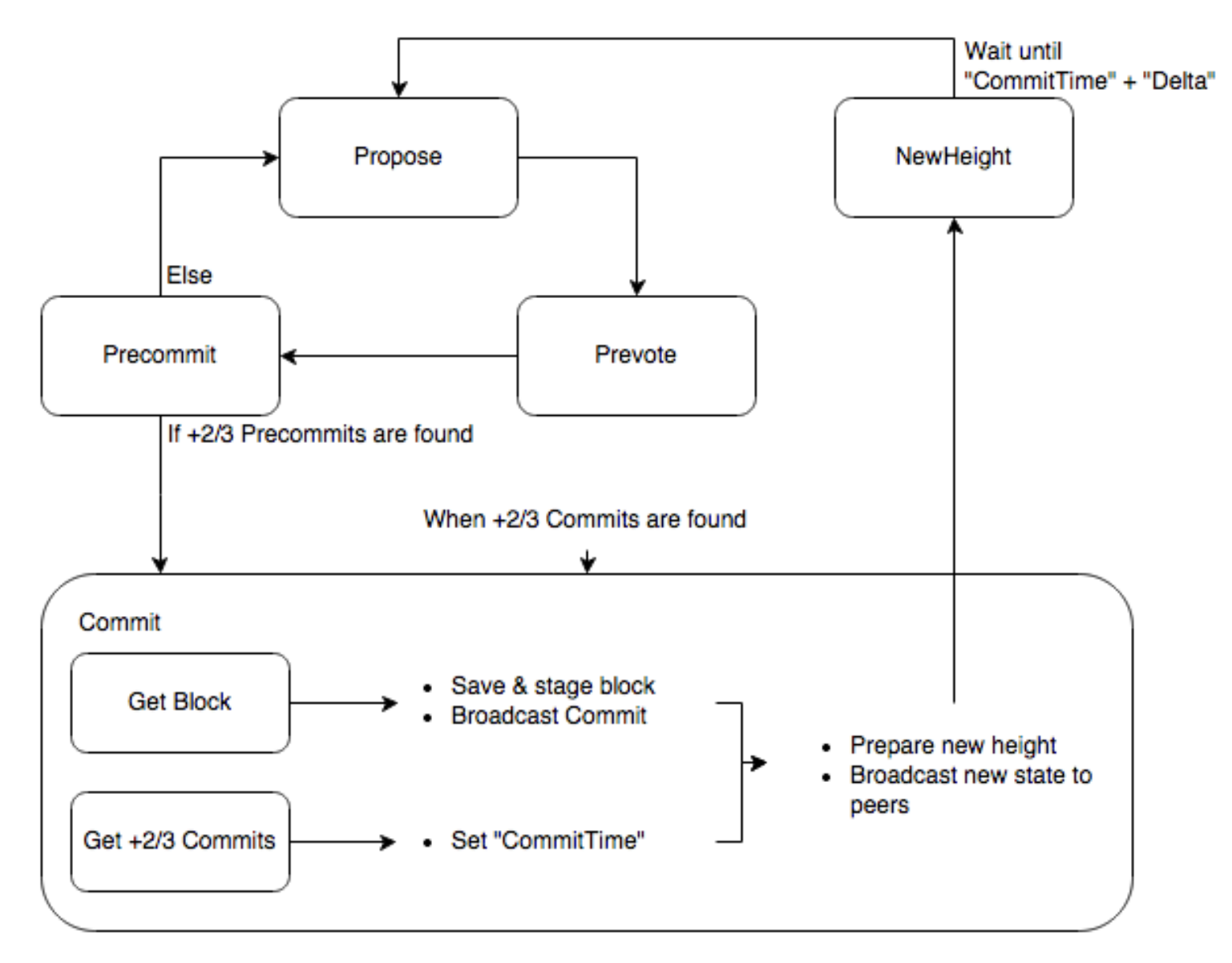

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.packt.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at customercare@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.packt.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Brenn Hill is a senior software engineer who has worked with clients such as NASCAR, PGA Tour, Time Warner Cable, and many others. He has experience leading international teams on cannot fail engineering projects. He strives to work with business to ensure that tech projects achieve good ROI and solve key business problems. He has a master's degree in Information Science from UNC-CH and currently travels the world as a digital nomad.

Samanyu Chopra is a developer, entrepreneur, and Blockchain supporter with wide experience of conceptualizing, developing, and producing computer and mobile software. He has been programming since the age of 11. He is proficient in programming languages such as JavaScript, Scala, C#, C++, Swift, and so on. He has a wide range of experience in developing for computers and mobiles. He has been a supporter of Bitcoin and blockchain since its early days and has been part of wide-ranging decentralized projects for a long time. You can write a tweet to him at @samdonly1.

Paul Valencourt is CFO of BlockSimple Solutions. He currently helps people launch STOs and invest in cryptocurrency mining.

Narayan Prusty is the founder and CTO of BlockCluster, world's first blockchain management system. He has five years of experience in blockchain. He specializes in Blockchain, DevOps, Serverless, and JavaScript. His commitment has led him to build scalable products for start-ups, governments, and enterprises across India, Singapore, USA, and UAE. He is enthusiastic about solving real-world problems. His ability to build scalable applications from top to bottom is what makes him special. Currently, he is on a mission to make things easier, faster, and cheaper using blockchain. Also, he is looking at ways to prevent corruption, fraud, and to bring transparency to the world using blockchain.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

Getting Started with Blockchain takes you through the electrifying world of blockchain technology. It begins with the basic design of a blockchain and elaborates concepts, such as Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), tokens, smart contracts, and other related terminologies of the blockchain technology. You will then explore the components of Ethereum, such as ether tokens, transactions, and smart contracts that you need to build simple DApps.

This Learning Path also explains why you must specifically use Solidity for Ethereum-based projects and lets you explore different blockchains with easy-to-follow examples. You will learn a wide range of concepts - beginning with cryptography in cryptocurrencies and including ether security, mining, and smart contracts. You will learn how to use web sockets and various API services for Ethereum.

By the end of this Learning Path, you will be able to build efficient decentralized applications.

This Learning Path includes content from the following Packt products:

Getting Started with Blockchain is for you if you want to get to grips with the blockchain technology and develop your own distributed applications. It is also designed for those who want to polish their existing knowledge regarding the various pillars of the blockchain ecosystem. Prior exposure to an object-oriented programming language such as JavaScript is needed.

Chapter 1, Blockchain 101, explains what blockchain technologies are and how they work. We also introduce the concept of the distributed ledger.

Chapter 2, Components and Structure of Blockchain, takes a closer look at the technical underpinnings of a blockchain and peeks under the hood to understand what a block is and how the chain is created.

Chapter 3, Decentralization Versus Distributed Systems, covers different types of decentralized and distributed systems and cover the often-overlooked differences between them.

Chapter 4, Cryptography and Mechanics Behind Blockchain, discusses the fundamentals of cryptographic systems which are critical to the proper functioning of all blockchains.

Chapter 5, Bitcoin, examine Bitcoin, the first blockchain, and it's specific mechanics in depth.

Chapter 6, Altcoins, covers the major non-bitcoin cryptocurrency projects that have gained popularity over the last few years.

Chapter 7, Achieving Consensus, looks into the different ways blockchains help achieve consensus. This is one of the most important aspects of blockchain behavior.

Chapter 8, Advanced Blockchain Concepts, covers the interactions between blockchain technology, privacy, and anonymity along with some of the legal side effects of blockchain technology.

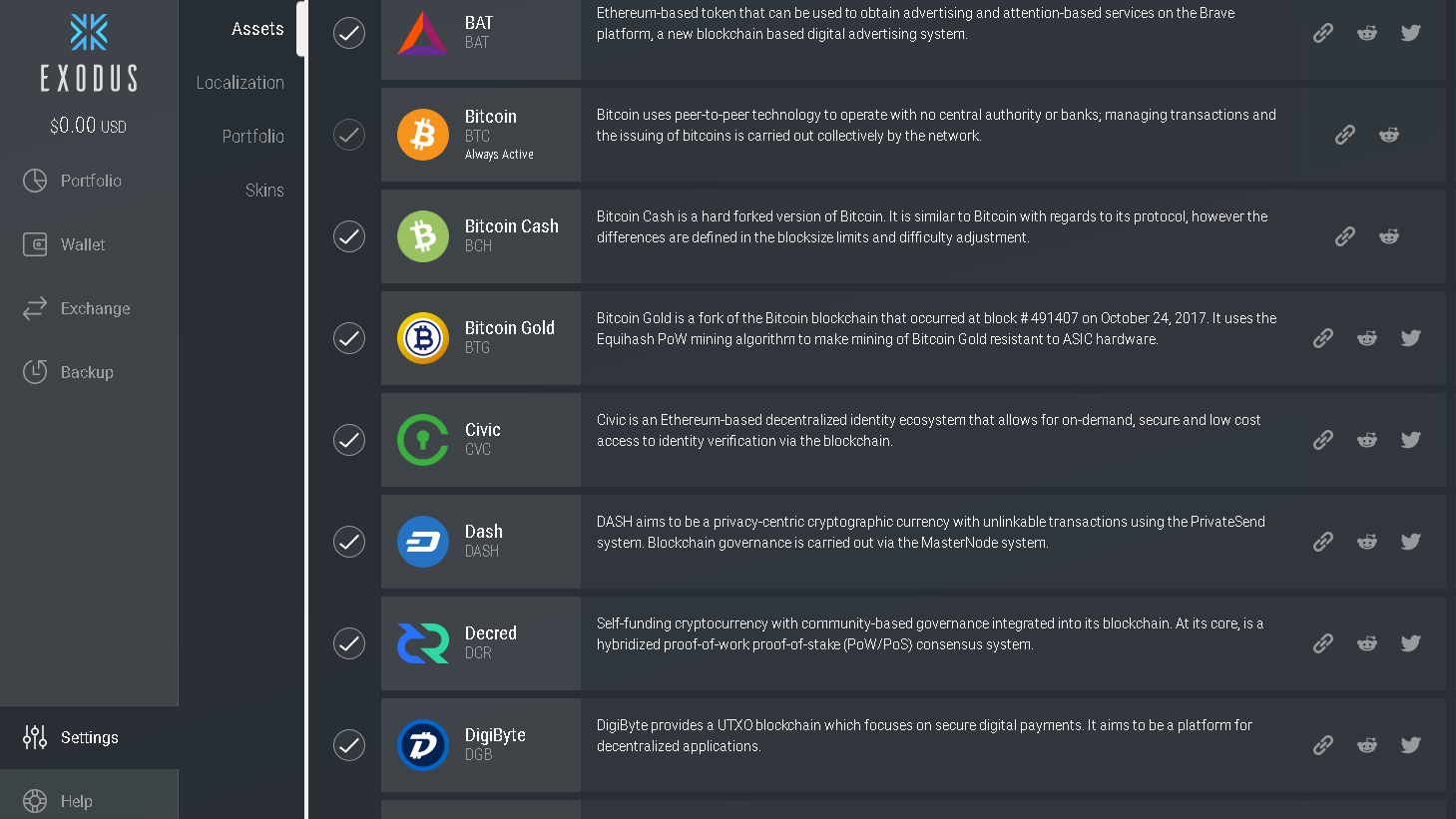

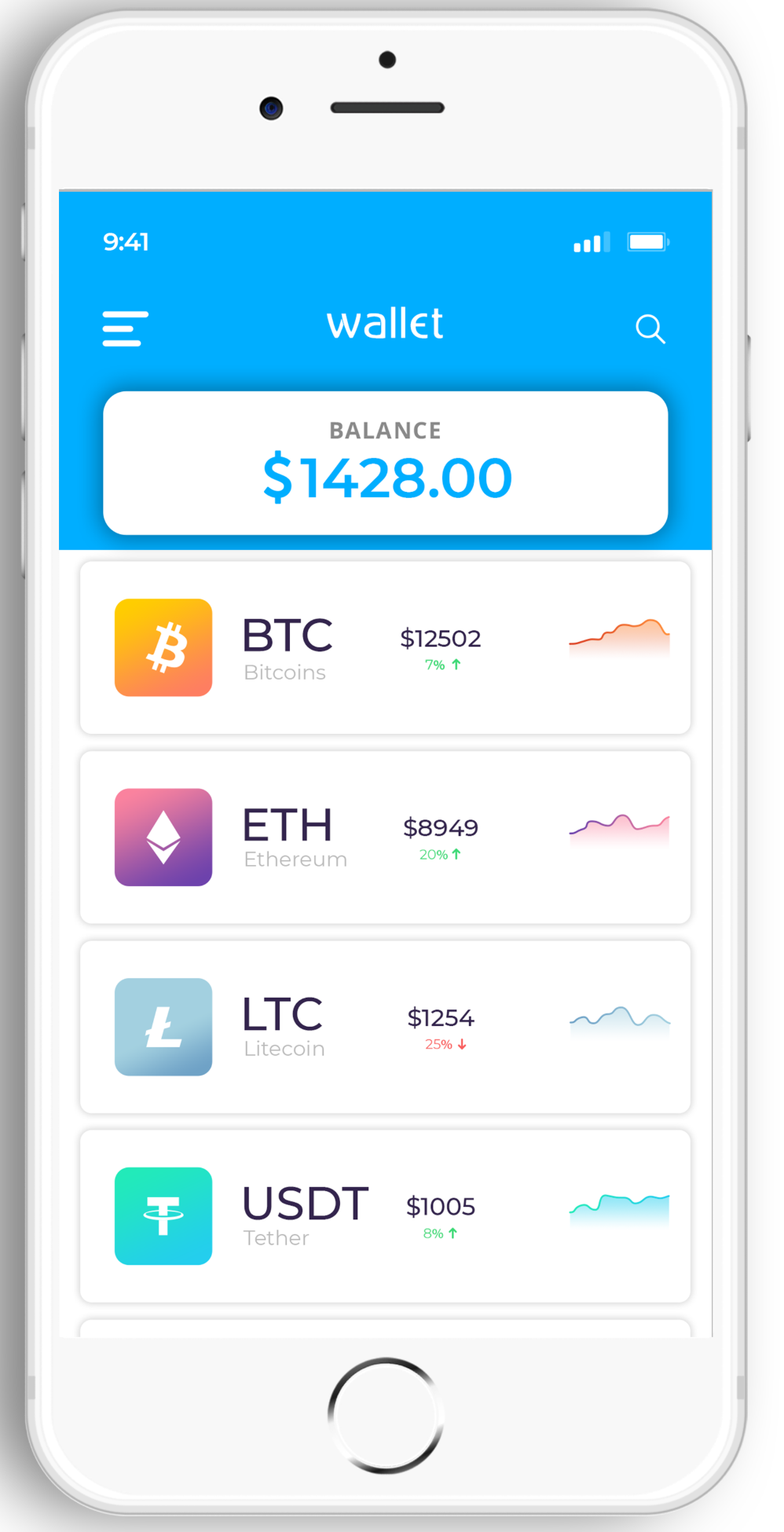

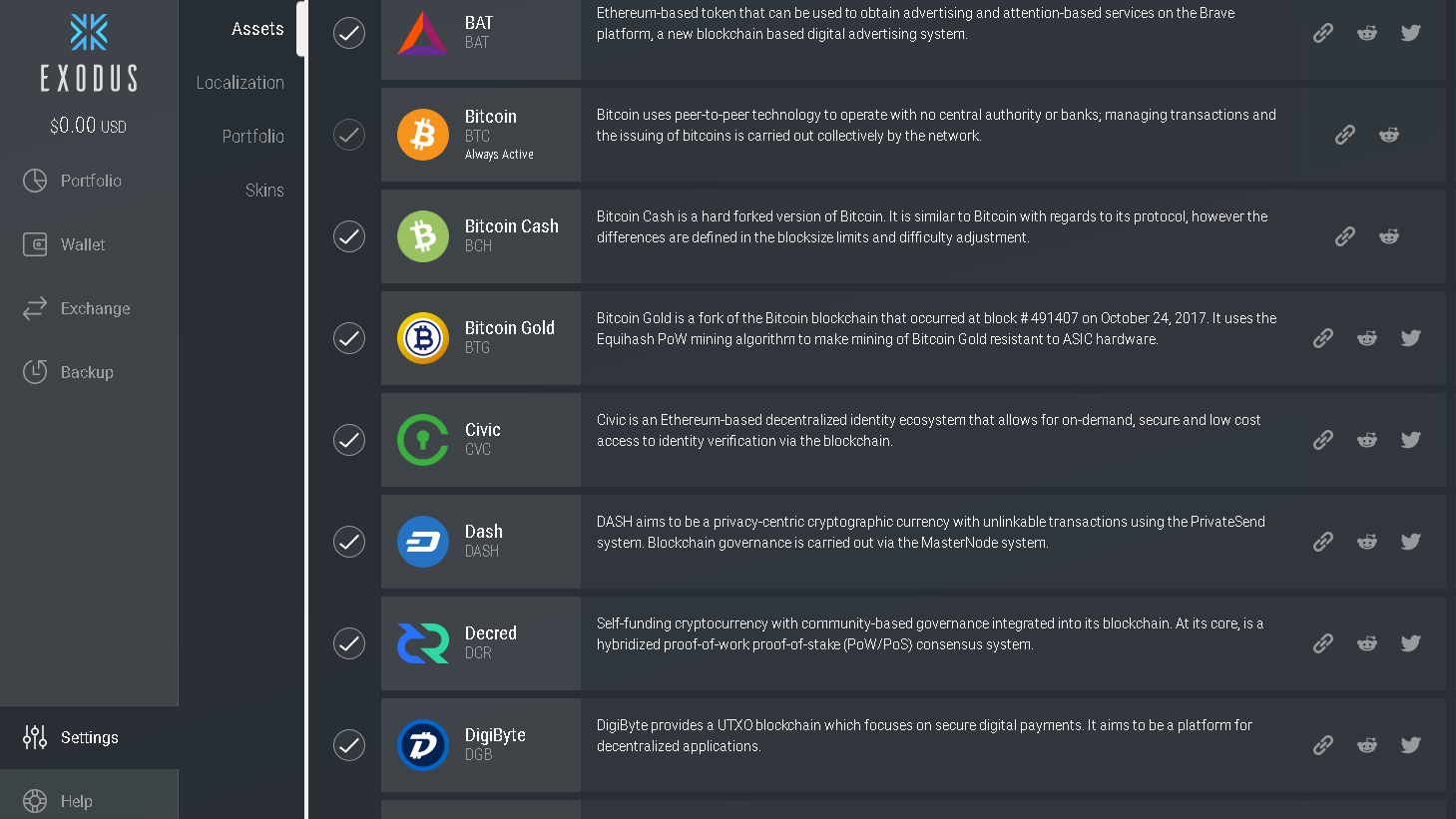

Chapter 9, Cryptocurrency Wallets, covers the different wallet solutions that exist for keeping your cryptocurrency secure.

Chapter 10, Alternate Blockchains, examine blockchain creation technologies such as Tendermint and Graphene, and other non-currency based blockchain technologies.

Chapter 11, Hyperledger and Enterprise Blockchains, examine the Hyperledger family of distributed ledger technologies aimed at corporate and enterprise use.

Chapter 12, Ethereum 101, look at Ethereum, the second most dominant blockchain technology today.

Chapter 13, Solidity 101, cover the basics of Solidity, the Ethereum programming language.

Chapter 14, Smart Contracts, covers the smart contracts, which are enabled in different ways by different blockchain technologies.

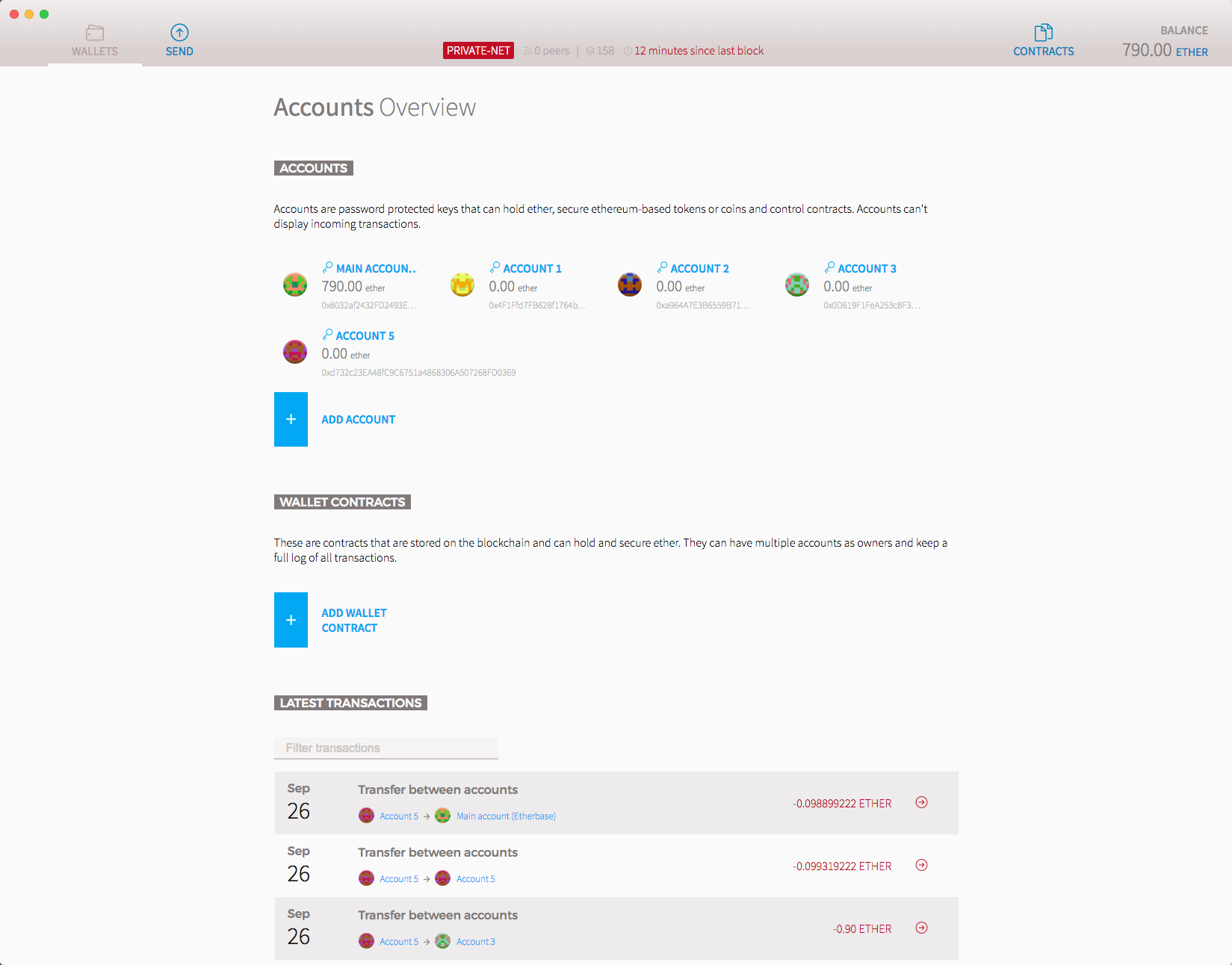

Chapter 15, Ethereum Accounts and Ether Tokens, in this chapter, we look at the mechanics of Ethereum accounts and the token itself in the Ethereum system.

Chapter 16, Decentralized Applications, discusses decentralized applications as a whole, including ones that operate without a blockchain or in tandem with blockchain technologies.

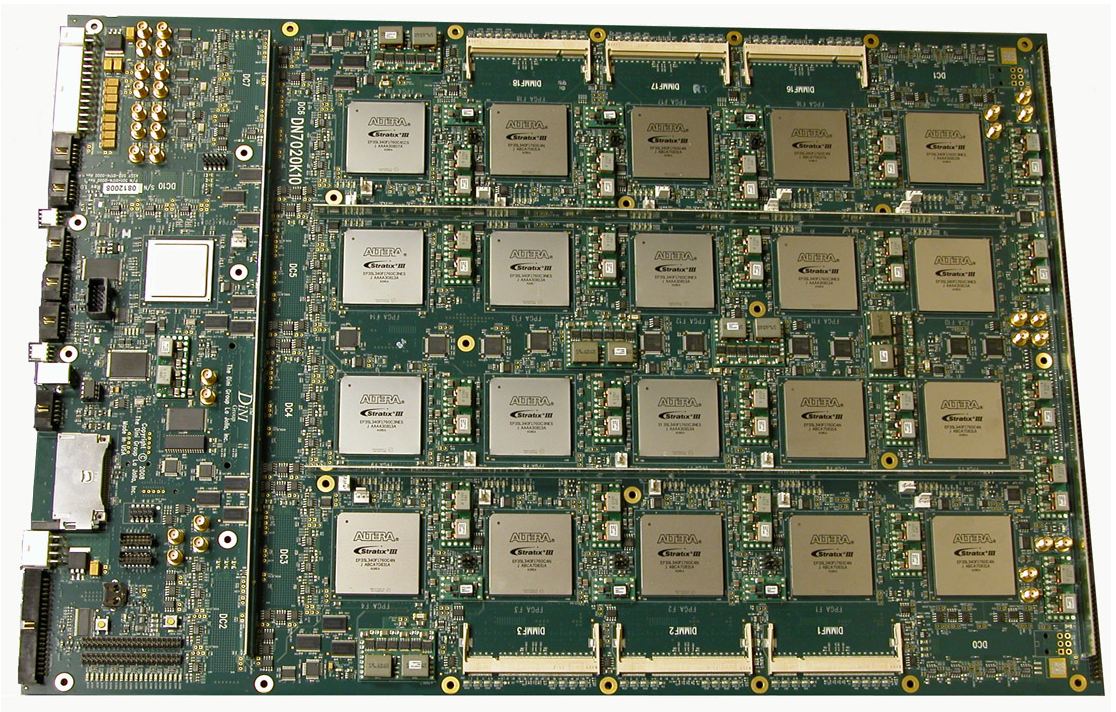

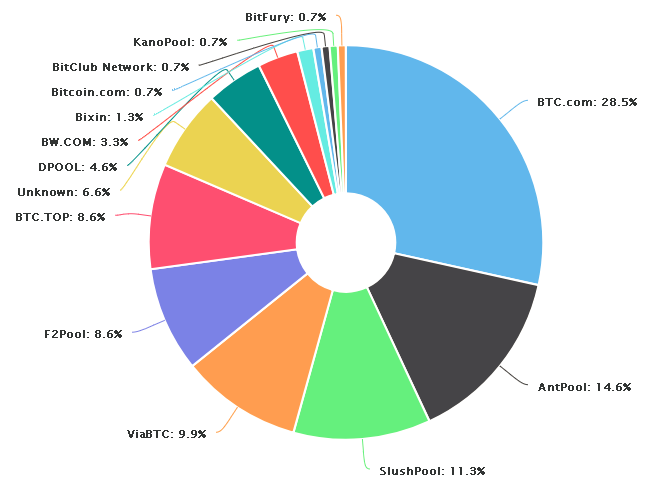

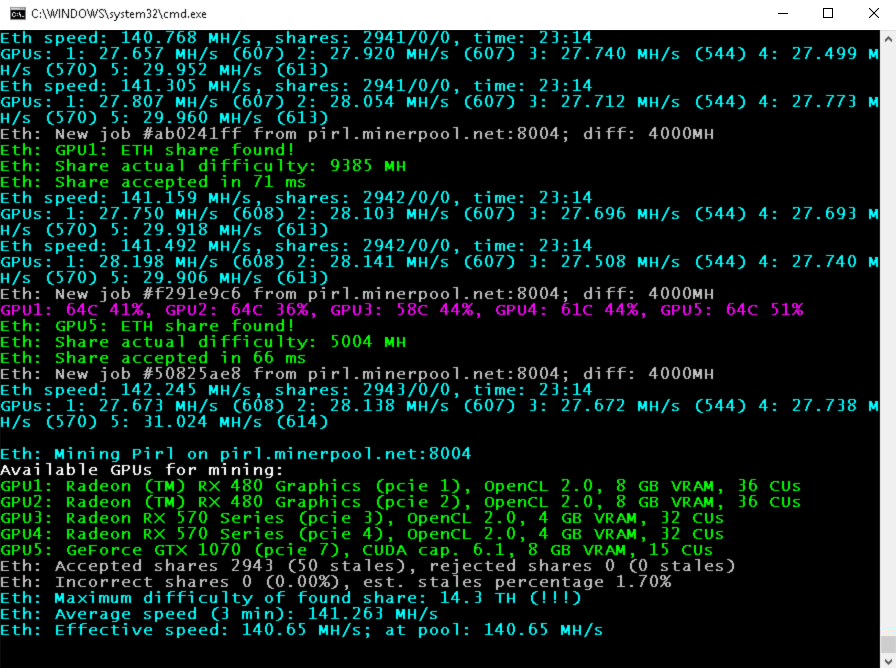

Chapter 17, Mining, we cover blockchain mining and how this is used to secure blockchains, the different types of hardware used in mining, and the different protocols involved.

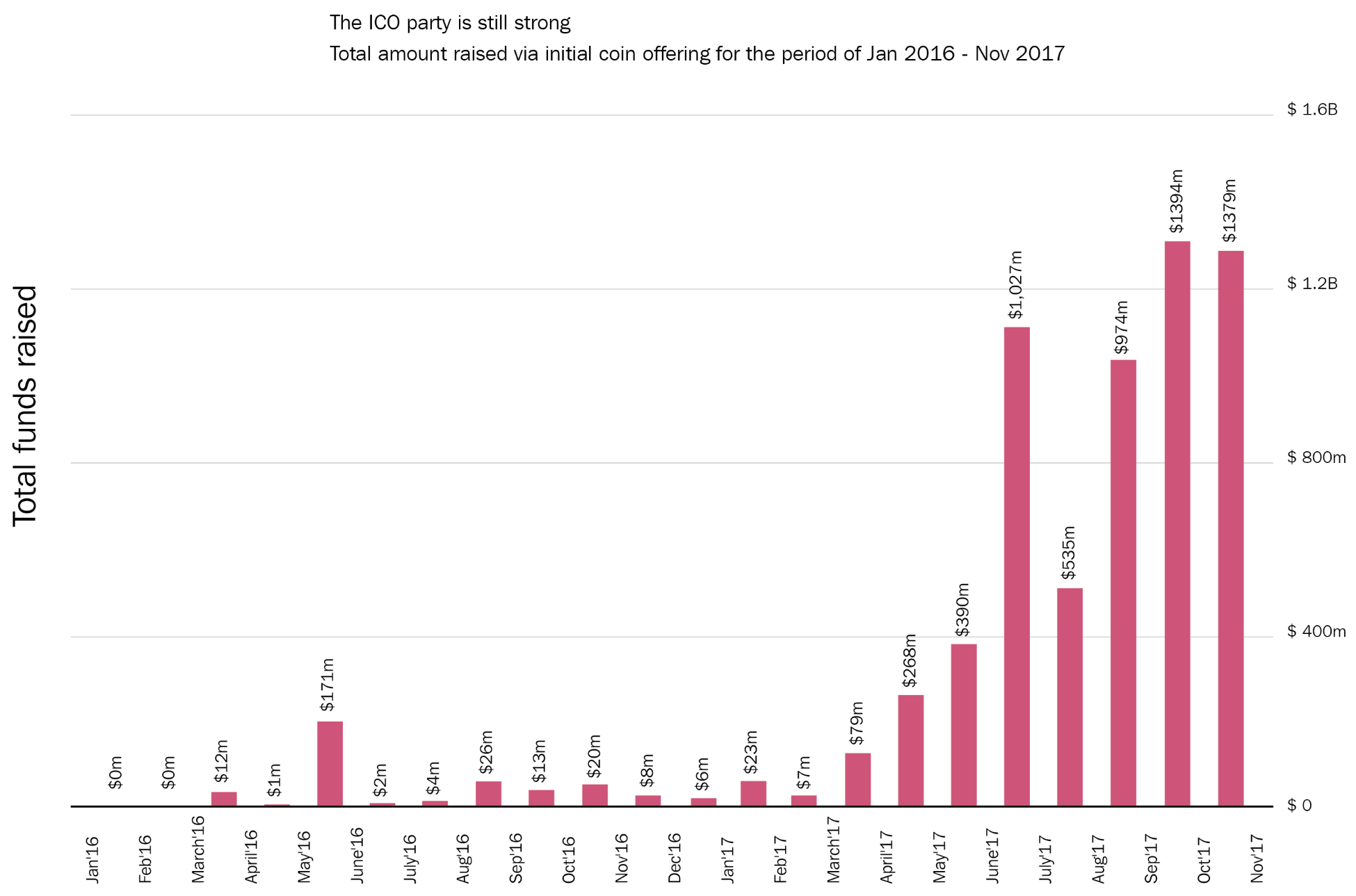

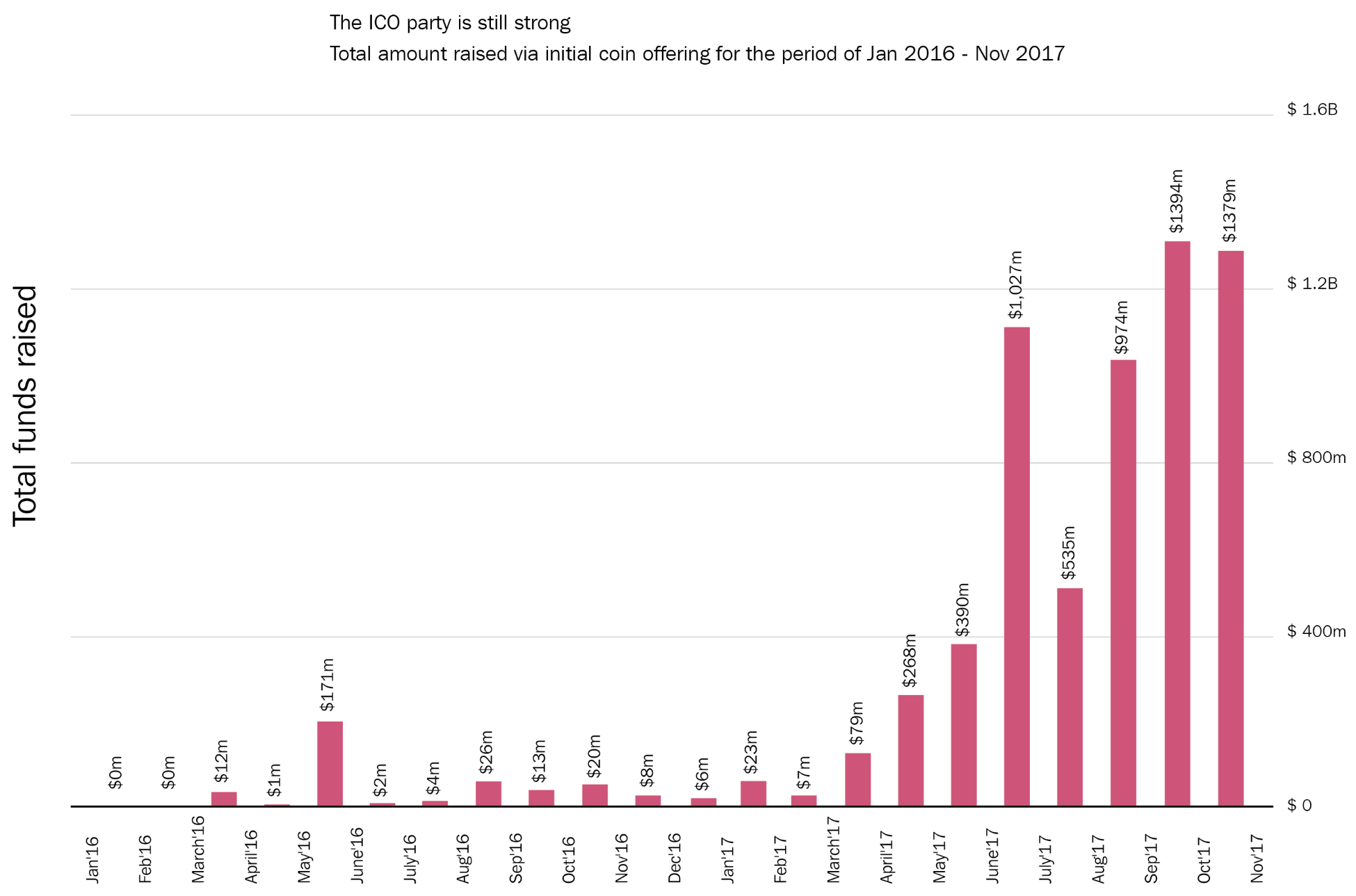

Chapter 18, ICO 101, we cover the basics of launching an Initial Coin Offering or Initial Token Offering.

Chapter 19, Creating Your Own Currency, we cover the creation of your own blockchain based cryptocurrency.

Chapter 20, Scalability and Other Challenges, covers the difficulties and limitations currently facing blockchain technology.

Chapter 21, Future of Blockchain, we examine the possible future developments of the industry technologically, legally, and socially.

Chapter 22, Understanding Decentralized Applications, will explain what DApps are and provide an overview of how they work.

Chapter 23, Understanding How Ethereum Works, explains how Ethereum works.

Chapter 24, Writing Smart Contracts, shows how to write smart contracts and use geth's interactive console to deploy and broadcast transactions using web3.js.

Chapter 25, Getting Started with web3.js, introduces web3js and how to import, connect to geth, and explains use it in Node.js or client-side JavaScript.

