Chapter 9. User Research: Contextual Interviews

Market research has taken many forms through the years. Some may immediately think of the kind of focus group shown in the TV show “Mad Men.” Others may think of a large surveys, and still others may have conducted empathy research when taking a Design Thinking approach to product and service design.

While focus groups and surveys can be great tools to get to what people are saying, and maybe some of what they are doing, they just don’t get to the why behind these behaviors, and it doesn’t get us the level of detail in analysis we would like to have in order to meaningfully influence product and service design decisions.

In this chapter, I’ll recommend a different take on market research that combines watching people in their typical work or play, and interviewing them. I’ll show you that if you’ve already done some qualitative studies, you might already have a fair bit of interesting data to work with already. And if you don’t have that data, that collecting it is within your grasp. And what I’m proposing is designed so that anyone can conduct the research — no psychology PhD’s or white lab coats required. It may be very familiar to psychologists and anthropologists: the contextual interview.

Why a contextual interview?

If I had to get to the essence of what a contextual interview is, I’d say “looking over someone’s shoulder and asking questions,” with a focus on observing customers where they do their work (e.g., at their desk at the office, or at the checkout counter) or where they live and play.

The number one reason why digital products take longer and cost more than planned is a mismatch between user needs and functionality. We need to know what our customers’ needs are. Unfortunately, we can’t learn what we need to simply asking by them. There are several reasons why this is the case.

First, customers often just want to keep doing what they’re doing, but better. As product and service designers who are outside that day-to-day grind, we can sometimes envision possibilities beyond today’s status quo and leapfrog to a completely different, more efficient, or more pleasurable paradigm. It’s not your customer’s job to envision what’s possible in the future; it’s ours!

Second, there are a lot of nuanced behaviors people do unconsciously. When we watch people work or play in the moment, we can see some of the problems with an experience or that don’t make sense, that customers compensate for and don’t even know they are doing so. How likely is it that customers are going to be able to report behaviors they themselves aren’t even aware of?

For example, I’ve observed Millennials flipping wildly between apps to connect with their peers socially. They never reported flipping back and forth between apps, and I don’t think they were always conscious of what they were doing. Without actively observing them in the moment, we might never have known about this behavior, which turned out to be critical to the products we were gathering research for.

We also want to see the amazing lengths to which “super-users” — users of your products and services who really need them and find a way to make them work — go to in order to create innovations and workarounds that make the existing (flawed) systems work. We’ll talk about this later, but this notion of watching people “in the moment” is similar to what those in the lean startup movement call to GOOB, or Getting Out Of (the) Building, to truly see the context in which your users are living.

Third, if your customers are not “in the moment,” they often forget all the important details that are critical to creating successful product and service experiences. Memory is highly contextual. For example, I am confident that when you visit somewhere you haven’t been in years you will remember things about your childhood you wouldn’t otherwise because the context triggers those memories. The same is true of customers and their recollections of their experiences.

In psychology, especially organizational psychology or anthropology, watching people to learn how they work is not a new idea at all. Corporations are starting to catch on; it’s becoming more common for companies to have a “research anthropologist” on their staff who studies how people are living, communicating, and working. (Fun fact: There is even one researcher that calls herself a cyborg anthropologist! Given how much we rely on our mobile devices, perhaps we all are cyborgs, and we all practice cyborg anthropology!)

Jan Chipchase, founder and director of human behavioral research group Studio D, brought prominence to the anthropological side of research through his research for Nokia. Through in-person investigation, which he calls “stalking with permission” (see, it’s not just me!), he discovered an ingenious and off-the-grid banking system that Ugandans had created for sharing mobile phones.

“I never could have designed something as elegant and as totally in tune with the local conditions as this. … If we’re smart, we’ll look at [these innovations] that are going on, and we’ll figure out a way to enable them to inform and infuse both what we design and how we design.” — Jan Chipchase, “The Anthropology of Mobile Phones,” TED Talk, March 2007

Chipchase’s approach uses classic anthropology as a tool for building products and thinking from a business perspective. Below, I explain how you can do this too.

Empathy research: Understanding what the user really needs

Leave assumptions at the door and embrace another’s reality

Chipchase’s work is just one example of how we can only understand what the user really needs through stepping into their shoes — or ideally, their minds — for a little while.

To think like our customers, we need to start by dispeling your (and your company’s) assumptions about what your customers need and think like your customers. In their Human-Centred Design Toolkit, IDEO writes that the first step to design thinking is empathy research, or a “deep understanding of the problems and realities of the people you are designing for.”

In my own work, I’ve been immersed in the worlds of people who create new drugs, traders managing billion-dollar funds, organic goat farmers, YouTube video stars, and people who need to buy many millions of dollars of “Shotcrete” (like concrete, but it can be pumped) to build a skyscraper. Over and over, I’ve found that the more I’m able to think like that person, the better I’m able to identify opportunities to help them and lead my clients to optimal product and service designs.

Suppose, however, that you were the customer in the past (or worse yet, your boss was that customer decades ago) and you and/or your boss “know exactly what customers want and need” making research unnecessary. Wrong! You are not the customer, and when we do research in this context it can makes it even harder because we fight against preconceived notions and it is harder to listen customers about their needs today.

I remember one client who in the past had been the target customer for his products, but he had been the customer before the advent of smartphones. Imagine being at a construction site and purchasing concrete 10 years ago, around the time of flip phones (if you were lucky!). The world has changed so much since then, and surely the way we purchase concrete has too. This is why to embrace a customer’s reality, you need to park your expectations at the door and live today’s challenges.

Here’s just one example I noticed while securing a moving truck permit. To give me the permit, the government employee had to walk to one end of this huge office to get a form, and then walk all the way over to the opposite corner to stamp it with an official seal, and then walk nearly as foar over to the place where he could photocopy it, and then bring it to me. Meanwhile, the line behind me got longer and longer. Seeing this inefficient process left me wondering why these three items weren’t grouped together. It’s a small example of the little, unexpected improvements you can note just through watching people at work. I’m not sure the government worker even noticed the inefficiencies!

Moments like these abound in our everyday life. Stop and think for a second about a clunky system you witnessed just by looking around you. Was it the payment system on the subway? Your health care portal? An app? What could have made the process smoother for you? Once you start observing, you’ll find it hard to stop. Trust me. May your kids, friends, and relatives be patient with your “helpful hints” from here on out!

Any interview can be contextual

Because so much of memory is contextual, and there are so many things our customers will do that are unconscious we can learn learn so much when immersed in their worlds. That means meeting with farmers in the middle of Pennsylvania, sitting with traders in front of their big bank of screens on Wall St., having happy hour with high-net worth jet setters near the ocean (darn!), observing folks who do tax research in their windowless offices, or even chatting with Millennials at their organic avocado toast joint. The key point is, they’re all doing what they normally do.

