Copyright © 2019 John Whalen

All rights reserved.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

ISBN-13: 9781491985380

2018-11-06

Chapter 1. Rethinking “The” Experience

Great experiences

Think of a truly great experience in your life.

Was it one of life’s milestones? The birth of a child, marriage, graduation, etc.? Or was it a specific moment in time—a concert with your favorite band, a play on Broadway, an immersive dance club, an amazing sunset by the ocean, or watching your favorite movie.

You might remark that it was “brilliant”, or “an amazing experience!” to a friend.

What you probably didn’t think about was how many different sensations and cognitive processes blend together to make that experience for you. Could you almost smell the popcorn when you thought of that movie? Maybe the play had not only great acting but creative costumes and lighting and starred someone you had a crush on at the time. Was the concert experience exceptional because you were unexpectedly offered a free drink, then escorted to your seats, filled with glorious music, and dancing with festive fans nearby. So many elements come together to provide a “singularly” great experience.

What if you wanted to make an experience yourself? How might you go about designing a great experience with your product or service? What are the sensations and cognitive processes that make up your experience? How can you tease it apart systematically into component parts? How will you know you are building the right thing?

This book is designed to help you understand and harness what we know about human psychology to unpack experiences into their component parts and uncover what is needed to build a great experience. This is a great time to do so. The pace of scientific discoveries in brain science has been steadily increasing. There have been tremendous breakthroughs in psychology, neuroscience, behavioral economics, and human-computer interaction that provide new information about distinct brain functions and how humans process that information to generate that feeling of a single experience.

How humans think about thinking (and what we don’t realize)

Your thoughts about your own thinking can be misleading. We all have the feeling of being sentient beings (at least I hope you do, too). We know what it’s like to experience our own thoughts – what early psychologists like the Gestaltists called “introspection”. But there are limits to your awareness of your own mental processes.

We all know what it’s like to struggle over a decision about which outfit to wear for something like a job interview: Do you meet their initial expectations? Will they get the wrong impression? Does it look good? Do you look professional enough? Do those pants still fit? Are those shoes too attention-grabbing? There are a lot of thoughts there – but there are still more thoughts that you are unable to articulate, or even be aware of.

One of the fascinating things about consciousness is that we are not aware of all of our cognition. For example, while we are easily able to identify the shoes we plan to wear to the interview, we do not have insight into how we recognized shoes as shoes, or how we were able to sense the color of the shoes. In fact, there are an amazing variety of cognitive processes that are impenetrable to introspection. We generally don’t know where our eyes are moving to next, the position of our tongue, the speed of our heart rate, how we see, how we recognize words, how we remembered our first home (or anything), to mention just a few.

There are other more advanced mental processes that are also automatic. When we think of Spring, we might automatically think of green plants, busy songbirds, or blooming flowers. Those together might give you a pleasant emotional state, too. As soon as you think of almost any concept, your brain automatically conjures any number of related ideas and emotions without conscious effort.

This book is about measuring and unpacking an experience, and so we must identify not only consciously accessible cognitive processes, but also those that are unconscious (like eye movements often are) and deep-seated emotions related to those concepts.

Why product managers, designers and strategists need this information

No product, service, or experience will ever be a runaway success if it does not end up meeting the needs of the target audience. But beyond that we want someone who is introduced to the product or service for the first time to say something like a London-er might: “Right, that’s brilliant!”

But how, as a corporate leader, marketer, product owner, or designer do you make certain your products or services have a great experience? You might ask someone what they want, but we know that many people don’t actually understand what they are trying to solve and often can’t clearly articulate their needs. You might work from the vantage of what you would want, but do you really know how a 13-year-old girl wants to work with Instagram? So how should you proceed?

This book is designed to give you the tools you need to deeply understand the needs and perspective of your product or service’s audience. As a cognitive scientist, I felt like “usability testing” and “market surveys” and “empathy research” were at times both too simplistic and too complicated. These methods focus on understanding the challenge or the problem users are experiencing, but sometimes I think they miss the mark in helping you, the product team, understand what you need to do.

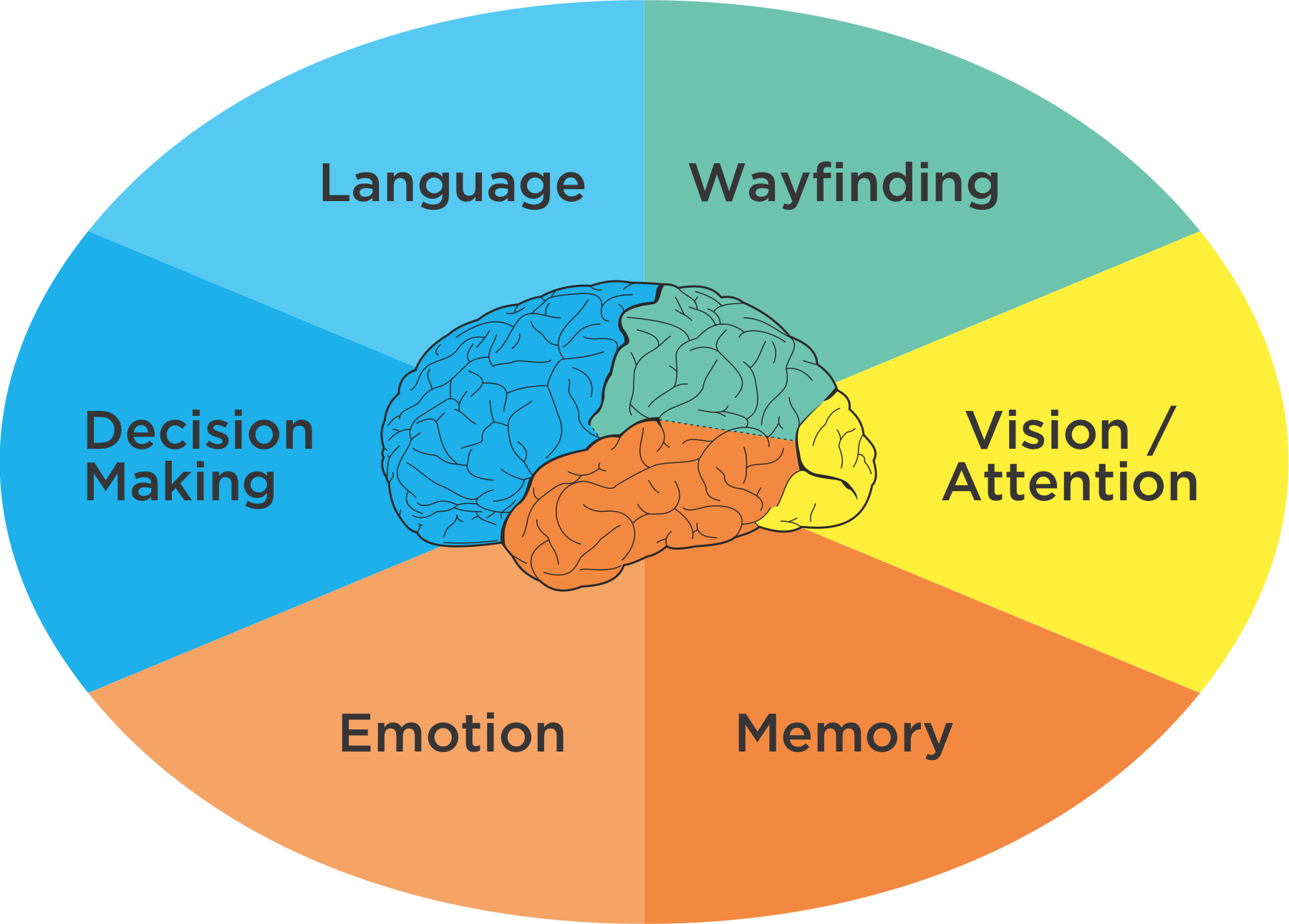

I believe there is a better way: By understanding the elements of an experience (in this book we will describe six), you can better identify audience needs at different levels of explanation. Throughout this book, I’ll help you better understand what the audience needs at those different levels and make sure you hit the mark with each one.

When I’ve given talks on “Cognitive Design” or the “Six Minds of Experience,” corporate leaders, product owners, and designers in the room usually say something to the effect of “That is so cool! But how could I use that?” or “Do I need to be a psychologist to use this?”

Create evidence-based and psychologically-driven products and services

This book is not designed to simply by a fun trip into the world of psychology. Rather, it is a practical one designed to let you put what you learn into immediate practice. It is divided into three major parts. Part 1 details each of the “six minds” which together form an experience. Part 2 describes how to work with your target audience through interviews and watching their behavior to collect the right data and gather useful information for each of the Six Minds. Part 3 suggests how you can apply what you’ve learned about your audiences’ Six Minds and put it to use in your product and service designs.

A final note the to the psychologists and cognitive scientists reading this

Bear with me. In a practical and applied book I simply can’t get to all the nuances of the mind/brain that exist, and I need a way to communicate to a broad audience what to look for that is relevant to design. There are a myriad of amazing facts about our minds which (sadly) I am forced to gloss over, but I do so intentionally so that we may focus on the broader notion of designing with multiple cognitive processes in mind, and ultimately allow for an evidence-based and psychologically-driven design process. It would be an honor to have my fellow scientists work with me to integrate more of what we know about our minds into the design of products and services. I welcome your refinements. At the end of each chapter I will point to further citations the interested reader can pursue to get more of the science they should know.

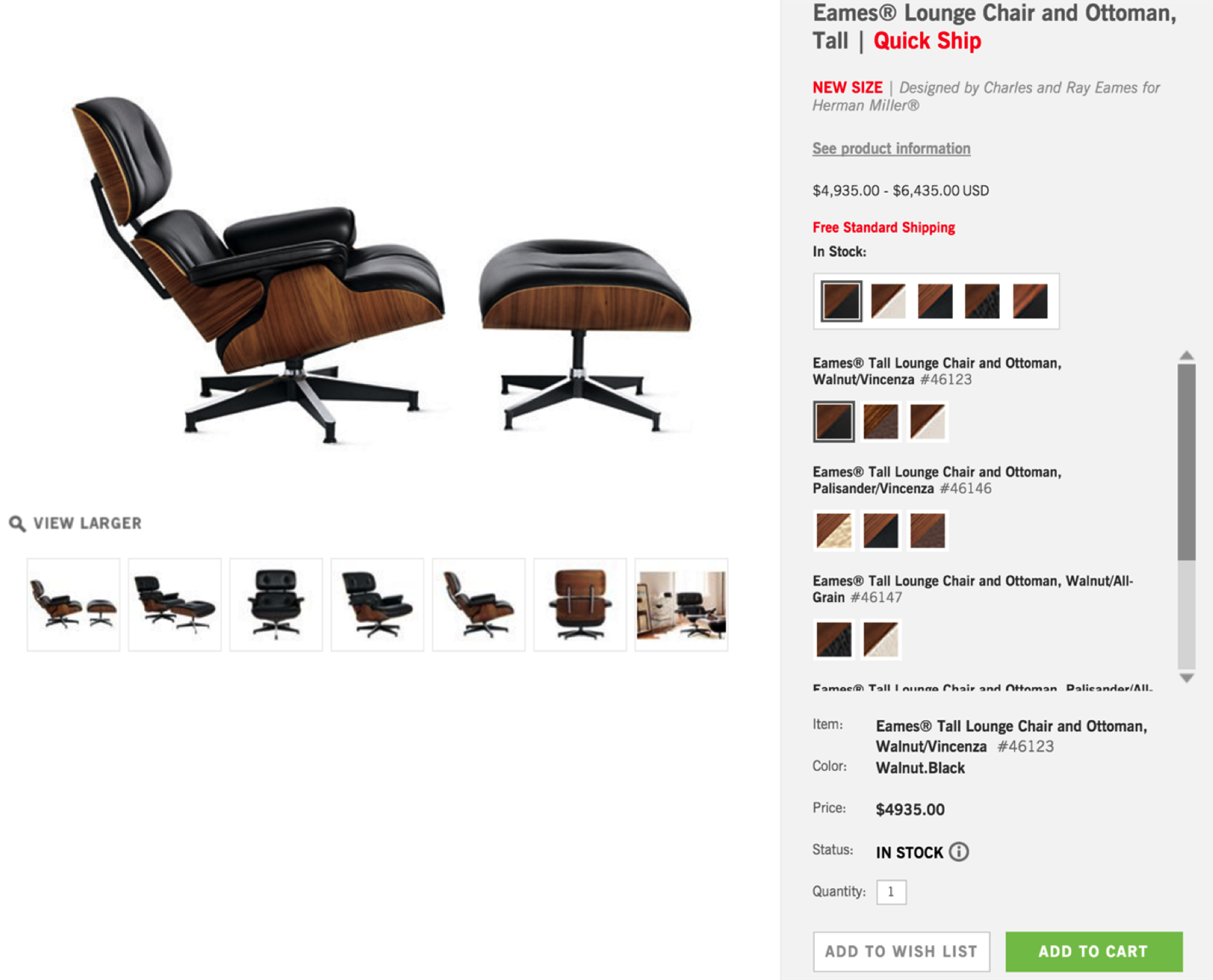

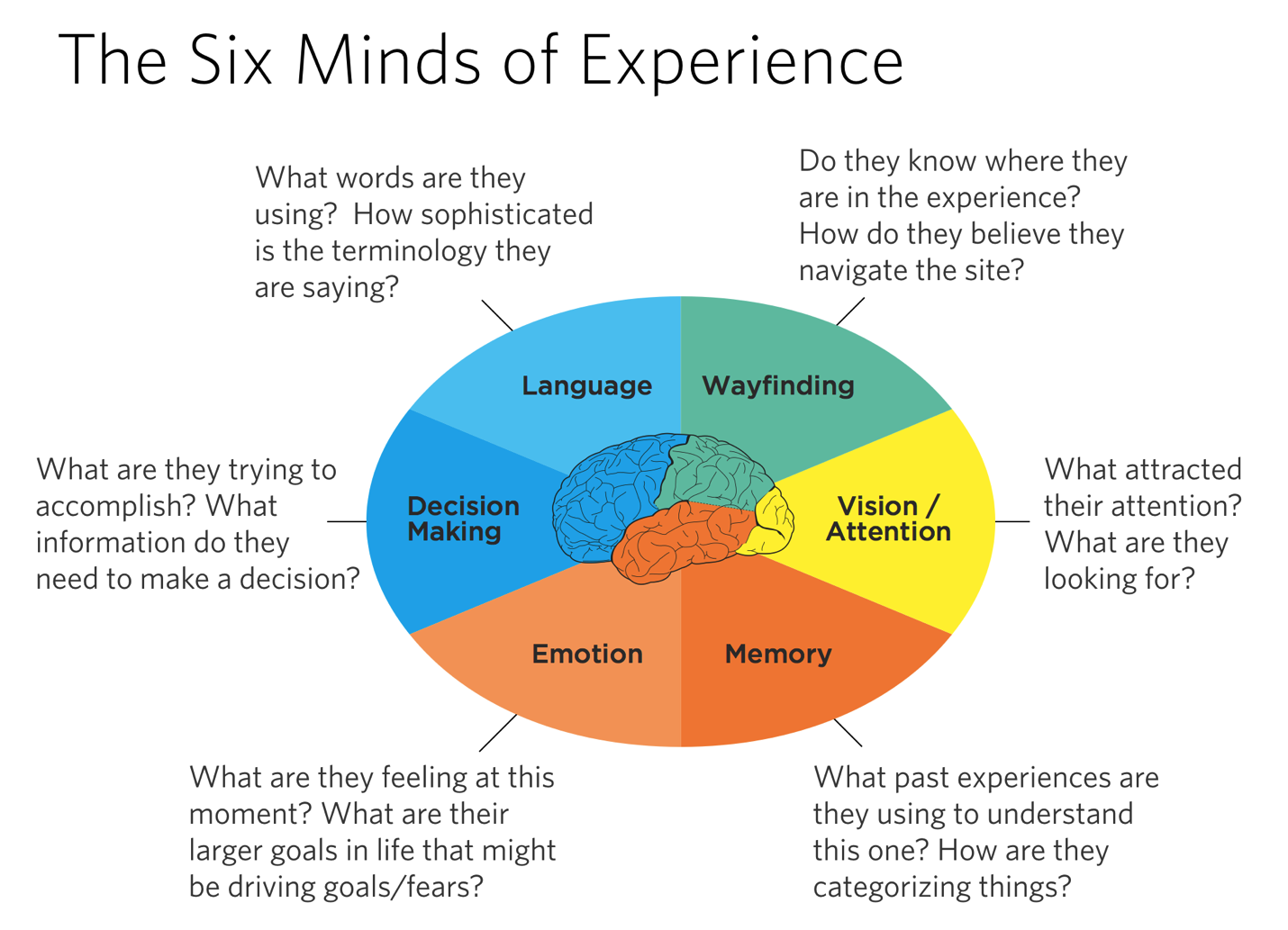

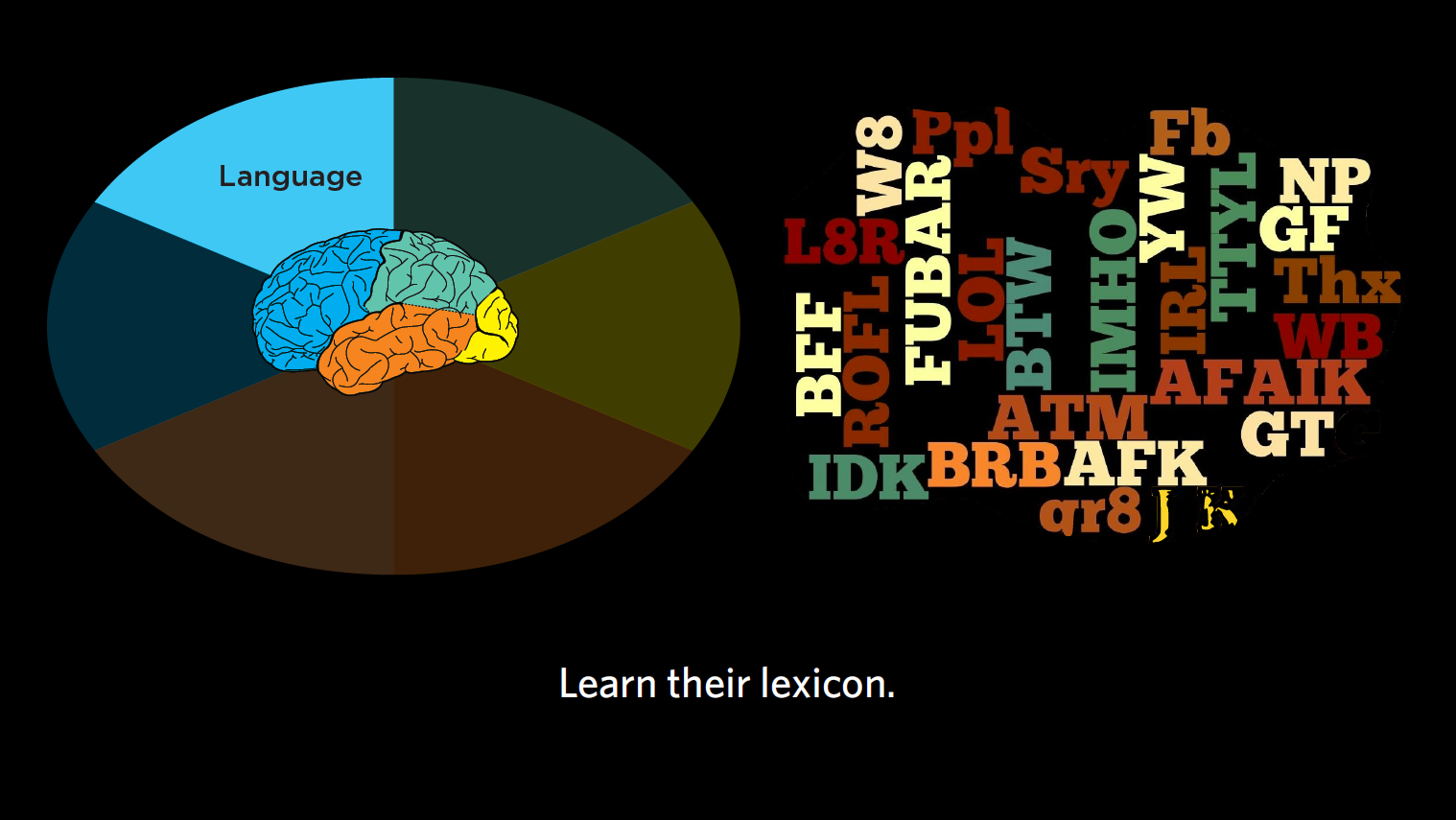

Chapter 2. The Six Minds of User Experience

The six minds of experience

Surely it is the case that there are hundreds of cognitive processes happening every second in your brain. But to simplify to a level that might be more relevant to product and service design, I propose that we limit ourselves to a subset that we can realistically measure and influence.

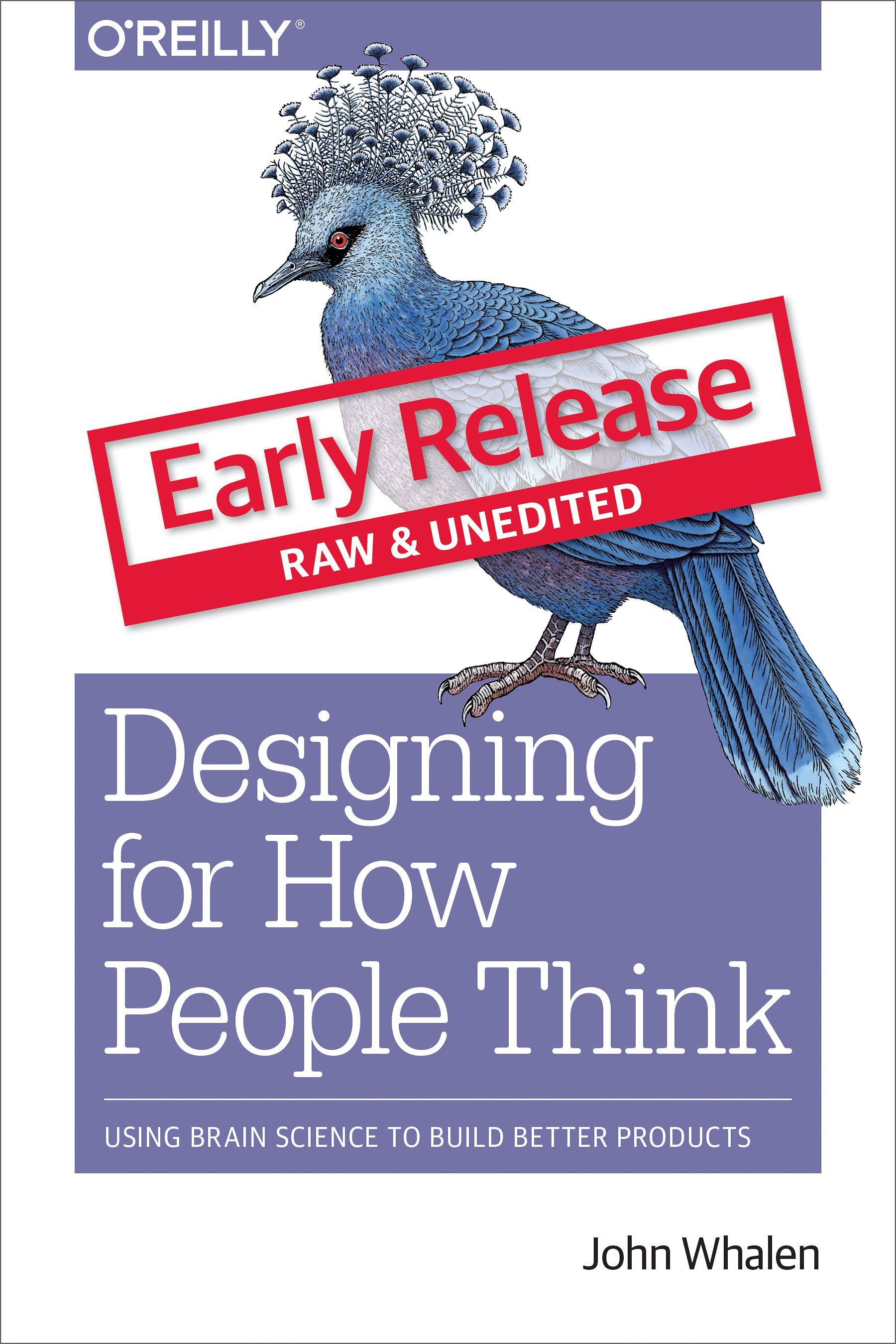

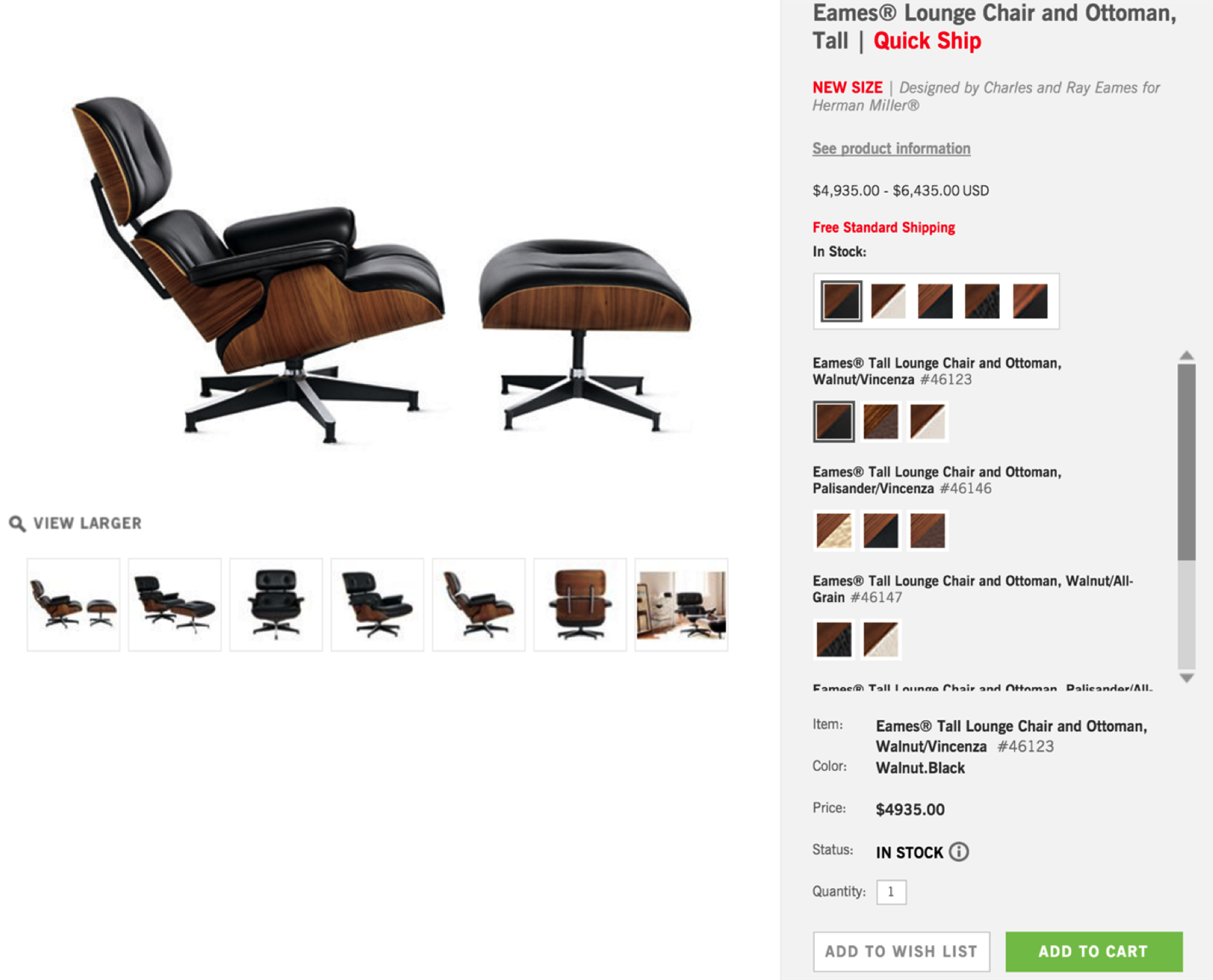

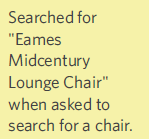

What are these processes and what are their functions? Let’s use a concrete example to explain them. Consider the act of purchasing a chair suitable for your mid-century modern house. Perhaps you might be interested in a classic design from that period, like the Eames’ chair and ottoman below. You are seeking to buy this online and browsing an ecommerce site.

