Chapter 15. Working with data using GraphQL

This chapter covers

- Requesting data from the server with GraphQL and Axios

- Supplying data to a Redux store

- Implementing a GraphQL back end with Node/Express

- Supporting hash-less URL routing

In chapter 14, you implemented a Netflix clone with Redux. The data came from a JSON file, but you could instead have used a RESTful API call using axios or fetch(). This chapter covers one of the most popular options for providing data to a front-end app: GraphQL.

Thus far, you’ve been importing a JSON file as your back-end data store or making RESTful calls to fetch the same file to emulate a GET RESTful endpoint. Ah, mocking APIs. This approach is good for prototyping, because you have the front end ready; when you need persistent storage, you can replace mocks with a back-end server, which is typically a REST API (or, if you really have to, SOAP[1]).

Imagine that the Netflix clone API has to be developed by another team. You agree on the JSON (or XML) data format over the course of a few meetings. They deliver. The handshake is working, and your front-end app gets all the data. Then, the product owners talk to the clients and decide they want a new field to show stars and ratings for movies. What happens when you need an extra field? You must implement a new movies/:id/ratings endpoint, or the back-end team needs to bump up the version of the old endpoint and add an extra field.

Maybe the app is still in the prototyping phase. If so, the field could probably be added to the existing movies/:id. It’s easy to see that over time, you’ll get more requests to change formats and structure. What if ratings must appear in movies as well? Or, what if you need new nested fields from other collections, such as friend recommendations? In the age of rapid agile development and lean startup methodology, flexibility is an advantage. The faster these fields and data can be adapted to the end product, the better. An elegant solution called GraphQL clears many of these hurdles.

Note

The source code for the examples in this chapter is at www.manning.com/books/react-quickly and https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly/tree/master/ch15. You can also find some demos at http://reactquickly.co/demos.

15.1. GraphQL

In this chapter, you’ll continue developing the Netflix clone by adding a server to it. This server will provide a GraphQL API, a modern way of exposing data to React apps. GraphQL is often used with Relay; but as you’ll see in this example, you can use it with Redux or any other browser data library. You’ll use axios for the AJAX/XHR/HTTP requests.

When you work with GraphQL and Redux, the server (back end and web server) can be built using anything (Ruby, Python, Java, Go, Perl), not necessarily Node.js; but Node is what I recommend, and that’s what you’ll use in this section because it lets you use JavaScript across the entire development tech stack.

In a nutshell, GraphQL (https://github.com/graphql/graphql-js) uses query strings that are interpreted by a server (typically Node), which in turn returns data in a format specified by those queries. The queries are written in a JSON-like format:

{

user(id: 734903) {

id,

name,

isViewerFriend,

profilePicture(size: 50) {

uri,

width,

height

}

}

}

And the response is good-old JSON:

{

"user" : {

"id": 734903,

"name": "Michael Jackson",

"isViewerFriend": true,

"profilePicture": {

"uri": "https://twitter.com/mjackson",

"width": 50,

"height": 50

}

}

}

The Netflix clone server could use REST or older SOAP standards. But with the newer GraphQL pattern, you can reverse control by letting clients (front-end or mobile apps) dictate what data they need instead of coding this logic into server endpoints/routes. Some of the advantages of this inverted approach are as follows:[2]

For more on the advantages of GraphQL, such as strong typing, see Nick Schrock, “GraphQL Introduction,” React, May 1, 2015, http://mng.bz/DS65.

- Client-specific queries—Clients get exactly what they need.

- Structure, arbitrary code—The uniform API offers server-side flexibility.

- Strong typing—More robust validation and certainty in responses, plus easier data consumption by strongly typed languages such as TypeScript, Swift, Java, and Objective-C.

- Hierarchical queries—Queries follow the data they return, which is important because data is used by hierarchical views.

- Faster prototyping—There’s no need for extensive back-end development or large, separate back-end and API teams, because the query has a single endpoint.

- Fewer API calls—The front-end app makes fewer server requests because the data structure is dictated by the front-end app and can contain what was previously obtainable only via several REST endpoints.