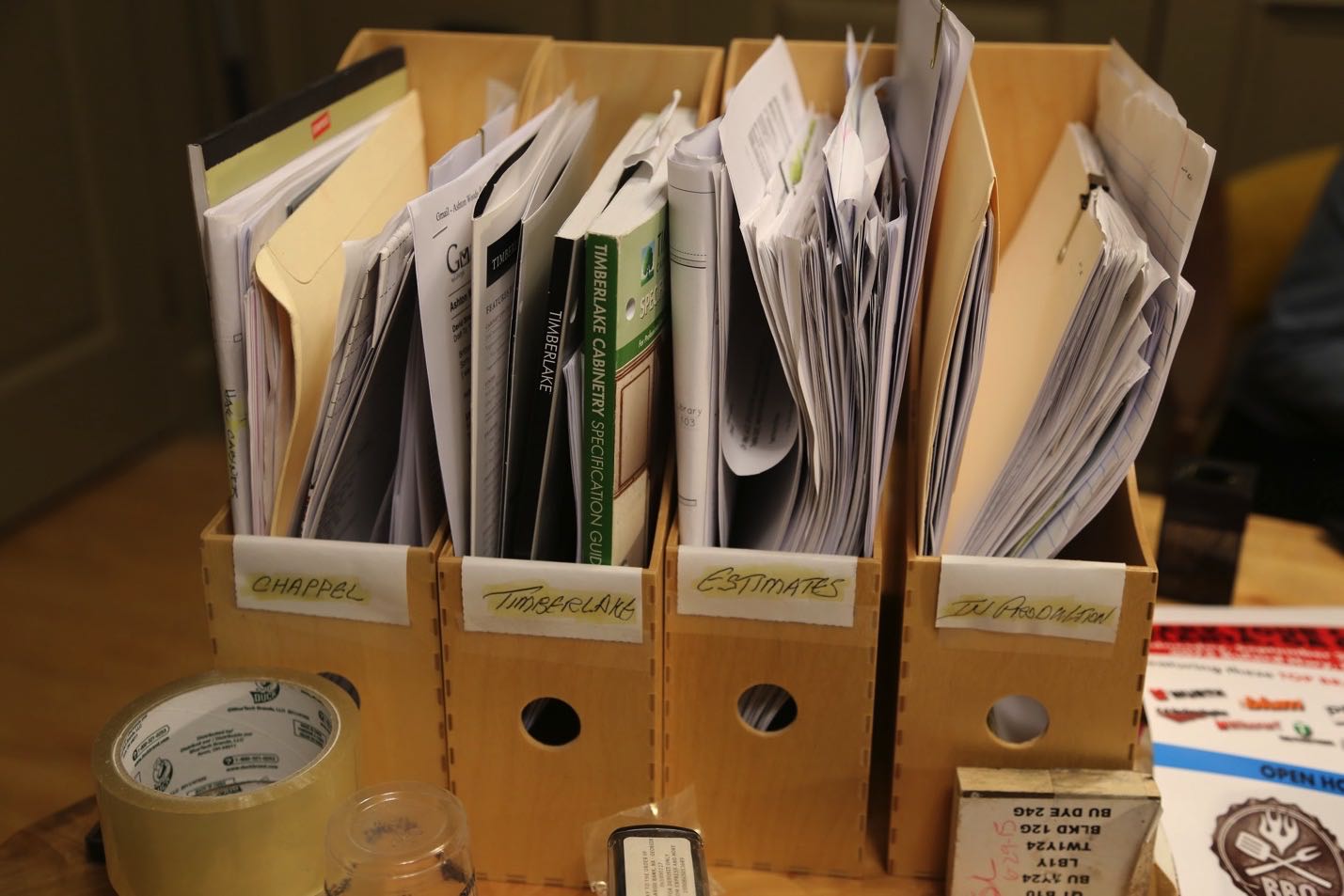

Contextual interviews allow the researcher to see workers’ post-its on their desk, what piles of paper are active and what piles are gathering dust, how many times they’re being interrupted, and what kind of processes they actually follow (which are often different than the ones that they might describe during a traditional interview). Your product or service has to be useful and delightful for your user, which means you need to observe your customers and how they work. The more immersive and closer to their actual day, the better.

Figure 9.1: Observing how a small business owner is organizing his business

In contextual inquiry, while I want to be quiet sometimes and just observe, I also ask my research subjects questions like:

- ● What would I need to know to be successful at your job?

- ● Where would I get started?

- ● What would I have to keep in mind?

- ● What could go wrong?

- ● What drives you crazy sometimes?

