No matter how usable the sizes of our touch targets are, if they are not placed in the right location, all our efforts are pretty much worthless.

We can't talk about small UIs and large fingers without mentioning the extensive work of Luke Wroblewski in his article Responsive Navigation: Optimizing for Touch Across Devices (http://www.lukew.com/ff/entry.asp?1649).

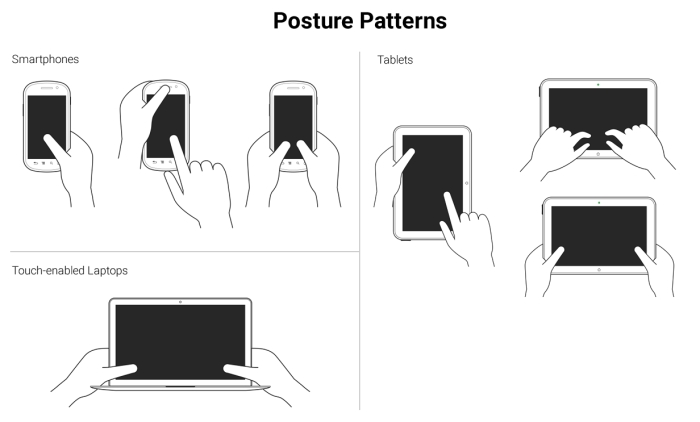

In his article, Luke talks about the patterns of posture most users have when holding their smartphones, tablets, and touch-enabled laptops:

These patterns allow us to define the best way to lay out our content in order to be easily usable and accessible.

Understanding the posture patterns of our users will allow us to understand when our targets can be the right size or even a bit smaller if there isn't enough screen real estate, or a bit larger if precision is needed, since it's different when someone uses their thumbs as opposed to their index fingers.

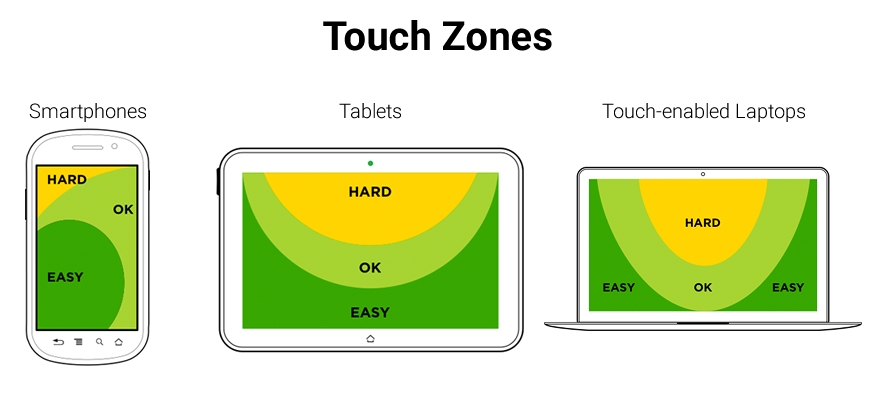

Luke also talks about touch zones, which are basically the areas of a device that are either easy or hard to reach, depending on the posture.

In all major styles of devices, smartphones, tablets and touch-enabled laptops, the ideal touch zones are in dark green, the ok touch zones are in lighter green, and the hard-to-reach zones are in yellow:

In RWD, it's a bit hard to drastically change the layout of a single page, let alone many pages (at least yet) like a standalone app, without an exorbitant amount of work. Also, there is a very high probability of negatively impacting the user experience and maintaining the content hierarchy.

RWD is strongly coupled with content strategy, so the content hierarchy needs to be preserved regardless of the device our site/app is being viewed on. We need to make sure the elements themselves are big enough for someone with large fingers to use properly. These elements are, to name a few, links, buttons, form fields, navigation items, controls of any sort like paginations, open/collapse controls in accordions, tab systems, and so on.

Now, there is one website/app element that is quite versatile in RWD: the menu button.

In order to trigger the navigation, there is a very particular element that the UX communities have very strong opinions about: The hamburger icon (≡). For now, we're going to call it something more generic: the nav icon. I'm calling it the nav icon because it doesn't necessarily have to be a hamburger icon/graphic, it can be another type of icon or a word.

The location, behavior, and design of the navigation icon and the navigation items themselves have as many variations as there are designers. What works for others may not necessarily work for us, and vice versa. So, testing becomes the go-to methodology to decide what our users feel comfortable with.

Nonetheless, there are a few UX guidelines for the nav icon that are worth mentioning and that we're going to see next.