You can also consume a GraphQL API in a React application using Relay (https://facebook.github.io/relay; graphql-relay-js and react-relay on npm). Some developers prefer to use Relay instead of Redux when working with a GraphQL back end. If you look at the examples provided in the documentation, you may see a similarity to how Redux connects components; and instead of a store, you have a remote GraphQL API.

Whereas React allows you to define views as components (UI) by composing many simple components to build complex UIs and apps, Relay lets components specify what data they need so the data requirements become localized. React components don’t care about the logic and rendering of other components.

The same is true with Relay: components keep their data closer to themselves, which allows for easier composition (building complex UIs and apps from simple components).

Relay Modern is the latest version of Relay. It’s easier to use and more extensible.[3] If you or your team plan to use GraphQL seriously, then I highly recommend looking into Relay/Relay Modern as well.

15.2. Adding a server to the Netflix clone

To deliver data to your React app, you’ll use a simple server made with Express (https://github.com/expressjs/express) and GraphQL. Express is great at organizing and exposing API endpoints, and GraphQL takes care of making your data accessible in a browser-friendly way, as JSON.

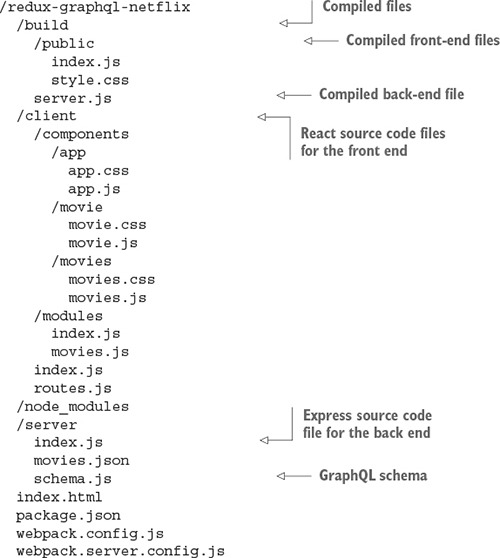

The project structure is as follows (you’ll reuse a lot of code from redux-netflix):

The data will still be taken from a JSON file, but this time it’s a server file. You can easily replace the JSON file movies.json with database calls in server/schema.js. But before we discuss schemas, let’s install all the dependencies, including Express.

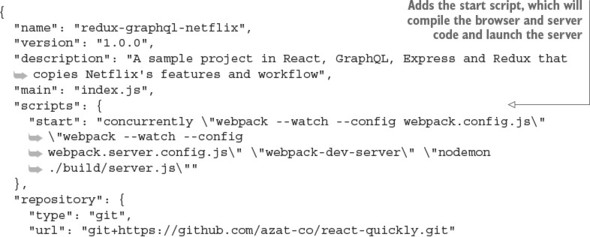

The following listing shows the package.json file (ch15/redux-graphql-netflix/package.json). Do you know what to do? Copy it and run npm i, of course!

Listing 15.1. Netflix clone package.json

Next, you’ll implement the main server file server/index.js.

15.2.1. Installing GraphQL on a server

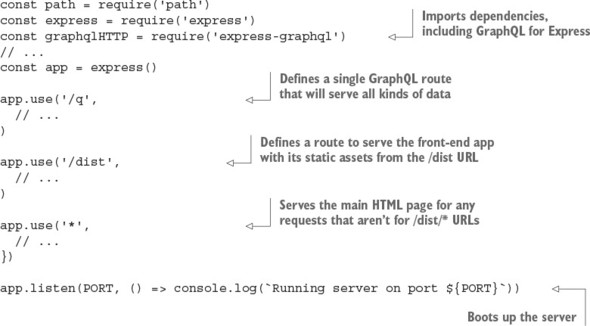

The powerhouse of the web server implemented with Express and Node is its starting point (sometime referred to as an entry point): index.js. This file is in the server folder because it’s used only on the back end and must not be exposed to clients, for security concerns (it can contain API keys and passwords). The file’s high-level structure is as follows:

Let’s fill in the missing pieces. First, keep in mind that you need to deliver the same file, index.html, for every route except the API endpoint and bundle files. This is necessary because when you use the HTML5 History API and go to a location using a hash-less URL like /movies/8, refreshing the page will make the browser query that exact location.