What researchers notice

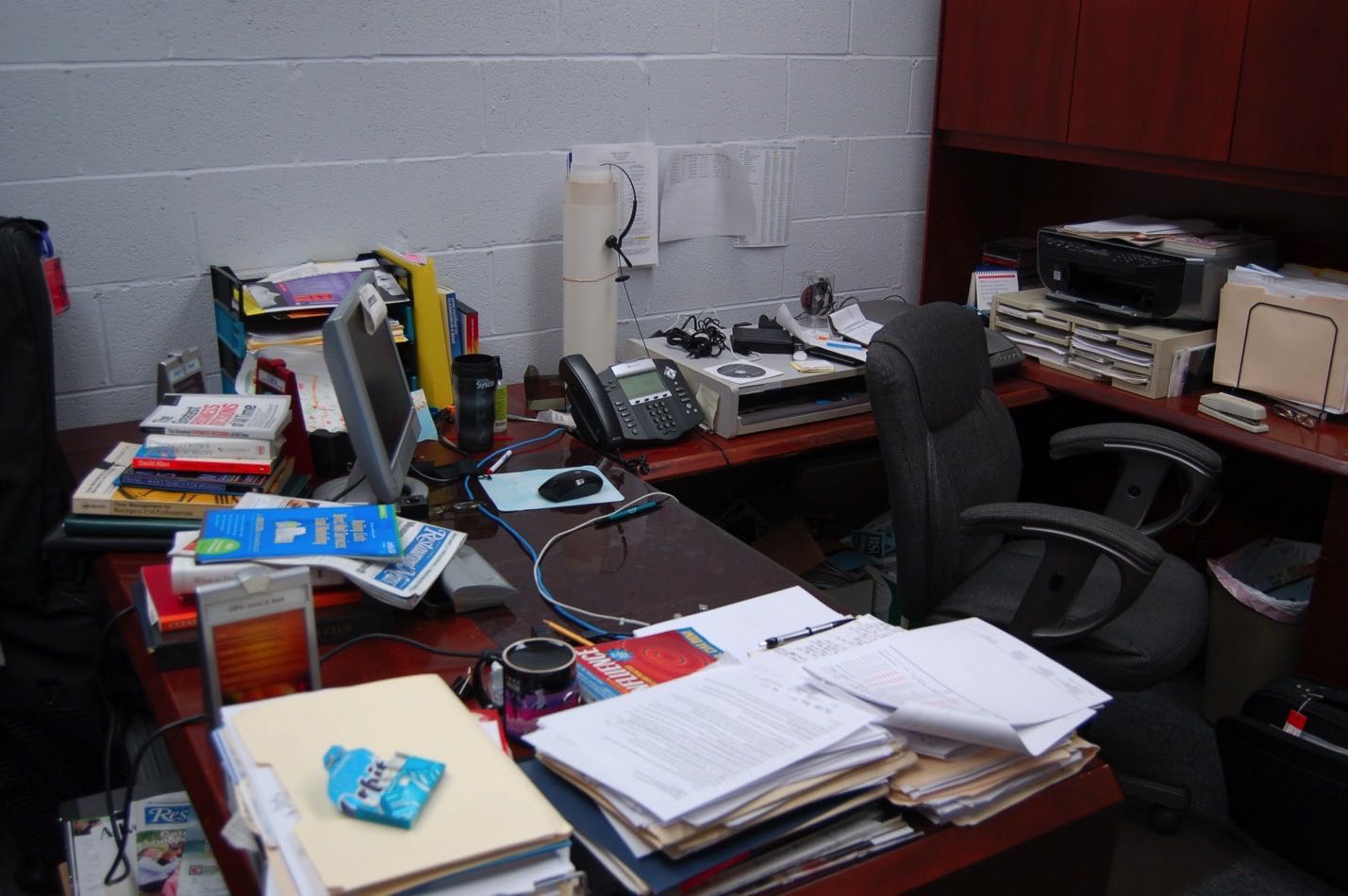

Figure 9.2: Example of the desk of a research participant. Why do they have the psychology book “Influence” right in the middle I wonder?

Researchers who do contextual interviews typically consider the following:

- ● Artifacts: What’s on the desk? What papers, files, spreadsheets, etc. does this person use to keep track of everything? What else is nearby in the environment?

- ● Communication: How is work communicated or reviewed (e.g., email, software, discussion, etc.)? How many other people are working with the user?

- ● Interruptions: What are the interruptions in the user’s job? How often are these? Do they frequently need to move around? What’s the noise level like? How many times is their mobile phone interrupting them? Are they constantly hearing loud overhead announcements about the Dow Jones index? (This last example was actually the case for some stock traders I observed. Their workplace was already so loud and stressful that what they needed from my client was essentially an “easy button” that was simple and made their jobs easier.)

- ● Related Factors: What other jobs does this person do in addition to the one you are officially observing? How many programs do they have to use? Are they always on the computer? Are they using their mobile phone?

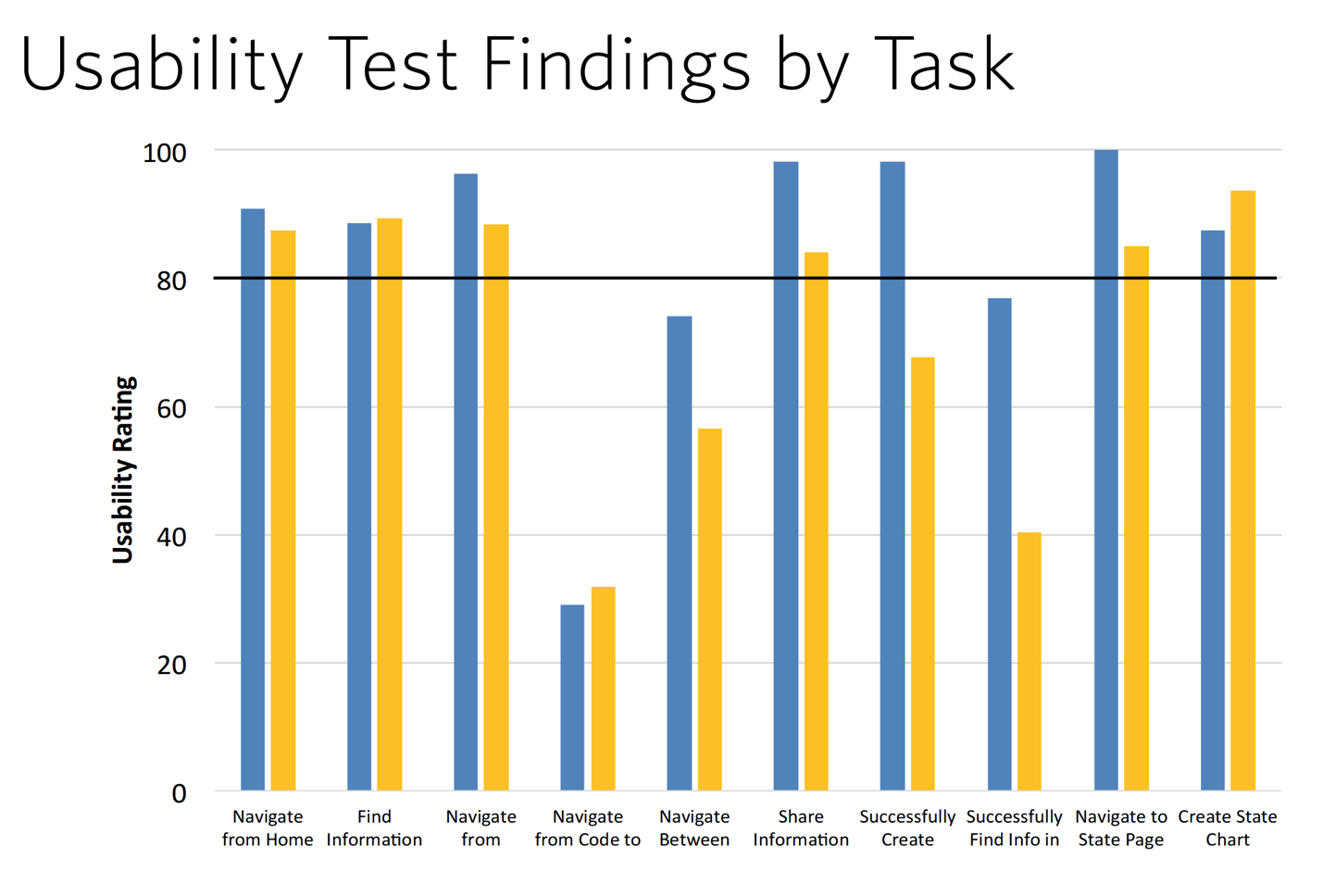

Why not surveys or usability test findings?: Discovering the what vs. why

Clients sometimes assure me that their user research is solid and they need no other data because they received thousands of survey responses. It is true that that client has an accurate reading of the what of the immediate problem (e.g., the customer wants a faster process, step 3 of a problem is problematic, or the mobile app is cumbersome). These get at the what the customer is asking for, but as product and service designers, we need to get to the why of the problem, and the underlying reasons and rationale behind the what.

It could be that the customer is overwhelmed by the appearance of an interface, or was expecting something different, or is confused by the language you’re using. It could be a hundred different things. It is extremely hard to infer the underlying root cause of the issue from a survey or from talking to your colleagues who build the product or service. We can only know why customers are thinking the way they are through meeting them and observing them in context.

Figure 9.3: Example of usability test findings. From the above chart, can you tell why these participants are having trouble “Navigating from Code” in the fourth set of bars? [Me neither!]

Classic usability test findings often provide the same “what” information. They will tell you that your users were good at some tasks and bad at others, but often don’t provide the clues you need to get to the why. That is where conducting research with the Six Minds in mind comes to the rescue.