Figure 2.1: Eames Chair

1. Vision, Attention, and Automaticity

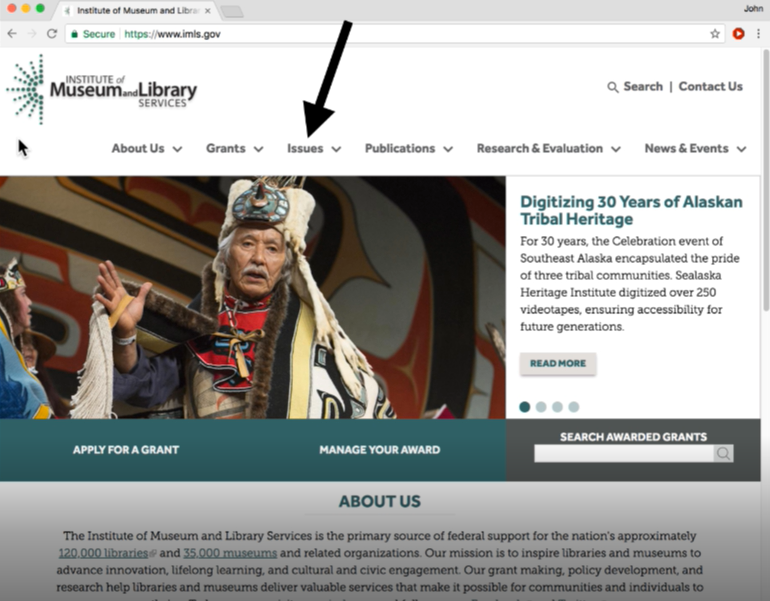

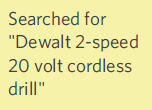

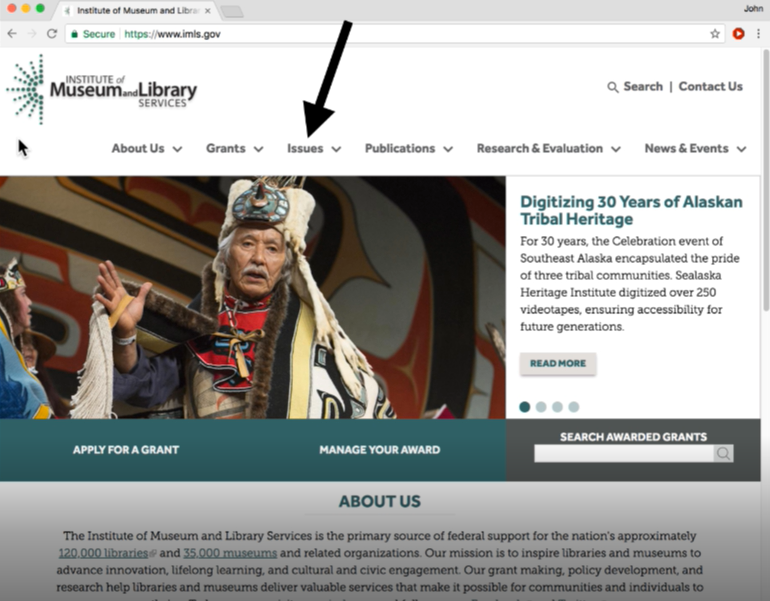

As you first land on the furniture website to look for chairs, your eyes scan the page to make sure you are on the right site. Your eyes might scan the page for words such as furniture, or for the word “chairs”, from which you might look for the appropriate category of chair, or you might choose to look for the search option to type in “Eames chair”. If you don’t find chair, you look for other words that might represent a category that includes chair. Let’s suppose on scanning the options below, you pick the “Living” option.

![]()

Figure 2.2: Navigation from Design within Reach

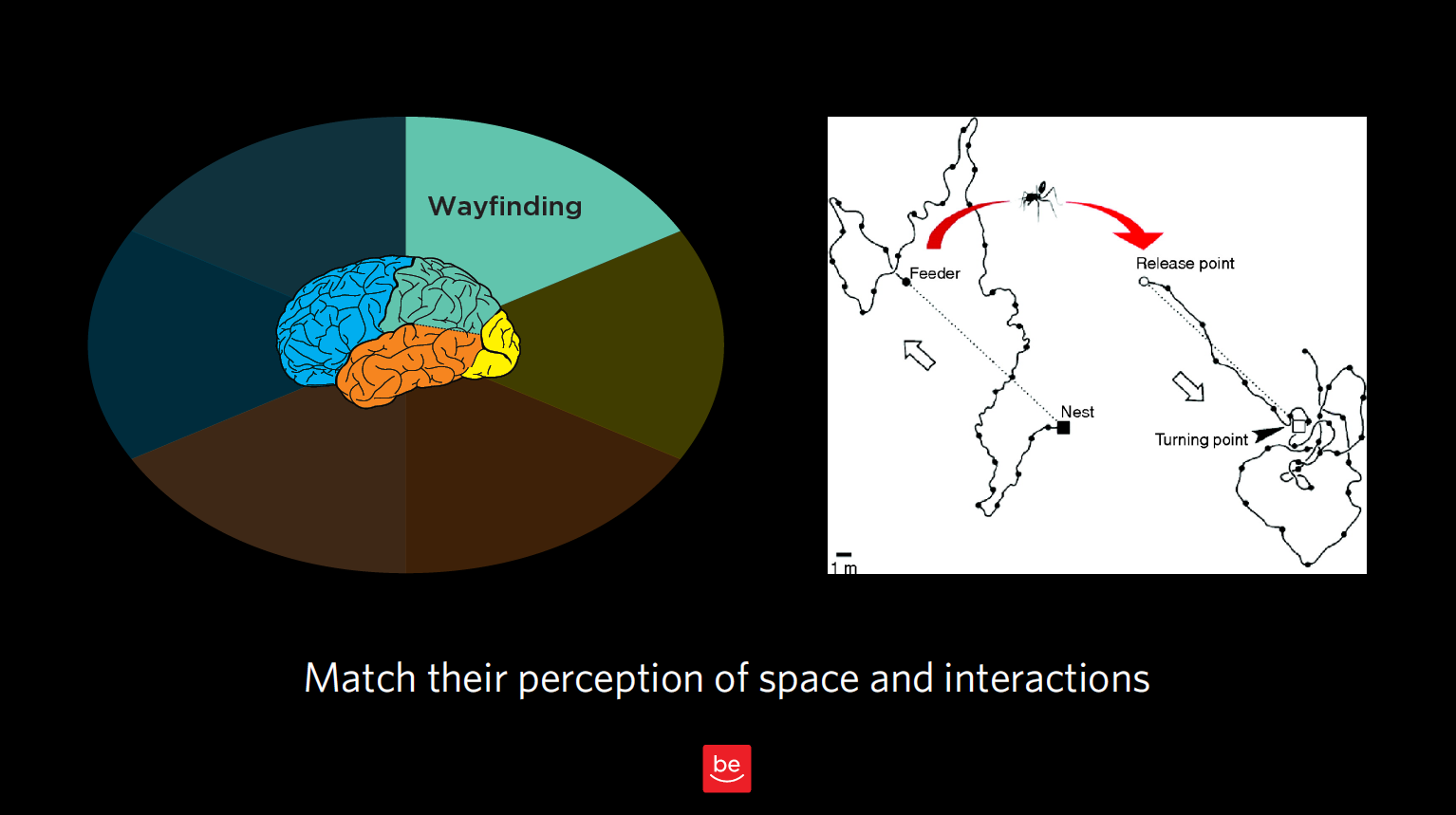

2. Wayfinding

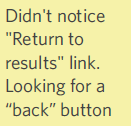

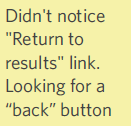

Once you believe you’ve found a way forward into the site, the next task is to understand how to navigate the virtual space. While in the physical world we’ve learned (or hopefully have learned!) the geography around our homes and how to get to some of our most frequented locations like our favorite grocery store or coffee shop, the virtual world may not always present our minds with the navigational cues that our brains are designed for — notably three-dimensional space.

We often aren’t exactly sure where we are within a website, app, or virtual experience. Nor do we always know how to navigate around in a virtual space. On a webpage you might think to click on a term, like “Living” in the option above. But in other cases like Snapchat or Instagram, many people over the age of 18 might struggle to understand how to get around by swiping, clicking, or even waving their phone. Both understanding where you are in space (real or virtual) and how you can navigate your space (moving in 3D, swiping or tapping on phones) are critical to a great experience.

3. Language

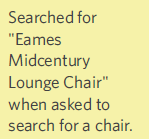

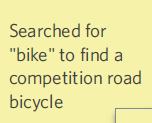

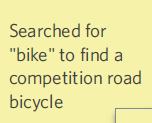

I find when I’m around interior designers, I start to wonder if they speak a different language altogether than I do. The words in a conceptual category such as furniture can vary dramatically based on your level of expertise. If you are an interior design expert, you might masterfully navigate a furniture site, because you know what distinguishes an egg chair, swan chair, diamond chair, and lounge chair. In contrast, if you are more novice to the world of interior design, you might need to Google all these names to figure out what they are talking about! To create a great experience, we must understand the words our audience uses and meet them at the appropriate level. Asking experts to simply look up the category “chair” (far too imprecise) is about as helpful as asking a non-expert about the differences between dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and anterior cingulate gyrus (both of which are neuroanatomical terms).

4. Memory

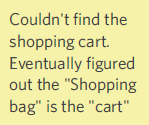

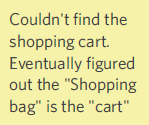

As I navigate an e-commerce site, I also have expectations about how it works. For example, I might expect that an e-commerce site will have search (and search results), product category pages (chairs), product pages (a specific chair), and a checkout process. The fact that you have expectations is true for any number of concepts. We automatically build mental expectations about people, places, processes, and more. As product designers, we need to make sure we understand what our customers’ expectations are, and anticipate confusions that might arise if we deviate from those norms (e.g., think about how you felt the first time you left a Lyft or Uber or limousine without physically paying the driver).

5. Decision-Making

Ultimately you are seeking to accomplish your goals and make decisions. Should you buy this chair? There are any number of questions that might go through your head as you make that decision. Would this look good in my living room? Can I afford it? Would it fit through the front door? At nearly $5,000, what happens if it is scratched or damaged during transit? Am I getting the best price? How should I maintain it? As product and service managers and designers, we need to think about all the steps along an individual customer’s mental journey and be ready to answer the questions that come up along the way.

Figure 2.3: Product detail page from Design with Reach

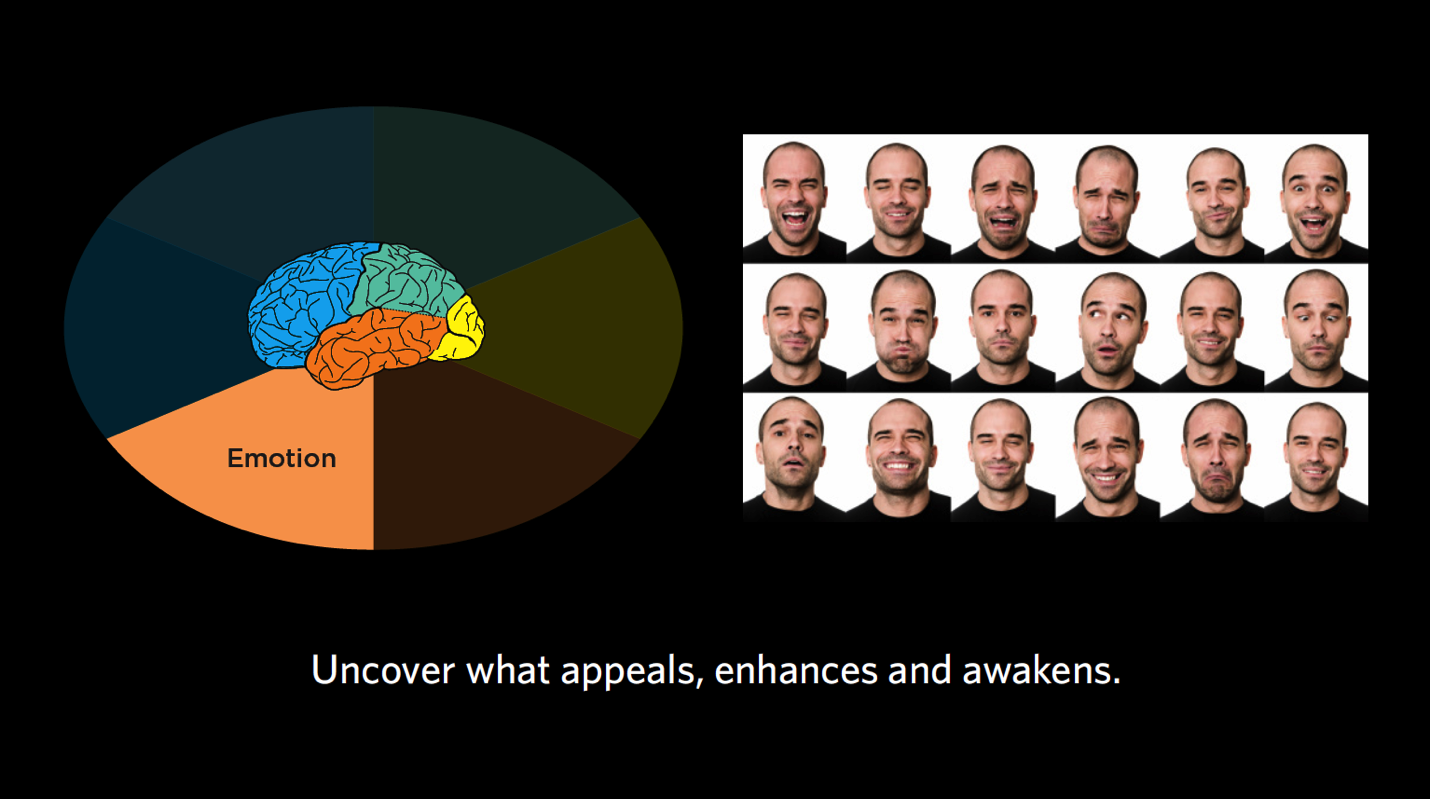

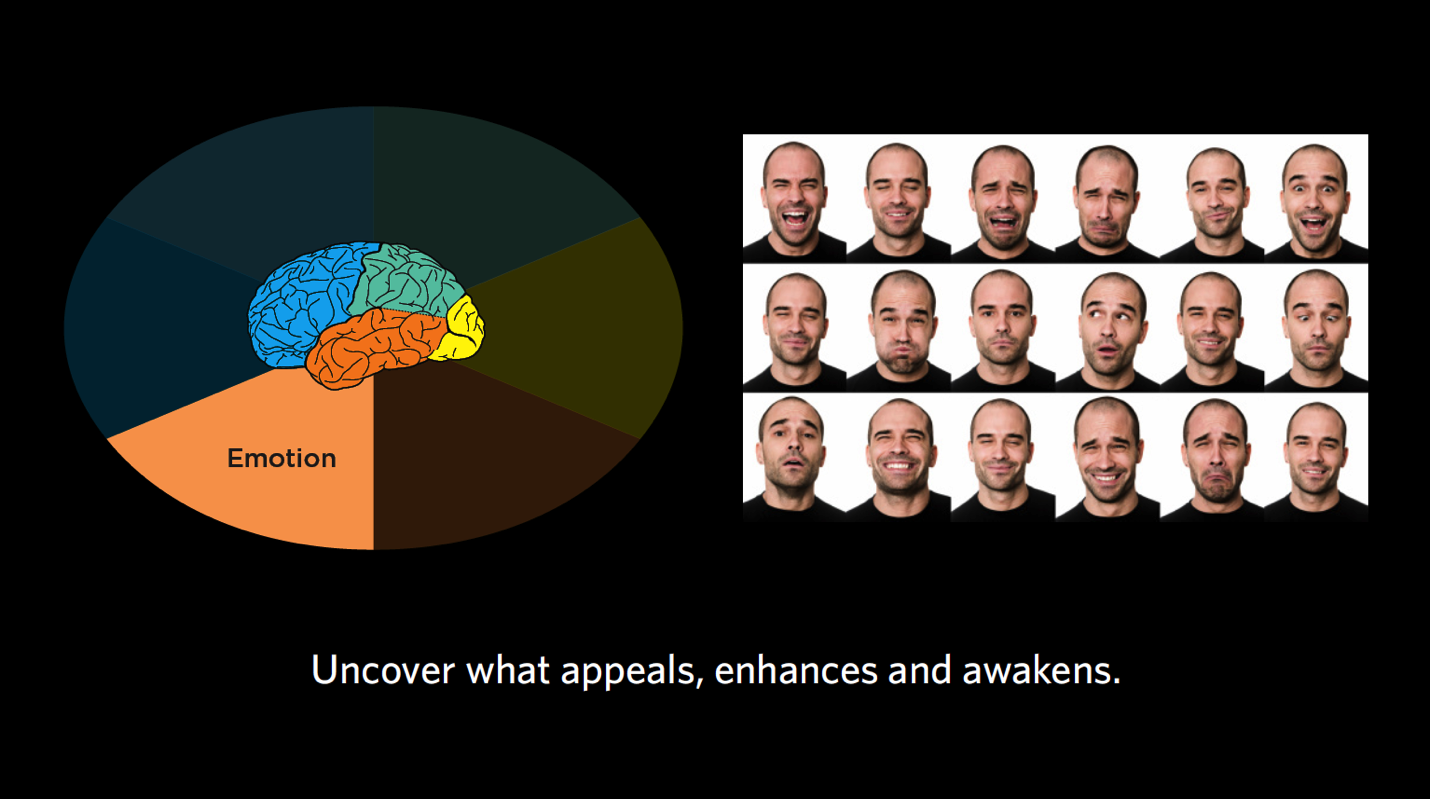

6. Emotion

While we may like to think we can be like Spock from Star Trek and make decisions completely logically, it has been well documented that a myriad of emotions affect our experience and thinking. Perhaps as you look at this chair you are thinking about how your friends would be impressed, and thinking that might show your status. Perhaps you’re thinking “How pretentious!” or “$5,000 for a chair — How am I going to pay for that, rent and food?!” and starting to panic. Identifying underlying emotions and deep-seated beliefs will be critical to building a great experience.