You’ve probably noticed that in the previous Netflix clone version, when you refreshed/reloaded the page on an individual movie (such as /movies/8), it didn’t show you anything. The reason is that you need to implement something additional for browser history to work. This code must be on the server, and it’s responsible for sending out the main index.html file on all requests (even /movies/8/).

In Express, when you need to declare a single operation for every route, you can use * (asterisk):

app.use('*', (req, res) => {

res.sendFile('index.html', {

root: PWD

})

})

Sending the HTML file per any location (* URL pattern) doesn’t do the trick. You’ll end up with 404 errors, because this HTML includes references to compiled CSS and JS files (/dist/styles.css and /dist/index.js). So, you need to catch those locations first:

app.use('/dist/:file', (req, res) => {

res.sendFile(req.params.file, {

root: path.resolve(PWD, 'build', 'public')

})

})

As an alternative, I recommend that you use using a piece of Express middleware called express.static(), like this:

app.use('/dist',

express.static(path.resolve(PWD, 'build', 'public'))

)

Tip

For more information about middleware and tips on Express, refer to appendix c and my books Pro Express.js (Apress, 2014) and Express Deep API Reference (Apress, 2014).

The importance of having the public folder inside build cannot be overstated. If you don’t restrict the act of serving resources (such as files) to a subfolder (such as dist or public), then all of your code will be exposed to anyone who visits the server. Even back-end code such as server.js can be exposed if you forego using a subfolder. For example, this

// Anti-pattern. Don't do this or you'll be fired

app.use('/dist',

express.static(path.resolve(PWD, 'build'))

)

will expose server.js to attackers—and it might contain secrets, API keys, passwords, and the details of implementation over the /dist/server.js URL.

By using a subfolder such as dist or public, exposing only it to the world (over HTTP), and putting only the front-end files in this exposed subfolder, you can restrict unauthorized access to other files.

For the GraphQL API to work, you need to set up one more route (/q) in which you use the graphqlHTTP library along with a schema (server/schema.js) and session (req.session) to respond with data:

app.use('/q', graphqlHTTP(req => ({

schema,

context: req.session

})))

And finally, to make the server work, you need to make it listen to incoming requests on a certain port:

app.listen(PORT, () => console.log(`Running server on port ${PORT}`))

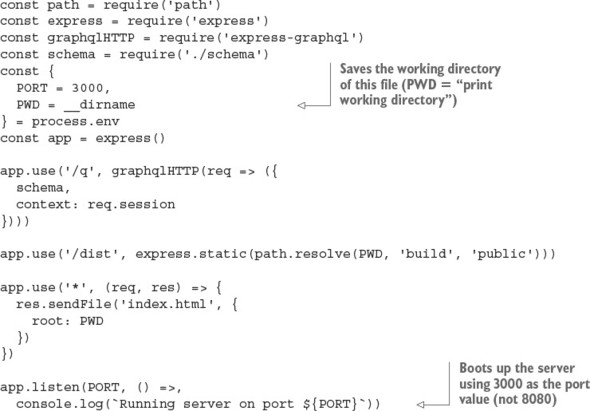

Here, PORT is an environment variable. It’s a variable that you can pass into the process from the command-line interface, like this:

PORT=3000 node ./build/server.js

Recall that in package.json, you use nodemon:

nodemon ./build/server.js

Using nodemon is the same as running node, but nodemon will restart the code if you made changes to it.

Warning

In chapter 14, you used port 8080, because that’s the default value for the Webpack Development Server. There’s nothing wrong with using 8080 for this example’s Express server, but for some weird historical reason, the convention emerged that Express apps run on port 3000. Maybe we can blame Rails for that!

The server also uses another variable declared in uppercase: PWD. It’s an environment variable, too, but it’s set by Node to the project directory: that is, the path to the folder where the package.json file is located, which is the root folder of your project.

And finally, you use the graphqlHTTP and schema variables. You receive graphqlHTTP from the express-graphql package, and schema is your data schema built using GraphQL definitions.

The following listing shows the complete server setup (ch15/redux-graphql-netflix/server/index.js).

