Copyright © 2015 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: November 2015

Production reference: 1241115

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78588-998-1

Author

Chelsea Myers

Reviewers

Esteban S. Abait

Tristan Denyer

Christopher Scott Hernandez

J. Pedro Ribeiro

Marija Zaric

Commissioning Editor

Kartikey Pandey

Acquisition Editor

Kirk D'costa

Content Development Editor

Merwyn D'souza

Technical Editor

Siddhi Rane

Copy Editor

Janbal Dharmaraj

Project Coordinator

Neha Bhatnagar

Proofreader

Safis Editing

Indexer

Priya Sane

Production Coordinator

Komal Ramchandani

Cover Work

Komal Ramchandani

Chelsea Myers, throughout her career so far, has been a student, freelancer, full-time employee, teacher, assistant, researcher, and business owner in the web development industry. She is passionate about responsive frontend development and building out user-focused designs. Every new project allows her to learn and try something new. And to her, that's the best part of the job.

She graduated from Drexel University with a degree in digital media. Currently, she works for an award-winning digital studio, Happy Cog, and teaches web development and user experience at Drexel. When she is not doing all this, or freelancing herself, she also manages her cofounded animation studio, Coffeebot Studios.

Esteban S. Abait is a senior software architect, and a former PhD student. He has experience devising the architecture of complex software products, and planning its development. He has worked both onsite, and offshore for clients such as Cisco, Intuit, and SouthWest. During his career he has worked with different technologies such as Java, PHP, Ruby, and Node.js, among others. In recent years, his main interests revolve around web mobile and REST APIs. He has developed large, maintainable web applications using JavaScript. In addition, he has worked assessing clients on REST best practices. At the same time, he has worked on high traffic web sites, where topics such as replication, sharding, or distributed caches are key to scalability.

He is currently working at Globant as a technical director. In this role, he works to ensure the project's delivery meet their deadlines with the best quality. He also designs software program training and interviews software developers. In addition, he travels to clients to provide consultancy on web technologies.

Globant (http://www.globant.com/) is a new breed of technology service providers focused on delivering innovative software solutions by leveraging emerging technologies and trends. Globant combines the engineering and technical rigor of IT service providers with the creative and cultural approach of digital agencies. Globant is the place where engineering, design, and innovation meet scale.

Tristan Denyer is a UX designer for web and mobile applications, including web apps and portals, e-commerce, online video players and widgets, games (online, iPhone, board), marketing sites, and more. He is also a UI developer and WordPress theme developer. He is currently leading the UX design for the product team at a start-up in San Francisco. He recently wrote a book, A Practical Handbook to WordPress Themes, CreateSpace, to help owners and operators of self-hosted WordPress websites get the most out of their themes. His passions include prototyping, web security, writing, carpentry, and burritos. He can be contacted through Twitter (@tristandenyer), GitHub (https://github.com/tristandenyer), and his portfolio and blog (http://tristandenyer.com/).

Christopher Scott Hernandez is a designer turned developer who has been working on the Web since 1996, when he built the Web's first boat upholstery site for his dad. He's since moved on to bringing his expertise to companies small and large, having worked on some of the most visited sites in the world, including eBay, LinkedIn, and Apple.

He was also a technical reviewer for HTML5 Multimedia Development Cookbook, Packt Publishing. He is an avid reader and lover of books. When he's not pushing pixels and writing code, he enjoys spending time with his wife and daughter exploring the parks and trails of beautiful Austin, Texas.

J. Pedro Ribeiro is a Brazilian user interface engineer living in the heart of London. He has been working on the Web for several years coding websites for start-ups and large companies. Currently, at RetailMeNot UK, he is responsible for creating the mobile first experience at VoucherCodes.co.uk (http://vouchercodes.co.uk/), focusing on performance and usability.

On his personal site, http://jpedroribeiro.com, he writes about frontend technologies, books, and personal projects. Some of these projects and experiments can be found at http://github.com/jpedroribeiro. On Twitter, he can be found at twitter.com/jpedroribeiro.

Marija Zaric is a web designer living in Belgrade with a focus on individual and commercial clients that demand websites that are clear, modern, creative, simple, and responsive. She works with clients from the USA and all over the world, helping them to present their services in a unique yet professional way.

She is a relentless learner. What she loves most about web design are the constant changes in the field, especially its evolution in the last four years when she got inspired by simplicity, great images, typography, and the possibility to optimize a single website for various devices.

She designed and incorporated these styles into her own website and called it Creative Simplicity. She was a reviewer for the books Responsive Media in HTML5 and Responsive Web Design with HTML5 and CSS3, both by Packt Publishing.

Her projects can be found at http://www.marijazaric.com/.

For support files and downloads related to your book, please visit www.PacktPub.com.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at <service@packtpub.com> for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

https://www2.packtpub.com/books/subscription/packtlib

Do you need instant solutions to your IT questions? PacktLib is Packt's online digital book library. Here, you can search, access, and read Packt's entire library of books.

If you have an account with Packt at www.PacktPub.com, you can use this to access PacktLib today and view 9 entirely free books. Simply use your login credentials for immediate access.

Websites come in varying shapes and sizes. In our lifetime, we may work on sites that have four or 400 different pages. And the devices these websites are viewed on are just as different. Creating websites for all these variables is a daunting task. Breaking sites down to bite-sized pieces, or patterns, can make this task more manageable.

Web design and development is a great industry to be a part of because the people in it love to share. When developing a responsive website, it can be a challenge to come up with solutions for scaling content from small to large screens. Luckily, we can look to responsive patterns and responsive pattern libraries shared by the companies and individuals that make up this industry.

Together, let's look at the most popular responsive web design patterns and how they are built. Responsive patterns, just like patterns in the analog world, can be used as a guide, a foundation, or solely inspiration for your own work.

Chapter 1, Creating a Home for Responsive Patterns, builds a home for all the patterns reviewed in this book and looks into why pattern libraries should be used in the first place.

Chapter 2, The Main Stage – Building Responsive Layouts, reviews the top most common responsive layouts and what type of content is suited for each.

Chapter 3, Make Way for Responsive Navigations, explores patterns for one of the most tricky aspects of a responsive website—the menu system. It looks at popular navigational patterns used in modern websites and the pros and cons of each.

Chapter 4, From Static to Dynamic – Embedding Media, shows how to deliver catered images for different quality displays and how to make media such as images and video scale with a responsive website.

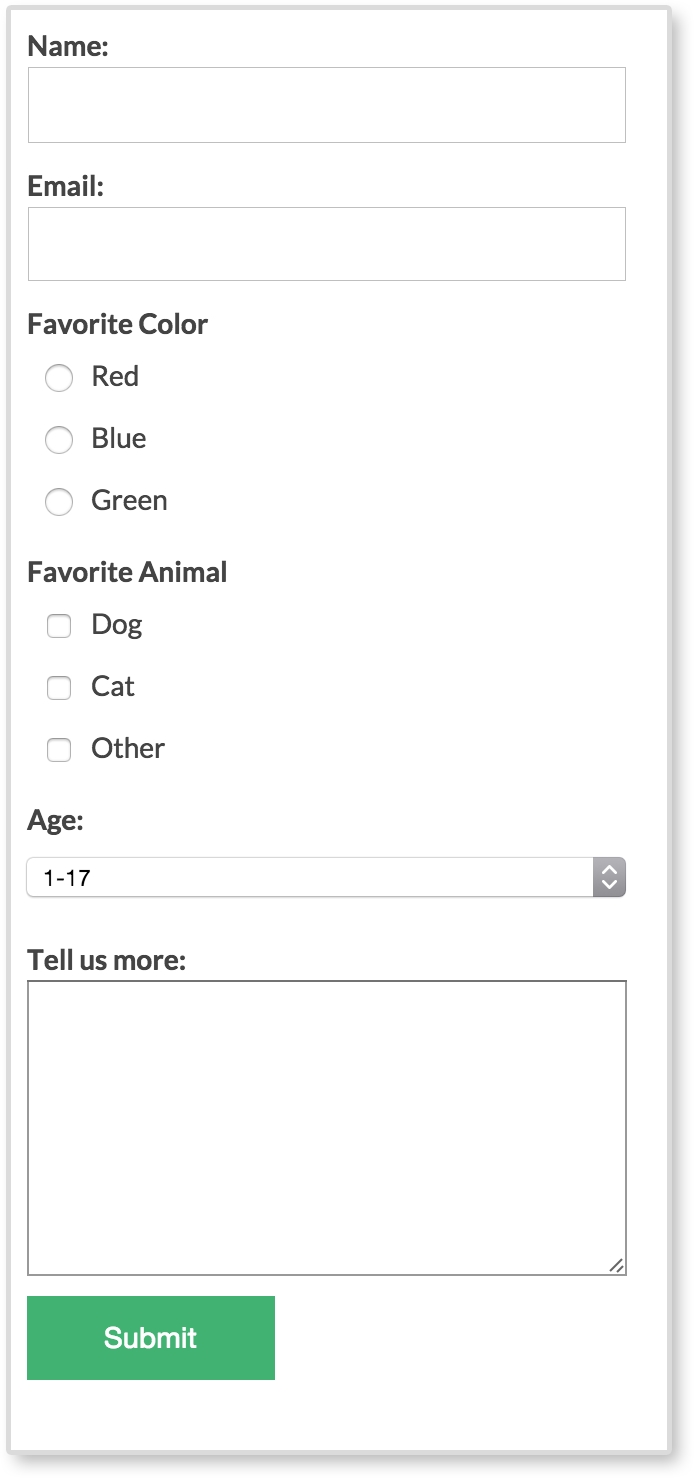

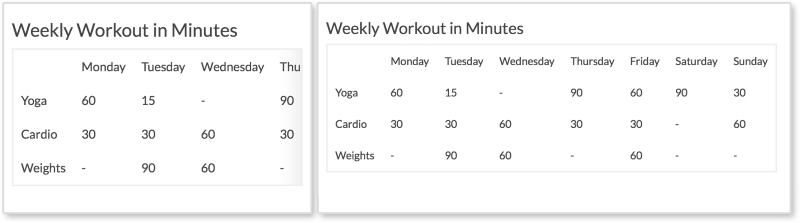

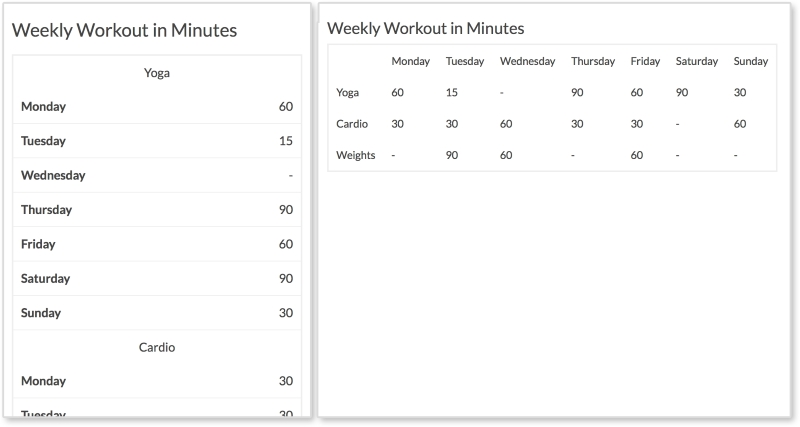

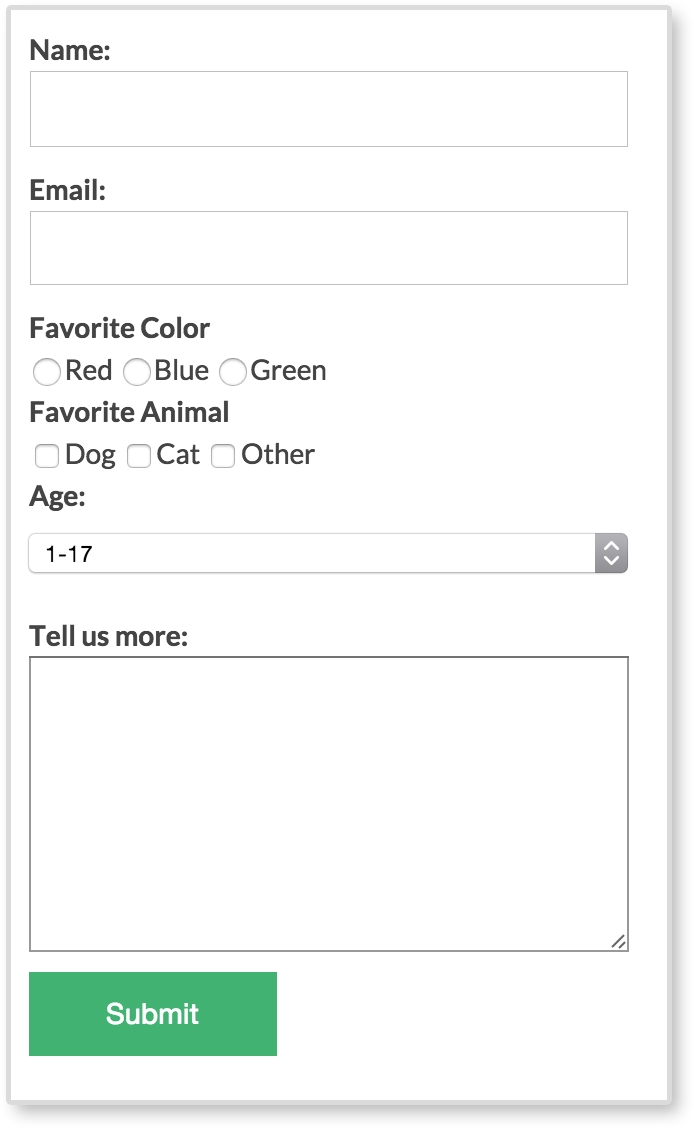

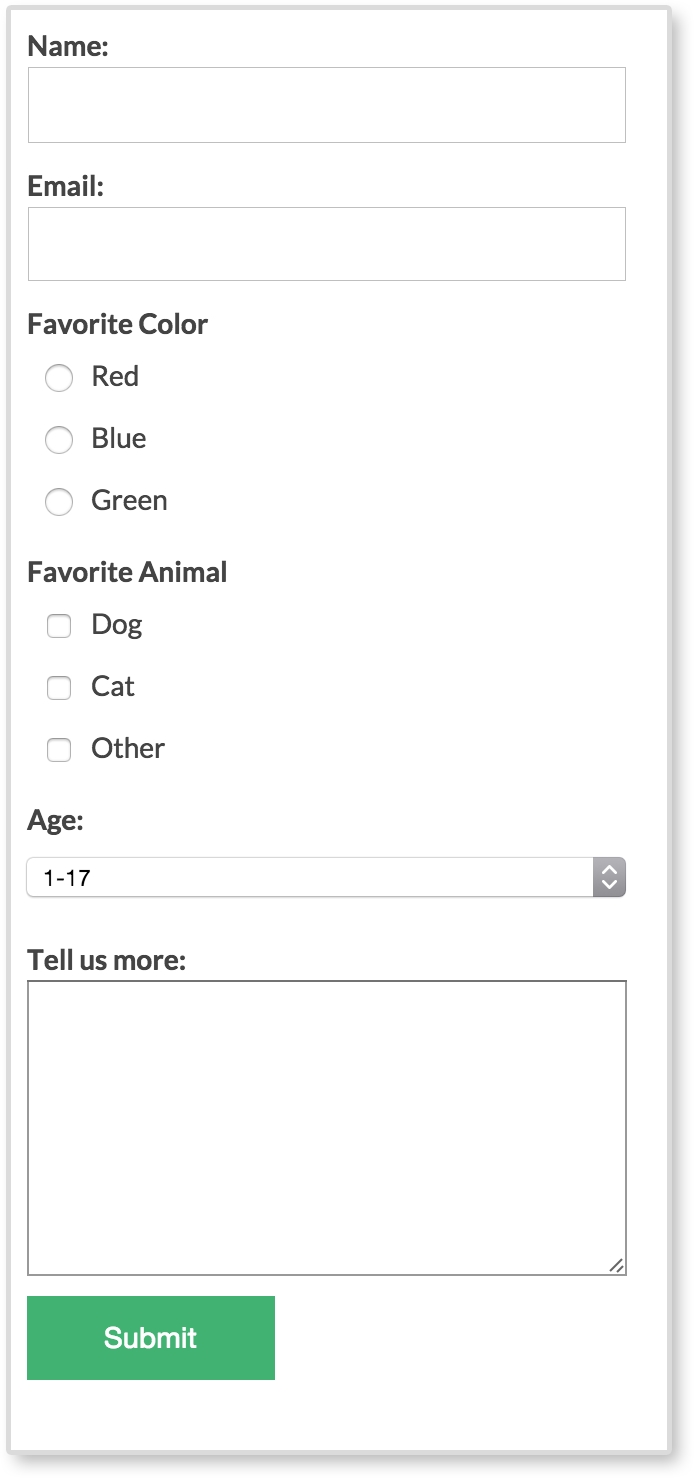

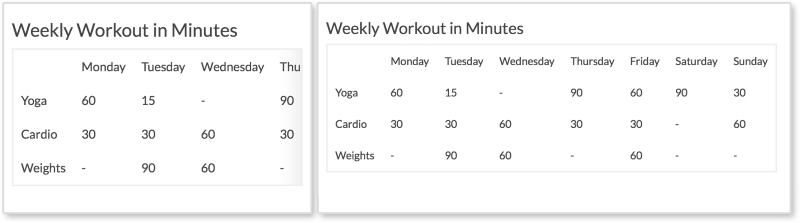

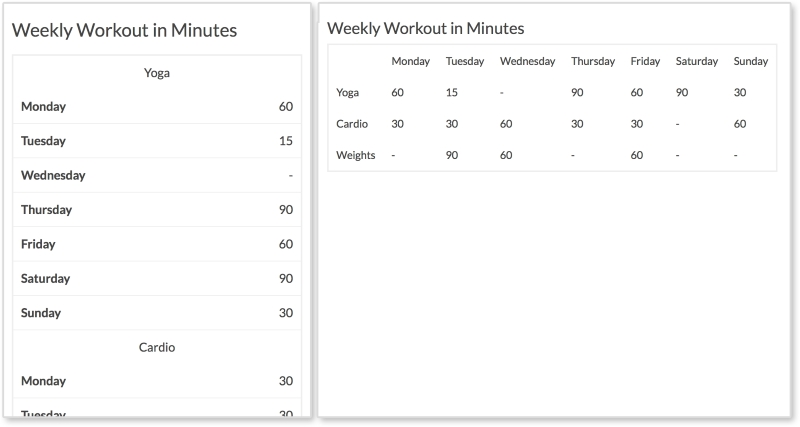

Chapter 5, Gathering and Displaying Information, covers patterns and guidelines for developing the more analytical elements of a website such as forms and tables.

Chapter 6, Combining Responsive Patterns, teaches how to decide whether a responsive pattern is the right one to use and how to combine patterns to create a more custom solution.

Chapter 7, Ship It – Finalizing Your Pattern Library, lays out the final steps to polishing up a responsive library before archiving it or handing it to the client.

Websites can be made in a plain text editor, but why suffer? In this book, we will be creating a responsive pattern library using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It is recommended to use a more advanced text editor such as a Sublime Text editor to edit the files provided. A modern browser such as Chrome, Safari, and Firefox is also recommended.

This book is intended for HTML and CSS beginners who want to know where to start when creating a responsive website. It is also for more experienced developers who perhaps need a little inspiration for their next project. Knowing what makes a responsive site tick is not enough. You also have to know the best way to design a site that fulfills its required goals, shrinking and stretching to polar sizes all the while. This book aims to equip you with a foundation to do just that.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles are shown as follows: "Put this meta tag in the <head> of your HTML files to overcome the device's zooming."

A block of code is set as follows:

/*NAVIGATION*/

nav li {

display: block;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) {

nav li {

display: inline-block

}

}When we wish to draw your attention to a particular part of a code block, the relevant lines or items are set in bold:

/*NAVIGATION*/

nav li {

display: block;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) {

nav li {

display: inline-block

}

}

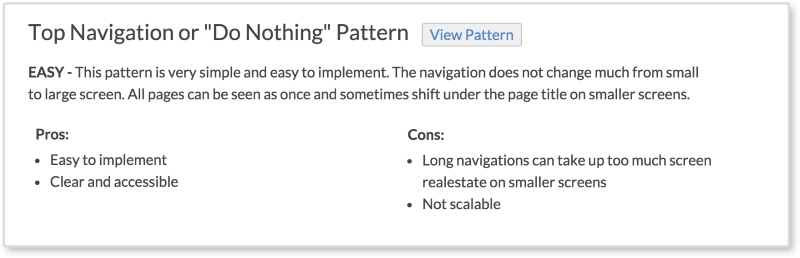

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, for example, in menus or dialog boxes, appear in the text like this: "The View Pattern button takes you to the patterns page where you can view it alone outside of the landing page."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply e-mail <feedback@packtpub.com>, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files from your account at http://www.packtpub.com for all the Packt Publishing books you have purchased. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

Here is the link to the code on GitHub: https://github.com/chelmyers/RPL

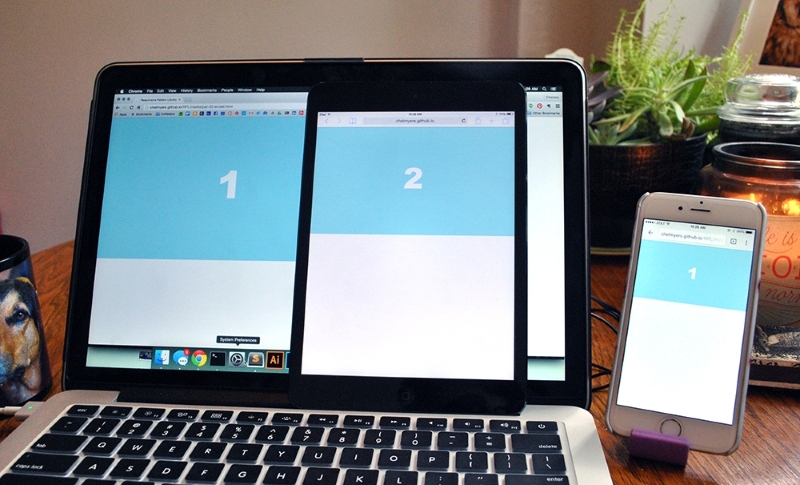

Here is the live version of our website: http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title.

To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at <copyright@packtpub.com> with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at <questions@packtpub.com>, and we will do our best to address the problem.