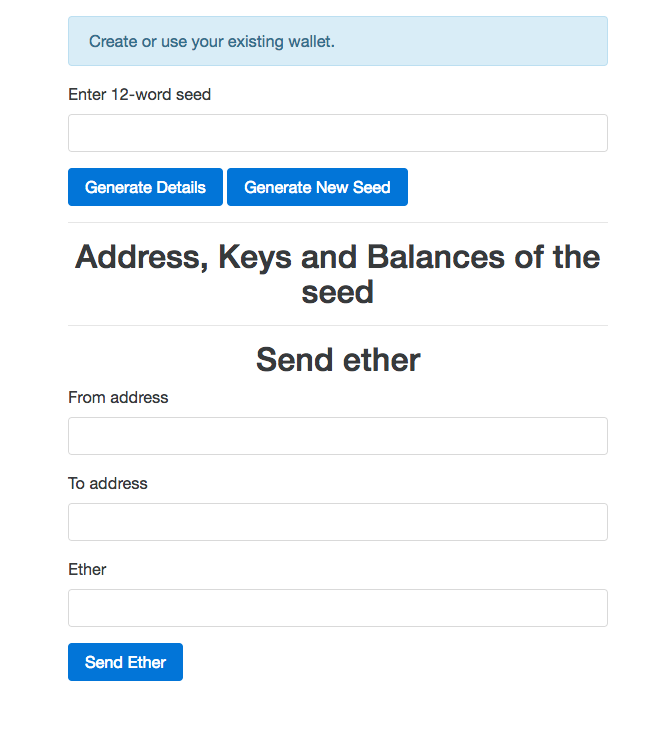

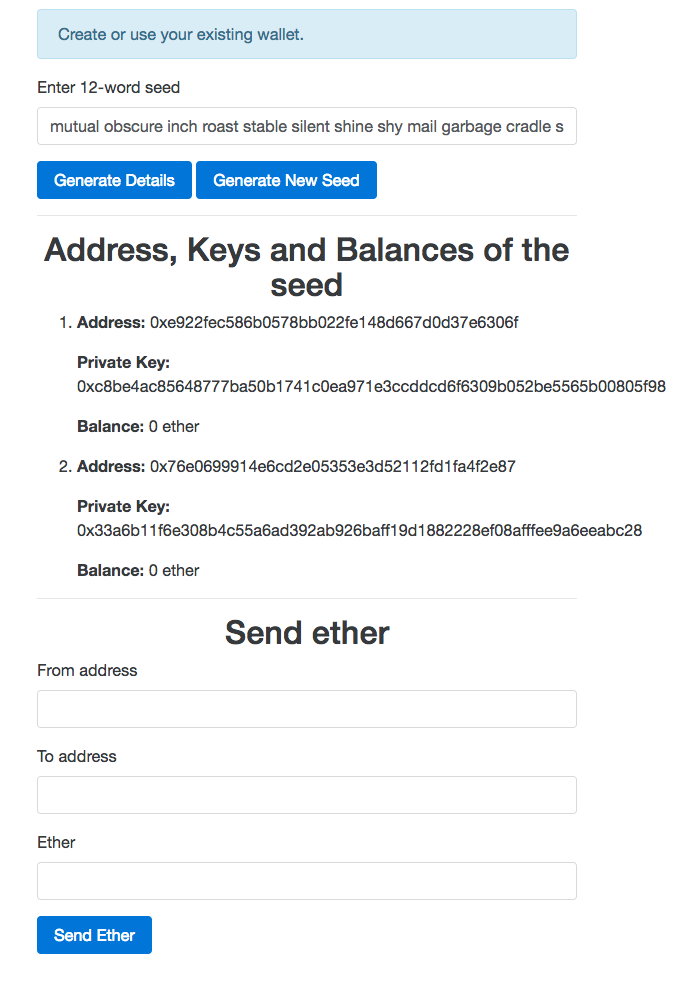

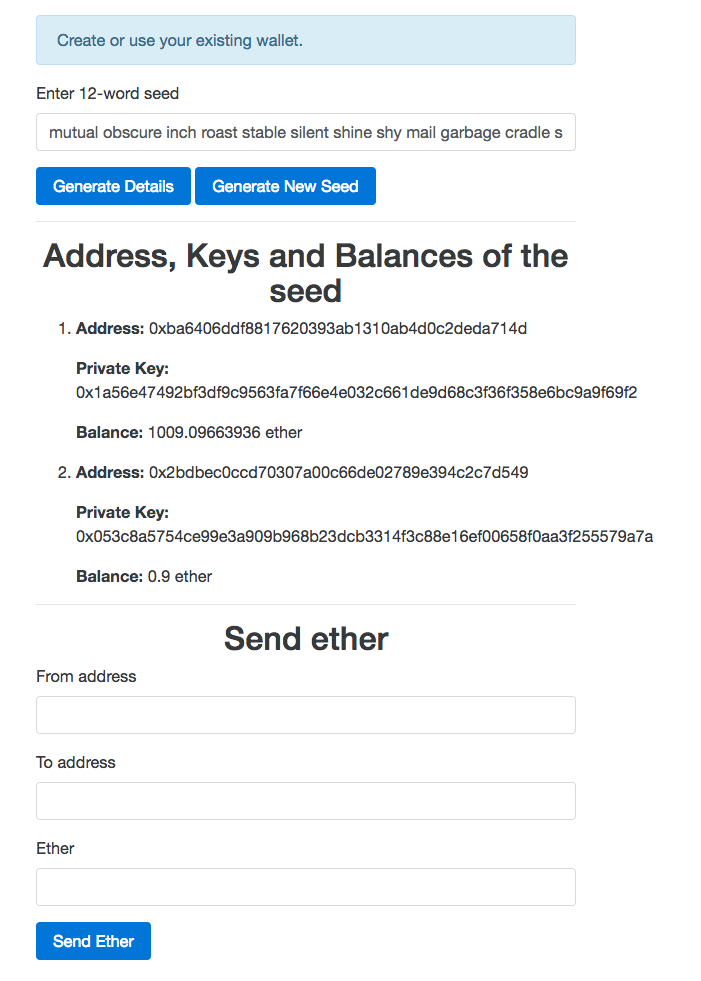

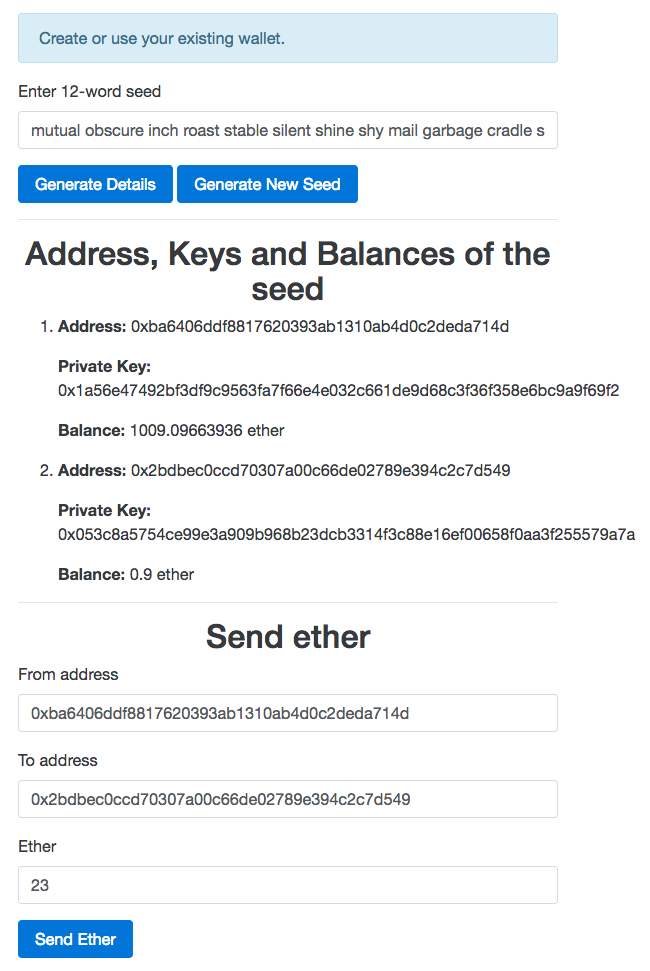

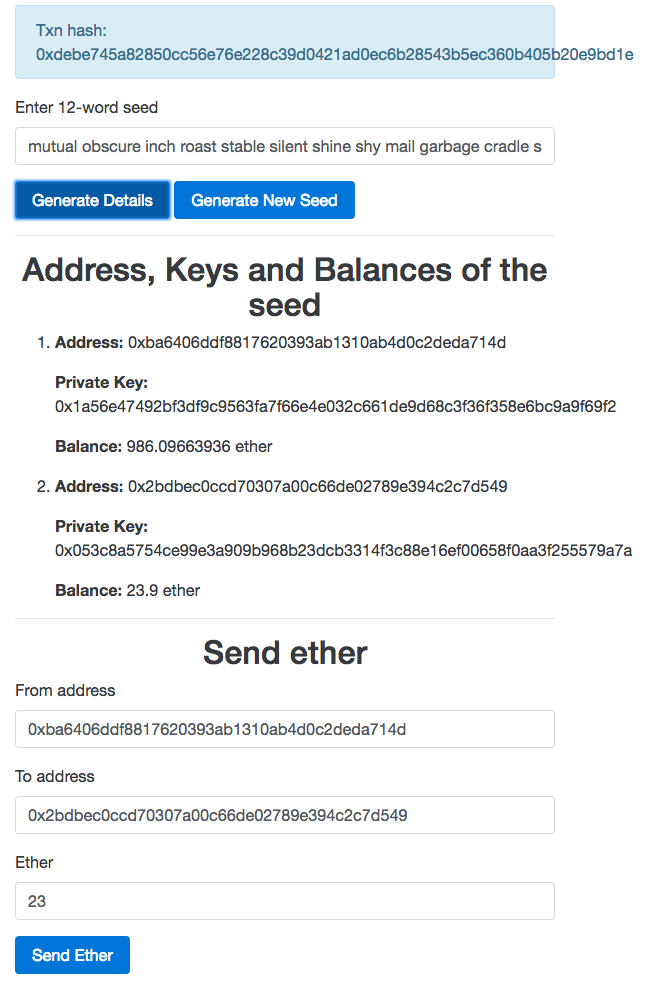

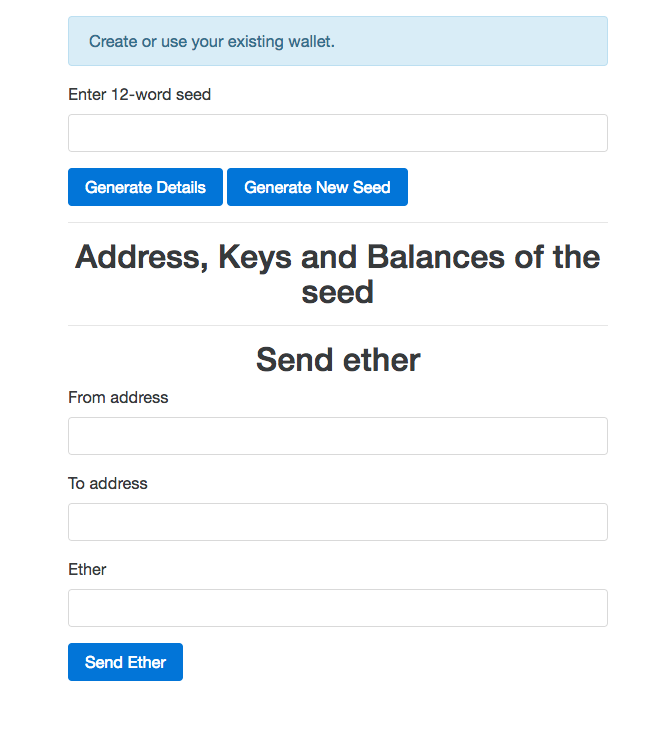

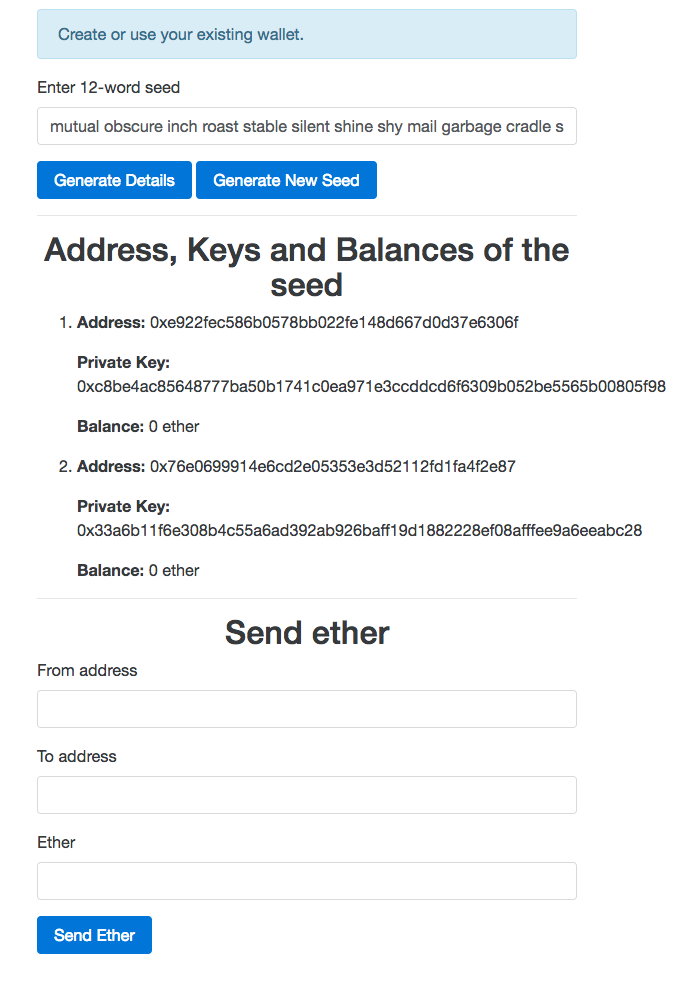

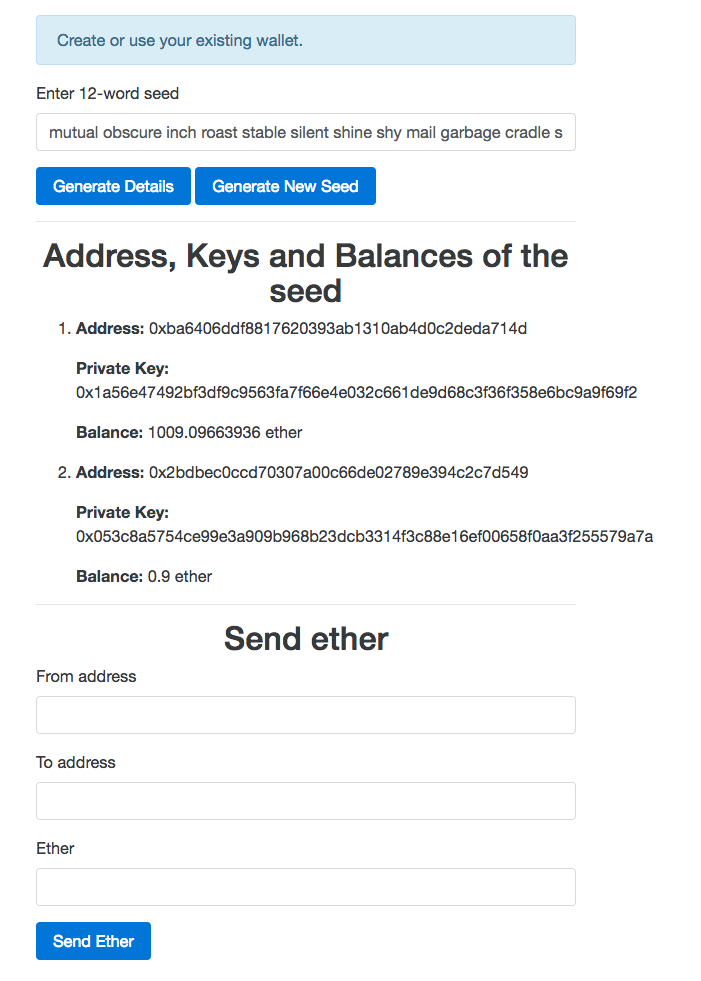

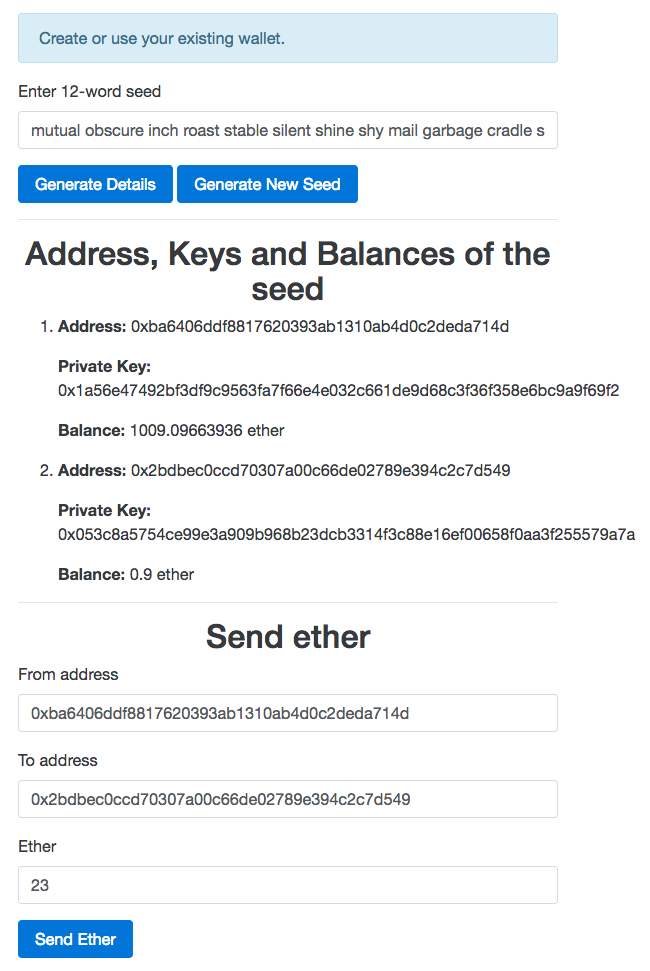

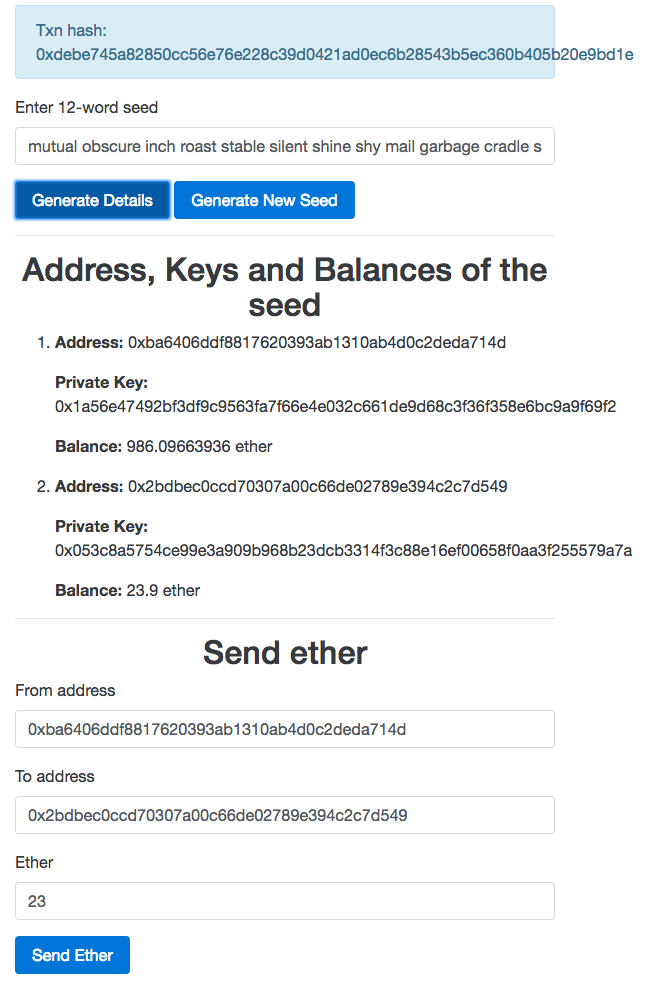

Chapter 26, Building a Wallet Service, explains how to build a wallet service that users can create and manage Ethereum Wallets easily, even offline. We will specifically use the LightWallet library to achieve this.

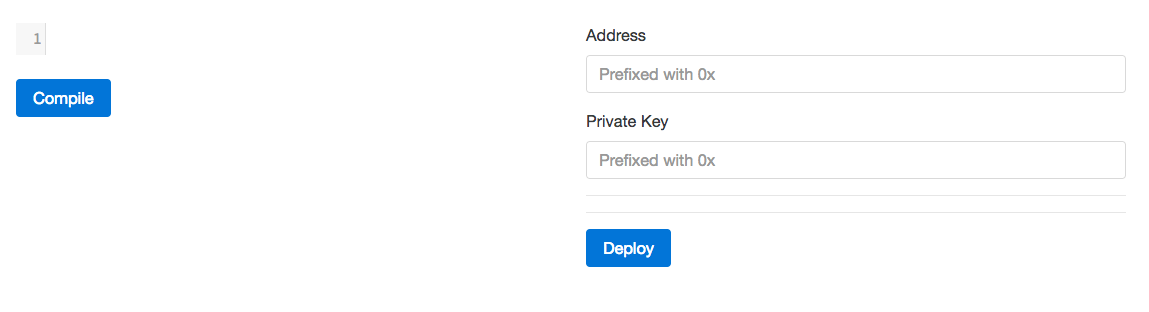

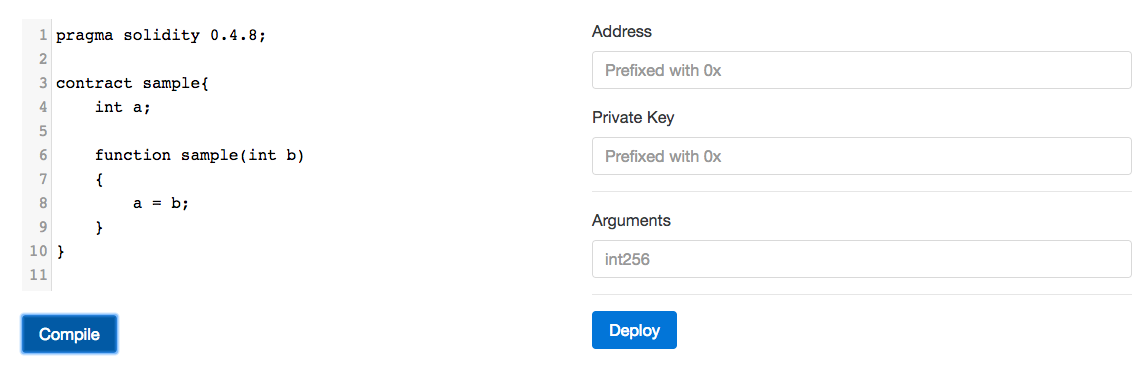

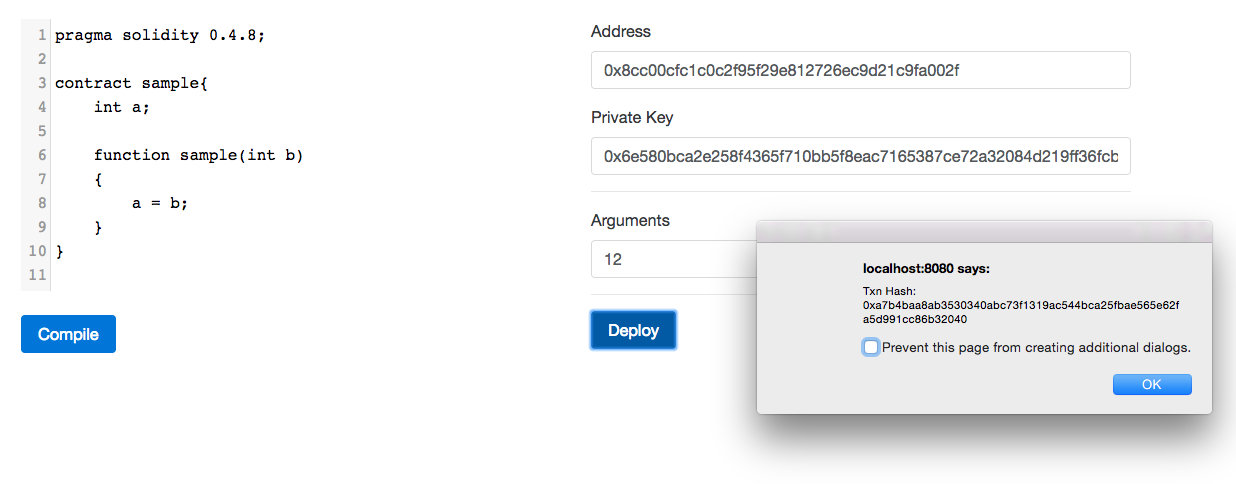

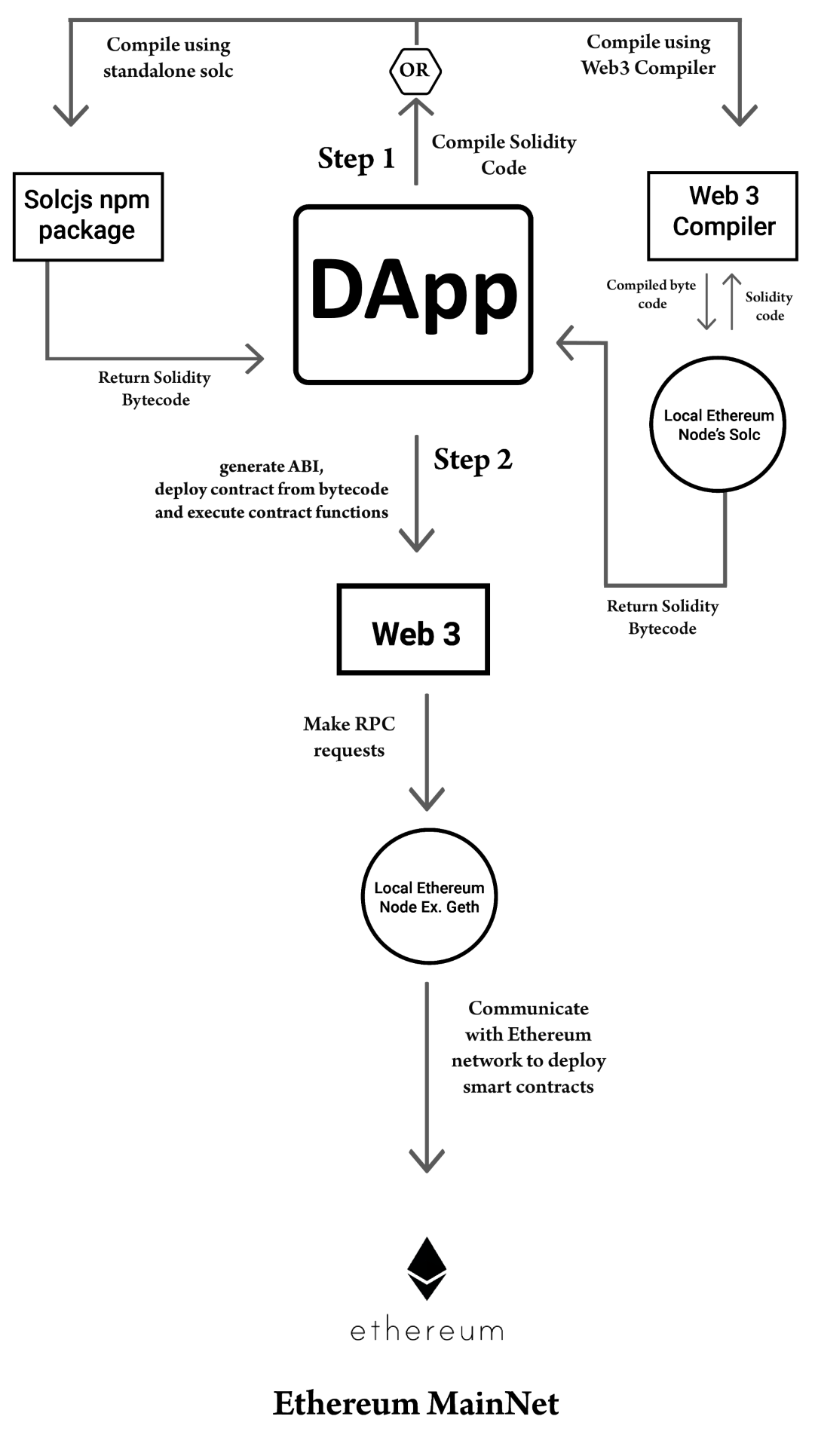

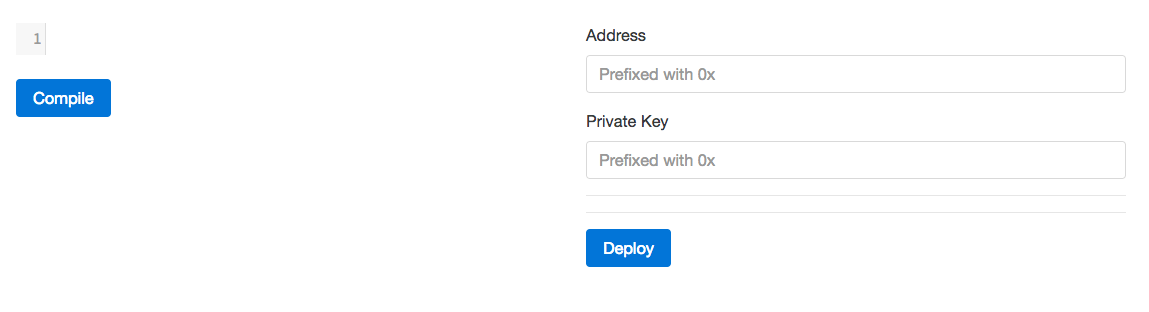

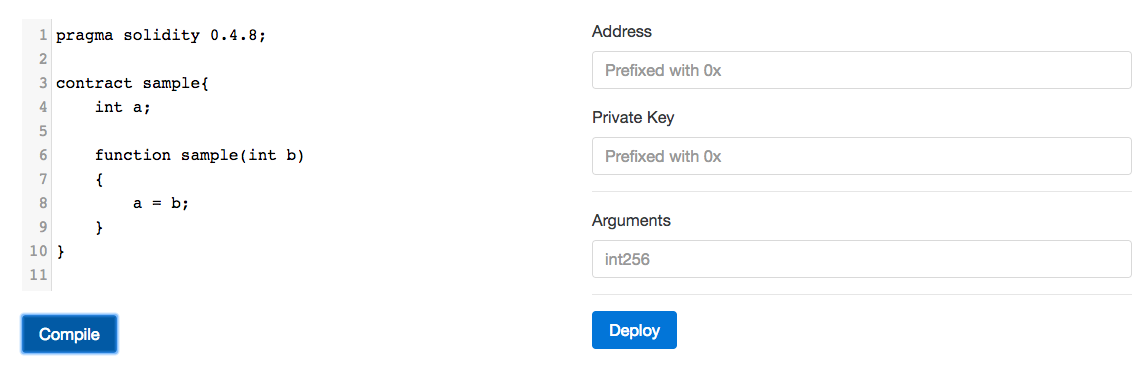

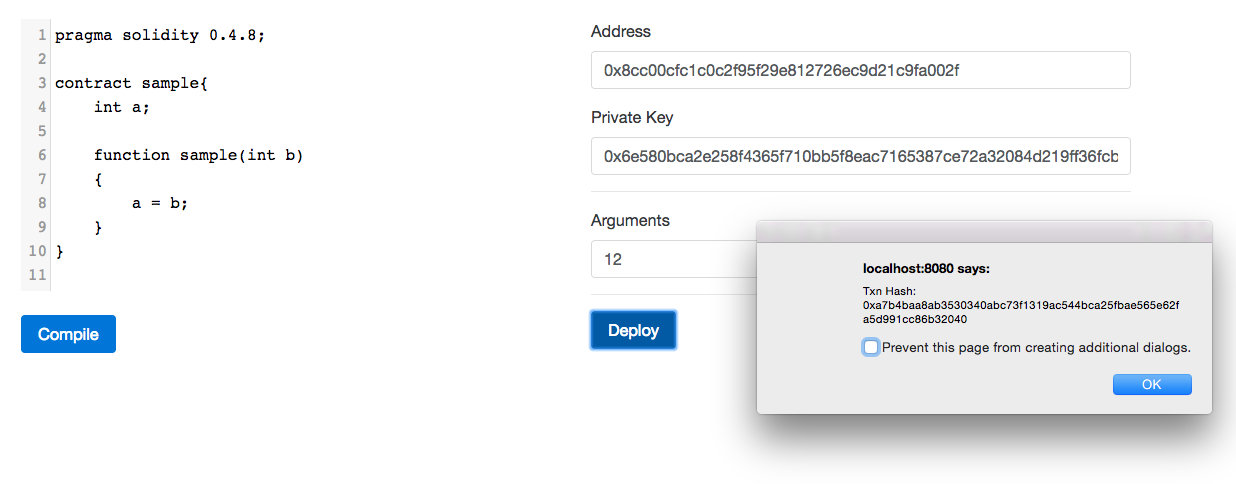

Chapter 27, Building a Smart Contract Deployment Platform, shows how to compile smart contracts using web3.js and deploy it using web3.js and EthereumJS.