Listing 15.2. Express server to provide data and static assets

GraphQL is strongly typed, meaning it uses schemas as you saw in /q. The schema is defined in server/schema.js, as you saw in the project structure. Let’s see what the data looks like: the structure of the data will determine the schema you’ll use.

15.2.2. Data structure

The app is a UI that displays data about movies. Therefore, you need to have this data somewhere. The easiest option is to save it in a JSON file (server/movies.json). The file contains all the movies, and each movie can be represented by a plain object with a bunch of properties, so the entire file is an array of objects:

[{

"title": "Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides"

...

}, {

"title": "Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End"

...

}, {

"title": "Avengers: Age of Ultron"

...

}, {

"title": "John Carter"

...

}, {

"title": "Tangled"

...

}, {

"title": "Spider-Man 3"

...

}, {

"title": "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince"

...

}, {

"title": "Spectre"

...

}, {

"title": "Avatar"

...

}, {

"title": "The Dark Knight Rises"

...

}]

Note

The example uses data for 10 of the most expensive movies according to Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_most_expensive_films).

Each object contains information such as the movie’s title, cover URL, year released, production cost in millions of dollars, and starring actors. For example, Pirates of the Caribbean has this data:

{

"title": "Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides",

"cover": "/dist/images/On_Stranger_Tides_Poster.jpg",

"year": "2011",

"cost": 378.5,

"starring": [{

"name": "Johnny Depp"

}, {

"name": "Penélope Cruz"

}, {

"name": "Ian McShane"

}, {

"name": "Kevin R. McNally"

}, {

"name": "Geoffrey Rush"

}]

}

Currently, each movie is an object that only has a title. Later, you can add as many properties as you want; but right now let’s focus on the data schema.

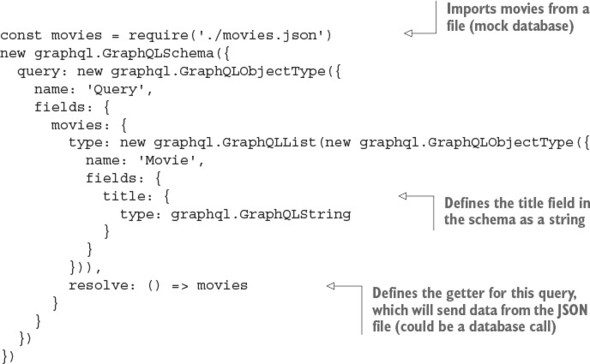

15.2.3. GraphQL schema

You can use any data source with GraphQL: an SQL database, an object store, a bunch of files, or a remote API. Two things matter:

- Purity of the data—that is, identical requests should return identical responses (a.k.a. idempotent).

- It should be possible to represent the data with JSON.

You have the list of movies stored in a JSON file, so you can import it:

const movies = require('./movies.json')

A typical GraphQL schema defines a query with fields and arguments. The example data schema has only a list of objects, and each object has only a single property: title. The schema definition is shown next. This is a basic example—you’ll see the full schema later:

The core idea is that when the query is performed, the function assigned to the resolve key is executed. After that, only properties of objects that are requested are picked from the result of this function call. These properties will be in the resulting objects, and fields that aren’t listed won’t appear. Thus you need to specify what properties you want to receive every time you perform a query. This makes your API flexible and efficient: you can arrange parts of the data as you want them in the runtime.

