Chapter 11. Language: Did They Just Say That?

Figure 11.1: Language

In this chapter, I’ll give you recommendations on how to record and analyze interviews, paying special attention to the words people utter, sentence construction, and what this tells us about their level of sophistication in a subject area.

Remember, when it comes to language, we’re considering these questions:

- ● What are the words that are most common for our customers to use?

- ● What meaning are they associating with those words?

- ● How sophisticated are the words they are using? What level of expertise in the subject matter does that imply?

- ● Are they using the same lexicon that we (as the product designers) use? Are we using any jargon that they might find difficult to understand?

Recording interviews

As I’ve mentioned, when conducting contextual inquiry, I recommend recording interviews. This does not have to be fancy. Sure, wireless mics can come in handy, but in truth, a $200 camcorder can actually give you quite decent audio. It’s very compact and unobtrusive, making it a great way to record interviews, both audio and video. Try to keep your setup as simple as possible so it’s as unobtrusive to the participant as possible and minimally affects their performance.

Prepping raw data: But, but, but…

Warning against literalism #2: After recording your interviews, you’re going to analyze those transcripts for word usage and frequency. When you do this, you’re going to find that unedited, the top words that people use are “but,” “and,” “or,” and other completely irrelevant words. Obviously what we care about is the words people use for representing ideas. So strip out all the conjunctions and other small words to get at the words that are most relevant to your product or service. Then examine how commonly used those words are.

Often, word usage differs by group, age, life status, etc.; we want to know those differences. We also want to learn, through the words people are using, a sense of how much they really understand the issue at hand.

Reading between the lines: Sophistication

The language we use product and service designers can make a customer either trust or mistrust us. As customers, we are often surprised by the words that a product or service uses. Thankfully, the reverse is also true; when you get the language right, customers become confident in what you’re offering.

Suppose you’re my customer at the auto service center, and you’re an incredible car guru. If I say “yes, sir, all we have to do is fix some things under the hood and then your car will go again,” you’ll be frustrated and skeptical, and likely probe for more specifics about the carburetor, the fuel injector, etc. “Under the hood” is not going to cut it for you. By contrast, a 16-year-old with their first car may just know that it’s running or not, and that they need to get it going again. Saying that you’ll “fix things under the hood” may be just what they want to hear.

When we read between the lines of what someone is saying, we can “hear” their understanding of the subject matter, and what this tells us about their level of sophistication. Ultimately, this leads to the right level of discussion that you should be having with this person about the subject matter.

This goes for digital security and cryptography, or scrapbooking, or French cuisine. All of us have expertise in one thing or another, and use language that’s commensurate with that expertise. I’m a DSLR camera fan, and love to talk about “F stops” and “anaphoric lenses” and “ND filters”, none of which may mean anything to you. I’m sure you have expertise in something I don’t and I have much to learn from you.

As product and service designers, what we really want to know is, what is our typical customer’s understanding of the subject matter? Then we can level-set the way we’re talking with them about the problem they’re trying to solve.

In the tax world, for example, we have tax professionals who know Section 368 of “the code” [US Internal Revenue Service tax code] is all about corporate reorganizations and acquisitions, and might know how a Revenue Procedure (or “Rev Proc”) from 1972 helps to moderate the cost-basis for a certain tax computation. These individuals are often shocked that other humans aren’t as passionate about the tax code, and are horrified that some people just want TurboTax to tell them how to file without revealing the inner workings of the tax system in all its complexities. Turbotax speaks to non-experts in terms they can understand — e.g., what was your income this year? Do you have a farm? Did you move?

