For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: orders@manning.com

©2017 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed

on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources

of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental

chlorine.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed

on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources

of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental

chlorine.

|

Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 |

Development editor: Dan Maharry Technical development editor: Anto Aravinth Review editor: Ivan Martinović Project editor: Tiffany Taylor Copyeditor: Tiffany Taylor Proofreader: Katie Tennant Technical proofreader: German Frigerio Typesetter: Gordan Salinovic Cover designer: Leslie Haimes

ISBN 9781617293344

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 – EBM – 22 21 20 19 18 17

To my grandfather, Khalit Khamitov. Thank you for being such a kind and just person. You will always stay in my memory, along with the crafts you taught me, the trips we took to the dacha, and the chess games we played.

Chapter 2. Baby steps with React

Chapter 3. Introduction to JSX

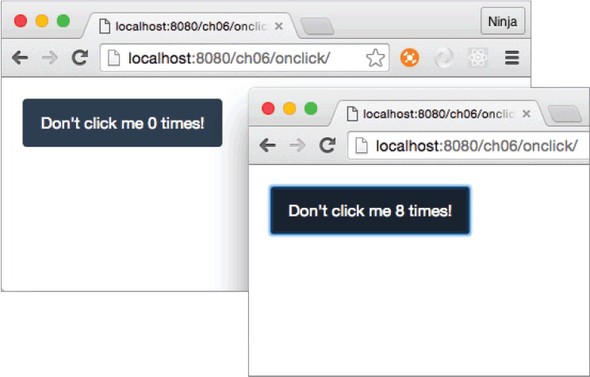

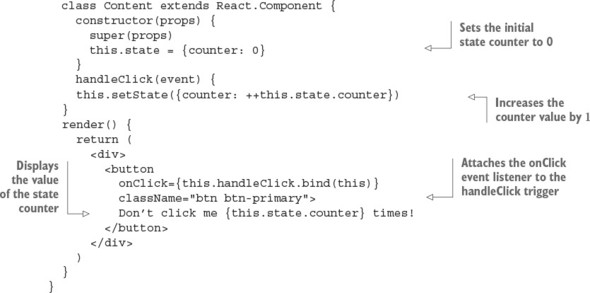

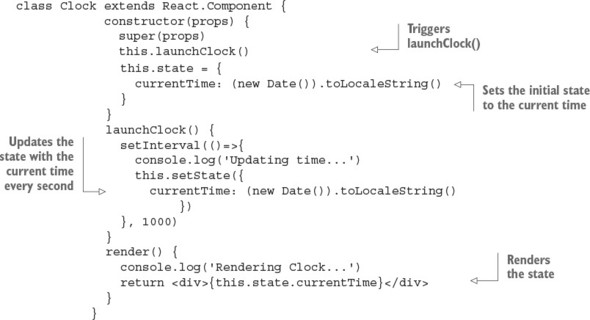

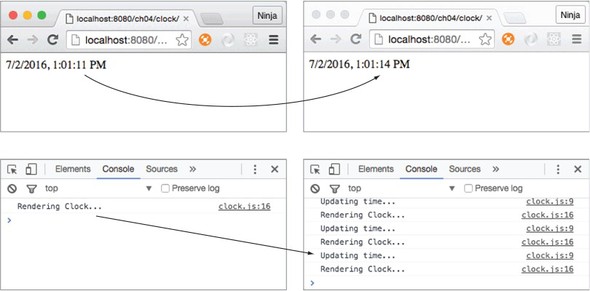

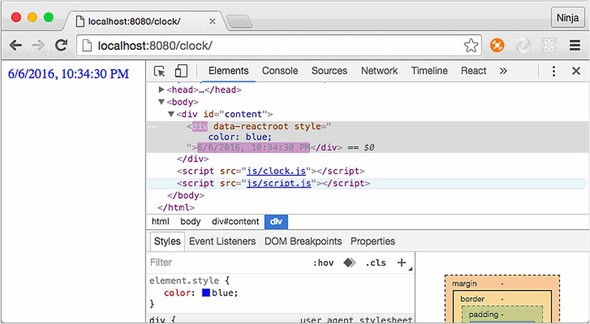

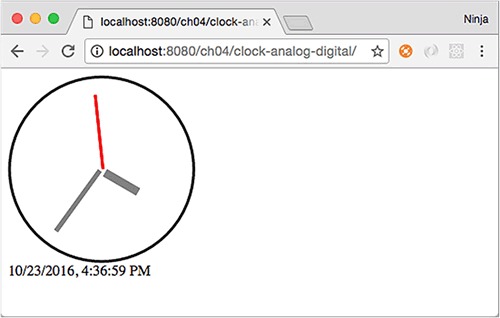

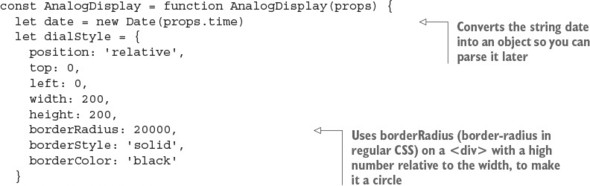

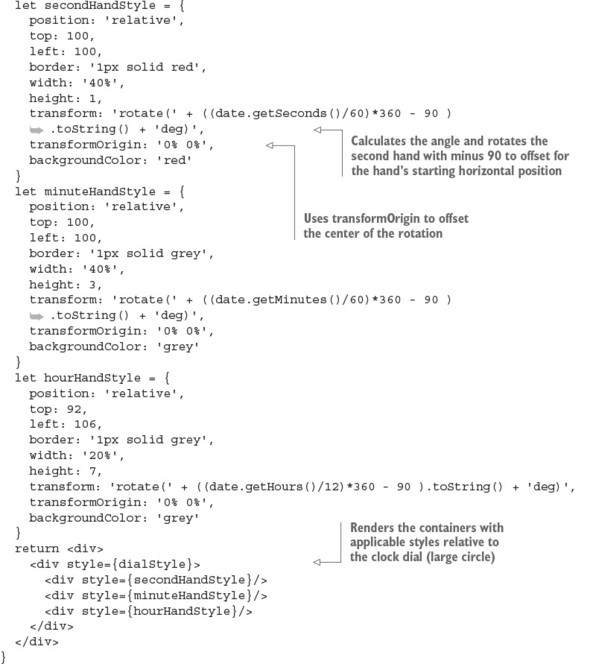

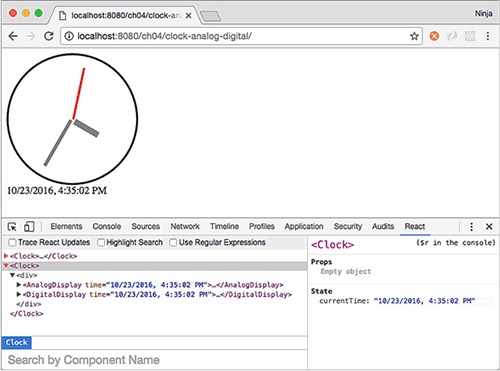

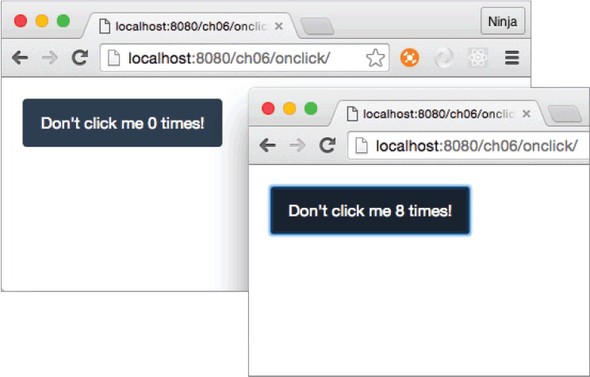

Chapter 4. Making React interactive with states

Chapter 5. React component lifecycle events

Chapter 6. Handling events in React

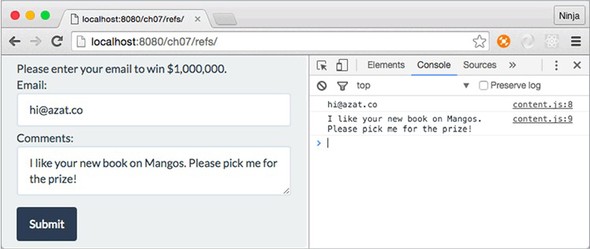

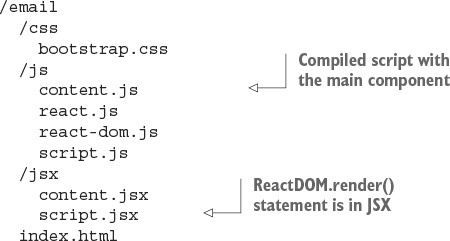

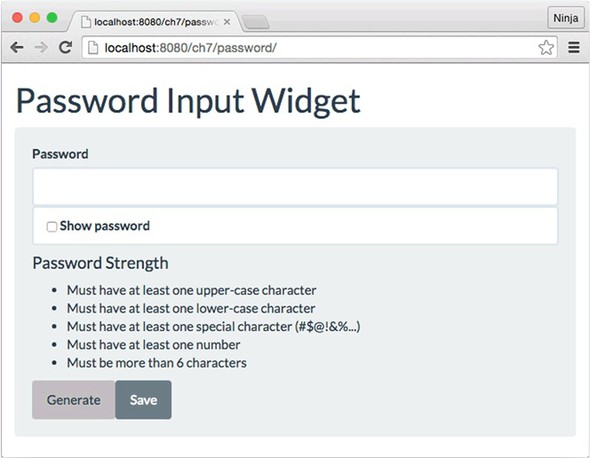

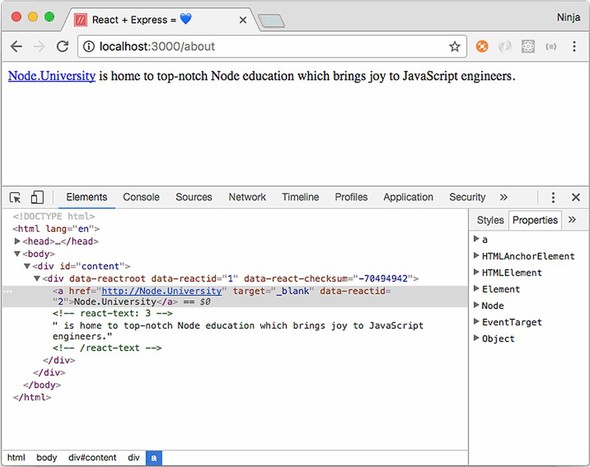

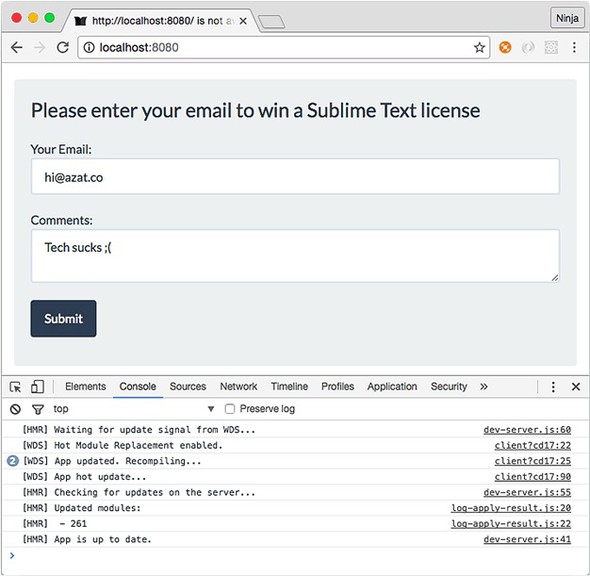

Chapter 7. Working with forms in React

Chapter 8. Scaling React components

Chapter 9. Project: Menu component

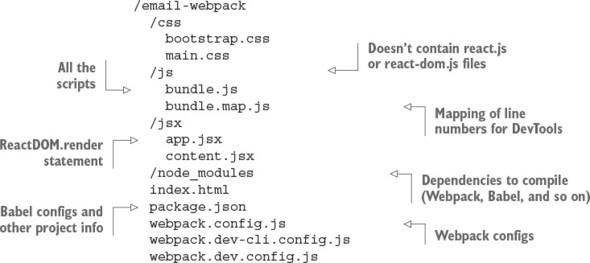

Chapter 12. The Webpack build tool

Chapter 14. Working with data using Redux

Chapter 15. Working with data using GraphQL

Chapter 16. Unit testing React with Jest

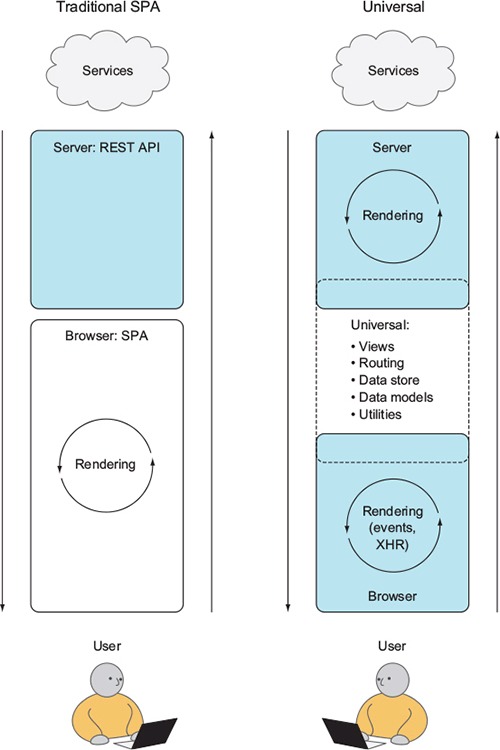

Chapter 17. React on Node and Universal JavaScript

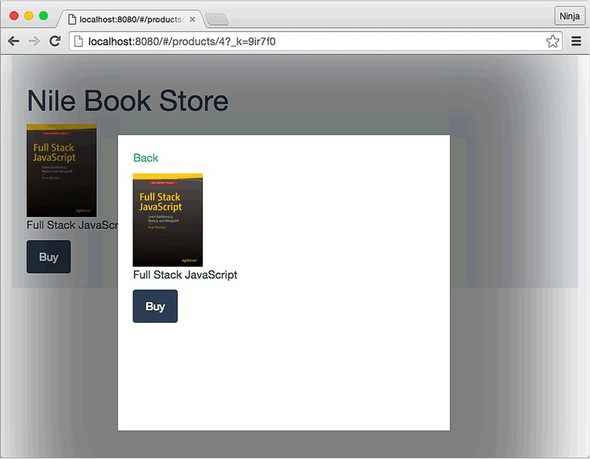

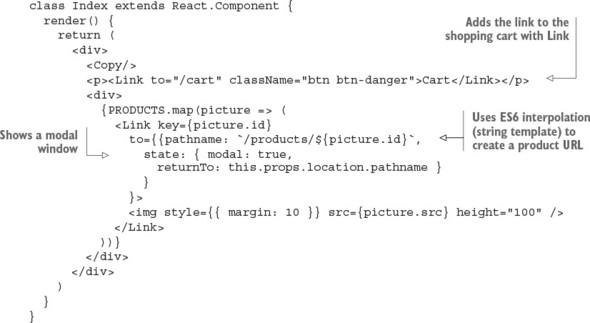

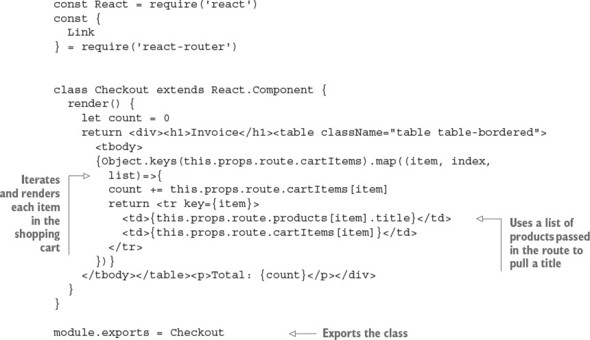

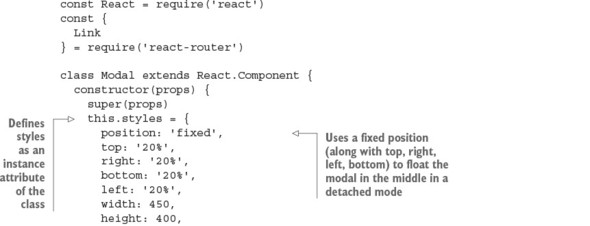

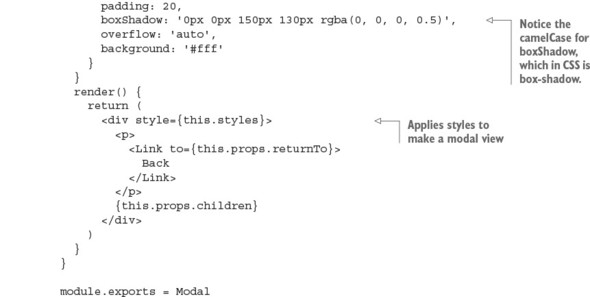

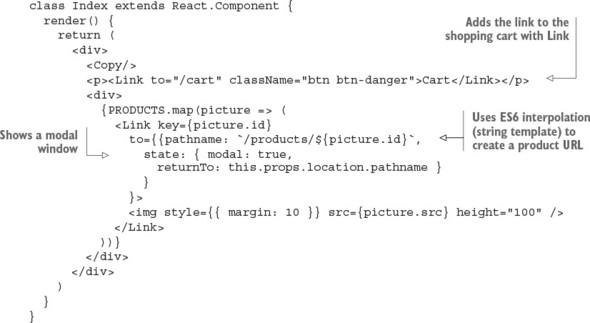

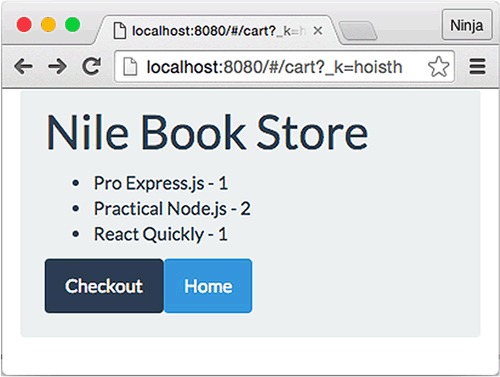

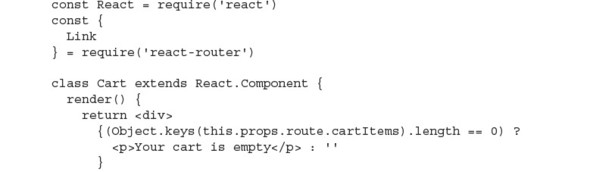

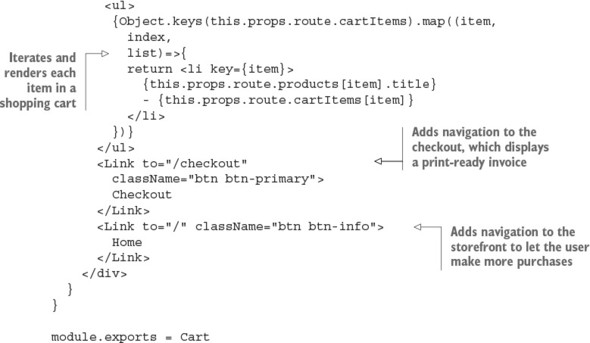

Chapter 18. Project: Building a bookstore with React Router

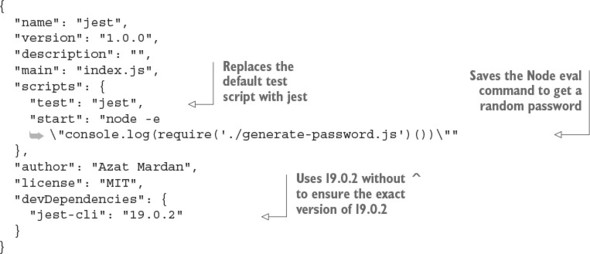

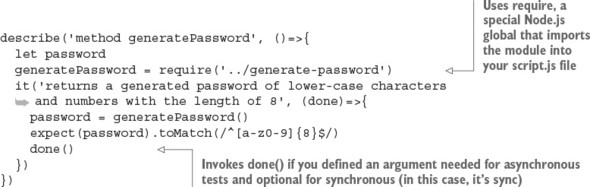

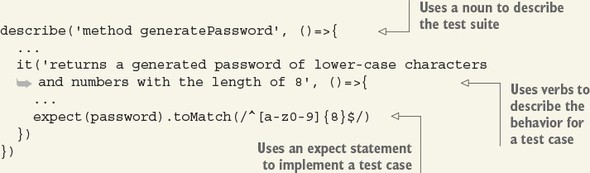

Chapter 19. Project: Checking passwords with Jest

Chapter 20. Project: Implementing autocomplete with Jest, Express, and MongoDB

Appendix A. Installing applications used in this book

Appendix C. Express.js cheatsheet

1.2. The problem that React solves

1.5. How React can fit into your web applications

1.5.1. React libraries and rendering targets

Chapter 2. Baby steps with React

Chapter 3. Introduction to JSX

3.1. What is JSX, and what are its benefits?

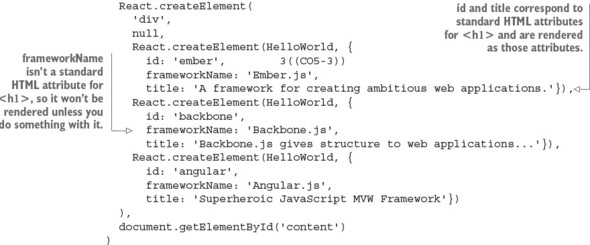

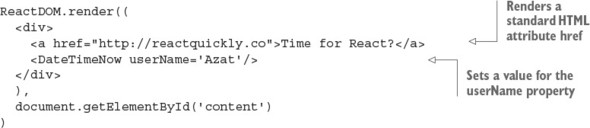

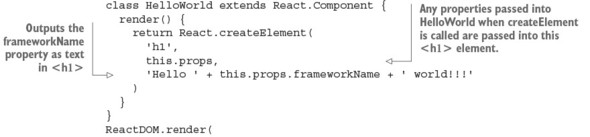

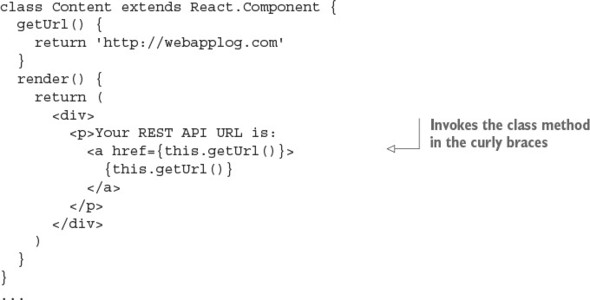

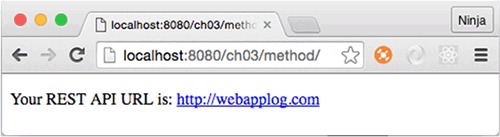

3.2.1. Creating elements with JSX

3.2.2. Working with JSX in components

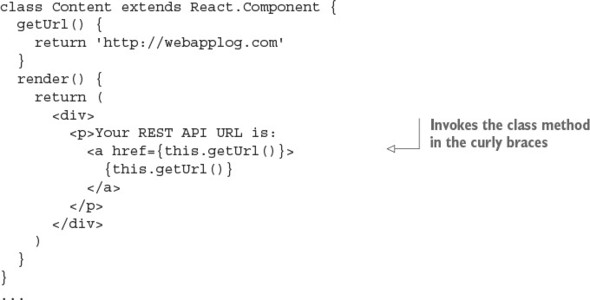

3.2.3. Outputting variables in JSX

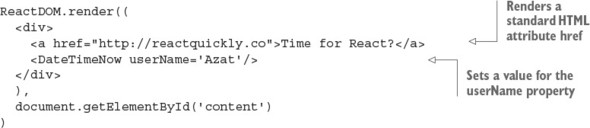

3.2.4. Working with properties in JSX

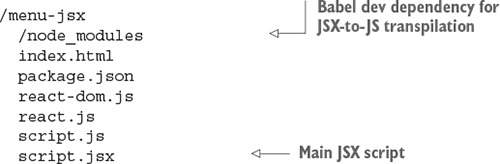

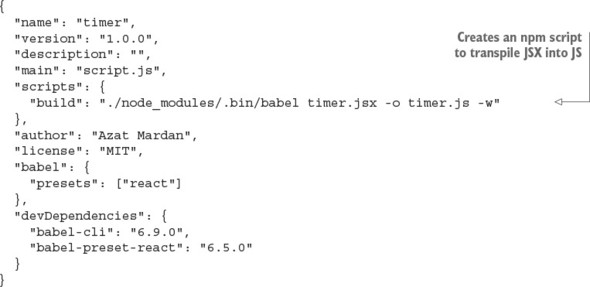

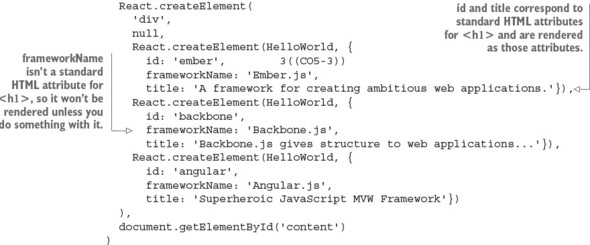

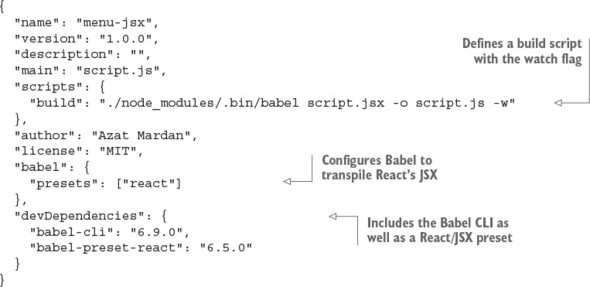

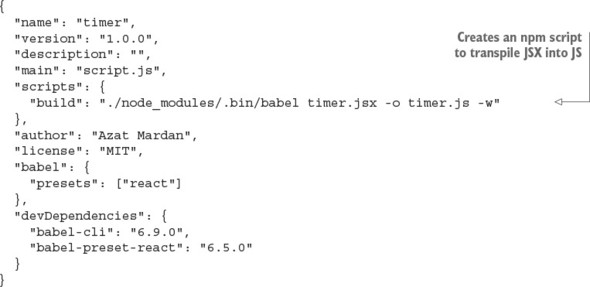

3.3. Setting up a JSX transpiler with Babel

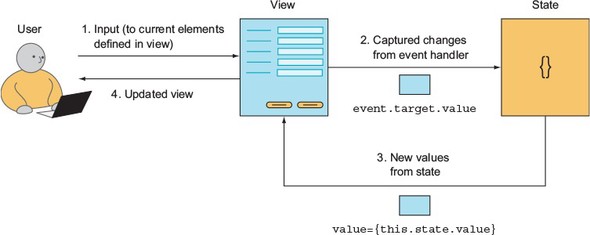

Chapter 4. Making React interactive with states

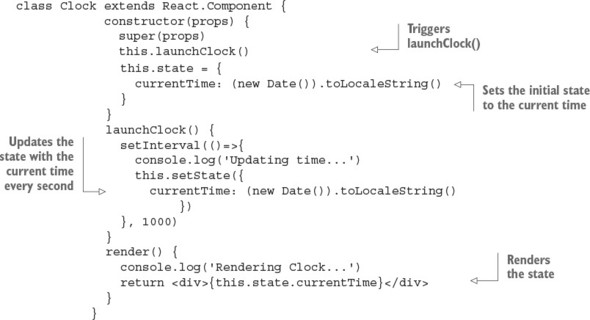

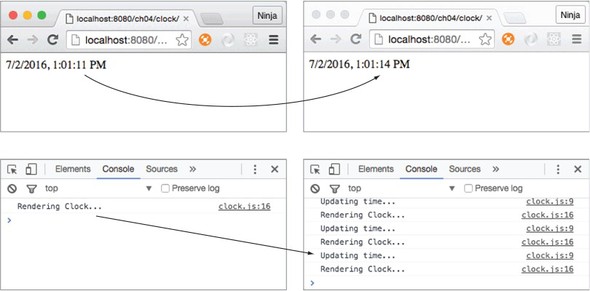

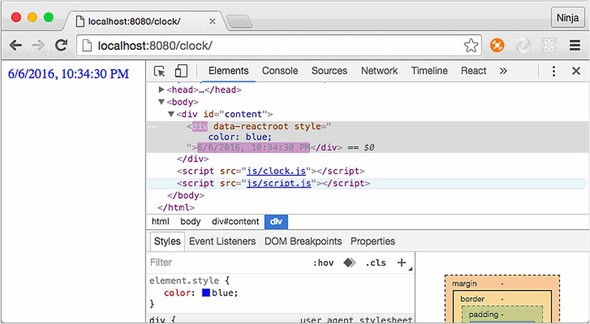

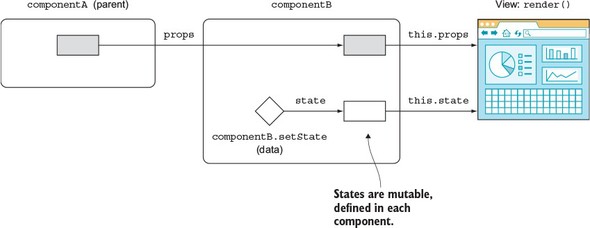

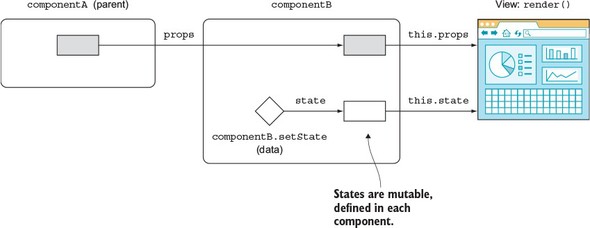

4.1. What are React component states?

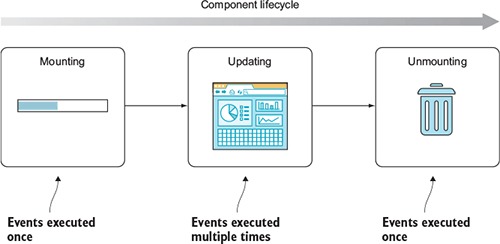

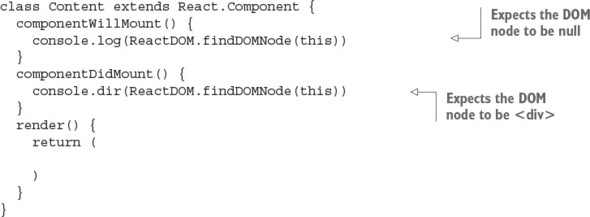

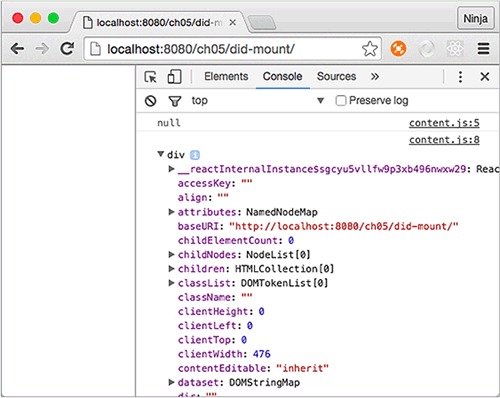

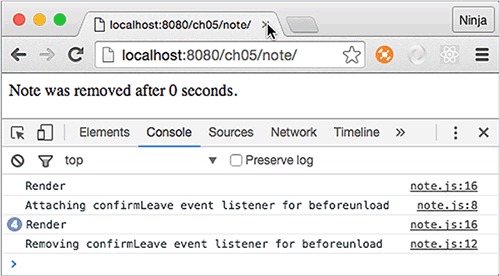

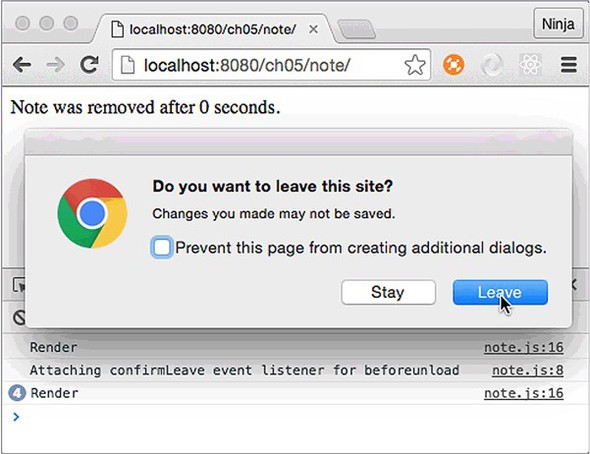

Chapter 5. React component lifecycle events

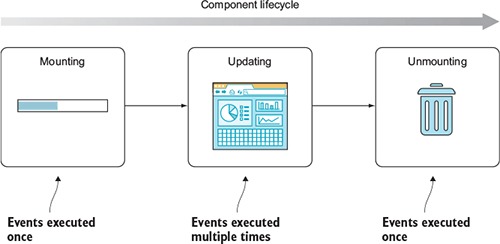

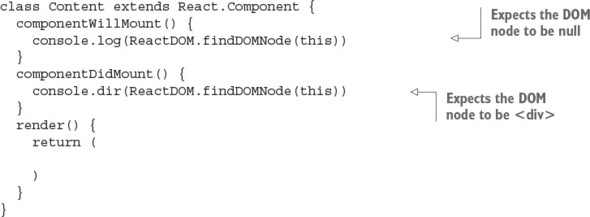

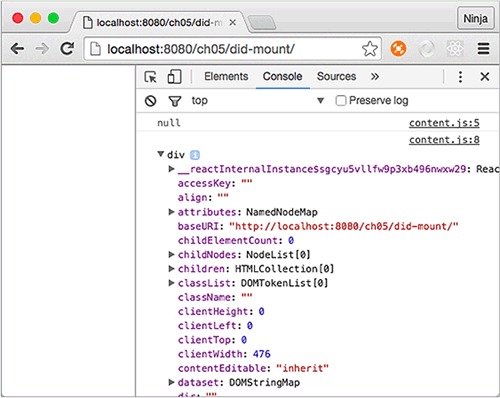

5.1. A bird’s-eye view of React component lifecycle events

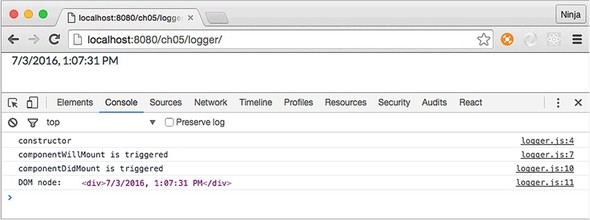

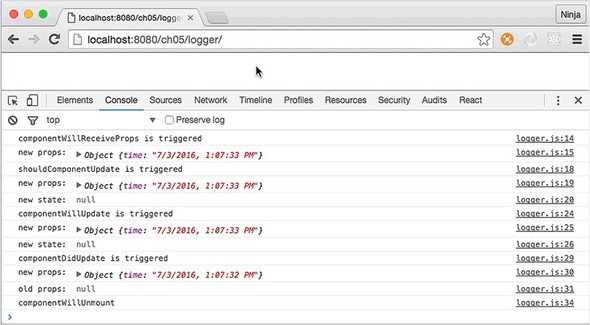

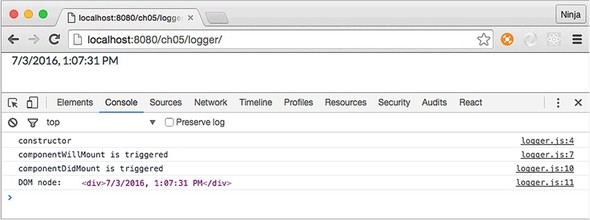

5.4. Executing all events together

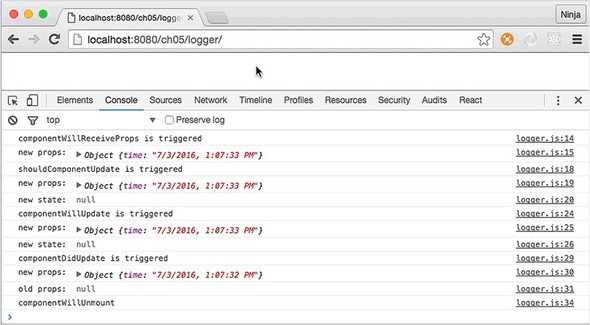

5.6.1. componentWillReceiveProps(newProps)