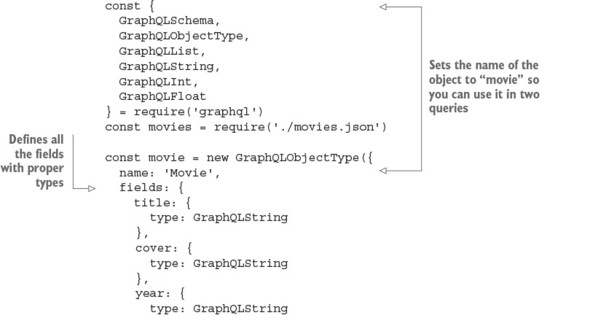

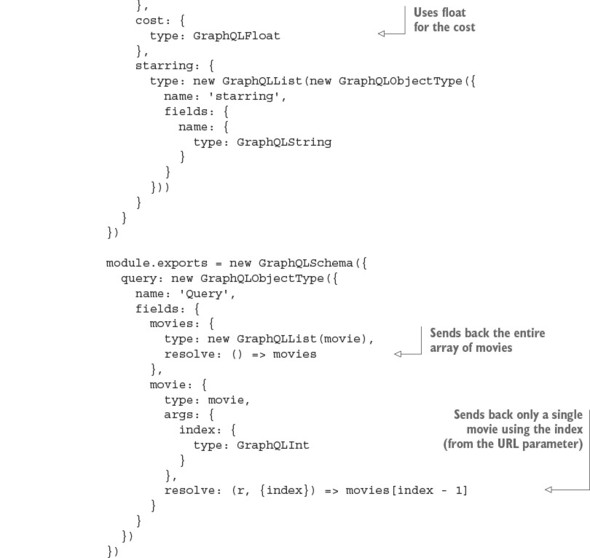

The example has two types of queries and more fields. The following listing shows how you can implement them (ch15/redux-graphql-netflix/server/schema.js).

Listing 15.3. GraphQL schema

Phew! Now let’s move to the front end and see how to query this neat little server.

15.2.4. Querying the API and saving the response into the store

To get the list of movies, you need to query the server. And after the response has been received, you must pass it to the store. This operation is asynchronous and involves an HTTP request, so it’s time to unveil axios.

The axios library implements promise-based HTTP requests. This means it returns a promise immediately after calling a function. Because an HTTP request isn’t guaranteed to be performed immediately, you need to wait until this promise is resolved.

To get data from a promise once it’s resolved, you use its then property. It accepts a function as a callback, which is called with a single argument; and this argument is the result of the initial operation—in this case, an HTTP call:

getPromise(options)

.then((data)=>{

console.log(data)

})

Using a promise and a callback (in then) is an alternative to using just a callback, in the sense that the previous code can be rewritten without promises:

getResource(options, (data)=>{

console.log(data)

})

There’s a controversy associated with promises. Although some people prefer promises and callbacks over plain callbacks due to the convenience of the promise catch.all syntax, others feel promises aren’t worth the hassle (I’m in this camp), especially considering that promises can bury errors and fail silently. Nevertheless, promises are part of ES6/ES2015 and are here to stay. At the same time, new patterns such as generators and async/await are emerging as part of the next evolution of writing async code.[4]

See my courses on ES6 and ES7+ES8 at https://node.university/p/es6 and https://node.university/p/es7-es8.

Rest assured, you can do any asynchronous coding with plain callbacks. But most modern (especially front-end) code uses (or will use) promises or async/await. For this reason, this book uses promises with fetch() and axios.

For more information on the promise API, refer to the documentation at MDN (http://mng.bz/7DcO) and my article “Top 10 ES6 Features Every Busy JavaScript Developer Must Know” (https://webapplog.com/es6).

axios uses promise-based requests, not unlike fetch(). To perform a GET HTTP call, use the get property of axios:

axios.get('/q')

Because axios returns a promise, you can immediately access its then property:

axios.get('/q').then(response => response)

The function you pass as the argument to then returns into the context of the promise and not the context of your component’s method. You need to call an action creator to deliver new data into the store:

axios.get('/q').then(response => this.props.fetchMovie(response))

Now, let’s build a proper query against your GraphQL API. To do that, you can use a multiline template string (notice that it uses backticks instead of single quotes):

axios.get(`/q?query={

movie(index:1) {

title,

cover

}

}`).then(response => this.props.fetchMovie(response))

Using a multiline template literal (the backticks) preserves line breaks, so the query string will have new lines. Not good. New lines in a query string might break the API endpoint URLs. For this reason, you need to remove unnecessary spaces and line breaks in the HTTP calls but keep them in the source code. The clean-tagged-string library (https://github.com/taxigy/clean-tagged-string) does only that: it transforms a huge, multiline template string into a smaller, single-line string resulting in this

clean`/q?query={

movie(index:1) {

title,

cover

}

}`

looking like this:

'/q?query={ movie(index:1) { title, cover } }'

Notice the syntax: there are no parentheses (round brackets) after clean, and it’s attached to the template string. This is valid syntax and is called using tagged strings (http://mng.bz/9CqH).

