Chapter 7. Decision-Making and Problem Solving: Enter Consciousness Stage Left

Up until now, most of the processes I’ve introduced so far, like attentional shifts and representing 3-D space, occur automatically, even if influenced by consciousness. In contrast, this chapter focuses on the very deliberate and conscious process of decision-making and problem-solving. Relative to other processes, this is one that you’re the most aware of and in control of. Right now I’m pretty sure that you’re thinking about the fact that you’re thinking about it.

We will focus on how we, as decision-makers, define where we are now and our goal state, and make make decisions to get us closer to our desired goal. Designers rarely think in these terms but I hope to change that.

What is my problem (definition)?

When you’re problem solving and decision making, you have to answer a series of questions. The first one is “What is my problem?” I don’t mean that you’re beating yourself up — I mean what is the problem you’re trying to solve: where are you now (current state) and where do you want to be (goal state).

Figure 7.1 People searching for clues in an escape room.

If you’ve ever experienced an Escape Room, an adventure game where you have to solve a series of riddles as quickly as possible to get out of a room. While getting unlocking the door may be your ultimate goal, there are sub-goals you’ll need to accomplish before that (e.g., finding the key) in order to get to your end goal. Sub-goals like finding a lost necklace, which you’ll need for your next sub-goal of opening a locked box, for instance (I’m making these up; no spoiler alerts here!).

Chess is another example of building sub-goals within larger goals. Ultimate goal: checkmate the opponent’s king. As the game progresses, however, you’ll need to create sub-goals to help you reach your ultimate goal. Your opponent’s king is protected by his queen and a bishop, so a sub-goal (to the ultimate goal of putting the opponent’s king into checkmate) could be eliminating the bishop. To do this, you may want to use your own bishop, which then necessitates another sub-goal of moving a pawn out of the way to free up that piece. Your opponent’s moves will also trigger new sub-goals for you — such as getting your queen out of a dangerous spot, or transforming a pawn by moving it across the board. In each of these instances, sub-goals are necessary to reach our desired end goal.

How might problems be framed differently?

Remember when we talked about experts and novices in the last chapter, and the unique words each group uses? When it comes to decision-making, experts and novices are often thinking very differently, too.

Let’s consider buying a house, for example. The novice home buyer might be thinking “What amount of money do we need to offer in order to be the bid the owner will accept?” Experts, however, might be thinking several more things: Can this buyer qualify for a loan? What is their credit score? Have they had any prior issues with credit? Do the buyers have the cash needed for a down payment? Will this house pass an inspection? What are the likely repairs that will need to be made before the buyers might accept the deal? Is this owner motivated to sell? Is the title of the property free and clear of any liens or other disputes?

So while the novice home buyer might frame the problem as just one challenge (convincing the buyer to sell at a specific price), the expert is thinking about many other things as well (e.g., a “clean” title, building inspection, credit scores, seller motivations, etc.). From these different perspectives, the problem definition is very different, and the decisions they make and actions they might take will also likely be very different.

In many cases, novices (whether first-time home buyers or college applicants or AirBnB renters) don’t define the problem that they really need to solve because they don’t understand all the complexities and decisions they need to make. Their knowledge of the problem might be very simplistic relative to what really happens.

This is why the first thing we need to understand is how our customer defines the problem. Then, we have an indication of what they think they need to do to solve that problem. As product and service designers, we need to meet them there, and over time, help to redirect them to what their actual (and likely more complex) problem is and the decisions they have to make along the way. This is known as redefining the problem space.

Figure 7.2: Williams Sonoma blenders

Sidenote: Framing and defining the problem are very different, but both apply to this section. To boost a product’s online sales, you may place it in between two higher- and lower-priced items. You will have successfully framed your product’s pricing. Instead of viewing it on its own, as a $300 blender, users will now see it as a “middle-of-the-road” option, not too cheap but not $400, either. As a consumer, be aware of how the art of framing a price can influence your decision-making skills. And as a designer, be aware of the power of framing.

Mutilated Checkerboard Problem

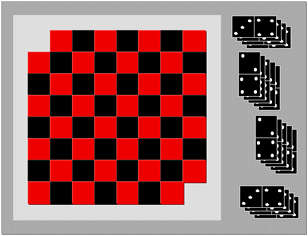

Figure 7.3: Mutilated Checkerboard

A helpful example of redefining a problem space comes from the so-called “mutilated checkerboard problem” as defined by cognitive psychologists Kaplan and Simon. The basic premise is this: Imagine you have a checkerboard. (If you’re in the U.S., you’re probably imagining intermittent red and black squares; if in the U.K., you might call this a chessboard, with white and black squares. Either version works in this example.) It’s a normal checkerboard, except for the fact that you’ve taken away the two opposite black corner squares away from the board, leaving you with 62 squares instead of 64. You also have a bunch of dominoes, which cover two squares each.