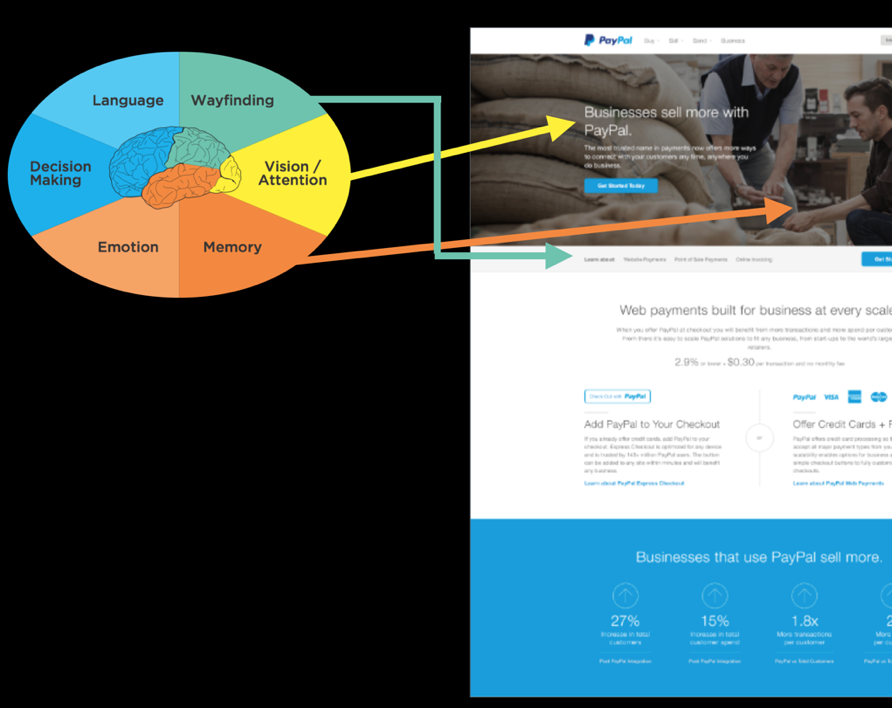

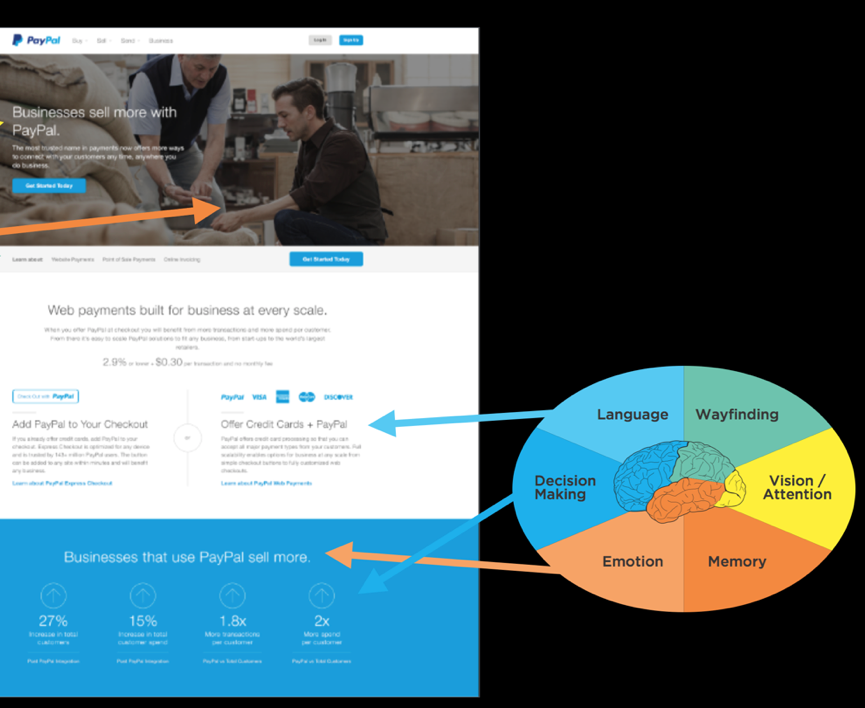

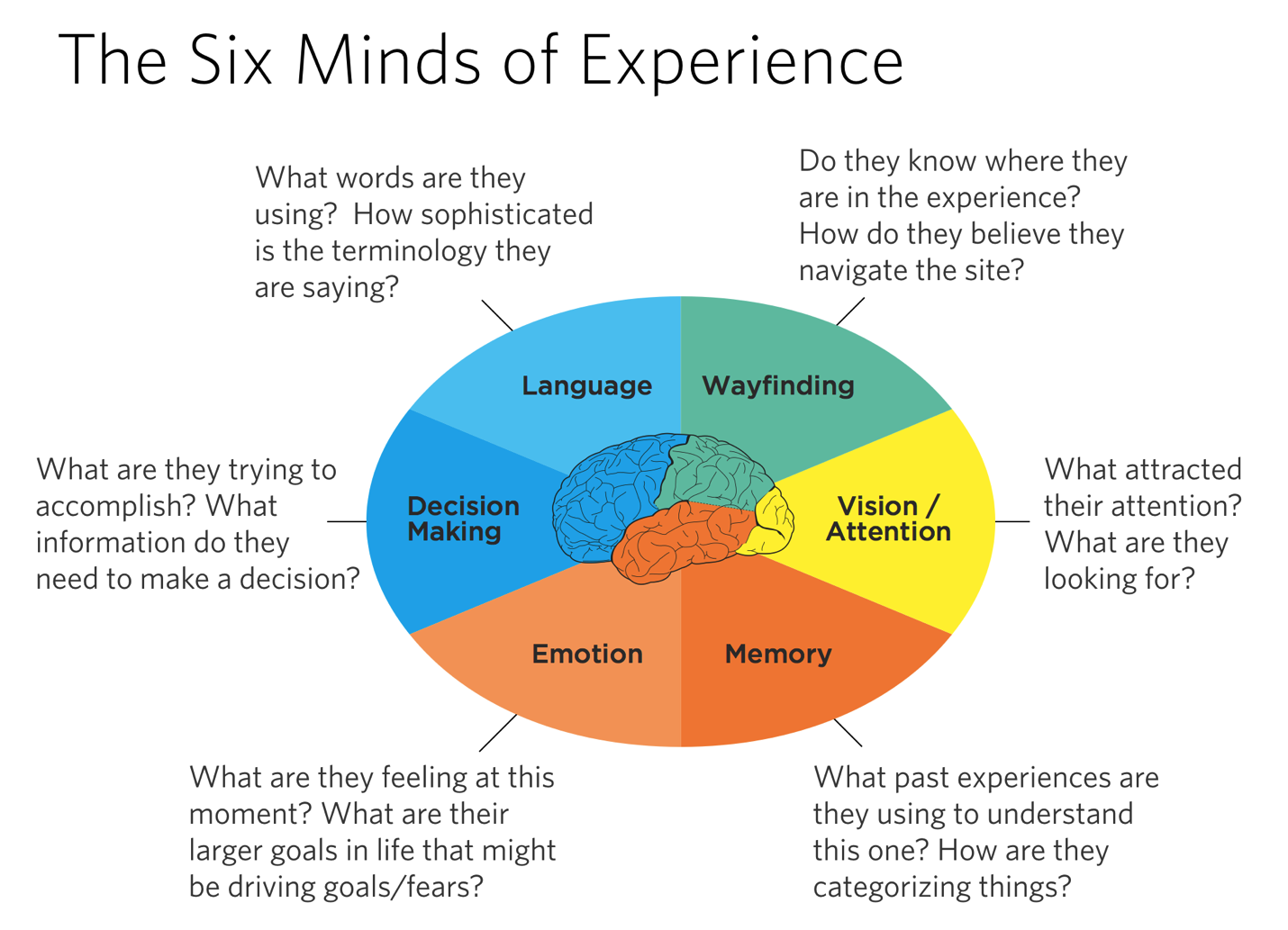

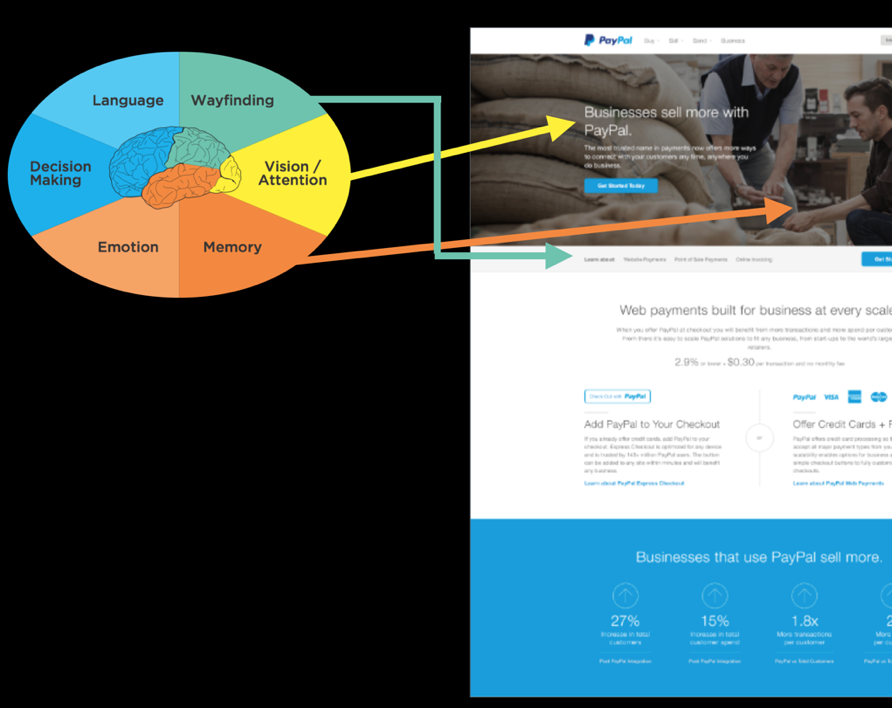

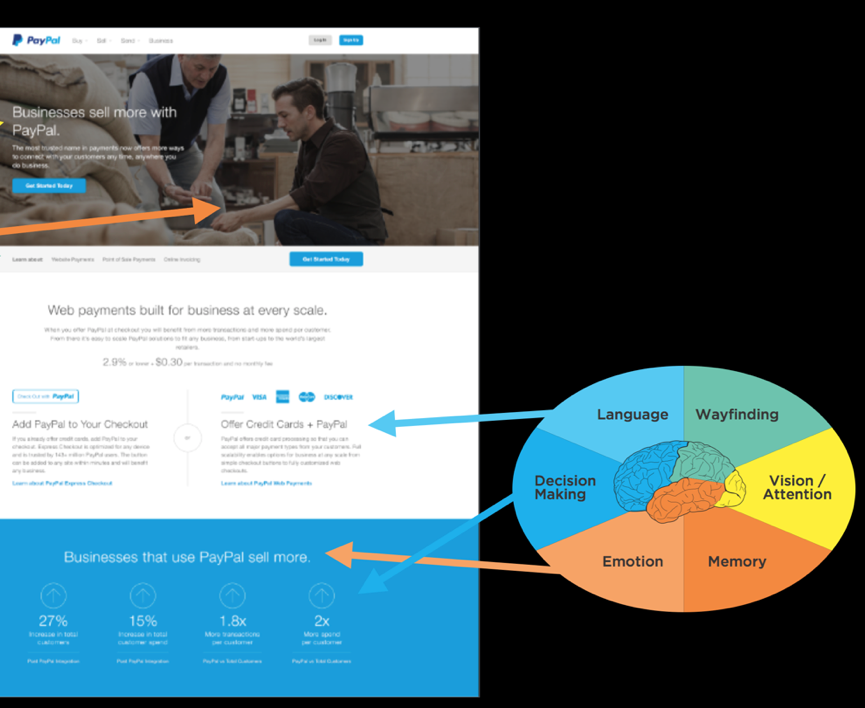

Figure 2.4: Six Minds of Experience

Together, these very different processes, which are generally located in unique brain areas, come together to create what you perceive as a singular experience. While my fellow cognitive neuropsychologists would quickly agree that this is an oversimplification of both human anatomy and processes, there are some reasonable overarching themes that make this a level at which we can connect product design and neuroscience.

I think we all might agree that “an experience” is not singular at all, but rather is multidimensional, nuanced, and composed of many brain processes and representations. It is multisensory. Customer experience doesn’t happen on a screen, it happens in the mind.

“The customer experience doesn’t happen on a screen, it happens in the mind.”

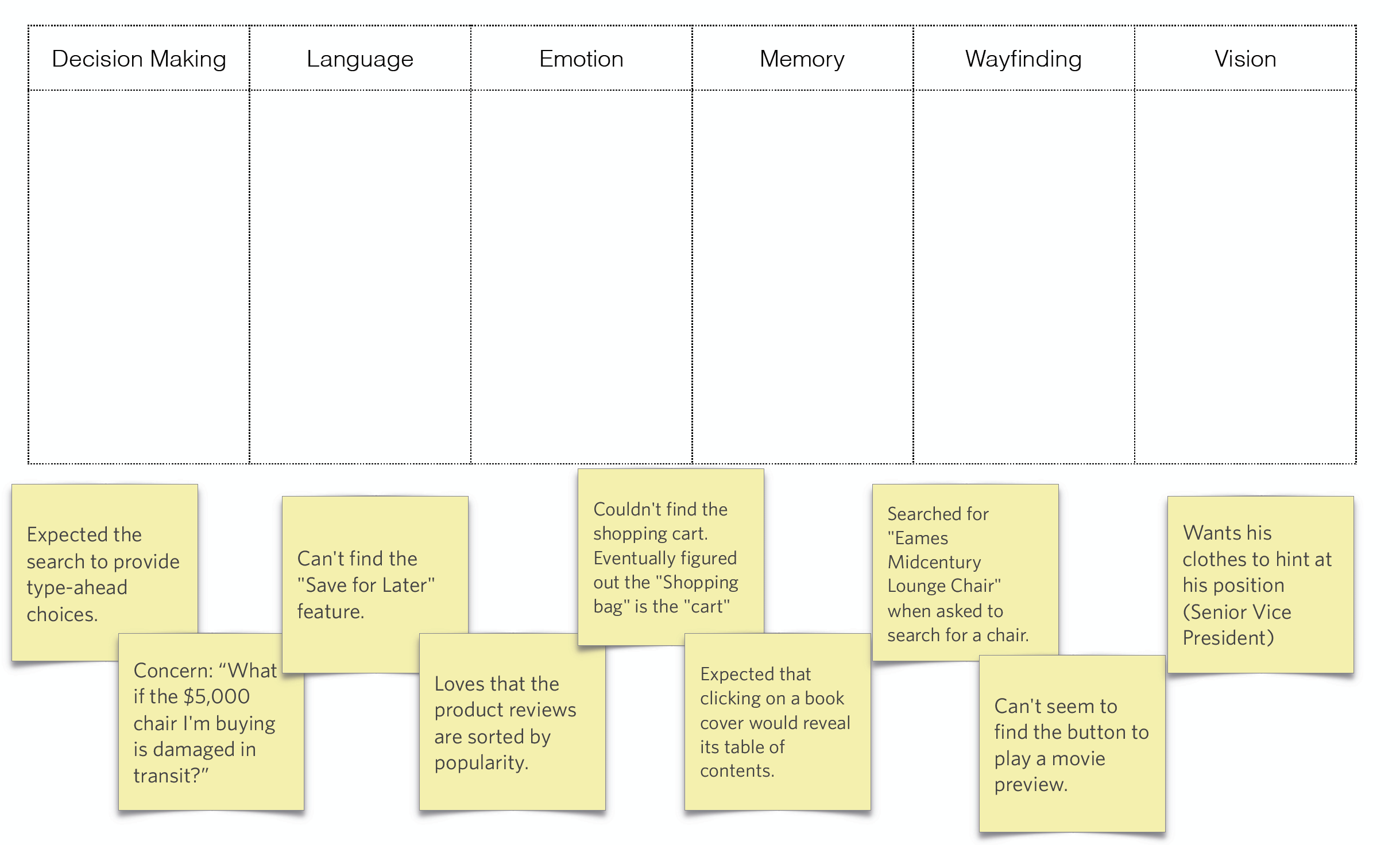

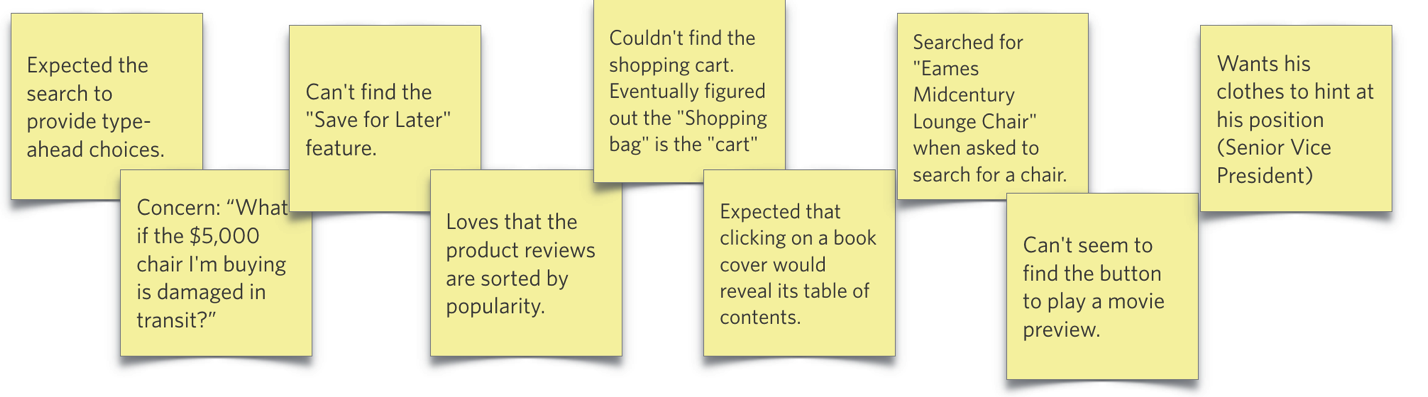

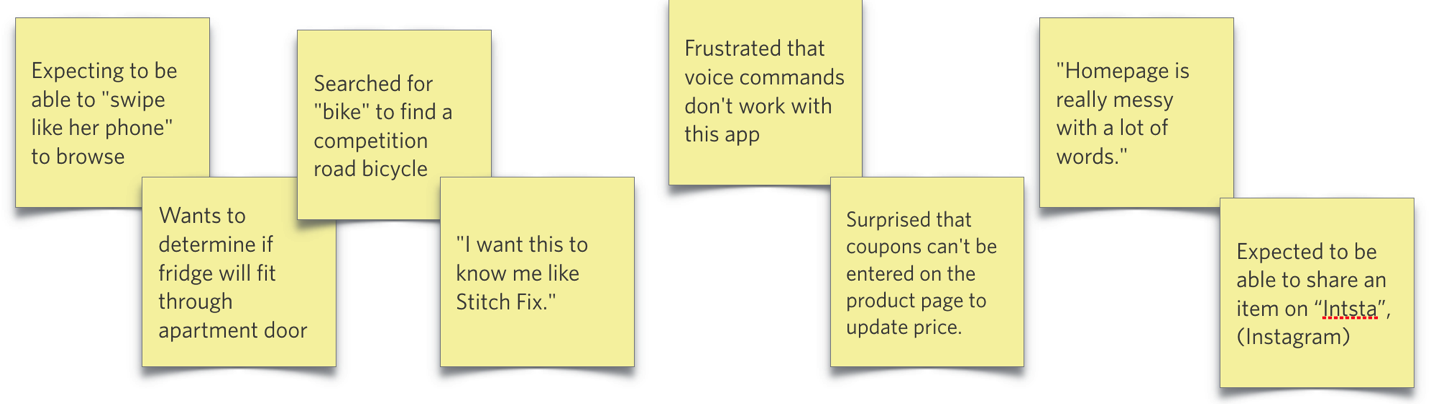

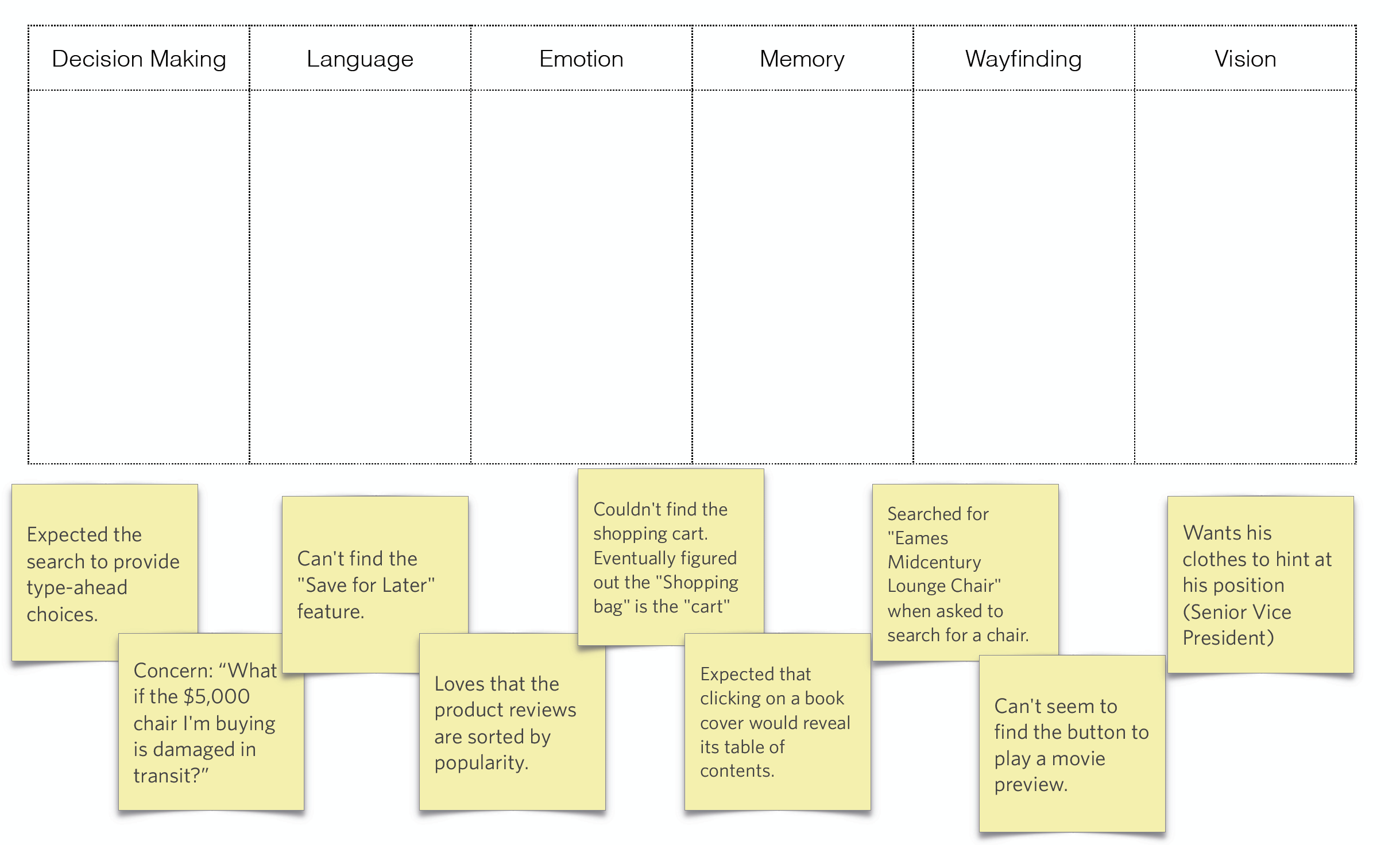

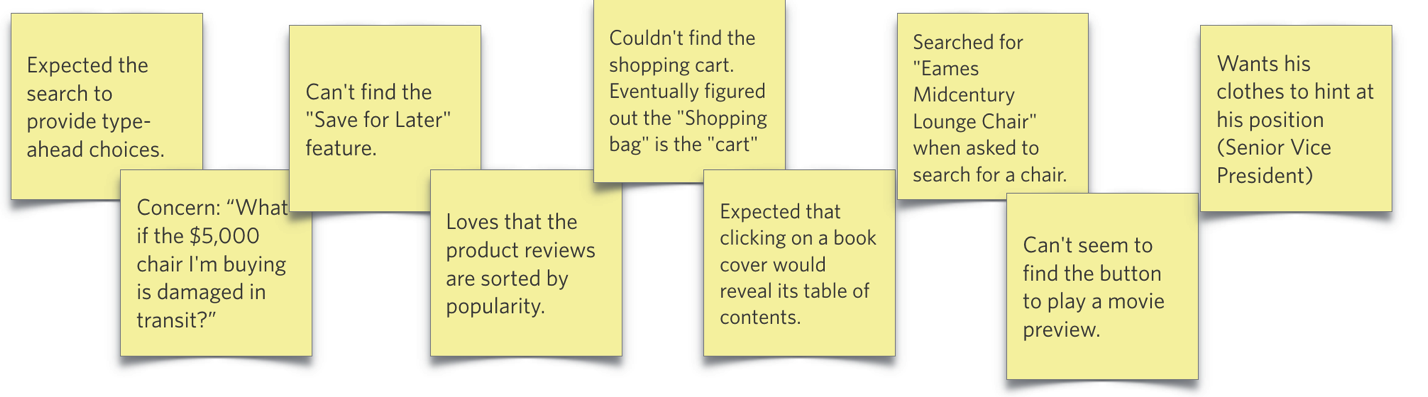

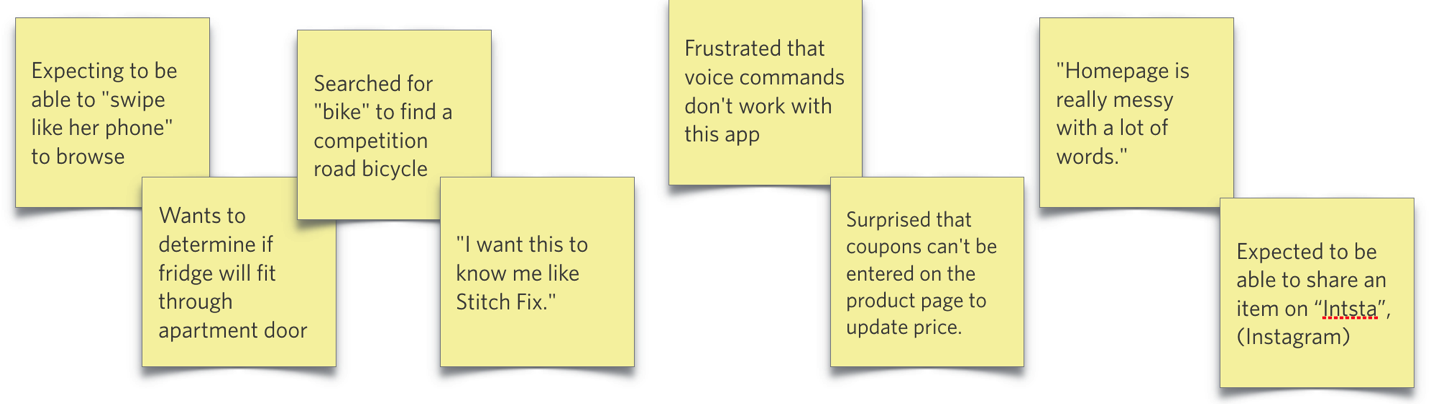

Activity

Let me recommend you take a brief pause in your reading, and go to an e-commerce website — ideally, one that you’ve rarely used — and search for books on the topic of “customer experience.” When you do, do so in a new and self-aware state:

Now that you have some sense of the mental representations you need to be aware of, you might ask: How do I, as a product manager, not a psychologist, determine where someone is looking and what they are looking for? How do I know what my product audience’s expectations are? How can I expose deep-seated emotions? We’ll get there in Part 2 of the book, but for right now I want to agree on what we mean by vision/attention, wayfinding, memory, language, emotion and decision making. I want you to know more about each of these so you can recognize these processes “in the wild” as you observe and interview your customers.

Chapter 3. In the Blink of an Eye: Vision, Attention, and Automaticity

From representations to experiences

Think of a time when you were asked to close your eyes for a big surprise (no peeking!), and then opened your eyes for the big reveal. At the moment you open your eyes you are taking in all kinds of sensations: light and dark areas in your scene, colors, objects (cake and candles?), faces (family and friends), sounds, smells, likely joy and other emotions. It is a great example of how instantaneous, multidimensional, and complex an experience can be.

Despite the vast ocean of input streaming in from our senses, we have the gift of nearly instant perception of an enormous portion of any given scene. It comes to you so naturally, yet is so difficult for a machine like a self-driving car. Upon reflection, it is amazing how ‘effortless’ these processes are. They just work. You don’t have to think about how to recognize objects or make sense of the physical world in three dimensions except in very rare circumstances (e.g., dense fog).