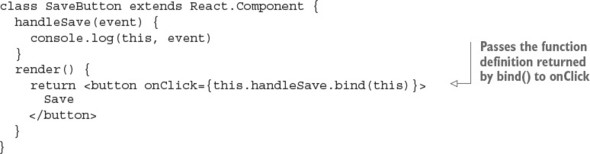

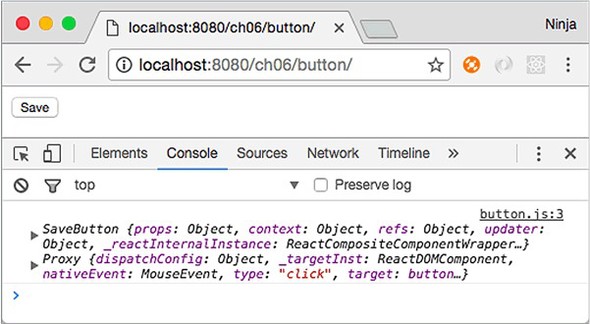

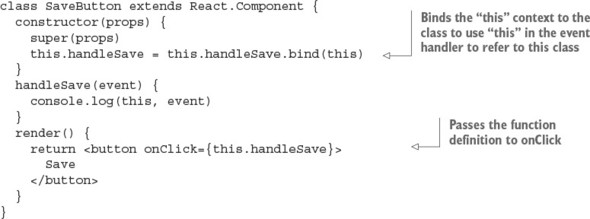

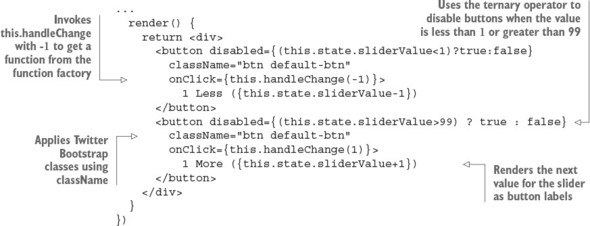

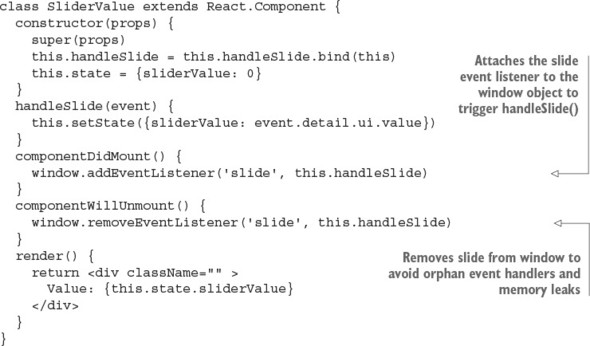

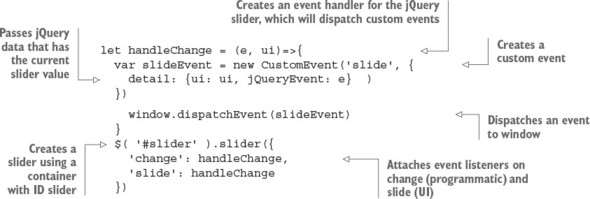

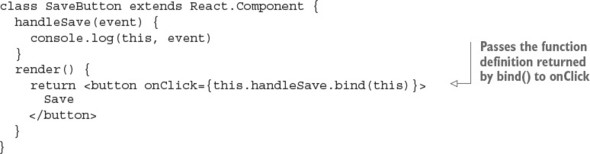

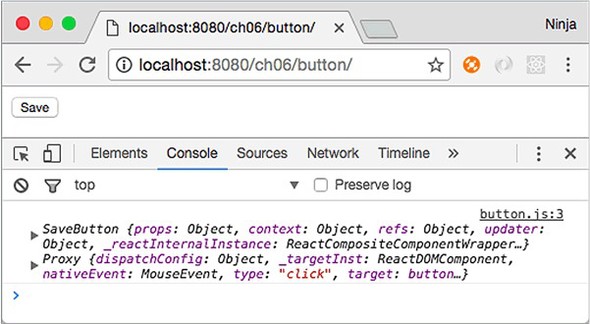

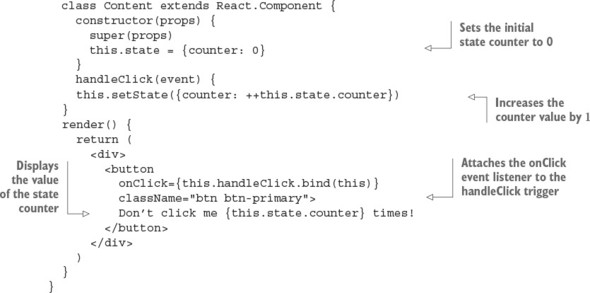

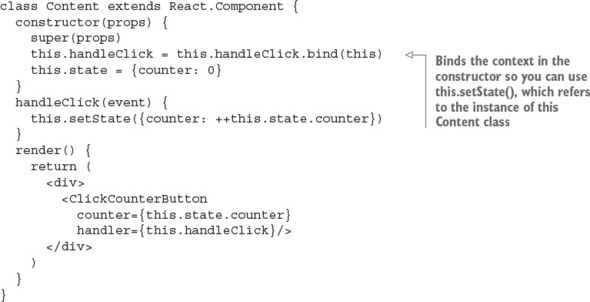

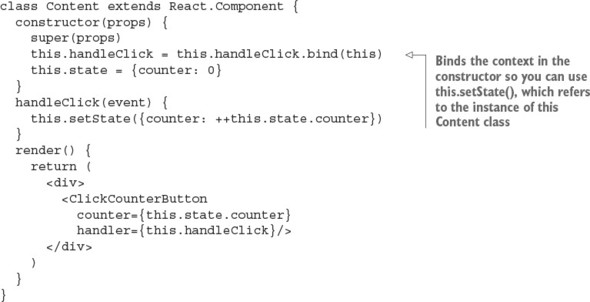

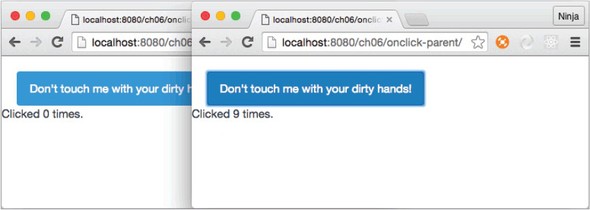

Chapter 6. Handling events in React

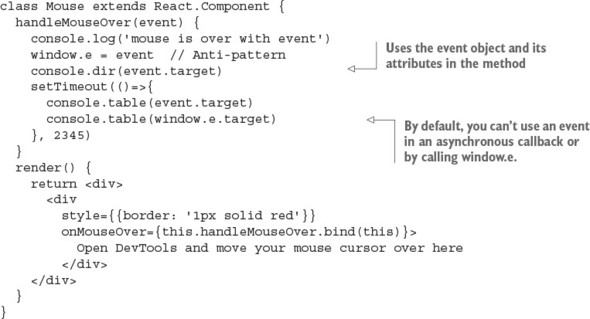

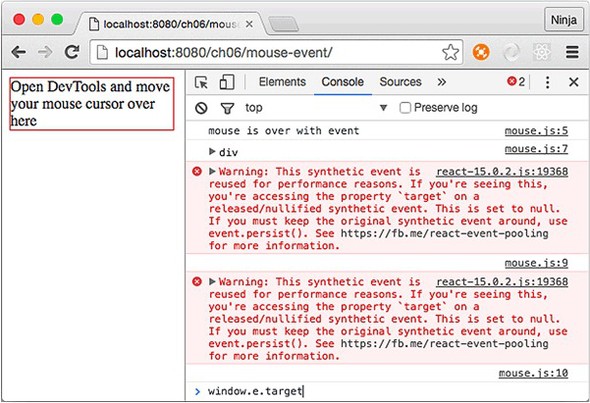

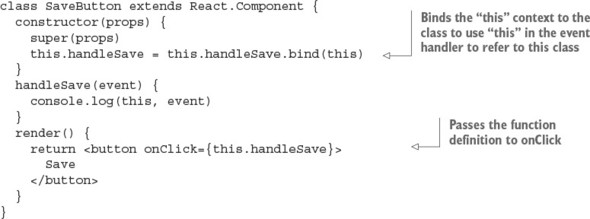

6.1. Working with DOM events in React

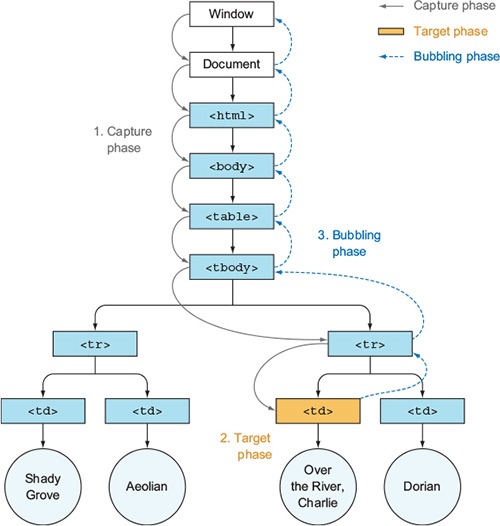

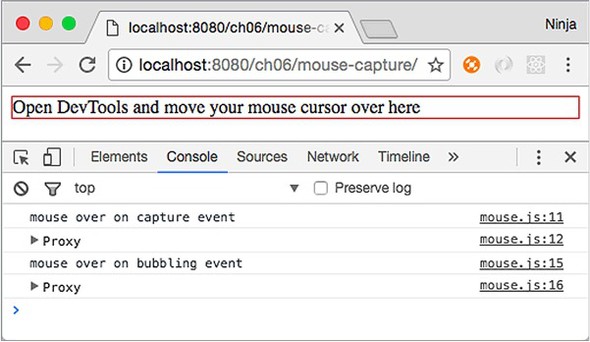

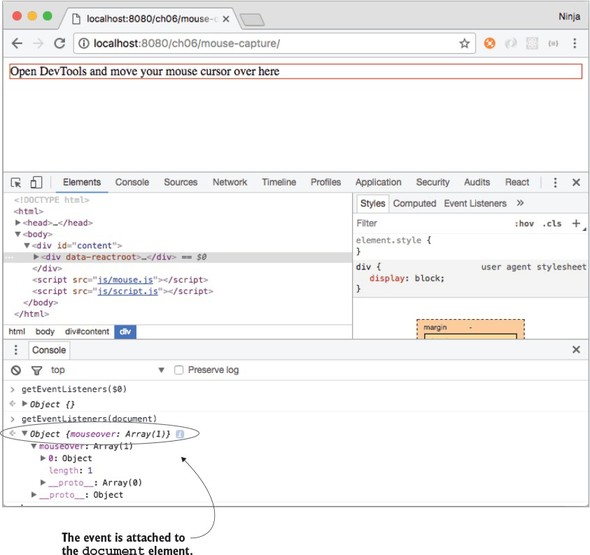

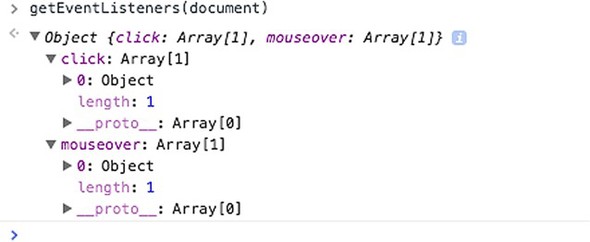

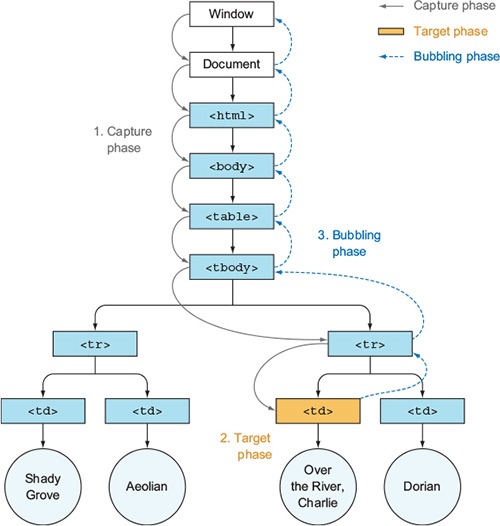

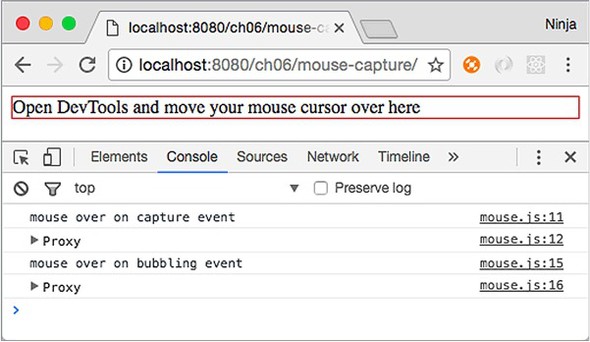

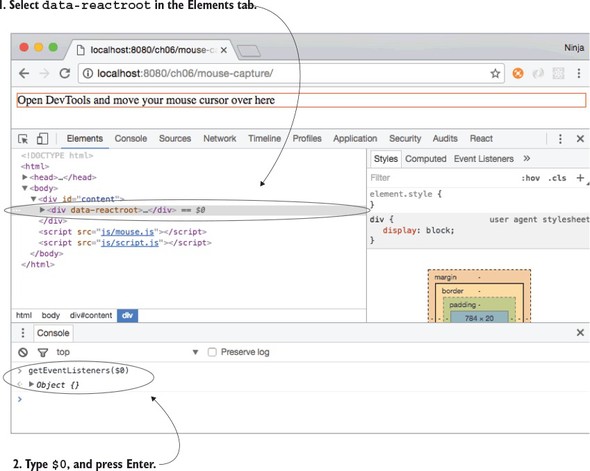

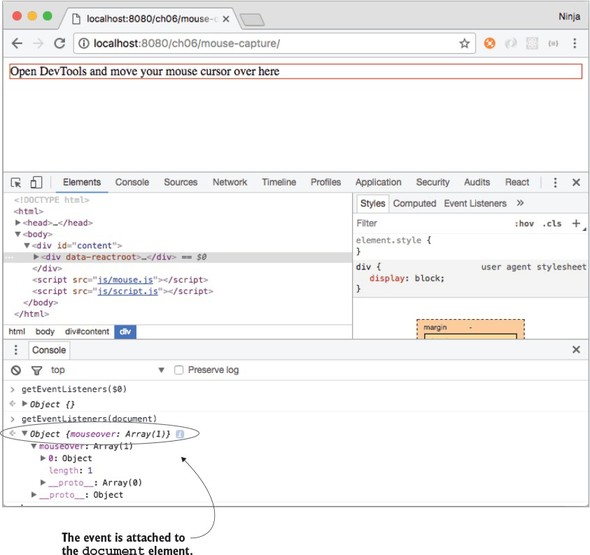

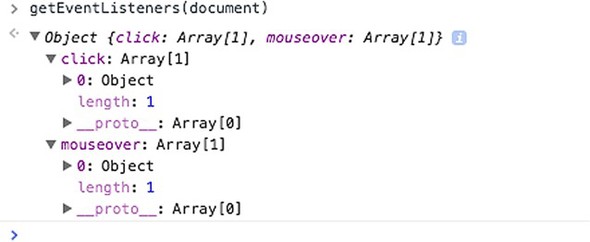

6.1.1. Capture and bubbling phases

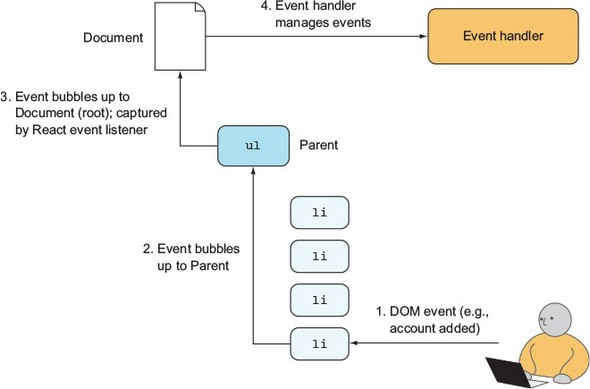

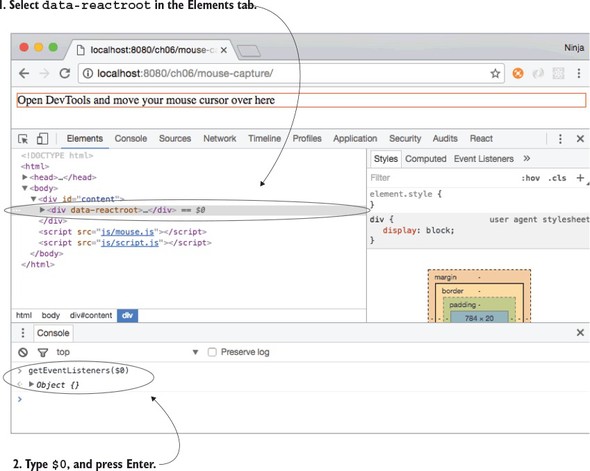

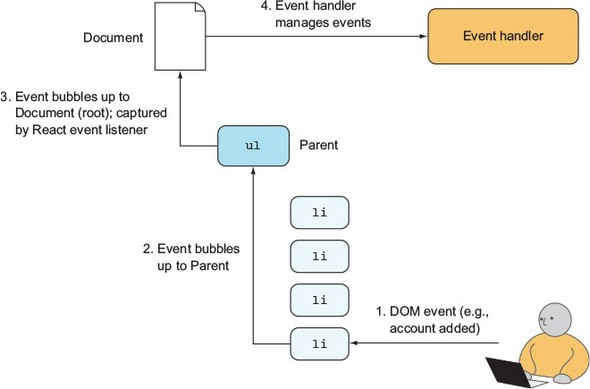

6.1.2. React events under the hood

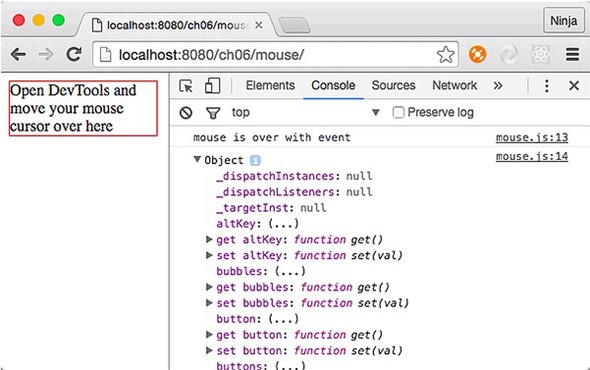

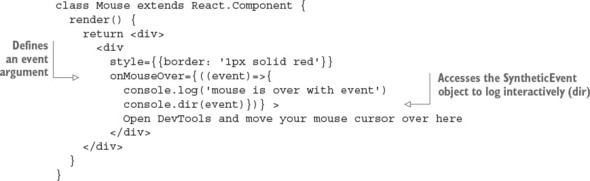

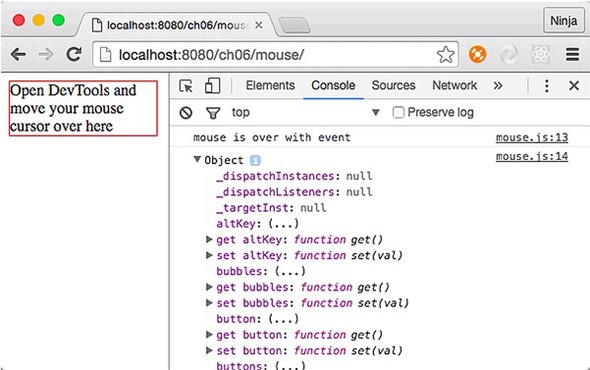

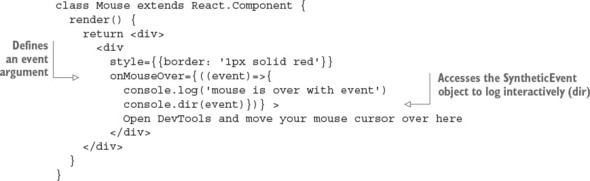

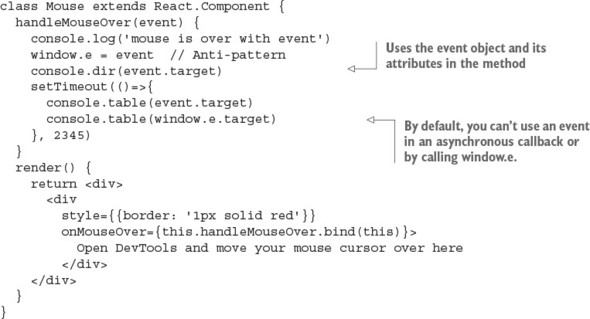

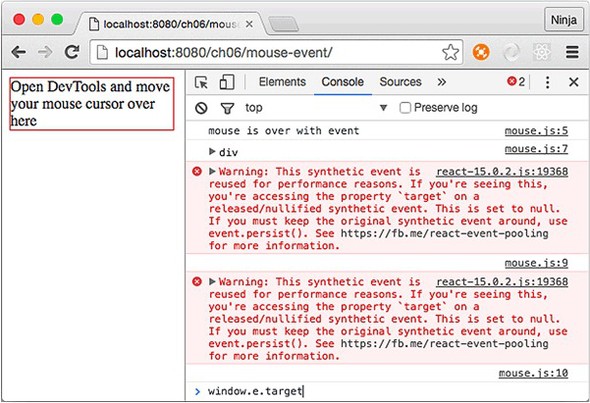

6.1.3. Working with the React SyntheticEvent event object

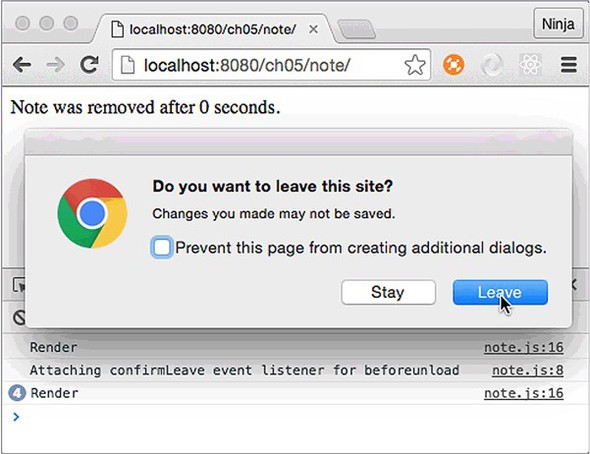

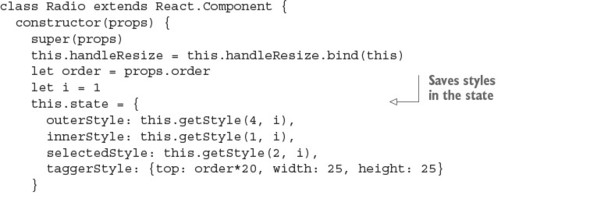

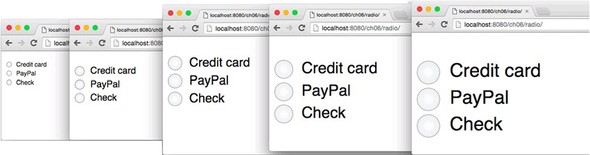

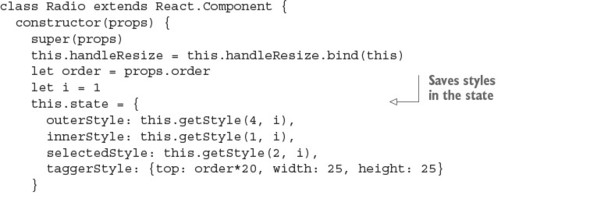

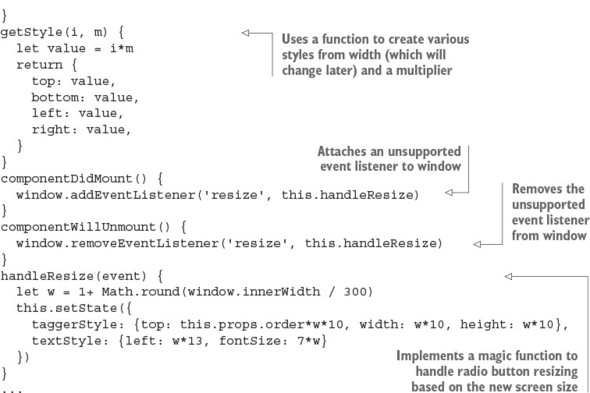

6.2. Responding to DOM events not supported by React

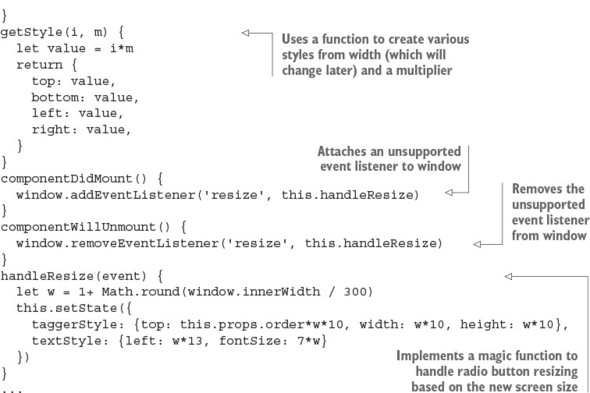

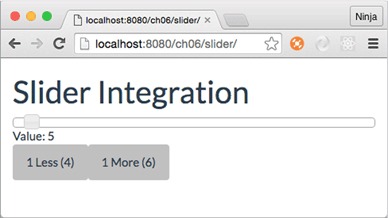

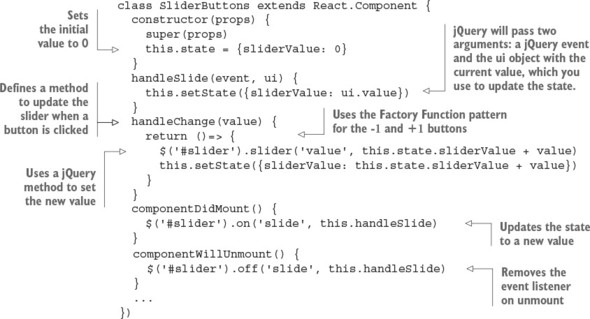

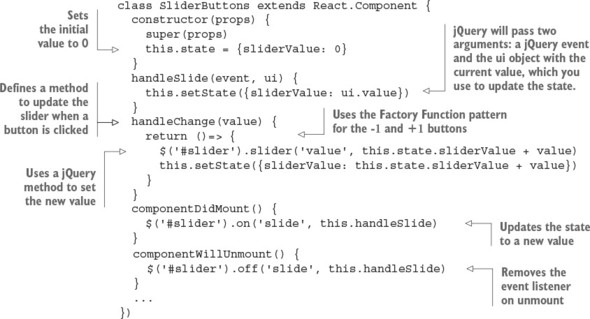

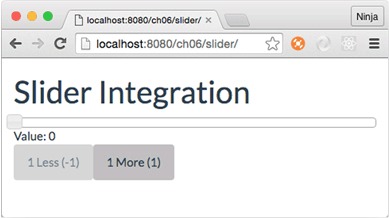

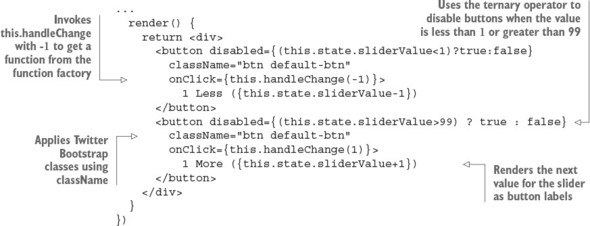

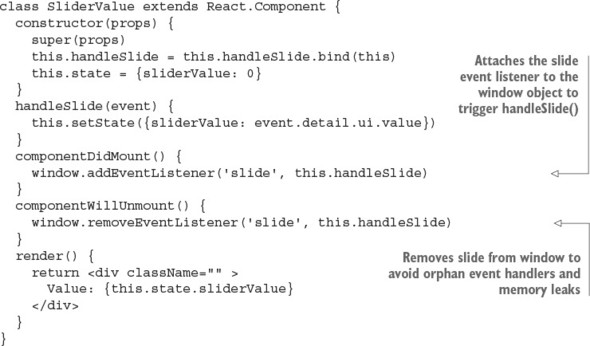

6.3. Integrating React with other libraries: jQuery UI events

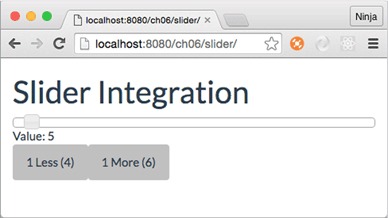

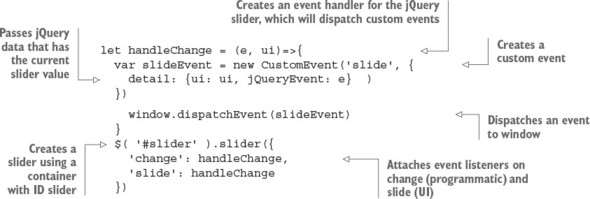

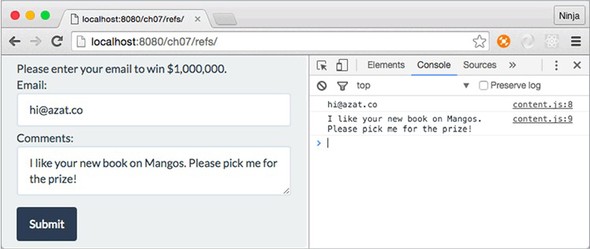

Chapter 7. Working with forms in React

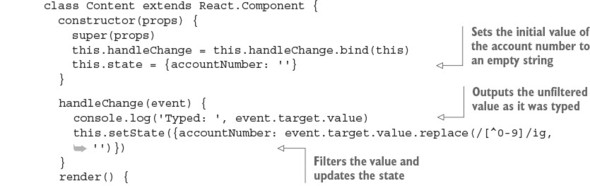

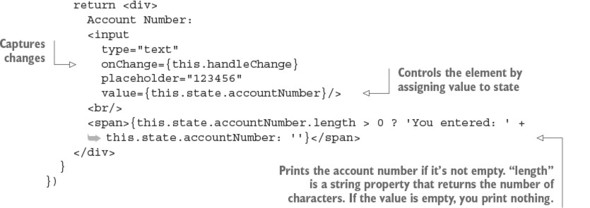

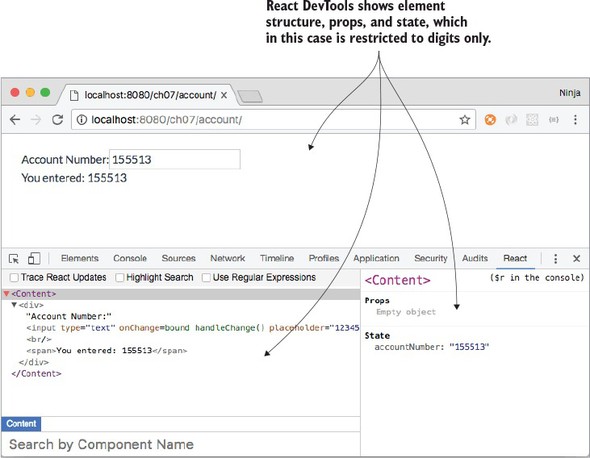

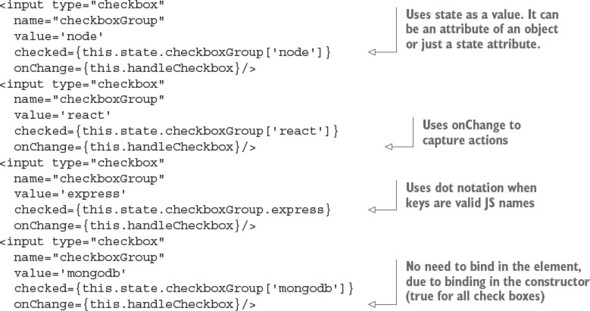

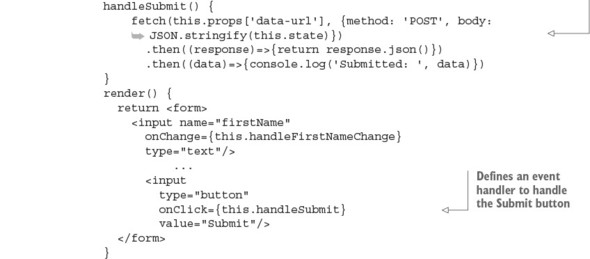

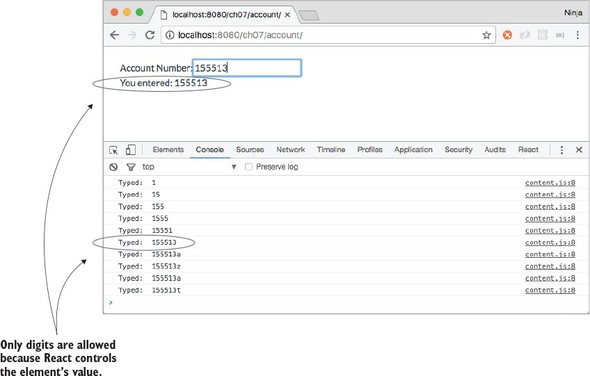

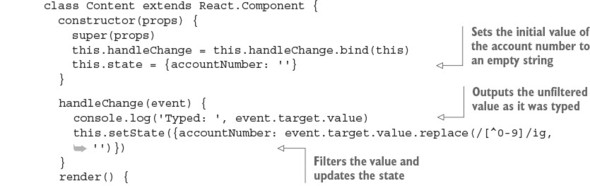

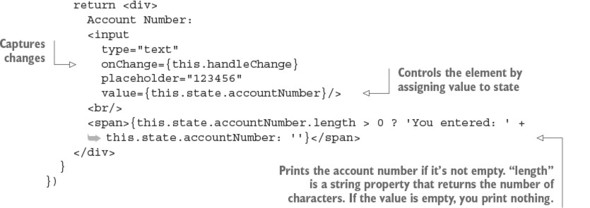

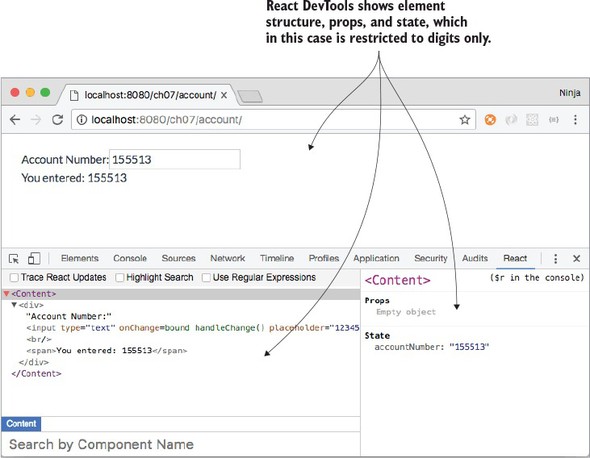

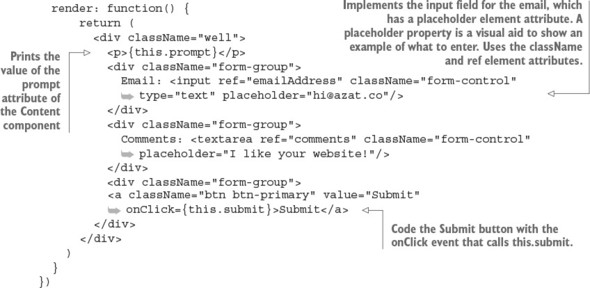

7.1. The recommended way to work with forms in React

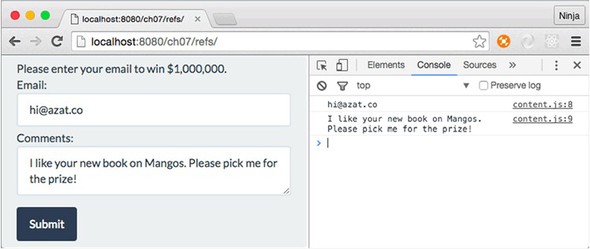

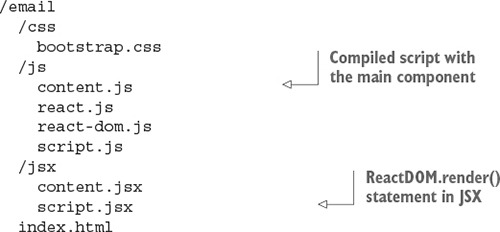

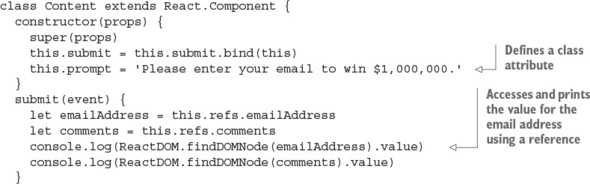

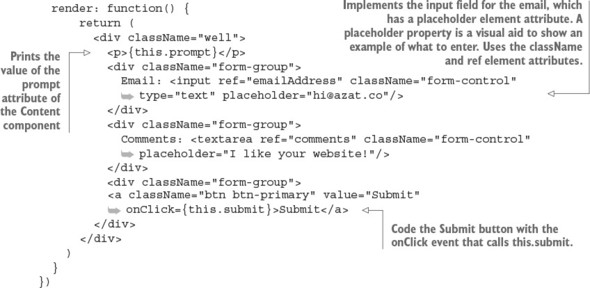

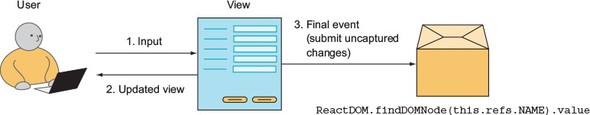

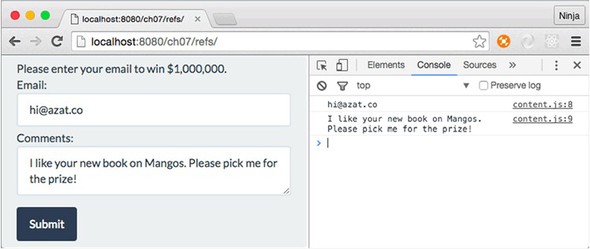

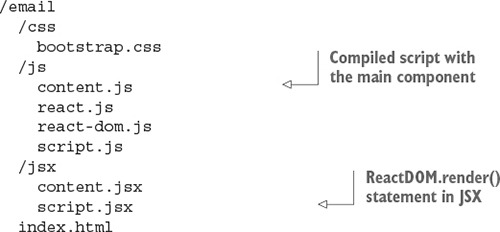

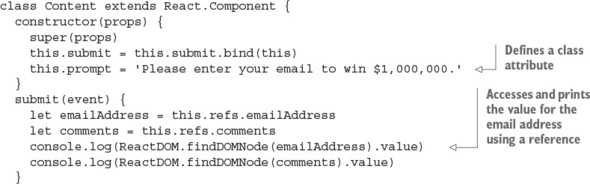

7.2. Alternative ways to work with forms

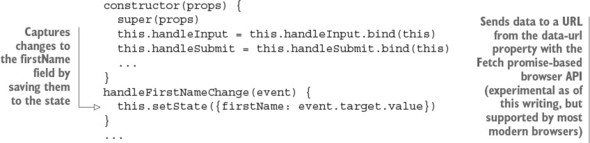

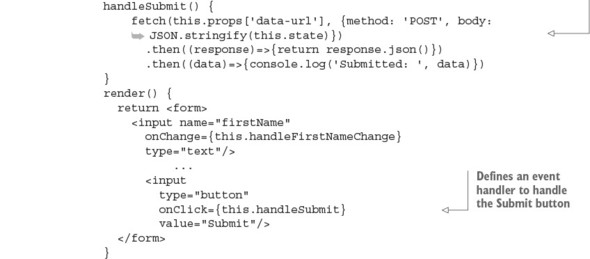

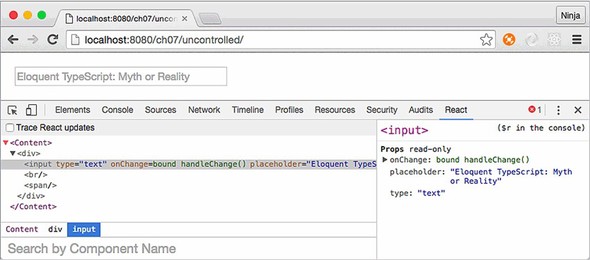

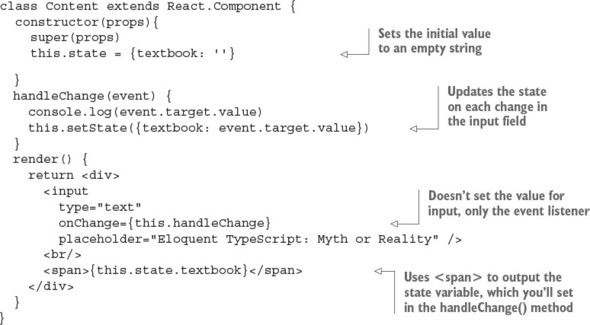

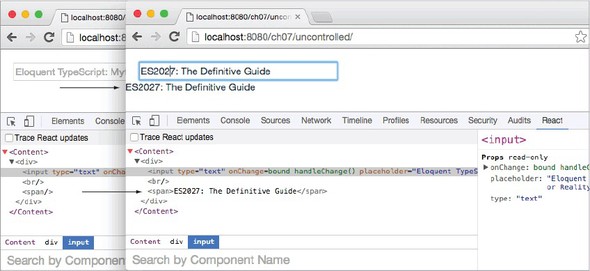

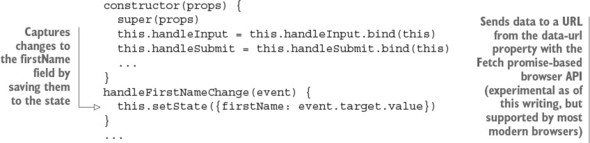

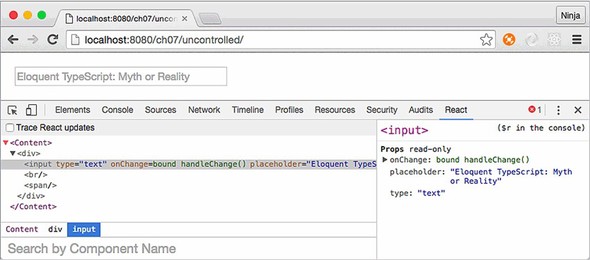

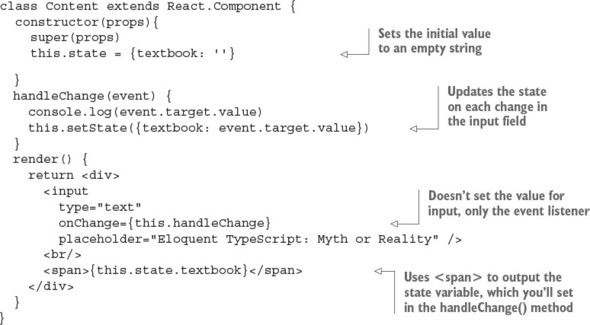

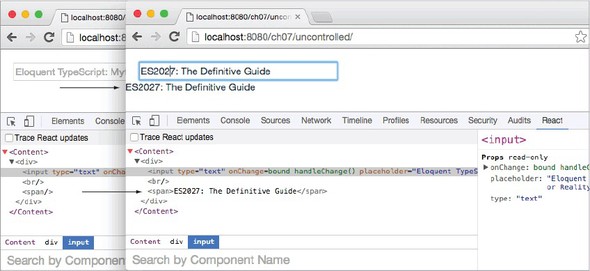

7.2.1. Uncontrolled elements with change capturing

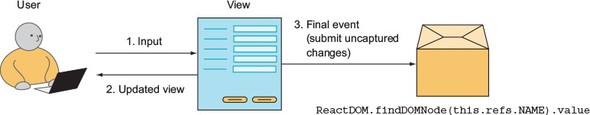

7.2.2. Uncontrolled elements without capturing changes

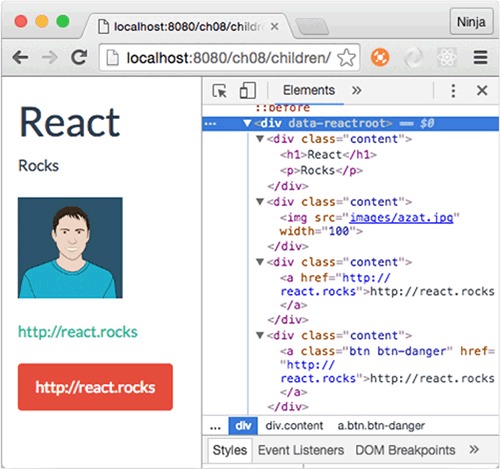

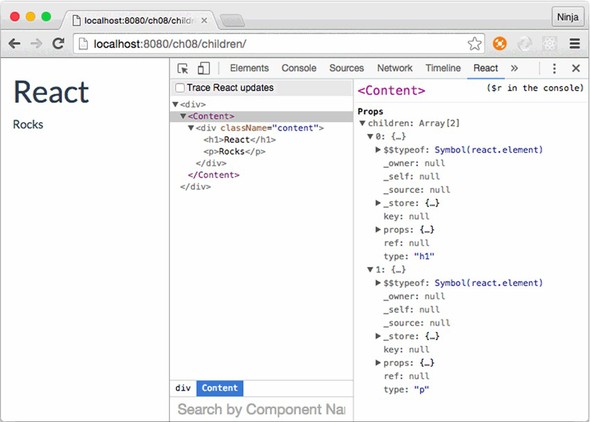

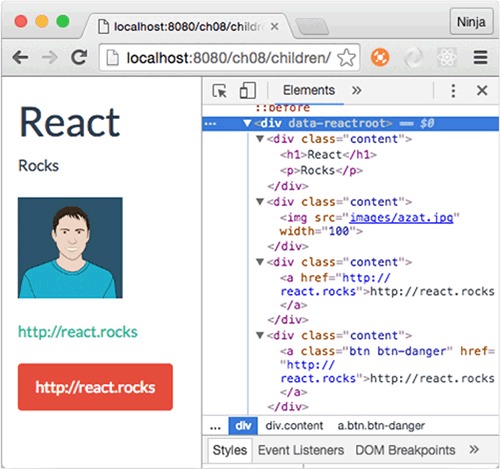

Chapter 8. Scaling React components

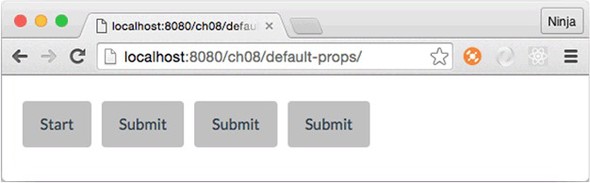

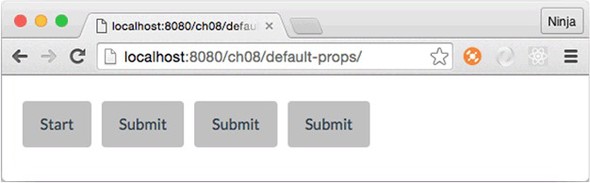

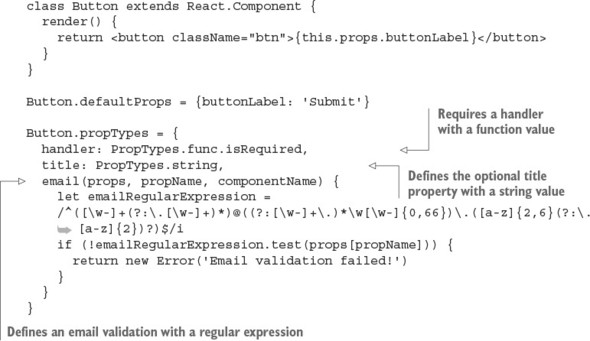

8.1. Default properties in components

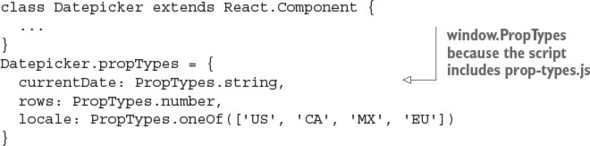

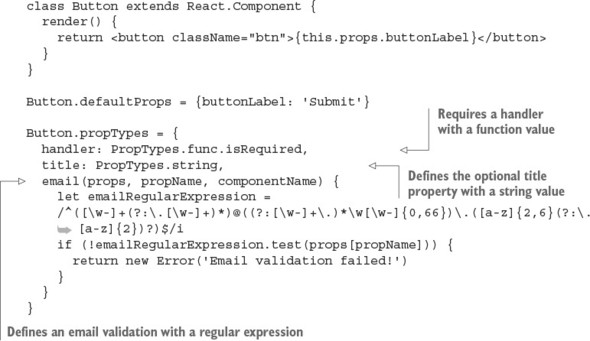

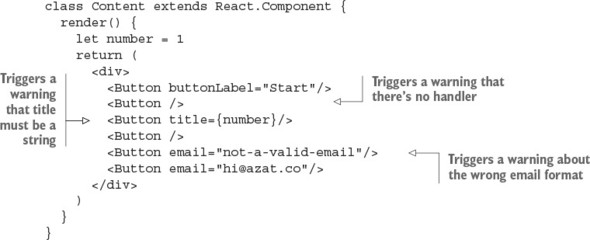

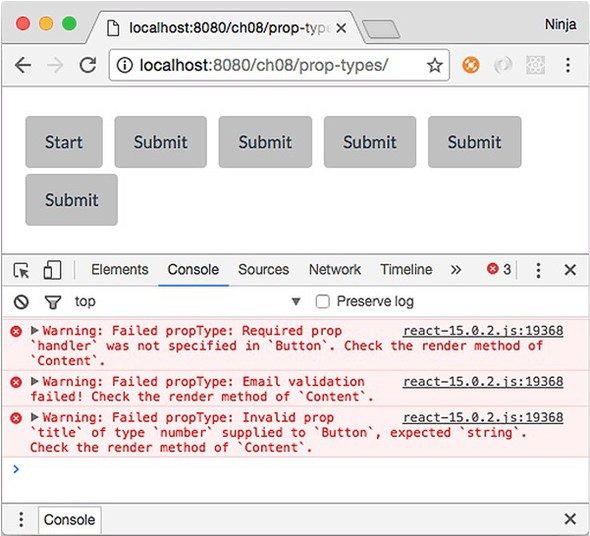

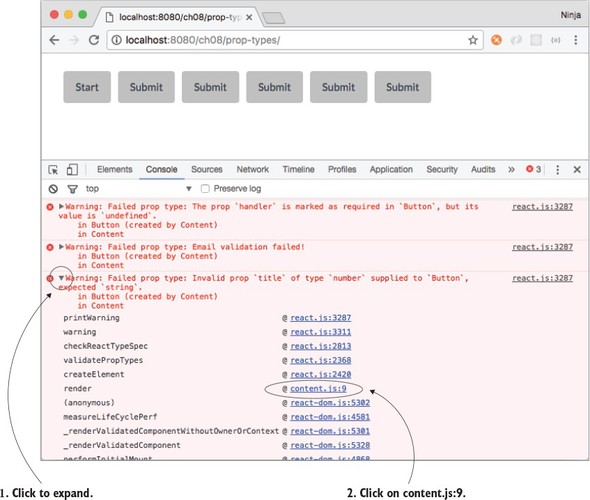

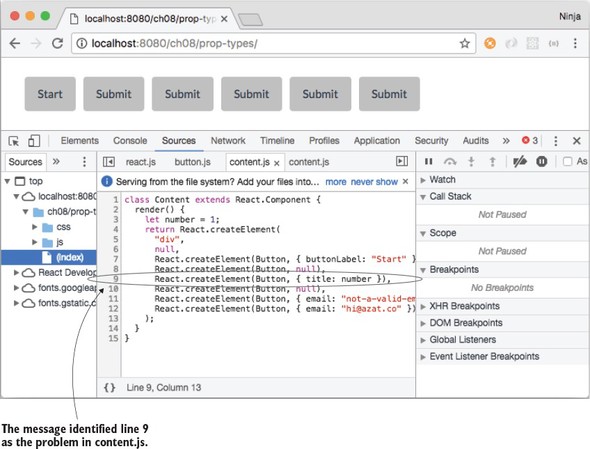

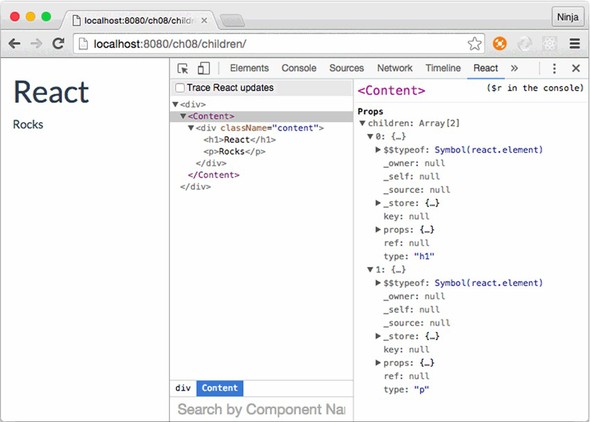

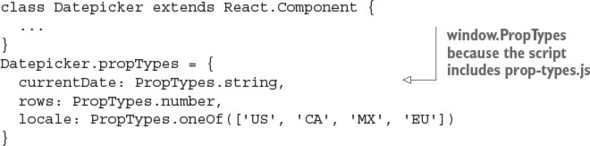

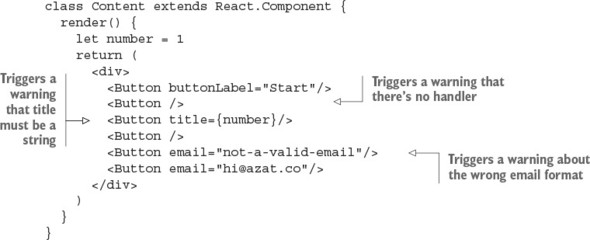

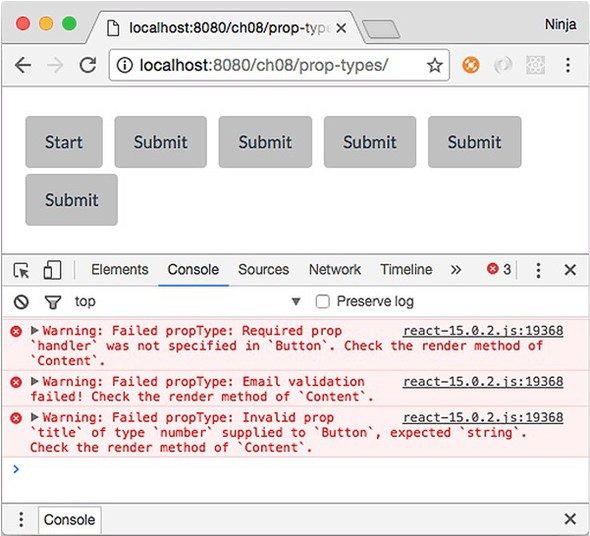

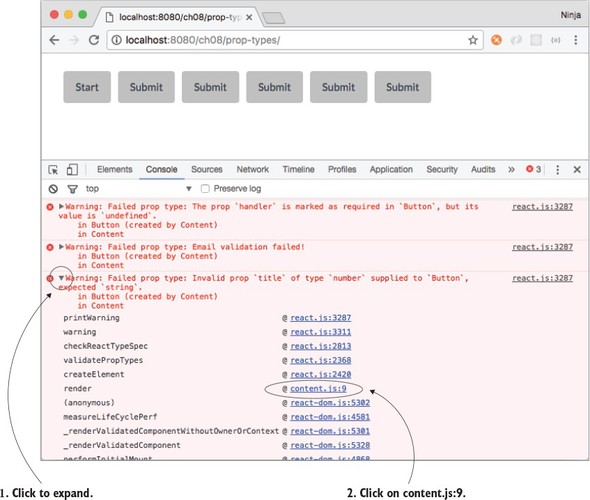

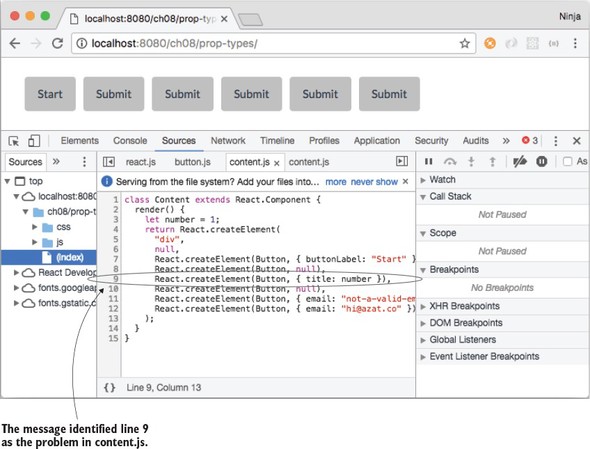

8.2. React property types and validation

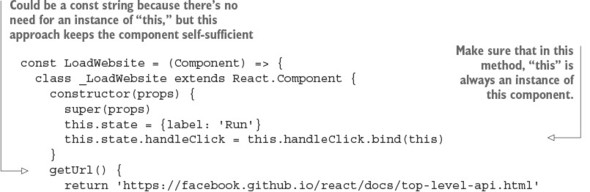

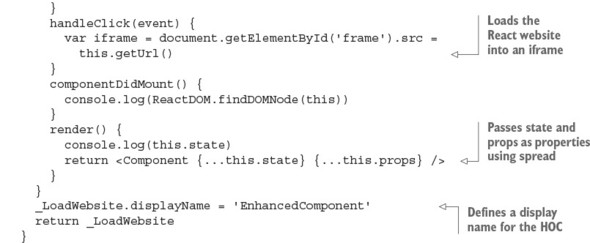

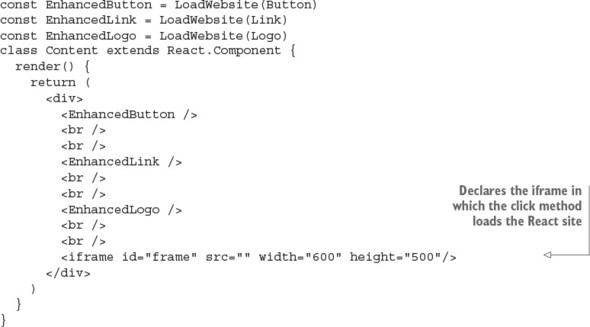

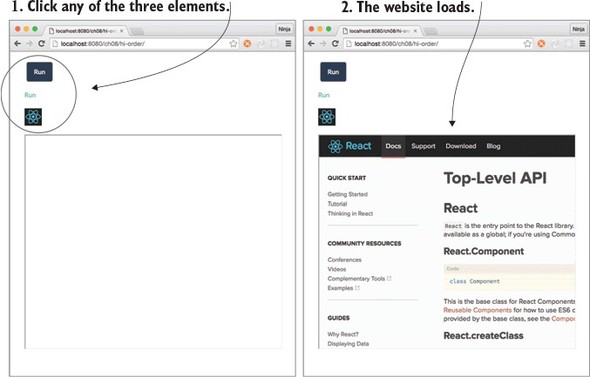

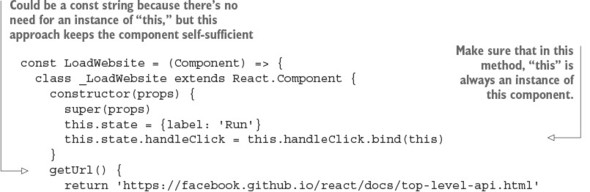

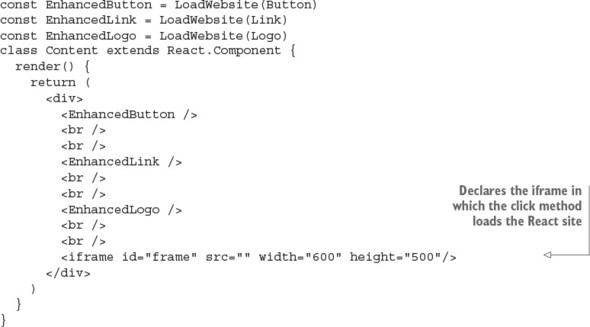

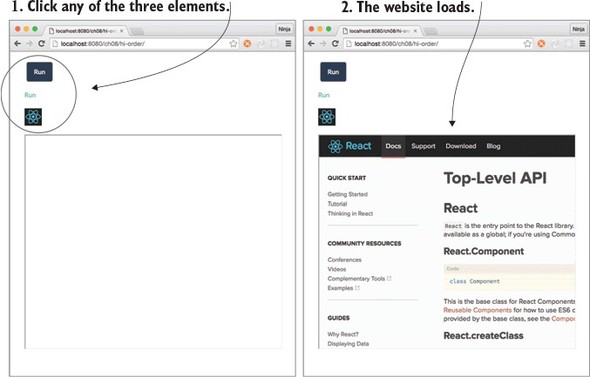

8.4. Creating React higher-order components for code reuse

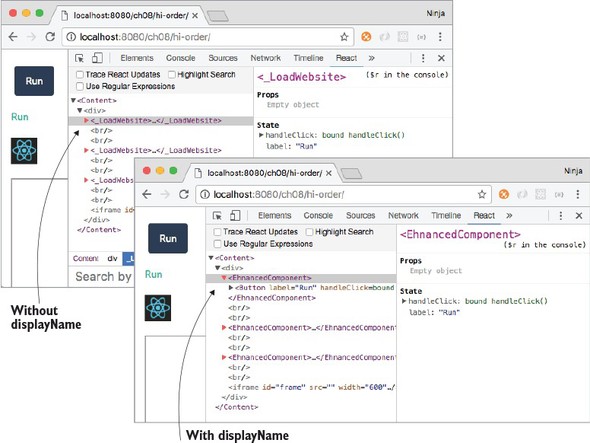

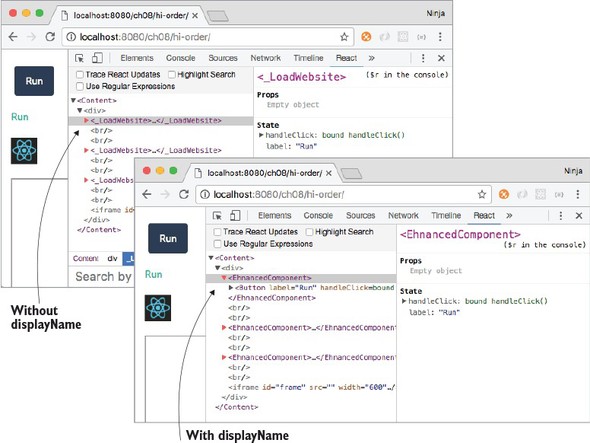

8.4.1. Using displayName: distinguishing child components from their parent

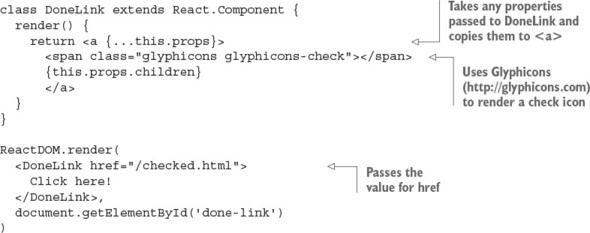

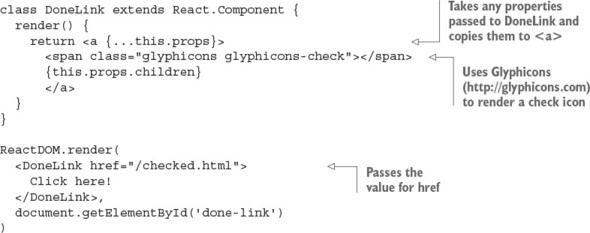

8.4.2. Using the spread operator: passing all of your attributes

8.5. Best practices: presentational vs. container components

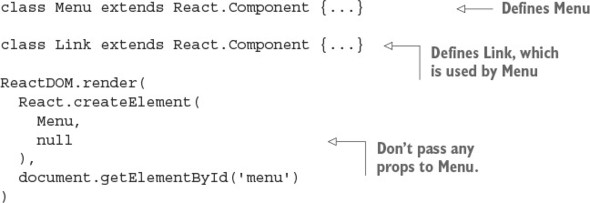

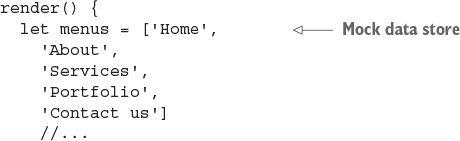

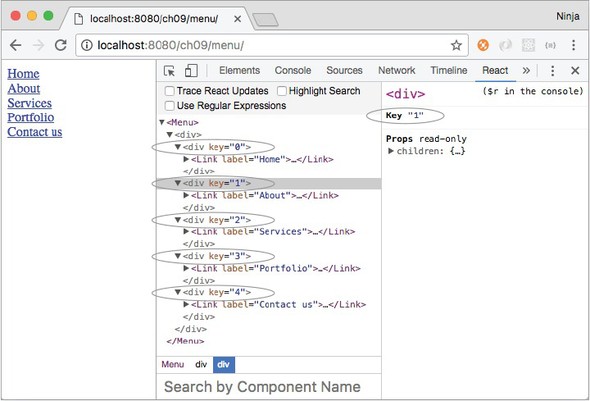

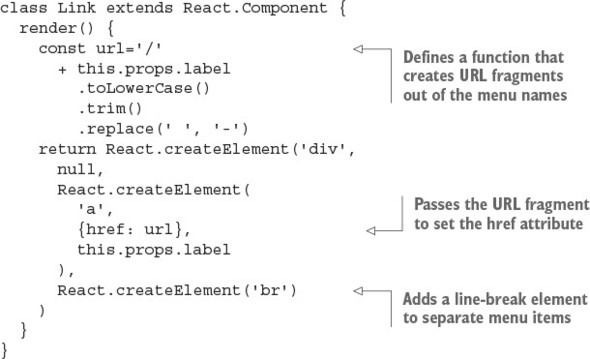

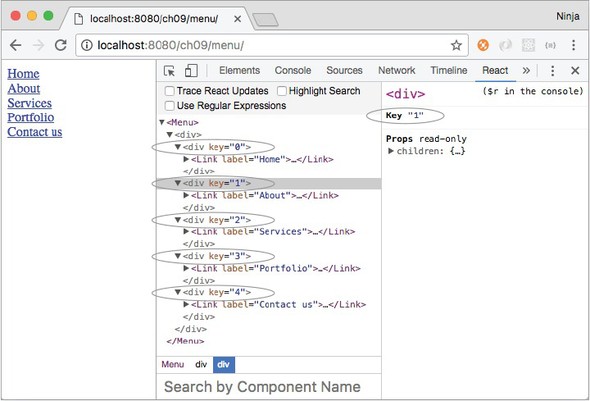

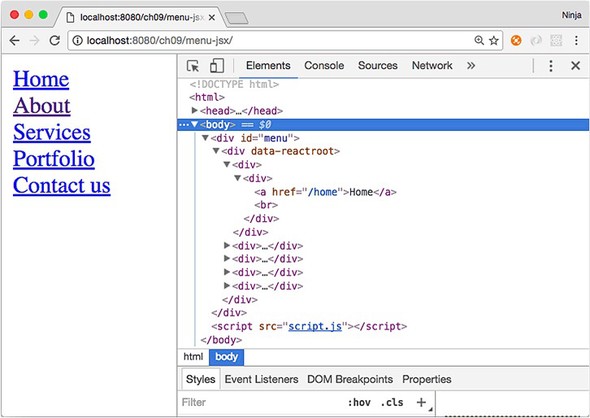

Chapter 9. Project: Menu component

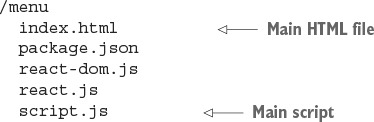

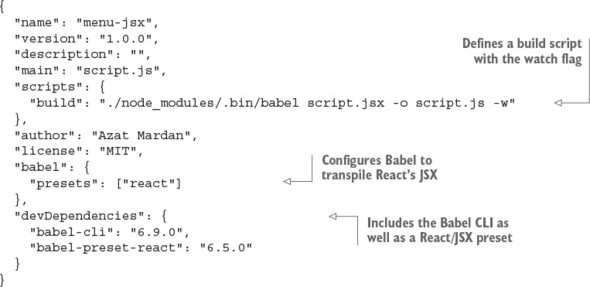

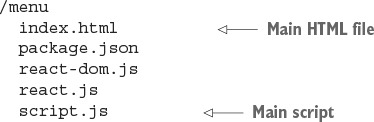

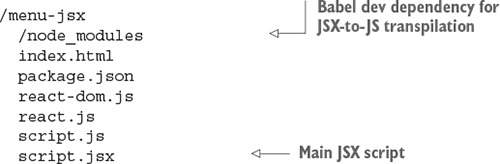

9.1. Project structure and scaffolding

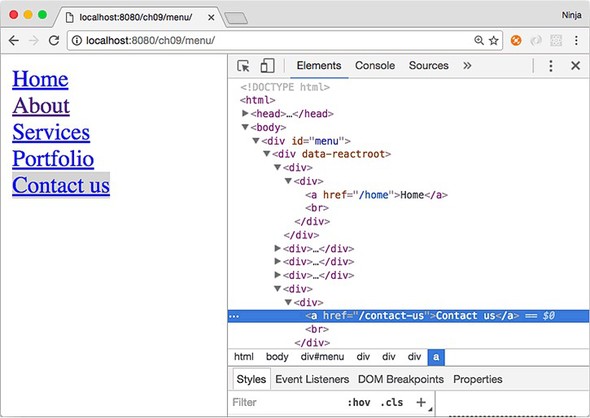

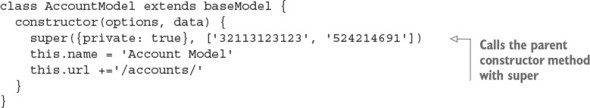

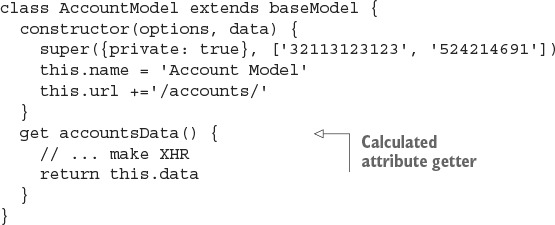

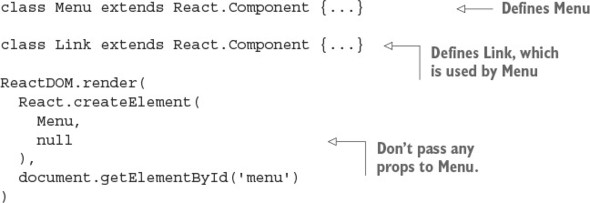

9.2. Building the menu without JSX

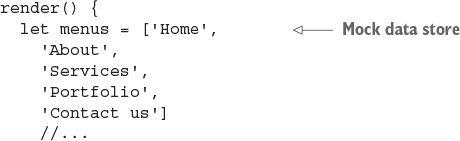

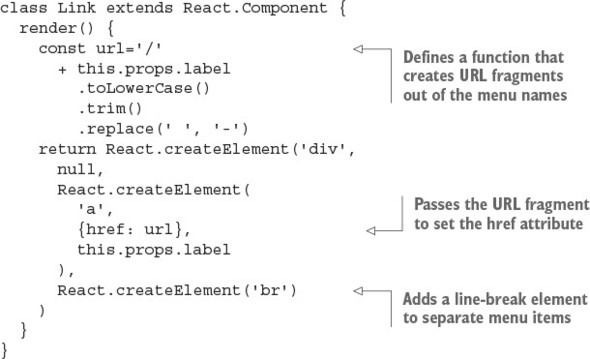

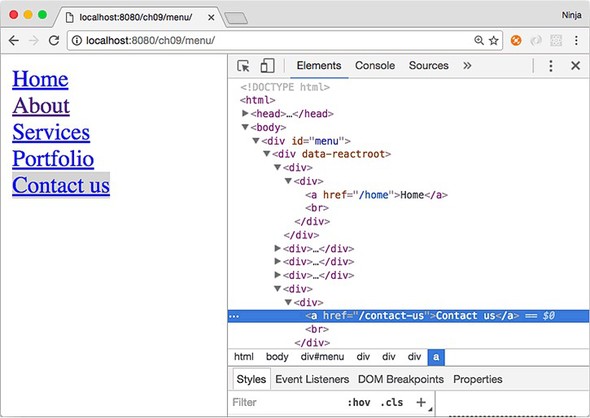

9.3.1. Refactoring the Menu component

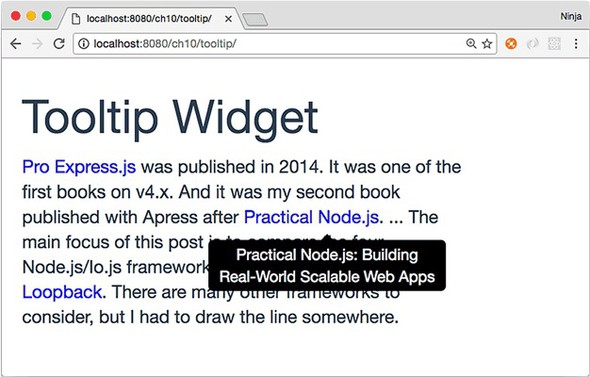

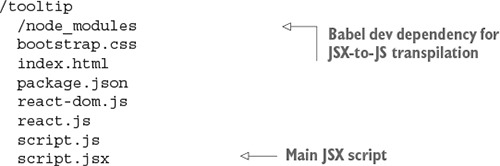

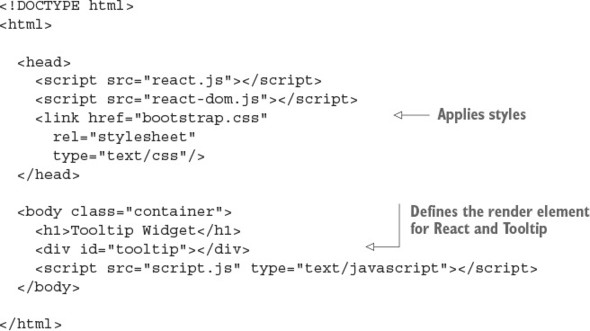

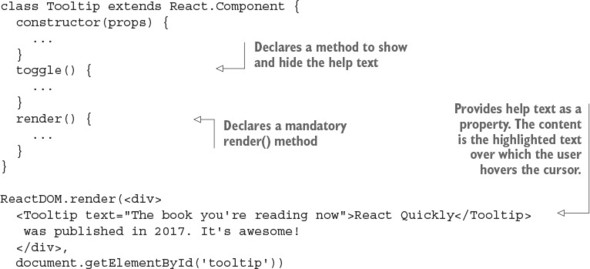

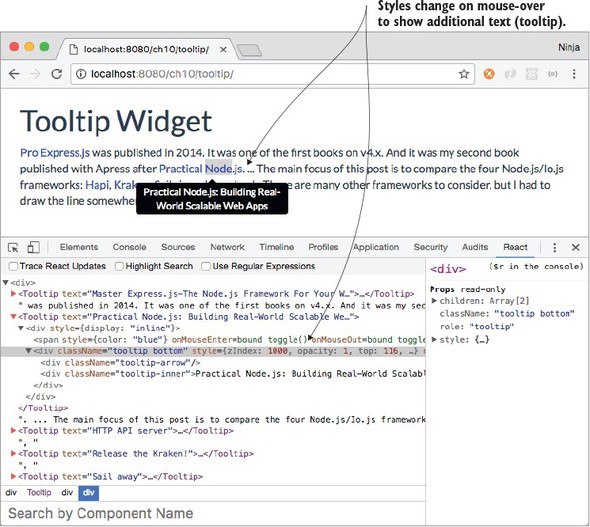

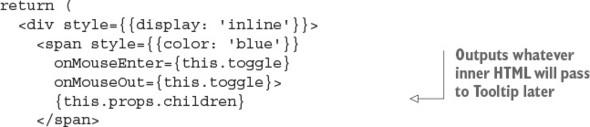

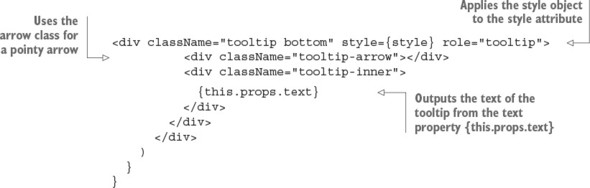

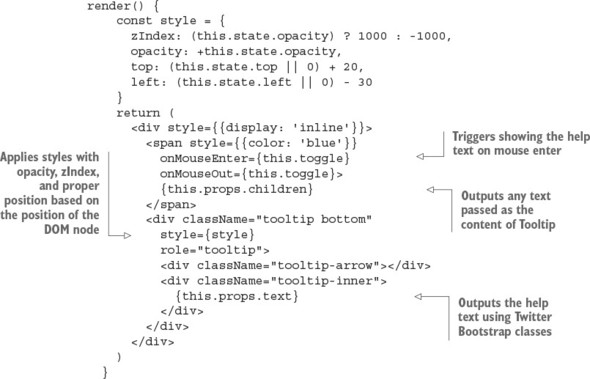

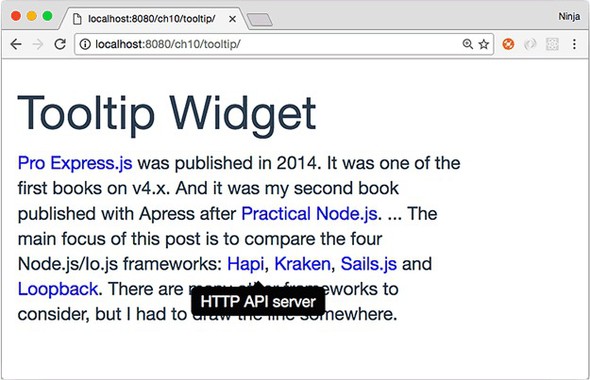

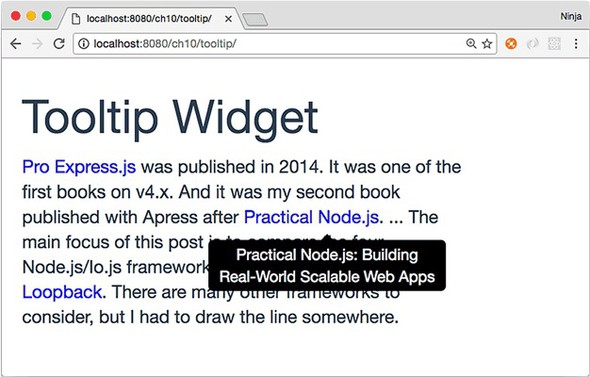

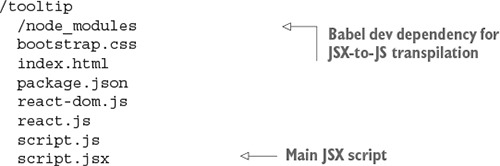

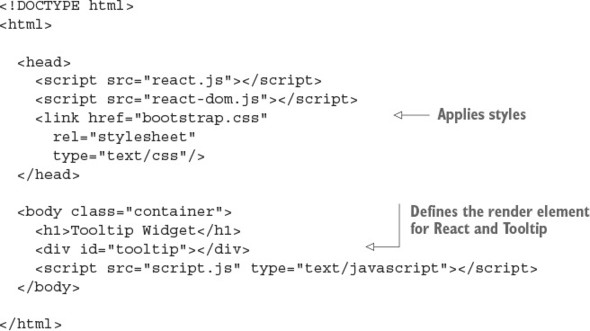

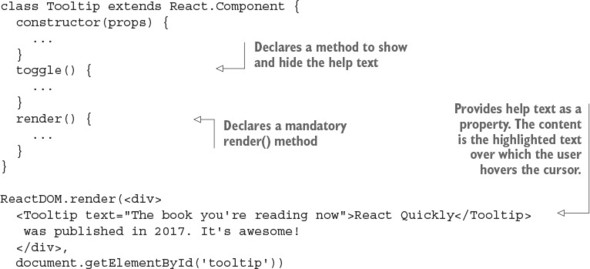

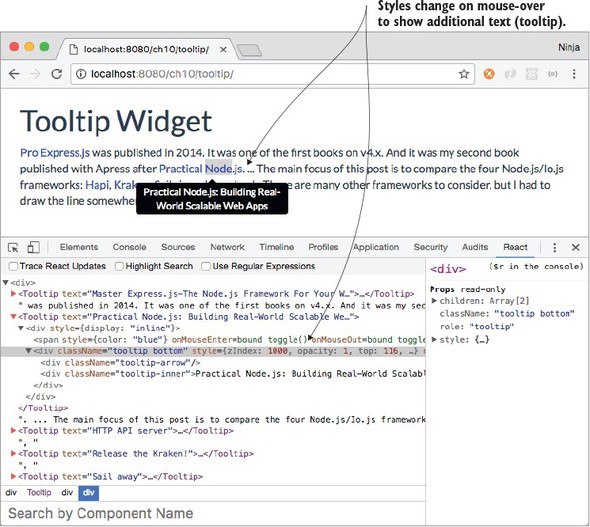

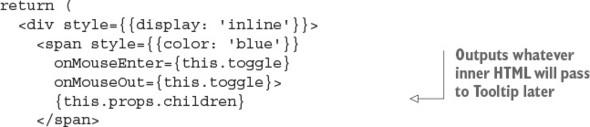

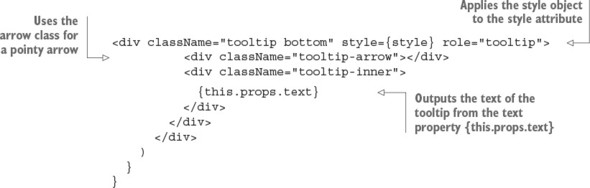

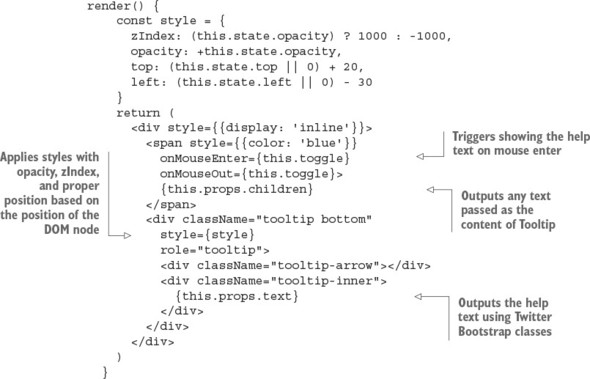

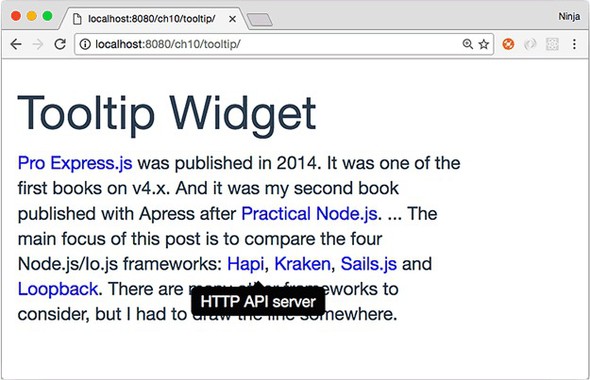

Chapter 10. Project: Tooltip component

10.1. Project structure and scaffolding

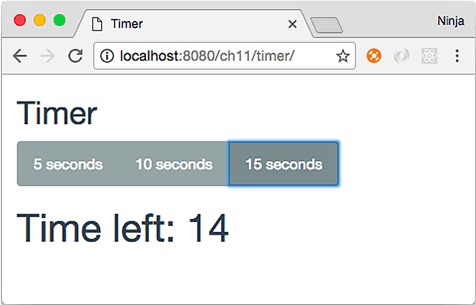

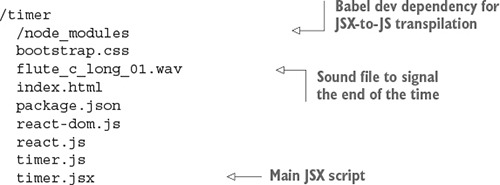

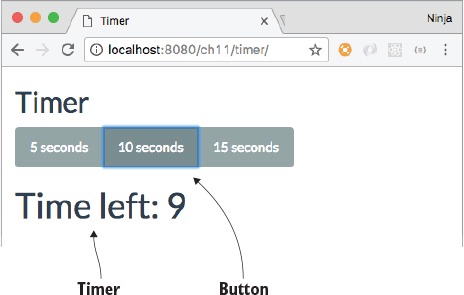

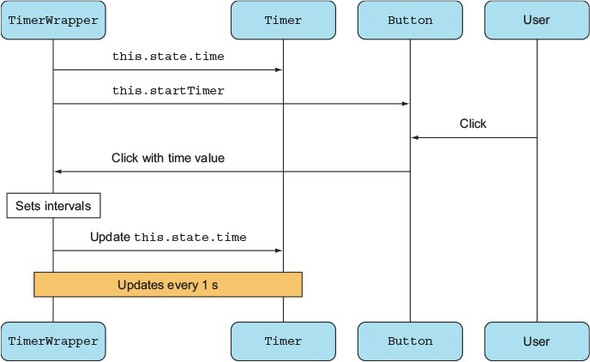

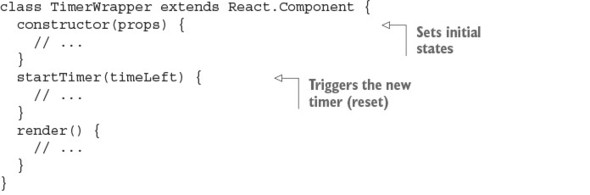

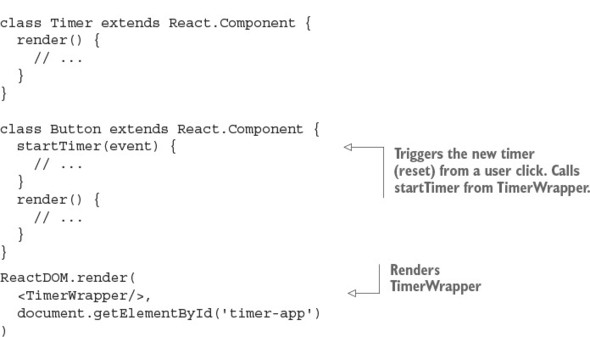

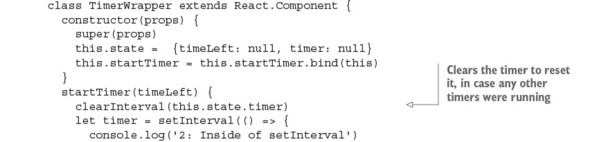

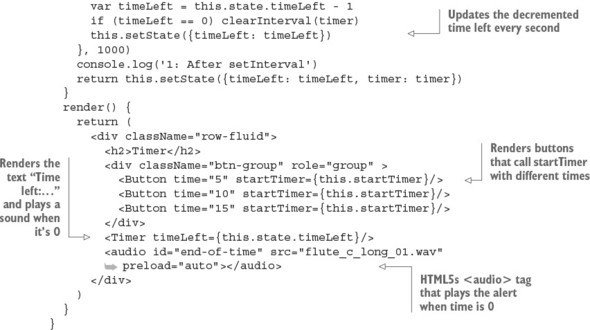

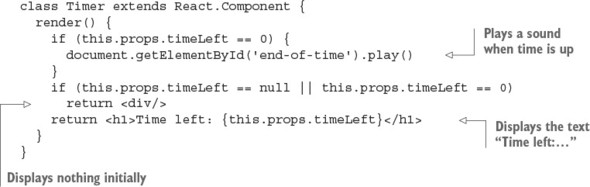

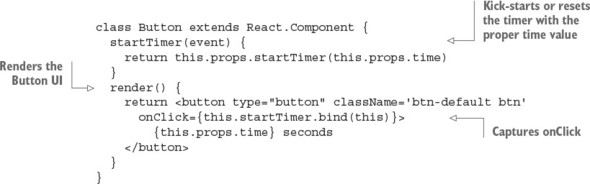

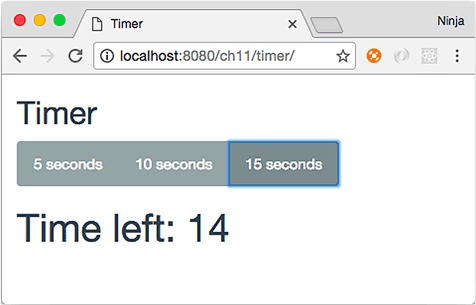

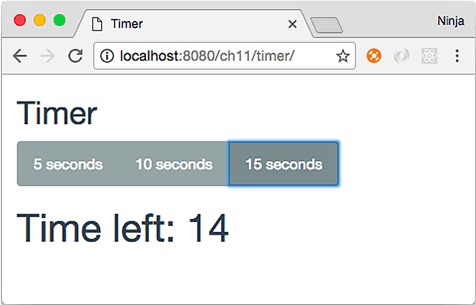

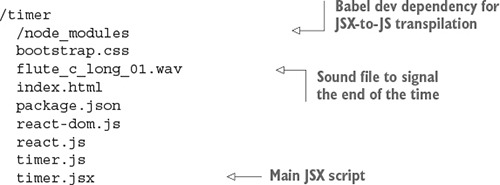

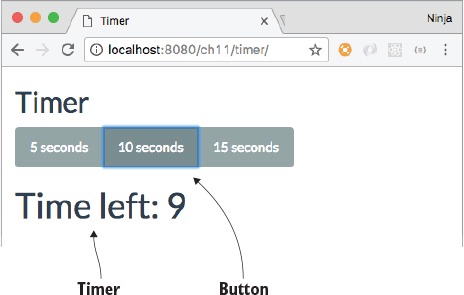

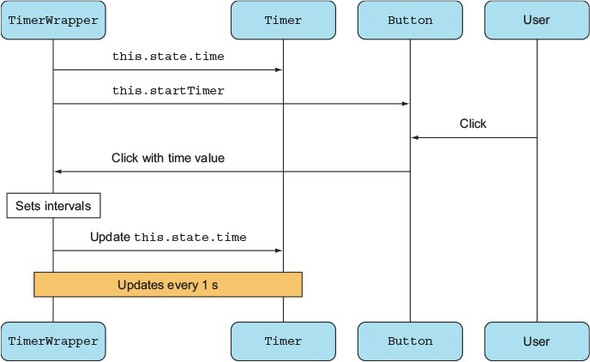

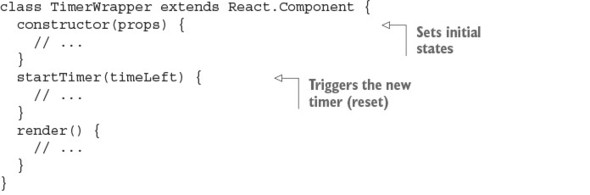

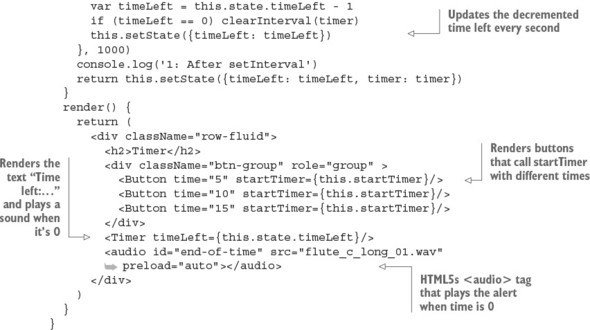

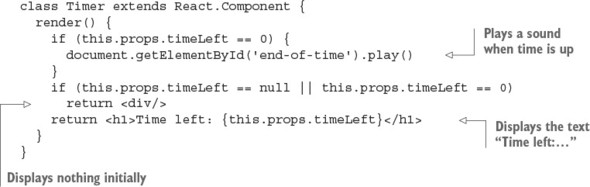

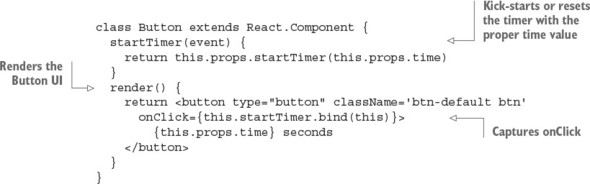

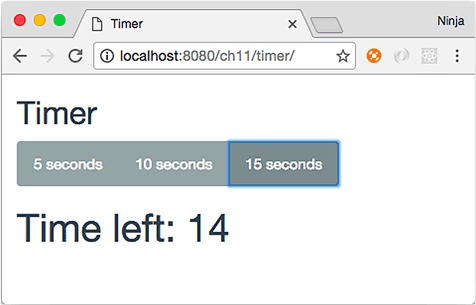

Chapter 11. Project: Timer component

11.1. Project structure and scaffolding

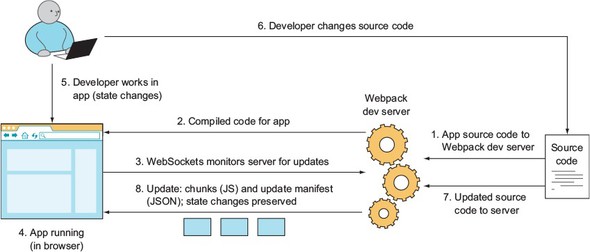

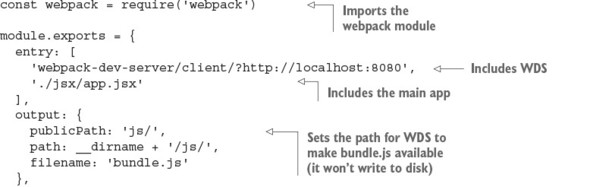

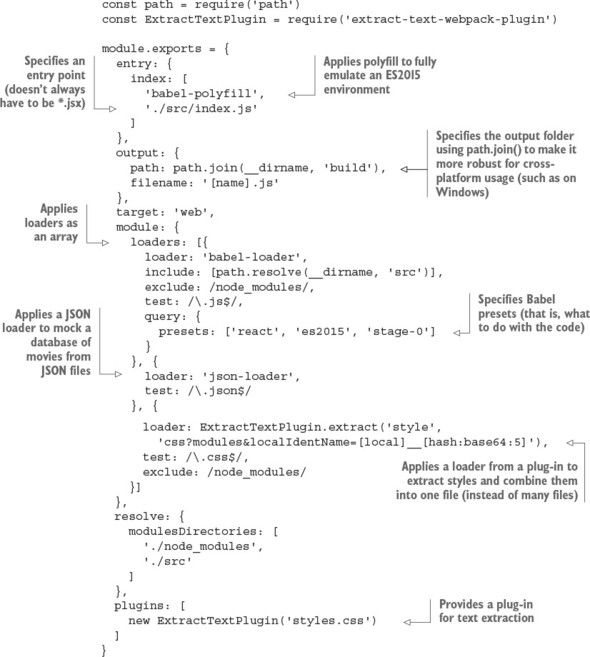

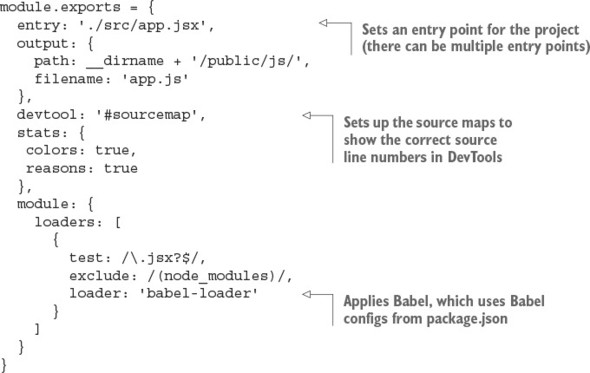

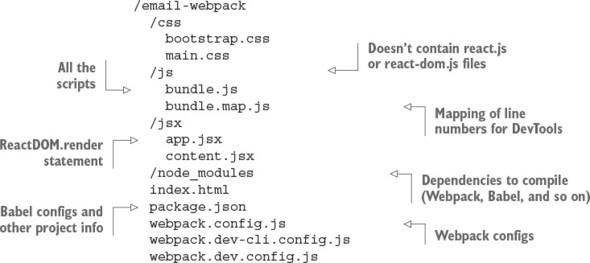

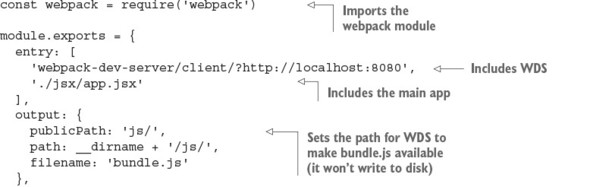

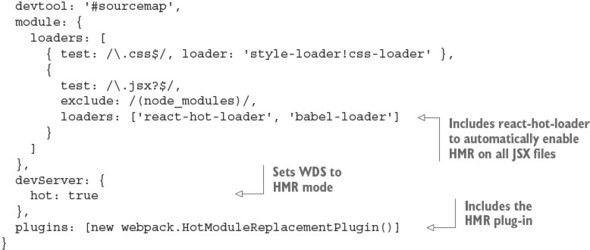

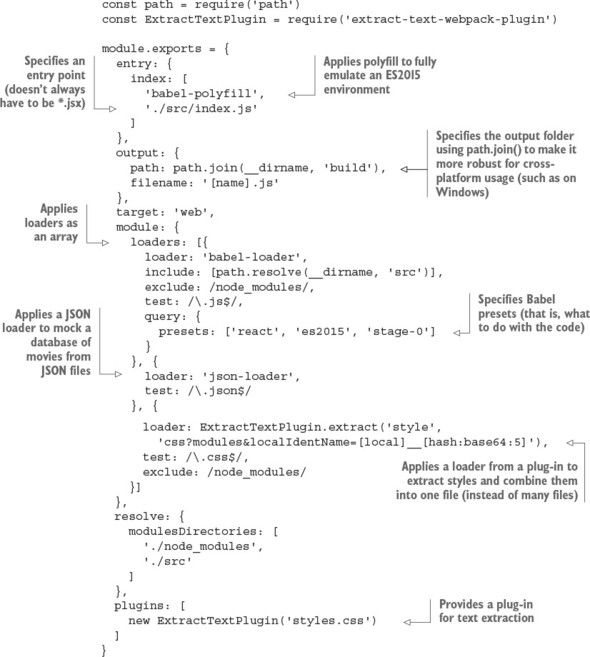

Chapter 12. The Webpack build tool

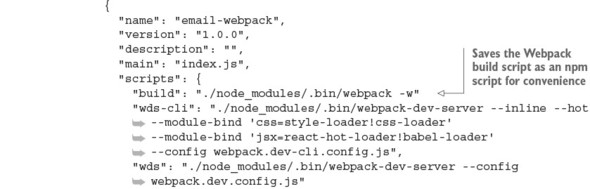

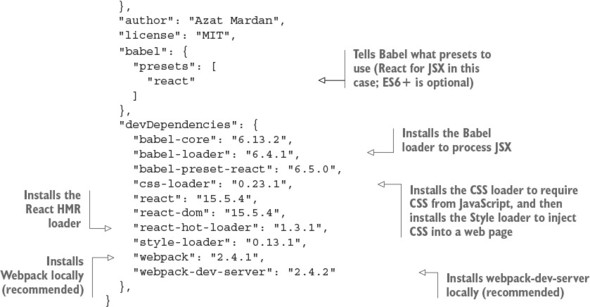

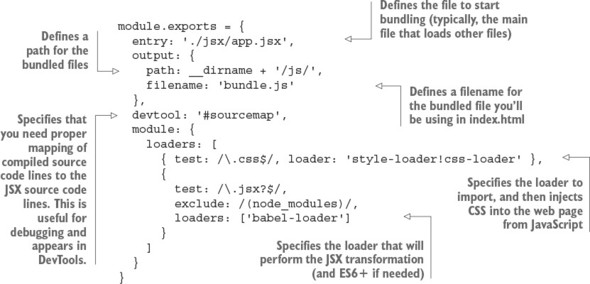

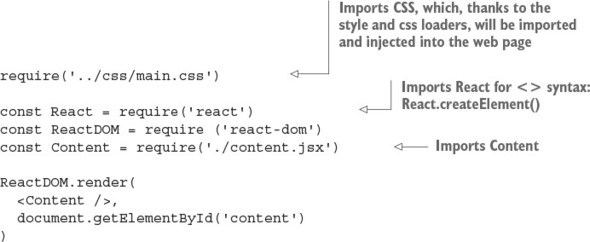

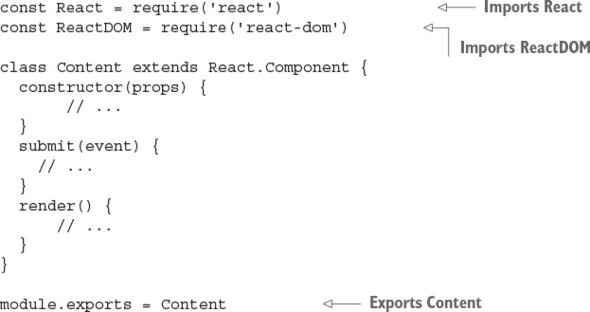

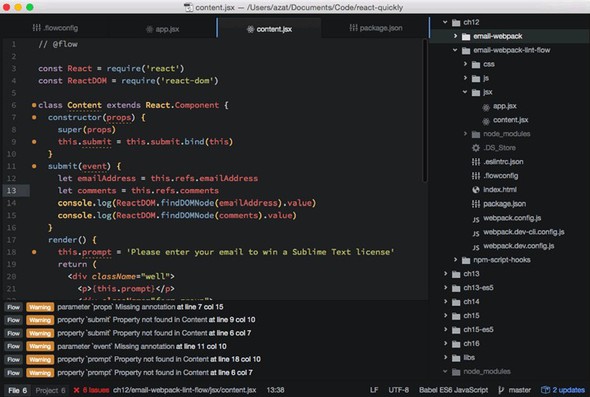

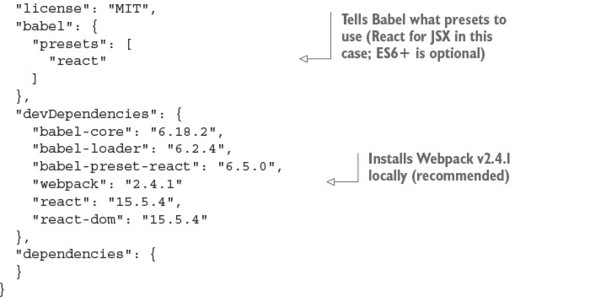

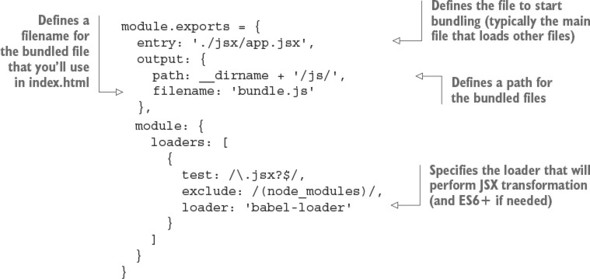

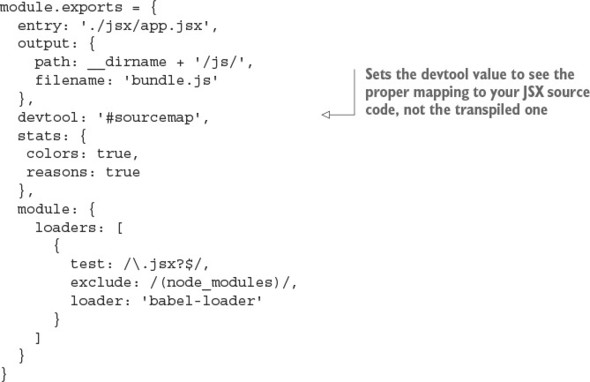

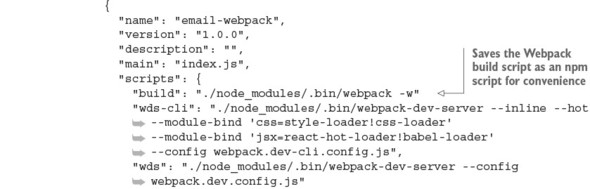

