Chapter 18. Succeed Fast, Succeed Often

While we are still encouraging industry standard cycles of build/test/learn, we do believe that the information gleaned from the Six Minds approach can get you to a successful solution faster.

We’ll look at the Double Diamond approach to the design process and I’ll show you how we can use the Six Minds to narrow the range of possible options to explore and get you to decision making faster. We’ll also look at learning while making, prototyping, and how we should be contrasting our product with those of our competitors.

Up to now, we’ve focused on empathizing with our audience to understand the challenge from the individuals who are experiencing it. The time we’ve taken to analyze the data should be well worth it in order to more clearly articulate the problem, identify the solution you want to focus on, and inform the design process to avoid waste.

I challenge the notion of “fail fast, fail often” because this approach can reduce the number of iteration cycles needed.

Divergent thinking, then convergent thinking

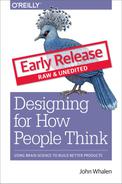

Many product and project managers are familiar with the “double diamond” product and service creation process, roughly summarized as Discover, Define, Develop, Deliver.

17.1

The double diamond process can appear complicated, and so I want to make sure you understand how the Six Minds process can help to focus your efforts along the way. I won’t focus on discovery stages such as linking enterprise goals to user goals because there are wonderful books on the overall discovery process that have come out recently that I’ll recommend at the end of this chapter.

First Diamond: Discover and Define (“designing the right thing”)

Within a double diamond framework, we first have Discover, where we try to empathize with the audience and understand what the problem is. Then Define -- figuring out which of those problems we may choose to focus on.

The six minds work generally would be seen as fitting into the discovery process. We are simply provided a sophisticated, but efficient way of capturing more information about the customers’ cognitive processes and thinking, in addition to building empathy for their needs and problems. We are collecting research revolving around understanding our customers better, creating insights, themes and specific opportunity areas. Thinking back to our last chapter, we can use our research to figure out:

- 1. What Appeals to our audience (what language they’re using to describe what they want and what’s drawing their attention)

- 2. What would Enhance their lives (help them solve their problem and expand their framework of thinking or interacting with the tool)

- 3. What would Awaken their passions (excite them and make them feel like they’re accomplishing something important for themselves)

Even though most of this chapter will focus on the second diamond, I want to acknowledge that our primary research is a treasure trove in terms of helping us to identify specific opportunity areas. After considering Appeal/Enhance/Awaken, you’ll probably have some insights into specific opportunity areas, whether it’s helping this wedding planner with finance management or helping this woodworker with marketing. Now you’re ready to explore some of the possibilities for solutions.

Second Diamond: Develop and Deliver (“designing things right”)

By the time we get to the second diamond, we have selected a customer problem that we want to solve with a product or service, and now we’re identifying all the different ways that we could build a solution to and select the optimal one to deliver.

There are a seemingly infinite number of solution routes you could take. To expedite the process of selecting the right one, we need ways to constrain the possible solution paths we take. The Six Minds framework is designed to dramatically constrain the product possibilities by informing your decision making. The answers to many of the questions we have posed in the analysis can inform design and reduce the need for design exploration.

1. Vision/Attention

Our Six Minds research can answer many questions for designers: What are the end audience looking for? What is attracting their attention? What types of words/images are they expecting? Where in the product/service they might be looking to get the information they desire? Given that understanding, part of the question for design is the design will use knowledge as an advantage, or intentionally break from those expectations.

2. Wayfinding

We will also have significant evidence for designing the interaction model including answers to questions like the following: How does our audience expect to traverse the space, including virtually (e.g., walking through an airport or navigating a phone app)? What are the ways they’re expecting to interact with the design (e.g., just clicking on something, vs. using a three-finger scroll, vs. pinching to zoom in)? What cues or breadcrumbs are they looking for to identify where they are (e.g., a hamburger icon to represent a restaurant, or different colors on a screen)? What interactions might be most helpful for them (e.g., double-tapping)? We will have some of this evidence as well.

3. Memory

We will also have highly relevant information about user expectations: What past experiences are helping to shape their expectations for this one? What designs might be the most compatible or synchronized with those expectations? What past examples will they be referencing as a basis for interacting with this new product? Knowing this, we can help to speed acceptance and build trust in what we are building by matching some of these expectations.

[Sidebar: Have we stifled innovation?]

“But what about innovation?!” you may be wondering. I am not saying thou shalt not innovate. I find it perfectly reasonable that there are times to innovate and come up with new kinds of interactions and ways to draw attention when that’s required for a different paradigm. What I’m saying is that if there are any ways in which you can innovate within an existing body of knowledge and save yourself a huge amount of struggle. When we work within those, we dramatically speed acceptance.