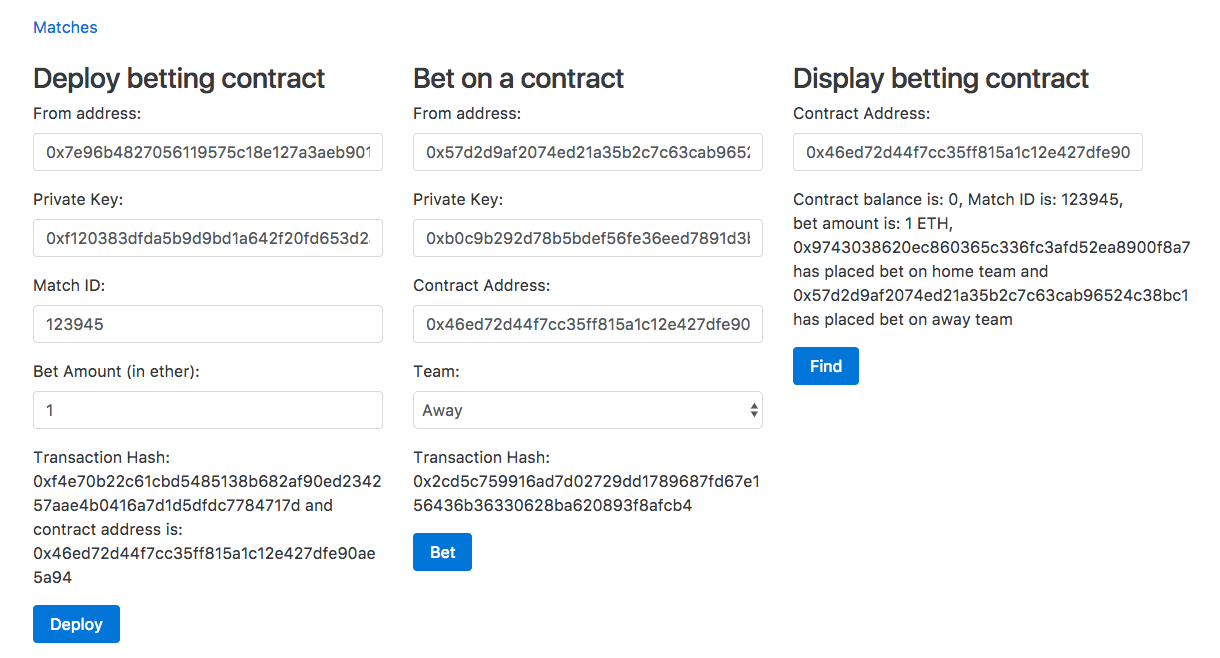

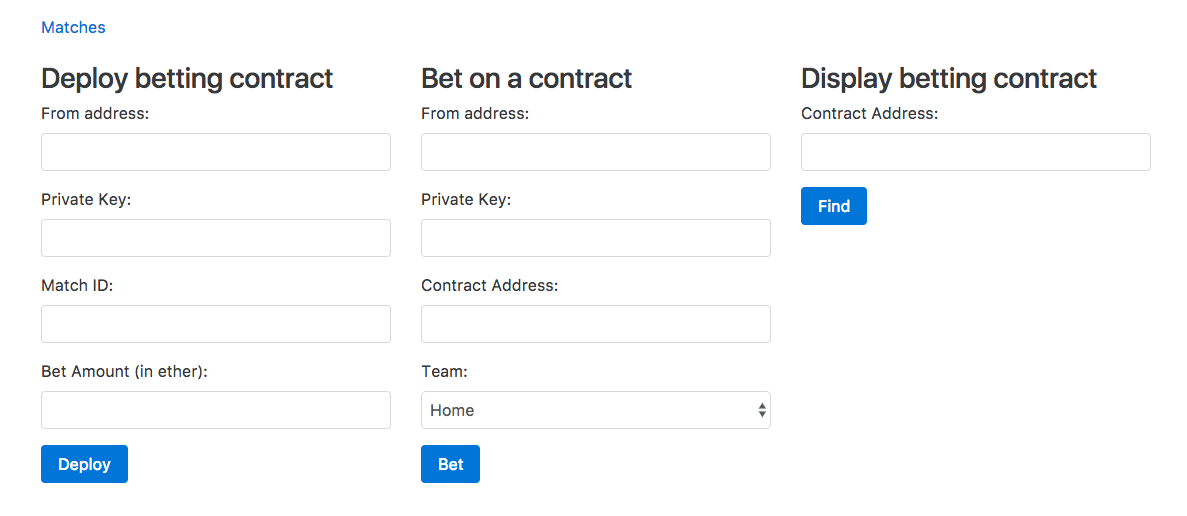

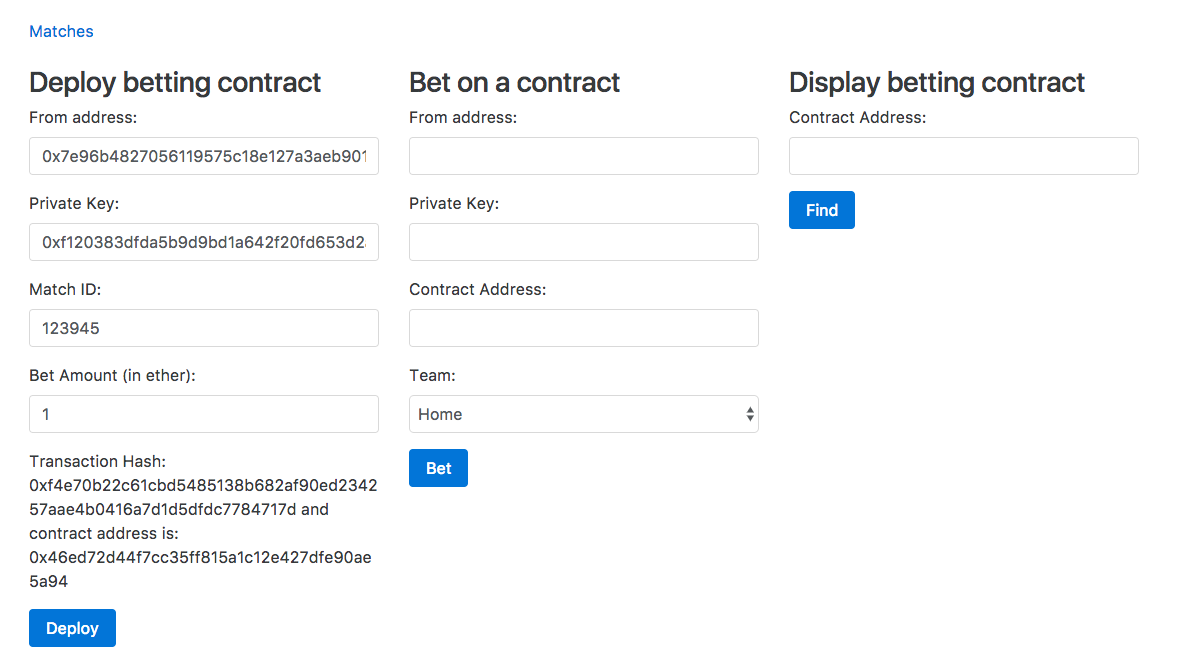

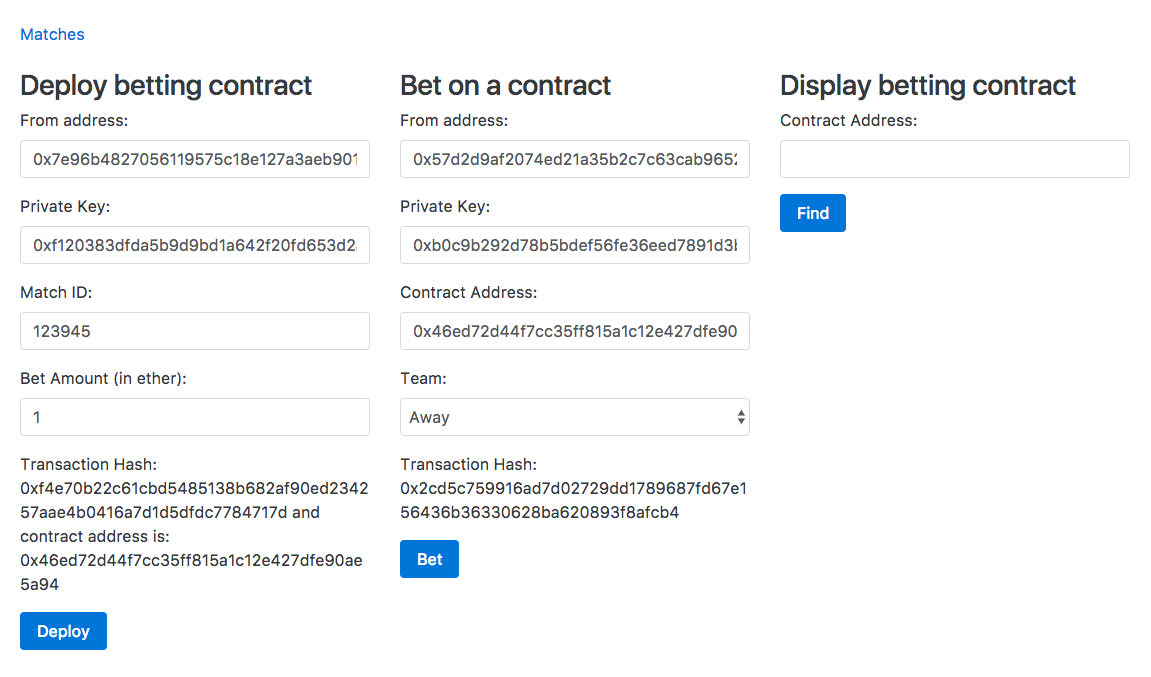

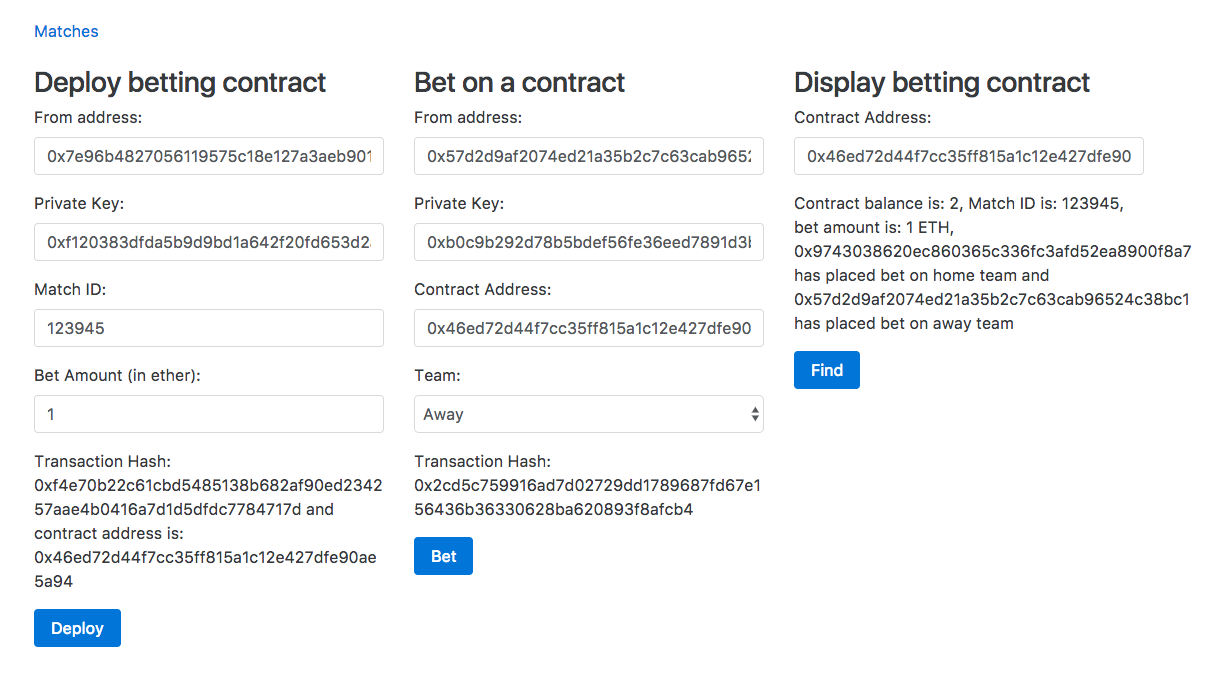

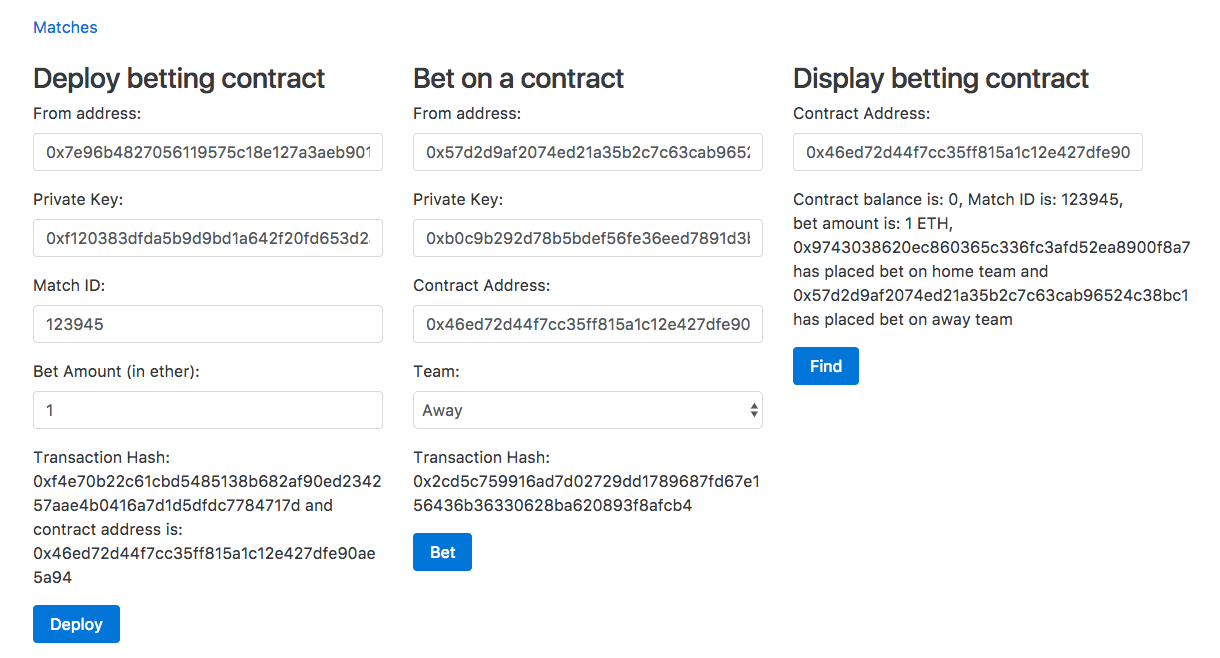

Chapter 28, Building a Betting App, explains how to use Oraclize to make HTTP requests from Ethereum smart contracts to access data from World Wide Web. We will also learn how to access files stored in IPFS, use the strings library to work with strings, and more.

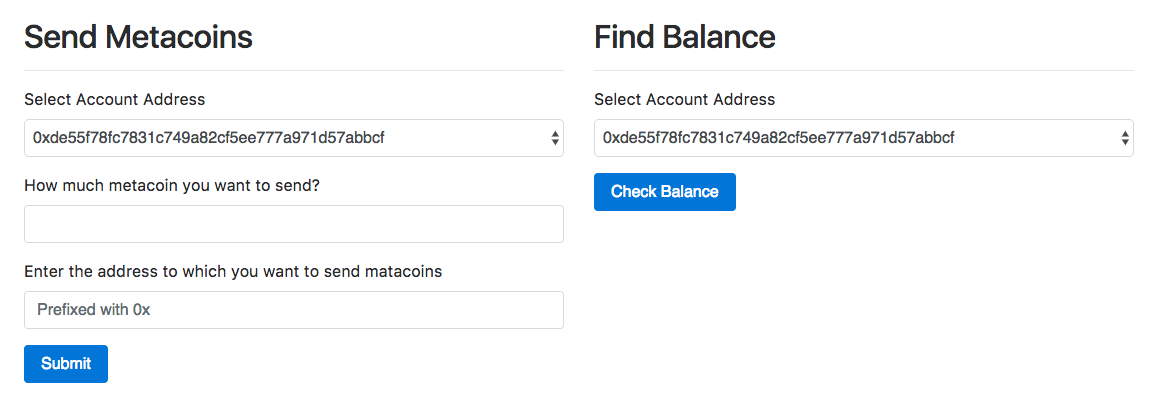

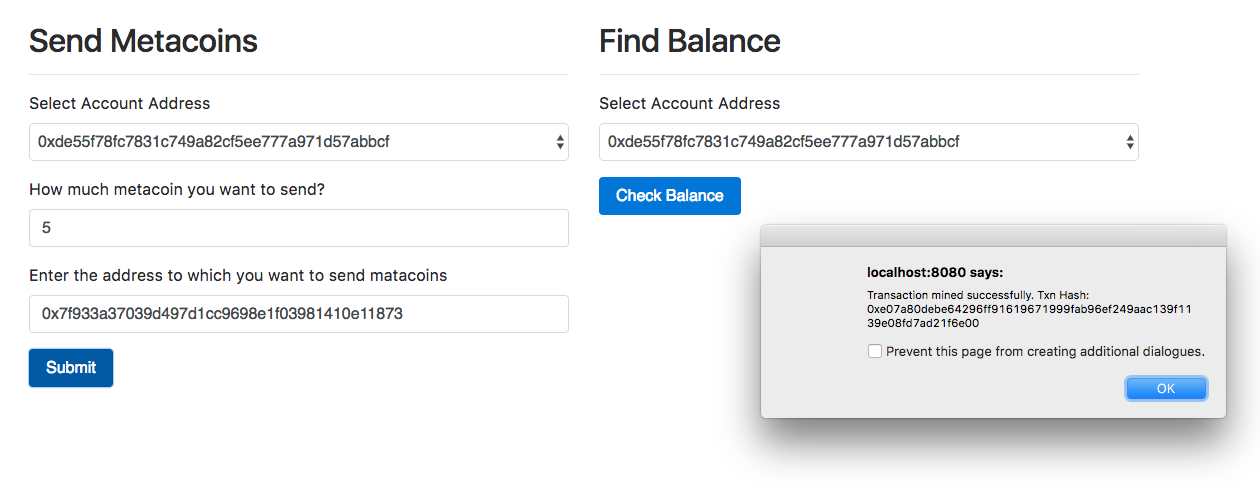

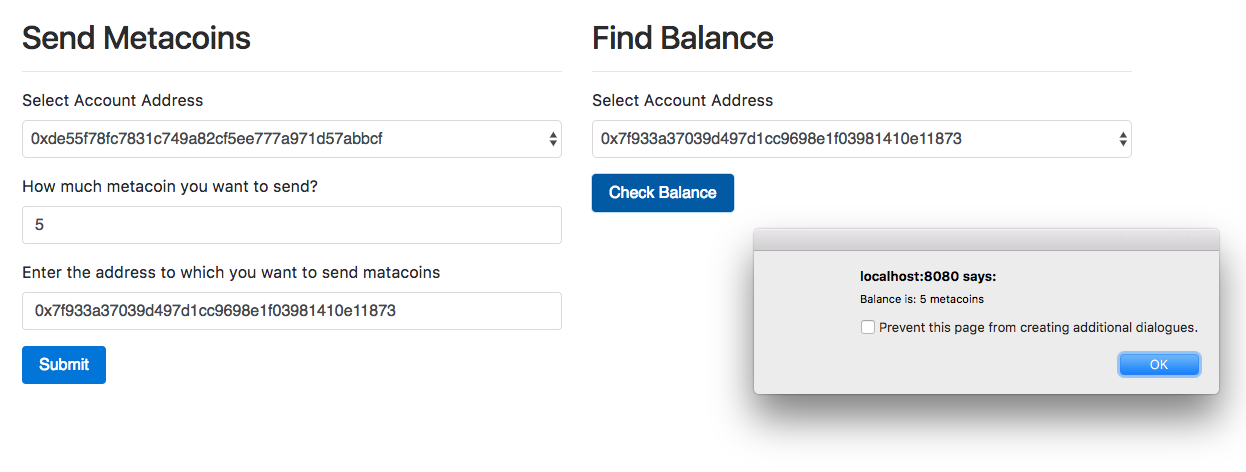

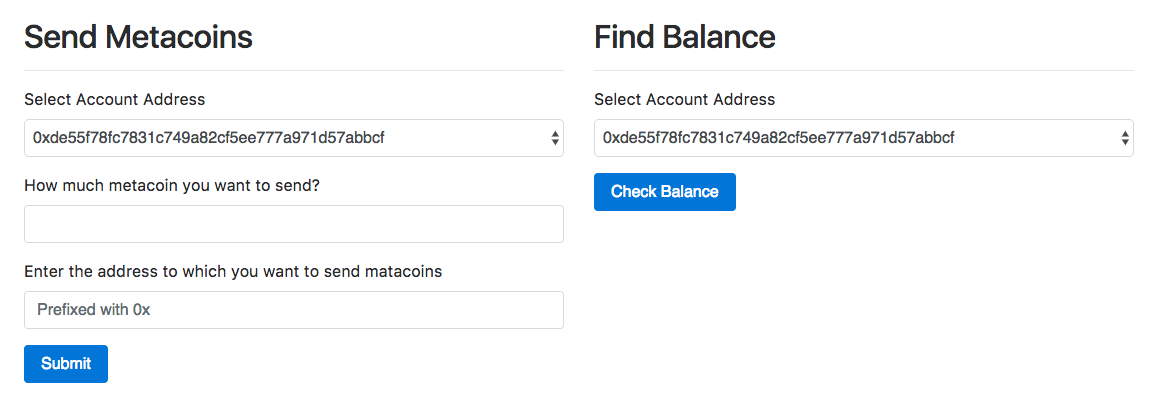

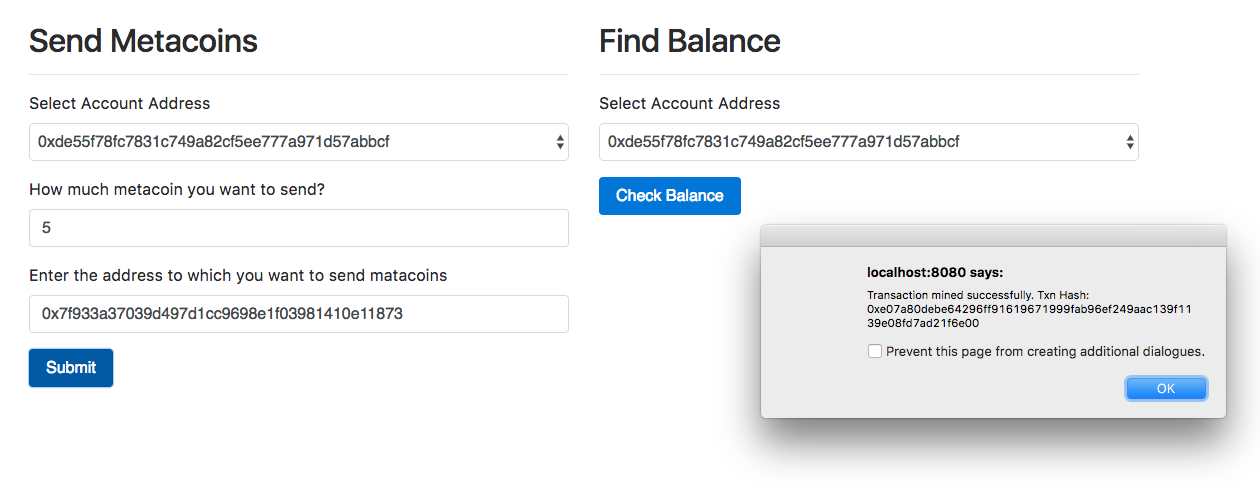

Chapter 29, Building Enterprise Level Smart Contracts, explains how to use Truffle, which makes it easy to build enterprise-level DApps. We will learn about Truffle by building an alt-coin.

Chapter 30, Building a Consortium Blockchain, we will discuss consortium blockchain.

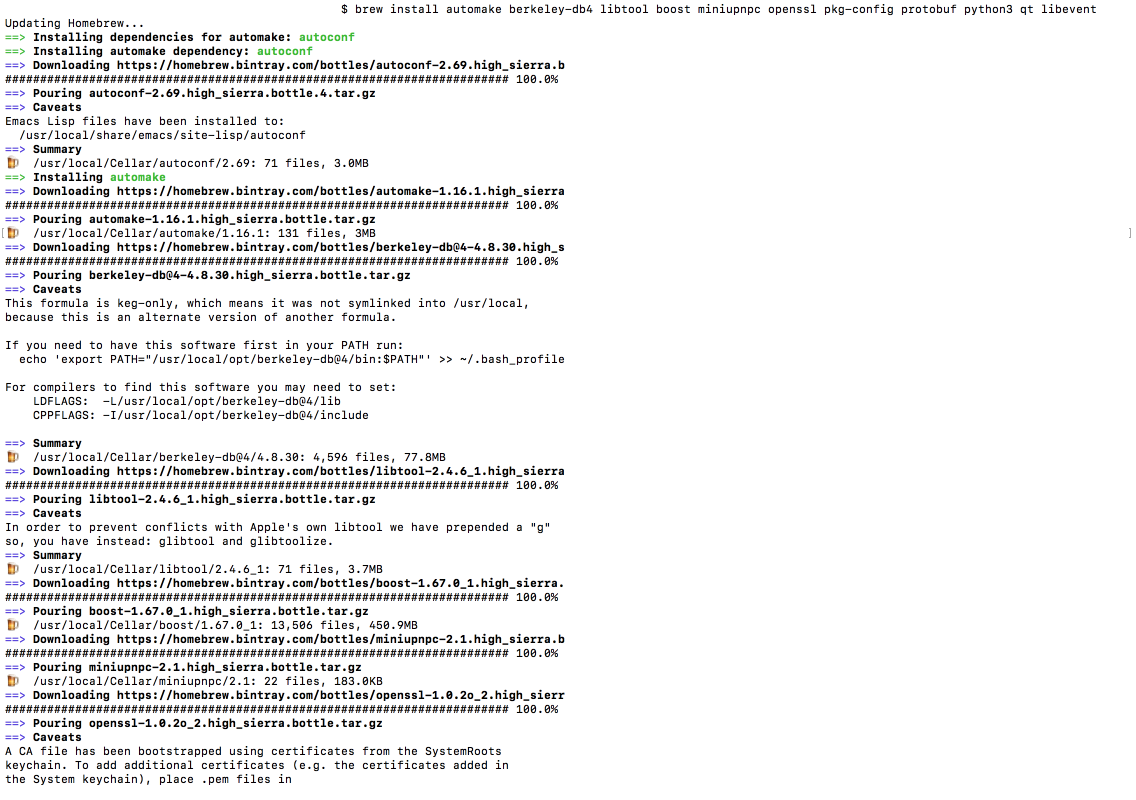

To complete this book successfully, students will require computer systems with at least an Intel Core i5 processor or equivalent, 8 GB RAM, and 35 GB available storage space. Along with this, you would require the following software:

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packt.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packt.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/TrainingByPackt/Blockchain-Developers-Guide. In case there's an update to the code, it will be updated on the existing GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "The WebDriver class provides constructors for each browser."

A block of code is set as follows:

difficulty = difficulty_1_target/current_target difficulty_1_target = 0x00000000FFFF0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

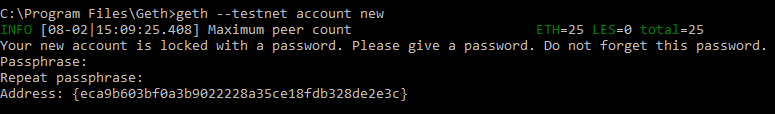

COMMANDS:

list Print summary of existing accounts

new Create a new account

update Update an existing account

import Import a private key into a new account

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "If a user clicks on the Your Account option on the Home Webpage, the application will check whether they have already logged in."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: If you have questions about any aspect of this book, mention the book title in the subject of your message and email us at customercare@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packt.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packt.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packt.com.

Since its inception in 2008, blockchain has been a keen topic of interest for everyone in finance, technology, and other similar industries. Apart from bringing a new overview to record keeping and consensus, blockchain has enormous potential for disruption in most industries. Early adopters, enthusiasts, and now governments and organizations are exploring the uses of blockchain technology.

In this book, we will discuss the basics of financial transactions using fiat money to create our own cryptocurrency based on Ether tokens, and, in so doing, we will try to cover the majority of topics surrounding blockchain. We will be discussing Ethereum-based blockchains, Hyperledger projects, wallets, altcoins, and other exciting topics necessary to understand the functioning and potential of blockchain.

In this chapter, we will discuss the following:

Let's start by discussing each of the preceding listed topics and other important details surrounding them.

Before we dig deeper into blockchain-based transactions, it is helpful to know about how financial transactions actually happen and the functioning of fiat money.

Fiat money is entirely based on the credit of the economy; by definition, it is the money declared legal tender by the government. Fiat money is worthless without a guarantee from the government.

Another type of money is commodity money; it is derived from the commodity out of which the good money is made. For example, if a silver coin is made, the value of the coin would be its value in terms of silver, rather than the defined value of the coin. Commodity money was a convenient form of trade in comparison to the barter system. However, it is prone to huge fluctuations in price.

Commodity money proved to be difficult to carry around, so, instead, governments introduced printed currency, which could be redeemed from the government-based banks for actual commodity, but then, even that proved to be difficult for the government to manage, and it introduced fiat-based currency, or faith-based currency.

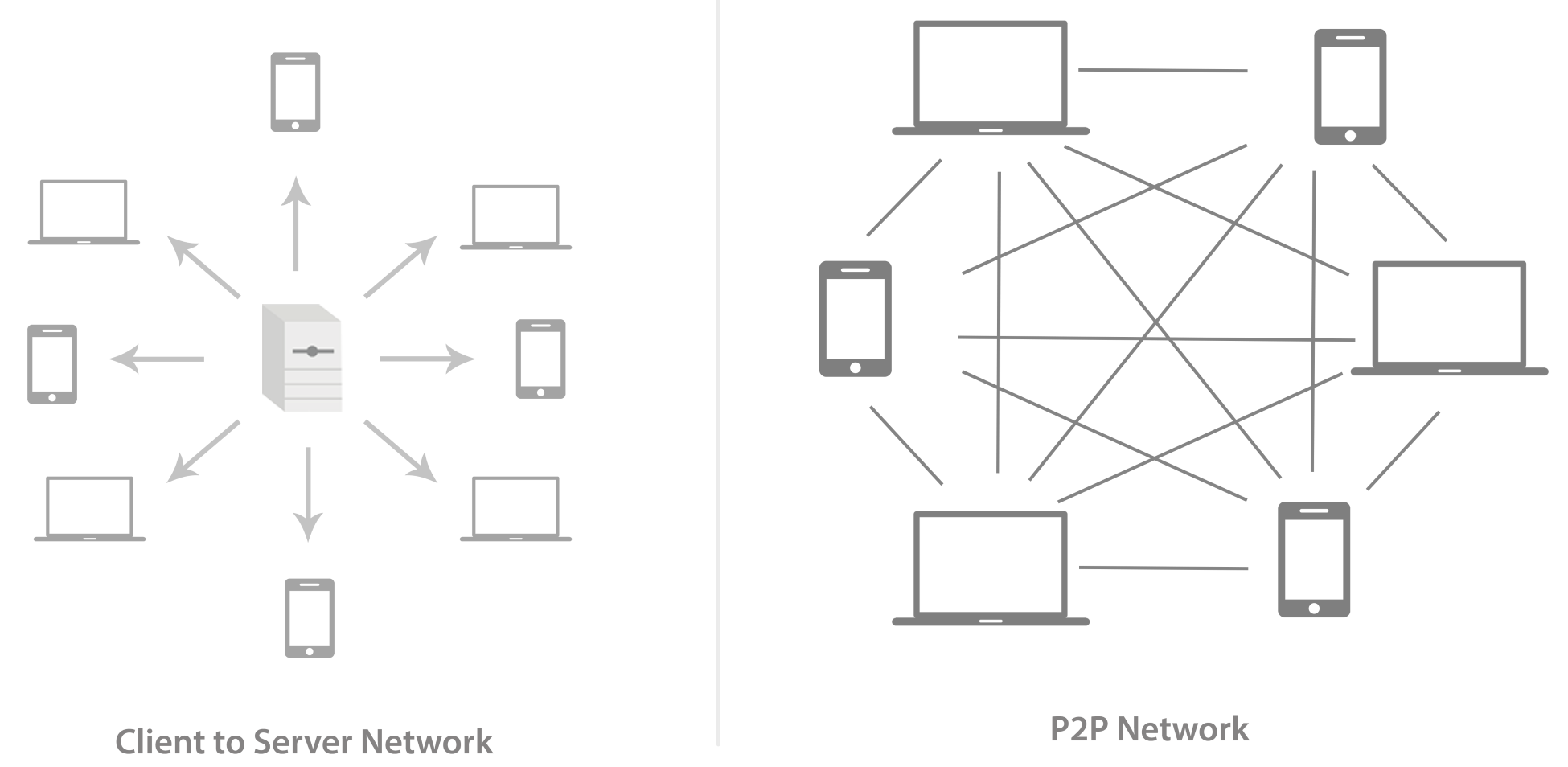

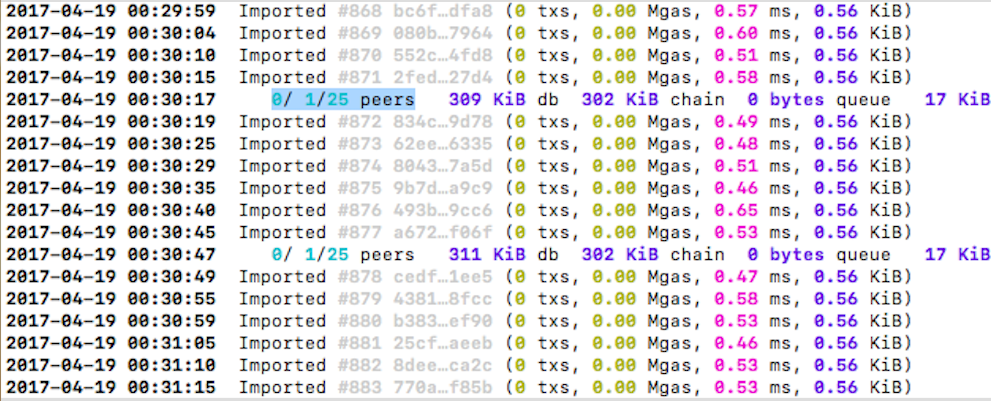

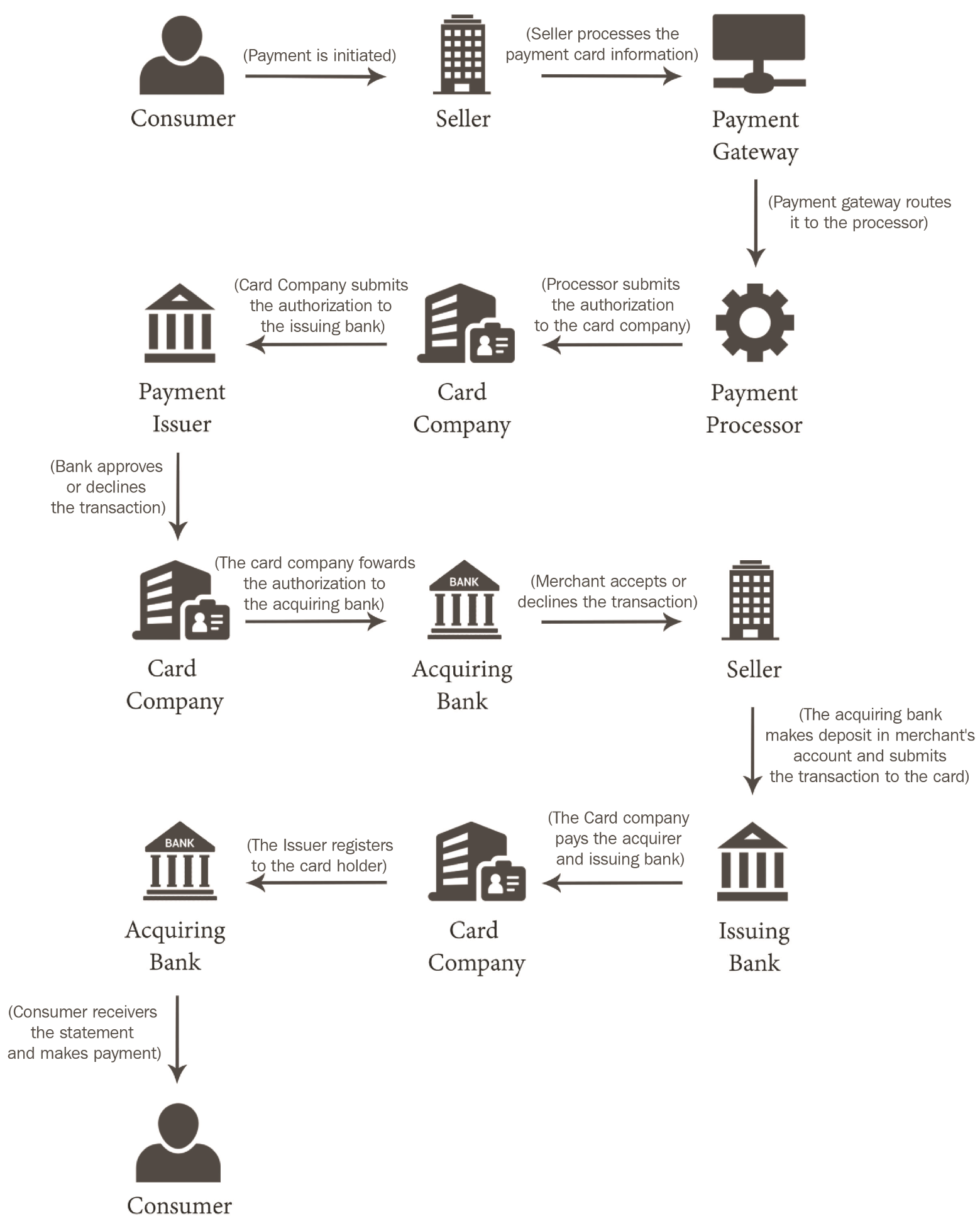

Having fiat-based currencies incurred a lot of third-party consensus during its time; this would help eradicate fraud from the system. It is also necessary to have a stringent consensus process to make sure that the process, as well as the privacy, is maintained within the system. The following diagram depicts the process of a credit card-based payment process:

A ledger is a record for economic transactions that includes cash, accounts receivable, inventory, fixed assets, accounts payable, accrued expenses, debt, equity, revenue, costs, salaries, wages, expenses, depreciation, and so on. In short, the book in which accounts are maintained is called a ledger. It is the primary record used by banks and other financial institutions to reconcile book balances. All the debits and credits during an accounting period are calculated to make the ledger balance.

The financial statements of banks, financial institutions, and enterprises are compiled using ledger accounts.

While doing a financial transaction using fiat currency, we have a third-party ledger that maintains information about every transaction. Some of these third-party trust systems are VISA, MasterCard, banks, and so on.

Blockchain has changed the landscape of this trustless system by making everyone part of the ledger. Hence, it is sometimes even called a distributed ledger; everybody doing a transaction in blockchain has a record of other transactions that have happened or are happening in the blockchain-based Bitcoin system. This decentralized ledger gives multiple authenticity points for every transaction that has happened; plus, the rules are pre-defined and not different for each wallet user.

On a further note, blockchain does not actually eliminate trust; what it does is minimize the amount of trust and distributes it evenly across the network. A specific protocol is defined using various rules that automatically encourage patrons on the basis of the rules followed. We will be discussing this in depth in later chapters.

The whitepaper released by Bitcoin's founder or a group of founders called Satoshi Nakamoto, in 2008, described Bitcoin as a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash. Blockchain was introduced along with Bitcoin. During the initial stages, blockchain was only used with Bitcoin for Bitcoin-based financial transactions.

Blockchain not only restricts financial transactions in Bitcoin, but in general any transaction between two parties that is maintained by the open, decentralized ledger. Most importantly, this underlying technology can be separated and can have other applications create a surge in the number of experiments and projects surrounding the same.

Numerous projects inspired by blockchain started, such as Ethereum, Hyperledger, and so on, along with currencies such as Litecoin, Namecoin, Swiftcoin, and so on.

Blockchain at its core is a distributed and decentralized open ledger that is cryptographically managed and updated various consensus protocols and agreements among its peers. People can exchange values using transactions without any third party being involved, and the power of maintaining the ledger is distributed among all the participants of the blockchain or the node of the blockchain, making it a truly distributed and decentralized system.

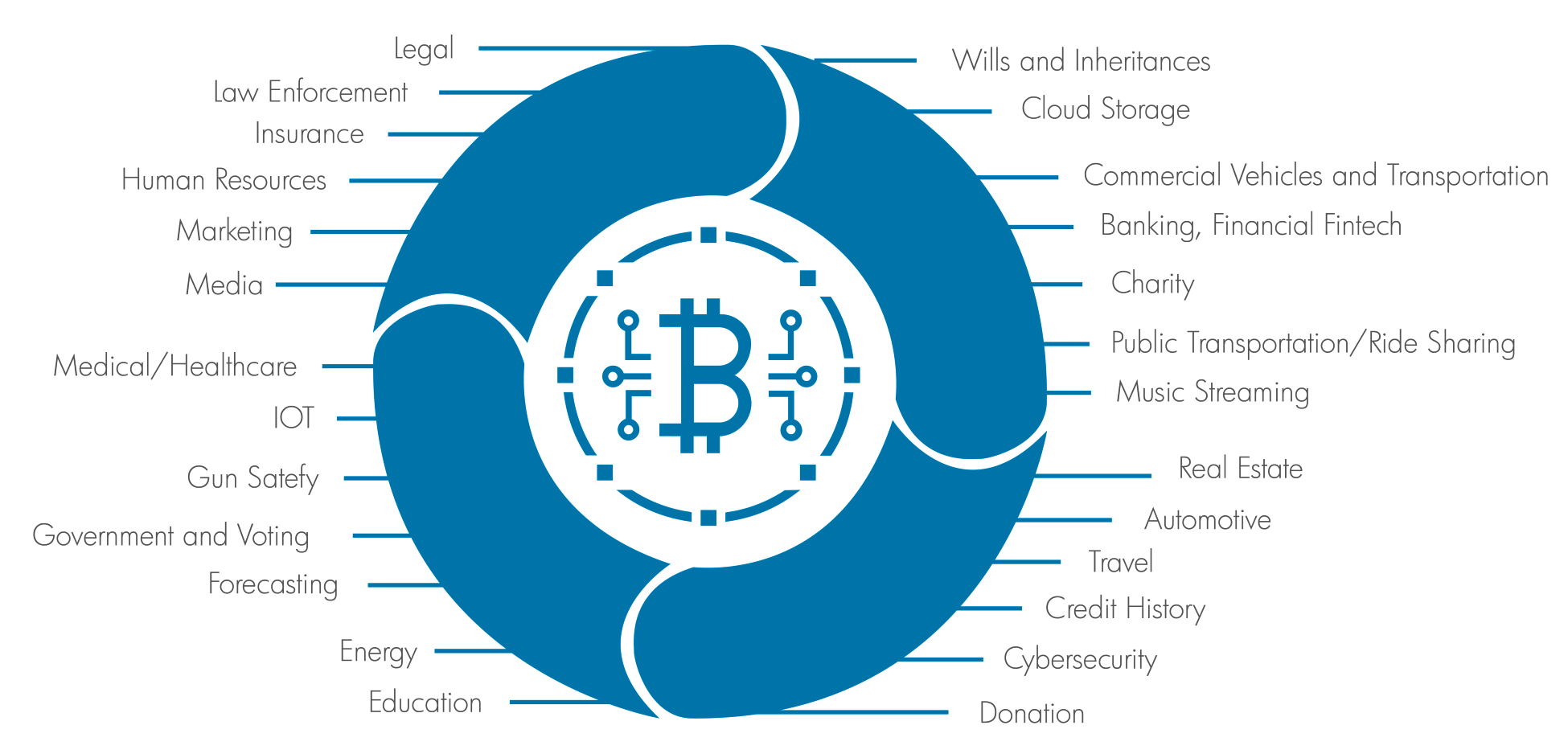

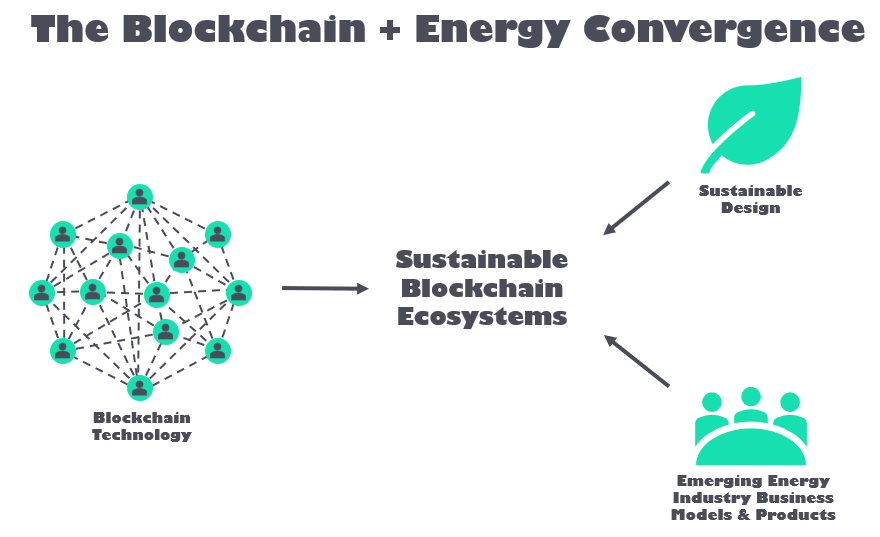

Some of the industry verticals using blockchain are as follows:

Furthermore, we will be discussing various other elements of blockchain and what other problems blockchain can solve.

It is time to discuss the general elements of blockchain, starting from its basic structure to its formation and further details on the same.