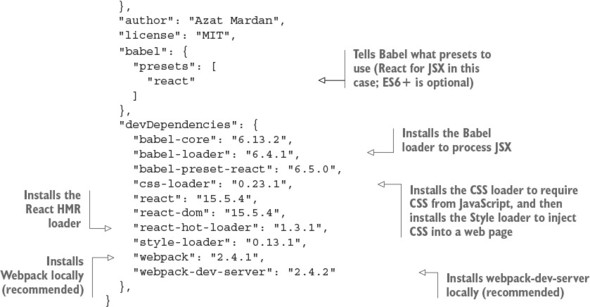

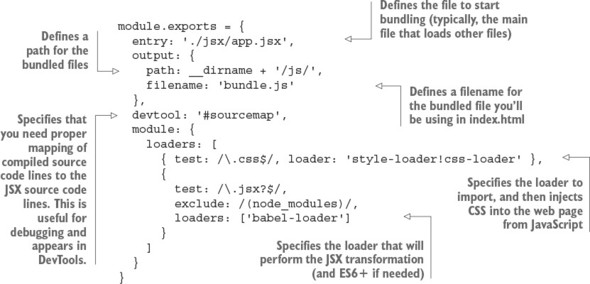

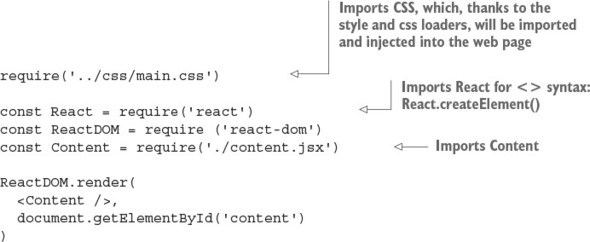

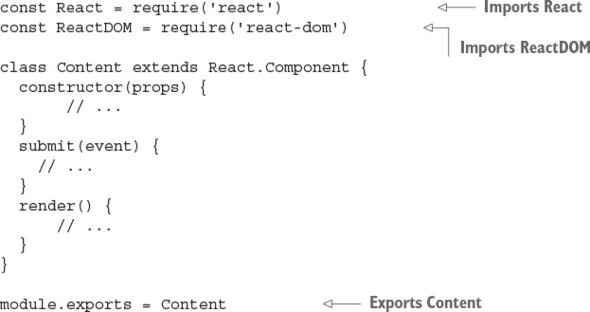

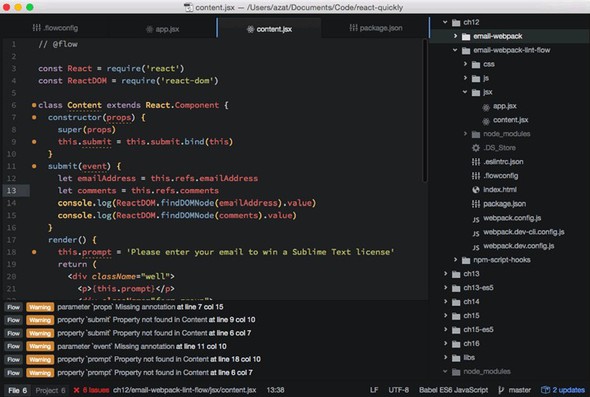

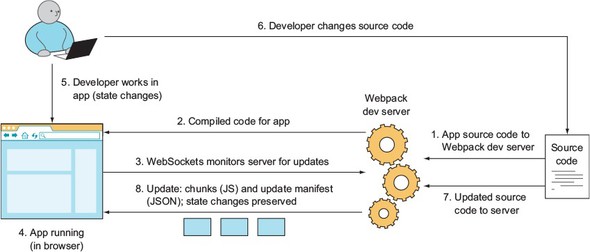

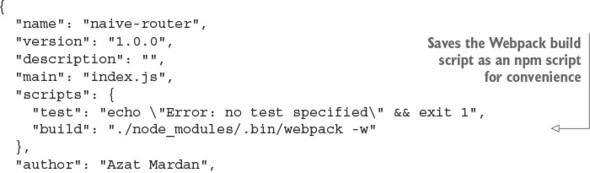

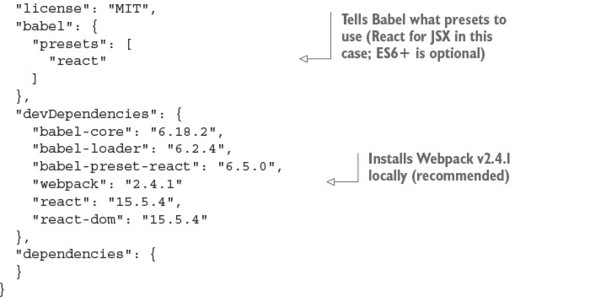

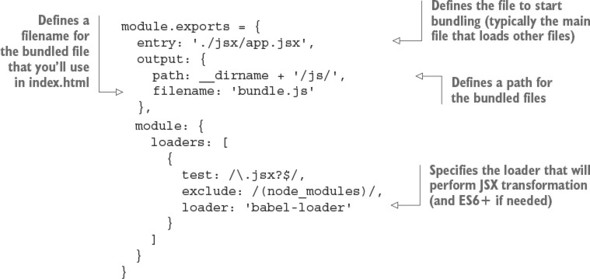

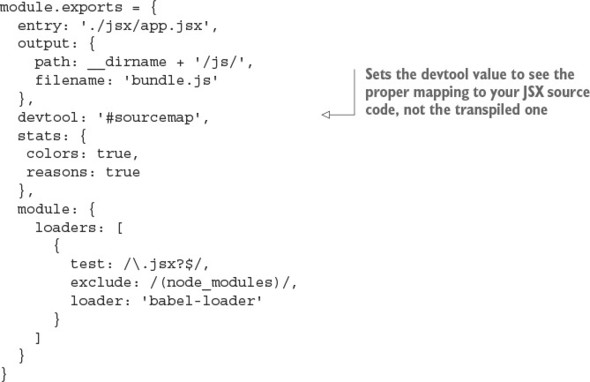

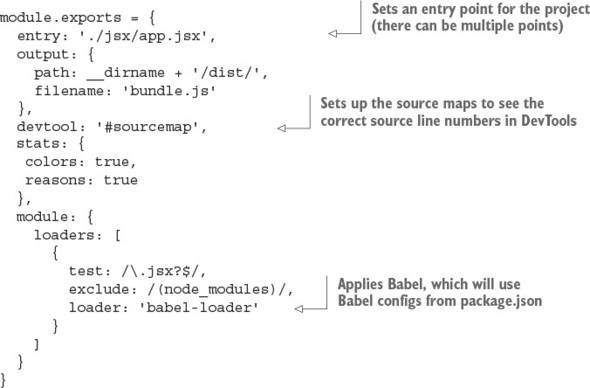

12.2. Adding Webpack to a project

12.4. Running Webpack and testing the build

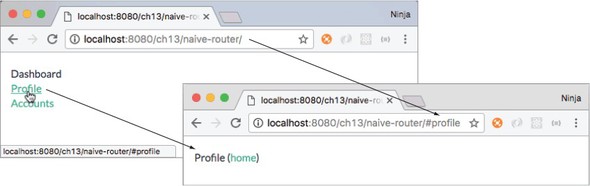

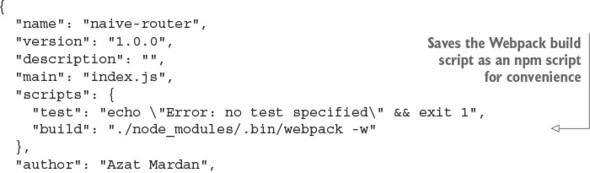

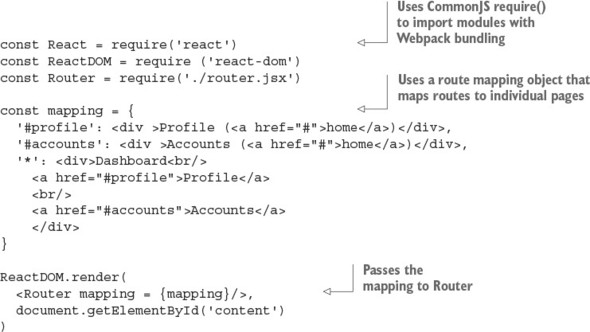

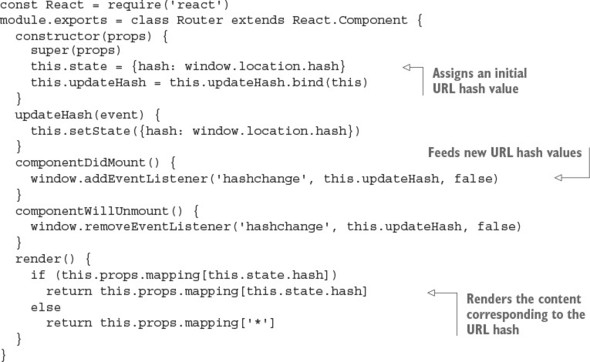

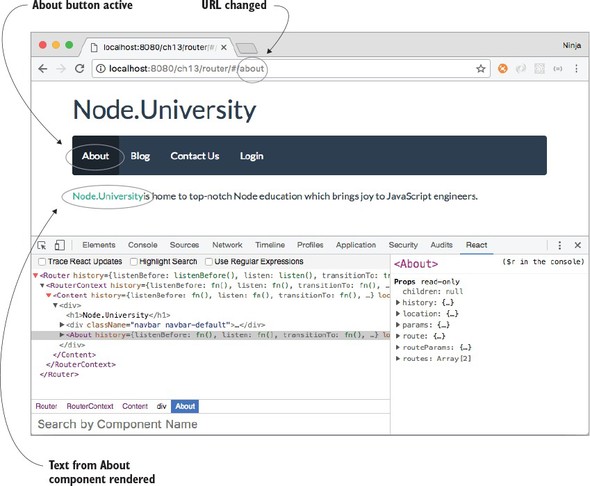

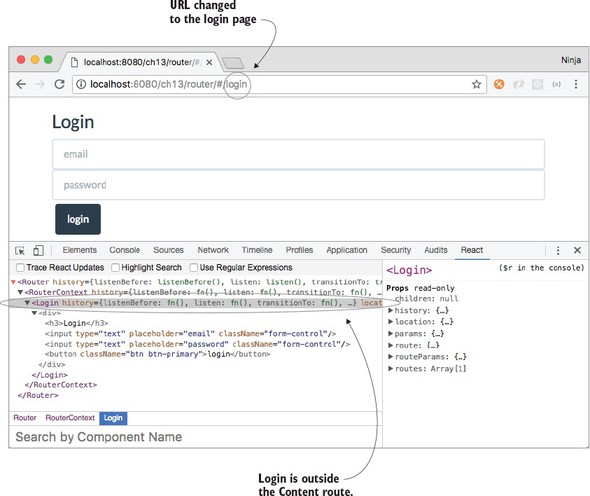

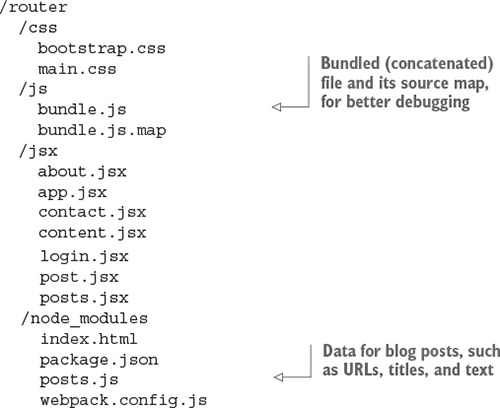

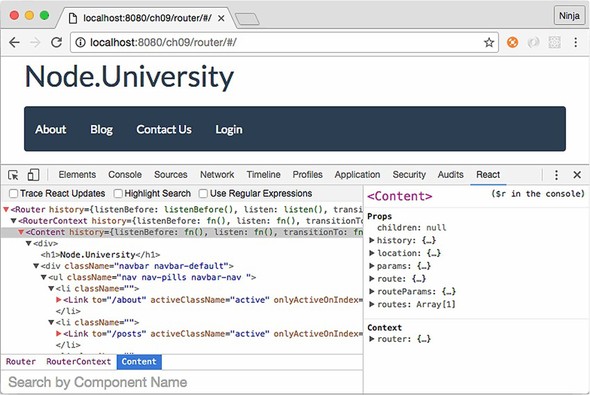

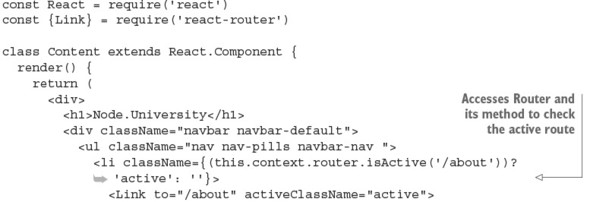

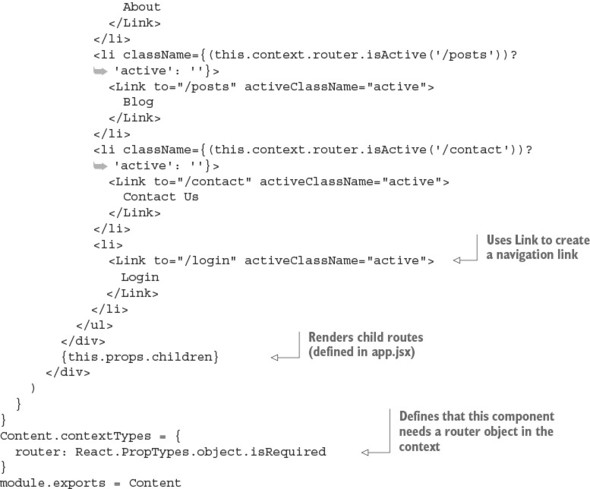

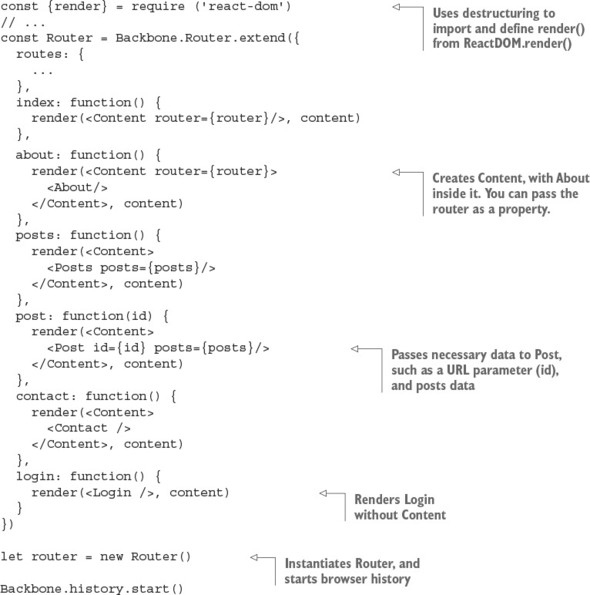

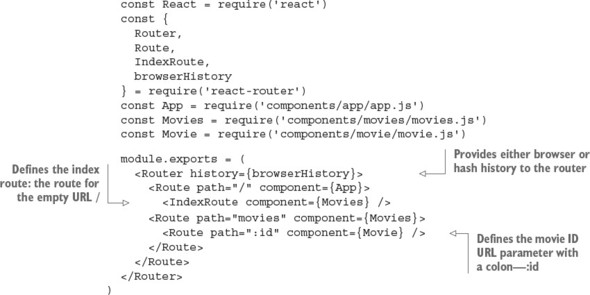

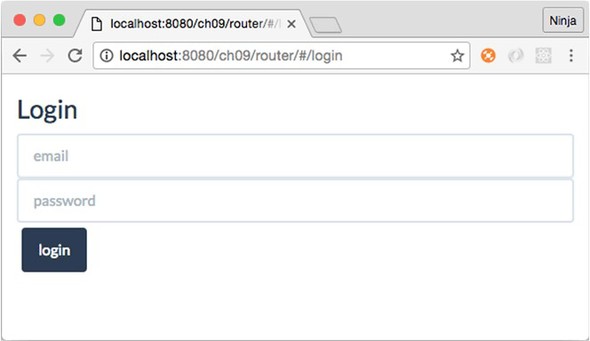

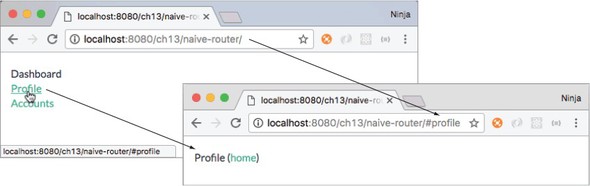

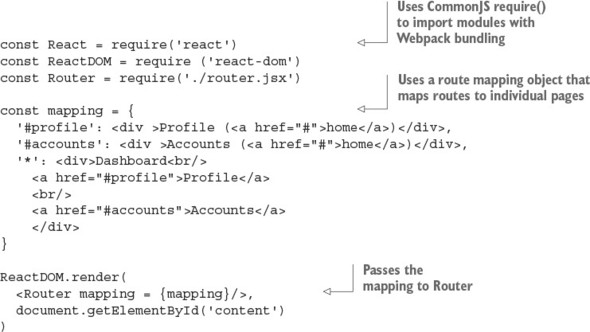

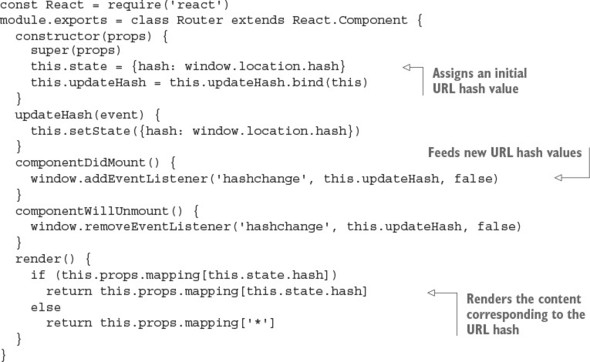

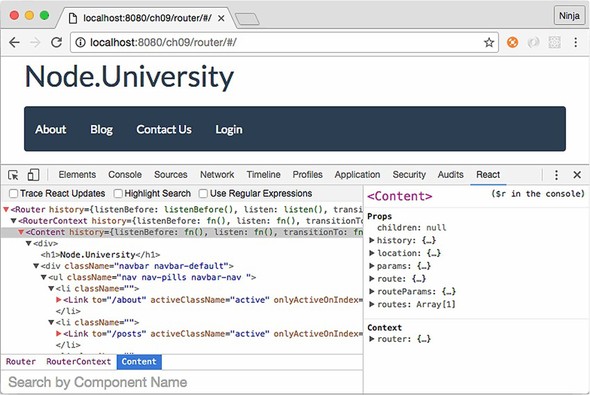

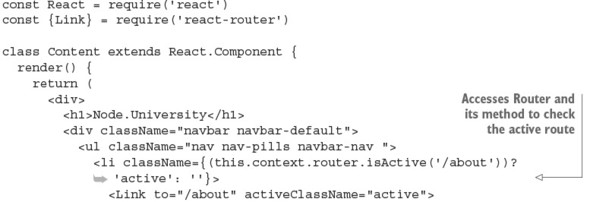

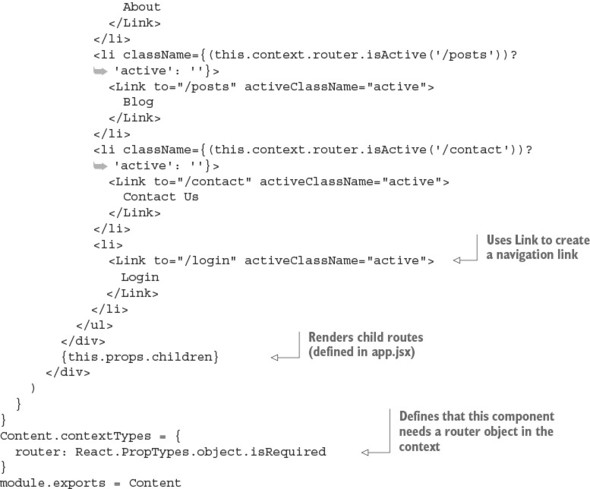

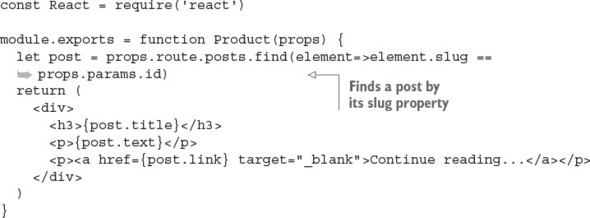

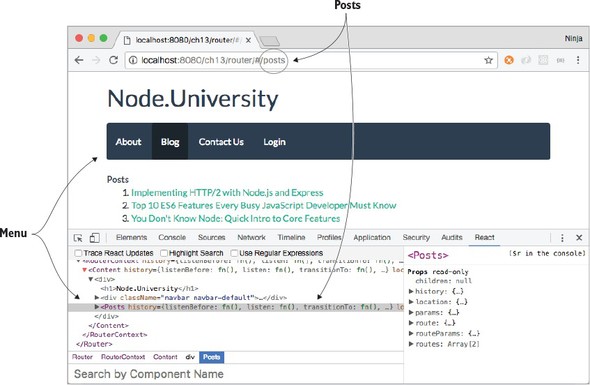

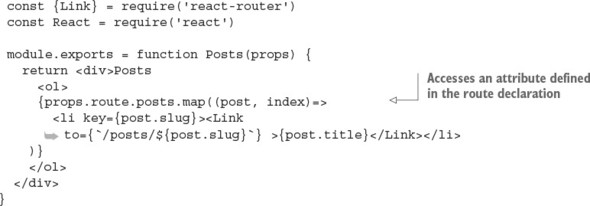

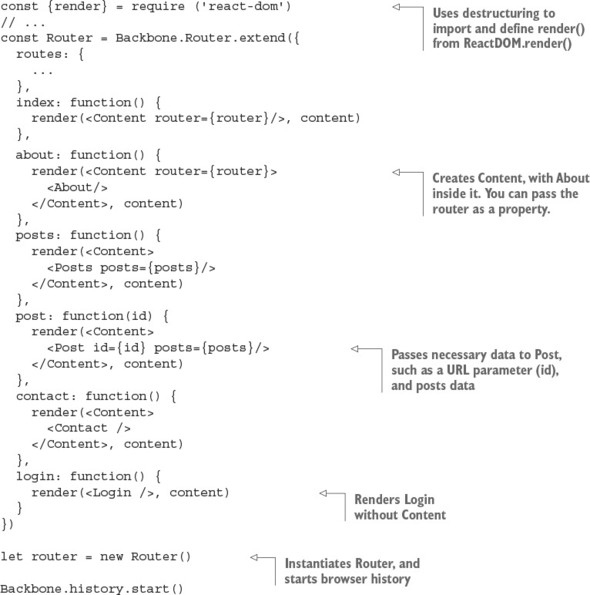

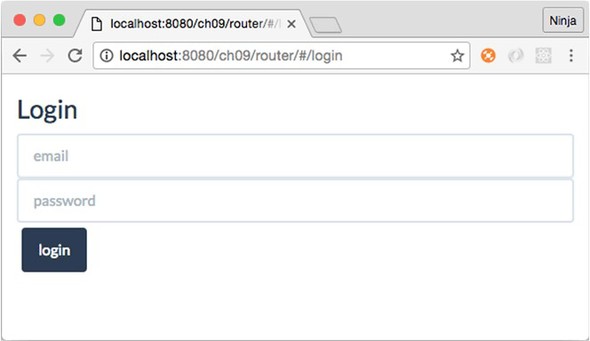

13.1. Implementing a router from scratch

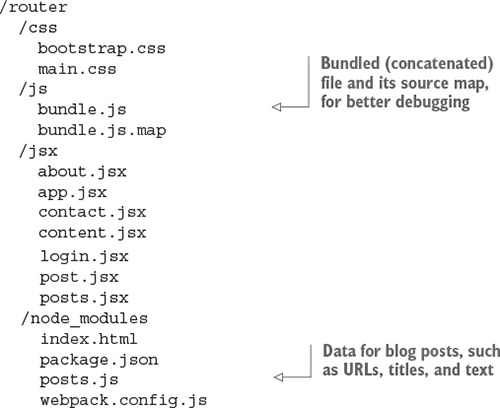

13.1.1. Setting up the project

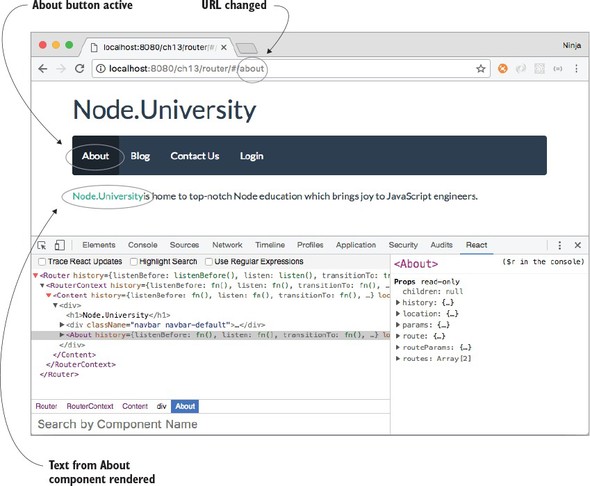

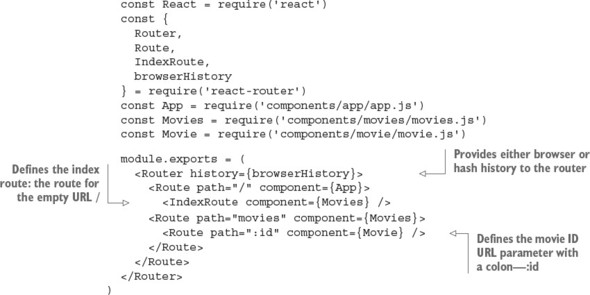

13.2.1. React Router’s JSX style

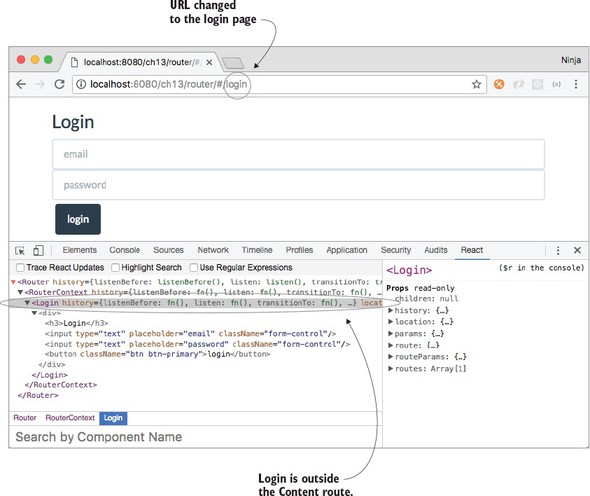

13.3.1. Accessing router with the withRouter higher-order component

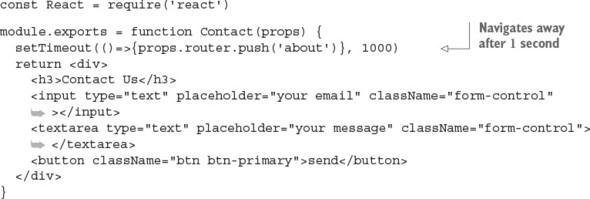

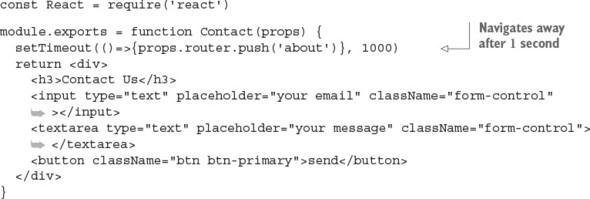

13.3.2. Navigating programmatically

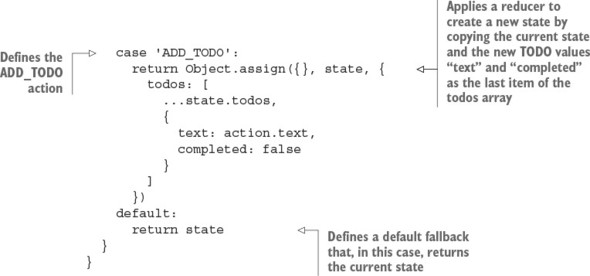

Chapter 14. Working with data using Redux

14.1. React support for unidirectional data flow

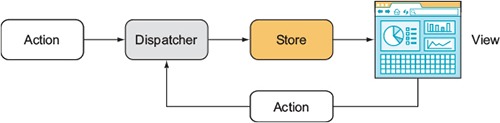

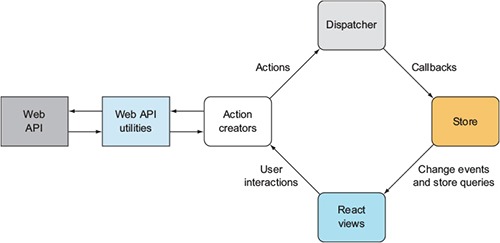

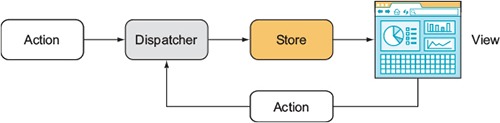

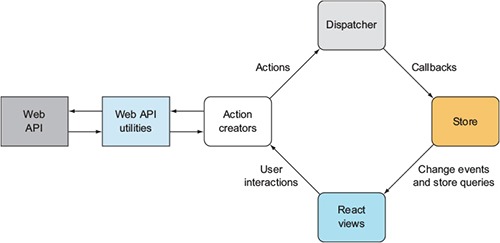

14.2. Understanding the Flux data architecture

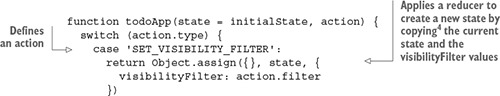

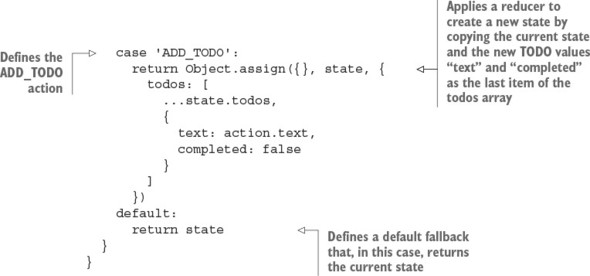

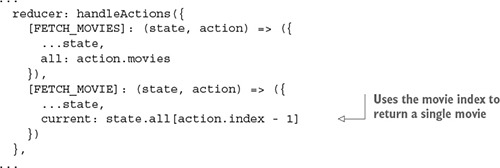

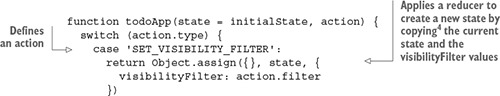

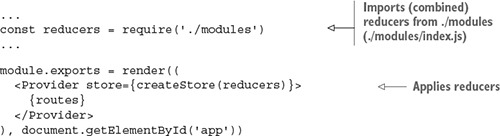

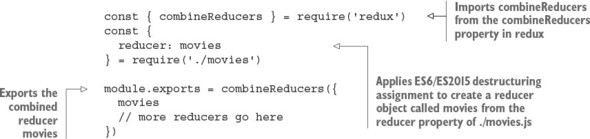

14.3. Using the Redux data library

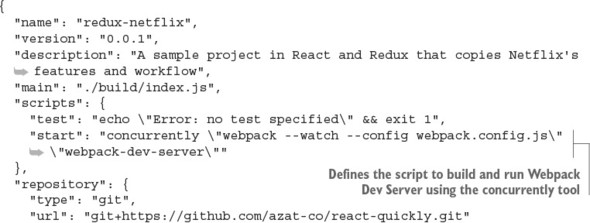

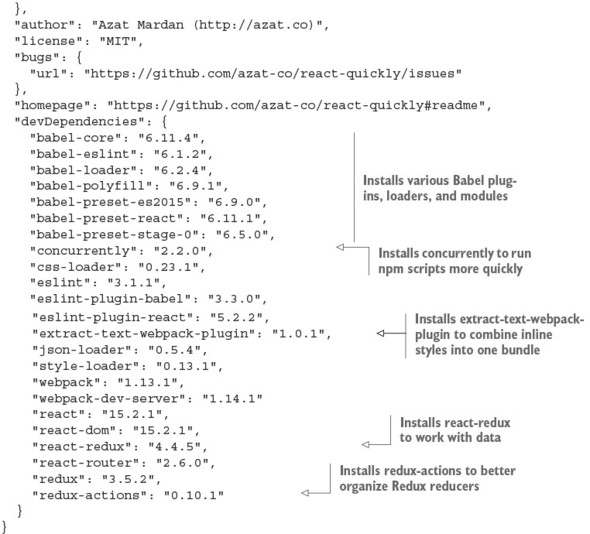

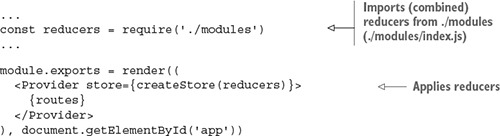

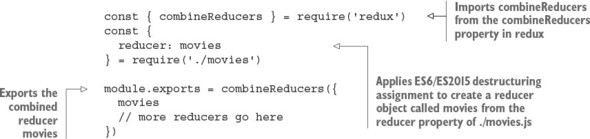

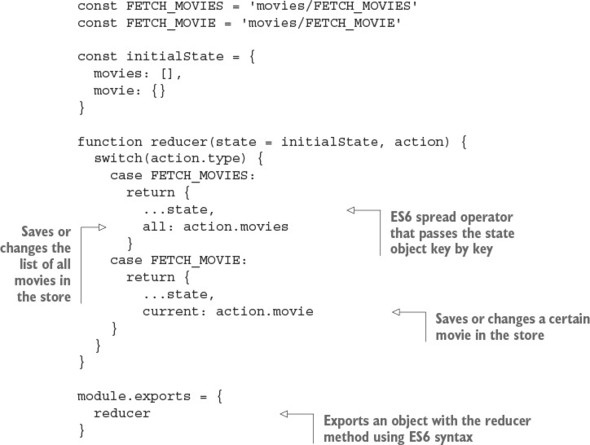

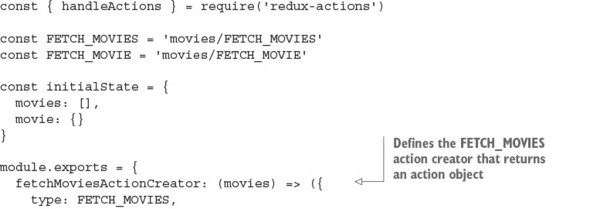

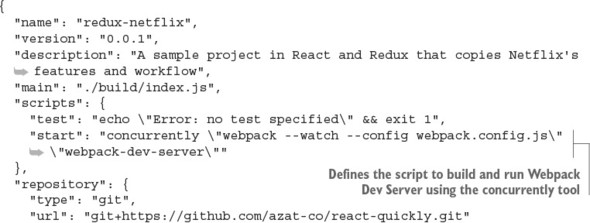

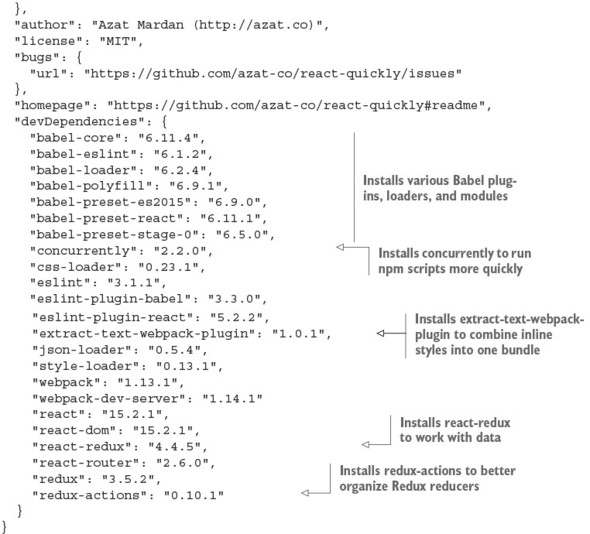

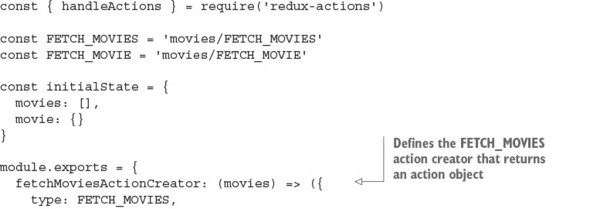

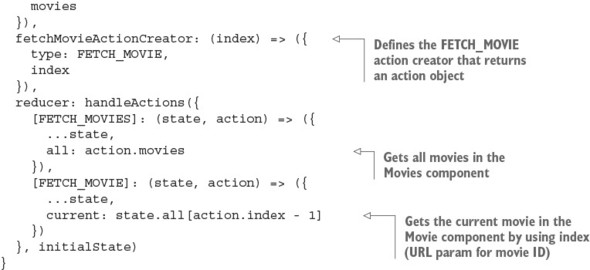

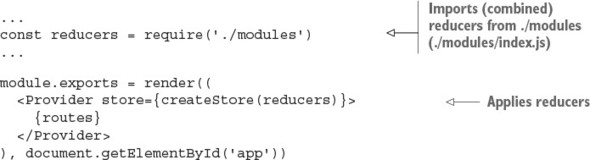

14.3.2. Dependencies and configs

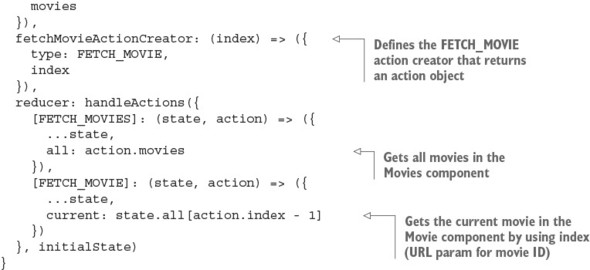

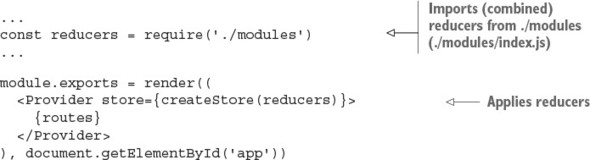

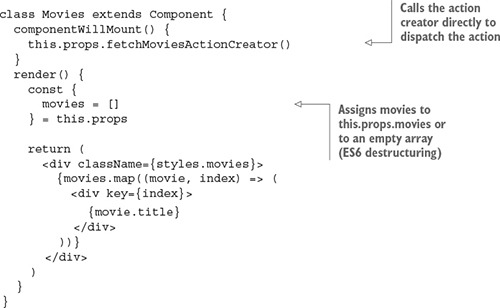

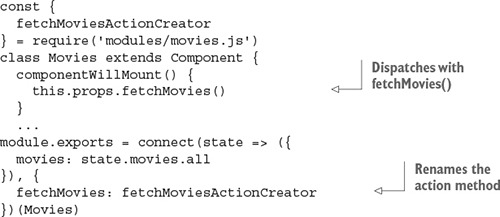

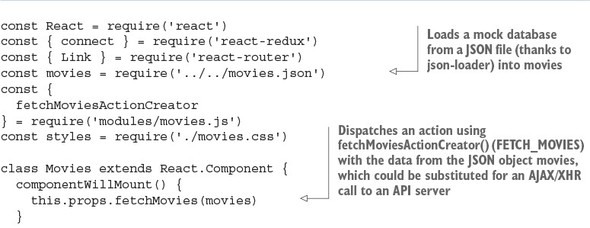

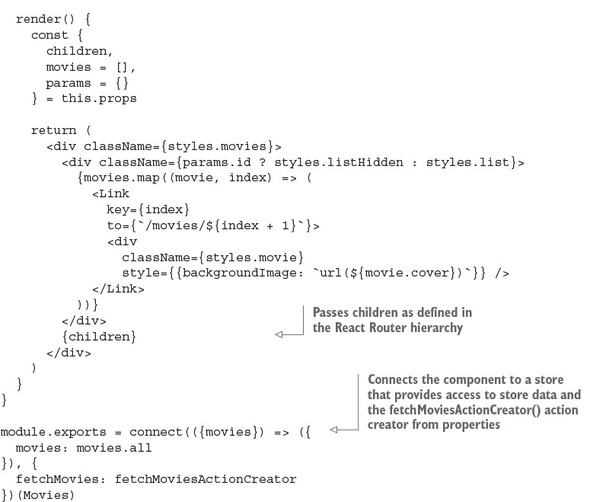

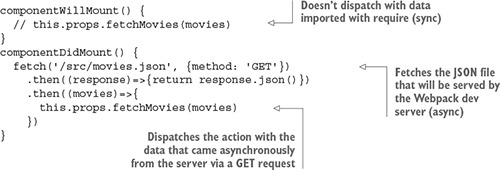

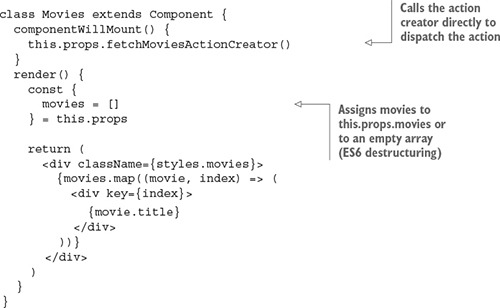

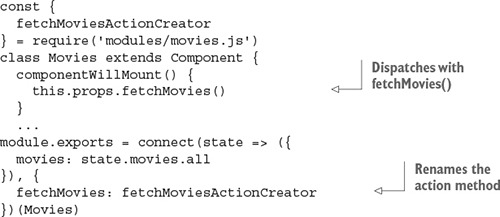

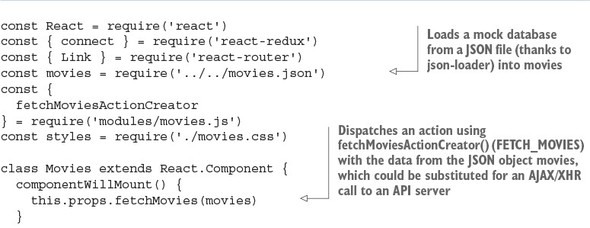

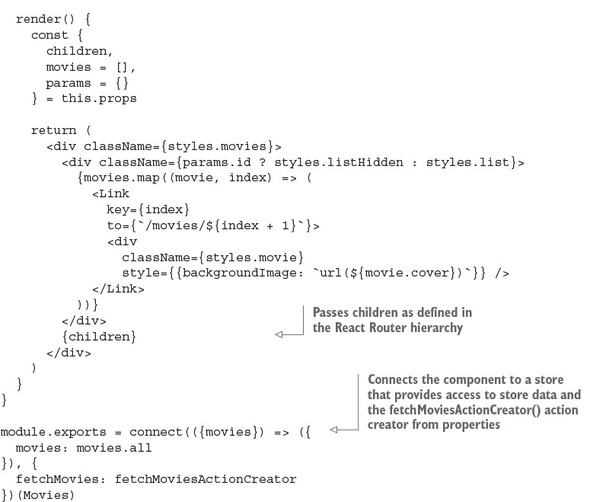

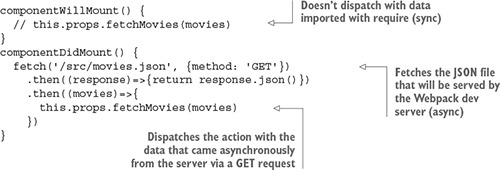

14.3.9. Connecting components to the store

14.3.10. Dispatching an action

14.3.11. Passing action creators into component properties

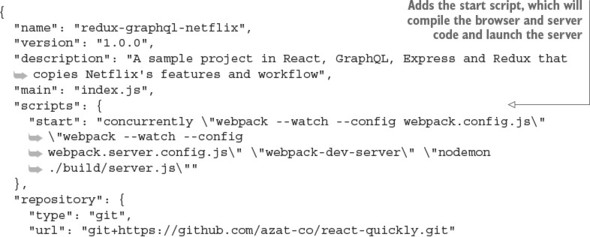

Chapter 15. Working with data using GraphQL

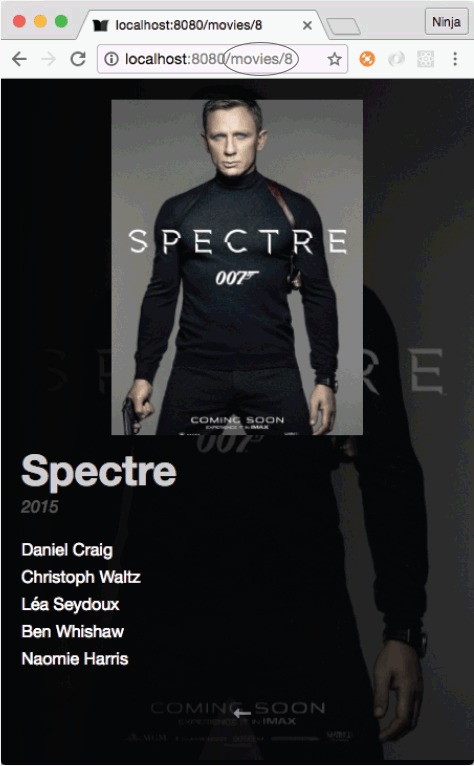

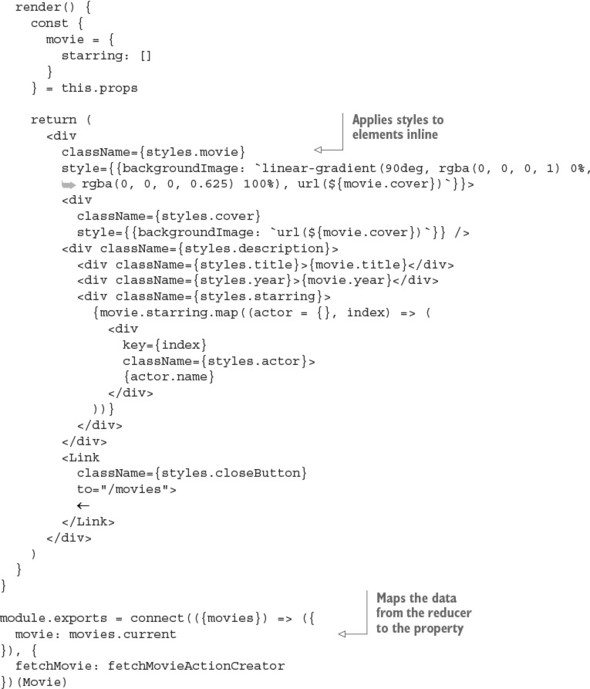

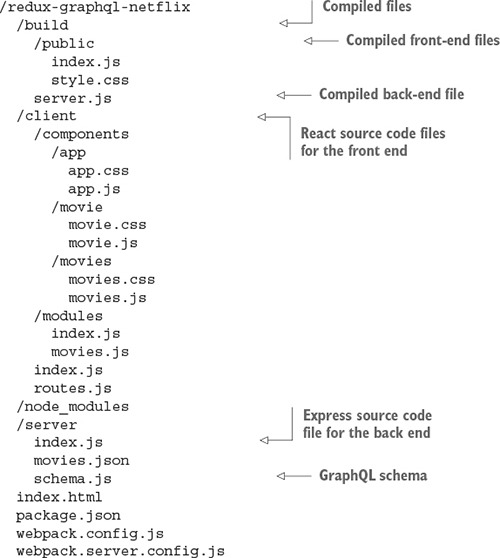

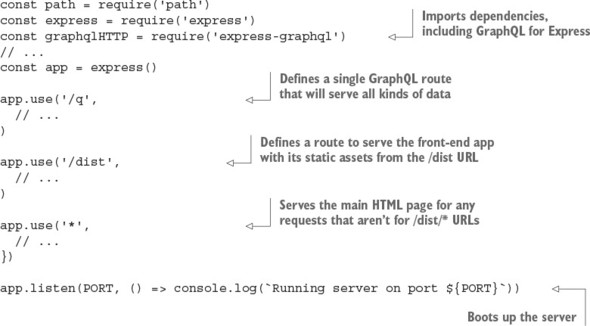

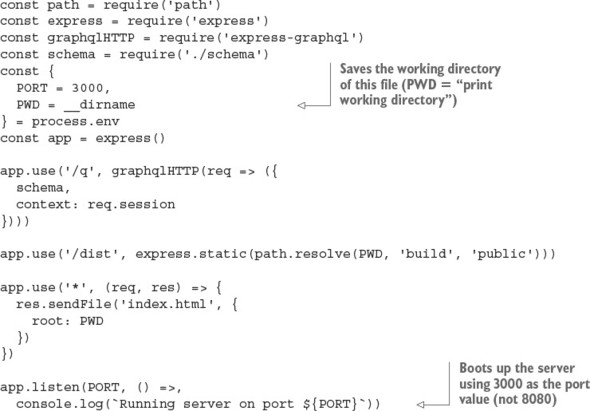

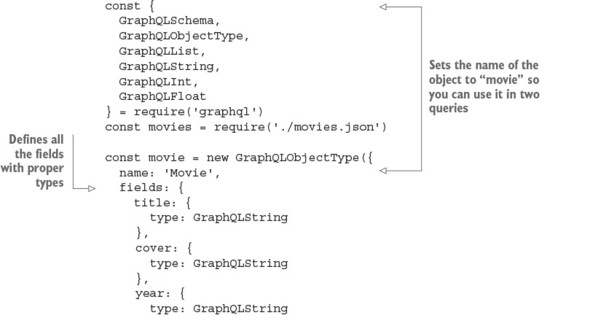

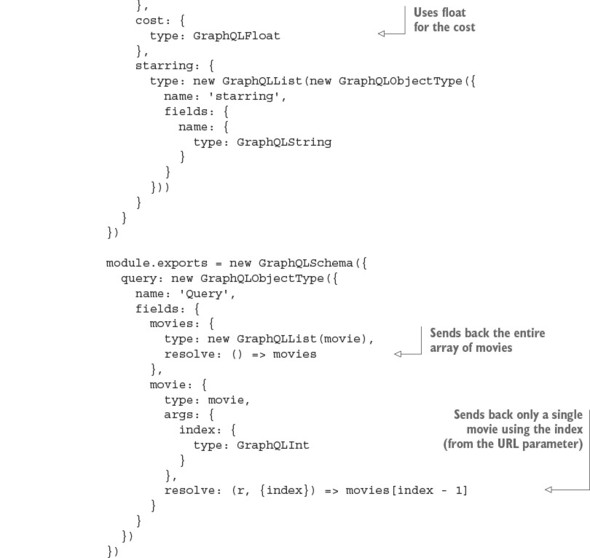

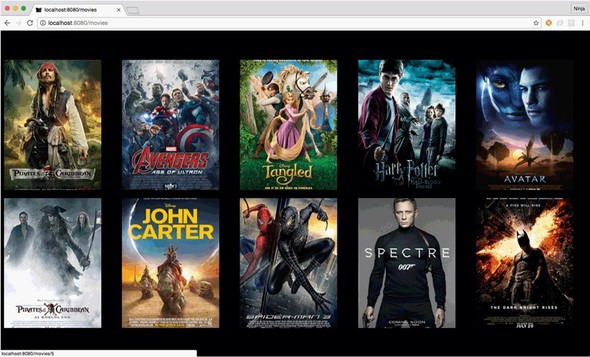

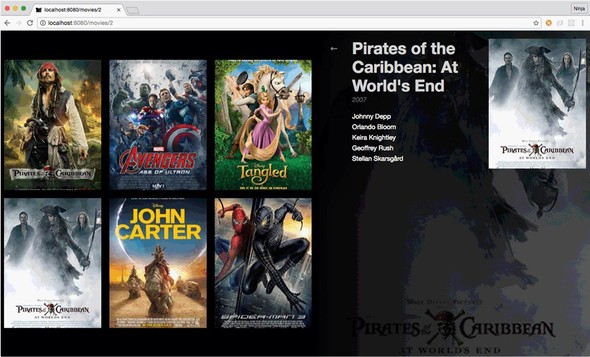

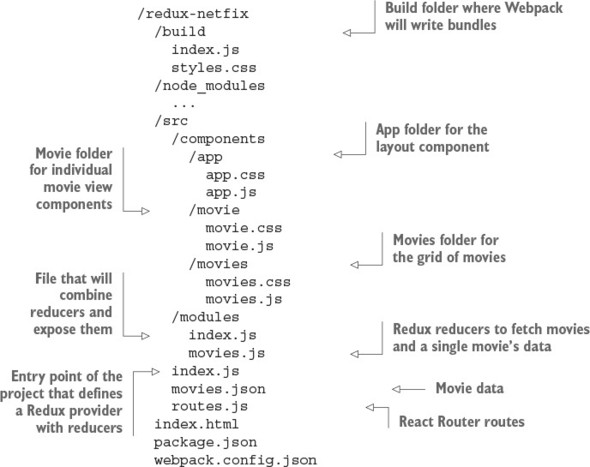

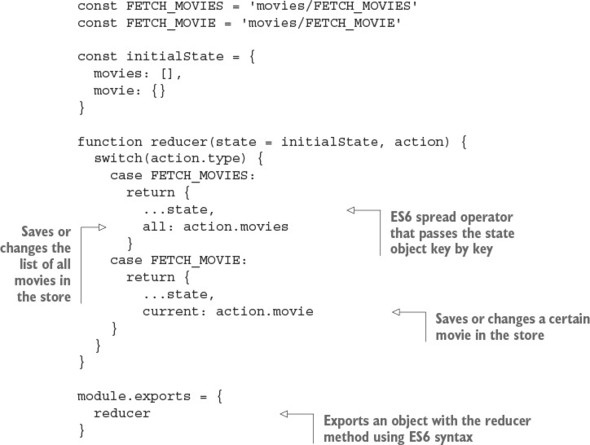

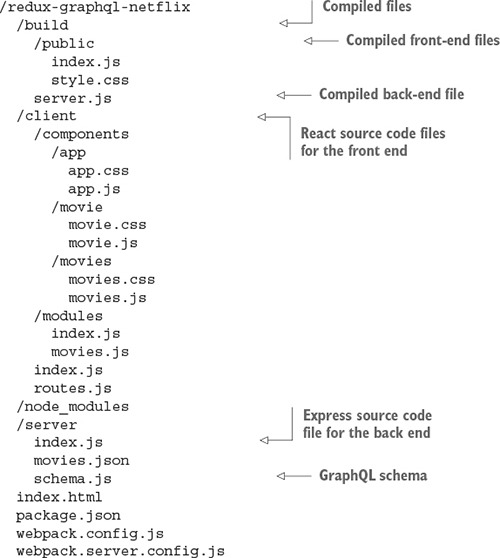

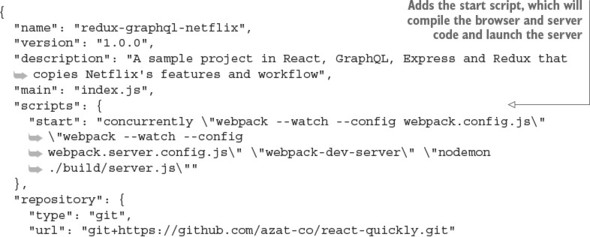

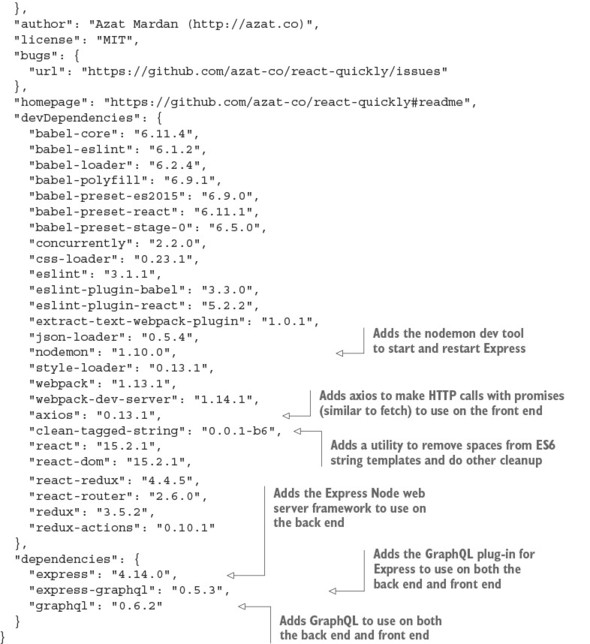

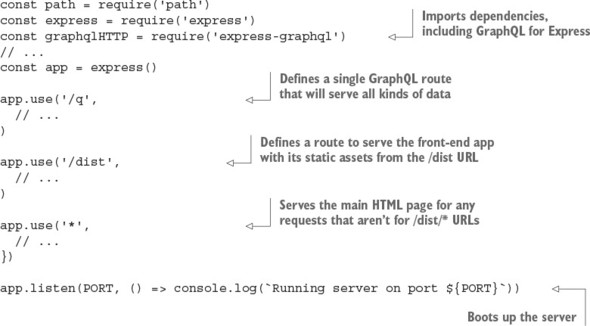

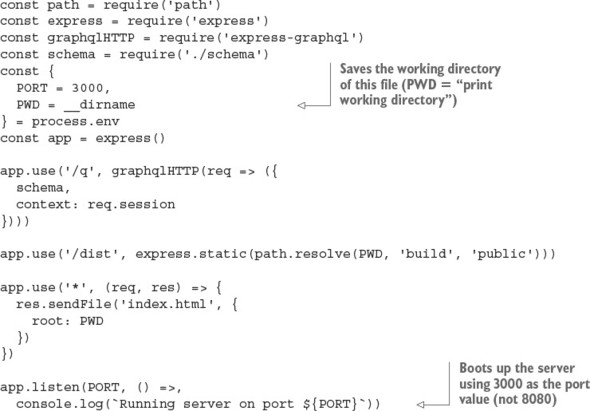

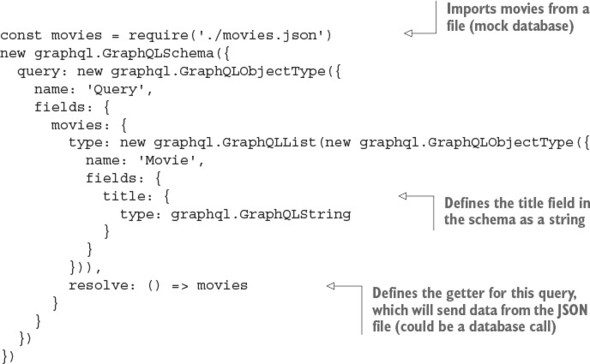

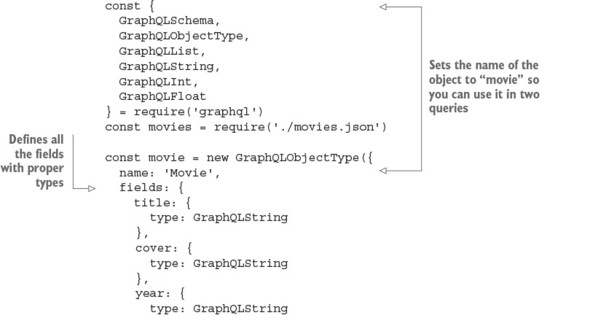

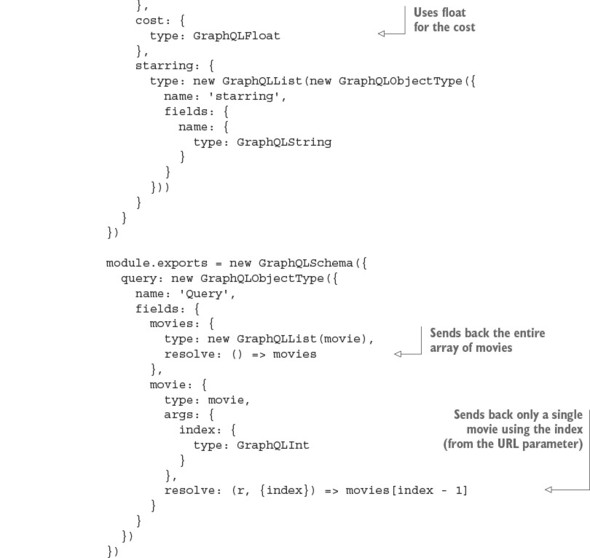

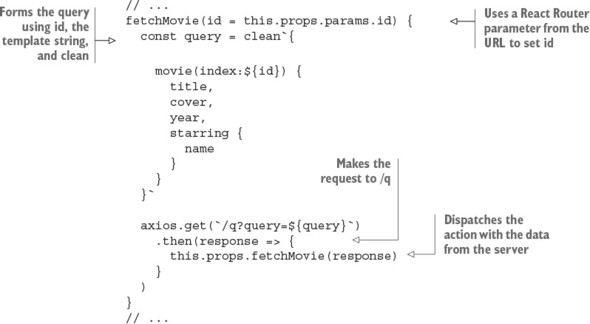

15.2. Adding a server to the Netflix clone

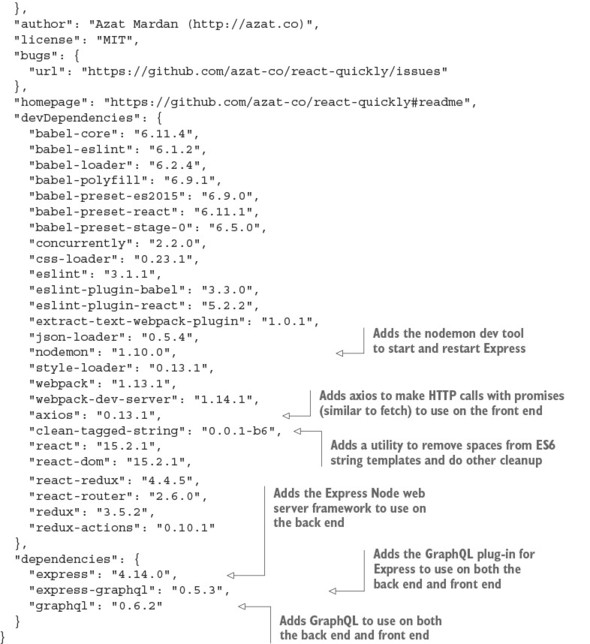

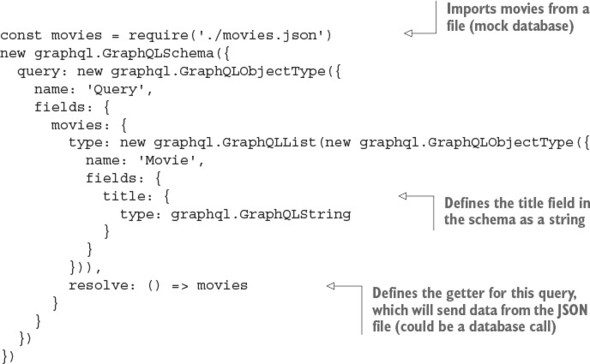

15.2.1. Installing GraphQL on a server

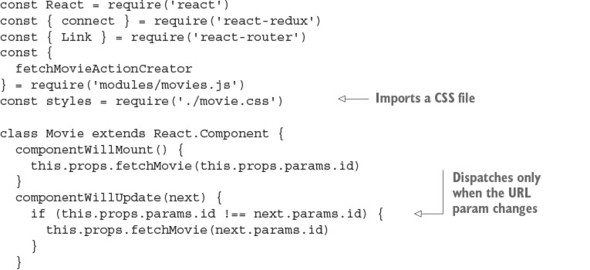

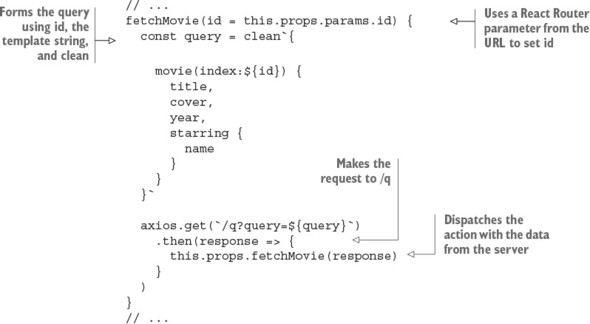

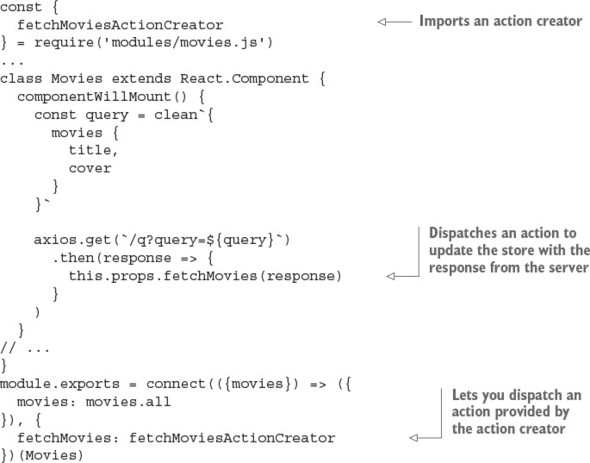

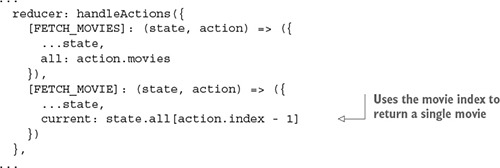

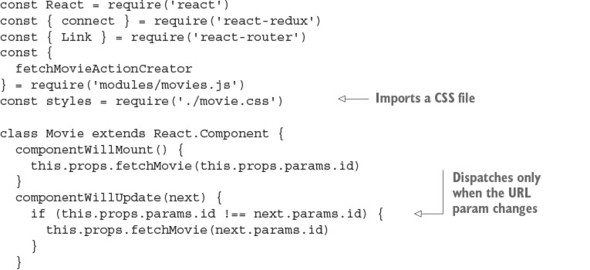

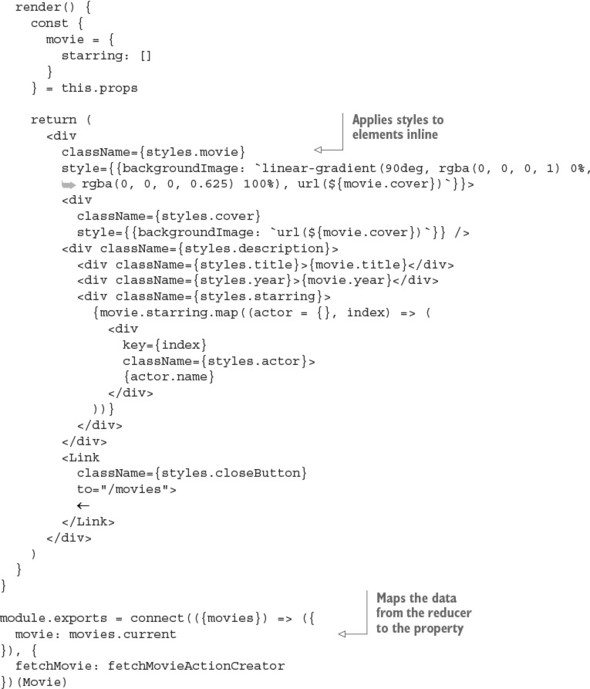

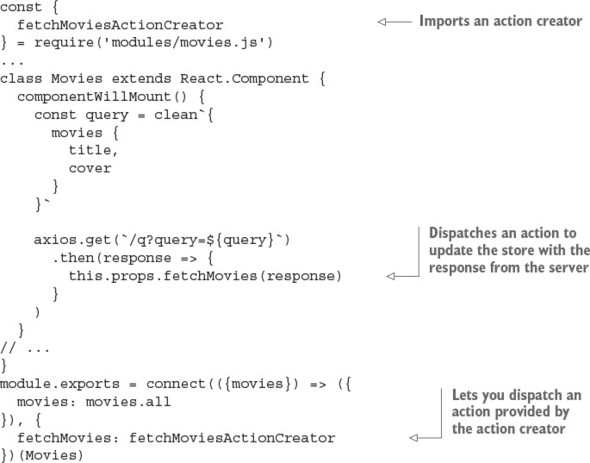

15.2.4. Querying the API and saving the response into the store

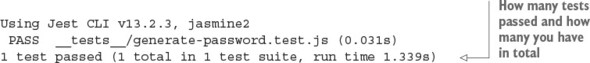

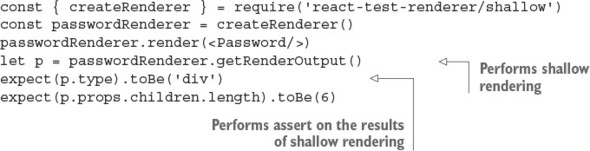

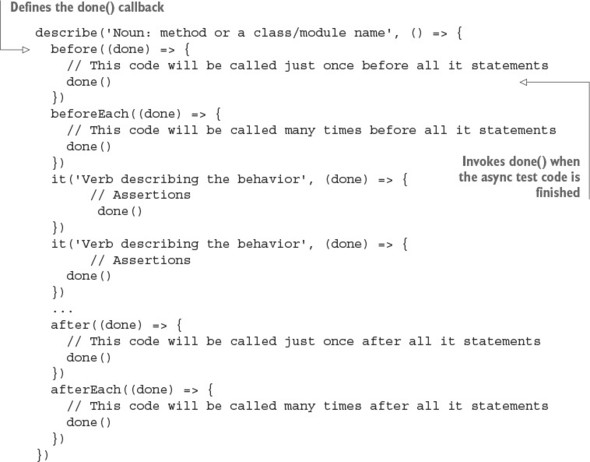

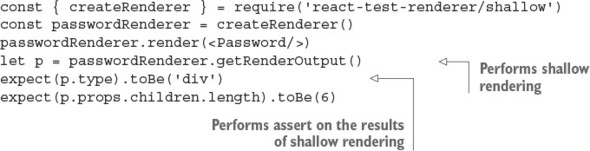

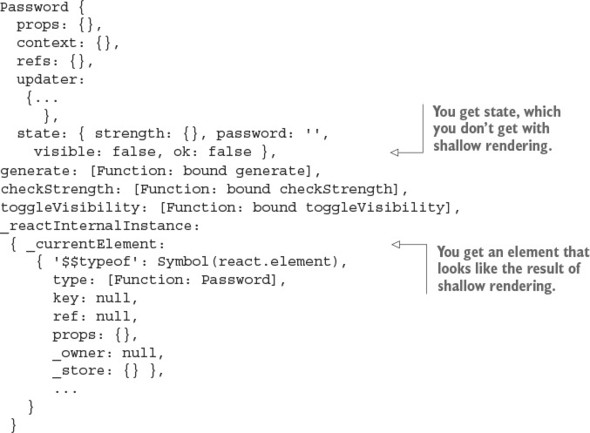

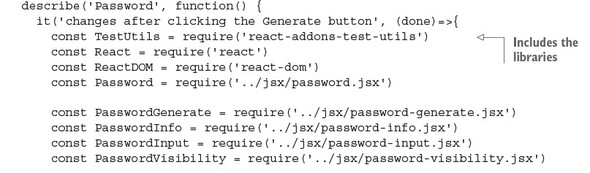

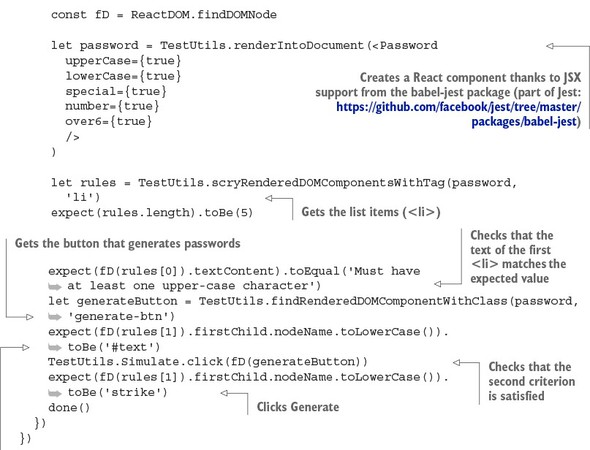

Chapter 16. Unit testing React with Jest

16.2. Why Jest (vs. Mocha or others)?

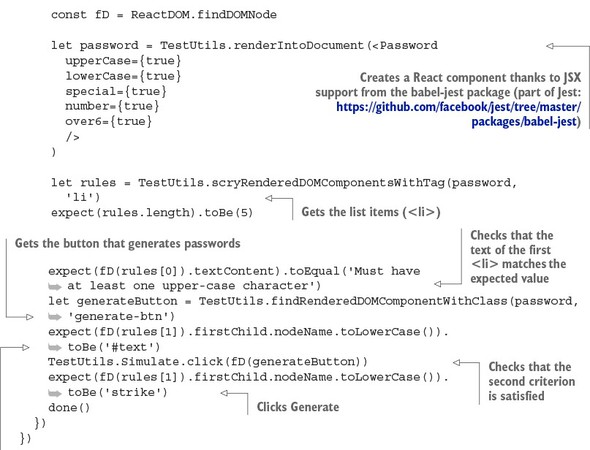

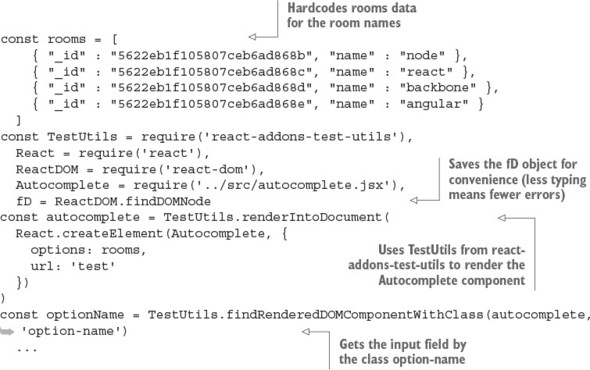

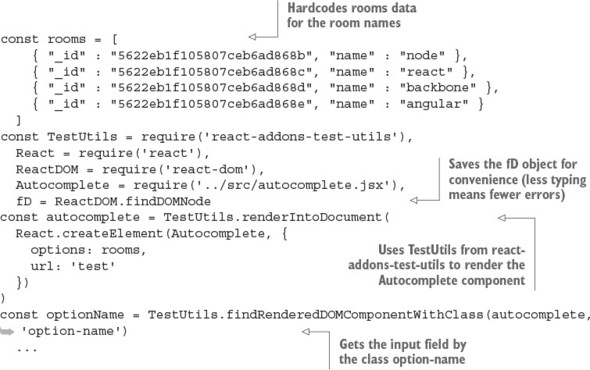

16.4. UI testing React with Jest and TestUtils

16.4.1. Finding elements with TestUtils

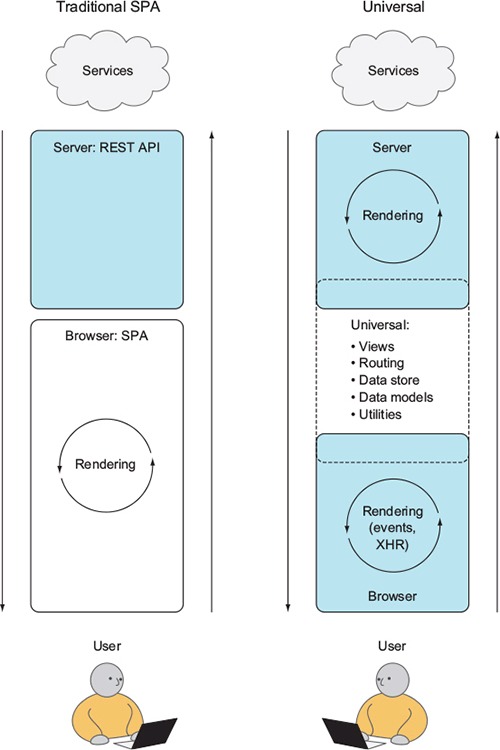

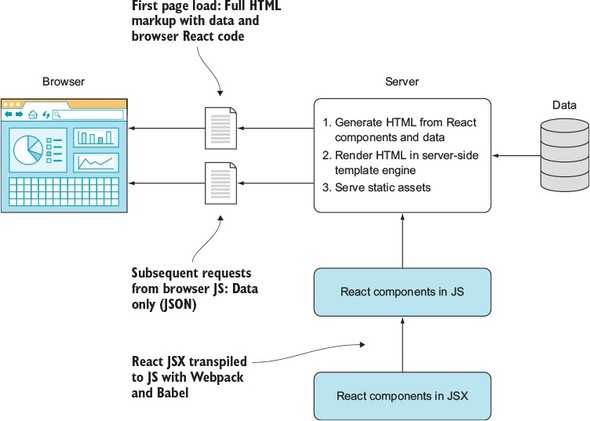

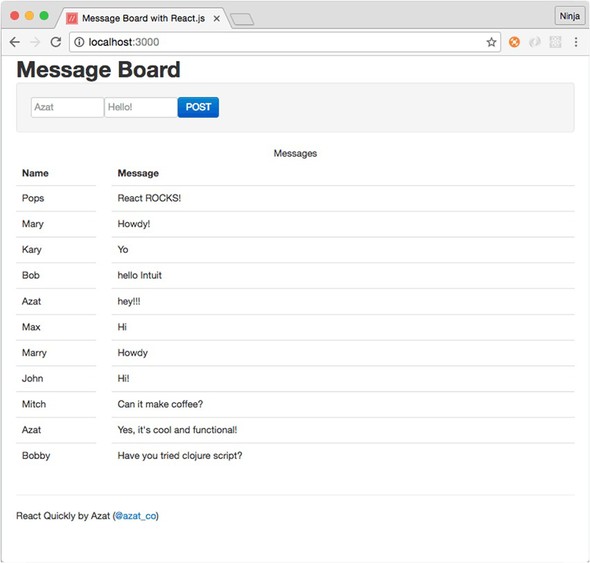

Chapter 17. React on Node and Universal JavaScript

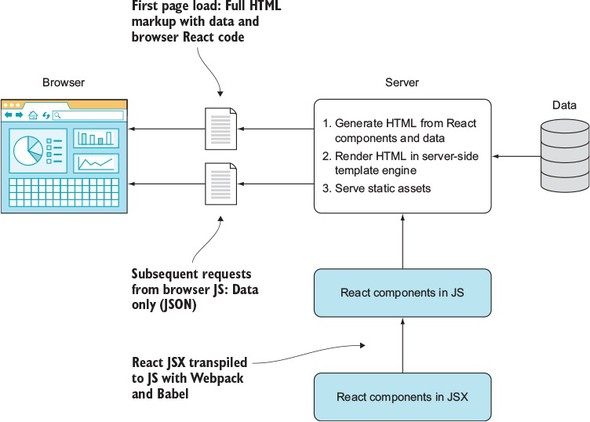

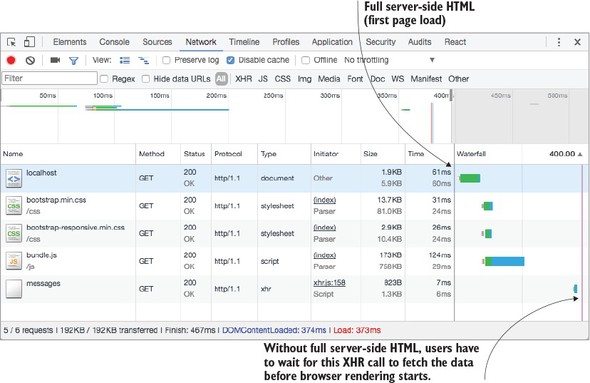

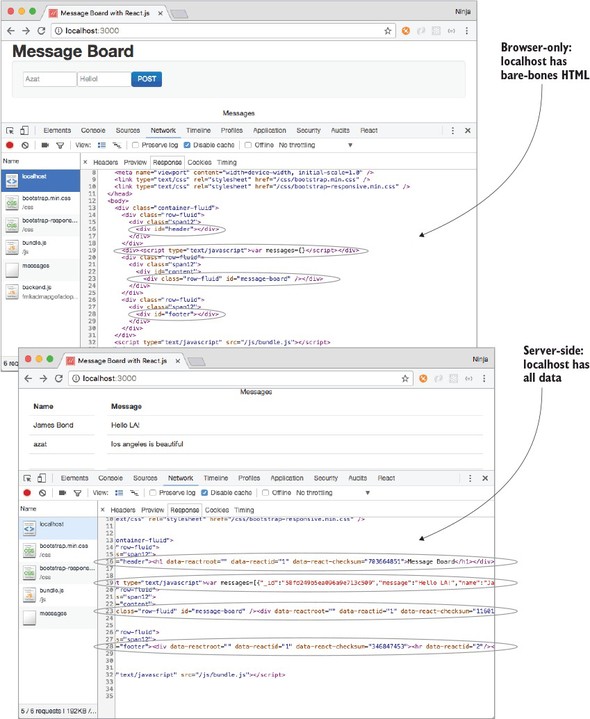

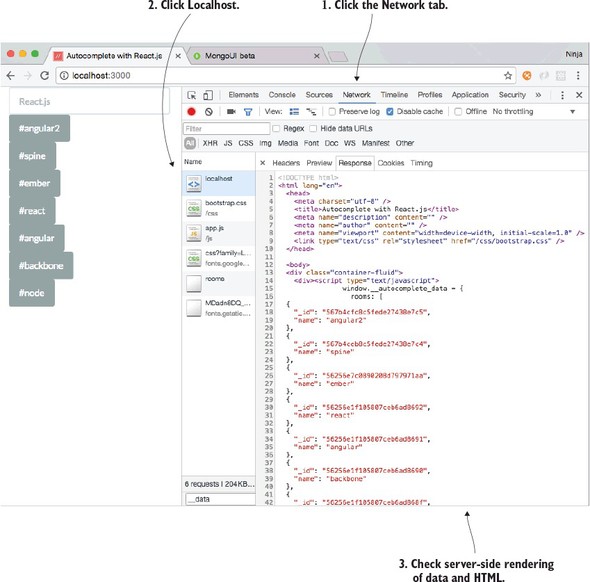

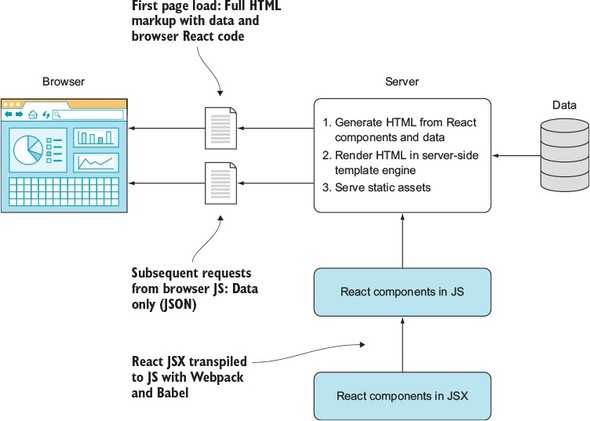

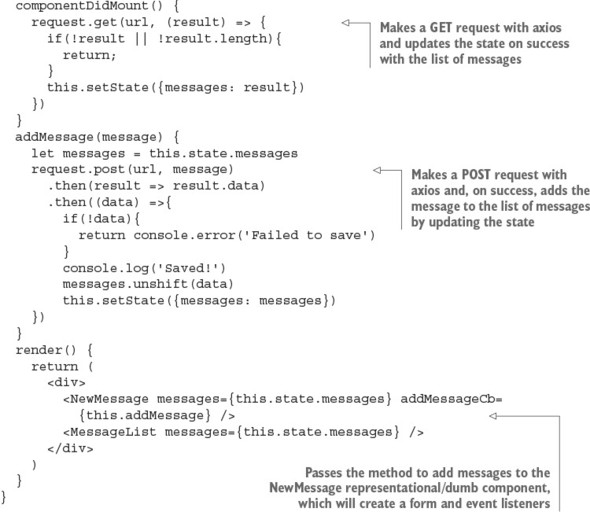

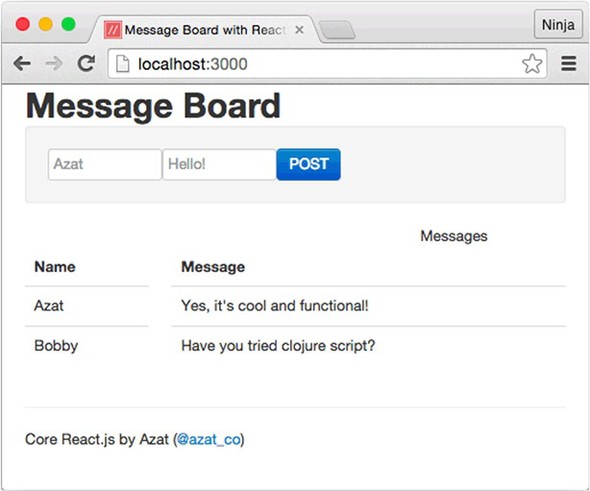

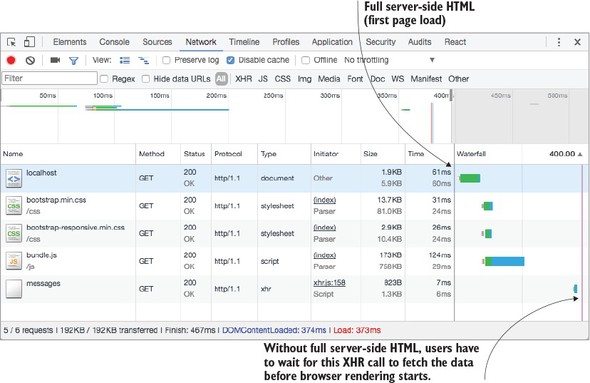

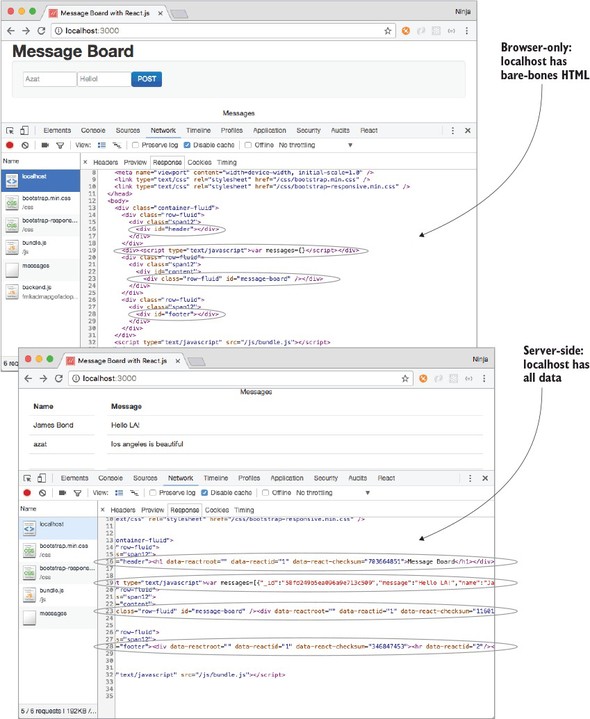

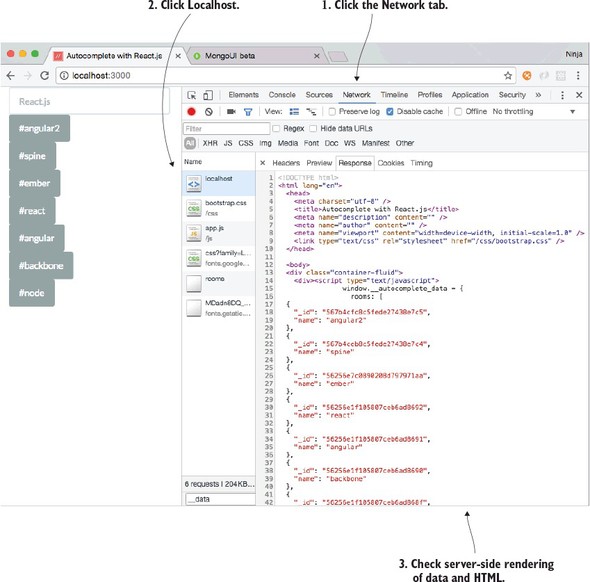

17.1. Why React on the server? And what is Universal JavaScript?

17.1.2. Better performance with faster loading times

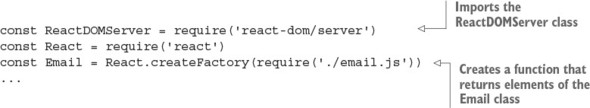

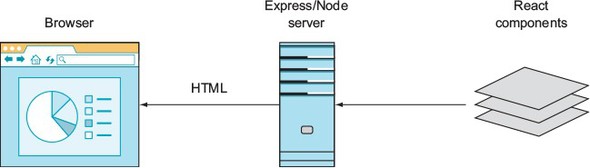

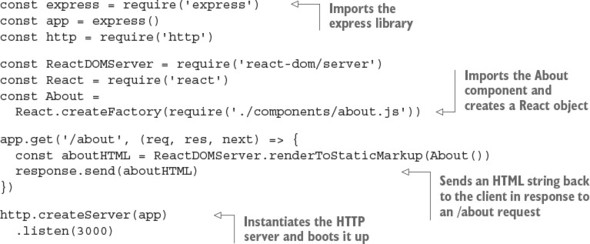

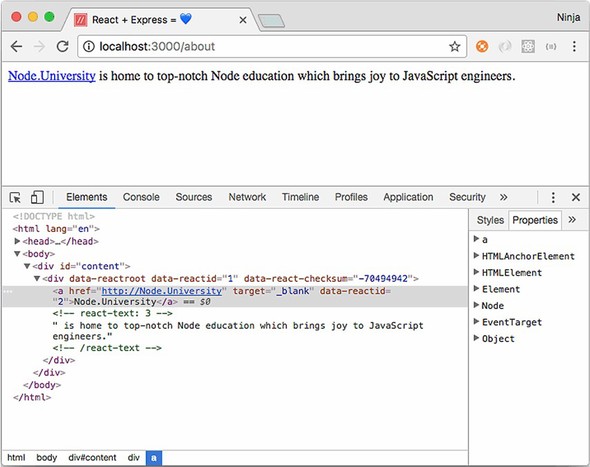

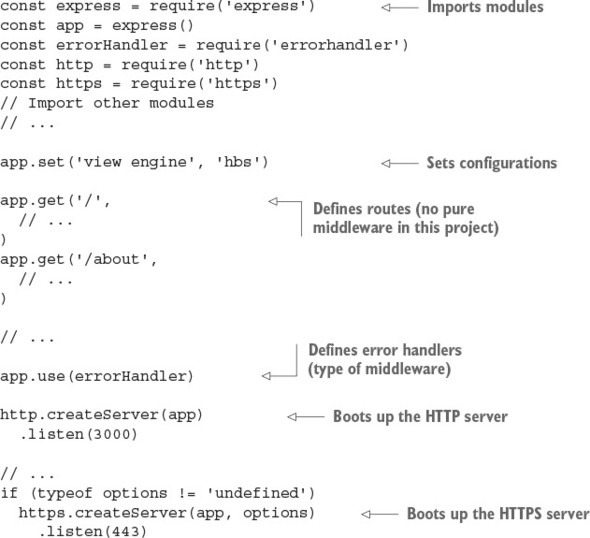

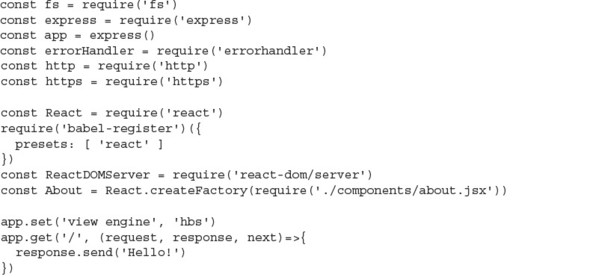

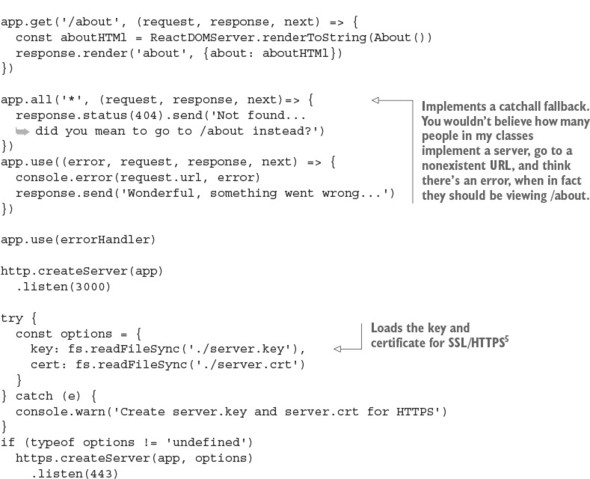

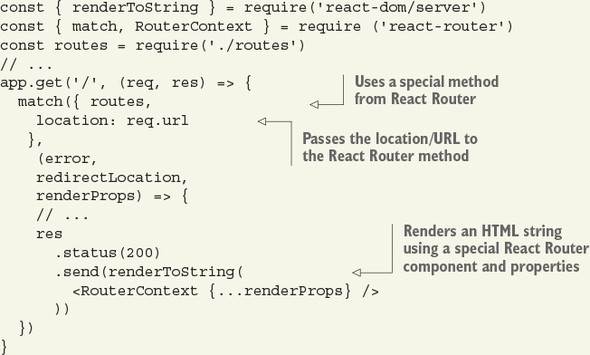

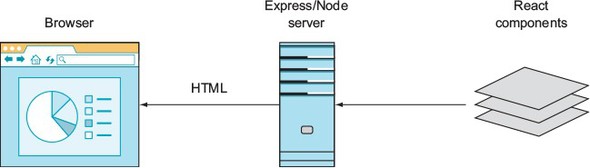

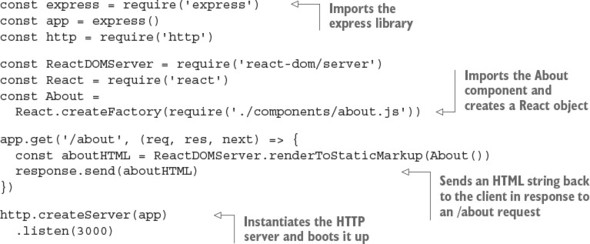

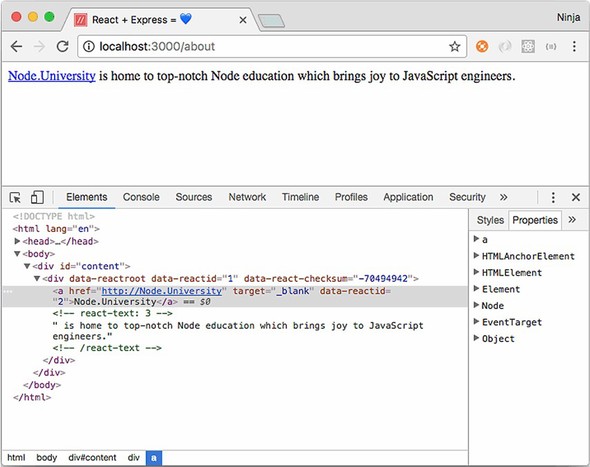

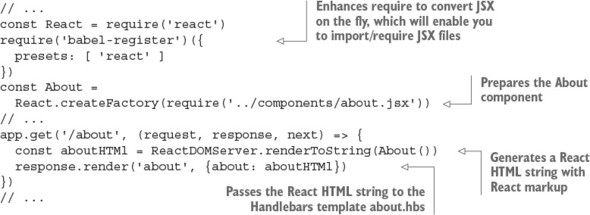

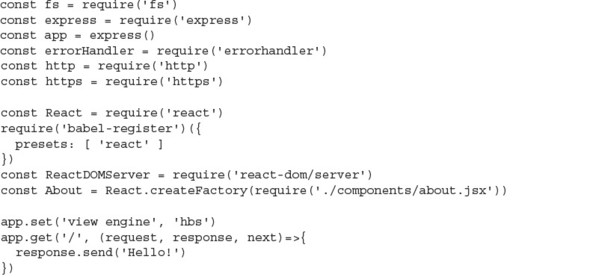

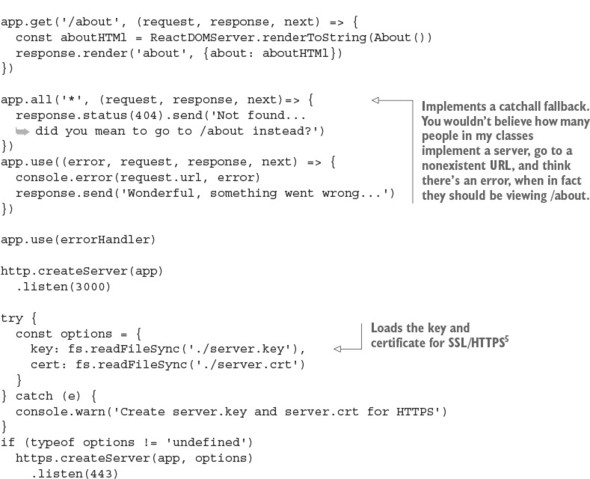

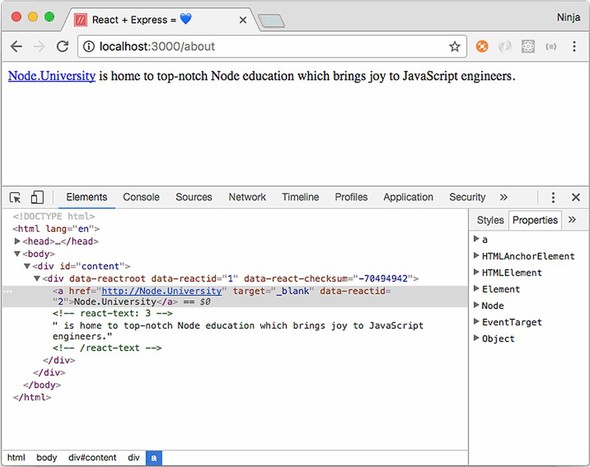

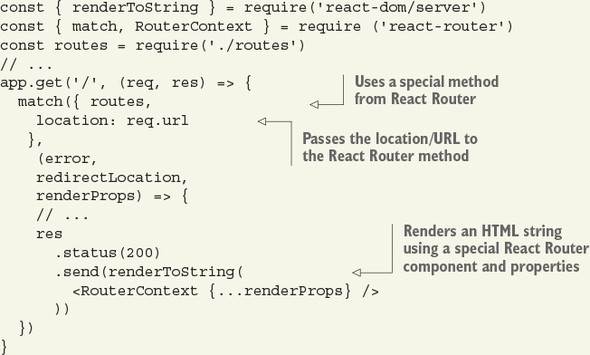

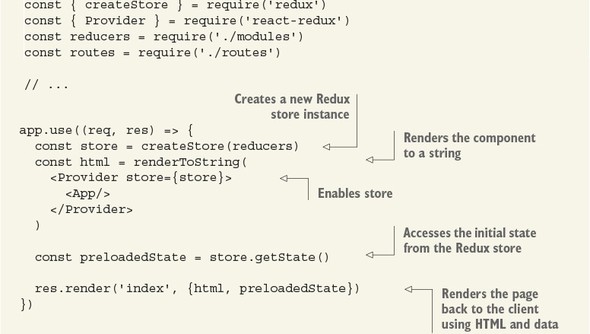

17.3. React and Express: rendering on the server side from components

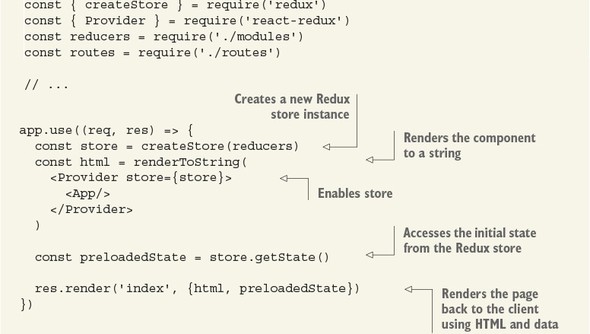

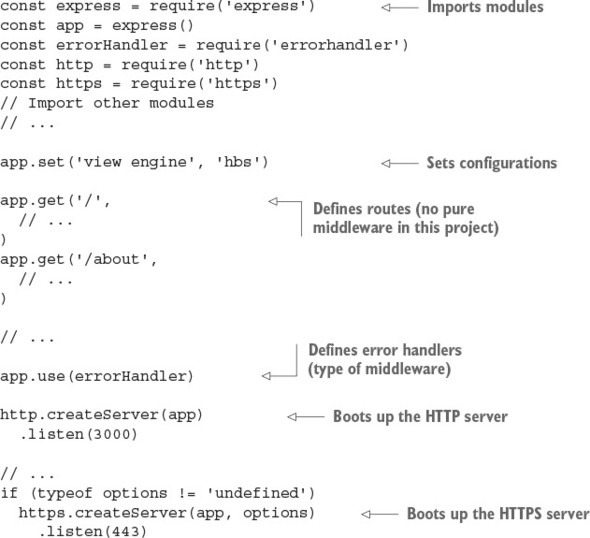

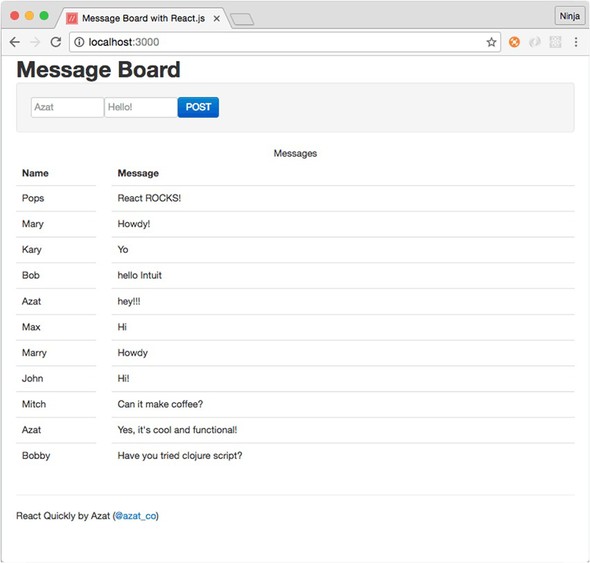

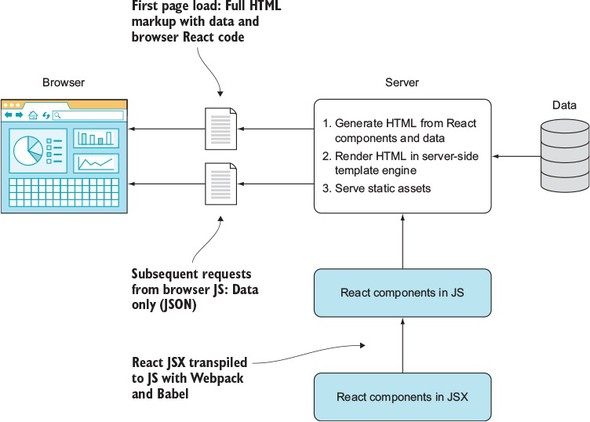

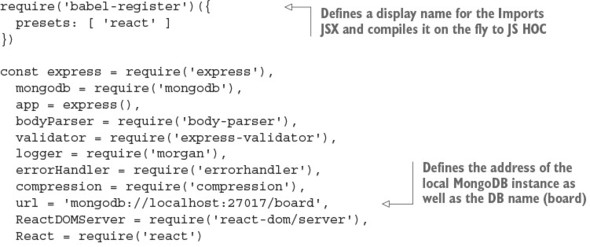

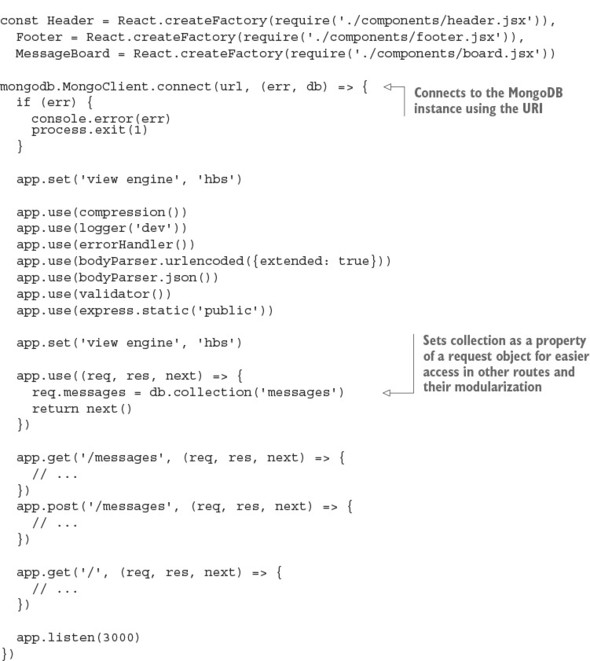

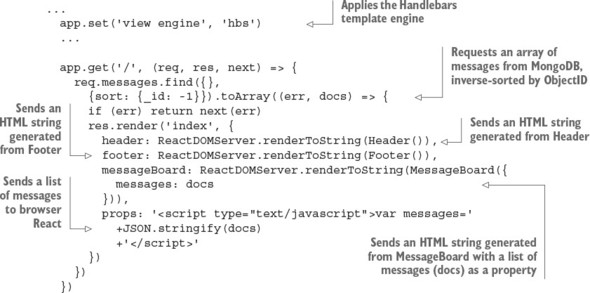

17.4. Universal JavaScript with Express and React

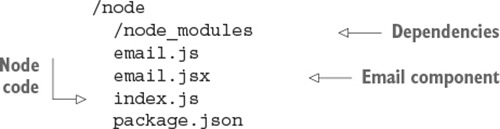

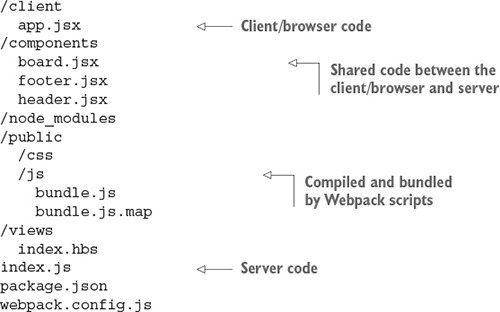

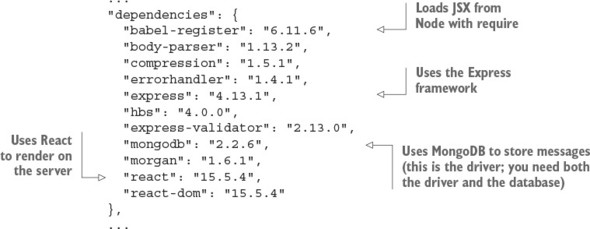

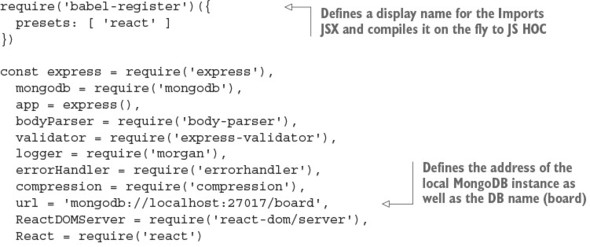

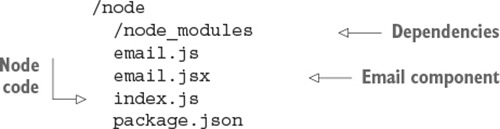

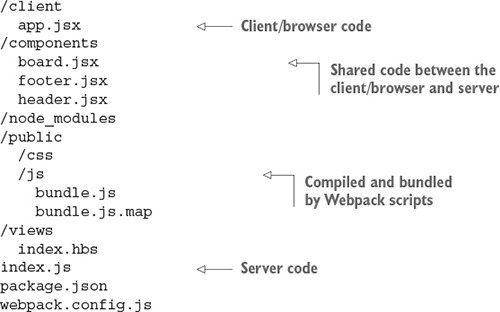

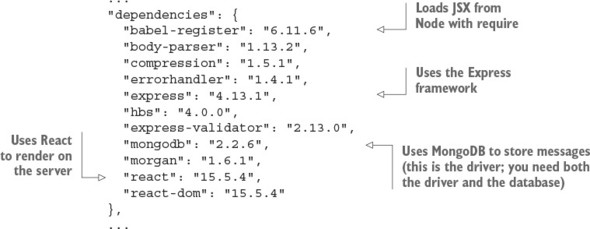

17.4.1. Project structure and configuration

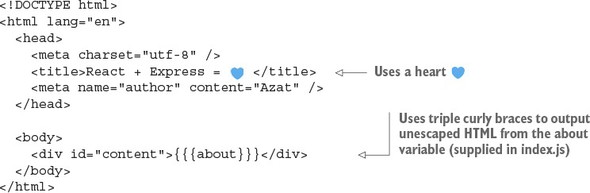

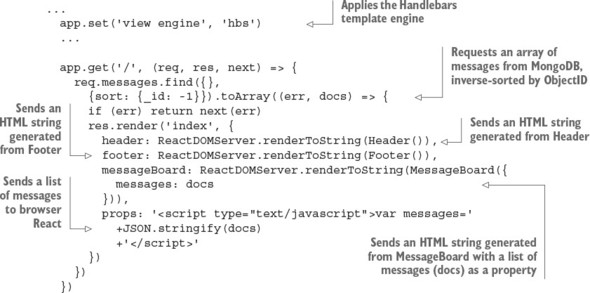

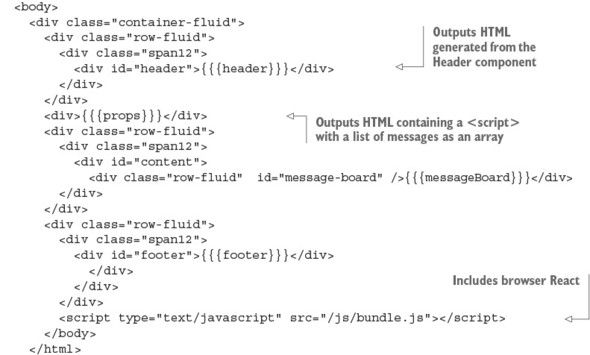

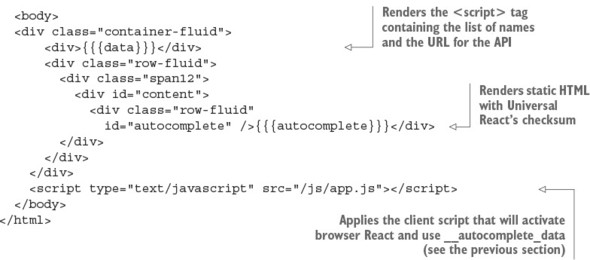

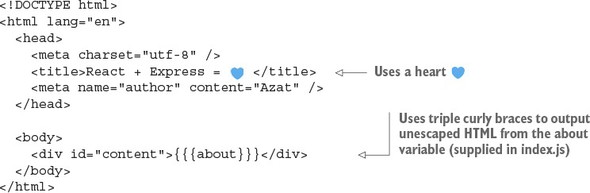

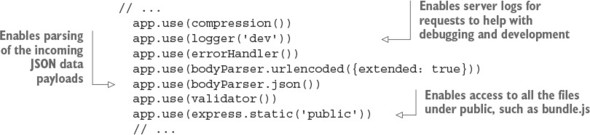

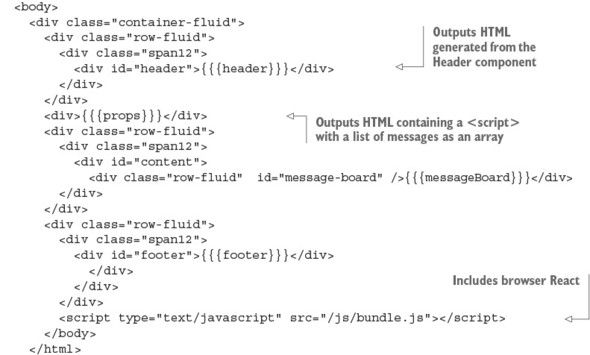

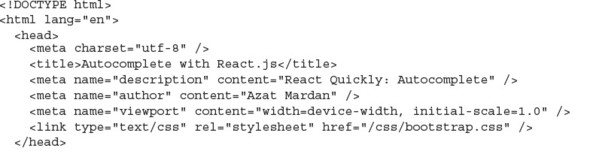

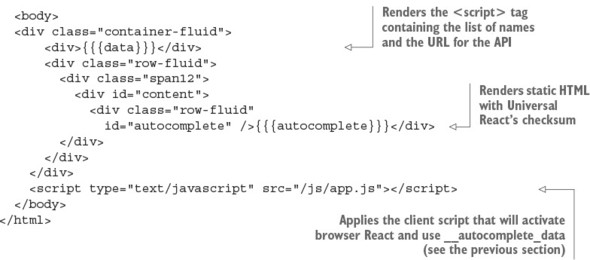

17.4.3. Server-side layout templates with Handlebars

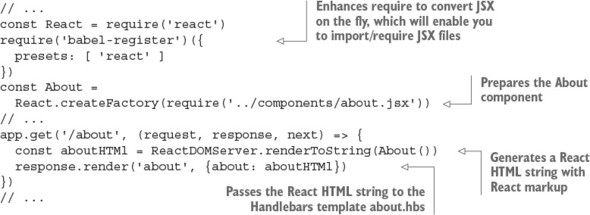

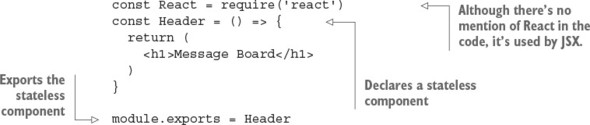

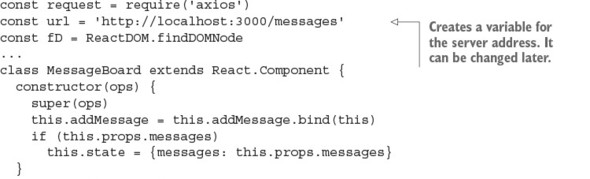

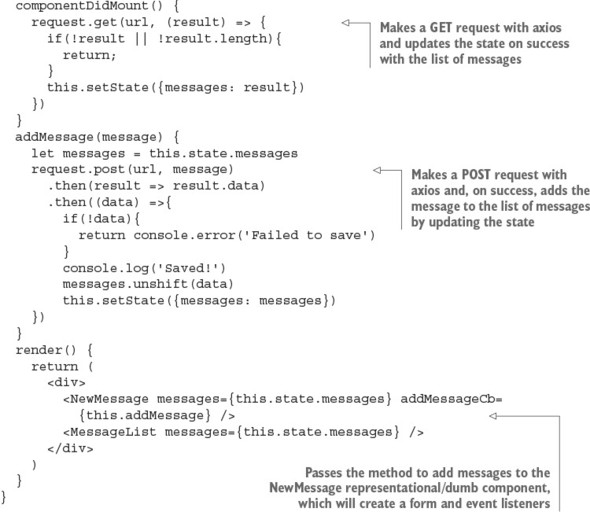

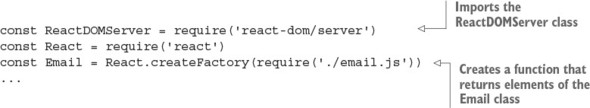

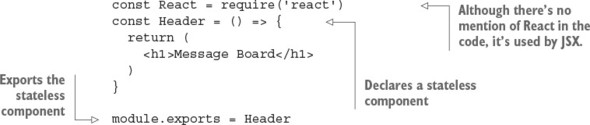

17.4.4. Composing React components on the server

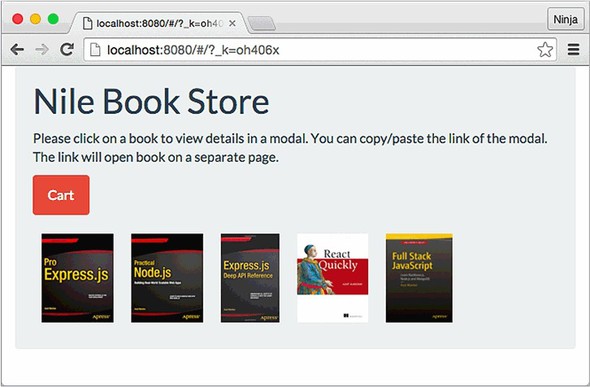

