Chapter 20: How To Make a Better Human

Growing up, I remember watching reruns of a 1970’s TV show about a NASA pilot who had a terrible crash, but according to the plot, the government scientists said “we can rebuild him, we have the technology” and he became “The Six Million Dollar Man” (now equivalent of about $40 million). With one eye with exceptional zoom vision, and one arm and two legs that were bionic he could run 60 miles per hour and perform great feats. In the show he used his superhuman strength as a spy for good.

It was one of the first mainstream shows that demonstrated what might be accomplished if you seamlessly bring together technology with humans. I’m not sure that it might have been as commercially viable if they called the show “The Six Million Dollar Cyborg,” but that’s really what he was – a human - machine combination. It was interesting, but far-off science TV make believe.

But today we have new possibilities with the resurgence and hype surrounding Artificial Intelligence and machine learning. I’m sure if you are in the product management, product design or innovation space you’ve heard all kinds of prognostications and visions about what might be possible and I’d like to bring together what might be the most powerful combination: thinking about human computational styles and supporting them with machine learning equipped experiences to create not the physical mental prowess of the Six Million Dollar Man, but the mental prowess that they never explored in the TV show.

Symbolic Artificial Intelligence and the AI Winter

I’m not sure if you are aware, but as I write we are in at least the second cycle of such hype and promise surrounding artificial intelligence. In the 1950’s and 1960’s, Alan Turing suggested that mathematically, 0’s and 1’s could represent any type of mathematical deduction, suggesting that computers could any formal reasoning. From there, scientists in neurobiology and information processing started to wonder, given the similarity of brain neurons ability to fire an action potential, or not (effectively a 1 or 0), if there might be the possibility of creating an artificial brain, and reasoning. Turing proposed the Turing test: essentially that if you could pass questions through to some entity, and the entity would provide answers back, and the humans couldn’t distinguish between the artificial and real human, that that artificial system passed, and could be considered artificial intelligence.

From there others like Herb Simon, Alan Newell and Marvin Minsky started to look at intelligent behavior that could be formally represented and worked on how “expert systems” could be built up with understanding of the world. Their artificial intelligence machines tackled some basic language tasks, games like checkers, and learning to do some analogical reasoning. There were bold predictions that within a generation the “problem of AI would largely be solved”.

Unfortunately, their approach showed promise in some fields but great limits in others, in part, because their approach focused on symbolic processing, very high-level reasoning, logic, and problem solving. This symbolic approach to thinking did find success in other areas including semantics, language and cognitive science, though focused much more on understanding human intelligence and than building artificial intelligence.

By the 1970’s in the academic world money for artificial intelligence dried up, and there was what was called the “AI Winter” – going from the amazing promise of the 1950’s to real limitations in the 1970’s.

Artificial Neural Networks and Statistical Learning

Very different approaches to artificial intelligence and the notion of creating an “artificial brain” started to be considered in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Scientists in a divergent set of fields composing cognitive science (psychology, linguistics, computer science), particularly David Rumelhart and James McClelland looked at this from a very different “sub-symbolic” approach. Perhaps rather than trying to build representations that were used by humans, we could instead build systems like brains – that had many individual processes (like neurons) that could affect one another with inhibition or excitation (like neurons) and have “back propagation” which changed the connections between the artificial neurons depending on whether the output of the system was correct.

This approach was radically different than the one above because: (a) it was a much more “brain-like” parallel distributed process (PDP), in comparison to a series of computer commands, (b) it focused much more on statistical learning, and (c) the programmers didn’t explicitly provide the information structure, but rather sought to have the PDP learn through trial and error and adjust its weights between its artificial neurons.

These PDP models had interesting successes in natural language processing and perception. Unlike the symbolic efforts in the first wave, this group did not make any assumptions about how these machine learning systems would represent the information. These systems are the underpinnings of Google Tensorflow, and Facebook Torch. It is this type of parallel process that is responsible for today’s self driving cars and voice interfaces.

With new incredible power in your mobile phone, and in the cloud, these systems have the computing power Newell and Simon likely dreamed of having. And while these systems have made great strides in natural language processing and image processing they are still far from perfect.