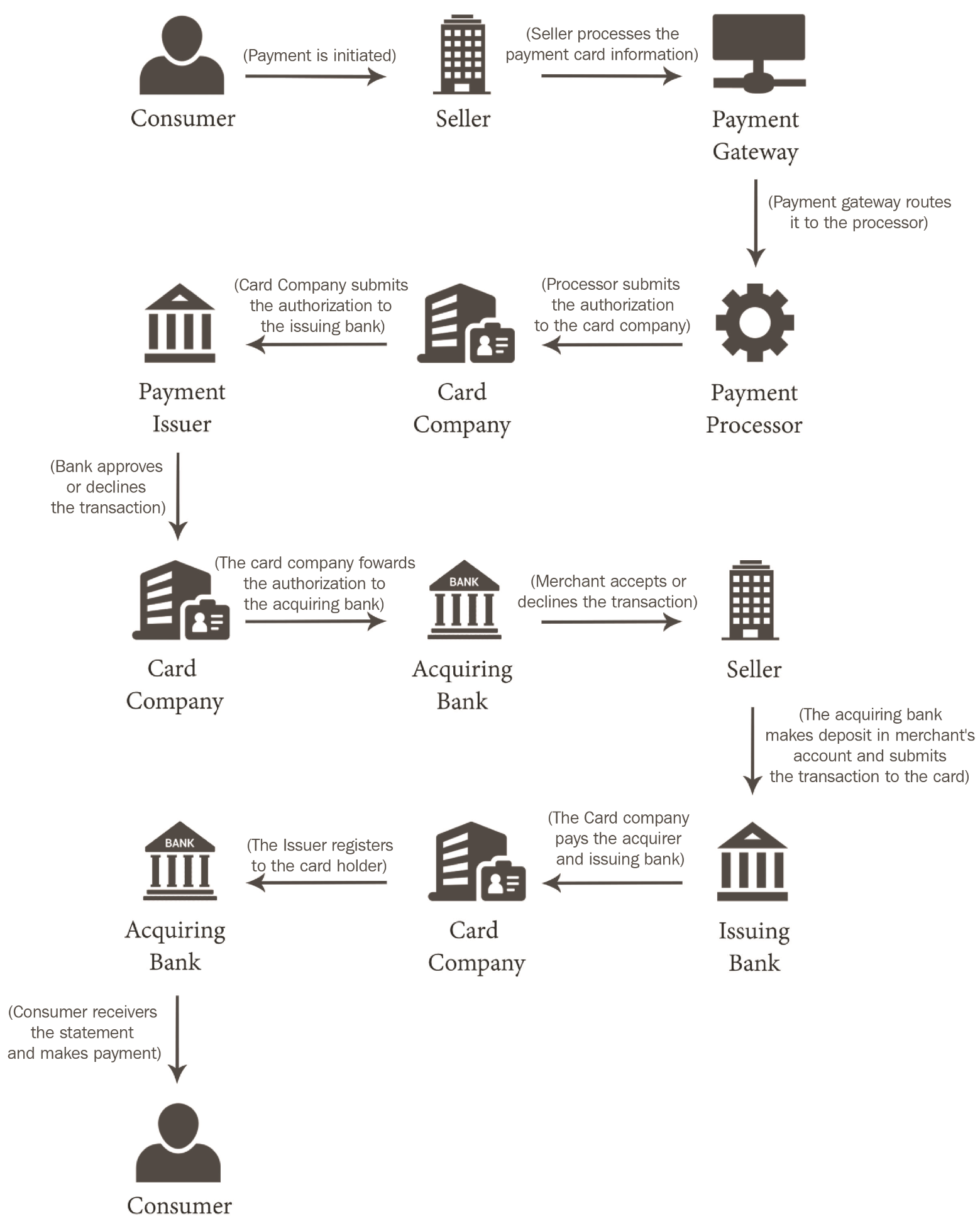

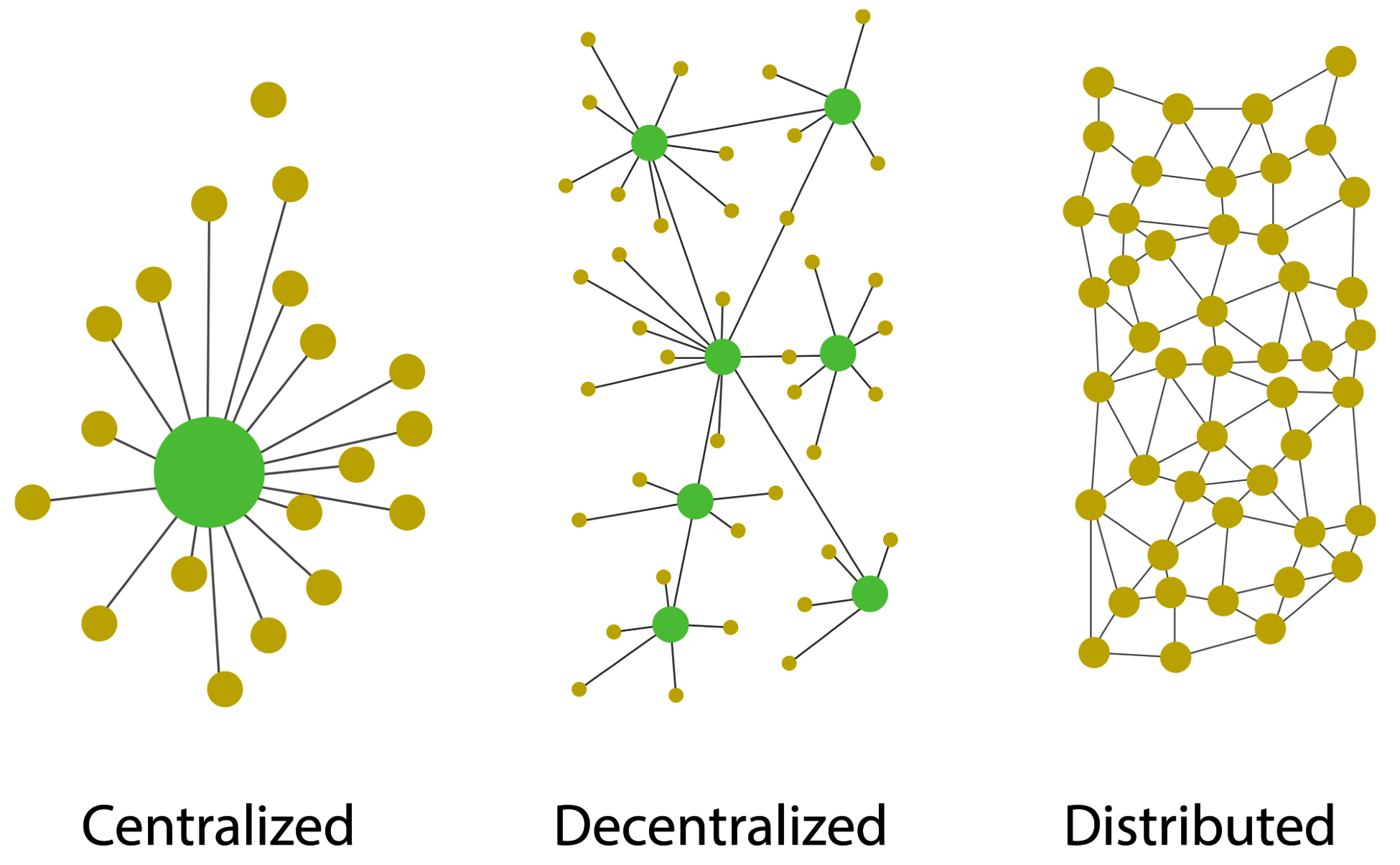

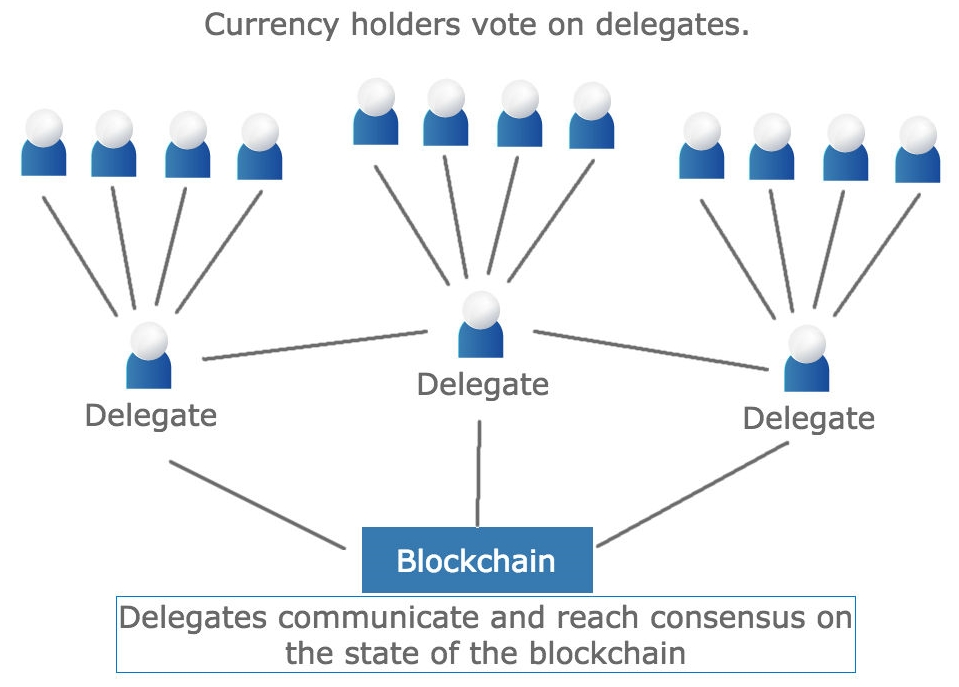

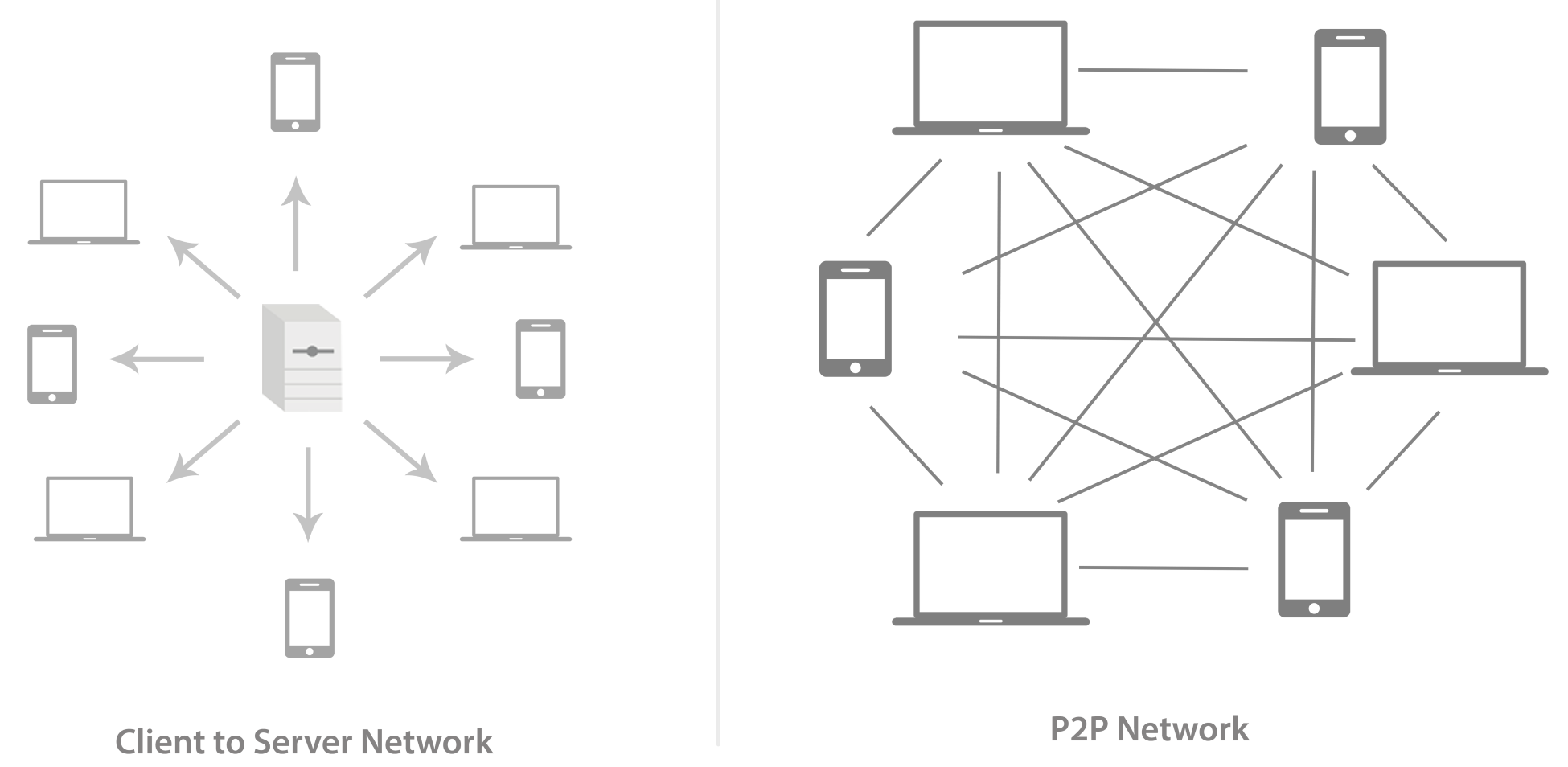

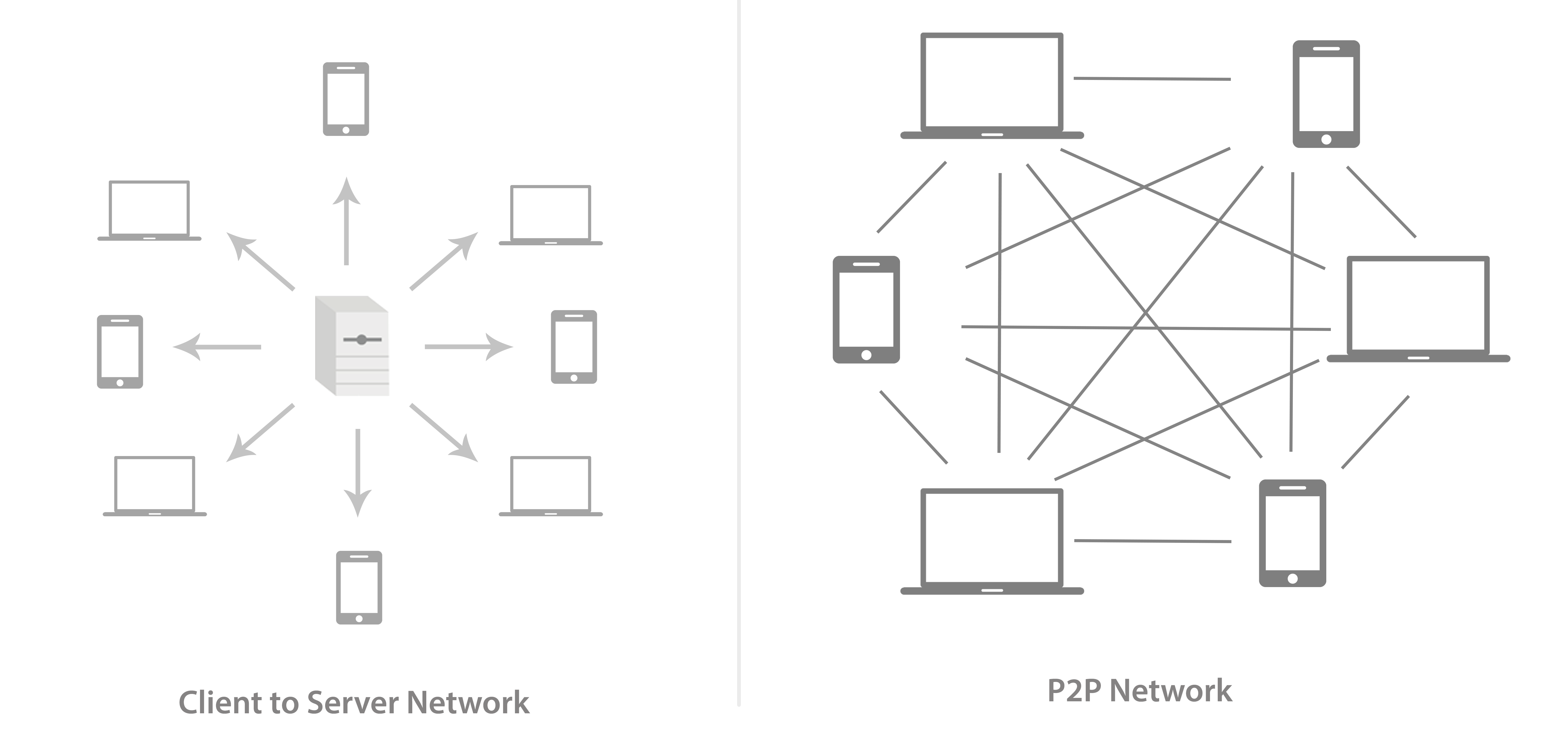

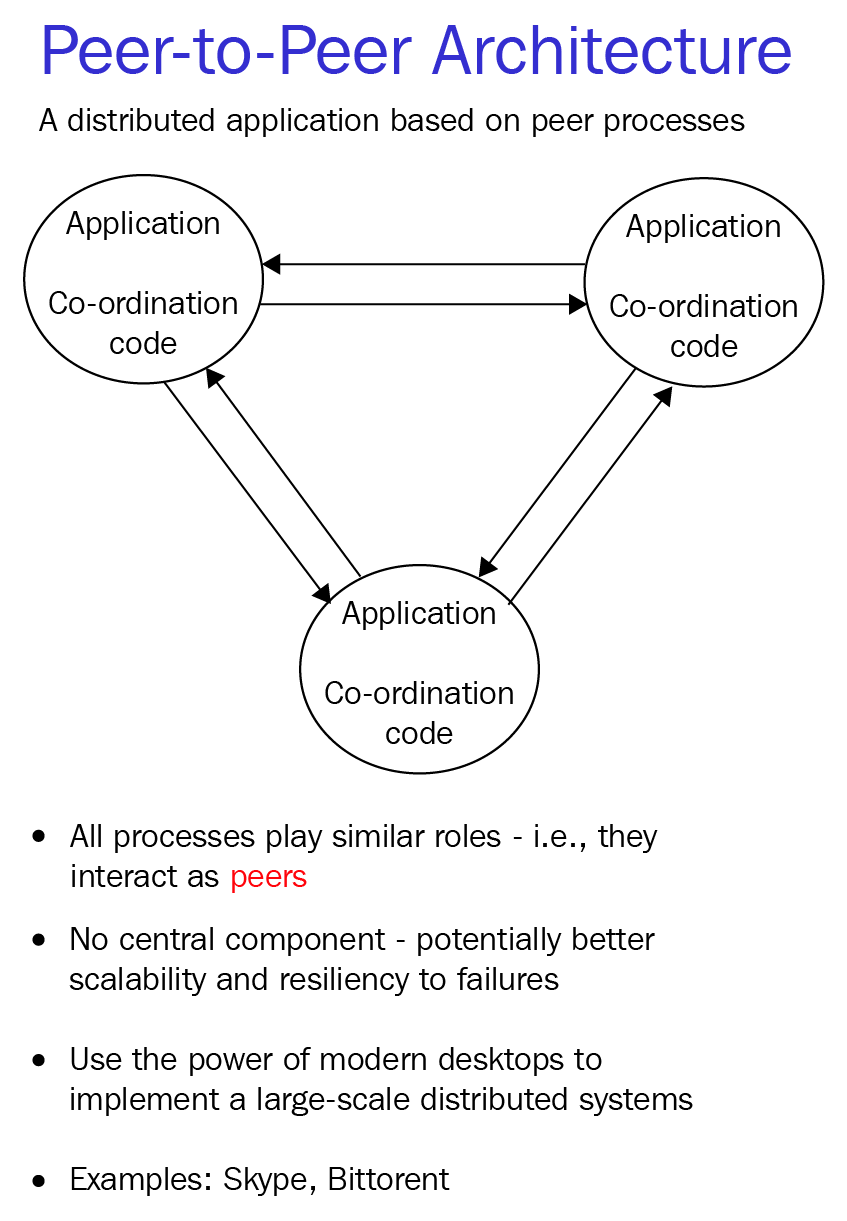

This is a type of network whereby all peers can communicate with one another and are equally entitled, without the need for central coordination by servers or hosts. In conventional networks, the systems are connected to a central server, and this server acts as a central point for communication among the systems. On the other hand, in a peer-to-peer network, all the systems are connected to one another evenly, with no system having central authority. Look at this diagram:

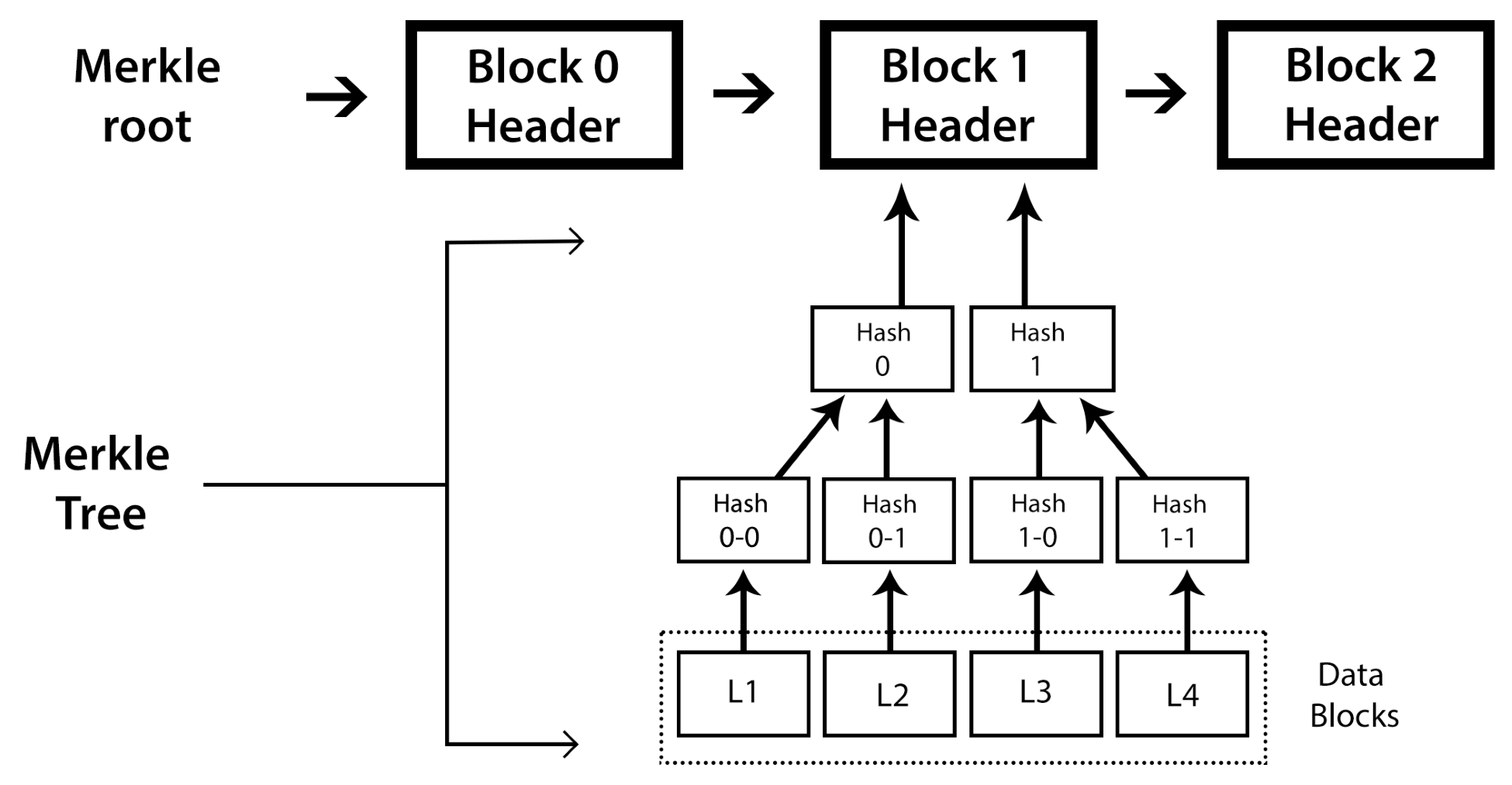

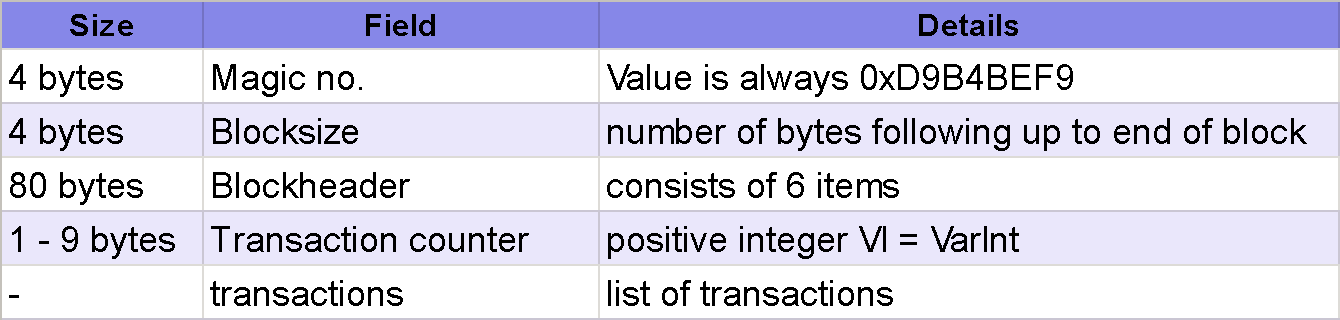

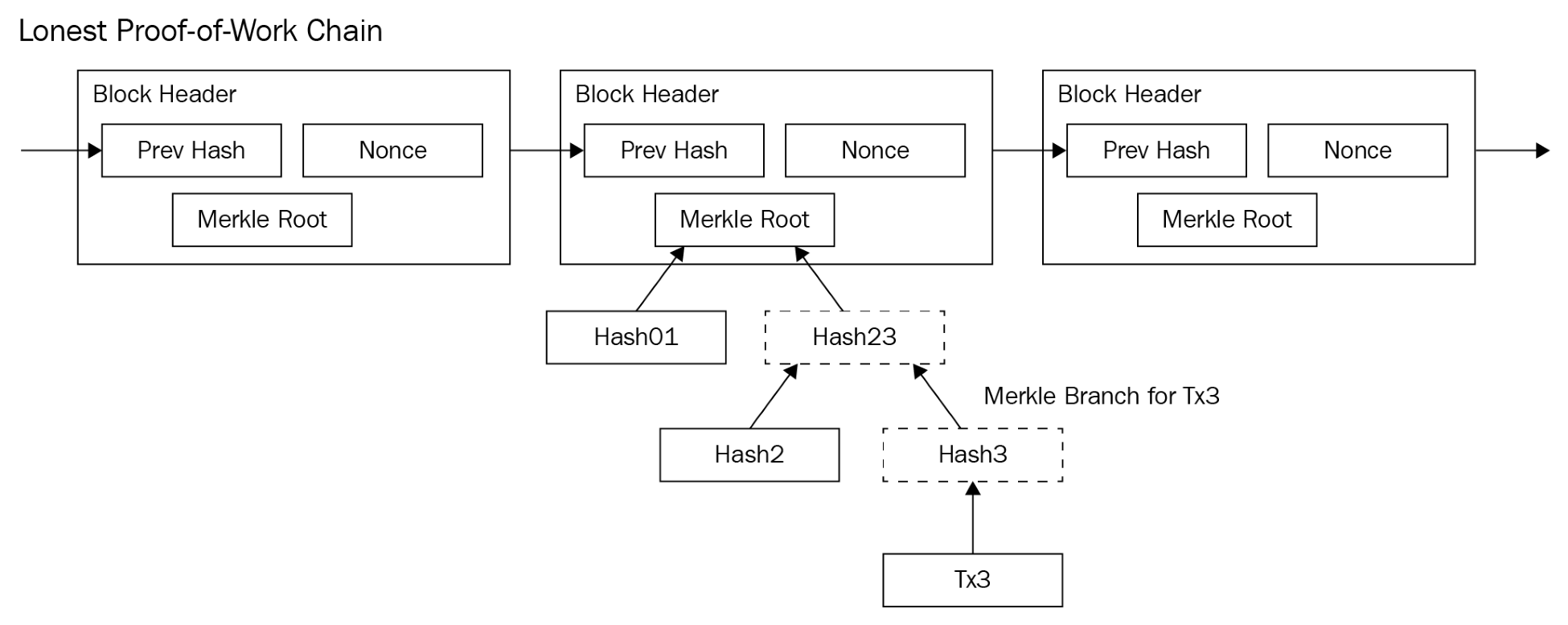

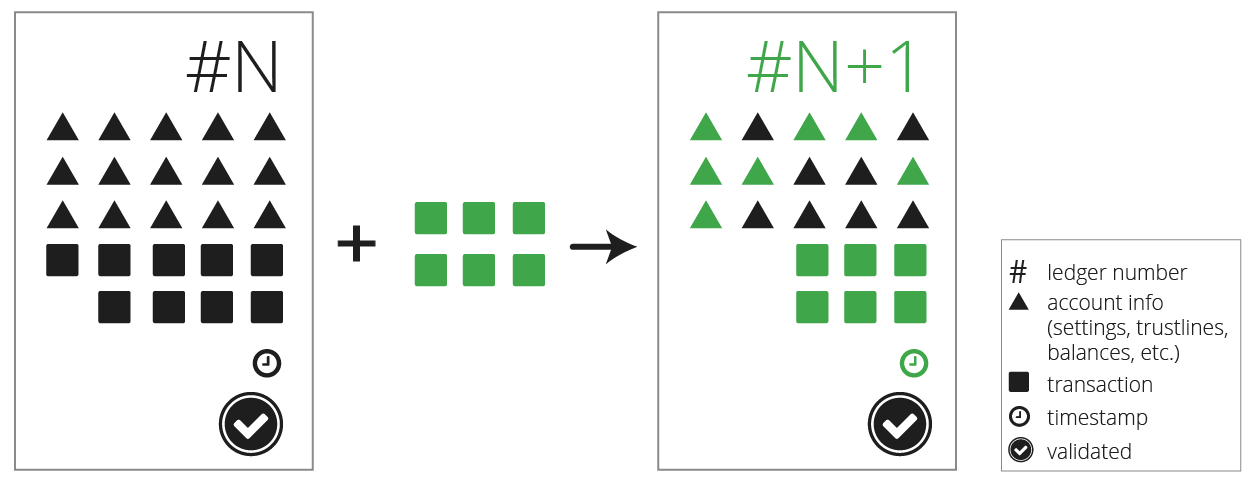

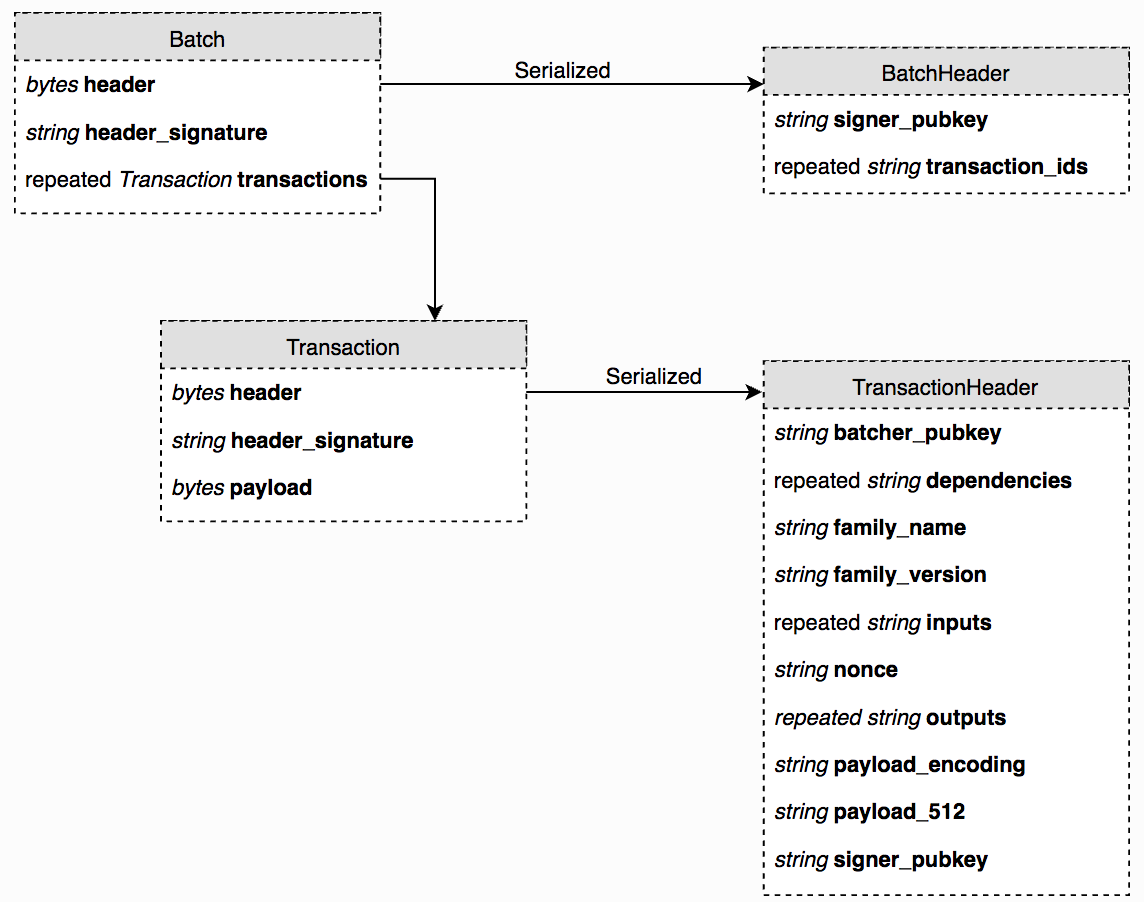

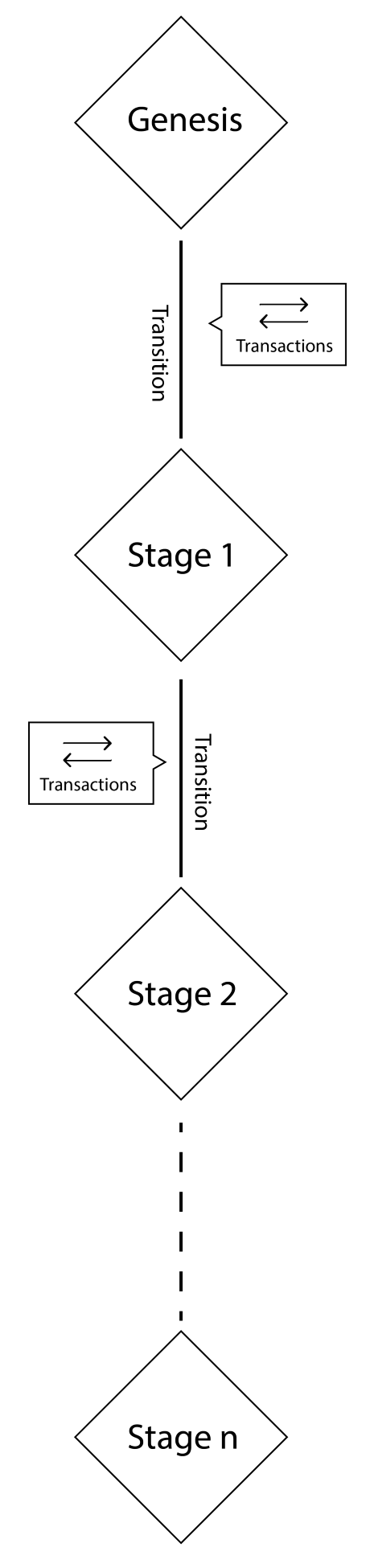

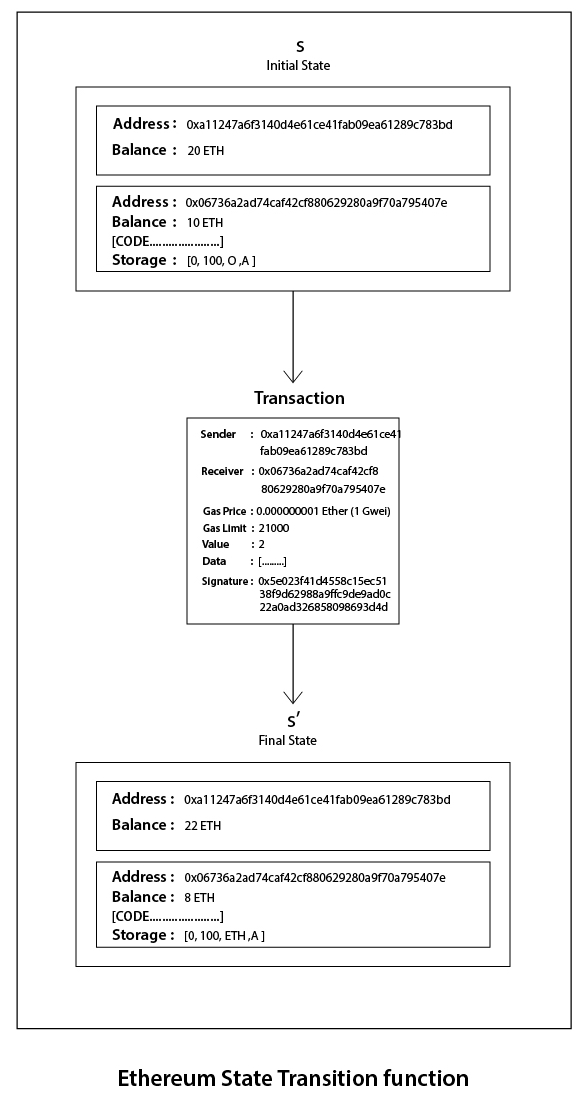

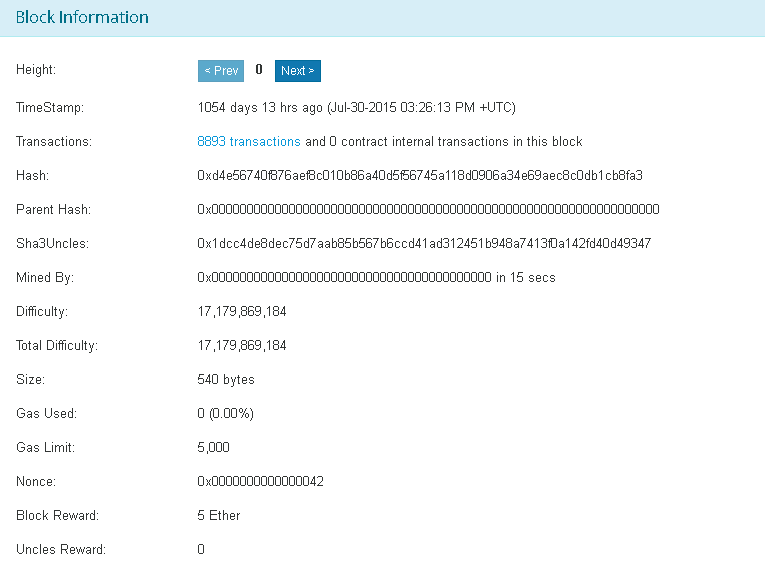

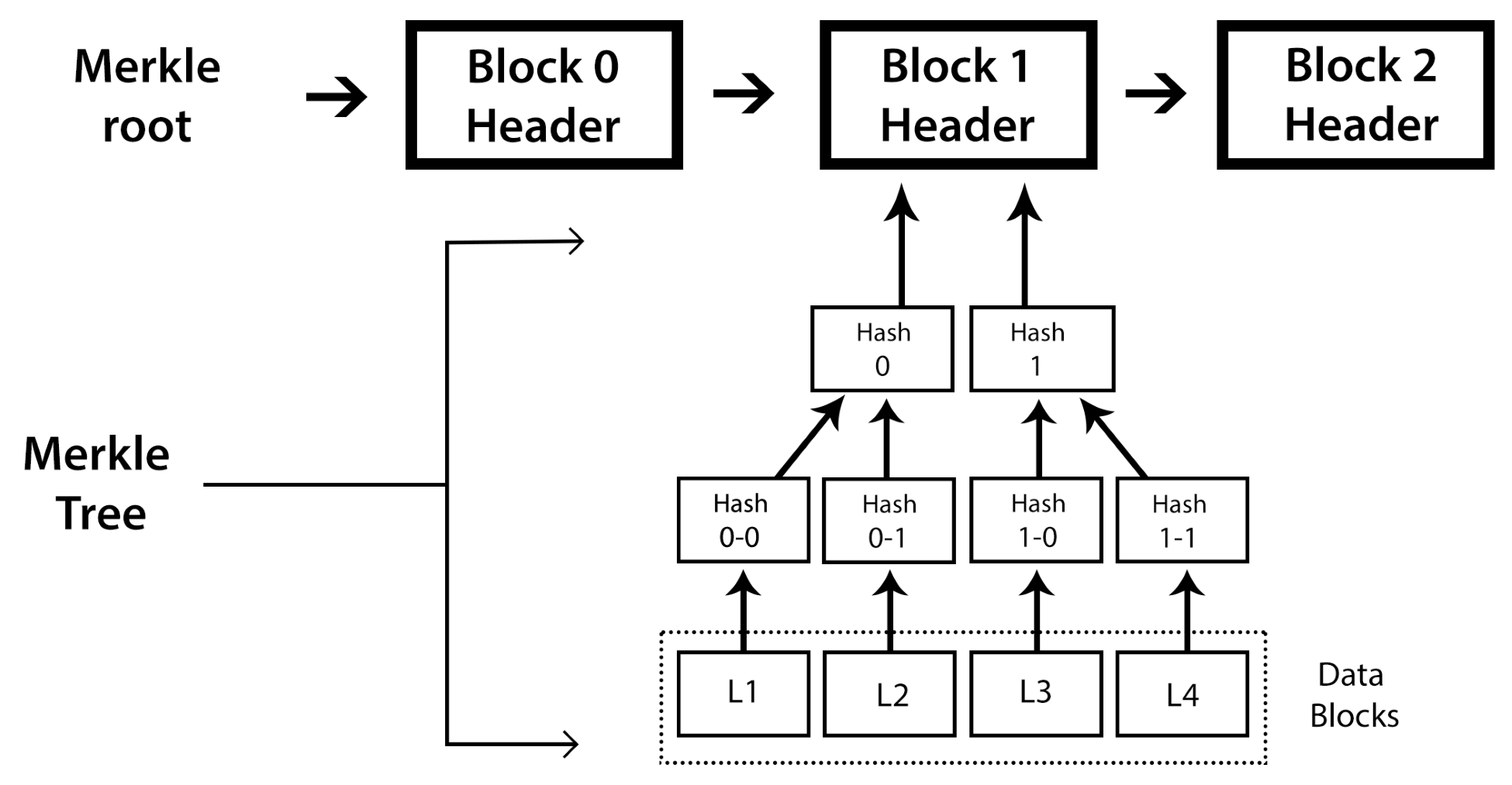

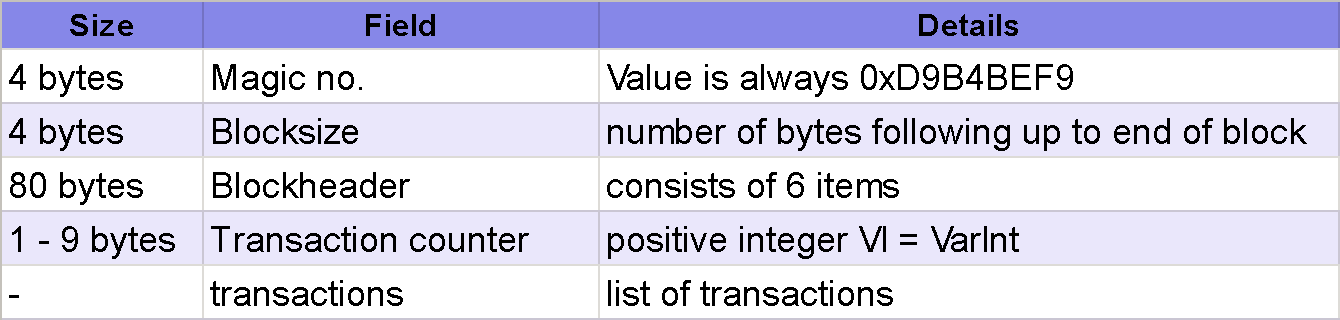

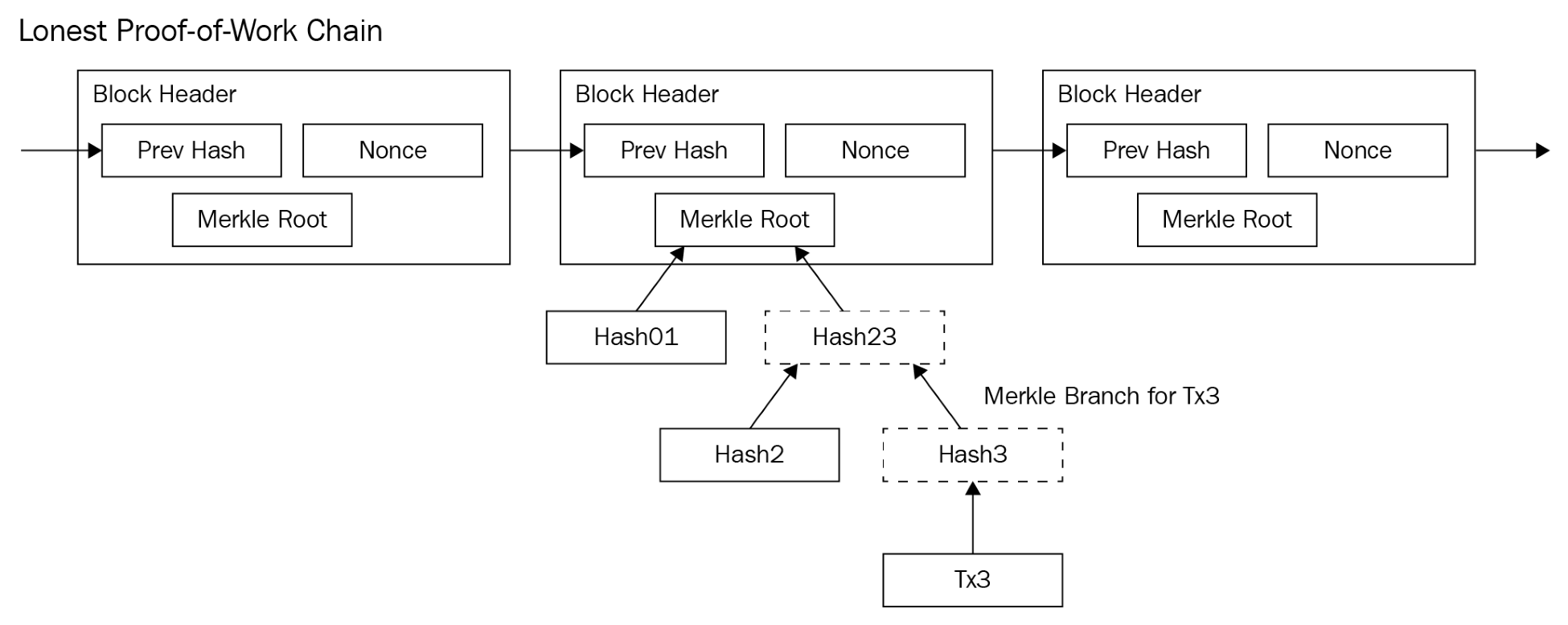

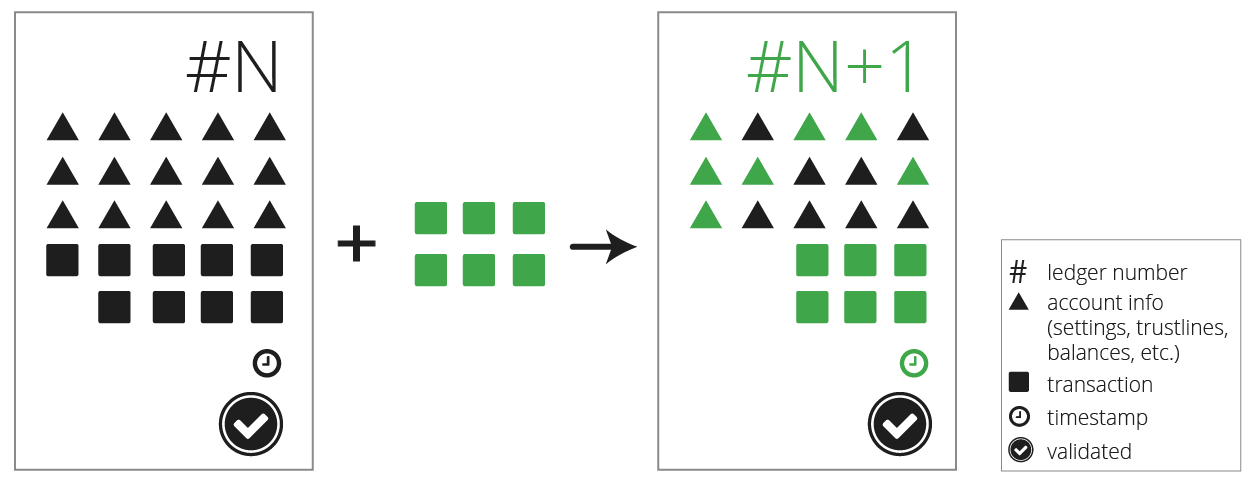

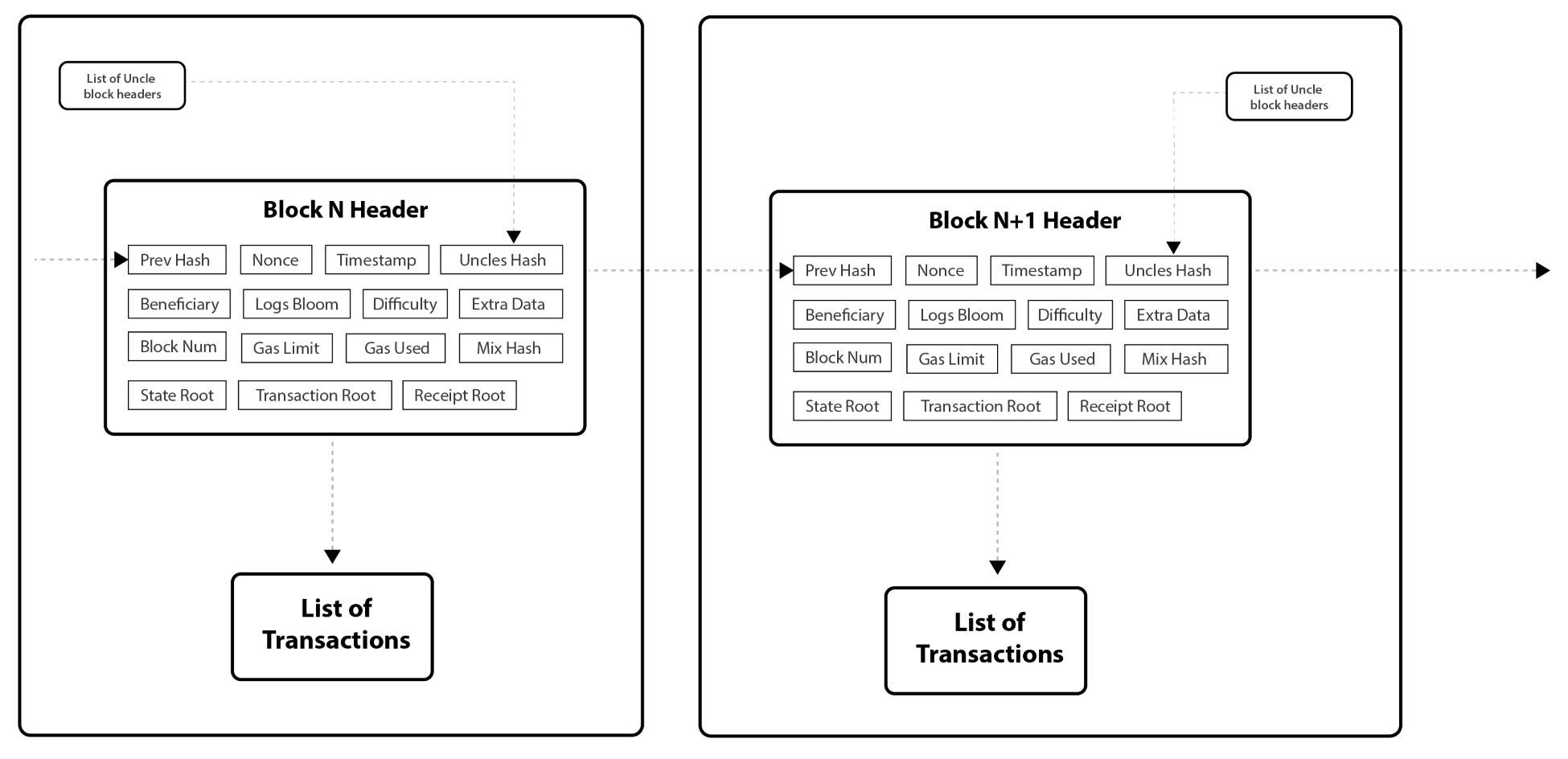

A block is the smallest element of a blockchain; the first block is called the genesis block. Each block contains batches of hashed and encoded transactions. The blocks are stored in a Merkle tree formation. Every block includes the hash of the previous block in the chain that links all blocks to one another. In Bitcoin, a block contains more than 500 transactions on average. The average size of a block is around 1 MB. A block is comprised of a header and a list of transactions.

The block header of a block in Bitcoin comprises of metadata about the block. Consider the following:

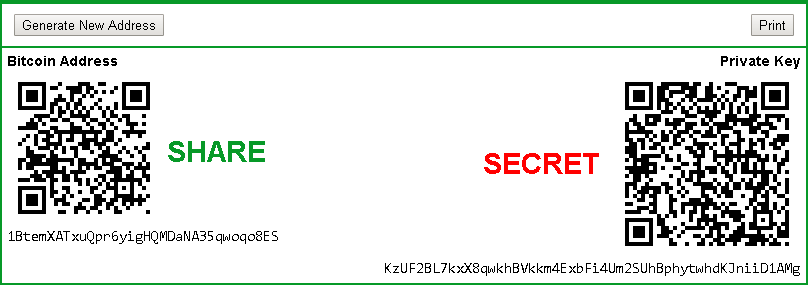

Addresses are unique identifiers that are used in a transaction on the blockchain to send data to another address; in the case of Bitcoins, addresses are identifiers that are used to send or receive Bitcoins. Bitcoin blockchain addresses have evolved from time to time. Originally, IP addresses were used as the Bitcoin address, but this method was prone to serious security flaws; hence, it was decided to use P2PKH as a standard format. A P2PKH address consists of 34 characters, and its first character is integer 1. In literal terms, P2PKH means Pay to Public Key Has. This is an example of a Bitcoin address based on P2PKH: 1PNjry6F8p7eaKjjUEJiLuCzabRyGeJXxg.

Now, there is another advanced Bitcoin protocol to create a P2SH address, which means Pay to Script Hash. One major difference with a P2SH address is that it always starts with integer 3 instead of 1.