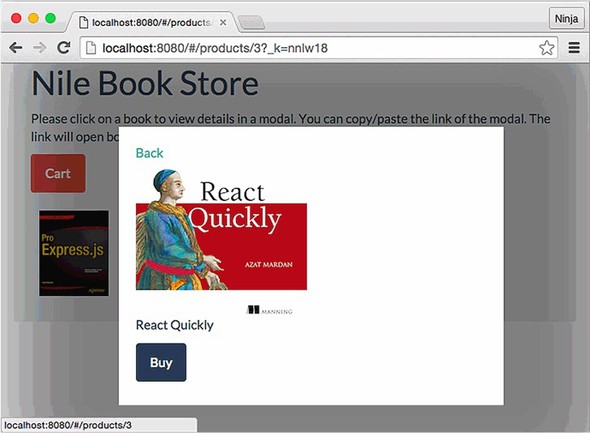

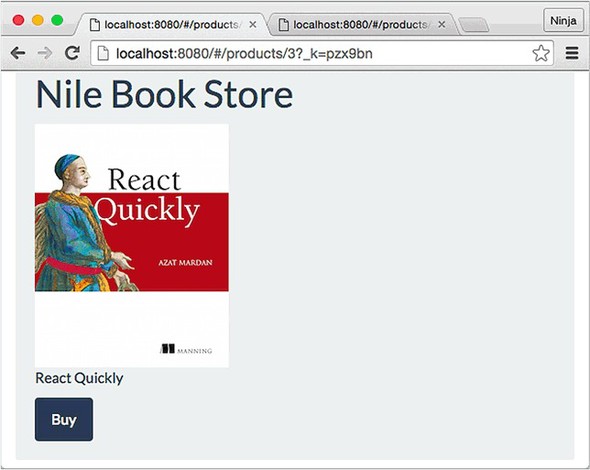

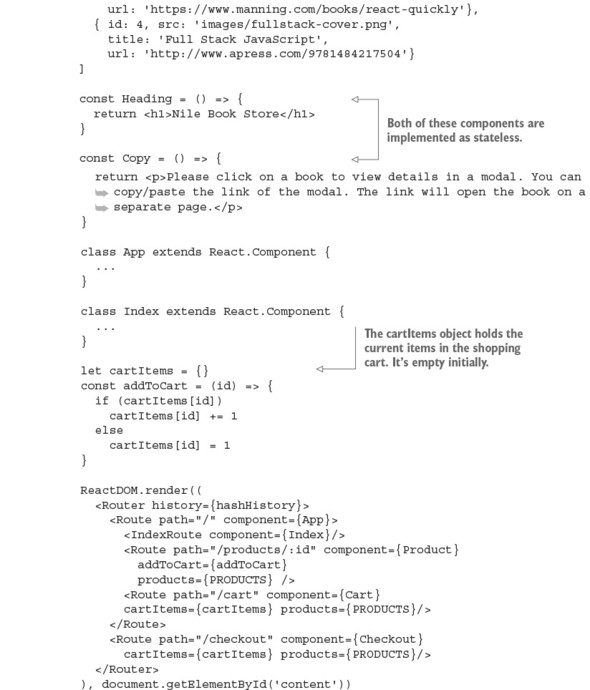

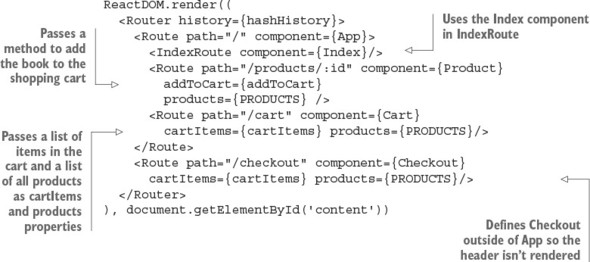

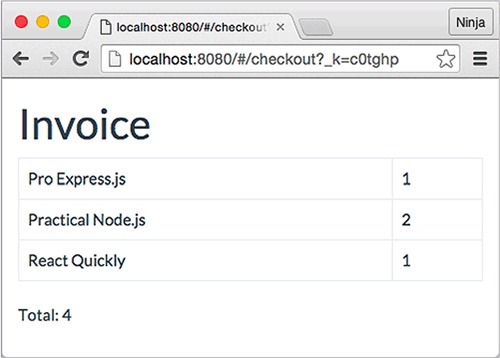

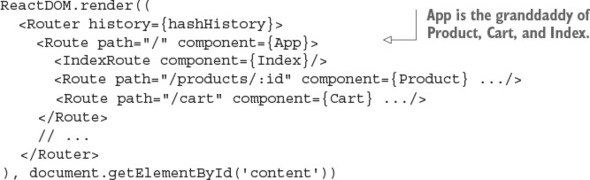

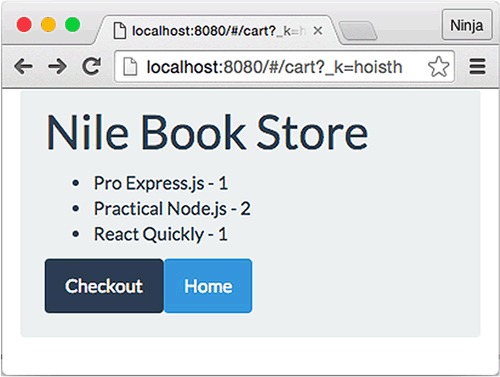

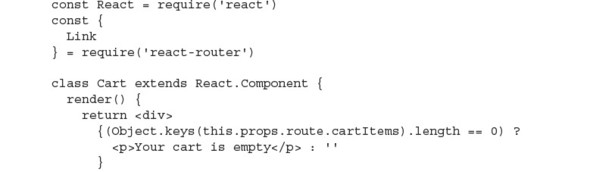

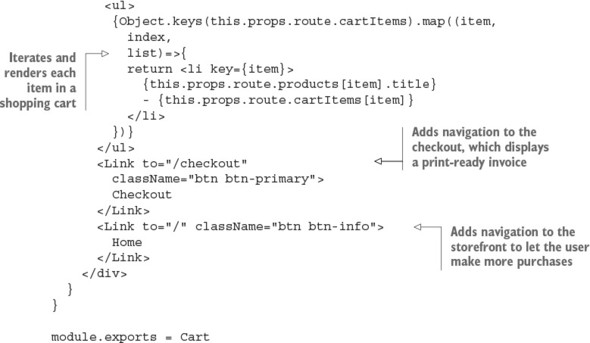

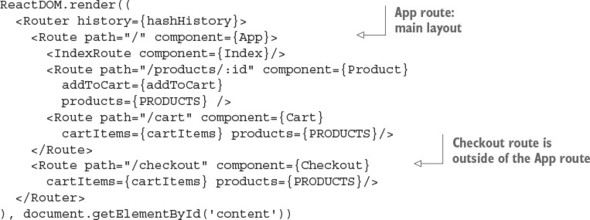

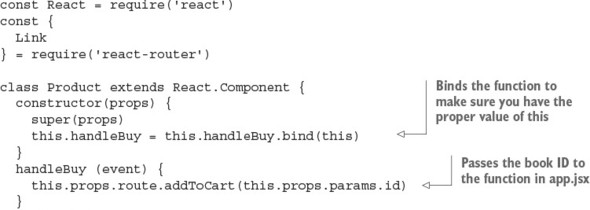

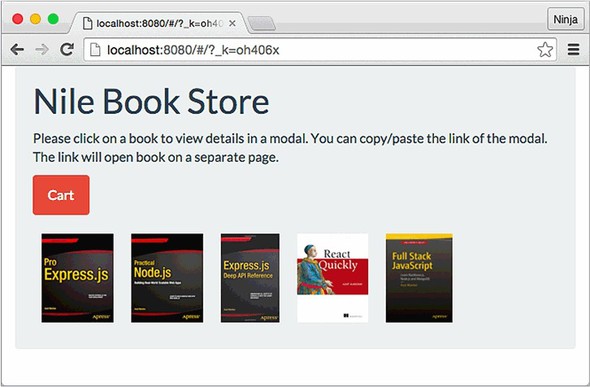

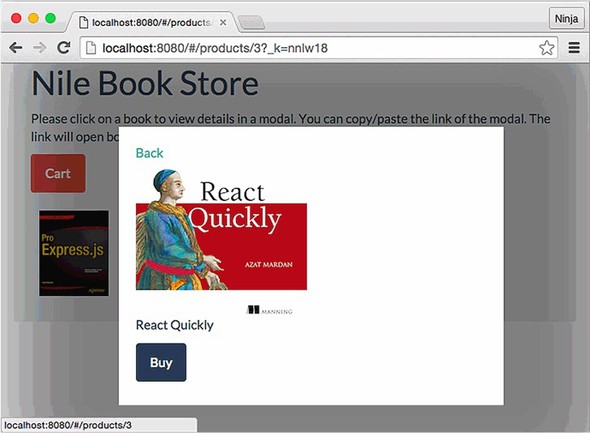

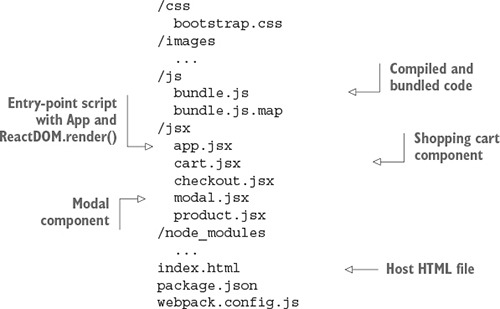

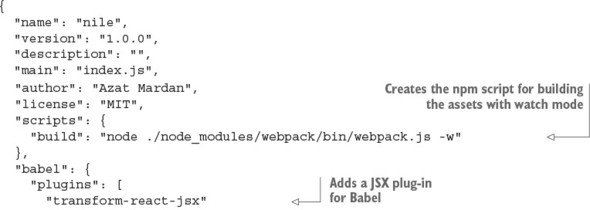

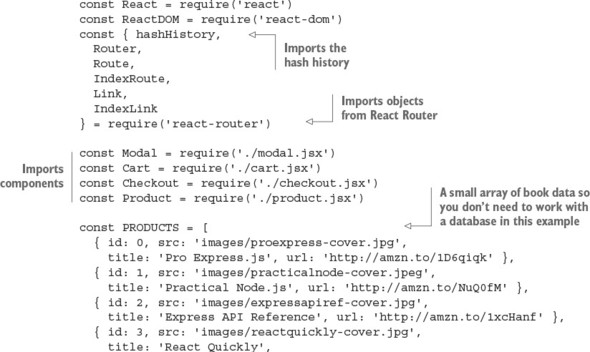

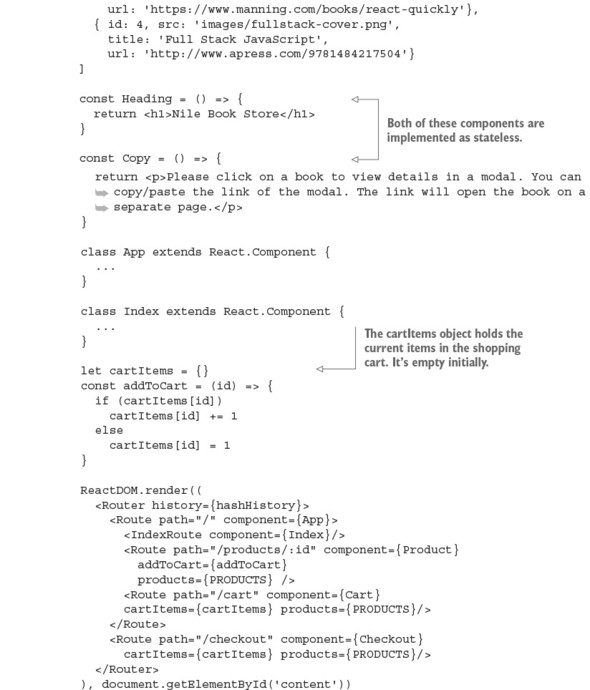

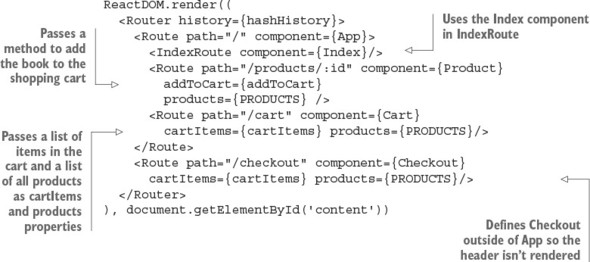

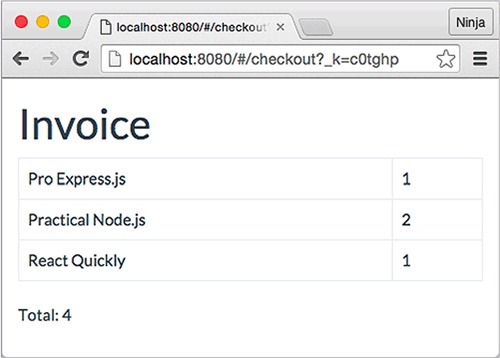

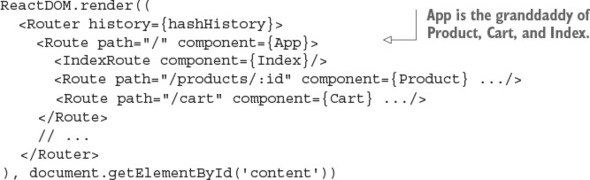

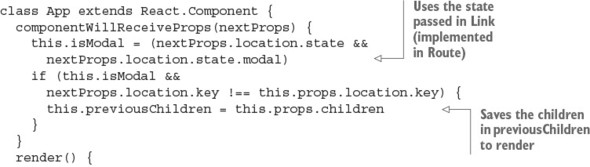

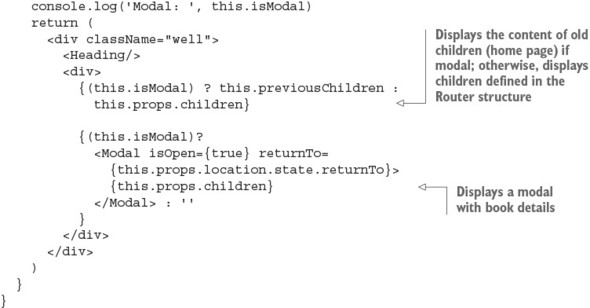

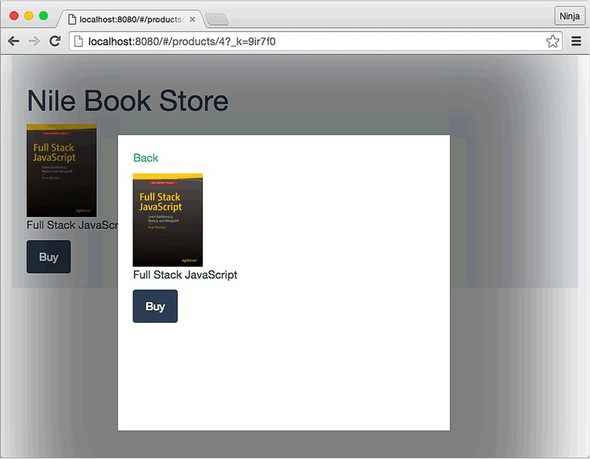

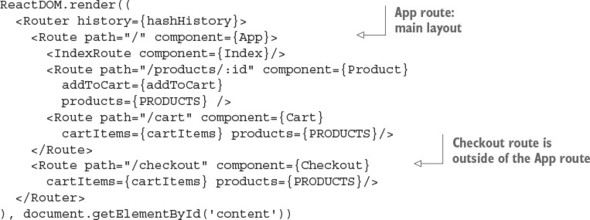

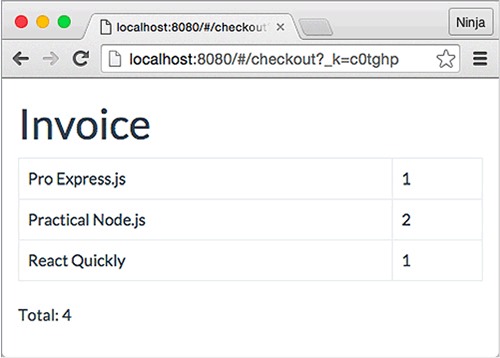

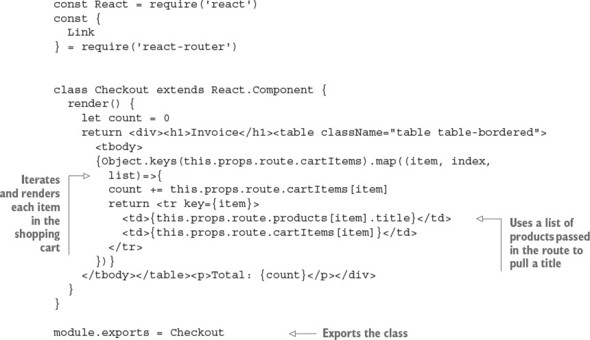

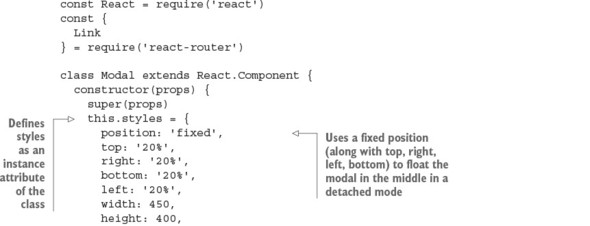

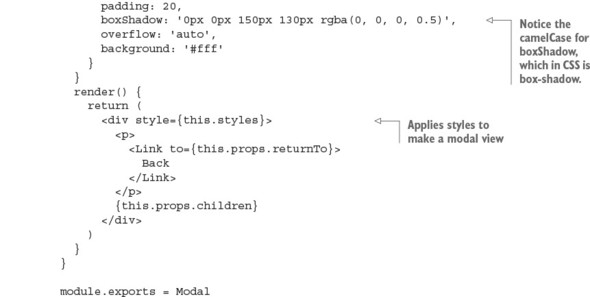

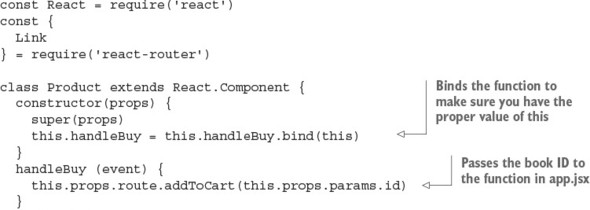

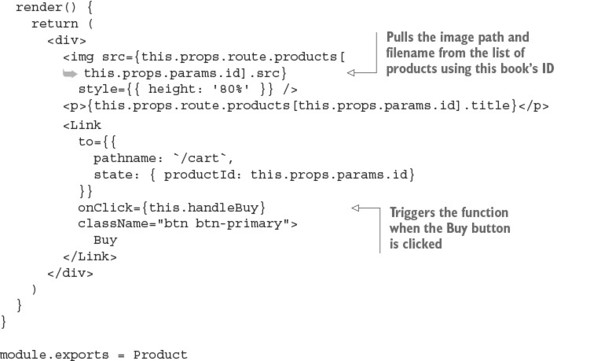

Chapter 18. Project: Building a bookstore with React Router

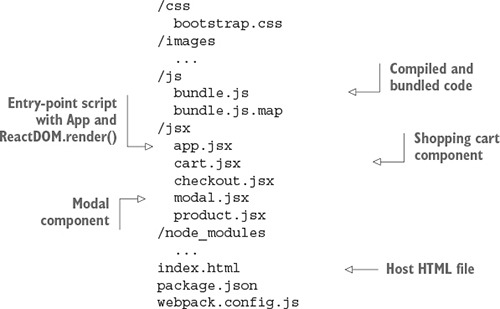

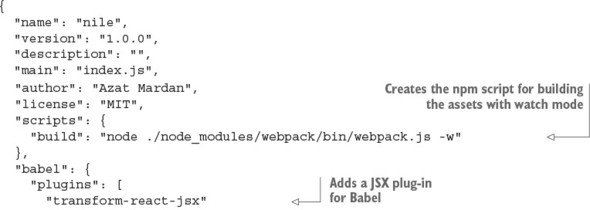

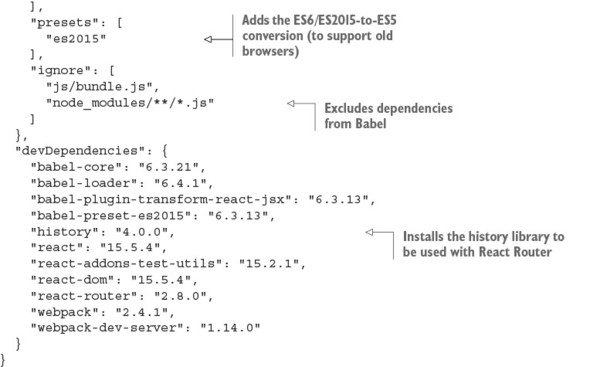

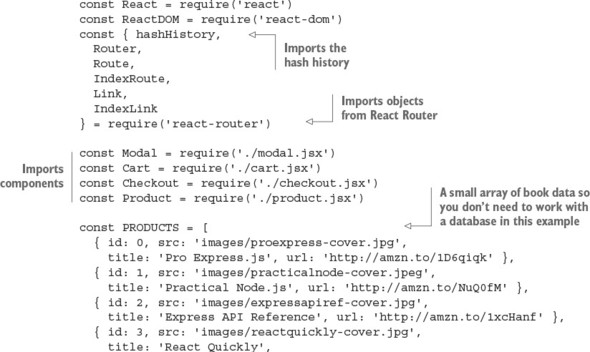

18.1. Project structure and Webpack configuration

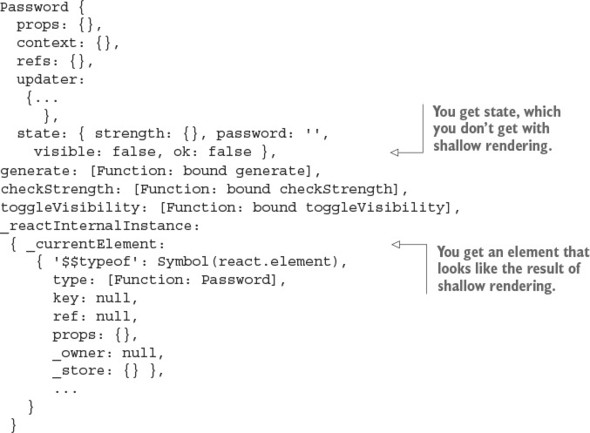

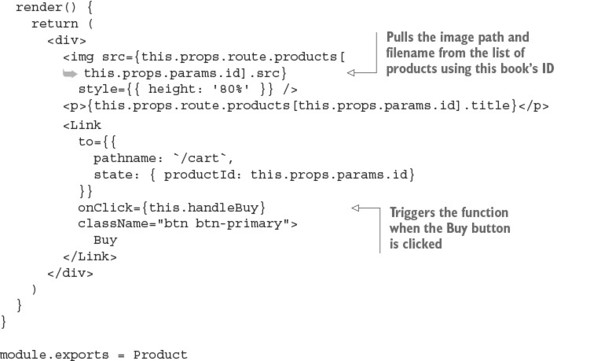

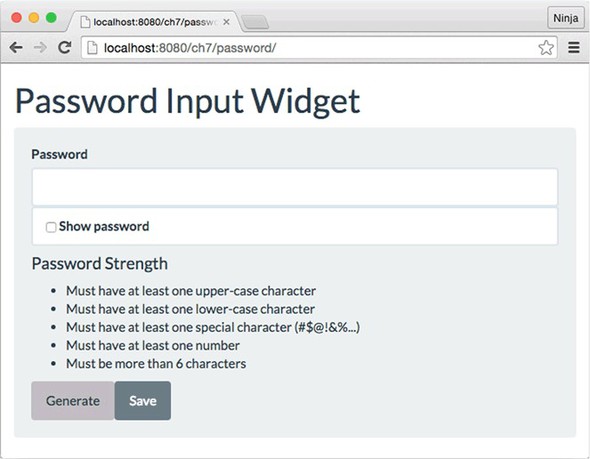

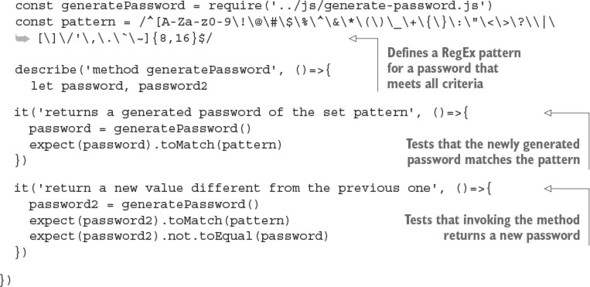

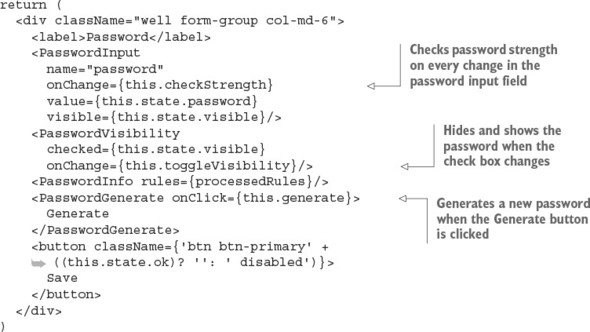

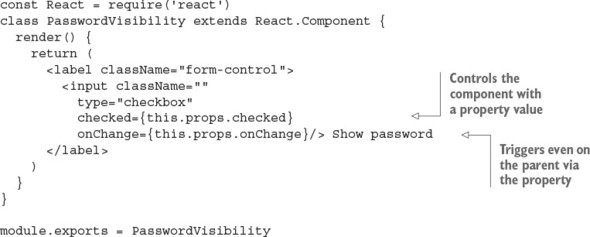

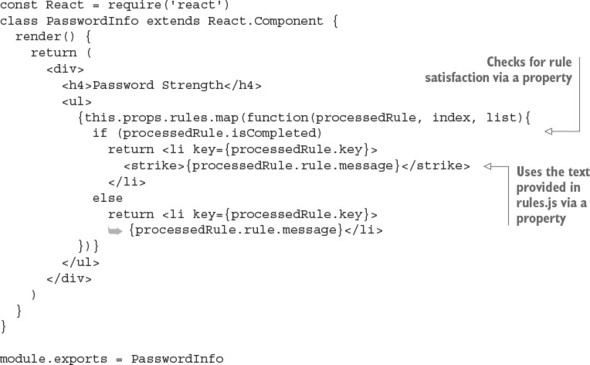

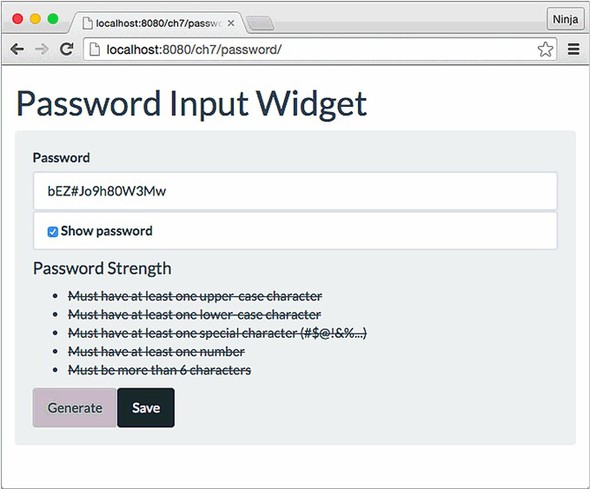

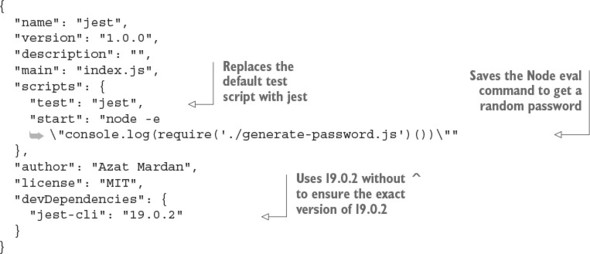

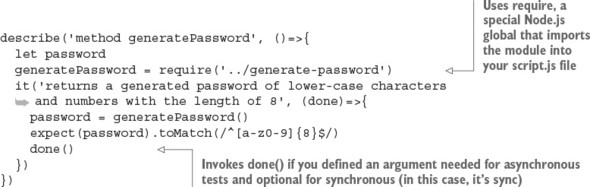

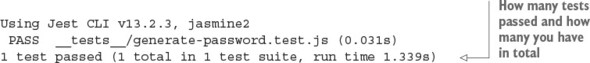

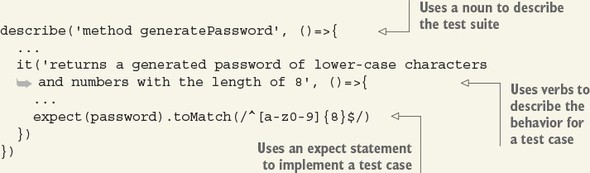

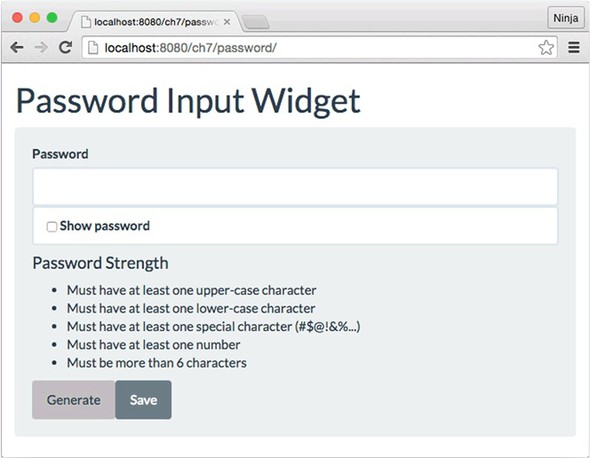

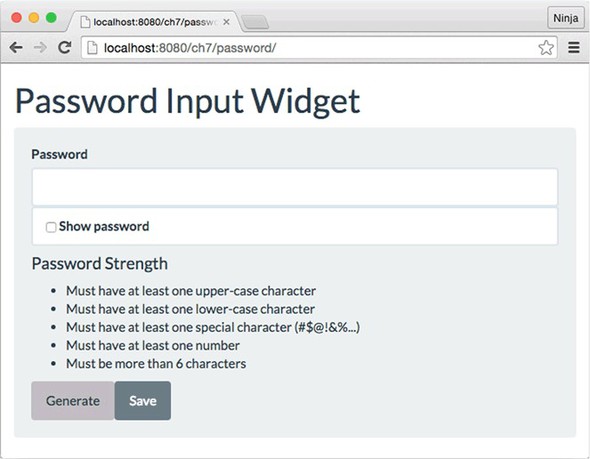

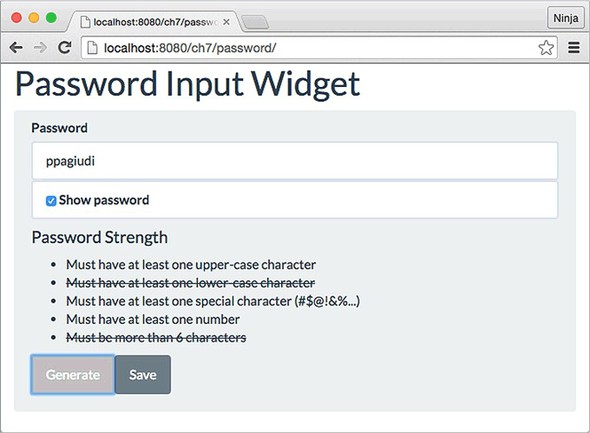

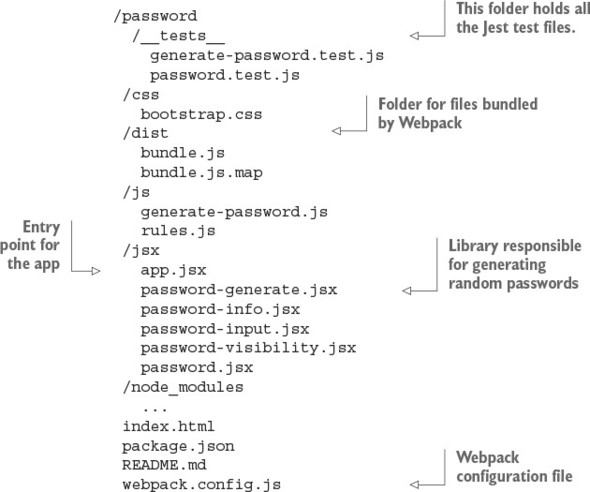

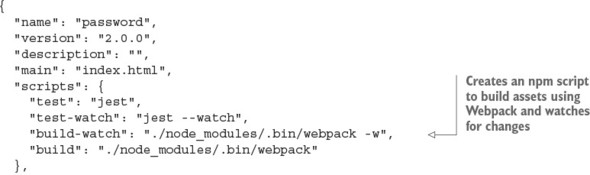

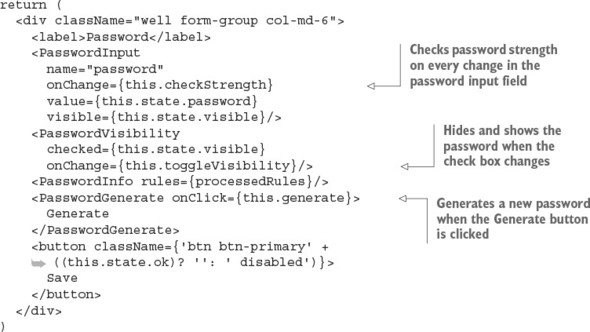

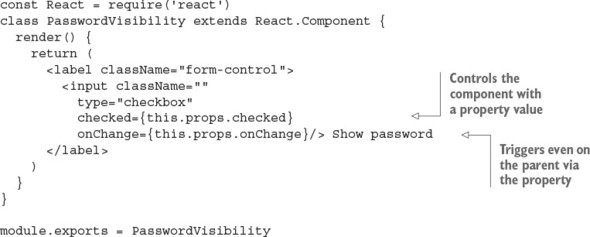

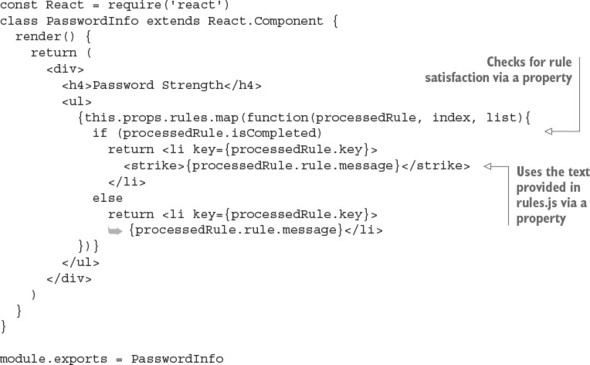

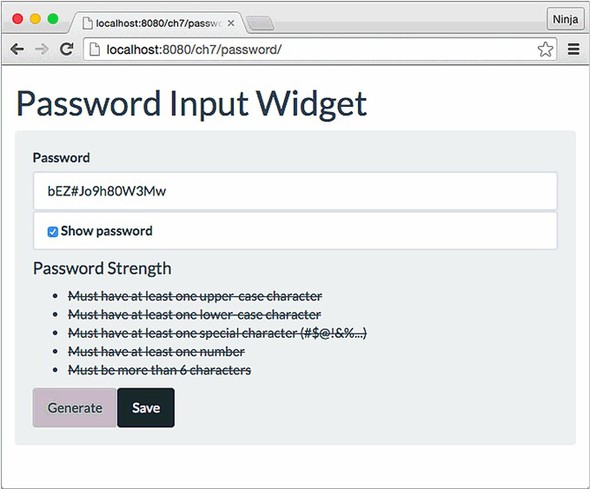

Chapter 19. Project: Checking passwords with Jest

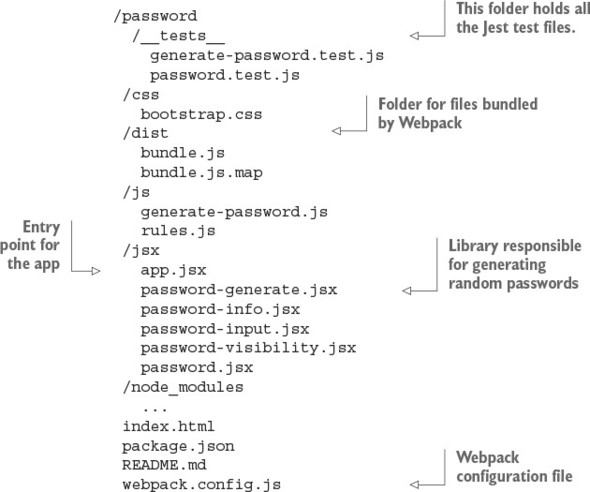

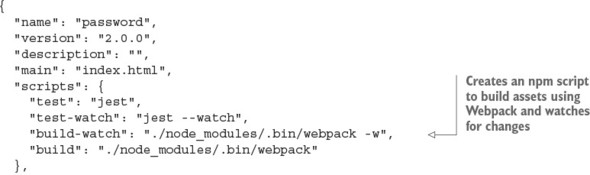

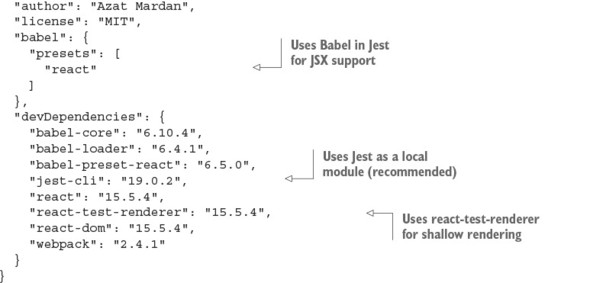

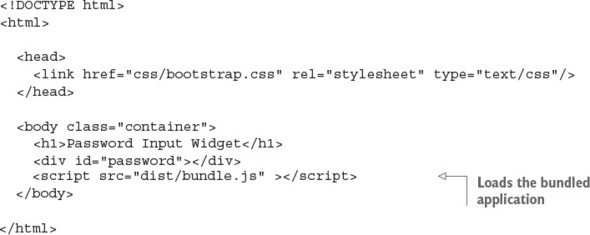

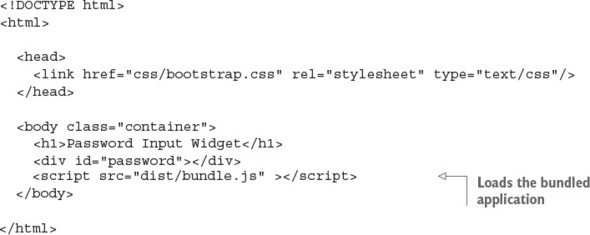

19.1. Project structure and Webpack configuration

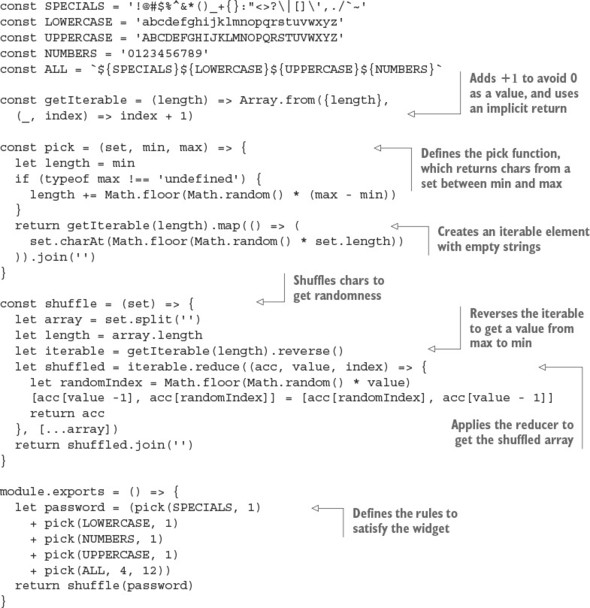

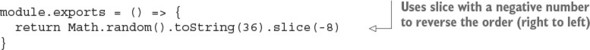

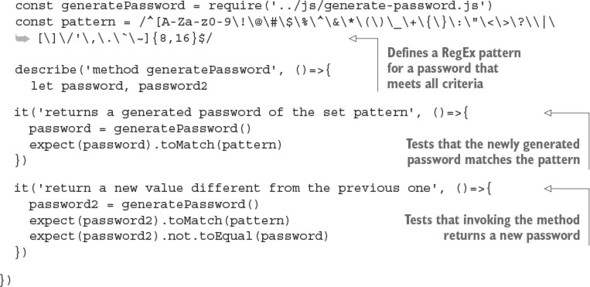

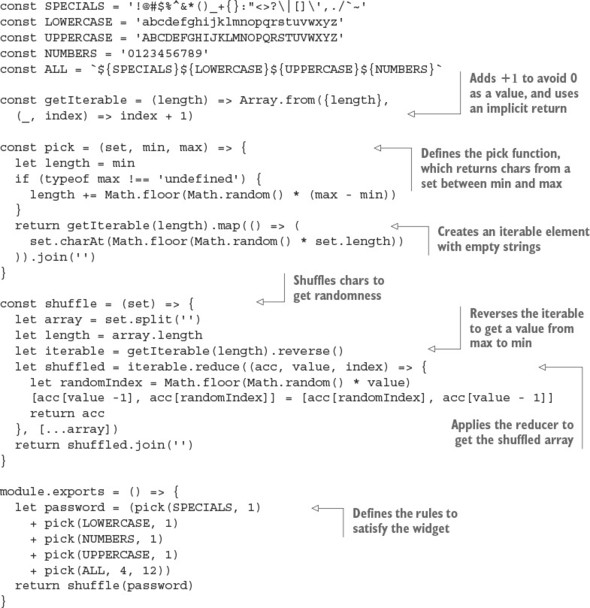

19.3. Implementing a strong password module

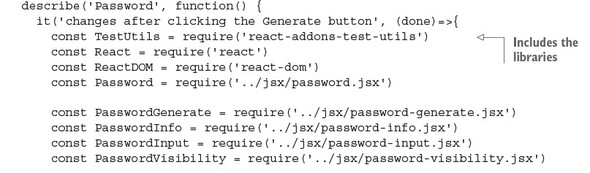

19.4. Implementing the Password component

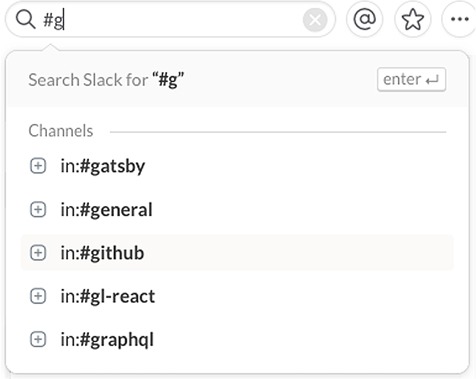

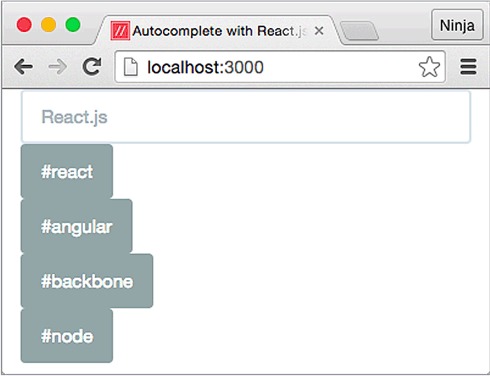

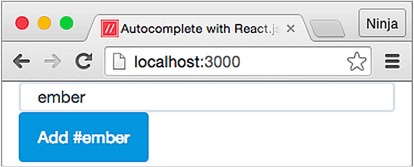

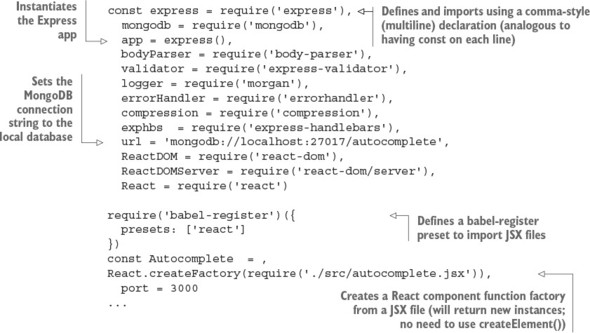

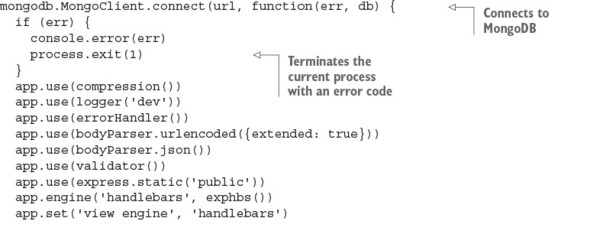

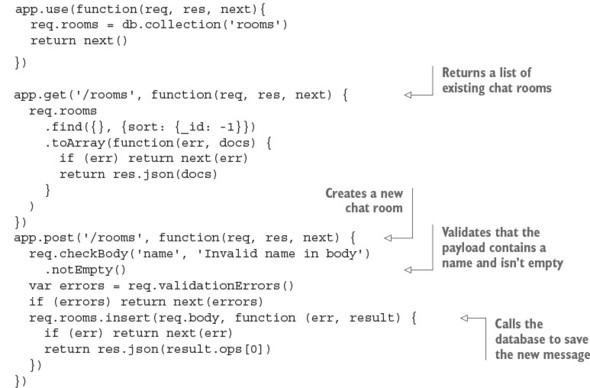

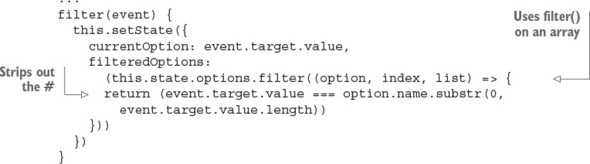

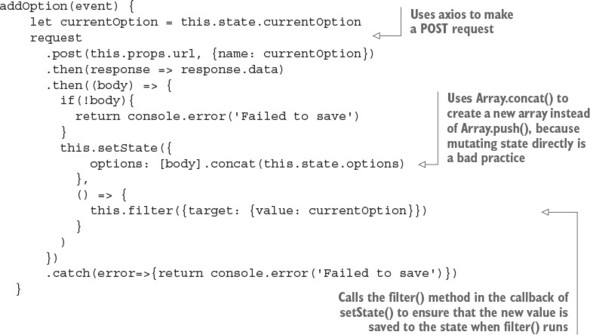

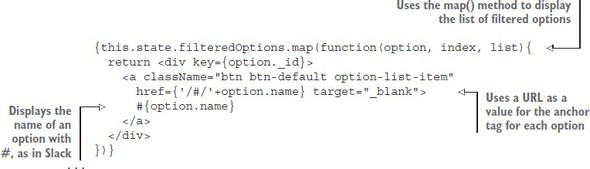

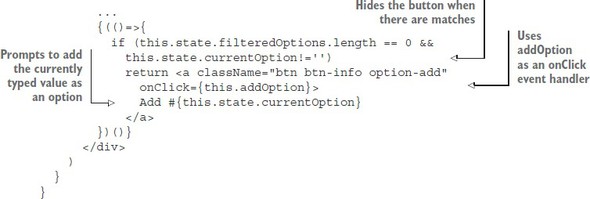

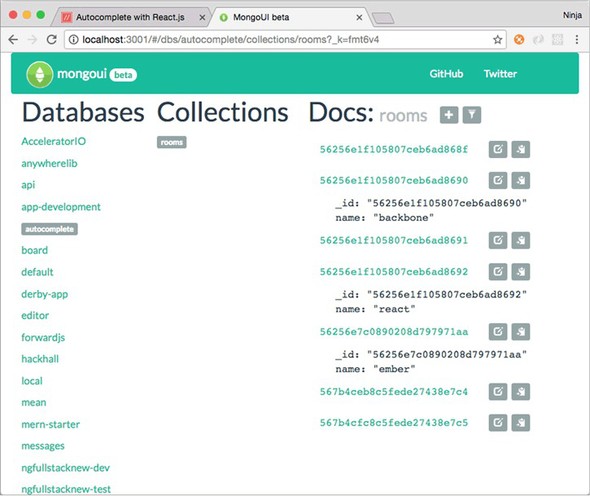

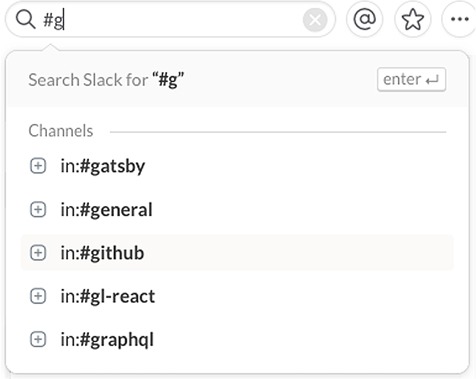

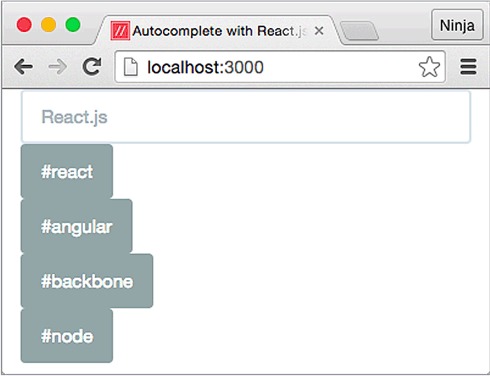

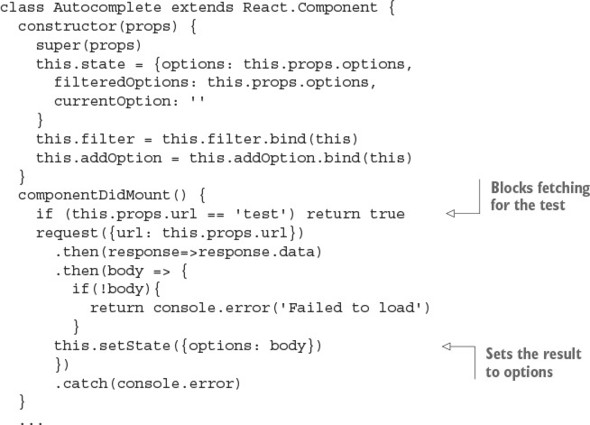

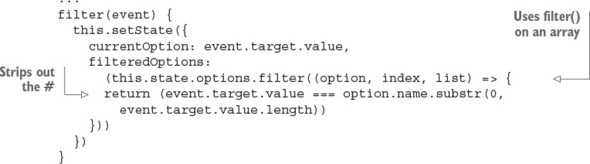

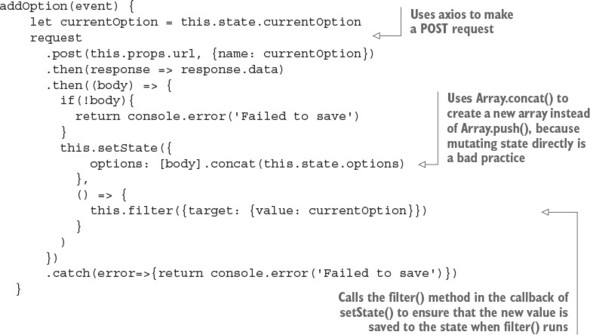

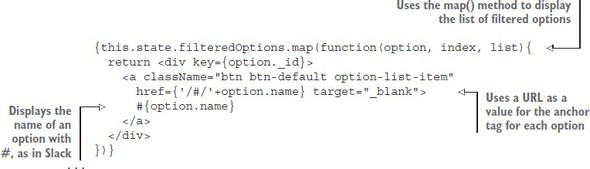

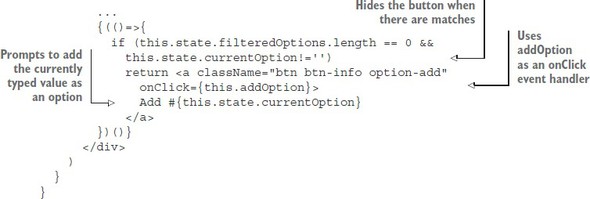

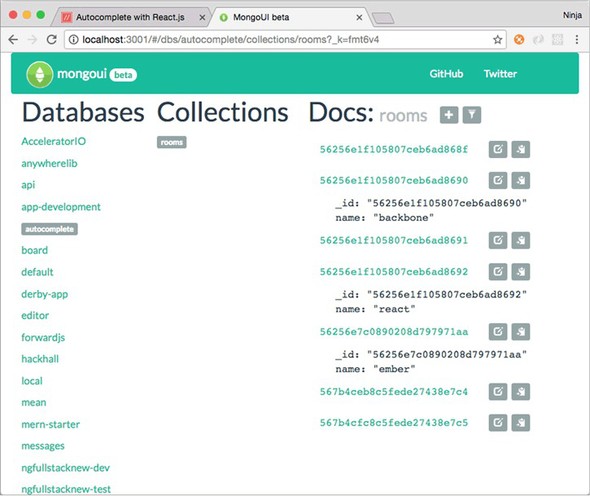

Chapter 20. Project: Implementing autocomplete with Jest, Express, and MongoDB

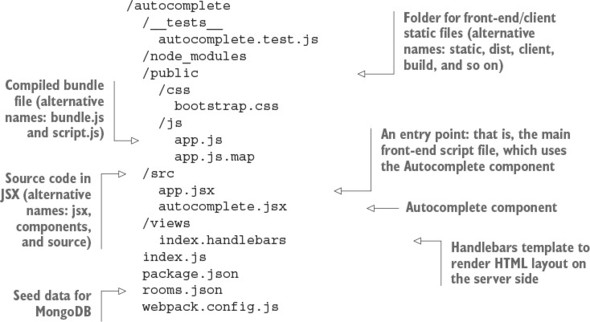

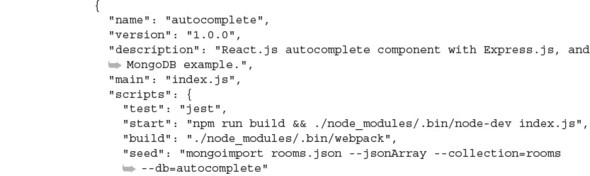

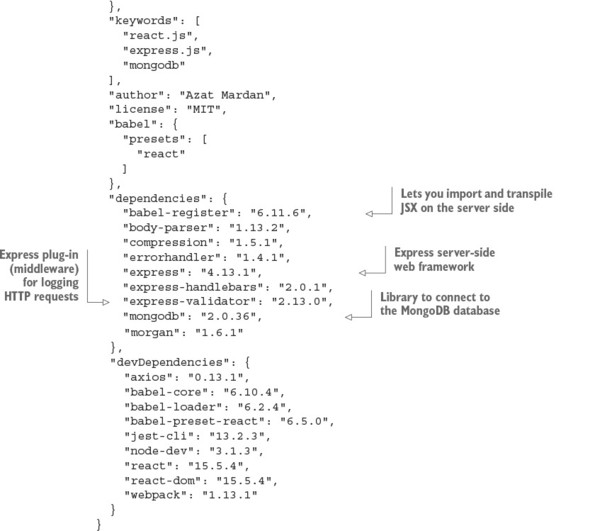

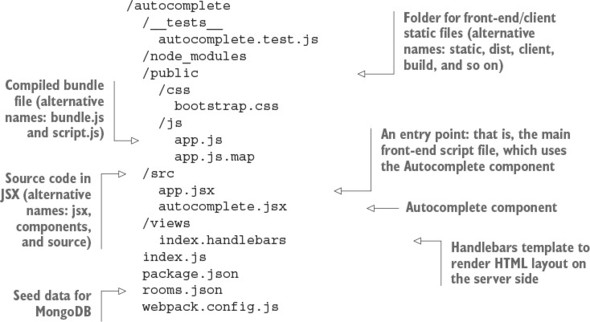

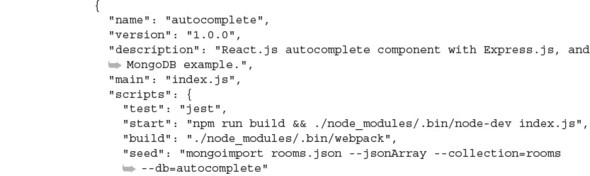

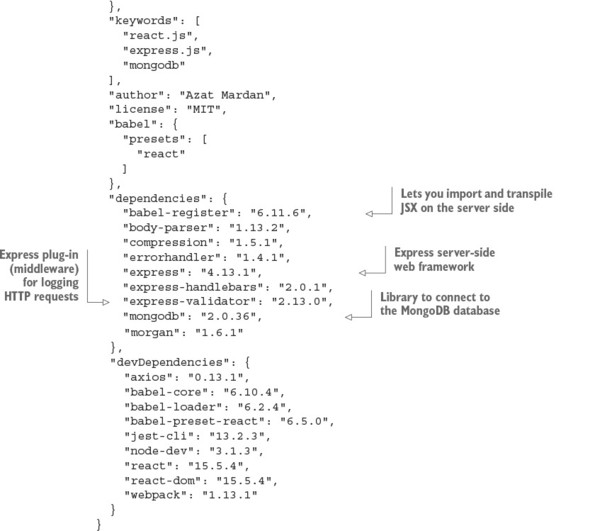

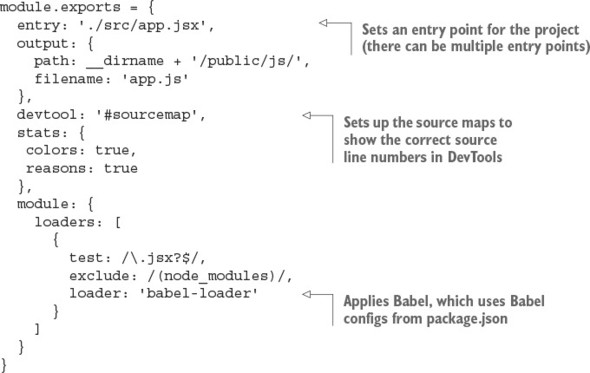

20.1. Project structure and Webpack configuration

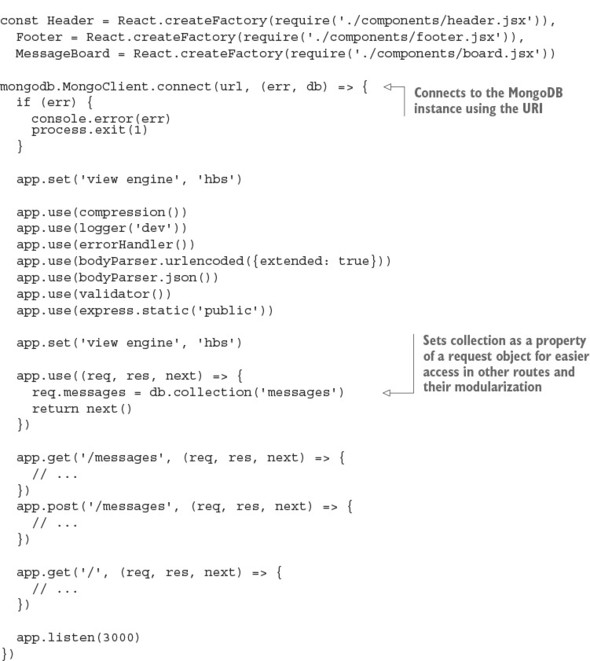

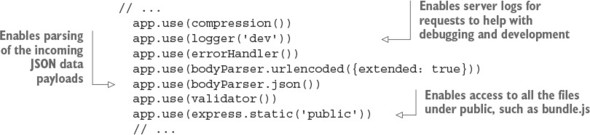

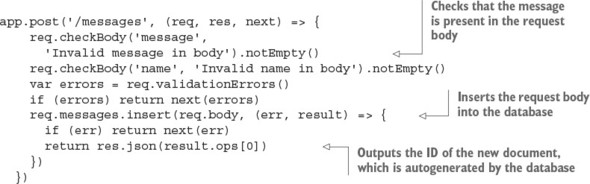

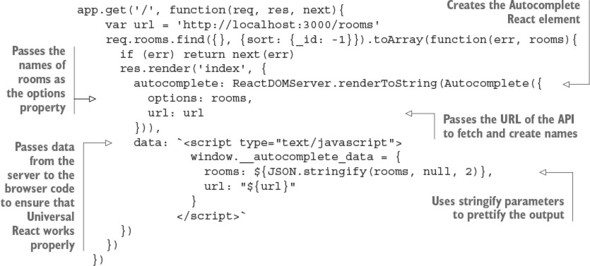

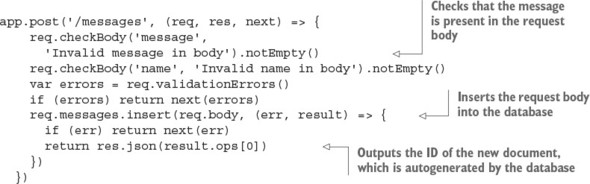

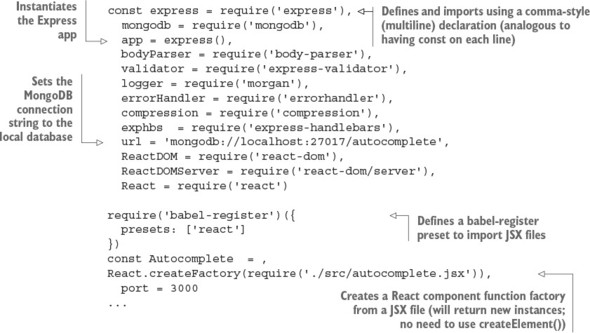

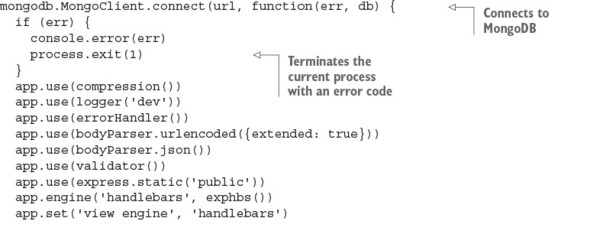

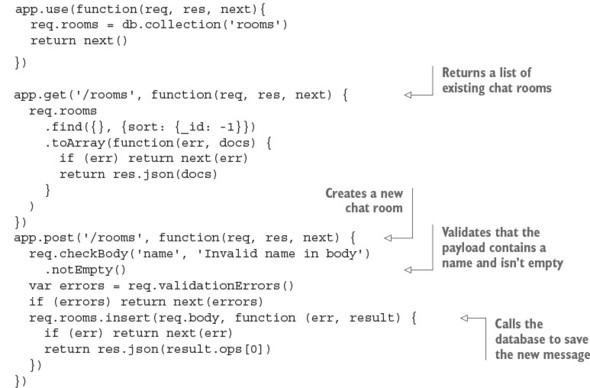

20.2. Implementing the web server

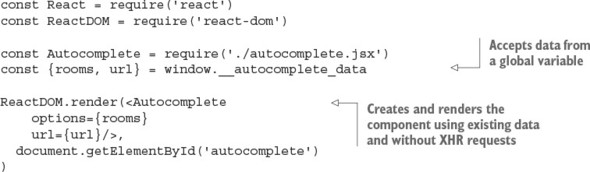

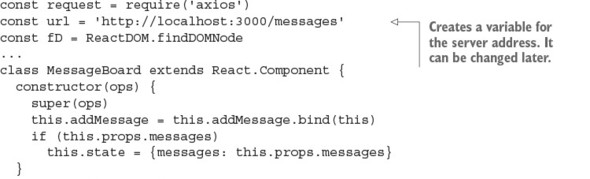

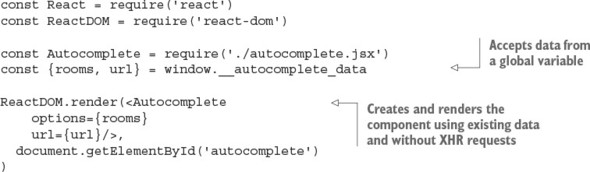

20.3. Adding the browser script

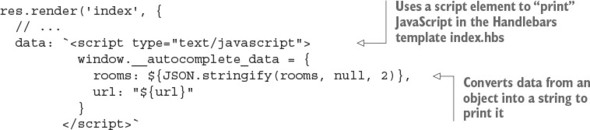

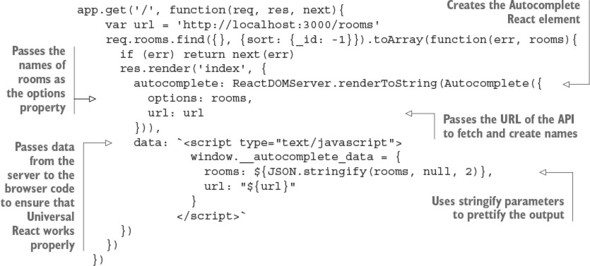

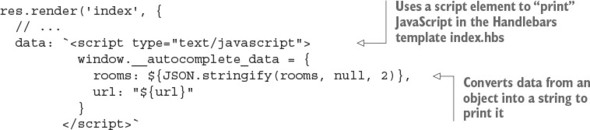

20.4. Creating the server template

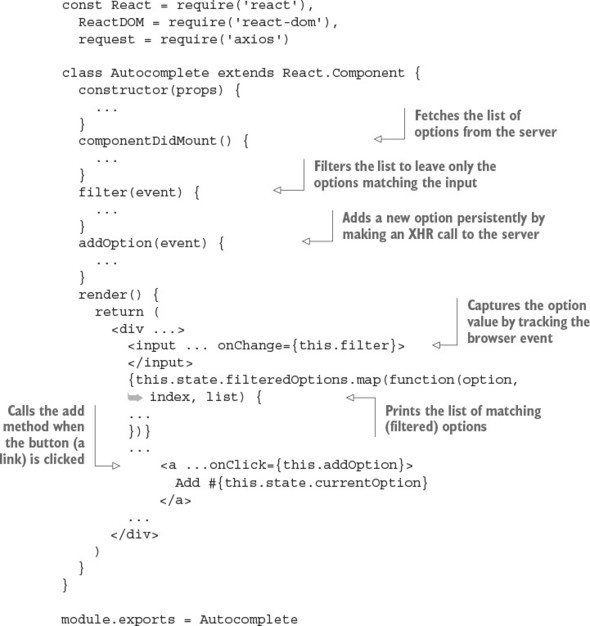

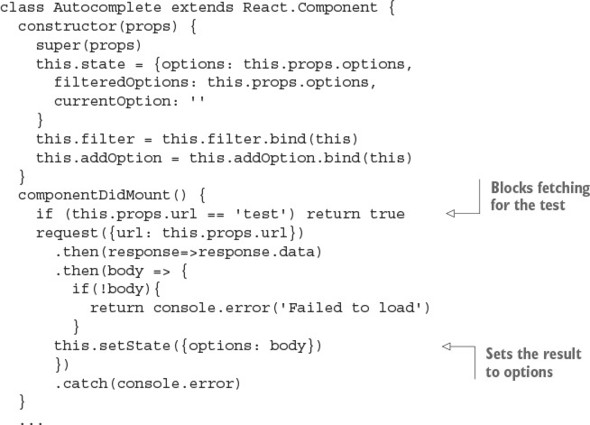

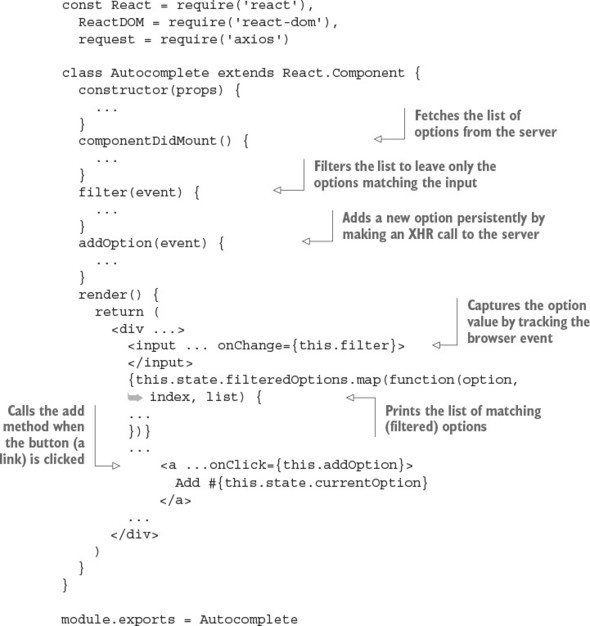

20.5. Implementing the Autocomplete component

Appendix A. Installing applications used in this book

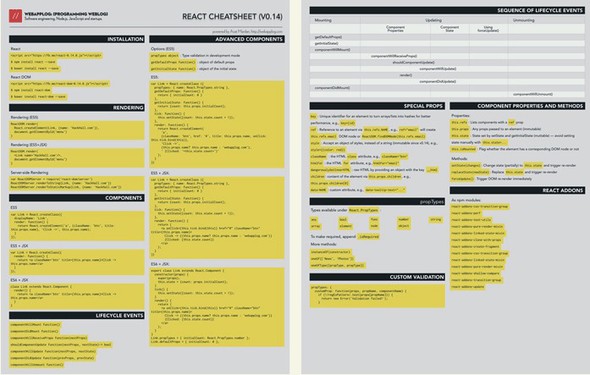

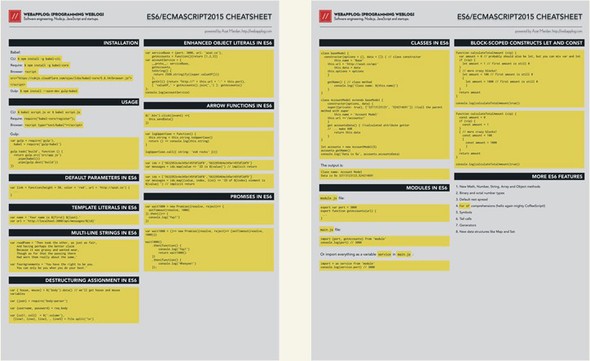

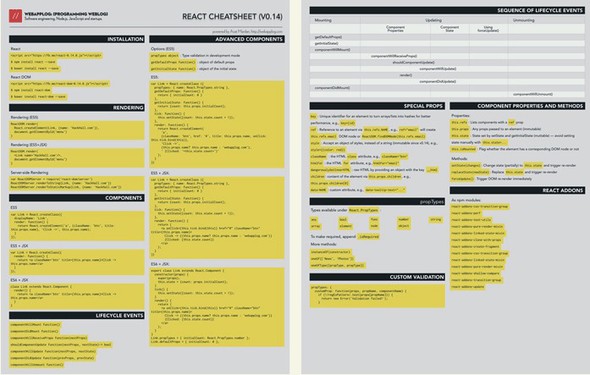

Using Babel to compile JSX and ES6

Sequence of lifecycle events (inspired by http://react.tips)

Component properties and methods

Appendix C. Express.js cheatsheet

Appendix D. MongoDB and Mongoose cheatsheet

“React Quickly is a one-stop shop for anyone who wants a guided introduction to React and the ecosystem of tools, concepts, and libraries around it. Follow Azat’s walkthroughs, work on the projects given, and you’ll soon understand React, Redux, GraphQL, Webpack, and Jest, as well as how to put them to work.”

Peter Cooper, editor of JavaScript Weekly

“React Quickly teaches the reader the most valuable and buzz-worthy concepts in building modern web applications with React including GraphQL, Webpack, and server-side rendering. After reading React Quickly, you should feel confident in your ability to create a production-grade web application with React.”

Stan Bershadskiy, author of React Native Cookbook

“Azat is one of the most authoritative voices in the programming space. This book goes far beyond the basics by deep diving into React’s foundation and architecture. It’s a must read for any developer!”

Erik Hanchett, author of Ember.js Cookbook

“This book is simple to follow. It uses very basic language that makes you understand each concept step by step.”

Israel Morales, front-end developer and web designer at SavvyCard

“Simple language with simple logical examples to get you up and running quickly is why this book truly justifies its title, React Quickly. This book covers all the major topics that any developer new to React needs in order to start writing apps using React. And the author’s sense of humor will keep you engaged until the end. I am thankful Azat took time to share his React journey with us.”

Suhas Deshpande, software engineer at Capital One

“React Quickly is a great resource for coming up to speed with React. Very thorough and relevant. I’ll be using it as a reference for my next app.”

Nathan Bailey, full stack developer at SpringboardAuto.com

“Azat is great at what he does—teaching people how to code. React Quickly contains fundamental knowledge as well as practical examples to get you started using React quickly.”

Shu Liu, IT consultant

“Since being open sourced by Facebook in 2013, React.js has rapidly become a widely adopted JS library and one of the most starred projects on GitHub. In his new book, React Quickly, Azat Mardan has, in his typical lucid style, laid out everything you need to learn about the React ecosystem in order to build performant SPA applications quickly. Just the chapters on React state and Universal JavaScript are worth the price of the book.”

Prakash Sarma, New Star Online

“React Quickly will ease your adoption of React by giving you a clear foundation, and it will have you building applications that thoroughly embrace the benefits of using React.

Allan Von Schenkel, VP of Technology & Strategy at FoundHuman

“React Quickly covers all the important aspects of React in an easy-to-consume fashion. This book is like all of Azat’s work: clear and concise, and it covers what’s needed to become productive quickly. If you are interested in adding React to your skill set, I say start here.”

Bruno Watt, consulting architect at hypermedia.tech

“React Quickly is an incredibly comprehensive book on full-stack web development with React.js, covering not just React itself but the ecosystem surrounding it. I’ve always been mystified by server-side React and found that Azat’s book really helped me finally understand it. If you’re new to React and would like to truly master it, I would look no further than this book.”