Recommended approach for contextual interviews and their analysis

As I’ve implied throughout this chapter, shadowing people in the context of their actual work allows you to observe both explicit behaviors, as well as implicit nuances that your interviewees don’t even realize they are doing. The more that users show you their processes step-by-step, the more accurate they will be when it comes to the contextual memory of remembering that certain process.

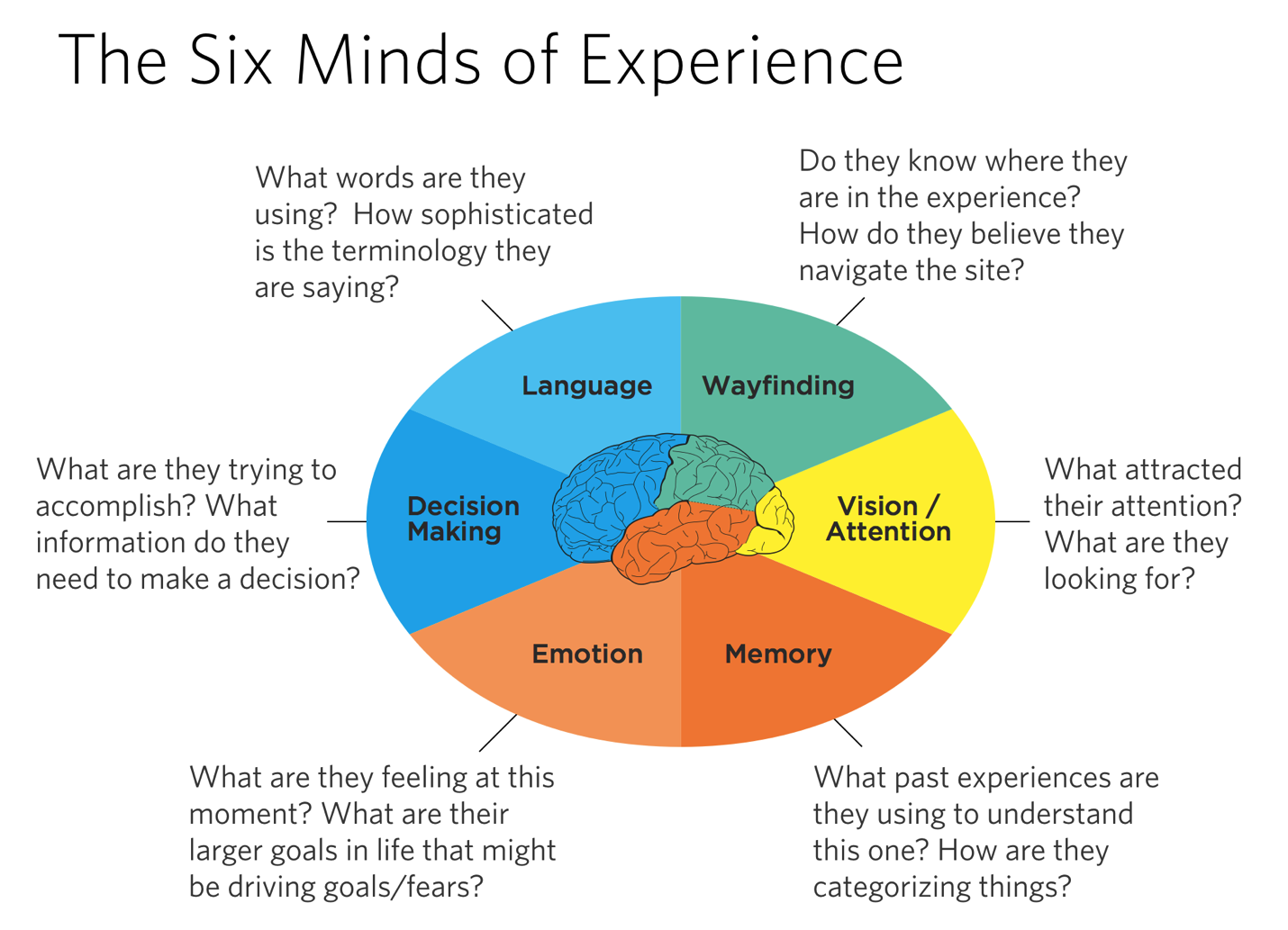

With our Six Minds of Experience, I want you to not just experience the situation in context, but also be actively thinking about many different types of mental representations within your customer’s mind:

- ● Vision/Attention: What are they paying attention to? What are they searching for? Why?

- ● Wayfinding: How are they navigating their existing products and services? How do they believe they should interact with them?

- ● Language: What words do they use? What does that suggest about their level of expertise?

- ● Memory: What assumptions are they making about how things should work? When are they surprised and confused?

- ● Decision Making: What do they say they are trying to accomplish? What does that say about how they are framing the problem? What decisions are they making? What “blockers” are getting in the way?

- ● Emotion: What are their goals? What are they worried about?

- ● How might future products or services be better suited to match their needs, expectations, desires and goals?

The sort of observation I’ve described so far has mostly focused on how people work, but it can work equally well in the consumer space. Depending on what your end product or service is, your research might include observing a family watch TV at home (with their permission, of course), going shopping at the mall with them, or enjoying happy hour or a coffee with their friends. Trust me: you’ll have many stories to tell about all the things your customers do that you didn’t expectwhen you return to the office!

This is probably the funnest part, and shouldn’t be creepy if you do it correctly. I give you permission (and they should provide their or their parents’ written permission) to be nosy, and curious, and really to question all your existing assumptions. When I’m hiring someone, I often ask them if they like to go to an outdoor cafe and just people-watch. Because that’s my kind of researcher: we’re totally fascinated by what people are thinking, what they’re doing, and why. Why is that person here? Why are they dressed the way they are? Where are they going next? What are they thinking about? What makes them tick? What would make them laugh?

There are terrific whole books dedicated to the contextual interviews I’ll mention at the end of this chapter. I’ll leave it to them to provide all the nuances to these interviews, but I definitely want you to go into your meetings in the following mindset:

- ● You are there to learn and observe. That means you need to blend in, not be the star attraction (your customer is), ask open-ended questions, and leave your assumptions, perspectives, and opinions at the door. Imagine that you are an actor learning to play this role, or that you will be taking over for them during maternity/paternity leave — you would never tell them they’re wrong, or show them how to do something. You want to learn how to do things their way and think like them.

- ● Follow their customs. Try to dress in a way that is commensurate with your audience, so you are neither intimidating, nor stand out. Your goal is to blend in and not influence the situation. If they take off their shoes at the door, so should you. Be ready to sit on the floor, or eat pizza straight from the box.

- ● Try to adopt their language (i.e., try not to be more technical even if you know more about a subject). Try not to use your company’s in-house jargon. In fact, do the opposite — ask them what they would call a concept or action and use those terms before you use your words.

- ● Ask why. While sometimes people rationalize and have implicit reasons for an activity, it is always interesting to see what they come up with. Often it helps to understand how they are framing a problem or decision to make, and get clues as to their underlying assumptions.