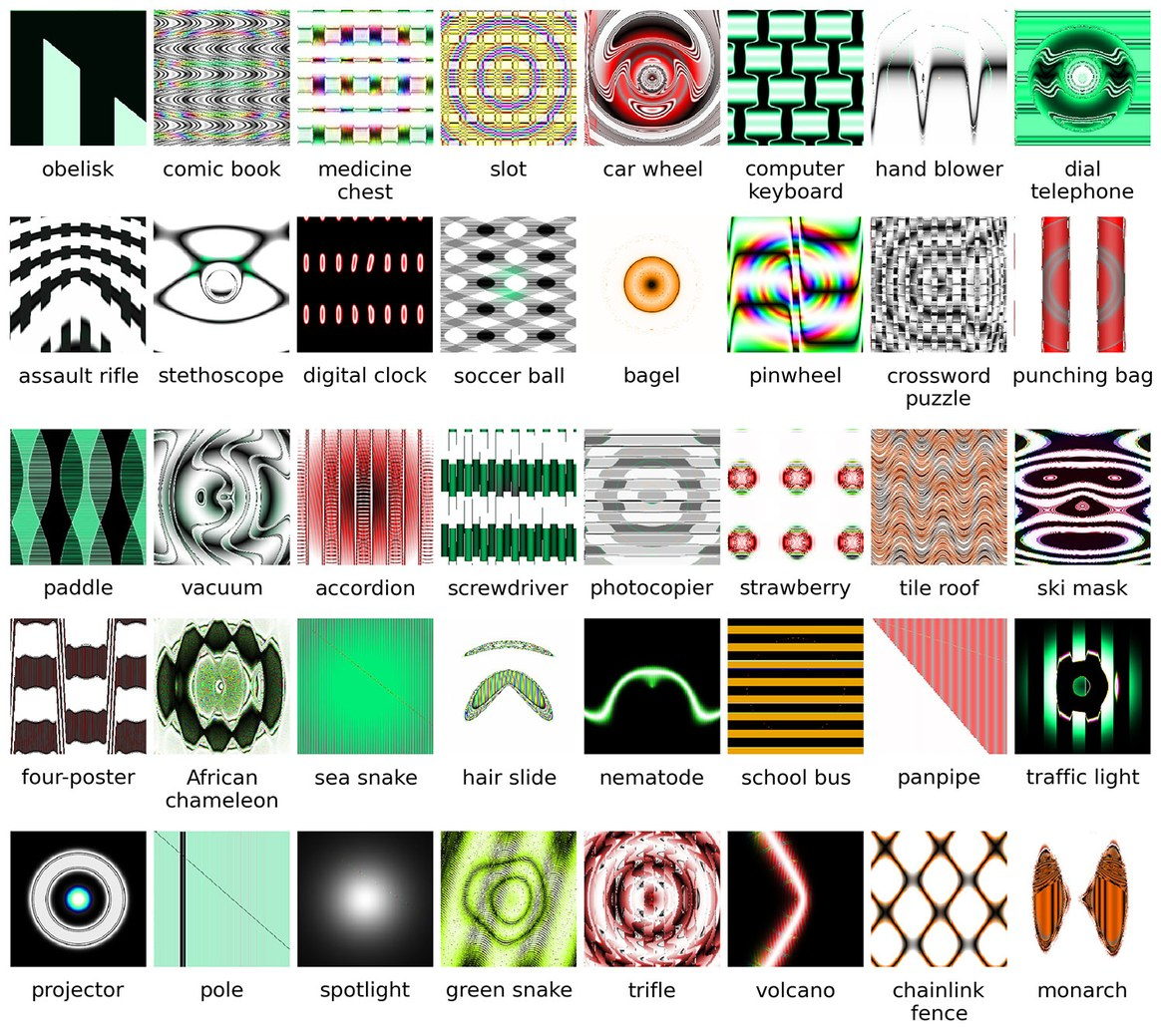

20.1

There have been many breathless prognostications about the power of AI and its unstoppable intelligence. While these systems have been getting better, they are highly dependent on having the data to train the system, and clearly as the above shows, have their limitations.

I didn’t say that Siri!

You may have your own experiences with how voice commands can on one hand be incredibly powerful, but on the other have significant limitations. Their ability to recognize any language has been impressive. This is a hard problem and they have shown real ability to do so. We put these systems to the test studying Apple Siri, Google Assistant, Amazon Alexa, Microsoft Cortana and Hound. Using a Jeopardy-like setup we asked participants to create a command or question to get an answer (e.g., Cincinnati, tomorrow, weather) for which participants might say “Hey Siri, what is the weather tomorrow in Cincinnati?).

To make a long story short, we found that these systems were quite good at answering basic facts (e.g., weather, capital of a country), but had real trouble with two very natural human abilities. First, we can put together ideas easily (e.g., population, country with Eiffel Tower – which we know is France). When we asked these systems a question like “What is the population of the country with the Eiffel tower?”, they generally produced the population of Paris or just gave an error. Second, if we followed up: “What is the weather in Cincinnati” [machine answers], “How about the next day?”, they were generally unable to follow the thread of the conversation.

In addition, we found significant preference for the AI systems that responded in the most humanistic way even if they got something incorrect or were unable to answer (e.g., “I don’t know how to answer that yet.”). When it addressed the participants in the way they addressed it, they were most satisfied.

But is Siri really smart? Intelligent? It can add a reminder and turn on music, but you can’t ask it if it is a good idea to purchase a certain car, or how to get out of an escape room. It has limited, machine-learning-based answers. It is not “intelligent” in a way that would pass the Turing test.