Richard Kho, software engineer at Capital One

I keep hoping that JavaScript will die. Seriously. Die brutally and painfully.

It’s not that I completely dislike JavaScript—it has improved quite a bit over the years. It’s that I have a severe distaste for complexity—so much so that I named my blog and my business Simple Programmer. My tagline has always been, “Making the complex simple.”

Making the complex simple isn’t easy. It takes a special set of skills. You have to be able to understand the complex, and understand it so well that you can distill it down to the core—because everything is simple at the core. This is exactly what Azat has done with this book, React Quickly.

Now, I’ll admit Azat had a little help. You see, one of the reasons I personally like ReactJS so much is that it’s simple. It was designed to be simple. It was designed to deal with the increasing complexity of JavaScript frameworks and reduce that complexity by going back to the basics: plain old JavaScript. (At least, for the most part. ReactJS does have a JSX language that’s compiled into JavaScript, but I’ll let Azat tell you about that.)

The point is, although I like Angular, Backbone, and some other JavaScript frameworks because they’ve helped make it much easier for web developers to create asynchronous web applications and single-page applications, they’ve also added a great deal of complexity. Using templates and understanding the syntax and subtleties of these frameworks increased productivity, but they moved the complexity from the backend to the frontend. ReactJS starts over, gets rid of templates, and gives you a way to apply component-based architecture to your UI using JavaScript. I like this. It’s simple. But even the simplest thing can be difficult to explain—or worse yet, made complex by a teacher who lacks this skill.

This is where Azat comes in. He knows how to teach. He knows how to simplify. He begins this book by explaining React through contrasting it with something you probably already know: Angular. Even if you don’t know Angular, his explanation of ReactJS will quickly help you understand the basics and its purpose. Then Azat quickly demonstrates how to create a basic ReactJS application, so you can see and do it for yourself. After that, he takes you through the 20% you need to know in order to accomplish 80% of what you’ll do in React, using real-world examples that anyone can grasp easily. Finally—and this is my favorite part—he includes examples and projects galore. The absolute best way to learn is by doing, and Azat walks you through creating six—yes, six—nontrivial projects using ReactJS.

In keeping with my theme of simplicity, I’ll leave off here by saying that React Quickly is simply the best way I know of to learn ReactJS.

JOHN SONMEZ

AUTHOR OF Soft Skills (http://amzn.to/2hFHXAu)

AND FOUNDER OF Simple Programmer (https://simpleprogrammer.com)

It was 2008, and banks were closing left and right. I was working at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), whose primary task is to pay back depositors of closed, failed, and insolvent banks. I admit that, in terms of job security, my job was on par with working at Lehman Brothers or being a ticket salesman for the Titanic. But when my department’s eventual budget cuts were still far in the future, I had the chance to work on an app called Electronic Deposit Insurance Estimator (EDIE). The app became hugely popular for a simple reason: people were anxious to find out how much of their savings was insured by the United States federal government, and EDIE estimated that amount.

But there was a catch: people don’t like to tell the government about their private accounts. To protect their privacy, the app was made entirely in front-end JavaScript, HTML, and CSS, without any back-end technologies. This way, the FDIC wasn’t collecting any financial information.

The app was a hot mess of spaghetti code left by dozens of iterations of consultants. Developers came and went, leaving no documentation and nothing resembling any logical, simple algorithms. It was like trying to use the New York City subway without a map. There were myriads of functions to call other functions, strange data structures, and more functions. In modern terminology, the app was pure user interface (UI), because it had no backend.

I wish I’d had React.js back then. React brings joy. It’s a new way of thinking—a new way of developing. The simplicity of having your core functionality in one place, as opposed to splitting it into HTML and JS, is liberating. It reignited my passion for front-end development.

React is a fresh way of looking at developing UI components. It’s a new generation of presentation layer libraries. Together with a model and routing library, React can replace Angular, Backbone, or Ember in the web and mobile tech stack. This is the reason I wrote this book. I never liked Angular: it’s too complex and opinionated. The template engine is very domain specific, to the point that it’s not JavaScript anymore; it’s another language. I have used Backbone.js and like it for its simplicity and DIY approach. Backbone.js is mature and more like a foundation for your own framework than a full-blown, opinionated framework in itself. The problem with Backbone is the increased complexity of interactions between models and views: multiple views update various models, which update other views, which trigger events on models.

My personal experience from doing a Kickstarter campaign for my React.js online course (http://mng.bz/XgkO) and from going to various conferences and events has shown me that developers are hungry for a better way to develop UIs. Most business value now lies in UIs. The backend is a commodity. In the Bay Area, where I live and work, most job openings in software engineering are for front-end or (a trendy new title) generalist/fullstack developers. Only a few big companies like Google, Amazon, and Capital One still have relatively strong demand for data scientists and back-end engineers.

The best way to ensure job security or get a great job in the first place is to become a generalist. The fastest way to do so is to use an isomorphic, scalable, developer-friendly library like React on the front end, paired with Node.js on the backend in case you ever need to mess with server-side code.

For mobile developers, HTML5 was a dirty word two or three years ago. Facebook dropped its HTML5 app in favor of a more performant native implementation. But this unfavorable view is quickly changing. With React Native, you can render for mobile apps: you can keep your UI components but tailor them to different environments, another point in favor of learning React.

Programming can be creative. Don’t get bogged down by mundane tasks, complexity, and fake separation of concerns. Cut out all the unnecessary junk, and unleash your creative power with the simplistic beauty of modular, component-based UIs powered by React. Throw in some Node for isomorphic/universal JavaScript, and you’ll achieve Zen.

Happy reading, and let me know how you like the book by leaving a review on Amazon.com (http://amzn.to/2gPxv9Q).

I’d like to acknowledge the internet, the universe, and the human ingenuity that brought us to the point that telepathy is possible. Without opening my mouth, I can share my thoughts with millions of people around the globe via social media such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Hurray!

I feel humongous gratitude to my teachers, both intentional at schools and universities, and accidental and occasional, whose wisdom I grasped from books and from learning by osmosis.

As Stephen King once wrote, “To write is human, to edit is divine.” Thus, my endless gratitude to the editors of this book and even more so to the readers who will have to deal with the inevitable typos and bugs they’ll encounter in this volume. This is my 14th book, and I know there will be typos, no mater what [sic].

I thank the people at Manning who made this book possible: publisher Marjan Bace and everyone on the editorial and production teams, including Janet Vail, Kevin Sullivan, Tiffany Taylor, Katie Tennant, Gordan Salinovic, Dan Maharry, and many others who worked behind the scenes.

I can’t thank enough the amazing group of technical peer reviewers led by Ivan Martinovic: James Anaipakos, Dane Balia, Art Bergquist, Joel Goldfinger, Peter Hampton, Luis Matthew Heck, Ruben J. Leon, Gerald Mack, Kamal Raj, and Lucas Tettamanti. Their contributions included catching technical mistakes, errors in terminology, and typos, and making topic suggestions. Each pass through the review process and each piece of feedback implemented through the forum topics shaped and molded the manuscript.