- ● Try to minimize your influence on their actions. It is very hard for someone who is building a product or service not to demonstrate, teach, or promote when you know an easier way to do something, or that your product has the perfect feature that could help. That is not your role. (Not yet, at least.) You need to observe their perspective, not matter how tough it may be for you to watch. You need to know the reality on the ground.

- ● Make sure you observe them in action. Many times, if you’re meeting someone at an office, they’ll want to meet in a conference room. While perhaps that would be more comfortable, it’s preferable to huddle around their desk and observe them in action in their native environment. Crucially, you want to see them doing the things you seek to improve through your products or services.

- ● Only bring a few people to the contextual interview. One to three is an ideal number. Try to have a small footprint. You do not want your audience to feel like they have an audience, and that to perform for the group. And you don’t want the folks following them around to constrict their normal activities.

- ● Record information in subtle ways. Do I love to get video and audio recordings? Absolutely! Do I bring along lights and boom poles and fancy mics? No! Bring a wireless mic that the person will forget they are wearing, and a compact prosumer video camera, and use your cell phones for pictures. You want your customer to be as natural and routine as possible. It is a good sign when they answer the telephone, or walk out of the office to ask a colleague a question (because they are doing their normal routine and not being polite to you).

- ● Bring a notebook, not a computer. You want to write notes immediately and not worry about time booting up or connecting to wifi. And I say this from experience: bring an extra pen! One of your colleagues from the office who is following along will forget.

- ● Do ask them about themselves, and their perspective. How long have you been doing this? How did you get started? What do you like about the job? What do you do when you are not here? What do you hope to achieve? What makes you happiest? As the observer, you want to be able to see the world through their eyes and understand what makes them tick. Start with normal socially acceptable questions (e.g., How did you get started in this job?) and gradually get to deeper questions (e.g., What is most important to you in life? What would make you feel accomplished/happy/satisfied?).

Common questions

- ● How many people do I need to interview? Generally I try to estimate the number of user groups according to their lifestyle or role (e.g., I might interview middle schoolers, high schoolers, and college undergraduates in an academic setting, or in a medical setting I might want to interview doctors (GPs), specialists, nurses, and administrators). You want about eight to twelve people per group to identify trends. However, if reality and the ideal clash, remember that any amount is always more than zero!

- ● How long should the contextual interviews be? I encourage 90-minute interviews. Young kids might not last that long, and busy doctors may refuse that duration. In other cases, you can “ride along” for longer periods (e.g., a morning or afternoon). You want a long enough duration to observe participants’ typical pattern of activities and talk to them about themselves and their perspective.

- ● How do I recruit them? I encourage you to use a professional recruiting service. The time it takes to schedule, remind, reschedule, discuss, pre-screen, etc., is far more than you imagine if you have never done it before. Recruiters can be well worth the money (and freedom from aggravation). If you choose to recruit on your own and are looking for professionals, start with associations. For the general public, you’d be surprised how far networking and Craigslist can get you. However, when you are flying around the country to conduct interviews, the cost of professional recruitment can be well worth avoiding the situation of getting there and having no one to interview.

- ● Should I have a set of questions prepared? Yes, but … I encourage you to “go with the flow” of the interviewee. There is a balance to be struck between having participants stay on task, and not taking them too far from their standard way of working or living. Don’t think of a contextual interview as something for which you need to fill out a form and have every black filled. Rather, think of it as getting the information you need to step into their world. Often you’ll find the conversation heads naturally to what they know, how they frame a problem, and what they value in life. There will be different types of people and thus it is important to have multiple interviews to define customer segments.

From data to insights

Many people get stuck at this step. They have interviewed a set of customers and feel overwhelmed with all of their findings, quotes, images, and videos. Is it really possible to learn what we need to know just through these observations? All of these nuanced observations that you’ve gathered can be overwhelming if not organized correctly. Where should I begin?

To distill hundreds of data points into valuable insights on how you should shape your product or service, you need to identify patterns and trends. To do so, you need the right organizational pattern. Here’s what my process looks like.

Step 1: Review and write down observations

In reviewing my own notes and video recordings, I’ll pull out bite-sized quotes and insights on users’ actions (aka, my “findings”). I write these onto post-it notes (or on virtual stickies in a tool like Mural or RealTimeBoard). What counts as an observation? Anything that might be relevant to our Six Minds:

- ● Vision/Attention: What are they paying attention to?

- ● Wayfinding: What is their perception of space, and how to move around in that space?

- ● Memory: What are their perspectives on the world?

- ● Language: What are the words they use?

- ● Decision-making: How are they framing the problem? What are they really trying to solve (deeper need)? What “blockers” are getting in the way?

- ● Emotion: What are they worried about? What are their biggest goals?

In addition, if there are social interactions that are important (e.g., how the boss works with employees), I’ll write those down as well.