4. Language

Content strategists will want to know to what extent are the users experts in the area. What language style would they find most useful to them (e.g., would they say “the front of the brain” or “anterior cingulate cortex”?)? What is the language that would merit their trust and be the most useful to them?

5. Problem-Solving

What did the user believe the problem to be? In reality, is there more to the problem space than they realize? How might their expectations or beliefs have to change in order to actually solve the problem? For example, I might think I just need to get a passport, but it turns out that what I really need to do is first make sure I have documentation of my citizenship and identity before I can apply. How are users expecting us to make it clear where they are in the proces?

6. Emotion

As we help them with their problem-solving, how can we do this in a way that’s consistent with their goals and even allays some of their fears? We want to first show them that we’re helping them with their short-term goals. Then we want to show them that what they’re doing with our tool is consistent with those big-picture goals they have as well.

All in all, there are so many elements from our Six Minds that can allow you as

the designer to ideate more constructively, in a way that’s consistent with the evidence you have. Which means that your concepts are more likely to be successful when they get to the testing stage. Rather than just having this wild-open, sky’s-the-limit field of ideas, we have all these clues about the direction our designs should take.

This also means you can spend more time on the overall concept, or on branding, vs. debating some of the more basic interaction design.

Learning while making: Design thinking

Several times in this book, I’ve referenced the notion of design thinking. More recently popularized by the design studio IDEO, design thinking can be traced back to early ideas around how we formalize processes for creating industrial designs. The concept also has roots in some of the psychological studies of systematic creativity and problem-solving that were well-known by the psychologist and social scientist Herb Simon, whom I referenced earlier from his research on decision-making in the 70s.

Think of building a concept like a tiny camera that you would put in someone’s bloodstream. Obviously this is a situation you would need to design very carefully to manipulate it to make it bend the right ways. In working to construct a prototype, the engineers of this camera learned a lot about things like the weight and grip of it. No matter what you’re making, there will be all types of things like this that don’t find out until you start making it. That’s why this ideation stage is literally thinking by designing.

Don’t underestimate or overestimate the early sketches and flows and interactions and stories that you build, or the different directions you might use to come up with concepts. I think Bill Buxton, one of the Microsoft’s senior researchers, writes about this really well in his book “Sketching User Experiences: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design.” He proposes is that any designer worth their salt should be able to come up with seven to 10 different ways of solving a problem in 10 minutes. Not fully thought-out solutions, but quick sketches of different solutions and styles. Upon review, these can help to inform which possible design directions might have merit and be worthy of further exploration.

Like Buxton, I think that really quick prototype sketching is really helpful and can show you just how divergent the solutions can be. When you review them, you can see the opportunities and challenges and little gold nuggets in each one.

Starting with the Six Minds ensures that we approach this learning-while-making phase with some previously researched constraints and priorities. Rather than restraining you, these constraints will actually free you to build consensus on a possible solution space that will work best for the user, because you will be able to evaluate the prototypes through evidence-based decision making, focusing on what you’ve learned about the users, rather than have a decision made purely using the most senior person’s intuition.

I’ll give you one example of why it’s so important to do your research prior to just going ahead and building.

Case Study: Let’s just build it!

I was working with one group on a design sprint. After explaining my process, the CEO said it’s great that I have these processes, but he explained that they already knew what they needed to build. I had a suspicion that this wasn’t the case, because it’s rarely the case. Generally, a team doesn’t know what they need to build or if they’re all really set on it, there may not be good reasons why they’re so set on that particular direction.

But he wanted to jump in and get building. So we went right to the ideation phase, skipping over stakeholder priorities and target audiences and priorities and how those things might overlap to constrain our designs. We went straight to design.

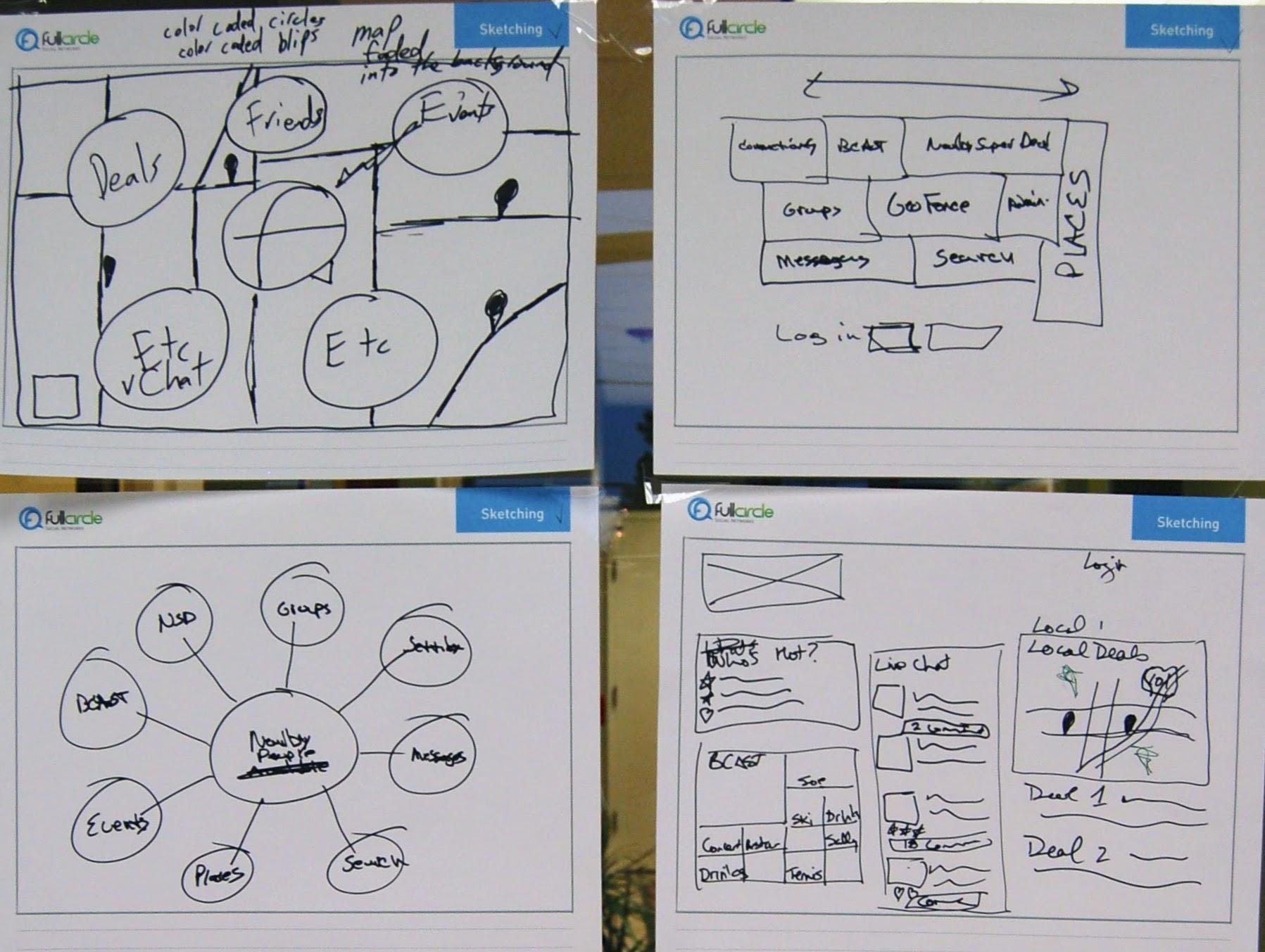

I asked he and his team to quickly sketch out their solutions so I could see what it was they wanted to build (since they were on the same page and all).

18.2

As you see from these diagrams, their “solutions” were all over the map because the target audience, and problem to be solved, varied widely between the six people. Quickly the CEO recognized that they were not aligned like he had thought. He graciously asked that we follow the systematic process.

Technically, we could have gone from that initial conversation into design. But I think this exercise brought the point home that the amount of churn and trial and error is so much greater when you aren’t aligned with evidence and constraints to solve your problem.

I’m recommending we start with the problem we think our audience is really trying to solve. From there as we ideate, we should take into account the expectations they have about how to solve the problem, the language they’re using, the ways they're expecting to interact with the problem, the emotional fears and goals they’re bringing to the problem space.

If you’re think from that perspective, it will give you a much clearer vantage point from which to come up with new ideas. I want you to do exactly this: Explore possibilities, but within the constraints of the problem to solve, and the human need you need to solve!

Don’t mind the man behind the curtain: Prototype and test

In our contextual inquiry, we consider where our target audience’s eyes go, how they’re interacting with this tool, what words they’re using, what past experiences they’re referencing, what problems they think they’re going to solve, and what some of their concerns or big goals are. I believe we can be more thoughtful in our build/test/learn stage by taking these findings into account.

With the prototype, we’ll go back to a lot of our Six Minds methods of contextual inquiry. We want to be watching where the eyes go with prototype 1 versus 2. We’ll be looking at how they seem to be interacting with this tool, and what that tells us about their expectations. We’ll consider the words they’re using with these particular prototypes, and whether we’re matching their level of expertise with the wording we’re using. What are their expectations about this prototype, or about the problem they need to solve? In what ways are we contradicting or confirming those expectations? What things are making them hesitate to interact with this product (e.g., they’re not sure if the transaction is secure or if adding an item to the shopping cart means they’ve purchased it)?

In the prototyping process, we’re coming full circle, and using what we learned from our empathy research early on. We’re designing a prototype, or series of prototypes, to test all or part of our solution.