On the technical side, special thanks go to Anto Aravinth, who served as the book’s technical editor; and German Frigerio, who served as the book’s technical proofreader. They are the best technical editors I could have hoped for.

Many thanks go to John Sonmez of Pluralsight, Manning, and SimpleProgrammer.com fame, for writing the foreword to this book. Thank you, Peter Cooper, Erik Hanchett, and Stan Bershadskiy for your reviews and for giving the book extra credibility. Readers who haven’t heard of John, Peter, Erik, or Stan should subscribe and follow their work around software engineering.

Finally, a thank you to all the MEAP readers for your feedback. Revising the book based on your reviews delayed publication by a year, but the result is the best book currently available about React.

This book is intended to cure the troubles of front-end developers, make their lives more meaningful and happier, and help them earn more money by introducing them to React.js—and doing so in a fast manner (hence the word Quickly in the title). It’s the work of one and a half years and about a dozen people. At the very least, the book is meant to open your mind to some unusual concepts like JSX, unidirectional data flow, and declarative programming.

The book is split into two parts: “Core React” (chapters 1–11) and “React and friends” (chapters 12–20). Each chapter includes descriptive text supplemented with code examples and diagrams where they’re applicable. Each chapter also has an optional introductory video that will help you decide whether you need to read the chapter or can skip it. Chapters are written in a standalone manner, meaning you should have no trouble if you don’t read the book in order—although I do recommend reading it sequentially. At the end of each chapter is a quiz, to reinforce your retention of the material, and a summary.

Each part ends with a series of larger projects that will give you more experience with React and solidify your new understanding by building on the concepts and knowledge introduced in the previous chapters. The projects are supplemented by optional screencast videos to reinforce your learning and show you dynamic things like creating files and installing dependencies (there are a lot of moving parts in web development!). These projects are an integral part of the book’s flow—avoid skipping them. I encourage you to type each line of code yourself and abstain from copying and pasting. Studies have shown that typing and writing increase learning effectiveness.

The book ends with five appendixes that provide supplemental material. Check them out, along with the table of contents, before you begin reading.

The websites for this book are www.manning.com/books/react-quickly and http://reactquickly.co. If you need up-to-date information, most likely you’ll find it there.

The source code is available on the Manning website (www.manning.com/books/react-quickly) and on GitHub (https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly). See the “Source code” section for more details. I show full listings of the code in the book—this is more convenient than jumping to GitHub or a code editor to look at the files.

This book is for web and mobile developers and software engineers with two to three years of experience, who want to start learning and using React.js for web or mobile development. Basically, it’s for people who know the shortcut for the Developer Tools by heart (Cmd-Opt-J or Cmd-Opt-I on Macs). The book targets readers who know and are on a first-name basis with these concepts:

Having experience with jQuery, Angular, Ember.js, Backbone.js, or other MVC-like frameworks is a plus, because you’ll be able to contrast them with the React way. But it’s not necessary and to some degree may be detrimental, because you’ll need to unlearn certain patterns. React is not exactly MVC.

You’ll be using command-line tools, so if you’re afraid of them, this is the best time to fight your phobia of the command line/Terminal/command prompt. Typically, CLIs are more powerful and versatile than their visual (GUI) versions (for example, the Git command line versus the GitHub desktop—the latter confuses the heck out of me).

Having some familiarity with Node.js will allow you to learn React much more quickly than someone who’s never heard of Node.js, npm, Browserify, CommonJS, Gulp, or Express.js. I’ve authored several books on Node.js for those who want to brush up on it, the most popular being Practical Node.js (http://practicalnodebook.com). Or, you can go online for a free NodeSchool adventure (http://nodeschool.io) (free does not always mean worse).

This book is not a comprehensive guide to web or mobile development. I assume that you already know about those. If you want help with basic programming concepts or JavaScript fundamentals, there are plenty of good books on those topics. You Don’t Know JS by Kyle Simpson (free to read at https://github.com/getify/You-Dont-Know-JS), Secrets of the JavaScript Ninja, Second Edition (www.manning.com/books/secrets-of-the-javascript-ninja-second-edition), and Eloquent JavaScript by Marijn Haverbeke (free to read at http://eloquentjavascript.net) come to mind. So, there’s no need for me to duplicate existing content with this book.

First of all, you should read this book. That is not a joke. Most people buy books but never read them. It’s even easier to do so with digital copies, because they hide on drives and in the cloud. Read the book, and work through the projects, chapter by chapter.

Each chapter covers either a topic or a series of topics that build on each other. For this reason, I recommend that you read this book from beginning to end and then go back to individual chapters for reference. But as I said earlier, you can also read individual chapters out of order, because the projects in the chapters stand alone.

There are many links to external resources. Most of them are optional and provide additional details about topics. Therefore, I suggest that you read the book at your computer, so you can open links as I refer to them.

Some text appears in a monospace font, like this: getAccounts(). That means it’s code, inline or in blocks. Sometimes you’ll see code with weird indentation:

document.getElementById('end-of-time').play()

}

This means I’m annotating a large chunk of code and broke it into pieces. This piece belongs to a bigger listing that started from position 0; this small chunk won’t run by itself.

Other times, code blocks aren’t indented. In such cases, it’s generally safe to assume that the snippet is the whole thing:

ReactDOM.render(

<Content />,

document.getElementById('content')

)

If you see a dollar sign ($), it’s a Terminal/command prompt command. For example:

$ npm install -g babel@5.8.34

The most important thing to know and remember while using this book is that you must have fun. If it’s not fun, it’s not JavaScript!

All of the book’s code is available at www.manning.com/books/react-quickly and https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly. Follow the folder-naming convention chNN, where NN is the chapter number with a leading 0 if needed (for example, ch02 for chapter 2’s code). The source code in the GitHub repository will evolve by including patches, bug fixes, and maybe even new versions and styles (ES2020?).

I’m sure there are typos in this book. Yes, I had editors—a bunch of them, all professionals provided by Manning. But thanks for finding that typo. No need to leave nasty Amazon reviews or send me hate mail about it, or about grammar.

Please don’t email me bugs and typos. Instead, you can report them on the book’s forum at https://forums.manning.com/forums/react-quickly or create a GitHub issue at https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly/issues. This way, other people can benefit from your findings.

Also, please don’t email me technical questions or errata. Post them on the book’s forum, the book’s GitHub page (https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly), or Stack Overflow. Other people may help you more quickly (and better) than I can.

Purchase of React Quickly includes free access to a private web forum run by Manning Publications where you can make comments about the book, ask technical questions, and receive help from the author and from other users. To access the forum, go to https://forums.manning.com/forums/react-quickly. You can also learn more about Manning’s forums and the rules of conduct at https://forums.manning.com/forums/about.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialogue between individual readers, and between readers and the author, can take place. It is not a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contribution to the forum remains voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you try asking the author some challenging questions lest his interest stray! The forum and the archives of previous discussions will be accessible from the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