Case study: Medical terms

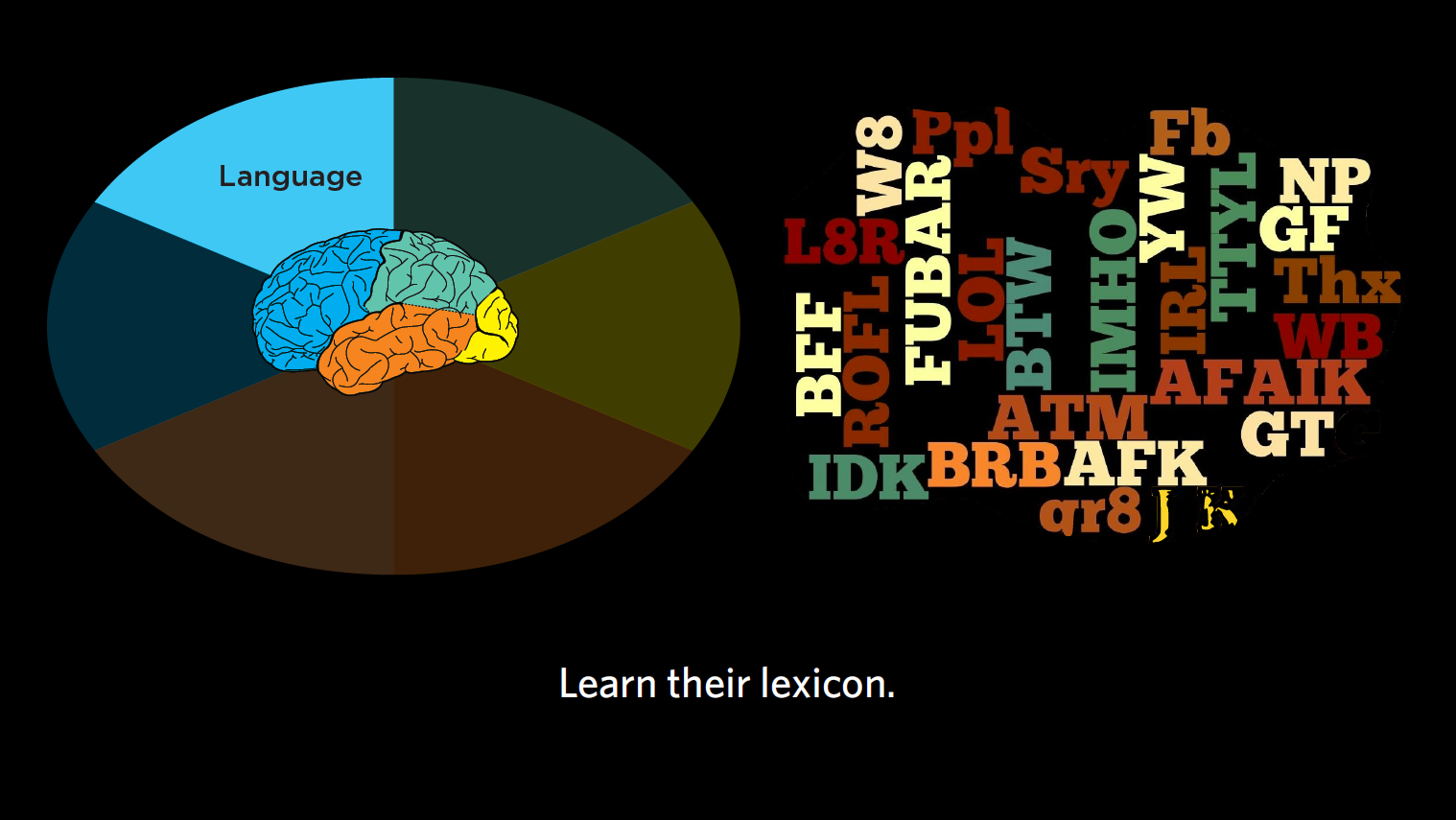

Figure 11.2: Medline

Challenge: This is a good example of how important sophistication level is to the language we use in our designs. You may have heard of MedlinePlus, which is part of NIH.gov. Depicted above, it is an excellent and comprehensive list of different medical issues. The challenge we found for customers of the site was that MedlinePlus listed medical situations by their formal names, like “TIA” or “transient ischemic attack,” which is the accurate name for what most people would call a “mini-stroke.” If NIH had only listed TIA, your average person would likely be unable to find what they were looking for in a list of search results.