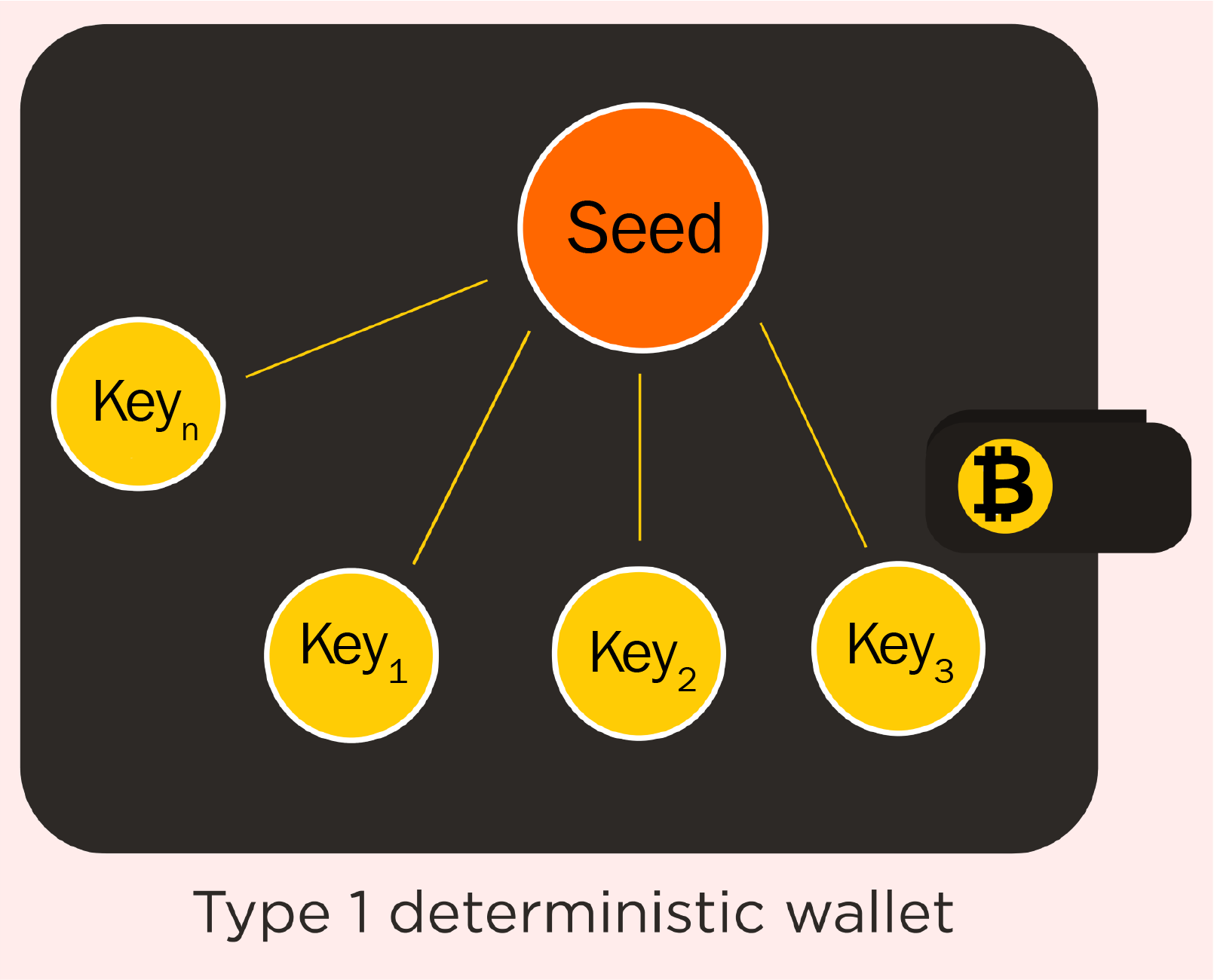

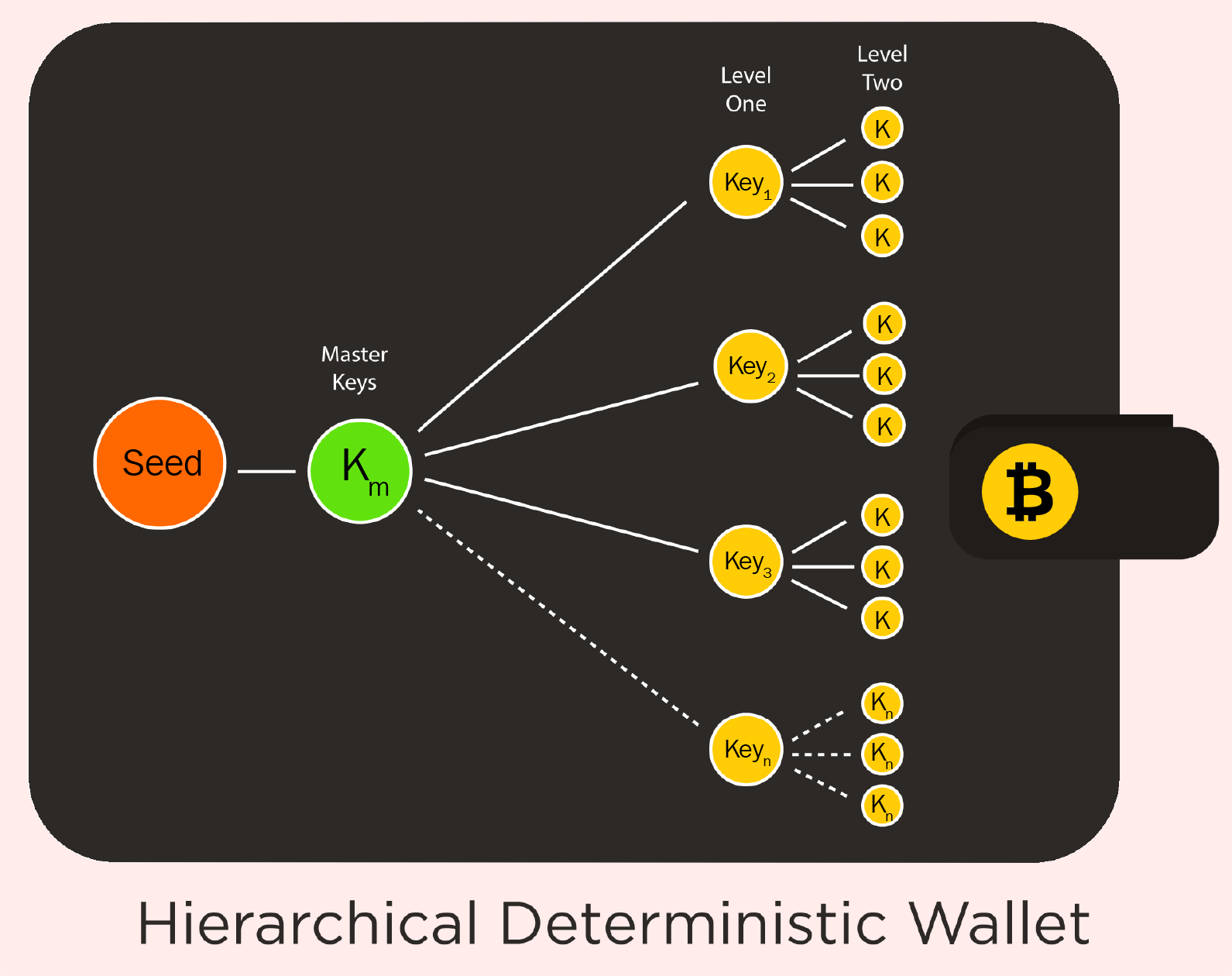

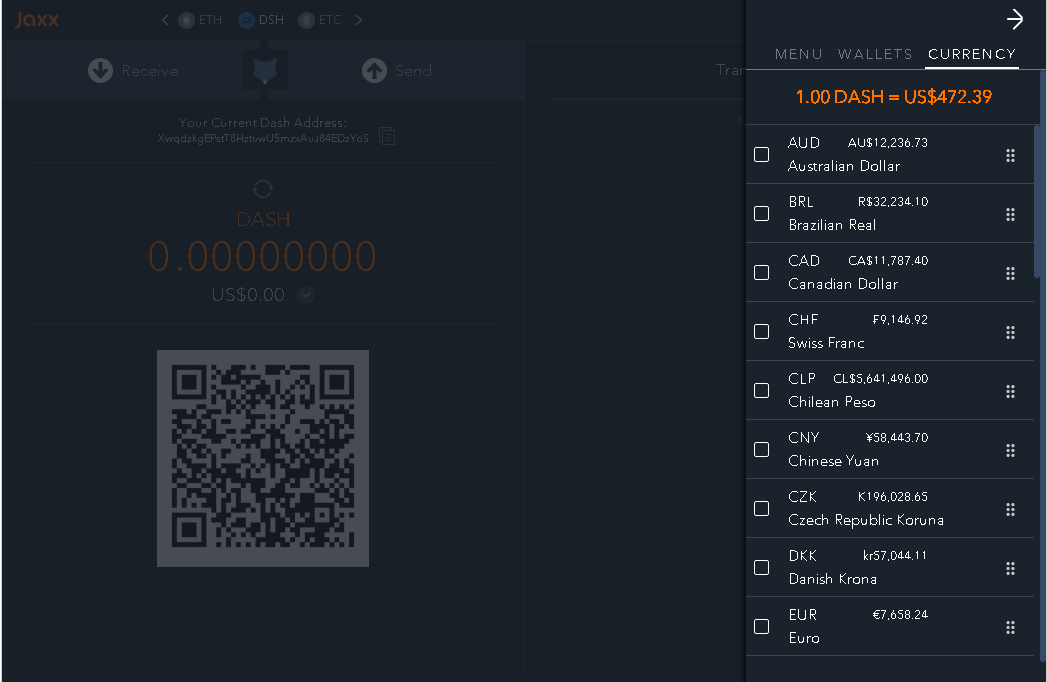

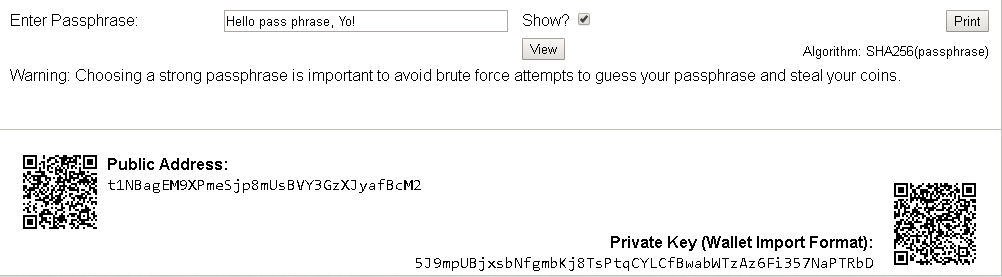

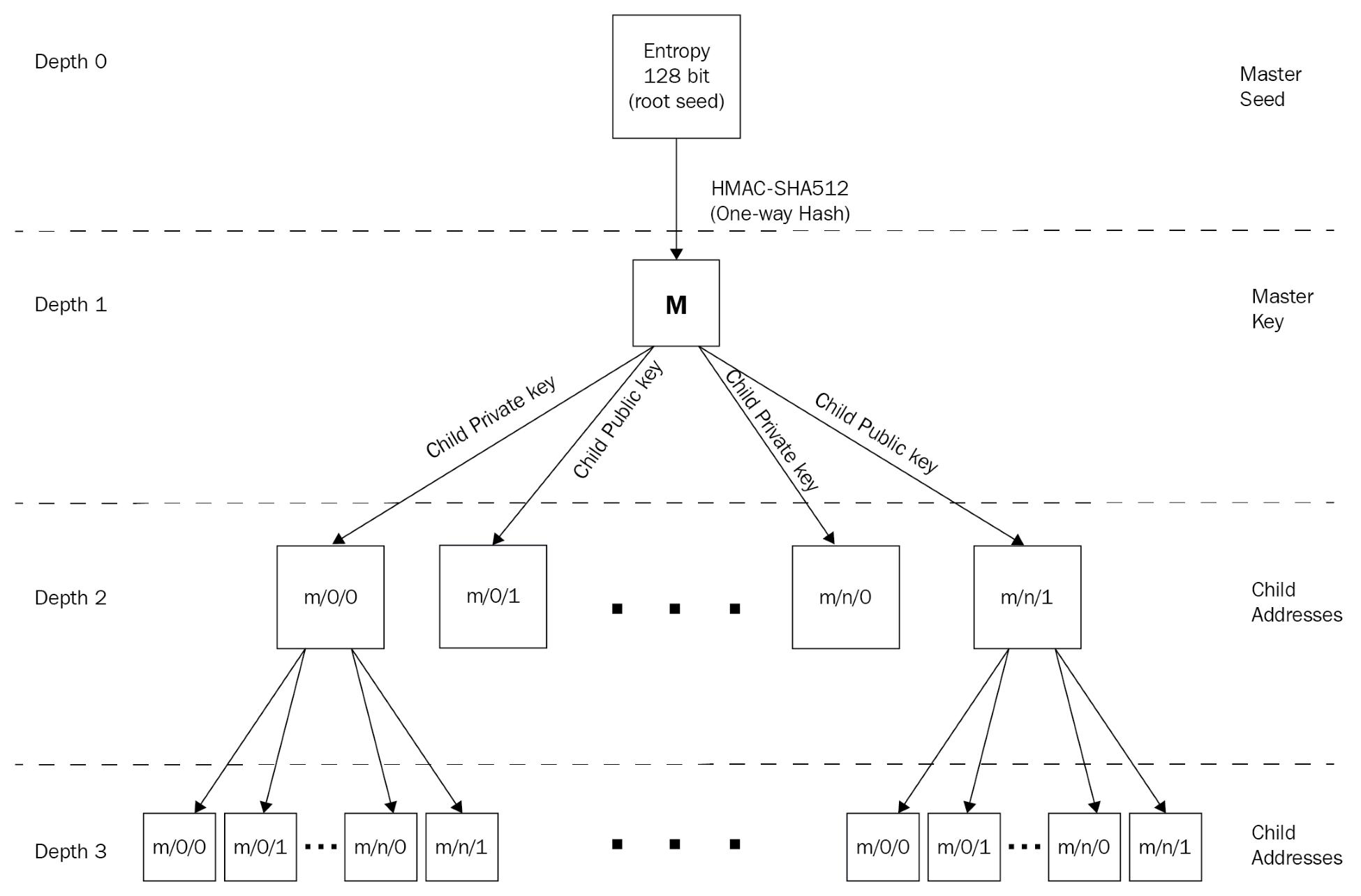

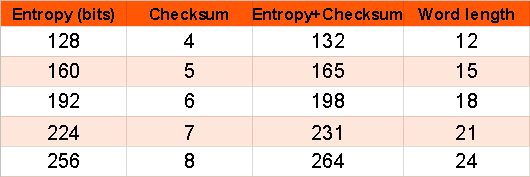

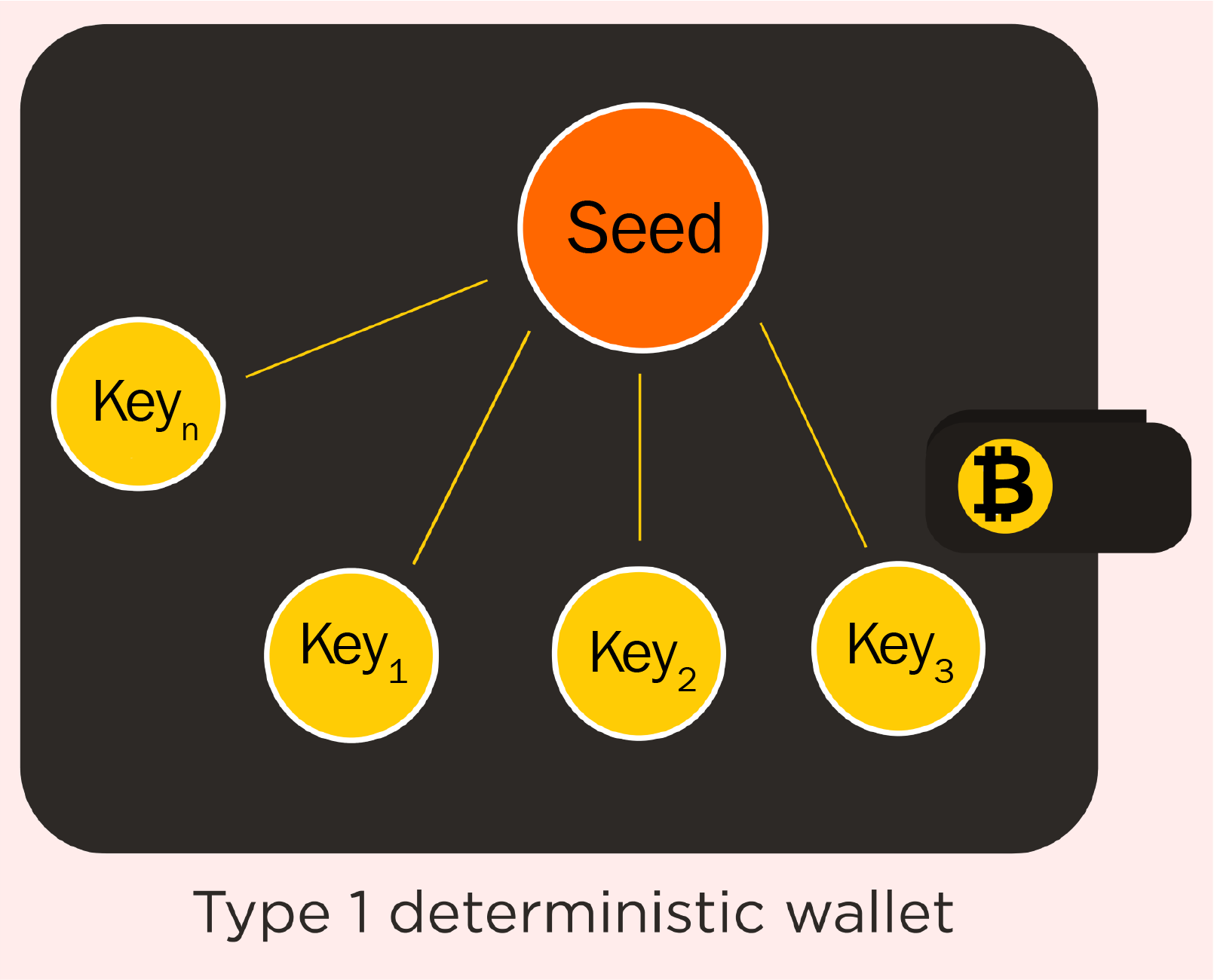

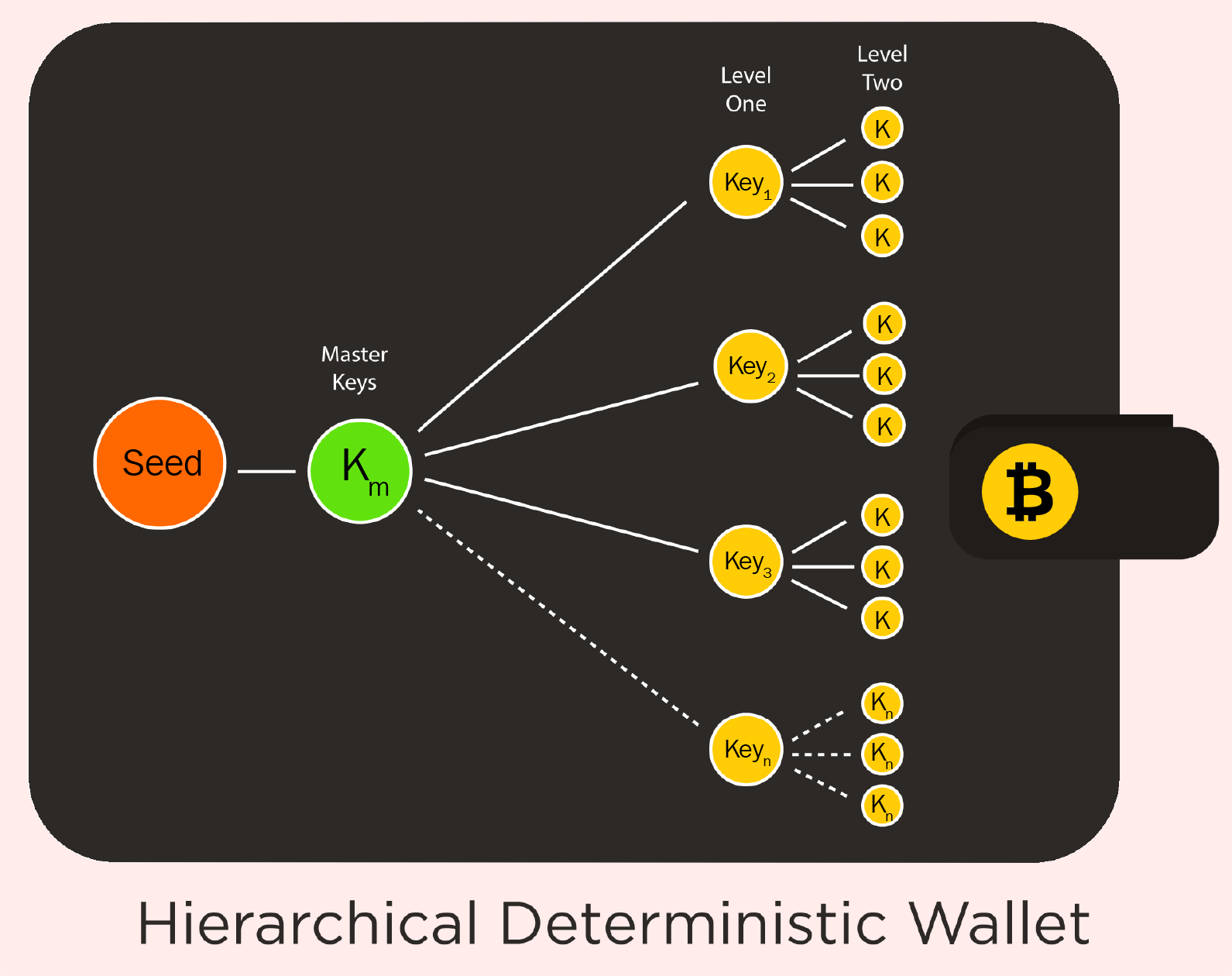

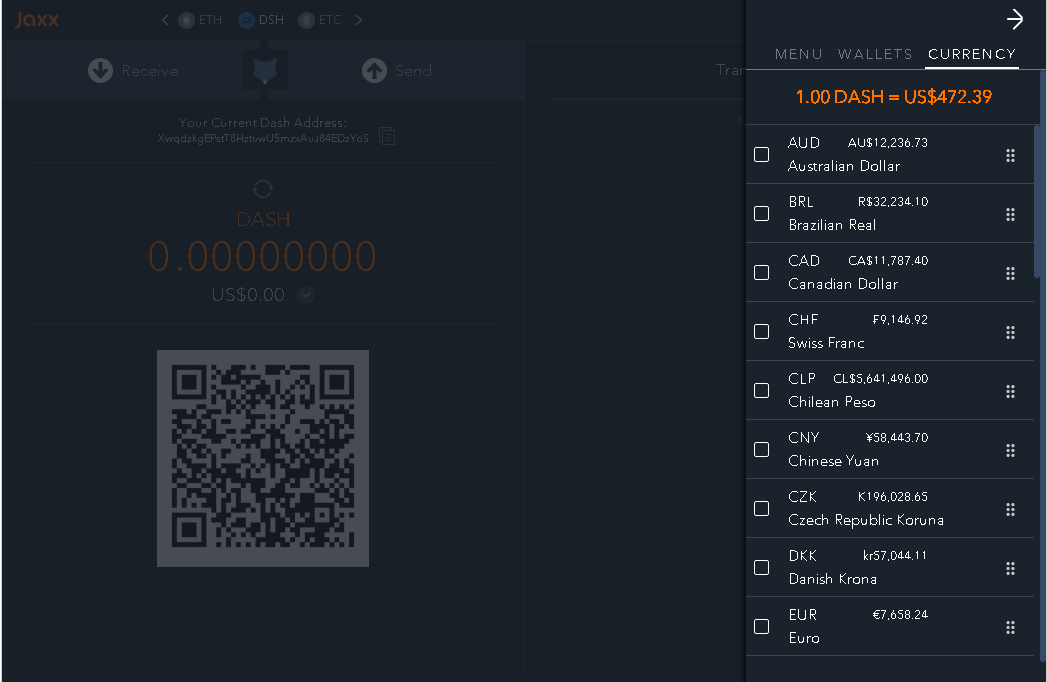

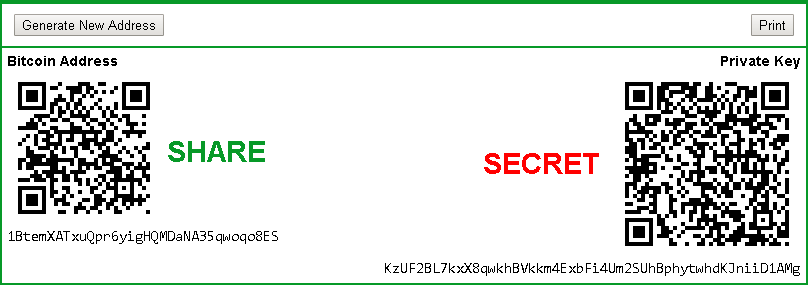

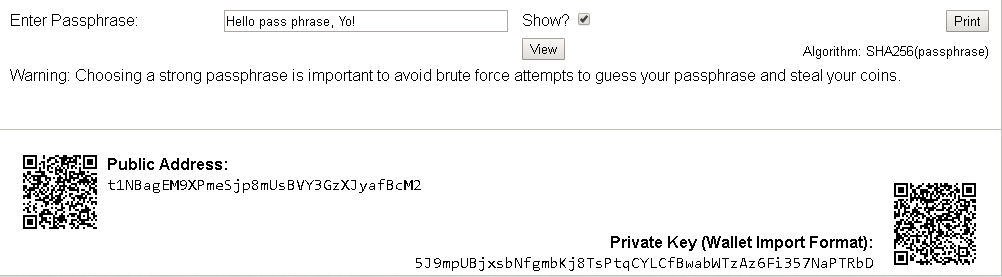

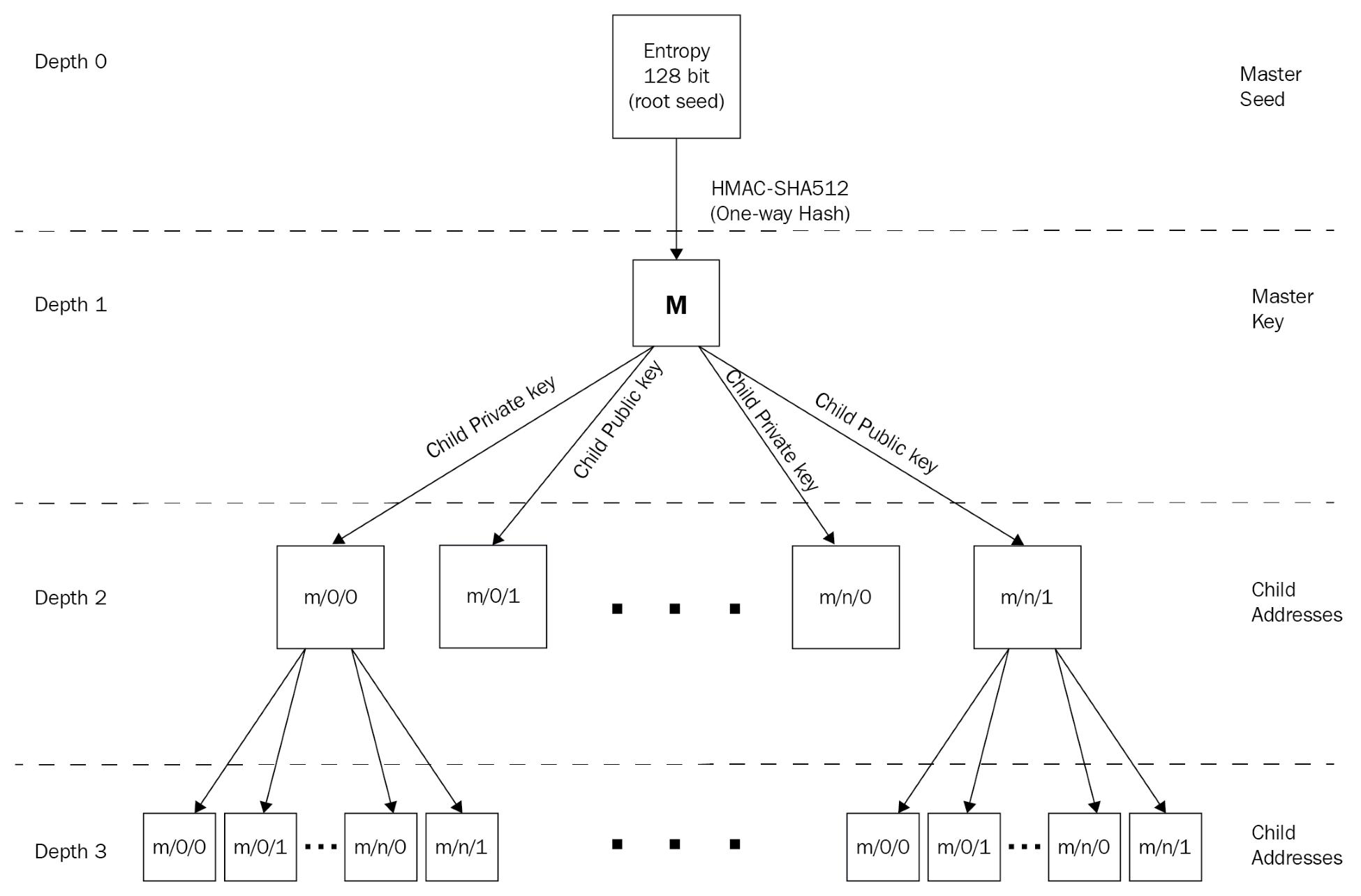

A wallet is a digital wallet used to store public or private keys along with addresses for a transaction. There are various types of wallets available, each one offering a certain level of security and privacy.

Here is a list of the various types of wallets, based on their functions:

It is important to understand the functioning and the need for various wallets along with the requirement for each.

A transaction is the process of transferring data from one address in blockchain to another address. In Bitcoin, it is about transferring Bitcoins from one address to another address. All the transactions happening in blockchain are registered from the start of the chain till the current time; this information is shared across the network and all the P2P nodes. The transaction is confirmed by miners, who are economically compensated for their work.

Each transaction in a blockchain goes through a number of confirmations, as they are the consensus of a transaction. Without confirmation, no transaction can be validated.

Nodes are part of a blockchain network and perform functions as assigned to them. Any device connected to the Bitcoin network can be called a node. Nodes that are integral components of the network and validate all the rules of the blockchain are called full nodes. Another type of Node is called a super node, which acts as a highly connected redistribution point, as well as a relay station.

A blockchain performs various functions. We will discuss each of them briefly here and in detail later:

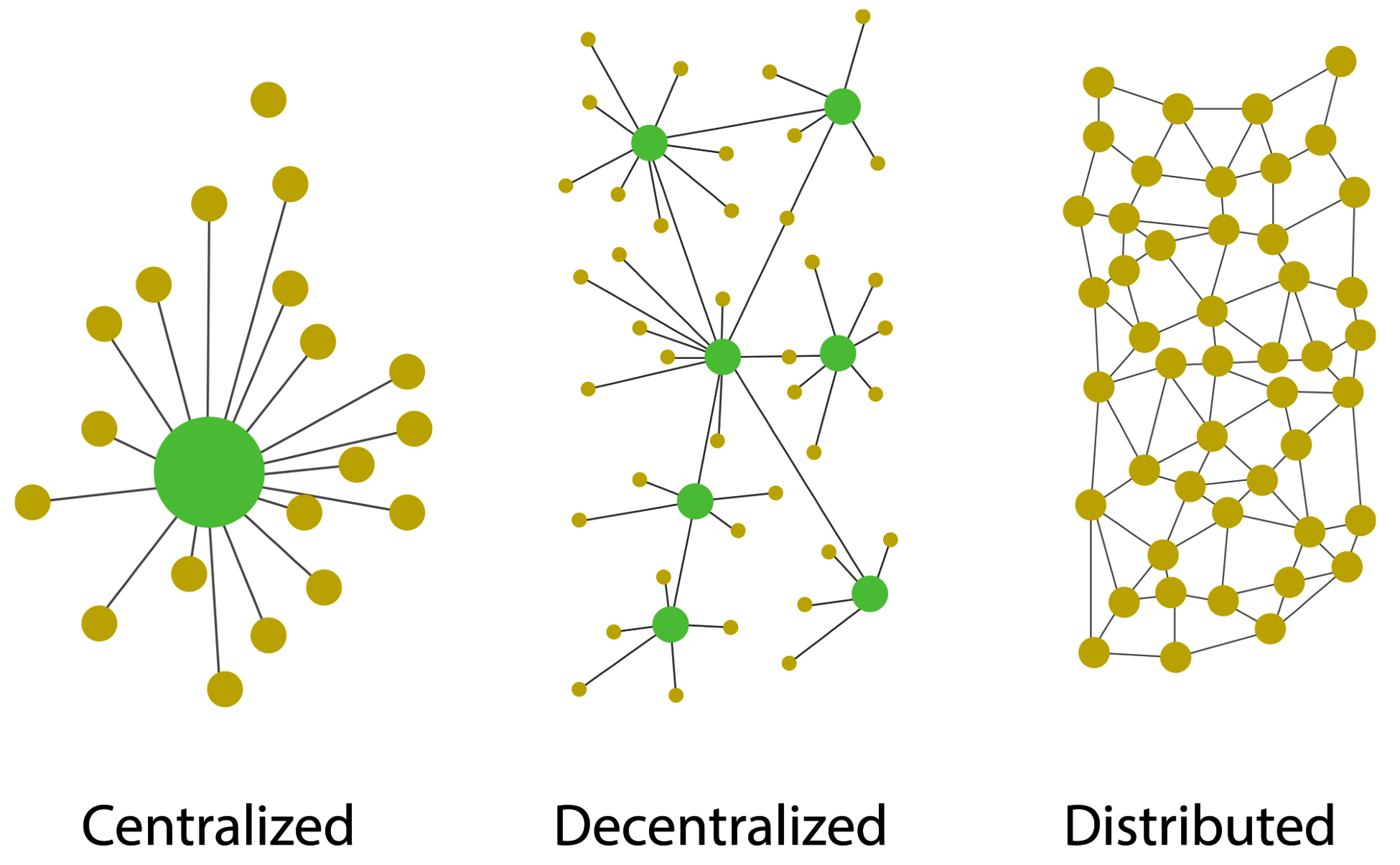

The following diagram depicts the difference between centralized, decentralized, and distributed networks:

Being distributed in nature, blockchain offers lots of out-of-the-box features, such as high stability, security, scalability, and other features discussed previously.

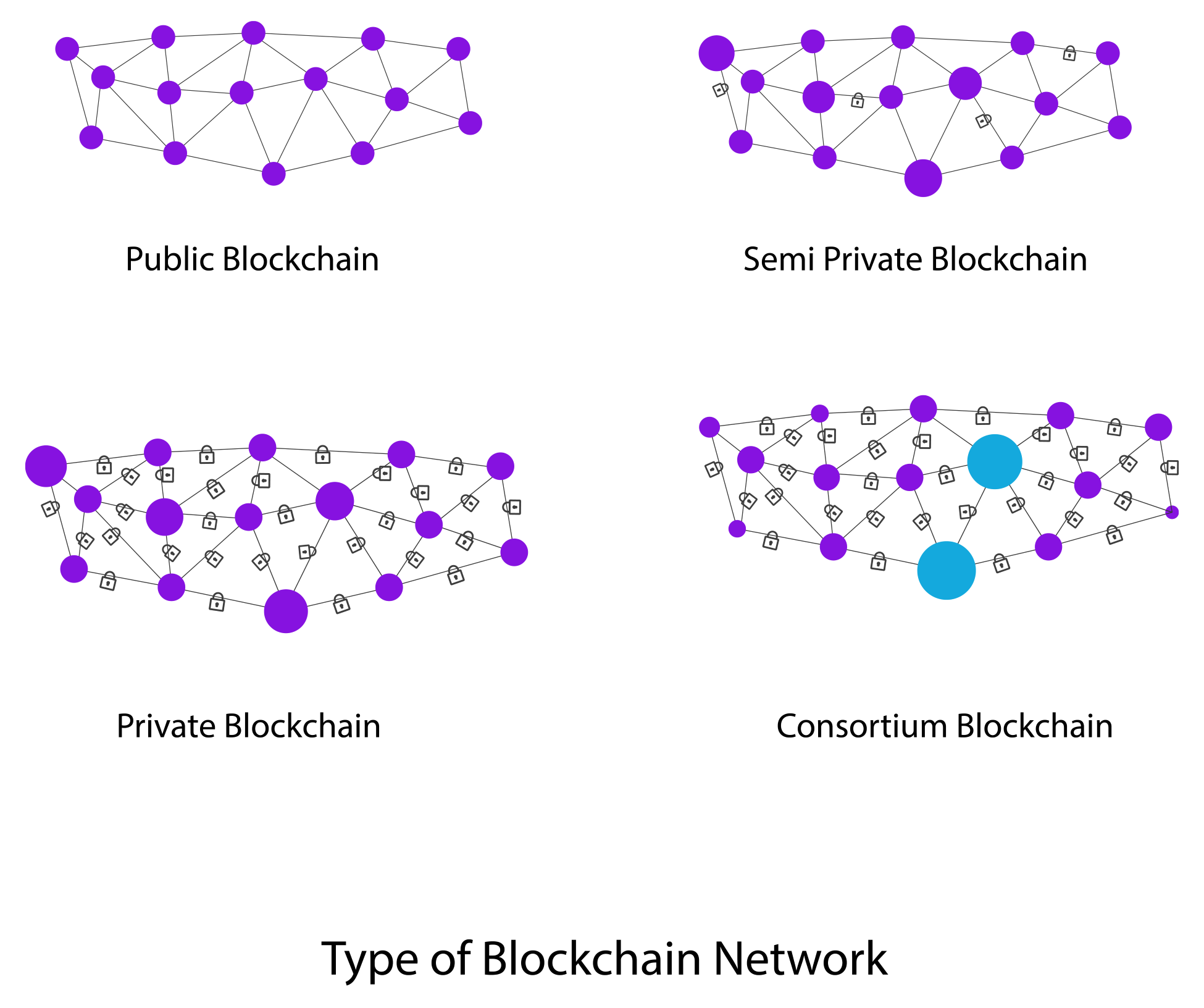

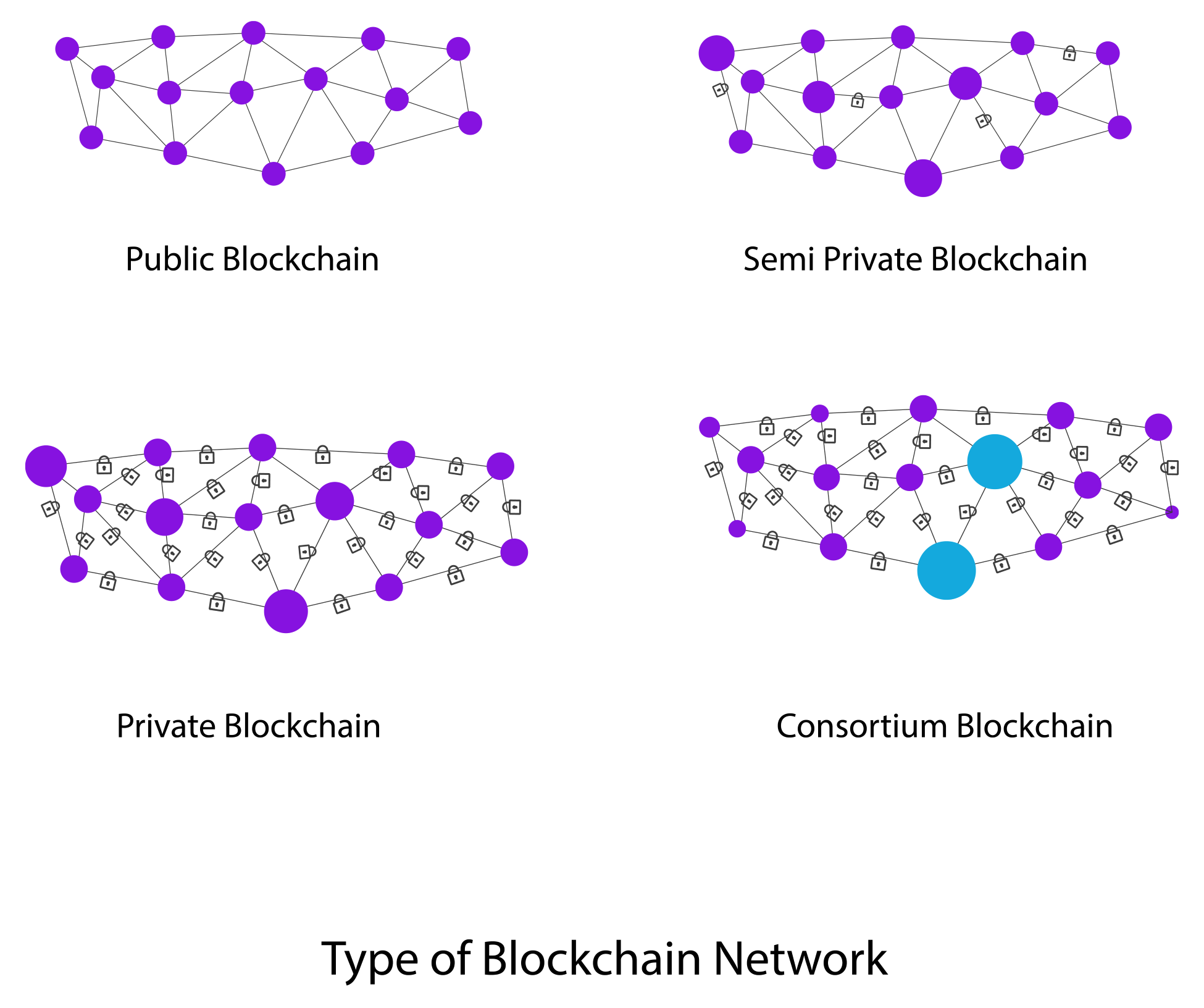

Considering the way blockchain has evolved, we can classify blockchain into multiple types; these types define the course of blockchain and make it go beyond the use of P2P money. The following diagram displays the different types of blockchain networks currently available or proposed.

We will now discuss each type of blockchain network in detail.

A public blockchain is a blockchain where anyone in the world can become a node in the transaction process. Economic incentives for cryptographic verification may or may not be present. It is a completely open public ledger system. Public blockchains can also be called permissionless ledgers.

These blockchains are secured by crypto economics, that is, economic incentives and cryptographic verification using mechanisms such as PoW or PoS or any other consensus mechanism. Some popular examples of this type of blockchain are Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and so on.

A semi-private blockchain is usually run by a single organization or a group of individuals who grant access to any user, who can either be a direct consumer or for internal organizational purposes. This type of blockchain has a public part exposed to the general audience, which is open for participation by anyone.

In private blockchains, the write permissions are with one organization or with a certain group of individuals. Read permissions are public or restricted to a large set of users. Transactions in this type of blockchain are to be verified by very few nodes in the system.

Some prime examples of private blockchain include Gem Health network, Corda, and so on.

In this type of blockchain, as the name suggests, the consensus power is restricted to a set of people or nodes. It can also be known as a permission private blockchain. Transaction approval time is fast, due to fewer nodes. Economic rewards for mining are not available in these types of blockchains.

A few examples of consortium-based blockchains are Deutsche Boerse and R3 (financial institutions).

This is one of the classic problems faced by various computer networks, which until recently had no concrete solution. This problem is called Byzantine Generals' Problem (BGP). The problem at its root is about consensus, due to mistrust in the nodes of a network.

Let's imagine that various generals are leading the Byzantine army and are planning to attack a city, with each general having his own battalion. They have to attack at the same time to win. The problem is that one or more of generals can be disloyal and communicate a duping message. Hence, there has to be a way of finding an efficient solution that helps to have seamless communication, even with deceptive generals.

This problem was solved by Castro and Liskov, who presented the Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) algorithm. Later, in 2009, the first practical implementation was made with the invention of Bitcoin by the development of PoW as a system to achieve consensus.

We will be discussing in detail the BGP in later chapters.

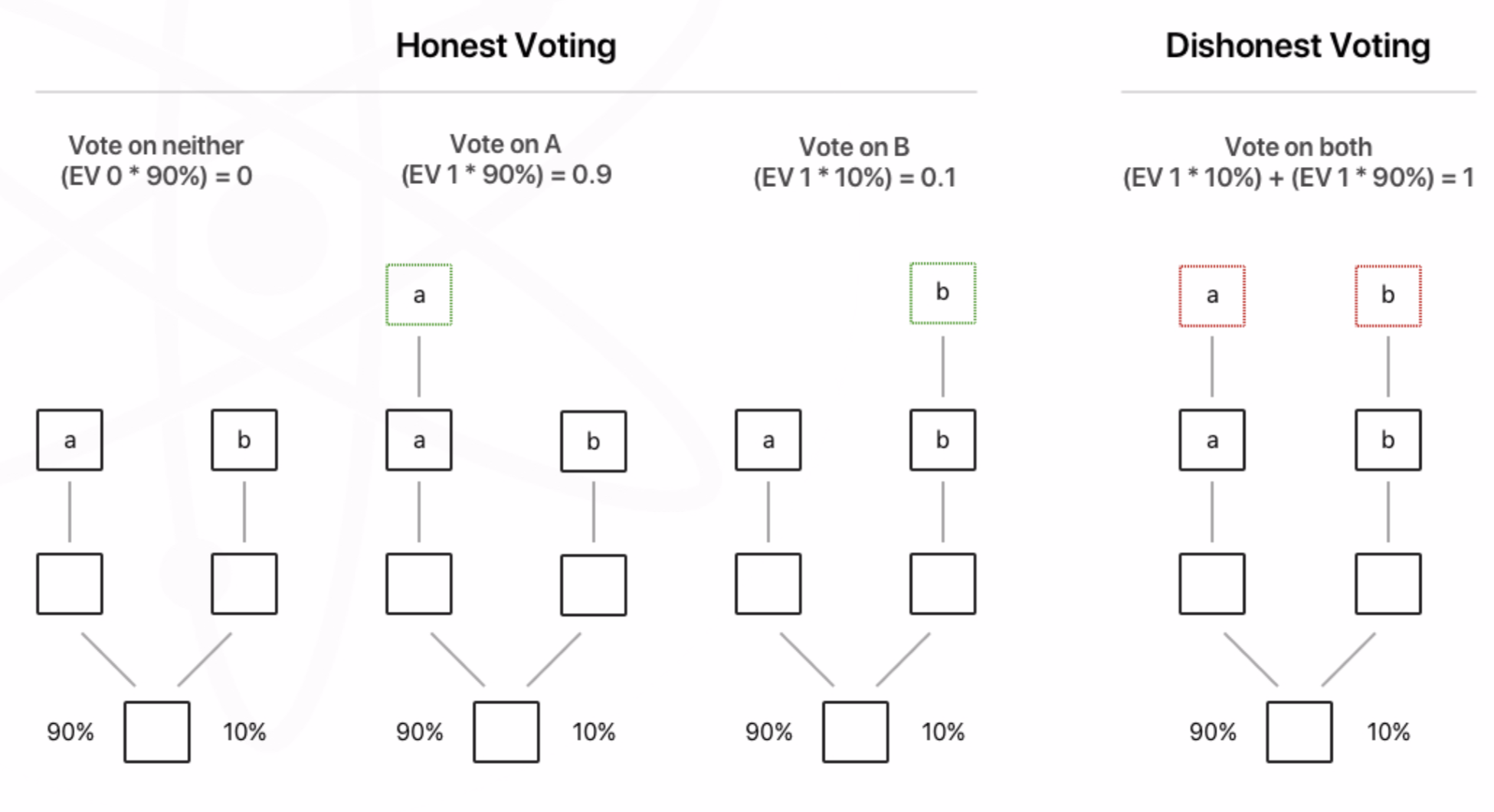

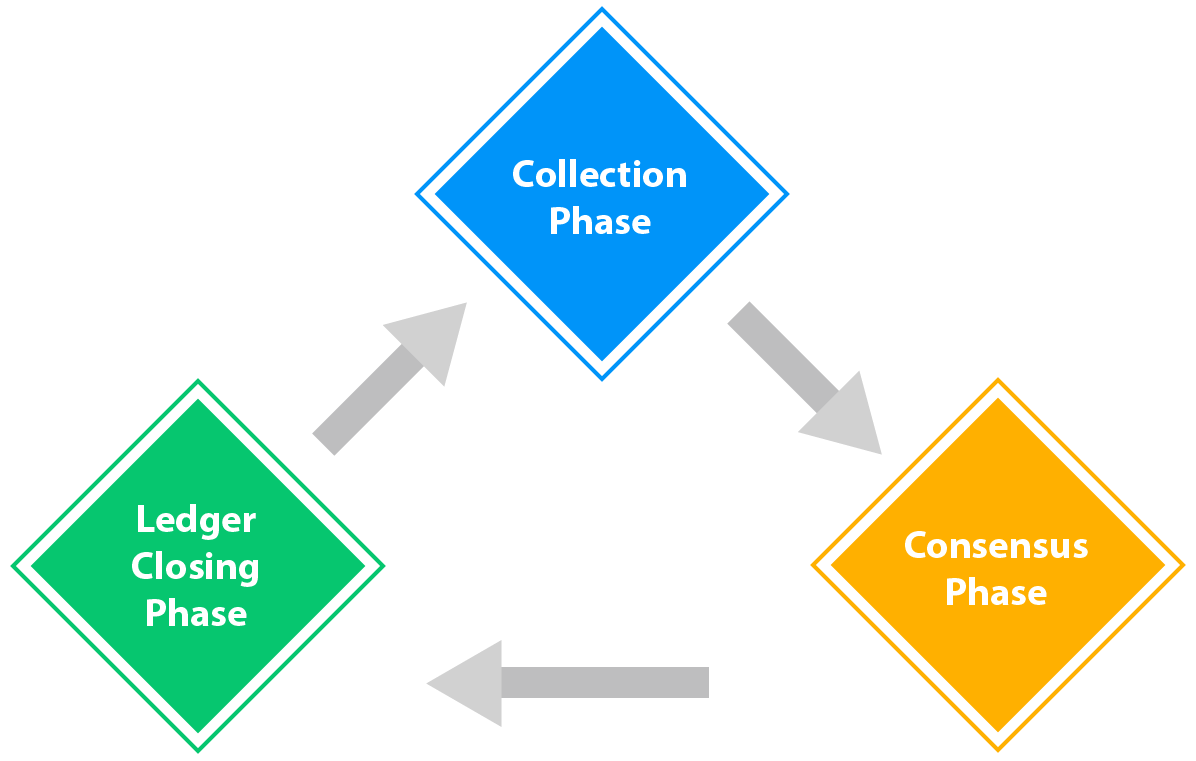

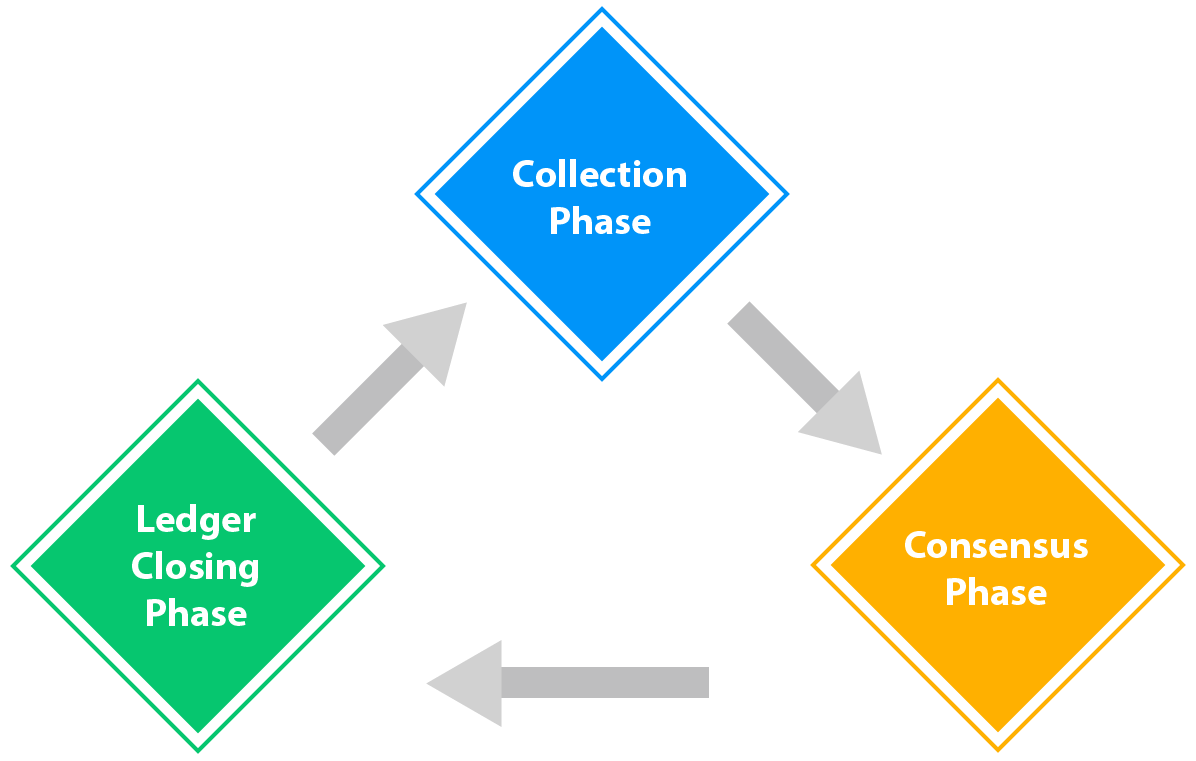

Consensus is the process of reaching a general agreement among nodes within a blockchain. There are various algorithms available for this especially when it is a distributed network and an agreement on a single value is required.

Mechanisms of consensus: Every blockchain has to have one mechanism that can handle various nodes present in the network. Some of the prime mechanisms for consensus by blockchain are the following:

All the preceding algorithms and a host of already available or currently under research make sure that the perfect consensus state is achieved and no possible security threats are present on the network.

It is time to discuss the benefits as well as the challenges or limitations faced by blockchain technology, and what steps are being taken by the community as a whole.

If it's all about trust and security, do we really need a trusted system, even after everything is already highly secure and private? Let's go through the limitations of each of the existing ecosystems where blockchain is a perfect fit.

Record keeping and ledger maintenance in the banking sector is a time and resource-consuming process and is still prone to errors. In the current system, it is easy to move funds within a state, but when we have to move funds across borders, the main problems faced are time and high costs.

Even though most money is just an entry in the database, it still incurs high forex costs and is incredibly slow.

There are lot of problems in record keeping, authentication and transferring of records at a global scale, even after having electronic records, are difficult when implemented practically. Due to no common third party, a lot of records are maintained physically and are prone to damage or loss.

During a case of epidemiology, it becomes essential to access and mine medical records of patients pertaining to a specific geography. Blockchain comes as a boon in such situation, since medical records can be easily accessible if stored in the blockchain, and they are also secure and private for the required users.

Any government agency has to deal with a lot of records for all of its departments; new filings can be done on blockchain, making sure that the data remains forever secure and safe in a distributed system.

This transparency and distributed nature of data storage leads to a corruption-free system, since the consensus makes sure the participants in the blockchain are using the required criteria when needed.

Copyright and creative records can be secured and authenticated, keeping a tab on copyright misuse and licensing.

One premier example of this is KodakCoin, which is a photographer-oriented cryptocurrency based on blockchain, launched to be used for payments of licensing photographs.

Verification, authentication, and inspection is hard. It is highly prone to theft and misuse. Blockchain can offer a great semi-private access to the records, making sure signing of degrees is done digitally using blockchain.

Gradual record keeping of degrees and scores will benefit efficient utilization of resources as well as proper distribution and ease in inspection process.

The preceding are just some of the varied use cases of blockchain, apart from Bitcoins and alternative cryptocurrencies. In the coming chapters, we will be discussing these points in much more detail.

As with any technology, there are various challenges and limitations of blockchain technology. It is important to address these challenges and come up with a more robust, reliable, and resourceful solution for all. Let's briefly discuss each of these challenges and their solutions.

Blockchain is complex to understand and easy to implement.

However, with widespread awareness and discussions, this might be made easier in the future.

If a blockchain does not have a robust network with a good grid of nodes, it will be difficult to maintain the blockchain and provide a definite consensus to the ongoing transactions.

Although blockchain-based transactions are very high in speed and also cheaper when compared to any other conventional methods, from time to time, this is becoming difficult, and the speed reduces as the number of transactions per block reduces.

In terms of cost, a lot of hardware is required, which in turn leads to huge network costs and the need for an intermittent network among the nodes.

Various scaling solutions have been presented by the community. The best is increasing the block size to achieve a greater number of transactions per block, or a system of dynamic block size. Apart from this, there are various other solutions also presented to keep the speed reduced and the costs in check.

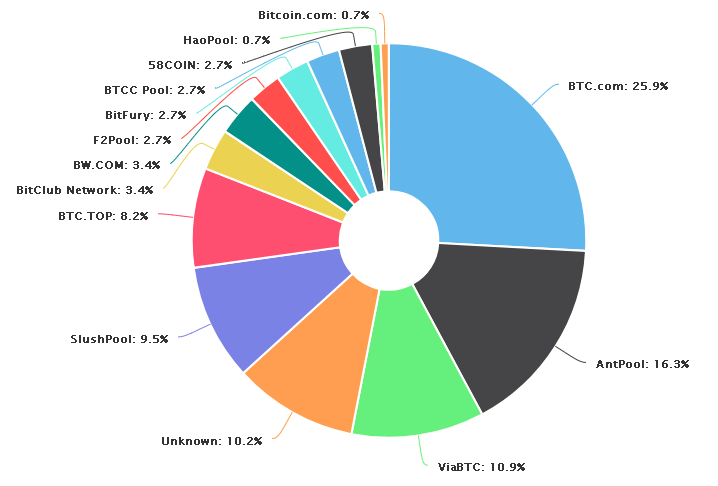

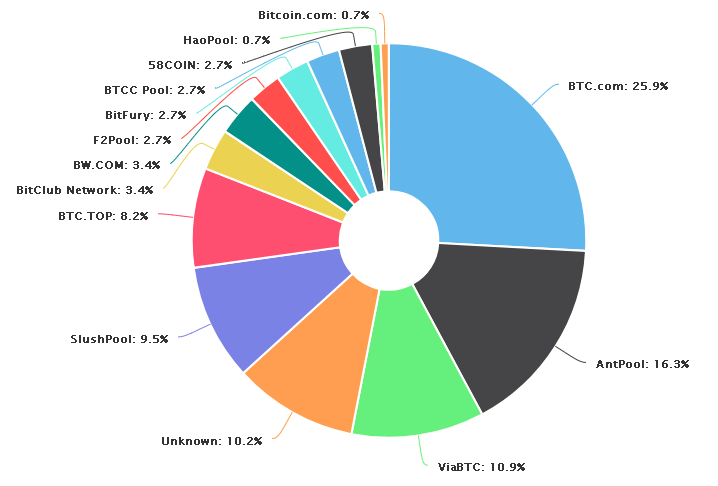

This is a type of attack on the blockchain network whereby a given set of coins is spent in more than one transaction; one issue that was noted here by the founder/founders of Bitcoin at the time of launch is 51 attacks. In this case, if a certain miner or group of miners takes control of more than half of the computing power of blockchain, being open in nature, anyone can be a part of the node; this triggers a 51 attack, in which, due to majority control of the network, the person can confirm a wrong transaction, leading to the same coin being spent twice.

Another way to achieve this is by having two conflicting transactions in rapid succession in the blockchain network, but if a lot of confirmations are achieved, then this can be avoided.

There are various other features that will be discussed in the coming chapters, it should be noted that all of these features exist in the present systems but considering active community support, all these limitations are being mitigated at a high rate.

This chapter introduced us to blockchain. First, ideas about distributed networks, financial transactions, and P2P networks were discussed. Then, we discussed the history of blockchain and various other topics, such as the elements of blockchain, the types of blockchains, and consensus.

In the coming chapters, we will be discussing blockchain in more detail; we will discuss the mechanics behind blockchain, Bitcoins. We will also learn about achieving consensus in much greater detail, along with diving deep into blockchain-based applications such as wallets, Ethereum, Hyperledger, all the way to creating your own cryptocurrency.

Blockchain is not a single technology, but more of a technique. A blockchain is an architectural concept, and there are many ways that blockchains can be built, and each of the variations will have different effects on how the system operates. In this chapter, we are going to cover the aspects of blockchain technology that are used in all or most of the current implementations.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to describe the pieces of a blockchain and evaluate the capacities of one blockchain technology against another at the architectural level.

Here are the concepts we will be covering:

Blockchain is a specific technology, but there are many forms and varieties. For instance, Bitcoin and Ethereum are proof-of-work blockchains. Ethereum has smart contracts, and many blockchains allow custom tokens. Blockchains can be differentiated by their consensus algorithm (PoS, PoW, and others)—covered in Chapter 7, Achieving Consensus, and their feature set, such as the ability to run smart contracts and how those smart contracts operate in practice. All of these variations have a common concept: the block. The most basic unit of a blockchain is the block. The simplest way of thinking of a block is to imagine a basic spreadsheet. In it, you might see entries such as this:

| Account | Change | New Balance | Old Balance | Operation |

| Acct-9234222 | −$2,000 | $5,000 | $7,000 | Send funds to account-12345678 |

| Acct-12345678 | $2,000 | $2,000 | 0 | Receive funds from account-9234222 |

| Acct-3456789 | -$200 | $50 | $250 | Send funds to account-68890234 |

| Acct-68890234 | $200 | $800 | $600 | Receive funds from account-3456789 |

A block is a set of transaction entries across the network, stored on computers that act as participants in the blockchain network. Each blockchain network has a block time, or the approximate amount of time that each block represents for transactions, and a block size: the total amount of transactions that a block can handle no matter what. If a network had a block time of two minutes and there were only four transactions during those two minutes, then the block would contain just those four transactions. If a network had 10,000,000 transactions, then there may be too many to fit inside the block size. In this case, transactions would have to wait for their turn for an open block with remaining space. Some blockchains handle this problem with the concept of network fees. A network fee is the amount (denominated in the blockchain's native token) that a sender is willing to pay to have a transaction included in a block. The higher the fee, the greater the priority to be included on the chain immediately.

