Chapter 6. Language: I Told You So

In Voltaire’s words, “Language is very difficult to put into words.” But I’m going to try to anyway.

In this chapter, we’re going to discuss what words our audiences are using, and why it’s so important for us to understand what they tell us about how we should design our products and services.

Wait, didn’t we just cover this?

In the previous chapter, we discussed our mental representations of meaning. We have linguistic references for these concepts as well. Often, as non-linguists, it is easy to think of a concept and the linguistic references to that concept as one and the same. But they’re not. Words are actually strings of morphemes/phonemes/letters that are associated with semantic concepts. Semantics are the abstract concepts that are associated with the words. In English, there is no relationship between the sounds or characters and a concept without the complete set of elements. For example, “rain” and “rail” share three letters, but that doesn’t mean their associated meanings are nearly identical. Rather, there are essentially random associations between a group of elements and their underlying meanings.

What’s more, these associations can differ from person to person. This chapter focuses on how different subsets of your target audiences (e.g., non-experts and experts) can use very different words, or use the same word – but attach different meanings to it. This is why it’s so important to carefully study word use to inform product and service design.

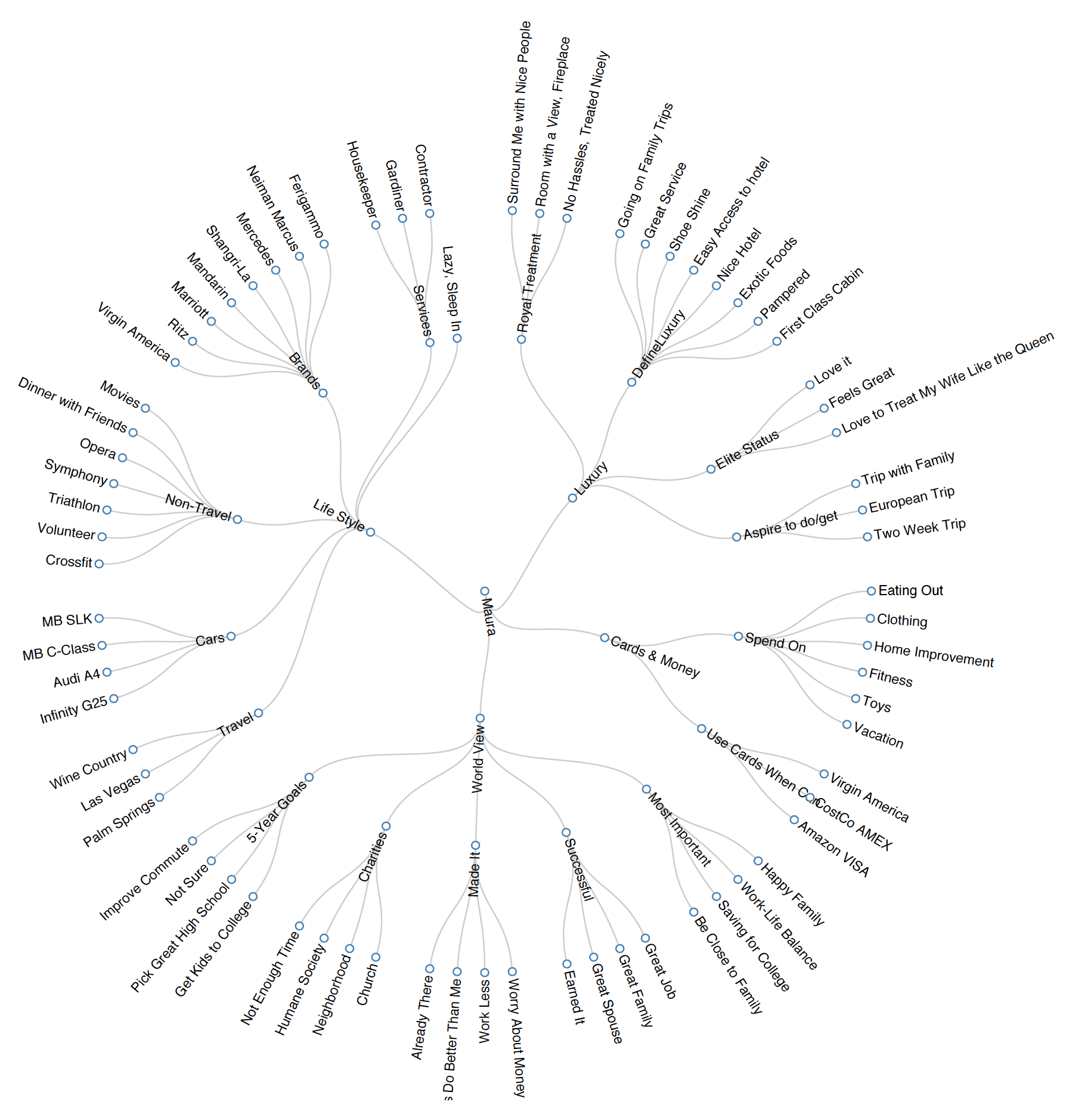

Figure 6.1: Semantic Map

The language of the mind

As humans and product designers, we assume that the words we utter have the same meanings for other people as they do for us. Although that might make our lives, relationships, and designs much easier, it’s simply not true. Just like the abstract memories that we looked at in the previous chapter, word-concept associations are more unique across individuals and especially across groups than we might realize. We might all do better in understanding each other by focusing on what makes each of us unique and special.

Because most consumers don’t realize this, and have the assumption that “words are words” and mean what they believe them to mean, they are sometimes very shocked (and trust products less) when those products or services use unexpected words or unexpected meanings for words. This can include anything from cultural references (“BAE”) to informality in tone (“dude!”) to technical jargon (“apraxic dysphasia”).