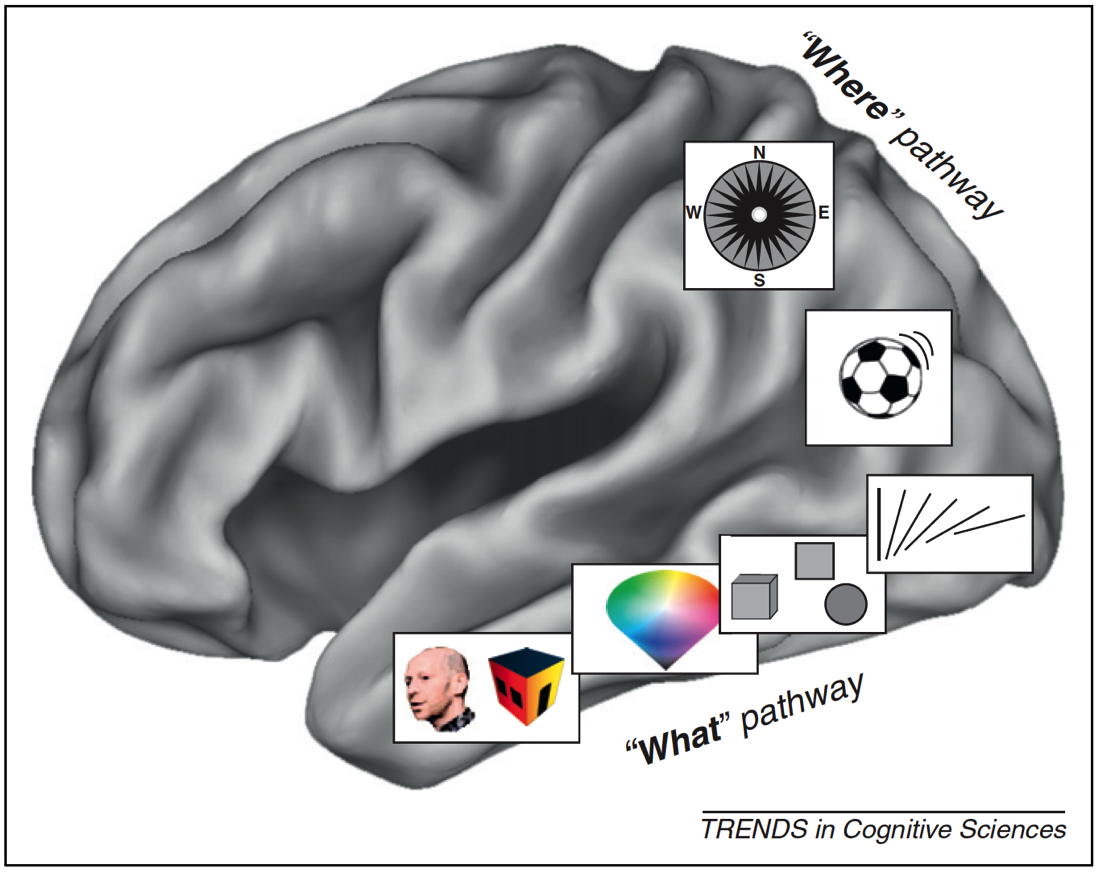

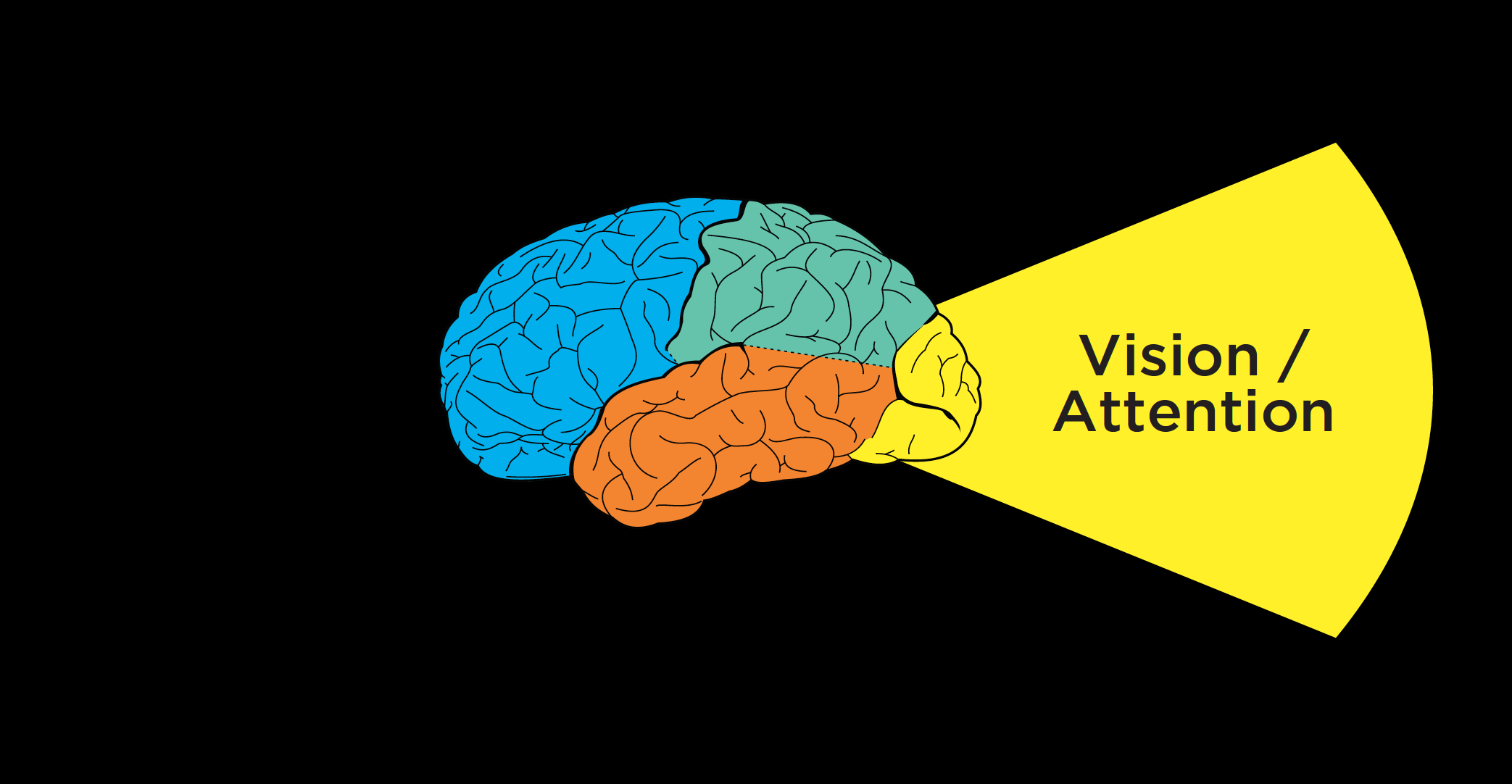

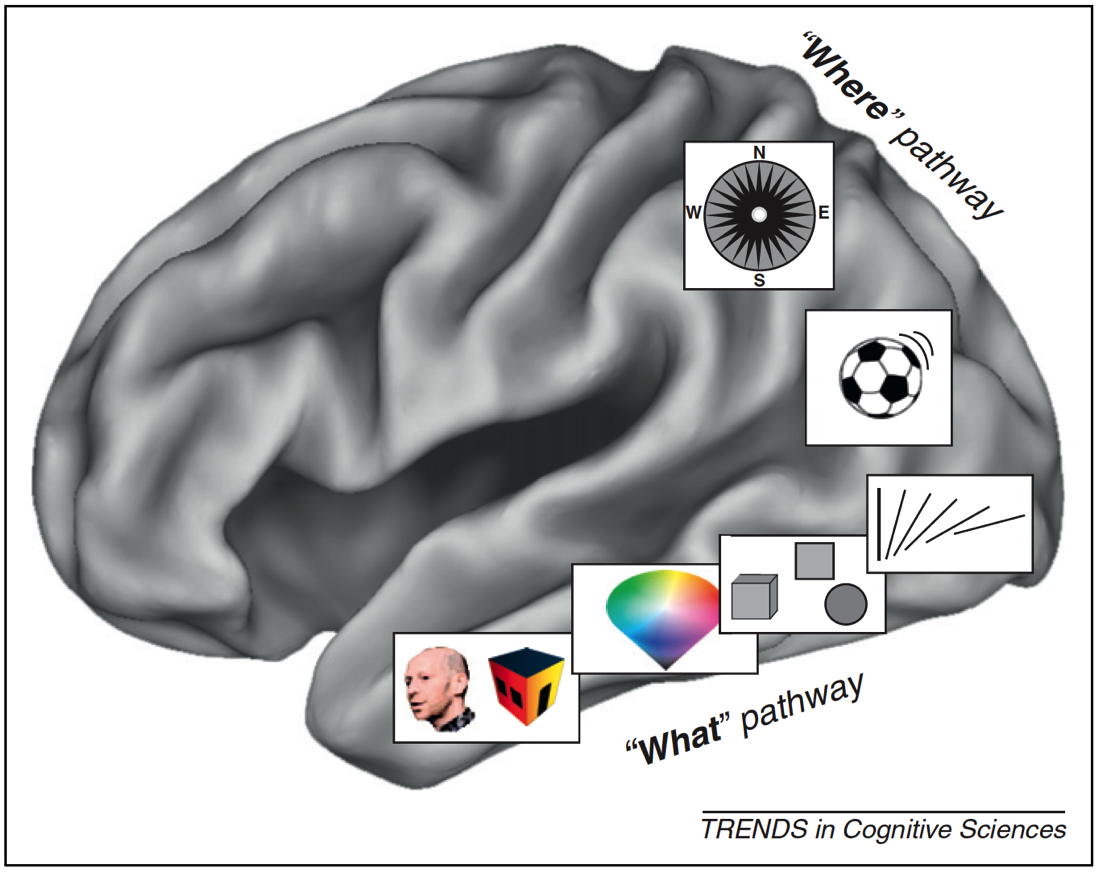

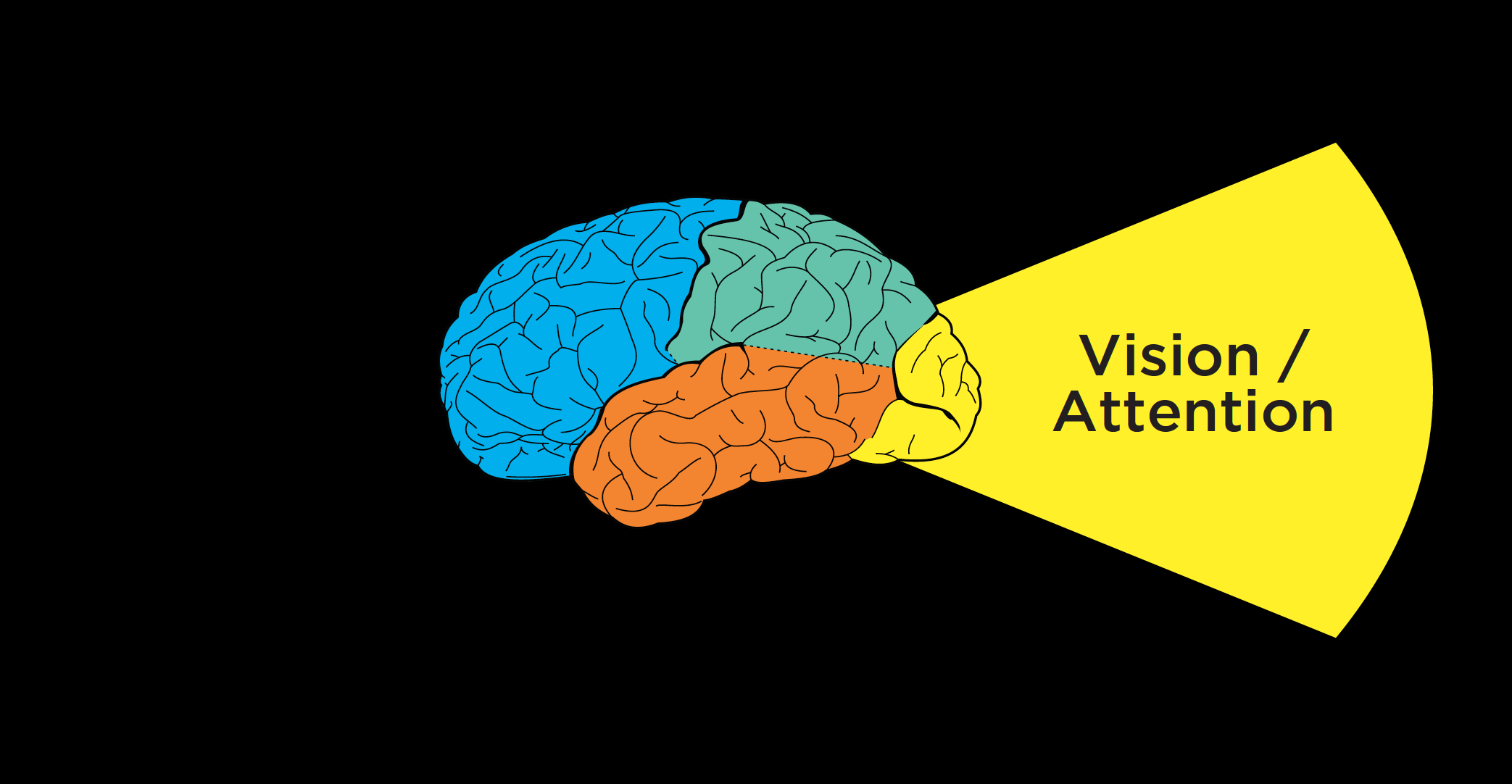

These automatic processes start with neurons in the back of your eyeballs, through your Corpus Callosum, to the back of your brain in the Occipital cortex, then your Temporal and Parietal lobes in near real-time. In this chapter we’ll focus on the “what” and in the next we’ll discuss the “where”.

Figure 3.1: What/Where Pathways

With almost no conscious control, your brain brings together separate representations of brightness, edges, lines, line orientation, color, motion, objects, and space (in addition to sounds, feelings, and proprioception) into a singular experience. We have no conscious awareness that we had separate and distinct representations, or that they were brought together into a single experience, or that past memories influences your perception, or that they evoked certain emotions.

This is a non-trivial accomplishment. It is incredibly difficult to build a machine that can mimic even the most basic differences between objects that have similar colors and shapes — for example, between muffins and Chihuahuas — which with a brief inspection you, as a human, will get correct every time.

Figure 3.2: Muffins or Chihuahuas?

There are many, many things I could share about vision, object recognition and perception, but the most important for our purposes are: (a) there are many processes taking place simultaneously, of which you have little conscious awareness or control, and (b) many computationally challenging processes are taking place constantly that don’t require conscious mental effort on your part.

In Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman’s fantastic book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” he makes the compelling point that there are two very different ways in which your brain works. You are aware and in conscious control over the first set of processes, which are relatively slow. And you have little to no conscious control or introspection, over the other set of processes, which are lightning-fast. Together, these two types of thinking encompass thinking fast (automatic processes) and thinking slow (conscious processing).

When designing products and services, we as designers are often very good at focusing on the conscious processes (e.g., decision-making), but we rarely design with the intention of engaging our fast automatic processes. They occur quickly and automatically, and we almost “get them for free” in terms of the mental effort we need to expend as we use them. As product designers, we should harness both these automatic systems and conscious processes because they are relatively independent. The former don’t meaningfully tax the latter. In later chapters, we’ll describe exactly how to do so in detail, but for now let’s discuss one good example of an automatic visual process we can harness: visual attention.

Unconscious behaviors: Caught you looking

Think back to the vignette I gave you at the start of the chapter: Opening your eyes for that big surprise. If you try covering your eyes now and suddenly uncovering them, you may find that your eyes dart around the scene. In fact, that is consistent with your typical eye movements. Eyes don’t typically move in a smooth pattern. Rather, they jump from location to location (something we call saccades). This motion can be measured using specialized tools like an infrared eye-tracking system, which can now be built into specialized glasses, or a small strip under a computer monitor.

Figure 3.3: Tobii Glasses II

Figure 3.4: Tobii X2-30 (positioned below the computer screen)

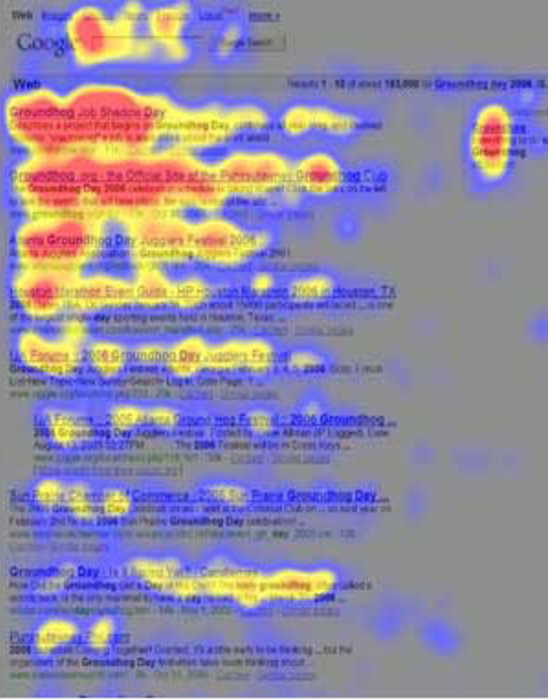

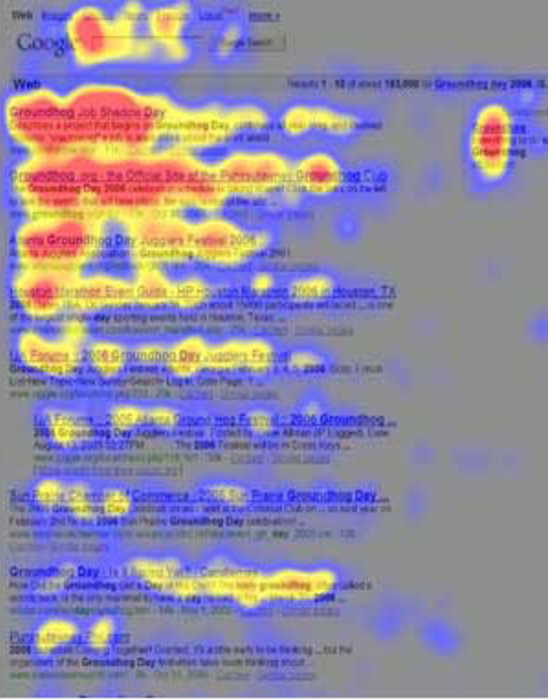

These tools have documented what is now a well-established pattern of eye movements on things like web pages and search results. Imagine that you just typed in a Google search and are viewing the results on a laptop. On average we tend to look 7 to 10 words into the first line of the results, 5 to 7 words into the next line, and even fewer words into the third line of results. There is a characteristic “F-shaped” pattern that our eye movements (saccades) form. Looking at the image below, the more red the value, the more time was spent on that part of the screen.

Figure 3.5: Heatmap of search eye-tracking “F” Pattern

[Source: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/f-shaped-pattern-reading-web-content/]

Visual Popout

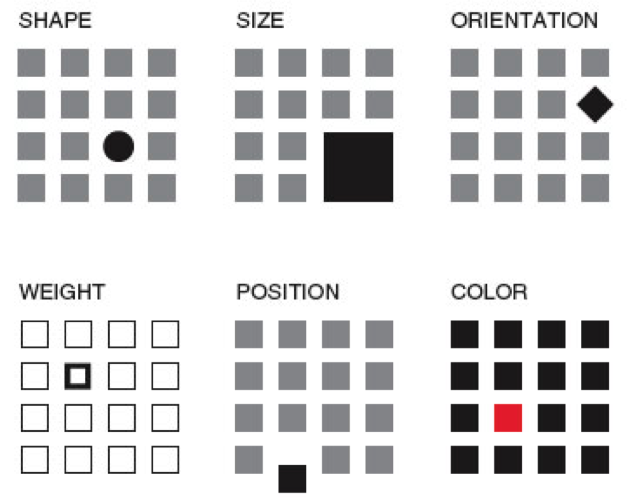

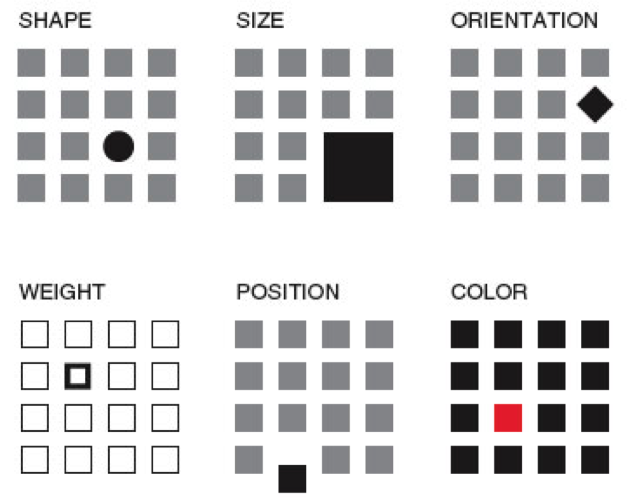

While humans are capable of controlling our eye movements, much of the time we let our automatic processes take charge. Having our eye movements on “autopilot” works well in part, because things in our visual field strongly attract our attention when they stand out from the other features in our visual scene. These outliers automatically “pop out” to draw your attention and eye movements.

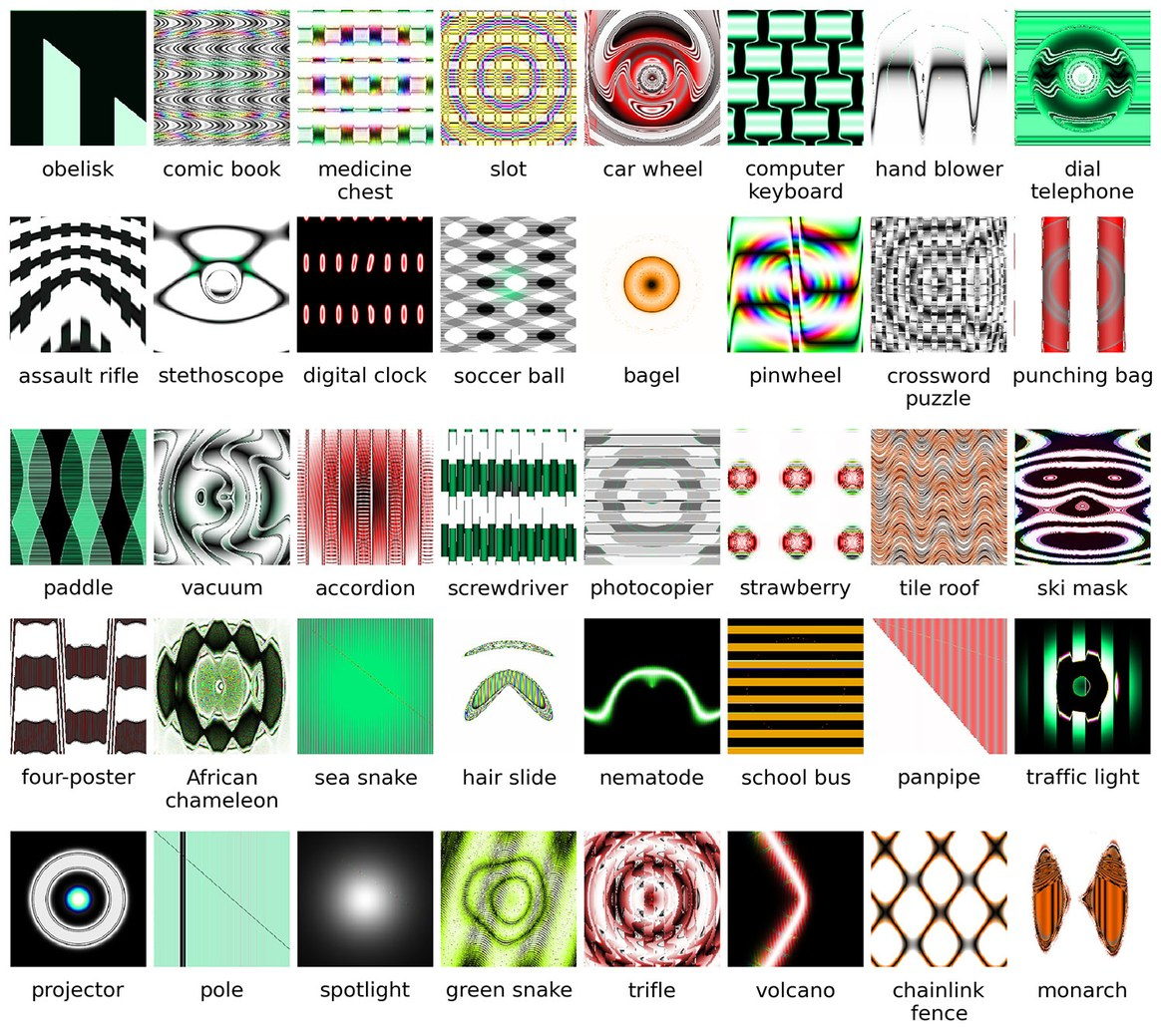

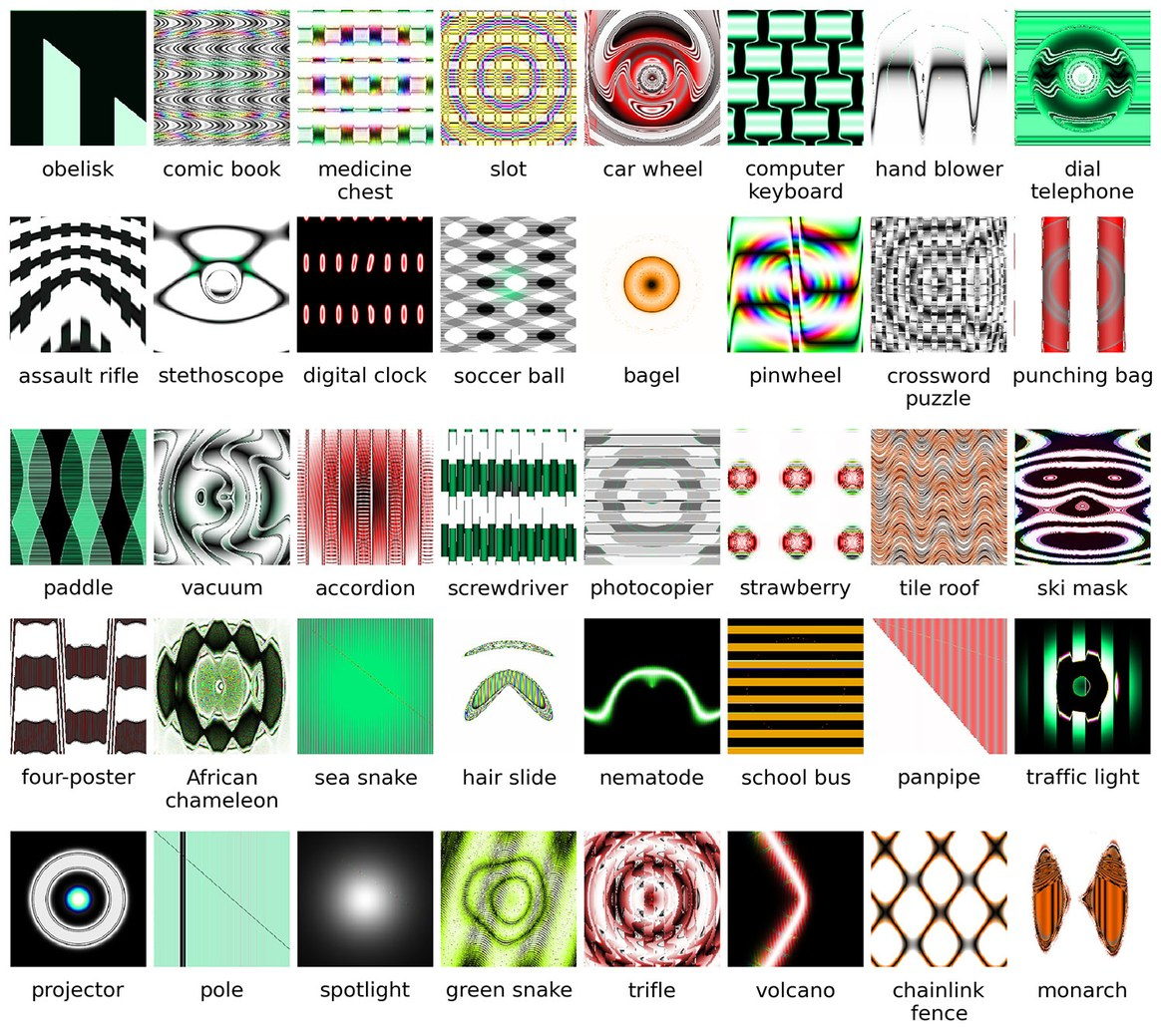

As product designers, we often fail to harness this powerful automatic process. Sesa you might have learned from Sesame Street: “One of these things is not like the other, one of these things just doesn’t belong...” is a great way to draw attention to right elements in a display. Some of the ways something can pop out in a scene are demonstrated below. An important feature I would add to the list below is visual contrast (relative bright and dark). The items below that are unique pop out in this particular case because they have both a unique attribute (e.g., shape, size, orientation) and a unique visual contrast relative to the others in their groupings.

Figure 3.6: Visual Popout

One interesting thing about visual popout is that the distinctive element draws attention regardless of the number of competing elements. In a complex scene (e.g., modern car dashboards), this can be an extremely helpful method of directing one’s attention when needed.

If you are an astute reader thinking about the locus of control with eye movements, one question you might have is who decides where to look next if you aren’t consciously directing your eyes? How exactly do your eyes get drawn to one part of a visual scene? It turns out that your visual attention system — the system used to decide where to take your eyes next — forms a blurry (somewhat Gaussian), and largely black-and-white representation of the scene. It uses that representation, which is constantly being updated, to decide where the locus of your attention should be, provided you are not directing your eyes (that is, “conscious you”).

You can anticipate where someone’s eyes might go in a visual scene if you take that scene and use a program like Photoshop to turn down the color of a design and you squint your eyes (and/or use more than one Gaussian blur using that design program). That test will give you a pretty good guess where people’s eyes will be drawn in the scene, were you to measure their actual eye gaze pattern using an eye tracking device.

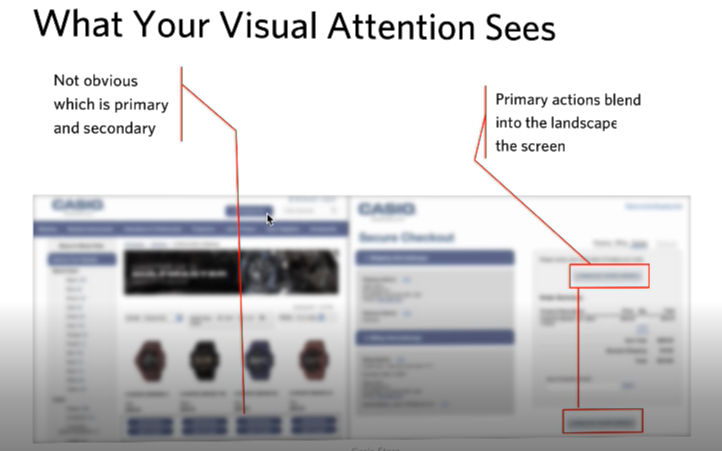

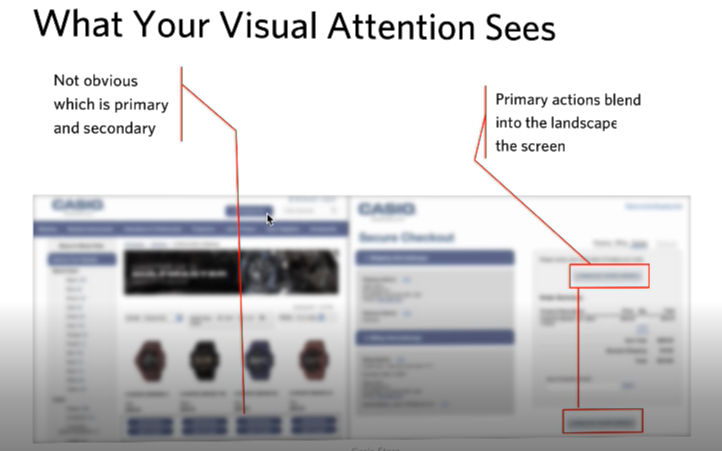

Oops, you missed that!

One of the most interesting results you get from studying eye movements is the null result: that is, what people never look at. For example, I’ve seen a web form design in which the designers tried to put helpful supplemental information in a column off to the side on the right of the screen — exactly where ads are typically placed. Unfortunately, we as consumers have been trained to assume that information on the right side of the screen is an ad or otherwise irrelevant, and as a result will simply ignore anything in that location (helpful or not). Knowing about past experiences will surely help us to anticipate where people are looking and help to craft designs in a way that actually directs — not repels — attention to the helpful information.