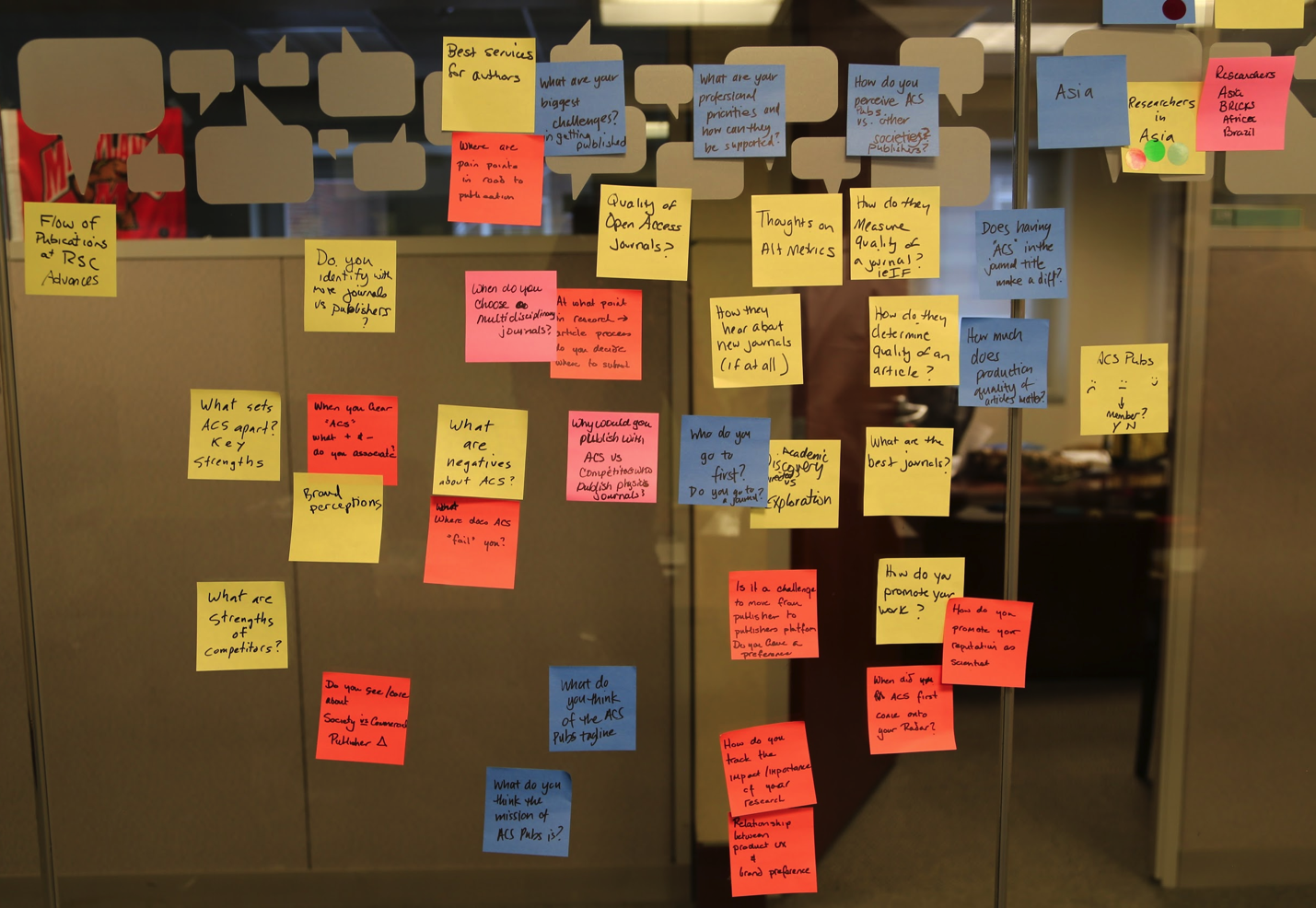

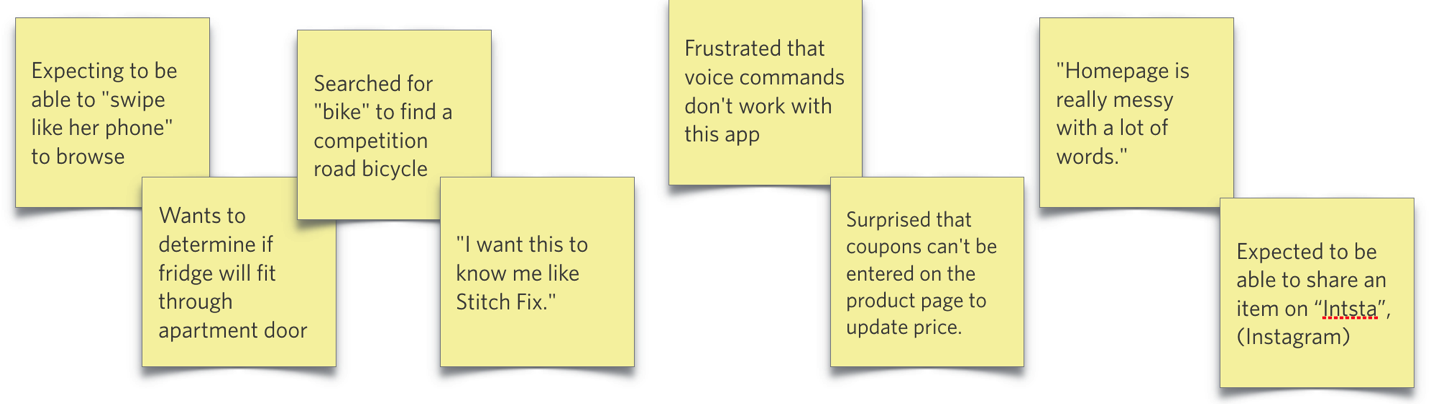

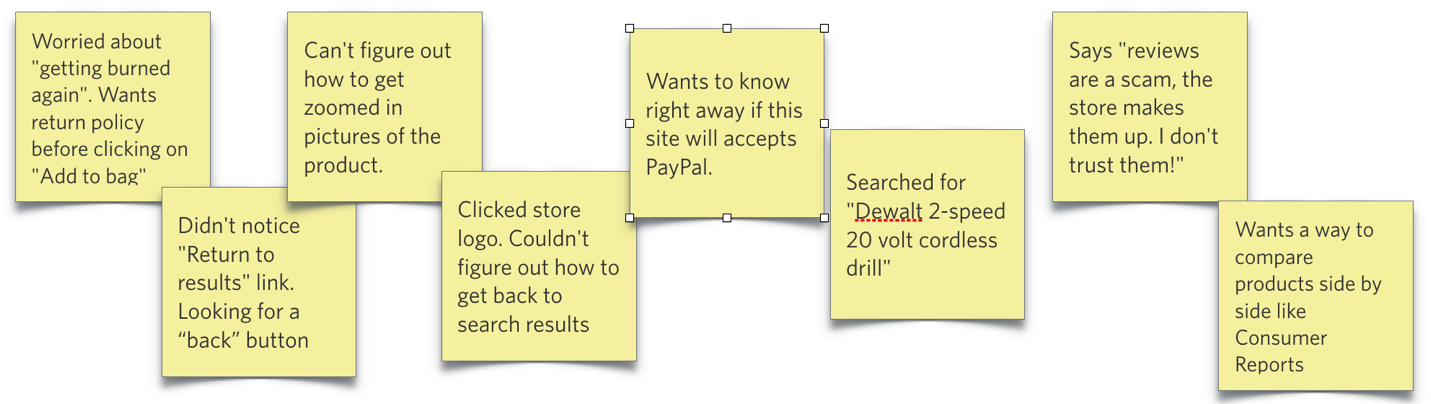

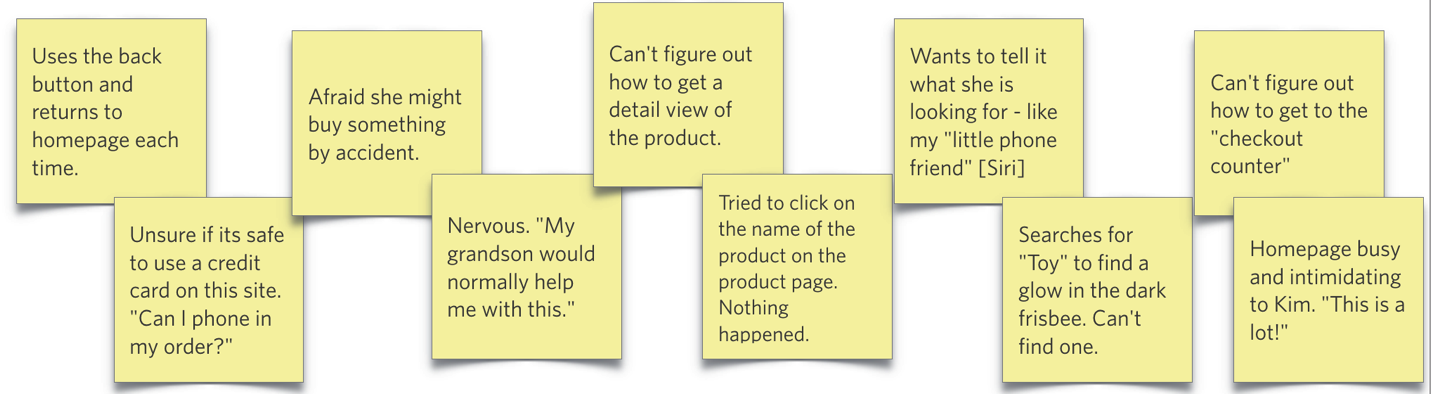