Your challenge: Arrange 31 dominoes on the checkerboard such that each domino lies across its own pair of red/black squares (no diagonals).

Moving around the problem space: When you hand someone this problem, they inevitably start putting dominoes down to solve it. Near the end of that process they inevitably get stuck, and try repeating the process. (If you are able to solve the problem without breaking the dominoes — be sure to send me your solution!)

The problem definition challenge: The problem is logically unsolvable. If every domino has to go on one red and one black square, and we no longer have an even number of red and black squares on the board (since we removed two black squares and no red squares). To the novice, the definition of the problem, and the way to move around in the problem space, is to lay out all the dominoes and figure it out. Each time they put down a domino they believe you are getting closer to the end goal. They likely calculated that since there are now 62 squares, and 31 dominoes, and each domino covers two spaces, the math works. An expert, however, instantly knows that you need equal numbers of red and black squares to make this work, and wouldn’t even bother to try and figure it out.

It’s an example of how experts can approach a problem one way and novices another. In this case, we saw how novices – after considerable frustration – redefined the problem. As product and service designers, if our challenge was to redefine the problem for novices in this instance, it would involve moving novices from holding their original problem definition (i.e., 62 squares = 31 x 2 dominos, and I have to place the dominoes on squares to figure this out) to a more sophisticated representation (i.e., acknowledging that you need an even number of red and black squares to solve this problem, and therefore there is no need to touch the dominos).

Finding the yellow brick road to problem resolution

I’ve mentioned moving around in the problem space. Let’s look at that component more closely.

First, it’s really important that as product or service designers, that we make no assumptions about what the problem space looks like for our users. As experts in the problem space, we know all the possible moves around the problem space that can be taken, and it often seems obvious what decisions need to be made and needs to be done. That same problem may look very different to our more novice users. Conversely, they might have a more sophisticated perspective on the problem than we initially anticipated.

In games like chess, it’s very clear to all parties involved what their possible moves are, if not all the consequences of their moves. That’s why we love games, isn’t it? In other realms, like getting health care or renting an apartment, the steps aren’t always so clear. As designers of these processes, we need to learn what our audiences see as their “yellow brick road.” What do they think the path is that will take them from their beginning state to their goal state? What do they see as the critical decisions to make? The road they’re envisioning may be very different from what an expert would envision, or what is even possible. But once we understand their perspective, we can work to gradually morph their novice mental models into a more educated one so that they make better decisions and understand what might be coming next.

When you get stuck en route: Sub-goals

We’ve talked about problem definition for our target audiences, but what about when they get stuck? How do they get around the things that may block them (“blockers”)? Many users see their end goal, but what they don’t see, and what we product and service designers can help them see, are the sub-goals they must have, and the steps, options, possibilities, for solving those sub-goals.

One way to get around blockers is through creating sub-goals, like those we discussed in the Escape Room example. You realize that you need a certain key to unlock the door. You can see that the key is in a glass box with a padlock on it. Your new sub-goal is getting the code to the padlock (to unlock the glass box, to get the key, to unlock the door).

We can also think of these sub-goals in terms of questions the user needs to answer. To lease a car, the customer will need to answer many sub-questions (e.g., How old are you?, How is your credit?, Can you afford the monthly payments?, Can you get insurance?) before the ultimate question (i.e., Can I lease this car?) can be answered. In service design, we want to address all of these potential sub-goals and sub-questions for our user so they feel prepared for what they’re going to get from us. It’s important that we address these micro-questions in a logical progression.

Ultimately, you as a product or service designer need to understand:

- 1. The actual steps to solve a problem or make a decision.

- 2. What your audience thinks the problem or decision is and how to solve it.

- 3. The sub-goals your audience creates in an attempt to get around “blockers.”

- 4. How to help the target audience shift their thinking from that of a novice to that of an expert in the field (changing their view of the problem space and sub-goals) to be more successful.

We almost always make decisions at two levels: A very logical, rational “Does this make sense?” level (which is sometimes described as “System 2,” or “conscious decisions”), and a much more emotional level (you may have heard references to “System 1,” the “lizard brain,” or “midbrain”). The last chapter in this section covers emotions and how emotions and decision-making are inherently intertwined.