Recommendation: We advised the NIH to have its search function work both for formal medical titles, and more common vernacular. We knew that both sets of terms should be prominent presented, because if someone is looking for “mini-stroke” and doesn’t see it immediately, they probably would feel like they got the wrong result. A lot of times, experts internal to a company (and doctors at NIH, and tax accountants) will struggle with including more colloquial language because it is often not strictly accurate, but I would argue that as designers, we should lean more towards accommodating the novices than the experts if you can only have one of the two. The usage goals of the site will dictate the ideal choice. Or, if you can, follow the style of Cancer.gov that I mentioned in Chapter 5, where each medical condition is actually divided out into either the health professional version and the patient version.

Reading between the lines: Word order

We also want to know what the word order is that people use. Especially when thinking about commands people might be using, where they say “OK Google, go ahead and start my Pandora to play jazz,” or “I want you to play Blue Note Jazz.” In the second case, it’s more specific to someone who really knows jazz.

All of this teaches us what sort of context to build into a new system to make it successful. This is true for search engines, taxonomies, for AI systems, and so much more. This goes to patterns and semantics, or underlying meanings, of these words. Our product or service would need to know, for example, that “Blue Note” is not the name of a jazz ensemble, but a whole record label.

Real world examples

Looking at our sticky notes, what should we place in the “language” column?

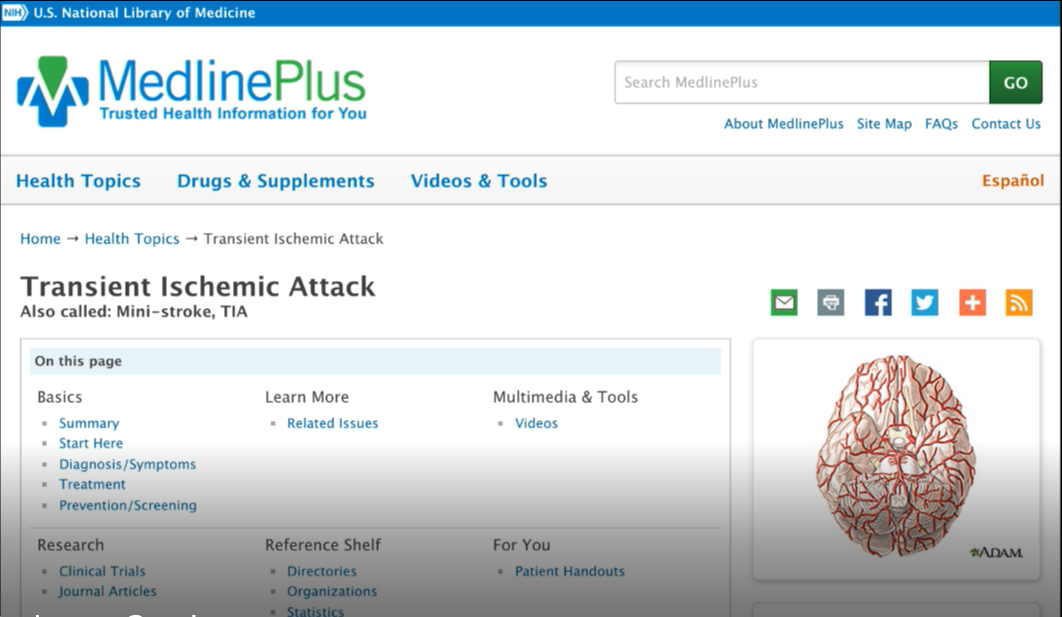

Figure 11.3

- 1. “Couldn’t find the shopping cart. Eventually figured out the ‘Shopping bag’ is the cart.” If we know that a “shopping cart” feature is present on our site, there are two possible reasons why the participant was unable to find it: either 1) there was a visual issue that prevented the user from actually seeing the feature, or 2) the user was staring at the correct feature, yet did not understand that what they were looking at was what they were looking for because they were expecting to see a different term (i.e., shopping bag vs. shopping cart). To discern which your site should have, you want to consult your notes or video footage to see where the user was actually looking at this moment. In this case, my notes indicated that the user eventually figured out the “shopping bag” was the “cart,” suggesting that this was indeed a language issue.