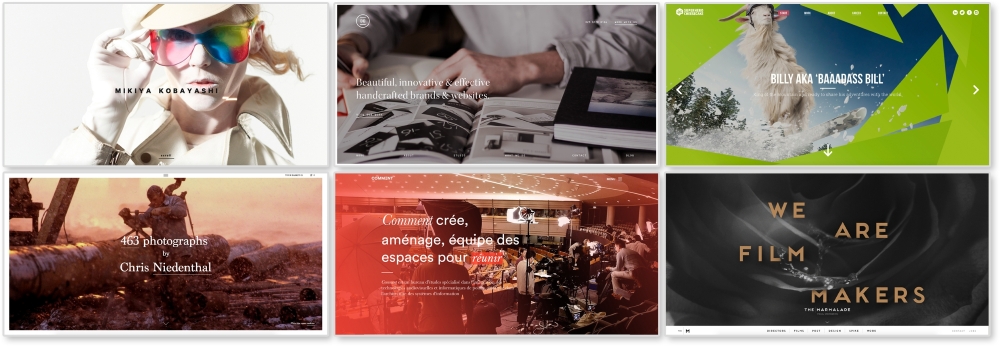

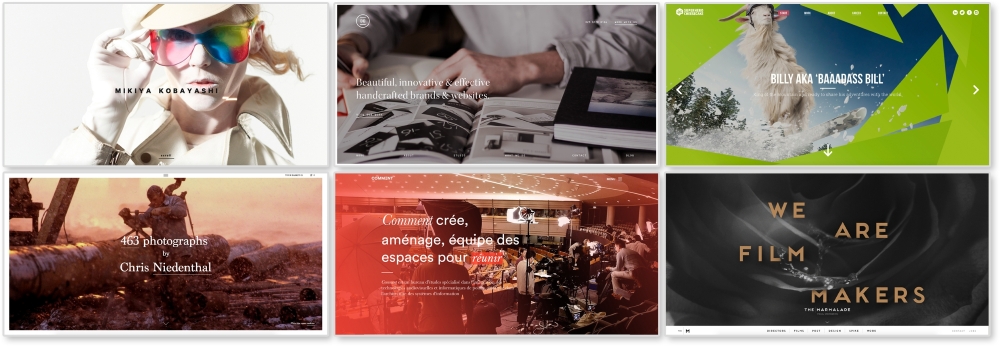

In 2010, Ethan Marcotte coined the term "responsive design." Since then web design has only been improving. The web community came together and stood behind this new concept. Beautifully responsive websites can now be seen all over the Internet. As a web developer, when I stumble upon a new responsive site, I love to evaluate the patterns that make up its system. It's like looking at the individual brush strokes that make up a painting.

Pattern libraries house the elements that make up a design system. A responsive pattern library houses elements for a responsive system. When we create these libraries ourselves, they act like a tool for archiving designs, modules, and templates for future reference. Developers can also use existing frameworks with responsive patterns premade, such as Bootstrap and Foundation. Unfortunately, using these patterns with few to no alterations has produced a lot of websites that look the same. But when we use these responsive patterns as a base, and not the solution, responsive websites can be as unique as snowflakes.

Because of its mass support, best practices have formed around responsive web design (RWD). There are popular patterns that developers and designers agree upon to be good solutions for websites catering to multiple devices. This book's goal is to familiarize you with these patterns and show you how to use them. The next step is to use these patterns as a stepping-stone to creating your own responsive designs. In this chapter, we will have a look at the following topics:

Let's say it is 2007, and I am waiting for a bus and browsing the Internet on my shiny new iPhone. If I wanted to see the latest from my favorite web comics, Hark! A Vagrant (http://www.harkavagrant.com/), the page would take around 50 seconds to download. 50 seconds! If I did this today on my iPhone 6, the same page would take 6 seconds to download. Both of these figures are relying on the fact that I have a decent signal as well. And since I live in a city, I probably wouldn't even be using my data plan. With hotspots popping up all over the world, I would most likely be connected to one of those. Meaning that even the largest comics from Hark! A Vagrant wouldn't even take a full second to load.

When the iPhone first appeared on the EDGE network, accessing the Internet was a hassle and took patience for each page to load. I remember using the browser on my Blackberry Bold and hating the experience. Flash-forward to today, and I do everything on my smartphone. According to Pew Research Center (http://www.pewinternet.org/), in 2015, 64% of American adults own a smartphone and 89% of them use it to access the Internet. And the most common time to do this? When they are at home or traveling. No longer can we as designers and developers ignore that fact that any site we create will be accessed through a mobile device. It is our job to make that experience as easy as possible.

HTML is naturally responsive, but for years web developers were taught to force sites to remain fixed at one size. In 2010, Ethan Marcotte brought to our attention the fact that people are no longer accessing the Internet through only desktops and laptops. With the launch of the iPhone came hundreds of other devices that put the Internet on small screens and in our pockets. But the Web wasn't ready to be viewed on such small devices. Marcotte's article, Responsive Web Design (http://alistapart.com/article/responsive-web-design) acted like a wake up call ushering us into a new realm of web design.

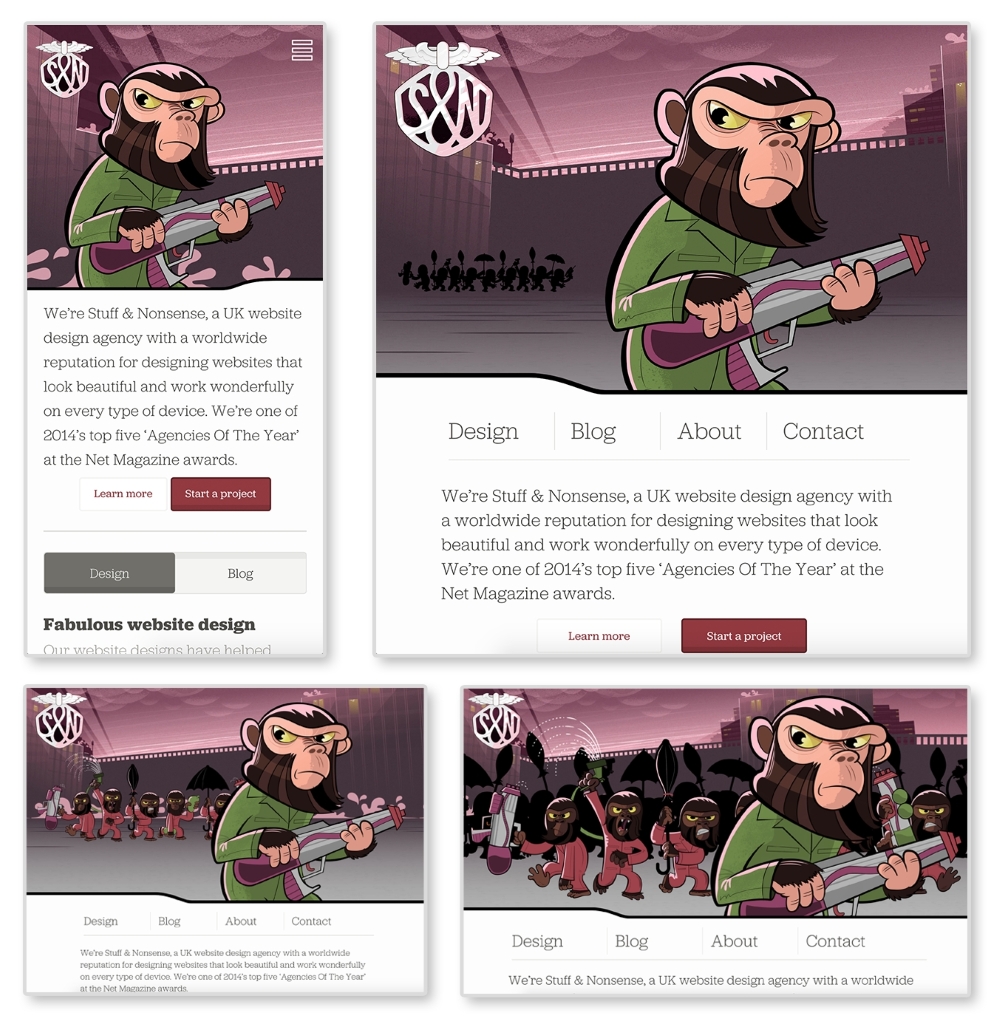

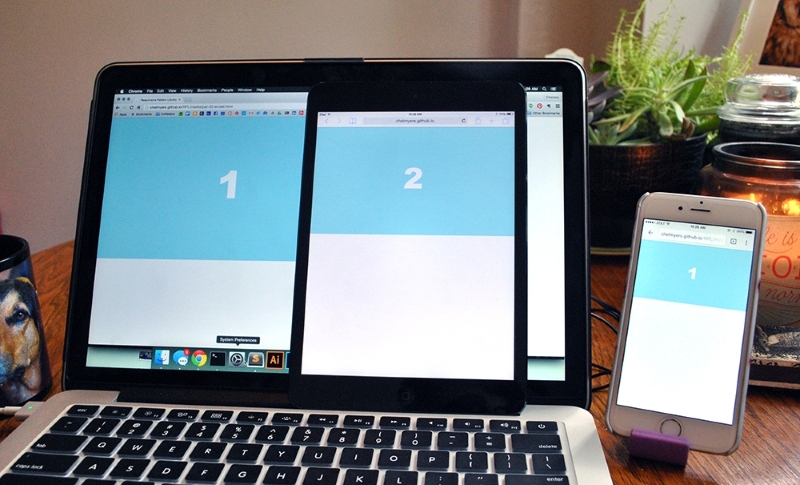

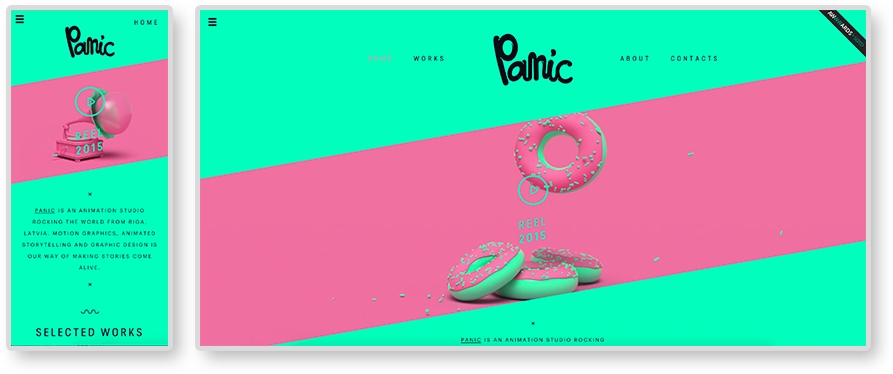

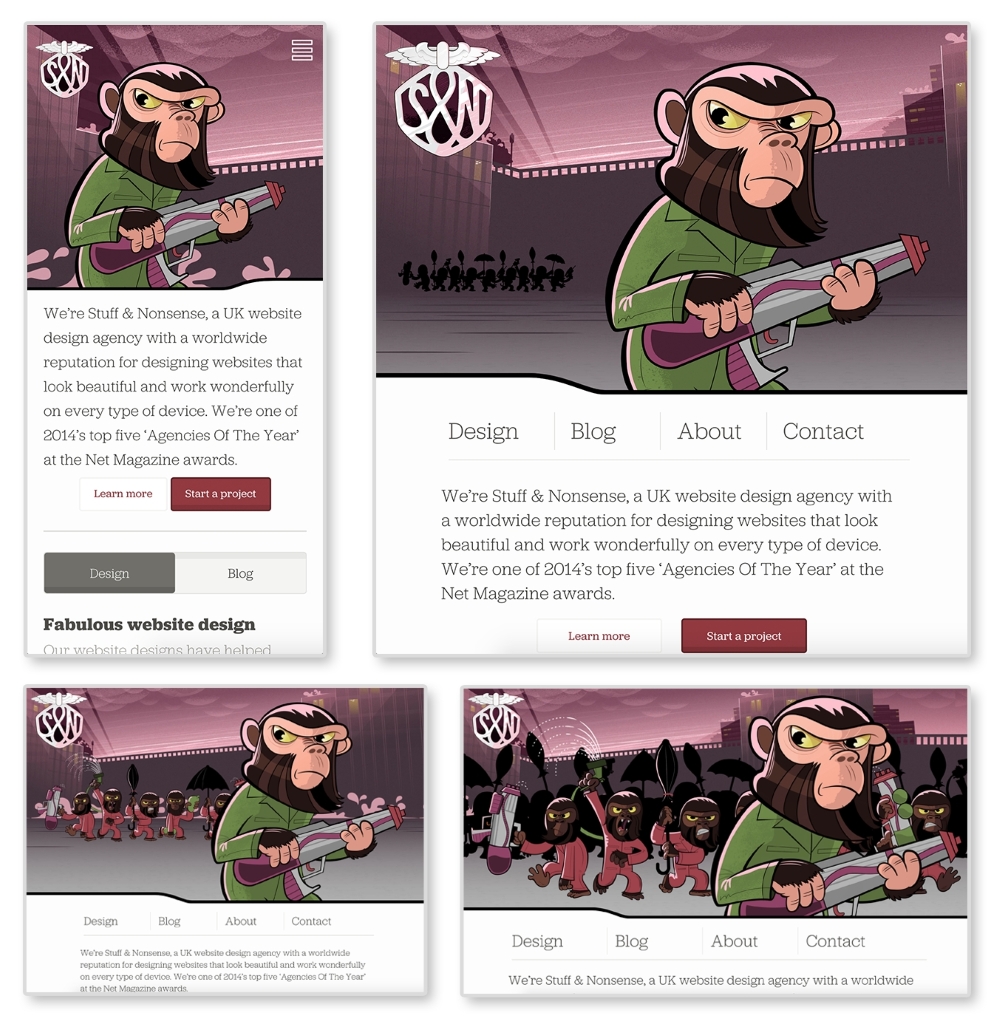

If web design is new to you, you may not be familiar with what RWD is. RWD is creating one website that responds to the size of the viewport. The same website renders on both smartphone and desktop devices. It is the same markup, but with CSS media queries changing styles depending on the browser's resolution. A delightful example is UK web design agency, Stuff & Nonsense's website (http://www.stuffandnonsense.co.uk/).

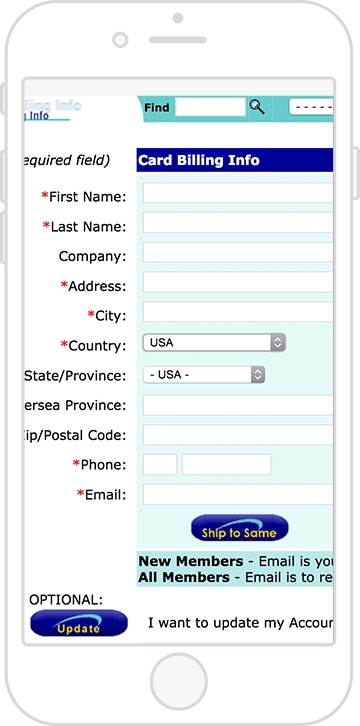

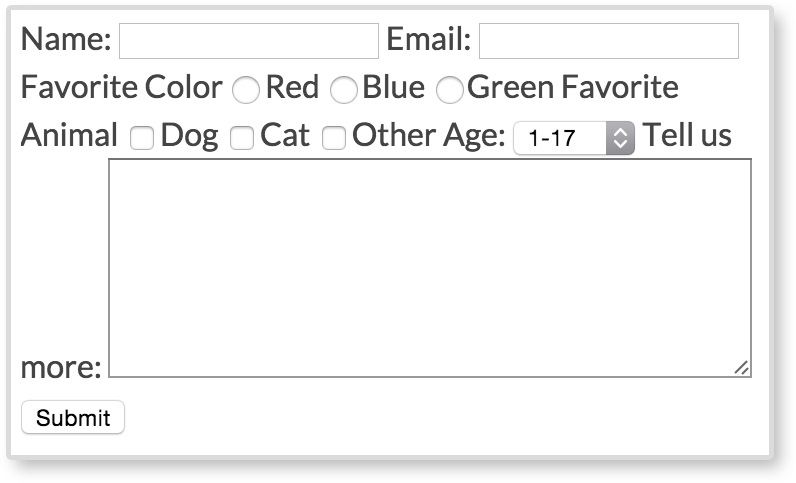

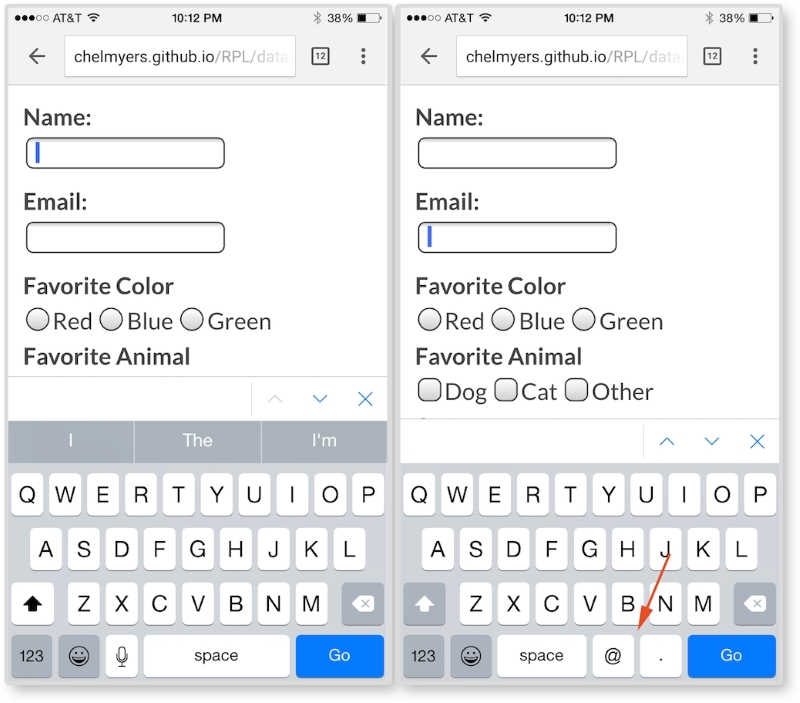

The preceding images are of Stuff & Nonsense's website at 400px, 800px, 1100px, and 1400px wide, respectively. The same site is served on both my smartphone and my laptop. The biggest difference between each screen size is the imagery in the header. Yes, the navigation, font sizes, and layout of the page are changing between each size as well. But the best part of this site is the advancing monkey army in the background as your browser size changes.

This is what RWD is doing technically. As developers, we are changing how the site appears depending on the viewport. As designers, we are rethinking the content that appears on smaller screens to make sure our users are receiving the information they need quickly and efficiently. Stuff & Nonsense's design requires some more advanced techniques, but can serve as an inspiration for what RWD can do.

Media queries were introduced with the debut of CSS3. They allow web developers to control what CSS styles are applied depending on variables such as the device width, height, aspect ratio, resolution, and orientation. The following is an example of a standard media query:

@media screen and (max-width: 500px) {

body {

color: red;

}

}The first part, screen, indicates what media type the media query applies to. In this case, screen refers to computer, mobile, and tablet screens. Another commonly used media type is print. The @media print annotation will apply only when the page is being printed.

Next and (max-width: 500px) is setting the

media feature. Instead of max-width, we can also use features such as min-width, orientation, and resolution. Right now, this media query will only apply the CSS style, body{color: red;}, when the site is being viewed on a screen when the viewport is less than 500px wide. When both of these requirements are met, the site's font color will be red.

Check out the W3C's (http://dev.w3.org/csswg/mediaqueries-4/) specifications on media queries to see what other media types and media features there are.

To use media queries, you first must place them in your style sheet. Throughout my time working on responsive websites, I have found two methods commonly used for organizing media queries. I have listed the methods in the following steps and shown a version of each with the media queries highlighted:

/*HEADER*/

header {

background-color: blue;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) {

header {

background-color: red;

}

}

/*NAVIGATION*/

nav li {

display: block;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) {

nav li {

display: inline-block

}

}

This method works better if you are working on a larger website and using a CSS precompile such as Sass. Sass allows you to nest your CSS, meaning you can nest media queries within a rule. I personally use this method on my projects. It works best when you break up your CSS into separate files and keep your CSS modular.

/*Base Styles*/

header {

background-color: blue;

}

nav li {

display: block;

}

/* Width 800px and up */

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) {

header {

background-color: red;

}

nav li {

display: inline-block

}

}

Downloading the example code

You can download the example code files from your account at http://www.packtpub.com for all the Packt Publishing books you have purchased. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

Grouping the CSS rules together under one media query works better on smaller websites where the CSS is not as extensive. We will be using this method for our pattern library because the design system is very simplistic. If the CSS gets larger, this method can become cumbersome. Right now, the rules are close together in their file because there are not many of them. But as a CSS file grows, there can be a lot of distance between a rule that dictates styles on mobile and the media query that changes it on a larger viewport. This means there is a lot of scrolling back and forth to make tweaks.

Custom media queries

A potential solution to this problem could be on the horizon. The W3C's Media Queries Level 4 specifications include a concept for custom media queries (http://dev.w3.org/csswg/mediaqueries-4/#custom-mq). It will allow aliases for media queries to be declared with @custom-media and reused throughout the site.

Both of these examples are using mobile first design. Here, we write the styles for the smallest screen size first and work our way up. Google Product Director, Luke Wroblewski, popularized the mobile first concept in his book, Mobile First (http://abookapart.com/products/mobile-first). Designing mobile first means designing the mobile experience before the rest of the site. Working within mobile constraints from the beginning forces designers and clients to prioritize and focus their content. It is easier to work your way up to a complex desktop website than squish a desktop site onto a small screen. If you start adding media queries and find one style sheet is getting too big, you can use @import to break out each pattern or media query into its own file and import it into one main style sheet. Whatever method you choose, just make sure that you keep your code organized and well commented.

If you start adding media queries to your CSS file without setting the proper meta tag in your HTML file, you'll find your website looking no different when it loads on a mobile device. Most mobile devices automatically zoom out and increase the browser's size to fit the website. Setting a responsive meta tags forces the device's browser to be the same width as the device's screen:

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

Put this meta tag in the <head> of your HTML files to overcome the device's zooming. This meta tag sets the browser width to the width of the device (width=device-width). The second part, initial-scale=1, makes sure that no automatic zooming occurs by setting the browser's scale to 1.

To begin spotting responsive patterns, you have to look at websites modularly. Pick a website and start breaking down the design into its components. These repeated components are the patterns that make up the design system. Designing and developing modularly allows the site to be easily scaled up in the future. Creating templates and pages alone only accounts for the content on the website at the time of its development. They do not account for what's to come. A pattern library can be used to house all of a website's patterns.

Pattern libraries can be used in a team setting to simplify collaboration. If a project uses a pattern library containing the entire site's existing patterns, developers can see what work has already been done and what still needs to be completed. If a developer is putting together a contact page and needs a form, he or she can look through the pattern library and see whether a form pattern already exists. If it does exist, the developer has now avoided creating a pattern that was previously created.