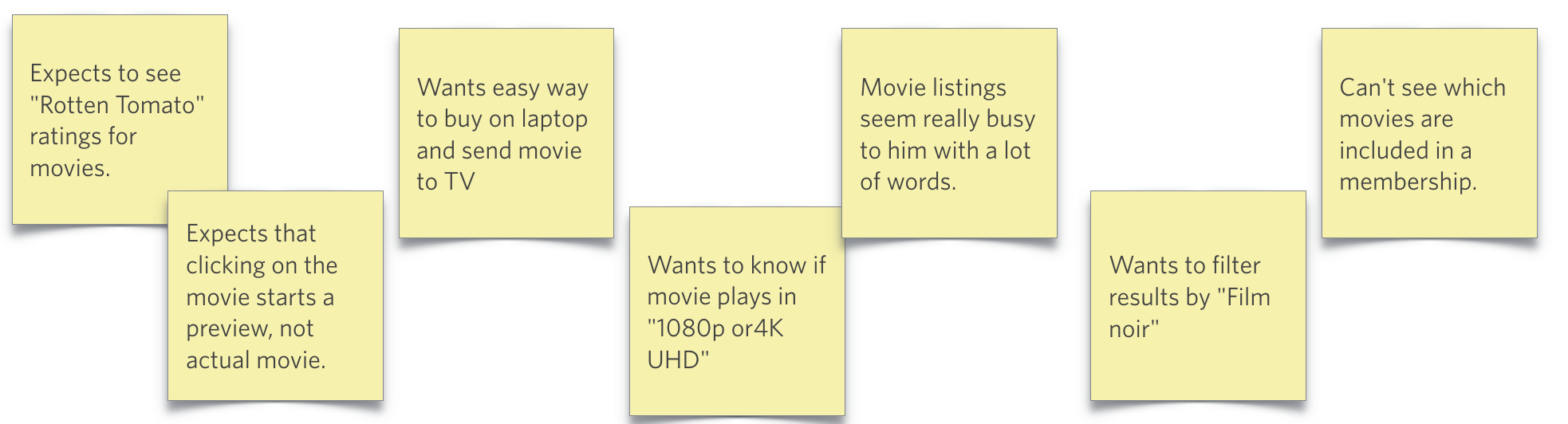

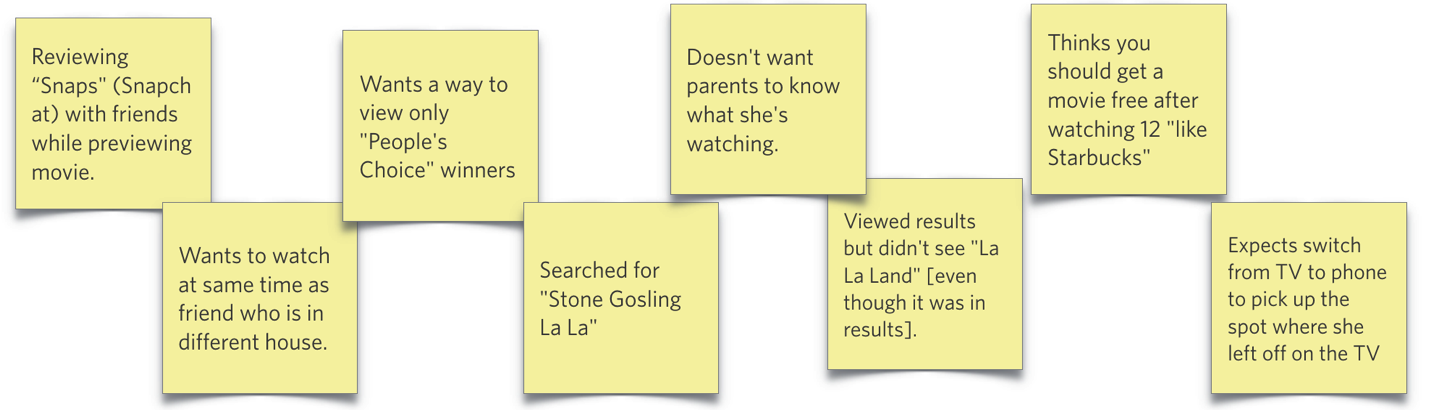

Figure 9.4: Example of findings from contextual interviews.