If I told you to “use your noggin,” for example, you may try to concentrate harder on something — or you may be offended that I didn’t tell you to use your dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. If you’re a fellow cognitive scientist, you might find the informality I started with insultingly imprecise. If you’re not, and I told you to use your dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, you might find my language confusing (“Is that even English?”), meaningless, and likely scary (“Can I catch that in a public space?”). Either way, I run the risk of losing your trust by deviating from your expected style of prose.

|

Ordinary American’s terms |

Cognitive neuropsychologist’s terms |

|

Stroke, brain freeze, brain area near the middle of your forehead |

Cerebral vascular accident (CVA), transient ischemic attack (TIA), anterior cingulate gyrus |

The same challenge applies to texting. Have you ever received a text reading “SMH” or “ROTFL” and wondered what it meant? Or perhaps you were the one sending it, and received a confused response from an older adult. Differences in culture, age, and geographic location are just a few of the factors that influence the meanings of words in our minds, or even the existence of that entry in our mental dictionaries — our mental “lexicon.”

|

Adult terms |

Teen texter’s terms |

|

I’ll be right back, that’s really funny, for what it’s worth, in my opinion |

BRB, ROTFL, FWIW, IMHO |

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate”

When we think about B2C communication fails, it’s often language that gets in between the business and the customer, causing customers to lose faith in the company and end the relationship. Have you ever seen an incomprehensible error message on your laptop? Or been frustrated with an online registration form that asks you to provide things you’ve never even heard of (e.g., Actual health care enrollment question: What is your FBGL, in mg/dl)?

This failure to communicate usually stems from a business-centric perspective, resulting in overly technical language or sometimes, an over-enthusiastic branding strategy that results in the company being too cryptic with their customers (e.g., What is the difference between a “venti” and a “tall”?). To reach our customer, it’s crucial that we understand the customer’s level of sophistication of your line of work (as opposed to your intimate in-house knowledge of it), and that we provide products that are meaningful to them at their level.

(Case in point: Did you catch my “Cool Hand Luke” reference earlier? You may or may not have, depending on your level of expertise when it comes to Paul Newman movies from the 60s, or your age, or your upbringing. If I were trying to reach Millennials in a clever marketing campaign, I probably wouldn’t quote from that movie; instead, I might choose something from “The Matrix.”)

Revealing words

The words that people use when describing something can reveal their level of expertise. If I’m talking with an insurance agent, for example, she may ask whether I have a PLUP. For that agent, it’s a perfectly normal word, even though I may have no idea what a PLUP is (in case you don’t, either, it’s short for a Personal Liability Umbrella Policy, which provides coverage for any liability issue). Upon first hearing what the acronym stood for, I thought it might protect you from rain and flooding!

|

Ordinary American’s terms |

Insurance broker’s terms |

|

Home insurance, car insurance, liability insurance |

Annualization, Ceded Reinsurance Leverage, Personal Liability Umbrella Policy (PLUP), Development to Policyholder Surplus |

Over time, people like this insurance agent build up expertise and familiarity with the jargon of their field. The language they use suggests their level of expertise. To reach them (or any other potential customer), we need to understand both:

- 1. The words people are using, and

- 2. What meanings associated with those words.

As product owners and designers, we want to make sure we’re using words that resonate with our audience — words that are neither over nor beneath their level of expertise. If we are communicating with a group of orthopedic specialists, we would use very different language than if we were trying to communicate to young preschool patients. If we tried to use the specialists’ complicated language when speaking to patients, instead of layman’s terms, we’d run the risk of confusing and intimidating our audience, and probably losing their trust as well.

Perhaps this is why cancer.gov provides two definitions of each type of cancer; the health professional version and the patient version. You’ve heard people say “you’re speaking my language.” Just like cancer.gov, we want your customers to experience this same comfort level when they come across your products or services — whether as an expert or novice. It’s a comfort level that comes from a common understanding and leads to a trusting relationship.

|

How many of these Canadian terms do you understand? |

|

chesterfield, kerfuffle, deke, pogie, toonie, soaker, toboggan, keener, toque, eavestroughs |

When your products and services have a global reach, there is also the question of the accuracy of translation, and the identification and use of localized terms (e.g., trunk (U.S.) = boot (U.K.)). We must ensure that the words that are used in the new location mean what we want them to mean when they’re translated into the new language or dialect. I remember a Tide detergent ad from several years ago saying things like “Here’s how to clean a stain from the garage (e.g., oil), or a workshop stain, or lawn stain.” While the translations were reasonably accurate, the intent went awry. Why? When they translated this American ad for Indian and Pakistani populations, they forgot to realize that most people had a “flat” (apartment) and didn’t have a garage, workshop, or lawn. Their conceptual structure was all different!

I’m listening

Remember in the last chapter, how I used the example of my team using interviews with young professionals and parents of young children to uncover underlying semantic representations among our audience? I can’t overstate the importance of interviews, and transcripts of those interviews, in researching your audience. We want to know the exact terms they use (not just our interpretation of what they said) when we ask a question like, “What do you think’s going to happen when you buy a car?” Examining transcripts will often reveal the lexicon your customers use is likely very different than your own (as a car salesperson).

Through listening to their exact words, we can learn what words they’re commonly using, the level of expertise their words imply, and ultimately, what sort of process this audience is expecting. This helps experience designers either conform more closely to customers’ anticipated experience or warn their customers that the process may differ from what they might expect.

Overall, here’s our key takeaway. It’s pretty simple, or at least it sounds simple enough. Once we have an understanding of our users’ level of understanding, we can create products and services that have the sophistication and terminology that works best for our customers. This leads to a common understanding of what is being discussed and trust — ultimately leading to happy, loyal customers.