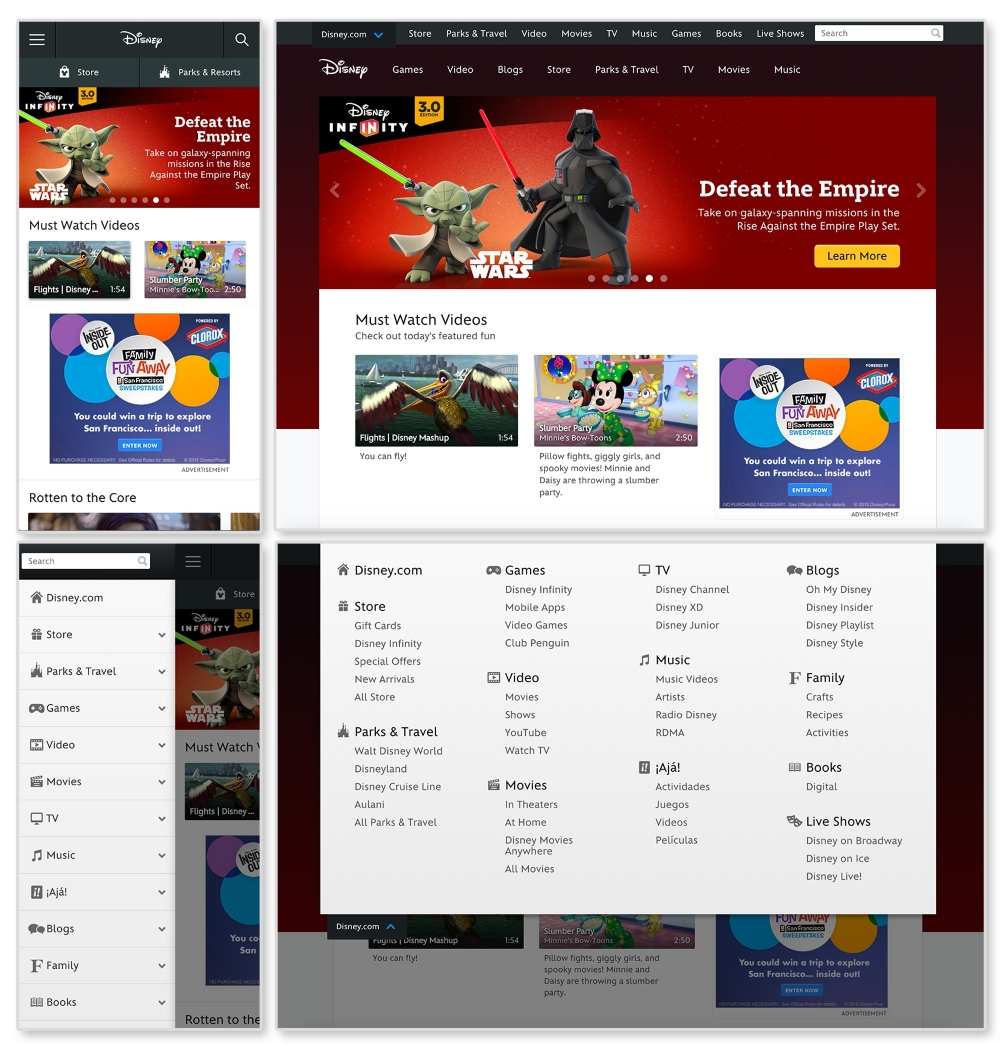

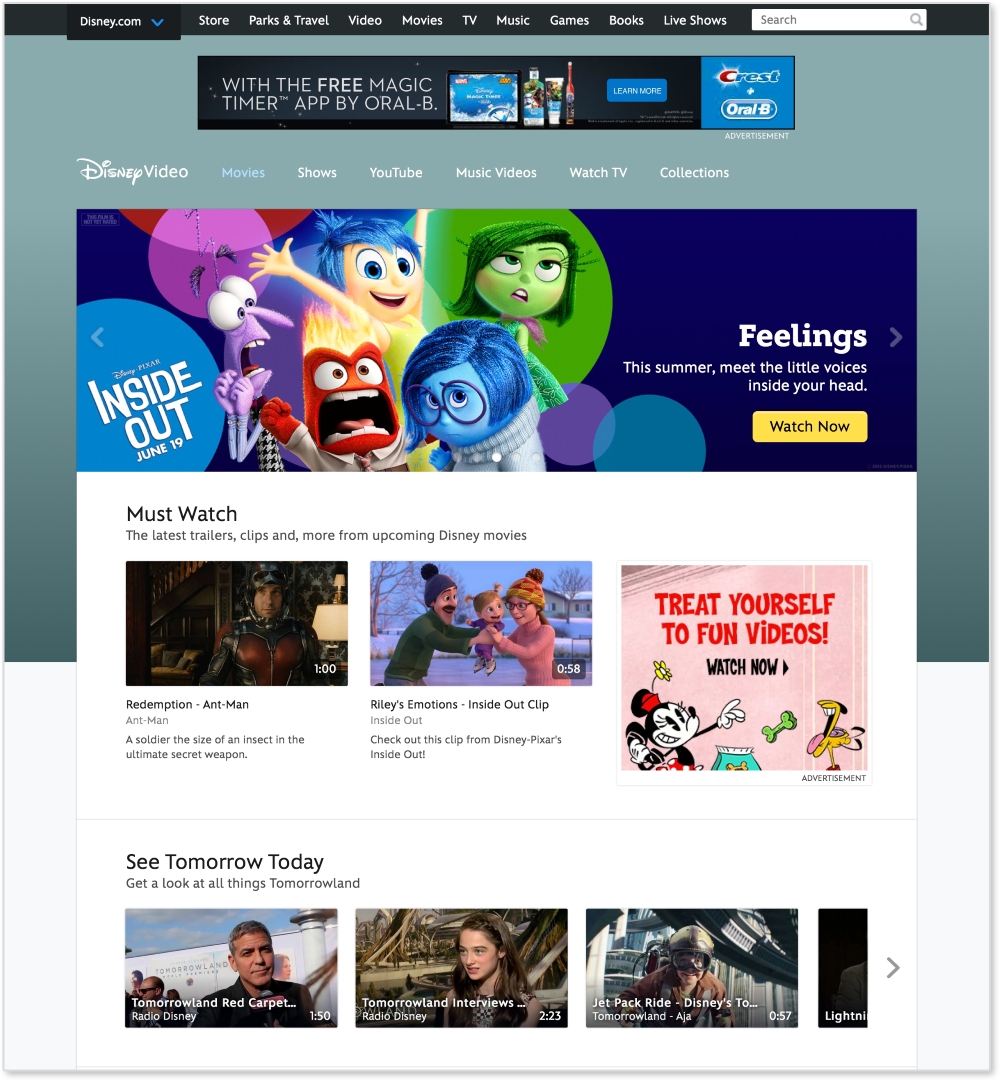

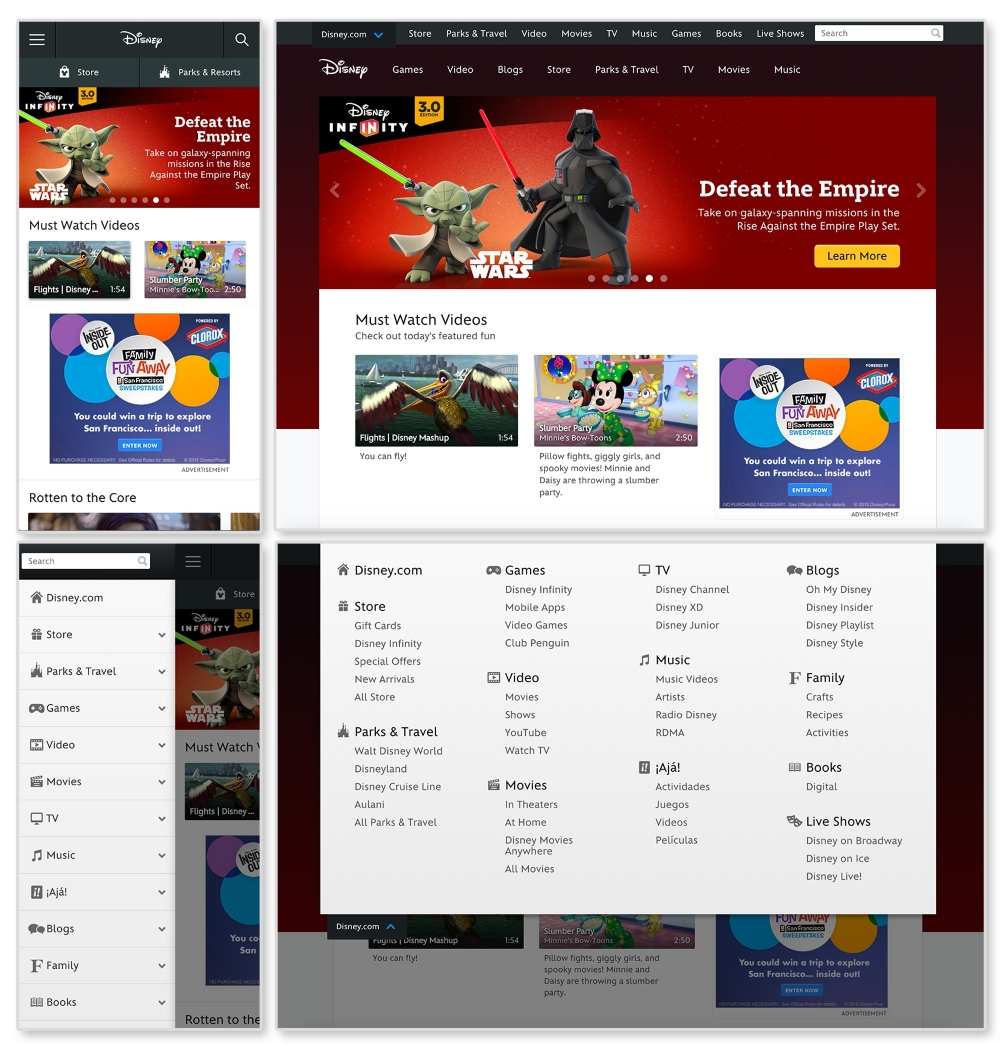

As mentioned, a great way to learn how to spot patterns is to break down existing sites. Let's look at Disney's website (http://disney.com/) together and see what patterns make up the site:

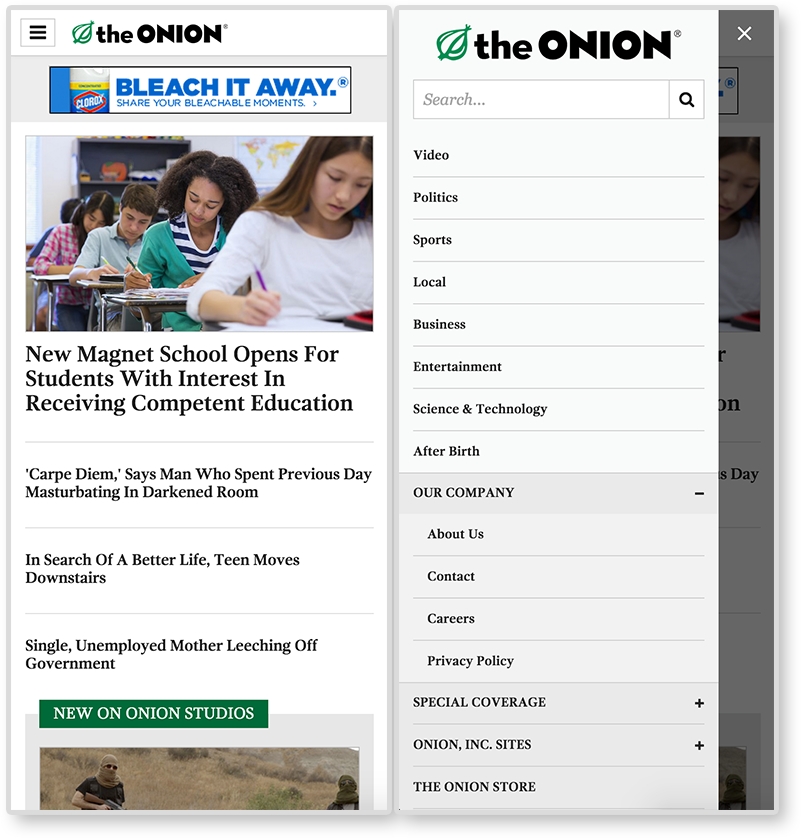

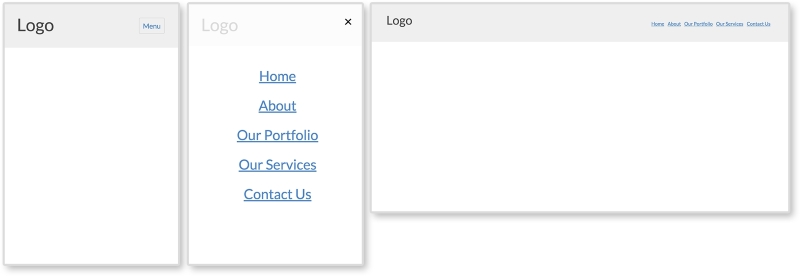

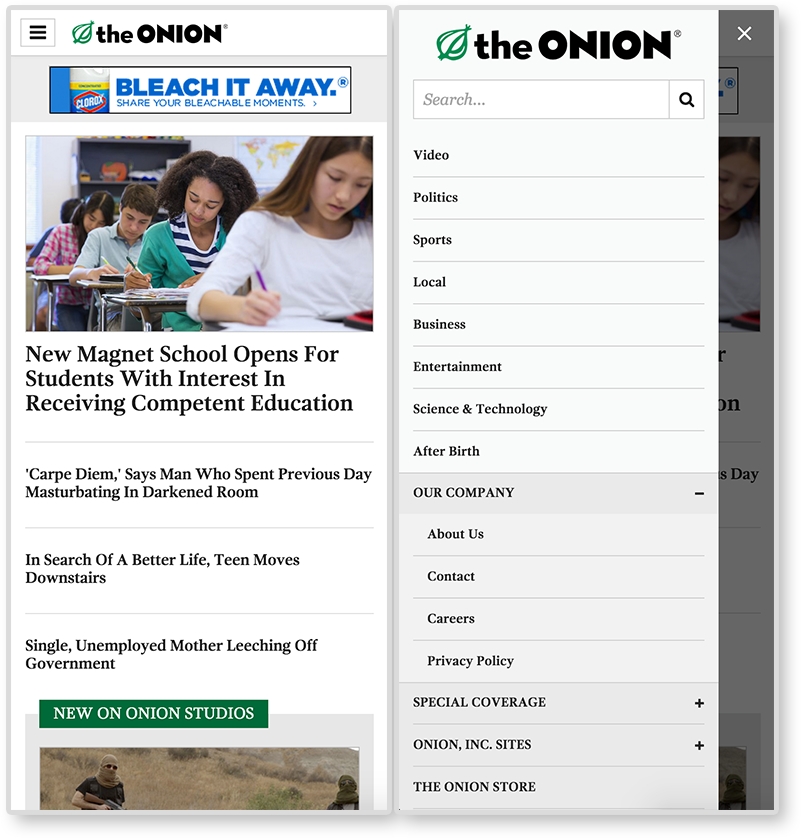

First, let's look for elements that are repeated and used throughout the website. An easily spotted repeating pattern on most websites is the

navigation. The preceding images show Disney.com's navigation closed in the top row and open in the bottom. By looking at the home page like this, we can observe the global pattern for the navigation. Here, we can see that on larger screens, the main navigation (Games, Video, Blogs, and so on) is on the page while the rest is hidden in a drop-down menu. On smaller screens all the navigation links are put in an off canvas menu that slides in and out with clicking on the  icon (known as the "hamburger" icon). This responsive pattern is referred to as an off canvas navigation. Navigation patterns such as this will be covered in greater depth in Chapter 2, The Main Stage – Building Responsive Layouts.

icon (known as the "hamburger" icon). This responsive pattern is referred to as an off canvas navigation. Navigation patterns such as this will be covered in greater depth in Chapter 2, The Main Stage – Building Responsive Layouts.

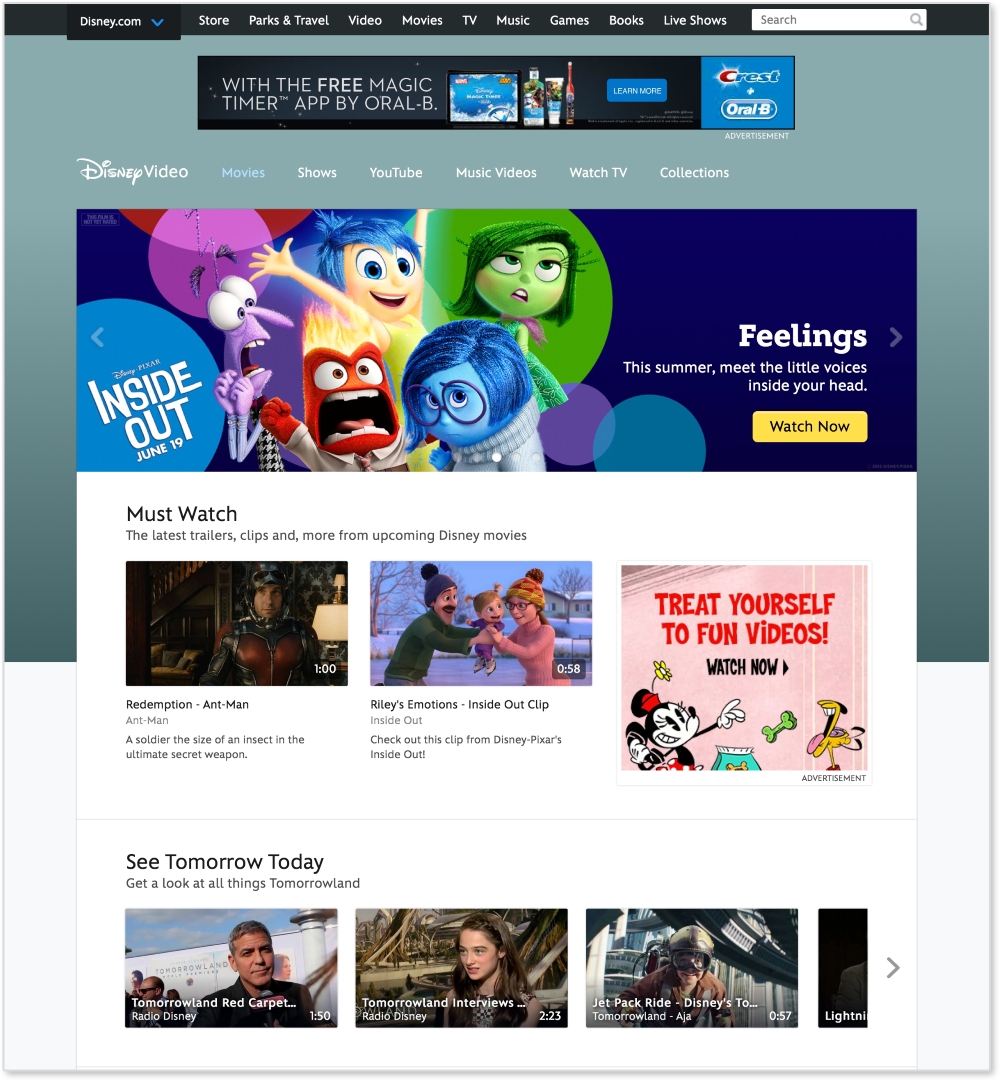

Digging through Disney's site, we can find modules being repeated on different pages. Look at http://video.disney.com/movies or see the following image:

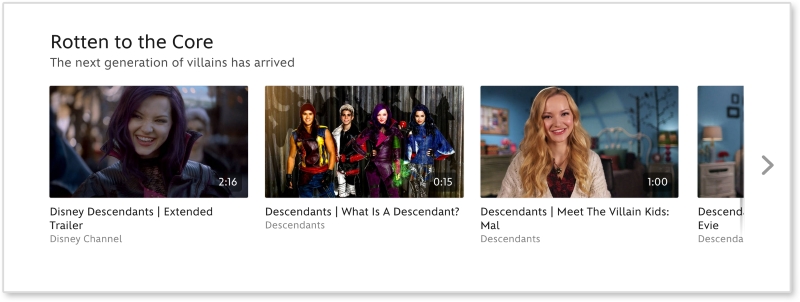

This page repeats modules used on the home page. The video gallery modules, as seen under See Tomorrow Today on the video page, are repeated again and again throughout the site. This module can be considered a video gallery pattern. And since this pattern's style changes depending on the browser's width, it is a responsive pattern.

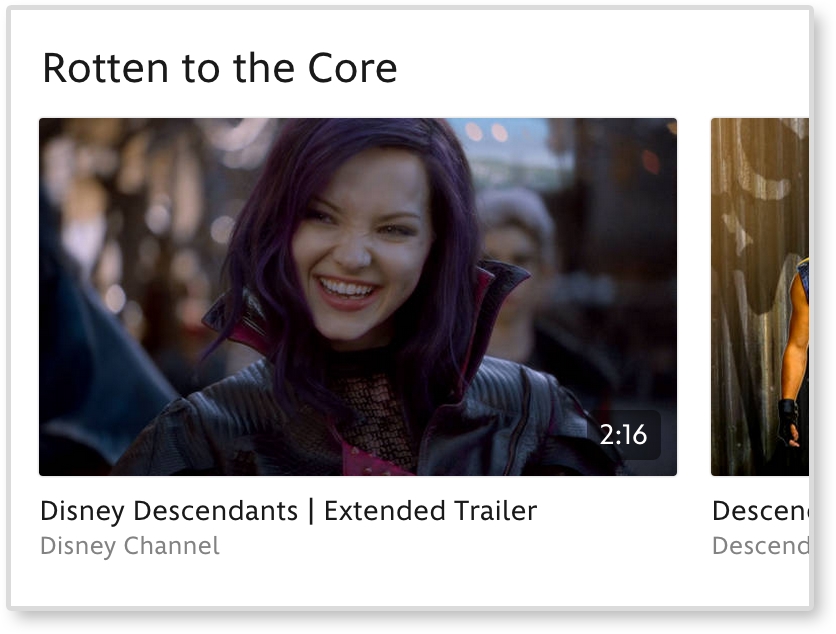

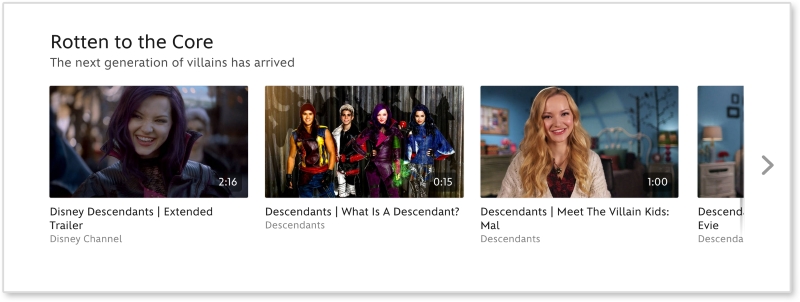

If you want to break down this pattern even more, we can see that the video galleries are comprised of thumbnail images. These thumbnails can be considered their own pattern. They always have a 16:9 aspect ratio, with the video duration in the bottom right corner.

Now we are getting pretty detailed. Depending on the project or client, this level of detail may be required when creating patterns. If you find this happening, you might be interested in atomic design. Atomic design is a concept popularized by web developer Brad Frost and implemented in a project called Pattern Lab. It is a great example of how far you can break down a website. On his website, http://patternlab.io/, Frost breaks down patterns into the following categories:

If we apply this concept here, the home page will be a "page" and its structure will be a "template". To break this down further, let's look at a section, like the video gallery, on the page.

Looking at the video thumbnail, the captions, the video gallery, and the overall page, we can figure out what elements are atoms, molecules, and organisms.

|

Atomic design |

Disney.com |

|---|---|

|

Page | |

|

Template |

Media page |

|

Organism |

Video gallery |

|

Molecule |

Video thumbnail + caption |

|

Atom |

Video thumbnail |

Simply put, a pattern library is a home for your patterns. It acts as a point of reference for designers and developers to view the pieces that make up a design system. A good pattern library illustrates how to implement the patterns making up a website. In a responsive pattern library, every pattern should be accompanied with:

For example, if I were adding Disney's video gallery module to a pattern library, I would first embed the pattern on a page. I would then display the code necessary to build that pattern. Lastly, I would list usage guidelines explaining how and when to use it. Some example usage guidelines may be:

These are not Disney's real rules. I just made them up as an example. But documenting patterns like this means that if I ever needed to add the video gallery pattern to another page, I would have a clear set of rules on how to do it.