The six minds and Artificial Intelligence

So interestingly, the first wave of AI was known for its strength in performing analogies and reasoning (memory, decision making and problem solving), and the more recent approach has been much more successful with voice and image recognition (vision, attention, language). The systems that provided more human-like responses were favored (emotion).

I hope you are seeing where I am headed. The current systems are starting to show the limitations of a brute force, purely statistical, sub-symbolic representation. While these systems are without a doubt amazingly powerful and fantastic for certain problems, no amount of faster chips or new training regimens will achieve the goals of artificial intelligence sought set in the 1950’s.

If more speed isn’t the answer, what is? Some of the most prominent scientists in the machine learning and AI fields are suggesting we take another look at the human mind. If studying the individual- and group-neuron level achieved this success in the perceptual realm, perhaps considering other levels of representation will provide even more success at the symbolic level with: vision/attention, wayfinding and representations of space, language and semantics, memory and decision making.

Just like traditional product and service design, you might expect that I would encourage those building AI systems to consider the representations you using as inputs and outputs, and test representations that are at different symbolic levels of representation (e.g., word-level, semantic-level), rather than purely perceptual levels (e.g., pixels, phonemes, sounds).

I get by with a little help from my (AI) friends

While AI/ML researchers seek to produce independently intelligent systems, it is very likely that more near-term successes can be achieved using artificial intelligence and machine learning tools as cognitive support tools. We have many of these already right on our mobile devices. We can remember things using reminders, translate street signs with our smartphones, get help with directions from mapping programs, and encouragement to achieve goals with programs that count calories, help us save, or get more sleep or exercise.

In our studies of voice activated systems today however, the number one challenge we saw was the difference between the language the system and users used and when the assistance was provided relative to when it was needed. As you begin to build things that allow your customers or workers do things faster and more easily by augmenting their cognitive abilities, the Six Minds should be an excellent framing of how ML/AI can support human endeavors.

Vision/Attention: AI tools, particularly with cameras could easily help to draw attention to the important parts of a scene. I could imagine both drawing relevant information into focus (e.g., what form elements are unfinished), or if it knows what you are seeking highlighting relevant words on a page or in scene. Any number of possibilities come to mind. When entering a hotel room for the first time people want to know where the light switches are, how to change the temperature, and where the outlets are to recharge their devices. Imagine looking through your glasses and having these things highlighted in the scene.

Wayfinding: Given successes with Lidar and automated cars, it could definitely be the case that the heads-up display I just mentioned could also bring into attention the highway exit you need to choose, that tucked away subway entrance, or the store you might be seeking in the mall. Much like game playing, it could show two views – the immediate scene in front of you, and a birds-eye map of the area and where you are in that space.

Memory/Language: We work with a number of major retailers and financial institutions who seek to provide personalization in their digital offerings. By getting evidence through search terms, click streams, communications and surveys, one could easily see the organization and the terminology of the system being tailored to that individual. Video is a good example where you might be just starting out and need a good camera for your YouTube videos, where others might be seeking specific types of ENG (News) cameras with 4:2:2 color, etc. Neither group really wants to see the other’s offerings in the store, and the language and detail each need would be very different.

Decision Making/Problem Solving: We have discussed the fact that problem solving is really a process of breaking down large problems into their component parts and solving each of these sub-problems. Along each step you have to make decisions about your next move. Problems like buying a printer with many different dimensions and micro-decisions is a good example. A design might want a larger format printer with very accurate color. A law firm might want legal paper handling and good multi-user functionality and the ability to bill the printing back to the client automatically, while a parent with school-aged kids might want a quick durable color printer all family members can use. By asking a little of the needs of the individual, and supporting each of the micro decisions along the way (e.g., What is the price? How much is toner? Can it print on different sizes of paper? Do I need double-sided printing? What reviews are there from families?). Having the ML/AI intuit the types of goals the individual might have, and the location in the problem space, might suggest exactly what that person should be presented with, and what they don’t need at this time.

Emotion: Perhaps one of the most interesting possibilities is that increasingly accurate systems for detecting facial expressions, movement and speech patterns can detect the user’s emotional state, which could be used to moderate the amount presented on a screen, the words used, and consideration of the approach the user is taking (perhaps they are overwhelmed and want a simpler route to an answer).

Endless possibilities abound, but they all revolve around what the individual is trying to accomplish, how they think they can accomplish it, what they are looking for right now, the words they expect, how they believe they can interact with the system and where they are looking. I hope that framing the problem in terms of the Six Minds will allow you and your team to exceed all previous attempts at satisfying your users with a brilliant experience. I hope you can heighten every one of your user’s cognitive processes in reality, just as the team augmented the physical capabilities for the fictional Six Million Dollar Man.

Concrete recommendations:

- ● Suggest different ways of training AI systems to explicitly train for semantics (rather than skipping this)

- ● Consider explicitly training specific types of syntactic patterns, which were less common in the corpus you collected

- ● Think about how you want to augment cognition (e.g., directing attention, encouraging certain kinds of interactions, providing information persuasively, etc.).