In addition to the transaction ledger, each block typically contains some additional metadata. The metadata includes the following:

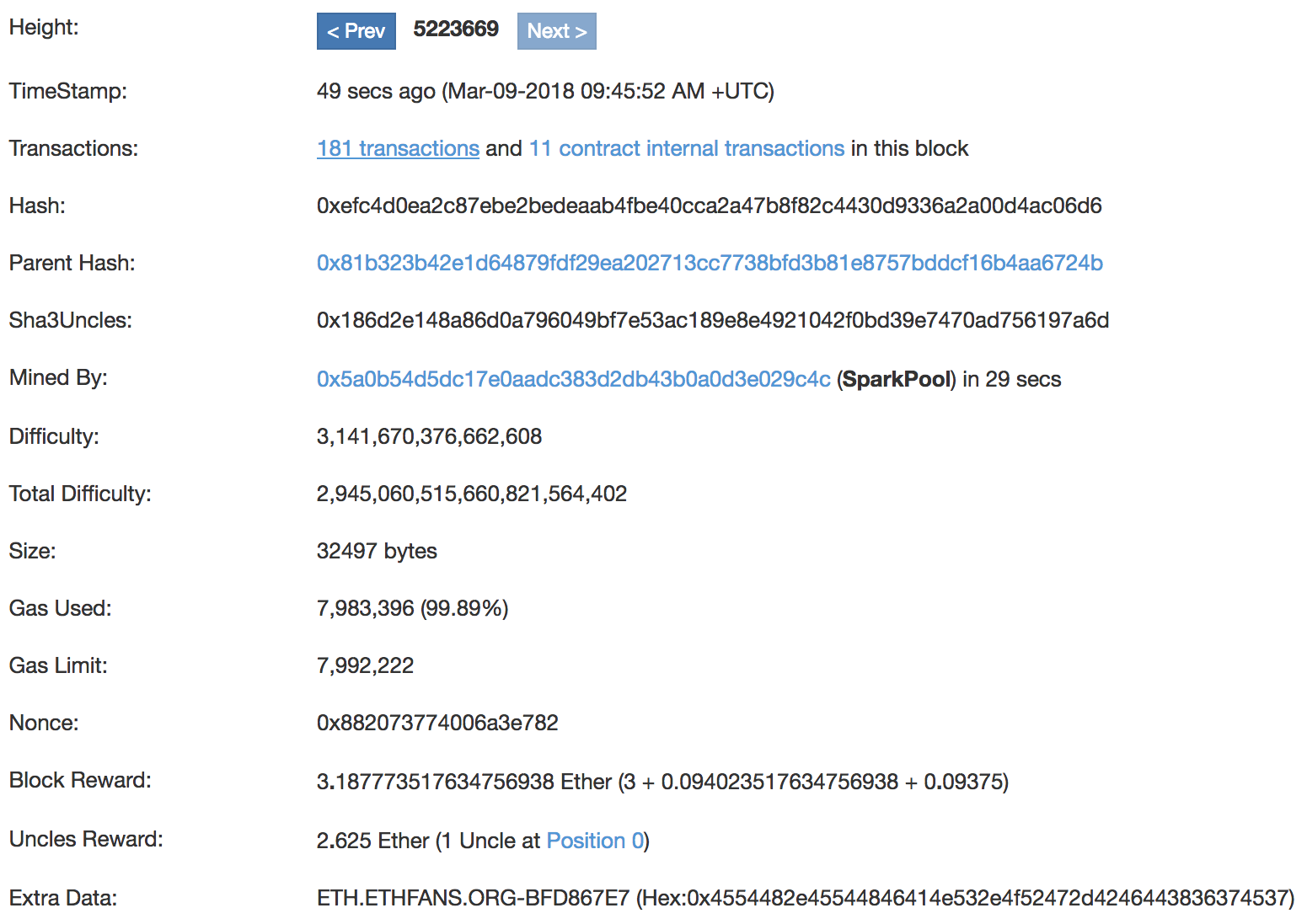

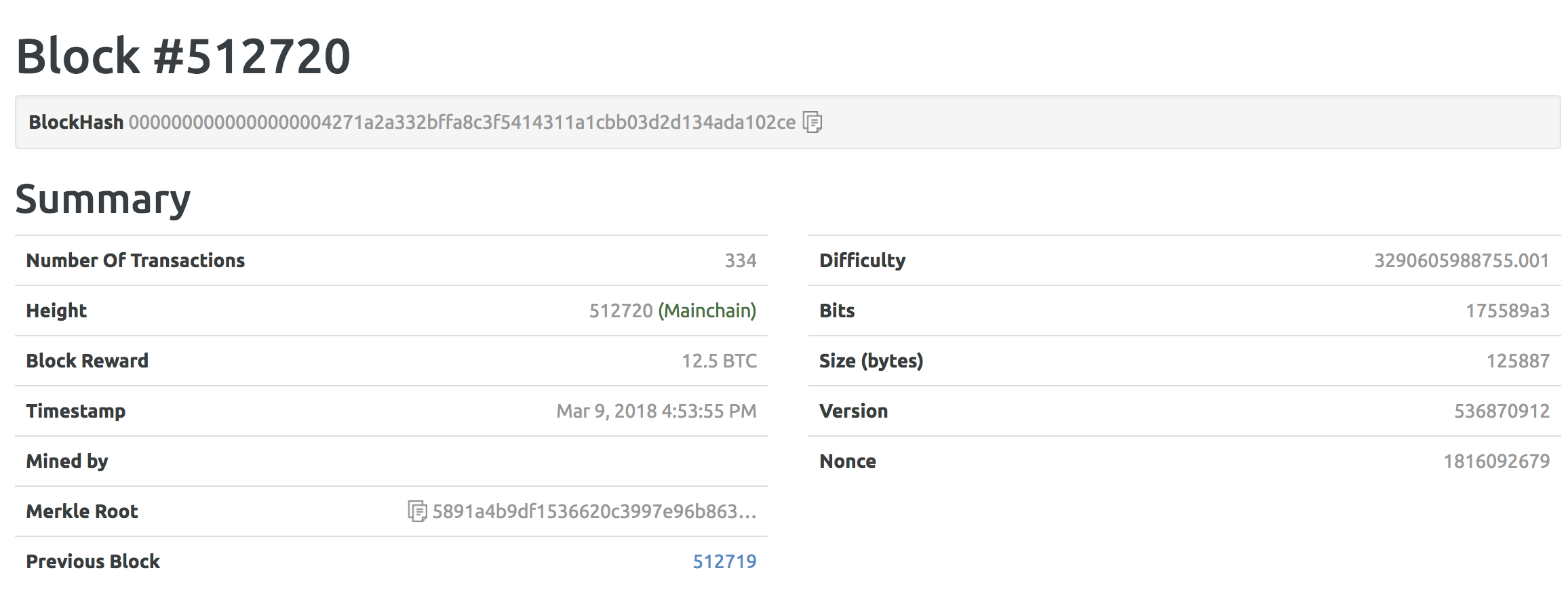

These basics tend to be common for all blockchains. Ethereum, Bitcoin, Litecoin, and others use this common pattern, and this pattern is what makes it a chain. Each chain also tends to include other metadata that is specific to that ecosystem, and those differences will be discussed in future chapters. Here is an example from the Bitcoin blockchain:

If you are asking, What is a Merkle root? that brings us to our next set of key concepts: hashing and signature.

Let's say you have two text files that are 50 pages long. You want to know whether they are the same or different. One way you could do this would be to hash them. Hashing (or a hashing function) is a mathematical procedure by which any input is turned into a fixed-length output. There are many of these functions, the most common being SHA-1, SHA-2, and MD5. For instance, here is the output of a hashing function called MD5 with an input of two pages of text:

9a137a78cf0c364e4d94078af1e221be

What's powerful about hashing functions is what happens when I add a single character to the end and run the same function:

8469c950d50b3394a30df3e0d2d14d74

As you can see, the output is completely different. If you want to quickly prove that some data has not been changed in any way, a hash function will do it. For our discussion, here are the important parts of hashing functions:

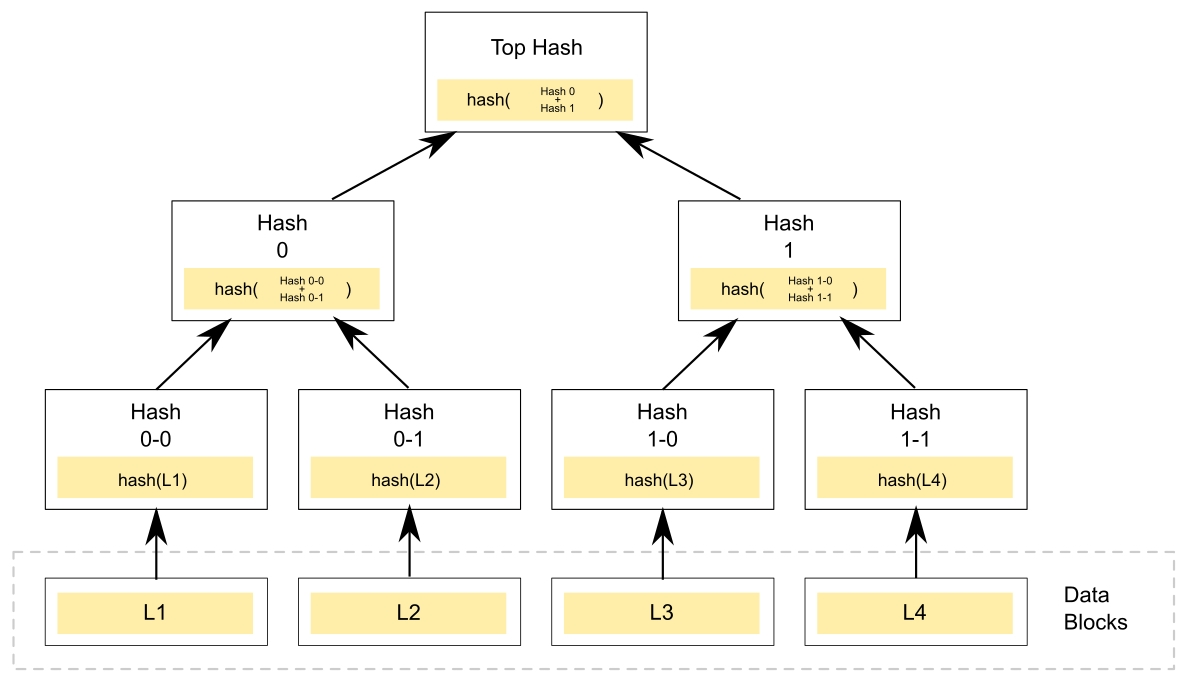

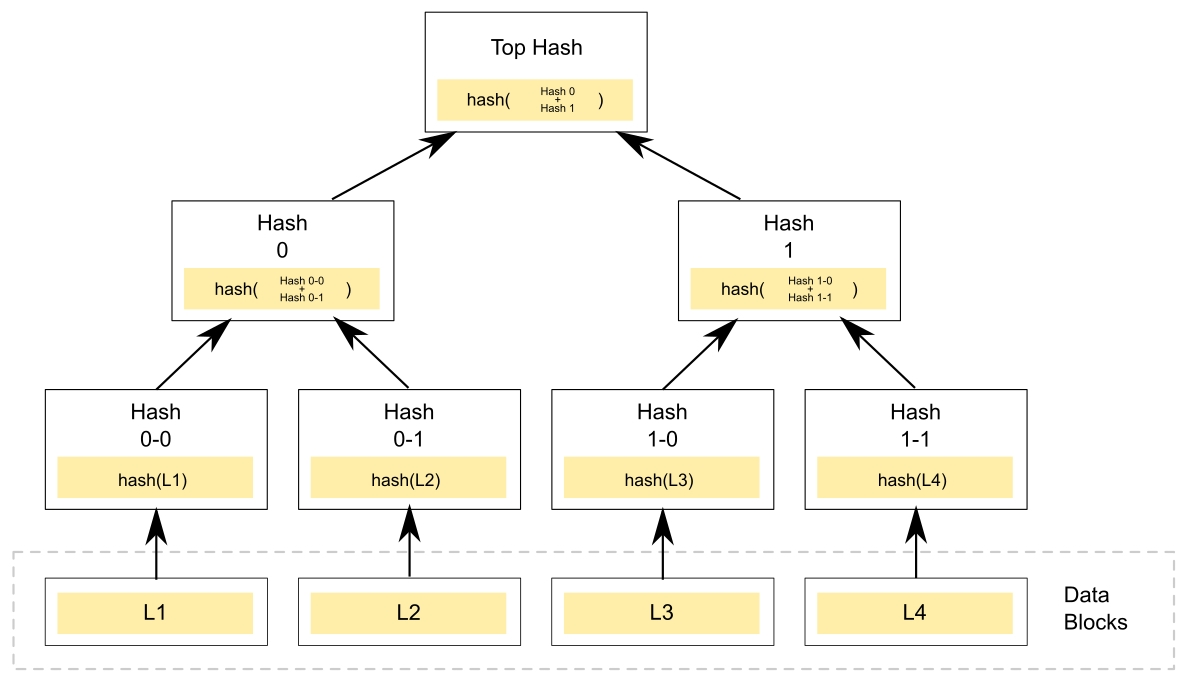

This recursive property to hashing is what brings us to the concept of a Merkle tree, named after the man who patented it. A Merkle tree is a data structure that, if your were to draw it on a whiteboard, tends to resemble a tree. At each step of the tree, the root node contains a hash of the data of its children. The following is a diagram of a Merkle tree:

In a blockchain, this means that there is a recursive hashing process happening. A recursive hash is when we take a hash of hashes. For instance, imagine we have the following words and their hashes. Here, we will use the MD5 algorithm, because it is easy to find MD5 hashing code on the web, so you can try for yourself:

Salad: c2e055acd7ea39b9762acfa672a74136

Fork: b2fcb4ba898f479790076dbd5daa133f

Spoon: 4b8e23084e0f4d55a47102da363ef90c

To take the recursive or the root hash, we would add these hashes together, as follows:

c2e055acd7ea39b9762acfa672a74136b2fcb4ba898f479790076dbd5daa133f4b8e23084e0f4d55a47102da363ef90c

Then we would take the hash of that value, which would result in the following:

189d3992be73a5eceb9c6f7cc1ec66e1

This process can happen over and over again. The final hash can then be used to check whether any of the values in the tree have been changed. This root hash is a data efficient and a powerful way to ensure that data is consistent.

Each block contains the root hash of all the transactions. Because of the one-way nature of hashing, anyone can look at this root hash and compare it to the data in the block and know whether all the data is valid and unchanged. This allows anyone to quickly verify that every transaction is correct. Each blockchain has small variations on this pattern (using different functions or storing the data slightly differently), but the basic concept is the same.

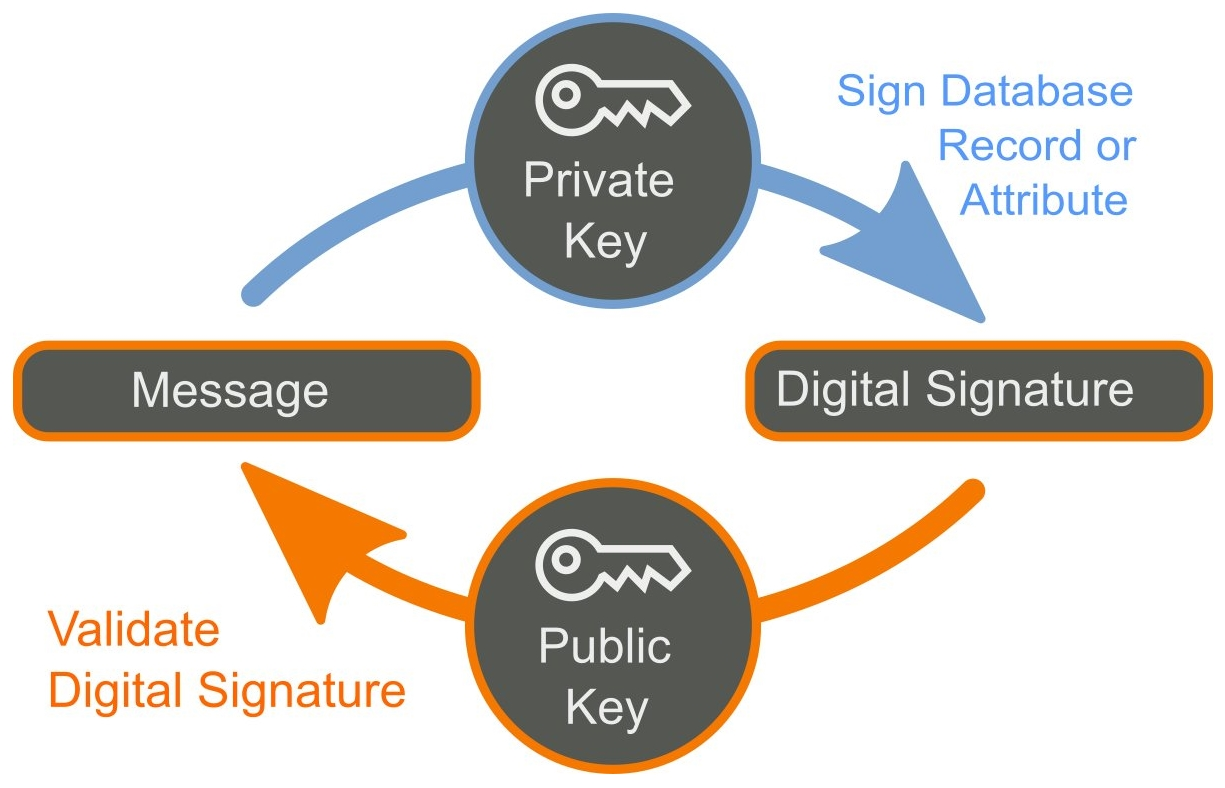

Now that we've covered hashing, it's time to go over a related concept: digital signatures. Digital signatures use the properties of hashing to not only prove that data hasn't changed but to provide assurances of who created it. Digital signatures work off the concept of hashing but add a new concept as well: digital keys.

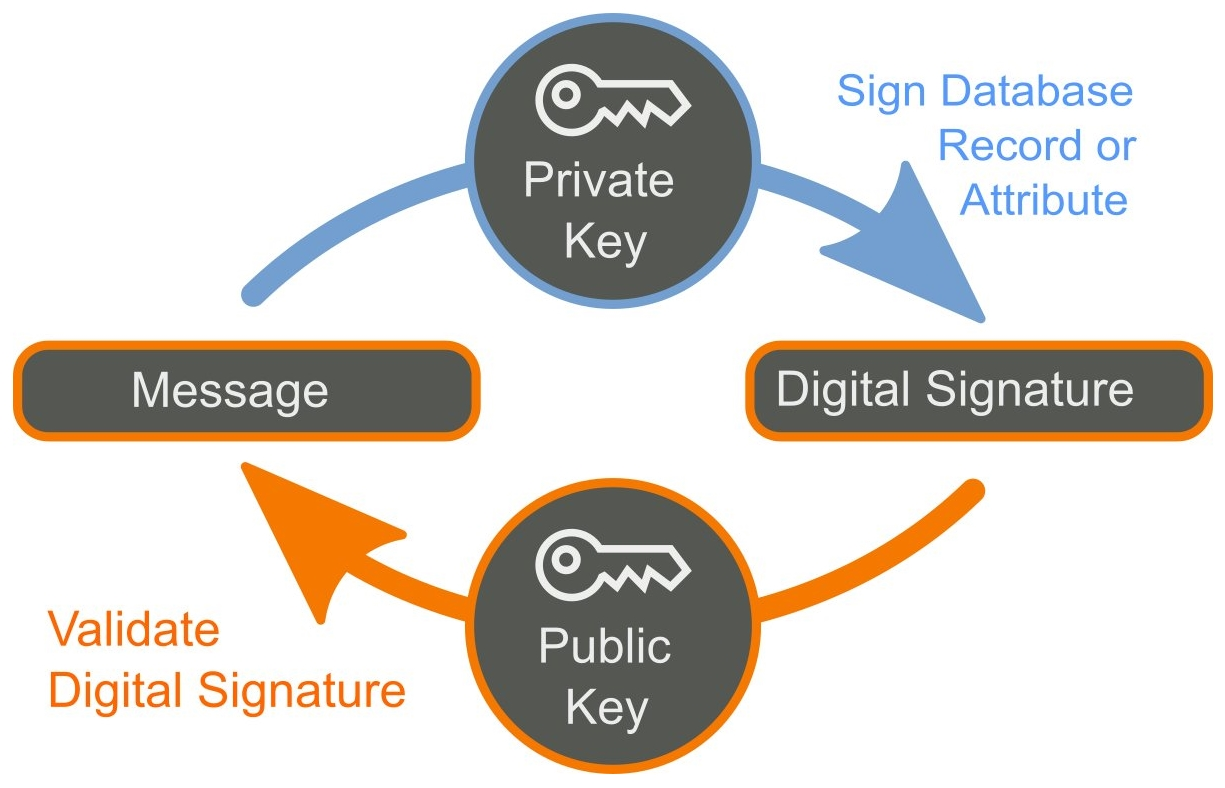

All common approaches to digital signatures use what is called Public Key Cryptography. In Public Key Cryptography, there are two keys: one public and one private. To create a signature, the first hash is produced of the original data, and then the private key is used to encrypt that hash. That encrypted hash, along with other information, such as the encryption method used to become part of the signature, are attached to the original data.

This is where the public key comes into play. The mathematical link between the public key and the private key allows the public key to decrypt the hash, and then the hash can be used to check the data. Thus, two things can now be checked: who signed the data and that the data that was signed has not been altered. The following is a diagrammatic representation of the same:

This form of cryptography is critical to blockchain technology. Through hashing and digital signatures, a blockchain is able to record information both on actions (movement of tokens) as well as prove who initiated those actions (via digital signatures).

Let's create an example of how this would look. Jeremy and Nadia wish to send messages to each other securely. Each publishes a public key. Jeremy's will look something as follows (using an RSA algorithm with 1,024 bits):

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIGeMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4GMADCBiAKBgH+CYOAgKsHTrMlsaZ32Gpdfo4pw

JRfHu5d+KoOgbmYb0C2y1PiHNGEyXgd0a8iO1KWvzwRUMkPJr7DbVBnfl1YfucNp

OjAsUWT1pq+OVQ599zecpnUpyaLyg/aW9ibjWAGiRDVXemj0UgMUVNHmi+OEuHVQ

ccy5eYVGzz5RYaovAgMBAAE=

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

With that key, he will keep private another key, which looks as follows:

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIICWwIBAAKBgH+CYOAgKsHTrMlsaZ32Gpdfo4pwJRfHu5d+KoOgbmYb0C2y1PiH

NGEyXgd0a8iO1KWvzwRUMkPJr7DbVBnfl1YfucNpOjAsUWT1pq+OVQ599zecpnUp

yaLyg/aW9ibjWAGiRDVXemj0UgMUVNHmi+OEuHVQccy5eYVGzz5RYaovAgMBAAEC

gYBR4AQYpk8OOr9+bxC6j2avwIegwzXuOSBpvGfMMV3yTvW0AlriYt7tcowSOV1k

YOKGqYdCflXwVTdtVsh//KSNiFtsLih2FRC+Uj1fEu2zpGzErhFCN2sv1t+2wjlk

TRY78prPNa+3K2Ld3NJse3gmhodYqRkxFFxlCmOxTzc4wQJBAOQ0PtsKCZwxRsyx

GAtULHWFIhV9o0k/DjLw5rreA8H3lb3tYZ5ErYuhS0HlI+7mrPUqzYaltG6QpJQY

YlMgktECQQCPClB1xxoIvccmWGoEvqG07kZ4OBZcBmgCzF6ULQY4JkU4k7LCxG4q

+wAeWteaP+/3HgS9RDQlHGITAmqhW6z/AkBaB16QzYnzC+GxmWAx//g2ONq0fcdw

eybf4/gy2qnC2SlDL6ZmaRPKVUy6Z2rgsjKj2koRB8iCIiA7qM8Jmn0xAkBzi9Vr

DqaNISBabVlW89cUnNX4Dvag59vlRsmv0J8RhHiuN0FT6/FCbvetjZxUUgm6CVmy

ugGVaNQgnvcb2T5pAkEAsSvEW6yq6KaV9NxXn4Ge4b9lQoGlR6xNrvGfoxto79vL

7nR29ZB4yVFo/kMVstU3uQDB0Pnj2fOUmI3MeoHgJg==

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

In the meantime, Nadia will do the same, resulting in the following two keys:

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIGfMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4GNADCBiQKBgQDHWwgTfI5Tic41YjUZqTmiKt+R

s5OMKIEdHPTyM8FZNaOBWIosFQbYk266V+R7k9odTnwCfi370GOt0k5MdTQilb9h

bK/lYiavIltgBd+1Em7xm7UihwO4th5APcg2vG4sppK41b1a9/I5E6P/jpQ320vF

BMuEtcnBoWawWcbXJwIDAQAB

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

This is her private key:

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIICXQIBAAKBgQDHWwgTfI5Tic41YjUZqTmiKt+Rs5OMKIEdHPTyM8FZNaOBWIos

FQbYk266V+R7k9odTnwCfi370GOt0k5MdTQilb9hbK/lYiavIltgBd+1Em7xm7Ui

hwO4th5APcg2vG4sppK41b1a9/I5E6P/jpQ320vFBMuEtcnBoWawWcbXJwIDAQAB

AoGBAKz9FCv8qHBbI2H1f0huLQHInEoNftpfh3Jg3ziQqpWj0ub5kqSf9lnWzX3L

qQuHB/zoTvnGzlY1xVlfJex4w6w49Muq2Ggdq23CnSoor8ovgmdUhtikfC6HnXwy

PG6rtoUYRBV3j8vRlSo5PtSRD+H4lt2YGhQoXQemwlw+r5pRAkEA+unxBOj7/sec

3Z998qLWw2wV4p9L/wCCfq5neFndjRfVHfDtVrYKOfVuTO1a8gOal2Tz/QI6YMpJ

exo9OEbleQJBAMtlimh4S95mxGHPVwWvCtmxaFR4RxUpAcYtX3R+ko1kbZ+4Q3Jd

TYD5JGaVBGDodBCRAJALwBv1J/o/BYIhmZ8CQBdtVlKWCkk8i/npVVIdQB4Y7mYt

Z2QUwRpg4EpNYbE1w3E7OH27G3NT5guKsc4c5gcyptE9rwOwf3Hd/k9N10kCQQCV

YsCjNidS81utEuGxVPy9IqWj1KswiWu6KD0BjK0KmAZD1swCxTBVV6c6iJwsqM4G

FNm68kZowkhYbc0X5KG1AkBp3Rqc46WBbpE5lj7nzhagYz5Cb/SbNLSp5AFh3W5c

sjsmYQXfVtw9YuU6dupFU4ysGgLBpvkf0iU4xtGOFvQJ

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

With these keys, Jeremy decides to send a message to Nadia. He uses her key and encrypts the following message: I love Bitcoin, which results in the following data:

EltHy0s1W1mZi4+Ypccur94pDRHw6GHYnwC+cDgQwa9xB3EggNGHfWBM8mCIOUV3iT1uIzD5dHJwSqLFQOPaHJCSp2/WTSXmWLohm5EAyMOwKv7M4gP3D/914dOBdpZyrsc6+aD/hVqRZfOQq6/6ctP5/3gX7GHrgqbrq/L7FFc=

Nobody can read this, except Nadia. Using the same algorithm, she inputs this data and her private key, and gets the following message:

I love Bitcoin.

We'll discuss more about this topic in Chapter 4, Cryptography and the Mechanics Behind Blockchain.

In this section, we are going to examine the data structures that are used in blockchains. We will be looking primarily at Ethereum, Bitcoin, and Bitshares blockchains to see key commonalities and differences.

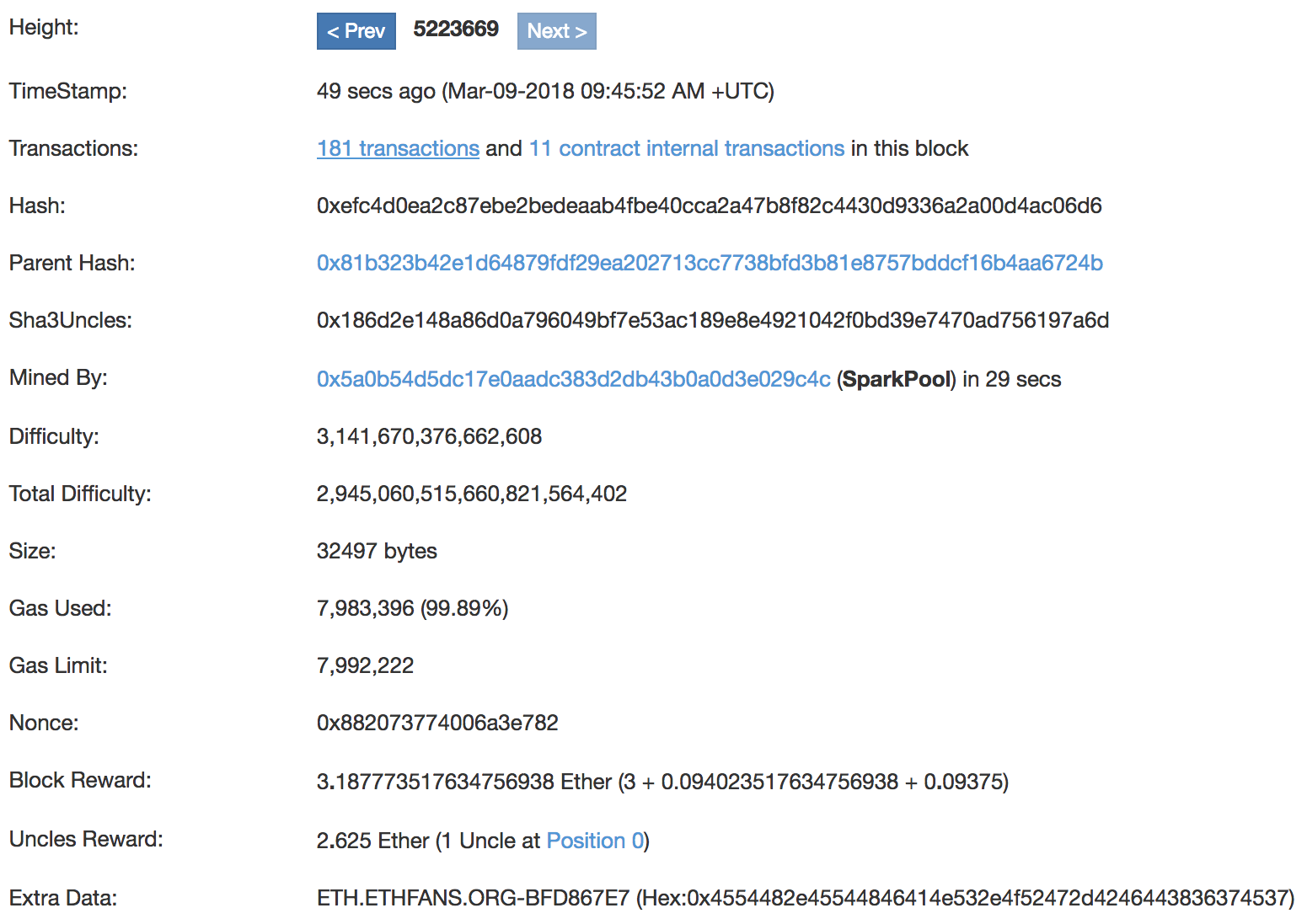

Here is the data from an example Ethereum block, from block 5223669:

If you remember, at the beginning of the chapter, we said there were three things common to blockchains: the reference to the prior block, the Hash of the transactions in the block, and network-specific metadata. In this block from the Ethereum network, all three are present. The reference to the prior block is contained by the block height and parent hash values. The Hash of the transactions is the hash entry, and the metadata is everything else, which will be network specific.

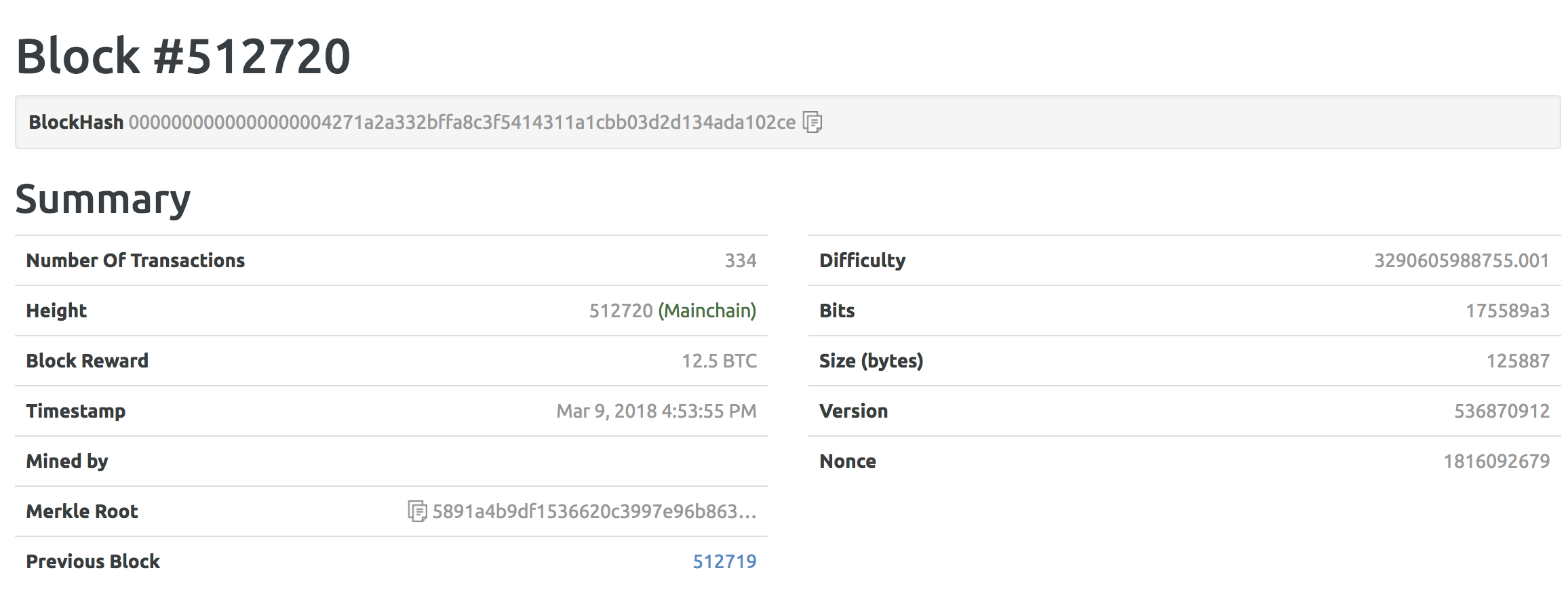

Here is a snapshot of a Bitcoin block:

Both Bitcoin and Ethereum are PoW chains; let's look now at a Proof of Stake (POS) ecosystem: Bitshares.

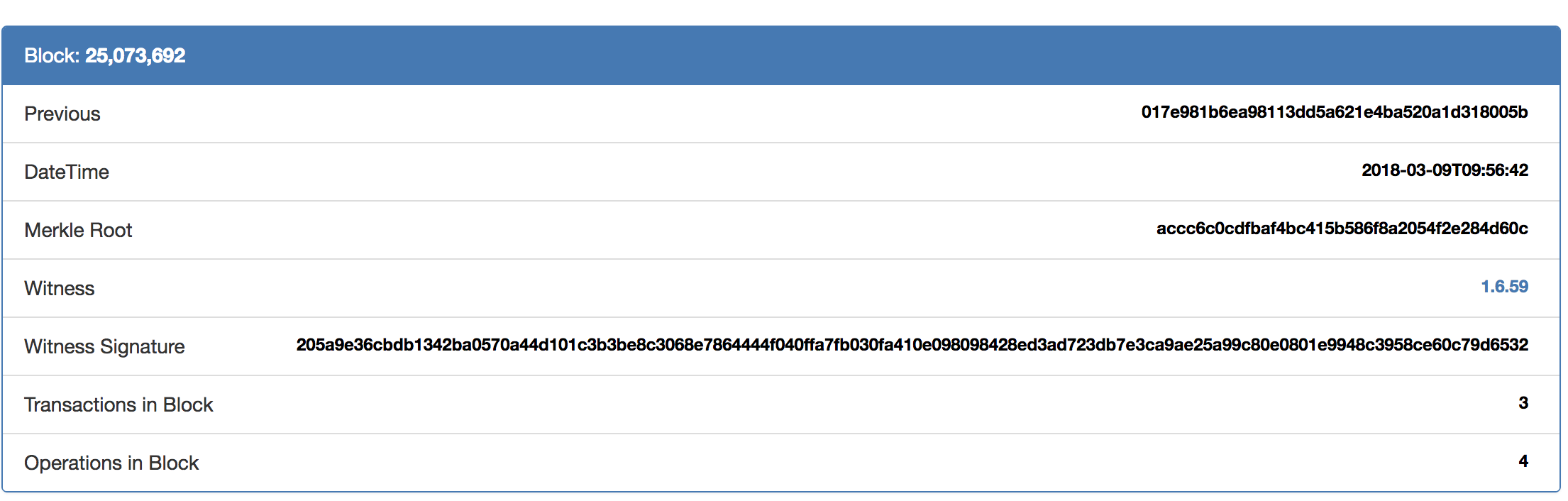

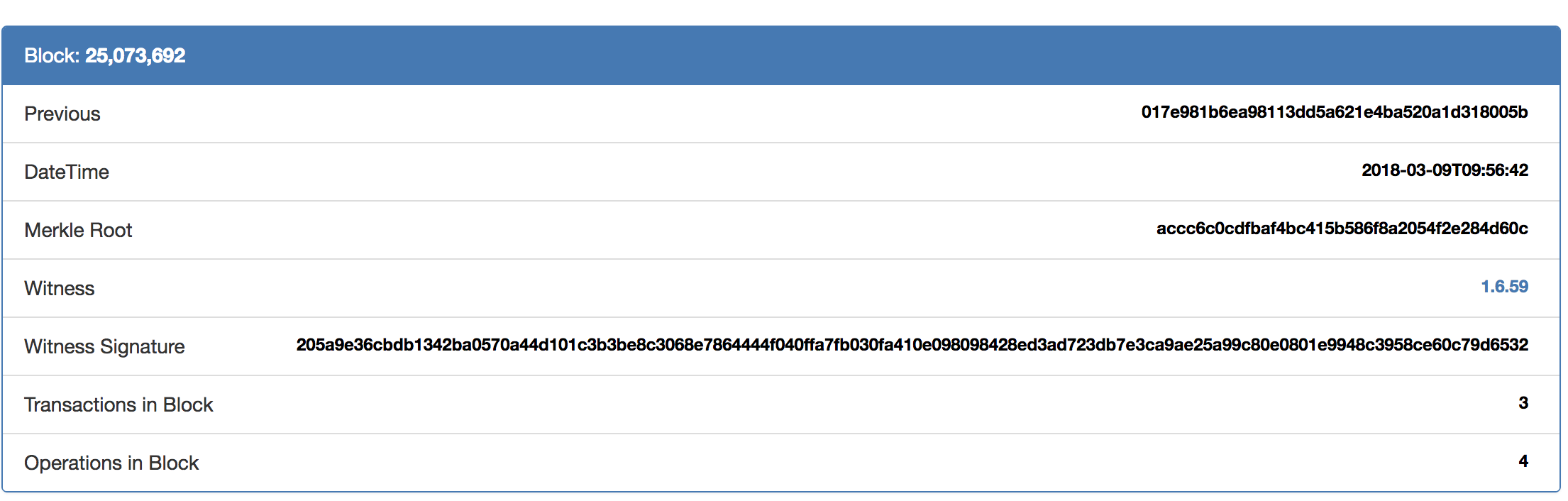

Here is some data from a Bitshares block:

Despite a radically different architecture, the fundamentals remain: references to a previous block, Merkle root, and network metadata. In Bitshares, you can also see that there is a Witness Signature. As a PoS blockchain, Bitshares has validators (they are called witnesses). Here, we see the witness and signature of the computer responsible for calculating this block.

One of the key properties of blockchain technology is that it can act as a trusted global state. There are many applications where a trusted global state is important but difficult, such as financial technology and logistics.

For instance, a few years ago, I ordered some camera equipment online. A few days later, I came home and was surprised to find that my equipment had arrived. I was so thankful that the expensive equipment sitting outside had not been stolen. It was only the next day that I received an email from the seller alerting me that the package had been shipped.

Here is a clear breakdown of the global state. The truth was that the camera was already on a truck, but neither I nor the shipper had that information stored properly. If the camera equipment had been stolen from my porch, it would have been very hard to discover what had happened.

If the seller, the logistics company, and I were all writing and reading data from a blockchain, this would have been impossible. When the logistics company registered the shipment, the state of the object would have changed, and both the seller and I would have known as soon as the next block was finalized.

As discussed before, each blockchain has a block time and a block size. Each network can have very different values and ways of handling block time. In Bitcoin, for instance, the block time is 10 minutes, while with Ethereum the block time is 20 seconds. In Stellar, the block time is about 4 seconds. These block times are determined by the code that runs the network. For networks such as Bitcoin, Litecoin, and Ethereum, the block time is actually an average. Because these are PoW networks, the block is finished once a miner solves the mining puzzle, which allows them to certify the block. In these networks, the difficulty of the puzzle is automatically adjusted so that on average the desired block time is reached.

The block size is the maximum amount of information that can be stored in each block. For Bitcoin, this is 1 MB of data's worth of transactions. For Ethereum, the limit is actually measured in GAS, a special unit of measuring both processing power (since Ethereum has smart contracts) as well as storage. Unlike Bitcoin, the GAS/storage limit for each block is not fixed but is instead adjusted by the miners dynamically.

It's important to note that blocks contain only possible information until they are finalized by the network. For instance, 1,000 transactions might happen, but if only 500 make it on to the next block, then only those 500 are real. The remaining transactions will continue to wait to be included in a future block.

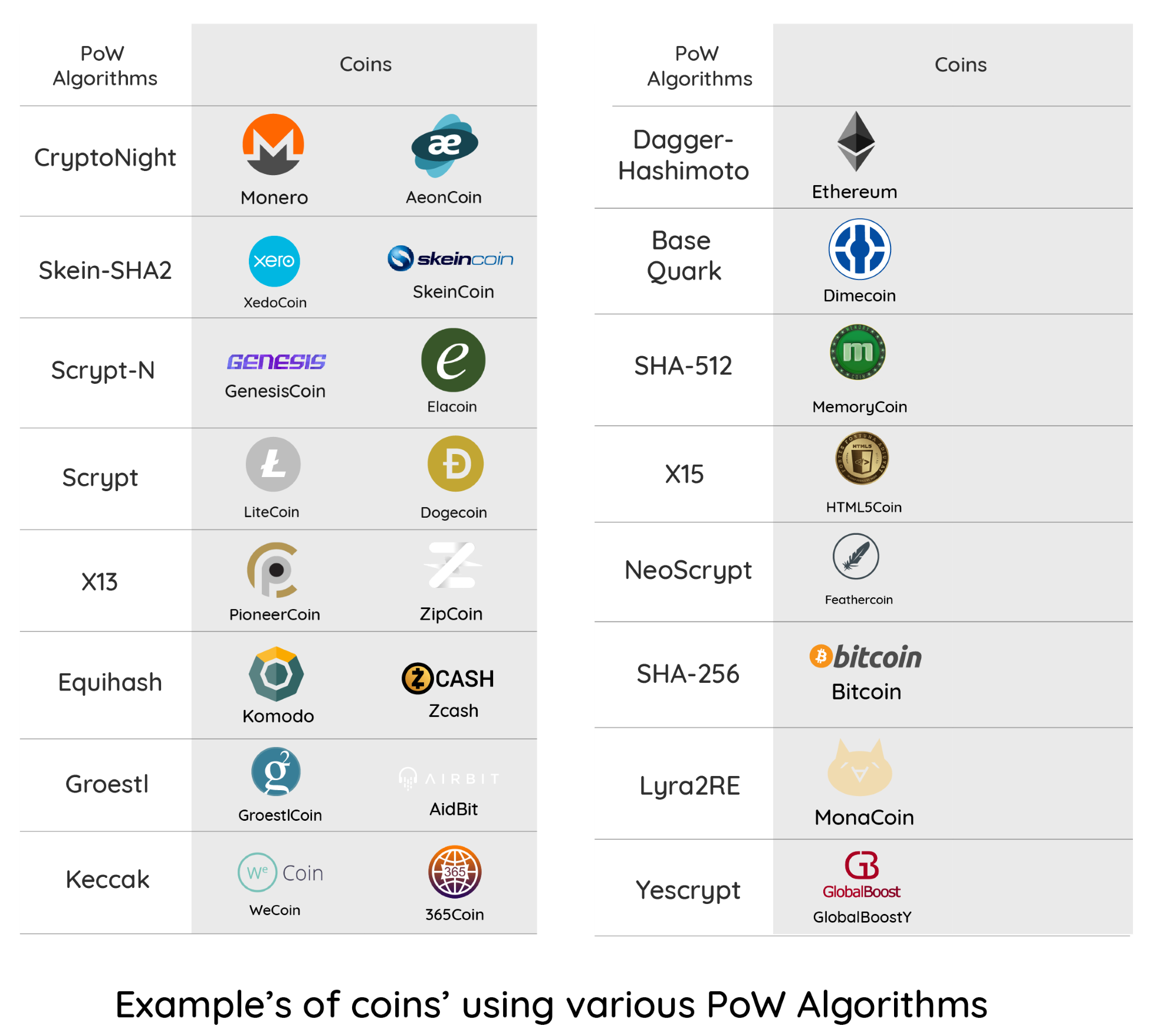

Blockchain miners and blockchain validators (see the upcoming sections) both have to do with consensus, which will be explored in depth in Chapter 7, Achieving Consensus. Generally, blockchain miners are associated with blockchains. A PoW chain functions by having the computers that are miners compete to do the work needed to certify a block in the chain. Currently, the only major PoW blockchains are Bitcoin, Litecoin, and Ethereum. Most other systems use a variation of PoS consensus, which we will discuss in the next Blockchain validators section. We'll cover how mining works in detail in Chapter 17, Mining.

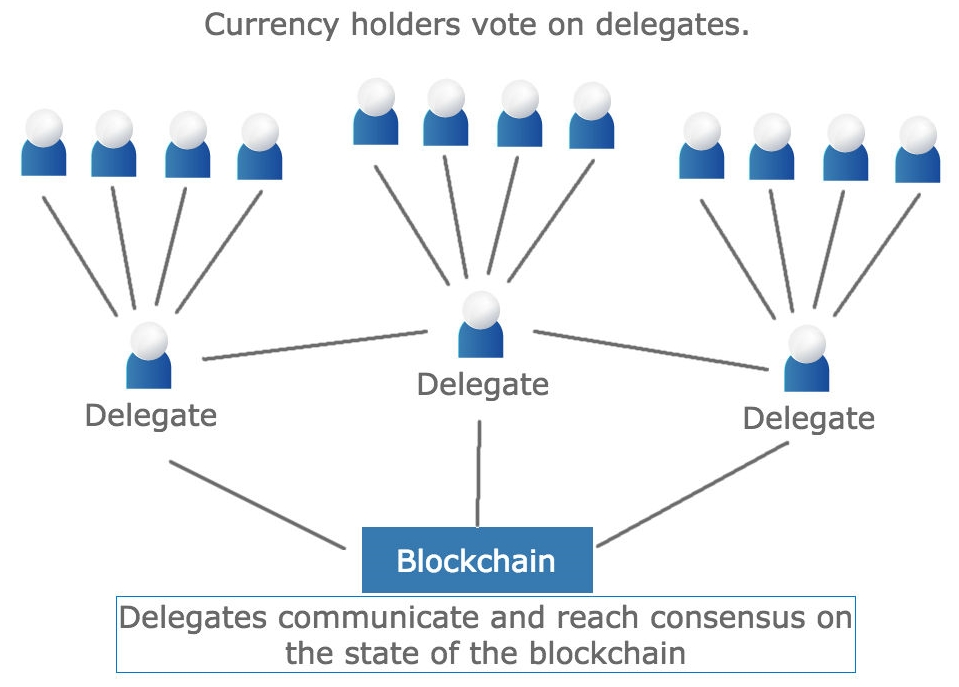

Blockchain validators are used by PoS systems. A PoS system works by requiring computers that wish to participate in the network to have stake—a large number of tokens—to assist in the blockchain. Unlike PoW algorithms, computers cannot join the network and expect to have any say in consensus. Rather, they must buy in through token ownership. Depending on the network, the naming convention for validators might be different. Tendermint has validators, Steemit and Bitshares have witnesses, Cardano has stakeholders, and so on. A validator is a computer with a positive stake (number of tokens) that is allowed to participate in the network and does so. Each chain has its own rules for how this works, and these will be covered more in-depth in Chapter 7, Achieving Consensus.

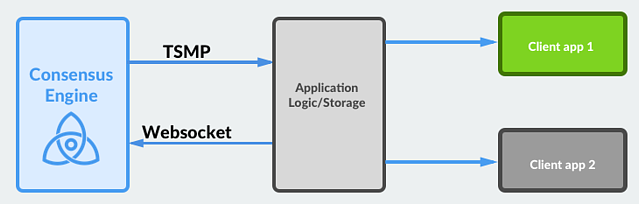

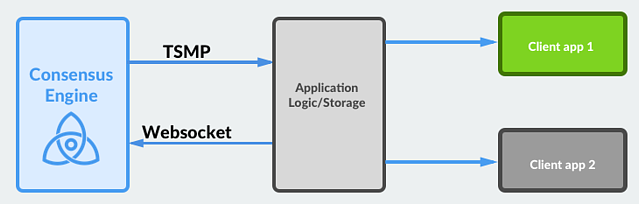

Some blockchains are said to have smart contracts when they are able to perform actions and behavior in response to changes to the chain. These will be covered in depth in Chapter 14, Smart Contracts and Chapter 16, Decentralized Applications.

One ongoing concern for blockchain systems is performance. Public blockchains are global systems, with their system resources shared by all the users in the world simultaneously. With such a large user base, resource constraints are a real concern and have already caused real problems. For instance, a popular game called CryptoKitties was launched on Ethereum and caused the network to become congested. Other applications became nearly unusable, as the load from CryptoKitties overwhelmed the network.

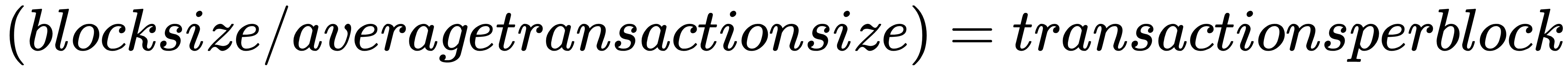

The quick and dirty way of calculating the throughput of a blockchain is as follows:

For Bitcoin, the transaction throughput is about 7tx/second. This is because of the relatively small block and the very long block time. Ethereum has short block times but very tiny blocks and ends up at about 14tx/second. Blockchains such as Stellar, Bitshares, and Waves can reach speeds of over, 1000tx/second.

VISA is the premier payment-processing network worldwide. In one of the company's blogs, it was revealed that VISA can process over 40,000 transactions a second. This is peak capacity, and it usually processes nowhere near that, except around times such as Christmas. Nevertheless, it should be clear that blockchains have a way to go before they can compete for processing global payments on the same scale as VISA. Newer networks, such as EOS and COSMOS, are trying, however, with innovative multi-threaded designs and segmented blockchain zones.

Now you should understand the basic components of a blockchain. Blocks are groups of transactions grouped together and act as the fundamental unit of a blockchain. Miners are computers that create new blocks on PoW blockchains. Validators, also called witnesses and other names, are computers that create blocks on PoS blockchains. Digital signatures are composed of public and private keys and use mathematics to prove the author of the data.

The key idea of hashing is to use a mathematical function that maps arbitrary data to a single, simple to deal with value. Any change to the data will make the end value very different

In the next chapter, we will learn what these systems are and how blockchain counts as both. We will learn how to differentiate between the two systems and why these concepts are so important to blockchain.

One of the biggest misconceptions in the blockchain space is between distributed systems and decentralized systems. In this chapter, we are going to discuss both types of systems, why they matter, their similarities, their differences, and how blockchain technology can fit into both categories.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

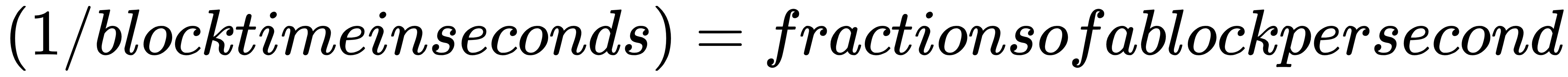

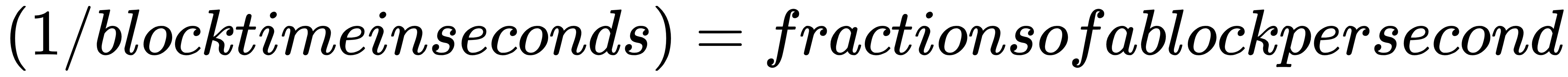

A distributed system is one in which the application and its architecture are distributed over a large number of machines and preferably physical locations. More simply, a distributed system is one where the goal of the system is spread out across multiple sub-systems in different locations. This means that multiple computers in multiple locations must coordinate to achieve the goals of the overall system or application. This is different than monolithic applications, where everything is bundled together.

Let's take the example of a simple web application. A basic web application would run with processing, storage, and everything else running on a single web server. The code tends to run as a monolith—everything bundled together. When a user connects to the web application, it accepts the HTTP request, uses code to process the request, accesses a database, and then returns a result.

The advantage is that this is very easy to define and design. The disadvantage is that such a system can only scale so much. To add more users, you have to add processing power. As the load increases, the system owner cannot just add additional machines because the code is not designed to run on multiple machines at once. Instead, the owner must buy more powerful and more expensive computers to keep up. If users are coming from around the globe, there is another problem—some users who are near the server will get fast responses, whereas users farther away will experience some lag. The following diagram illustrates a single, monolithic code base building to a single artifact:

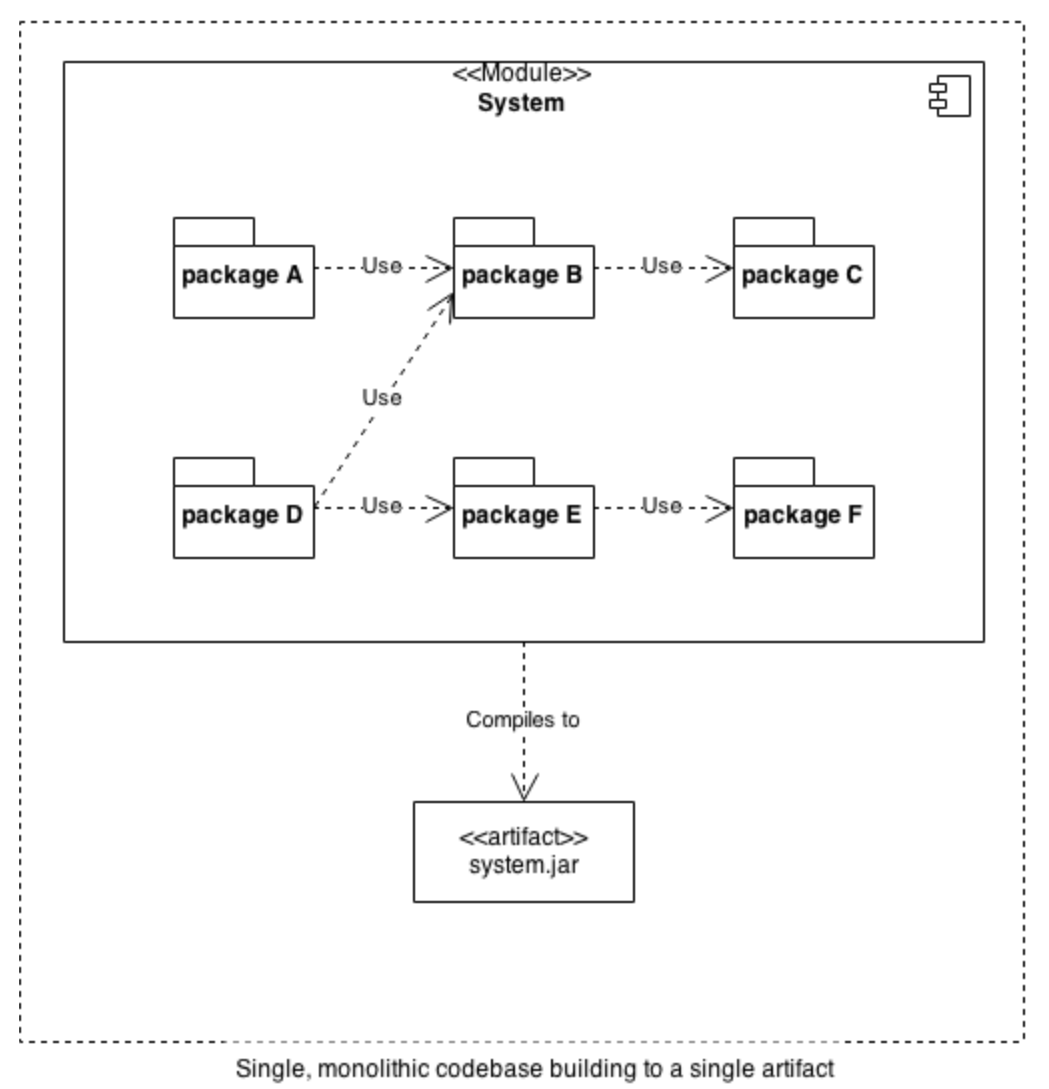

What happens if the computer running this application has a fault, a power outage, or is hacked? The answer is that the entire system goes down entirely. For these reasons, businesses and applications have become more and more distributed. Distributed systems typically fall into one of several basic architectures: client–server, three-tier, n-tier or peer-to-peer. Blockchain systems are typically peer-to-peer, so that is what we will discuss here.

The advantages of a distributed system are many, and they are as follows:

Resiliency is the ability of a system to adapt and keep working in response to changes and challenges. Resiliency can only be discussed in the context of the types of events that a system is resilient towards. A system might be resilient to a few computers getting turned off but may not be resilient to nuclear war.

Resiliency can be broken down into different sub-categories:

We will now discuss fault tolerance in more detail.

A system is said to be fault tolerant when it is capable of operating even if some of the pieces fail or malfunction. Typically, fault tolerance is a matter of degree: where the level of sub-component failure is either countered by other parts of the system or the degradation is gradual rather than an absolute shutdown. Faults can occur on many levels: software, hardware, or networking. A fault tolerant piece of software needs to continue to function in the face of a partial outage along any of these layers.

In a blockchain, fault tolerance on the individual hardware level is handled by the existence of multiple duplicate computers for every function—the miners in bitcoin or proof of work systems or the validators in PoS and related systems. If a computer has a hardware fault, then either it will not validly sign transactions in consensus with the network or it will simply cease to act as a network node—the others will take up the slack.

One of the most important aspects of blockchain is the concept of consensus. We will discuss the different ways blockchains achieve consensus in Chapter 7, Achieving Consensus. For now, it is enough to understand that most blockchain networks have protocols that allow them to function as long as two thirds to slightly over one-half of the computers on the network are functioning properly, though each blockchain network has different ways of ensuring this which will be covered in future chapters.

In most blockchains, each computer acting as a full participant in the network holds a complete copy of all transactions that have ever happened since the launch of the network. This means that even under catastrophic duress, as long as a fraction of the network computers remains functional, a complete backup will exist.

In PoS chains, there tend to be far fewer full participants so the number of backups and distribution is far less. So far, this reduced level of redundancy has not been an issue.

As discussed in prior chapters, hashing and the Merkle root of all transactions and behaviors on the blockchain allow for an easy calculation of consistency. If consistency is broken on a blockchain, it will be noticed instantly. Blockchains are designed to never be inconsistent. However, just because data is consistent does not mean it is accurate. These issues will be discussed in Chapter 20, Scalability and Other Challenges.

Most computer systems in use today are client–server. A good example is your web browser and typical web applications. You load up Google Chrome or another browser, go to a website, and your computer (the client) connects to the server. All communication on the system is between you and the server. Any other connections (such as chatting with a friend on Facebook) happen with your client connected to the server and the server connected to another client with the server acting as the go-between.

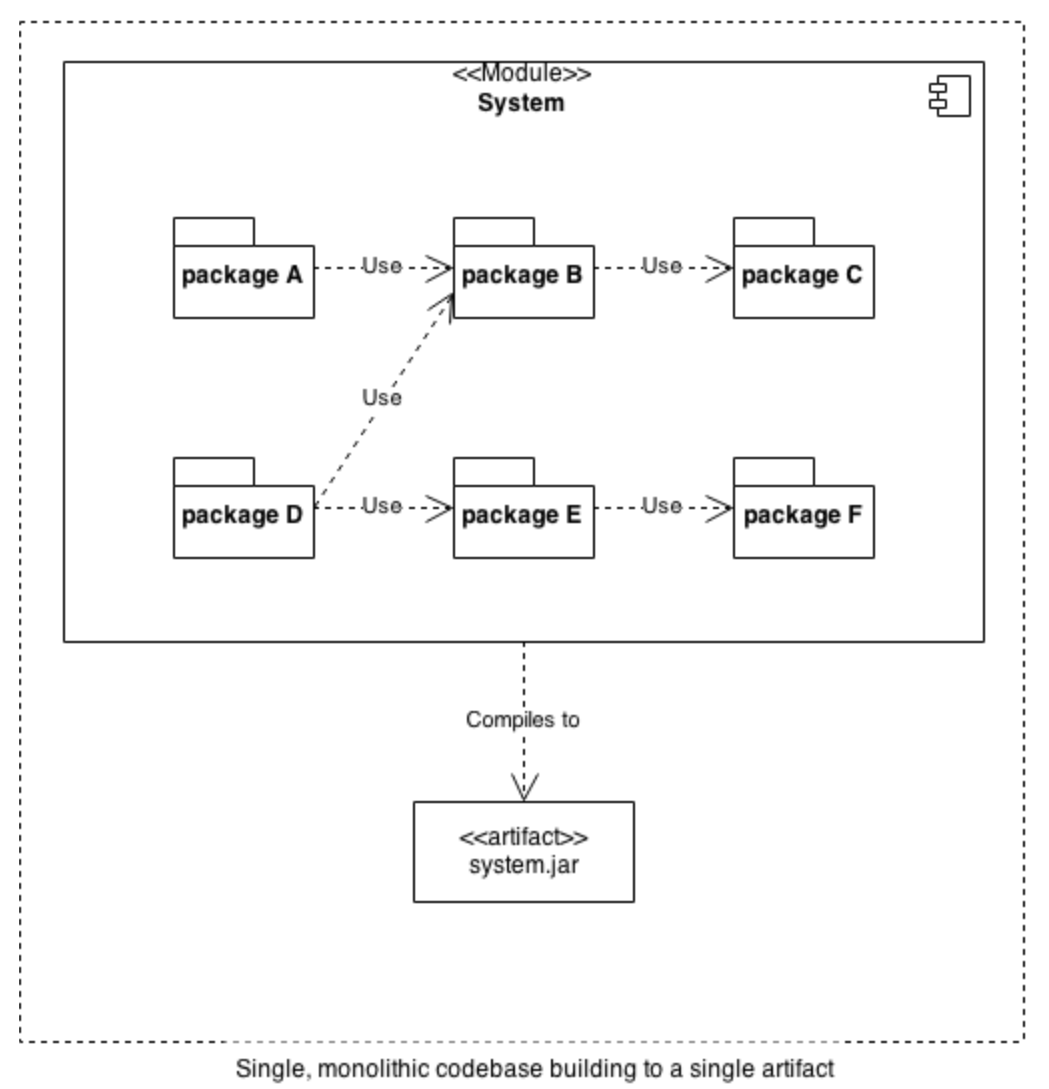

Peer-to-peer systems are about cutting out the server. In a peer-to-peer system, your computer and your friend's computer would connect directly, with no server in between them.

The following is a diagram that illustrates the peer-to-peer architecture:

All decentralized systems must be distributed. But distributed systems are not necessarily decentralized. This is confusing to many people. If a distributed system is one spread across many computers, locations, and so on, how could it be centralized?

The difference has to do with location and redundancy versus control. Centralization in this context has to do with control. A good example to showcase the difference between distributed and decentralized systems is Facebook. Facebook is a highly distributed application. It has servers worldwide, running thousands of variations on its software for testing. Any of its data centers could experience failure and most of the site functionality would continue. Its systems are distributed with fault tolerance, extensive coordination, redundancy, and so on.

Yet, those services are still centralized because, with no input from other stakeholders, Facebook can change the rules. Millions of small businesses use and depend on Facebook for advertising. Groups that have migrated to Facebook could suddenly find their old messages, work, and ability to connect revoked—with no recourse. Facebook has become a platform others depend on but with no reciprocal agreement of dependability. This is a terrible situation for all those groups, businesses, and organizations that depend on the Facebook platform in part or on the whole.

The last decade has brought to the forefront a large number of highly distributed yet highly centralized platform companies —Facebook, Alphabet, AirBnB, Uber, and others—that provide a marketplace between peers but are also almost completely unbeholden to their users. Because of this situation, there is a growing desire for decentralized applications and services. In a decentralized system, there is no central overwhelming stakeholder with the ability to make and enforce rules without the permission of other network users.

Like distributed systems, decentralization is a sliding scale more than an absolute state of being. To judge how decentralized a system is, there are a number of factors to consider. We're going to look at factors that have particular relevance to blockchain and decentralized applications and organizations. They are the following:

By definition, any system that is practically or logically closed will be at least somewhat centralized. A system that is closed is automatically centralized to the pre-existing actors. As with all other aspects of decentralized systems, this is not a binary yes/no but more of a sliding scale of possibility.

The early internet was seen as revolutionary in part because of its open access nature and the ability for anyone (with a computer, time, and access) to get online and begin trading information. Similarly, blockchain technologies have so far been open for innovation and access.

A hierarchical system is the one commonly found within companies and organizations. People at the top of a hierarchy have overwhelming power to direct resources and events. A hierarchy comes in different extremes. At one extreme, you could have a system wherein a single arbiter holds absolute power. At the other extreme, you could have a system where each member of the system holds identical direct power and therefore control exists through influence, reputation, or some other form of organizational currency.

In blockchain, a few forms of non-hierarchical patterns have emerged. The first is in proof-of-work mining systems. All miners are fundamentally equal participants in the blockchain, but their influence is proportional to the computing resources they make available to the network.

In PoS blockchain systems, the power is distributed based on the level of investment/stake in the protocol of a specific. In this case, decentralization is achieved both through mass adoption as well as competition with other chains. If one chain becomes too centralized, nothing stops users from migrating to a different one.

How decentralized these systems will remain over time is an open question.

Open access naturally leads to another trait of decentralized systems: diversity. A diverse system stands in opposition to monoculture. In technology, a monoculture is the overwhelming prevalence of a single system, such as the dominance of Windows, which persisted for a long time in corporate America.

One of the ways power can be centralized in a system is through information dominance, where one set of actors in a system has access to more or greater information than other actors. In most current blockchain technology, each participant on the chain gets the same amount of information. There are some exceptions. Hyperledger Fabric, for instance, has the capacity to have information hiding from participants.

The ability to have perfectly enforced transparency is one of the drivers of interest in blockchain systems. By creating transparent and unforgettable records, blockchain has an obvious utility for logistics and legal record keeping. With records on a blockchain, it is possible to know for certain that data was not altered. A transparent blockchain also ensures a level of fairness—participants can all be sure that at a minimum there is a shared level of truth available to all which will not change.

Decentralized systems are not without their downsides. Here are a few key issues with decentralized systems that have specific relevance to blockchain:

Centralized systems and decentralized systems tend to be faster or slower at dealing with certain types of events. Blockchains are decentralized systems of record keeping. One way to think about a basic blockchain such as bitcoin is that it is an append-only database. Bitcoin can handle approximately seven transactions a second. By comparison, Visa and MasterCard are distributed (but not decentralized) transaction-handling systems that can handle more than 40,000 transactions a second. Blockchain systems continue to increase in speed but typically at with the trade-off of some amount of centralization or restrictions on access. Some PoS systems such as Tendermint or Waves have a theoretical throughput of over 1,000 tx/second but are still far from the peak capacity of their traditional counterparts.

Decentralized systems tend to be much harder to censor because of a lack of a central authority to do the censoring. For free-speech and free-information purists, this is not seen as a downside in the slightest. However, some information (child pornography, hate speech, bomb-making instructions) is seen as dangerous or immoral for public dissemination and therefore should be censored. As a technology, anything actually written into the blockchain is immutable once the block holding that information is finished. For instance, Steemit is a blockchain-based social blogging platform where each post is saved to the chain. Once each block is finalized, the data cannot be removed. Clients of the system could choose not to show information, but the information would still be there for those who wanted to look.

The desire for censorship extends to self-censorship. Content written to the change is immutable—even for its author. For instance, financial transactions done via bitcoin can never be hidden from authorities. While bitcoin is anonymous, once a person is attached to a bitcoin wallet, it is possible to easily track every transaction ever done since the beginning of the blockchain.

Because of this, a blockchain-based national currency would allow perfect taxation—due to perfect financial surveillance of the chain. Censorship resistance is thus a double-edged sword.

Decentralized systems tend to be much more chaotic than centralized ones by their nature. In a decentralized system, each actor works according to their own desires and not the demands of an overarching authority. Because of this, decentralized systems are difficult to predict.

In this chapter, we have discussed the difference between distributed systems and decentralized systems and gone over some of the key features. You should now understand how each decentralized system is also a distributed system and some of the key aspects of each concept.

In the next chapter, we will start looking at how these things work in practice.

The use of blockchain hinges on cryptography. Numeric cryptography can be regarded as a recent invention, with the ciphers of the past relying on exchanging words for words and letters for letters. As we'll see, modern cryptography is a very powerful tool for securing communications, and, importantly for our topic, determining the provenance of digital signatures and the authenticity of digital assets.

In this chapter, the following topics will be covered:

Cryptography safeguards the three principles of information security, which can be remembered by the mnemonic device Central Intelligence Agency (CIA):

Confidentiality: Ensures that information is shared with the appropriate parties and that sensitive information (for example, medical information, some financial data) is shared exclusively with the consent of appropriate parties.

Integrity: Ensures that only authorized parties can change data and (depending on the application) that the changes made do not threaten the accuracy or authenticity of the data. This principle is arguably the most relevant to blockchains in general, and especially the public blockchains.

Availability: Ensures authorized users (for example, holders of tokens) have the use of data or resources when they need or want them. The distributed and decentralized nature of blockchain helps with this greatly.

The relevance to blockchain and cryptocurrency is immediately evident: if, for instance, a blockchain did not provide integrity, there would be no certainty as to whether a user had the funds or tokens they were attempting to spend. For the typical application of blockchain, in which the chain may hold the chain of title to real estate or securities, data integrity is very important indeed. In this chapter, we will discuss the relevance of these principles to blockchain and how things such as integrity are assured by cryptography.

Cryptography is the term for any method or technique used to secure information or communication, and specifically for the study of methods and protocols for secure communication. In the past, cryptography was used in reference to encryption, a term that refers to techniques used to encode information.

At its most basic, encryption might take the form of a substitution cipher, in which the letters or words in a message are substituted for others, based on a code shared in advance between the parties. The classic example is that of the Caesar Cipher, in which individual letters are indexed to their place in the alphabet and shifted forward a given number of characters. For example, the letter A might become the letter N, with a key of 13.

This specific form of the Caesar Cipher is known as ROT13, and it’s likely the only substitution cipher that continues to see any regular use—it provides a user with a trivially reversible way of hiding expletives or the solutions to puzzles on static websites (the same, of course, could be implemented very simply in JavaScript).

This very simple example introduces two important concepts. The first is an algorithm, which is a formal description of a specific computation with predictable, deterministic results. Take each character in the message and shift it forward by n positions in the alphabet. The second is a key: the n in that algorithm is 13. The key in this instance is a pre-shared secret, a code that the two (or more) parties have agreed to, but, as we’ll see, that is not the only kind of key.

Cryptography is principally divided into symmetric and asymmetric encryption. Symmetric encryption refers to encryption in which the key is either pre-shared or negotiated. AES, DES, and Blowfish are examples of algorithms used in symmetric encryption.

Most savvy computer users are familiar with WEP, WPA, or WPA2, which are security protocols employed in Wi-Fi connections. These protocols exist to prevent the interception and manipulation of data transmitted over wireless connections (or, phrased differently, to provide confidentiality and integrity to wireless users). Routers now often come with the wireless password printed on them, and this is a very literal example of a pre-shared key.

The algorithms used in symmetric encryption are often very fast, and the amount of computational power needed to generate a new key (or encrypt/decrypt data with it) is relatively limited in comparison to asymmetric encryption.

Asymmetric cryptography (also called public-key cryptography) employs two keys: a public key, which can be shared widely, and a private key, which remains secret. The public key is used to encrypt data for transmission to the holder of the private key. The private key is then used for decryption.

The development of public-key cryptography enabled things such as e-commerce internet banking to grow and supplement very large segments of the economy. It allowed email to have some level of confidentiality, and it made financial statements available via web portals. It also made electronic transmissions of tax returns possible, and it made it possible for us to share our most intimate secrets in confidence with, maybe, perfect strangers—you might say that it brought the whole world closer together.

As the public key does not need to be held in confidence, it allows for things such as certificate authorities and PGP key servers—publishes the key used for encryption, and only the holder of the private key will be able to decrypt data encrypted with that published key. A user could even publish the encrypted text, and that approach would enjoy some anonymity—putting the encrypted text in a newsgroup, an email mailing list, or a group on social media would cause it to be received by numerous people, with any eavesdropper unable to determine the intended recipient. This approach would also be interesting in the blockchain world—thousands or millions of nodes mirroring a cipher text without a known recipient, perhaps forever, irrevocably, and with absolute deniability on the part of the recipient.

Public-key cryptography is more computationally expensive than symmetric cryptography, partly due to the enormous key sizes in use. The NSA currently requires a key size of 3,072 bits or greater in commercial applications for key establishment, which is the principal use of public-key cryptography. By comparison, 128-bit encryption is typically regarded as adequate for most applications of cryptography, with 256-bit being the NSA standard for confidentiality.

For the most part, although it is possible to use the public-key algorithm alone, the most common use of public-key cryptography is to negotiate a symmetric key for the remainder of the session. The symmetric key in most implementations is not transmitted, and, as a consequence, if an attacker were to seize one or both of the private keys, they would be unable to access the actual communications. This property is known as forward secrecy.

Some protocols, such as SSH, which is used to remotely access computers, are very aggressive. Over the course of a session, SSH will change the key at regular intervals. SSH also illustrates the essential property of public-key cryptography—it’s possible to put your public key on the remote server for authentication, without any inherent confidentiality issue.

Most cryptography in use today is not unbreakable, given extremely large (or infinite) computing resources. However, an algorithm suited to the task of protecting data where confidentiality is required is said to be computationally improbable—that is, computing resources to crack the encryption do not exist, and are not expected to exist in the near future.

It is notable that, although when encrypting data to send it to a given recipient, the private key is used for decryption, it is generally possible to do the reverse. For cryptographic signing, private keys are used to generate a signature that can be decrypted (verified) with the public key published for a given user. This inverted use of public-key cryptography allows for users to publish a message in the clear with a high degree of certainty that the signer is the one who wrote it. This again invokes the concept of integrity—if signed by the user’s private key, a message (or transaction) can be assumed to be authentic. Typically, where Blockchains are concerned, when a user wishes to transfer tokens, they sign the transaction with the private key of the wallet. The user then broadcasts that transaction.

It is now also fairly common to have multisignature wallets, and, in that instance, a transaction is most often signed by multiple users and then broadcast, either in the web interface of a hosted wallet service, or in a local client. This is a fairly common use case with software projects with distributed teams.

Distinct from the concept of encryption (and present in many mechanisms used in cryptography, such as cryptographic signatures and authentication) is hashing, which refers to a deterministic algorithm used to map data to a fixed-size string. Aside from determinism, cryptographic hashing algorithms must exhibit several other characteristics, which will be covered in this section.

As we'll see in the following section, a hash function must be difficult to reverse. Most readers who got through high school algebra will remember being tormented with factoring. Multiplication is an operation that is easy to complete, but difficult to reverse—it takes substantially more effort to find the common factors of a large number as opposed to creating that number as a product of multiplication. This simple example actually enjoys the practical application. Suitably large numbers that are the product of the multiplication of two prime numbers—called semiprimes or (less often) biprimes—are employed in RSA, a widely used public-key cryptography algorithm.

RSA is the gold standard in public key cryptography, enabling things such as SSH, SSL, and systems for encrypting email such as PGP. Building on operations such as this — easy to do one way and very hard to do in the other—is what makes cryptography so robust.

A desirable feature of robust hashing algorithms is known as the avalanche effect. A small change in the input should result in a dramatic change in the output. Take for instance the following three examples using output redirection and the GNU md5sum utility present in most distributions of Linux:

$ echo "Hills Like White Elephants by Ernest Hemingway" | md5sum

86db7865e5b6b8be7557c5f1c3391d7a -

$ echo "Bills Like White Elephants by Ernest Hemingway" | md5sum

ccba501e321315c265fe2fa9ed00495c -

$ echo "Bills Like White Buffalo by Ernest Hemingway"| md5sum

37b7556b27b12b55303743bf8ba3c612 -

Changing a word to an entirely different word has the same result as changing a single letter: each hash is entirely different. This is a very desirable property in the case of, say, password hashing. A malicious hacker cannot get it close enough and then try permutations of that similar password. We will see in the following sections, however, that hashes are not perfect.

An ideal hash function is free of collisions. Collisions are instances in which two inputs result in the same output. Collisions weaken a hashing algorithm, as it is possible to get the expected result with the wrong input. As hashing algorithms are used in the digital signatures of root certificates, password storage, and blockchain signing, a hash function having many collisions could allow a malicious hacker to retrieve passwords from password hashes that could be used to access other accounts. A weak hashing algorithm, rife with collisions, could aid in a man-in-the-middle attack, allowing an attacker to spoof a Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) certificate perfectly.

MD5, the algorithm used in the above example, is regarded as inadequate for cryptographic hashing. Blockchains thankfully largely use more secure hash functions, such as SHA-256 and RIPEMD-160.

In the PoW systems, new entries to a blockchain require hashes to be computed. In Bitcoin, miners must compute two SHA-256 hashes on the current transactions in the block—and included therein is the hash of the previous block.

This is pretty straightforward for a hashing algorithm. Let’s briefly reiterate: an ideal hash function takes the expected input and then outputs a unique hash. It is deterministic. There is only one possible output and it is impossible (or computationally improbable) to achieve that output with a different input. These properties ensure that miners can process a block and that each miner can return the same result. It is through hashing that Blockchains attain two properties that are crucial to their adoption and current popularity: decentralization and immutability.