There are other books I’ll point you to in terms of prototyping, but first I have a few observations and suggestions for you to keep in mind.

- 1. Avoid a prototype that is too high-fidelity

I’ve noticed that when we present a high-fidelity prototype — one that looks and feels as close as possible to the end product we have in mind — our audience starts to think that this is basically a fait accompli. It’s already so shiny and polished and feels like it’s actually live, even if it’s not fully thought out yet. Something about the near-finished feel of these prototypes makes stakeholders assume it’s too late to criticize. They might say it’s pretty good, or that they wish this one little thing had been done differently, but in general it’s good to go.

That’s why I prefer to work with low-fidelity prototypes that still have a little bit of roughness around the edges. This makes the participant feel like they still have a say in the process and can influence the design and flow. Results vary with paper prototypes, so it’s important that you know going into this exercise what the ideal level of specification is for this stage.

When I’m often showing a low- to medium-fidelity prototypes to a user, for example, I prefer not to use the full branded color palette, but instead stick to black-and-white. I’ll use a big X or hand sketch where an image would go. I’m cutting corners, but I’m doing that very intentionally. Some of these rougher elements signal to a client that this is just an early concept that’s still being worked out, and their input is still valuable in terms of framing how the end product should be built. I like to call this type of a prototype a “Wizard of Oz” prototype. Don’t mind the man behind the curtain.

In one example of this, we were testing how we should design a search engine for one client. For this, we first wanted to understand the context of how they would be using the search engine. We didn’t have a prototype to test, so we had them use an existing search engine. We used the example of needing to find a volleyball for someone who is eight or nine years old. We found that whether they typed in “volleyball” or “kid’s volleyball,” the same search results came up. And that was OK because we weren’t necessarily testing the precision of the search mechanism; we were testing how we should construct the search engine. We were testing how people interacted with the search, what types of results they were expecting, in what format/style, how they would want to filter those results, and generally how they would interact with the search tool. We were able to answer all of those questions without actually having a prototype to test.

2. In-situ prototyping

Now that you know I’m a fan of rough or low-fidelity prototypes, I also want to emphasize that you do still need to do your best to put people into the mode of thinking they will need. Going back to our contextual inquiry, I think it’s important to do prototype testing at someone’s actual place of work so they are thinking of real-world conditions.

3. Observe, observe, observe

This is the full-circle part. When we’re testing the prototype, we observe the Six Minds just like we did in our initial research process. Where are the audience’s eyes going? How are they attempting to interact? What words are they using at this moment? What experiences are they using to frame this experience? How are you being consistent with or breaking those anticipations? Do they feel like they’re actually solving the problem that they have? Going one step further, a bit more subtle: How does this show them that their initial concept of the problem may have been impoverished, and that they’re better off now they’re using this prototype?

When we think of emotion here, it’s not very typical for an early prototype to show someone that they’re accomplishing their deepest life goals. But we can learn a lot through people’s fears at this stage. If someone has deep-seated fears, like those young ad execs buying millions of dollars in ads who were terrified of making the wrong choice and losing their job, we can observe through the prototype what’s stopping them from acting, or where they’re hesitating, or what seems unclear to them.

Test with competitors/comparables

As you’re doing these early prototype tests, I strongly encourage you test them with live competitors if you can. One example of this was when we tested a way that academics could search for papers. In this case, we had a clickable prototype so that people could type in something, even though the search function didn’t work yet. We tested it against a Google search and another academic publishing search engine. Like with the volleyball example earlier, we wanted to test things like how we should display the search results and how we should create the search interface, in contrast with how these competitors were doing those things.

With this sort of comparable testing before you’ve built your product, you can learn a lot about new avenues to explore that will put you ahead of your competitors. Don’t be afraid to do this even if your tool is still in development. Don’t be afraid of crashing and burning in contrast to your competitors’ most slick products — or in contrast to your existing products.

I also recommend presenting several of your own prototypes. I’m pretty sure that every time we’ve shown a single prototype to users, their reaction has been positive. “It’s pretty good.” “I like it.” “Good work.” When we contrast three prototypes, however, they have much more substantive feedback. They’re able to articulate which parts of No. 1 they just can’t stand, vs. the aspects of No. 2 that they really like, if we could possibly combine them with this component of No. 3.

There’s also plenty of literature backing up this approach. Comparison reveals further unmet needs or nuances in interfaces that the interviews might not have brought out, or beneficial features that none of the existing options are offering.

Concrete recommendations:

- ● Simulate the product and test your design direction with users (including simulating AI systems).

- ● Use the same methodologies described above to further test your understanding of users’ cognitive experience (e.g., Vision/Attention, Wayfinding, Language, Memory/Assumptions, Decision-Making, and Emotion).

- ● Rework failures to be more consistent with underlying cognitive systems as a way to reduce the number of failures as you build and explore the solution space.