Now, let’s get the first movie, with an index of 1:

const clean = require('clean-tagged-string').default

axios.get(clean`/q?query={

movie(index:1) {

title,

cover

}

}`).then(response => this.props.fetchMovie(response))

Figure 15.1. Single-movie view server from Express server (port 3000) with browser history (no hash signs!)

Next, you need to implement code to get any movie based on its ID. You also want to request more fields, not just title and cover, so you can display the view shown in figure 15.1. It’s good to know that the single-movie page won’t be lost on reload, because you added the special server code to sendFile() for * to catch all routes that send index.html.

You can fetch the data for a single movie from the API in the lifecycle component using your favorite promise-based HTTP agent, axios:

componentWillMount() {

const query = clean`{

movie(index:${id}) {

title,

cover,

year,

starring {

name

}

}

}`

axios.get(`/q?query=${query}`)

.then(response =>

this.props.fetchMovie(response)

)

}

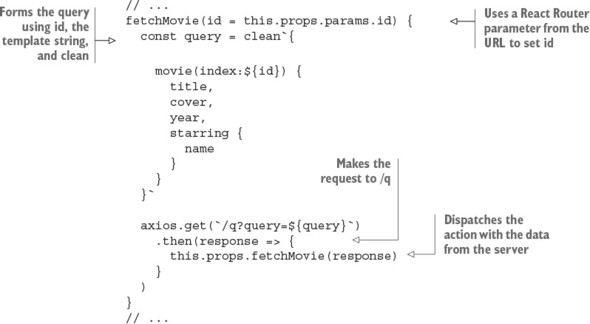

The list of requested properties for a movie entity is a little longer: not just title and cover, but also year and starring. Because starring is itself an array of objects, you also need to declare which properties of those objects you want to request. In this case, you only want name.

The response from the API goes to the fetchMovie action creator. After that, the store is updated with the movie the user wants to see.

Connect it:

const {

fetchMovieActionCreator

} = require('modules/movies.js')

...

module.exports = connect(({movies}) => ({

movie: movies.current

}), {

fetchMovie: fetchMovieActionCreator

})(Movie)

And render it:

render() {

const {

movie = {

starring: []

}

} = this.props;

return (

<div>

<img src={`url(${movie.cover})`} alt={movie.title} />

<div>

<div>{movie.title}</div>

<div>{movie.year}</div>

{movie.starring.map((actor = {}, index) => (

<div key={index}>

{actor.name}

</div>

))}

</div>

<Link to="/movies">

←

</Link>

</div>

)

}

To better organize the code, let’s add a fetchMovie() method to the Movie component that’s already familiar to you from chapter 14 (ch14/redux-netflix/src/components/movie/movie.js). This new method will be used to make AJAX-y calls that will, in turn, dispatch actions. The method is in the Movie component (ch15/redux-graphql-netflix/client/components/movie/movie.js).

Listing 15.4. fetchMovie() component class method

Next, let’s move on to getting the list of movies.

15.2.5. Showing the list of movies

When you show a list of movies, the query to the API is different, and it’s rendered in a different way than when you fetch a single movie. You fetched the data from the GraphQL server using a valid GraphQL query, via an asynchronous GET request performed with the axios library, and you put this data into the store via an action. The next thing to do is show this data to the user: time to render it.

You already know that, to take data from the store, a component needs to be connected: wrapped with a connect() function call that maps state and actions to properties. In the component’s render() function, you use component properties. But these properties need values; that’s why you make AJAX/XHR calls, usually after the component has been mounted for the first time (lifecycle events!).