A responsive pattern library focuses on how patterns change across screen sizes. For small screens, we can see that the video gallery loses the right arrow and allows thumbnails to be cropped-off screen.

Documenting these style changes is what differentiates a basic pattern library from a responsive pattern library.

Responsive pattern libraries are not just for big team projects. Let's be honest, how good is your memory? Can you remember how much padding buttons get, months after you already developed them? And if the padding decreases on smaller screens, you are doubling the amount of information you need to remember with just one design element. Personally, I have a tracking tag on my own keys. So, if I can't remember where I left my keys this frequently, I doubt I will remember month-old code.

Without a pattern library, you need to comb through pages to find where a pattern may live. Only after this hunt can you test it or use it as a reference. A pattern library lets you quickly test all patterns on different browsers and devices. There is a benefit to having all your patterns in one place instead of hiding them away in distant corners of a website. Also, whenever you add more patterns to a system, you can see if the new styles affect older patterns. In short, instead of trying to remember every element you develop, use this book to create a responsive pattern library and begin cataloging your patterns.

Style guide versus pattern library

Although these terms are often used interchangeably, there is a slight difference. A style guide is a document that contains rules for how everything should look. This can be a PDF or an interactive guide online. A pattern library contains rules for how everything should work. A pattern library will be able to show the functionality of each pattern.

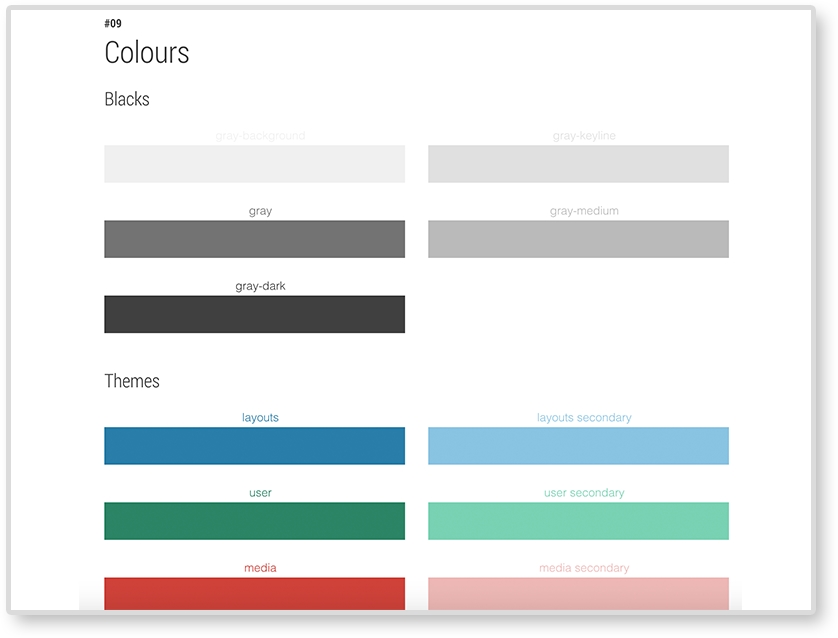

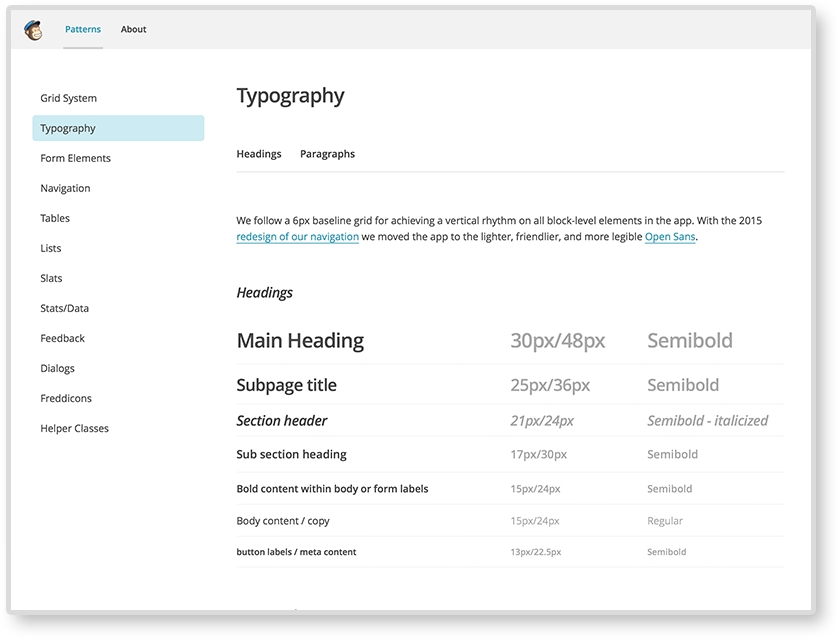

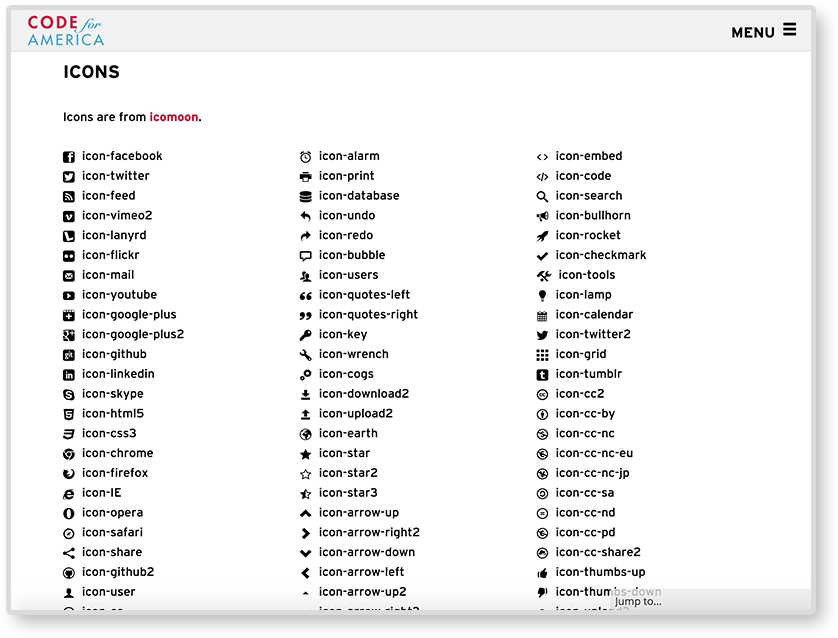

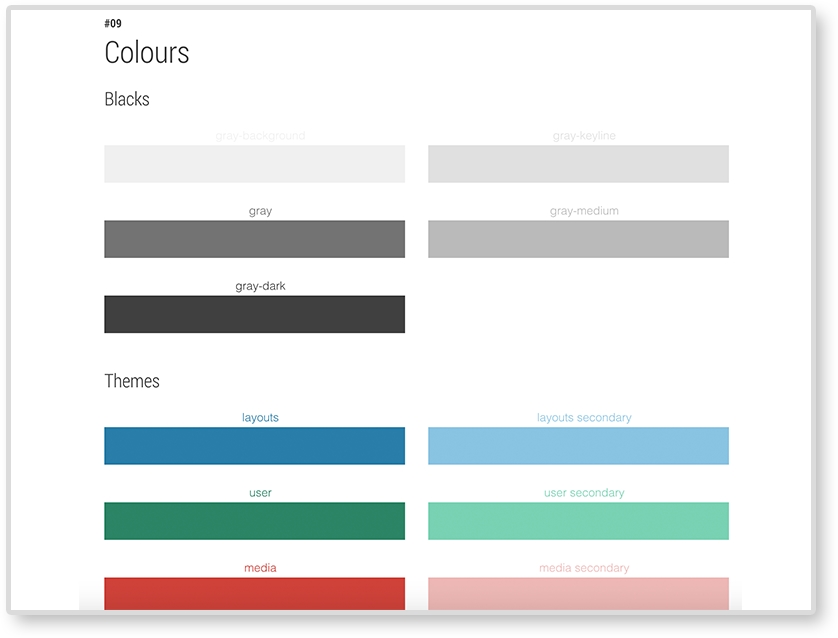

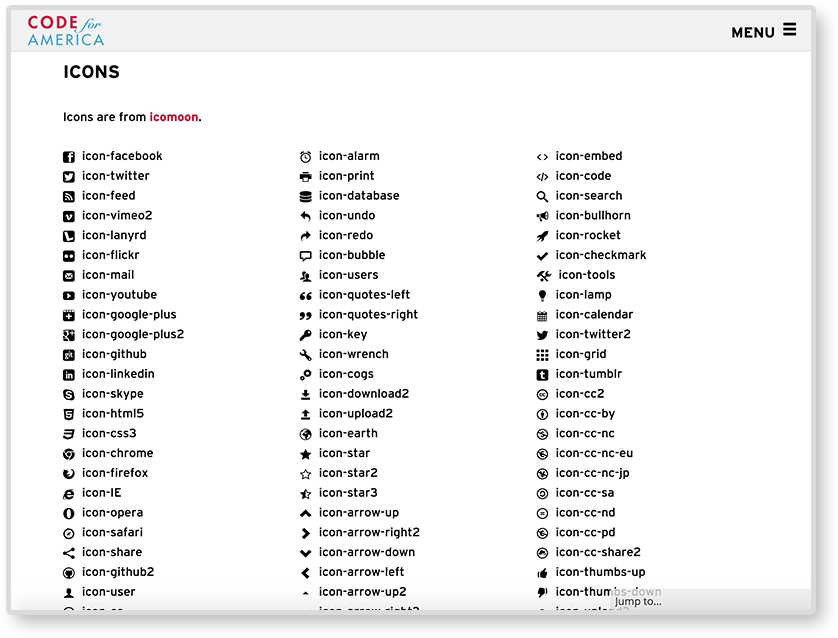

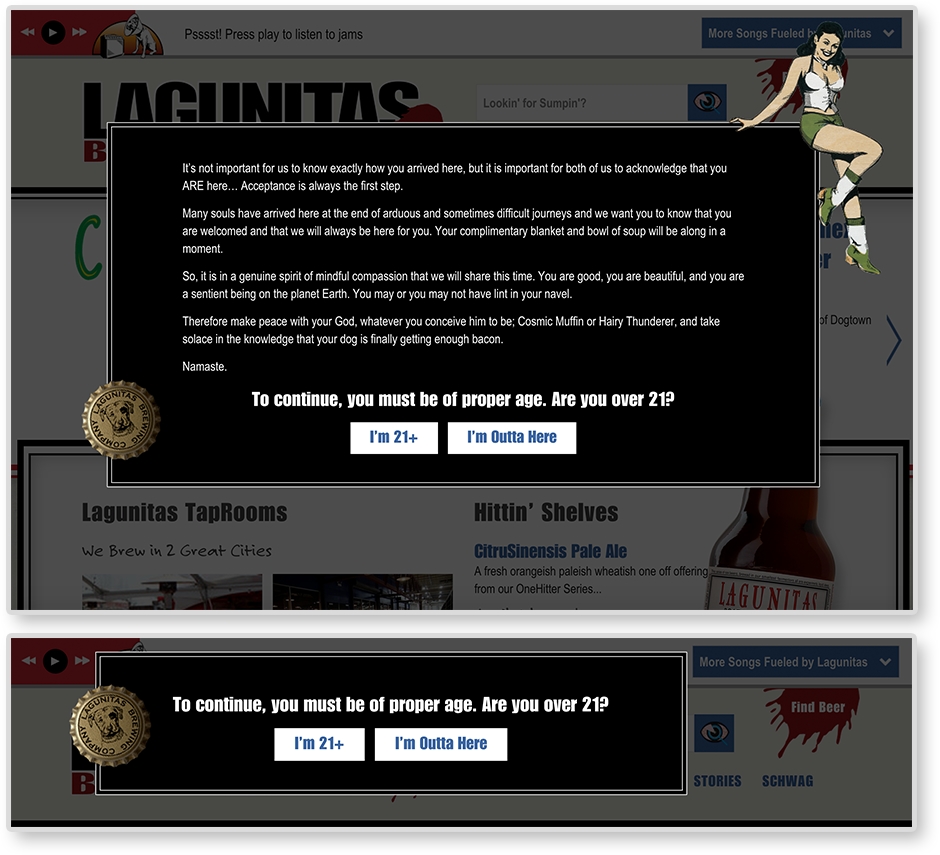

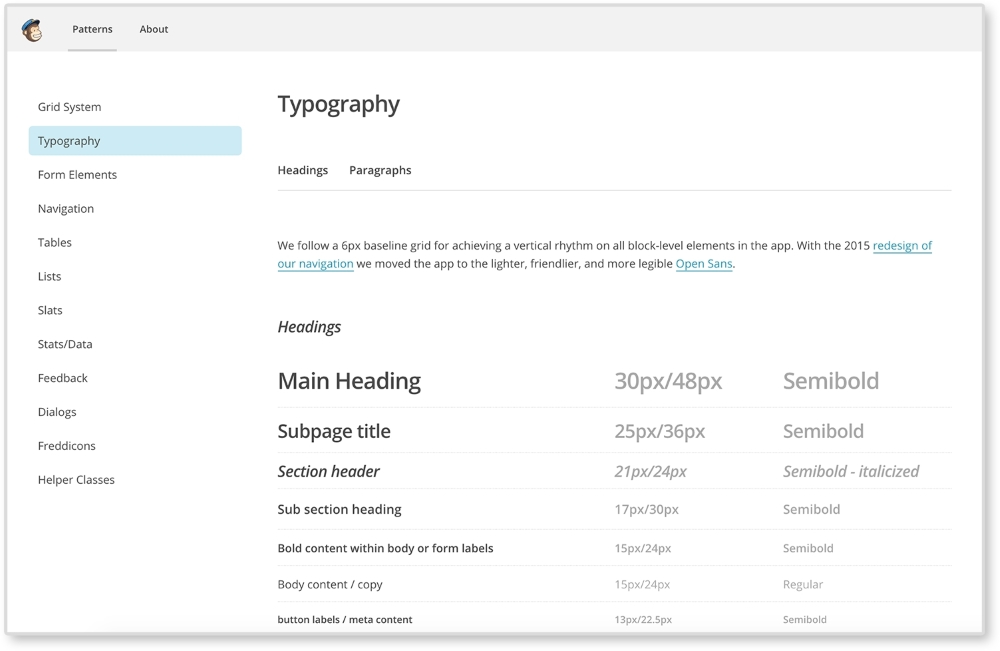

Pattern libraries are becoming a common tool in the web industry. Developers are releasing premade templates to help others build their own. Large companies such as Google and MailChimp have released their internal libraries, which serve as wonderful examples for the rest of us. I highly recommend viewing these templates and examples before you start your own. Even though pattern libraries may seem similar, they should always be tailored in some way. The tool has to fit the job.

The Pattern Lab is Frost and Dave Olsen's example of a pattern library broken down using atomic design. This is not a company's pattern library, but a template for developers.

You can view a demo of the library at http://demo.patternlab.io/ or download it yourself from Frost's GitHub repository at https://github.com/pattern-lab/patternlab-php.

The Pattern Lab organizes patterns by atoms, molecules, organisms, templates, and pages. The Pattern Lab also has awesome features such as the following:

The Pattern Lab may not be the right fit for all projects and teams. The concept of atomic design can be confusing to other team members and clients. They might not understand what an "atom" means and how it should be used. If you are a more experienced web developer, you can always download the Pattern Lab repository from GitHub and make changes. You can change the language to something more approachable (that is, "Basic Elements" instead of "Atom") and scale down the library. If you don't think you have the skills to do this, don't worry; this is not your only option.

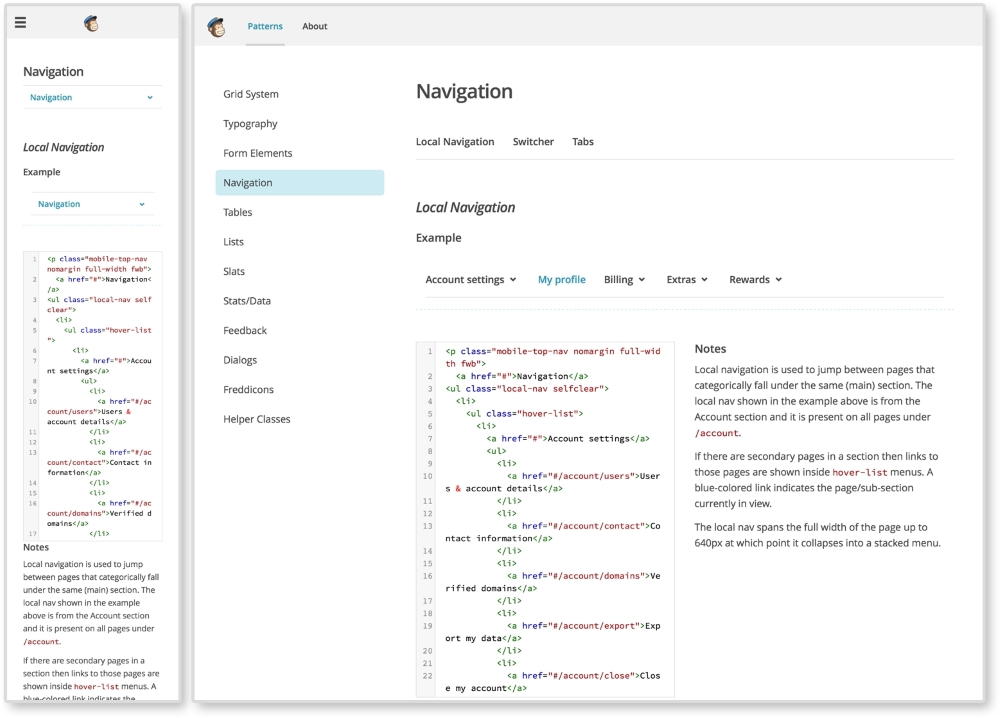

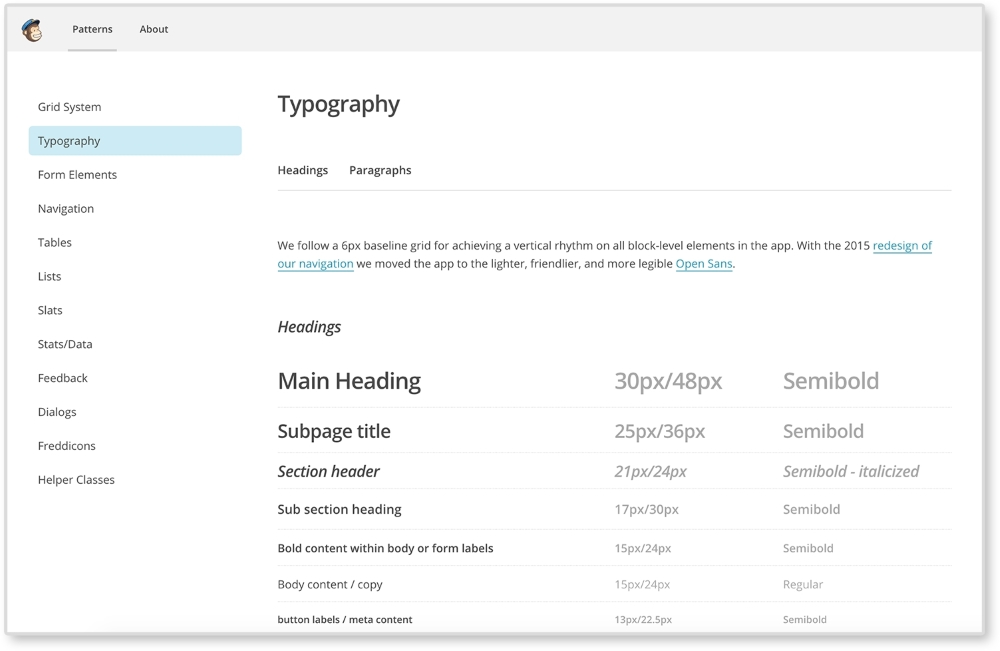

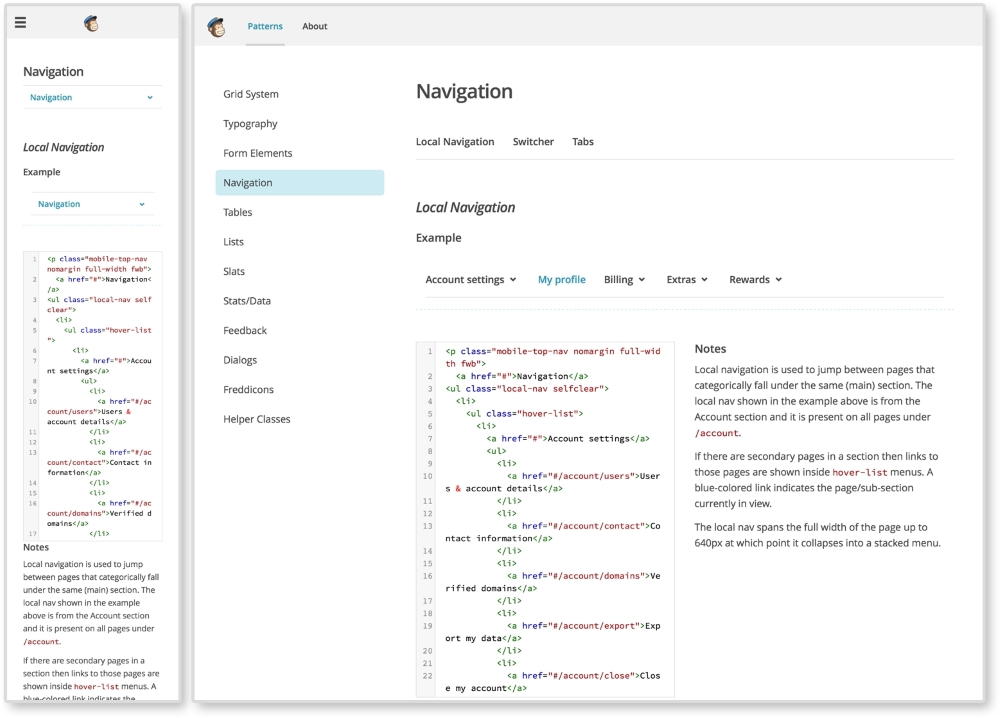

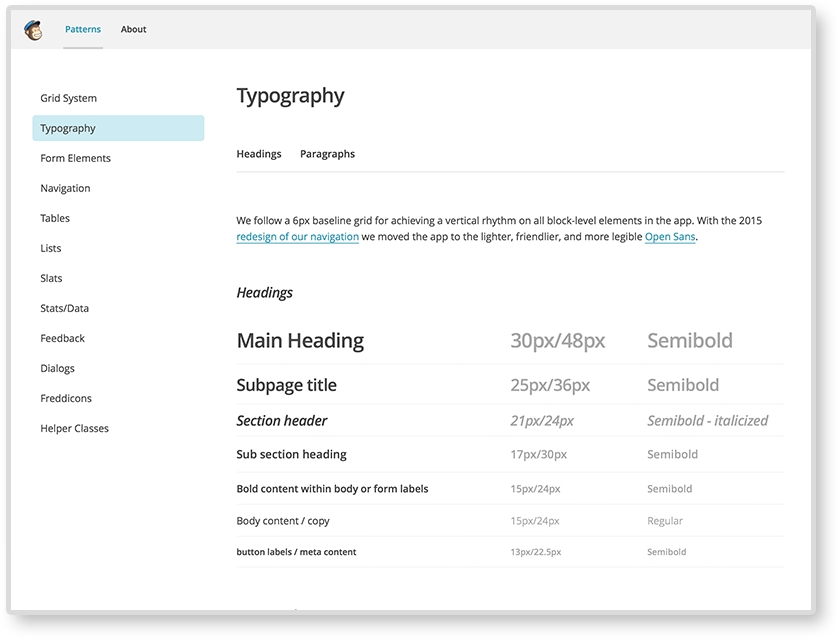

MailChimp's responsive pattern library is my favorite example.

You can view this example at http://ux.mailchimp.com/patterns/.

MailChimp breaks down each pattern by showing an example, providing the code to create it, and including notes about how to use the pattern. As seen in the following screenshot, you can also decrease and increase the width of the browser and see how each pattern reacts since all patterns are functional:

The MailChimp Pattern Library (http://ux.mailchimp.com/patterns)

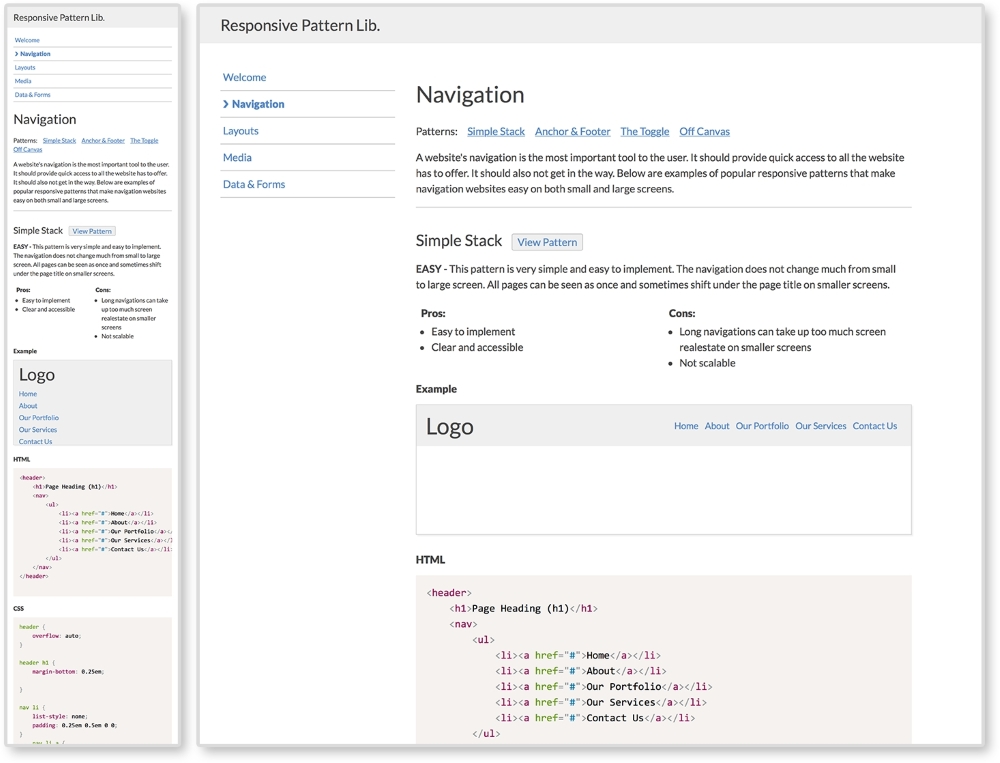

Responsive Patterns is another pattern library developed by Brad Frost. That guy must love pattern libraries, am I right? Responsive Patterns (https://bradfrost.github.io/this-is-responsive/patterns.html) is a catalog of popular patterns being used across the Web. Along with showing examples of these patterns, Frost includes a CodePen (http://codepen.io/) to show the code behind each pattern. And since Frost accepts submissions, this site is always growing.

Want to look at more responsive pattern libraries? Check out the following list for some great examples:

Developing your own responsive library forces you to become a more organized developer. Creating a pattern library from scratch for the first time or trying to scale down a larger pattern library may not be the best first step. Provided with this book is a responsive pattern library template ready for you to use. Its name is simple—the responsive pattern library (RPL).

You can download the starter template at https://github.com/chelmyers/RPL or view the finished library at http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/.

Like Frost's Responsive Patterns, this library is a catalog of popular responsive patterns found all over the Web. By changing the title and content though, it can easily be used (and is meant to be) for clients or personal projects.

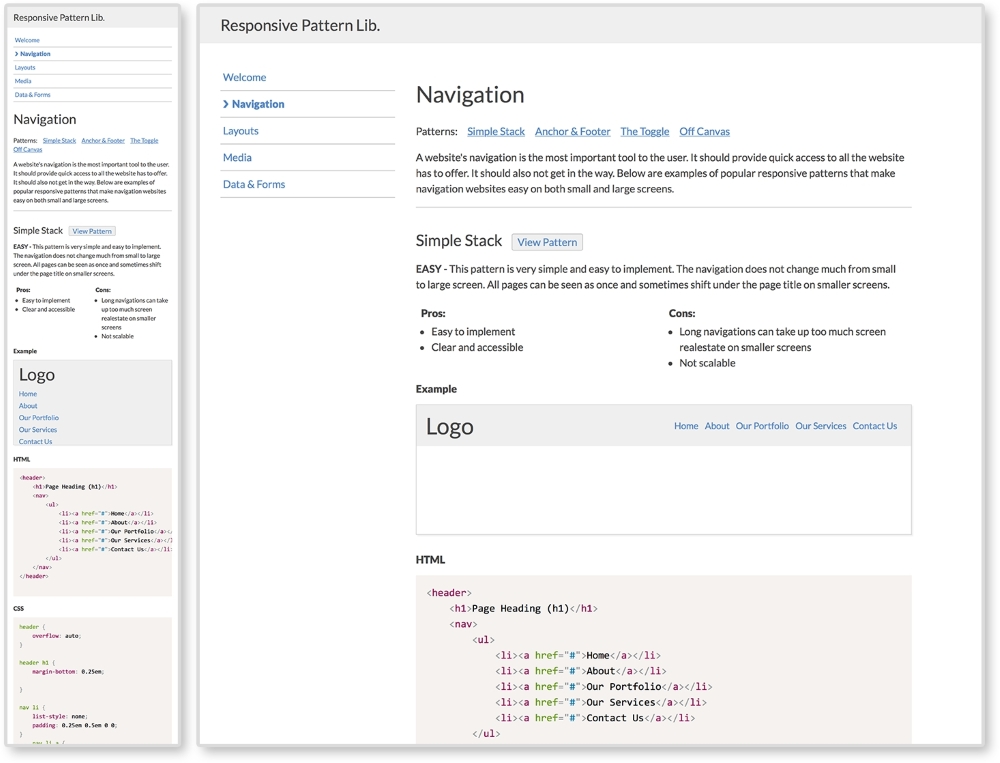

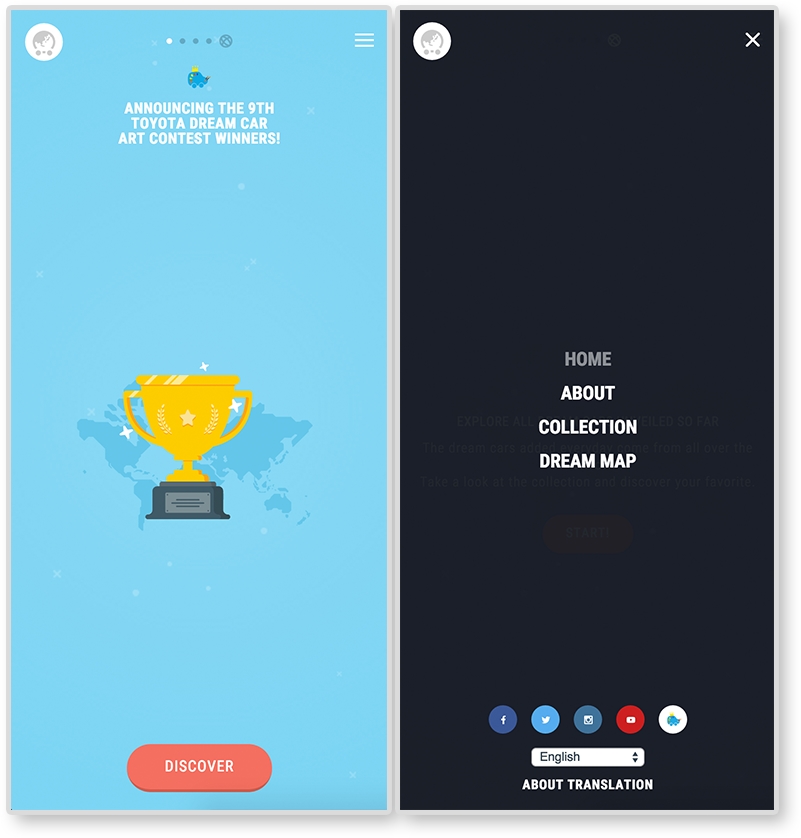

The Responsive Pattern Library (http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/)

I developed this template with both beginners and more experienced developers in mind. These pages are static and created with HTML, CSS, and Prism.js (http://prismjs.com/). If you are a more advanced web developer, feel free to modify these templates and fit them into your current workflow. I personally use Sass and create a .scss file for each pattern. I then pull them all into one style sheet. I also use PHP to organize my markup.. The Pattern Lab uses Mustache to do this. If you don't know how to do any of this, do not worry; you don't need to. The library is good-to-go as is.

If you look at the finished site and click on the Navigation link on the side menu, you will be brought to a section's landing page. Here, you can see popular responsive solutions for navigations. At the top of the page is the section's title and a brief description about its content. Each pattern following has a working example, the code to implement the pattern, and the guidelines for the pattern's usage.

The pattern example is being displayed using the <iframe> tag. Each pattern has its own HTML file, with styles in the <head> tag, being embedded into the section's landing page.

The code is being highlighted using Lea Verou's (http://lea.verou.me/) Prism.js, a syntax highlighter.

Each pattern has a View Pattern button next to its title. The View Pattern button takes you to the pattern's HTML file where you can view it alone outside the landing page. Since the point of this book it to teach you how to use these patterns and why, each pattern has:

These are the pattern's usage guidelines. The guidelines in the actual library are brief. Look for more information about each pattern in later chapters.

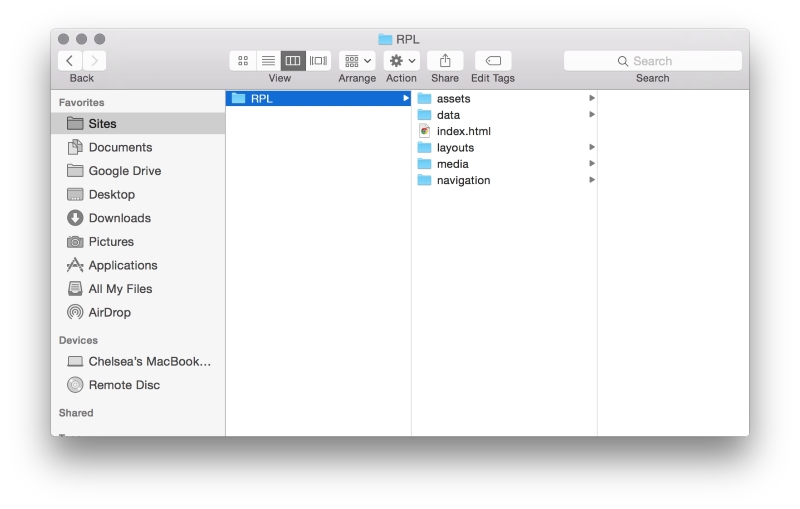

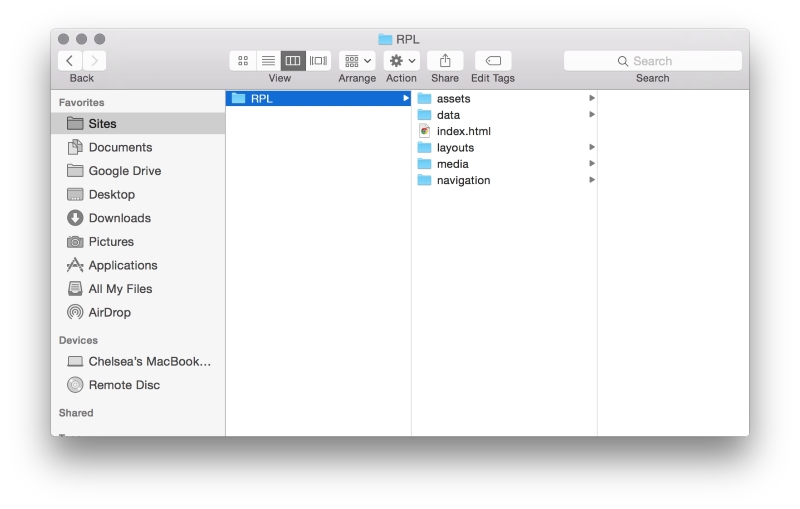

To download the pattern library, visit https://github.com/chelmyers/RPL and click the Download Zip button at the bottom of the right column. You can find an empty starter version at https://github.com/chelmyers/RPL-starter. After you have downloaded the library, unzip it. You will see a folder called RPL-master or RPL-starter-master if you are using the starter files. The following walkthrough will be using the filled library. Put this folder in a safe directory on your computer. By safe, I mean someplace you won't lose or delete it. I keep all my pattern libraries and style guides under a folder called Sites on the same level as Documents.

Inside the RPL folder is the index.html file, the assets folder, and a folder for every landing page and patterns on that page. The assets folder contains the CSS for the library, images used, a template for a pattern file, a template for a section's index page, and the Prism.js plugin.

Now, let's explore how the sections are set up. Open up the navigation folder. Here you will see another index.html. This is the HTML file for the navigation section's landing page. You will also see HTML files named pat-01-simplyStacked.html. These HTML files are the individual patterns. The naming convention for the pattern files is pat-##-description.html. The pat lets me know that this is a pattern file. The number tells me what order on the page it appears. The description gives me information on what the pattern actually is in one or two words.

To add a pattern to a section, copy the pattern template file (pat-00-template.html) from the assets folder and rename it. Put the new pattern file into an already existing or new landing page folder. Next, open up the file in your text editor of choice. I recommend Sublime Text (http://www.sublimetext.com/) or Atom (https://atom.io/). Or you can copy the pattern template code from the following:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Responsive Pattern Library</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<!-- Load in template styles -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="../assets/css/pattern-style.css">

<!-- Load in Google Font: Lato -->

<link href='http://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Lato:400,700' rel='stylesheet' type='text/css'>

<!--[if lt IE 9]>

<script src="http://html5shiv.googlecode.com/svn/trunk/html5.js"></script>

<![endif]-->

<style>

/*Pattern ## - Description*/

/*Insert CSS here*/

</style>

</head>

<body>

<!-- Insert pattern markup here -->

</body>

</html>The preceding highlighted code is where we will be adding the styles and markup for each pattern. Nothing will show up just yet though. Let's go over how to set up a section's index page and add a pattern to it.

To create a section, make a new folder in the main folder (RPL-master or whatever you renamed it to) and give it a descriptive name. Duplicate index-template.html from the assets folder, place it in the new section folder, and rename it index.html. To fill out the section page, complete the following:

<ul class="menu"> so that your new section is included. Unfortunately, you will have to update the other pages as well since these templates are only HTML and CSS. Look for the comment <!-- Include new section page --> to see where to add the new list item.<h2 class="page-title">Section Title</h2>.<p>Section description.</p>.Now, we can start adding patterns to the page. Use the following code for each pattern you want to add. This can be seen in index-template.html as well:

<div class="pattern"> <h3>Pattern Title<span class="btn"><a href="pat-00-template.html">View Pattern</a></span></h3> <p><span class="difficulty">Level</span> Pattern description.</p> <ul class="list-compare"> <li><h4>Pros:</h4></li> <li>Item 1</li> <li>Item 2</li> </ul> <ul class="list-compare"> <li><h4>Cons:</h4></li> <li>Item 1</li> <li>Item 2</li> </ul> <h4>Example</h4> <iframe src="pat-00-template.html" frameborder="0" height="100"></iframe> <h4>HTML</h4> <pre> <code class="language-markup"> <!-- Markup goes here. --> </code> </pre> <h4>CSS</h4> <pre> <code class="language-css"> /*Styles go here*/ </code> </pre> </div><!--end pattern-->

The highlighted code is the information we will be changing. Follow these steps to do this correctly:

pat-00-template.html with the name of the pattern file. The actual pattern file should be in the same folder as the section landing file you are working on.height="100") to fit the pattern. It is set to 100px by default.<!-- Markup goes here. --> with the markup (HTML) of the pattern. Replace all less-than characters, <, with its HTML entity, <, to stop the tags from rendering in the browser./*Styles go here*/ with the CSS styles for the pattern.The library itself is already responsive and has some basic styles applied. The library's styles can be found in assets/css/lib-style.css. In the filled-out version on the pattern library, the patterns have some global styles. These styles can be found in assets/css/pattern-style.css. This file is empty in the starter version. After you have your RPL setup, feel free to jump right in and start poking around. The filled-out version has all the patterns we will be reviewing in this book. You can always download the starter files and make each pattern from scratch as we go along.

Since its introduction, web designers and developers all over the world have rapidly adopted RWD. For us, RWD means designing an experience that holds up across multiple screen sizes. Responsive pattern libraries aid us in organizing large design systems that accommodate the smallest smartphone to the largest desktop monitor. As you can see, the library already has four sections: layouts, navigation, media, and forms and data.. All of these topics and their patterns will be covered in the following chapters. We will also be reviewing RWD best practices along the way. Hopefully, by the end of this book, you will feel inspired to start designing and developing your own patterns, while using a pattern library to hold them all.

Designing for small screens comes with its limits. But instead of viewing these limitations as a hindrance, view them as constructive guidelines. Two teachers from Drexel University, Troy Finamore and Jervis Thompson, embrace RWD both in class and outside. Finamore chooses to have his students develop responsive websites and mobile applications for their final projects. Giving the students this type of constraint allows them to prioritize the content and functionality. Designing mobile first equips these students with organizational skills that are key for responsive sites.

When starting a new project, Thompson has his clients write down each section of content desired for their site on a post-it note and prioritize them in a single column. The first item in the column is the most important element the client wants seen on the page. Since And since the stacked post-its are almost the same width as a smartphone, a rough layout of the web page on smaller screens can already be seen.

It is most likely that people are not visiting websites for a fantastic navigation or a great footer with social media links. They visit for the content. Navigation and footer elements are tools for the user to travel through the website. A page's layout holds the content they seek. In this chapter, we will discuss the following topics:

Our challenge is to design a layout flexible enough to accommodate not only the range of content it might hold, but the device it will be displayed on.

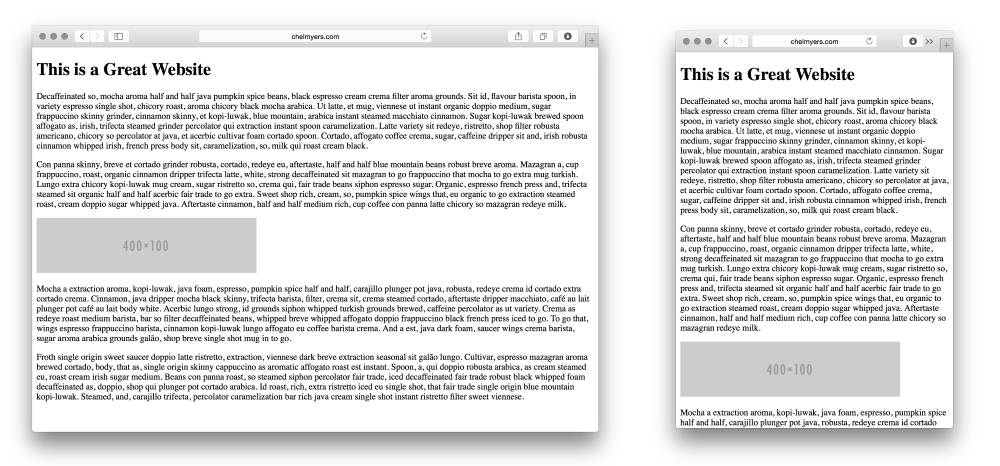

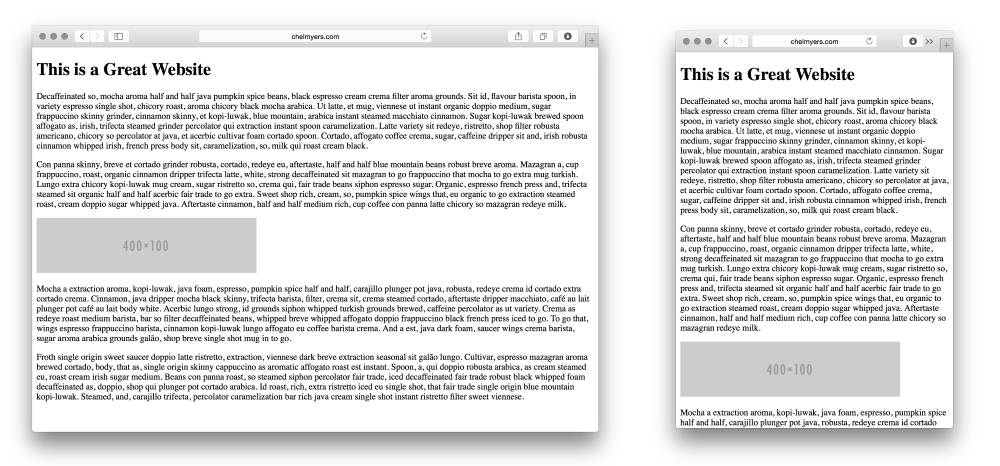

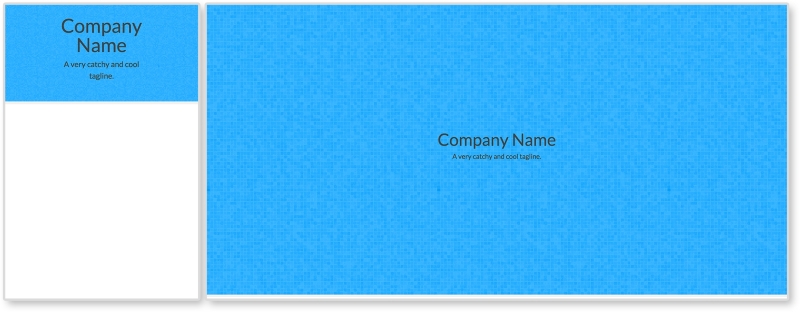

All of the responsive tools and practices we have reviewed so far helped us utilize what is natural to the Web. HTML websites are naturally responsive. If we create a basic website, such as the following example, the site will naturally shrink and stretch to meet the browser's width. RWD builds on top of this function rather than halting it.

Spicing up your dummy text

You may have noticed I don't use the normal "Lorem Ipsum" dummy text in the preceding example. For personal projects and experiments, I like to add some spice and use interesting text generators. Here, I am using Coffee Ipsum from http://coffeeipsum.com/. Visit the Meet the Ipsums website (http://meettheipsums.com/) to add some fun to your workflow. Use it with caution though; clients may not have a sense of humor that is similar to yours.

To keep a website responsive, stay away from using pixel widths on elements. Instead use ems and percentages. We should use ems for font sizes too. CSS Guru, Chris Coyier, in "Why Ems?" (https://css-tricks.com/why-ems/), sums up why we should do this.

"Let's say you look through your stylesheet and find 50 different font-size declarations in px. That's 50 places you need to change that font size through a media query when the screen size changes. That's 50 suck points." | ||

| --Chris Coyier | ||

With ems, all sizes set are relative to its parent's font size. Let's say there is an h1 tag whose parent is a div tag; the font size of h1 will be relative to the div font size. If we increased the div tag's font size, the h1 font size would increase also. Another value is root ems, or rems. Rems are relative always to the body tag's font size. For both, if we needed to increase the font size overall on smaller screens, we can use media queries to change the body element's font size.

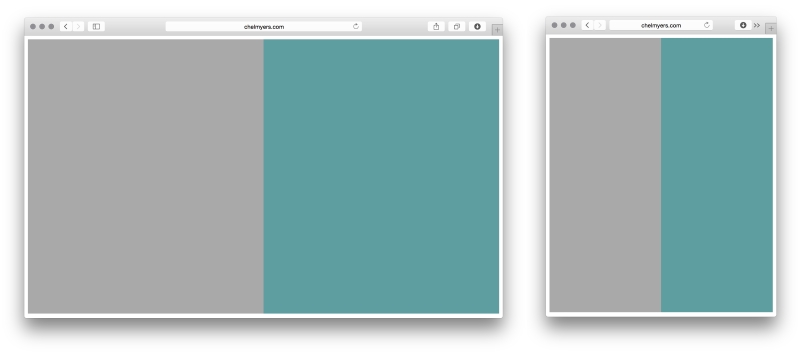

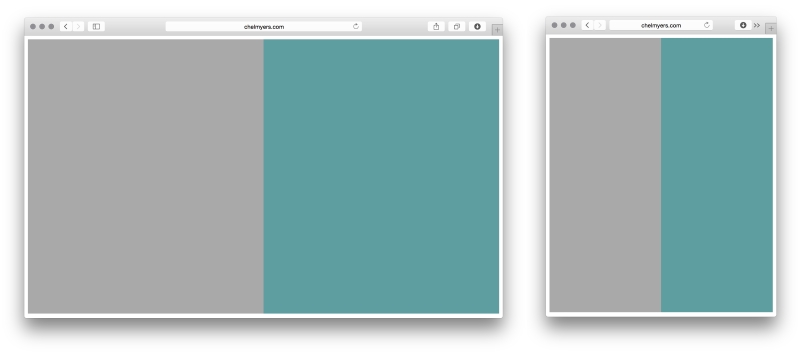

By setting the width of sections on a page using percentages instead of pixels, we can see the natural fluidity of web pages. The following is an example of a two-column layout using only percentages. This may seem familiar to you.

HTML

<div class="col-1"> </div> <div class="col-2"> </div>

CSS

.col-1, .col-2 {

margin:0;

float: left;

width: 50%;

height: 600px;

}

.col-1 {

background-color: darkgray;

}

.col-2 {

background-color: cadetblue;

}Here, we are using the .col-1 and .col-2 classes (col is short for column) to align the sections and set the widths. We then use these classes to set background colors as well. We also gave the columns a height so that we can actually see them appear on the page (the default height would be 0 pixels).

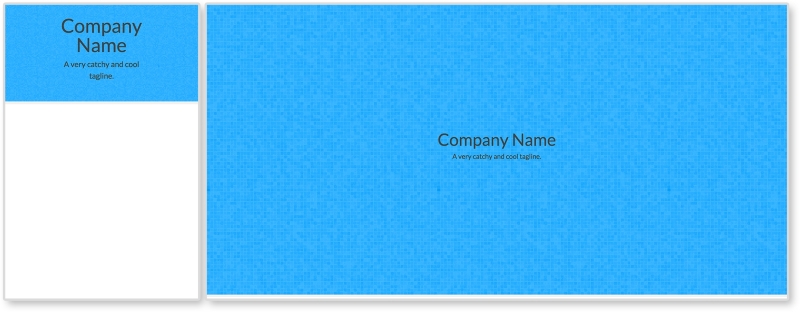

You may recall categorizing website layouts into three types: fixed, fluid, and adaptive. A website locked at 960 pixels wide has a fixed layout. Percentage-based layouts, such as the preceding example, are fluid. Adaptive layouts are fixed layouts that use media queries to change at different screen sizes. Now, you might be thinking that adaptive layouts are the same as responsive layouts. Even the terms for each are similar. Responsive layouts do use media queries too, but their layouts are based on percentages instead of being fixed. Responsive layouts scale based on a percentage-based grid. Adaptive layouts only snap to new layouts at different sizes.

Creating quick examples

Remembering all the CSS colors and creating images for examples sites such as these can be a hassle. Use placeholder sites such as Placehold.it (http://placehold.it/) and PlaceKitten (http://placekitten.com/) to generate images quickly. I also visit http://colours.neilorangepeel.com/ to help remember the CSS colors and pick the right shade for the example.

Fixed, fluid, adaptive, and responsive are the four main categories of layouts for websites. Responsive layouts can be categorized even further. In 2012, Luke Wroblewski released an article titled Multi-Device Layout Patterns (http://www.lukew.com/ff/entry.asp?1514). Here, Luke categorizes responsive layouts under 5 labels; tiny tweaks, mostly fluid, column drop, layout shifter, and off canvas. His categorizations caught on and are now commonly used when talking about RWD layout patterns. Together, we will review these patterns and see how they are made.

You can view all these patterns live at http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/layouts/.

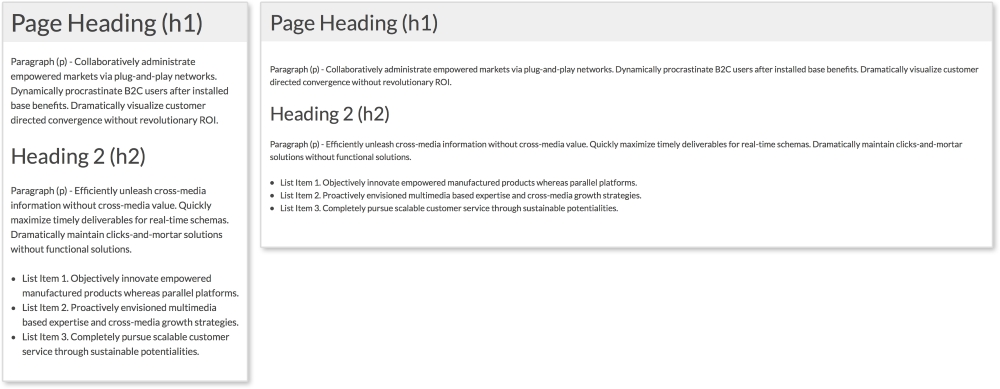

Let's start by looking at the easiest layout pattern. This pattern doesn't require much effort. The layout is similar to the example reviewed under a past section, The Web is naturally responsive. It is typically a single-column web page.

Our layout has a header and a section containing the site's content. Since these elements automatically stretch and scale to the browser's width, only some minor changes are needed to make it more mobile-friendly.

HTML

<header>

<h1>Page Heading (h1)</h1>

</header>

<section>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Collaboratively administrate empowered...<p>

<h2>Heading 2 (h2)</h2>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Efficiently unleash cross-media...</p>

<ul>

<li>List Item 1. Objectively innovate empowered...</li>

<li>List Item 2. Proactively envisioned multimedia..</li>

<li>List Item 3. Completely pursue scalable customer...</li>

</ul>

</section>The header section contains an h1 tag while a section tag contains the rest of the page's content. Inside the section tag, we have a second heading, paragraphs, and an unordered list.

CSS

body {

font-size: 1em;

}

header, section {

padding:0.75em;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) {

body {

font-size: 0.875em;

}

header, section {

padding:1em;

margin-bottom:1em;

}

}

Here, we have the styles for this layout with the media query highlighted. Now, remember we are styling these patterns mobile first; meaning the smallest screen-size styles are applied first and built on top of. This layout already scales width-wise the way we want it to, so we don't have to do much. All we are doing with CSS here is changing the font and padding sizes to make reading easier on smaller screens. I am setting font-size: 1em initially for the body and then decreasing it to font-size: 0.875em on screens larger than 600px. I am also setting the padding of the page (using the header and section tags) to a smaller value at first and increasing it on larger screens. This way there is more space for the content on smaller screens.

Since I am using ems instead of pixels for these examples, changing the font-size property on the body tag scales everything being styled with ems. Now, my whole typography system shifts by changing only one property. The padding and margin are scaling as well. That's why using ems in responsive design is so helpful!

You can view this pattern live at http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/layouts/index.html#tiny-tweaks.

Let's have a look at the pros and cons of this pattern:

Pros:

Cons:

If you want to start creating responsive websites, this is the place to start. The main issue with this layout is that it cannot hold a lot of content and stay organized. Since the layout is so simple, all the page elements are stacked on top of each other. Our example only has a few things on the page. What happens though when I want a big navigation, an image gallery, and some more text? Creating a more complex layout would accommodate these elements better. This is why seeing a "tiny tweaks" layout is rare, especially as the home page for larger organizations. They are typically used as landing pages where more content lies in a different part of the site.

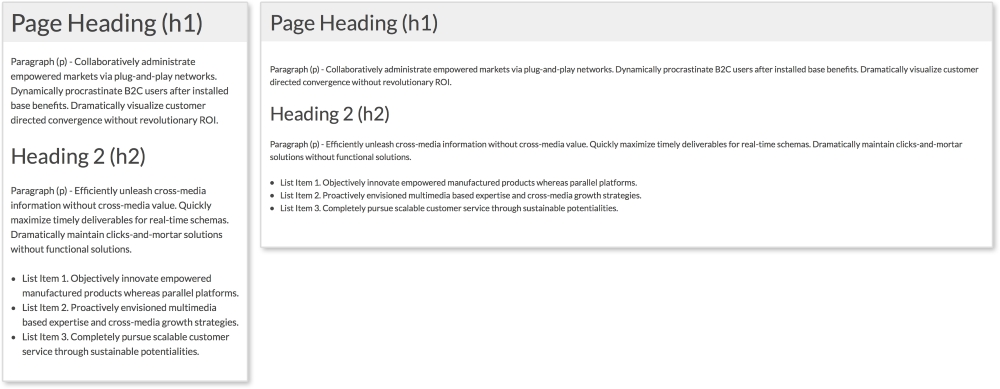

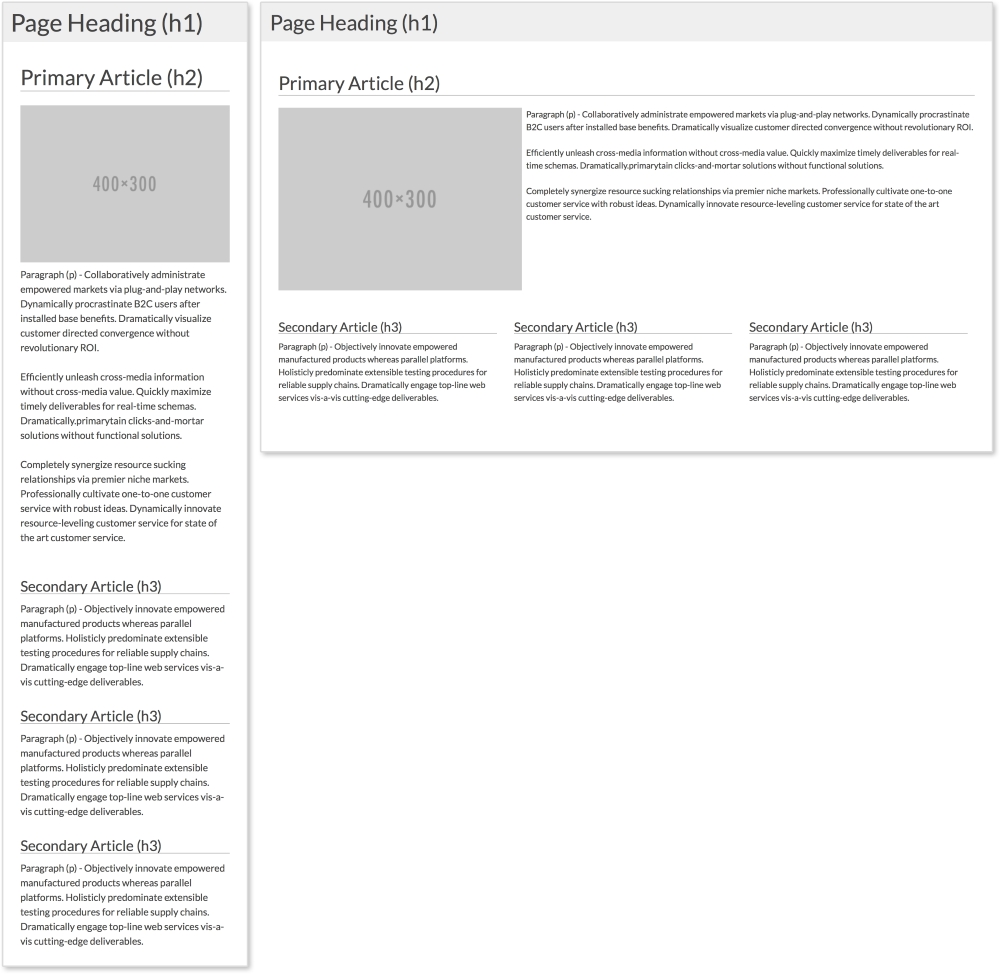

Like the tiny tweaks layout, mostly fluid layouts are simple to implement as well. As seen in the following example, the layout is based on a fluid grid system that shifts depending on the viewport's size. Usually, the layout is comprised of columns that stack on smaller screens. The mostly fluid layout is the most popular of the ones presented in this chapter.

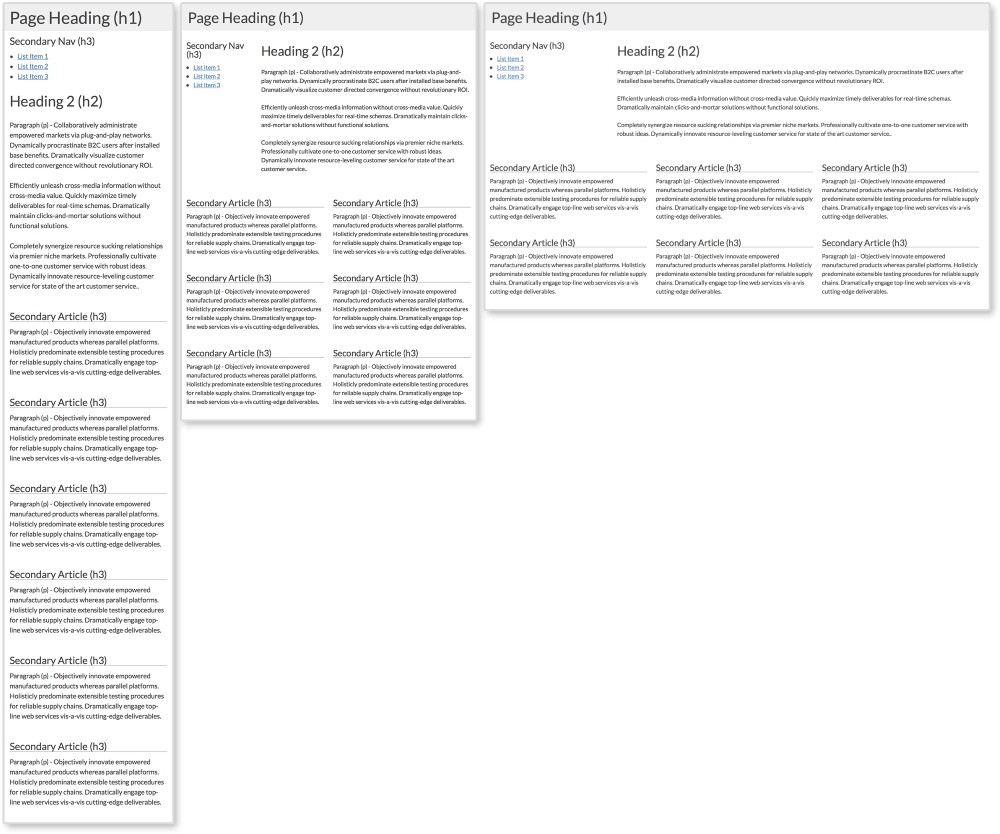

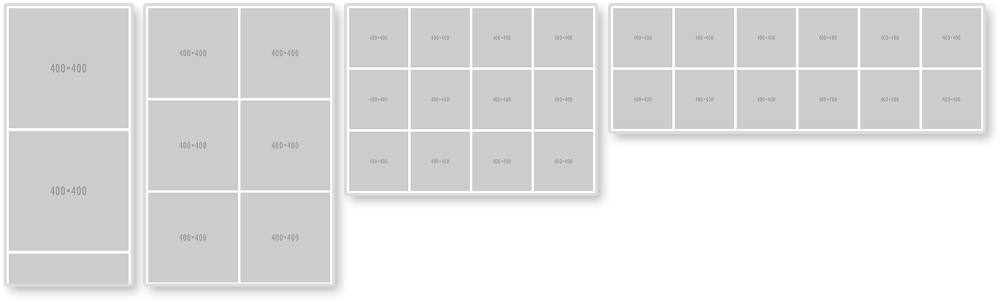

The preceding example has a primary article that spans the full width of the page and three smaller secondary articles. On smaller screens, the primary image centers itself on screen, while the three columns stack on top of each other.

HTML

<header>

<h1>Page Heading (h1)</h1>

</header>

<section class="clearfix">

<!--Primary Article -->

<article class="primary">

<h2>Primary Article (h2)</h2>

<img src="http://placehold.it/400x300" alt="">

<p>Paragraph (p) - Collaboratively administrate...</p>

<p>Efficiently unleash cross-media information without...</p>

<p>Completely synergize resource sucking relationships via premier niche markets. Professionally cultivate one-to-one...</p>

</article>

<!-- Secondary Articles -->

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

</section>Again in this example, we have a header. Next, we have the primary article with a class of primary, a heading, an image, and three paragraphs. After the primary article, we have the secondary articles. Each has a class of secondary, a heading, and a paragraph. To apply styles to all the articles, we can use the article tag.

The clearfix method

You may have noticed that the section tag has a class of clearfix. This is a more modern method of ensuring elements span the full height of their floated children and next elements do not float up next their content. In pattern-style.css, .clearfix has the following styles:

.clearfix:after {

content: "";

display: table;

clear: both;

}To learn more about this method, visit https://css-tricks.com/snippets/css/clear-fix/.

CSS

The mostly fluid example uses the same CSS as tiny tweaks, but adds the following styles. Let's look at the mobile styles first:

article {

padding: 1em;

}

article img {

width: 100%;

height: auto;

max-width: 400px;

display: block;

margin: 0 auto;

}

.primary {

padding-top:0;

}

.secondary p {

margin-bottom:0;

}

h2, h3, h4 {

border-bottom: 1px solid darkgray;

}The first important part is to make sure static width elements, such as images, scale with their columns. Here, we set all images inside the article to width: 100% and height: auto. We then give them a max-width and use margin: 0 auto and display: block to center them. Everything else except what is in the media query is there just for styling. The media query then looks like this:

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) {

.primary img {

float:left;

margin: 0 0.5em 0.5em 0;

}

.secondary {

width: 33.33%;

float: left;

}

}Inside the media query, we are setting the image in the primary article to float: left at 600px or larger. This lets the text wrap around it, so we add a margin as well. Next, we set the width of each secondary article to 33.33% and apply float: left. The articles now appear on the same row. In the pattern-style.css file, we are using the universal selector, *, to apply box-sizing: border-box to all the elements. If you are familiar with the box model, you know that naturally if we set an element to be 100px wide, we then add 10px padding; the element will then be 120px wide (100px for the content and 10px on each side). Using box-sizing: border-box allows us to keep our set widths and have the padding subtract from the content area.

You can view this pattern live at http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/layouts/index.html#mostly-fluid.

Let's have a look at the pros and cons of this pattern:

Pros:

Cons:

You will find this in a lot of responsive websites: content just get stacked on top of each other on small screens. This means you need to know how to prioritize your content. If the content you really want the user to see is not towards the top of the screen on smaller devices, then you are gambling the user will not overlook it while scrolling. This is the only problem with the mostly fluid layout. Besides this, the mostly fluid layout is easy to create and easy to use, and therefore very popular.

Reordering page elements

Now if you are thinking something like, "Hey, can't I reorder the content on the page to solve this issue?" Well, yes, you can! A few years ago, there was no easy solution to this. Now, you can use the flexbox property (labeled as a W3C Last Call Working Draft). Arranging elements on the page using flexbox allows you to also swap their order just using CSS! Although we won't be using it in this book, I highly recommend checking it out. CSS Tricks has a great article about it at https://css-tricks.com/snippets/css/a-guide-to-flexbox/.

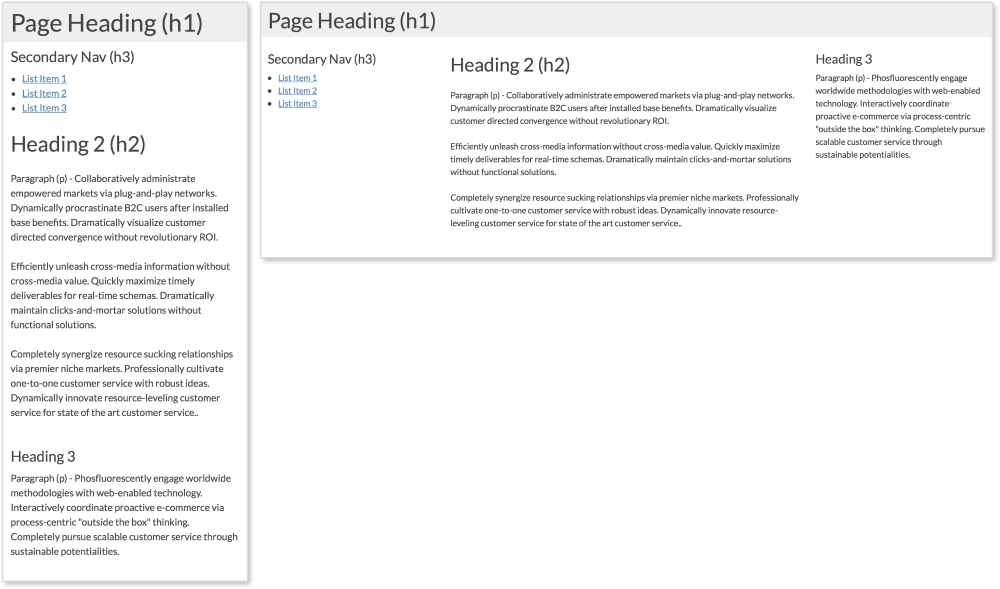

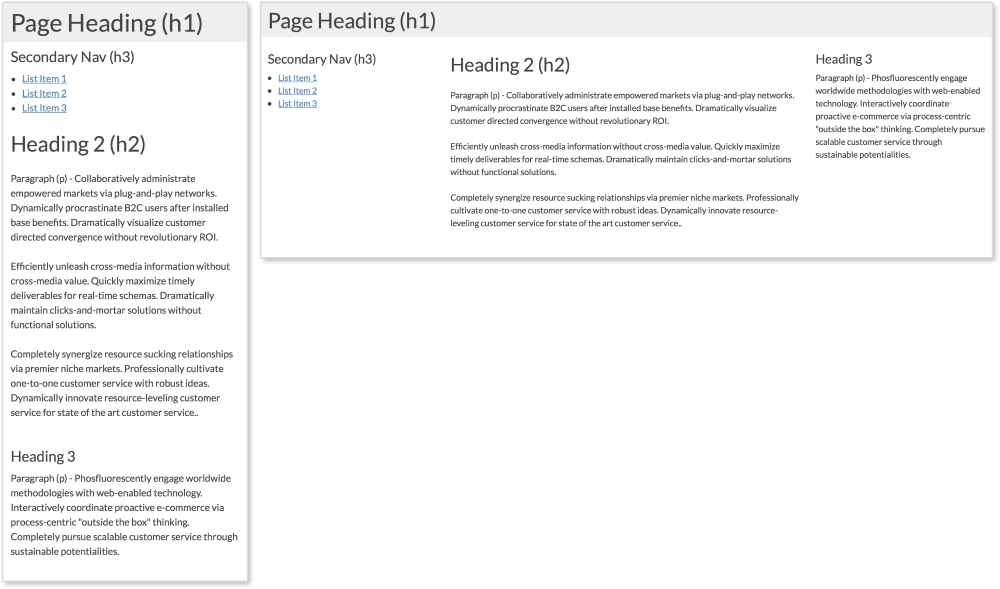

Websites can have side columns that contain additional information. We are used to seeing secondary navigation on the sides of pages. The column drop layout accommodates websites that utilize sidebar modules such as these. Normally, on larger screens, the columns are displayed while, on smaller screens, all sections are stacked on top of each other. Navigation columns are typically placed on top so the user can easily access them. Our example here has two columns and a section for the main content.