I’ve published more than 14 books and 17 online courses (https://node.university), most of them on the cloud, React, JavaScript, and Node.js. (One book is about how to write books, and another is about what to do after you’ve written a few books.) Before focusing on Node, I programmed in other languages (Java, C, Perl, PHP, Ruby), pretty much ever since high school (more than a dozen years ago) and definitely more than the 10,000 hours prescribed.[1]

Right now, I’m a Technology Fellow at one of the top 10 U.S. banks, which is also a Fortune 500 company: Capital One Financial Corporation, in beautiful San Francisco. Before that, I worked for small startups, giant corporations, and even the U.S. federal government, writing desktop, web, and mobile apps; teaching; and doing developer evangelism and project management.

I don’t want to take too much of your time telling you about myself; you can read more on my blog (http://webapplog.com/about) and social media (www.linkedin.com/in/azatm). Instead, I want to write about my experience that’s relevant to this book.

When I moved to the sunny state of California in 2011 to join a startup and go through a business accelerator (if you’re curious, it was 500 Startups), I started to use modern JavaScript. I learned Backbone.js to build a few apps for the startup, and I was impressed. The framework was a huge improvement in code organization over other SPAs I’d built in prior years. It had routes and models. Yay!

I had another chance to see the astounding power of Backbone and isomorphic JavaScript during my work as software engineering team lead at DocuSign, the Google of e-signatures (it has a 70% market share). We reengineered a seven-year-old monolithic ASP.NET web app that took four weeks for each minor release into a snappy Backbone-Node-CoffeeScript-Express app that had great user experience and took only one or two weeks for its release. The design team did great work with usability. Needless to say, there were boatloads of UI views with various degrees of interactivity.

The end app was isomorphic before such a term even existed. We used Backbone models on the server to prefetch the data from APIs and cache it. We used the same Jade templates on the browser and the server.

It was a fun project that made me even more convinced of the power of having one language across the entire stack. Developers versed in C# and front-end JavaScript (mostly jQuery) from the old app would spend a sprint (one release cycle, typically a week or two) and fall in love with the clear structure of CoffeeScript, the organization of Backbone, and the speed of Node (both the development and the running speed).

My decade in web development exposed me to the good, the bad, and the ugly (mostly ugly) of front-end development. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise, because I came to appreciate React even more, once I switched to it.

If you’d like to receive updates, news, and tips, then connect with me online by following, subscribing, friending, stalking, whatever:

For in-person workshops and courses, visit http://NodeProgram.com or https://Node.University, or send me a message via https://webapplog.com/azat.

An email from an early reader asked about the dervish on the cover. Yes, the character could easily be a Persian or any one of many Turko-nomadic people inhabiting the Middle East and central Asia. This is due to the fact that trade and travel were highly developed and frequent among those regions for many centuries. But, according to the illustrator who drew this picture, he was depicting a Siberian Bashkir. Most of the modern-day Bashkirs live in the Republic of Bashkortostan (a.k.a. Bashkiria). Bashkirs are close ethnic and geographical neighbors of the Volga Bulgars (improperly named Tatars); Bashkirs and Tatars are the second-most-populous ethnic group in the Russian Federation. (The first is Russians, if you’re curious.)

The figure comes from an eighteenth-century illustration, “Gravure Homme Baschkir,” by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur. Fascination with faraway lands and travel for pleasure were relatively new phenomena at the time, and collections of drawings such as this one were popular, introducing both the tourist as well as the armchair traveler to the inhabitants of other countries. The rich variety of drawings reminds us vividly of how culturally apart the world’s regions, towns, villages, and neighborhoods were just 200 years ago. Isolated from each other, people spoke different dialects and languages. In the streets or in the countryside, it was easy to identify where they lived and what their trade or station in life was, just by their dress.

Dress codes have changed since then and the diversity by region, so rich at the time, has faded away. It is now hard to tell apart the inhabitants of different continents, let alone different towns or regions. Perhaps we have traded cultural diversity for a more varied personal life—certainly for a more varied and fast-paced technological life.

At a time when it is hard to tell one computer book from another, Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of regional life of two centuries ago, brought back to life by pictures such as this one.

Hello! My name is Azat Mardan, and I’m going to take you on a journey into the wonderful world of React. It will make your front-end development more enjoyable and your code easier to write and maintain, and your users will be delighted at the speed of your web apps. React is a game changer in web development: the React community has pioneered many approaches, terms, and design patterns, and other libraries have followed the path forged by React.

I’ve taught this material more than 20 times in my live-online and in-person workshops to hundreds of software engineers from very different backgrounds and varied levels of seniority. Thus, this material has been battle tested on my students: you’re getting the distilled, most effective version of my React foundation course in a written format. These chapters are critical to get you on familiar terms with React.

Chapters 1–11 are the result of almost two years of work by several people, but they read as a fast sequence of topics that build on each other. The best way to consume these chapters is to start with chapter 1 and proceed in order. Each chapter includes a video message from me; chapters 1–8 have a quiz at the end; and chapters 9–11, which are projects, contain homework for self-guided development.

All in all, this part of the book builds a solid foundation of React concepts, patterns, and features. Can you go to a foreign country and understand the language without studying? No—and that’s why you must learn the React “language” before you attempt to build complex apps. Thus, it’s paramount that you study these basic React concepts—that you learn the React language—which is exactly what you’ll do in the next 11 chapters.

Let’s get started with React—and learn to speak fluent React-ese.

This chapter covers

When I began working on web development in early 2000, all I needed was some HTML and a server-side language like Perl or PHP. Ah, the good old days of putting in alert() boxes just to debug your front-end code. It’s a fact that as the internet has evolved, the complexity of building websites has increased dramatically. Websites have become web applications with complex user interfaces, business logic, and data layers that require changes and updates over time—and often in real time.

Many JavaScript template libraries have been written to try to solve the problems of dealing with complex user interfaces (UIs). But they still require developers to adhere to the old separation of concerns—which splits style (CSS), data and structure (HTML), and dynamic interactions (JavaScript)—and they don’t meet modern-day needs. (Remember the term DHTML?)

In contrast, React offers a new approach that streamlines front-end development. React is a powerful UI library that offers an alternative that many big firms such as Facebook, Netflix, and Airbnb have adopted and see as the way forward. Instead of defining a one-off template for your UIs, React allows you to create reusable UI components in JavaScript that you can use again and again in your sites.