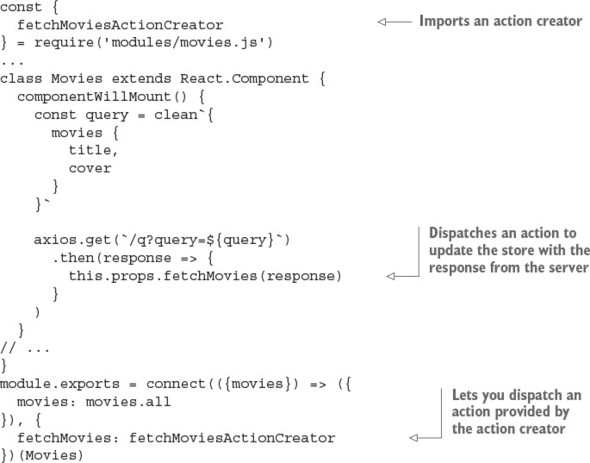

Let’s declare a component to pick the data from the store, take it from properties, and render it. First, connect the component to the store (this snippet is from ch15/redux-graphql-netflix/client/components/movies/movies.js):

const React = require('react')

const { connect } = require('react-redux')

const {

fetchMoviesActionCreator

} = require('modules/movies')

class Movies extends Component {

// ...

}

module.exports = connect(({movies}) => ({

movies: movies.all

}), {

fetchMovies: fetchMoviesActionCreator

})(Movies)

The connect() function takes two arguments: the first maps the store to component properties, and the second maps action creators to component properties. After that, the component has two new properties: this.props.movies and this.props.fetchMovies().

Next, let’s fetch those movies and, as the data is received, place it in the store via the action creator (dispatch an action). Usually, data may be requested from a remote API when the component starts its lifecycle (componentWillMount() or componentDidMount()):

Finally, render the Movies component using data from properties, which comes from the Redux store:

// ...

render() {

const {

movies = []

} = this.props

return (

<div>

{movies.map((movie, index) => (

<Link

key={index}

to={`/movies/${index + 1}`}>

<img src={`url(${movie.cover})`} alt={movie.title} />

</Link>

))}

</div>

)

}

// ...

Every movie has cover and title properties. A link to a movie is basically a reference to its position in the array of movies. This setup isn’t stable when you have thousands of elements in a collection, because, well, the order is never guaranteed, but for now it’s okay. (A better way would be to use a unique ID, which is typically autogenerated by a database like MongoDB.)

The component now renders the list of movies, although it lacks styles. Check out this chapter’s source code to see how it works with styles and a three-level hierarchy of components.

15.2.6. GraphQL wrap-up

Adding GraphQL support on a basic level is straightforward and transparent. GraphQL works differently than a typical RESTful API: you can query any property, at any nesting level, for any subset of entities the API provides. This makes GraphQL efficient for datasets of complex objects, whereas a REST design usually requires multiple requests to get the same data.

GraphQL is a promising pattern for implementing server-client handshakes. It allows for more control from the client, which can dictate the structure of the data to the REST API. This inversion of control allows front-end developers to request only the data they need and not have to modify back-end code (or ask a back-end team to do so).

15.3. Quiz

Which command creates a GraphQL schema? new graphql.GraphQLSchema(), graphql.GraphQLSchema(), or graphql.getGraphQLSchema()

It’s okay to put API calls into reducers. True or false? (Hint: See a Tip in chapter 14.)

Where do you make the GraphQL call to fetch a movie? componentDidUnmount(), componentWillMount(), or componentDidMount()

You used this URL for GraphQL: `/q?query=${query}`. What does this syntax refer to? Inline Markdown, comments, template literal, string template, or string interpolation

GraphQLString is a special GraphQL schema type, and you can pull this class from the graphql package. True or false?

15.4. Summary

- GraphQL is a robust, reliable way to provide data to the front end. It also eliminates a lot of duplicate back-end code.

- To enable the browser history and hash-less URL with React Router, you can use sendFile() in the * Express route to serve index.html.

- To use Express not just as a data provider/API but as a static web server, use express.static with app.use().

- GraphQL’s URL structure is /q?query=... where query has the value of your data query.

15.5. Quiz answers

new graphql.GraphQLSchema()

False. Avoid putting API calls in reducers. It’s better to put them in components (container/smart components, to be specific).

componentWillMount(), but componentDidMount() is also a good location. componentDidUnmount() isn’t a valid method.

Template literal, string template, and string interpolation are all valid names to define the query with a variable.

True. This is valid code: const {GraphQLString} = require('graphql'). See listing 15.3.