Chapter 15. Emotion: The Unspoken Reality

Figure 15.1

Given everything we know so far, what do we think our audiences are trying to accomplish on a deeper level? What emotions do those goals or fears of failure illicit? Based on those emotions, how “Spock-like,” or analytical, will this person be in their decision-making?

In this chapter, we turn back to our last mind: emotion. As we discuss emotion, we’ll consider these questions:

- ● What immediate emotions are your users experiencing as they interact with your product or service?

- ● Which comments pertain to who this person is (i.e., their self-concept)?

- ● What are they trying to accomplish in life?

- ● What are they most afraid of having go wrong? Why?

- ● Who are your customers on a deeper level?

- ● What will make them feel accomplished?

Live a little (finding reality, essence)

When talking about emotion, I want you to be thinking about it on three planes:

- 1) Appeal: What will draw them in immediately? An exclusive offer? Some feature that ticks one of their micro-decision-making boxes? During a customer experience, what specific events or stimuli (e.g., encountering a password prompt or using a search function) are associated with emotional reactions?

- 2) Enhance: What will enhance their life and provide meaningful value over the next six months, and beyond?

- 3) Awaken: Over time, what will help awaken their deepest goals and wishes (and support them in accomplishing those goals)? What are some of the underlying emotions this person has about who they are, what they’re trying to become (e.g., good father, millionaire, steady worker), and what their fears are?

Though quite different, all of these forms of emotion are extremely important to consider in our overall experience design. We want to know what our consumers are thinking about themselves at a deep level, what might make that sort of person feel accomplished in society, and what their biggest fears are. Our challenge is then to design products for both the immediate emotional responses as well as those deep-seated goals and fears.

Don’t forget about fear: While it may be tempting to focus on the perks of our product, we have to go back to Kahneman, who tells us that humans hate losses more than we love gains. As such, it’s extremely important to consider fear. There could be short-term fears like not receiving a product in the mail on time, but there are also longer-term fears like not being successful, for example. By addressing not only what people are ultimately striving for but also what they are ultimately afraid of, we can provide ultimate value.

Case study: Credit card theft

Challenge: In talking about identification and identity theft on behalf of a financial institution, we met with a sub-group of people who had had their identity stolen. For them, it was highly emotional to remember trying to buy the house of their dreams and being rejected because someone else had fraudulently made another mortgage using their identity. The house was tied to much deeper underlying notions, like their “forever home” where they wanted to grow old and raise kids, as well as the negative feelings of unfair rejection they had to experience. All in all, they had a lot of fear and mistrust of the process and financial institutions due to their past experiences.

Outcome: In each of these cases, whether it was being denied a mortgage or having a credit card rejected at Staples, these consumers had deeply emotional associations with the idea of credit. For this client, it was essential that we found out the particulars of emotional, life-changing events like these that could help shape not only their unique decision-making process, but also their perceptions and mistrust of financial institutions on the whole. Designing products and services that were not tied to a financial institution helped to distance the product from the strong emotional experience that could easily be elicited.

Analyzing dreams (goals, life stages, fears)

The case study below is just one example of how dreams, goals, and fears can change by life stage.

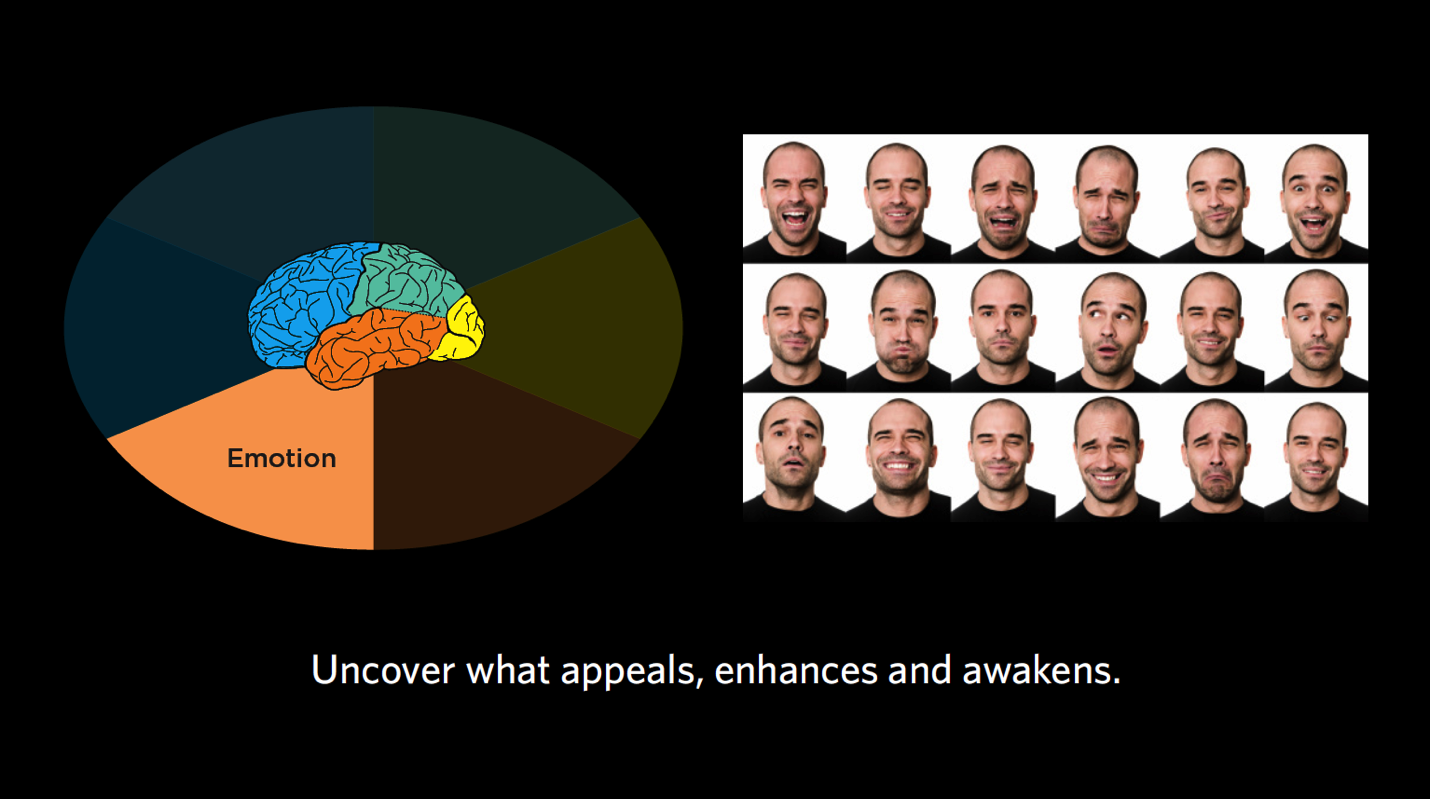

Case study: Psychographic profile

15.2

Challenge: In my line of work, sometimes we create “psychographic profiles” to segment (and better market to) groups of consumers. One artificial, but representative example is shown above. It might remind you of the questions we asked on behalf of a credit card company, which I mentioned back in Chapter 7. In these types of interviews, we go from the short-term emotions to the longer-term emotions to what people are ultimately trying to accomplish. It can be like therapy (for the participants, not us).

Outcome: As you can see in the first column, the things that Appealed to this group of consumers — older, possibly retired adults who might have grown children — were things they could do with their newly discovered free time. Things like taking that trip to Australia, or further supporting their kids in early adulthood by helping them launch their career, buy a house, etc.

Over the course of the contextual interviews, we were able to go a bit further than the short-term goals (e.g., trip to Australia) and get to what they were seeking to Enhance. Things like learning to play the piano, receiving great service and respect when they stay at hotels, or maintaining/improving their health.

Then, going even longer term, we got to this notion of what they wanted to Awaken in their lives. For many in this focus group, they were thinking beyond material success and were seeking things like knowledge, spirituality, service, leaving a lasting impact on their community — sort of the next level of fulfillment and awakening their deepest passions. As well as desire, we also observed a level of fear in not having these passions fulfilled. These are all emotions we want to address in our products and services for this group.

Getting the zeitgeist (person vs. persona specific)

In considering emotion, we’re also taking into account the distinct personalities of our end audience, the deeper undercurrent of who they are, and who it is they’re trying to become.

Case study: Adventure race

15.3: Adventure Race

Challenge: It’s not every day you get to join in on a mud-filled adventure race for work. In the one pictured above, many of the runners were members of the police force, or former military — all very hardcore athletes, as you can imagine. Our client, however, saw an opportunity to attract not-as-hardcore types to the races, from families to your average Joes.

Outcome: In watching people participate in one of these races (truly engaging in contextual inquiry, covered in mud from head to toe I might add), my team and I observed that the runners all had this amazing sense of accomplishment at the end of the race, as well as during the race. It was clear that they were digging really deep into their psyche to push through some obstacle (be it running through freezing cold water or crawling under barbed wire) and finish the race, and that was a metaphor for other obstacles in their lives that they might also overcome. By observing this emotional content, we saw that this was something we could use not only for the dedicated race types, but ordinary people as well (I don’t mean that in a degrading way; even this humble psychologist ran the race, so there’s hope for everyone!). In our product and service design efforts going forward, we harnessed the emotional content like running for a cause (as was the case with a group of cancer survivors or ex-military who were overcoming PTSD), running with a friend for accountability, giving somebody a helping hand, or signing up with others from your family, neighborhood, or gym. We knew these deeper emotions would be crucial to people deciding to sign up and inviting friends.

A crime of passion (in the moment)

Remember the idea of satisficing? It’s somewhere between satisfactory and sufficing. Satisficing is all about emotion, and defaulting to the easiest or most obvious solution when we’re overwhelmed. There are many ways we do this, and our interactions with digital interfaces are no exception.

Maybe a web page is too busy, so we satisfice by leaving the page and going to a tried-and-true favorite. Maybe we’re presented with so many options of a product (or candidates on the ballot for your state’s primaries?) that we select the one that’s displayed the most prominently, not taking specifications into consideration. Maybe we buy something out of our price range simply because we’re feeling stressed out and don’t have time to keep searching. You get the idea.

Case study: Mad Men

Challenge: Let me tell you a story about a group of young ad executives we did contextual inquiry with. Their first job out of college was with a big ad agency in downtown New York City. They thought it was all very cool and were hopeful about their career possibilities. Often, they were put in charge of buying a lot of ads for a major client, and they literally were tasked with spending $10 million on ads in one day. In observing this group of young ad-men and women, we saw emotions were running high. They were so fearful because this task — of picking which ads to run and on which stations — if done incorrectly, could end not only their career, but also the “big city ad executive” lifestyle and persona they had cultivated for themselves. Making one wrong click would end their whole dream and send them packing and ashamed (or so they believed). There was an analytics tool in place for this group of ad buyers, but because the ad buyers were so nervous, they would default to old habits (satifice) and look for basic information on how the campaign was doing, what they could improve, etc. The analytics just didn’t capture their attention immediately.

Outcome: We tweaked the analytics tool to show all the ad campaign stats the buyers would need at a glance. We made them very simple to understand and used visual attributes like bar graphs and colors to grab their attention. With so many emotions weighing in on their decisions, we wanted to make sure this tool made it clear what needed to be done next.

Real life examples

Let’s take a look at the sticky notes relevant to emotion.

Figure 15.4

- 1. “Loves that the product reviews are sorted by popularity.” Comments that use words like “love” or “hate” shouldn’t necessarily be grouped into emotion, since it always depends on context. This comment is talking about a specific design feature, so you could consider vision, wayfinding, or even memory if it’s meeting an expectation they had. I’m a bit torn, but I think the emotion of delight could be the strongest factor in this case.

Figure 15.5

- 2. “Wants his clothes to hint at his position (Senior Vice President).” The comment we just looked at related to an immediate emotion tied to a specific stimulus. This one, however, exemplifies the deeper type of emotion I’ve been talking about (albeit perhaps with more possibility for nobility). Sure, you could argue it’s more of a surface-level comment — that this person is merely browsing for a certain type of clothing. But I would argue it speaks to a deep-seated desire to display a certain persona or image, and be perceived by others in that light. I think it encompasses a desire to look powerful, be treated a certain way, drive a certain type of car — or whatever this person envisions as representing “success.”

Figure 15.6

- 3. “Says ‘reviews are a scam, the store makes them up. I don’t trust them!’” This one reads like pure emotion to me. Credibility and trust when it comes to e-commerce sites seem to be a big hurdle for this user. What are some ways to present reviews such that these fears would be allayed?

Sidenote: Remember to take your users’ feedback in totality. In addition to this comment about reviews, this customer also remarked that he was afraid of “getting burned again” and that he wanted a way to compare products the way Consumer Reports does. Taken in totality, we can surmise that this person might have issues working up trust for any e-commerce system. With feedback like this, we want to think about what we could do to make our site trustworthy for our more nervous customers.

![]()

Figure 15.7

- 4. “Afraid she might buy something by accident.” This comment doesn’t include anything specific about interaction issues leading to this fear of accidentally buying something, so I would label it as an immediate emotional consideration, rather than anything more deep seated.

Figure 15.8

- 5. “Nervous. ‘My grandson would normally help me with this.’” This one, paired with the same person’s comment above, suggests to me that this participant is uncomfortable and perhaps untrusting of e-commerce generally, leading to a fear that they might “break” something. For this type of customer, we might need to provide some sort of calm, reinforcing messaging that everything is working as it should be. It also speaks to this user’s level of expertise, which is something to keep in mind.

Figure 15.9

- 6. “Doesn’t want parents to know what she’s watching.” I mentioned this in the previous chapter under decision-making, but I wanted to point it out here as well, as I also think there’s an emotional component going on. Maybe this user is on the same Netflix account as her parents, and she wants some independence. Or maybe she’s watching something her parents wouldn’t approve of. Whatever it might be, I think there are several deeper things going on. There’s the fear of being called out as someone who watches these kinds of movies, and potentially experiencing judgment or even punishment for it. The comment also points to underlying generators of that emotion: privacy, secrecy, and perhaps even the longing to be treated like an adult.

Concrete recommendations:

- ● Build up a set of questions throughout the interview that systematically go from the innocuous to the most meaningful (e.g., What credit cards are in your wallet? What do you like to do on the weekends? What makes you happiest? What are your goals this year? What would make you a success? What are you most fearful about that would stop you from getting there?).

- ● Determine how their goals in this case (e.g., shopping for clothes) fit into the larger picture of their life (e.g., excited to find someone to marry, want to feel young again, want to feel professional and be taken seriously).

- ● When building a persona, ensure that life stage and major fears are captured (e.g., older and fearful of having to search for a new job). Fears are powerful drivers away from logic.

- ● Estimate how much is on the line with the decision they are making (picking the right gum won’t get you fired, but getting the analysis wrong for the election will).