HTML

<header>

<h1>Page Heading (h1)</h1>

</header>

<aside>

<h3>Secondary Nav (h3)</h3>

<ul>

<li><a href="#">List Item 1</a></li>

<li><a href="#">List Item 2</a></li>

<li><a href="#">List Item 3</a></li>

</ul>

</aside>

<section>

<h2>Heading 2 (h2)</h2>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Collaboratively administrate empowered...</p>

<p>Efficiently unleash cross-media information without...</p>

<p>Completely synergize resource sucking relationships...</p>

</section>

<aside>

<h3>Heading 3</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Phosfluorescently engage worldwide...</p>

</aside>This pattern has three columns; two sidebars and one main column. The first aside holds what would be a secondary navigation, while the second holds complementary information.

CSS

aside, section, header {

padding: 0.75em;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) {

aside {

width: 25%;

}

section {

width: 50%;

}

aside, section {

float: left;

}

}First, we are giving all three columns padding. All that is left to make this pattern work is a media query to set the width of the columns on larger screens. At 600px or higher, we are applying width: 25% to both aside tags and width: 50% to the main section tag. We are then applying float: left to both so they appear next to each other.

You can view this pattern live at http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/layouts/index.html#column-drop.

Let's have a look at the pros and cons of this pattern:

Pros:

Cons:

You may notice that the column drop and mostly fluid layouts have the same negative characteristic. All content just gets stacked in one column. As you can see, though, minimal CSS is needed to make this work. Because of this, the pattern is a great solution for various kinds of content.

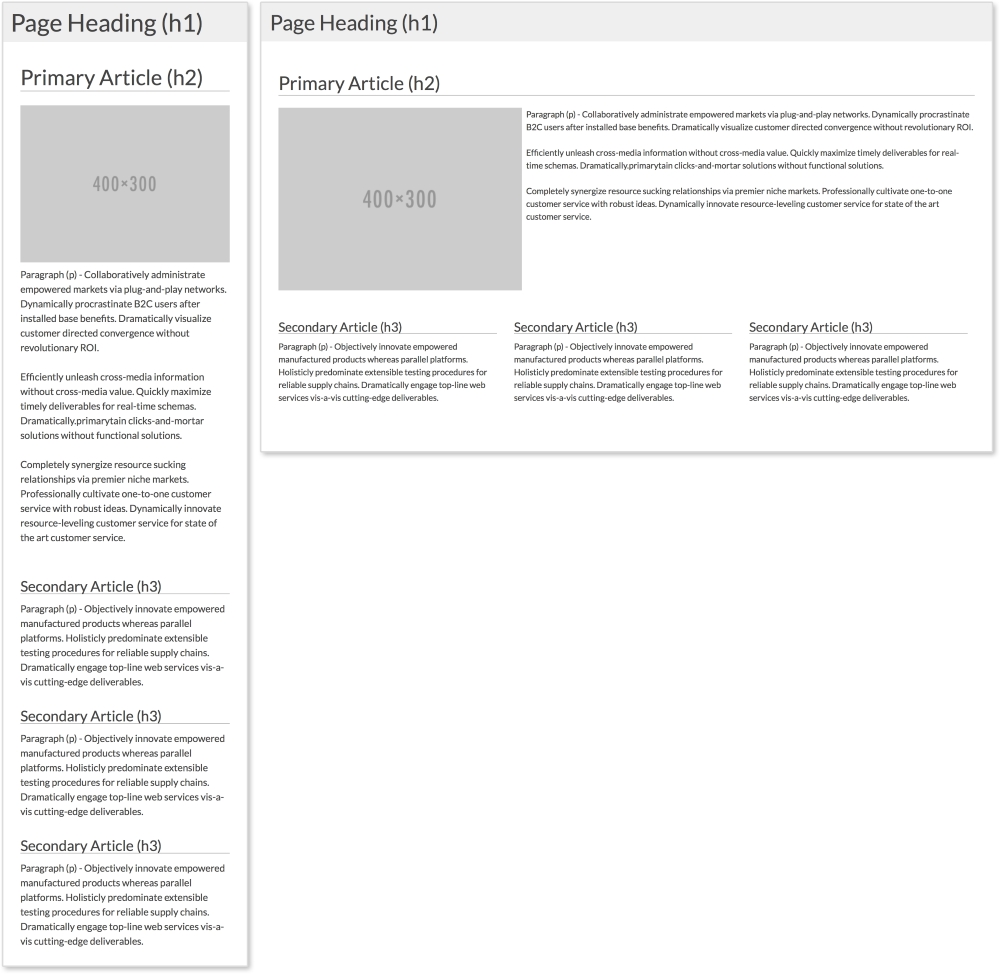

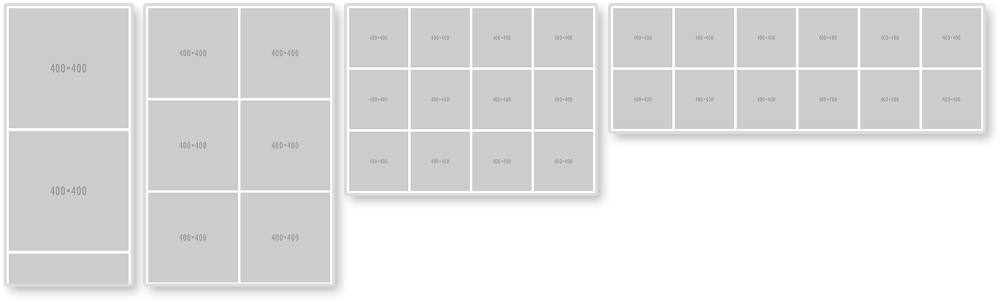

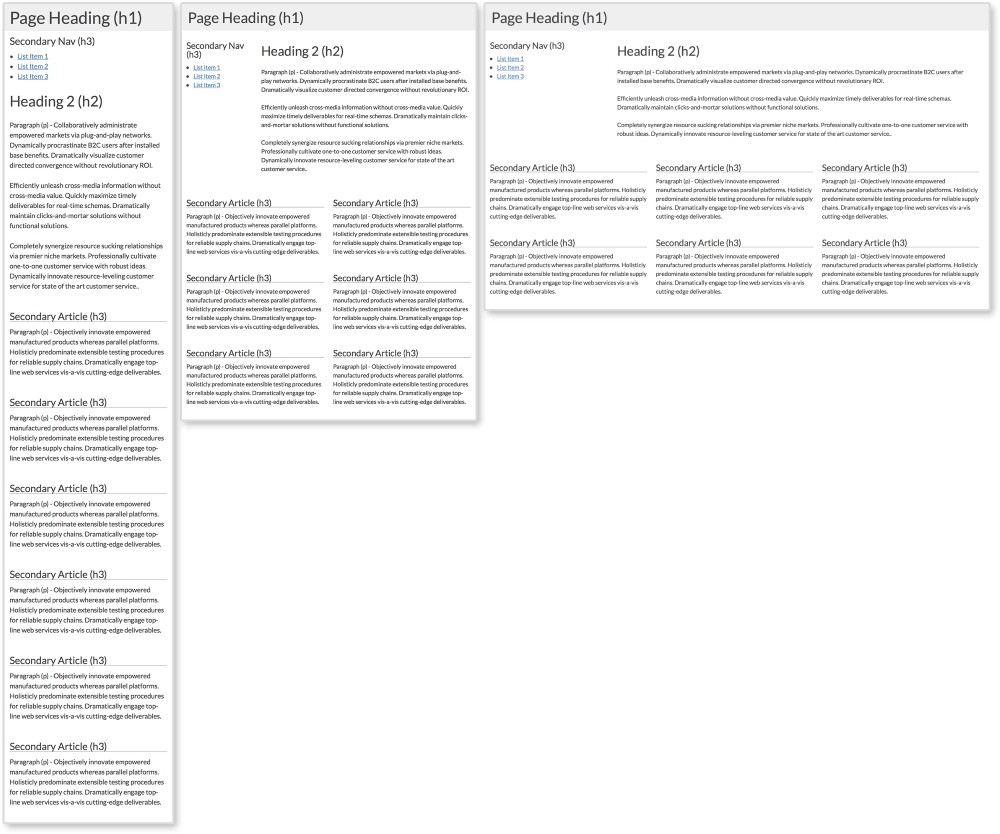

The layout shifter pattern starts to get a little more complicated. It is similar to the last two examples, but requires a little more effort. This pattern changes the most for different viewport sizes. It usually has a different layout for small, medium, and large screen sizes. The example we are using changes at 600px and 800px.

This pattern has three different layouts—small, medium, and large:

The layout shifter pattern with a one, two, and three column layout

HTML

<header>

<h1>Page Heading (h1)</h1>

</header>

<aside>

<h3>Secondary Nav (h3)</h3>

<ul>

<li><a href="#">List Item 1</a></li>

<li><a href="#">List Item 2</a></li>

<li><a href="#">List Item 3</a></li>

</ul>

</aside>

<section>

<h2>Heading 2 (h2)</h2>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Collaboratively administrate empowered...</p>

<p>Efficiently unleash cross-media information without...</p>

<p>Completely synergize resource sucking relationships...</p>

</section>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p> Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p> Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>

<article class="secondary">

<h3>Secondary Article (h3)</h3>

<p> Paragraph (p) - Objectively innovate empowered...</p>

</article>Here again we have a side column, a main section, and secondary articles. Having six items on a page is great for the layout because six is divisible by two and three. This means we can have three equal rows of two each and two rows of three. In the layout shifter pattern, we will do just that. We will also repeat what we did for the column drop pattern and shift the aside tag's position as well:

CSS

.secondary h3 {

border-bottom: 1px solid darkgray;

}

@media screen and (min-width:600px) {

aside {

width: 25%;

}

section {

width: 75%;

}

.secondary {

width: 50%;

}

aside, section, .secondary {

float: left;

}

}

@media screen and (min-width:800px) {

.secondary {

width: 33.33%;

}

}Now we are seeing two media queries altering the page's layout. The first is changing the width of the aside tag and the section tag for screen sizes larger than 600px. Here, they are now split 25/75. Next, we are setting each secondary article to take up half the screen creating three rows of two. Lastly, for this media query, we set float: left to all three elements so they appear on the same row.

The next media query kicks in on screen sizes larger than 800px. The only thing we are changing here is how many secondary articles appear in a row. Setting the width of each secondary article to 33.33% creates two rows of three.

You can view this pattern live at http://chelmyers.github.io/RPL/layouts/index.html#layout-shift.

Let's have a look at the pros and cons of this pattern:

Pros:

Cons:

Already we can see these patterns starting to overlap and merge. The layout shifter does start to get more complex, but this means more things can be done with it. If we can only make one media query at one size, RWD will not be as powerful. But with this ability, we can really start reworking layouts to appear beautifully across all screen sizes.

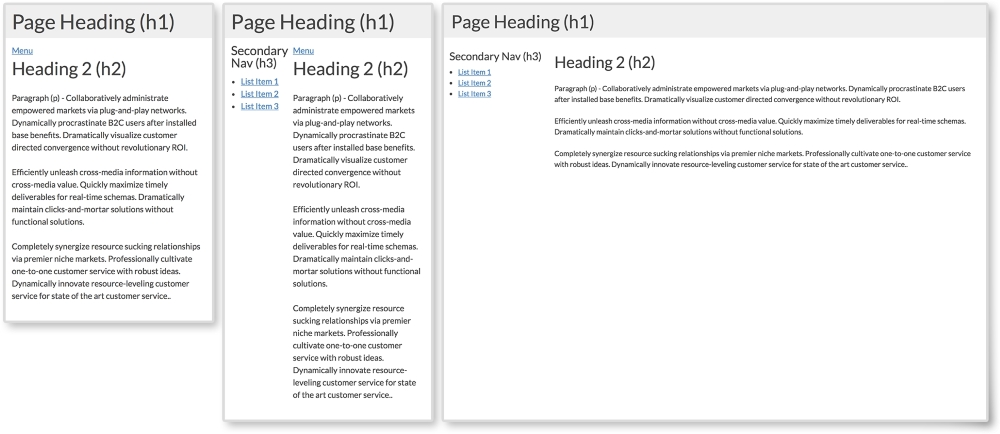

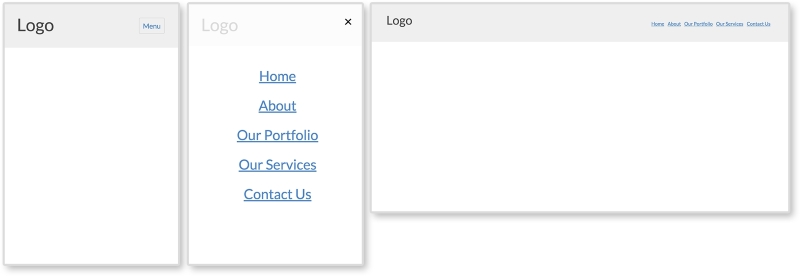

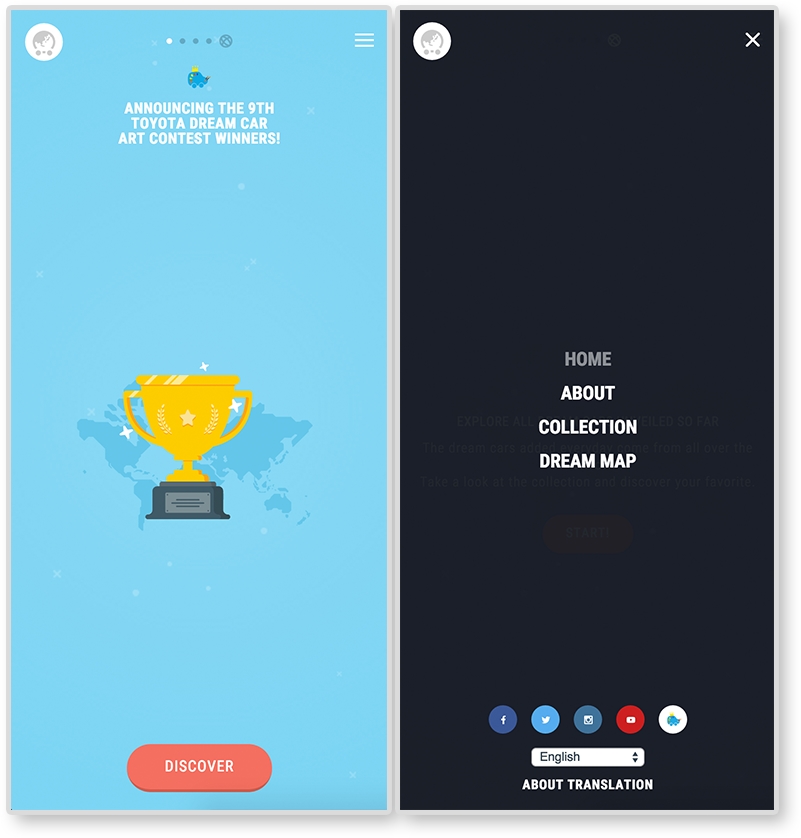

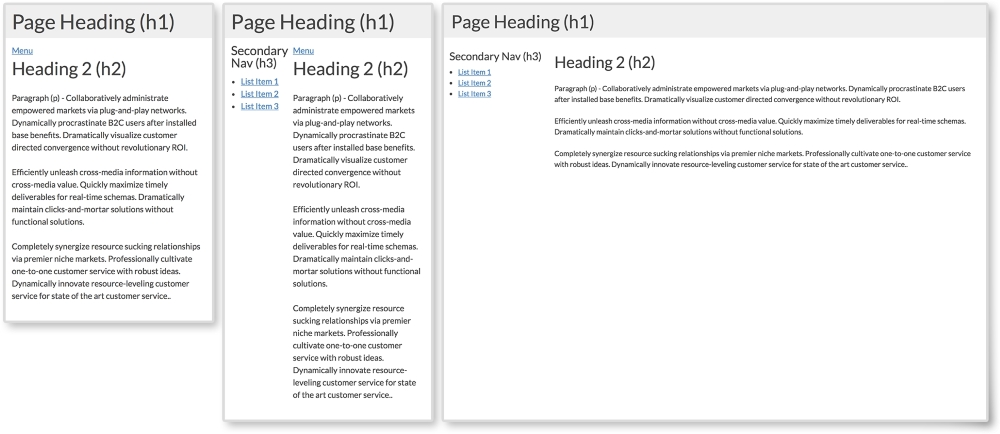

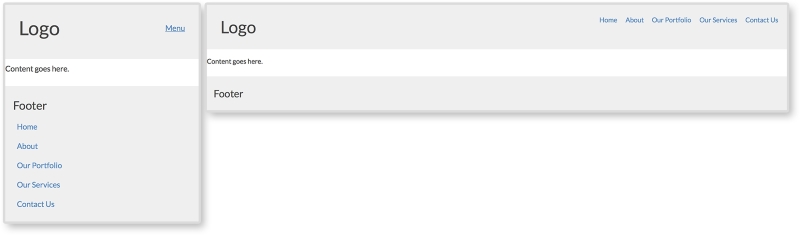

The biggest problem we have seen with these patterns so far is that most of them put all the content in one column at smaller sizes. Off canvas layouts are a solution to this. You may have used an off canvas layout in a mobile app. Usually, they have menus in columns that slide in from the right or left when opened. This doesn't mean we don't see this on the Web. Off canvas layouts require JavaScript (JS), though. There are purely CSS solutions, but these are hacks and come with their own problems.

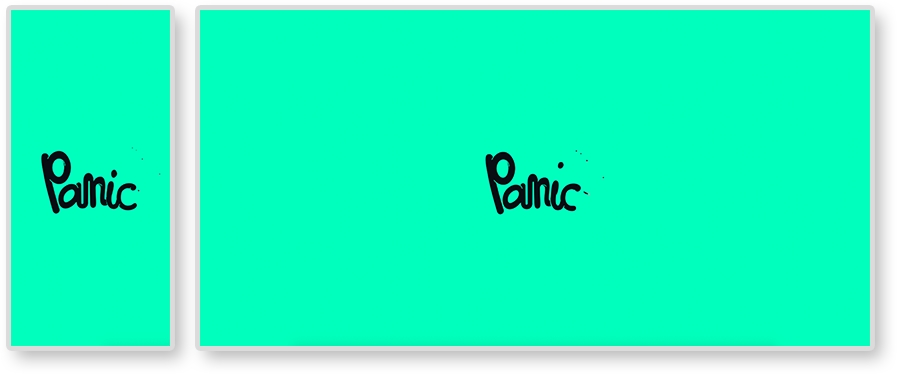

The first two screenshots show what secondary navigation looks like when closed and opened on smaller screens. To toggle the navigation in this pattern, we will detect clicking on the Menu button with JS.

HTML

<body>

<header>

<h1>Page Heading (h1)</h1>

</header>

<aside>

<h3>Secondary Nav (h3)</h3>

<ul>

<li><a href="#">List Item 1</a></li>

<li><a href="#">List Item 2</a></li>

<li><a href="#">List Item 3</a></li>

</ul>

</aside>

<section>

<button class="menu-toggle">Menu</button>

<h2>Heading 2 (h2)</h2>

<p>Paragraph (p) - Collaboratively administrate...</p>

<p>Efficiently unleash cross-media information without...</p>

<p>Completely synergize resource sucking relationships...</p>

</section>

</body>This layout's elements are the same as we've been using in other examples. The only difference is the Menu link. Here, I added a button with class="menu-toggle". Again, this will come into play when we get into the JS.

CSS

aside {

display: none;

width: 30%;

max-width:200px;

}

section, aside {

float: left;

}

.open aside{

display: block;

}

.open section {

width: 70%;

}

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) {

.menu-toggle {

display: none;

}

aside {

display: block;

}

section {

width: 70%;

}

}First, I am hiding the aside tag using display: none since we want it to be "off canvas" on smaller screens. Notice that we are not really having the aside element pushed off screen. Instead, we will create the illusion it is waiting right where we can't see it.

The next important style is for the open class. You may have noticed that we are not using the open class yet in the HTML. We will be! Using JS, we will add and remove the class from the body element. When the open class is added, display: none will change to display: block for the aside. Also, the main section will shrink to a width of 75%.

On larger screens above 600px, we set aside to display: block, so it doesn't matter if there is or is not a class of open on the body tag; the aside element will show. We also hide the Menu toggle link since we will no longer need it.

JavaScript

var menuTog = document.getElementsByClassName("menu-toggle")[0];

menuTog.onclick = function() {

document.getElementsByTagName('body')[0].classList.toggle('open');

}

Out of all the layout patterns, this requires the most complex code. Don't worry though; this is actually very simple JavaScript! If you don't know JS, you can just use the code provided. I recommend reading the following explanation though to understand what is going on. Don't be afraid of JS. It is very easy to learn.

This snippet of JS first creates a variable, menuTog, that stores the first instance of the class menu-toggle. Next, we will create a function to trigger when the menu button is clicked. Inside this function, we are using the toggle method. We want to use this to toggle the open class on body. If body does not have a class of open, it will add it. If it already does, it will remove it. The CSS then does the rest and changes the styles depending on whether the open class is present.

Let's have a look at the pros and cons of this pattern:

Pros:

Cons:

If you have never used JS before, this pattern can be daunting. You have all the code though, so why not experiment? The off canvas example is definitely the most complex of the five, but it does solve the issue of using just one column on small screens. If you get comfortable with JS and start using it a lot, look into JS libraries, such as jQuery, to make projects easier.

Just by reviewing these patterns, we can already see repetition and combination. For more complex systems, these patterns can be combined in an infinite amount of ways. Of course, infinity can get a little messy.

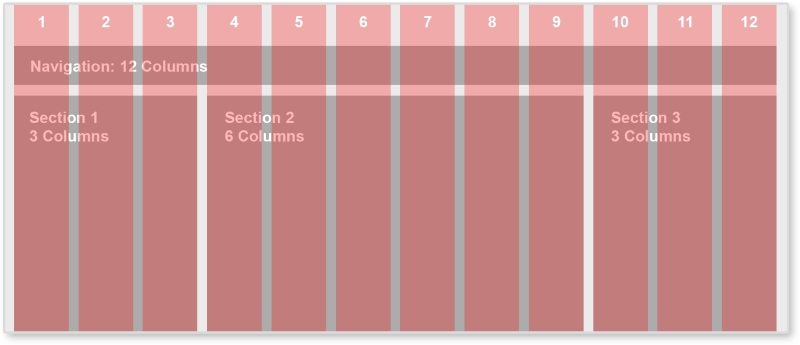

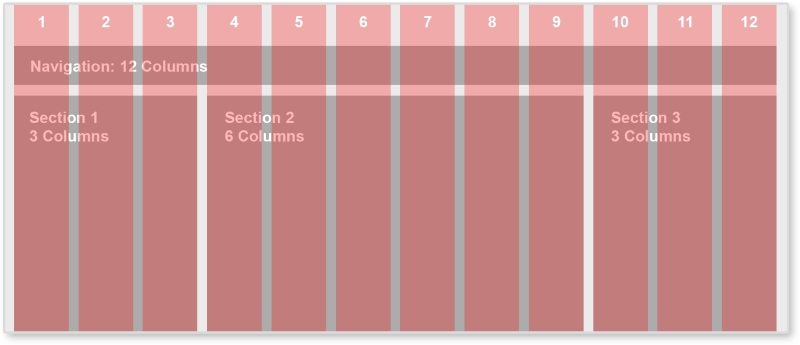

When designing a website, we don't place content, modules, and text whenever we want. Websites such as these may look more like a cubist painting than a functional site. Website designs should be simple, usable, and approachable. A way to maintain order throughout a website is to base templates and pages off a grid system. The grid system is comprised of columns, typically in the range of 10-16 on large screens. Elements on a template are then aligned with the edges of the columns to bring order to the page.

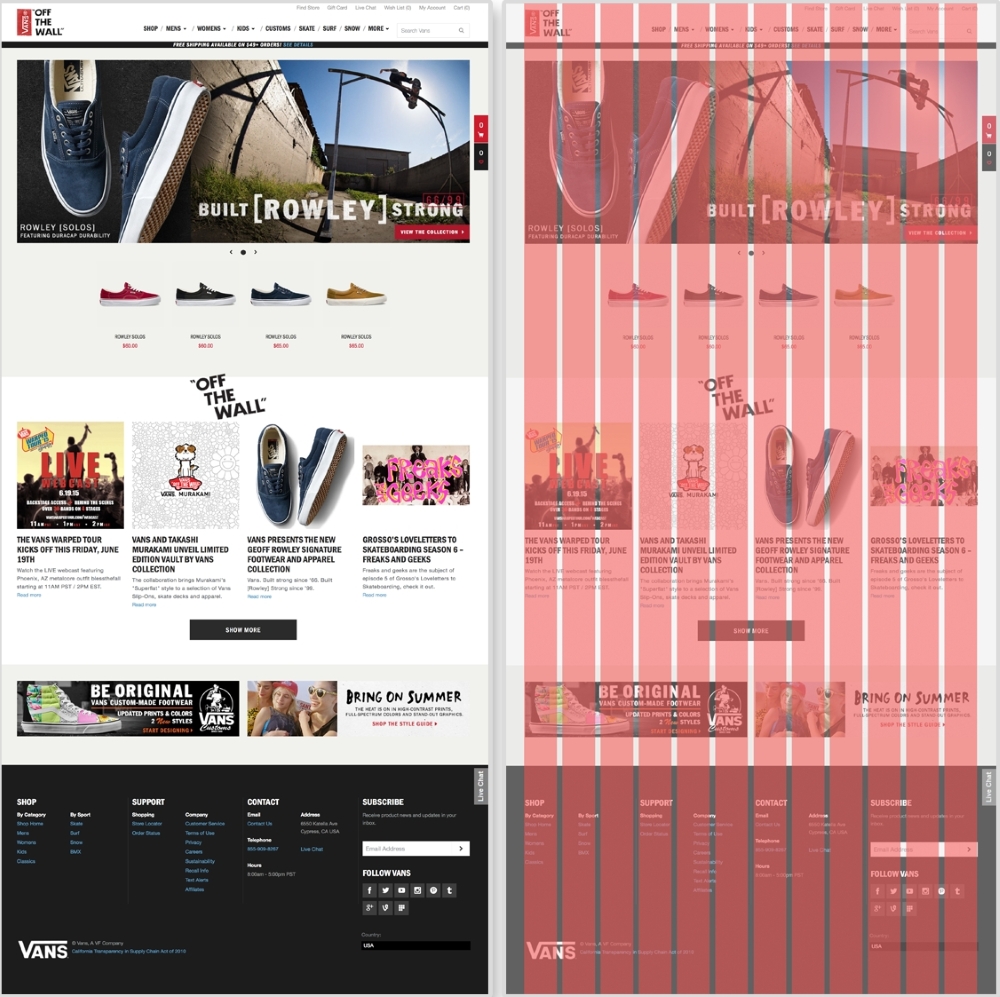

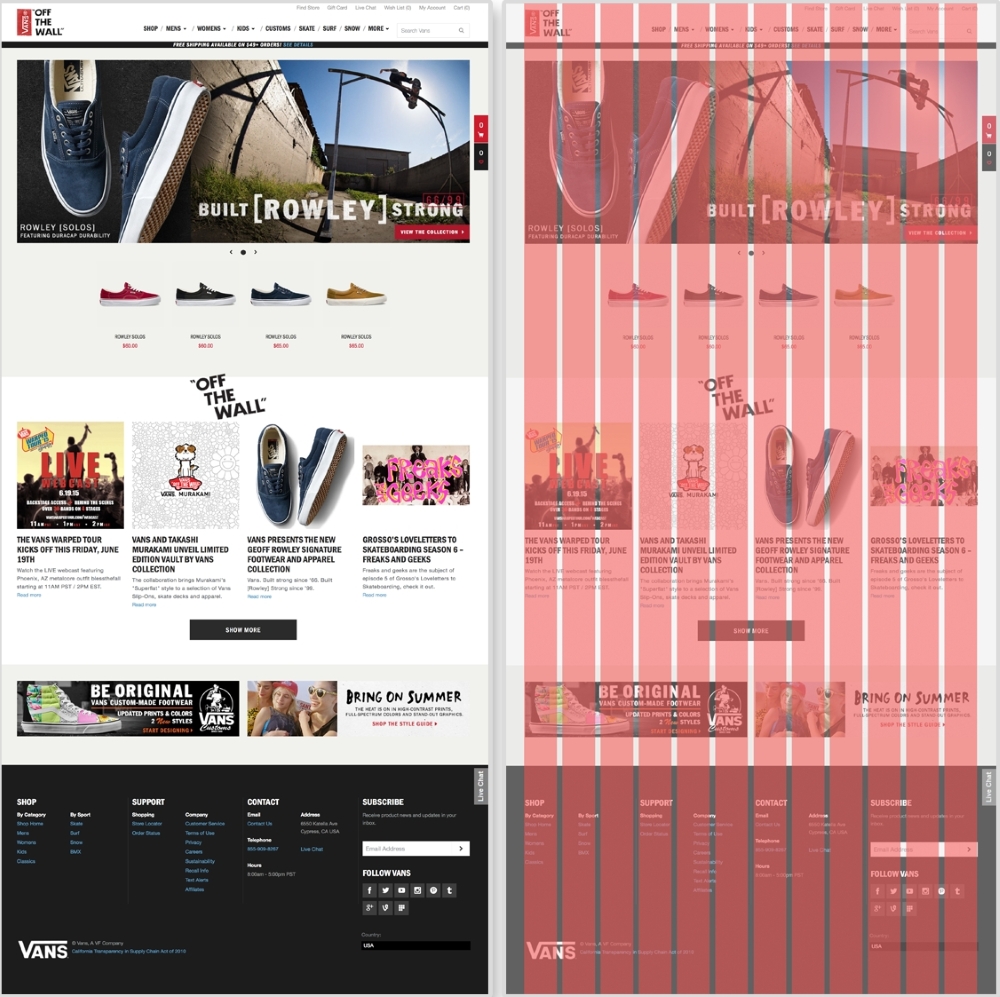

Between each red column, there is space called the gutter. By always keeping this same sized space empty between elements, the page has breathing room and white space. The famous shoe brand, Vans, implements a 12-column grid system.

The Vans' website (http://www.vans.com/) with an example grid system

On Vans' home page, different sections of the page line up with the grid. The carousel spans the full width of the grid system, taking up 12 columns. The featured shoes underneath only take up two columns each. The articles under the OFF THE WALL section spans three columns each. Even the BE ORIGINAL banner at the bottom of the site lies on the grid. We see not only each section lined up with the grid system, but the images and text within each as well.

We don't have to create these grids from scratch though. Back when websites were acceptably one size and static, a popular tool to create these grid systems was 960 Grid System (http://960.gs/). This tool provides grid overlays in Photoshop, Flash, Fireworks, Illustrator, and many others. Each overlay is a 12, 16, or 24-column grid system with a 960-pixel width. Along with each column version, 960 Grid System also provides all the CSS needed to have page elements span across a certain number of columns.

We are not designing websites that are only 960-pixel wide. For a responsive website, we can use a responsive grid system. The patterns reviewed in this book can all be applied projects using a responsive grid system. Grid systems can help you determine how wide a pattern should span. With a responsive grid system, even though every column should be the same size, this one size can be a percentage and scale. This means that, on smaller screens, each column's width is narrower. Also with media queries, columns can be dropped too. A 12-column layout can become a 6-column one on smaller devices. Determining how a responsive grid system scales down for a project can help figure out how the project's patterns scale down too.

There are again tools already out there that help us create these responsive grid systems. Gridpak (http://gridpak.com/) lets us create a responsive grid system right there in the browser. By default, each column, column padding, and gutter value is a percentage. This allows the system to scale up and down depending on the browser's size. We can even add breakpoints to the system and change each value. When we download the file, Gridpak provides a .png file for design and the CSS files for implementation.

Check out other responsive grid systems such as Golden Grid System (http://goldengridsystem.com/) and Responsive Grid System (http://www.responsivegridsystem.com/) to find one that best fits your needs.

Making sure you have the right layout for your content is an important task. Each layout pattern we reviewed has its own strengths and weaknesses. It is crucial that you understand a website's content and can properly prioritize it to meet the user's and client's needs. With this information, you can begin to see what pattern suits your project. Of course, not every site on the Web looks like these patterns. These layout patterns have a very simple design, but as you can see from the live example sections, they share their core functionality. You can use these patterns as a starting point to begin figuring out ways to move content around across screens sizes. When you are done with this, move onto the next chapter to learn more about connecting these pages and their layouts with a responsive navigation.

When looking for information, rarely do we open up a website and land exactly on the page we were looking for. Maybe if we are lucky, whatever we are trying to find is featured on the home page. But if we are looking for contact information, operation hours, or a specific article, our luck runs out. When we are searching for information, we typically use a website's navigation to traverse through the pages.

Main navigations can range from just a few links to a collection of all the pages you can access on a site. How small or large they are depends on the size of the site. Websites such as NASA have a wealth of information available to the public and need an extensive navigation to help users find what they are looking for. Smaller websites, such as personal portfolio sites, have smaller navigations with maybe three to six links. To develop for this wide range of navigation sizes, there are several responsive navigation patterns that we can use. In this chapter, we will review:

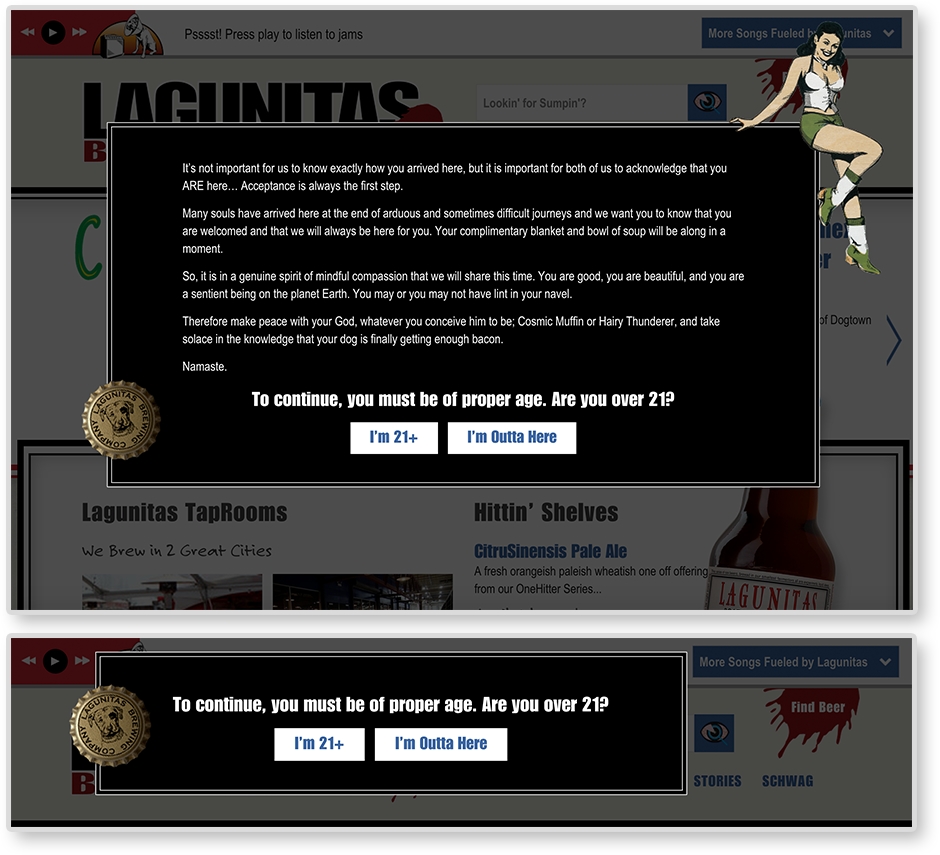

When creating a responsive website, you do not have the freedom to jam as many links in the main navigation as you please. Even if you did have the luxury of screen space guaranteed, you still should never do that. Great navigation considers what content the user needs to get to and provides them with an easy path to get to it. Navigations are a manifestation of a website's information architecture (IA). Main navigations are a high-level summary of a website's organization. Each project's IA will be different. Larger projects can even have a person completely dedicated to IA and content strategy.

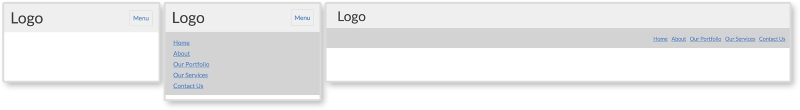

Unfortunately, we don't always have an information architect on our team or we are working alone. This does not mean we should skip IA though. RWD adds another constraint when planning out the IA of a project. When you are developing a navigation for your responsive website, first think of what the navigation will look like on smaller screens. Like a page's layout on small screens, one strategy for navigation is to stack their items on top of each other. As mentioned in the previous chapter, though, just stacking items of top of each other makes for one long skinny page that can potentially push important content down. To avoid a long navigation on smaller devices, prioritize what is actually included. This small screen constraint can jump-start your IA planning. Make sure that every item included in the navigation is important to the types of users who visit the website. Unnecessary items in the navigation will clutter it and obscure the crucial content of the site. Of course, sometimes long navigations cannot be avoided. Every project you work on will probably be a different size. This chapter will equip you with solutions for developing navigations of any size.

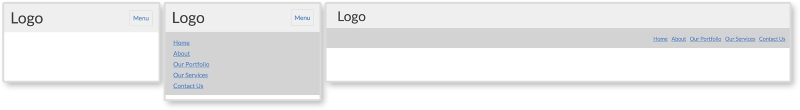

Before we get into navigation patterns, I want to take a moment to talk about a controversial but widely used tool for responsive navigations—the hamburger icon. By now, you either have at least seen it online or used it in your own web designs. Looking at the following image, you can see different versions of this icon. Just because it is so widely used though doesn't mean it should be our go-to solution for responsive navigations.

The hamburger icon is not new; it has been around for over 30 years. It's called the hamburger icon because those three little bars look like a hamburger's top bun, patty, and bottom bun. This meat-themed UI element is actually the list icon. Each bar doesn't represent a piece of food, but instead a list item. Typically, clicking this icon toggles the navigation's visibility.

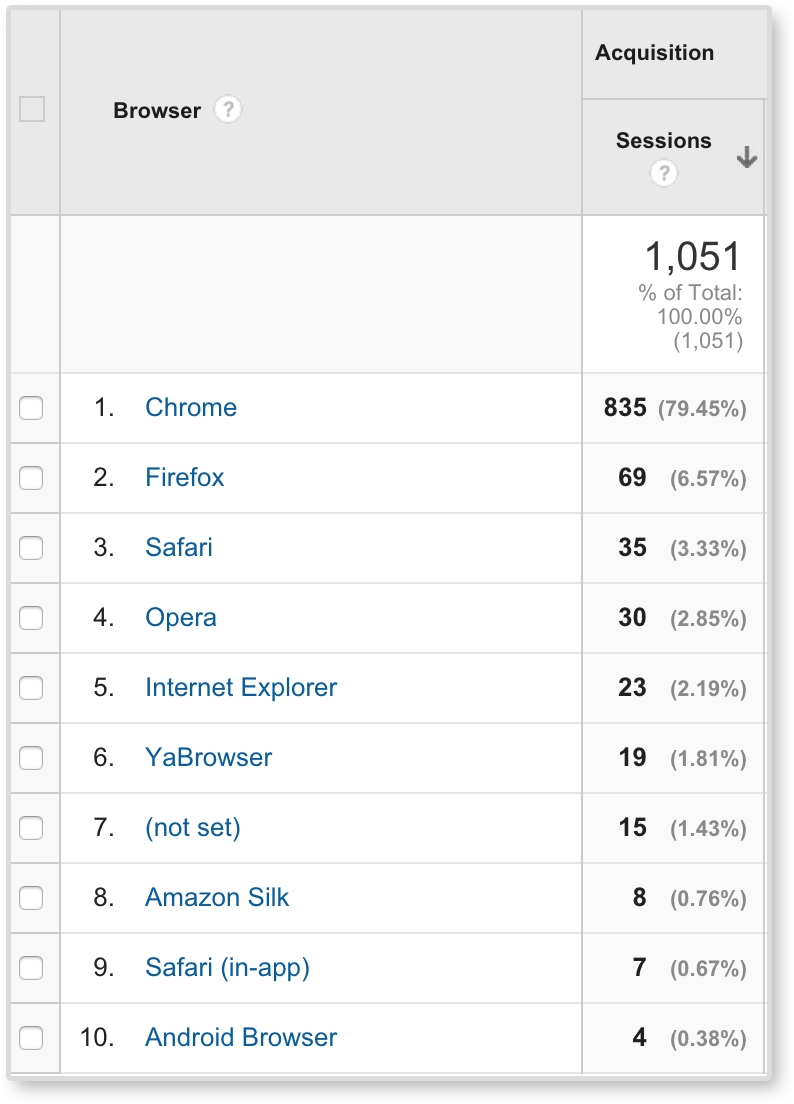

Our pattern examples will not be using the hamburger icon. Personally, I don't hate the hamburger icon. Are there better solutions though? Of course! If you asked a non-tech-savvy member of your family (looking at you, Grandma) what those three lines meant on a website, I would say there is less than a 50% chance that she would know what it is. The web publication, Exis (http://exisweb.net/), looked into the hamburger icon to see if users actually understood it. The director, James Foster, did a simple AB test measuring the engagement of two navigation icon variations. The first was the hamburger icon and the second just the word "Menu" with a border around it. After gathering data from over 240,000 Android visitors, Foster found that there was a 20% increase in engagement with the second variation. The engagement with the hamburger icon was still high enough though that Foster concluded it could be ubiquitous. So either way, the hamburger icon or just text, users were finding the navigation. Another solution is to use the hamburger icon, but keep the label "Menu" underneath it. This is kind of the best of both worlds, if you have the screen space for it.

To read more about this study, visit http://exisweb.net/menu-eats-hamburger.

Whether you use the hamburger icon in your projects or not, that is up to you. Some designers and developers argue that, since it is so widely used, people are learning what it means. And yes, Exis and Foster found that this might be true. But if there is another way that our users could understand better, why not explore it?

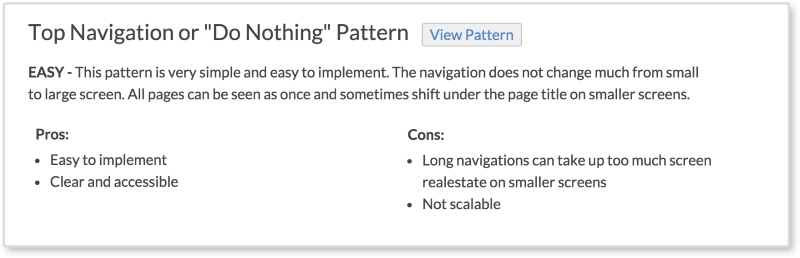

A website's navigation is the most important tool for the user. It should provide quick access to all that the website has to offer. It should also never get in the way. Next, we will review examples of popular responsive patterns that make navigating websites easy on both small and large screens. There is a large range of navigational patterns found on responsive websites today. In this chapter, we will look at the five most commonly found patterns and why they are so widely used.

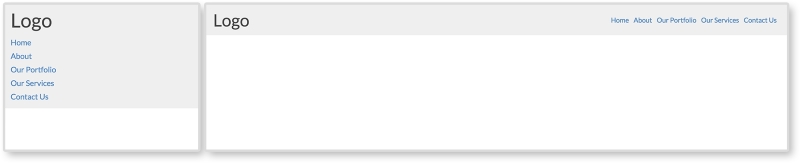

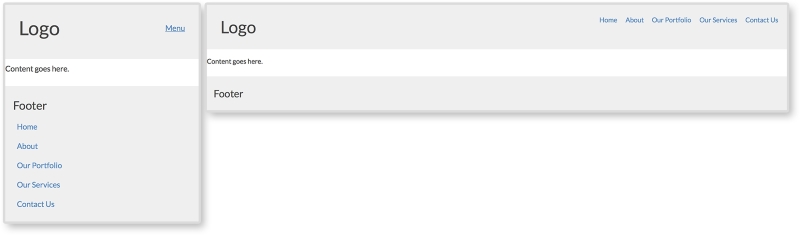

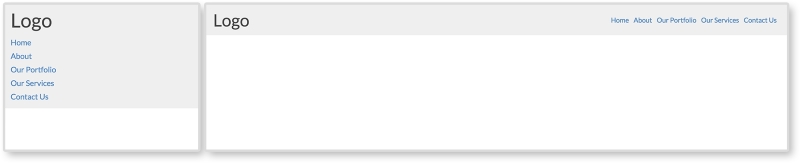

As mentioned, a common method for creating a responsive navigation is to let it simply stack up on smaller screens. This is why we'll call it the simple stack pattern. For small navigations, this pattern can do the trick. It is typically where newcomers to RWD start when building smaller websites. As seen here, the navigation floats to the right on large screens, but stacks on small ones.