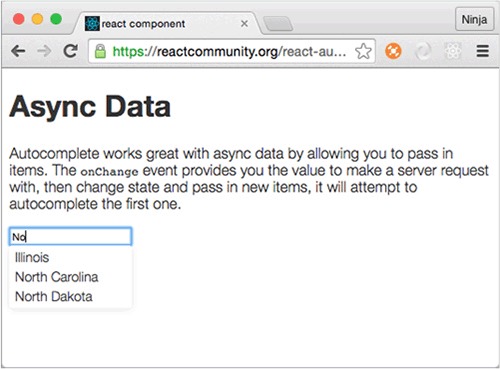

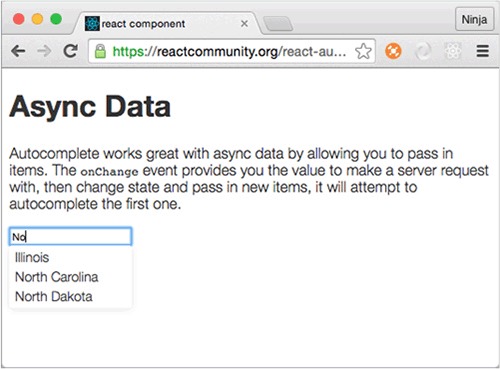

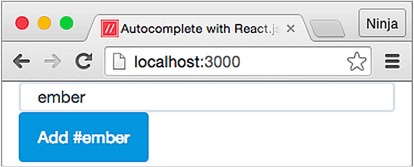

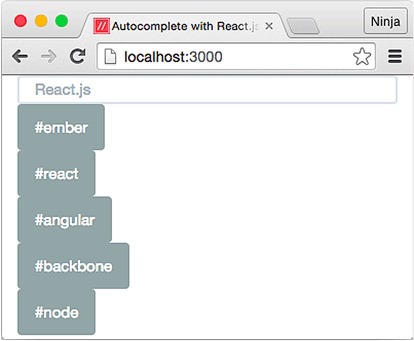

Do you need a captcha control or date picker? Then use React to define a <Captcha /> or <DatePicker /> component that you can add to your form: a simple drop-in component with all the functionality and logic to communicate with the back end. Do you need an autocomplete box that asynchronously queries a database once the user has typed four or more letters? Define an <Autocomplete charNum="4"/> component to make that asynchronous query. You can choose whether it has a text box UI or has no UI and instead uses another custom form element—perhaps <Autocomplete textbox="..." />.

This approach isn’t new. Creating composable UIs has been around for a long time, but React is the first to use pure JavaScript without templates to make this possible. And this approach has proven easier to maintain, reuse, and extend.

React is a great library for UIs, and it should be part of your front-end web toolkit; but it isn’t a complete solution for all front-end web development. In this chapter, we’ll look at the pros and cons of using React in your applications and how you might fit it into your existing web-development stack.

Part 1 of the book focuses on React’s primary concepts and features, and part 2 looks at working with libraries related to React to build more-complex front-end apps (a.k.a. React stack or React and friends). Each part demonstrates both greenfield and brownfield development[1] with React and the most popular libraries, so you can get an idea of how to approach working with it in real-world scenarios.

Brownfield is a project with legacy code and existing systems, while greenfield is a project without any legacy code or systems; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brownfield_(software_development).

We all learn differently. Some people prefer text and others video, and others learn best via in-person instruction. Each chapter of this book includes a short video that explains the chapter’s gist in less than 5 minutes. Watching them is totally optional. They’ll give you a summary if you prefer a video format or need a refresher. After watching each video, you can decide whether you need to read the chapter or can skip to the next one.

The source code for the examples in this chapter is at www.manning.com/books/reactquickly and at https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly/tree/master/ch01 (in the ch01 folder of the GitHub repository https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly). You can also find some demos at http://reactquickly.co/demos.

To introduce React.js properly, I first need to define it. So, what is React? It’s a UI component library. The UI components are created with React using JavaScript, not a special template language. This approach is called creating composable UIs, and it’s fundamental to React’s philosophy.

React UI components are highly self-contained, concern-specific blocks of functionality. For example, there could be components for date-picker, captcha, address, and ZIP code elements. Such components have both a visual representation and dynamic logic. Some components can even talk to the server on their own: for example, an autocomplete component might fetch the autocompletion list from the server.

In a broad sense, a user interface[2] is everything that facilitates communication between computers and humans. Think of a punch card or a mouse: they’re both UIs. When it comes to software, engineers talk about graphical user interfaces (GUIs), which were pioneered for early personal computers such as Macs and PCs. A GUI consists of menus, text, icons, pictures, borders, and other elements. Web elements are a narrow subset of the GUI: they reside in browsers, but there are also elements for desktop applications in Windows, OS X, and other operating systems.

Every time I mention a UI in this book, I mean a web GUI.

Component-based architecture (CBA)—not to be confused with web components, which are just one of the most recent implementations of CBA—existed before React. Such architectures generally tend to be easier to reuse, maintain, and extend than monolithic UIs. What React brings to the table is the use of pure JavaScript (without templates) and a new way to look at composing components.

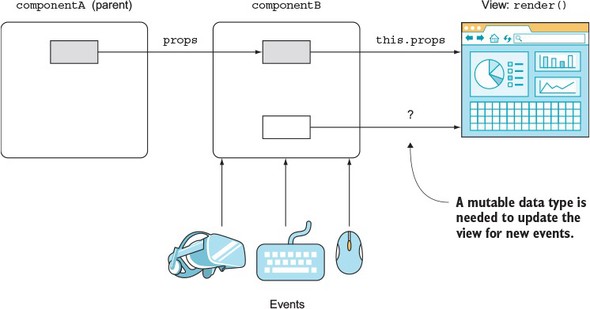

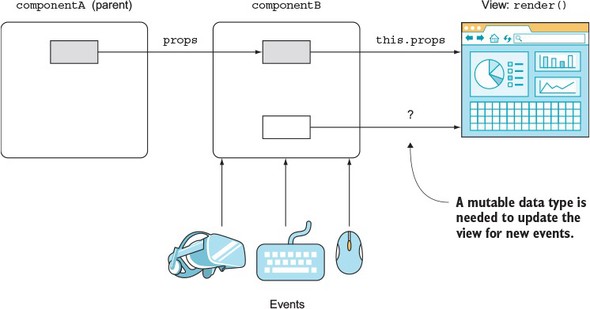

What problem does React solve? Looking at the last few years of web development, note the problems in building and managing complex web UIs for front-end applications: React was born primarily to address those. Think of large web apps like Facebook: one of the most painful tasks when developing such applications is managing how the views change in response to data changes.

Let’s refer to the official React website for more hints about the problem React addresses: “We built React to solve one problem: building large applications with data that changes over time.”[3] Interesting! We can also look at the history of React for more information. A discussion on the React Podcast[4] mentions that the creator of React—Jordan Walke—was solving a problem at Facebook: having multiple data sources update an autocomplete field. The data came asynchronously from a back end. It was becoming more and more complicated to determine where to insert new rows in order to reuse DOM elements. Walke decided to generate the field representation (DOM elements) anew each time. This solution was elegant in its simplicity: UIs as functions. Call them with data, and you get rendered views predictably.

React official website, “Why React?” March 24, 2016, http://bit.ly/2mdCJKM.

React Podcast, “8. React, GraphQL, Immutable & Bow-Ties with Special Guest Lee Byron,” December 31, 2015, http://mng.bz/W1X6.

Later, it turned out that generating elements in memory is extremely fast and that the actual bottleneck is rendering in the DOM. But the React team came up with an algorithm that avoids unnecessary DOM pain. This made React very fast (and cheap in terms of performance). React’s splendid performance and developer-friendly, component-based architecture are a winning combination. These and other benefits of React are described in the next section.

React solved Facebook’s original problem, and many large firms agreed with this approach. React adoption is solid, and its popularity is growing every month. React emerged from Facebook[5] and is now used not only by Facebook but also by Instagram, PayPal, Uber, Sberbank, Asana,[6] Khan Academy,[7] HipChat,[8] Flipboard,[9] and Atom,[10] to name just a few.[11] Most of these applications originally used something else (typically, template engines with Angular or Backbone) but switched to React and are extremely happy about it.

“Introduction to React.js,” July 8, 2013, http://mng.bz/86XF.

Malcolm Handley and Phips Peter, “Why Asana Is Switching to TypeScript,” Asana Blog, November 14, 2014, http://mng.bz/zXKo.

Joel Burget, “Backbone to React,” http://mng.bz/WGEQ.

Rich Manalang, “Rebuilding HipChat with React.js,” Atlassian Developers, February 10, 2015, http://mng.bz/r0w6.

Michael Johnston, “60 FPS on the Mobile Web,” Flipboard, February 10, 2015, http://mng.bz/N5F0.

Nathan Sobo, “Moving Atom to React,” Atom, July 2, 2014, http://mng.bz/K94N.

See also the JavaScript usage stats at http://libscore.com/#React.

Every new library or framework claims to be better than its predecessors in some respect. In the beginning, we had jQuery, and it was leaps and bounds better for writing cross-browser code in native JavaScript. If you remember, a single AJAX call taking many lines of code had to account for Internet Explorer and WebKit-like browsers. With jQuery, this takes only a single call: $.ajax(), for example. Back in the day, jQuery was called a framework—but not anymore! Now a framework is something bigger and more powerful.

Similarly with Backbone and then Angular, each new generation of JavaScript frameworks has brought something new to the table. React isn’t unique in this. What is new is that React challenges some of the core concepts used by most popular front-end frameworks: for example, the idea that you need to have templates.

The following list highlights some of the benefits of React versus other libraries and frameworks:

Many features make React simpler to work with than most other front-end frameworks. Let’s unpack these items one by one, starting with its simplicity.

The concept of simplicity in computer science is highly valued by developers and users. It doesn’t equate to ease of use. Something simple can be hard to implement, but in the end it will be more elegant and efficient. And often, an easy thing will end up being complex. Simplicity is closely related to the KISS principle (keep it simple, stupid).[12] The gist is that simpler systems work better.

React’s approach allows for simpler solutions via a dramatically better web-development experience for software engineers. When I began working with React, it was a considerable shift in a positive direction that reminded me of switching from using plain, no-framework JavaScript to jQuery.

In React, this simplicity is achieved with the following features:

Let’s cover these one by one.

First, React embraces declarative style over imperative. Declarative style means developers write how it should be, not what to do, step-by-step (imperative). But why is declarative style a better choice? The benefit is that declarative style reduces complexity and makes your code easier to read and understand.

Consider this short JavaScript example, which illustrates the difference between declarative and imperative programming. Let’s say you need to create an array (arr2) whose elements are the result of doubling the elements of another array (arr). You can use a for loop to iterate over an array and tell the system to multiply by 2 and create a new element (arr2[i]=):

var arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

arr2 = []

for (var i=0; i<arr.length; i++) {

arr2[i] = arr[i]*2

}

console.log('a', arr2)

The result of this snippet, where each element is multiplied by 2, is printed on the console as follows:

a [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

This illustrates imperative programming, and it works—until it doesn’t work, due to the complexity of the code. It becomes too difficult to understand what the end result is supposed to be when you have too many imperative statements. Fortunately, you can rewrite the same logic in declarative style with map():

var arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

arr2 = arr.map(function(v, i){ return v*2 })

console.log('b', arr2)

The output is b [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]; the variable arr2 is the same as in the previous example. Which code snippet is easier to read and understand? In my humble opinion, the declarative example.

Look at the following imperative code for getting a nested value of an object. The expression needs to return a value based on a string such as account or account.number in such a manner that these statements print true:

var profile = {account: '47574416'}

var profileDeep = {account: { number: 47574416 }}

console.log(getNestedValueImperatively(profile, 'account') === '47574416')

console.log(getNestedValueImperatively(profileDeep, 'account.number')

=== 47574416)

=== 47574416)

This imperative style literally tells the system what to do to get the results you need:

var getNestedValueImperatively = function getNestedValueImperatively(object, propertyName) { var currentObject = object var propertyNamesList = propertyName.split('.') var maxNestedLevel = propertyNamesList.length var currentNestedLevel for (currentNestedLevel = 0; currentNestedLevel < maxNestedLevel;

currentNestedLevel++) { if (!currentObject || typeof currentObject === 'undefined')

return undefined currentObject = currentObject[propertyNamesList[currentNestedLevel]] } return currentObject }

Contrast this with declarative style (focused on the result), which reduces the number of local variables and thus simplifies the logic:

var getValue = function getValue(object, propertyName) {

return typeof object === 'undefined' ? undefined : object[propertyName]

}

var getNestedValueDeclaratively = function getNestedValueDeclaratively(object,

propertyName) {

return propertyName.split('.').reduce(getValue, object)

}

console.log(getNestedValueDeclaratively({bar: 'baz'}, 'bar') === 'baz')

console.log(getNestedValueDeclaratively({bar: { baz: 1 }}, 'bar.baz')=== 1)

propertyName) {

return propertyName.split('.').reduce(getValue, object)

}

console.log(getNestedValueDeclaratively({bar: 'baz'}, 'bar') === 'baz')

console.log(getNestedValueDeclaratively({bar: { baz: 1 }}, 'bar.baz')=== 1)

Most programmers have been trained to code imperatively, but usually the declarative code is simpler. In this example, having fewer variables and statements makes the declarative code easier to grasp at first glance.

That was just some JavaScript code. What about React? It takes the same declarative approach when you compose UIs. First, React developers describe UI elements in a declarative style. Then, when there are changes to views generated by those UI elements, React takes care of the updates. Yay!

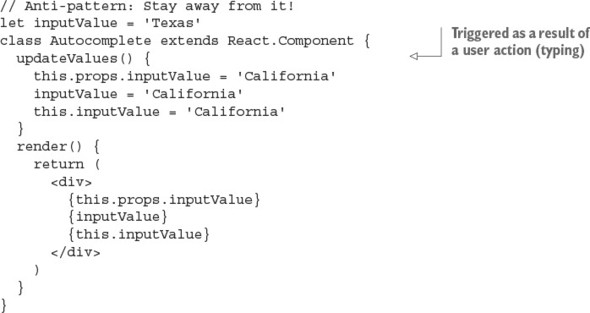

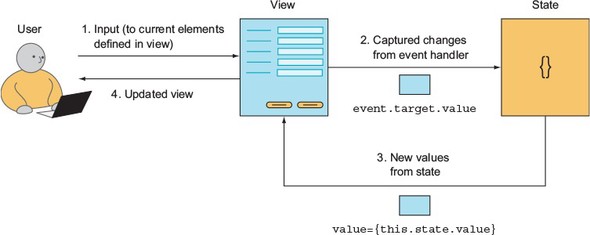

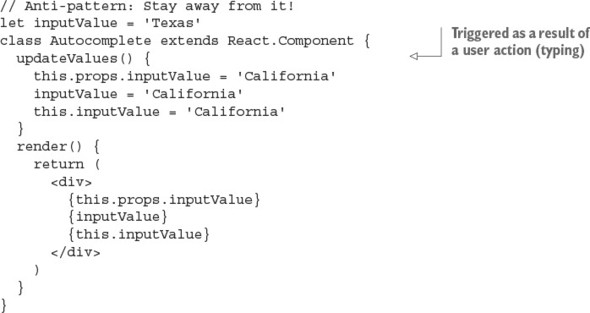

The convenience of React’s declarative style fully shines when you need to make changes to the view. Those are called changes of the internal state. When the state changes, React updates the view accordingly.

I cover how states work in chapter 4.

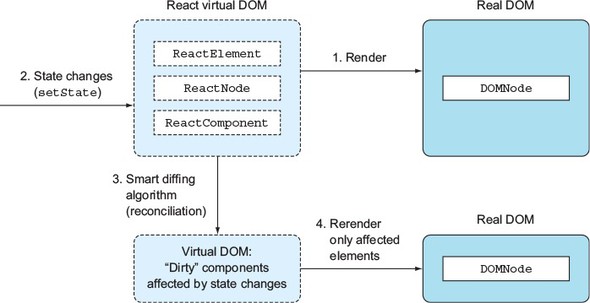

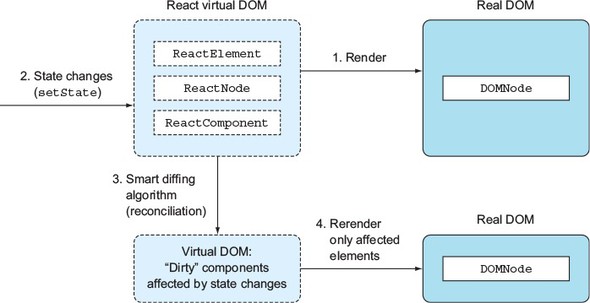

Under the hood, React uses a virtual DOM to find differences (the delta) between what’s already in the browser and the new view. This process is called DOM diffing or reconciliation of state and view (bringing them back to similarity). This means developers don’t need to worry about explicitly changing the view; all they need to do is update the state, and the view will be updated automatically as needed.

Conversely, with jQuery, you’d need to implement updates imperatively. By manipulating the DOM, developers can programmatically modify the web page or parts of the web page (a more likely scenario) without rerendering the entire page. DOM manipulation is what you do when you invoke jQuery methods.

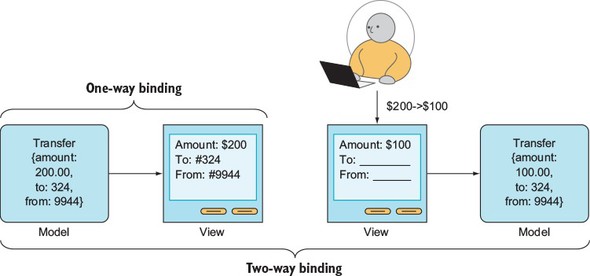

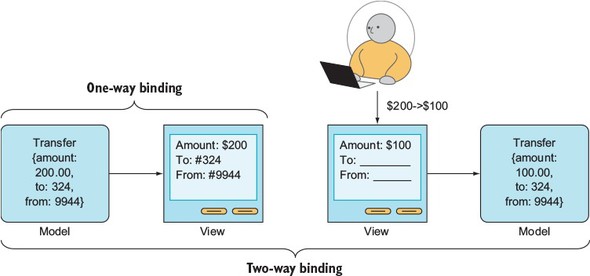

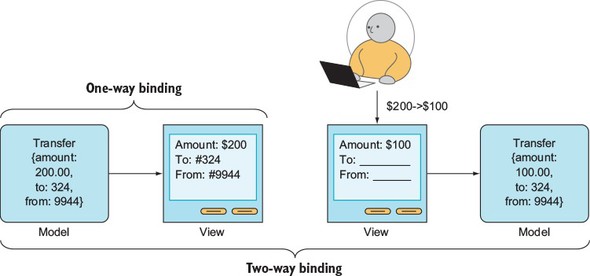

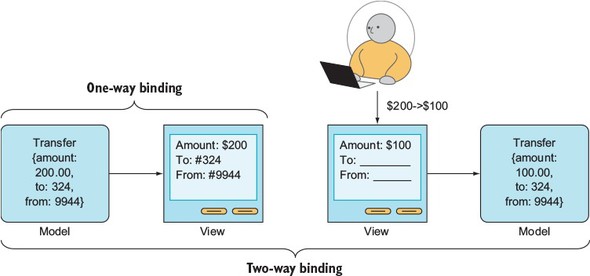

Some frameworks, such as Angular, can perform automatic view updates. In Angular, it’s called two-way data binding, which basically means views and models have two-way communication/syncing of data between them.

The jQuery and Angular approaches aren’t great, for two reasons. Think about them as two extremes. At one extreme, the library (jQuery) isn’t doing anything, and a developer (you!) needs to implement all the updates manually. At the other extreme, the framework (Angular) is doing everything.

The jQuery approach is prone to mistakes and takes more work to implement. Also, this approach of directly manipulating the regular DOM works fine with simple UIs, but it’s limiting when you’re dealing with a lot of elements in the DOM tree. This is the case because it’s harder to see the results of imperative functions than declarative statements.

The Angular approach is difficult to reason about because with its two-way binding, things can spiral out of control quickly. You insert more and more logic, and all of a sudden, different views are updating models, and those models update other views.

Yes, the Angular approach is somewhat more readable than imperative jQuery (and requires less manual coding!), but there’s another issue. Angular relies on templates and a DSL that uses ng directives (for example, ng-if). I discuss its drawbacks in the next section.

Component-based architecture[13] existed before React came on the scene. Separation of concerns, loose coupling, and code reuse are at the heart of this approach because it provides many benefits; software engineers, including web developers, love CBA. A building block of CBA in React is the component class. As with other CBAs, it has many benefits, with code reuse being the main one (you can write less code!).

What was lacking before React was a pure JavaScript implementation of this architecture. When you’re working with Angular, Backbone, Ember, or most of the other MVC-like front-end frameworks, you have one file for JavaScript and another for the template. (Angular uses the term directives for components.) There are a few issues with having two languages (and two or more files) for a single component.

The HTML and JavaScript separation worked well when you had to render HTML on the server, and JavaScript was only used to make your text blink. Now, single page applications (SPAs) handle complex user input and perform rendering on the browser. This means HTML and JavaScript are closely coupled functionally. For developers, it makes more sense if they don’t need to separate between HTML and JavaScript when working on a piece of a project (component).

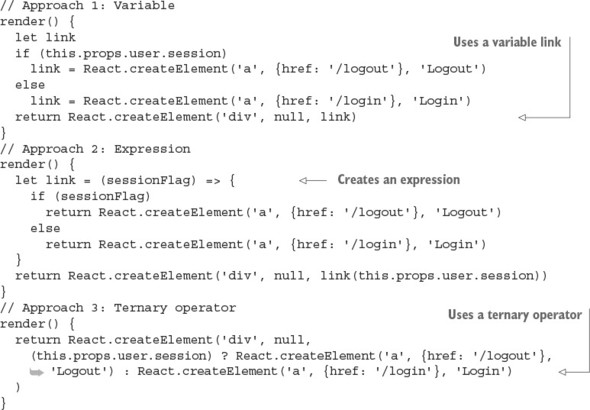

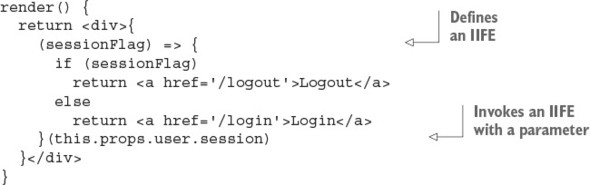

Consider this Angular code, which displays different links based on the value of userSession:

<a ng-if="user.session" href="/logout">Logout</a> <a ng-if="!user.session" href="/login">Login</a>

You can read it, but you may have doubts about what ng-if takes: a Boolean or a string. And will it hide the element or not render it at all? In the Angular case, you can’t be sure whether the element will be hidden on true or false, unless you’re familiar with how this particular ng-if directive works.

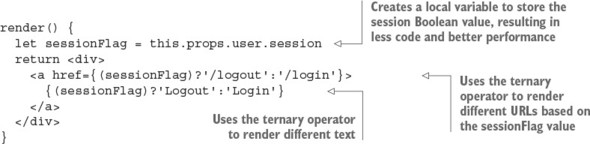

Compare the previous snippet with the following React code, which uses JavaScript if/else to implement conditional rendering. It’s absolutely clear what the value of user.session must be and what element (logout or login) is rendered if the value is true. Why? Because it’s just JavaScript:

if (user.session) return React.createElement('a', {href: '/logout'}, 'Logout')

else return React.createElement('a', {href: '/login'}, 'Login')

Templates are useful when you need to iterate over an array of data and print a property. We work with lists of data all the time! Let’s look at a for loop in Angular. As mentioned earlier, in Angular, you need to use a DSL with directives. The directive for a for loop is ng-repeat:

<div ng-repeat="account in accounts">

{{account.name}}

</div>

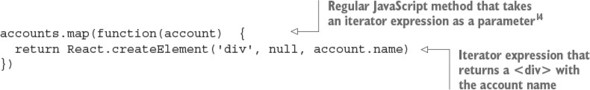

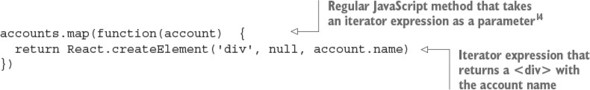

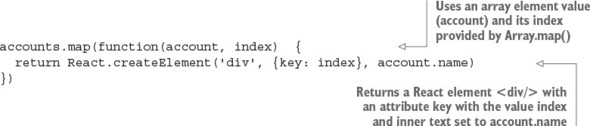

One of the problems with templates is that developers often have to learn yet another language. In React, you use pure JavaScript, which means you don’t need to learn a new language! Here’s an example of composing a UI for a list of account names with pure JavaScript:[14]

Imagine a situation where you’re making some changes to the list of accounts. You need to display the account number and other fields. How do you know what fields the account has in addition to name?

You need to open the corresponding JavaScript file that calls and uses this template, and then you have to find accounts to see its properties. So the second problem with templates is that the logic about the data and the description of how that data should be rendered are separated.

It’s much better to have the JavaScript and the markup in one place so you don’t have to switch between file and languages. This is exactly how React works; and you’ll see how React renders elements shortly in a Hello World example.

Separation of concerns generally is a good pattern. In a nutshell, it means separation of different functions such as the data service, the view layer, and so on. When you’re working with template markup and corresponding JavaScript code, you’re working on one functionality. That’s why having two files (.js and .html) isn’t a separation of concerns.

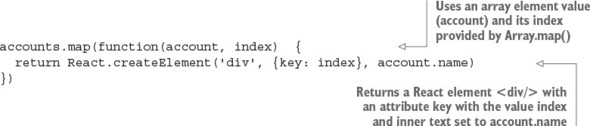

Now, if you want to explicitly set the method by which to keep track of items (for example, to ensure there are no duplicates) in the rendered list, you can use Angular’s track by feature:

<div ng-repeat="account in accounts track by account._id">

{{account.name}}

</div>

If you want to track by an index of the array, there’s $index:

<div ng-repeat="account in accounts track by $index">

{{account.name}}

</div>

But what concerns me and many other developers is, what is this magic $index? In React, you use an argument from map() for the value of the key attribute:

It’s worth noting that map() isn’t exclusive to React. You can use it with other frameworks because it’s part of the language. But the declarative nature of map() makes it and React a perfect pair.

I’m not picking on Angular—it’s a great framework. But the bottom line is that if a framework uses a DSL, you need to learn its magic variables and methods. In React, you can use pure JavaScript.

If you use React, you can carry your knowledge to the next project even if it’s not in React. On the other hand, if you use an X template engine (or a Y framework with a built-in DSL template engine), you’re locked into that system and have to describe yourself as an X/Y developer. Your knowledge isn’t transferable to projects that don’t use X/Y. To summarize, the pure JavaScript component-based architecture is about using discrete, well-encapsulated, reusable components that ensure better separation of concerns based on functionality without the need for DSLs, templates, or directives.

Working with many developer teams, I’ve observed another factor related to simplicity. React has a better, shallower, more gradual learning curve compared to MVC frameworks (well, React isn’t an MVC, so I’ll stop comparing them) and template engines that have special syntax—for example, Angular directives or Jade/Pug. The reason is that instead of using the power of JavaScript, most template engines build abstractions with their own DSL, in a way reinventing things like an if condition or a for loop.

React has a powerful abstraction of the document model. In other words, it hides the underlying interfaces and provides normalized/synthesized methods and properties. For example, when you create an onClick event in React, the event handler will receive not a native browser-specific event object, but a synthetic event object that’s a wrapper around native event objects. You can expect the same behavior from synthetic events regardless of the browser in which you run the code. React also has a set of synthetic events for touch events, which are great for building web apps for mobile devices.

Another example of React’s DOM abstraction is that you can render React elements on the server. This can be handy for better search engine optimization (SEO) and/or improving performance.

There are more options when it comes to rendering React components than just DOM or HTML strings for the server back end. We’ll cover them in section 1.5.1. And, speaking of the DOM, one of the most sought-after benefits of React is its splendid performance.

In addition to the necessary DOM updates, your framework may perform unnecessary updates, which makes the performance of complex UIs even worse. This becomes especially noticeable and painful for users when you have a lot of dynamic UI elements on your web page.

On the other hand, React’s virtual DOM exists only in the JavaScript memory. Every time there’s a data change, React first compares the differences using its virtual DOM; only when the library knows there has been a change in the rendering will it update the actual DOM. Figure 1.1 shows a high-level overview of how React’s virtual DOM works when there are data changes.

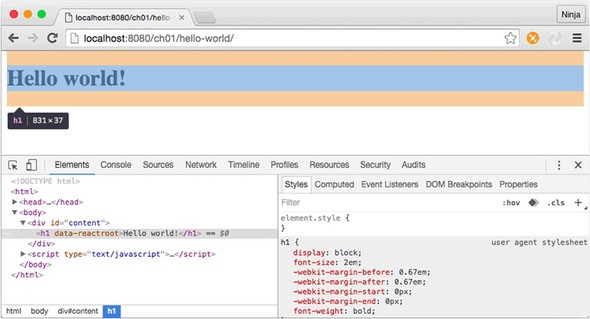

Ultimately, React updates only those parts that are absolutely necessary so that the internal state (virtual DOM) and the view (real DOM) are the same. For example, if there’s a <p> element and you augment the text via the state of the component, only the text will be updated (that is, innerHTML), not the element itself. This results in increased performance compared to rerendering entire sets of elements or, even more so, entire pages (server-side rendering).

If you like to geek out on algorithms and Big Os, these two articles do a great job of explaining how the React team managed to turn an O(n3) problem into an O(n) one: “Reconciliation,” on the React website (http://mng.bz/PQ9X) and “React’s Diff Algorithm” by Christopher Chedeau (http://mng.bz/68L4).

The added benefit of the virtual DOM is that you can do unit testing without headless browsers like PhantomJS (http://phantomjs.org). There’s a Jasmine (http://jasmine.github.io) layer called Jest (https://facebook.github.io/jest) that lets you test React components right on the command line!

Last, but not least, React is supported by the developers of a juggernaut web application called Facebook, as well as by their peers at Instagram. As with Angular and some other libraries, having a big company behind the technology provides a sound testing ground (it’s deployed to millions of browsers), reassurance about the future, and an increase in contribution velocity.

The React community is incredible. Most of the time, developers don’t even have to implement much of the code. Look at these community resources:

My personal anecdotal experience with open source taught me that the marketing of open source projects is as important to its wide adoption and success as the code itself. By that, I mean that if a project has a poor website, lacks documentation and examples, and has an ugly logo, most developers won’t take it seriously—especially now, when there are so many JavaScript libraries. Developers are picky, and they won’t use an ugly duckling library.

My teacher used to say, “Don’t judge a book by its cover.” This might sound controversial; but, sadly, most people, including software engineers, are prone to biases such as good branding. Luckily, React has a great engineering reputation backing it. And, speaking of book covers, I hope you didn’t buy this book just for its cover!

Of course, almost everything has its drawbacks. This is true with React, but the full list of cons depends on whom you ask. Some of the differences, like declarative versus imperative, are highly subjective. So, they can be both pros and cons. Here’s my list of React disadvantages (as with any such list, it may be biased because it’s based on opinions I’ve heard from other developers):

To continue with this introduction to React, let’s look at how it fits into a web application.

In a way, the React library by itself, without React Router or a data library, is less comparable to frameworks (like Backbone, Ember, and Angular) and more comparable to libraries for working with UIs, like template engines (Handlebars, Blaze) and DOM-manipulation libraries (jQuery, Zepto). In fact, many teams have swapped traditional template engines like Underscore in Backbone or Blaze in Meteor for React, with great success. For example, PayPal switched from Dust to Angular, as did many other companies listed earlier in this chapter.

You can use React for just part of your UI. For example, let’s say you have a load-application form on a web page built with jQuery. You can gradually begin to convert this front-end app to React by first converting the city and state fields to populate automatically based on the ZIP code. The rest of the form can keep using jQuery. Then, if you want to proceed, you can convert the rest of the form elements from jQuery to React, until your entire page is built on React. Taking a similar approach, many teams successfully integrated React with Backbone, Angular, or other existing front-end frameworks.

React is back-end agnostic for the purposes of front-end development. In other words, you don’t have to rely on a Node.js back end or MERN (MongoDB, Express.js, React.js, and Node.js) to use React. It’s fine to use React with any other back-end technology like Java, Ruby, Go, or Python. React is a UI library, after all. You can integrate it with any back end and any front-end data library (Backbone, Angular, Meteor, and so on).

To summarize how React fits into a web app, it’s most often used in these scenarios:

React works nicely with other front-end technologies, but it’s mostly used as part of single-page architecture because SPA seems to be the most advantageous and popular approach to building web apps. I cover how React fits into an SPA in section 1.5.2.

In some extreme scenarios, you can even use React only on the server as a template engine of sorts. For example, there’s an express-react-views library (https://github.com/reactjs/express-react-views). It renders the view server-side from React components. This server-side rendering is possible because React lets you use different rendering targets.

In versions 0.14 and higher, the React team split the library into two packages: React Core (react package on npm) and ReactDOM (react-dom package on npm). By doing so, the maintainers of React made it clear that React is on a path to become not just a library for the web, but a universal (sometimes called isomorphic because it can be used in different environments) library for describing UIs.

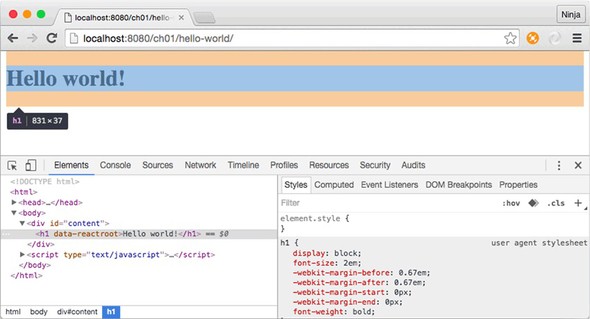

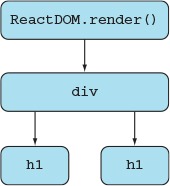

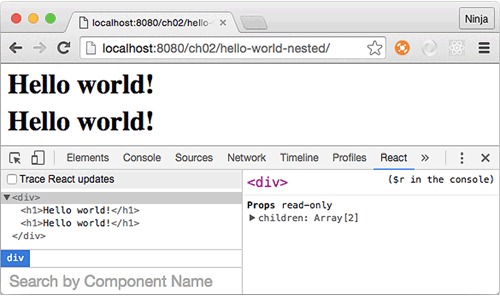

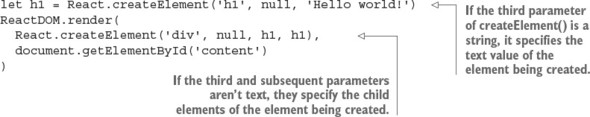

For example, in version 0.13, React had a React.render() method to mount an element to a web page’s DOM node. In versions 0.14 and higher, you need to include react-dom and call ReactDOM.render() instead of React.render().

Having multiple packages created by the community to support various rendering targets made this approach of separating writing components and rendering logical. Some of these modules are as follows:

In addition to the support of these libraries, the separation of React Core from ReactDOM makes it easier to share code between React and React Native libraries (used for native mobile iOS and Android development). In essence, when using React for web development, you’ll need to include at least React Core and ReactDOM.

Moreover, there are additional React utility libraries in React and npm. (Before React v15.5, some of them were part of React as React add-ons.[15] These utility libraries allow you to enhance functionality, work with immutable data (https://github.com/kolodny/immutability-helper), and perform testing.

See the version 15.5 change log with the list of add-ons and npm libraries: https://facebook.github.io/react/blog/2017/04/07/react-v15.5.0.html. See also the page on add-ons: https://facebook.github.io/react/docs/addons.html.

Finally, React is almost always used with JSX—a tiny language that lets developers write React UIs more eloquently. You can transpile JSX into regular JavaScript by using Babel or a similar tool.

As you can see, there’s a lot of modularity—the functionality of React-related things is split into different packages. This gives you power and choice, which is a good thing. No monolith or opinionated library dictates to you the only possible way to implement things. More on this in section 1.5.3.

If you’re a web developer reading this book, you probably use SPA architecture. Either you already have a web app built using this and want to reengineer it with React (brownfield), or you’re starting a new project from scratch (greenfield). Next, we’ll zoom in on React’s place in SPAs as the most popular approach to building web apps.

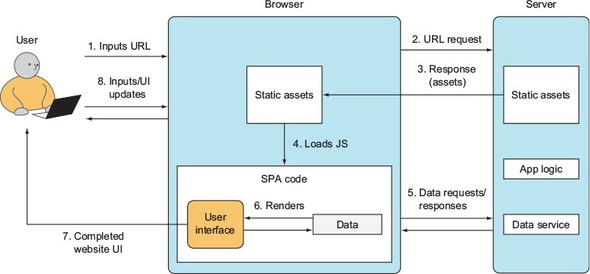

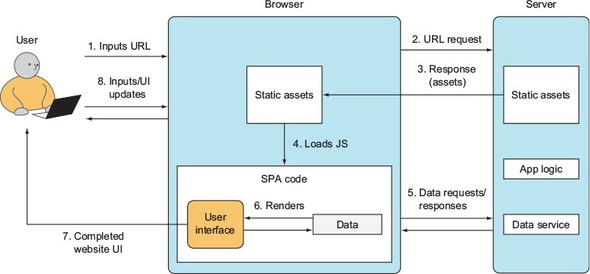

Another name for SPA architecture is thick client, because the browser, being a client, holds more logic and performs functions such as rendering of the HTML, validation, UI changes, and so on. Figure 1.2 is basic: it shows a bird’s-eye view of a typical SPA architecture with a user, a browser, and a server. The figure depicts a user making a request, and input actions like clicking a button, drag-and-drop, mouse hovering, and so on:

“What does it mean to hydrate an object?” Stack Overflow, http://mng.bz/uP25.

To summarize, in the SPA approach, most rendering for UIs happens on the browser. Only data travels to and from the browser. Contrast that with a thick-server approach, where all the rendering happens on the server. (Here I mean rendering as in generating HTML from templates or UI code, not as in rendering that HTML in the browser, which is sometimes called painting or drawing the DOM.)

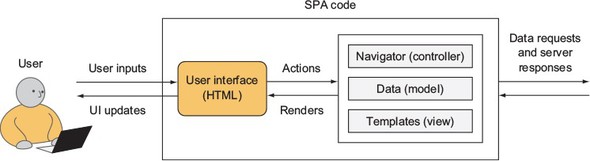

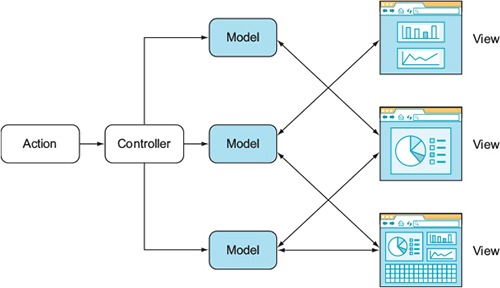

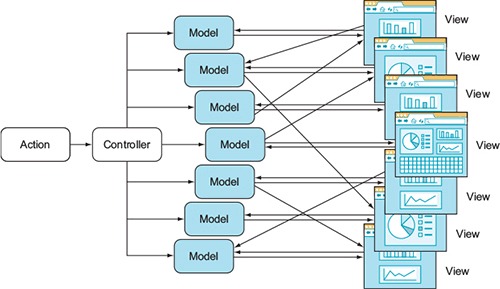

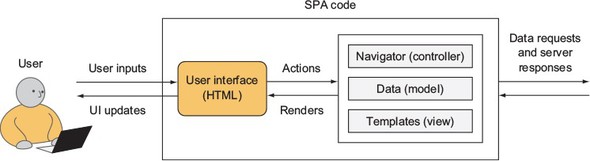

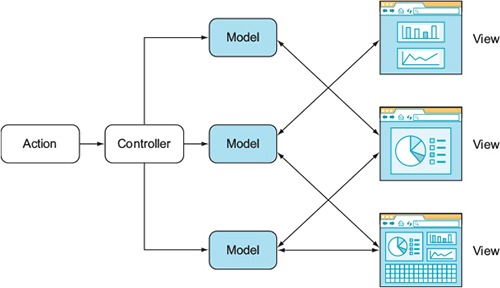

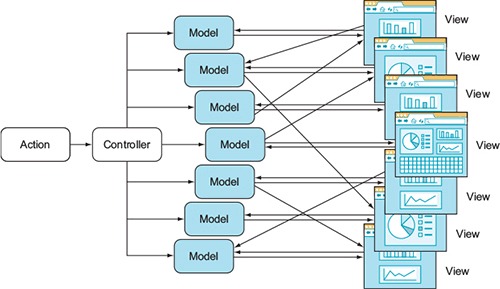

Note that the MVC-like architecture is the most popular approach, but it isn’t the only one. React doesn’t require you to use an MVC-like architecture; but, for the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that your SPA is using an MVC-like architecture. You can see its possible distinct parts in figure 1.3. A navigator or routing library acts as a controller of sorts in the MVC paradigm; it dictates what data to fetch and what template to use. The navigator/controller makes a request to get data and then hydrates/populates the templates (views) with this data to render the UI in the form of the HTML. The UI sends actions back to the SPA code: clicks, mouse hovers, keystrokes, and so on.

In an SPA architecture, data is interpreted and processed in the browser (browser rendering) and is used by the SPA to render additional HTML or to change existing HTML. This makes for nice interactive web applications that rival desktop apps. Angular.js, Backbone.js, and Ember.js are examples of front-end frameworks for building SPAs.

Different frameworks implement navigators, data, and templates differently, so figure 1.3 isn’t applicable to all frameworks. Rather, it illustrates the most widespread separation of concerns in a typical SPA.

React’s place in the SPA diagram in figure 1.3 is in the Templates block. React is a view layer, so you can use it to render HTML by providing it with data. Of course, React does much more than a typical template engine. The difference between React and other template engines like Underscore, Handlebars, and Mustache is in the way you develop UIs, update them, and manage their states. We’ll talk about states in chapter 4 in more detail. For now, think of states as data that can change and that’s related to the UI.

React isn’t a full-blown, front-end JavaScript framework. React is minimalistic. It doesn’t enforce a particular way of doing things like data modeling, styling, or routing (it’s non-opinionated). Because of that, developers need to pair React with a routing and/or modeling library.

For example, a project that already uses Backbone.js and the Underscore.js template engine can switch to Underscore for React and keep existing data models and routing from Backbone. (Underscore also has utilities, not just template methods. You can use these Underscore utilities with React as a solution for a clear declarative style.) Other times, developers opt to use the React stack, which consists of data and routing libraries created to be used specifically with React:

The ecosystem of libraries for React is growing every day. Also, React’s ability to describe composable components (self-contained chunks of the UI) is helpful in reusing code. There are many components packaged as npm modules. Just to illustrate the point that having small composable components is good for code reuse, here are some popular React components:

Then there’s JSX, which is probably the most frequent argument for not using React. If you’re familiar with Angular, then you’ve already had to write a lot of JavaScript in your template code. This is because in modern web development, plain HTML is too static and is hardly any use by itself. My advice: give React the benefit of the doubt, and give JSX a fair run.

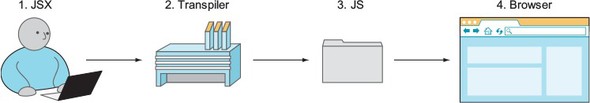

JSX is a little syntax for writing React objects in JavaScript using <> as in XML/HTML. React pairs nicely with JSX because developers can better implement and read the code. Think of JSX as a mini-language that’s compiled into native JavaScript. So, JSX isn’t run on the browser but is used as the source code for compilation. Here’s a compact snippet written in JSX:

if (user.session) return <a href="/logout">Logout</a> else return <a href="/login">Login</a>

Even if you load a JSX file in your browser with the runtime transformer library that compiles JSX into native JavaScript on the run, you still don’t run the JSX; you run JavaScript instead. In this sense, JSX is akin to CoffeeScript. You compile these languages into native JavaScript to get better syntax and features than that provided by regular JavaScript.

I know that to some of you, it looks bizarre to have XML interspersed with JavaScript code. It took me a while to adjust, because I was expecting an avalanche of syntax error messages. And yes, using JSX is optional. For these two reasons, I’m not covering JSX until chapter 3; but trust me, it’s powerful once you get a handle on it.

By now, you have an understanding of what React is, its stack, and its place in the higher-level SPA. It’s time to get your hands dirty and write your first React code.

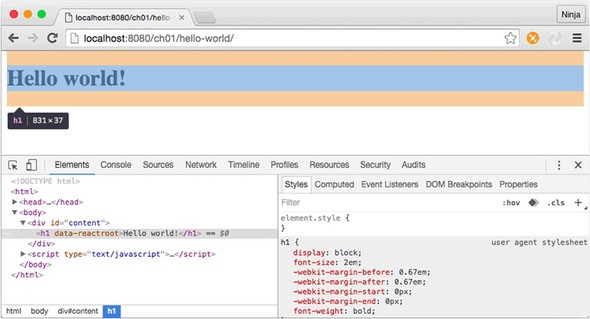

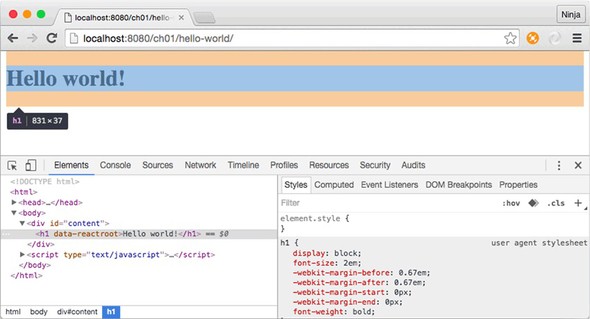

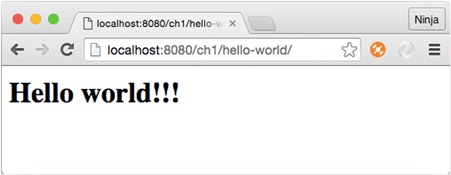

Let’s explore your first React code—the quintessential example used for learning programming languages—the Hello World application. (If we don’t do this, the gods of programming might punish us!) You won’t be using JSX yet, just plain JavaScript. The project will print a “Hello world!!!” heading (<h1>) on a web page. Figure 1.4 shows how it will look when you’re finished (unless you’re not quite that enthusiastic and prefer a single exclamation point).

Although most React developers write in JSX, browsers will only run standard JavaScript. That’s why it’s beneficial to be able to understand React code in pure JavaScript. Another reason we’re starting with plain JS is to show that JSX is optional, albeit the de facto standard language for React. Finally, preprocessing JSX requires some tooling.

I want to get you started with React as soon as possible without spending too much time on setup in this chapter. You’ll perform all the necessary setup for JSX in chapter 3.

The folder structure of the project is simple. It consists of two JavaScript files in the js folder and one HTML file, index.html:

/hello-world

/js

react.js

react-dom.js

index.html

The two files in the js folder are for the React library version 15.5.4:[17] react-dom.js (web browser DOM renderer) and react.js (React Core package). First, you need to download the aforementioned React Core and ReactDOM libraries. There are many ways to do it. I recommend using the files provided in the source code for this book, which you can find at www.manning.com/books/react-quickly and https://github.com/azat-co/react-quickly/tree/master/ch01/hello-world. This is the most reliable and easiest approach, because it doesn’t require a dependency on any other service or tool. You can find more ways to download React in appendix A.

v15.5.4 is the latest as of this writing. Typically, major releases like 14, 15, and 16 incorporate significant differences, whereas minor releases like 15.5.3 and 15.5.4 have fewer breaking changes and conflicts. The code for this book was tested for v15.5.4. The code may work with future versions, but I can’t guarantee that it will work because no one knows what will be in the future versions—not even the core contributors.

Prior to version 0.14, these two libraries were bundled together. For example, for version 0.13.3, all you needed was react.js. This book uses React and React DOM version 15.5.4 (the latest as of this writing) unless noted otherwise. For most of the projects in part 1, you’ll need two files: react.js and react-com.js. In chapter 8, you’ll need prop-types (www.npmjs.com/package/prop-types), which was part of React until version 15.5.4 but is now a separate module.

After you place the React files in the js folder, create the index.html file in the hello-world project folder. This HTML file will be the entry point of the Hello World application (meaning you’ll need to open it in the browser).

The code for index.html is simple and starts with the inclusion of the libraries in <head>. In the <body> element, you create a <div> container with the ID content and a <script> element (that’s where the app’s code will go later), as shown in the following listing.

Why not render the React element directly in the <body> element? Because doing so can lead to conflict with other libraries and browser extensions that manipulate the document body. In fact, if you try attaching an element directly to the body, you’ll get this warning:

Rendering components directly into document.body is discouraged...

This is another good thing about React: it has great warning and error messages!

React warning and error messages aren’t part of the production build, in order to reduce noise, increase security, and minimize the distribution size. The production build is the minified file from the React Core library: for example, react.min.js. The development version with the warnings and error messages is the unminified version: for example, react.js.

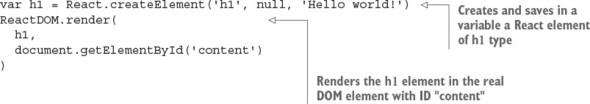

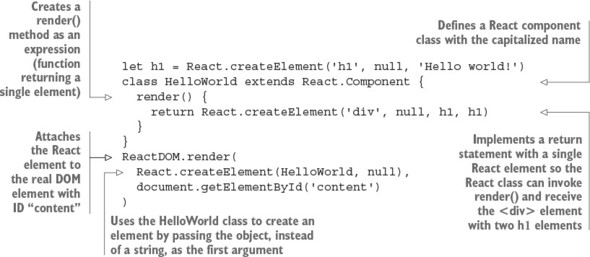

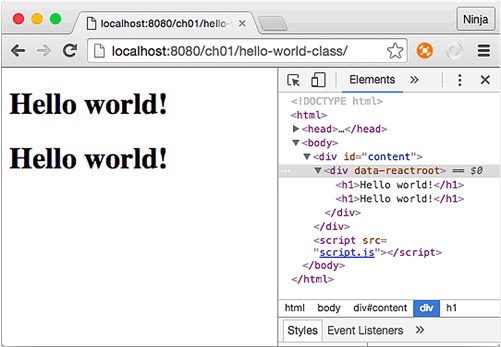

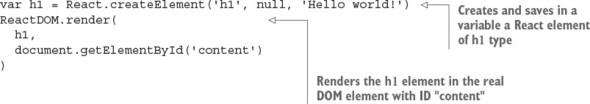

By including the libraries in the HTML file, you get access to the React and ReactDOM global objects: window.React and window.ReactDOM. You’ll need two methods from those objects: one to create an element (React) and another to render it in the <div> container (ReactDOM), as shown in listing 1.2.

To create a React element, all you need to do is call React.createElement(element-Name, data, child) with three arguments that have the following meanings: