Chapter 13. Memory: Expectations and Filling in Gaps

Figure 13.1

Next up, we’re going to look at the lens of memory. In this chapter, we’re going to consider the semantic associations our users have. By this, I mean not just words and their meanings, but also their biases, expectations for flow, and words to use.

For those of you keeping up with the buzzwords, the one you’ll hear a lot when it comes to memory is “expectations.”

Some of the questions we’ll ask include:

- ● What are the frames of reference our audience is using?

- ● What were they expecting to find?

- ● How were they expecting this whole system to work?

- ● What are the stereotypes, mental models, or schemas influencing those expectations?

- ● How do the customers’ stereotypes differ from our expert stereotypes? How do their schemas contrast with ours? What changes can we make to ensure that we’re meeting customers’ expectations?

Meanings in the mind

Let’s go back to the idea of stereotypes, which I brought up in Chapter 4. These aren’t necessarily negative, as the stereotypical interpretation of stereotype would have you believe — as we discussed earlier, we have stereotypes for everything from what a site or tool should look like to how we think certain experiences are going to work.

Take the experience of eating at a McDonald’s, for example. When I ask you what you expect out of this experience, chances are you’re not expecting white tablecloths or a maitre d’. You’re expecting to line up, place your order, and wait near the counter to pick up your meal. Others at some more modern McDonalds might also expect a touchscreen ordering system. I know someone who recently went to a test McDonald’s and was shocked that they got a table number, sat down at their table, and had their meal brought to them. That experience broke this person’s stereotype of how a quick-serve restaurant works.

For another example of a stereotype, think about buying a charging cable for your phone on an e-commerce site, vs. buying a new car online. For the former, you’re probably expecting to have to select the item, indicate where to ship it, enter your payment information, confirm the purchase, and receive the package a few days later. In contrast, with a car-buying site, you might select the car online, but you’re not expecting to buy it online right then. You’re probably expecting that the dealer will ask for your contact information to set up a time for you to come in and see the car. Buying the car will involve sitting down with people in the dealership’s financial department. Two very different expectations for how the interaction of purchasing something will go.

Soon, we’ll look at some examples from our contextual inquiry exercise. I want you to look out for how different novice stereotypes are from expert stereotypes. As we’ve been discussing with language, it’s crucial that we meet users at their level (which is often novice, when it comes to the lens of memory).

Case Study: Producing the product vs. managing the business

Challenge: For one project with various small business owners, we noticed that, broadly speaking, our audience fell into one of two categories:

- 1. Passionate producers: They loved the craftwork of producing their product, but weren’t as concerned with making money. They were all about making the most beautiful objects they could and having people love their work. They loved building relationships with their customers.

- 2. Business managers: They didn’t care as much about what they were selling and its craftsmanship; they were looking much more at running the business and making it efficient. They weren’t as client-facing.

Outcome: We saw from these two mental models of how to be a small business owner that each of them needed hugely different products. One group loved Excel, whereas the other group wanted nothing to do with spreadsheets. One group was great at networking; the other group preferred to do their work behind the scenes. This story goes to show that identifying the different types of audiences you have can really help to influence the design of your product. More on audience segmentation coming in Part 3!

Methods of putting it all together

We want to consider people’s pre-programmed expectations, not just for how something should look, but everything from how that thing should work, how they think they’re going to move ahead to the next step, and generally how they think the whole system will work. In contextual inquiry, you’ll often notice that your users are surprised by something. You want to take note of this, and ask them what surprised them, and why. On your own, you might consider what in your product and service design contrasted with their assumptions for how it might work and why.

Now, broadening your perspective even further: was there anything about the language that this person used that might be relevant here for his/her expectations, in terms of their sophistication? What else might be relevant, based on what you learned generally about the audience’s expectations?

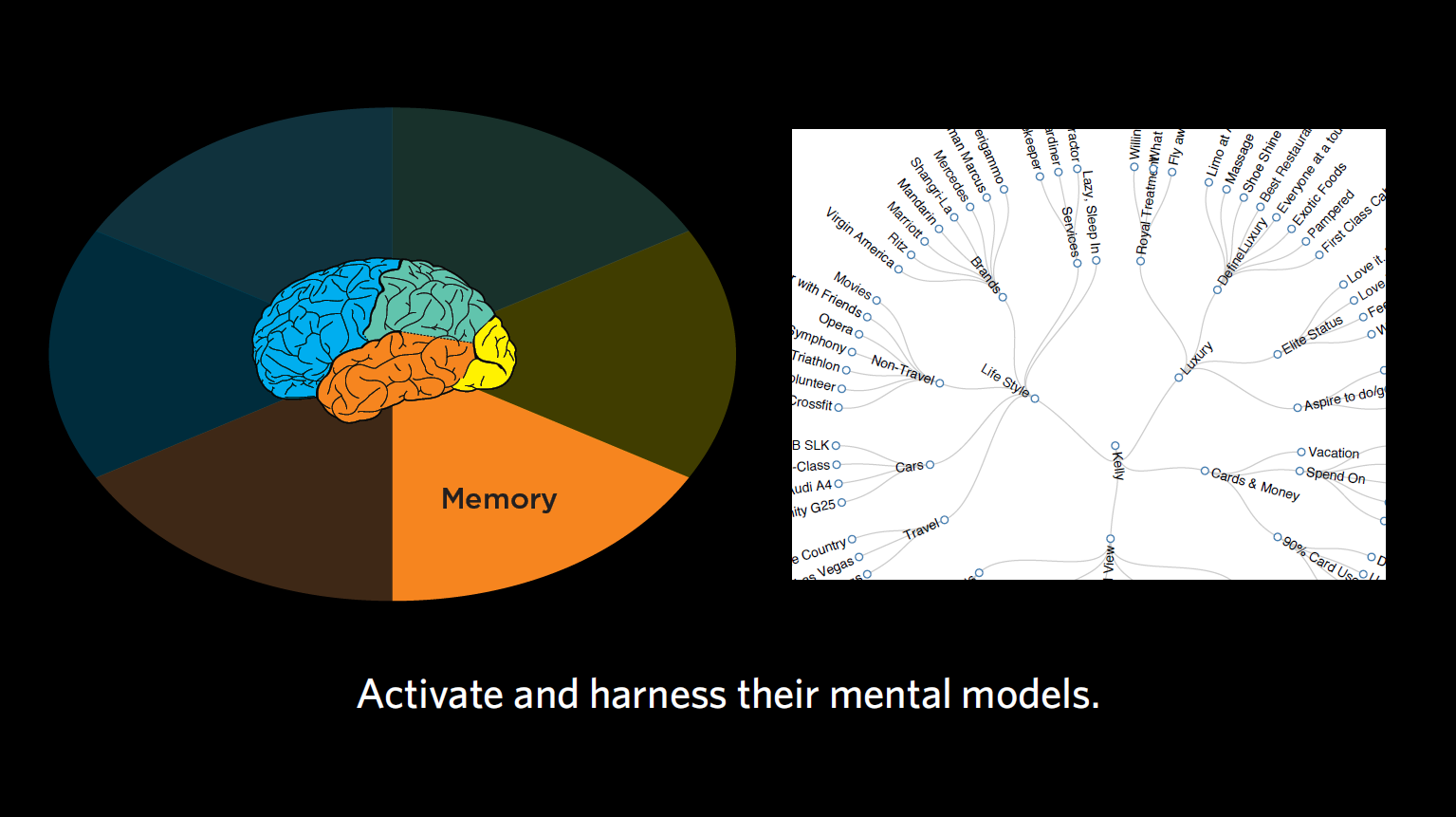

Case Study: Tax code

Figure 13.2

Challenge: For one client, we observed accountants and lawyers doing tax research. Specifically, we looked at how they were searching for particular tax codes. They said there were many tools that had the equivalent of CliffsNotes describing a tax issue, the laws associated with it, statutes, regulations, etc. Such tools were organized by publication type, but not by topic. The users, on the other hand, were expecting far more multidimensionality in the results. First, they wanted to categorize the results by federal vs. state vs. international. After that, they wanted to categorize by major topic (e.g., corporate acquisitions vs. real estate). Then, they wanted to know the relevant laws. Then, they might want to know about more secondary research on the topic. The interaction models that were available to them at the time just weren’t matching the multidimensional representation they were seeking.

Recommendation: The way these tax professionals semantically organized the world was very different than the way the results were given. In creating a tool that would be most helpful to this group, designers provide customers with filters that matched their mental model and provided limited/categorized results.

Real life examples:

Going back to our sticky notes, let’s think about memory, and which findings relate to that lens of our mind.

Figure 13.3

- 1. “I want this to know me like Stitch Fix.” This one involves a frame of reference. (For context, Stitch Fix is a women’s fashion service that sends you clothes monthly, similar to Trunk Club for men. After you give them a general sense of your style, the service uses experts and computer-generated choices to choose your clothing bundle, which you try on at home, paying for the ones you like and sending back the others.) There’s definitely some emotion going on here, suggesting that the user wants to feel known when using our tool, and is perhaps expecting a certain type of top-flight, professional customer experience. But I think the main point of this finding is that it suggests the user’s overall frame of reference in approaching our tool. Knowing the user’s expected model of interaction is helpful for us to discern what this person is actually looking for in our site.

Figure 13.4

- 2. “Can’t figure out how to get to the ‘checkout counter.’” Here, it sounds like the user is thinking of somewhere like Macy’s, where you go to a physical checkout counter. You might argue that this is vision, since the user is searching for something but can’t find it; you might argue this is language because they’re looking specifically for something called the “checkout counter”; you could argue it’s wayfinding because it has to do with getting somewhere. Or is it memory? None of these are wrong, and you’d want to consult your video footage and/or eye-tracking if possible. But I think the key point is that the user’s perspective (and associated expectations, of a brick-and-mortar store) were way off what a website would provide, implying a memory and expectations issue.

Sidenote: Because this comment is so unique (and was only mentioned by one participant), we might not address this particular item in our design work. In reviewing all your feedback together, you’ll come across instances like these where you chalk it up to something that’s unique to this individual, and not a pattern you’re seeing for all of your participants. When taken in the totality of this person’s comments, you may also realize that this was a novice shopper (more of that in Part 3, where we’ll look at audience segmentation).

This comment makes me think of a fun tool you all should check out called the Wayback Machine. This internet archive allows you to go back and see old iterations of websites. This check-out counter reminds me of an early version of Southwest Airlines’ website.

Figure 13.5

As you can see, Southwest was trying to be very compatible in its early web designs with the physical nature of a real check-out counter. What you end up with is this overly physical representation of how things work at a checkout counter, with a weigh scale, newspapers, etc. All of these features were incredibly concrete representations of how a “check-out counter” works. Even though digital interfaces have abandoned this type of literal representation (and most of these physical interactions have gone away, too), it’s important to keep older patterns of behavior in mind when designing for older audiences whose expectations may be more in line with the check-out counter days of old.

Figure 13.6

- 3. “Expects to see ‘Rotten Tomato’ ratings for movies.” I think this one also points to an expectation of how ratings work on other sites, and how that expectation influences the user’s experience with our product. This is also another example of where too literal a reading of the findings may mislead you. When you read “expects to see,” beware of assuming the word “see” indicates vision. In this case, I think the stronger point is that the user has a memory or expectation about what should be on the page. You could argue that the expectation is linked to their wanting to make a decision, so I would say this one could be either memory or decision-making.

Figure 13.7

- 4. “Thinks you should get a movie free after watching 12 ‘like Starbucks.’” This one harkens back to the good old days, when you’d drink 12 cups of coffee and get a free one from Starbucks. This is a good example of the user indicating the mental assumptions s/he has from interacting with bigger corporations, and how s/he expects our tool should match that mental model. It also relates to the user’s overall frame of reference for rewarding customer loyalty. This feels best suited to be in the memory category.

What you might discover

In our exercise, we looked at users’ expectations about other tools, products, and companies; how our users are used to interacting with them; and how users carry those expectations over into how they expect to work with our product, or the level of customer service they’re expecting from us. These are the types of things we’re usually looking for with memory. We want to look out for moments of surprise that reveal our audience’s representation, or the memories that are driving them. We also talked a little about language and level of sophistication, as these can indicate our users’ expectations.

We want to understand our users’ mental models and activate the right ones so that our product is intuitive, requiring minimal explanation of how it works. When we activate the right models, we can let our end audience engage those conceptual schemas they have from other situations, do what they need to do, and have more trust in our product or service.

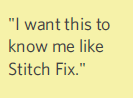

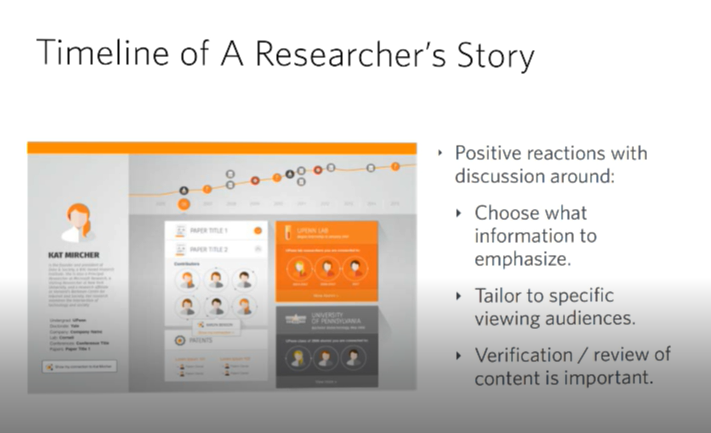

Case Study: Timeline of a researcher’s story

Figure 13.8

Challenge: For one client, we considered the equivalent of LinkedIn or Facebook for a professor, researcher, graduate student, or recent PhD looking for a job. As you may know, Facebook can indicate your marital status, where you went to school, where you grew up, even movies you like. In the case of academics, you might want to list mentors, what you’ve published, if you’ve partnered in a lab with other people or prefer to go solo, and so on. We realized there were a lot of pieces when it comes to representing the life and work of a researcher.

Recommendation: Doing contextual inquiry revealed what a junior professor would have liked to see about a potential graduate student, and how a department head might review the results of someone applying for a job in a very different way. We learned a lot about users’ expectations regarding categories of information they wanted to see and how should it be organized. We didn’t really get into that kind of granularity with the people in the sticky notes study, but with more time and practice, you’ll be able to drive out a bit more about the underlying nature of people’s representations and memory.

Concrete recommendations:

- ● Also ask the underlying source of their expectations: What are you basing your expectations on? What else have you used that works like this?

- ● Build not just a persona, but a set of assumptions that persona holds regarding word usages, how things should work according to their expectations, and how they are framing the problem.

- ● We can put together visual attention biases and the words/actions they are looking for, word usage and the meanings associated with those words, the syntax of their sentence construction, the answers they are expecting from the system, and the flow that users expect to have.

- ● All of these together can provide powerful suggestions for how best to match the system to end user needs.