If your customers never look at a part of your product or screen, then they will never know what is there. You might as well have never put the information there to begin with. However, when attentional systems are harnessed correctly through psychology-driven design, there is amazing potential to draw people’s attention to precisely what they need. This is the opportunity we as product designers should always employ to optimize the experience.

Ceci n’est pas une pipe: Seeing what we understand something to be, not what might actually be there

Whether we present words on a page, image, or chart, the displayed elements are only useful to the extent the end users recognize what they’re seeing.

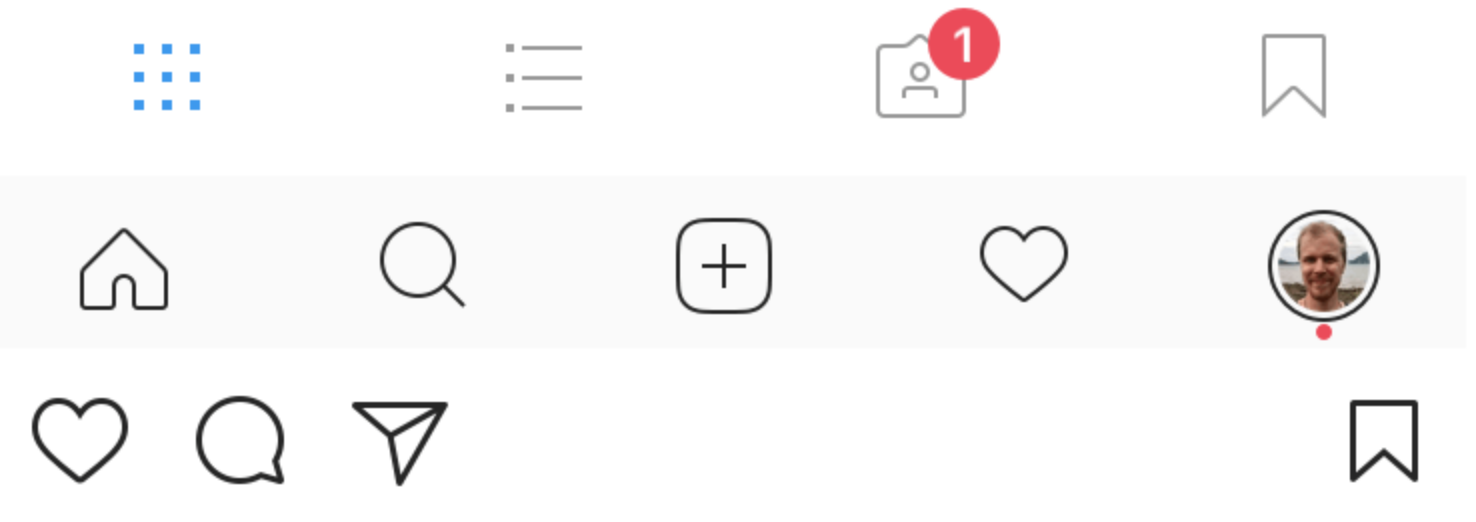

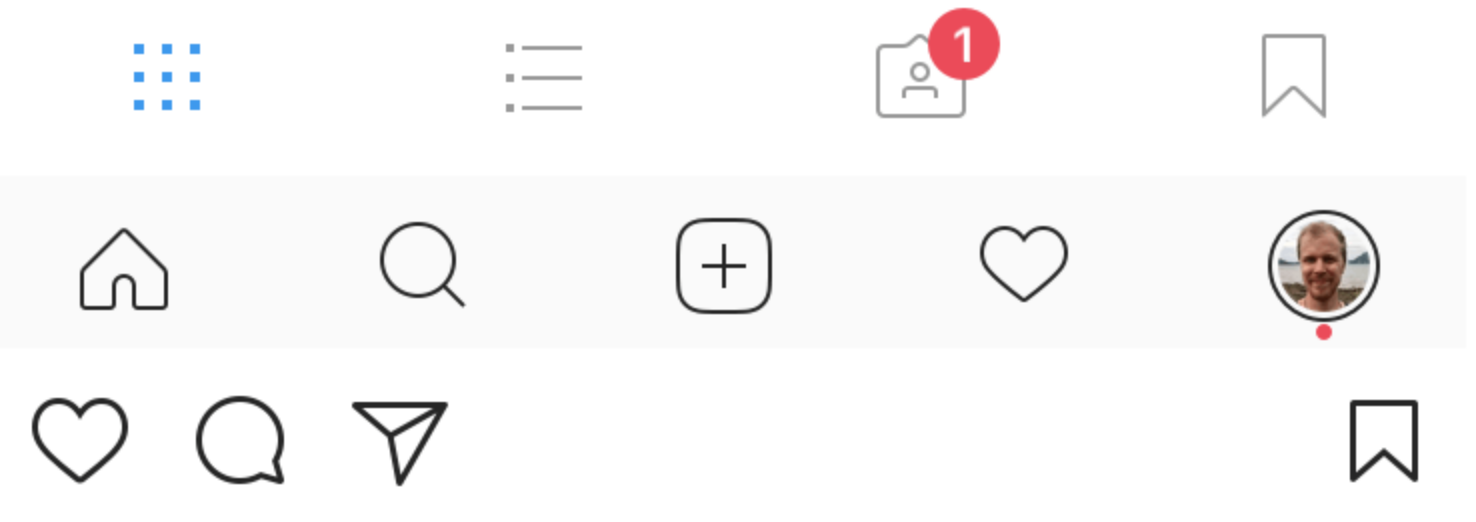

Figure 3.7: Instagram Controls

Figure 3.7: Instagram Controls

Icons are a particularly good example. If you ask someone who has never used Instagram what each of the icons above represent, I’m willing to bet they won’t correctly guess what each icon means without some trial and error. If someone interprets an icon to mean something, for that person, that is effectively its meaning at that moment (regardless of what it was meant to represent). As a design team, it is essential to test all of your visuals and make sure they are widely recognized or, if absolutely needed, that they can be learned with practice. When in doubt, do not battle standards to be different and creative. Go with the standard icon and be unique in other ways.

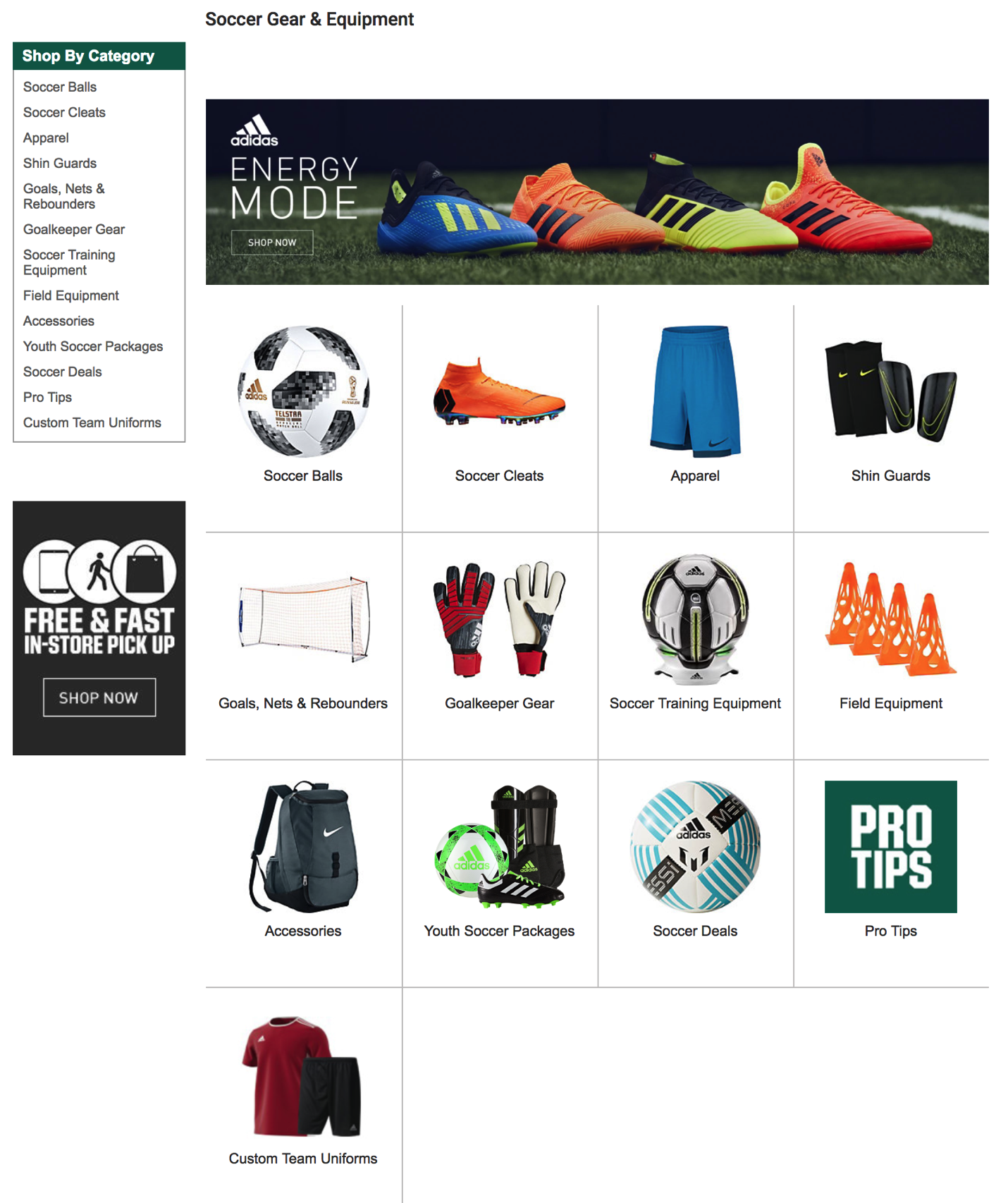

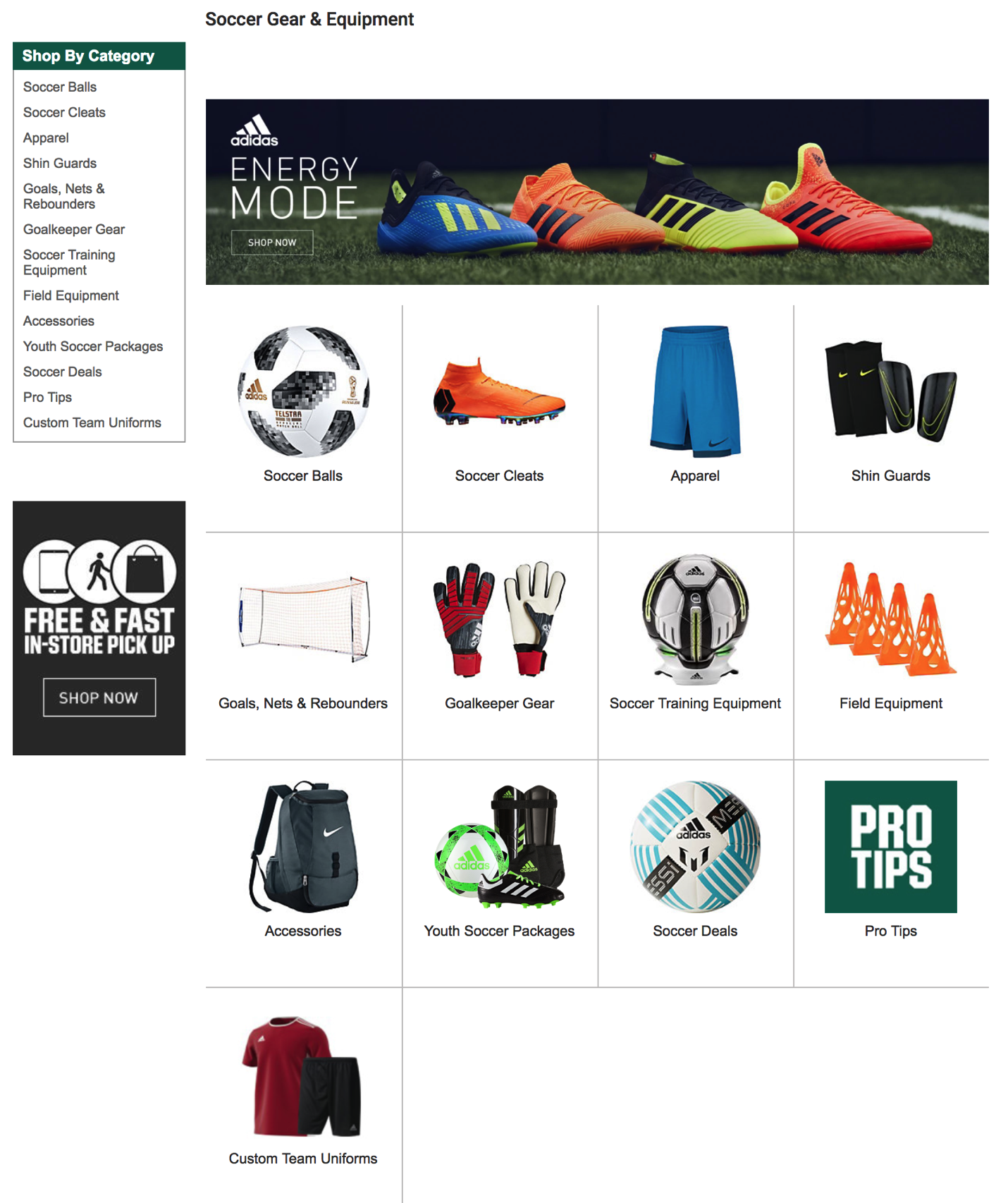

We’ve also seen a case where participants in eye tracking research thought that a sporting goods site only offered three soccer balls because only three (of the many that were actually for sale) were readily visible on the “soccer” screen.

Figure 3.8: Sporting Goods Store Layout

Visual designs are only useful to the extent that they invoke the understanding you were hoping they would. If they don’t, then any of the other elements (or meanings) that you created simply don’t exist.

How our visual system creates clarity when there is none

Before we move on to other systems, I can’t resist sharing one more characteristic of human vision — specifically, about visual acuity. When looking at a scene, our subjective experience is that all parts of that scene are equally clear, in focus, and detailed. In actuality, both your visual acuity and ability to perceive color drop off precipitously from your focal point (what you are staring at). Only about 2° of visual angle (the equivalent of your two thumbs at arms-length distance) are packed with neurons and can provide both excellent acuity and strong color accuracy.

Don’t believe me? Go to your closest bookshelf. Stare at one particular book cover and try to read the name of the book that is two books over. You may be shocked to realize you are unable to do so. Go ahead, I’ll wait!

Just a few degrees of visual angle from where our eyes are staring (foveating), our brains make all kinds of assumptions as to what is there, and we are unable to read it or fully process it. This makes where you are looking turn out to be crucial for an experience. Nearby just doesn’t cut it!

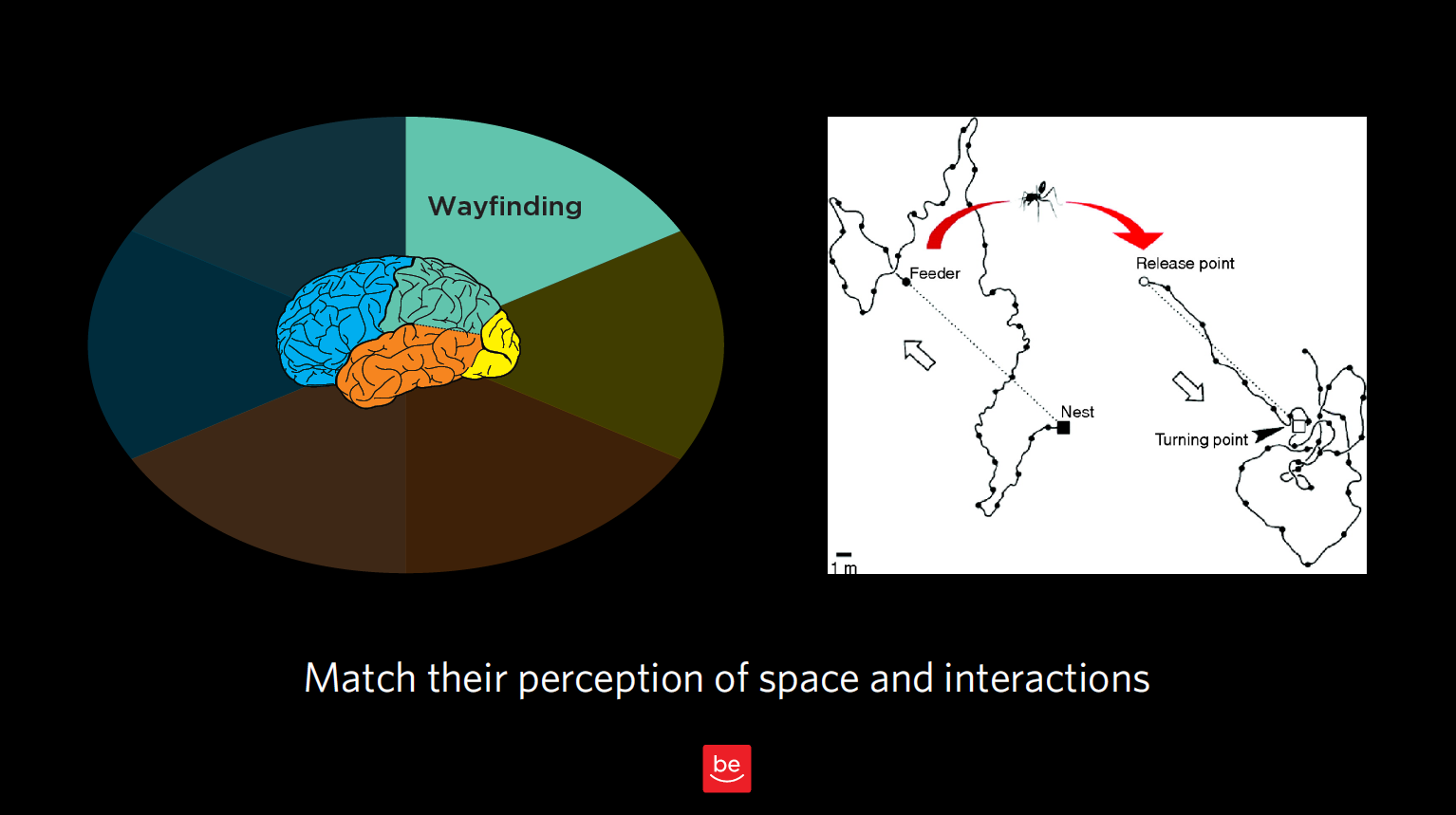

Chapter 4. Wayfinding: Where Am I?

A logical extension to thinking about what we are looking and where our attention is drawn to and how we represent the space around us and where we are within that space. A large portion of the brain is devoted to this “where” representation in the brain, so we ought to discuss it and consider how this cognitive process might be harnessed in our designs from two respects: knowing where we are, and knowing how we can move around in space.

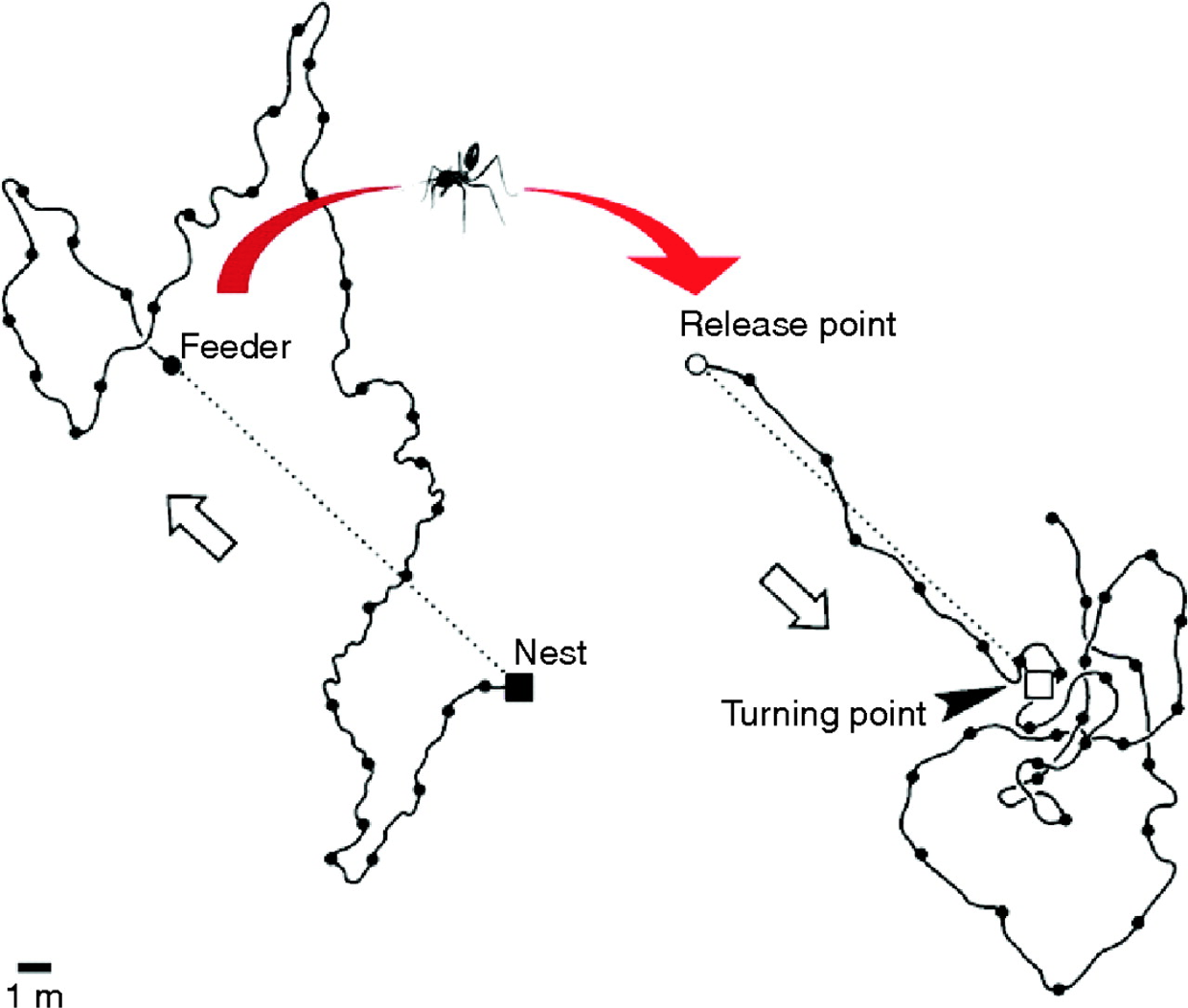

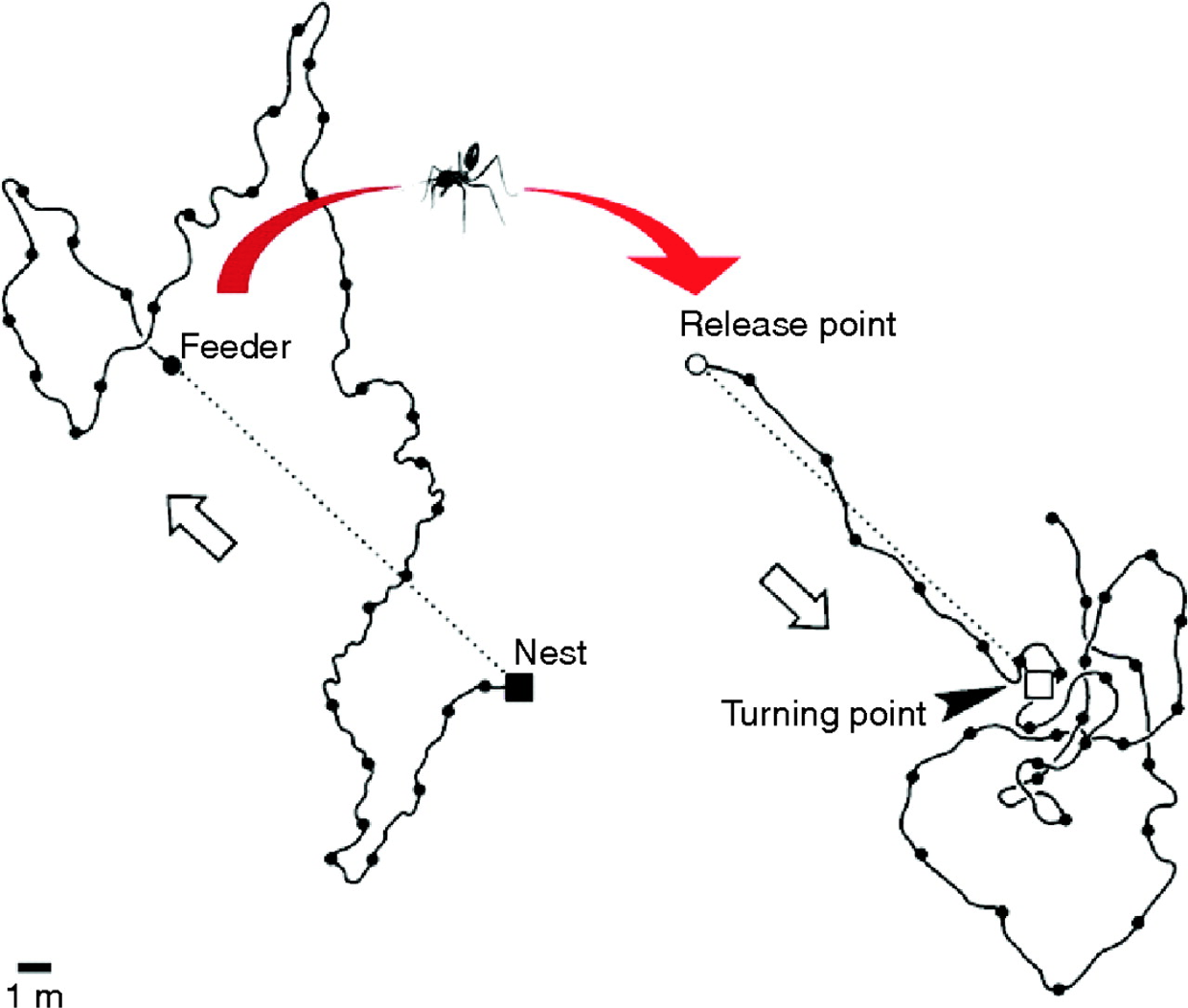

The ant in the desert: Computing Euclidean space

To help you think about the concept of wayfinding, I’m going to tell you about large Tunisian ants in the desert — who interestingly share an important ability that we have, too! I first read about this and other amazing animal abilities in Randy Gallistel’s The Organization of Learning, which suggests that living creatures great and small share many more cognitive capabilities than you might have first thought. Representations of time, space, distance, light and sound intensity, and proportion of food over a geographic area are just a few examples of computations many creatures are capable of.

It turns out that as a big Tunesian ant – but still a very small one in a very large desert – determining your location is a particularly thorny problem. These landscapes have no landmarks like trees, and deserts can frequently change their shape in the wind. Therefore, ants that leave their nest must use something other than landmarks to find their way home again. Their footprints, any landmarks, and scent in the sand are all unreliable as they can change with a strong breeze.

Furthermore, these ants take meandering walks in the Tunisian desert scouting for food (in this case in the diagram below, the ant is generally heading north west from his nest). In this experiment, a scientist has left out a bird feeder full of sweet syrup. This lucky ant climbs into the feeder, finds the syrup and realizes he just found the motherload of all food sources. After sampling the syrup, he can’t wait to tell fellow ants about the great news! However, before he does, the experimenter picks up the feeder (with the ant inside) and moves it East about 12 meters (depicted by the red arrow in diagram).

Figure 4.1: Tunisian Ant in the Desert

The ant, still eager to spread the good news with everyone at home, attempts to make a bee-line (or “ant-line”), back home. The ant heads straight southeast, almost exactly in the direction where the anthill should have been, had he not been moved. He travels approximately the distance needed, then starts walking in circles to spot the nest (which is a sensible strategy given there are no landmarks). Sadly, this particular ant doesn’t take into consideration being picked up, and so is off by exactly the amount the experimenter moved the feeder.

Nevertheless, this pattern of behavior demonstrates that the ant is capable of computing the net direction and distance traveled in Euclidean space (using the sun no less) and is a great example of what our parietal lobes are great at computing.

Locating yourself in physical and virtual space

Just like that ant, we all have to determine where we are in space, where we want to go, and what we must do in order to get to our destination. We do this using the “where” system in our own brains, which is itself located in our parietal lobes — one of the largest regions of the mammalian cerebral cortex.

If we have this uncanny, impressive ability to map space in the physical world built into us, wouldn’t it make sense if we as product and service designers tapped into its potential when it comes to wayfinding in the digital world?

(Note: If you feel like you’re not good with directions, you might be surprised to find you’re better than you realize. Just think about how you walk effortlessly to the bathroom in the morning from your bed without thinking about it. If it is of any solace, know that like the ant, we were never designed to be picked up by a car and transported into the middle of a parking lot that has very few unique visual cues.)

As I talk about “wayfinding” in this book, please note that I’m linking two concepts which are similar, but do not necessarily harness the same underlying cognitive processes:

There is an overlap between the two, but as we study this more carefully, we’ll see that this is not a simple one-to-one mapping. The virtual world in most of today’s interfaces on phones and web browsers strips away many wayfinding landmarks and cues. It isn’t always clear where we are within a web page, app, or virtual experience, nor it is always clear how to get where we want to be (or even creating a mental map of where that “where” is). Yet understanding where you are and how to interact with the environment (real or virtual) in order to navigate space is clearly critical to a great experience.

Where can I go? How will I get there?

In the physical world, it’s hard to get anywhere without distinct cues. Gate numbers at airports, signs on the highway, and trail markers on a hike are just a few of the tangible “breadcrumbs” that (most of the time) make our lives easier.

Navigating a new digital interface can be like walking around a shopping mall without a map: it is easy to get lost because there are so few distinct cues to indicate where you are in space. Below is a picture of a mall near my house. There are about eight hallways that are nearly identical to this one. Just imagine your friend saying “I’m near the tables and chairs that are under the chandeliers” and then trying to find your friend!

Figure 4.2: Westfield Montgomery Mall

To make things even harder, unlike the real world, where we know how to locomote by walking, in the digital world, the actions we need to take to get to where we are going sometimes differ dramatically between products (e.g., apps vs. operating systems). You may need to tap your phone for the desired action to occur, shake the whole phone, hit the center button, double tap, control-click, swipe right, etc.

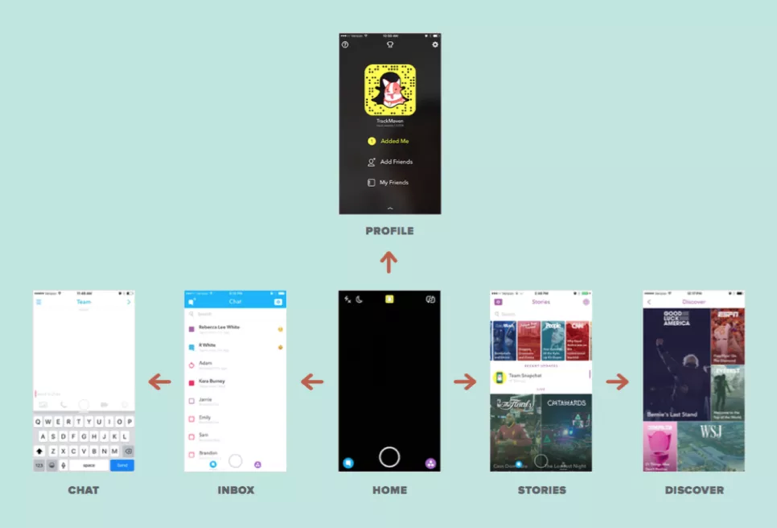

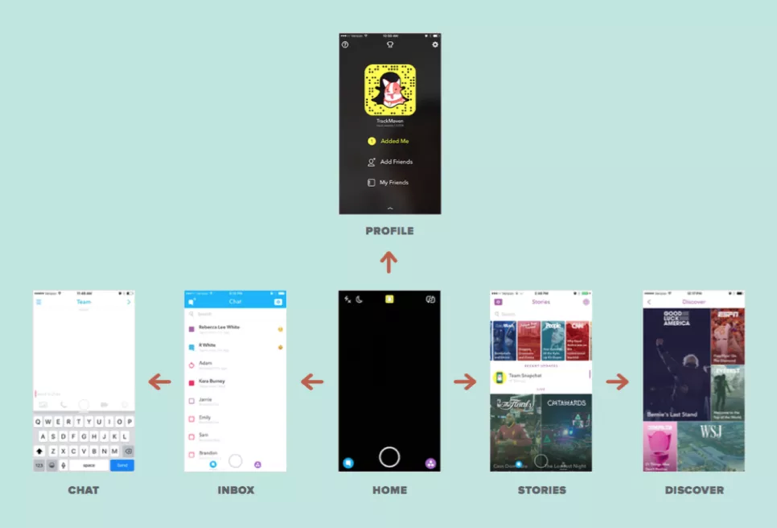

Some interfaces make wayfinding much harder than it needs to be. Many (older?) people find it incredibly difficult to navigate around Snapchat, for example. Perhaps you are one of them! In many cases, there is no button or link to get you from one place to the other, so you just have to know where to click or swipe to get places. It is full of hidden “Easter eggs” that most people (Gen Y and Z excepted) don’t know how to find.

Figure 4.3: Snapchat Navigation

When Snapchat was updated in 2017, there was a mass revolt from the teens who loved it. Why? Because their existing wayfinding expectations no longer applied. As I write this book, Snapchat is working hard to unwind those changes to conform better to existing expectations. Take note of that lesson as you design and redesign your products and services: matched expectations can make for a great experience (and violated expectations can destroy an experience).

The more we can connect our virtual world to some equivalency of the physical world, the better our virtual world will be. We’re starting to get there, with augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR), or even cues like edges of tiles that protrude from the edge of an interface (like Pinterest’s) to suggest a horizontally scrollable area. But there is so many more opportunities to improve today’s interfaces! Even something as basic as virtual breadcrumbs or cues (e.g., a slightly different background color for each section of a news site) could serve us well as navigational hints (that goes for you too Westfield Montgomery Mall).

Figure 4.4: Visual Perspective

One of the navigational cues we cognitive scientists believe product designers vastly underuse is our sense of 3-D space. While you may never need to “walk” through a virtual space, there may be interesting ways to use 3-D spatial cues, like in the scene above. This scene provides perspective through the change in size of the cars and the width of the sidewalk as it extends back. This is an automatic cognitive processing system that we (as designers and humans) essentially “get for free.” Everyone has it. Further, this part of the “fast” system works automatically without taxing conscious mental processes. A myriad of interesting and as-of-yet untapped possibilities abound!

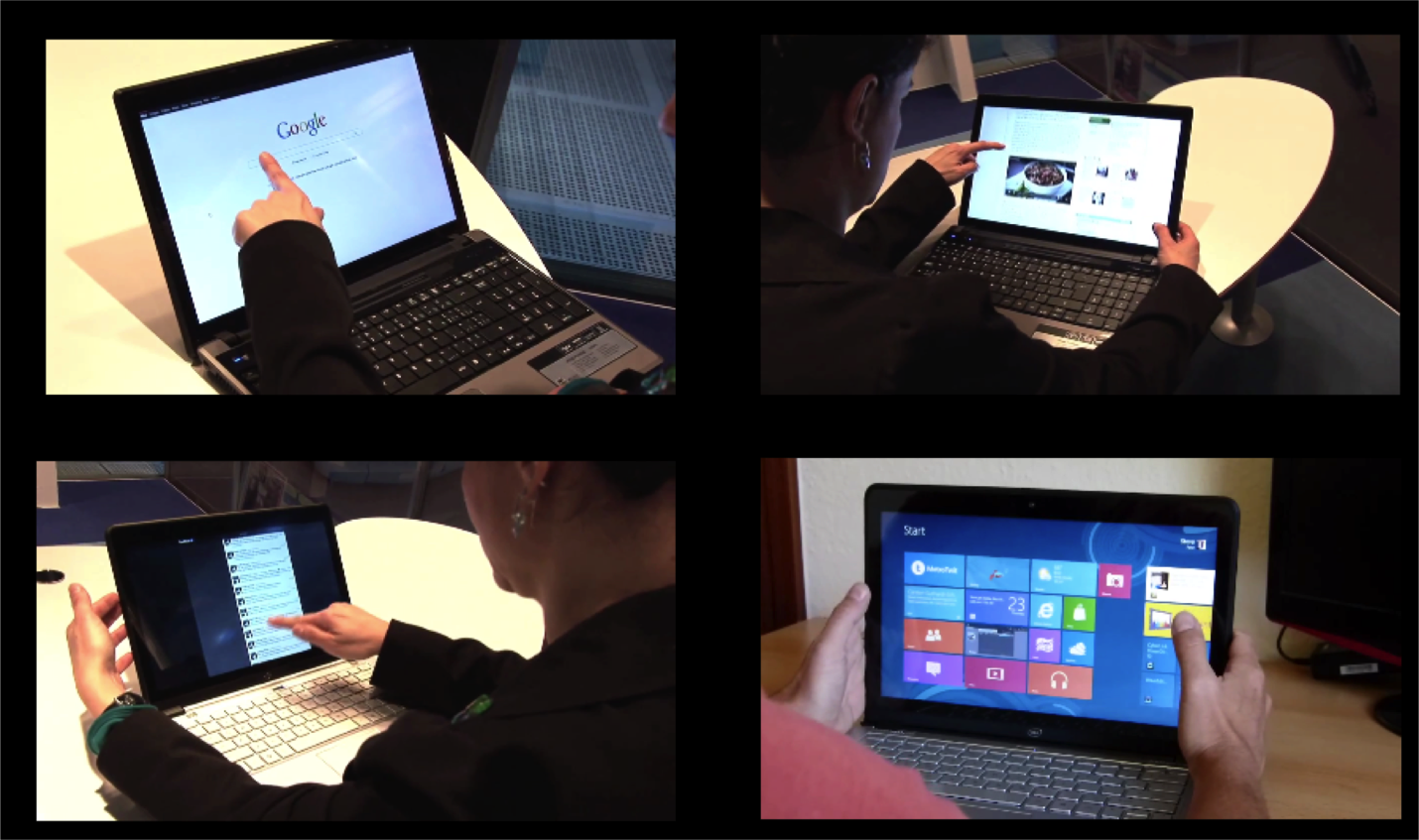

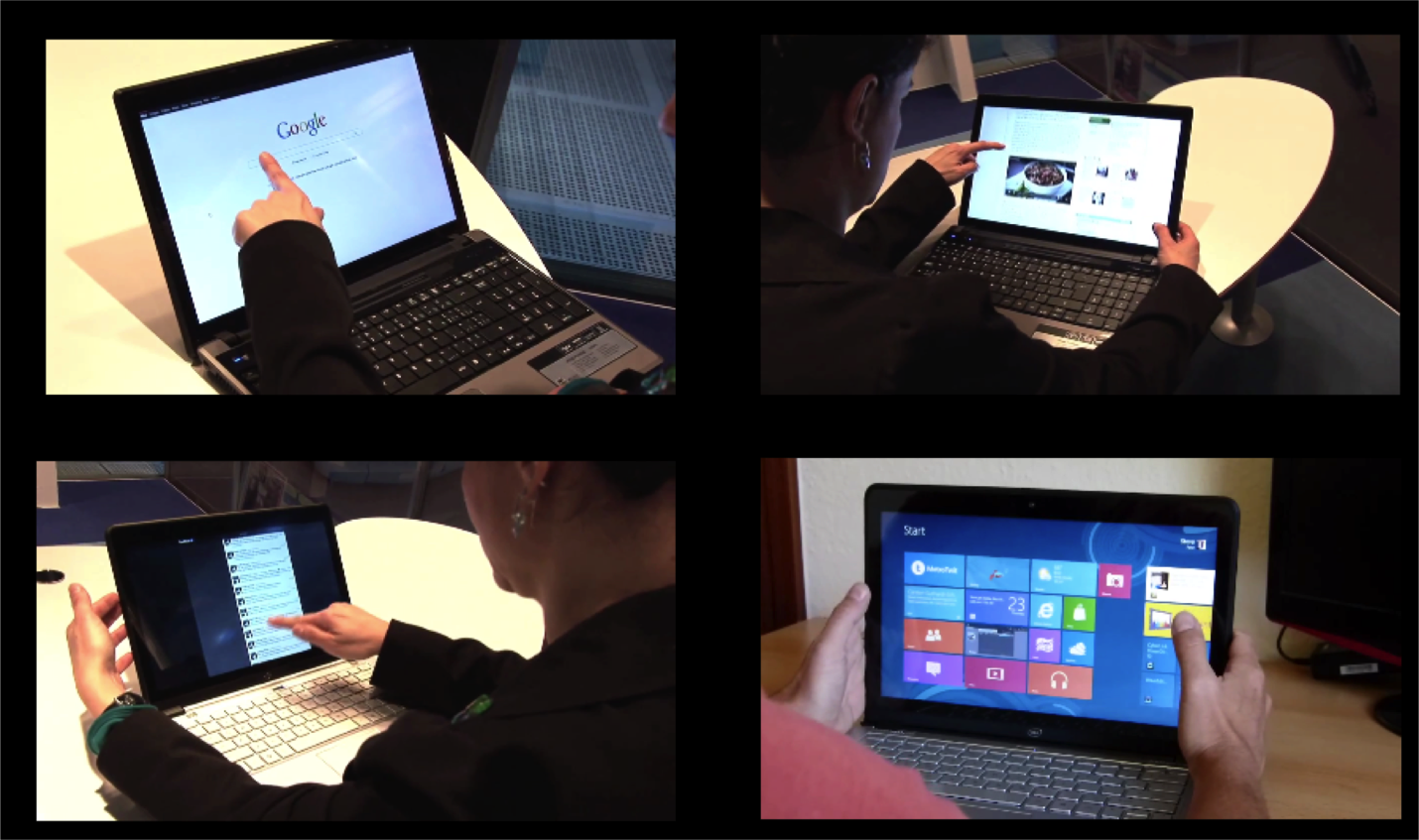

Testing interfaces to reveal metaphors for interaction

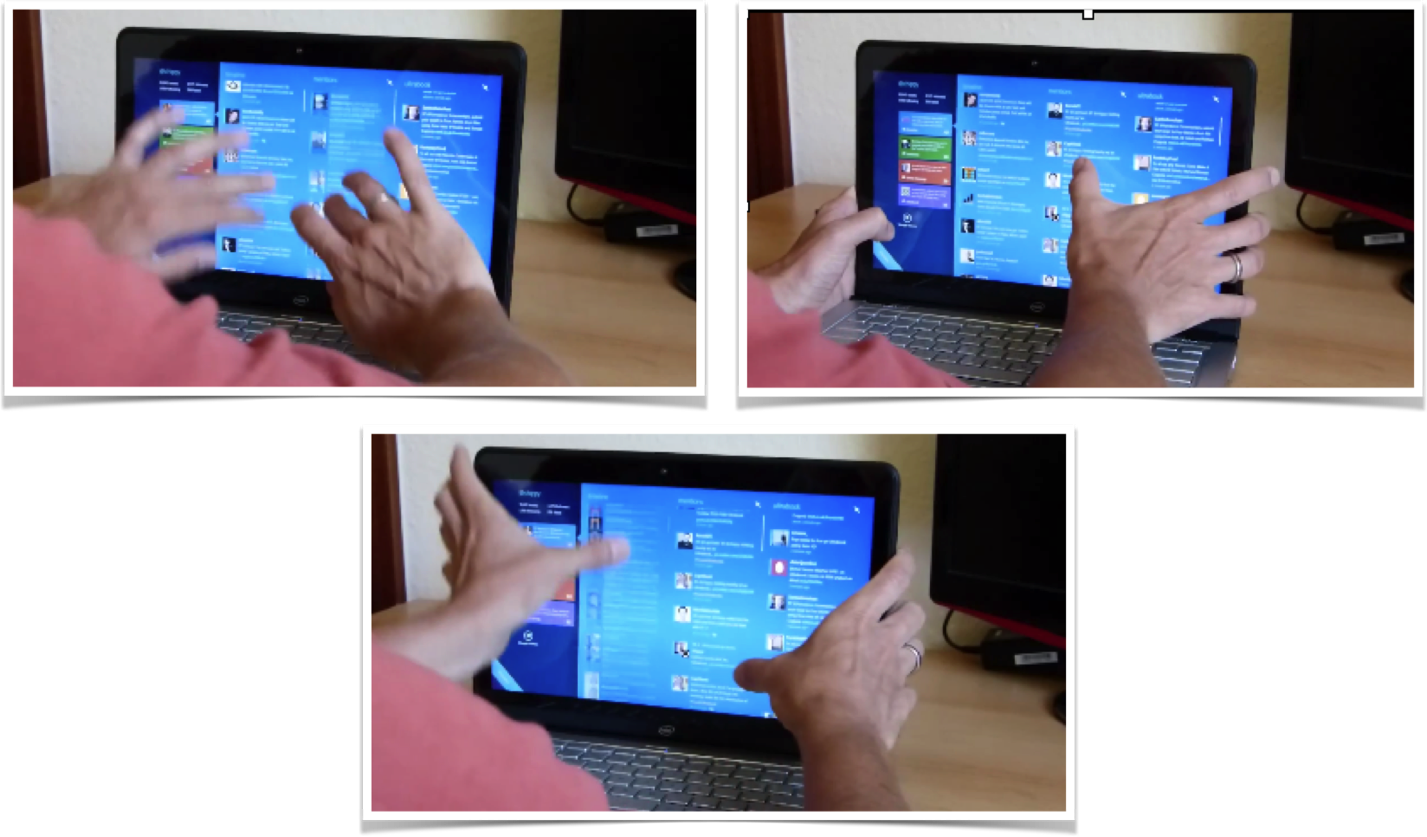

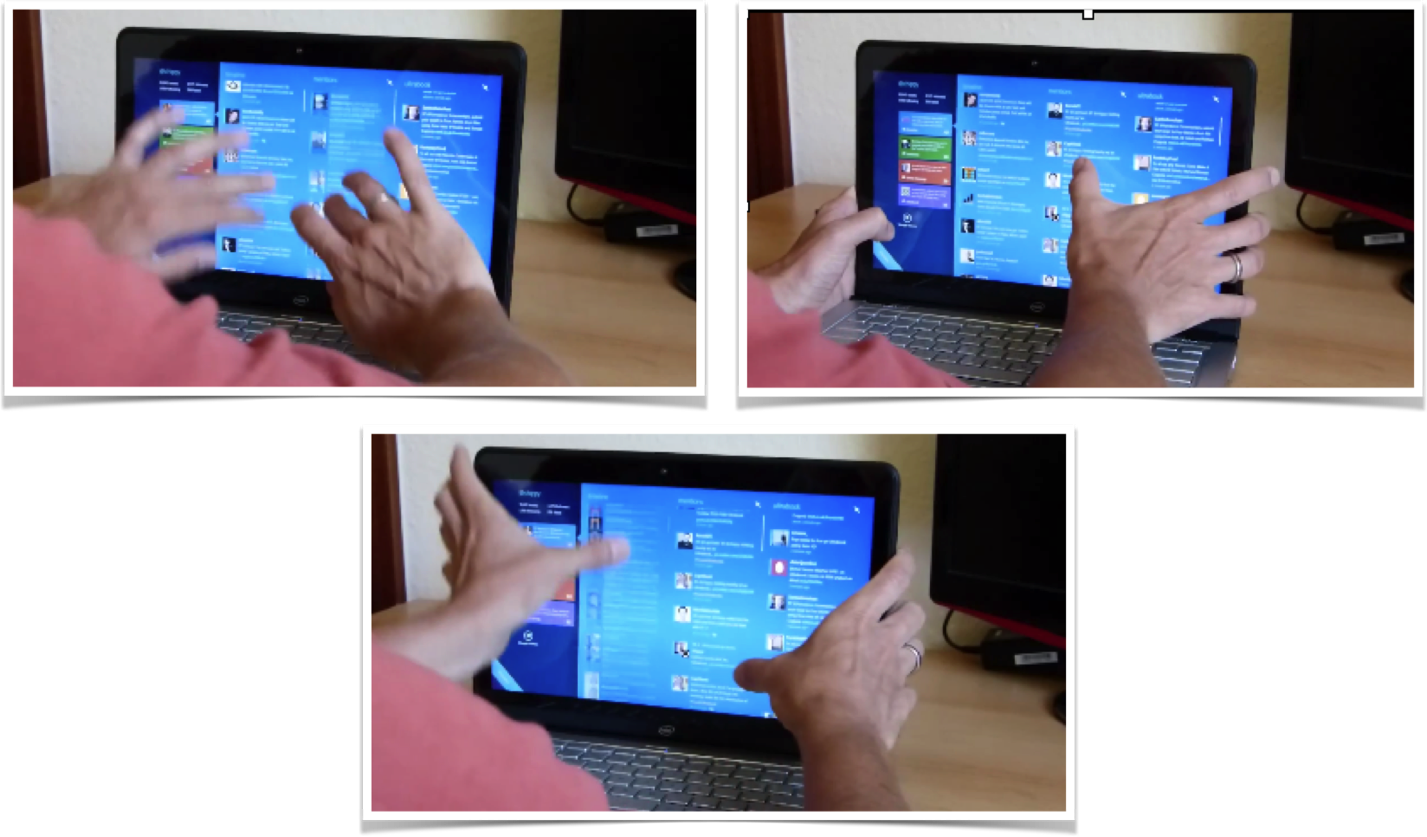

One thing that we do know today is that it is crucial to test interfaces to see if the metaphors we have created (for where customers are and how customers interact with a product) are clear. One of the early studies done using touchscreen laptops demonstrated the value of testing to learn how users think they can move around in the virtual space of an app or site. When for the first time ever they were attempting to use touchscreen laptops, the users instinctively used metaphors from the physical world. Participants touched what they wanted to select (upper right frame), dragged a web page up or down like it was a physical scroll (lower left frame), and touched the screen in the location where they wanted to type something (upper left frame).

Figure 4.5: First reactions to touchscreen laptop

However, in addition to simply doing what might be expected, as in every user test I’ve ever conducted, it also uncovered things that were completely unexpected — particularly, how people attempted to interact with the laptop.

Figure 4.6: Using touchscreen laptop with two thumbs

One user used both thumbs on the monitor while resting his hands on the sides of the monitor. He used his thumbs to attempt to slide the interface up and down using both thumbs on either side of the screen. Who knew?!

The touchscreen test demonstrated:

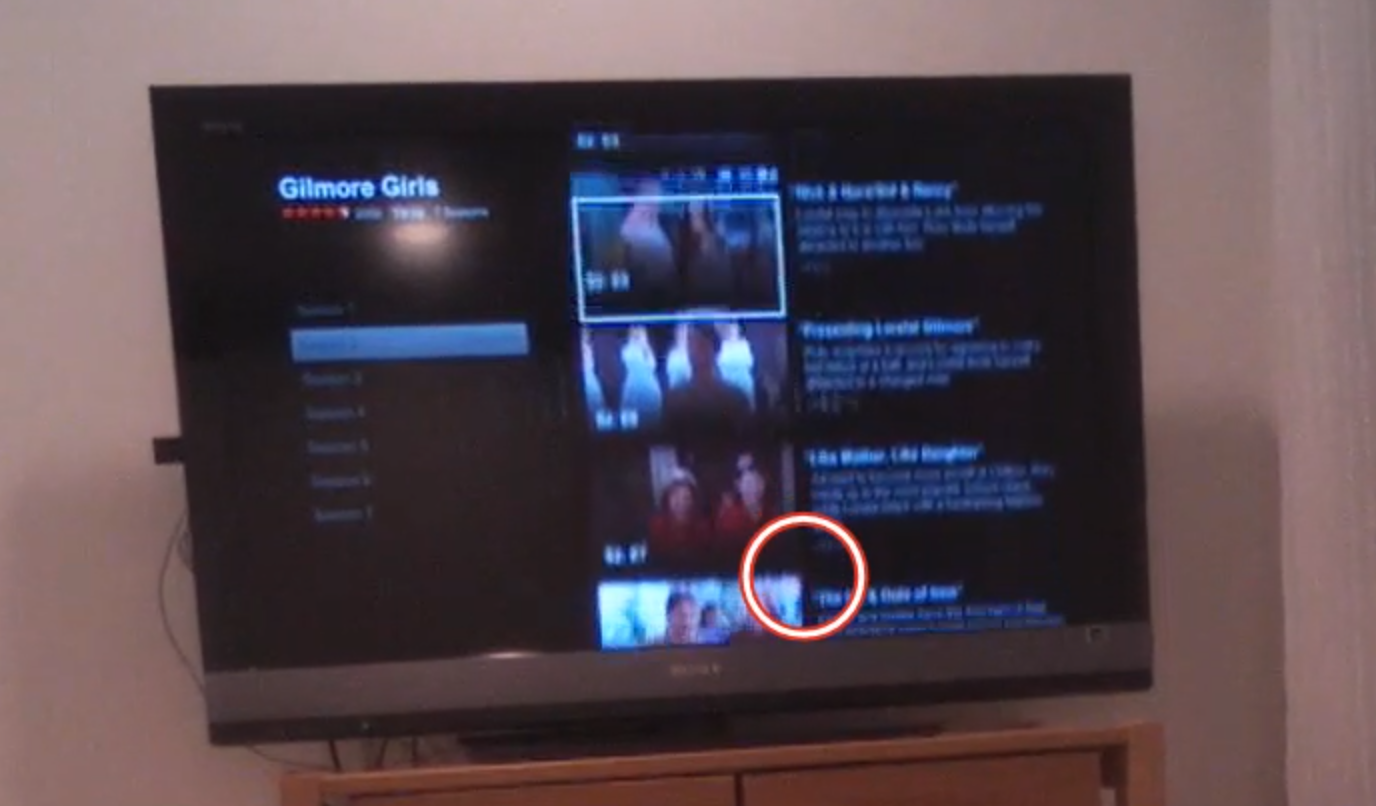

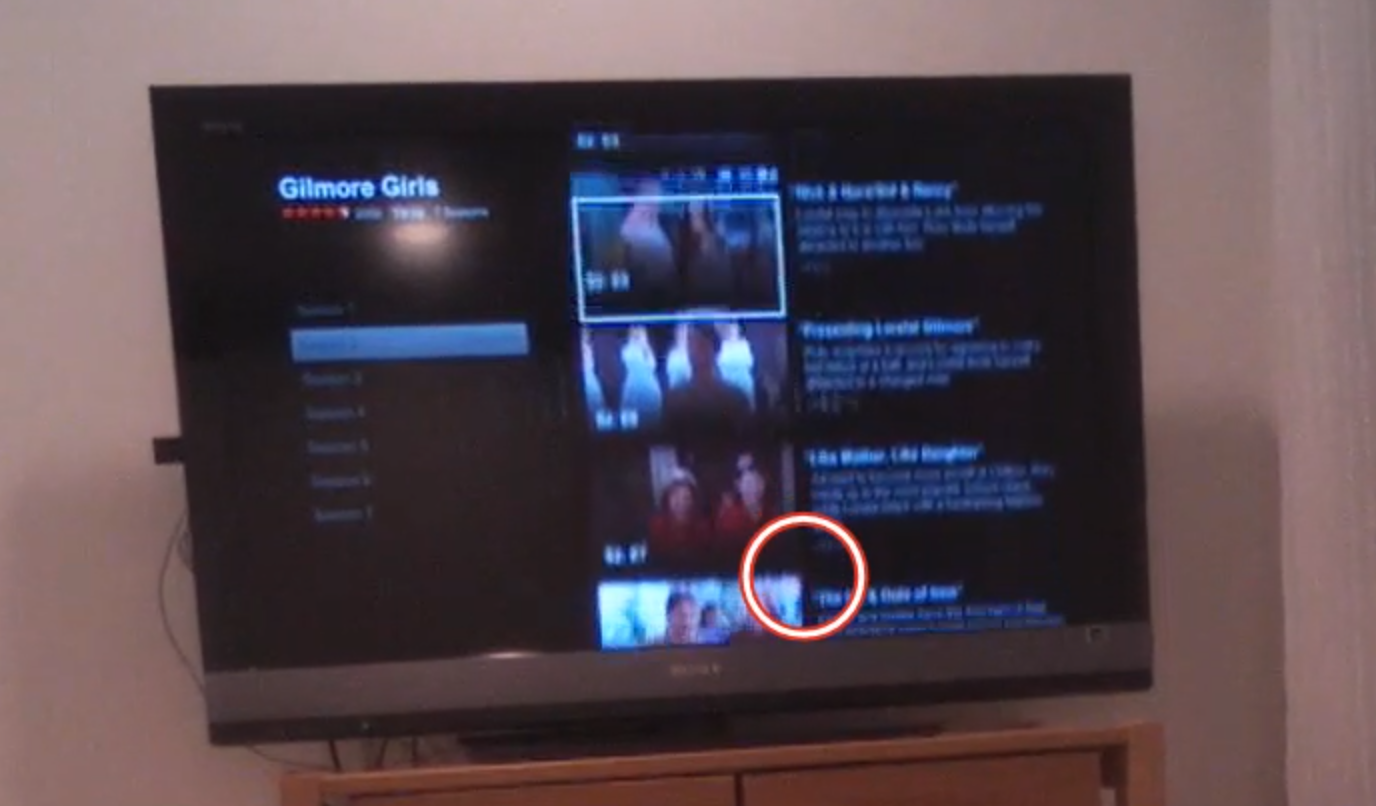

Figure 4.7: Eye-tracking TV screen interface

While observing users interact with relatively “flat” (i.e., lacking 3-D cues) on-screen television app like Netflix or Amazon Fire, we’ve learned not only about how they try to navigate the virtual menu options, but also what their expectations are for that space.

In the real world, there is no delay when you move something. Naturally then, when users select something in virtual space, they expect the system to respond instantaneously. If (as in the case above) nothing happens a few seconds after you “click” something, your are puzzled, and instinctively you focus on that oddity, thus taking away from the intended experience. Only after receiving some sort of acknowledgement from the system (e.g., screen update) will your brain relax and know the system “heard” your request.

Response times are extremely important cues that help users navigate new virtual interfaces, where they are even less tolerant of delays than they are with web pages. Often, flat displays and other similar interfaces show no evidence of feedback — neither a cue that a selection was made, nor anything to suggest the interface is working on the resultant action. Knowing the users’ metaphor and expectations will provide an indication of what sorts of interface responses are needed.

Thinking to the future: Is there a “where” in a voice interface?

There is great potential for voice-activated interfaces like Google Home, Amazon Echo, Hound, Apple Siri, Microsoft Cortana, and more. In our testing of these voice interfaces, we’ve found new users often demonstrate anxiety around these devices because they lack any physical cues that the device is listening or hearing them, and the system timing is far from perfect.

In testing both business and personal uses for these tools in a series of head-to-head comparisons, we’ve found there are a few major challenges that lie ahead for voice interfaces. First, unlike the real world or screen-based interfaces, there are no cues about where you are in the system. If you start to discuss the weather in Paris, while the human still is thinking about Paris, it is never clear if the voice system’s frame of reference is still Paris. After asking about the weather in Paris, you might ask a follow-up question like “How long does it take to get from there to Monaco?” Today, with only a few exceptions, these systems start fresh in every discussion and rarely follow a conversational thread (e.g., that we are still talking about Paris).

Second, if the system does jump to a specific topical or app “area” (e.g., Spotify functionality within Alexa), unlike physical space, there are no cues that you are in that “area,” nor are there any cues as to what you can do or how you can interact. I can’t help but think that experts in accessibility and sound-based interfaces will save the day and help us to improve today’s impressive — but still suboptimal — voice interfaces.

As product and service designers, we’re here to solve problems, not come up with new puzzles for our users. We should strive to match our audience’s perception of space (whatever that may be) and align our offerings to the ways our users already move around and interact. To help our users get from virtual place to place, we need to figure out how to harness the brain’s huge parietal lobes.

Abstracting away the detail

It may not feel like it, but as we take in a scene or a conversation, we are continuously dropping a majority of the concrete physical representation of the scene, leaving us with a very abstract and concept-based representation of what we were focusing on. But perhaps you feel like you are much more of a “visual thinker” and really do get all the details. Great! Please tell me which of the below is the real U.S. penny:

Figure 5.1: Which is the real U.S. penny?

If you are American, you may have seen a thousand examples of these in your lifetime. So surely this isn’t hard for a visual thinker! (You can find the answers to these riddles at the end of the chapter.)

Okay maybe that last test might be considered unfair for you if you rarely have paper currency, let alone metal change. Well then, let’s consider a letter you’ve seen millions of times: The letter “G”. Which of the following is the correct orientation of the letter “G” in lower case?

Figure 5.2: Which is the real “G”?

Not so easy, right? In most cases, when we look at something, we feel like we have a camera snapshot in our mind. But in less than a second, your mind loses the physical details and reverts to a pre-stored stereotype of it — and all the assumptions that go along with it.

Remember, not all stereotypes are negative. The actual Merriam-Webster definition is “something conforming to a fixed or general pattern.” We have stereotypes for almost anything: a telephone, coffee cup, bird, tree, etc.

Figure 5.3: Stereotypes of phone

When we think of these things, our memory summons up certain key characteristics. These concepts are constantly evolving (e.g., from wired telephone to mobile phone). Only the older generations might pick the one on the left as a “phone.”

It terms of cognitive economy, it makes logical sense that we wouldn’t store every perspective, color, and light/shadow angle of every phone we have ever seen. Rather, we quickly move to the concept of a phone and use that representation (e.g., modern iPhone) and fill in the gaps in memory for a specific instance with the concept of that object.

Design Tip: As product designers, we can use this quirk of human cognition to our benefit. By activating an abstract concept that is already in someone’s head (e.g., the steps required to buy something online), we can efficiently manage expectations, be consistent with expectations, and make the person more trusting of the experience.

Trash Talk

Let me provide you with an experiment to show just how abstract our memory can be. First, get out a piece of paper and pencil and draw an empty square on the piece of paper. After reading this paragraph, go to the next page and look at the image for 20 seconds (don’t pick up your pencil yet, though). After 20 seconds are up, I want you to scroll back or hide your screen so that you can’t look at the image. Only then, I want you to pick up your pencil and draw everything that you saw. It doesn’t have to be Rembrandt (or an abstract Picasso), just a quick big-picture depiction of the objects you saw and where they were in the scene. Just a sketch is fine — and you can have 2 minutes for that.

Figure 5.4: Draw your image here

Okay, go! Remember, 20 seconds to look (no drawing), then 2 minutes to sketch (no peeking).

FIgure 5.55.: Picture of an alleyway

Since I can’t see your drawing (though I’m sure it’s quite beautiful), I’ll need you to grade yourself. Look back at the image and compare it to your sketch. Did you capture everything? Two trash cans, one trash can lid, a crumpled-up piece of trash, and the fence?

Now, going one step further, did you capture the fact that one of the trash cans and the fence are both cut off at the top? Or that you can’t see the bottom of the trash cans or lid? When many people see this image, or images like it, they unconsciously “zoom out” and complete the objects according to their stored representations of similar objects. In this example, they tend to extend the fence so its edges go into a point, make the lid into a complete circle, and sketch the unseen edges of the two garbage cans. All of this makes perfect sense if you are using the stereotypes and assumptions we have about trash cans, but it isn’t consistent with what we actually saw in this particular image.

Figure 5.6: Examples of Boundary Extension (Weintraub, 1997)

Technically, we don’t know what’s actually beyond the rectangular frame of this image. We don’t know for sure that the trash can lid extends beyond what we can see, or that the fence top ends just beyond what we can see in this image. There could be a whole bunch of statues of David sitting on top of the fence, for all we know.

Figure 5.7: Did you draw these statues above the tops of the fence posts?

https://flic.kr/p/4t29M3

Our natural tendency to mentally complete the image is called “boundary extension.” Our visual system prepares for the rest of the image as if we’re looking through a cardboard tube, or a narrow doorway. Boundary extension is just one example of how our minds move quickly from very concrete representations of things to representations that are much more abstract and conceptual.

The main implication for product managers and designers is this: A lot of what we do and how we act is based on unseen expectations, stereotypes, and anticipations, rather than what we’re actually seeing when light hits the back of our retinas. We as product and service designers need to discover what those hidden anticipations and stereotypes might be (as we’ll discuss in Part II of the book).

Stereotypes of services

Human memory, as we’ve been discussing, is much more abstract than we generally think it is. When remembering something, we often forget many perceptual details and rely on what we have stored in our semantic memory. The same is true of events. How many times have you heard a parent talk about the time that one of their kids misbehaved many years ago, and incorrectly blamed it on “the child that was always getting into trouble”, rather than the “good one” (I was fortunate enough to be in the latter camp and got away with all kinds of things according to my Mom’s memory, thanks to stereotypes).

The trash can drawing above was a very visual example of stereotypes, but it need not be all about visual perception. We have stereotypes about how things might work, and how we might interact in a certain situation. Here’s an example that has to do more with language, interactions, and events.

Imagine inviting a colleague to a celebratory happy hour. In her mind, “happy hour” may mean swanky decorations, modern bar stools, drinks with fancy ice cube blocks, and sophisticated “mixologists” with impeccable clothing. Happy hour in your mind, on the other hand, might mean sticky floors, $2 beers on tap, and the same grumpy guy named “Buddy” in the same old t-shirt asking “Whatcha want?”

Figures 5.8 and 5.9: What is “Happy Hour” to you?

Both of these are “happy hour,” but the underlying expectations of what’s going to happen in each of these places might be very different. Just like we did in the sketching exercise, we jump quickly from concrete representations (e.g., the words “happy hour”) to abstract inferences. We anticipate where we might sit, how we might pay, what it might smell like, what we will hear, who we will meet there, how you order drinks, and so on.

In product and service design, we need to know what words mean to our customers, and what associate they have with those words. “Happy hour” is a perfect example. When there is a dramatic difference between a customer’s expectation of a product or service and how we designed it, we are suddenly fighting an uphill battle by trying to overcome our audience’s well-practiced expectations.

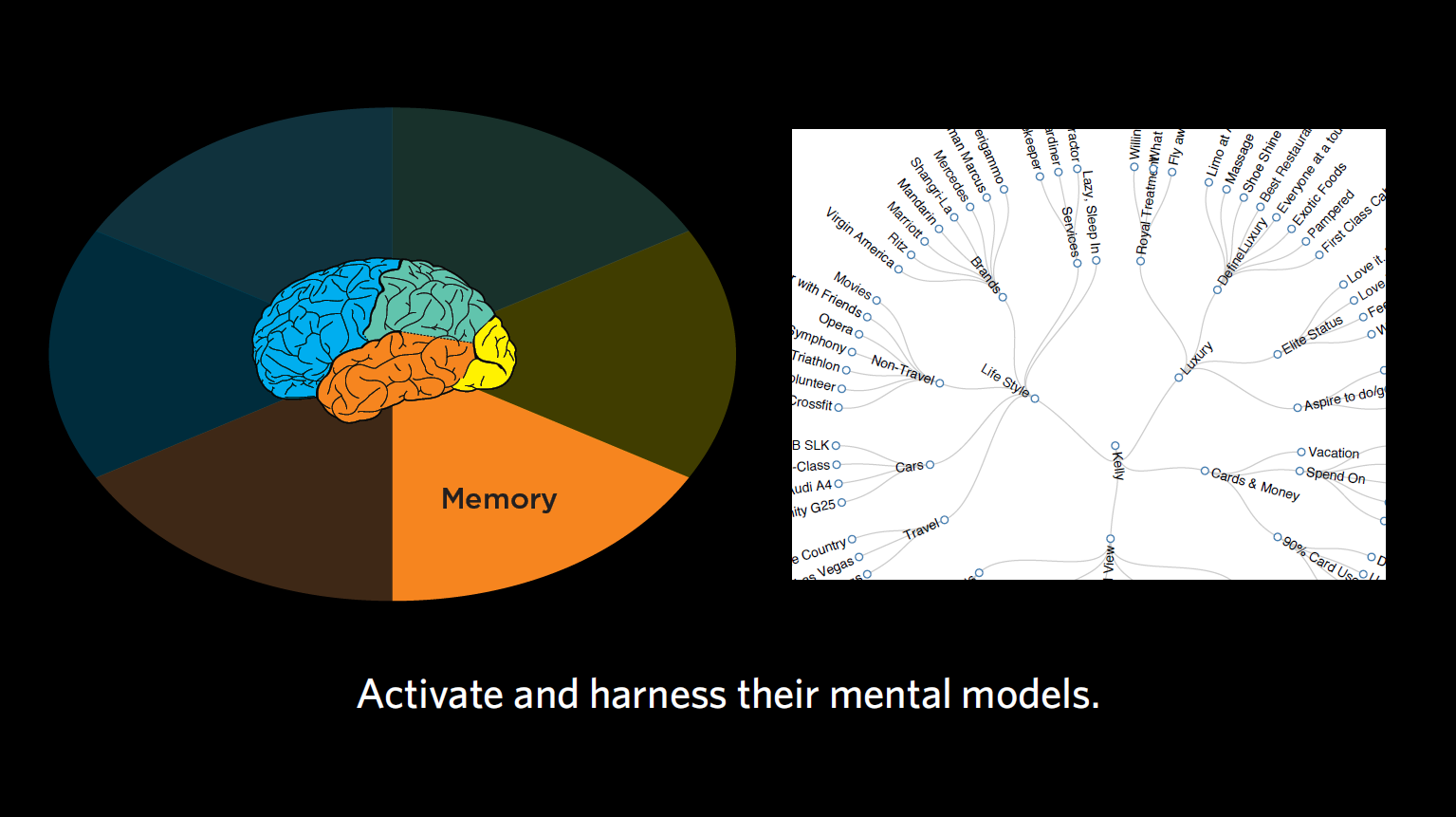

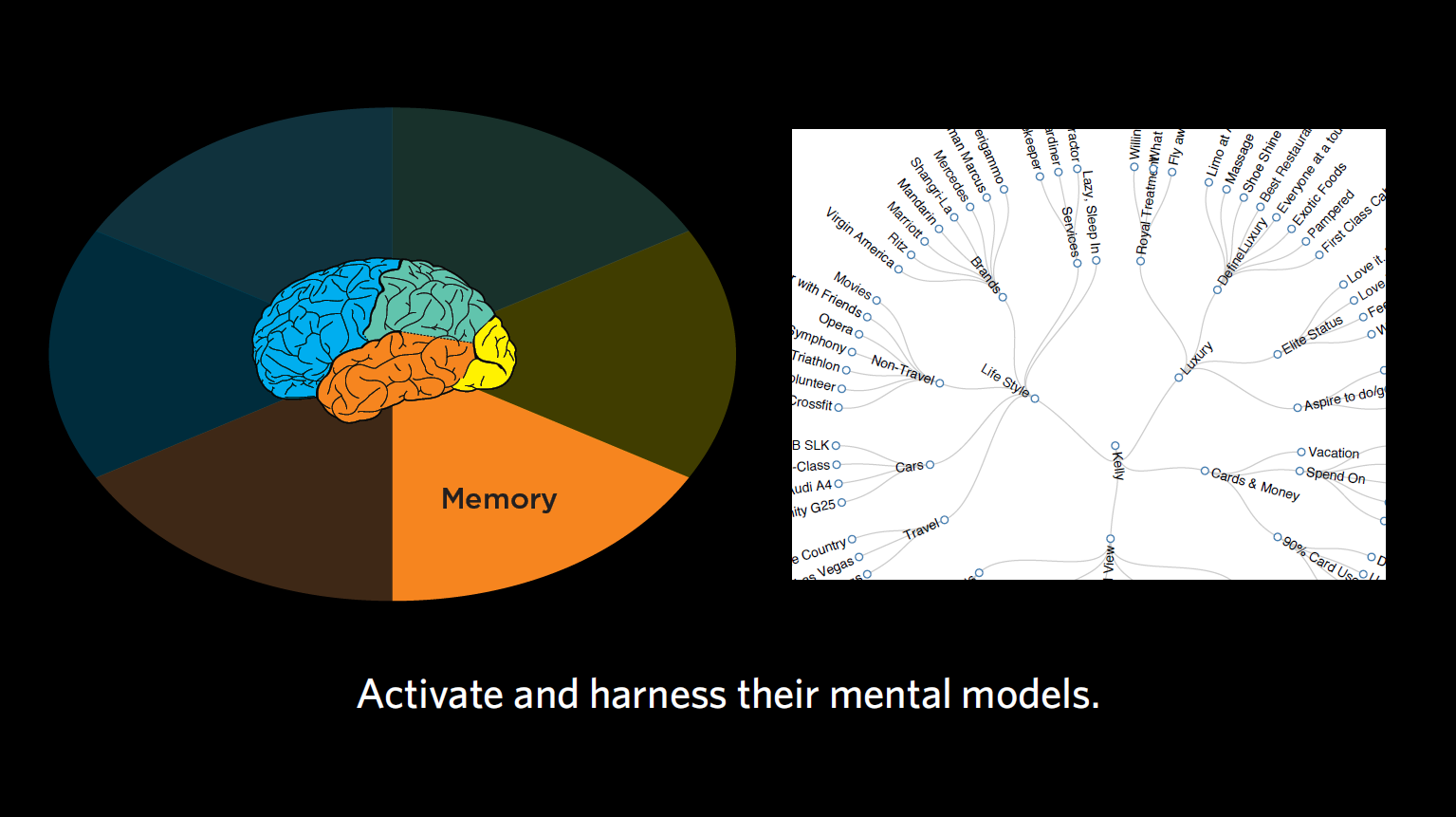

The value of understanding mental models

Knowing and activating the right mental model (i.e., “psychological representations of real, hypothetical, or imaginary situations”) can save us a huge amount of time as product or service designers. This is something we rarely hear anything about in customer experience — and yet, understanding and activating the right mental models will build trust with our target audience and reduce the need for instructions.

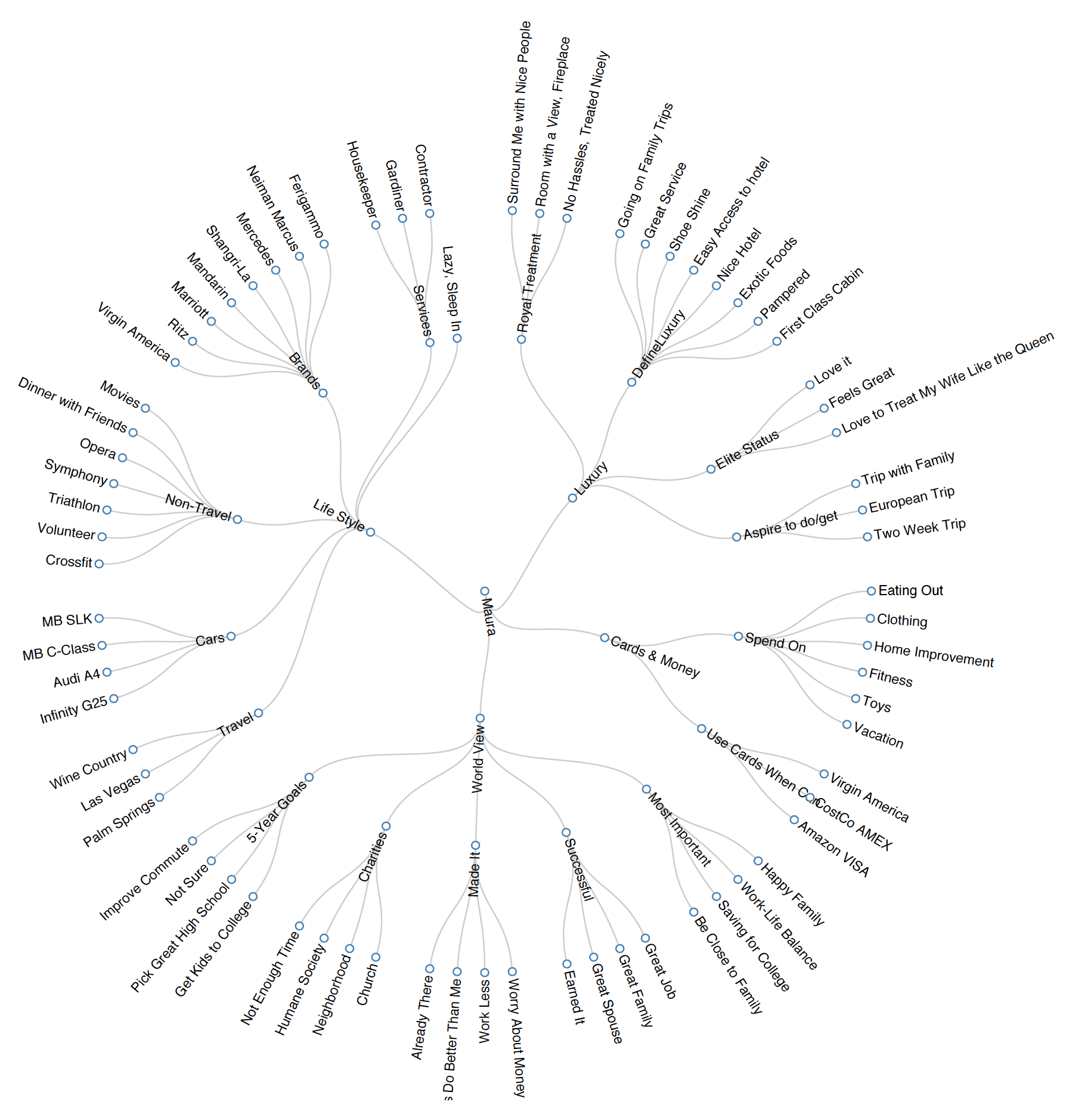

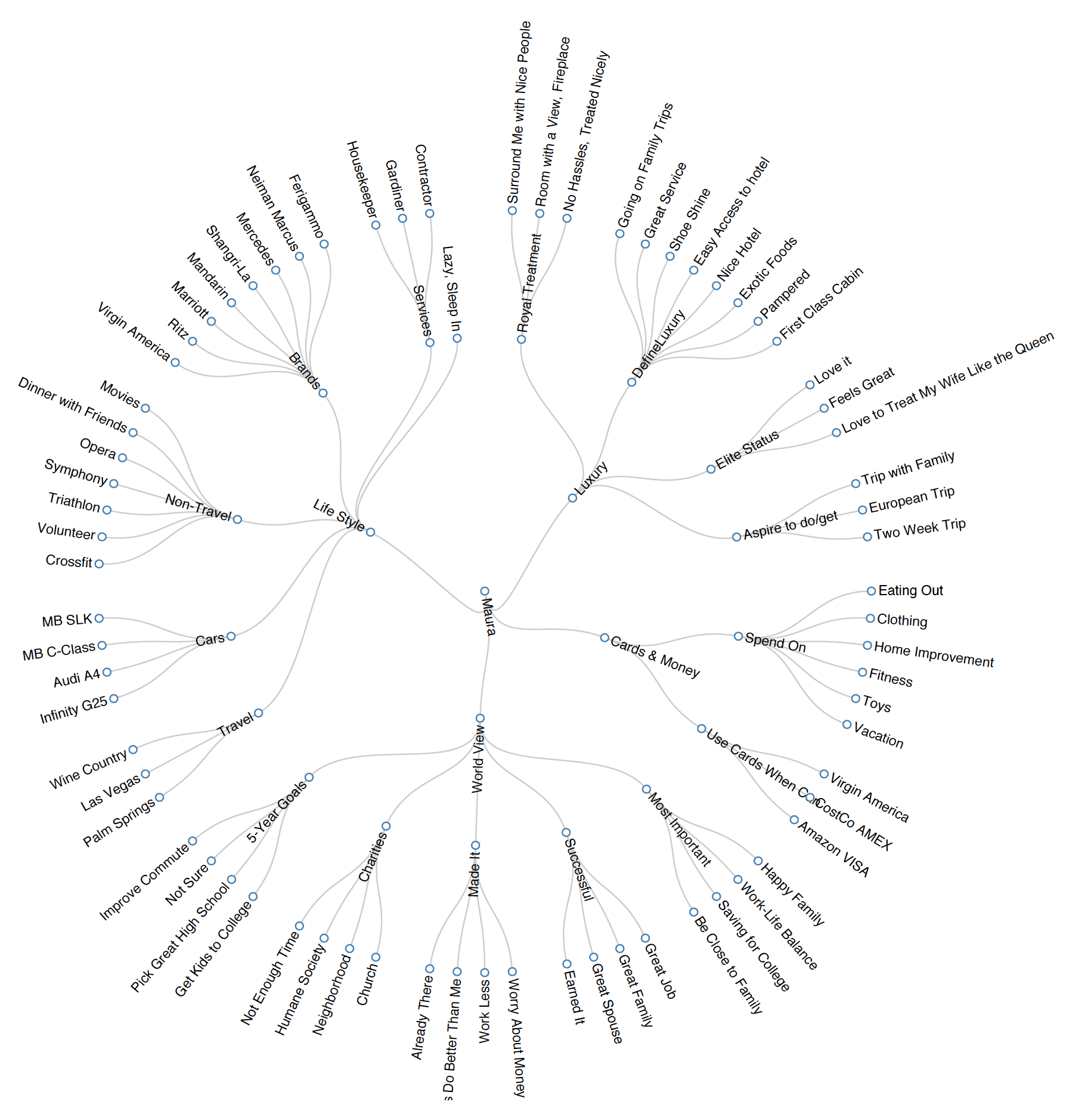

Case study: The concept “weekend”

Figure 5.10: Words used to describe a Weekend

Challenge: In one project for a financial institution, my team and I interviewed two groups of people regarding how they use, manage, and harness money to accomplish their goals in life. The two groups consisted of: 1) a set of young professionals, most of whom were unmarried, without children, and 2) a group that was a little bit older, most of whom had young children. We asked them what they did on the weekend. You can see their responses in the visualizations above.