This one is a great example of how the same word in English can mean different things in America, vs. Canada, vs. the UK, etc. Many of us in America say “shopping cart” with visions of Costco and SUV-sized carts in our heads, but in many parts of the world, shopping bags prevail where public transit is the norm. With this type of finding, we would want to know if other participants had a similar issue to determine if we should change the terminology.

Figure 11.4

- 2. Searched for “Eames Mid Century Lounge Chair” when asked to search for a chair. Here, I would argue it’s highly unlikely for the average shopper is know that there is something called an Eames chair, and that it’s a lounge chair, and that it’s a mid-century lounge chair. These search terms suggest to me that this person is extremely knowledgeable about mid-century modern furniture, which demonstrates the high level of expertise of this particular shopper and the type of language we might need to use to reach him/her. If this is a trend, we need to let content specialists know to accommodate this level of sophistication.

Figure 11.5

- 3. Searched for “bike” to find a competition road bicycle. In this case, the customer does not sound knowledgeable. S/he didn’t provide a bicycle manufacturer, style of bike, bike material (e.g., aluminum, carbon fiber), type of race in bike, etc., which puts this customer in the category of lower sophistication level (as compared to the user who searched for the Eames Midcentury Lounge Chair). We definitely will want to follow the trends in our data and research to see how typical this type of customer is.

Warning against literalism #3: Someone interpreting these findings too literally might consider “searching” a visual function (i.e., literally scanning a page up and down to find what you’re looking for), whereas this instance of “searching” implies typing something into a search engine. As always, if you’re unsure about a comment or finding that’s out of context, go back to your notes, video footage, or eye-tracking and see if the user is literally searching all over the page for a bike, or typing something into a search engine. In addition, when taking your notes, make sure you’re as clear as possible when you use words like “search” that could be interpreted in two ways.

Figure 11.6

- 4. “Didn’t notice ‘Return to results’ link. Looking for a ‘back’ button.” You might remember this one from Chapter 9. I’ve decided to include it here as well, as it’s a great example of the interplay between the Six Minds. My notes indicated that the user didn’t notice the “return to results” button because they were actually looking for a “back” button. So they were looking in the right place. Upon review, the font sizes and visual contrast were fine. The most important consideration is that we didn’t match their linguistic expectations, so I think it’s a strong contender for “language.”