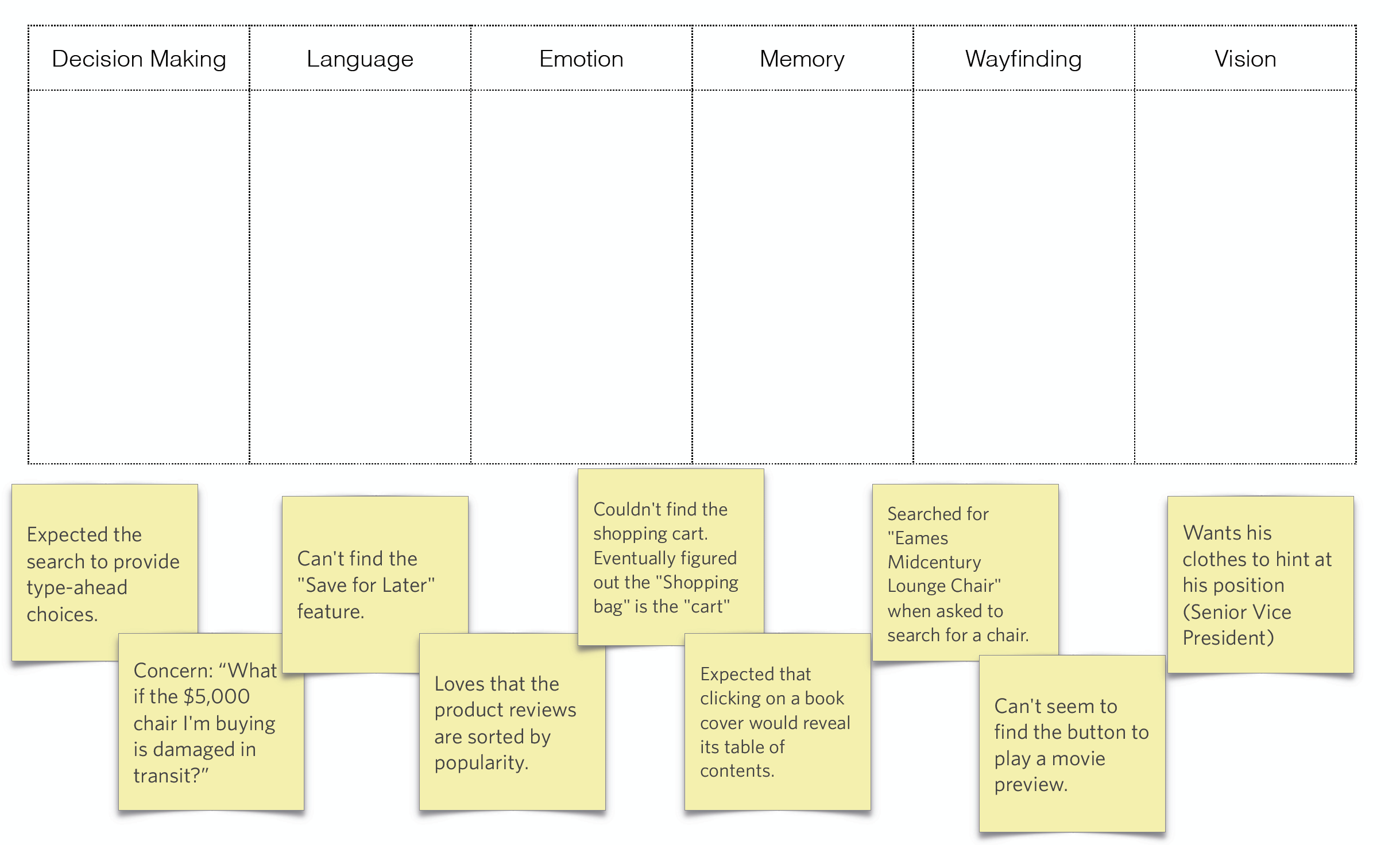

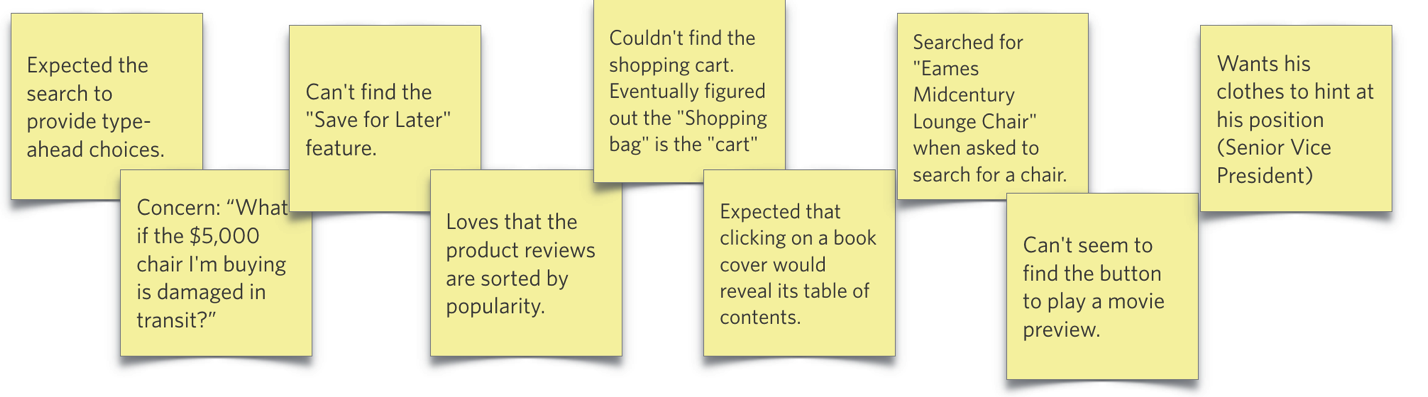

Step 2: Organize each participant’s findings into the Six Minds

After doing this for each of my participants, I place all the sticky notes up on a wall, organized by participant. I then align them into six columns, one each for the Six Minds. A comment like “Can’t find the ‘save for later’ feature” might be placed in the Vision/Attention column, whereas “Wants to know right away if this site accepts PayPal” might be filed as Decision-Making. Much more detail on this to follow in the next few chapters.

Figure 9.5: Getting ready to organize findings into the six minds.

If you try out this method, you’ll inevitably find some overlap; this is completely to be expected. To make this exercise useful for you, however, I’d like you to determine what the most important component of an insight is for you as the designer, and categorize it as such. Is the biggest problem visual design? Interaction design? Is the language sophisticated enough? Is it the right frame of reference? Are you providing people the right things to solve the problems that they encounter along the way to a bigger decision? Are you upsetting them in some way?

Step 3: Look for trends across participants and create an audience segmentation

In Part 3 of this book we talk about audience segmentation. If you look for trends across groups of participants, you’ll observe trends and commonalities across findings, which can provide important insights about the future direction for your products and services. Separating your findings into the six minds can also help you manage product improvements. You can give the decision-making feedback to your UI expert who worked on the flow, the vision/attention feedback to your graphic designer, and so on. The end result will be a better experience for your user.

In the next few chapters, I’ll give some concrete examples from real participants I observed in an e-commerce study. I want you to be able to identify what might count as an interesting data point, and have you be able to think about some of the nuance that you can get from the insights you collect.

Exercise

In my online classes on the six minds, I provide participants with a small set of data I’ve appropriated from actual research participants (and somewhat fictionalized so I don’t give away trade secrets).

On the following images are the notes from 6 participants who were in an ecommerce research study. They were asked to make purchasing decisions and were seeking either a favorite item, or selecting an online movie for purchase and viewing. The focus of the study was on searching for the item and selecting it (the checkout was not a focus of the study). The notes below reflect the findings collected during contextual interviews.

Your challenge: Please put each of the notes about the study in the most appropriate category (Vision/Attention, Wayfinding, etc.).

Feeling stuck? Perhaps this guide can help:

Figure 9.6: The Six Minds of Experience

If you feel it should be in more than category on occasion you may do so, but try to limit yourself to the most important category. What did you learn about how each individual was thinking? Were there any trends between participants?

Participant: ________________________

|

Decision Making |

Language |

Emotion |

Memory |

Wayfinding |

Vision |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 9.7: In which category would you place each finding?

Figure 9.8: Findings from participant 1, Joe

Figure 9.9: Findings from participant 2, Lily

Figure 9.10: Findings from participant 3, Dominic

Figure 9.11: Findings from participant 4, Kim

Figure 9.12: Findings from participant 5, Michael

Figure 9.13: Findings from participant 6, Caroline

I’ll return to these 6 participants and provide snippets of that dataset as needed in the next six chapters to concretely illustrate some nuance and sharpen your analytic swords and know how to handle data in different situations.

Can’t wait to find complete the exercise and share it with your friends? Great! Please download the Apple Keynote or MS PowerPoint versions to make it easy to complete and share [LINK HERE].

Completed the exercise and want to see how your organization compares to the authors? Please go to Appendix [NUMBER].

Concrete recommendations:

- ● Watch people work in their place of work, rather than just interview (many more contextual memories surface when they’re “in the moment”)

- ● Watch people complete tasks, not just discuss needs (again, more contextual memories and unconscious behaviors surface)

- ● Try to deduce underlying assumptions about the world that underlie their behavior (allowing yourself to think like the consumer allows you to discover their pain points and insights that you can help with)

- ● Measure their observable behavior, not just spoken discussion on topic (e.g., how many times are they checking their phone? How many times do they use paper, vs. computer?)