Result: Clearly, the two groups had very different semantic associations with the concept of “weekend.” Their answers helped us glean: (A) What the phrase “the weekend” means to each of these groups, and (B) How the two groups are categorically different, including what they value and how they spend their time. Our further research found very large differences in the concept of luxury for each group. In tailoring products/services to each of these groups, we would need to keep in mind their respective mental model of “weekend.” This could influence everything from the language and images we use to the emotions we try to evoke.

Acknowledging the diversity of types of mental models

Thus far, we’ve discussed how our minds go very quickly from specific visual details or words to abstract concepts, and the representations that are generated by those visual features or words can be distinct across audiences. But also recognize there are many other types of stereotypical patterns. In addition to these perceptual or semantic patterns, there are also stereotypical eye patterns and motor movements.

You probably remember being handed someone’s phone or a remote control you’ve never used before and saying to yourself something like: “Ugh! Where do I begin? Why is this thing not working? How do I get it to…? I can’t find the…?”. That experience is the collision between your stereotypical eye and motor movements, and the need to override them.

The point I’m driving home here is that there are a wide range of customer expectations baked into interactions with products and services. Our experiences form the basis for mental assumptions about people, places, words, interaction designs … pretty much everything. This makes sense because under normal circumstances, stored and automated patterns are incredibly more mentally efficient and allow your mental focus to be elsewhere. As product and service managers and designers, we need to both:

Riddle Answer Key!

Chapter 6. Language: I Told You So

In Voltaire’s words, “Language is very difficult to put into words.” But I’m going to try to anyway.

In this chapter, we’re going to discuss what words our audiences are using, and why it’s so important for us to understand what they tell us about how we should design our products and services.

Wait, didn’t we just cover this?

In the previous chapter, we discussed our mental representations of meaning. We have linguistic references for these concepts as well. Often, as non-linguists, it is easy to think of a concept and the linguistic references to that concept as one and the same. But they’re not. Words are actually strings of morphemes/phonemes/letters that are associated with semantic concepts. Semantics are the abstract concepts that are associated with the words. In English, there is no relationship between the sounds or characters and a concept without the complete set of elements. For example, “rain” and “rail” share three letters, but that doesn’t mean their associated meanings are nearly identical. Rather, there are essentially random associations between a group of elements and their underlying meanings.

What’s more, these associations can differ from person to person. This chapter focuses on how different subsets of your target audiences (e.g., non-experts and experts) can use very different words, or use the same word – but attach different meanings to it. This is why it’s so important to carefully study word use to inform product and service design.

Figure 6.1: Semantic Map

The language of the mind

As humans and product designers, we assume that the words we utter have the same meanings for other people as they do for us. Although that might make our lives, relationships, and designs much easier, it’s simply not true. Just like the abstract memories that we looked at in the previous chapter, word-concept associations are more unique across individuals and especially across groups than we might realize. We might all do better in understanding each other by focusing on what makes each of us unique and special.

Because most consumers don’t realize this, and have the assumption that “words are words” and mean what they believe them to mean, they are sometimes very shocked (and trust products less) when those products or services use unexpected words or unexpected meanings for words. This can include anything from cultural references (“BAE”) to informality in tone (“dude!”) to technical jargon (“apraxic dysphasia”).

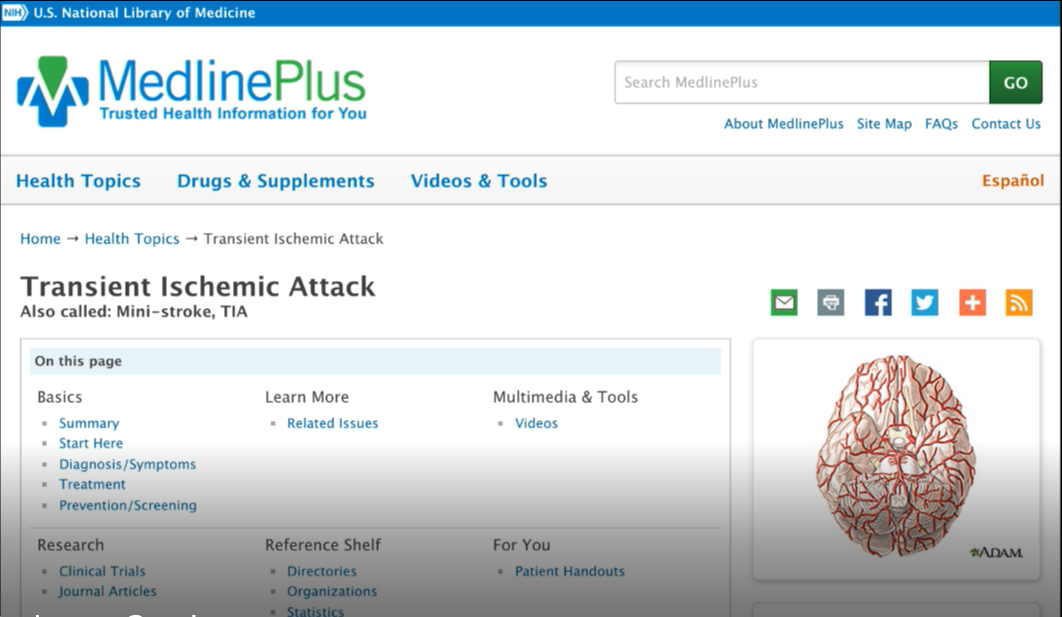

If I told you to “use your noggin,” for example, you may try to concentrate harder on something — or you may be offended that I didn’t tell you to use your dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. If you’re a fellow cognitive scientist, you might find the informality I started with insultingly imprecise. If you’re not, and I told you to use your dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, you might find my language confusing (“Is that even English?”), meaningless, and likely scary (“Can I catch that in a public space?”). Either way, I run the risk of losing your trust by deviating from your expected style of prose.

|

Ordinary American’s terms |

Cognitive neuropsychologist’s terms |

|

Stroke, brain freeze, brain area near the middle of your forehead |

Cerebral vascular accident (CVA), transient ischemic attack (TIA), anterior cingulate gyrus |

The same challenge applies to texting. Have you ever received a text reading “SMH” or “ROTFL” and wondered what it meant? Or perhaps you were the one sending it, and received a confused response from an older adult. Differences in culture, age, and geographic location are just a few of the factors that influence the meanings of words in our minds, or even the existence of that entry in our mental dictionaries — our mental “lexicon.”

|

Adult terms |

Teen texter’s terms |

|

I’ll be right back, that’s really funny, for what it’s worth, in my opinion |

BRB, ROTFL, FWIW, IMHO |

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate”

When we think about B2C communication fails, it’s often language that gets in between the business and the customer, causing customers to lose faith in the company and end the relationship. Have you ever seen an incomprehensible error message on your laptop? Or been frustrated with an online registration form that asks you to provide things you’ve never even heard of (e.g., Actual health care enrollment question: What is your FBGL, in mg/dl)?

This failure to communicate usually stems from a business-centric perspective, resulting in overly technical language or sometimes, an over-enthusiastic branding strategy that results in the company being too cryptic with their customers (e.g., What is the difference between a “venti” and a “tall”?). To reach our customer, it’s crucial that we understand the customer’s level of sophistication of your line of work (as opposed to your intimate in-house knowledge of it), and that we provide products that are meaningful to them at their level.

(Case in point: Did you catch my “Cool Hand Luke” reference earlier? You may or may not have, depending on your level of expertise when it comes to Paul Newman movies from the 60s, or your age, or your upbringing. If I were trying to reach Millennials in a clever marketing campaign, I probably wouldn’t quote from that movie; instead, I might choose something from “The Matrix.”)

Revealing words

The words that people use when describing something can reveal their level of expertise. If I’m talking with an insurance agent, for example, she may ask whether I have a PLUP. For that agent, it’s a perfectly normal word, even though I may have no idea what a PLUP is (in case you don’t, either, it’s short for a Personal Liability Umbrella Policy, which provides coverage for any liability issue). Upon first hearing what the acronym stood for, I thought it might protect you from rain and flooding!

|

Ordinary American’s terms |

Insurance broker’s terms |

|

Home insurance, car insurance, liability insurance |

Annualization, Ceded Reinsurance Leverage, Personal Liability Umbrella Policy (PLUP), Development to Policyholder Surplus |

Over time, people like this insurance agent build up expertise and familiarity with the jargon of their field. The language they use suggests their level of expertise. To reach them (or any other potential customer), we need to understand both:

As product owners and designers, we want to make sure we’re using words that resonate with our audience — words that are neither over nor beneath their level of expertise. If we are communicating with a group of orthopedic specialists, we would use very different language than if we were trying to communicate to young preschool patients. If we tried to use the specialists’ complicated language when speaking to patients, instead of layman’s terms, we’d run the risk of confusing and intimidating our audience, and probably losing their trust as well.

Perhaps this is why cancer.gov provides two definitions of each type of cancer; the health professional version and the patient version. You’ve heard people say “you’re speaking my language.” Just like cancer.gov, we want your customers to experience this same comfort level when they come across your products or services — whether as an expert or novice. It’s a comfort level that comes from a common understanding and leads to a trusting relationship.

|

How many of these Canadian terms do you understand? |

|

chesterfield, kerfuffle, deke, pogie, toonie, soaker, toboggan, keener, toque, eavestroughs |

When your products and services have a global reach, there is also the question of the accuracy of translation, and the identification and use of localized terms (e.g., trunk (U.S.) = boot (U.K.)). We must ensure that the words that are used in the new location mean what we want them to mean when they’re translated into the new language or dialect. I remember a Tide detergent ad from several years ago saying things like “Here’s how to clean a stain from the garage (e.g., oil), or a workshop stain, or lawn stain.” While the translations were reasonably accurate, the intent went awry. Why? When they translated this American ad for Indian and Pakistani populations, they forgot to realize that most people had a “flat” (apartment) and didn’t have a garage, workshop, or lawn. Their conceptual structure was all different!

I’m listening

Remember in the last chapter, how I used the example of my team using interviews with young professionals and parents of young children to uncover underlying semantic representations among our audience? I can’t overstate the importance of interviews, and transcripts of those interviews, in researching your audience. We want to know the exact terms they use (not just our interpretation of what they said) when we ask a question like, “What do you think’s going to happen when you buy a car?” Examining transcripts will often reveal the lexicon your customers use is likely very different than your own (as a car salesperson).

Through listening to their exact words, we can learn what words they’re commonly using, the level of expertise their words imply, and ultimately, what sort of process this audience is expecting. This helps experience designers either conform more closely to customers’ anticipated experience or warn their customers that the process may differ from what they might expect.

Overall, here’s our key takeaway. It’s pretty simple, or at least it sounds simple enough. Once we have an understanding of our users’ level of understanding, we can create products and services that have the sophistication and terminology that works best for our customers. This leads to a common understanding of what is being discussed and trust — ultimately leading to happy, loyal customers.

Chapter 7. Decision-Making and Problem Solving: Enter Consciousness Stage Left

Up until now, most of the processes I’ve introduced so far, like attentional shifts and representing 3-D space, occur automatically, even if influenced by consciousness. In contrast, this chapter focuses on the very deliberate and conscious process of decision-making and problem-solving. Relative to other processes, this is one that you’re the most aware of and in control of. Right now I’m pretty sure that you’re thinking about the fact that you’re thinking about it.

We will focus on how we, as decision-makers, define where we are now and our goal state, and make make decisions to get us closer to our desired goal. Designers rarely think in these terms but I hope to change that.

What is my problem (definition)?

When you’re problem solving and decision making, you have to answer a series of questions. The first one is “What is my problem?” I don’t mean that you’re beating yourself up — I mean what is the problem you’re trying to solve: where are you now (current state) and where do you want to be (goal state).

Figure 7.1 People searching for clues in an escape room.

If you’ve ever experienced an Escape Room, an adventure game where you have to solve a series of riddles as quickly as possible to get out of a room. While getting unlocking the door may be your ultimate goal, there are sub-goals you’ll need to accomplish before that (e.g., finding the key) in order to get to your end goal. Sub-goals like finding a lost necklace, which you’ll need for your next sub-goal of opening a locked box, for instance (I’m making these up; no spoiler alerts here!).

Chess is another example of building sub-goals within larger goals. Ultimate goal: checkmate the opponent’s king. As the game progresses, however, you’ll need to create sub-goals to help you reach your ultimate goal. Your opponent’s king is protected by his queen and a bishop, so a sub-goal (to the ultimate goal of putting the opponent’s king into checkmate) could be eliminating the bishop. To do this, you may want to use your own bishop, which then necessitates another sub-goal of moving a pawn out of the way to free up that piece. Your opponent’s moves will also trigger new sub-goals for you — such as getting your queen out of a dangerous spot, or transforming a pawn by moving it across the board. In each of these instances, sub-goals are necessary to reach our desired end goal.

How might problems be framed differently?

Remember when we talked about experts and novices in the last chapter, and the unique words each group uses? When it comes to decision-making, experts and novices are often thinking very differently, too.

Let’s consider buying a house, for example. The novice home buyer might be thinking “What amount of money do we need to offer in order to be the bid the owner will accept?” Experts, however, might be thinking several more things: Can this buyer qualify for a loan? What is their credit score? Have they had any prior issues with credit? Do the buyers have the cash needed for a down payment? Will this house pass an inspection? What are the likely repairs that will need to be made before the buyers might accept the deal? Is this owner motivated to sell? Is the title of the property free and clear of any liens or other disputes?

So while the novice home buyer might frame the problem as just one challenge (convincing the buyer to sell at a specific price), the expert is thinking about many other things as well (e.g., a “clean” title, building inspection, credit scores, seller motivations, etc.). From these different perspectives, the problem definition is very different, and the decisions they make and actions they might take will also likely be very different.

In many cases, novices (whether first-time home buyers or college applicants or AirBnB renters) don’t define the problem that they really need to solve because they don’t understand all the complexities and decisions they need to make. Their knowledge of the problem might be very simplistic relative to what really happens.

This is why the first thing we need to understand is how our customer defines the problem. Then, we have an indication of what they think they need to do to solve that problem. As product and service designers, we need to meet them there, and over time, help to redirect them to what their actual (and likely more complex) problem is and the decisions they have to make along the way. This is known as redefining the problem space.

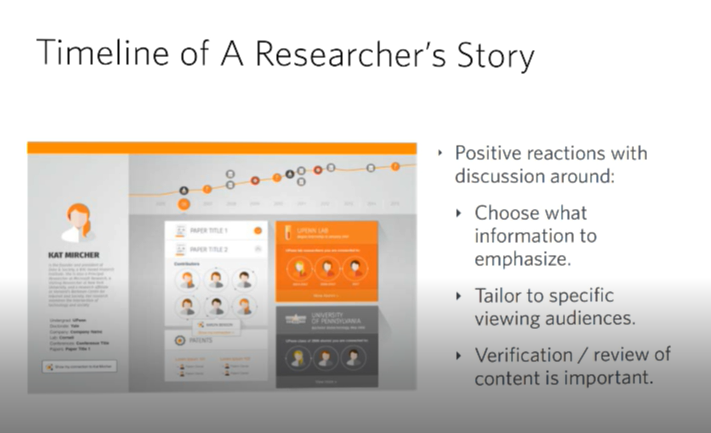

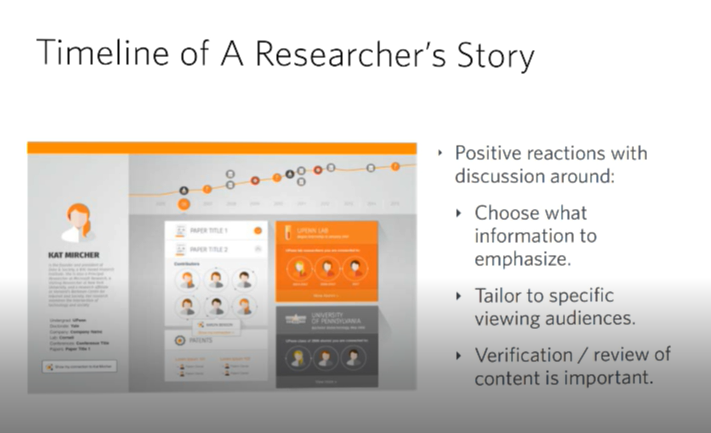

Figure 7.2: Williams Sonoma blenders

Sidenote: Framing and defining the problem are very different, but both apply to this section. To boost a product’s online sales, you may place it in between two higher- and lower-priced items. You will have successfully framed your product’s pricing. Instead of viewing it on its own, as a $300 blender, users will now see it as a “middle-of-the-road” option, not too cheap but not $400, either. As a consumer, be aware of how the art of framing a price can influence your decision-making skills. And as a designer, be aware of the power of framing.

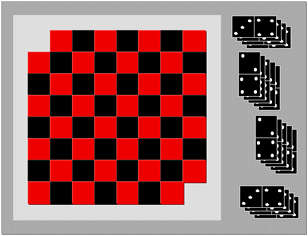

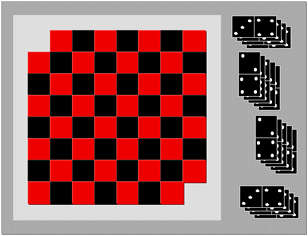

Mutilated Checkerboard Problem

Figure 7.3: Mutilated Checkerboard

A helpful example of redefining a problem space comes from the so-called “mutilated checkerboard problem” as defined by cognitive psychologists Kaplan and Simon. The basic premise is this: Imagine you have a checkerboard. (If you’re in the U.S., you’re probably imagining intermittent red and black squares; if in the U.K., you might call this a chessboard, with white and black squares. Either version works in this example.) It’s a normal checkerboard, except for the fact that you’ve taken away the two opposite black corner squares away from the board, leaving you with 62 squares instead of 64. You also have a bunch of dominoes, which cover two squares each.

Your challenge: Arrange 31 dominoes on the checkerboard such that each domino lies across its own pair of red/black squares (no diagonals).

Moving around the problem space: When you hand someone this problem, they inevitably start putting dominoes down to solve it. Near the end of that process they inevitably get stuck, and try repeating the process. (If you are able to solve the problem without breaking the dominoes — be sure to send me your solution!)

The problem definition challenge: The problem is logically unsolvable. If every domino has to go on one red and one black square, and we no longer have an even number of red and black squares on the board (since we removed two black squares and no red squares). To the novice, the definition of the problem, and the way to move around in the problem space, is to lay out all the dominoes and figure it out. Each time they put down a domino they believe you are getting closer to the end goal. They likely calculated that since there are now 62 squares, and 31 dominoes, and each domino covers two spaces, the math works. An expert, however, instantly knows that you need equal numbers of red and black squares to make this work, and wouldn’t even bother to try and figure it out.

It’s an example of how experts can approach a problem one way and novices another. In this case, we saw how novices – after considerable frustration – redefined the problem. As product and service designers, if our challenge was to redefine the problem for novices in this instance, it would involve moving novices from holding their original problem definition (i.e., 62 squares = 31 x 2 dominos, and I have to place the dominoes on squares to figure this out) to a more sophisticated representation (i.e., acknowledging that you need an even number of red and black squares to solve this problem, and therefore there is no need to touch the dominos).

Finding the yellow brick road to problem resolution

I’ve mentioned moving around in the problem space. Let’s look at that component more closely.

First, it’s really important that as product or service designers, that we make no assumptions about what the problem space looks like for our users. As experts in the problem space, we know all the possible moves around the problem space that can be taken, and it often seems obvious what decisions need to be made and needs to be done. That same problem may look very different to our more novice users. Conversely, they might have a more sophisticated perspective on the problem than we initially anticipated.

In games like chess, it’s very clear to all parties involved what their possible moves are, if not all the consequences of their moves. That’s why we love games, isn’t it? In other realms, like getting health care or renting an apartment, the steps aren’t always so clear. As designers of these processes, we need to learn what our audiences see as their “yellow brick road.” What do they think the path is that will take them from their beginning state to their goal state? What do they see as the critical decisions to make? The road they’re envisioning may be very different from what an expert would envision, or what is even possible. But once we understand their perspective, we can work to gradually morph their novice mental models into a more educated one so that they make better decisions and understand what might be coming next.

When you get stuck en route: Sub-goals

We’ve talked about problem definition for our target audiences, but what about when they get stuck? How do they get around the things that may block them (“blockers”)? Many users see their end goal, but what they don’t see, and what we product and service designers can help them see, are the sub-goals they must have, and the steps, options, possibilities, for solving those sub-goals.

One way to get around blockers is through creating sub-goals, like those we discussed in the Escape Room example. You realize that you need a certain key to unlock the door. You can see that the key is in a glass box with a padlock on it. Your new sub-goal is getting the code to the padlock (to unlock the glass box, to get the key, to unlock the door).

We can also think of these sub-goals in terms of questions the user needs to answer. To lease a car, the customer will need to answer many sub-questions (e.g., How old are you?, How is your credit?, Can you afford the monthly payments?, Can you get insurance?) before the ultimate question (i.e., Can I lease this car?) can be answered. In service design, we want to address all of these potential sub-goals and sub-questions for our user so they feel prepared for what they’re going to get from us. It’s important that we address these micro-questions in a logical progression.

Ultimately, you as a product or service designer need to understand:

We almost always make decisions at two levels: A very logical, rational “Does this make sense?” level (which is sometimes described as “System 2,” or “conscious decisions”), and a much more emotional level (you may have heard references to “System 1,” the “lizard brain,” or “midbrain”). The last chapter in this section covers emotions and how emotions and decision-making are inherently intertwined.

Chapter 8. Emotion: Logical Decision Making Meets Its Match

Figure 8.1: Portraits of Emotion

Up to now, we’ve treated everyone like they’re perfectly rational and make sound decisions every time. While I’m sure that applies in your case (not!), for most of us there are many ways to systematically deviate from logic, and often using mental shortcuts. When overwhelmed, we default to heuristics and end up “satisficing”, which means picking the best option not through careful decision making and logic, but something that is easy to recall and is about right.

As psychologists, there is a lot we can say about the study of emotions and their physiological and cognitive underpinnings. I plan to leave more details to some of the great resources at the end of this chapter, but for now let us turn to the more practical.

As designers, I want you to think about emotions that are critical to product and service design. This does mean the emotions and emotional qualities that are evoked as a customer experiences our products and services. But it also means going deeper, to the customer’s underlying and deep-seated goals and desires (which I hope you will help them accomplish with your product or service), as well as the customer’s biggest fears (which you may need to design around should they play a role in decision making).

Too much information jamming up my brain! Too much information driving me insane!

I mentioned Daniel Kahneman earlier in reference to his work on attention and mental effort in his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” He shows how, in a quiet room, by yourself, you can usually make quite logical decisions. If, however, you’re trying to make that same decision in the middle of a New York City subway platform at rush hour, with someone shouting in the background and your child tugging at your arm, you’ll be unable to make as good a decision. This is because all of your attention and working memory are being occupied with other things.

Herbert Simon coined the notion of satisficing, which means accepting an available (easily recallable) option as not the ideal decision or choice, but perhaps satisfactory given the limited cognitive resources available for decision-making at the time. In times when you are mentally taxed, either due to overstimulation or emotions, you often rely on a gut response — a quick, intuitive association or judgment.

It makes sense, right? Simply having your attention overwhelmed can dramatically affect how you make decisions. If I ask you what 17 minus 9 is, for example, you’ll probably get the answer right fairly quickly. If I ask you to remember the letters A-K-G-M-T-L-S-H in that order and be ready to repeat them, and while holding onto those letters ask you to subtract 8 from 17, however, you are likely to make the same arithmetic errors that someone who suffers from math phobia would produce. For those who get extremely distraught and emotional thinking about and dealing with numbers, those worries can fill up our working memory capacity and impair our ability to make rational decisions, forcing us to fall back on strategies like satisficing.

Some businesses have mastered the dark art of getting consumers to make suboptimal decisions. That’s why casinos intentionally overwhelm you with lighting and music and drinks, and make sure clocks and other time cues are nowhere to be found so you keep gambling. It’s why car dealerships often make you wait around for a while, then ask you to make snap decisions for which you either get a car, or nothing. When is the last time a car salesperson asked you to go home and sleep on a deal? I encourage you to do exactly that, so the emotional content is not affecting your decision-making.

Spock, I am not

With a better understanding of decision-making, you might assume that those who study decision-making for a living (e.g., psychologists and scientists) might make more logical, rational decisions, like Captain Kirk’s stoic counterpart Spock. Like other humans, we have our rational systems competing with our feelings and emotions as we make decisions. Beyond the cerebral cortex lie more primitive centers that generate competing urges to follow our emotional response and ignore the logical.

Early cognitive psychologists thought about decision-making in simple terms, focusing on all of the “minds” you’ve seen up until now, like perception, semantics, and problem-solving. But they left out one crucial piece: emotion. In his 1984 “Cognition and Emotion,” Joseph LeDoux argued that traditional cognitive psychology was making things unrealistically simple. There are so many ways that we deviate from logic, and so many ways that our lower reptilian brain affects our decision-making. Dan Ariely demonstrates several ways in his book “Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions.”

This affects us in a myriad of ways. For example, it has been well demonstrated that humans hate losses more than we love gains. “People tend to be risk averse in the domain of gains and risk seeking in the domain of losses,” Ariely writes. Because we find more pain in losing than we find pleasure in winning, we don’t work rationally in economic and other decisions. To intuitively understand this, consider a lottery. You are unlikely to buy a $1 ticket with a possible payoff of $2. You would want the chance to win $10,000, or $100,000, just from that one ticket. You are imagining what it would be like with all that money (a very emotional response), just as picturing losing that $1 and not winning can elicit the feeling of loss.

Our irrationality, however, is predictable, as Ariely demonstrates. He argues that we are systematic in the ways we deviate from what would be logically right. According to Ariely, “we consistently overpay, underestimate, and procrastinate. Yet these misguided behaviors are neither random nor senseless. They’re systematic and predictable — making us predictably irrational.”

Competing for conscious attention

Sometimes, your brain is overwhelmed by your setting, like the subway platform example. Other times, it’s overwhelmed by emotions.

A good deal of research has gone into all of these systematic deviations from logic, which I simply don’t have time to present in this book. But the key point is that in optimal conditions (no time pressure, quiet room, time to focus, no additional stress put on you), you can make great, logical decisions. However, in the real world, we often lack the ability to concentrate sufficiently to make that logical decision. What we do instead is “satisfice” — we make decisions using shortcuts. One of the tools we use in lieu of careful thought includes: “If I think of a prototypical example of this, does the ideal in my mind’s eye match a choice I’ve been given?”