Case study: Institute of Museum and Library Services

Figure 11.7

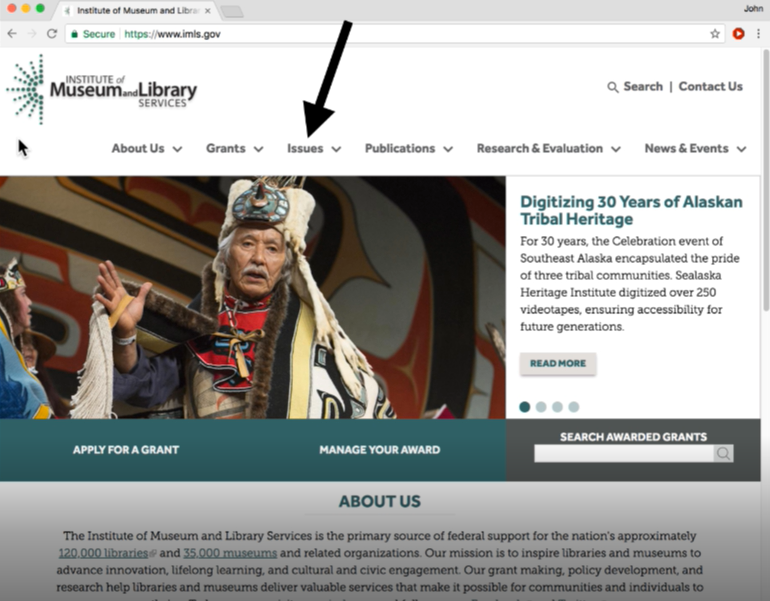

Challenge: This example demonstrates the importance of appropriate names for links, not just the content. This government-funded agency – that you probably haven’t heard of – does amazing work supporting libraries and museums across the U.S. If you look at the organization of their website navigation, it’s pretty typical: About Us, Research, News, Publications, Issues. When we tested this with users, what caught their eye was the “Issues” tab. All of our participants assumed “issues” meant things that were going wrong at the Institute. This couldn’t be further from the truth; the “Issues” area actually represented the Institute’s areas of top focus and included discussion of topics relevant to museums and libraries across America (e.g., preservation, digitization, accessibility, etc.).

Recommendation: I think the key point here was that we need to consider not only matching the language with customer expectations, but also navigational terminology as well. Moving forward, the Institute will move the “Issues” content to another location with a new name that better conveys the underlying content.

Figure 11.8

- 5. Searched for “Dewalt 2-speed 20 volt cordless drill.” This comment speaks to their level of sophistication (in this case, that they know about Dewalt products and possess a very detailed knowledge of what they’re looking for and how to find it). All of this suggests a high level of expertise in this field, and likely includes the particulars of this product. Since some of our customers are demonstrating a high level of expertise, we should prepare for people using sophisticated search terms when looking for an item as well.

Figure 11.9

- 6. Searches for “toy” to find a glow in the dark frisbee. Can’t find one. Here’s another search engine example. If you go to Amazon and type in “toy” to find a glow-in-the-dark Frisbee, you’ll end up with a needle in the haystack situation, making it tough to find exactly what you’re looking for. This points to the customer’s relatively low level of familiarity with the subject matter. Consistent with this data point, I’ve seen people Google “houses” to find houses for sale right near them, which resulted in similar needle in the haystack-type challenge.

Figure 11.10

- 7. “Wants to know if movie plays in ‘1080p or 4K UHD.’” To me, this is like the Eames chair or the Dewalt drill examples. Most people do not know what 1080p is and how that’s different from 1080i (both are possible TV resolutions), for example. To me, this suggests a pretty advanced home movie enthusiast, perhaps a videographer, who understands these different formats. This note is completely relevant to language, and might also suggest this customer is at specific step in their decision making process. Further probing would help to determine which is the case.

Figure 11.11

- 8. Searched for “Stone Gosling La La.” Here, the customer is presumably looking for the movie “La La Land.” The search terms they used suggest that they were familiar with the content (i.e., they knew the last names of the main actors and the first two words of the title), and also that they thought typing in “La La” would be sufficiently unique, in terms of movie names, to find something while searching.

Figure 11.12

- 9. “Wants to filter results by ‘Film noir.’” This data point speaks to the person’s expertise in the field and the sophistication of the language and background understanding they have regarding the film industry. There’s also an element of memory here, as it points to the user’s mental model of having results organized by genre, perhaps the way a similar site organizes its results.

Through this exercise, I’ve given you a small taste of the breadth of the types of language responses we’re looking for. They range from misnamed buttons to cultural notions of word meanings to nomenclature associated with an interaction/navigation to level of sophistication.

In all of these instances, I would go back and review the feedback, then consider how this might impact the product or service design. Due to the range of expertise that the language demonstrated, I may need to design to better reflect the range of novices and experts that make up my audience.

Concrete recommendations:

- ● Record all interview audio

- ● Measure the frequency of word use and the level of sophistication of their prose (e.g., “hurt brain” vs. left medio-parietal subdermal hematoma) to get an indication of the sophistication of their understanding of an issue (we don’t want to treat people over or under their level of sophistication; we want to foster trust with them through language).

- ● Study and pay attention to word order and words used, especially when building AI systems (in order to get the appropriate training in and ensure certain syntactic patterns will be correctly processed).